Abstract

Objective

This study examined the dyadic association of self and informal caregiver proxy-reported met needs in persons living with dementia on the health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

Methods

A total of 237 persons with dementia and their caregivers were included from a previous observational study. HRQOL was assessed by the EuroQol-5D and the number of met needs by the Camberwell Assessment of Needs for the Elderly. The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model framework was used to analyze the effect of an individual’s self or proxy-reported met needs on their own HRQOL (actor effects), and an individual’s self or proxy-reported met needs on the other dyad member’s HRQOL (partner effects).

Results

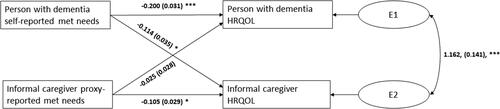

The number of self-reported met needs by persons living with dementia was negatively associated with their own HRQOL (actor effect b = −0.200, p < 0.001), and the HRQOL of informal caregivers (partner effect b = −0.114, p = 0.001). The number of proxy-reported met needs by informal caregivers was negatively associated with their own HRQOL (actor effect b = −0.105, p < 0.001) but not the person living with dementia’s HRQOL (-0.025, p = 0.375).

Conclusion

Study findings suggest that both self-reported and informal caregiver proxy-reported met needs in persons living with dementia should be considered in research and practice because they have different implications for each dyad members’ HRQOL.

Needs of persons living with dementia can increase over time due to progressive symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias combined with the mismatch between changing abilities and support from the social and physical environment (Miranda-Castillo et al., Citation2010). Unmet needs arise when care and support is not available or not adequately provided (Williams et al., Citation1997). Experiencing unmet needs in persons living with dementia is associated with behavioral problems, depression, and low quality of life (Black et al., Citation2013; Miranda-Castillo et al., Citation2010). Negative effects relating to unmet needs in persons living with dementia also occur for informal caregivers. Previous research has found that self-reported unmet needs of persons living with dementia are associated with negative outcomes on their own health-related quality of life (HRQOL), defined as an individuals’ perception on their mental and physical health (Monin et al., Citation2020). Also, unmet needs of persons living with dementia were associated with poorer HRQOL of their informal caregivers. Informal caregiver proxy reports on the unmet needs of persons living with dementia where not associated with the HRQOL of informal caregivers, nor that of the persons with dementia (Monin et al., Citation2020)

Met needs indicate that support is sufficiently provided through formal or informal care based on the subjective wishes and preferences of persons living with dementia and informal caregivers (Williams et al., Citation1997). It is important to examine both unmet and met needs because this information allows practitioners to provide support for needs not being addressed while also understanding the scope of needs being addressed. Furthermore, persons living with dementia and informal caregivers may have different perspectives on needs (Carvacho et al., Citation2021). For example, persons living with dementia report fewer met needs compared to proxy reports by informal caregivers (Black et al., Citation2013; Kerpershoek et al., Citation2018; Mazurek et al., Citation2019; van der Roest et al., Citation2009). This may be because informal caregivers are providing support for needs that care recipients are unaware of or perceive that they do not need (van der Roest et al., Citation2007).

Because of the different perspectives on needs, implications of HRQOL for each member of a dementia care dyad may be different. Although most research focuses on unmet needs, there is some evidence suggesting that persons living with dementia that have lower HRQOL report a higher number of met needs (Mazurek et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, dependence on caregiving or assistance with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of persons living with dementia has been proposed as a marker for worse self-reported HRQOL (Jones et al., Citation2015). Especially receiving instrumental support, more so than emotional support, is suggested to have a negative effect on the wellbeing of a care recipient, because it emphasizes their inability to accomplish daily tasks on their own (Reinhardt et al., Citation2006). For the informal caregiver, met needs may be a surrogate measure of caregiving burden, the amount of work performed to support the person living with dementia. Dependency level of the person with dementia, caregiver duration and informal caregiver hours are associated with caregiver burden (Kim et al., Citation2012). Informal caregivers largely carry the responsibility of ensuring the needs of persons living with dementia are met by providing assistance with daily living activities and supporting the care recipients emotional and social well-being (Cheng, Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2012; Lindt et al., Citation2020). Hence, the HRQOL of informal caregivers may be disproportionally affected by the met needs of the person they care for (Riedijk et al., Citation2006; Thomas et al., Citation2006).

