Abstract

Objectives

Hospices are regarded as gold standard providers of end-of-life care. The term hospice, however, is broadly used, and can describe a type of care offered in a variety of health care services (e.g. nursing homes). It thus becomes complex for families to decide between services. We aimed to review the evidence around the experience of family carers of people with dementia accessing in-patient hospice settings for end-of-life care.

Method

We registered the review protocol on PROSPERO. We used PerSPE(C)TiF to systematically organise our search strategy. The evidence was reviewed across six databases: PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, ASSIA, ISI Web, and CINAHL. We used meta-ethnography as per the eMERGe guidance for data interpretation.

Results

Four studies were included. Two third-order constructs were generated through meta-ethnography: expectations of care and barriers to quality of care. We found that carers had expectations of care, and these could change over time. If discussion was not held with hospice staff early on, the carers could experience reduced care quality due to unmatched expectations. Unmatched expectations acted as barriers to care and these were found in terms of carers not feeling adequately supported, and/or having the person discharged from hospice, which would entail increased care responsibility for carers.

Conclusion

In view of an increase in new dementia cases over time and with hospice services being under pressure, integrating palliative care services within community-based models of care is key to reducing the risk of having inadequate and under resourced services for people with dementia.

Introduction

Prevalence estimates indicate that over 50 million people are currently affected by dementia worldwide, with figures expected to reach nearly 80 million cases within the next decade (WHO, Citation2021). As dementia progresses to more advanced stages, intensive support is needed to ensure that good quality care is provided to the person. Over time, the role of the family carer becomes central to making health care decisions, as the progressive nature of dementia leads the person to requiring support from others to express their wishes and preferences about health care options.

During the final stages of dementia, adequate end-of-life and palliative care need to be in place to ease life transition, help manage the unpredictability of behavioural psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSDs) and help alleviate sorrow and care burden to the carer (Gitlin et al., Citation2018; National Academies of Sciences & Engineering & Medicine, Citation2021).

Hospices are regarded as providers of high-quality end-of-life and palliative care, and their interdisciplinary care model is associated with better experience of care (Wright et al., Citation2008). Hospice care does not limit to only end-of-life medical support, pain management and emotional or spiritual support for patients, as they may also offer emotional support to their families in times of need (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2023).

Hospice care is quite a broad definition as it may entail a specific type of end-of-life and palliative care option that is provided at the home of the person, in long-term care, in-wards hospital, and/or in hospice in-patient care settings (National Hospice & Palliative Care Organization, Citation2021). Different care models are used internationally, with the definition of end-of-life often being made around the level of cognitive impairment of the person with dementia to understand who may need access to this type of care, rather than employing a more holistic approach to care. Advanced stages of dementia may last on average two years and the health care system does not always clearly recognize when a person has reached this stage (Browne et al., Citation2021). There are instances when the person needs end of life support before reaching more advanced stages of dementia which would lead them to increased hospitalisations and ineffective care practices until the end of their life (Browne et al., Citation2021).

Very few European countries have currently an adequate number of services providing palliative care for people with dementia (Europe Alzheimer, Citation2020). The increasing number of people requiring palliative and end-of-life care, accounting to more than 40% increase in the UK by 2040 (Etkind et al., Citation2017), with dementia being the main condition, calls for urgent changes to existing health care models and policy. This call is already part of discussion at the European-wide policy level for other conditions (Tuffrey-Wijne et al., Citation2016). Work is being directed towards dementia-specific policy changes through interdisciplinary workshops on recommendations for future palliative dementia care as in the EAPC White paper (van der Steen et al., Citation2014). Gaps in care are still experienced in hospice dementia care nonetheless (O’Connor et al. Citation2022).

Recent work has been done to review the evidence of interventions in a hospice setting (Lassell et al., Citation2022), however, to our knowledge no previous work has reviewed the qualitative evidence around the experience of receiving end-of-life and palliative care in these settings from the point of view of family carers. Carers’ experience of care may drastically change when admission to hospice is made for the person with dementia, as their identity as carer may shift from this point onwards. Exploring their experience of care may thus help understand what is needed for them to encourage a more positive end-of-life care, and find strategies to sustain their wellbeing during and after hospice dementia care. Therefore, this systematic review aims to explore the experience of end-of-life and palliative care for family carers receiving support from hospices for the person with dementia.

