Abstract

Objectives

This scoping review seeks to identify what community-based support is used by older sexually and gender diverse (SGD) people, that aims to improve mental health/wellbeing.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted using the Arksey and O’Malley framework. APA PsycInfo, Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed, and Scopus were searched. Key information was extracted and entered into a structured coding sheet before being summarized.

Results

Seventeen studies were included (41% observational qualitative and 35% observational quantitative). The most commonly used community-based support was lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) social groups. A range of practices were reported in five studies, including in SGD affirming religious congregations and mind-body practices. Two studies reported the use of formal programmes, with one based on a group initiative. Positive outcomes included feeling connected, improved social support and mental health, and coping with illness. Five studies reported null or negative findings, including a lack of acceptance. Most studies used categories for sex and gender inaccurately, and lacked detail when describing community-based support.

Conclusion

The use of community-based support by older SGD people is underexplored. More interventions designed for and by this community are needed, along with experimental research to draw conclusions on effectiveness to improve mental health or wellbeing.

Introduction

Psychological distress and mental health issues remain major health concerns in the aging population. Those on an aging trajectory (50 years and older) are at higher risk for social isolation, loneliness, and reduced physical health, adversely impacting mental health (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, Citation2014; Golden et al. Citation2009; Langhammer et al. Citation2018; Luanaigh & Lawlor, Citation2008). As the global population ages, it also becomes increasingly diverse due to more people identifying as sexually and gender diverse (SGD). Approximately 2.4 million people over the age of 50 identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) in the United States, which is predicted to double by 2030 (Choi & Meyer, Citation2016). Despite this, the mental health needs of older, sexually and gender diverse people have only recently become of research interest.

Most older adults living in western democratic regions of the world, were born into an era of pathologization or criminalization of same-sex behaviors and identities. Socio-political and legislative changes have brought about greater equality for those who identify as SGD, however significant mental health and wellbeing discrepancies persist (Kneale et al. Citation2021). Suicidal ideation has been found to increase with age in bisexual women (Colledge et al. Citation2015), and this may be the effect of intersectional discrimination based on gender, age, and sexual orientation. Sexually diverse older people are at higher risk for a range of clinical concerns, including anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, et al. Citation2013; Su et al. Citation2016; Yarns et al. Citation2016). Older SGD people are more likely to report lacking companionship and experiencing social isolation and loneliness, further exacerbating mental health problems (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. Citation2011; Wilkens, Citation2015).

In the literature on aging there is extensive focus on interventions and services aimed at improving mental wellbeing in community or rest-home dwelling older adults. Promising interventions have employed reminiscence, laughter therapy, and mechanisms from positive psychology and mindfulness, such as savoring, and gratitude to improve resilience and psychological wellbeing (Friedman et al. Citation2017; Killen & Macaskill, Citation2015; Proyer et al. Citation2014; Quan et al. Citation2020; Smith & Hanni, Citation2019; Treichler et al. Citation2020; Viguer et al. Citation2017). Recent creative community-based interventions include singing to augment positive affect and a ‘social prescription’ to explore museums (Galinha et al. Citation2023; Thomson et al. Citation2018). Further, psychosocial interventions are frequently used to reduce loneliness by improving social support, increasing social interactions, and augmenting social skills (Masi et al. Citation2011).

Although SGD older people are at higher risk of experiencing psychological distress, research highlights barriers to seeking support or engaging in community-based activities. These include a non-inclusive environment, lack of SGD support groups, perceived lack of adequately trained mental health practitioners, and fear of judgment (Dunkle, Citation2018; Jenkins Morales et al. Citation2014; Rees et al. Citation2021). A call for researchers to consider innovative and empowering ways to improve the quality of and SGD adult engagement with existing services (Cummings et al. Citation2021) has been made. This includes developing a focus on enhancing mental wellbeing (Rees et al. Citation2021). It is therefore important to identify what community-based support is used by older SGD people that aims to improve mental health or wellbeing.

Methods

A systematic scoping review was conducted to determine the scope of literature in this area, as no scholarly overview has been undertaken. A scoping literature review is used to provide an overview of a body of literature, to identify the volume and types of evidence available on a topic, identify gaps in the research and map the findings (Munn et al. Citation2018). It is useful in an under-researched field and can be used to identify questions for future research that can be addressed by a full systematic review (Munn et al. Citation2018). This review was conducted by following the Arksey and O’Malley five step process for scoping reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). The steps are 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) selecting studies, 4) charting the data and 5) collating, summarizing, and reporting results. The review is reported in line with the extended Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al. Citation2018).

Identifying the research question

An initial search of the literature demonstrated that older SGD people are significantly more impacted by adverse mental health and wellbeing. However, no scholarly review has been conducted to identify what support is used by this population. This scoping review seeks to identify what community-based support is used by SGD older people, that aims to improve mental health or wellbeing.

Identifying relevant studies

The following databases were systematically searched in September 2021 to identify relevant articles: APA PsycInfo, Embase, MEDLINE (Ovid), PubMed, and Scopus. Initial search terms were determined with input from all authors (see ). The first author developed the final search strategy with assistance from an experienced research librarian. The search strategy was adapted for use across the databases (see supplementary file). Reference lists from the final selection of articles were snowballed to identify other possible studies that may not have been indexed in databases.

Table 1. Concept table of key search terms and phrases.

