Abstract

Aim

There is a lack of clarity about therapeutic lying in the context of everyday dementia care. This study provides conceptual clarity on how the term is used and considers the concept in relation to person-centred care.

Methods

Rodgers’ (Citation1989) evolutionary framework of concept analysis was employed. A systematic multiple database search was conducted and supplemented with snowballing techniques. Data were analysed thematically through an iterative process of constant comparison.

Results

This study highlighted that therapeutic lying is intended to be used in the person’s best interests for the purpose of doing good. However, its potential for doing harm is also evident. Its use in the literature has increased with the general trend towards becoming more accepted in the discourse. A continuum emerged depending on the degree to which a lie departs from the truth. Emerging guidelines were also evident as to when a lie could or could not be justified.

Conclusion

The term therapeutic lying, was contrasted with aspects of person-centred care and was found to be problematic. We conclude that there may be more pragmatic ways of constructing language around the care of people with dementia which could be less stigmatising.

Introduction

Lying is a common tactic employed by people caring for people with dementia. A study by James et al. (Citation2006) revealed that 96% of residential care staff lie to residents with dementia. This form of communication is increasingly referred to as ‘therapeutic lying’. Given the ubiquitous nature of the practice and the ethical conflict it presents with professional codes of practice that stress trustworthiness and fidelity, its justification hasn’t been explored commensurate with its use. Therefore, we endeavoured to analyse the literature with regards to the use of the concept in everyday dementia care and thus expand our understanding of how, it accords with person-centred care.

Dementia is a set of diseases which are progressive with no cure and at the point of diagnosis a very wide range of trajectories. This is to say, people with dementia progress in vastly different ways and over different time scales (Whitehead & George, Citation2008). However, at some point in their journey people with dementia become disorientated to person, place and time for episodes in a day or for longer periods. The way this presents and the response to this disorientation varies for everybody but it often manifests in deep anxiety and frequent attempts by the person with dementia to put right what feels wrong. This then leaves caregivers in a difficult position regarding their response to the person who may be acting in a way that seems irrational, or that puts themselves or others at risk. Traditionally, the options are reality orientation (Taulbee & Folsom, Citation1966) or validation of the emotion behind the behaviour (Feil, Citation1993). Another communication option is to lie to the person and this has been called therapeutic lying. This has been described as a person-centred activity in the best interests of a person with dementia (Cutcliffe & Milton, Citation1996; Alter, Citation2012; Culley et al., Citation2013; Butkus, Citation2014; Caiazza et al., Citation2014; Cantone et al., Citation2019; Mills et al., Citation2018).

Person-centred care holds that each person has ‘absolute value’, that all life should be respected and that the focus of care should be on the maintenance of self-esteem. Kitwood asserted that personhood is:

A standing or status that is bestowed upon one human being by others in the context of a relationship. (Kitwood, Citation1997, p. 8)

The research question therefore under investigation is: How does the concept of therapeutic lying used in contemporary literature relate to everyday dementia care and how does this accord with the dominant framing of person-centred care?’

Methods

Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis (Rodgers, Citation1989; Rodgers & Knafl, Citation2000) was employed to examine how the concept is used in the literature in everyday dementia care. This is achieved by examining the concept to see patterns of characteristics (Rodgers & Knafl, Citation2000). This method can help describe the ways the concept is publicly manifested by linguistic behaviour using an inductive approach that recognises concepts as dynamic interconnected phenomena that are influenced by their ‘significance’, ‘use’ and ‘application’ (Baldwin & Rose, Citation2009).

The strength of the approach is that it is systematic and it can assist researchers to clarify, describe and explain concepts by analysing how a concept has been used within and across health disciplines and contexts (Tofthagen & Fagerstrøm, 2010). Such clarity can help with the validity of subsequent research. Another benefit of the approach is to detect changes in the use of the term over time which can be productive of new social understandings.

Key questions have been used to carry out the analysis including five areas of inquiry (Tofthagen & Fagerstrøm Citation2010):

Surrogate terms: Do other words say the same thing as therapeutic lying or have something in common with therapeutic lying?

Attributes: What are the characteristics of therapeutic lying?

Antecedents: What events or phenomena are commonly associated with therapeutic lying?

Examples: What examples can be drawn from the text rather than constructed by the researcher?

Consequences: What happens when therapeutic lying is used?

Study search strategy

A systematic search was employed including literature from all disciplines and incorporated several databases. The databases of Pub/Medline, Cinahl, Psychinfo, OmniFile, and PsyArticle were searched. Google and google scholar were also searched to identify any peer reviewed literature that was not included in these databases. A supplementary search using snowballing techniques (backwards and forward searching) was also undertaken to identify relevant literature. No time limits were applied to these searches to gain insight into how the concept has evolved over time and how it is used in the literature by both formal and informal carers.

Search terms

An initial review of the literature allowed us to identify the concept of interest and associated expressions. These included: lie, untruth, lies, deceit, dishonesty, deception. As the aim of the search was to identify all peer reviewed literature relating to the concept of therapeutic lying in people with dementia, the terms were searched individually using the ‘select all’ database function in each search engine and then combined. Consideration was given to the inclusion of the opposite term ‘truth telling’ however, a diligent look at this literature led us to believe that this term was used predominantly in papers associated with the disclosure of diagnosis of dementia, which although relevant is not the central concern here.

The Boolean operators used for the concept analysis search

[Therapeutic lying OR lie OR untruth OR lies] AND [Deceit OR Dishonesty OR Deception] AND [Dementia OR Alzheimer’s OR Cognitive impairment].

Study selection

While the objective of the study was to take a broad approach to explore the concept, several inclusion and exclusion criteria were adhered to ().

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria guiding the concept analysis.