Review question

What is the experience of hospice care for family carers of people with dementia?

Methods

The methods were fully described in the review protocol that was registered on PROSPERO on 25 July 2022 (Bosco et al., Citation2022). We report the results of the searches on PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al. Citation2021). Our search strategy was informed by the PerSPE(C)TiF (Booth et al., Citation2019) to describe the perspective, setting, phenomenon/problem, environment, time, and findings. We systematically reviewed the existing evidence up to 14th September 2022. This was conducted on six databases covering a large variety of health and science disciplines relevant to our review: PubMed for life sciences and biomedical literature, EMBASE for biomedical research, PsycINFO for behavioural and social sciences, Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts (ASSIA), the Web of Science (ISI Web) for a multidisciplinary index on social sciences, arts and humanities, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). We further explored grey literature and the first 100 hits on Google scholar and Google search. Initial meetings were held between the qualitative researcher (AB), one health psychologist (CT), one old age psychiatrist (AB), one senior academic with research expertise on palliative care (MB) and one member of the patient and public involvement and engagement strategy group (PPIE) (MD) to agree on the analysis plan and progress of the review.

The search strategy was developed and refined in consultation with a researcher with expertise in systematic reviews of qualitative evidence (CDL). Domains and key terms were used to help with the identification of studies. Terms included ‘palliative care’ and synonyms such as ‘end-of-life care’, ‘palliative treatment’, ‘hospice care’, ‘palliative medicine’, ‘comfort care’, and acronyms such as ‘EoLC’.

The following domains of investigation were used to retrieve articles:

Dementia domain: dement*, or alzheimer*.

Participant domain: caregiv*, or relative*, or spouse*, or dyad*, or carer*, or partner*.

Support domain: Palliative* or end-of-life* or caring or comfort* or hospice*.

Research methods domain: Qual*, or experien* or interview*.

We adapted terms according to each database functionality (Appendix A for data search strategy). We further screened the first 100 hits on Google scholar and consulted grey literature on dementia and hospice care to maximise the retrieval of studies. We cross-referenced those studies reaching the full text screening phase (relevant systematic reviews and included studies).

No restrictions were applied on language nor on publication date. We planned to contact the authors of identified research protocols to check whether data had been analysed and published. Unpublished studies were considered but we planned to reference the studies’ protocols (when these were available) in our review.

Study records

All studies retrieved from available databases were screened against aims/objectives and inclusion criteria of the review. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (AB and YY), AB and CDL completed full text screening of studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

Upon completion of full text screening and inclusion of selected studies for analysis, AB extracted data onto NVivo 12 (QSR International, Citation2012). Data extraction was conducted for study design, aims, methods used for qualitative data collection and analysis, theoretical framework (if any), participants’ characteristics, and the setting used for screening. In the presence of multiple publications reporting the same study findings, we planned to only include in the analysis as primary reference, the publication reporting the most complete dataset. The remaining study report(s) would be used as secondary reference(s).

The framework by Spencer et al. (Citation2003) informed the quality appraisal of the included studies, which was conducted by two reviewers/raters (AB and CDL). This framework helped us to assess comprehensively the included studies against four principles of methodological quality in qualitative research: contributory to knowledge, defensibility in design, rigorousness in conduct and credibility in claim. The assessment for each study was graded as either low, medium or high. Discrepancies were resolved by reaching consensus among review authors.

Eligibility criteria:

The study is qualitative or contains qualitative analysis, including participants’ quotes.

The study has been peer-reviewed and published

The study reports on the experience of in-patient hospice care for dementia

No restriction on age, sex, language or year of publication.

Studies reporting on the experience of hospice care from patients with dual diagnosis alongside dementia.

We excluded studies recruiting participants with dementia through hospice settings but inquiring into other aspects of care other than hospice care (e.g. health care screening programmes). To ensure methodological rigour, we planned to exclude those study reports that did not describe adequately the methods used for data collection and/or analysis. We found it difficult to find literature on the direct experience of people with dementia of in-patient hospice care, the review findings were around caregivers’ experience of the service.

