Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to provide more insight into possible barriers and facilitators caregivers of people with Huntington’s disease (HD) encounter, and what their needs and wishes are regarding a remote support program.

Methods

In total, 27 persons participated in four focus group interviews. Eligible participants were caregivers (n = 19) of a person with HD, and healthcare professionals (n = 8) involved in HD care. Qualitative data were analyzed by two researchers who independently performed an inductive content analysis.

Results

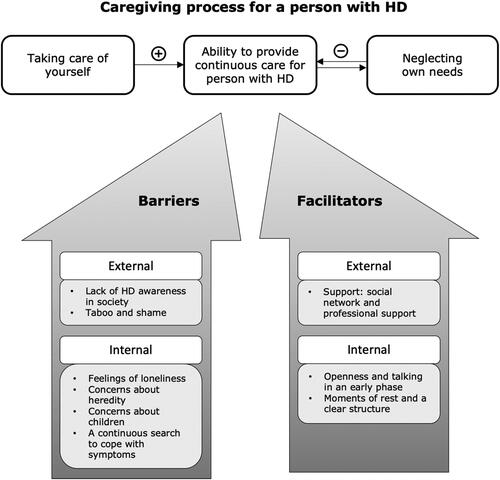

Four major themes emerged from the data, including (1) a paradox between taking care of yourself and caring for others; (2) challenges HD caregivers face in daily life, including lack of HD awareness, taboo and shame, feelings of loneliness, concerns about heredity and children, and coping with HD symptoms; (3) facilitators in the caregiving process, including a social network, professional support, openness, talking in early phases, and daily structure; (4) needs regarding a support program.

Conclusion

These insights will be used to develop a remote support program for HD caregivers, using a blended and self-management approach. Newly developed and tailored support should be aimed at empowering caregivers in their role and help them cope with their situation, taking into account barriers and facilitators.

Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a hereditary neurodegenerative disease characterized by cognitive deterioration, involuntary movements, and behavioral disturbances. The common age of onset in HD is in the range of 30–50 years (Roos, Citation2010). Due to the progressive nature of the disease, HD increasingly impacts daily life. In the early stage of the disease, persons usually are independent of direct care, live at home, and may be employed. In later stages, patients become dependent on care, and eventually, admission to a nursing or care home may be inevitable (Caron et al., Citation1998, updated 2020; Novak & Tabrizi, Citation2010). The median survival rate after disease onset is 17–20 years (Roos, Citation2010).

The disease not only affects the lives of people affected by HD, but also severely impacts the lives of those surrounding them (Domaradzki, Citation2015; Parekh et al., Citation2018). In many ways, caring for a person with HD is similar to caring for someone suffering from other neurodegenerative disorders, such as dementia or Parkinson’s disease (Roland & Chappell, Citation2019; Williams et al., Citation2012). Caregivers can experience loss of a meaningful relationship with the affected person, role reversal, or loss of social contacts (Daley et al., Citation2019). They often show declining health, including signs of anxiety, depression, stress, and reduced quality of life (Aza et al., Citation2022; Simpson & Carter, Citation2013). However, some aspects of HD create additional challenges for caregivers of people with HD (Aubeeluck et al., Citation2012). Firstly, HD onset usually occurs much earlier in life than in other neurodegenerative disorders. The informal caregiver will likely become forced to take over roles and responsibilities, such as caring for children and being the breadwinner. Secondly, HD has a 50% chance of genetic transmission, which may cause uncertainty and worries in families. Caregivers can be family members such as parents, children, or siblings who may also be confronted with the disease (Aubeeluck et al., Citation2012; Mand et al., Citation2015). Finally, in families, caregivers may care for more than one person with HD, emphasizing an increased burden.

Various studies have been conducted to investigate the impact of HD on family caregivers (Domaradzki, Citation2015; Parekh et al., Citation2018). Frequently cited aspects include the impact of role change, isolation, neglected needs and an experienced lack of support (Aubeeluck et al., Citation2012; Røthing et al., Citation2014; Williams et al., Citation2012). Caregivers of people with HD showed a need for support in balancing stressors from both caregiving and everyday life (Domaradzki, Citation2015; Røthing et al., Citation2015). In the Netherlands, there are two programs developed to support caregivers. One is called the HD Patient Education Program, which aims to educate and train patients and caregivers in developing coping strategies to improve their quality of life (A’Campo et al., Citation2012). The second program is called the Hold me Tight program, which aims to enhance partner relationships (Petzke et al., Citation2022). However, services are not always readily available due to geographic, monetary or personnel barriers (Edmondson & Goodman, Citation2017). Also, they are not designed for individual purposes.

It is necessary to anticipate on a world where we face a shortfall in healthcare professionals and a rising demand for informal and individual care at home. Online support is rapidly increasing in healthcare to overcome these changes. Especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been heightened emphasis on seeking innovative ways to continue providing support, such as using remote support (Jnr, Citation2020). Given the active phase of life of younger caregivers, as well as the taboo on HD, individual online programs could provide opportunities to cost-effectively support HD caregivers, even in remote areas. Inequities in access to post-diagnostic support contribute to difficulties in seeking and receiving the support caregivers need (Dorsey et al., Citation2018). By enhancing access and expanding the reach of support, it becomes possible to improve the provision of support which is particularly valuable for rare diseases such as HD. To design such a program, we aim to provide more insight into what specific barriers and facilitators caregivers encounter when caring for a family member with HD, and what their needs and wishes are regarding a remote support program.