Selecting studies

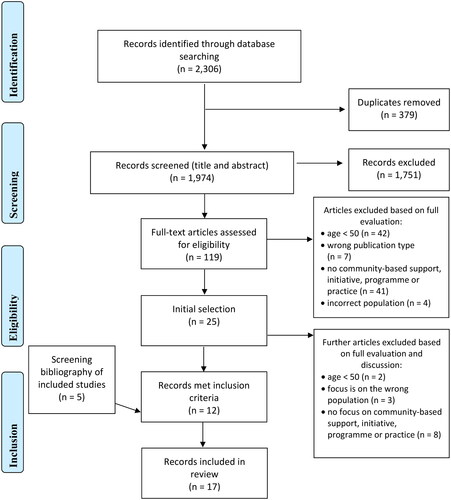

Search results were exported into Endnote X9 to collate the articles and remove duplicates. Articles were then exported to the software Rayyan, where the first author independently assessed each article by screening study titles and abstracts, to determine whether articles met the inclusion criteria (Ouzzani et al. Citation2016). Further assessments were conducted by reviewing the full texts of the articles until an initial selection was made. All authors independently reviewed the initial selection, first by screening the titles and abstracts and then the full text. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion until full consensus was obtained. See for a PRISMA-ScR flowchart displaying the selection process.

To be eligible for inclusion, studies reported community-based support used by older (50 years of age or older) SGD people, that aimed to improve mental health or wellbeing. ‘Community-based support’ in this review refers to support available to community-residing older people, and includes wellbeing programmes, interventions, initiatives, and practices. This also includes educational resources, counseling, and opportunities for community engagement through volunteering (Siegler et al. Citation2015). For the purpose of this review, ‘sexually and gender diverse’ included (but was not limited to) people who identified as lesbian, gay, queer, non-binary, bisexual, pansexual, plurisexual, transgender and asexual. To be eligible, studies were published in English between 2000 and 2021 and employed any research design (e.g. experimental, observational, or qualitative research). Participants were community-residing but were considered eligible if they had a health condition (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Any studies that did not meet these criteria, such as those not reporting community-based support that aims to improve mental health or wellbeing were excluded. See Table 2 (supplemental file) for full inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Charting the data

Key information, such as that pertaining to the study’s characteristics (e.g. title, authors, location, aims and publication date) were extracted to a structured Excel sheet. Detail about the population of interest was extracted, such as age group, gender, sex and data on nomenclature for the target population (e.g. terms/language employed to describe the participants in relation to sexuality and gender). Data on the type of community-based support were also extracted, including the type, length, and format. When reported, outcomes relating to mental wellbeing (such as resilience), mental health (e.g. emotional, psychological, or social wellbeing) or experiences and perceptions were extracted. No formal quality assessment was undertaken as this is not required for a scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005).

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

A synthesis was undertaken with studies categorized according to a type of intervention/programme/initiative/practice. Commonalities and differences between studies were highlighted in relation to delivery, content, outcome measures, and effectiveness. This process helped to identify gaps in the literature to help inform future research.

Results

In this review, 2306 studies were identified and imported into Rayyan for initial screening. After removing duplicates, studies were screened based on their abstracts and titles, leading to the exclusion of 1751 studies. Following this process, 119 full texts were screened for eligibility to make an initial selection of 25 studies. All authors reviewed the full texts from the initial selection, leading to the further exclusion of 13 studies. Upon discussion, studies were excluded due to not meeting age criteria (e.g. some participants were aged below 50 years) (n = 2), reporting of results was focused on the wrong population (n = 3) (i.e. heterosexual participants), or due to not being focused on a community-based support (n = 8). A total of seventeen studies were included in this review. See the PRISMA-ScR flowchart in for more information on the identification and screening process.

Characteristics of the included studies

Of the included studies, seven were observational qualitative (Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020; Misgav, Citation2016; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002; Traies, Citation2015; Valenti et al. Citation2021), of which one consisted of field notes and anecdotal evidence (Hughes et al. Citation2014). Seven studies were quantitative, with six being observational (Anderson et al. Citation2021; Averett et al. Citation2011; Escher et al. Citation2019; Lyons, Citation2016; Lyons et al. Citation2021; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019), and one using a randomized controlled trial design (Heckman et al. Citation2014). Three reported using mixed methods, such as a cross-sectional survey and qualitative analysis of open-ended questions (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Sharek et al. Citation2015).

Studies were published between 2002 (Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002) and 2021 (Anderson et al. Citation2021; Lyons et al. Citation2021; Valenti et al. Citation2021). Eleven studies were conducted in the United States of America (Anderson et al. Citation2021; Averett et al. Citation2011; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Escher et al. Citation2019; Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020; Heckman et al. Citation2014; Hughes et al. Citation2014; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002; Valenti et al. Citation2021). One study was conducted in the United Kingdom (Traies, Citation2015), two in Israel (Misgav, Citation2016; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019), one in Ireland (Sharek et al. Citation2015), and two in Australia (Lyons, Citation2016; Lyons et al. Citation2021). Across the 16 studies that reported sample sizes, the samples varied from 8 (Misgav, Citation2016) to 13,424 participants (Anderson et al. Citation2021), with a mean of 1,039 and a total of 16,620 participants. Participants were aged between 50 and 92 years. Ethnic and racial identity was reported in 11 studies. Participation was primarily by white/Caucasian individuals, and ranged from 23% (83/361) to 100% (16/16). Only one study had 50% or more of participants identifying as non-white (i.e. African American) (Heckman et al. Citation2014). Further characteristics of the included studies are reported in Table 3 (see supplemental file).

