Abstract

Objectives

This review seeks to synthesise qualitative studies that focus on the experience of grief and loss in people living with dementia.

Methods

Included studies were quality appraised, synthesised and analysed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results

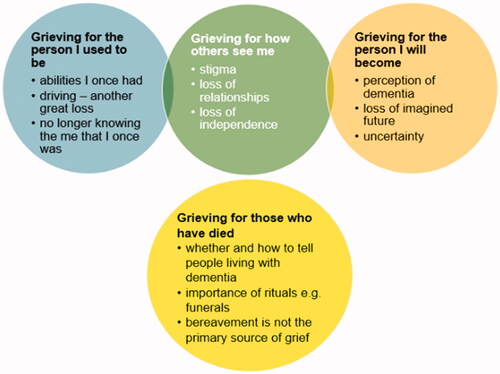

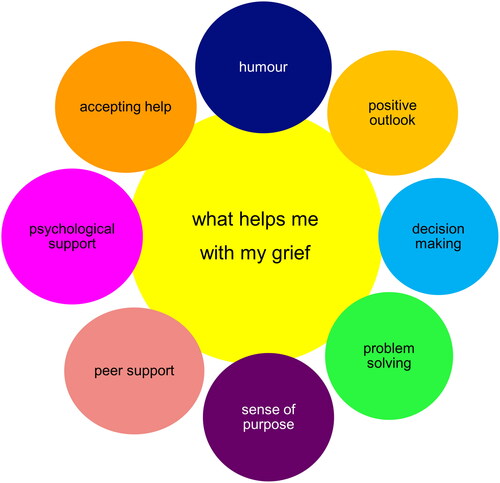

19 studies were selected for inclusion in the final review and metasynthesis, including 486 participants (115 participants living with dementia, 152 family carers, 219 professionals). Five key dimensions of grief in people living with dementia were identified during the analysis process: grieving for the person I used to be, grieving for how others see me, grieving for the person I will become, grieving for those who have died and what helps me with my grief.

Conclusion

It is evident that people living with dementia can experience grief related to a range of previous, current and anticipated losses. Many of the studies included in this review did not directly include people living with dementia in their research and did not ask participants directly about their experience of grief and loss. As grief is a highly personal and individual experience, further research addressing the experience of grief that directly includes participants living with dementia is required, in order to improve awareness of grief-related needs and to develop and deliver support to meet these needs.

Introduction

Dementia encompasses a range of progressive neurological disorders that affect areas of cognitive function including memory, behaviour, vision, mood, communication, problem solving, executive function and mobility (World Health Organisation, Citation2023). Previous research has highlighted the importance of addressing the grief related support needs of family carers, however there has been a noticeable lack of research addressing these needs in people living with dementia (Blandin & Pepin, Citation2017; Chan et al., Citation2013; Crawley et al., Citation2023; Doka, Citation2010; Lindauer & Harvath, Citation2014). This is likely due to the progressive nature of dementia, the perceived impact of cognitive symptoms on the ability of people living with dementia to both experience and express grief, as well as the exclusion of people living with dementia in research more generally (Doka, Citation2010; O’Connor et al., Citation2022; Rentz et al., Citation2005; The Irish Hospice Foundation, Citation2016; Yale, Citation1999).

Grief is a response to any loss that is significant to an individual, and is a process that unfolds in a non-linear manner (Arizmendi & O’Connor, Citation2015; Harris, Citation2019; Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999). While grief is often associated with bereavement, an individual might grieve any form of loss, including the loss of employment, loss or change in relationships, significant life changes, loss of health and loss of the future that was hoped for and imagined (Harris, Citation2019; Harris & Winokuer, Citation2019).

Previous research indicates that people living with dementia may experience grief related to loss of: memory, practical skills, roles, relationships, autonomy, independence, employment, sense of purpose, confidence, and identity, as well as uncertainty related to anticipated future losses (Doka, Citation2010; Ostwald et al. Citation2002; Pearce et al. Citation2002; Snyder & Drego, Citation2006). The progressive nature of dementia does not necessarily equate to a loss of the ability to feel emotions and experience grief, even in the very late stages (Doka, Citation2010; Rando, Citation1993; The Irish Hospice Foundation, Citation2016). It has been suggested that depressive symptoms in the early stages of dementia may reflect a grieving process related to an awareness of loss of abilities (Baloyannis, Citation2011), and that people living with late stage dementia may express grief which is perceived as agitation or anxiety (Doka, Citation2010; Doka & Tucci, Citation2015; Johansson & Grimby, Citation2013; Rando, Citation1993; Rentz et al., Citation2005). Previous research also suggests that current grief theories do not necessarily reflect the unique lived experience of loss in people living with dementia, and further research is needed to better understand this process (Rentz et al., Citation2005).

Snyder and Drego (Citation2006) previously conducted a review of the experience of loss in people living with Alzheimer’s disease. This review found that people living with dementia experienced losses related to function and cognition, meaningful activities, relationships with others, self-esteem and identity, and used coping strategies such as companionship, advocacy, seeking help and developing different perspectives. While this initial review helped to illuminate a previously underexplored domain, it did not provide crucial details regarding research methodology and analytical approach. Furthermore, the sample was restricted to individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease, emphasising the need for a more comprehensive review.

To enable the development of person-centred support services for people living with dementia, we need to better understand their experience of grief. Building on previous research, the current study seeks to synthesise qualitative studies that focus on the experience of grief in people living with dementia, to create a more coherent picture and to identify current gaps.

Objective: We systematically reviewed the literature using the following questions:

How do people living with dementia experience grief?

