Abstract

Objectives

To develop and evaluate feasibility of a program for family and professional caregivers to identify and manage apathy in people with dementia: the Shared Action for Breaking through Apathy program (SABA).

Methods

A theory- and practice-based intervention was developed and tested among ten persons with apathy and dementia in two Dutch nursing homes from 2019 to 2021. Feasibility was evaluated with interviews with family caregivers (n = 7) and professional caregivers (n = 4) and two multidisciplinary focus groups with professional caregivers (n = 5 and n = 6).

Results

SABA was found feasible for identifying and managing apathy. Caregivers mentioned increased knowledge and awareness regarding recognizing apathy and its impact on their relationship with the person with apathy. They experienced increased skills to manage apathy, a greater focus on small-scale activities and increased appreciation of small moments of success. The content, form and accessibility of the program’s materials were considered facilitating by all stakeholders, as was the compatibility of the procedures with the usual way of working. The expertise and involvement of stakeholders, staff stability and the support of an ambassador and/or manager were facilitating, while insufficient collaboration was a barrier. Organizational and external aspects like not prioritizing apathy, staff discontinuity, and the Covid-19 pandemic were perceived as barriers. A stimulating physical environment with small-scale living rooms, and access to supplies for activities were considered facilitating.

Conclusions

SABA empowers family and professional caregivers to successfully identify and manage apathy. For implementation, it is important to take into account the facilitators and barriers resulting from our study.

Introduction

Apathy is common in people with dementia living in nursing homes (Leung et al., Citation2021; Nijsten et al., Citation2017; Zhao et al., Citation2016) and related to adverse outcomes on functional independence, cognitive functioning, quality of life and mortality (Dufournet et al., Citation2019; Linde et al., Citation2017; Nijsten et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, apathy is rarely diagnosed nor specifically treated in nursing homes (NHs). Previous research and interventions have focussed on challeging behavior in general, and agitation and depression in particular (Koch et al., Citation2022). This leaves those with apathy at risk of being overlooked. Although, to date no medical treatment has proven effective (Azhar et al., Citation2022; Ruthirakuhan et al., Citation2018), psychosocial interventions targeting apathy have recently received growing attention and can have a positive clinical impact in reducing apathy in people with dementia (Goris et al., Citation2016; Theleritis et al., Citation2018; Treusch et al., Citation2015). However, research shows that family and professional caregivers experience difficulties in identifying apathy in people with dementia and can experience challenges in managing apathy (Nijsten et al., submitted; Chang et al., Citation2021). Nonetheless, they may feel more successful in managing apathy when they adjust their expectations, appreciate small successes and strive for meaningful contact (Nijsten et al., submitted). Moreover, empowering family and professional caregivers in managing apathy may improve the well-being of those involved. Indeed, integrating positive sources of interest and pleasant interactions into a practice-based intervention could help to support persons with apathy and their caregivers (Dening et al., Citation2022; van Corven et al., Citation2021).

Therefore, in this study we developed and piloted a theory- and practice-based intervention to empower family and professional caregivers in identifying and managing apathy in people with dementia in NHs: the Shared Action for Breaking through Apathy program (SABA).

Methods and materials

Design

The British Medical Research Council’s (MRC) framework on complex interventions (Skivington et al., Citation2021) directed the development and feasibility evaluation of the SABA program. The MRC framework includes four phases: (I) development of the intervention, (II) small-scale assessment of the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, (III) large-scale evaluation of fidelity, quality of the implementation, mechanism of change and context, and (IV) implementation. This paper describes phases I and II.

In MRC phase I, we used intervention mapping (IM) (Bartholomew et al. Citation2016), which comprises six different steps: (1) conducting a needs assessment to identify potential improvements, (2) defining the behaviors, determinants and beliefs to be targeted by the intervention, (3) selecting behavior change techniques and ways to integrate them into the program, (4) designing a coherent and executable program, (5) specifying an implementation plan, and (6) generating an evaluation plan to conduct the intervention and a process evaluation to measure the program’s effectiveness.

MRC phase II was guided by the approach described by Bowen et al. (Citation2009), which defines feasibility in terms of the constructs of demand, acceptability, implementation, practicality, integration and limited efficacy. Demand is the extent to which the program is likely to be used, acceptability refers to the suitability in daily practice, implementation refers to the degree of delivery, practicality refers to the extent to which the program is carried out as intended, integration refers to the extent to which the program can be integrated in existing systems, and limited efficacy addresses the promise that the program shows in terms of being effective.

Setting and participants

Two Dutch NHs of the University Knowledge network for Older adult care Nijmegen (UKON) participated between June 2019 and October 2021. Family caregivers (relatives and/or legal representatives) and professional caregivers (nurses, activity coordinators, psychologists and physicians) were participants in our study. Persons with apathy participated in the study as they were offered the SABA-program. They did not participate in interviews or focus group discussions.

Materials and procedures

MRC phase I: intervention development

Phase I lasted from June 2019 to August 2021, during which each of the two participating organizations formed a multidisciplinary working group that regularly met and was chaired by the researchers (HN and AP). All participants were familiar with at least one of the persons with apathy included as a professional or family caregiver. The working group meetings were held in steps 1, 4 and 5 (see below) to reflect on the wishes and needs of caregivers and select, discuss the content and finetune potential intervention materials and procedures.

In step 1 of IM, we conducted a needs assessment to establish potential improvements, as described in an other paper (Nijsten et al., submitted). Three central themes were identified that need to be addressed for enhancing the identification and management of apathy.