Data synthesis

Our data analysis plan has been fully described elsewhere (Bosco et al., Citation2022). In brief, we used meta-ethnography as this methodology is particularly helpful to produce new interpretations around experiences and behaviours, and it offers a structured and systematic analysis to explore how different studies are related to each other to reach deeper levels of interpretation (Noyes et al. Citation2022). We used meta-ethnography as proposed by Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) and applied Schultz’s (Citation1962) definition of third order constructs (i.e. reviewers’ interpretation), first order construct (i.e. participants’ quotes) and second order interpretations (i.e. the authors’ interpretation of participants’ quotes). We reported meta-ethnography as per the eMERGe guidance (France et al., Citation2019). We assessed the full text of each included article and focussed on their result sections for the meta-ethnographic analysis.

Phase 1. The review authors first had initial meetings to refine the protocol and search strategy. We involved an external researcher with expertise in qualitative research methods (CDL) to monitor the quality and research rigour of the analysis plan. A member of an established PPIE at the University of Manchester (MD) helped ensure that the review findings reflected real life cases.

Phase 2. The review authors refined the inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection and checked the accuracy and quality of search strategy.

Phase 3. AB organised data from the full text of the selected studies into first and second order constructs to inform the development of themes. NVivo 12 facilitated the organisations of constructs by study aims and objectives.

Phase 4. Constructs that were initially grouped as first and second orders, were further analysed for theme development. Discussions were held with the rest of review authors to start data interpretation.

Phase 5. Constant comparative methods were used for theme generation and to help reach a further layer of data interpretation (i.e., third order construct) and explore how different construct related to each other to explain social reality (Charmaz, Citation2006).

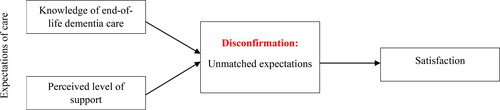

Phase 6. We used the Expectancy-disconfirmation paradigm to derive our line of argument and report on carers’ satisfaction with hospice dementia care (Oliver., Citation1980). The line of argument is a new storyline to explain what the findings from the included studies report on. It was derived from data interpretation and the expectancy-disconfirmation paradigm was used to explain the review findings, as we found that findings referred to participants ‘expectations and objective quality of the service.

Phase 7. We expressed the synthesis graphically for our findings to help reach wider audience with our data interpretation.

Results

Phases 1-3 (search strategy, study identification and quality appraisal)

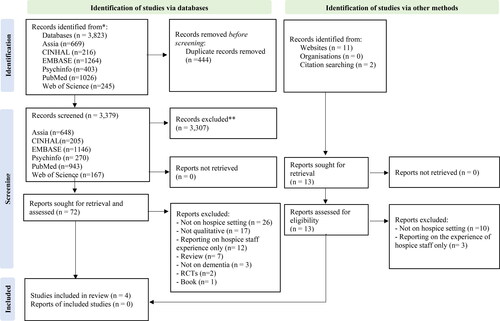

The systematic search yielded a total of 3,823 records (13 were retrieved from additional methods such as website search and cross referencing). Duplicate records removed 444 studies with 3,379 studies being screened by title and abstract. After this preliminary screening, 3,307 studies were excluded, and we screened the full text of 85 studies (13 of these were from additional sources) against the review’s inclusion/exclusion criteria ( for PRISMA flow diagram). We excluded 81 studies (see PRISMA for details of reasons) and included four studies for analysis.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (adapted from Page et al., Citation2021).

Studies characteristics

The four studies we included were published from 2009 to 2016 in peer-reviewed journals (Appendix B for study characteristics). Three studies were from the USA and one study from New Zealand. The most frequently reported themes across studies were around caregiving roles, experience of discharge from hospice, level and quality of support from health care professionals, grief, sleep deprivation and emotional handling.

Quality appraisal of included studies

All four studies were found to be of medium quality. All studies reported clear information on participants recruitment strategy, but none specified the sampling methodology used. We found it challenging to rate studies on ethics (Sanders et al., Citation2009, Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2012, Wladkowski et al. Citation2016, Citation2017) as this type of information was not clearly described in their methods, so they received a poor score on this domain.

Phase 4 (initial analysis phase)

We found the studies included in the review to have a common focus around expectations of carers with respect to hospice care and perceived level of support received by hospice staff, as reported from carers. We found initial themes on role expectations, role mastery, handling difficult care situations, lack or loss of support, fear of having a discharge form hospice, inadequate support, environmental support, poor satisfaction from hospice care, ambivalent care relationship, anticipated grief.