What support, strategies and interventions are used to navigate and cope with the grieving process in people living with dementia?

Materials and methods

A qualitative metasynthesis approach was selected to enable multiple sources of qualitative evidence to be integrated and interpreted, in order to provide deeper insight and identify potential research gaps (Erwin et al., Citation2011; Lachal et al., Citation2017). The focus on qualitative research was used due to the complexity and individuality of the grief experience and to build on previous research. Additionally, to the authors’ knowledge there are currently no quantitative measures of grief that have been validated in people living with dementia.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance (Page et al., Citation2021). The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022352687). We searched: PubMed, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL], Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts [ASSIA], Web of Science, Scopus, Embase and Emcare. The search was initially conducted in June 2022, and updated in February 2023 (see appendix for full search strategies).

Duplicates were removed using both manual and automatic de-duplication processes in Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016).

Inclusion criteria

Context: the experience of grief in people living with dementia

Perspective: people living with dementia, family carers or professionals

Publication type: peer reviewed, inclusion of new data, qualitative method and analysis

Language: English

Date range: no limitations

Any studies that did not meet the above criteria were excluded.

Study selection

The first author (CW) screened all papers at all steps of the screening process. The second author (KF) screened ten percent of papers at all stages. Discrepancies were resolved by additional review from the final author (JS).

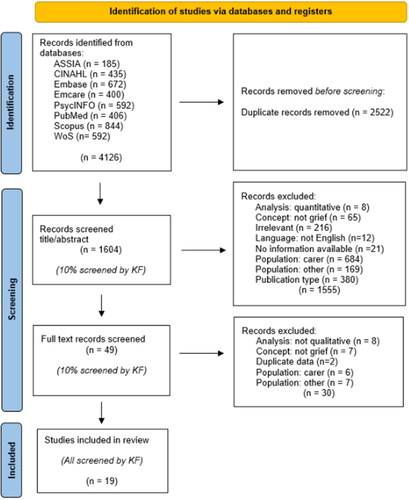

After removing duplicates, 1604 titles and abstracts were screened and subsequently 49 full text papers. Following screening, 19 studies were included for analysis (see ).

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using the revised critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool (Long et al., Citation2020). Following this guidance, authors CW, JS and SC agreed on three deciding criteria relevant to the aims of the current review.

As the review is focused on the subjective experience of grief, studies that directly included participants living with dementia were prioritised over those that only included the perspectives of family carers and/or professionals

Rigorous and clear data analysis was viewed as an area of importance, to ensure that the findings of the review most accurately reflect the real world experience of people living with dementia.

The degree to which the primary studies focused specifically on the experience of grief was used as the third deciding criteria, given the direct relevance to the current enquiry.

Taken together, papers were given a score of high where all three deciding criteria were met, medium where two criteria were met and low quality where only one of the criteria were met.

Data analysis

In line with recommendations (Long et al., Citation2020; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008), the results sections of included studies underwent close examination. Line by line coding was used to describe and summarize the text using NVivo 12 software. Codes were developed using the high quality rated papers first, with additional codes added where relevant from the medium quality papers (Long et al., Citation2020). Papers rated as low quality were coded using the developed framework, with no additional codes added at this stage. Building upon this, broader descriptive codes were developed, and data segments were subsequently assigned a descriptive code to establish categories. Peer checking was used as CW coded all papers, and KF separately developed a coding framework using this process on two of the high quality papers. Discrepancies between coding frameworks were discussed to produce one cohesive framework. Once descriptive themes were identified, they served as the foundation for constructing analytical themes, enabling a more profound understanding of the individual and collective insights obtained from the studies. Direct quotes from source material have been included to illustrate the main themes of the analysis.

Results

Study characteristics

Nineteen studies met criteria for inclusion. Three additional studies were initially included (Kelly, Citation2008a; McAtackney et al., Citation2021; Tan et al., Citation2013), and subsequently excluded following discussion between authors CW and KF. Two due to data duplication with studies already included in the review (Kelly, Citation2008a; Tan et al., Citation2013), and one due to lack of clarity on analysis processes (McAtackney et al., Citation2021). Study characteristics were collated and reviewed independently by CW and KF (see ).

Table 1. Study characteristics.

Five studies were rated as high (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Lo et al., Citation2022; Olsson et al., Citation2013), 11 as medium (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2007; Berenbaum et al., Citation2017; Gruetzner et al., Citation2012; Kelly, Citation2008b; McCleary et al., Citation2018; Nordtug et al., Citation2018; O’Connor et al., Citation2013; Robinson et al., Citation2005; Sanford et al., Citation2019; Watanabe & Suwa, Citation2017; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019), and three as low quality (De Vries & McChrystal, Citation2010; Paananen et al., Citation2021; Smith, Citation2021) (see ). Studies were conducted in nine countries; Australia (4), Canada (3), Finland (1), Israel (1), Japan (1), Norway (1), Sweden (3), the UK (3) and the USA (2). 486 participants were included across selected studies (115 participants living with dementia, 152 family carers, 219 professionals). Two studies did not provide any demographic details for participants living with dementia (Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Kelly, Citation2008b) and three did not provide diagnostic information (Nordtug et al., Citation2018; O’Connor et al., Citation2013; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019).

Table 2. Quality rating of included papers using deciding criteria.

Thematic analysis

Five key dimensions of grief were identified: grieving for the person I used to be, grieving for how others see me, grieving for the person I will become, grieving for those who have died and what helps me with my grief. The first four dimensions are shown in and the fifth in . Dimensions are outlined below, with quotes from the original studies. Discrepancies are highlighted.