Methods

In this focus group study, caregivers of persons with HD and healthcare professionals were included. Findings are reported according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Participants

Eligible participants were self-identified informal caregivers of a person with HD or healthcare professionals involved in HD care; 18 years of age or older; Dutch-speaking; and having access to the internet to participate in the online focus group. Participants were recruited through healthcare professionals and experts working at specialized HD centers in the Netherlands. Additionally, a call on the website and social media of the Dutch HD Association and the Dutch HD Knowledge Center was published. All who applied to participate met the inclusion criteria.

Participants were given an information letter and, if willing, were called by the research team to answer any additional questions. Participants gave online informed consent for inclusion before participation in the study. The study protocol (non-waiver) was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Maastricht University Medical Center (#2020-2233), The Netherlands.

Procedures

Focus groups were chosen to explore and discuss various perceptions and experiences. Participants may be more willing to share experiences because focus groups may feel less threatening than individual interviews (Onwuegbuzie et al., Citation2009). As advised by the principles of the Experience-Based Co-Design (EBCD) approach, both caregivers and healthcare professionals were involved in the focus groups (Bate & Robert, Citation2006). The aim was to organize three-to-four focus groups containing six-to-ten participants each. After the fourth focus group, the research team established that the point of data saturation was achieved (Hennink, Citation2007). The focus groups were held online, using the video conferencing tool Zoom (Almujlli et al., Citation2022). Participants received written instructions in advance on how to use Zoom, and were offered the opportunity to test it beforehand.

Data collection

A semi-structured topic guide was used during the focus groups (see Appendix A). Topics were derived from the literature and brainstorming sessions in which all research team members were involved. Specific attention was paid to creating a logical sequence of open-ended questions to stimulate discussion and equal participation of every participant. The topic guide included questions regarding (work-related) experiences with HD, accompanying changes and challenges in daily life, facilitators and barriers while coping with HD, and needs regarding a support program. Two experienced focus group moderators (LMMB and AAD) guided two focus groups each, and an assistant (MMJD) took additional notes. None of them had a prior relationship with the participants. All focus groups were audio-recorded and lasted around 90 min. Following an iterative approach and to ensure investigator triangulation, data collection was discussed by the research team after each focus group to refine the topic guide or procedures if needed.

Data analysis

We conducted a phenomenological study using focus groups to explore the unique and lived experiences of HD caregivers (Savin-Baden & Howell-Major, Citation2013). Data resulting from the focus groups were transcribed ad verbatim. To ensure analyst triangulation, transcripts were analyzed independently (MMJD and LMMB) using the software Atlas.ti version 9. An inductive content analysis was performed to allow themes and categories to flow from the data rather than using preconceived categories (Kondracki et al., Citation2002). The data was openly coded to map all aspects of the content. The two authors who performed the analyses discussed and compared the code definitions and code structure to reach consensus. They independently grouped the codes into higher-order themes and created a mind-map. These were then discussed together with the other authors to derive the main and subcategories. In a last meeting, all authors discussed and verified the end results and the first and second author continuously checked if all meaningful data were coded, no codes were established without meaningful data, and no new information emerged from the data to establish data saturation (Hennink, Citation2007). Research team members vary in background and expertise, covering multiple years of experience in clinical experience in HD, research on HD and experience in qualitative analysis and research.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 27 persons participated in the study, including 19 caregivers (age range 29–72 years), and eight healthcare professionals (age range 29–61 years). Four online focus groups were scheduled with respectively nine, five, seven, and six participants. represents their characteristics. Each focus group had a mixture of caregivers and healthcare professionals. Respectively, from the first to the fourth focus group: six, four, five, and four caregivers participated, and three, one, two, and two healthcare professionals participated.

Table 1. Characteristics of the HD caregivers and healthcare professionals.

Main themes

The focus groups resulted in four major themes, including (1) a paradox between caring of yourself and caring for others; (2) challenges HD caregivers face in daily life; (3) facilitators in the caregiving process; and (4) needs regarding a support program. A schematic representation of the first three main themes and associated categories is presented in .

The care paradox

Caregivers and healthcare professionals stated that caring for yourself and maintaining your own valued activities is required to continue caring for a loved one with HD. It is essential to create space and time to meet your own needs. They stressed the importance of living your own life and guarding your boundaries.

‘You must make sure you keep control of your own life. Try to stay strong, choose for yourself, make sure you recharge yourself, keep doing your hobbies, and make sure you do things outside your home.’ – Caregiver of her husband with HD

‘It is crucial to take good care of yourself. It is also important for the person with HD to know what you need to keep providing care because it becomes very difficult for them, especially at a later stage. Caregivers should be more egocentric and be aware they have a heavy task relying on their shoulders for the upcoming years.’ – Psychologist

However, caregivers often ignore and compromise their needs when caring for their loved one with HD. Putting aside their needs and trying to optimize the situation for their loved one makes it even more challenging to find a balance in daily life. When the balance is skewed, caregivers tend to efface or even lose themselves by organizing everything around the person with HD.

‘We used to do a lot with friends, but that is too intense for her now. Therefore, I limit my social contacts as well. I think that’s very unfortunate. Taking care of her means that I do less or stop doing things I used to do. I no longer do activities I used to do independently.’ – Caregiver of his wife with HD

‘I often see that caregivers dismiss themselves. They organize everything around the person with HD. In my opinion, it is important, especially at an early stage, to choose to take the freedom to live your own life, and to organize care around that, not the other way around.’ – Social worker

Long periods of not meeting own needs and putting activities aside have consequences that are often unseen by caregivers because, at the moment, it seems to be an appropriate solution.