The analysis team discussed the relevance and accuracy of these themes and opted to use an expectancy-disconfirmation theory informed by the later work of Oliver (Citation1980), to effectively organise themes according to a psychological pattern based on having expectations of care and how these expectations would be confirmed or disconfirmed when receiving hospice care over time. This psychological theory entailed for example, that when certain expectations of care were not matched by either hospice staff (e.g. no effective support was provided for either the person with dementia or the carer) or the physical environment of the hospice setting (e.g. whether the environment was dementia friendly) there was a reduced level of satisfaction in carers for the care received. On the contrary, when carers’ expectation was matched by the staff and/or because of hospice setting being adequately dementia friendly, a more positive experience was reported from carers. Having good knowledge of end-of-life care and dementia as progressive condition, could help carers better handle the difficulty of end-of-life and palliative care.

Phase 5 (analysis phase with theme categorisations into constructs)

Two third-order constructs emerged from the meta-ethnography: expectations of care and barriers to quality of care. For each third order construct a number of associated theme categories were generated (). The synthesis is reported in .

Figure 2. Expressed synthesis: Expectancy-disconfirmation paradigm in carers’ satisfaction with hospice dementia care (informed by Oliver., 1980).

Line of argument: The Expectancy-disconfirmation paradigm entails that when carers’ expectations of care were not matched by either hospice staff or the physical care environment of the hospice setting (e.g., whether the environment was not dementia friendly) there was a reduced level of satisfaction in carers with respect to the care received. On the contrary, when carers’ expectation was matched by the staff and or because of hospice setting being adequately dementia friendly, a more positive experience was reported from carers. Having good knowledge of palliative and end-of-life dementia care early on during disease trajectory and of dementia being a progressive condition, could help carers better handle the difficulty and unpredictability of end-of-life and palliative care.

Table 1. Meta-ethnography: Third order constructs.

Our synthesis is based on psychological theory of expectancy-disconfirmation for user satisfaction of health care services. From the available cases, the psychological theory highlighted i) how expectancy is influenced by knowledge of the carer of end-of-life dementia care and dementia as progressive condition, ii) the perceived level of support the carers reports on hospice care for the person with dementia, iii) whether there is any buffering of expectations based on not feeling supported, constantly questioning the care and fear of having the person they care for, discharged by hospice.

Phases 6-7 (reporting of constructs, line of argument and expressed synthesis)

In this section we report on the two third order constructs that emerged from the analysis, alongside first order constructs to give examples of our interpretation.

1. Expectations of care

This theme refers to a series of expectations that carers may have with respect to the type of hospice care that should be in place for the person with dementia, but also the perceived level of support that could mould care expectations over time. This theme comprises two subthemes around i) the knowledge the carers own about end-of-life dementia care which may come from having cared for the person with dementia for a long time, and being aware of dementia as progressive condition; ii) the level of perceived support received during hospice care and after discharge.

1a. Knowledge of end-of-life dementia care

Expectations about health care may arise from previous life/care experiences and be diverse across individuals. There were, however, commonalities among the available cases, as the first subtheme highlights, being a carer for long time, seemed to help carers acquire knowledge about how to handle end-of-life situations in a more existential way:

‘There’s days when I have resentment and then there’s days when I’m absolutely overjoyed even to clean her diaper. I’m probably a real nut. There’s days when I go away and take my days off, and then I come back. I’m so glad to see her and give her a kiss and that she’s still alive that it’s not hard to clean her diaper.’ (Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2012, p. 1121).

‘He complains when he’s laying in bed, when he lays down at night. That’s when he complains about pain. So it’s Tylenol during the day. Morphine at night. Then we try various cocktails like temaze- pam and lorazepam [anxiety-reducing drugs]. “Pam” cocktails, we call them [laughing]. What we figured out is there’s not [a] magic cure. It’s just different everyday. So we just kind of go with the flow and see how he feels.’ (Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2012, p. 1120).

‘Let’s keep him comfortable and let nature take it’s course. It is time.’ (Sanders et al., Citation2009, p. 536).

‘It makes you feel better, too, knowing that you’re taking care of what you can the best that you can.’ (Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2012, p. 1120).

