Abstract

Objectives: We describe our co-design process aimed at supporting the reintegration of essential care partners into long-term care homes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: More specifically, using a co-design process, we describe the pre-design, generative, and evaluative phases of developing a virtual infection prevention and control course for essential care partners at our partnering long-term care home. For the evaluative phase, we also provide an overview of our findings from interviews conducted with essential care partners on the expected barriers and facilitators associated with this virtual course.

Results: Results from these interviews indicated that the virtual course was viewed as comprehensive, detailed, engaging, refreshing, and reliable, and that its successful implementation would require appropriate resources and support to ensure its sustainability and sustainment. Findings from this study provide guidance for the post-design phase of our co-design process.

Conclusion: Our careful documentation of our co-design process also facilitates its replication for other technological interventions and in different healthcare settings. Limitations of the present study and implications for co-designing in the context of emergent public health emergencies are explored in the discussion.

Introduction

In Canadian long-term care (LTC) homes, unpaid caregivers (e.g. family members, health professions students, volunteers) often provide care to LTC residents as it relates to communication, feeding, mobility, and assistance in decision-making (Stall et al. Citation2020). This unpaid caregiving is considered significant for residents’ well-being (Perkins et al. Citation2013). However, it is noteworthy that support for unpaid caregivers received limited attention in Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Estabrooks et al. Citation2020; Hsu et al. Citation2020). Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, jurisdictional legislation supporting the role of unpaid caregivers in Canadian LTC homes was often absent, inconsistently applied, and lacked crisis procedures or preparation (Estabrooks et al. Citation2020; Keefe, Citation2011). In addition to the threat of COVID-19 infections and death, the adverse consequences of restricting access to congregate settings such as LTC homes, including increased loneliness and depression (Chu et al. Citation2020; Plagg et al. Citation2020), became a significant concern for resident well-being. This study employs the term ‘essential care partner’ (ECP) to describe a subcategory of unpaid caregivers, such as family members, whose support is indispensable for the LTC resident’s care. The term ECP not only reflects the terminology used by our partnering LTC home but also emphasizes that some unpaid caregivers are essential to the overall well-being of the resident in the LTC home, a concept that gained prominence during the pandemic (Fancott et al., Citation2021; Kemp, Citation2021). In alignment with policy recommendations from Healthcare Excellence Canada (Citation2020), we have developed a technological intervention designed to support ECPs in LTC homes during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Here, we describe our co-design process and present the results of our evaluative phase of the co-design process using implementation science methodologies.

Co-design

Co-design, defined as collective creativity applied throughout the entire design process, involves both designers and non-designers (Sanders & Stappers, Citation2008). Sanders and Stappers (Citation2014) outline four main phases of co-design: the pre-design phase, generative phase, evaluative phase, and post-design phase. The pre- and post-design phases aim to foster empathy across designers and non-designers. The pre-design phase is particularly important in preparing non-designers to participate in the co-design process. The generative phase is aimed at exploring the design space by asking what will be useful, usable, and desirable. Finally, the evaluative phase is aimed at identifying problems and assessing whether the co-design process resulted in something useful, usable, and desirable. In this study, we provide an overview of our application of this co-design process.

Implementation science

Implementation science can be described as utilizing the study of scientific methods to promote the systematic uptake of evidence-based research to improve the real-world uptake of clinical interventions and improve the quality of service (Eccles & Mittman, Citation2006). Thus, implementation science methodologies play a critical role in ensuring the successful implementation of clinical interventions, including technological interventions, to improve healthcare outcomes (Bauer & Kirchner, Citation2020; Gallant et al. Citation2023). The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CIFR; Damschroder et al. Citation2009, Citation2022), one of the most highly cited frameworks within the body of literature (Skolarus et al. Citation2017), is an example of a well-established implementation science framework. The CFIR outlines several constructs across the five overarching domains of innovation characteristics (e.g. evidence of strength, adaptability, relative advantage), outer setting (e.g. needs and resources of those served by the organization), inner setting (e.g. access to knowledge and information, relative priority), individuals (e.g. self-efficacy, knowledge and beliefs about innovation), and implementation process (e.g. planning, engaging and stakeholders). Using an implementation science framework such as the CFIR to evaluate the co-designed product is likely to enhance the intervention’s relevance and generalizability and assist researchers in identifying potential barriers prior to full implementation (Keith et al. Citation2017; Powell et al. Citation2017). Thus, the CFIR is used to guide the evaluative phase of our co-design process.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the research team primarily located in Saskatchewan and the LTC team in New Brunswick. In New Brunswick, just over 70 LTC homes are located throughout the province. All LTC homes in New Brunswick are privately owned, with most homes being owned by not-for-profit organizations and a minority of homes being owned by for-profit organizations. The LTC home we collaborated with is in Saint John, a small-sized metropolitan city, and is privately owned by a not-for-profit organization.

Participants

In the co-design process, the research team served as designers, whereas the LTC team functioned as non-designers. The LTC team was composed of two ECPs, two front-line staff, and a research and quality coordinator. The research team comprised a principal investigator, a research coordinator, and one or two research assistants. For the evaluative phase of the co-design process, a total of eight ECPs participated in semi-structured interviews.