Because perceptions of met needs from persons living with dementia and informal caregivers are likely to have intrapersonal and interpersonal associations with HRQOL, a dyadic analysis approach was used in this study. Specifically, this study used the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) which allows for simultaneously estimating the effect of an individual’s own predictor on their own outcome (actor effects), and an individual’s predictor on the other individual’s outcome (partner effects) (Cook & Kenny, Citation2005), to examine the association of self and informal caregiver proxy- reported met needs of people living with dementia on both dyad member’s HRQOL. Study hypotheses are the following:

1a and b: More self-reported met needs in persons living with dementia will be associated with worse HRQOL in persons with dementia, and more proxy-reported met needs by informal caregivers will be associated with worse HRQOL in informal caregivers (actor effects).

2a and b: More self-reported met needs in persons living with dementia will be associated with worse HRQOL in informal caregivers, and more proxy-reported met needs by informal caregivers will be associated with worse HRQOL in persons living with dementia (partner effects).

3: The number of self-reported met needs by the person living with dementia will be lower than the proxy-reported met needs by the informal caregivers.

Methods

Design and sample

This study analyzed baseline data from the COMPAS study, a two-year prospective, observational, cohort study among person living with dementia and their informal caregiver (Dutch Trials Registry; NTR3268) (MacNeil Vroomen et al., Citation2012). Data from 521 community-dwelling dyads were collected via interviews and questionnaires. Persons living with dementia were eligible for this study if they lived at home, had an established/formal diagnosis of dementia, were not terminally ill, were not anticipated to be admitted to a long-term care facility within 6 months, and had an informal caregiver. Informal caregivers were eligible if they were the primary informal caregiver responsible for caring for the person living with dementia, had sufficient language proficiency, and were not severely ill. A total of 237 dyads were included in this study as they provided data on self- and proxy-reported met needs and the HRQOL of both dyad members, which was required for the APIM analysis.

Study variables

HRQOL assessed by the EuroQol- 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) was the primary outcome of this study. The EQ-5D was self-administered by the person living with dementia as well as the informal caregiver. Using the valuation set Dutch EQ-5D Tariff (Lamers et al., Citation2005), a single utility score for each individual was created from the 243 (35) possible combinations of responses: no problems, some problems, or severe problems; on the five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression. The utility score reflected the relative desirability of health states where a score of 10 indicates full health, 0 indicates death, and negative scores indicate a health state worse than death. The EQ-5D is recommended for a variety of populations including persons living with dementia (Hussain et al., Citation2022; Keetharuth et al., Citation2022), and has good construct validity, criterion validity and test-retest reliability (Hussain et al., Citation2022; Keetharuth et al., Citation2022).

Met needs in persons living with dementia assessed by the Camberwell Assessment of Needs for the Elderly (CANE) was the focal predictor of this study. An independent assessor scored health and social needs across the 24 domains of the CANE together with the person living with dementia (self-reported) and the informal caregiver (proxy-reported) during a one-on-one conversation. Scoring possibilities were no need, met need, or unmet need. Sum scores of the met needs were calculated, with a maximum of 24 met needs. The Dutch version of the CANE demonstrates good construct validity, criterion validity and test-retest reliability with a κ of 0.84 for the total number of needs (van der Roest et al., Citation2008).

Covariates were age and sex of persons living with dementia and informal caregivers; education, Mini Mental State Examination (Folstein et al., Citation1975), Neuropsychiatric Inventory (Cummings et al., Citation1994), and multimorbidity of persons with dementia; and General Health Questionnaire-12 (Goldberg & Hillier, Citation1979), case management utilization, Neuropsychiatric Inventory of Caregiver Distress (Cummings et al., Citation1994), Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire (Vernooij-Dassen et al., Citation1999), and relationship to person living with dementia of informal caregivers.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe study participant characteristics. Bivariate analyses were performed to evaluate correlations among study variables. The main analysis consisted of an APIM, a dyadic approach designed to model dynamics within interdependent pairs of individuals (Cook & Kenny, Citation2005). APIM accounts for interdependence by correlating the independent variables and the error terms of the dependent variables from both dyad members. An APIM with structural equation modelling and maximum likelihood for estimation was used to analyze actor and partner effects (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017). The actor effects denote the extent to which either the number of self or proxy-reported met needs is associated with the dyads member’s own HRQOL. The partner effects denote the extent to which either the number of self-reported or proxy-reported met needs is associated with the other member of the dyad’s HRQOL. Only significant covariates were retained in the final model. All analysis were conducted in MPLUS version 8.8 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017). Significance was set at two tailed p < 0.05.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Age and sex were statistically different between person living with dementia and informal caregivers (). Persons living with dementia self-reported on average a significant lower number of met needs compared to the caregiver proxy. Persons living with dementia reported on average significant higher levels of HRQOL compared to informal caregivers. presents the correlation among the outcomes and focal predictors of this study.