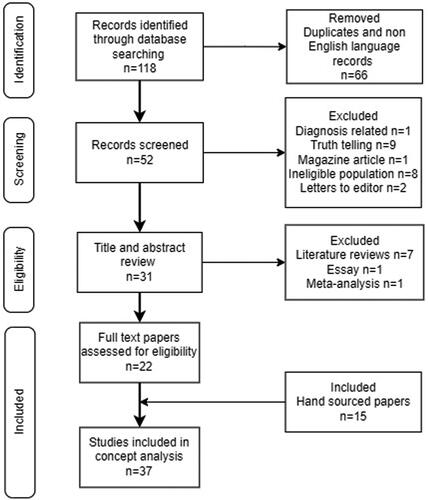

Initial searching, conducted in April 2021, identified 118 articles with 37 included in the final sample for the concept analysis once screening and eligibility criteria were applied. This process is illustrated in : PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extraction and analysis

Each article was read in full and analysed for any relevant data relating to the surrogate terms, attributes, antecedents, consequences, and related terms associated with therapeutic lying. The articles were then placed into a coding framework. Information generated from the data collection was placed into a data extraction tool or matrix. This facilitated the examination of information patterns in the data which were grouped according to Rodgers’ themes (surrogate terms, attributes, antecedents, consequences). The themes were then explored to gain greater clarity and understanding of the concept of therapeutic lying when caring for a person with dementia.

Results

The relevant data consisted of 37 papers published from 1994–2021 including 28 primary research studies, 2 case commentaries, 5 papers using case examples from practice, 1 reflective account and 1 vignette (Appendix 1). The majority (24 of 37) papers identified were published from 2014–2021. The literature selected primarily originated in the United Kingdom (20) followed by the United States (6), other European countries (7), Australia, Canada, Japan, and New Zealand (4). The first authors came from a variety of professional orientations, with the majority from a psychology (13) or nursing background (12). Within the primary research studies, the most dominant methodology used to generate data was qualitative (12), followed by quantitative (9) and mixed methodology (4). Most papers gave accounts of lying from the perspective of professional carers however, five papers discussed the issues of lying to a family member and one specifically looked at the views of people with dementia themselves.

Surrogate terms and related concepts

The most common surrogate term in the data is ‘white lie’. This was defined as a good lie or a small lie with the intention of not causing harm (Culley et al., Citation2013). Spencer (Citation2017) classified it as a fib or small untruth used only for therapeutic effect. It is subtle in nature and designed to benefit the other person (Cantone et al., Citation2019).

The second most used term in the study sample was ‘deception’, this is depicted as often non-verbal acts, intending to cause another person to have false beliefs about their current situation (Schermer, Citation2007). For example, obscuring a door so that it looks like a wall or concealing an entrance with a curtain so that it takes the appearance of a window. ‘Deception’ is intricately linked with ‘tricks’ and involves acts like hiding items such as: car keys, medication or favourite clothes that need to be washed (Blum, Citation1994; Day et al., Citation2011). Less frequently used surrogate terms include, ‘omissions of truth’ and ‘going along’.

‘Omissions of truth’ were described as the practice of not telling the person with dementia truthful information rather than actively lying. It is considered a preventative action as it involves withholding information that the person with dementia will find upsetting (Blum, Citation1994). ‘Going along with’ is also classified in studies as ‘pretending’ revolves around the caregiver’s response to a person with dementia. One carer described ‘going along with’ as a necessary strategy to survive when caring for someone with certain symptoms (Casey et al., Citation2020).

An alternative term discovered in the study sample was ‘lie’. This version without the addition of ‘therapeutic’ is described as the falsification or distortion of information verbally or written with the intention to mislead. Lies told to benefit the person were considered acceptable however, from the literature reviewed in the study sample an ‘outright lie’ was to be avoided as much as possible (Green, Citation2015).

The most common related terms associated with therapeutic lying during the data analysis were validation therapy (Schermer, Citation2007; Alter, Citation2012; Tuckett, Citation2012; Casey et al., Citation2016; Spencer, Citation2017; Jackman, Citation2020) and reality orientation (James, Citation2015; Casey et al., Citation2016; O’Connor et al., Citation2017; Jackman, Citation2020). Validation is described as an approach that highlights the importance of responding to the emotions rather than the facts being claimed by a person with dementia. Reality orientation is described as the attempt to reinforce our orientation to person, place and time by ensuring enough verbal and physical cues are apparent so that a person with dementia will be able to understand their environment.

Attributes

Attributes focus on the commonly used words to describe concepts or clusters of characteristics that makes the concept possible to identify in situations. They contribute to a real definition and what makes the concept unique and how it evolves over time (Rodgers & Knafl, Citation2000).

A clear attribute of a therapeutic lie in this sample is using a deliberate untruth to fabricate or distort information to complete care interventions (Blum, Citation1994). Therapeutic lying is described as a deliberate action of bending, twisting, or softening the truth to re-frame information that the person will find upsetting or has found previously upsetting. James (Citation2015) and McKenzie et al. (Citation2020) describe lying on a continuum from being subtle in nature, including diverting a person’s attention away from something through distraction (Schermer, Citation2007; Butkus, Citation2014; Casey et al., Citation2016; Turner et al., Citation2017; Mills et al., Citation2018; Hartung et al., Citation2020; McKenzie et al., Citation2020) to the deliberate utterance of untruths to create a reality that might be more soothing to the person. The idea of a continuum of lying was first explored by Blum (Citation1994) and developed by James (Citation2015), Mills et al. (Citation2018) and McKenzie et al. (Citation2020).

Mills et al. (Citation2018) referencing a major review of lies as communication technique (Kirtlee & Williamson, Citation2016) found five typical methods of responding to difficult questions posed by persons living with dementia: (1) telling the whole truth, (2) looking for an alternative meaning to the question and responding accordingly, (3) distracting the person from the question, (4) going along with the person’s perspectives, and (5) lying.