Next, in step 2, we determined the behavioral elements to be targeted for family and professional caregivers to identify and manage apathy.

In step 3, the selection of behavior change techniques was guided by the themes of the needs assessment in step 1, the known literature (Bartholomew et al., Citation2016; Lavoie et al., Citation2018) and the professional expertise of the project team.

The design of the program—specified in step 4—was supervised by the project team, comprising a family representative, the local coordinating psychologists, and the authors.

Finally, in step 5, we composed a feasibility study.

MRC phase II: feasibility evaluation

Phase II started with testing of the SABA program in March 2020, but had to be stopped after two weeks due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Subsequently, it was restarted and tested between October 2020 and August 2021, with pauses in between due to outbreaks of COVID-19 on participating units and associated restrictive measures. The SABA program was tested by the stakeholders of each person with apathy involved for two months. After the completion of the intervention, we evaluated its feasibility between June and September 2021. Afterwards, we developed an implementation guide based upon the feasibility evaluation in MRC phase II. This implementation guide was also presented to an implementation expert of the UKON and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) for feedback.

Data collection phase II: feasibility evaluation

For persons with apathy, family caregivers and professional caregivers, data were collected on age, sex, educational level. For the persons with apathy the type of dementia was retrieved from personal files. Family caregivers were asked to describe their relationship with the persons with apathy.

Qualitative data were collected for the elements of the feasibility framework. We used the fieldnotes of all local multidisciplinary working group meetings. We held face-to-face or online individual interviews with family and professional caregivers (by choice), whereby these interviews were performed by a research student (FM). Moreover, we held one multidisciplinary focus group per organization, which took place at the local nursing home and was moderated by the first and second author (HN, AP). An interview guide was used (see Appendix A, supplementary material) and all interviews and focus group discussions were tape-recorded, anonymized and transcribed verbatim by a research student (FM).

Additional quantitative data: Upon inclusion, the severity of dementia was assessed by professional caregivers, using the validated Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) (Reisberg et al., Citation1982), which describes seven stages of dementia.

Before and after the intervention, professional caregivers provided a medication overview to exclude side effects as a cause of apathy. Moreover, to add to the qualitative data on limited efficacy, additional quantitative data were collected. Both caregiver groups assessed the severity of apathy using the Abbreviated Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES-10) (Lueken et al., Citation2007), a ten-item validated observation scale to measure apathy in NHs. They also filled in the Revised Index for Social Engagement for Long-term Care (RISE) (Gerritsen et al., Citation2008), which comprises six questions regarding social engagement.

Family caregivers also filled in questions 20 to 22 of the TOPICS-MDS, which concern the perceived quality of life of the person with apathy and the health-related quality of life of family caregivers (Lutomski et al., Citation2013).

Data analysis phase II: feasibility evaluation

The qualitative data were analyzed using Atlas.ti (version 8.4.22). We used deductive thematic analysis (Elo & Kyngas, Citation2008), guided by the elements of Bowen et al.’s approach to categorize relevant data. When applicable, the codes within an element were categorized into experiences regarding the procedures, materials and collaboration between family and professional caregivers. For the deductive analysis, three researchers (HN, AP, FM) independently derived codes from the data and discussed them in pairs (HN, FM; AP, FM; HN, AP) until consensus was reached. Additionally, we used an inductive approach to classify facilitators and barriers for Bowen et al.’s implementation element. For this inductive analysis, two researchers (HN, AP) separately assigned codes within the element implementation and discussed them until consensus was reached. Subsequently, codes were grouped by the researchers independently into higher-order categories based on meaning or content and thereafter discussed with the research team (DG, MS, RK, RL) to reach consensus. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) were followed (Tong et al., Citation2007) (see Appendix B, supplementary material).

To describe the quantitative data, descriptive statistics were applied, using SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp. 2020).

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the applicable Dutch legislation, and in agreement with the Code of Conduct for Health Research and the declaration of Helsinki. The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Arnhem-Nijmegen region reviewed this study (File nr 2019–5539) and the local ethics committees of the participating organizations gave their approval.

In phase I, step 1 (beyond the scope of this paper) persons with apathy were provided with verbal and written information and were able to ask questions, as were their FCs and PCs. However, it came became clear the persons with apathy were unable to give informed consent due to cognitive and communication issues. With permission of The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Arnhem-Nijmegen region (2019–5539), we than adjusted the inclusion procedure for persons with apathy and asked for informed consent of their legal representative.

All participants received written and face-to-face information, were able to ask questions and were asked to provide written consent before participation. Participants were free to participate in MRC phase I, II or both.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

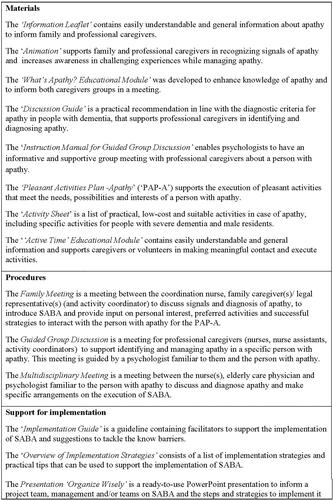

Ten persons with apathy and dementia were included in the intervention (see ). The recruitment procedure is described in detail elswhere (Nijsten et al., submitted). In the feasibility study, seven family and four professional caregivers participated in an interview, each lasting between 43 and 105 min. Eleven professional caregivers participated in a focus group discussion that lasted 90 min (see for participant characteristics).