Inaccuracies and inconsistencies were identified in relation to reporting on sex and gender of participants in most studies. Statistics for the samples are reported in Table 3 (see supplemental file). Issues included use of terms relating to descriptions of sexFootnote1 (including using terms male, female, or intersex) when reporting on gender or gender identity (Anderson et al. Citation2021; Averett et al. Citation2011; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Escher et al. Citation2019; Lyons et al. Citation2021; Sharek et al. Citation2015; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019; Valenti et al. Citation2021). Three studies used incorrect terminology for describing gender diverse people including transgender male/transgender female (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Sharek et al. Citation2015) and in one study transgender was separated to a discrete category rather than included as one of the options under the category of gender (Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019). One study did not report data on gender or sex (Hughes et al. Citation2014).

In terms of sexual diversity, studies included a mixture of participants. Five studies included those who were identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other (Averett et al. Citation2011; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Sharek et al. Citation2015; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019), and three studies included participants who were lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB) only (Anderson et al. Citation2021; Escher et al. Citation2019; Valenti et al. Citation2021). Two studies involved lesbian and gay (Hughes et al. Citation2014; Lyons et al. Citation2021) or lesbian only participants (Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Traies, Citation2015). Further single studies involved participants identified as gay and bisexual (Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002), gay only (Lyons, Citation2016), and men who have sex with men and straight (Heckman et al. Citation2014). One study did not report on sexual diversity (Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020) and one reported participants as gay only, but had missing data from the sample (Misgav, Citation2016).

Community-based support

The use of general SGD social groups or meetings was reported in six studies, including groups such as the ‘Older Lesbians’ Network’ and ‘Golden Rainbow’ (Averett et al. Citation2011; Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020; Misgav, Citation2016; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019; Traies, Citation2015). Two studies reported the use of lesbian and gay support groups for grief and bereavement following the loss of a spouse or partner (Hughes et al. Citation2014; Valenti et al. Citation2021). A single study mentioned self-help groups and HIV support groups (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014).

The use of mental health providers in the community to improve wellbeing was mentioned in four studies (Averett et al. Citation2011; Lyons, Citation2016; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Sharek et al. Citation2015). These included therapists (Averett et al. Citation2011; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014), counselors (Lyons, Citation2016), and psychological and counseling services (Sharek et al. Citation2015). In one study, lesbian therapists were accessed for support with alcoholism, alongside residential, inpatient and outpatient treatments (Rowan & Butler, Citation2014). Two studies mentioned the use of transgender affirming supportive services (Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020) or mental health supportive services (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014), but it was unclear who delivered these services. Other community-based support included gay organizations or centres (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Lyons, Citation2016), such as the Gay Community Centre that also offers gay theatre (gay-triatrics) (Misgav, Citation2016).

Engaging in religious/spiritual practices or communities was most frequently cited. Religious engagement reported in one study included with fundamentalist Christian and mainstream religious denominations (Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002) and in two studies, with Catholicism, Protestant affiliations (e.g. United Church of Christ), Baptist, and non-Christian spiritual practices (e.g. pagan, New Age religions) (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Escher et al. Citation2019). Two studies mentioned that participants engaged in SGD affirming congregations and SGD friendly institutions (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002).

Other community-based practices included mind-body therapies and practices, such as deep breathing exercises and formal meditation (e.g. mindfulness-based stress reduction) (Anderson et al. Citation2021), and reflective exercises, yoga, qigong, and Tai Chi. Finally, volunteering was used to improve mental wellbeing, with one study exploring the positive impacts of volunteering in both LGBTI and non-LGBTI organizations (Lyons et al. Citation2021).

One experimental study explored the use of two group teletherapy initiatives for older men who have sex with men and live with HIV/AIDS (Heckman et al. Citation2014). Participants in the study were randomized to receive Coping Effectiveness Training combined with Standard of Care, Supportive-Expressive Group Therapy with Standard of Care or Standard of Care only. The Coping Effectiveness Training was based on Lazarus and Folkman’s Transactional Model of Stress and Coping. The training taught participants to use cognitive-behavioral principles to appraise stress, develop coping skills, use social support to cope, and determine the match between coping strategies and stressor controllability. The Supportive-Expressive Group Therapy derived from humanistic psychology and involved participants exploring their feelings about the difficulties related to the aging process, being HIV positive, and living with HIV/AIDS as an older adult. Participants in the Standard of Care group had the usual access to community-based support services (e.g. individual therapy and 12-step programmes).

Only two studies mentioned the use of formal programmes. In one study, these were used for treatment of alcoholism (Rowan & Butler, Citation2014). Programmes included 12-step recovery groups (Al-anon or alcoholics anonymous) and Adult Children of Alcoholics (ACOA) group. Another study briefly mentioned social and education programmes; however, it was unclear what these entailed and aimed to improve (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014).

Length, mode of delivery and format

As demonstrated in Table 3 (supplementary file), most studies did not specifically report the length, mode of delivery or format of community-based support. For those that reported on frequency or length of sessions, these ranged from weekly for six weeks (Hughes et al. Citation2014) to weekly 90-minute sessions for twelve weeks (Heckman et al. Citation2014). Others reported fortnightly (Misgav, Citation2016) or monthly (Traies, Citation2015) meetings.

Most studies that reported mode of delivery identified this was in-person (Misgav, Citation2016; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002; Valenti et al. Citation2021). In one of these studies, sessions were delivered both online and in-person (Valenti et al. Citation2021). Other modes of delivery included an initiative via telephone (Heckman et al. Citation2014) and religious engagement by listening to services and music on the radio or watching religious television programs (Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002).