Grieving for the person I used to be

Grieving for the abilities I once had

Many participants felt that they were now a fundamentally different person to who they were prior to diagnosis.

Yes, it feels empty, as if parts of my life are gone. It feels … yes it is tedious. Unfortunately, I have lost the foundation for my life. (Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003)

Participants expressed grief in relation to a range of prior skills and abilities they felt had been lost or impaired due to their diagnosis, including: memory, vision, reading and writing, creativity, communication, maintaining personal appearance, travel, living in their own home, hobbies, employment and completing household tasks (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2007; De Vries & McChrystal, Citation2010; Hedman et al., Citation2016; Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Lo et al., Citation2022; Nordtug et al., Citation2018; O’Connor et al., Citation2013; Olsson et al., Citation2013; Paananen et al., Citation2021; Robinson et al., Citation2005; Sanford et al., Citation2019; Smith, Citation2021; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019).

I’m in denial and still in partial denial… I’ve lost my independence and I’m alarmed at the loss of my ability to converse and or to just have a conversation and to be the person that I used to be ()… (Joshua) (Lo et al., Citation2022)

The process of acknowledging changes to abilities was often met with feelings of frustration, denial, anxiety, low mood and anger (Kelly, Citation2008b; Lo et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2005; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019). Comparisons between one’s perceived current self to one’s pre-dementia self also had a negative impact on sense of autonomy, independence, control, self-esteem, safety, dignity and identity (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2007; De Vries & McChrystal, Citation2010; Hedman et al., Citation2016; Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Lo et al., Citation2022; Nordtug et al., Citation2018; O’Connor et al., Citation2013; Olsson et al., Citation2013; Robinson et al., Citation2005; Sanford et al., Citation2019; Smith, Citation2021; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019).

()…she clearly knows that there is some cognitive decline, with her memory loss and things like that. Which is very upsetting for her. And not being able to function. And she’s living a lot in the past, in, ‘well, I used to be able to do this.’ She had a very vibrant, active lifestyle. So she’s also lamenting the loss of that. (CP12; Adult daughter of ex-driver) (Sanford et al., Citation2019)

It is important to note that not all comparisons to one’s pre-dementia self led to feelings of loss (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Nordtug et al., Citation2018; Robinson et al., Citation2005). For instance, some participants with dementia expressed feelings of pride when speaking about their previous achievements, particularly in reference to employed roles (Nordtug et al., Citation2018).

Driving – one great loss in a series of losses

Six papers touched on grief and losses specifically related to driving cessation (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Olsson et al., Citation2013; Sanford et al., Citation2019; Smith, Citation2021). This appeared to relate not only to driving itself, but also to the loss of independence, identity, freedom, autonomy, self-worth, roles and access to community activities and regular routines that accompanied the ability to drive. People living with dementia expressed feelings of helplessness, sadness, anger and frustration at the loss of driving privileges (Liddle et al., Citation2013; Sanford et al., Citation2019).

. . I liken the trauma of losing her vehicle; the use of her vehicle, was as traumatic as losing my dad. It was like losing a spouse. And so, just like you have grief counselling for losing a spouse, you should have grief counselling for transitioning to nondriving. (CP12; Adult daughter of ex-driver) (Sanford et al., Citation2019).

People living with dementia experienced significant challenges in accepting and adjusting to driving cessation, particularly when the decision to stop driving was made by others, most commonly professionals and family members (Liddle et al., Citation2013). People living with dementia did not always agree on the decision to stop driving, and driving cessation frequently occurred suddenly, rather than as a gradual process that might better enable acceptance and adjustment (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Sanford et al., Citation2019; Smith, Citation2021).

No longer knowing the me that I once was

Memory loss, changes in awareness and apathy were viewed by professionals and family carers as being a protective factor in minimising the grief and distress experienced by people living with dementia in relation to driving cessation, no longer being aware of loss of abilities, and coping with isolation policies imposed due to COVID-19 (Paananen et al., Citation2021; Sanford et al., Citation2019; Smith, Citation2021).

Grieving for how others see me

People living with dementia also experienced grief in relation to how they were perceived by others. In certain cases this led to concealing or minimising symptoms and not disclosing their diagnosis, in order to maintain a sense of normality, dignity and self-esteem (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2007; Hedman et al., Citation2016; Lo et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2005). Changes in abilities also had a profound impact on how people living with dementia felt that they were perceived by those around them (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Lo et al., Citation2022; Nordtug et al., Citation2018; Sanford et al., Citation2019).

I sometimes find it difficult to express myself, I cannot find the words, and therefore I avoid talking to others. (Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003)

Participants conveyed that they found it more difficult to connect with other people, due to their own withdrawal from social activities and avoidance and reduced contact from friends, family and community members following diagnosis disclosure (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Lo et al., Citation2022). People living with dementia expressed that they felt lonely and isolated due to a change or loss of relationships with others (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2007; Hedman et al., Citation2016; O’Connor et al., Citation2013; Watanabe & Suwa, Citation2017).

I can’t say you have a bad life but you’re missing something, I can’t really express what kind of life it is that you have. There aren’t that many who care about you. You don’t have many people call (). I don’t take much initiative either, sitting there, stuttering (Hedman et al., Citation2016).

Additionally, people living with dementia shared that they felt frustrated when they needed to ask others for additional help with tasks that they previously could have completed, such as remembering things and getting dressed (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019). In some cases, participants felt that their family did not understand what support they needed, and would sometimes speak about their abilities in a hurtful or detrimental way, which would further reduce their own sense of self-worth (Robinson et al., Citation2005). Participants with dementia also spoke about not wanting to be a burden or be dependent on those around them (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Lo et al., Citation2022).

