Abstract

COVID is having immediate and long-term impacts on the use of libraries. But these changes will probably not alter the importance of the academic library as a space. In the decade pre COVID libraries saw a growing number of visits, despite the increasing availability of material digitally. The first part of the article offers an analysis of the factors driving this growth, such as changing pedagogies, diversification in the student body, new technologies plus tighter estates management. Barriers to change such as academic staff readiness, cost, and slow decision making are also presented. Then, the main body of the article discusses emerging factors which are likely to further shape the use of library space, namely: concerns with student well-being; sustainability; equality, diversity and inclusion, and colonization; increasing co-design with students; and new technologies. A final model captures the inter-related factors shaping use and design of library space post COVID.

Introduction

One of the immediate effects of COVID in the UK in early 2020 was that face-to-face teaching ceased or was greatly reduced, so that libraries saw a very marked fall in visits. Many libraries were completely closed for a period. As lockdowns were released and campuses reopened social distancing rules meant there remained reduced capacity in library spaces. Fewer students were on campus. Staff were also spending much less time on campus. In many cases library visits had to be booked in advance. Thus, COVID had a major direct impact on one of the key things that academic libraries offer, a space to study.

COVID has probably had some longer-term direct effects. As a catalyst and an accelerator of existing trends (Breeding, Citation2020; Dempsey, Citation2020; Greenhall, Citation2020), particularly of the digital transformation, COVID seems to have increased acceptance of digital pedagogies by forcing many teaching staff to teach largely online for a period. This is likely to have the long-term effect of increasing the amount of digital learning universities do, with potential implications for how library space is used. With more confidence about digital delivery, on campus experience may become less critical. Certainly, library spaces will need to be able to support hybrid learning, where groups study together even though only some members are physically present. However, COVID does not seem to have caused a major shift towards distance learning.

Another important effect of COVID may be to reduce the amount that staff work on campus routinely. This could lead to a shift in the use of valuable campus space, with less use for staff offices (especially professional service staff). This could indirectly impact library use if other campus space is repurposed to create more informal or social learning spaces for students.

COVID will also have major indirect effects, though it is hard to judge these at the time of writing. For example, it may have economic impacts that, in turn, could affect the numbers and destinations of students. COVID has certainly accelerated the wider digital transformation in economy and society and so probably led to a greater need for the acquisition of digital skills as an outcome of study. This will impact universities via pressure to teach new types of skills, perhaps also accelerating shifts in pedagogy towards connectivist models. This might well touch the use of library space.

Yet it is interesting that in a 2020 US study library leaders stated that academic library space remained central to their plans post COVID (Frederick & Wolff-Eisenberg, Citation2020). A similar sentiment is expressed in a report from LIBER (2020: 19):

“Discussions on the hybrid and blended forms of future education as well as libraries. Space and Place are still very important as part of libraries, as well as the competencies of library staff. It’s the combination of digital and physical libraries that are the future.”

The purpose of this article is to analyse possible directions of change in the future use of physical library space post COVID, by summarising the underlying pre-COVID factors, by considering emerging trends that are not primarily COVID-related, and by reflecting on how these forces might be impacted by COVID. The article’s foundation is the author’s recent report for SCONUL which offers an analysis of trends primarily in the decade pre COVID (Cox and Benson Marshall, Citation2021). The literature-based discussion of emergent trends presented there has been significantly expanded for this article.

Long-term underlying factors shaping the use of space

The report for SCONUL “Drivers for the use of SCONUL libraries “sought to articulate why it is that use of physical library space grew rather than declined in the decade pre COVID, despite the increasing availability of digital content that can be accessed anywhere (Cox and Benson Marshall, Citation2021). The report was based on an international literature review combined with the re-analysis of unpublished usage data from a number of UK libraries. This article extends the literature review. The review does not purport to have been a systematic review, rather the purpose was a critical narrative review.

In exploring this question, one of the themes of the report was to draw attention to the relatively weak connections in the library literature about space to developments at the level of the wider campus. Very little of the library literature locates itself in the context of changing uses and design of the campus as a whole. Yet libraries are part of a learning landscape (Dugdale, Citation2009) or set of taskscapes for students that stretch beyond into the campus (and the wider city) (Asher et al., Citation2017) and this should be considered when we reflect on why students continue to use the library space intensively.