Procedure for co-design process

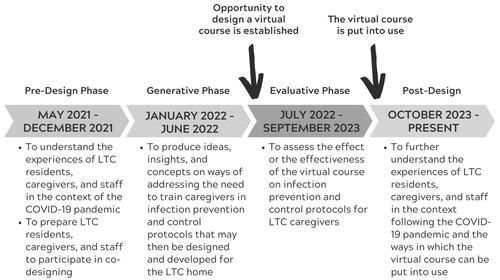

All communication between the research and the LTC team took place via email, telephone, and videoconferencing. As illustrated in , the co-design process for this study spanned a period of two and a half years (April 1, 2021—present). The pre-design phase took place from May 2021 to December 2021, followed by the generative phase from January 2022 to June 2022. The evaluative phase extended from July 2022 to September 2023, with the post-design phase commencing in October 2023. The opportunity to design the virtual course was established at the beginning of July 2022, and the virtual course was put into use in October 2023. Throughout the co-design process, we made concerted efforts to ensure that this process was truly collaborative in nature. We actively sought feedback and input from our LTC team throughout the co-design process by making sure that their needs and preferences were given top priority. In fact, the co-design process was inherently iterative featuring numerous feedback loops that worked to continually refine the virtual course. Finally, the co-design process required that the research team remained open to adapting and modifying the intervention as needed, actively engaging in all shared decision-making.

Figure 1. Application of Sanders and Stappers’ (Citation2014) revised framework for co-design to our virtual course.

Procedure for evaluative phase of co-design process

In the evaluative phase of the co-design process, we conducted semi-structured interviews with ECPs via Zoom for Healthcare (July 2022—August 2022). A semi-structured interview guide (Appendix A), informed by the CFIR, was developed to assess beliefs and expectations related to the proposed technological intervention. This component of our study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of New Brunswick (Saint John) (#2022-050), and all ECPs provided informed consent before taking part in the interview. Participants were also given a $15 gift card for participating in the interview. Participants were able to choose to receive a gift card from any national vendor and whether they wanted an electronic or physical gift card.

Analysis of the interviews was completed using directed content analysis with Crabtree and Miller’s (1999) template organizing style of interpretation (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) and the CFIR as a guiding framework for interpretation. To begin, a first coder (SA) categorized the narrative responses into thematic categories aligned with the CFIR-based code manual. This first coder identified pre-determined blocks of narrative responses to be coded by a second coder (NM). Once provided with the CFIR-based code manual, the second coder organized the predetermined blocks of narrative responses into thematic categories. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Results

In the sections that follow, we describe our approach to co-designing with our partnering LTC home. We use Sanders and Stappers’ (Citation2014) revised framework, supplemented with additional details about the evaluative phase, where we incorporate Damschroder et al.’s (Citation2009) CFIR. This comprehensive approach to the co-design process culminated in the development of a 5-module virtual infection prevention and control (IP + C) course designed for ECPs in LTC homes.

Pre-Design phase

illustrates the pre-design phase, which encompassed ongoing standing committee meetings, involving the LTC team, comprising two ECPs, two front-line staff, one research and quality coordinator, along with our research team, including one principal investigator, one research coordinator, and one research assistant. Our first meeting took place on May 26, 2021, over Zoom for Healthcare. For our first meeting, we provided our LTC team members with a document with an overview of our project (Appendix B) and answers to frequently asked questions (FAQs; Appendix C). An agenda was also prepared to outline the ways in which we hoped to guide the meeting. During our second meeting, which took place on June 23, 2021, we provided our LTC team members with a document with an overview of proposed intervention strategies (Appendix D) and proposed intervention strategies (Appendix E) along with an agenda. The third meeting, held on July 21, 2021, focused on the selection of two relevant intervention strategies: ‘Screening & IPAC’ and ‘Roles & Responsibilities of Caregivers’. Although the LTC team initially favoured and discussed ‘Roles & Responsibilities of Caregivers’ (Appendix F; Appendix G; Appendix H) on August 18, October 13, and November 24, 2021, subsequent discussions led to a shift in emphasis, with the LTC team highlighting the importance of the ‘Screening & IPAC’ intervention strategy for their LTC home.

Table 1. Overview of the pre-design phase.

Generative phase

With this changed emphasis in mind, we began our generative phase () by hosting our seventh standing committee meeting on January 12, 2022 to discuss the creation of a virtual IP + C course for ECPs associated with our partnering LTC home. In preparation for this meeting, we shared a document with the LTC team outlining our ideas for creating a virtual course that would cater to the needs of the LTC home (Appendix I). On February 23, 2022, we held our eighth meeting to further discuss these ideas before starting to work on the virtual course. During this meeting, our LTC team emphasized the importance of developing a virtual course that was self-paced with engaging learning materials, such as animations, videos, glossary terms, and quizzes. Prior to the ninth meeting (March 30, 2022), we drafted a script for the virtual course that was reviewed by the LTC team. This virtual course script was reviewed by the LTC team along with their IP + C coordinator, and their feedback and input were integrated into the drafted script. On April 27, 2022, we held our tenth meeting to determine the best approach to evaluate the intervention strategy in the coming months.

Table 2. Overview of the generative phase.

Evaluative phase

Following the tenth meeting, the evaluative phase began. For this phase, narrative responses from the semi-structured interviews with ECPs were categorized into themes based on the CFIR (Damschroder et al. Citation2009), which encompassed the aspects of innovation characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, and characteristics of individuals.