Figure 1. Flowchart recruitment participants feasibility study.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants feasibility study.

Phase I: intervention development

As step 1 of IM, we performed a needs assessment with stakeholders in a previous study (Nijsten et al., submitted). Three themes were identified that need to be addressed to enhance the identification and management of apathy: A) relevance of signals: appraising signals of apathy in people with dementia is difficult for caregivers; B) the impact on well-being: the perceived impact of apathy varies per stakeholder; and C) skills and capabilities: dealing with apathy requires adjusting one’s expectations, appreciating little successes, and striving for meaningful contact.

For step 2, the project team defined six behavior aspects in both caregiver groups that needed to be addressed by the intervention: 1) attitude (recognizing the negative consequences of apathy), 2) knowledge (knowing what apathy is and how to identify apathy in people with dementia), 3) experience (reflect on how apathy impacts one’s own feelings as a caregiver), 4) outcome expectations (expecting that specifically targeting apathy will increase the well-being of Persons with apathy and their caregivers), 5) skills (demonstrating the ability to act on and manage apathy) and 6) self-efficacy (believing and expressing confidence in the ability to manage apathy).

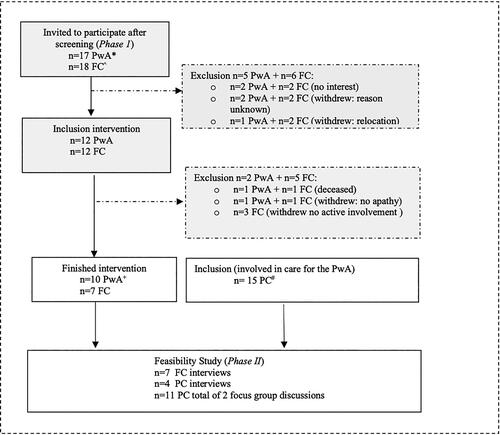

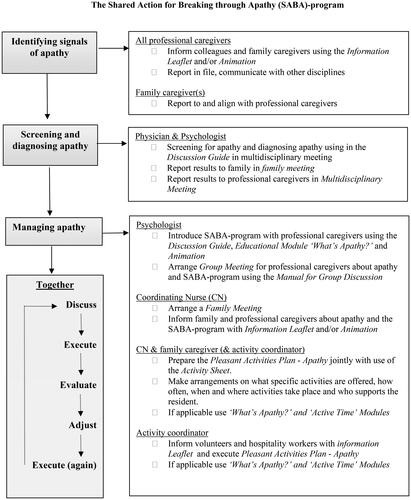

Next, in step 3, we selected different behavior change techniques to address the targets of step 2: participatory problem-solving, belief selection, active learning, tailoring, raising consciousness and using visual material (Kok et al., Citation2017). These formed the basis for the development of materials (see : SABA toolbox for details) and procedures of SABA (see for a graphical representation).

Figure 3. Graphical representation of the SABA-program.

Bold: activity of SABA; Underlined: participant; Italic: procedures and materials of SABA.

The Information Leaflet, Animation, ‘What’s apathy? Educational Module’ and the Apathy Guide were designed to overcome a lack of knowledge and support identifying apathy by family and professional caregivers, and were in line with the diagnostic criteria for apathy in people with dementia (Miller et al., Citation2021). These targeted theme A of the needs assessment and the behavioral change targets concerning attitude (1) and knowledge (2).

Guided by theme B of the needs assessment and the behavioral change targets of (3) experience and (4) outcome expectations, the Animation and the Manual for Group Discussion were developed.

Finally, resulting from theme C and the behavioral change targets of skills (5) and self-efficacy (6), we developed practical materials to support caregivers in managing apathy: the Pleasant Activities Plan-Apathy (PAP-A), the Activity Sheet and the ‘Active Time’ Educational Module.

For the design of the program in step 4 of IM, the local working groups gave direction to the form and content of the different materials and procedures of SABA. They monitored the suitability of materials and procedures for caregivers with different professions or educational backgrounds. The project team ensured that the tasks and roles within SABA were clear and appropriate for all stakeholders.

Finally, as step 5 of IM, we composed the feasibility study. Therefore, we integrated the practice-based experiences of the project team and local working groups to make the implementation of SABA suitable for each organization and participating unit. Due to discontinuity of important ambassadors within one organization, the local working group decided to reassign the intervention to another unit and location within the same organization.

Phase II: assessment of feasibility

Qualitative results regarding Bowen et al.’s elements

All stakeholders reflected on the procedures and materials of SABA as well as their collaboration, if applicable.

Demand

Both caregiver groups mentioned that a specific intervention targeting apathy in persons with apathy was likely to be used. They had been looking forward to collaborating and expressed their hope that SABA would provide extra attention and activities for persons with apathy.

Yes, but what I am afraid of is that- I believe that, erm, you can still achieve things- something with him. But he is, of course… yes, look, if someone is apathic and just sits there in that chair, then, at those moments, I guess he doesn’t ask for much attention, and then he is… yes, he’s somewhat overlooked, and then, I guess, the attention goes to someone else. Erm, and that is sorry. (Family caregiver 01)

Acceptability

When asked about their experiences, both caregiver groups were satisfied with the procedure of organizing a family meeting at the start of the intervention. Professional caregivers also mentioned that the group meeting guided by the psychologist was helpful for better recognizing apathy and understanding its effect on their interaction with the person with dementia.