So you don’t want to go and ask for the umpteenth time (). Yes, but I told you already, she says (). It doesn’t feel good (). I go and do something else (). You would think that … they would be a bit insightful about this (Hedman et al., Citation2016)

Additionally, some participants expressed concerns about the impact of their diagnosis on their relatives, both now and in the future (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Lo et al., Citation2022).

Grieving for the person I will become

People living with dementia also grieved for anticipated future losses as their condition progressed, in some cases because they had a relative who had also lived with dementia (Lo et al., Citation2022; Smith, Citation2021).

Well Alzheimer’s, which is a part of or a form of, all just a death sentence. And I have a very negative concept of Alzheimer’s because my-uncle my-uncle died from it. (Joshua) (Lo et al., Citation2022)

Potential future losses included; moving home due to care needs, loss of independence and agency leading to greater reliance on others, driving cessation, further loss of communication and navigation skills, concerns about changes in personality and behaviour and fear of dying (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2007; De Vries & McChrystal, Citation2010; Hedman et al., Citation2016; Kelly, Citation2008b; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Lo et al., Citation2022; Olsson et al., Citation2013; Sanford et al., Citation2019). There was a general sense of the loss of the life that people living with dementia had hoped for and imagined that they were no longer able to live.

I think that’s the-only the-only thing that-that I felt would be terrible if-if get worse and worse and worse what happens to you? You just not be able to be talking at all? Does-that does-that ever happen? I mean is that, do you know? (Anthea) (Lo et al., Citation2022)

Participants struggled with feelings of uncertainty and loss of control regarding how or when their symptoms might progress, making it difficult to make decisions and plan for the future while also trying to live well in the present (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2007; Hedman et al., Citation2016; Kelly, Citation2008b; Lo et al., Citation2022; Olsson et al., Citation2013; Robinson et al., Citation2005).

However, it is important to note that while a number of participants shared that they had a fear of dying, not all participants expressed this fear, in some cases speaking about hoping for death (Kelly, Citation2008b).

Grieving for those who have died

Five studies specifically focused on bereavement-related grief in people living with dementia, relating to the death of family members and other care home residents and day centre attendees (Berenbaum et al., Citation2017; Gruetzner et al., Citation2012; McCleary et al., Citation2018; O’Connor et al., Citation2013; Watanabe & Suwa, Citation2017). Opinions differed on whether or not to inform people living with dementia of a death, and staff and family members did not always agree (Berenbaum et al., Citation2017; Gruetzner et al., Citation2012; McCleary et al., Citation2018; Watanabe & Suwa, Citation2017). Some participants felt that everyone had a right to be informed; others felt that telling people living with dementia would lead to unnecessary distress. There were concerns about needing to inform someone living with dementia multiple times about a death, due to memory-related symptoms, and the ongoing impact of this ‘re-bereavement’ grief (Berenbaum et al., Citation2017; Gruetzner et al., Citation2012; Watanabe & Suwa, Citation2017). There were also different views on how and who is best placed to inform, and how to best support the person living with dementia following this (Berenbaum et al., Citation2017; McCleary et al., Citation2018).

I think there are times when there is no point to tell the people when they are very deep in their own world, in their own bubble. On the other hand when the client does have some orientation to his surroundings—one must tell him. (Berenbaum et al., Citation2017)

Some residents and staff felt that the death of other residents was not the primary source of grief for people living with dementia, who were living through several losses related to both their diagnosis and their transition to living in a care home.

I feel that death is not the biggest thing for them here to grieve about, the residents, it’s other stuff such as losing their home and their possessions and in some cases their family (O’Connor et al., Citation2013)

Oh no, it doesn’t bother me being surrounded by the elderly and dying. I know I’m getting old. I mean that’s how it is isn’t it? (O’Connor et al., Citation2013)

Bereavement support

Family members and professionals also shared the importance of rituals in supporting people living with dementia following the loss of other residents. Care homes and day centres had various policies in place following resident’s death, such as sharing memorial lists and photos, prayers, lighting candles, acknowledging the person’s death at a mealtime, sharing funeral eulogies and involving people living with dementia in the funeral (Berenbaum et al., Citation2017; McCleary et al., Citation2018; Watanabe & Suwa, Citation2017).

Professionals and family members generally felt that there was insufficient support to address the grief experienced by people living with dementia following bereavement, due to a lack of information and guidance on how to approach this (Berenbaum et al., Citation2017; Gruetzner et al., Citation2012; McCleary et al., Citation2018). Because of this, the person living with dementia was often excluded from grieving together with their family.

I feel that our clients sometimes lead us and are more ready for these issues than we are. They want to talk about death and express it. We have to learn how to let them express these feelings and the staff has to be more comfortable with itself—allowing them to express the fear, depression, even their own readiness, their frustration with their lives, with pain and sadness. I don’t think we are so good at that because of our own discomfort. (Berenbaum et al., Citation2017)

What helps me with my grief

People living with dementia used a number of strategies to cope with losses related to their diagnosis. These included, but were not limited to: humour, a positive outlook, decision-making, problem solving, a sense of purpose, peer support, psychological support and accepting help.

Humour

Humour was used by a number of participants (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Lo et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2005; Sanford et al., Citation2019; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019). Importantly, while using humour as a coping strategy was often helpful, it did not necessarily always work to alleviate grief.

No, then I could not laugh anymore. Then I burst into tears … .(Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003)

Positive outlook

A number of participants expressed that they found it helpful to have a positive outlook, to focus on their strengths and abilities and to celebrate their achievements (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2007; Hedman et al., Citation2016; Lo et al., Citation2022; Nordtug et al., Citation2018; O’Connor et al., Citation2013; Olsson et al., Citation2013; Robinson et al., Citation2005; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019).