‘I neglected myself for too long. My wife became increasingly dependent on me, so I slowly grew into a pattern that I could no longer break. At first, everything went well, but it got more and more difficult. The time I had for myself just disappeared. […] Now I’m struggling with myself. But I’m under treatment for that because I know that the caregiving will only extend’ – Caregiver of his wife with HD

On the one hand, you must take care of yourself to continue caring for others, but on the other hand, caregivers report they compromise their own needs to provide care. This reflects a ‘care-paradox’ in which family caregivers often invest to care for the person with HD above taking care of their own health, but this subsequently highly affects their ability to provide good quality and continuous care.

Challenges HD caregivers face in daily life

Several challenges were mentioned when caring for a person with HD. These challenges cause a high burden on informal caregivers and a continuous search to cope with them.

Lack of HD awareness in society

It was described that the obscurity and lack of awareness about the existence of HD seriously impacted caregivers. Others have no idea what the disease entails, participants said. Caregivers experience misunderstandings from friends, people in their neighborhood, colleagues at work, healthcare professionals such as the general practitioner, or agencies such as Social Services. These misunderstandings can lead to preconceptions.

‘It’s pure ignorance that people don’t recognize it. That is why you often hear preconceptions. When my wife is shopping, she gets comments that she is drunk early in the day.’ – Caregiver of his wife with HD

‘Your colleagues at work must acknowledge your role as a caregiver, so they understand your tasks outside work. There is simply no understanding of that in my workplace. Not at all.’ – Caregiver of his wife with HD

‘They always have to explain, explain, and explain. People have no idea at all. Caregivers already have a lot to take, and in addition to that, they must constantly explain. That takes an incredible amount of energy.’ – Social worker

Feelings of loneliness

Limited knowledge about HD and misunderstanding from the outside world can lead to feelings of loneliness among caregivers. Experiencing these feelings can also be related to other causes or circumstances. For example, it was stated several times that changes in relationships, specifically changes in roles, lead to feelings of loneliness in caregivers.

‘You often see the looks of people around you. My wife doesn’t realize that, but to me, it comes across as harsh and negative; it makes me feel lonely.’ – Caregiver of his wife with HD

‘I recognize the loneliness that -name of another caregiver- is talking about. The entire process takes a long time, and you don’t want to burden others with your grief all the time. Consequently, you postpone sharing your feelings.’ – Caregiver of her husband with HD

Furthermore, multiple caregivers mentioned that their social contacts declined over the past few years. This may be because they limit contact with others to avoid crowded situations for their loved one with HD or because their friends are less likely to contact them due to the changes in the person with HD.

‘I think friends feel restrained to seek contact. This can be due to the circumstances and that my partner is now seen as a patient. They may no longer see him as a full-fledged person in a group of friends.’ – Caregiver of his husband with HD

Taboo and shame

Taboo and shame influence how caregivers talk about their situation, especially for migrant caregivers. They reported that their cultural background causes fear and secrecy around HD. This can lead to social isolation.

‘There is a sort of pressure of social isolation, which makes it very difficult to talk about HD openly. It is seen as something scary. Because HD is so complicated and affects many aspects of life, it is hard to discuss it in our closed Turkish community. Four out of seven children in our family have HD, but it was never talked about.’ – Caregiver of her sister with HD

‘It has to do with the atmosphere in the family. People don’t want to face it, or it is taboo to talk about it.’ – Psychologist

It was also reported that caregivers of an older generation experience feelings of shame and that this was less experienced by the younger generation.

‘My mother-in-law has always felt much shame. She was ashamed of her husband. That’s why she couldn’t talk about it with anyone. She put everything away.’ – Caregiver of her husband with HD

Concerns about heredity

Respondents described various concerns and associated dilemmas related to the inheritance of HD. For example, they find it difficult to decide whether to perform a genetic test and, if yes, when to do it. Caregivers often hesitate between knowing the result of the genetic test or not, living with certainty or uncertainty. Although, they mention that knowing the result also raises uncertainties. Making these decisions and worrying about heredity is perceived as a psychological burden.

‘At first, she chose not to perform a genetic test. I think it would have caused a great psychological burden. However, 2,5 years ago my wife had herself tested, so psychologically it remains a struggle and it changes how you think about it.’ – Caregiver of his wife with HD

Whether genetic testing had not yet been performed or people tested positive, caregivers were alert to notice possible symptoms and felt uncertain if and when the disease would manifest.

‘At first, she didn’t want to do a genetic test so she could live a normal life by the grace of the unknown. We agreed that if I suspected something, I would tell her. However, I made excuses for not seeing it, but eventually, I came to the point where I thought this is not right. She got tested and my suspicions were confirmed.’ – Caregiver of his wife with HD

Additionally, a 50% chance of inheriting HD to your children can complicate the decision to have children. Caregivers experience uncertainties whether they should have a child or not. It is pleasant that the medical world has progressed so far that, for example, in vitro fertilization (IVF) with preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) is possible. Healthcare professionals stressed the importance of making caregivers aware of these options.

‘The process of getting tested and then waiting for the results is very difficult. […]. Eventually, my husband and I decided to have a second child even after receiving a positive HD genetic test for my husband. Some people responded how we could do that.’ – Caregiver of her husband with HD

Concerns about children

Living with a person with HD affects the entire family, including children. Caregivers reported that it is sometimes hard to talk to their children about HD, because they don’t want to hurt them and feel they need to protect them.

‘I notice that fear holds me back, so I do not talk to our children. I don’t want to hurt them, but in the end, that is inevitable.’ – Caregiver of her husband and child with HD

‘My mother didn’t want to project her worries on us just because she is the mother. She wanted to keep the roles that way. Whereas we as children, we are adults too, and we have already seen that she had difficulties and problems in coping with my father, but she did not discuss that, while we wanted to carry the worries with her.’ – Caregiver of her father with HD

Although caregivers and healthcare professionals would recommend communicating openly about the disease, it can be confronting for children or they show poor bonding with their parents. At the same time, they worry about the genetic implications of HD for themselves. Families that are under high pressure of HD can sometimes fall apart.