Innovation characteristics

The most important innovation characteristic for this study was adaptability, or the degree to which the course could be modified, tailored, or refined to fit the local context or needs, as interviews took place amid the rapid changes to IP + C protocols prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, one ECP recommended continuous updates of the virtual course to align with jurisdictionally mandated IP + C protocols. Another suggestion related to adaptability was the placement of posters, illustrating steps for various IP + C protocols (e.g. donning and doffing personal protective equipment [PPE]) to serve as reminders of the virtual course content. The virtual course was also seen as a safe alternative to in-person training during peak periods of respiratory illness (e.g. flu season). On the other hand, some participants felt that the virtual course was not a suitable option for some ECPs. For example, ECP 1 explained, ‘I know my sister-in-law is designated as my mom’s other ECP, and she would probably have a harder time logging on to something virtual to get the training’. A further recommendation with regards to adaptability was the option to conduct the virtual course within the LTC home where someone could assist the ECP as needed. ECP 7, for instance, expressed the need for in-person support within the LTC home for those less tech-savvy, stating, ‘I certainly think in person is much easier. I’m not very good with technology… I would expect that [the LTC home] would provide a setting, in the environment, whether it is a common area, or an auditorium, where they have the virtual course offered but where we would be able to sit and go through it with a facilitator or an instructor’.

Relative advantage referred to the intervention’s expected success compared to other interventions in current practice. Our interviews revealed that many ECPs felt positive about a virtual IP + C course compared to current practices (i.e. one in-person 2-h course offered by the LTC home each month). More specifically, ECPs appreciated the ability to complete the virtual course at their own pace without needing to wait for the next available in-person course offering. As ECP 3 explained, ‘The outline that you provided, although it is not greatly different from the outline that would’ve existed for the [in-person] program that I undertook for a couple of days, I understand [the virtual course] will be available whenever and wherever I wish to consult it. Now that’s a big advantage conceptually’. The ECPs’ responses indicated that the course had a relative advantage due to its greater accessibility. On the other hand, in comparison to current practices, a few of the ECPs felt that there was an advantage to having an in-person facilitator or moderator as they could ensure that IP + C skills are appropriately learned. For example, as ECP 2 stated, ‘It is nice to have a virtual course, but it’s always good to have somebody to back you up and say, ‘yeah, you did it correctly’. You can watch it online and figure out what you need to do, but the actual practice might have to have an observer look at what you do’. To address this quality assurance component, some ECPs recommended that the virtual course only be used as a refresher course or that an after-learning tool be added at the end of the virtual course to ensure the material was retained.

Another innovation characteristic of importance to the virtual course was the quality of its design. Although the course was still in its early stages at the time of the interviews, ECPs were provided with a brief overview of the planned virtual course, and most ECPs believed the virtual course to be of an interactive design that could offer abundant information regarding IP + C protocols while remaining user-friendly. ECPs felt that the design of the course would be insightful, detailed, and thorough. ECPs also noted their appreciation for the virtual course’s unique design elements (e.g. animations, quizzes).

Outer setting

Our analysis of the outer setting theme outlines a number of important characteristics regarding the needs and resources of the LTC home’s ECPs. More than half of the ECPs noted that the LTC staff were very accommodating, friendly, hands-on, and helpful in enforcing the jurisdictionally mandated IP + C protocols such as proper masking and hand washing. For example, ECP 4 expressed, ‘I think staff were very aware. Yes. Very aware. They were very hands on with the residents and were sanitizing more including little machines around the home, and more containers. They made it easy’. However, some ECPs expressed concerns about staff members providing care to their loved ones. Three ECPs felt that staff should exercise greater caution and be more proactive in implementing proper hygiene and health safety measures. ECP 5, for instance, stated, ‘Not at all. No one ever asked about the needs. I had to fight pretty hard to get a HEPA filter into my parents’ room. It would’ve been nice to have an option to say I'd like only vaccinated workers to deal with my parents, but it was never communicated to us that we could have that option’. Our results revealed a diversity of opinions among ECPs regarding their needs within the LTC home. While some ECPs believed that their needs were well addressed by the LTC staff, others highlighted the importance of raising awareness about the needs of both ECPs and the residents under their care.

Inner setting

With regards to the inner setting, networks and communication emerged as significant among ECPs. All ECPs indicated that the LTC home staff primarily utilized email for communication with ECPs and disseminated information through bulletin boards within the LTC home. Notably, none of the ECPs reported encountering any issues with these communication methods. When discussing ways of informing ECPs of the soon-to-be-developed virtual IP + C course, ECPs emphasized that these means of communication would also be effective to promote the virtual course to all ECPs.

Regarding the inner setting, the culture of the LTC home emerged as another significant theme. Six of the ECPs described the culture as active, excellent, and friendly despite the challenges brought on by COVID-19, such as short staffing, physical distancing, and social isolation. ECP 6 noted that the LTC staff ‘go above and beyond’. Only one ECP was displeased with the culture of the LTC home. As ECP 5 explained, ‘There’s no room for feedback. I don’t feel like there’s a real community of the ECPs. I don’t feel like there’s a partnership there. I find it an isolating place’. Furthermore, one ECP was unsure of the culture of the home since they were inactive within the LTC home.

In terms of the implementation climate, seven out of the eight interviewed ECPs expressed their lack of confidence that there would be substantial real-world adoption of the virtual IP + C course from ECPs if the course were not made mandatory. Even with this caveat in mind, the ECPs noted that the course would still be invaluable. For instance, ECP 8 explained, ‘I think that anything that enhances the work environment is going to help the facility. I think that it can only be positive. I don’t see that with that staff in there, I don’t see there being a negative side to this’.

In assessing the readiness to implement the virtual course, all ECPs concurred that LTC staff would offer support for the implementation of the virtual IP + C course and would actively disseminate information about the virtual course to ECPs. The participants perceived the relative priority of this course within the LTC home as ‘very high’ given that no program of its kind existed for the LTC home. ECPs felt that the program would remain an ongoing priority to fill the need for virtual programs to train ECPs in health practices that may impact the safety of residents. As ECP 6 explained, ‘I have no problem with [the virtual course] as long as I can see my father’.