I don’t panic… I would do my best to do what I can and very lucky… I live in a lovely home and I’m very close to my family and I’ve got things to do, I’ve got lovely neighbours. (Julia) (Lo et al., Citation2022)

Decision making

Decision making gave some people living with dementia a sense of control while living with uncertainty about the future (Kelly, Citation2008b; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Olsson et al., Citation2013). For instance, those who made the decision to stop driving at an early stage were more able to accept this decision and make adjustments, including accessing community transport options and support services and modifying usual routines (Liddle et al., Citation2013). People living with dementia also shared that they wanted to be involved in decisions around day to day activities such as grocery shopping and managing finances, as well as making decisions about the future, including decisions to refuse treatment (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Kelly, Citation2008b; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Lo et al., Citation2022; Smith, Citation2021).

Life quality is being able to move around and go where you want and where you’re allowed to go (Olsson et al., Citation2013)

Problem solving

In many cases, people living with dementia tried to either adapt current activities and roles, or look for feasible alternatives. These adaptations included adjusting to the role of a passenger, using memory and communication aids, brain training (crosswords and puzzles), and focusing on enjoyable activities, such as; spending time in the garden, painting, listening to music, walking and visiting galleries (De Vries & McChrystal, Citation2010; Hedman et al., Citation2016; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Lo et al., Citation2022; Olsson et al., Citation2013; Robinson et al., Citation2005; Sanford et al., Citation2019; Smith, Citation2021; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019). Adaptations would often involve a period of uncertainty and distress while the person with dementia adjusted to the new way of being.

I do what I want today, but maybe I have to do it differently than I did before I got this (dementia) (Olsson et al., Citation2013)

Sense of purpose

Participants engaged in advocacy groups, dementia friendly and community activities, volunteering, managing finances and other household tasks, employment, creative activities, helping others, hobbies and taking part in research (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Nordtug et al., Citation2018; Olsson et al., Citation2013; Paananen et al., Citation2021; Sanford et al., Citation2019; Smith, Citation2021). These activities led to an increase in feelings of self-esteem, self-worth, confidence and dignity.

[W]ith Alzheimer’s … or really for many people, we all need purpose, right? And so, that’s why the [Alzheimer’s research group] ()… that is something that [my husband] likes, too, because he’s involved and … Because he really likes to be the upfront guy, you know. (CP3; Spouse of current driver) (Sanford et al., Citation2019)

Peer support

Peer support groups were viewed as a helpful source of support, due to shared experiences and understanding that could not necessarily be provided by friends and family members (Hedman et al., Citation2016; Sanford et al., Citation2019). These groups also provided a space to speak openly.

You can also kind of talk to one another, understand one another more, because the completely healthy ones can’t always () understand how it is (Hedman et al., Citation2016)

Psychological support

Psychological support and counselling were seen as potentially valuable resources, although few participants had engaged with this, primarily due to a lack of access, awareness and availability of specialised services (Liddle et al., Citation2013; Lo et al., Citation2022; Sanford et al., Citation2019). Professionals also acknowledged that there was an unmet need for additional psychological support and counselling services specifically catering to the needs of people living with dementia.

There’s not a lot of counselling or therapy sessions . . available for people with dementia when they have their license taken away. There’s no services like that . . () It’s not our norm that families would bring in a counsellor for somebody with dementia. It’s not a norm, it should be, but it’s not (Sanford et al., Citation2019)

Accepting help

Accepting help from friends, former colleagues, current employers, religious and spiritual communities, professionals and family were seen as important sources of support, although participants noted that it was often difficult to know what help was available, and how to access it (De Vries & McChrystal, Citation2010; Hedman et al., Citation2016; Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Liddle et al., Citation2013; Lo et al., Citation2022; McCleary et al., Citation2018; O’Connor et al., Citation2013; Olsson et al., Citation2013; Robinson et al., Citation2005; Sanford et al., Citation2019; Smith, Citation2021; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019).

I didn’t think that I’d get anything out of the other sessions [speech therapy], but I did so I shouldn’t say no when people are offering to make my life better (Louis) (Lo et al., Citation2022)

Discussion

This review identified five dimensions of grief in people living with dementia: grieving for the person I used to be, grieving for how others see me, grieving for the person I will become, grieving for those who have died and what helps me with my grief.

These dimensions relate closely to the concept of non-finite loss, which involves continued uncertainty, disconnection from society, losses that are unrecognised by others, a sense of helplessness and shame, and lack of rituals to legitimise the loss (Bruce & Schultz, Citation2001; Harris, Citation2019; Harris & Winokuer, Citation2019). People living with dementia experience ongoing uncertainty related to how and when their symptoms will progress. Some participants had withdrawn from activities and people due to their diagnosis, while others felt that people close to them had withdrawn. In some cases, people living with dementia either chose or were told not to disclose their diagnosis to others, due to a sense of shame and stigma (Milne, Citation2010). People living with dementia also found it difficult to access support, particularly counselling, in order to process and validate their sense of loss.

Chronic sorrow (Burke et al., Citation1992; Lindgren et al., Citation1992; Roos, Citation2002), has previously been applied to family carers of people living with dementia (Mayer, Citation2001), as well as people living with Parkinson’s disease (Lindgren, Citation1996) and multiple sclerosis (Hainsworth, Citation1994; Isaksson et al., Citation2007). This concept involves losses that are unpredictable and ongoing and is categorised by changes to one’s identity and concept of self (Roos, Citation2002). This is reflected in people living with dementia comparing their current selves negatively in contrast to their ‘pre-dementia’ selves. Chronic sorrow is also categorised by fluctuations in grief and particular triggers or stress points, clearly evidenced by grief related specifically to driving cessation.