‘Children can doubt whether the disease also affects them, making it difficult to confront their parent. It is also influenced by what symptoms there are, but if their parent for example shows aggressive or violent behavior, it can be very intense for them.’ – Social worker

‘Sometimes children or other family members gradually lose contact with each other as the disease progresses. This can happen for various reasons, for example due to poor attachment between the child and the sick parent or avoiding confrontation if severe symptoms arise.’

A continuous search to cope with HD symptoms

The symptoms displayed by the person with HD also pose challenges for the caregivers involved. They must figure out how to cope with and respond to their loved one. Symptoms that caregivers encounter in daily life include loss of empathy, lack of initiative, changes in personality, introversion, perseverative behaviors, lack of disease insight, changes in mood, uncontrolled movements, or outbursts of anger.

‘He processes all information slower, and sometimes he talks about things from the day before and if I don’t know what he means he takes it out on me. […] Due to the changes in his personality or when he is feeling stressed, he can say hurtful things. That’s also something you must deal with.’ – Caregiver of her husband with HD

Furthermore, it was highlighted that the diversity in clinical manifestations of the disease is large. How a person copes with the situation remains individual, so caregivers must find a way that works best for them. As symptoms increase and symptoms worsen over the years, care requires a high degree of adaptability.

Facilitators in coping with HD

Several factors were mentioned that facilitate the caregiving process and its associated challenges.

Openness and talking in an early phase

One of the main topics discussed was the benefits of being open about the situation and talking about HD. It stimulates understanding and support from others, creates a greater chance of maintaining social contacts, and reduces prejudice. Raising more awareness about HD stimulates acknowledgment from others about the role of a caregiver and what the disease entails. This will also facilitate communication with colleagues at work or organizations such as Social Services. Moreover, talking with children or other family members is crucial to continue providing care for the person with HD.

‘Always try to discuss things with your partner, but also with your children. Be open about how he sees things, his wishes, or his thoughts. You must talk about that, no matter how hard that may be, but you have to do it. It makes you feel like you have more control.’ – Caregiver of her husband with HD

‘We have always been very open to everyone from the start. Everyone should know what is going on instead of giving him a weird look like he is under the influence of something. […]. The more people know, the better they can help and understand’. – Caregiver of her husband with HD

Caregivers and healthcare professionals emphasized the importance of talking with each other in an early phase; as soon as the first changes become noticeable or, if possible, while the person is still healthy. This will lower the threshold of asking for support at a later stage and will also reduce the chance of claiming behavior in the future of the person with HD, because more people are aware of and involved in the situation. Sensitive topics are also important to discuss, such as dealing with certain symptoms (e.g. aggressive behavior), medication use, daycare, or admission to a nursing home.

‘One of my clients told me she had benefited from talking to her husband at a very early stage about things that could happen and how her husband thinks about that. For example, about medication use or what to do if the burden of caregiving becomes too much. Now she feels supported, she wrote those things down. Those remain difficult subjects, but luckily it helped her.’ – Psychologist

Most caregivers felt a need to share experiences and wanted to encourage peer support. Hearing the stories of others creates recognition and makes them feel like they are not alone. Discussing things with people who were going through the same was of added value to them, especially if they experienced much trouble coping with things. The different HD stages and the wide range of symptoms are experienced as both an advantage and a disadvantage in peer support, because the experiences of others may not apply to their situation, or may be confronting to hear.

‘People are in all kinds of stages of the disease. Some people just received the diagnosis and others have already lost their partner. That is very confronting, but it helps to see how others cope with certain things and what their experiences are. For me, that is of added value to hear.’ – Caregiver of her husband with HD

External support

It is crucial to receive external support from the social network and healthcare professionals. Support from family members or friends, and professionals from facilities such as daycare, were mentioned as a long-term need to ensure continuity of care. The importance of help with regulatory matters, such as arranging things with work or finances, was also mentioned.

‘Subconsciously, you take on many responsibilities. I took over many tasks for my sister, such as arranging appointments, administration, letters, and calling people. You must hand those things over, it is too much to do it on your own.’ – Caregiver of her sister with HD

However, caregivers point out that they sometimes have difficulty handing over care or consulting professional support. Several caregivers felt it was a failure to ask for help. Furthermore, entrusting caregiving to someone else can be uncomfortable because no one else knows their loved one better than they do. Another reason was the unfamiliarity with what kind of support was available or who to ask.

‘I’m worried and wondering what will happen if I’m not there with him. I know my husband better than anyone and how to approach him. It is difficult to involve someone else to take over from me for an afternoon or a day.’ – Caregiver for his husband with HD

‘I was often unaware of the support available or what kind of support would be helpful for me. If you don’t know that, then you also don’t know what to ask for.’ – Caregiver of her husband with HD

Moments of rest and a clear structure

Getting enough rest, a daily structure, and a clear schedule helps in caring for a person with HD. It is also important to schedule moments of rest during the day to allow the person with HD to recharge their batteries. When persons with HD experience mood swings or irritability, caregivers notice that it may be due to a lack of rest or because they miss a certain feeling of safety.