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants (n = 237).

Table 2. Correlation matrix among study outcomes and focal predictors (n = 237).

APIM self and proxy-reported met needs on HRQOL

depicts that the number of self-reported met needs of persons living with dementia were significantly negatively associated with their own HRQOL (actor effect b = −0.200, p < 0.001), and with the HRQOL of informal caregivers (partner effect b = −0.114, p = 0.001). Informal caregiver proxy reports on the met needs of persons living with dementia were negatively associated with the HRQOL of informal caregivers (actor effect b = −0.105, p < 0.001). Informal caregiver proxy reports were not significantly associated with persons with dementia’s HRQOL (partner effect). There was significant covariance between the outcome residuals from both dyad members (b = 1.162, p < 0.001). None of the covariates were significant.

Discussion

This study provides evidence that self-reported met needs of people with dementia are negatively associated with their own HRQOL (actor effect), as well as the HRQOL of informal caregivers (partner effect). In addition, proxy-reported met needs of people with dementia by informal caregivers are negatively associated with their own HRQOL (actor effect). There was no significant partner effect for proxy-reported met needs by the informal caregiver on the HRQOL of persons living with dementia.

These findings are consistent with our previous findings which showed that greater self-reported unmet needs predicted actor and partner effects of lower HRQOL in dementia care dyads (Monin et al., Citation2020). This study extends our past work by showing that the views of persons with dementia of their own needs are important to both themselves and their informal caregivers, irrespective of being met or unmet needs. In line with this idea, literature suggests that there is a relation between the number of met and unmet needs in persons living with dementia. A recent review showed that when more unmet needs are reported, the number of met needs is higher as well (Carvacho et al., Citation2021). Also, consistent with our findings, literature showed that on average more met needs than unmet needs are reported (Carvacho et al., Citation2021). The balance between met and unmet needs might be an indicator of the complexity of caregiving situations. It shows practitioners which type of support to provide for the needs that are not addressed, in addition to illustrating the extent of care being provided by formal and informal care. There is always the possibility that the many met needs could go unmet in the future.

Further, persons with dementia reported less met needs compared to the informal caregiver proxy. This is in line with other literature that suggest that either the person with dementia underreports their own needs, or the informal caregiver is overestimating them (Carvacho et al., Citation2021; Curnow et al., Citation2021; O’Shea et al., Citation2020; van der Roest et al., Citation2009). This disagreement might be driven by the ‘disability paradox’, were people with disabilities report a rather good HRQOL while proxy reporters view this person as in a bad health (Römhild et al., Citation2018). The overestimation of informal caregivers might be attributed to caregiver burden, expecting the person with dementia to be overburdened as well (Gräske et al., Citation2014). Nevertheless, the perspective of the person with dementia seems to be more influential, as in this study it was a determinant for their own and the informal caregivers’ HRQOL. Even more so, this study and our previous work showed that the number of proxy-reported met and unmet needs by informal caregivers were not associated with the HRQOL of persons living with dementia (Monin et al., Citation2020). These discrepancies show the difference in implications on both individuals HRQOL and underline the risk of solely relying on proxy reports.

In contrast to our previous work that did not find a significant effect of informal caregiver proxy-reported unmet needs on their own HRQOL (Monin et al., Citation2020), this study found that a higher number of proxy-reported met needs by informal caregivers were associated with lower HRQOL in informal caregivers. Literature describing the relation of proxy-reported met needs by informal caregivers and their well-being is scarce, while met needs might be a surrogate for caregiver burden. Although behavioural problems are often suggested to be the primary predictor for caregiver burden (van der Lee et al., Citation2014), a recent systematic review showed that related indicators such as the dependency level of the person living with dementia and the duration of caregiving are also proposed as stressors for caregiver burden (Lindt et al., Citation2020). In addition, the amount of caregiver hours is mentioned as a possible stressor, especially for informal caregivers with a low social network (Kim et al., Citation2012; Xu et al., Citation2021). Informal caregivers provide a substantial proportion of care that turns unmet needs into met needs. The added strain to attain a larger variety of needs of the person living with dementia, may result in worse HRQOL in informal caregivers. This effect might not be detected by only focussing on unmet needs, which is the tendency in current dementia caregiving research (Carvacho et al., Citation2021).