An important aspect of both chronic sorrow and non-finite loss is that grief is often disenfranchised, which is reflected in the dimension grieving for how others see me (Doka & Aber, Citation1989). It is likely that people living with dementia experience disenfranchised grief due to a lack of awareness or understanding of the grieving process in this population, and the perception that typical grief processes do not apply (Berenbaum et al., Citation2017; Doka, Citation2010; Doka & Tucci, Citation2015; Gataric et al., Citation2010; Snyder & Drego, Citation2006; Wyatt & Liggett, Citation2019). There is a general lack of validation and acknowledgment of grief in people affected by dementia, including those living with, and those who are caring. As shown by the current review, people living with dementia are sometimes assumed to be unable to grieve because of changes in their cognitive abilities. In other cases they are denied the right to grieve, an example of which is not being informed of the death of a loved one. When professionals and family members do not understand the experience of grief in people living with dementia, they are more likely to exclude the person from sharing their grief, albeit unintentionally (Gruetzner et al., Citation2012).

The third dimension of grief, grieving for the person I will become, aligns with the concept of anticipatory mourning (Rando, Citation2000). Previous research has also suggested that people living with dementia grieve potential future losses in independence and communication (Cronin et al., Citation2016). The current review found that people living with dementia experienced anticipatory mourning related to uncertainty around future progression of symptoms, concerns about future transitions to care homes and in some cases, a fear of dying.

The fifth dimension of grief, what helps me with my grief, included the following categories: humour, a positive outlook, decision-making, problem solving, a sense of purpose, peer support, psychological support and accepting help. These findings are similar to the previous review that categorised the loss-related coping strategies of people living with dementia into the following; finding companionship, remaining active, advocacy, seeking help, altruism, developing perspective and humour (Snyder & Drego, Citation2006). This theme also connects with the resilience reserve described by Windle and colleagues (2023), which includes psychological strengths, practical approaches, continuing with activities, relationships with friends and family, education and peer support.

Robinson et al. (Citation2005) reflected that the process of adjusting to a diagnosis of dementia aligned with the oscillation between loss orientation and restoration orientation, as described by the Dual Process Model (Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999). This oscillation is also reflected in the balance between supporting people living with dementia to acknowledge and validate what they have lost, alongside empowering connections with what skills and abilities remain.

Individual experience

Grief is a unique and individual experience. Increasing our understanding of grief and loss in people living with dementia is essential in order to provide tailored and person centred support to better meet individual needs. The experience of grief in people living with dementia will be impacted by a number of factors related to dementia, including the stage, age of onset, degree of insight, communication abilities and type of dementia (Doka, Citation2010). However, it is important to note that factors that are not directly related to dementia will also be relevant, such as; the type of loss, religious and cultural factors, personal history, personal resources, personality and coping style, gender, relationships and support networks and individual values and meaning (Cronin et al., Citation2016; Harris, Citation2019).

Limitations

There are a number of limitations in the current review. We did not use the term ‘loss’ during the literature search, meaning that some studies may have been missed from the final synthesis where ‘loss’ was the only grief-related terminology used. This decision was made to reduce the number of irrelevant sources that would then be included in the search. The review also excluded sources that were not available in English. A number of papers did not include diagnosis type and in some cases, age and gender of participants. Additionally, most of the included papers only focused on the early stages of dementia, due to the need for capacity to consent to take part. Where papers did focus on the later stages, assumptions were made regarding perceptions of grief related behaviours, which could not be directly confirmed by the people living with dementia themselves. Many of the papers included in the review did not include the direct views of people living with dementia.

However, despite these limitations, as the first review of this scope and nature investigating the experience of grief and loss for people living with dementia, we believe that the findings provide a useful start in identifying gaps and areas for further exploration in this important topic.

Implications

These findings are important in acknowledging that people living with dementia can and do experience grief, and require additional support to cope with this experience. There is a general tendency to encourage people living with dementia to focus on what they can still do, and not what they have lost (Bartlett et al., Citation2017). While it is of course important to focus on strengths and abilities, by focusing only on this, the very real experience of grief and loss is subsequently minimised, discounted or simply denied (Doka, Citation2010). By acknowledging and validating this experience, people living with dementia may feel more able to share their grief more openly with those supporting them, including friends, family and professionals (Doka, Citation2010). This may also lead to further opportunities to build some sense of control amongst so much uncertainty, including planning for the future and sharing with others how to best provide support in the present (Alzheimer Society of Canada, Citation2019).

Future research

Future research should approach people living with dementia directly about their experiences of grief in order to develop appropriate support services based on these findings.

Conclusion

While this review is an important initial step in highlighting the impact of grief on people living with dementia, it also highlights the clear lack of empirical research in this area, particularly studies directly including participants living with dementia. Additional research is therefore needed to better understand this complex and individual experience, to validate the multifaceted experiences of individuals living with dementia and to enable the development of accessible and timely interventions tailored to these unique needs.