For example, it is interesting to consider how the library aligns to campus priorities as set out by authors such as Hajrasouliha (Citation2017) who analysed the main drivers in US campus plans (Reproduced in ).

Table 1. Main drivers identified in campus plans (after Hajrasouliha, Citation2017).

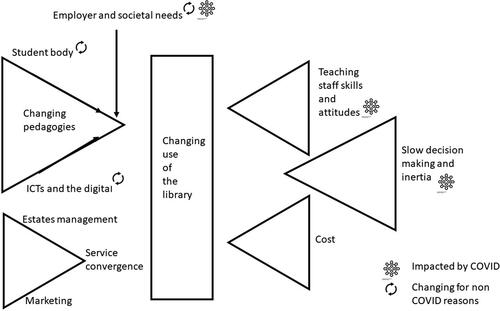

Building further on this wider literature, the report proposes a force field model (presented here, in an adapted form, as ) which seeks to capture the core underlying causes of change (and stability) in library space use and to explain the increasing number of library visits that is evident in library use data. In a forcefield diagram arrows represent drivers and barriers, with the size of the arrow representing the strength of the factor. Given the inter-relation of factors rather than separating some arrows out they have been combined with triangles here.

One cluster of factors identified is around changing pedagogies (Middleton, Citation2018). Pedagogies have shifted away from instructivism, with a stress on lectures to convey knowledge and exams to assess that knowledge. The emphasis has moved to constructivism, social constructionism and connectivism: implying respectively independent study where the student tries to make sense of ideas in the context of their prior knowledge, group learning and learning drawing on a rich range of resources, both informational and social. This shift has changed the kinds of spaces needed for learning (Beckers, van der Voordt, & Dewulf, Citation2015). Increasingly students want a greater variety of spaces including quiet spaces to study individually (or alongside others), flexible spaces for group work, and well-resourced spaces where they can connect to multiple learning resources. The library can supply all these types of space, in a way that other campus buildings rarely do.

Yet indicates that pedagogies have not simply changed autonomously. They have shifted because of the changing skillsets demanded by employment and society more generally. Society’s need is often for soft skills and life-long learning skills, both of which imply different pedagogies. The changes in pedagogies have also been driven by a more diverse student body, with more varied expectations and needs about how to study, compared to the traditional, 18-year-old, home undergraduate. The change has been enabled and partly driven by new technologies, such as social media, offering new models of communication. This cluster of factors is probably continuing to change, e.g., as the student population becomes even more diverse and driven by new waves of technologies (Cox, Citation2021). COVID has probably had an effect on this by accelerating the adoption of digital learning techniques.

A second cluster of factors shaping changing use of the library identified in the report relate more to the efficient management of the campus estate. An important factor is the increasing centralisation of control over campuses by professionalised estates teams driven by the need to control cost and reduce low occupancy rates. A major impact of this more intensive use of space is to push students away from using departmental space towards the library. Library space use has also been shaped by service convergence, involving libraries working more closely with other services. A final factor identified in this cluster is the context of marketing. Much investment in library buildings is because of their imageability. Investments in a landmark library building can contribute to the marketing of a whole university.

At the other side of the force field are three clusters of forces inhibiting change. Firstly, is the relative slow response of academics to fully adopt new pedagogies (and technologies). As we have seen COVID may have had an accelerating effect here. Furthermore, universities are simply rather slow changing institutions with traditional ways of doing things. A third factor is simply cost. A major constraint on changing spaces to reflect the latest pedagogies is the cost of making fundamental changes to buildings. Most campuses and libraries are a compromise based on trying to evolve a long established, rather inflexible campus infrastructure.

Building on this analysis, the reasons for growth in use of libraries as spaces in the decade before COVID could be summarised as follows (Cox and Benson Marshall, Citation2021):

Student numbers were growing

Students (particularly those from minority or low-income groups) had a need for somewhere that:

Contains a variety of types of space

Has a studious atmosphere

Is clean, quiet, light, comfortable, welcoming, and safe

Enables working alongside others and group work

Is convenient. Libraries’ central locations make them walkable from where students might be engaging in other activities.