Another attribute identified in our study was mixing the truth with lies to make a lie more effective (McKenzie et al., Citation2021). This is to prevent the person with dementia from becoming distressed by discovering the lie. For this reason it often involves telling lies in line with the person’s life story as they are less likely to be detected (Mills et al., Citation2018). For example, if the person had children, the lie might involve the children’s names and perhaps occupations that might ring true to the person. The relevant data examined showed that if the caregiver uses a lie that is incompatible with the person’s life story it may result in distrust thus decreasing the therapeutic value of the lie (Day et al., Citation2011).

A further attribute of therapeutic lying in the literature, is that it is used in the person’s best interests (Cutcliffe & Milton, Citation1996; Alter, Citation2012; Culley et al., Citation2013; Butkus, Citation2014; Caiazza et al., Citation2014; Cantone et al., Citation2019; Mills et al., Citation2018). Casey et al. (Citation2020) describes it as a ‘deliberate intervention, underpinned by empathy’ where the main aim is to improve a person’s well-being and quality of life. It is reflective of the person’s individual needs and is used with the best of intentions (Schermer, Citation2007; Green, Citation2015). Collective thinking from all stakeholders involved about if, when and how it should be used should take place and all aspects of the process must be documented (James & Caiazza, Citation2018).

Examples of non-therapeutic lies (things that distinguish them from an attribute of therapeutic lying include: ‘Fobbing off’, incorporated to suit the caregiver only and therefore are not person-centred (Jackman, Citation2020) or ‘passing the buck’ (Turner et al., Citation2017) or answering a different question than the one that was asked (Hertogh et al., Citation2004). An outright lie was considered the least acceptable and less likely to be effective (Day et al., Citation2011; McKenzie et al., Citation2020).

Antecedents

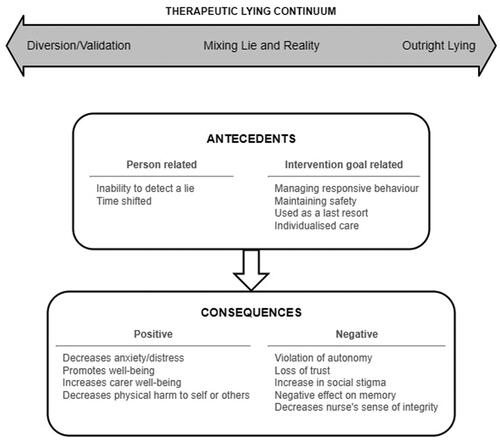

Antecedents are events, situations or phenomena that precede an instance of the concept. They are the preconditions required before the concept can occur. They are valuable in this process as they give us an insight into the social context in which the concept is used (Rodgers & Knafl, Citation2000). Antecedents identified in the study sample for therapeutic lying, fell into two distinct but interlinked categories: (1) Person related antecedents (2) Intervention/Goal related antecedents.

Person related antecedents

Two antecedents relating to the person with dementia’s presentation were identified in the literature; (1) Inability to detect a lie and (2) Time shifting.

Inability to detect a lie

The inability to detect fact from fiction or a lie from the truth was an antecedent of therapeutic lying in a person with dementia. When a person with dementia has lost this ability, the people caring for them use therapeutic lying as a communication strategy more freely (Blum, Citation1994; Elvish et al., Citation2010; Cantone et al., Citation2019). Closely related, if a person has reacted badly to the truth on multiple occasions previously the carer or practitioner may feel more justified in its use (Wood-Mitchell et al., Citation2006; Culley et al., Citation2013; O’Connor et al., Citation2017; McKenzie et al., Citation2020). The lie frequently appears the more compassionate option of care, especially if telling the truth results in more distress, discomfort, or confusion (Wood-Mitchell et al., Citation2006). In addition to this, if the carer or practitioner decides to tell the truth when a person has advanced dementia the information may simply not be retained or believed by the person especially if they are experiencing time shifting.

Time shifting

Time shifting is another major antecedent where the person with dementia gets emotionally shifted to a time in their lives where something needs to be resolved or someone they care for needs assistance for example: a child, partner, or even a pet (Casey et al., Citation2016; Turner et al., Citation2017; Jackman, Citation2020; Mills et al., Citation2018; Carter, Citation2020). When such emotions are triggered the person with dementia can become distressed and difficult to reassure (Green, Citation2015). Time shifting is subjective and therefore can have immense disparity with reality (Mills et al., Citation2018; Jackman, Citation2020). Even telling the truth may be perceived as a lie to the person with dementia during time shifting. For this reason, some have described it as the person with dementia being in their ‘own reality’ (Tuckett, Citation2012, p. 13) that the caregiver is compelled to enter to maintain the channels of communications and prevent responsive behaviour (Caiazza et al., Citation2014; Hartung et al., Citation2020).

It is common for people with dementia in the mid to later stages of the disease, owing to changes in memory, to become ‘time-shifted’. People are often shifted back to an emotional time in their past in which they think something needs to be resolved or attended to (e.g. find their partner; visit a sick relative; collect small children from school; get to work to support their family). When such ideas are triggered, the person strongly believes their view. Hence,

at such times a truth (e.g. your partner is dead, your children are grown up) will be viewed with incredulity and likely perceived by the person as an attempt to deceive.

(Turner et al., Citation2017: p. 862)

Intervention/goal related antecedents

The four intervention/goal related antecedents identified in the concept of therapeutic lying in the care of a person with dementia are: (1) Management of responsive behaviour, (2) Maintenance of safety, (3) Used as a last resort, (4) Individualised care.