1b. Perceived level of support. The way carers perceive the level of support they receive for the person with dementia influences their experience of care. As reported by an author, knowing that the person is well supported by hospice staff is reassuring for carers:

‘It was the staff and their knowledge about [patient’s] condition and why she was the way she was and that they could put measures in place to assist her to be comfortable. (Bolton et al., Citation2016, p. 399).’

‘They always found something to put his mind at rest or try to make him more comfortable towards the end.’ (Bolton et al., Citation2016, p. 399).

‘She loved playing yahtzee … they got the game out for her and she was playing with it and she loved it … and the staff member knew that she liked it so they would take it out and they would play with her and, of course, she couldn’t play it—she had no idea how to play it. (Bolton et al., Citation2016, p. 399).

‘It was kind of…we knew it was coming. I mean, we thought after 3 months it was going to happen. We were surprised they kept her so long, we really were.’ (Wladkowski, Citation2016, p. 53).

2. Barriers to quality of care

This theme refers to a series of unmatched expectations that limit/reduce the quality of care experienced by the carer(s) involved in the hospice care for the person with dementia. This theme comprises three subthemes: i) one describing situations where the carer did not feel adequately supported by the hospice staff, ii) one reporting on the times when the carer, because of poor received support, felt questioning hospice quality of care, iii) the last subtheme described instead how the fear of having the person with dementia discharged from hospice, had an impact on the carers’ overall expectations of future care.

2a. Unmatched expectations

Not openly discussing about own fears of having the person with dementia move to hospice care, could lead to some feeling of guilt in carers who felt they had no other options at hand:

‘I took care of her for four years, but I couldn’t leave her alone. And she needed more care and I had work so I couldn’t do that anymore. So that part I feel guilty [about] because I couldn’t just quit my job and hire someone to help me take care of her with me.’ (Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2012, p. 1120).

‘Sometimes I feel embarrassed to talk to people about it, because I think that, I believe people are getting tired. They don’t want to hear what I’m saying. I don’t want people to feel like they have to.’ (Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2012, p. 1120).

‘I just want to cry all the time. I’m sure it’s because my momma’s sick, that’s why I feel like that. I don’t know. It’s weird. When I feel depressed, I just want to cry. I don’t want to live. Like I want to die.’ (Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2012, p. 1121).

‘This woman flared at me, and made an accusation of my not caring for my mother properly, which threw me totally for a loop because since Mom has been on hospice, we’ve worked with hospice… . She chooses to sleep, so I don’t disturb her until dinner time, but this woman took it as not caring properly to let my mother sleep.’ (Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2012, p. 1118).

‘In his mind, he thinks that if she doesn’t take all the morphine and stuff maybe she’ll get better because these drugs are making her worse… . But the bigger picture is why would you want her to suffer like this? Why keep her in agony? And his explanation when I asked him was, “Well, I want to save them for when she gets really bad. If she takes too many now then it won’t help her when it gets really bad.” Okay, so we’ll just make her lay in agony until you deem it’s really bad, and then we’ll give her the drugs?’ (Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2012, p. 1119).

‘I read the notes from [nurse]. Vitals are all OK. Smiling, walking better and eating better. Why is hospice here?’ (Sanders et al., Citation2009, p. 535).

‘I don’t think that things are as bad as they [hospice staff say]. I really think she will pull through this episode.’ (Sanders et al., Citation2009, p. 535).

‘I didn’t prepare, because we didn’t really know what was going to happen … then after that first year, and then they renewed her [my mother], and then they renewed her again. So, we kept thinking, “OK, well, she is …”—I mean, look at her! How can you think we don’t need help? How come you don’t think she’s for hospice? … she’s just a body lying there. Doesn’t talk, doesn’t change herself, doesn’t feed herself, doesn’t do anything for herself. She’s literally just lying in a hospital bed, does noth- ing. We need help, and, day-by-day—she could be gone tomorrow. We couldn’t imagine that they would let us go.’ (Wladkowski, Citation2016, p. 54).

‘If hospice can’t continue and I feel I don’t know how they will continue, I am not sure what I will do. I am terrified they are going to discharge her.’ (Sanders et al., Citation2009, p. 536).

‘It just changed—I had to be responsible for ordering all of the pills again, which was something that I hadn’t had to do before, because hospice sort of set that up and took care of reorders and all of that stuff … I was a little nervous … what am I going to do now that I’m not going to have this extra help?’ (Wladkowski, Citation2017, p. 144).