Yes, I recall that ‘[family] meeting. It was a nice meeting in which a lot of questions were asked, concerning my mother personally. (Family caregiver 02)

Both caregiver groups were highly satisfied with most of the intervention materials developed. They thought that the materials were promising, had great potential and benefits and therefore should be made available for all family and professional caregivers. They also suggested that the materials could be useful for people with dementia in general and people in NHs with apathy but without dementia.

Erm, I think it is explained very clearly, also with those, like, animation figures. And also, that you become aware that like, gosh, actually you can still do something.’ (Family caregiver 01)

Regarding their collaboration in executing SABA, both caregiver groups appreciated their interaction during the family meeting at the start of SABA. However, family caregivers would have preferred to be involved and informed spontaneously more often during the execution of SABA. Nonetheless, when family caregivers specifically asked for additional information, this was provided by professional caregivers. Professional caregivers were satisfied about the collaboration with family caregivers, although their involvement was diverse and some family caregivers and legal representatives of an administration office were not in close contact with the persons with apathy.

Yes, these family caregivers are not very involved. So, I think that makes it [executing SABA] more difficult. I think, if you have family that is very involved, it is easier to have a conversation like ‘gosh, we want to plan things [activities] in a structured manner’ so, like, someone expects we are going to do that, do you want to participate? And for these two ladies that isn’t the case, so that makes it quite difficult. (Professional caregiver 01)

Implementation

We identified three themes in the qualitative analysis regarding barriers and facilitators to implementation: (1) intervention aspects, (2) the expertise and involvement of stakeholders and (3) organizational and external aspects.

Theme 1 ‘intervention aspects’ included aspects of the design and content of materials as well as the procedures and collaboration between caregivers. The face-to-face family meeting in which information on SABA and preferences of the person with apathy were exchanged, was regarded as facilitating, as were the small-scale activities that could be integrated in care routines, matched preferences and daily routines of the persons with apathy and skills of the caregiver.

Yes, that you’re given suggestions, ideas of what you could do. I see plants here [on activity sheet] so next time I’ll bring a watering can! (Family caregiver 03)

Both caregiver groups mentioned that the attractiveness, clarity and practicality of the SABA materials were supportive for implementation.

Well, that notebook with activities that I’ve written down, because it’s very nice to see what suits the client… that you don’t have to find out for yourself and, erm, some [caregivers] think too complicated, while it [activity] can be very small. (Professional caregiver 02)

However, barriers were also mentioned, namely the lack of regular consultation between family and professional caregivers during SABA as the family meeting was executed at the start of the intervention, family meetings by telephone and family caregivers missing a copy of the PAP-A.

Maybe they [professional caregivers] could have planned another moment of contact in between. ‘Guys we did this, we are going to do that, or we’re still planning to…’ having a moment of reflection somewhere. (Family caregiver 04)

Theme 2 ‘the expertise and involvement of stakeholders’ concerned the expertise of both caregiver groups, as well as their involvement in executing SABA and prioritizing attention for apathy. Both caregiver groups mentioned that having sufficient expertise was important and necessary to manage apathy. They stated that a low educational level or lack of experience in dementia care of caregivers and volunteers could have hindered the execution of SABA. However, they considered the ‘Active Time’ Educational Module to be supportive in enhancing knowledge and facilitative for the execution of the PAP-A.

Yes, colleagues mentioned that even when it said so [on the PAP-A] like ‘have a chat’, the actual question was ‘how?’ and ‘What should I talk about with this client?’ I must say that it wasn’t so clear to me in advance that this would be a difficult step, so, yes, in hindsight, I think… erm… (Professional caregiver 03)

Both caregiver groups mentioned the level of involvement as important for the implementation of SABA. According to both caregiver groups, multidisciplinary collaboration, the involvement of all team members and the support of an ‘ambassador’ were facilitating aspects. By contrast, less involvement of the psychologist and physician, other team members or family caregivers was mentioned as a possible barrier.

No. No… but that is because the psychologist has helped us here and has pointed us in the right direction. Look, if you must do that all by yourself, then it can be quite a puzzle, and you think ‘yes, and now what?’ But because we have been supported well, erm… yes I think that changes things quite a lot. (Professional caregiver 01)

Regular evaluation with team members and encouraging each other motivated professional caregivers in implementing SABA. They also mentioned that integrating small-scale activities in regular care routines was facilitating. At the same time, both caregiver groups expressed worries about the long-term sustainability of SABA and feared that prioritizing attention for apathy might be difficult in case of staff shortages, high workload or the presence of residents with challenging behavior in a unit. Family and professional caregivers considered it a barrier if agreements were unclear regarding who, when or how SABA would be executed.

Yes, I just keep finding it [SABA] very useful, but I notice when there are three or four new clients with challenging behavior, then this [SABA] really gets the worst of it, erm, at least that’s what I experienced. (Professional caregiver 04)

Theme 3 ‘organizational and external aspects’ included a physical environment with different possibilities—like access to a garden or kitchen—which was considered facilitating. Other facilitating aspects of the environment were a small number of residents living in a unit, a small-scale living room and an appealing atmosphere in the living room. Furthermore, good accessibility to SABA materials and supplies for activities was considered to be facilitating. By contrast, a large-scale unit, a large living room and limited access to materials or supplies for activities were considered barriers.