Management of responsive behaviour

The management of responsive behaviour is the main antecedent when considering therapeutic lying from an intervention perspective (James et al., Citation2006; Alter, Citation2012; Cutcliffe & Milton, Citation1996; Mitchell, Citation2014; Toiviainen, Citation2014; James & Caiazza, Citation2018; Mills et al., Citation2018). If the person with dementia presents with responsive behaviours, carers both informal and formal appear to be more comfortable using this method of communication (O’Connor et al., Citation2017). Therapeutic lies are described as an approach to decrease truth related agitation, distress, and aggression. This approach often shows immediate results (Alter, Citation2012; Green, Citation2015) however, its effects may be short-lived (Brannelly & Whitewood, Citation2014). The literature suggests that this concept’s use increases if there are safety concerns for the person or others or a history of responsive behaviours escalating (Mitchell, Citation2014).

Maintenance of safety

The next most common antecedent of therapeutic lying as an intervention is maintaining the person with dementia’s safety. The carer sees the lie as a reasonable approach to ensure the person with dementia does not come to any physical or psychological harm (Butkus, Citation2014; Mitchell, Citation2014).

He wanted the car keys… I had said that I had lost it and couldn’t find it and I pretended to look.

(Blum, Citation1994, p. 26)

Therapeutic lying as a safety measure and its effect are not just limited to the person themselves. There is evidence suggesting it can also reduce the risk of violent responsive behaviour that place the staff and other residents at risk (Blum, Citation1994; Tullo et al., Citation2015; Mitchell, Citation2014).

The therapeutic doses of the medication could not be realised because when Sam was given the truth about his Risperidone, he refused to take it. On one occasion, this resulted in Sam hitting another person having dementia on the unit.

(Mitchell, Citation2014, p. 845)

Used as a last resort

Using therapeutic lying as a last resort is considered another intervention/goal related antecedent. Where other methods to mitigate responsive behaviours regarding truth related distress have been tried and failed (Hartung et al., Citation2020; Turner et al., Citation2017; Wood-Mitchell et al., Citation2006; Day et al., Citation2011; Miron et al., Citation2020). Therapeutic lying is often a last ditch attempt to calm the person with dementia (O’Connor et al., Citation2017; James & Caiazza, Citation2018; Hartung et al., Citation2020; Hirakawa et al., Citation2020). It is seen as a useful approach in this regard and a viable alternative to more restrictive physical or pharmacological interventions (O’Connor et al., Citation2017; Hartung et al., Citation2020). As a result, therapeutic lying as an intervention has been viewed as more in keeping with less medicalised person-centred approaches to care.

Historically, long-term care homes managed responsive behaviours with physical restraints and/or antipsychotic medications. However, in the last decade, long-term care homes have moved away from the use of restraints and medications to manage responsive behaviours, in order to improve outcomes and patient safety. Instead, the focus on responsive behaviour management is the use of person-centred non-pharmacological interventions, including person-centred communication.

(Hartung et al., Citation2020, p. 1)

Individualised care

The fourth and final antecedent identified in this category is individualised care. Understanding and knowing the person is considered paramount to the concept of therapeutic lying in the care of a person with dementia (Tuckett, Citation2012; O’Connor et al., Citation2017; James & Caiazza, Citation2018; Hartung et al., Citation2020; Hirakawa et al., Citation2020). It is simply not the case that one lie fits all individuals. The therapeutic lie used must reflect the person’s life story to be believable and effective (Mitchell, Citation2014; Green, Citation2015) using a consistent structured approach (James et al., Citation2006). When using therapeutic lying the people caring for a person with dementia must work as part of a team collectively to safeguard the person’s sense of self (Manthorpe et al., Citation2010).

In practice, the goal in using this technique is simply improving the life experience of a person for whom there are now only moments of memory. The role of the caregiver is just that – providing care through compassion and support, whether physical or emotional.

(Green, Citation2015, p. 20)

Consequences

Consequences are the events or situations that are a result of the use of the concept (Rodgers & Knafl, Citation2000). Positive and negative consequences were identified in the study sample.

Positive consequences

When therapeutic lying is used in a positive manner, the person with dementia can appear less anxious, distressed, and agitated (Casey et al., Citation2020; Jackman, Citation2020). The person shows positive body language during interactions using therapeutic lies and starts engaging more freely with their environment (Alter, Citation2012; Schermer, Citation2007). When the person is exhibiting calmer behaviour (Manthorpe et al., Citation2010; O’Connor et al., Citation2017; Hartung et al., Citation2020) care interactions become more pleasurable for everyone involved. By eliminating triggers linked to responsive behaviours the person becomes more emotionally relaxed (Schermer, Citation2007). This results in an increase in the person’s well-being and quality of life (Green, Citation2015; Manthorpe et al., Citation2010; McKenzie et al., Citation2021). There are also benefits for the person’s caregivers (Green, Citation2015). As communication eases between parties, stress levels for the caregiver will decrease (Spencer, Citation2017; Tullo et al., Citation2015). The caregiver feels more protected and less at risk of physical harm (Butkus, Citation2014; Mitchell, Citation2014). They describe being more able to cope with presenting situations even if confronted by a challenging moment (Blum, Citation1994).

I wouldn’t correct him. I felt it would belittle him … make him upset or more confused. I would just ignore it and change the subject. (Spencer, Citation2017)

Negative consequences

The use of therapeutic lies is not without negative consequences. Much of the evidence examined identified concerns about the use of lying as a therapeutic tool violating the person with dementia’s autonomy (Blum, Citation1994; Schermer, Citation2007, Day et al., Citation2011; Alter, Citation2012). The person with or withholding the information was seen as the person who had all the power in the relationship, leaving the person being lied to at the mercy of the information they were receiving. This has serious implications for the care of persons with dementia who are vulnerable to power imbalance as a feature of their disability (Brannelly & Whitewood, Citation2014; O’Connor et al., Citation2017).