Has desktop computers, as they are among the most popular resources in the library (more often mentioned than books), probably because:

Extended study is not convenient on a smartphone

Desktops in the library have specialist software and are linked to printers

Laptops are heavy so students are reluctant to bring them to campus

Not everyone has an up-to-date computer, a form of digital divide (revealed by COVID)

Has books because students continued to like reading printed books

Departmental space was being reduced or used more intensively, meaning that students had to go to the library to find study space.

Librarians have shown considerable enterprise in shaping space to student need e.g., via user experience (UX) studies, albeit there is less evidence of value being placed in services offered in the library, as opposed to the space (as a service) itself.

COVID may have impacted these factors, but probably at the margins. This suggests that on return to campus demand for study space will return. Indeed, lockdown reinforced awareness of a relative digital divide in access to technologies that the library helps to address through its provision of computers, printers etc.

A few changes may have happened. One partly hidden factor in prompting use of the library pre COVID was that a lot of content is still only available in printed form. This became more apparent in lockdown as libraries shifted to digital only purchasing policies. Libraries began to exert more pressure on publishers to make digital versions available. This could lead to an even larger proportion of content being online, eroding one factor for needing to come to the library. It is also possible that during lockdown there may have been a further growth in acceptance of reading online rather than printed books. This might also reduce the desire the come to the library. There have also been experiments to run sessions where students can work alongside others virtually, this may continue to have some value and reproduce some of this experience that is highly valued in the physical library.

There might also be a COVID impact via the release of space from use of staff offices, with increasing recognition from the pandemic experience that professional service staff in particular (including library staff) often do not need to work in the office five days a week. This could free up space to be repurposed for other uses, such as more informal and social learning spaces for students.

However, it is difficult to see that the basic drivers for coming to the library have changed much, assuming student numbers are sustained.

Emerging factors

Building on this analysis, this section considers a number of other, emerging factors shaping use and design of library space.

Well-being and mental health concerns

The role of the library in supporting student (and staff) well-being and mental health is a relatively new concern. There was an earlier body of literature on library anxiety focussing on how some students (often high performing ones) feel worried trying to use a library (Jiao & Onwuegbuzie, Citation1999). This relates to ways the library itself impacts student well-being. A few other authors have seen libraries in general as promoting belonging, even potentially as therapeutic landscapes (Brewster, Citation2014) or contemplative spaces (Pyati, Citation2019). But mental health up to a few years ago was rarely more than an implicit focus in the study of library use and design.

Now a wider agenda promoting a whole university approach to mental health suggests that all parts of the university should be contributing to student mental health and wellbeing and libraries have taken up this challenge rather enthusiastically (Bladek, Citation2021; Cox & Brewster, Citation2020). Libraries have been refashioning library space in alignment to this agenda, by:

Creating new types of space where students can de-stress and relax or to house Cognitive Behaviour Therapy texts and/or fiction collections.

Simply making all study spaces more pleasant for working in, e.g. by bringing more natural light into study areas.

Creating areas for napping (Wise, Citation2018).

Finding ways to encourage students to move about more, even take exercise on the basis of physical health and mental health being linked (Clement et al., Citation2018; Lenstra, Citation2020).

Creating areas to turn off phones and other technologies, to enhance digital well-being.

Hosting of Nonlibrary well-being events in the library space, including animal petting.

These may not constitute major changes to library space, but COVID has intensified the concerns with student well-being, so it is likely to remain a factor in thinking about how libraries are designed for use.

Sustainability

The sustainability agenda is another important but evolving influence on library use and design. In earlier work the focus was on ensuring that new buildings were built to environmentally friendly standards, as “green libraries” (Antonelli, Citation2008). Increasingly it would be recognised that there is a need to think through how issues of environmental impact apply to all aspects of on-going library operations as much as buildings themselves (Aulisio, Citation2013; Jankowska & Marcum, Citation2010). A neglected aspect of this is that the digital is not itself without environmental impact, because of the energy, raw materials, and human labour it relies on (Lucivero, Citation2020; Obringer et al., Citation2021).