Characteristics of individuals

The final theme under investigation pertained to the characteristics of individuals. Regarding knowledge and beliefs about the innovation, six out of the eight ECPs emphasized the importance of having a standardized set of practices for ECPs to follow. They expressed satisfaction with the concept of a virtual course designed to teach these practices to all ECPs, and the majority of ECPs believed that the virtual course would be beneficial, comprehensive, helpful, and essential in enhancing health and safety standards within the LTC home. For example, ECP 5 stated, ‘I think [the virtual training course] would be really good… it’s a lot more comforting to know if there’s a standard set of practices that every ECP that’s coming in is following… I think it would be beneficial’. However, two of the ECPs held a degree of scepticism about whether the virtual course would bring significant improvements to their LTC home. They expressed a need for more information on the virtual course’s success after it had been piloted.

Subsequently, with additional insights gained during these eight interviews, the research team proceeded to develop the virtual IP + C course. During this development stage, we maintained periodic steering committee meetings to ensure the LTC team remained informed about our progress (September 12, 2022; January 26, 2023; February 15, 2023). We drew inspiration from several virtual IP + C resources available to ECPs in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, our virtual IP + C course was influenced by open-source resources, such as the McMaster Infection Prevention and Control for Caregivers and Families Course, Public Health Ontario’s Routine Practices and Additional Precautions, and The Ottawa Hospital’s Essential Care Partner Education. In addition to these resources, we sought guidance from authoritative bodies like the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization. While these resources are available, they are not necessarily accessible as they are usually presented in text-based form and are not adapted for use within long-term care settings. Our development process also made use of variety of tools and resources, including web-based platforms (i.e. Thinkific, Wix), professional services (including a web developer from HopefulBuilder, a voice actor from Voices), and applications such as Adobe Stock, Canva, GIF Maker App, iPhone camera, VEED.io, and VideoScribe. For instance, we utilized VideoScribe to create engaging whiteboard animations aimed at enhancing audience engagement and improving material comprehension. As another example, Canva was used to create visually appealing and professional-looking design elements that were tailored to match our specific video content. Once the prototype for the virtual IP + C course was ready in March 2023, we then asked our LTC team to go through the virtual course so they could provide us with their feedback and input before the course became publicly available.