Alter (Citation2012) believes that the use of therapeutic lies when caring for someone with dementia can exacerbate their disease by having a negative effect on memory, arguing this is especially true when the lie is not consistently told in practice. When this occurs the person with dementia can become more confused by snippets of conflicting information (James et al., Citation2003, James et al., Citation2006; Wood-Mitchell et al., Citation2006). There is also concern in the literature examined about how the person with dementia would be viewed by their peers, themselves and their wider community if therapeutic lies were used in their care. The research on the views of persons with dementia shows a concern that people might see them as different, not normal or a non-person (Day et al., Citation2011; O’Connor et al., Citation2017). This makes them extremely vulnerable (Caiazza et al., Citation2014; Casey et al., Citation2020) and open to abuse.

Discovering lies might also impact on people’s personhood, i.e. the status granted to People with Dementia by others. This sub-category overlapped considerably with ‘relationship’, particularly in reference to feelings of powerlessness and reduced autonomy.

(Day et al., Citation2011, p. 825)

In the quote below there is a suggestion that the nurse’s own integrity is damaged in the lying process and that as this social rule is breached it makes the telling of lies easier. This is a further negative consequence of lying:

The majority of participants revealed that while at first the deceit is difficult, one quickly becomes accustomed to using it. Others revealed that they saw the immediate benefits of using the therapeutic lie and began using it without either realizing it or giving it a second thought. (Green, Citation2015, p. 29)

Concept definition and model derived from the references

Based on the analysis of the attributes, antecedents and outcomes presented, a conceptual model of ‘therapeutic lying’ as it relates to everyday dementia care is outlined in . This model depicts a range of attributes which make up a continuum of therapeutic lying. The model further depicts a range of interconnected considerations in relation to the person with dementia and the intervention itself which influence the positive and negative consequences for the person with dementia or the person providing the care.

Discussion

This study has presented a model on the concept of therapeutic lying as was found in the literature. The model articulates a therapeutic lying continuum and some criteria to enhance the likelihood that a lie will contribute to wellbeing for a person with dementia. It has explored the attributes of therapeutic lying and antecedent factors related to the person with dementia and this communication strategy as an intervention. The consequences of lying have been explored. The discussion will focus on the model with respect to person-centred dementia theory.

Shared responsibility in communication

Therapeutic lying is identified as an individualised intervention, incorporated in the best interests of a distressed individual and an intervention of last resort. This concept analysis highlights both positive and negative consequences, it would therefore appear that therapeutic lying is only sometimes as it claims, therapeutic. The negative consequences require more careful consideration in the light of person-centred theory. Kitwood and Bredin (Citation1992) discussed the distinction between the basically sound ‘us’ and the neurologically impaired ‘them’. According to Kitwood and Bredin ‘We’ are seen as contributors to the problems of communication though this is often unacknowledged, indeed; ‘…much of our professional socialization involves a systematic training in how to avoid such painful insight’ (Kitwood & Bredin, Citation1992: p 278).

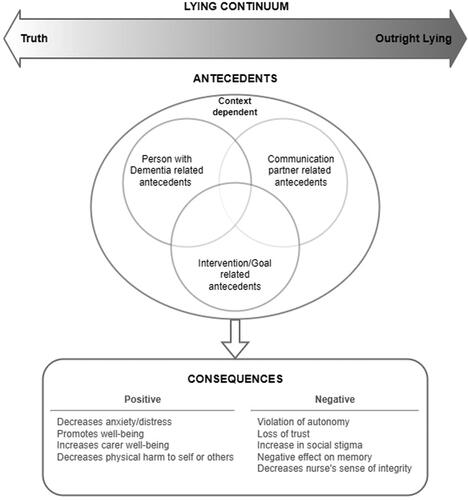

Our analysis identified two antecedents to therapeutic lying; factors relating to the person with dementia, one of which was the ability of the person with dementia to detect a lie. A person-centred understanding of communication goes beyond ensuring the lie is not detected, and accepts that the prevailing pattern of social relations is a sum of the skills and failings of both sides of the communication partnership. This would suggest a third antecedent is entirely missing in the literature reviewed, relating to the skills of the communication partner/caregiver. This raises some interesting challenges for therapeutic lying: a highly skilled empathic, self-aware carer has a greater ability to come up with creative alternatives to a lie than the same person who is less skilled in creative communication. In short, the options in communication that are open to anyone at the point of contact are dependent on the resources and skills of both sides of the communication partnership. We suggest that herein lies the greatest difficulty with the term therapeutic lying. Therapeutic lying avoids the acknowledgement of the shared responsibility in communication and as such is not entirely person-centred.

Inconsistency of time shifting

The second concern is the finding that at a certain stage a person becomes time shifted and therapeutic lying is a reasonable thing to do to join them in their reality. James et al. (Citation2006) calls for consistency in this, in case the inconsistency is remembered. There is a wealth of anthropological research to suggest that we make these divisions at our peril (Kontos et al., Citation2017). The idea that we cross a threshold and become time-shifted is at best reductionist (reducing the person to their greatest deficit rather than best asset), at worst deeply stigmatising and inaccurate given that moment to moment orientation is a dynamic process. Even in the later stages of dementia opportunities are present to make deep connections with the person with dementia to understand what they need from the communication partnership. The risk may be that in the decision to lie, and certainly to lie consistently, we lose opportunity for genuine connection in the moments when this is possible. What is remembered is most likely the emotional salience rather than the facts of the story, for example, when we tell someone that their husband has died and we allow them to grieve. Hughes (Citation2021) displays a powerful account of such cases. The jeopardy here is high given that the distinction between a therapeutic lie and treachery is subtle and moving like shifting sand.