Another strand that might be considered alongside this is the movement for aesthetics of space that reference the natural world: biophilia. Some authors greatly expand the meaning of this beyond direct incorporation of nature into the built environment to the use of natural forms, patterns and materials (Gierbienis, Citation2019; Kellert, Citation2013). They also attribute the attractions of the biophiliac aesthetic to innate human preferences. Certainly campus landscape can contribute to mental well-being (Scholl & Betrabet Gulwadi, Citation2015).

But a more significant change is the way that the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals effectively shift the sustainability agenda beyond environmental issues to a broader focus on social justice in development. In this vision social inequality is seen as inherently unsustainable (Sahavirta, Citation2018). This intensifies the political dimension of sustainability in ways that could impact how library space is designed and used. There is an important link to the decolonising agenda here.

Sustainability will be important in the future partly because it is an increasing concern that students have, influencing their choice of institution and their response to library designs. Demonstrating the sustainability of all aspects of the library including library space to users is likely to be increasingly important. COVID has not dislodged the urgency of the sustainability agenda.

Equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI), and decolonisation

Like the sustainability agenda, issues of EDI impacting use and design of library space have also evolved. There is an increasing understanding that how students experience campus, including the library space, is diverse and it cannot be taken for granted how spatial designs are experienced. This has important implications for design of library space to promote a sense of belonging and is perhaps the most challenging and complex emerging factor shaping library design. Given this, the current section presents a longer discussion of this trend compared to the other factors.

Studies of campus have recognised for a while, as an aspect of there being a “hidden curriculum” partly created by buildings and how they are decorated, that space can alienate some potential students, such as those from working class backgrounds (Costello, Citation2002; Gair & Mullins, Citation2002; Tor, Citation2015). Such work has found that some campus spaces in how they were designed and furnished implicitly project cultural assumptions that are alienating for working class students, for example. In this context research has emphasised the value that is placed on the library particularly by minority and low income groups if it is not experienced in this way (Soria, Citation2013).

The significance of the campus climate for experiences of sexual and gender identities is being increasingly discussed. Much previous research suggests that campus climate remains somewhat hostile for LGBTQ + students who experience discrimination and verbal abuse, mostly from other students, usually in places such as students unions or halls of residence (Ellis, Citation2009). Generally, LGBTQ + students report that they feel safe on campus, but they do feel obliged in certain places to mask expressions of their identity to ensure this. Ambivalent feelings are expressed through the idea of students feeling “safe but unsafe”—because of contradictions in implicit messaging. For example, while the university may dot the campus with posters against discrimination it may still perpetuate discriminatory assumptions e.g., through the lack of gender neutral toilets (Allen, Cowie, & Fenaughty, Citation2020). In some studies LGBTQ + students also felt invisible in a bad way (because their community was not acknowledged in official representations) but also visible in a bad way (because vulnerable to microaggression). In this campus context, libraries are often seen as a quiet, safe space which is particularly valued. It is also seen as a place to find out information safely about LGBTQ + issues, though there is always room for improvement in terms of offering access to such information (Stewart & Kendrick, Citation2019; Wexelbaum, Citation2018).

How forms of physical and cognitive abilities might shape experiences of space are also gaining growing attention. What appears to be a “neutral” design to a non-disabled person can be experienced very differently by those with some form of disability. Library lighting, acoustics, cleanliness and signage can all have a strong impact on experience of those with certain disabilities (Pionke, Citation2017). People with disabilities appear to want quiet spaces to study, lockers and easier physical access (Pionke, Citation2017). It is symbolic of marginalisation if disabled access is via a side entrance rather than with everyone else. The very location of the library in itself can be significant in shaping its accessibility (Pontoriero & Zippo-Mazur, Citation2019).

Perceptions of disability are changing with a widening sense of disability beyond visible, physical issues, requiring ramps and lifts, to also cognitive and other differences. For example, people on the autistic spectrum, itself very various, might have very different sensory experiences of spaces (Andrews, Citation2016; Shea & Derry, Citation2019). Yet such disability is invisible (Andrews, Citation2016). To be welcoming the library space has to respond to all these differences and seek to accommodate them.