This study has several limitations. First, it was cross-sectional. Because people with dementia with severe cognitive impairment may underreport their needs and overestimate their HRQOL (Griffiths et al., Citation2020), discrepancies in reports and associations in turn may change over time. The longitudinal data of the COMPAS study contained missing data that could potentially bias the results. Second, an extra perspective on the needs in the person with dementia as a proxy (e.g. health care professional, other caregiver, or researcher) other than the informal caregiver might provide different findings. Third, there was no data available on caregiver burden, which limits the description of our study population.

Overall, the results of this study have important implications for research and care practice. The study findings imply that research should include the views on met and unmet needs in persons with dementia, when examining dementia care dyads’ HRQOL. Discrepancies in reporting of needs between persons living with dementia and informal caregivers further emphasize the necessity for care professionals to use dyadic reports of needs and well-being to fully understand how to support dementia care dyads.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Black, B. S., Johnston, D., Rabins, P. V., Morrison, A., Lyketsos, C., & Samus, Q. M. (2013). Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: Findings from the maximizing independence at home study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(12), 2087–2095. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12549

- Carvacho, R., Carrasco, M., Lorca, M. B. F., & Miranda-Castillo, C. (2021). Met and unmet needs of dependent older people according to the Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE): A scoping review. Revista Espanola de Geriatria y Gerontologia, 56(4), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2021.02.004

- Cheng, S. T. (2017). Dementia Caregiver Burden: A Research Update and Critical Analysis. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(9), 64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2

- Cook, W. L., & Kenny, D. A. (2005). The actor-partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000405

- Cummings, J. L., Mega, M., Gray, K., Rosenberg-Thompson, S., Carusi, D. A., & Gornbein, J. (1994). The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology, 44(12), 2308–2314. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308

- Curnow, E., Rush, R., Maciver, D., Gorska, S., & Forsyth, K. (2021). Exploring the needs of people with dementia living at home reported by people with dementia and informal caregivers: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 25(3), 397–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1695741

- Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

- Goldberg, D. P., & Hillier, V. F. (1979). A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychological Medicine, 9(1), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700021644

- Gräske, J., Meyer, S., & Wolf-Ostermann, K. (2014). Quality of life ratings in dementia care? a cross-sectional study to identify factors associated with proxy-ratings. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12, 177. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-014-0177-1

- Griffiths, A. W., Smith, S. J., Martin, A., Meads, D., Kelley, R., & Surr, C. A. (2020). Exploring self-report and proxy-report quality-of-life measures for people living with dementia in care homes. Quality of Life Research, 29(2), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02333-3

- Hussain, H., Keetharuth, A., Rowen, D., & Wailoo, A. (2022). Convergent validity of EQ-5D with core outcomes in dementia: A systematic review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 20(1), 152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-022-02062-1

- Jones, R. W., Romeo, R., Trigg, R., Knapp, M., Sato, A., King, D., Niecko, T., & Lacey, L; DADE Investigator Group. (2015). Dependence in Alzheimer’s disease and service use costs, quality of life, and caregiver burden: The DADE study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 11(3), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.001

- Keetharuth, A. D., Hussain, H., Rowen, D., & Wailoo, A. (2022). Assessing the psychometric performance of EQ-5D-5L in dementia: A systematic review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 20(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-022-02036-3

- Kerpershoek, L., de Vugt, M., Wolfs, C., Woods, B., Jelley, H., Orrell, M., Stephan, A., Bieber, A., Meyer, G., Selbaek, G., Handels, R., Wimo, A., Hopper, L., Irving, K., Marques, M., Gonçalves-Pereira, M., Portolani, E., Zanetti, O., & Verhey, F; Actifcare Consortium. (2018). Needs and quality of life of people with middle-stage dementia and their family carers from the European Actifcare study. When informal care alone may not suffice. Aging & Mental Health, 22(7), 897–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1390732

- Kim, H., Chang, M., Rose, K., & Kim, S. (2012). Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(4), 846–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05787.x

- Lamers, L. M., Stalmeier, P. F., McDonnell, J., Krabbe, P. F., & van Busschbach, J. J. (2005). [Measuring the quality of life in economic evaluations: The Dutch EQ-5D tariff]. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde, 149(28), 1574–1578.