Therapeutic lying: a problematic term

We found strong evidence in the literature that lying covers a continuum from an outright lie to the full truth. These communication strategies are helpful within a therapeutic relationship in thinking through how we might respond in any situation where we are confronted with someone living a different reality to that which we are experiencing (Kirtlee & Williamson, Citation2016). These are therapeutic skills practiced with deep respect and empathy, intended to understand what the person is experiencing, to meet their needs without particular engagement in their reality. Listening, reflecting and mirroring may well be all that is required to make a therapeutic connection whereas correcting or lying could drive disconnection. The term ‘therapeutic lying’ focuses attention on the lie rather than on the actual therapeutic aspect which is the relationship—outside of which no lie can ever be therapeutic. Lying can be therapeutic but it can also be disrespectful and damaging and our literature review was replete with such examples. Unless the caregiver knows and understands the person and has interpreted their needs, it is difficult to see how a lie could uphold a sense of self-esteem and personhood.

It is clear that at times the outcome of lying is sometimes therapeutic when done under specific conditions and it may well be the best that a particular individual can do in a given situation. Lying always needs to be interrogated for its true meaning in the communication partnership. It is such interrogation which satisfies the carer that the lie was in this instance acceptable or unavoidable. In truth, the lying is not, in these circumstances, what makes it therapeutic, it is the caregivers’ search for meaning and empathy that is therapeutic.

A proposed alternative framework for the use of lying in dementia care practice

Based on the findings of this concept analysis and our discussion we are proposing an alternative framework for reflection on the use of lying in practice ().

This model foregrounds the skills and abilities on both sides of the communication dyad that are necessary to consider if lying is to be a person-centred endeavour but were not found in the literature. We also remove the word ‘therapeutic’ from lying in our model and offer the continuum of communication strategies one might consider. As with Kirtlee and Williamson (Citation2016) our position is that the most truthful position possible without causing distress is preferred. This does not include sanitising a person with dementia’s life entirely of any sad memory or emotional experience which could represent a dehumanisation of the individual concerned.

In the context of poor training (Surr et al., Citation2017; Ekoh et al., Citation2020) and immense stigma (Batsch & Mittelman, Citation2012; Swaffer, Citation2014; Nguyen & Li, Citation2020) and clear examples of the extent of ‘othering’ (Doyle & Rubinstein, Citation2014) facing people with dementia we argue that careful reflection on our actions is always necessary when transgressing accepted ethical principles such as fidelity. We argue for an improvement in the ethical culture and development of ethical agency and leadership to enable staff to rationalise situations. Better training and education in this area will help to recognise moral distress and nurture the moral compass of caregivers (Hartman et al., Citation2018). In short, when creative communication has failed, and the caregiver feels they have no option but to lie—it is a lie and worthy of serious consideration as to whether that lie might have been avoided without undue distress to the person with dementia or others.

Limitations of the study

Concept analyses of all types have their critics, Beckwith et al. (Citation2008) cite a lack of critical appraisal and troubling theoretical underpinnings. However, we believe that the current study allows for a critical discussion of the emergence of a new term with great significance to care. While we have followed the stages of Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis as adapted by Tofthagen and Fagerstrøm (Citation2010), we have used examples of concept analyses (Higgins et al., Citation2017; Huynh et al., Citation2008) to inspire a more discursive approach using rich examples of the data analysed to evidence the antecedents, attributes, and consequences of the use of the concept. Concept analyses should not only be about legitimising and clarifying terms, if terms are used in a way that is counter to other accepted standards further critique is required.

Conclusion

To conclude we find that therapeutic lying and person-centred care are difficult to reconcile. Lying within a therapeutic relationship when carefully considered can be therapeutic but we regard the relationship as the locus of good and the lie as a vehicle. We would argue that naming lying as therapeutic without exploring the skills of one-half of the communication partnership is outside of person-centred ideals. Careful reflection on the different possible types of intervention is a more inspiring ideal and a more promising basis for a just approach to contemporary dementia care. We assert that the term ‘therapeutic lying’ is not an improvement on the word ‘lying’ which leaves the onus on the care giver to consider a priori and reflect post hoc on how therapeutic/justified the lie may have been.

Implications for practice

Questioning lying will require strong leadership from managers in settings caring for people with dementia. While we talk much of person centred care, there are very well documented barriers to its implementation (Doyle & Rubinstein, Citation2014; Miron et al., Citation2017) and we have argued here that seeing lying as therapeutic rather than the relationship is detrimental to seeing behaviours as making meaning and recognising the humanity of people with dementia. Such leaders need to create a climate where it is acceptable to ask questions about lying. Open debate on the issue should be supported in a blame free culture, where training in creative communication is a requirement for all staff. This training should enable the learner to develop skills in self-awareness, moral reasoning, creative communication and deep empathy of the lived experience of individuals living with dementia. Given the arguments made about stigma and dementia and the extent of lying as an accepted practice, it is likely that holding a space to question lying may be counter cultural at the present time and require strong leadership. However, without such deliberation we risk violating the rights of people with dementia and dehumanising in the name of care.

Implications for research and education

There is some evidence of what promotes person-centred approaches in dementia training and education (Surr & Gates, Citation2017; Surr et al., Citation2017; Parveen et al., Citation2021). The indications are that such training needs to be substantial, backed up by role modelling and reinforced by reflective practice after initial education or training. Interventional research on communication techniques and actual patient outcomes are challenging to design, however such research would be important. Finally, the exploration of better creative communication in dementia by observing and analysing expert practice would help elucidate those skills to other caregivers.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alter, T. (2012). The growth of institutional deception in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: The case study of Sadie Cohen. Journal of Social Work Practice, 26(1), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2011.571767

- Baldwin, M. A., & Rose, P. (2009). Concept analysis as a dissertation methodology. Nurse Education Today, 29(7), 780–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.03.009

- Batsch, N. L., & Mittelman, M. S. (2012). World Alzheimer Report 2012: Overcoming the Stigma of Dementia. Alzheimer’s disease International (ADI); London, UK

- Blum, N. S. (1994). Deceptive Practices in managing a family member with Alzheimer’s disease. Symbolic Interaction, 17(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.1994.17.1.21

- Beckwith, S., Dickinson, A., & Kendall, S. (2008). The “con” of concept analysis. A discussion paper which explores and critiques the ontological focus, reliability and antecedents of concept analysis frameworks. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(12), 1831–1841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.06.011

- Brannelly, T., & Whitewood, J. (2014). Therapeutic lying to assist people with dementia in maintaining medication adherence Case Commentary 2. Nursing Ethics, 21(7), 848–849. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014543886b

- Butkus, M. A. (2014). Compassionate deception: Lying to patients with dementia. Philosophical Practice, 9(2), 1388–1396.