Post-design phase

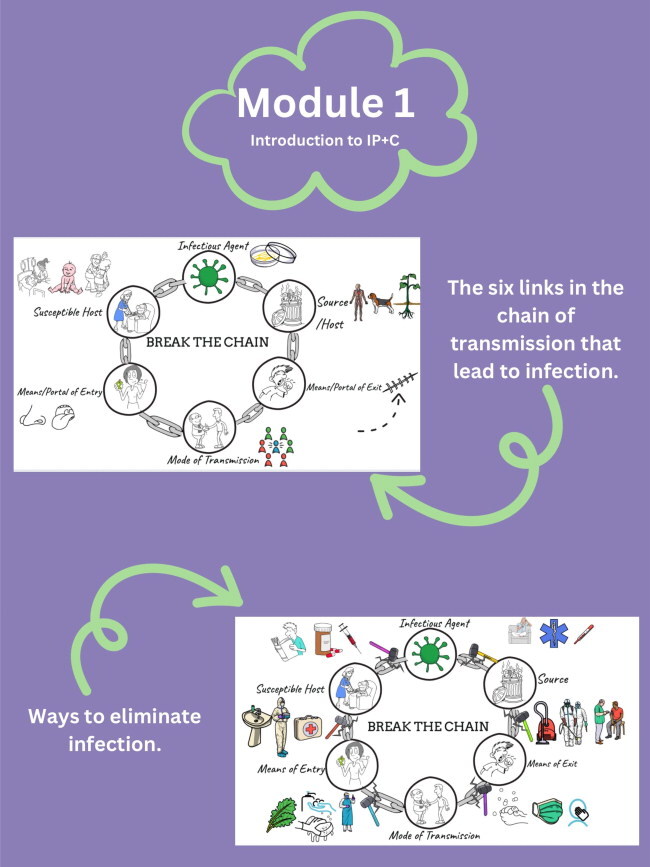

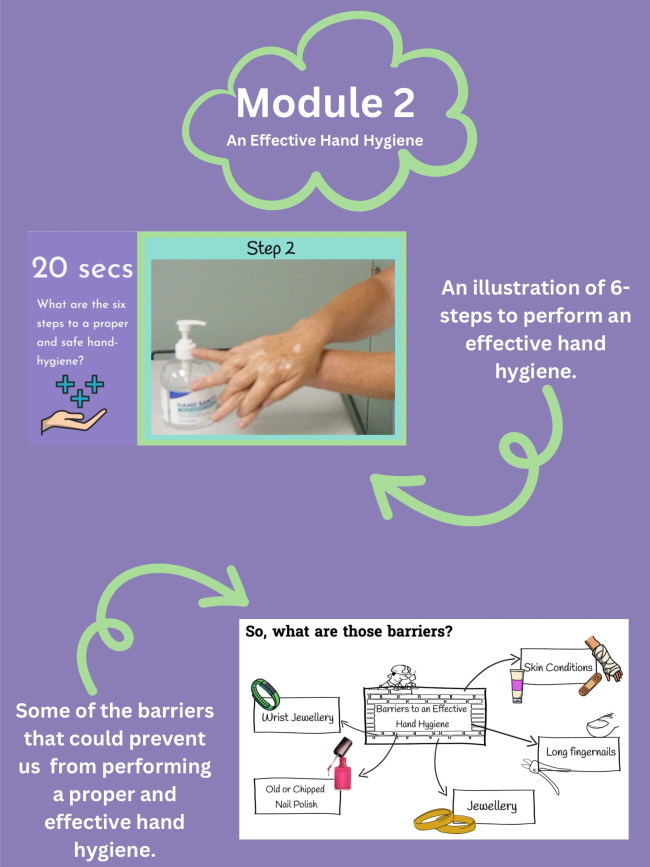

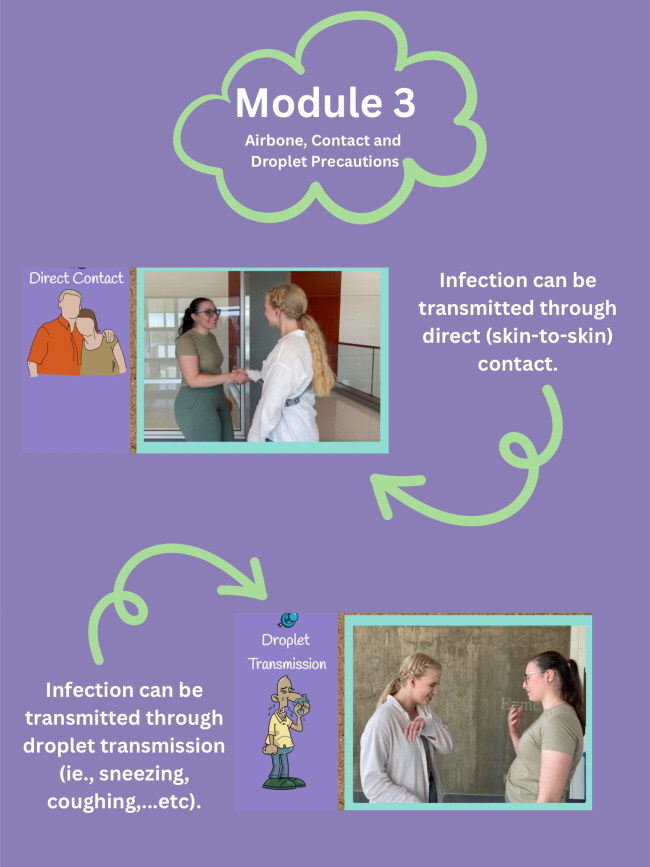

Finally, in October 2023, after integrating feedback and input from the LTC team, we entered the post-design phase as the virtual course became publicly available at www.longtermcareconnects.ca (Appendix J). This virtual course was divided into the following modules: (1) Introduction to Infection Prevention & Control and the Chain of Infection; (2) Effective Hand Hygiene; (3) Airborne Contact and Droplet Precautions; (4) Personal Protective Equipment; and (5) Roles and Responsibilities of ECPs. The first module emphasized the importance of IP + C in protecting oneself (i.e. ECPs) and care recipients (i.e. residents). The second module provided ECPs with the skills required to follow hand hygiene precautions. The third module covered additional precautions, including airborne, contact, and droplet precautions. The fourth module familiarized ECPs with the appropriate selection, application, removal, and disposal of PPE. In the fifth module, the roles and responsibilities of ECPs during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond were explored by highlighting the critical importance of maintaining a healthy environment and controlling infections. As we progress with the co-design process, the next steps in this study will involve further exploration of the lived experiences of ECPs and the ways in which we can successfully implement this virtual course into use in the partnering LTC home and other LTC homes across Canada.

Discussion

Our study presents an application of Sanders and Stappers’ (Citation2014, Citation2008) co-design process by involving a research team as designers and a LTC team as non-designers. The overarching purpose of the co-design process was aimed at reintegrating ECPs into LTC homes during the COVID-19 pandemic, but the way in which this purpose was achieved remained open to what the LTC team felt would be useful, usable, and desirable. That is, based on Healthcare Excellence Canada’s (2020) policy recommendations for the reintegration of ECPs into LTC homes, the LTC team was asked to identify the policy recommendation(s) most in line with their LTC home’s needs and preferences. Ultimately, by the end of the pre-design phase, the LTC home agreed to pursue an intervention to address the following Healthcare Excellence Canada (Citation2020) policy recommendation: ‘Ensure ECPs are informed about existing and updated infection prevention and control protocols’. The generative phase involved an exploration of potential solutions that could support this policy recommendation, including an in-person, hybrid, or virtual course aimed at educating ECPs about IP + C protocols.

At the end of the generative phase, the LTC team decided that the development of a virtual IP + C course for ECPs would best meet their needs and preferences. While this virtual course was developed within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virtual course offers an efficient method of training ECPs on IP + C protocols prior to entering the LTC home. Our intervention effectively addresses challenges that correspond with previous research findings presented by Hanna et al. (Citation2022), Ilesanmi et al. (Citation2021), and Low et al. (Citation2015). These studies demonstrate how the continuous implementation of IP + C policies and measures during the pandemic has altered daily care routines and heightened the workload for both nurses and personal care workers. Furthermore, the benefits of introducing an IP + C virtual course prior to entering healthcare facilities align with the recommendations of Veronica et al. (Citation2022), highlighting the importance of technology-mediated programs. Consequently, this virtual course has the potential to alleviate the burden on healthcare professionals, provide added support to direct care workers, and facilitate the efficient implementation of IP + C measures over time, thereby reducing the workload on personal care workers primarily responsible for direct care duties.