In the studies that specifically reported format, most were within a group context (e.g. attending religious services or group meetings) (Averett et al. Citation2011; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020; Heckman et al. Citation2014; Hughes et al. Citation2014; Lyons, Citation2016; Lyons et al. Citation2021; Misgav, Citation2016; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002; Traies, Citation2015; Valenti et al. Citation2021). In some studies, it was unclear whether participants engaged with others, used counseling services individually, or used religious or mind-body practices alone (Anderson et al. Citation2021; Escher et al. Citation2019; Sharek et al. Citation2015).

Mental health and wellbeing measures

Various outcomes were measured or referred to in relation to mental health disorders (e.g. depression) (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Escher et al. Citation2019; Heckman et al. Citation2014), addiction (Rowan & Butler, Citation2014) and psychological distress or mental wellbeing (Lyons, Citation2016; Lyons et al. Citation2021). Another common focus was on outcomes relating to social networks and social support (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Lyons, Citation2016; Lyons et al. Citation2021). Other studies explored outcomes relating to social isolation, or loneliness (Escher et al. Citation2019; Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020), belonging or social connection (Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Traies, Citation2015) or coping (Hughes et al. Citation2014; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002).

Only a few quantitative studies reported the use of validated measures. Validated measures included the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Escher et al. Citation2019), UCLA Loneliness Scale (Escher et al. Citation2019), Geriatric Depression Scale (Heckman et al. Citation2014), Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (Lyons, Citation2016; Lyons et al. Citation2021), Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (Lyons et al. Citation2021), and the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (Lyons, Citation2016; Lyons et al. Citation2021).

Qualitative studies primarily used interviews (e.g. biographical, or semi-structured) to collect data on experiences or perceptions (Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002; Valenti et al. Citation2021). Three single studies used interviews and observations (Misgav, Citation2016), interviews and autobiographical writing (Traies, Citation2015), and notes and anecdotal evidence (Hughes et al. Citation2014).

Outcomes on mental health and wellbeing

Positive outcomes were reported in relation to feeling connected and belonging, increased social support, improved mental health, and coping with physical illness (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Escher et al. Citation2019; Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020; Hughes et al. Citation2014; Lyons et al. Citation2021; Misgav, Citation2016; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002; Traies, Citation2015; Valenti et al. Citation2021). Some studies also mentioned negative consequences or null effects in mental health or wellbeing from community-based support (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Escher et al. Citation2019; Heckman et al. Citation2014; Lyons, Citation2016; Traies, Citation2015). Five studies focused on reporting statistics on utilization of community-based support, so were not included in this section (Anderson et al. Citation2021; Averett et al. Citation2011; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Sharek et al. Citation2015; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019).

Positive effects

Engaging in community-based support enabled participants to develop a sense of connection and belonging to the community (Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020; Hughes et al. Citation2014; Misgav, Citation2016; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Traies, Citation2015; Valenti et al. Citation2021). In two studies, participants noted how a network of friends or community was available to them (Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Traies, Citation2015). For example: ‘I remember [ex-partner] saying, when we were splitting up …,“You’re really lucky, because wherever you go in the country you will have a ready-made supply of friends.” And that’s true, isn’t it? You know, there’s always a gay community wherever you go….’ (Traies, Citation2015). Both studies on bereavement support groups also mentioned that commonalities helped them feel connected to the group and to feel their experiences were validated by others in the community facing the same challenge (Hughes et al. Citation2014; Valenti et al. Citation2021). One participant stated, ‘Because the minute your partner, your lover, your best friend, your wife dies, the whole world changes. The whole world just looks different. That’s a commonality in this group.’ (Valenti et al. Citation2021, p. 1674). Engaging in community services (e.g. trans-specific support groups) also gave meaning to older adults’ struggles (Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020).

Some studies reported increased social support and engagement (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Lyons et al. Citation2021; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002). For example, attending an SGD affirming congregation provided participants with a sense of support, including emotional, instrumental, and spiritual support, along with the opportunity for socialization and other activities (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013). Positive impacts of receiving social support and engagement were also found in another study, with a participant stating: ‘…I always stay for the social and other business afterwards. It’s not just—the liturgy is fine, and I’m getting more into that, but I’m not as liturgy centered as I am community centered;’ (Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002, p. 96). Similarly, in a quantitative study, gay men volunteers reported significantly less psychological distress and higher positive mental health and social support than gay men who did not volunteer (Lyons et al. Citation2021). For lesbians, volunteering was associated with significantly higher positive mental health (Lyons et al. Citation2021). Volunteering for LGBTI organizations was associated with higher community connectedness for both lesbian women and gay older adults.

Other studies found positive benefits in relation to improving mental health disorders and coping with physical illness and age-related problems (Escher et al. Citation2019; Misgav, Citation2016; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002). In one study, a greater degree of being ‘out’ to the religious community was associated with less depression and loneliness (Escher et al. Citation2019). However, it should be noted that more religious engagement was also associated with more loneliness and depression, particularly for lesbian women. Improved ability to cope was evident in participants with HIV/AIDS participating in religion or spirituality (Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002). Finally, engagement in therapy and sobriety programmes helped with coping with stressors of alcoholism (Rowan & Butler, Citation2014).