Hospitality workers don’t have access to the personal file of the resident. They need a daily chart with clear instructions what to do with whom today. (Professional caregiver 05)

The COVID-19 measures were mentioned as a major barrier in the execution of the SABA program as such measures threatened the continuity of the intervention phase and affected meetings, communication and collaboration between caregivers. Other barriers were the high workload and turnover of the professional caregivers involved. By contrast, professional caregivers who were especially assigned to support hospitality and activities in the living room facilitated executing SABA.

Practicality

When asked about the extent to which SABA was carried out as intended, all but one family caregiver mentioned having had a family meeting with the psychologist and coordinating nurse (CN) at the start. According to caregivers, this meeting focused on an explanation of the intervention, sharing information on the resident’s former life, character, interests and possibilities for activities. Two out of eleven family meetings took place online or by telephone due to COVID-19 measures. Additionally, professional caregivers stated that guided group meetings took place to discuss the apathy of the person with dementia, inform team members about SABA, formulate goals for activities and motivate colleagues.

Participants were asked if they followed procedures and had seen or used the different materials during the intervention. Regarding the Information Leaflet or Apathy Guide, family and professional caregivers did not recall having seen them at all, or they could not recall the content. All professional caregivers mentioned having seen the Animation. Three family caregivers mentioned having seen the Animation, while the others were interviewed before the completion of the Animation. The PAP-A was mostly filled in by or with support of the psychologist using input from a family meeting and/or group meeting. Two family and two professional caregivers recalled having seen the Activity Sheet and used it to fill in the PAP-A. According to professional caregivers, the reporting and documentation possibilities in the electronical files of the persons with apathy were not used optimally, neither was the use of the Apathy Guide in Multidisciplinary Meetings.

Integration

When asked about their experiences regarding the extent to which SABA can be integrated in daily care, both caregiver groups stated that SABA could easily be integrated in existing working processes and routines. They mentioned that the procedures and materials of SABA were supportive for working in a methodical way, which was considered important for the quality of care.

Yes, and I also think the things you provide don’t necessarily need to take a lot of time. If I put on his headphones and play music, yes, that takes less than a minute, so to speak. But he benefits from it. Only, you need to put some effort into it, to figure out, like, what works. (Family caregiver 01)

Limited evaluation of efficacy

Qualitative results

In terms of Bowen et al.’s ‘limited efficacy’, the different stakeholders found SABA to be promising. According to all family and professional caregivers, persons with apathy responded positively to the intervention.

I notice that, the resident turns towards those people [caregivers] that try to break through it [apathy], thus executing the plan. There develops more of a bond. They link them to an activity or doing something together. And then it becomes more easy. (Professional caregiver 02)

Family caregivers mentioned that SABA was promising for them as it empowered them to have a more conscious and deliberate approach towards apathy in a person with dementia.

Erm, I try to involve her in things more. And to tell more and… erm… For example, we sometimes take the birthday calendar down and talk about it. ‘Look who is almost having a birthday, shall we send her a birthday card? Here, write your name on it.’ Before she always said: ‘You write it’, but now I try to let her do it herself, and then she got a card back from this gentleman who used to do a lot of things for her in the past. And, ah, that is so happy and so glad and everything. (Family caregiver 05)

Additionally, all professional caregivers mentioned SABA as promising in terms of its contribution to increasing the awareness and knowledge of apathy and their empowerment in how to manage apathy. They described having come to realize that small-scale activities and efforts matter for persons with apathy, whereas before SABA they thought that managing apathy required considerable effort and/or organizing major activities.

Erm. I think in some situations I just thought that the person with apathy just wasn’t in the mood and was fine with not doing anything substantial. And that so you might soon underestimate that this is in fact apathy rather than unwillingness. (Professional caregiver 02)

Quantitative data

Unfortunately, for all but one resident some or all of the questionnaire data were missing. Therefore, we cannot report adequately on these data. Reasons for missing data varied, including one or more items or questionnaires being missing, family caregivers or legal representatives not completing the questionnaires because they were not actively involved, or the date of completion before and after the intervention overlapped (see Appendix C, supplementary material, for details).

Discussion

To the authors’ best knowledge, this is the first study to develop and evaluate a specific program to identify and manage apathy in people with dementia in co-creation with stakeholders. According to family and professional caregivers, SABA was feasible to help them to identify and manage apathy in people with dementia living in NHs. Family and professional caregivers emphasized that the form, quality and content of the materials and procedures developed met their needs and empowered them in maintaining meaningful contact with the persons with apathy. Previous research has shown the importance of the self-efficacy and empowerment of family and healthcare professionals (Johansson et al., Citation2014; Smaling et al., Citation2023; van Corven et al., Citation2021) and the SABA program provided procedures and materials to help to overcome a lack of knowledge, enhance consciousness, manage expectations and support the skills of caregivers.

Despite family and professional caregivers’ willingness to be involved, the collaboration between them was suboptimal. This study provides the insight that some family caregivers desired more feedback and active participation during the intervention, while other family caregivers or legal representatives were not closely involved in daily care, thus making it difficult to provide input. This is in line with previous research highlighting the impact and complexity of involvement of family caregivers while executing and implementing care programs (Groot Kormelinck et al., Citation2021). It also underlines that professional caregivers need to involve family caregivers, while being sensitive to their individual preferences in communication and collaboration (Laver et al., Citation2017; Tasseron-Dries et al., Citation2021; van Corven et al., Citation2022). However, this demands competencies that should receive more attention than is currently the case in their professional training (Hoek et al., Citation2021).