Funding

This work is part of the RDS Impact Project (The Impact of Multicomponent Support Groups for Those Living With Rare Dementias) and is supported jointly by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) (grant number ES/S010467/1). The ESRC is a part of UK Research and Innovation. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the ESRC, UK Research and Innovation, National Institute for Health and Care Research, or Department of Health and Social Care. Rare Dementia Support is generously supported by the National Brain Appeal.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the current and former members of the Rare Dementia Support Focus Group for their valuable insight and guidance throughout this research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alzheimer Society of Canada. (2019). Ambiguous loss and grief in dementia: A resource for individuals and families. Retrieved from https://alzheimer.ca/sites/default/files/documents/ambiguous-loss-and-grief_for-individuals-and-families.pdf

- Aminzadeh, F., Byszewski, A., Molnar, F. J., & Eisner, M. (2007). Emotional impact of dementia diagnosis: Exploring persons with dementia and caregivers’ perspectives. Aging & Mental Health, 11(3), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860600963695

- Arizmendi, B. J., & O’Connor, M.-F. (2015). What is “normal” in grief? Australian Critical Care: Official Journal of the Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses, 28(2), 58–62; quiz 63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2015.01.005

- Baloyannis, S. (2011). The philosophy of dementia. Journal of Neurology, 258(Suppl. 1), S190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-011-6026-9

- Bartlett, R., Windemuth-Wolfson, L., Oliver, K., & Dening, T. (2017). Suffering with dementia: The other side of “living well. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(2), 177–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161021600199X

- Berenbaum, R., Tziraki, C., & Cohen-Mansfield, J. (2017). The right to mourn in dementia: To tell or not to tell when someone dies in dementia day care. Death Studies, 41(6), 353–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2017.1284953

- Blandin, K., & Pepin, R. (2017). Dementia grief: A theoretical model of a unique grief experience [Article. ]Dementia (London, England), 16(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301215581081

- Bruce, E. J., & Schultz, C. L. (2001). Nonfinite loss and grief: A psychoeducational approach. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- Burke, M. L., Hainsworth, M. A., Eakes, G. G., & Lindgren, C. L. (1992). Current knowledge and research on chronic sorrow: A foundation for inquiry. Death Studies, 16(3), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481189208252572

- Chan, D., Livingston, G., Jones, L., & Sampson, E. L. (2013). Grief reactions in dementia carers: A systematic review [Article. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3795

- Crawley, S., Sampson, E. L., Moore, K. J., Kupeli, N., & West, E. (2023). Grief in family carers of people living with dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 35(9), 477–508. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610221002787

- Cronin, S., Keegan, O., Lynch, M., Delaney, S., McGuinness, B., & Dillon, A. (2016). Loss and grief in dementia. Palliative Medicine, 30(6), NP372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216316646056

- De Vries, K., & McChrystal, J. (2010). Using attachment theory to improve the care of people with dementia. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion, 3(3), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWOE.2010.032927

- Doka, K. (2010). Grief, multiple loss and dementia. Bereavement Care, 29(3), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02682621.2010.522374

- Doka, K. J., & Aber, R. (1989). Psychosocial loss and grief. Disenfranchised Grief: Recognizing Hidden Sorrow., 187–198.

- Doka, K. J., & Tucci, A. S. (2015). The longest loss: Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Hospice Foundation of America.

- Erwin, E. J., Brotherson, M. J., & Summers, J. A. (2011). Understanding qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and opportunities in early childhood intervention research. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(3), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815111425493

- Gataric, G., Kinsel, B., Currie, B. G., & Lawhorne, L. W. (2010). Reflections on the under-researched topic of grief in persons with dementia: A report from a symposium on grief and dementia. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 27(8), 567–574. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909110371315

- Gruetzner, H., Ellor, J. W., & Back, N. (2012). Identifiable Grief Responses in Persons With Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 8(2), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2012.685439

- Hainsworth, M. A. (1994). Living with multiple sclerosis: The experience of chronic sorrow. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing: Journal of the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, 26(4), 237–240. https://doi.org/10.1097/01376517-199408000-00008

- Harris, D. L. L. (2019). Non-death loss and grief: Context and clinical implications. In Non-death loss and grief: Context and clinical implications. Routledge.

- Harris, D. L., & Winokuer, H. R. (2019). Principles and practice of grief counseling. Springer publishing company.

- Hedman, R., Hansebo, G., Ternestedt, B.-M., Hellström, I., & Norberg, A. (2016). Expressed Sense of Self by People With Alzheimer’s Disease in a Support Group Interpreted in Terms of Agency and Communion. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 35(4), 421–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464814530804

- Holst, G., & Hallberg, I. R. (2003). Exploring the meaning of everyday life, for those suffering from dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 18(6), 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/153331750301800605

- Isaksson, A. K., Gunnarsson, L. G., & Ahlström, G. (2007). The presence and meaning of chronic sorrow in patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(11C), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01995.x

- Johansson, A. K., & Grimby, A. (2013). Grief Among Demented Elderly Individuals: A Pilot Study. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 30(5), 445–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909112457009

- Kelly, A. (2008a). Forgetting and the memory of forgetting: The material and symbolic role of memory in the intersubjective lives of people with AIDS dementia. Dementia, 7(4), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301208096629

- Kelly, A. (2008b). Living loss: An exploration of the internal space of liminality. [Article]Mortality, 13(4), 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576270802383915

- Lachal, J., Revah-Levy, A., Orri, M., & Moro, M. R. (2017). Metasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 269. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00269

- Liddle, J., Bennett, S., Shelley, A., Lie, D., Standen, B., & Pachana, N. A. (2013). The stages of driving cessation for people with dementia: Needs and challenges. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(12), 2033–2046. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610213001464

- Lindauer, A., & Harvath, T. A. (2014). Pre-death grief in the context of dementia caregiving: A concept analysis [Article. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(10), 2196–2207. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12411

- Lindgren, Burke, M. L., & Hainsworth, M. A. (1992). Chronic sorrow: A lifespan concept. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 6(1)

- Lindgren, C. L. (1996). Chronic Sorrow in Persons With Parkinson ‘ s and Their Spouses. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 10(4), 351–367.