‘She [DCW] had been with my mother then for over a year. (pause) She loved her. She knew her very well—she felt pride in the work—in being with her… there was a way—they just had a relationship. And that was like the last time ever you would ever want to break that relationship. (Wladkowski, Citation2017, p. 145).

‘They didn’t tell us that they were taking equipment away… One of the [SNF] nurses said, ‘By the way, when hospice leaves, you know that they will take the air mattress and the chair.’ I was dismayed, shall we say, that hospice didn’t even say, ‘Oh, by the way, the equipment’s going when we go.’ It’s not terrific communication.’ (Wladkowski, Citation2017, p. 148).

‘Oh, I think it would have been more helpful if I had had—just basically, a list of what I could expect. Some kind of a very short, one page outline—these are the services your mother will be receiving from hospice, and this is the equipment she’s eligible for. Should she no longer be eligible for hospice, these are the things she will lose. Because that was the surprise, it was what she lost when hospice went away.’ (Wladkowski, Citation2017, p. 149).

‘Certainly I would have wanted a family meeting well in advance of when he was going to be discharged. I would have wanted the nursing home to spell out their transition strategy … I heard on a Thursday … and it happened on a Saturday. And I was really panicked and I thought this should not happen this way.’ (Wladkowski, Citation2017, p. 149).

‘I mean there are some patients there who are like 103, 105, somebody just had their 105th birthday, like oh my God, they told us that several of these patients had been on and off hospice for a couple of years and they said it’s kind of like a, what do you call it? Like a Catch-22 situation where hospice comes in and cares so much for them and pays so much attention and they wake up a little and they eat, somebody’s feeding them, somebody’s talking with them while they’re eating, and they start to do well so they come off hospice and then hospice leaves and then they decline and then ….’ (Wladkowski, Citation2016, p. 56).

‘I could see that she [mom] wasn’t deteriorating in the 6-month period the way she had last year. Yeah, it definitely—you say, “Geez, maybe I’m wrong. You know, maybe this is going to go on for a few more years.” And you know, that’s an odd position for you to be in. I don’t want my mother to pass away, but can I do this for 3 more years? Can I do this for 2 more years?’ (Wladkowski, Citation2016, p. 57).

Discussion

This review explored the experience of family carers of people with dementia of palliative and end-of-life care delivered in hospices. We were interested in the views of family carers about this type of service and what they report as barriers to care satisfaction. What we found is that carers were not always aware of what to expect from hospice care as they were not adequately briefed at the time of admission. Lack of awareness about care options, in some cases, led to increased fear in carers of having the person discharged from hospice, if symptoms improved or the person was receiving the care for longer than expected (usually more than 6 months). More positive care experiences were associated with increased perceived level of support from hospice staff and/or when the care environment was perceived to be compassionate and dementia friendly.

In line with findings from a recent survey reporting on key characteristics that community-based palliative and end-of-life care should focus on in dementia, our findings point to the importance of providing support for the carer (Butler et al., Citation2021). This support should be tailored to their needs of receiving prompt and effective information about their involvement in advance care planning, ensuring that awareness is promoted around continuity of care with strategic and effective education on what to expect and when to access hospice care during disease trajectory (Butler et al., Citation2021).

From the included studies, we found a common challenge among carers to have proper hospice care in place over time, not just during the last few weeks of life. The included studies, however, did not report on the experience of UK hospice care, and there may be differences across health care systems for end-of-life care (USA Vs UK Vs New Zealand). Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, Citation2018) points to the importance of establishing a palliative care approach that starts from diagnosis until the very end of life for people with dementia. In concert with recent evidence (WHO, Citation2018), in our review, carers quite strongly reported the need to have continuity of care without interruptions due to potentially avoidable discharges and extend this type of care beyond end-of-life, as bereavement support for family and informal carers. This would increase patients’ awareness of end-of-life care early on in the disease trajectory and potentially improve the care experience by having a well-supported programme in place rather than an episodic clinical input which may feel disjointed by patients and their families.