Strengths and weaknesses

A key strength of our study is the methodological combination of several research frameworks with practice-based experiences for the development and feasibility evaluation of SABA. Simultaneously, experiences from clinical practice provided input to enhance practice-based evidence. Another strength is the explicit involvement of important stakeholders, which is regarded as an essential—but difficult-to-apply—element within intervention research (Skivington et al., Citation2021). Building on a thorough needs assessment, stakeholders participated in the steps and phases of the development and testing of the materials, procedures and collaboration in executing the intervention. As a result, the final version of SABA is accessible, practical, applicable and integrable into standard working procedures and routines, with materials and procedures that match the needs of family as well as professional caregivers. The rich qualitative data of this study revealed that caregivers were very positive about the content, diversity and presentation of the materials and procedures developed. SABA thus shows potential in successfully identifying and managing apathy in NHs.

However, one limitation of this study is that the intervention was tested and evaluated on a small scale, and thus the results should be interpreted with caution. In addition, traditional research methods with questionnaires, may only capture the effect of an intervention when admitted shortly before, during and after an intervention, before an effect on apathy wanes off. Additionally, in future, measurements that can track behavior in real time (e.g. observations) might be preferable to capture the effect of an intervention on apathy. Although qualitative data indicated possible effectiveness for all stakeholders, the incomplete quantitative data constrained a thorough evaluation of the limited efficacy, and more research is needed to determine this aspect of feasibility. Nevertheless, we believe that the participants in this study are a small but representative sample of both family and professional caregivers in Dutch NHs nowadays, with similar variation in age, educational level and relationship to the person with apathy and caregivers mostly being female.

Furthermore, intervention research in long-term care facilities is known to be complex (Appelhof et al., Citation2018; Groot Kormelinck et al., Citation2021; Tasseron-Dries et al., Citation2021; van Corven et al., Citation2022), as underlined by our study. Despite the study design enabling us to adapt to and integrate the complex context of long-term care facilities as much as possible, not all factors could be addressed. For example, the lack of continuity in executing the intervention might have influenced the results of this study. First, the COVID-19 pandemic caused an important hitch in the execution of the intervention as it started, stopped and restarted again six months later, thus requiring additional effort to prioritize the study in light of daily actuality within an organization. Second, in the meantime there was staff turnover and a relocation of an intervention unit, which might have influenced the motivation of stakeholders to contribute to executing the intervention and data collection.

Future directives and practical implications

Persons with apathy are dependent on others to overcome apathy, whereby this effect wanes over time (Smaling et al., Citation2023; Treusch et al., Citation2015). Therefore, continued effort and attention by family and professional caregivers regarding identifying and managing apathy is important. To support this, the procedures of SABA are made compatible with the usual way of working. We advise structural screening and multidisciplinary evaluation of apathy to become part of the usual care in NHs, in addition to the evaluation and management of more pronounced challenging behavior. Moreover, the materials can support small-scale and practical activities that meet the preferences and possibilities of the Persons with apathy as well as the family and professional caregivers. SABA thereby enables caregivers to provide person-centered care, which is known to be important for the well-being of people with dementia (Milte et al., Citation2016; Reid & Chappell, Citation2017; Tasseron-Dries et al., Citation2021).

Implementing interventions in NHs is known to be difficult (Groot Kormelinck et al., Citation2021), as underlined by the barriers presented in our results. Therefore, we advise using the implementation guide to support the implementation of SABA in Dutch NHs to account for possible facilitators and barriers resulting from our study. Besides, SABA is made freely accessible to support further dissemination. Moreover, to enhance the collaboration between family and professional caregivers, we recommend careful communication about mutual expectations and interim evaluations during the execution of SABA, taking into account the needs and possibilities of both caregiver groups. Furthermore, our study suggests that the physical environment, interior and availability of supplies for activities can facilitate the management of apathy for caregivers. Healthcare organizations could support this with a vision and policy in NHs where its residents and their caregivers live, recreate and work with pleasure.

The findings in this study indicate that SABA might be generalizable for use in other groups of NH residents. The elements to enhance the knowledge and skills of stakeholders in performing activities might be useful for people with dementia in general. Other elements were suggested to be useful for other resident groups in NHs, like those with young onset dementia (Appelhof et al., Citation2017) or without dementia but with apathy as important feature, like people with Parkinson’s disease or Korsakov’s Syndrome (Pagonabarraga et al., Citation2015; van Dorst et al., Citation2021). The sense of competence is a strong and consistent predictor of caregiver burden (Kieboom et al., Citation2023), and apathy is known to be especially challenging for caregivers of persons with apathy living at home (Chang et al., Citation2021). As our study indicates that SABA can empower family caregivers in identifying and managing apathy, future research could investigate whether and how the SABA program can positively influence the well-being of Persons with apathy and their caregivers living at home to reduce caregiver burden and thereby delay or prevent admission to an NH.

Moreover, to increase awareness and take action in addressing apathy in NHs, it is necessary to educate nurses, activity coordinators, psychologists and physicians. Therefore, it is useful to investigate how SABA could be integrated into the educational curricula of these professionals.

Finally, future research should target investigating the effects of SABA by means of a large-scale randomized trial to evaluate the fidelity and quality of the intervention, the mechanisms of change and context, as suggested as a next step in the MRC framework (Skivington et al., Citation2021).