Negative and null effects

Two studies reported a lack of acceptance and inclusivity due to the religious community not being SGD-affirmative (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Escher et al. Citation2019). In one study, 23% of participants reported that identifying as SGD negatively impacted their participation with religious communities or practices (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013). This finding was frequently a result of conflict between religious teachings and sexual identity. Some participants also reported experiencing a homophobic atmosphere, feeling unwelcome, or being rejected. One man stated: ‘Most [religious congregations] are too straight, so I feel like I don’t belong or I’m uncomfortable with bringing a life partner along’ (p. 81). Participants commonly responded by attending SGD affirming, ‘gay-friendly’ and ‘gay-positive’ congregations. However, patriarchy was identified as a pervasive problem even in ‘gay-positive’ congregations; one woman stated: ‘… my issue is the gender oppression prevalent in all organized religion.’ (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013, p. 82).

Similar findings were demonstrated in another study, where SGD older people changed their religious identity from their childhood affiliation (Escher et al. Citation2019). Some participants moved away from Catholicism and switched to religions that were perceived to be more SGD inclusive, such as Buddhism. The study also demonstrated that older adults who identify as SGD were more likely to experience depression and loneliness when not ‘out’ to the religious community.

Three studies also established that not all participants accessed groups or reported improvements in mental health or wellbeing (Heckman et al. Citation2014; Lyons, Citation2016; Traies, Citation2015). One study examined social groups for lesbians and demonstrated that group meetings were not always accessible (Traies, Citation2015). Specifically, a previously active social group member reported that illness and disability experienced in later life acted as a barrier to further participation, leading to isolation from the community. Perceptions that socializing with other lesbians would not be helpful also reduced community engagement.

Similarly, Supportive-Expressive Group Therapy was not beneficial for everyone who participated (Heckman et al. Citation2014). While older heterosexuals living with HIV reported significant reductions in depressive symptoms at post-intervention, four months, and eight months follow-up, this trend was not evident for older men who have sex with men. Lyons (Citation2016) was also unable to find positive effects in relation to support from community or Government Agencies (e.g. gay organizations or counselors). Findings demonstrated that there was no significant association between psychological distress and receiving support from a romantic partner, friends, government agencies, or community (Lyons, Citation2016). Psychological distress was also not associated with feeling connected to the gay community, living alone, or being in a stable relationship.

Discussion

This scoping review systematically identified research on community-based support, used by older SGD adults, that aims to improve mental health or wellbeing. Globally, there has been an increased interest in the mental wellbeing of older adults and, more recently, aging adults who identify as SGD. However, to our knowledge, this is the first synthesis and mapping of support used by this community. It is evident from the review that there is little research in this area, providing strong motivation for development and trialing of community-based support.

The small body of work in this area showed that a variety of community-based supports were used. LGBT social groups and meetings were the most frequently reported. Other support included bereavement and social support groups for HIV, LGBT organizations, and centres, along with mental health providers such as therapists or counselors. Practices included various spiritual, religious, and non-religious practices, such as mind-body therapies and volunteering. Programmes and initiatives were less frequently reported but included formal programmes to support those with alcohol addiction (e.g. alcoholics anonymous) and a novel teletherapy initiative testing Supportive-Expressive Group therapy and Coping Effectiveness Training.

Various benefits relating to mental health and wellbeing were reported across the studies. These included improving feelings of depression and loneliness and coping with HIV/AIDS (Escher et al. Citation2019; Misgav, Citation2016; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002) and feeling connected to the community (Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020; Hughes et al. Citation2014; Misgav, Citation2016; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Traies, Citation2015; Valenti et al. Citation2021). Increased social support was evident (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Lyons et al. Citation2021; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002) and acts as protective factors of adverse mental health outcomes (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Emlet, et al. Citation2013). However, it is essential to note that only one study was a randomized controlled trial, so it is not possible to infer causality on the effectiveness of community-based support. Further experimental research purposely designed to compare various types of community-based support is needed.

Results from this review highlighted that not all participants benefited from community-based support, and some also reported negative consequences. For example, participants engaging in religious practices and communities reported on homophobia, rejection and lack of acceptance and inclusivity (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Escher et al. Citation2019). Findings also indicated that those who were not ‘out’ to their religious community were more likely to report being depressed and lonely (Escher et al. Citation2019). Such experiences negatively affected participation, with some participants changing their religious affiliation to seek more LGBT affirming congregations (Escher et al. Citation2019). Negative experiences with religious and other services (e.g. for mental healthcare) are frequently reported by the SGD community and directly impact mental health outcomes. The effects of discrimination have been found to be associated with an increased risk of severe mental health problems (Kidd et al. Citation2016).

The findings indicated that organizations and practices that had a dedicated focus or commitment to provision for SGD people were those that led to more positive mental health and wellbeing outcomes. For example, volunteering for LGBT organizations was associated with more community connectedness for lesbian women and gay men than volunteering for non-LGBTI organizations (Lyons et al. Citation2021). Similarly, attending an SGD affirming congregation provided participants with support, along with the chance to socialize and engage in additional activities (Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013). Other studies also demonstrated that participants benefitted from community-based support and programmes developed for the SGD community. This was particularly evident in the bereavement groups where participants felt more comfortable with other women who also shared the experience of losing a lesbian partner (Valenti et al. Citation2021). There is a lack of research comparing SGD specific and non-SGD community-based support. However, findings are consistent with previous recommendations to develop and implement culturally responsive services to improve SGD mental health outcomes (Cummings et al. Citation2021). Findings also indicate that SGD older adults require support that reflects, is constituted by, or specifically targeted for this community.

Although almost half of the studies included transgender participants, only one focused on transgender and gender diverse participants (Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020). Studies which included transgender participants either did not report on disaggregated findings specific to this group of participants, or the small number of transgender participants was discussed as a limitation to performing quantitative analysis. This review therefore highlights the need for research to identify what services are specifically used by and effective for gender diverse older people.