The efficiency of a virtual course is of particular importance given that LTC homes experience much influx and outflow of ECPs as current residents pass away and new residents are admitted. In fact, between 30% and 60% of LTC residents pass away within their first year of stay (Moore et al. Citation2020), and the average length of stay in LTC is about one to two years (Hoben et al. Citation2019; Kelly et al. Citation2010). Thus, the need for this virtual course is expected to extend beyond the COVID-19 pandemic as we look to the future in preparation for emergent health situations (Chief Public Health Officer [CPHO], 2023). Our results align with evidence from Iyamu et al. (Citation2023), which suggests that efforts to achieve public health goals, such as reducing infections, may fall short in meeting residents’ physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual needs. Moreover, it may not fully meet families’ expectations of care and can pose threats to staff members’ mental health and well-being. The continued isolation of residents from their family members contributes to these challenges in meeting residents’ needs. Therefore, it is crucial for this virtual course to extend beyond the COVID-19 pandemic to mitigate situations of isolation, loneliness, or separation from family members and loved ones.

Guided by the CFIR (Damschroder et al. Citation2022, Citation2009), the evaluative phase of the co-design process included interviews with ECPs to identify potential barriers and facilitators to the development, implementation, and evaluation of this virtual IP + C course for ECPs. For the most part, ECPs indicated that the virtual course would be useful, usable, and desirable with some noteworthy caveats regarding ECPs’ familiarity and comfort engaging with the virtual modality and the effectiveness of skills mastery through this virtual modality. To the extent possible, these caveats were addressed throughout the development of the virtual IP + C course for ECPs. The virtual course was developed in an iterative fashion, with various prototypes presented to the LTC team for feedback and input, to ensure that the virtual course was as useful, usable, and desirable as possible for the LTC home’s ECPs.

Based on interview findings, the need for additional components to support the virtual course will likely be needed for its successful implementation within this LTC home. With our recent transition from the evaluative to the post-design phase, the integration of findings from our interviews into our implementation plan and our further use of the CFIR to guide our implementation efforts will be invaluable. The main takeaway to be noted for future implementation of this virtual IP + C course is the consideration of factors which affect sustainability (i.e. continued delivery of intended benefit from the intervention over time after support is removed) and sustainment (i.e. continued enactment of processes, practices, and routines learned in the intervention). Furthermore, our co-design process was carefully documented with the preparation and distribution of agendas and related materials for each of our meetings with the LTC team. It is therefore hoped that this blueprint will allow for the replication of our co-design process for other technological interventions within LTC homes (e.g. pain behaviour monitoring; Gallant et al. Citation2023) and in other healthcare settings (e.g. hospitals).

Limitations and future directions

This study uniquely examined the use of Sanders and Stappers’ (Citation2014, Citation2008) co-design process in a partnering LTC home within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its related visitor restrictions, but we acknowledge that our study has important limitations. For example, ECPs who completed the interviews posed the researchers questions that they were unable to answer as the virtual course was still in development. The evaluative phase may therefore be better suited once a prototype of a technological intervention is ready and can be made available. In a similar manner, the research team also recognizes that the definitive version of the virtual IP + C course may differ from the description provided to participants at the time of the interviews. Nevertheless, the interview responses were helpful in ensuring that the final technological intervention addressed some of the questions or concerns that the ECPs identified in the interviews. Future studies could consider a more rapid and iterative approach to interviews in the co-design process so that non-designers can contribute at different stages of development to inform the ongoing process of development.

While our evaluative phase included interviews with ECPs, we did not conduct interviews with other LTC stakeholders such as managers, front-line staff, and residents. The decision to only interview ECPs was a collaborative one that accounted for the understaffing of LTC homes that was particularly noteworthy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, given that our interviews were conducted over Zoom, the inclusion of residents would have often necessitated staff involvement. While important insights were gained from interviewing ECPs regarding the intervention, future studies should conduct a more comprehensive evaluation that includes LTC managers, front-line staff, and residents along with ECPs. Moreover, our sample size of ECPs was quite small, and is unlikely to be representative of all ECPs in our partnering LTC home let al.one other LTC homes across Canada. The co-design process should therefore account for the organizational resources that might be needed to support the inclusion of all types of stakeholders to ensure that more varied perspectives are heard and that these voices are better integrated into the co-design process. Future research identifying better ways of engaging with varied LTC stakeholders, whether in person or virtually, would also facilitate better co-designing.

Another limitation of our study included project delays due to the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our innovation development, for example, was put on hold several times due to challenges of scheduling meetings with the LTC team when COVID-19 illness or outbreaks occurred. Despite these challenges, the research team’s adaptability was pivotal in supporting the continuous co-design process. In line with the CPHO’s (2023) most recent report, challenges related to emergent situations are expected to continue and that, in preparation for these emergent situations, we need to establish more resilient communities. Future research could therefore examine the factors that make more resilient LTC homes so that, in future emergent situations. According to the CPHO (Citation2023) report, we can expect COVID-like events to persist due to biological hazards and emergencies. The report underscores emergencies, regardless of their nature, can have enduring and far-reaching effects on both physical and mental health. For instance, wildfire smoke can lead to cancer, respiratory problems, and heart issues, while disease outbreaks can result in chronic conditions like post-COVID-19 syndrome. The psychological impact of emergencies can be severe and persistent, often extending beyond the immediate crisis and affecting individuals indirectly. For example, following events like the Lac-Mégantic train derailment and the Nova Scotia mass shooting, many people experienced post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Efforts to protect public health during emergencies, such as evacuations, present their own set of challenges, including family separation, disruption of cultural practices, and environmental strain. Indigenous communities have faced numerous emergencies, leading to evacuations and significant impacts on mental health and overall well-being. Research indicates that repeated exposure to emergencies increases the likelihood of adverse mental and physical health outcomes. Furthermore, emergencies can disrupt various factors that influence well-being, such as education, income, housing, food security, and healthcare access. For instance, flooding and wildfires can destroy homes, evacuations can disrupt employment, and public health measures like virtual education and reduced healthcare access can lead to consequences on health-related behaviors and an increase in issues like discrimination and violence. Therefore, the establishment of more resilient communities is essential.