Conclusion

SABA is a promising intervention to identify and manage apathy in persons with dementia and can thereby positively influence the well-being of different stakeholders. Apathy in people with dementia calls for action and SABA provides practical procedures and materials to support family and professional caregivers in increasing their awareness and skills when caring for persons with apathy. The effects of SABA on well-being could be investigated in future research. For implementing SABA, it is important to consider the facilitators and barriers revealed in our study.

Authors’ contributions

Johanna M.H. Nijsten: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analyses, Writing- Original draft preparation. Annette Plouvier: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analyses, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. Martin Smallbrugge: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. Roeslan Leontjevas: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. Raymond T.C.M. Koopmans: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. Debby L. Gerritsen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Project administration.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (94.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants. Our special thanks go to Femke Muller and Dorien Hofenk for their support in (part of) the data collection and Lilian van Dinther-Grijsseels and Maartje Kokx for their support and constructive teamwork.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interests concerning this article.

Data availability statement

Data are available for use by other researchers upon reasonable request.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2023.2256616)

Additional information

Funding

References

- Appelhof, B., Bakker, C., Van Duinen-van den Ijssel, J. C. L., Zwijsen, S. A., Smalbrugge, M., Verhey, F. R. J., de Vugt, M. E., Zuidema, S. U., & Koopmans, R. (2017). The determinants of quality of life of nursing home residents with young-onset dementia and the differences between dementia subtypes. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 43(5–6), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1159/000477087

- Appelhof, B., Bakker, C., van Duinen-van den, I. J. C. L., Zwijsen, S. A., Smalbrugge, M., Verhey, F. R. J., de Vugt, M. E., Zuidema, S. U., & Koopmans, R. (2018). Process evaluation of an intervention for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in young-onset dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(8), 663–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2018.02.013

- Azhar, L., Kusumo, R. W., Marotta, G., Lanctôt, K. L., & Herrmann, N. (2022). Pharmacological management of apathy in dementia. CNS Drugs, 36(2), 143–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-021-00883-0

- Bartholomew, L. K., Parcel, G. S., Kok, G., Gottlieb, N. H., & Fernández, M. E. (2016). Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

- Bowen, D. J., Kreuter, M., Spring, B., Cofta-Woerpel, L., Linnan, L., Weiner, D., Bakken, S., Kaplan, C. P., Squiers, L., Fabrizio, C., & Fernandez, M. (2009). How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 452–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002

- Chang, C. Y. M., Baber, W., Dening, T., & Yates, J. (2021). He just doesn’t want to get out of the chair and do it": The impact of apathy in people with dementia on their carers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6317. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126317

- Dening, T., Baber, W., Chang, M., & Yates, J. (2022). The struggle of apathy in dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 26(10), 1909–1911. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.2008309

- Dufournet, M., Dauphinot, V., Moutet, C., Verdurand, M., Delphin-Combe, F., Krolak-Salmon, P., & Group, M; MEMORA Group. (2019). Impact of cognitive, functional, behavioral disorders, and caregiver burden on the risk of nursing home placement. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(10), 1254–1262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.03.027

- Elo, S., & Kyngas, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Gerritsen, D. L., Steverink, N., Frijters, D. H., Hirdes, J. P., Ooms, M. E., & Ribbe, M. W. (2008). A revised index for social engagement for long-term care. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 34(4), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20080401-04

- Goris, E. D., Ansel, K. N., & Schutte, D. L. (2016). Quantitative systematic review of the effects of non-pharmacological interventions on reducing apathy in persons with dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(11), 2612–2628. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13026

- Groot Kormelinck, C. M., Janus, S. I. M., Smalbrugge, M., Gerritsen, D. L., & Zuidema, S. U. (2021). Systematic review on barriers and facilitators of complex interventions for residents with dementia in long-term care. International Psychogeriatrics, 33(9), 873–889. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610220000034

- Hoek, L. J., van Haastregt, J. C., de Vries, E., Backhaus, R., Hamers, J. P., & Verbeek, H. (2021). Partnerships in nursing homes: How do family caregivers of residents with dementia perceive collaboration with staff? Dementia (London, England), 20(5), 1631–1648. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220962235

- Johansson, A., Ruzin, H. O., Graneheim, U. H., & Lindgren, B. M. (2014). Remaining connected despite separation - former family caregivers’ experiences of aspects that facilitate and hinder the process of relinquishing the care of a person with dementia to a nursing home. Aging & Mental Health, 18(8), 1029–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.908456

- Kieboom, R. V. D., Mark, R., Snaphaan, L., Assen, M. V., & Bongers, I. (2023). Influence of sense of competence, empathy and relationship quality on burden in dementia caregivers: A 15 months longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 42(3), 464–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648221138545

- Koch, J., Amos, J. G., Beattie, E., Lautenschlager, N. T., Doyle, C., Anstey, K. J., & Mortby, M. E. (2022). Non-pharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in residential aged care settings: An umbrella review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 128, 104187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104187

- Kok, G., Peters, L. W. H., & Ruiter, R. A. C. (2017). Planning theory- and evidence-based behavior change interventions: A conceptual review of the intervention mapping protocol. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 30(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-017-0072-x

- Laver, K., Milte, R., Dyer, S., & Crotty, M. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing carer focused and dyadic multicomponent interventions for carers of people with dementia. Journal of Aging and Health, 29(8), 1308–1349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264316660414