- Caiazza, R., Cantone, D., Andrew, J. I. (2014). Should We Tell Lies to People with Dementia in Their Best Interest? The Views of Italian and UK Clinicians. [accessed 04/07/2021](https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7d68/a22c450ca2385f3ea20f210858db34491d8 4.pdf)

- Cantone, D., Attena, F., Cerrone, S., Fabozzi, A., Rossiello, R., Spagnoli, L., & Pelullo, C. P. (2019). Lying to patients with dementia: Attitudes versus behaviours in nurses. Nursing Ethics, 26(4), 984–992. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017739782

- Carter, M. (2020). ‘ Ethical deception? Responding to parallel subjectivities in people living with dementia. Disability Studies Quarterly, 40(3). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v40i3.6444

- Casey, D., Lynch, U., Murphy, K., Cooney, A., Gannon, M., Houghton, C., Hunter, A., Jordan, F., Smyth, S., Conway, A., Kenny, F., Devane, D., & Meskell, P. (2016). Therapeutic lying and approaches to dementia care in Ireland: North and South. Institute of Public Health in Ireland.

- Casey, D., Lynch, U., Murphy, K., Cooney, A., Gannon, M., Houghton, C., Hunter, A., Jordan, F., Smyth, S., Felzman, H., & Meskell, P. (2020). Telling a “good or white lie”: The views of people living with dementia and their carers. Dementia (London, England), 19(8), 2582–2600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301219831525

- Culley, H., Barber, R., Hope, A., & James, I. (2013). ‘ Therapeutic Lying in dementia care. Nursing Standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain): 1987), 28(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2013.09.28.1.35.e7749

- Cutcliffe, J., & Milton, J. (1996). In defence of telling lies to cognitively impaired elderly patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(12), 1117–1118. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199612)11:12<1117::AID-GPS523>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Day, A. M., James, I. A., Meyer, T. D., & Lee, D. R. (2011). Do people with dementia find lies and deception in dementia care acceptable? Aging & Mental Health, 15(7), 822–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.569489

- Doyle, P. J., & Rubinstein, R. L. (2014). Person-centered dementia care and the cultural matrix of othering. The Gerontologist, 54(6), 952–963. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt081

- Ekoh, P. C., George, E. O., Ejimakaraonye, C., & Okoye, U. O. (2020). An appraisal of public understanding of dementia across cultures. Journal of Social Work in Developing Societies, 2(1), 54–67. https://journals.aphriapub.com/index.php/JSWDS/article/view/1086

- Elvish, R., James, I., & Milne, D. (2010). Lying in dementia care: An example of a culture that deceives in people’s best interests. Aging & Mental Health, 14(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607861003587610

- Feil, N. (1993). The validation breakthrough: Simple technique for communicating with people with “Alzheimer’s type dementia. Health Professional Press.

- Green, D. J. (2015). An assessment of the therapeutic fib: The ethical and emotional role of therapeutic lying in the caregiving of Alzheimer’s disease patients by non-medical caregivers. CUNY Academic Works.

- Hartman, L. A., Metselaar, S., Molewijk, A. C., Edelbroek, H. M., & Widdershoven, G. A. M. (2018). Developing an ethics support tool for dealing with dilemmas around client autonomy based on moral case deliberations. BMC Medical Ethics, 19(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0335-9

- Hartung, B., Freeman, C., Grosbein, H., Santiago, A. T., Gardner, S., & Akuamoah-Boateng, M. (2020). Responding to responsive behaviours: A clinical placement workshop for nursing students. Nurse Education in Practice, 45, 102759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102759

- Hertogh, C. M., Mei The, B. A., Miesen, B. M., & Eefsting, J. A. (2004). Truth telling and truthfulness in the care for patients with advanced dementia: An ethnographic study in Dutch nursing homes. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 59(8), 1685–1693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.015

- Higgins, T., Larson, E., & Schnall, R. (2017). Unravelling the meaning of patient engagement: A concept analysis. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(1), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.09.002

- Hirakawa, Y., Yajima, K., Chiang, C., & Aoyama, A. (2020). Meaning and practices of spiritual care for older people with dementia: Experiences of nurses and care workers. Psychogeriatrics: The Official Journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society, 20(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12454

- Hughes, J. C. (2021). Truthfulness and the person living with dementia: Embedded intentions, speech acts and conforming to the reality. Bioethics, 35(9), 842–849. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12923

- Huynh, T., Alderson, M., & Thompson, M. (2008). Emotional labour underlying caring: An evolutionary concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 64(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04780.x

- Jackman, L. (2020). ‘ Extending the Newcastle model: How therapeutic communication can reduce distress in people with dementia. Nursing Older People, 32(2), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop.2020.e1206

- James, I. A. (2015). ‘ The use of CBT in dementia care: A rationale for Communication and Interaction Therapy (CAIT) and therapeutic lies. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 8(e10), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X15000185

- James, I. A., Wood‐Mitchell, A. J., Waterworth, A. M., Mackenzie, L. E., & Cunningham, J. (2006). Lying to people with dementia: Developing ethical guidelines for care settings. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(8), 800–801. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1551

- James, I. A., & Caiazza, R. (2018). Therapeutic lies in dementia care: Should psychologists teach others to be person-centred liars? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 46(4), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465818000152

- James, I. A., Powell, I., Smith, T., & Fairbairn, A. (2003). Lying to residents. Can the truth sometimes be unhelpful for people with dementia? FPOP Bulletin: Psychology of Older People, 1(82), 26–28. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsfpop.2003.1.82.26

- Kirtlee, A., Williamson, T. (2016). Ed Kousoulis, A. What is Truth? An Inquiry about truth and lying in dementia care. Mental Health Foundation. http://www.innovationsindementia.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/dementia-truth-inquiry-report.pdf

- Kitwood, T., & Bredin, K. (1992). Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well-being. Ageing and Society, 12(3), 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x0000502x

- Kitwood, T. M. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Open University Press.