- Lo, K.-C., Bricker-Katz, G., Ballard, K., & Piguet, O. (2022). The affective, behavioural, and cognitive reactions to a diagnosis of Primary Progressive Aphasia: A qualitative descriptive study. Dementia (London, England), 21(8), 2476–2498. (14713012) https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012221124315

- Long, H. A., French, D. P., & Brooks, J. M. (2020). Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences, 1(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2632084320947559

- Mayer, M. (2001). Chronic sorrow in caregiving spouses of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Aging and Identity, 6(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009528713329

- McAtackney, D., Gaspard, G., Sullivan, D., Bourque-Bearskin, L., Sebastian, M., Soc, G. H., & Authority, F. N. H. (2021). Improving Dementia Care for Gitxsan First Nations People. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 16(1), 118–145. https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v16i1.33225

- McCleary, L., Thompson, G. N., Venturato, L., Wickson-Griffiths, A., Hunter, P., Sussman, T., & Kaasalainen, S. (2018). Meaningful connections in dementia end of life care in long term care homes. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 307. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1882-9

- Milne, A. (2010). The “D” word: Reflections on the relationship between stigma, discrimination and dementia. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 19(3), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638231003728166

- Nordtug, B., Torvik, K., Brataas, H. V., Holen, A., & Knizek, B. L. (2018). Former work life and people with dementia. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 41(1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000191

- O’Connor, C. M. C., Liddle, J., O’Reilly, M., Meyer, C., Cartwright, J., Chisholm, M., Conway, E., Fielding, E., Fox, A., MacAndrew, M., Schnitker, L., Travers, C., Watson, K., While, C., & Bail, K. (2022). Advocating the rights of people with dementia to contribute to research: Considerations for researchers and ethics committees. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 41(2), 309–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.13023

- O’Connor, M., Tan, H., O’Connor, D., & Workman, B. (2013). Is the frequent death of residents in aged care facilities a significant cause of grief for residents with mild dementia? Progress in Palliative Care, 21(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743291X12Y.0000000031

- Olsson, A., Lampic, C., Skovdahl, K., & Annakarin, E. (2013). Persons with early-stage dementia reflect on being outdoors: A repeated interview study. Aging & Mental Health, 17(7), 793–800. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.801065

- Ostwald, S. K., Duggleby, W., & Hepburn, K. W. (2002). The stress of dementia: View from the inside. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 17(5), 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/153331750201700511

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Paananen, J., Rannikko, J., Harju, M., & Pirhonen, J. (2021). The impact of Covid-19-related distancing on the well-being of nursing home residents and their family members: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 3, 100031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100031

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pearce, A., Clare, L., & Pistrang, N. (2002). Managing sense of self: Coping in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia, 1(2), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/147130120200100205

- Rando, T. A. (1993). Treatment of complicated mourning. Research Press.

- Rando, T. A. (2000). Clinical dimensions of anticipatory mourning: Theory and practice in working with the dying, their loved ones, and their caregivers. Research Press.

- Rentz, C., Krikorian, R., & Keys, M. (2005). Grief and mourning from the perspective of the person with a dementing illness: Beginning the dialogue. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 50(3), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.2190/XBH0-0XR1-H2KA-H0JT

- Robinson, L., Clare, L., & Evans, K. (2005). Making sense of dementia and adjusting to loss: Psychological reactions to a diagnosis of dementia in couples. Aging & Mental Health, 9(4), 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860500114555

- Roos, S. (2002). Chronic sorrow: A living loss. Psychology Press.

- Sanford, S., Rapoport, M. J., Tuokko, H., Crizzle, A., Hatzifilalithis, S., Laberge, S., & Naglie, G. (2019). Independence, loss, and social identity: Perspectives on driving cessation and dementia. Dementia (London, England), 18(7-8), 2906–2924. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218762838

- Smith, R. C. (2021). Analytic autoethnography of familial and institutional social identity construction of My Dad with Alzheimer’s: In the emergency room with Erving Goffman and Oliver Sacks. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 277, 113894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113894

- Snyder, L., & Drego, R. (2006). Experiences of loss and methods of coping with loss for persons with mild-moderate Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly, 7(3), 152–162.

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046

- Tan, H. M., O’Connor, M. M., Howard, T., Workman, B., & O’Connor, D. W. (2013). Responding to the death of a resident in aged care facilities: Perspectives of staff and residents. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.), 34(1), 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2012.08.001

- The Irish Hospice Foundation. (2016). Guidance Document 3: Loss and Grief in Dementia.

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Watanabe, A., & Suwa, S. (2017). The mourning process of older people with dementia who lost their spouse. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(9), 2143–2155. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13286

- World Health Organisation. (2023). Dementia. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Wyatt, M., & Liggett, S. (2019). The Potential of Painting: Unlocking Disenfranchised Grief for People Living With Dementia. Illness Crisis and Loss, 27(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054137318780577

- Yale, R. (1999). Support groups and other services for individuals with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Generations, 23(3), 57–61.

Appendix

Search strategies

The following search terms were used in relation to dementia:

dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, posterior cortical atrophy, Benson’s syndrome, primary progressive aphasia, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Pick’s disease and major neurocognitive disorder

The following terms related to grief were used:

grief, grieving, mourning, sorrow, nonfinite loss and living loss

PRISMA 2020 Checklist

From: Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International journal of surgery, 88, 105906.