- Lavoie, P., Michaud, C., Bélisle, M., Boyer, L., Gosselin, É., Grondin, M., Larue, C., Lavoie, S., & Pepin, J. (2018). Learning theories and tools for the assessment of core nursing competencies in simulation: A theoretical review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(2), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13416

- Leung, D. K. Y., Chan, W. C., Spector, A., & Wong, G. H. Y. (2021). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and apathy symptoms across dementia stages: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 36(9), 1330–1344. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5556

- Linde, R. M., Matthews, F. E., Dening, T., & Brayne, C. (2017). Patterns and persistence of behavioural and psychological symptoms in those with cognitive impairment: The importance of apathy. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(3), 306–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4464

- Lueken, U., Seidl, U., Volker, L., Schweiger, E., Kruse, A., & Schroder, J. (2007). Development of a short version of the Apathy Evaluation Scale specifically adapted for demented nursing home residents. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry : official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(5), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180437db3

- Lutomski, J. E., Baars, M. A., Schalk, B. W., Boter, H., Buurman, B. M., den Elzen, W. P., Jansen, A. P., Kempen, G. I., Steunenberg, B., Steyerberg, E. W., Olde Rikkert, M. G., & Melis, R. J; TOPICS-MDS Consortium. (2013). The development of the older persons and informal caregivers survey minimum DataSet (TOPICS-MDS): A large-scale data sharing initiative. PLoS One. 8(12), e81673. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081673

- Miller, D. S., Robert, P., Ereshefsky, L., Adler, L., Bateman, D., Cummings, J., DeKosky, S. T., Fischer, C. E., Husain, M., Ismail, Z., Jaeger, J., Lerner, A. J., Li, A., Lyketsos, C. G., Manera, V., Mintzer, J., Moebius, H. J., Mortby, M., Meulien, D., … Lanctot, K. L. (2021). Diagnostic criteria for apathy in neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimers Dement, 17(12), 1892–1904. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12358

- Milte, R., Shulver, W., Killington, M., Bradley, C., Ratcliffe, J., & Crotty, M. (2016). Quality in residential care from the perspective of people living with dementia: The importance of personhood. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 63, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2015.11.007

- Nijsten, J. M. H., Leontjevas, R., Pat-El, R., Smalbrugge, M., Koopmans, R., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2017). Apathy: Risk factor for mortality in nursing home patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(10), 2182–2189. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15007

- Nijsten, J. M. H., Leontjevas, R., Smalbrugge, M., Koopmans, R., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2019). Apathy and health-related quality of life in nursing home residents. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 28(3), 751–759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2041-y

- Pagonabarraga, J., Kulisevsky, J., Strafella, A. P., & Krack, P. (2015). Apathy in Parkinson’s disease: Clinical features, neural substrates, diagnosis, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 14(5), 518–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(15)00019-8

- Reid, R. C., & Chappell, N. L. (2017). Family involvement in nursing homes: Are family caregivers getting what they want? Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 36(8), 993–1015. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464815602109

- Reisberg, B., Ferris, S. H., de Leon, M. J., & Crook, T. (1982). The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 139(9), 1136–1139. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136

- Ruthirakuhan, M. T., Herrmann, N., Abraham, E. H., Chan, S., & Lanctot, K. L. (2018). Pharmacological interventions for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5(5), CD012197. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012197.pub2

- Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., Boyd, K. A., Craig, N., French, D. P., McIntosh, E., Petticrew, M., Rycroft-Malone, J., White, M., & Moore, L. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of medical research council guidance. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 374, n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

- Smaling, H. J. A., Francke, A. L., Achterberg, W. P., Joling, K. J., & van der Steen, J. T. (2023). The perceived impact of the namaste care family program on nursing home residents with dementia, staff, and family caregivers: A qualitative study. Journal of Palliative Care, 38(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/08258597221129739

- Tasseron-Dries, P. E. M., Smaling, H. J. A., Doncker, S., Achterberg, W. P., & van der Steen, J. T. (2021). Family involvement in the Namaste care family program for dementia: A qualitative study on experiences of family, nursing home staff, and volunteers. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 121, 103968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103968

- Theleritis, C., Siarkos, K., Politis, A. A., Katirtzoglou, E., & Politis, A. (2018). A systematic review of non-pharmacological treatments for apathy in dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(2), e177–e192. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4783

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Treusch, Y., Majic, T., Page, J., Gutzmann, H., Heinz, A., & Rapp, M. A. (2015). Apathy in nursing home residents with dementia: Results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 30(2), 251–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.02.004

- van Corven, C. T. M., Bielderman, A., Wijnen, M., Leontjevas, R., Lucassen, P., Graff, M. J. L., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2021). Defining empowerment for older people living with dementia from multiple perspectives: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 114, 103823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103823

- van Corven, C., Bielderman, A., Wijnen, M., Leontjevas, R., Lucassen, P. L., Graff, M. J., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2022). Promoting empowerment for people living with dementia in nursing homes: Development and feasibility evaluation of an empowerment program. Dementia (London), 21(8), 2517–2535. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012221124985

- van Dorst, M. E. G., Rensen, Y. C. M., Husain, M., & Kessels, R. P. C. (2021). Behavioral, emotional and social apathy in alcohol-related cognitive disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(11), 2447. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10112447

- Zhao, Q. F., Tan, L., Wang, H. F., Jiang, T., Tan, M. S., Tan, L., Xu, W., Li, J. Q., Wang, J., Lai, T. J., & Yu, J. T. (2016). The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069