This review has some limitations. The use of the term hospice care across studies has made it difficult to clearly select only studies that reported on the experience of this type of care delivered in hospice settings. Most of the research evidence has focussed on hospice care delivered by clinical staff working in other health care settings (e.g. nursing homes, long-term care services) which we have not included in the review. There was the risk that UK-based studies were not included as mainly focussing on these type of community settings. This decision was based on the rationale that little has been done on care experiences delivered by staff working in hospices. There was, however, the risk of overlooking some evidence that did not clearly specify the settings, and thus may have been excluded. Therefore, we could only include four studies. Meta-ethnography requires a small number of studies to ensure that proper in-depth analysis is conducted (Soundy & Heneghan, Citation2022), nonetheless, our findings should be viewed with caution. Our findings signal a strong need for more qualitative research looking at the experience of hospice dementia care.

Implications for future research

This systematic review highlights current gaps in qualitative evidence around the experience of carers of palliative and end-of-life care delivered by hospice settings. We found it difficult to include specifically in-patient settings, as some studies reported focussing on hospice programmes with no further details on whether these were hospice in-patient admissions, hospice care programmes delivered in other community settings, or episodic in-patient admissions. This limited knowledge should be addressed in future research by including a more rigorous research methodology for qualitative designs, such as describing sampling, settings. The methodology would require more description around the theoretical framework underpinning the creation of coding schema and data interpretation, and a better description of participants’ recruitment and justification for data sampling. Extending recruitment to target the needs of underserved communities (e.g. ethnic groups, religious communities) may help understand the barriers affecting their experience of care. More work is needed for the inclusion of members from the patient and public involvement engagement (PPIE) group to give voice to those who have first-hand experience of end-of-life and palliative dementia care. Finally, research should make use of supplementary data (e.g. extended methods, anonymised datasets) in support of their study findings by sharing these alongside their manuscripts and or in publicly accessible repository. This would also ensure a clear reporting of results and that replicability of study findings is possible. Future research should specify which participants’ quotations come from an experience of home-based hospice care versus in-patient hospice care, as this information was not consistently reported across studies.

Conclusion

Our review found that to promote the delivery of good quality end-of-life and palliative dementia care in hospice, it is key to actively involve the family carers in the delivery of care and inquire about care expectations early on, before (or when) admission is made. This involves also re-examining care expectations with carers and having hospice staff openly communicating with them about possible barriers that could limit their experience of care later on, especially if discharge is needed. Increasing awareness around in-patient hospice care and what end-of-life care entails, may help carers and patients understand the several options being offered at the setting (i.e. pain management, counselling, bereavement support), potentially reducing the stress that a decision around admission may entail for families.

Ethical approval

The study received ethical approval from the Health Research Authority and the South Central - Oxford C Research Ethics Committee on 18.10.2022 (REC reference: 22/SC/0362; protocol number: NHS001995; IRAS project ID: 316546).

Disclaimer

This paper presents independent research funded [in part] by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaboration-Greater Manchester (NIHR200174) and the National Institute for Health and Care Research by a Senior Investigator Award to Prof Todd (NIHR200299) The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, or its partner organisations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10 .1002/alz.13016

- Booth, A., Noyes, J., Flemming, K., Moore, G., Tunçalp, Ö., & Shakibazadeh, E. (2019). Formulating questions to explore complex interventions within qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Global Health, 4(Suppl 1), e001107. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001107

- Bosco, A., Di Lorito, C., Dunlop, D., Briggs, M., Todd, C., Burns, A. (2022). End-of-life care in dementia: Systematic review and meta-ethnography. PROSPERO 2022 CRD42022348071. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022348071

- Bolton, L., Loveard, T., & Brander, P. (2016). Carer experiences of inpatient hospice care for people with dementia, delirium and related cognitive impairment. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 22(8), 396–403. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2016.22.8.396

- Browne, B., Kupeli, N., Moore, K. J., Sampson, E. L., & Davies, N. (2021). Defining end of life in dementia: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 35(10), 1733–1746. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211025457

- Butler, M., Gaugler, J. E., Talley, K. M. C., Abdi, H. I., Desai, P. J., Duval, S., Forte, M. L., Nelson, V. A., Ng, W., Ouellette, J. M., & Ratner, E. (2021). Care interventions for people living with dementia and their caregivers.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. Sage Publications.