From the studies that reported the mode of delivery, most community-based support was delivered in-person (Misgav, Citation2016; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002; Valenti et al. Citation2021). Only one study reported a combined approach; in this regard the bereavement group was held both online and face-to-face (Valenti et al. Citation2021). Accessing initiatives, practices, or support in person may be challenging for participants residing in rural communities or for those where travel may not be feasible (e.g. due to age or adverse health) (Lee & Quam, Citation2013; Traies, Citation2015). Providing in-person and online delivery options may remove geographical barriers while also ensuring that individual preferences are met and catering for varying abilities to use technology (Quan-Haase et al. Citation2017; Vroman et al. Citation2015).

Most studies reported that community-based support was conducted in groups, with some containing six to eight members (Averett et al. Citation2011; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2013; Brennan-Ing et al. Citation2014; Fabbre & Gaveras, Citation2020; Heckman et al. Citation2014; Hughes et al. Citation2014; Lyons, Citation2016; Lyons et al. Citation2021; Misgav, Citation2016; Rowan & Butler, Citation2014; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019; Siegel & Schrimshaw, Citation2002; Traies, Citation2015; Valenti et al. Citation2021). However, some participants may not feel comfortable in a group environment, including those with significant mental health issues, and group settings may be more complex for those who are less/not ‘out,’ or questioning. Interventions reported in previous aging literature, such as buddy systems (befriending), provide opportunities for social connection while removing barriers relating to group engagement (Andrews et al. Citation2003; Masi et al. Citation2011; O’Rourke et al. Citation2018). A recent study with SGD older adults demonstrated that a telephone calling program improved social isolation and loneliness (Perone et al. Citation2020). However, the program relied on volunteer ‘buddies’ from different age groups, and the generation gap in which different cohorts of SGD people have had radically different experiences of socio-political context might affect sense of connection. While promising, the study was not included in the review as participants were younger (≥ 45 years) than our specified age criteria.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this review was that it was conducted by following the process developed by Arksey and O’Malley and reporting in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Tricco et al. Citation2018). The study also included samples of people who had health conditions, such as prostate cancer, to ensure diversity and a better understanding of the services available. However, these groups may have unique needs and experiences of mental health and wellbeing, so the support may not be helpful for ‘healthy’ populations.

A key limitation of the review was the sample inclusion criteria specifying SGM older adults (50 years of age and older). The exclusion criteria also specified that studies were excluded if any participants were aged 49 years and under. Consequently, this may have excluded programs which aimed to improve the health of SGD older adults but also involved younger participants. A focus on intergenerational programs is needed in future research. This age range may have limited the inclusion of interventions aimed at older adults of color, who often experience age-related health issues earlier (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Citation2018; Goosby et al. Citation2018; Perone et al. Citation2020). The search term ‘same-gender-loving’ (SGL), commonly used in the United States in Black communities, was not employed in the search strategy and should be employed in future reviews. It is also important to acknowledge the lack of ethnic and racial diversity in the existing research, as participants were primarily white/Caucasian. Developing community-based support to meet the needs of SGD older adults of color is crucial in future research.

The review was also limited to studies published in English, and the authors did not seek grey literature for inclusion. While it is likely that the studies were of higher quality (than grey literature), some relevant research may have been overlooked. Lastly, studies that did not specifically report mental health and wellbeing outcomes were also included in the review. As such, the authors were unable to extensively report on the usefulness and effectiveness of the community-based support included.

Future research

Above all, experimental research and full systematic reviews are needed to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of different types of community-based support on mental health and wellbeing for older SGD people. This should include targeted interventions, programmes and research questions focused on the specific groups within the SGD umbrella, including ethnically and racially diverse SGD older adults, and older gender diverse adults. More detailed reporting on types, format, mode of delivery and duration of support is needed in future research, as this was found to be significantly lacking in current research. Research should also aim to develop more SGD-specific and led interventions, particularly ones provided by SGD organizations. Future community-based support should be developed with consideration for individual preferences regarding group size and access barriers. These could include the use of combined (in-person and virtual) group meetings or buddy systems to create opportunities for older adults to befriend and socialize with others who identify with this community.

Results here found categorization of and terms for sex and gender were mostly used inaccurately. This highlights a need for future researchers to develop awareness of the rapidly evolving identity terms and nomenclature used by and about SGD people. Critical reflexivity in relation to methodologies and instruments used for data collection from this community is needed (Ollen & Vencill, Citation2021). All studies included in this review focused on micro or mezzo-level programs. However, SGD older adults are also engaged in important community organizing and advocacy efforts that may influence mental health and wellbeing. Future research should examine such macro-level programmes and initiatives.

Conclusions

The mental health and wellbeing of older adults who identify as SGD is a largely under-researched, yet important area. Evidence to date suggests that SGD older people use various community-based supports. However, it is unclear which is most effective in improving mental health or wellbeing from the evidence available. A full systematic review of evolving evidence and further experimental, and qualitative research are needed to understand how to best improve the mental health and wellbeing of older SGD adults.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (54.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Sex is a category assigned at birth on the basis of sex characteristics in relation to chromosomes, genes, external genitalia, internal reproductive organs, hormones, or other secondary characteristics (Jones, Citation2018).