‘To me it is very clear whether my wife gets enough rest. In the morning, she is already a bit behind. If she has been very active, we plan a moment of rest after lunch, which works very nicely. We both experience problems if we don’t schedule that.’ – Caregiver of his wife with HD

‘He is looking for a sense of safety in different situations, for example if he must go to the care farm or if people come over. If things stay the same for him, it is also easier for me as the caregiver.’ – Caregiver of her husband with HD

Support needs

Various themes were mentioned in relation to what topics would need to be included in a tailored support program for HD caregivers. For example, caregivers preferred to gain insight into their own behavior and how this could influence the person with HD. Furthermore, how to cope with the HD symptoms, combining work and care, concerns about heredity, and consequences for children were mentioned. Attention should also be paid to the pre-diagnostic phase and the phase toward admission to a nursing home. Caregivers and healthcare professionals agreed that support should also be aimed at providing help with regulatory matters and making decisions for the future, such as regarding the disposition of property upon death or euthanasia.

‘He is no longer the person I was once married to. It is important to receive support on how to cope with a changing partner as this is very relevant for most caregivers.’ – Caregivers of her husband with HD

‘Combining work and care is often an undisputed topic. I’ve experienced several barriers to discussing things with my employer, so it would be very helpful to receive support or hear about experiences from others.’ – Caregiver of his wife with HD

Given that circumstances and HD symptoms can vary a lot between individuals, the importance of tailored support was emphasized several times. Multiple caregivers preferred online support because it saves time and is easily accessible. However, they do not want it to replace personal contacts entirely. They would like to have the possibility to rely on someone and ask questions if necessary.

‘I like it when support is offered digitally. Otherwise, you have to go somewhere, and then you lose much time. […]. All tips from others are very welcome to make the caregiving process going as well as possible.’ – Caregiver of her husband with HD

‘Support is often organized during working hours. Having something online makes it easier for me to combine it with work and care responsibilities. (…). I would like to receive tips and coaching from someone with knowledge and experience in HD care and helps me incorporate things into daily practice.’ – Caregiver of his wife with HD

Discussion

To design an HD specific, remote individual support program, the current study aimed to gain more insight into the experiences in caring for a person with HD. Results showed four main themes. The first theme is a ‘care-paradox’, meaning caregivers put their own needs aside to provide good quality care for the person with HD. However, this in turn affected their ability to provide good and continuous care. This is in line with findings from previous research, which showed that as the disease progressed, the balance between caregiving and meeting own needs was skewed, resulting in feelings of frustration, caregivers drastically reducing their own activities, and an increased need for professional care. They put their own life on hold and because the caregiving continues day and night, their own health deteriorates (Parekh et al., Citation2018; Røthing et al., Citation2015; Williams et al., Citation2009). Also, research on caregivers of people with other neurodegenerative disorders showed similar results (Clemmensen et al., Citation2021; Sullivan & Miller, Citation2015). Self-management support aimed at increased control and empowerment of the caregiver has already proven to be effective to help relatives of people with a neurodegenerative disorder to develop skills to maintain balance in daily life and prevent overburdening (Boots et al., Citation2018; Duits et al., Citation2021; Huis In Het Veld et al., Citation2015). Relatives of persons with HD could also benefit from such a self-management approach. In that way, the care paradox can be tackled, enabling caregivers to find a better balance between caregiving and meeting their own needs in daily life.

The second emerging theme is the challenges HD caregivers face in daily life. Several challenges were mentioned, such as the lack of HD awareness in society, feelings of loneliness, and taboo and shame. The lack of awareness and comprehension have been documented in HD and across other relatively rare neurodegenerative disorders before, such as frontotemporal dementia (Bruinsma et al., Citation2022; Roscoe et al., Citation2009; Williams et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, many family members avoided talking about HD which enhanced secrecy and increased feelings of loneliness. This has also been described in previous research among HD caregivers (Aubeeluck et al., Citation2012; Aubeeluck & Buchanan, Citation2006; Lowit & Van Teijlingen, Citation2005). The prevailing taboo and stigma surrounding neurodegenerative disorders could play a role and impede understanding and openness (Herrmann et al., Citation2018). However, the fact that a person’s cultural background may enhance this taboo and avoidance of talking about HD, as mentioned in our focus groups, has never been described before. Therefore, more cultural insight is required to prevent these factors from triggering a downward spiral in which misunderstanding, closedness, taboo and loneliness feed off each other.

Furthermore, participants mentioned caregiving often caused significant changes in roles. This is consistent with findings from previous research on HD, indicating that spouses felt they needed to take care of ‘a child’, and children could take over adult responsibilities, or in some cases, fulfill the role of the primary caregiver (Røthing et al., Citation2014). In line with research on caregivers of people with dementia, role reversals from a reciprocal relationship to a caring relationship are common (Cabote et al., Citation2015). HD caused families to fall apart, while others mention it brought the family closer together and gave them a feeling of mastery (Roscoe et al., Citation2009; Vamos et al., Citation2007). Paying attention to these positive aspects could also improve coping with HD.

Additionally, concerns about the hereditary nature of the disease were demanding for HD caregivers. Performing a genetic test has serious psychological burdens, regardless of the result. Complex and sometimes contradictory motives arise, such as reducing uncertainty, being well-informed about reproductive choices, guilt toward other family members, or fear of coping with the future disease (Crozier et al., Citation2015). People in other studies reported both positive and negative consequences after completing genetic testing, including relief from uncertainty and appreciation for the present (Williams et al., Citation2010). Non-carriers showed lower levels of hopelessness, while those who tested positive experience intense distress and showed an increased risk for depression (Gargiulo et al., Citation2009).