Future research could therefore examine the factors that make more resilient LTC homes so that, in future emergent situations, a co-design process such as the one described here could be supported with fewer project delays and associated challenges. Finally, future research should consider applying the co-design process to various healthcare settings, including hospitals and home healthcare, to assess its effectiveness in enhancing caregiver training. Additionally, the co-design approach could be adapted to address emerging health crises beyond COVID-19.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bauer, M. S., & Kirchner, J. (2020). Implementation science: What is it and why should I care?. Psychiatry research, 283, 112376.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Chief Public Health Officer. (2023). Creating the conditions for resilient communities: A public health approach to emergencies. Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Chu, C. H., Donato-Woodger, S., & Dainton, C. J. (2020). Competing crises: COVID-19 countermeasures and social isolation among older adults in long-term care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(10), 2456–2459. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14467

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- Damschroder, L. J., Reardon, C. M., Widerquist, M. A. O., & Lower, J. (2022). The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implementation Science, 17(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0

- Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1

- Estabrooks, C. A., Straus, S. E., Flood, C. M., Keefe, J., Armstrong, P., Donner, G. J., Boscart, V., Ducharme, F., Silvius, J. L., & Wolfson, M. C. (2020). Restoring trust: COVID-19 and the future of long-term care in Canada. FACETS, 5(1), 651–691. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2020-0056

- Fancott, C., MacDonald, T., Neudorf, K., & Keresteci, M. (2021). Caregivers at the heart of reimagined long-term care delivery in Canada: beyond the pandemic. HealthcarePapers, 20(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpap.2021.26638

- Gallant, N. L., Hadjistavropoulos, T., Stopyn, R. J. N., & Feere, E. K. (2023). Integrating technology adoption models into implementation science methodologies: A mixed-methods pre-implementation study. The Gerontologist, 63(3), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac098

- Hanna, K., Giebel, C., Cannon, J., Shenton, J., Mason, S., Tetlow, H., Marlow, P., Rajagopal, M., & Gabbay, M. (2022). Working in a care home during the COVID-19 pandemic: How has the pandemic changed working practices? A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02822-0

- Healthcare Excellence Canada. (2020). Policy guidance for the reintegration of caregivers as ECPs.

- Hoben, M., Chamberlain, S., Gruneir, A., Knopp-Sihota, J., Sutherland, J., Poss, J., Doupe, M., Bergstrom, V., Norton, P., Schalm, C., McCarthy, K., Kashuba, K., Ackah, F., & Estabrooks, C. (2019). Nursing home length of stay in 3 Canadian health regions: Temporal trends, jurisdictional differences, and associated factors. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(9), 1121–1128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.144

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hsu, A. T., Lane, N. E., Sinha, S. K., Dunning, J., Dhuper, M., Kahiel, Z., & Sveistrup, H. (2020). Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on residents of Canada’s long-term care homes—ongoing challenges and policy responses. London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Ilesanmi, O. S., Afolabi, A. A., Akande, A., Raji, T., & Mohammed, A. (2021). Infection prevention and control during COVID-19 pandemic: Realities from health care workers in a north central state in Nigeria. Epidemiology and Infection, 149, e15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268821000017

- Iyamu, I., Plottel, L., Snow, M., Zhang, W., Havaei, F., Puyat, J., Sawatzky, R., & Salmon, A. (2023). Culture change in long-term care-post COVID-19: Adapting to a new reality using established ideas and systems. Canadian Journal on Aging = La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 42(2), 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980822000344

- Keefe, J. (2011). Supporting caregivers and caregiving in an aging Canada. Institute for Research on Public Policy.

- Keith, R. E., Crosson, J. C., O'Malley, A. S., Cromp, D., & Taylor, E. F. (2017). Using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: A rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implementation Science: IS, 12(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0550-7

- Kelly, A., Conell-Price, J., Covinsky, K., Cenzer, I. S., Chang, A., Boscardin, W. J., & Smith, A. K. (2010). Length of stay for older adults residing in nursing homes at the end of life. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(9), 1701–1706. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03005.x

- Kemp, C. L. (2021). # MoreThanAVisitor: Families as “essential” care partners during COVID-19. The Gerontologist, 61(2), 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa161

- Low, L. F., Fletcher, J., Goodenough, B., Jeon, Y. H., Etherton-Beer, C., MacAndrew, M., & Beattie, E. (2015). A systematic review of interventions to change staff care practices in order to improve resident outcomes in nursing homes. PloS one, 10(11), e0140711.