- Kontos, P., Miller, K.-L., & Kontos, A. P. (2017). Relational citizenship: Supporting embodied selfhood and relationality in dementia care. Sociology of Health & Illness, 39(2), 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12453

- Manthorpe, J., Iliffe, S., Samsi, K., Cole, L., Goodman, C., Drennan, V., & Warner, J. (2010). Dementia, dignity, and quality of life: Nursing practice and its dilemmas. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 5(3), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00231.x

- McKenzie, K., Armitage, B., Murray, G., & James, I. (2021). The use of therapeutic untruths by staff supporting people with an intellectual disability who display behaviours that challenge. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 34(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12780

- McKenzie, K., Taylor, S., Murray, G., & James, I. (2020). The use of therapeutic untruths by learning disability nursing students. Nursing Ethics, 27(8), 1607–1617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020928130

- Mills, R. M., Jackman, L., Mahesh, M., & James, I. (2018). Key dimensions of therapeutic lies in dementia care: A new taxonomy. OBM Geriatrics, 3(1), 1–1. https://doi.org/10.21926/obm.geriatr.1901032

- Miron, A. M., McFadden, S. H., Hermus, N., Buelow, J., Nazario, A., & Seelman, K. (2017). Contact and perspective taking improve perceptions of humanness of older adults and people with dementia: A cross-sectional survey study. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(10), 1701–1711. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217000989

- Miron, A. M., Ebert, A. R., & Hodel, A. E. (2020). The morality of lying to my grandparent with dementia. Dementia (London, England), 19(7), 2251–2266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218819550

- Mitchell, G. (2014). Therapeutic lying to assist people with dementia in maintaining medication adherence. Nursing Ethics, 21(7), 844–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014543886

- Moncur, T., & Lovell, A. (2018). The therapeutic lie: A reflective account illustrating the potential benefits when nursing an elderly confused patient. Australian Nursing and Midwifery Journal, 25(7), 37.

- Nguyen, T., & Li, X. (2020). Understanding public-stigma and self-stigma in the context of dementia: A systematic review of the global literature. Dementia (London, England), 19(2), 148–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218800122

- O’Connor, E., James, I. A., & Caiazza, R. (2017). A response framework with untruths as last resort. Journal of Dementia Care, 25(4), 22–25.

- Parveen, S., Smith, S. J., Sass, C., Oyebode, J. R., Capstick, A., Dennison, A., & Surr, C. A. (2021). Impact of dementia education and training on health and social care staff knowledge, attitudes and confidence: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 11(1), e039939. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039939

- Rodgers, B. L. (1989). Concepts, analysis and the development of nursing knowledge: The evolutionary cycle. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 14(4), 330–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03420.x

- Rodgers, B. L., & Knafl, K. A. (2000). Concept development in nursing: Foundations, techniques, and applications. (2nd ed.). Saunders. An imprint of Elsevier.

- Schermer, M. (2007). Nothing but the truth? On truth and deception in dementia care. Bioethics, 21(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8519.2007.00519.x

- Spencer, E. A. (2017). The use of deception in interpersonal communication with Alzheimer’s disease patients. Midwest Quarterly, 58(2), 176–194.

- Surr, C. A., Gates, C., Irving, D., Oyebode, J., Smith, S. J., Parveen, S., Drury, M., & Dennison, A. (2017). Effective dementia education and training for the health and social care workforce: A systematic review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 87(5), 966–1002. Epub 2017 Jul 31. PMID: 28989194; PMCID: PMC5613811. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317723305

- Surr, C. A., & Gates, C. (2017). What works in delivering dementia education or training to hospital staff? A critical synthesis of the evidence. International Journal of Nursing Studies, ; 75, 172–188. Epub 2017 Aug 12. PMID: 28837914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.08.002

- Swaffer, K. (2014). Dementia: Stigma, language, and dementia-friendly. Dementia (London, England), 13(6), 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214548143

- Taulbee, L. R., & Folsom, J. C. (1966). Reality orientation for geriatric patients. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 17(5), 133–135. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.17.5.133

- Tofthagen, R., & Fagerstrøm, L. M. (2010). Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis–a valid method for developing knowledge in nursing science. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 24, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00845.x

- Toiviainen, L. (2014). Case commentary 1. Nursing Ethics, 21(7), 846–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014543886a

- Tuckett, A. G. (2012). The experience of lying in dementia care: A qualitative study. Nursing Ethics, 19(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011412104

- Tullo, E. S., Lee, R. P., Robinson, L., & Allan, L. (2015). Why is dementia different? Medical students’ views about deceiving people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 19(8), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.967173

- Turner, A., Eccles, F., Keady, J., Simpson, J., & Elvish, R. (2017). The use of the truth and deception in dementia care amongst general hospital staff. Aging & Mental Health, 21(8), 862–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1179261

- Whitehead, P., & George, D. (2008). The myth of Alzheimer’s: What you aren’t being told about today’s most dreaded diagnosis. St. Martin’s. ISBN 0312368178

- Wood-Mitchell, A., Waterworth, A., Stephenson, M., & James, I. (2006). Lying to people with dementia: Sparking the debate. Journal of Dementia Care, 14, 30–34.