Furthermore, the diversity in clinical features is extensive and due to the progressive severity caregivers struggled with a continuous search to cope with them. Neuropsychiatric symptoms are significant predictors of quality of life for caregivers in many neurodegenerative disorders. Previous research shows that these neuropsychiatric symptoms are often the most distressing aspects of HD for caregivers (Karttunen et al., Citation2011; Lillo et al., Citation2012; Simpson et al., Citation2016). Additionally, people with HD being not aware of their deficits is associated with greater caregiver burden (Wibawa et al., Citation2020). Behavioral changes are often hard to discriminate as symptoms of the disease, as they are usually not attributed to a neurodegenerative disorder. Symptoms such as aggressive or agitated behaviors can be misinterpreted, leading caregivers to believe that the patient is in control of them (Isik et al., Citation2019). The impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in HD such as psychosis, obsessive and compulsive symptoms, or aggressive behavior, is expected to be particularly detrimental because these symptoms are prevalent and tend to be more severe in HD than in other neurodegenerative disorders (Leroi et al., Citation2002; Naarding et al., Citation2001; Paoli et al., Citation2017). In the absence of a cure, there is a role for interventions to educate caregivers how to cope with executive dysfunction and cognitive decline (Hergert & Cimino, Citation2021; Lowit & Van Teijlingen, Citation2005).

The third theme is facilitators in coping with HD. For example, creating a clear daily structure, sharing experiences, being open and talking in an early phase. Having more people aware of the situation will lower the threshold of asking for help at a later stage. It is known that a strong social network reduces the caregiver burden for HD caregivers (Bayen et al., Citation2023). According to the current study, receiving social and professional support was crucial for caregivers. This is consistent with findings that the negative consequences of caregiving are lessened when caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s dementia or Parkinson’s disease receive support from family or friends and use support services (Roland & Chappell, Citation2019).

The last theme in this study is the needs for support. The current study is the first to mention that caregivers preferred an online support program because it saves time and, according to them, is easily accessible. Although, they explicitly expressed that it should not replace personal contacts entirely. Having someone to turn to with questions was mentioned as an important aspect of support. The emerging topics to be addressed in a support program are in many ways similar, and therefore not new to those in existing research on experiences of HD caregivers or other neurodegenerative diseases. It, however, substantiates that experiences of caregivers of a person with HD are representative among different countries. Although, the theme ‘openness about the disease’ may need specific care since there may be cultural differences regarding this topic.

An example of an effective program that uses a blended approach and focuses on self-management strategies is the Partner in Balance program. This program has already been adapted to caregivers of people with dementia and Parkinson’s disease (Boots et al. Citation2018; Bruinsma et al. Citation2021; Duits et al. Citation2021). By combining online thematic modules with personalized coaching, the program has demonstrated its effectiveness in terms of increased self-efficacy, perceived control and quality of life compared to usual care (Boots et al. Citation2018). To make this program relevant for HD caregivers it will need to be adapted through co-creation involving caregivers and healthcare professionals. Additionally, its usability will have to be investigated. Our findings hold validity and can serve as valuable themes in such a support program for caregivers of people with HD.

Clinical implications

Providing accessible and timely care is needed to get the right information to the right person at the right time. By providing individual support remotely this will not only facilitate informal caregivers to receive support but also help healthcare professionals to easily provide the needed support. Our results provide a significant and realistic detail of HD caregiver’s experiences that would inform the provision of various care models from patient-clinician to a systematic level. Specifically, for the aim of this study, the results will be used to inform the decision-making process for the content of a blended care self-management support program for HD caregivers. A blended form combining an online self-management approach with professional contacts could be a suitable way to meet the needs of HD caregivers, and to anticipate on geographic barriers. Besides, people feel more motivated to adhere and complete online programs when a healthcare professional is involved (Wilhelmsen et al. Citation2013). Such a blended care program could be provided by social health workers or case managers working in HD care. Including healthcare professionals can facilitate the implementation process as the program could be integrated into existing HD care settings. As such, it presents an opportunity to continue to support HD caregivers, now and in the future.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study is that we organized online focus groups. Therefore, geographic and time-bound barriers to participating in on-site focus groups were excluded. Furthermore, the inclusion of both caregivers and healthcare professionals enriched the process of exploring different perceptions. It allowed participants to share and react on each other’s experiences. Most of the time, healthcare professionals answered after the caregivers. Besides that, healthcare professionals could validate the answers provided by caregivers, they also shared their professional experiences in what they notice that caregivers encounter or need support with. This in turn elicited responses and stimulated interaction between participants. The inclusion of both perspectives helps to take this into account when developing and implementing support programs where both target groups are important in these processes. However, caregivers may have felt intimidated by others or felt reluctant to openly share certain sensitive topics in an online group. To address this, we limited the group size and offered the possibility to share things afterward via email or individually. Although the study sample was heterogeneous based on the phases in their caregiving trajectory, it was mainly spouses who were included. This impedes generalizability to caregivers other than spouses, such as adult children or siblings. Although teenagers can also fulfill the role of the caregiver, they were excluded from this study. Their needs and wishes for support when growing up with a parent with HD are expected to differ compared to adults who are at a different phase of their life. Therefore, their needs will be addressed in a separate study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this focus group study showed that, apart from being open about the disease, most of the experiences in caring for a person with HD are similar as those reported in previous similar studies and therefore, don’t seem to be bound by cultural aspects. Our results provide directions for those developing or providing support, particularly when seeking a shift from a patient-clinician to a more systematic level. Specifically, for the current study, the obtained results hold significant value to be used in developing the content of a tailored and remote support program for caregivers of people with HD.

Acknowledgements

We thank the persons and organizations that helped us during the recruitment phase. Additionally, we express appreciation for the caregivers and healthcare professionals who participated. Lastly, we would like to thank Roos Roberts for making transcripts of the interview data.

Disclosure statement

Since September 2022, Mayke Oosterloo is a member of the Scientific and Bioethics Advisory Committee (SBAC) of the European Huntington Disease Network which reviews seed fund applications.