- Moore, D. C., Payne, S., Keegan, T., Van den Block, L., Deliens, L., Gambassi, G., Heikkila, R., Kijowska, V., Pasman, H. R., Pivodic, L., & Froggatt, K. (2020). Length of stay in long-term care facilities: A comparison of residents in six European countries. Results of the PACE cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 10(3), e033881. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033881

- Perkins, M. M., Ball, M. M., Kemp, C. L., & Hollingsworth, C. (2013). Social relations and resident health in assisted living: An application of the convoy model. The Gerontologist, 53(3), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns124

- Plagg, B., Engl, A., Piccoliori, G., & Eisendle, K. (2020). Prolonged social isolation of the elderly during COVID-19: Between benefit and damage. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 89, 104086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104086

- Powell, B. J., Beidas, R. S., Lewis, C. C., Aarons, G. A., McMillen, J. C., Proctor, E. K., & Mandell, D. S. (2017). Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 44(2), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6

- Sanders, E. B.-N., & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068

- Sanders, E. B.-N., & Stappers, P. J. (2014). Probes, toolkits, and prototypes: Three approaches to making in codesigning. CoDesign, 10(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2014.888183

- Skolarus, T. A., Lehmann, T., Tabak, R. G., Harris, J., Lecy, J., & Sales, A. E. (2017). Assessing citation networks for dissemination and implementation research frameworks. Implementation Science: IS, 12(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0628-2

- Stall, N. M., Johnstone, J., McGeer, A. J., Dhuper, M., Dunning, J., & Sinha, S. K. (2020). Finding the right balance: An evidence-informed guidance document to support the re-opening of Canadian nursing homes to family caregivers and visitors during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(10), 1365–1370.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.07.038

- Veronica, P. J., Brown, P. M., Tim, A., Tricarico, E., Farrow, R. A., Cardoso, A. C., & Elizabete, M. (2022). Eyes on the aliens: citizen science contributes to research, policy and management of biological invasions in Europe. NeoBiota, 78, 1–24.

Appendix a

Introduction

Good morning/afternoon/evening! I will be your interviewer today. I am here with you to discuss the caregiver intervention that is being introduced in your long-term care home.

Review of consent form

As an essential care partner, you were invited to participate in individual interviews to discuss your experience with caregiving in long-term care homes within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This individual interview will be completed over Zoom. The interview will also be video- and audio-recorded using Zoom, but these recordings will be treated in a professional and confidential manner.You were provided with the consent form a few days ago.Do you have any questions?If they seem unsure:Do you understand that all the information collected will be kept confidential and that the results will only be used for scientific objectives?Do you understand that your participation in this study is voluntary?

Ground rules

Before we get started, I have a few ground rules that I would like to let you know about.There are no “right-or-wrong” answers since positive and negative opinions are incredibly valuable to our discussion.Therefore, your honesty in answering these questions is helpful to our team.It is also helpful if you elaborate on your answers as much as possible so that we fully understand what you are trying to express.If you need a break at any time, please let me know so that we can pause the interview.If at any point you are uncomfortable with the question being asked, you can let me know that you would prefer to skip the question, and I will move on to the next question.

Demographics

Sometimes some of our demographic identities (e.g. age, gender, race) that we have can affect the way we feel or think about the things around us. If you feel that any of these factors are relevant to the questions that I will be asking you regarding the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs, please feel free to talk about it as I feel it would add a lot of value to our discussion.

Characteristics of individuals

Knowledge & beliefs about the intervention

What do you know about the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs or its implementation in the facility?

How do you feel about the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs being implemented in your facility or home? Have you heard about it?

Self-efficacy

How confident are you that the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs will increase other caregivers or your own understanding of your role as a caregiver?

Individual stage of Change

Are you prepared to take the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs?

Innovation characteristics

Evidence strength & quality

How do you think that the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs will work in your setting?

What kind of supporting information would you need about the effectiveness of the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs to get you on board?

Relative advantage

How does the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs compare to other similar existing programs or other alternatives in your facility or home?

What advantages or disadvantages does the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs have compared to existing programs or other alternatives in your facility or home?

Adaptability

Are there components of the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs that should be changed or altered so that the intervention works well in your setting?

Which components should be changed or altered?

Why should these changes or alterations be made?

Are there components of the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs that should not be changed or altered so that the intervention works well in your setting?

Which components should not be changed or altered?

Why should these changes or alterations not be made?

Outer setting

Patient needs and resources

To what extent are staff aware of the needs and preferences of ECPs during COVID-19?

To what extent were the needs and preferences of ECPs considered by your facility or home when deciding to implement the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs during COVID-19?

What barriers might you face in trying to participate in the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs during COVID-19 or other health crisis?

Inner setting

Networks & communications

How would you describe your working relationship with staff?

How would you typically find out about new initiatives or programs?

When you need to get something done or to solve a problem, who are your go-to people?

Culture

In general, how would you describe the culture of your facility or home?

With regards to residents’ needs and preferences, how would you describe the culture of your facility or home?

With regards to the role of ECPs, how would you describe the culture of your facility or home?

How do you think your facility or home’s culture will affect the implementation of the caregiver intervention?

Tension for Change

Is there a strong need for this Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs?

Why or why not?

Compatibility

How well does the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs fit with the values and norms within the facility or home?

How well does the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs fit with existing practices in your facility or home?

Relative priority

What kinds of high-priority initiatives or activities are already happening in the facility?

What is the priority of implementing the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs relative to other initiatives that are happening now?

Leadership engagement

What kind of support or actions can you expect from staff in your organization to help make the implementation of the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs successful?

Conclusion

Restatement of objective

As I mentioned at the beginning of the interview, the goal of this discussion was to hear from you and to know your thoughts about the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs that is being introduced in your long-term care home.

Final question and last call for statements and opinion

Are there any other general comments you would like to make about the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs and its implementation?

Closing salutations

Your participation is greatly appreciated. The experiences that you shared today will be very helpful in developing, evaluating, and implementing the Virtual IP + C Course for ECPs in your facility or home.

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix F

Appendix G

Appendix H

Appendix I

Appendix J