- Etkind, S. N., Bone, A. E., Gomes, B., Lovell, N., Evans, C. J., Higginson, I. J., & Murtagh, F. E. M. (2017). How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Medicine, 15(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0860-2

- Europe Alzheimer. (2020). European Dementia Monitor 2020: Comparing and benchmarking national dementia strategies and policies. Rue Dicks.

- France, E. F., Cunningham, M., Ring, N., Uny, I., Duncan, E. A. S., Jepson, R. G., Maxwell, M., Roberts, R. J., Turley, R. L., Booth, A., Britten, N., Flemming, K., Gallagher, I., Garside, R., Hannes, K., Lewin, S., Noblit, G. W., Pope, C., Thomas, J., … Noyes, J. (2019). Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0600-0

- Gitlin, L. N., Maslow, K., & Khillan, R. (2018). National research summit on care, services, and supports for persons with dementia and their caregivers (pp. 2–40). Report to the National Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services.

- Lassell, R. K., Moreines, L. T., Luebke, M. R., Bhatti, K. S., Pain, K. J., Brody, A. A., & Luth, E. A. (2022). Hospice interventions for persons living with dementia, family members and clinicians: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(7), 2134–2145. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17802

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. (2021). Meeting the challenge of caring for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers: A way forward. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26026

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2021). Hospice facts and figures: Hospice care in America (2021st ed.). NHPCO.

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Sage.

- Noyes, J., Booth, A., Cargo, M., Flemming, K., Harden, A., Harris, J., Garside, R., Hannes, K., Pantoja, T., & Thomas, J. (2022). Chapter 21: Qualitative evidence. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, & V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- NVivo. (2012). Qualitative data analysis software. QSR International Pty Ltd.

- O’Connor, N., Fox, S., Kernohan, W. G., Drennan, J., Guerin, S., Murphy, A., & Timmons, S. (2022). A scoping review of the evidence for community-based dementia palliative care services and their related service activities. BMC Palliative Care, 21(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00922-7

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n71. http://www.prisma-statement.org/ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Sanders, S., Butcher, H. K., Swails, P., & Power, J. (2009). Portraits of caregivers of end-stage dementia patients receiving hospice care. Death Studies, 33(6), 521–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180902961161

- Schütz, A. (1962). Collected papers 1. Martinus Nijhoff.

- Soundy, A., & Heneghan, N. R. (2022). Meta-ethnography. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(1), 266–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1966822

- Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2003). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. UK Government Chief Social Researcher’s Office. http://www.uea.ac.uk/edu/phdhkedu/acadpapers/qualityframework.pdf.

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2018). Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. https://www.nice.org.uk/guida nce/ng97.

- Tuffrey-Wijne, I., Wicki, M., Heslop, P., McCarron, M., Todd, S., Oliver, D., de Veer, A., Ahlström, G., Schäper, S., Hynes, G., O’Farrell, J., Adler, J., Riese, F., & Curfs, L. (2016). Developing research priorities for palliative care of people with intellectual disabilities in Europe: A consultation process using nominal group technique. BMC Palliative Care, 15(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0108-5

- van der Steen, J. T., Radbruch, L., Hertogh, C. M. P. M., de Boer, M. E., Hughes, J. C., Larkin, P., Francke, A. L., Jünger, S., Gove, D., Firth, P., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., & Volicer, L. (2014). White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: A Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliative Medicine, 28(3), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313493685

- Wittenberg-Lyles, E., Demiris, G., Parker Oliver, D., Washington, K., Burt, S., & Shaunfield, S. (2012). Stress variances among informal hospice caregivers. Qualitative Health Research, 22(8), 1114–1125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312448543

- Wladkowski, S. P. (2016). Live discharge from hospice and the grief experience of dementia caregivers. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 12(1-2), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2016.1156600

- Wladkowski, S. P. (2017). Dementia caregivers and live discharge from hospice: What happens when hospice leaves? Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 60(2), 138–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2016.1272075

- World Health Organization. (2018). Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into primary health care: A WHO guide for planners, implement- ers and managers [internet].

- World Health Organization. (2021). Dementia. Retrieved December 21, 2021, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact- sheets/detail/dementia

- Wright, A. A., Zhang, B., Ray, A., Mack, J. W., Trice, E., Balboni, T., Mitchell, S. L., Jackson, V. A., Block, S. D., Maciejewski, P. K., & Prigerson, H. G. (2008). Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA, 300(14), 1665–1673. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.14.1665