Additional information

Funding

References

- A’Campo, L. E., Spliethoff-Kamminga, N. G., & Roos, R. A. (2012). The patient education program for Huntington’s disease (PEP-HD). Journal of Huntington’s Disease, 1(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.3233/JHD-2012-120002

- Almujlli, G., Alrabah, R., Al-Ghosen, A., & Munshi, F. (2022). Conducting Virtual focus groups during the COVID-19 epidemic utilizing videoconferencing technology: A feasibility study. Cureus, 14(3), e23540. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.23540

- Aubeeluck, A., & Buchanan, H. (2006). Capturing the Huntington’s disease spousal carer experience: A preliminary investigation using the ‘Photovoice’ method. Dementia, 5(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301206059757

- Aubeeluck, A. V., Buchanan, H., & Stupple, E. J. (2012). ‘All the burden on all the carers’: Exploring quality of life with family caregivers of Huntington’s disease patients. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 21(8), 1425–1435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-0062-x

- Aza, A., Gómez-Vela, M., Badia, M., Begoña Orgaz, M., González-Ortega, E., Vicario-Molina, I., & Montes-López, E. (2022). Listening to families with a person with neurodegenerative disease talk about their quality of life: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 20(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-022-01977-z

- Bate, P., & Robert, G. (2006). Experience-based design: From redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 15(5), 307–310. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.016527

- Bayen, E., de Langavant, L. C., Youssov, K., & Bachoud-Lévi, A. C. (2023). Informal care in Huntington’s disease: Assessment of objective-subjective burden and its associated risk and protective factors. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 66(4), 101703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2022.101703

- Boots, L. M., de Vugt, M. E., Kempen, G. I., & Verhey, F. R. (2018). Effectiveness of a blended care self-management program for caregivers of people with early-stage dementia (partner in balance): Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(7), e10017. https://doi.org/10.2196/10017

- Bruinsma, J., Peetoom, K., Bakker, C., Boots, L., Verhey, F., & de Vugt, M. (2022). ‘They simply do not understand’: A focus group study exploring the lived experiences of family caregivers of people with frontotemporal dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 26(2), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1857697

- Bruinsma, J., Peetoom, K., Boots, L., Daemen, M., Verhey, F., Bakker, C., & de Vugt, M. (2021). Tailoring the web-based ‘Partner in Balance’intervention to support spouses of persons with frontotemporal dementia. Internet Interventions, 26, 100442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100442

- Cabote, C. J., Bramble, M., & McCann, D. (2015). Family caregivers’ experiences of caring for a relative with younger onset dementia: A qualitative systematic review. Journal of Family Nursing, 21(3), 443–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/10748407155738

- Caron, N. S., Wright, G. E., & Hayden, M. R. (1998, updated 2020). Huntington disease. In M. P. Adam, H. H. Ardinger, R. A. Pagon, S. E. Wallace, L. J. H. Bean, K. Stephens, et al. (Eds.). GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle.

- Clemmensen, T. H., Lauridsen, H. H., Andersen-Ranberg, K., & Kristensen, H. K. (2021). I know his needs better than my own’–carers’ support needs when caring for a person with dementia. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 35(2), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12875

- Crozier, S., Robertson, N., & Dale, M. (2015). The psychological impact of predictive genetic testing for Huntington′ s disease: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 24(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-014-9755-y

- Daley, S., Murray, J., Farina, N., Page, T. E., Brown, A., Basset, T., Livingston, G., Bowling, A., Knapp, M., & Banerjee, S. (2019). Understanding the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: Development of a new conceptual framework. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4990

- Domaradzki, J. (2015). The impact of Huntington disease on family carers: A literature overview. Psychiatria Polska, 49(5), 931–944. https://doi.org/10.12740/PP/34496

- Dorsey, E. R., Glidden, A. M., Holloway, M. R., Birbeck, G. L., & Schwamm, L. H. (2018). Teleneurology and mobile technologies: The future of neurological care. Nature Reviews. Neurology, 14(5), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2018.31

- Duits, A. A., Boots, L. M., Mulders, A. E., Moonen, A. J., & Vugt, M. E. (2021). Covid proof self-management training for caregivers of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 36(3), 529–530. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.28457

- Edmondson, M. C., & Goodman, L. (2017). Contemporary health care for Huntington disease. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 144, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801893-4.00014-6

- Gargiulo, M., Lejeune, S., Tanguy, M.-L., Lahlou-Laforêt, K., Faudet, A., Cohen, D., Feingold, J., & Durr, A. (2009). Long-term outcome of presymptomatic testing in Huntington disease. European Journal of Human Genetics: EJHG, 17(2), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2008.146

- Hergert, D. C., & Cimino, C. R. (2021). Predictors of caregiver burden in Huntington’s disease. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 36(8), 1426–1437. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acab009

- Hennink, M. M. (2007). International focus group research: A handbook for the health and social sciences. Cambridge University Press.

- Herrmann, L. K., Welter, E., Leverenz, J., Lerner, A. J., Udelson, N., Kanetsky, C., & Sajatovic, M. (2018). A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: Can we move the stigma dial? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(3), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2017.09.006

- Huis In Het Veld, J. G., Verkaik, R., Mistiaen, P., van Meijel, B., & Francke, A. L. (2015). The effectiveness of interventions in supporting self-management of informal caregivers of people with dementia; a systematic meta review. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0145-6

- Isik, A. T., Soysal, P., Solmi, M., & Veronese, N. (2019). Bidirectional relationship between caregiver burden and neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A narrative review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(9), 1326–1334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10443-7

- Jnr, B. A. (2020). Use of telemedicine and virtual care for remote treatment in response to COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Medical Systems, 44(7), 132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01596-5