References

- Anderson, J. G., Bartmess, M., Jabson Tree, J. M., & Flatt, J. D. (2021). Predictors of mind-body therapy use among sexual minority older adults. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (New York, N.Y.), 27(4), 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2020.0430

- Andrews, G. J., Gavin, N., Begley, S., & Brodie, D. (2003). Assisting friendships, combating loneliness: Users’ views on a ‘befriending’ scheme. Ageing and Society, 23(3), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X03001156

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Averett, P., Yoon, I., & Jenkins, C. L. (2011). Older lesbians: Experiences of aging, discrimination and resilience. Journal of Women & Aging, 23(3), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2011.587742

- Brennan-Ing, M., Seidel, L., Larson, B., & Karpiak, S. E. (2013). “I’m created in god’s image, and god don’t create junk”: Religious participation and support among older GLBT adults. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 25(2), 70–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528030.2013.746629

- Brennan-Ing, M., Seidel, L., Larson, B., & Karpiak, S. E. (2014). Social care networks and older LGBT adults: Challenges for the future. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(1), 21–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.835235

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2014). Older adults reporting social isolation or loneliness show poorer cognitive function 4 years later. Evidence-Based Nursing, 17(2), 59–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2013-101379

- Choi, S. K., Meyer, I. H. (2016). LGBT Aging: A Review of Research Findings, Needs, and Policy Implications. The Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Aging-Aug-2016.pdf

- Colledge, L., Hickson, F., Reid, D., & Weatherburn, P. (2015). Poorer mental health in UK bisexual women than lesbians: Evidence from the UK 2007 Stonewall Women’s Health Survey. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 37(3), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdu105

- Cummings, C. R., Dunkle, J. S., Mayes, B. C., Bradley, C. A., Petruzzella, F., & Maguire, K. (2021). As we age: Listening to the voice of LGBTQ older adults. Social Work in Public Health, 36(4), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2021.1904081

- Dunkle, J. S. (2018). Indifference to the difference? Older lesbian and gay men’s perceptions of aging services. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 61(4), 432–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2018.1451939

- Escher, C., Gomez, R., Paulraj, S., Ma, F., Spies-Upton, S., Cummings, C., Brown, L. M., Thomas Tormala, T., & Goldblum, P. (2019). Relations of religion with depression and loneliness in older sexual and gender minority adults. Clinical Gerontologist, 42(2), 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1514341

- Fabbre, V. D., & Gaveras, E. (2020). The manifestation of multilevel stigma in the lived experiences of transgender and gender nonconforming older adults. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(3), 350–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000440

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. (2018). Shifting social context in the lives of LGBTQ older adults. The Public Policy and Aging Report, 28(1), 24–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppar/pry003

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Emlet, C. A., Kim, H. J., Muraco, A., Erosheva, E. A., Goldsen, J., & Hoy-Ellis, C. P. (2013). The physical and mental health of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual (LGB) older adults: The role of key health indicators and risk and protective factors. The Gerontologist, 53(4), 664–675. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns123

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H., Emlet, C. A., Muraco, A., Erosheva, E. A., Hoy-Ellis, C. P., Goldsen, J., & Petry, H. (2011). The aging and health report: Disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Institute for Multigenerational Health.

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H. J., Barkan, S. E., Muraco, A., & Hoy-Ellis, C. P. (2013). Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1802–1809. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110

- Friedman, E. M., Ruini, C., Foy, R., Jaros, L., Sampson, H., & Ryff, C. D. (2017). Lighten UP! A community-based group intervention to promote psychological well-being in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 21(2), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1093605

- Galinha, I. C., Fernandes, H. M., Lima, M. L., & Palmeira, A. L. (2023). Intervention and mediation effects of a community-based singing group on older adults’ perceived physical and mental health: The Sing4Health randomized controlled trial. Psychology & Health, 38(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2021.1955117

- Golden, J., Conroy, R. M., & Lawlor, B. A. (2009). Social support network structure in older people: Underlying dimensions and association with psychological and physical health. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 14(3), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500902730135

- Goosby, B. J., Cheadle, J. E., & Mitchell, C. (2018). Stress-related biosocial mechanisms of discrimination and African American health inequities. Annual Review of Sociology, 44(1), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-

- Heckman, B. D., Lovejoy, T. I., Heckman, T. G., Anderson, T., Grimes, T., Sutton, M., & Bianco, J. A. (2014). The moderating role of sexual identity in group teletherapy for adults aging with HIV. Behavioral Medicine (Washington, D.C.), 40(3), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2014.925417

- Hughes, A. K., Waters, P., Herrick, C. D., & Pelon, S. (2014). Notes from the field: Developing a support group for older lesbian and gay community members who have lost a partner. LGBT Health, 1(4), 323–326. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2014.0039

- Jenkins Morales, M., King, M. D., Hiler, H., Coopwood, M. S., & Wayland, S. (2014). The Greater St. Louis LGBT Health and Human Services Needs Assessment: An examination of the Silent and Baby Boom generations. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.835239

- Jones, T. (2018). Intersex studies: A systematic review of international health literature. SAGE Open, 8(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017745577

- Kidd, S. A., Howison, M., Pilling, M., Ross, L. E., & McKenzie, K. (2016). Severe mental illness in LGBT populations: A scoping review. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 67(7), 779–783. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500209

- Killen, A., & Macaskill, A. (2015). Using a gratitude intervention to enhance well-being in older adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(4), 947–964. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9542-3

- Kneale, D., Henley, J., Thomas, J., & French, R. (2021). Inequalities in older LGBT people’s health and care needs in the United Kingdom: A systematic scoping review. Ageing and Society, 41(3), 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x19001326

- Langhammer, B., Bergland, A., & Rydwik, E. (2018). The importance of physical activity exercise among older people. BioMed Research International, 2018, 7856823–7856823. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7856823