Libraries (especially public libraries) do have a tradition of seeking to be inclusive (Jaeger, Citation2018), but underlying understanding of the issues has shifted (Hamraie, Citation2016). In earlier thought disability tended to be treated as an individual problem that needed a cure or rehabilitation. From the 1980s the social model of disability came to see the issue as of discrimination caused by inaccessibility of the built environment, rather than the result of an inherent impairment of an individual. Universal design, which originated in this movement, is seen by some commentators as offering principles that can produce designs offering better accessibility. However, critical disability theory takes a further move forwards in seeing differing abilities as having their own value as a way of experiencing the world rather than something to be cured or rehabilitated. In this view universal design is unhelpful in tending to decentre disability and through its focus on technical issues rather than acknowledging that discrimination is created through power. Such thinking challenges design based on a norm of a student who is young, white, and not disabled.

The dimension of such diversity that has arguably strengthened in importance most in the last few years, seemingly accelerated during COVID, are the issues around ethnicity. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement has resonated with existing calls to decolonise the curriculum. Whereas earlier studies suggested that the campus, and the library in particular, were seen by Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) students as somewhat of a safe space (Whitmire et al., Citation2011), feelings may be shifting, because of growing self-awareness and a stronger willingness to confront all forms of discrimination.

The implications for library space are potentially very challenging (Beilin, Citation2017; Brook, Ellenwood, & Lazzaro, Citation2015). The analysis points to the way that seemingly minor aspects of décor such as references to benefactors can be micro-aggressions (Brook et al., Citation2015). Décor can project libraries as spaces where white is the norm (Santamaria, Citation2020). Students can feel alienated if they do not see people like themselves or their culture represented (Broughton, Citation2019; Harwood, Mendenhall, Lee, Riopelle, & Huntt, Citation2018). Campus spaces occupied by people behaving in typical, “white” student ways are experienced as uncomfortable (Broughton, Citation2019; Harwood et al., Citation2018). This desire to see people like themselves applies equally to the library staff they see, which is a problem for a profession that remains largely white (Hall et al., Citation2015). Indeed, taken to its logical conclusion, decolonisation challenges not only the colonial resonances of western architectural conventions, often used in library buildings, but the very idea of the library because it privileges knowledge in textual form over other forms of knowledge. It is certainly a challenge to the way that library collections privilege literature representing western epistemic traditions, rather than celebrating the plurality of global knowledges. It challenges classification schemes that reproduce racist (as well as heteronormative, homophobic and ableist) assumptions.

Collectively these trends prompt libraries to engage with the diversity of experiences of library space within the wider campus.

The campus is often seen as safer than the wider environment, and to contain truly safe, “counter spaces”, but can also feel like “contradictory space” because of conflicting messages and to contain spaces that are very white (heteronormative, ableist) “fortified spaces” (Harwood et al., Citation2018). Libraries have often been seen as potential counter spaces, but we must increasingly recognise limits on this. The fond belief that the library is a “neutral” space, may disguise that it is only neutral from a privileged, white, male global north perspective. In understanding how to better achieve inclusive spaces it is important to recognise that the needs of working class, differing sexual and gender identities, functional diversity and ethnicity may not all push in the same direction. Experiences within these groups is also varied. Yet the power of intersectionality to pile multiple forms of discrimination against certain individuals has also to be understood.

Co-design with students

The increasing use of UX methods in the study of use of library space reflects a stronger professional desire to engage with student experience. This may not go far enough in including students in decision making. Indeed, use of UX methods have recently been critiqued as making white, male, heteronormative assumptions (Hicks, Nicholson, & Seale, Citation2022). As Pionke (Citation2017) comments those with disability have been rarely actually consulted during library design processes. However, recent articles suggest that participatory or co-design of space with students is an increasing trend which could correct these biases (Cerdan Chiscano, Citation2021; Decker, Citation2020; Salisbury, Dollinger, & Vanderlelie, Citation2020). This resonates with the need to represent different minoritized groups discussed in the previous section because the complexity of issues surfacing in their experiences demands close cooperation with students themselves to understand their perceptions. Similarly, student investment in issues such as sustainability point to the value of including their views in the design process (Afacan, Citation2017).