- Lindt, N., van Berkel, J., & Mulder, B. C. (2020). Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: A systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 304. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01708-3

- MacNeil Vroomen, J., Van Mierlo, L. D., van de Ven, P. M., Bosmans, J. E., van den Dungen, P., Meiland, F. J. M., Dröes, R.-M., Moll van Charante, E. P., van der Horst, H. E., de Rooij, S. E., & van Hout, H. P. J. (2012). Comparing Dutch case management care models for people with dementia and their caregivers: The design of the COMPAS study. BMC Health Services Research, 12, 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-132

- Mazurek, J., Szcześniak, D., Urbańska, K., Dröes, R.-M., & Rymaszewska, J. (2019). Met and unmet care needs of older people with dementia living at home: Personal and informal carers’ perspectives. Dementia (London, England), 18(6), 1963–1975. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217733233

- Miranda-Castillo, C., Woods, B., Galboda, K., Oomman, S., Olojugba, C., & Orrell, M. (2010). Unmet needs, quality of life and support networks of people with dementia living at home. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-132

- Monin, J. K., Jorgensen, T. D., & MacNeil Vroomen, J. L. (2020). Self-Reports and Caregivers’ Proxy Reports of Unmet Needs of Persons With Dementia: Implications for Both Partners’ Health-Related Quality of Life. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(3), 363–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2019.10.006

- Muthén, L. K., Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus V 8.8 User guide. https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf

- O’Shea, E., Hopper, L., Marques, M., Gonçalves-Pereira, M., Woods, B., Jelley, H., Verhey, F., Kerpershoek, L., Wolfs, C., de Vugt, M., Stephan, A., Bieber, A., Meyer, G., Wimo, A., Michelet, M., Selbaek, G., Portolani, E., Zanetti, O., … Irving, K; Consortium, A. (2020). A comparison of self and proxy quality of life ratings for people with dementia and their carers: A European prospective cohort study. Aging & Mental Health, 24(1), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1517727

- Reinhardt, J. P., Boerner, K., & Horowitz, A. (2006). Good to have but not to use: Differential impact of perceived and received support on well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23(1), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407506060182

- Riedijk, S. R., De Vugt, M. E., Duivenvoorden, H. J., Niermeijer, M. F., Van Swieten, J. C., Verhey, F. R., & Tibben, A. (2006). Caregiver burden, health-related quality of life and coping in dementia caregivers: A comparison of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 22(5-6), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1159/000095750

- Römhild, J., Fleischer, S., Meyer, G., Stephan, A., Zwakhalen, S., Leino-Kilpi, H., Zabalegui, A., Saks, K., Soto-Martin, M., Sutcliffe, C., Rahm Hallberg, I., … Berg, A, Consortium, R. (2018). Inter-rater agreement of the Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) self-rating and proxy rating scale: Secondary analysis of RightTimePlaceCare data. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0959-y

- Thomas, P., Lalloué, F., Preux, P.-M., Hazif-Thomas, C., Pariel, S., Inscale, R., Belmin, J., & Clément, J.-P. (2006). Dementia patients caregivers quality of life: The PIXEL study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1422

- van der Lee, J., Bakker, T. J. E. M., Duivenvoorden, H. J., & Droes, R. M. (2014). Multivariate models of subjective caregiver burden in dementia: A systematic review. Ageing Research Reviews, 15, 76–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2014.03.003

- van der Roest, H. G., Meiland, F. J. M., Comijs, H. C., Derksen, E., Jansen, A. P. D., van Hout, H. P. J., Jonker, C., & Dröes, R.-M. (2009). What do community-dwelling people with dementia need? A survey of those who are known to care and welfare services. International Psychogeriatrics, 21(5), 949–965. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610209990147

- van der Roest, H. G., Meiland, F. J. M., Maroccini, R., Comijs, H. C., Jonker, C., & Droes, R. M. (2007). Subjective needs of people with dementia: A review of the literature. International Psychogeriatrics, 19(3), 559–592. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610206004716

- van der Roest, H. G., Meiland, F. J., van Hout, H. P., Jonker, C., & Droes, R. M. (2008). Validity and reliability of the Dutch version of the Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly in community-dwelling people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 20(6), 1273–1290. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610208007400

- Vernooij-Dassen, M. J., Felling, A. J., Brummelkamp, E., Dauzenberg, M. G., van den Bos, G. A., & Grol, R. (1999). Assessment of caregiver’s competence in dealing with the burden of caregiving for a dementia patient: A Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SSCQ) suitable for clinical practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47(2), 256–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb04588.x

- Williams, J., Lyons, B., & Rowland, D. (1997). Unmet long-term care needs of elderly people in the community: A review of the literature. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 16(1-2), 93–119. https://doi.org/10.1300/J027v16n01_07

- Xu, L., Liu, Y. W., He, H., Fields, N. L., Ivey, D. L., & Kan, C. (2021). Caregiving intensity and caregiver burden among caregivers of people with dementia: The moderating roles of social support. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 94, 104334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104334