- Lee, M. G., & Quam, J. K. (2013). Comparing supports for LGBT aging in rural versus urban areas. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 56(2), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2012.747580

- Luanaigh, C. O., & Lawlor, B. A. (2008). Loneliness and the health of older people. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(12), 1213–1221. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2054

- Lyons, A. (2016). Social support and the mental health of older gay men: Findings from a national community-based survey. Research on Aging, 38(2), 234–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027515588996

- Lyons, A., Alba, B., Waling, A., Minichiello, V., Hughes, M., Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Edmonds, S., Blanchard, M., & Irlam, C. (2021). Volunteering among older lesbian and gay adults: Associations with mental, physical and social well-being. Journal of Aging and Health, 33(1-2), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264320952910

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review : An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 15(3), 219–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377394

- Misgav, C. (2016). Gay-riatrics: Spatial politics and activism of gay seniors in Tel-Aviv’s gay community centre. Gender, Place & Culture, 23(11), 1519–1534. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2016.1219320

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- O’Rourke, H. M., Collins, L., & Sidani, S. (2018). Interventions to address social connectedness and loneliness for older adults: A scoping review. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0897-x

- Ollen, E. W., & Vencill, J. A. (2021). Measurement of sexuality for trans and gender diverse populations: Application of the 2021 APA Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Sexual Minority Persons. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 8(3), 378–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000529

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan - A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Perone, A. K., Ingersoll-Dayton, B., & Watkins-Dukhie, K. (2020). Social isolation loneliness among LGBT older adults: Lessons learned from a pilot friendly caller program. Clinical Social Work Journal, 48(1), 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-019-00738-8

- Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2014). Positive psychology interventions in people aged 50-79 years: Long-term effects of placebo-controlled online interventions on well-being and depression. Aging & Mental Health, 18(8), 997–1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.899978

- Quan, N. G., Lohman, M. C., Resciniti, N. V., & Friedman, D. B. (2020). A systematic review of interventions for loneliness among older adults living in long-term care facilities. Aging & Mental Health, 24(12), 1945–1955. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1673311

- Quan-Haase, A., Mo, G. Y., & Wellman, B. (2017). Connected seniors: How older adults in East York exchange social support online and offline. Information, Communication & Society, 20(7), 967–983. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1305428

- Rees, S. N., Crowe, M., & Harris, S. (2021). The lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender communities’ mental health care needs and experiences of mental health services: An integrative review of qualitative studies. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 28(4), 578–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12720

- Rowan, N. L., & Butler, S. S. (2014). Resilience in attaining and sustaining sobriety among older lesbians with alcoholism. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57(2-4), 176–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2013.859645

- Sharek, D. B., McCann, E., Sheerin, F., Glacken, M., & Higgins, A. (2015). Older LGBT people’s experiences and concerns with healthcare professionals and services in Ireland. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 10(3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn

- Shnoor, Y., & Berg-Warman, A. (2019). Needs of the aging LGBT community in Israel. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 89(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415019844452

- Siegel, K., & Schrimshaw, E. W. (2002). The perceived benefits of religious and spiritual coping among older adults living with HIV/AIDS. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5906.00103

- Siegler, E. L., Lama, S. D., Knight, M. G., Laureano, E., & Reid, M. C. (2015). Community-based supports and services for older adults: A primer for clinicians. Journal of Geriatrics, 2015, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/678625

- Smith, J. L., & Hanni, A. A. (2019). Effects of a savoring intervention on resilience and well-being of older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology : The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 38(1), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464817693375

- Su, D., Irwin, J. A., Fisher, C., Ramos, A., Kelley, M., Mendoza, D. A. R., & Coleman, J. D. (2016). Mental health disparities within the LGBT population: A comparison between transgender and nontransgender individuals. Transgender Health, 1(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2015.0001

- Thomson, L. J., Lockyer, B., Camic, P. M., & Chatterjee, H. J. (2018). Effects of a museum-based social prescription intervention on quantitative measures of psychological wellbeing in older adults. Perspectives in Public Health, 138(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913917737563

- Traies, J. (2015). Old lesbians in the UK: Community and friendship. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 19(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2015.959872

- Treichler, E. B. H., Glorioso, D., Lee, E. E., Wu, T. C., Tu, X. M., Daly, R., O’Brien, C., Smith, J. L., & Jeste, D. V. (2020). A pragmatic trial of a group intervention in senior housing communities to increase resilience. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(2), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219002096

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Valenti, K. G., Janssen, L. M., Enguidanos, S., & de Medeiros, K. (2021). We speak a different language: End-of-life and bereavement experiences of older lesbian, gay, and bisexual women who have lost a spouse or partner. Qualitative Health Research, 31(9), 1670–1679. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323211002823

- Viguer, P., Satorres, E., Fortuna, F. B., & Melendez, J. C. (2017). A follow-up study of a reminiscence intervention and its effects on depressed mood, life satisfaction, and well-being in the elderly. The Journal of Psychology, 151(8), 789–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2017.1393379

- Vroman, K. G., Arthanat, S., & Lysack, C. (2015). “Who over 65 is online?” Older adults’ dispositions toward information communication technology. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.018

- Wilkens, J. (2015). Loneliness and belongingness in older lesbians: The role of social groups as “community”. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 19(1), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2015.960295

- Yarns, B. C., Abrams, J. M., Meeks, T. W., & Sewell, D. D. (2016). The mental health of older LGBT adults. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(6), 60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0697-y