- Karttunen, K., Karppi, P., Hiltunen, A., Vanhanen, M., Välimäki, T., Martikainen, J., Valtonen, H., Sivenius, J., Soininen, H., Hartikainen, S., Suhonen, J., … Pirttilä, T, ALSOVA Study Group. (2011). Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in patients with very mild and mild Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(5), 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2550

- Kondracki, N. L., Wellman, N. S., & Amundson, D. R. (2002). Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 34(4), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60097-3

- Leroi, I., O’Hearn, E., Marsh, L., Lyketsos, C. G., Rosenblatt, A., Ross, C. A., Brandt, J., & Margolis, R. L. (2002). Psychopathology in patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases: A comparison to Huntington’s disease. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(8), 1306–1314. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1306

- Lillo, P., Mioshi, E., & Hodges, J. R. (2012). Caregiver burden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is more dependent on patients’ behavioral changes than physical disability: A comparative study. BMC Neurology, 12(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-156

- Lowit, A., & Van Teijlingen, E. R. (2005). Avoidance as a strategy of (not) coping: Qualitative interviews with carers of Huntington’s Disease patients. BMC Family Practice, 6(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-6-38

- Mand, C. M., Gillam, L., Duncan, R. E., & Delatycki, M. B. (2015). “I’m scared of being like mum”: The experience of adolescents living in families with huntington disease. Journal of Huntington’s Disease, 4(3), 209–217. https://doi.org/10.3233/JHD-150148

- Naarding, P., Kremer, H. P. H., & Zitman, F. G. (2001). Huntingtonˈs disease: A review of the literature on prevalence and treatment of neuropsychiatric phenomena. European Psychiatry, 16(8), 439–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00604-6

- Novak, M. J., & Tabrizi, S. J. (2010). Huntington’s disease. BMJ, 340(4), c3109–c3109. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c3109

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Dickinson, W. B., Leech, N. L., & Zoran, A. G. (2009). A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800301

- Paoli, R., Botturi, A., Ciammola, A., Silani, V., Prunas, C., Lucchiari, C., Zugno, E., & Caletti, E. (2017). Neuropsychiatric burden in Huntington’s disease. Brain Sciences, 7(12), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7060067

- Parekh, R., Praetorius, R. T., & Nordberg, A. (2018). Carers’ experiences in families impacted by Huntington’s disease: A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(3), 675–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12098

- Petzke, T. M., Rodriguez-Girondo, M., & van der Meer, L. B. (2022). The hold me tight program for couples facing huntington’s disease. Journal of Huntington’s Disease, 11(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.3233/JHD-210516

- Roland, K. P., & Chappell, N. L. (2019). Caregiver experiences across three neurodegenerative diseases: Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Parkinson’s with dementia. Journal of Aging and Health, 31(2), 256–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264317729980

- Roos, R. A. (2010). Huntington’s disease: A clinical review. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 5(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-5-40

- Roscoe, L. A., Corsentino, E., Watkins, S., McCall, M., & Sanchez-Ramos, J. (2009). Well-being of family caregivers of persons with late-stage Huntington’s disease: Lessons in stress and coping. Health Communication, 24(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230902804133

- Røthing, M., Malterud, K., & Frich, J. C. (2014). Caregiver roles in families affected by Huntington’s disease: A qualitative interview study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28(4), 700–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12098

- Røthing, M., Malterud, K., & Frich, J. C. (2015). Balancing needs as a family caregiver in H untington’s disease: A qualitative interview study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 23(5), 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12174

- Savin-Baden, M., & Howell-Major, C. (2013). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice. Routledge.

- Simpson, C., & Carter, P. (2013). Short-term changes in sleep, mastery & stress: Impacts on depression and health in dementia caregivers. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.), 34(6), 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.07.002

- Simpson, J. A., Lovecky, D., Kogan, J., Vetter, L. A., & Yohrling, G. J. (2016). Survey of the Huntington’s disease patient and caregiver community reveals most impactful symptoms and treatment needs. Journal of Huntington’s Disease, 5(4), 395–403. https://doi.org/10.3233/JHD-160228

- Sullivan, A. B., & Miller, D. (2015). Who is taking care of the caregiver? Journal of Patient Experience, 2(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/237437431500200103

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Vamos, M., Hambridge, J., Edwards, M., & Conaghan, J. (2007). The impact of Huntington’s disease on family life. Psychosomatics, 48(5), 400–404. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.48.5.400

- Wibawa, P., Zombor, R., Dragovic, M., Hayhow, B., Lee, J., Panegyres, P. K., Rock, D., & Starkstein, S. E. (2020). Anosognosia is associated with greater caregiver burden and poorer executive function in Huntington disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 33(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988719856697

- Wilhelmsen, M., Lillevoll, K., Risør, M. B., Høifødt, R., Johansen, M.-L., Waterloo, K., Eisemann, M., & Kolstrup, N. (2013). Motivation to persist with internet-based cognitive behavioural treatment using blended care: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 296. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-296

- Williams, J. K., Erwin, C., Juhl, A., Mills, J., Brossman, B., & Paulsen, J. S, I-RESPOND-HD Investigators of the Huntington Study Group. (2010). Personal factors associated with reported benefits of Huntington disease family history or genetic testing. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers, 14(5), 629–636. https://doi.org/10.1089/gtmb.2010.0065

- Williams, J. K., Skirton, H., Barnette, J. J., & Paulsen, J. S. (2012). Family carer personal concerns in Huntington disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(1), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05727.x

- Williams, J. K., Skirton, H., Paulsen, J. S., Tripp-Reimer, T., Jarmon, L., McGonigal Kenney, M., Birrer, E., Hennig, B. L., & Honeyford, J. (2009). The emotional experiences of family carers in Huntington disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(4), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04946.x