New technology—internet of things, data and artificial intelligence, immersive tech

Technology is often portrayed as the key driver of library change. This narrative can be critiqued as representing a technological solutionist perspective that tends to embody white, heteronormative assumptions (Mirza & Seale, Citation2017). So, narratives of inevitable, technology driven change should be questioned. Yet there is no shortage of literature predicting the impact of technology on space use in campus contexts. Notably, smart technologies that use big data and Artificial Intelligence have the potential to monitor, predict and even reshape use and movement in library space. Data on space and movement can:

Assist in wayfinding

Give information about free study spaces or predict when is the best time to come to the library

Nudge students to change behaviours, e.g. to move more through messages or incentives (JISC, Citation2018)

These possibilities are being explored extensively in the smart campus/smart city literature, where libraries are seen as one of the many sites of application (Min-Allah & Alrashed, Citation2020). However, there is surprisingly little library specific literature on this topic (Hoy, Citation2016; Schöpfel, Citation2018). This might be because the focus of application is on the scale of campus and city level developments and perhaps on more infrastructural issues such as lighting and heating savings rather than direct services to students. It might also reflect library professional concerns about the ethical implications of using the technologies in terms of privacy, consent and (in the case of nudging) human agency. These raise serious questions that have been mostly fully explored to date in the literature on learning analytics (Jones et al., Citation2020). Such ethical issues are not the only barrier to the smart campus: other significant obstacles are legacy systems, interoperability between systems, skills shortages, and organisational culture issues. Nevertheless, there seems a strong movement among estates managers to explore the benefits of smart technologies, in ways that may impact libraries as spaces.

COVID has certainly accelerated the shift towards focus on value of data, but because learning has been online this relates more to data about online behaviours than applications shaping spatial use. Where COVID might accelerate technology adoption is in immersive technologies, given the context of social distancing and more momentum for pushing the boundaries with distance learning. Greater use would be driven by distant learning or, perhaps more likely, hybrid learning with a class which is a mix of face to face and distance learners. This reinforces our sense that experiences of space cannot really be separated from digital experiences (Gourlay & Oliver, Citation2018).

Discussion

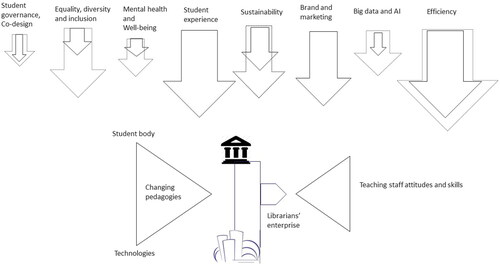

, an expansion and revision of , seeks to summarise some of the factors that are shaping the changing use of library space, and which have been discussed in the article. The size of arrows is intended to suggest the relative importance of the factor and the arrows drawn with dotted lines indicate factors that seem likely to grow in importance in the next decade.

As in key driver is changing pedagogies, linked to a diversifying student body, and enabled by new technologies. Even more emphasis is given to this in the current figure. Librarians’ enterprise in responding to these demands was not acknowledged in the previous model but is now represented. This has surely been a significant factor. Inhibiting change directly are the attitudes and skills of academic staff in applying new pedagogies. But a range of wider factors discussed in the article are also shaping change. These are represented as arrows across the top of the figure and bearing down on central dynamic. As in the previous figure the larger the arrow the more important the factor. The lighter coloured arrows represent the suggestion that some factors are growing in strength.

Listing them in order of importance they would be:

Efficiency—the need to use expensive campus space more intensively and cut costs

Student experience—a desire to maximise belonging and positive learning and life experiences

Brand and marketing—the use of buildings in creating images for marketing purposes

EDI—this and the following factors are discussed in the previous section

Sustainability

Big data and AI

Mental health and well-being

Student governance and co-design

It is evolving pedagogies that is the primary force for change, but efficiency, student experience and branding seem to be likely to remain dominant other factors. EDI and sustainability are emerging as major factors too if they are not already done so.

Emerging factors should also be recognised as interacting with each other. Smart technologies offer sustainability, at least in the narrow sense of energy saving. Big data could also potentially be used to monitor and impact student wellbeing. However, more technology might be in tension with the aesthetics of biophilia, because technology is often seen as the antithesis of the natural. It could also be seen as in tension with EDI because of the strong concerns about the ethics and bias in AI and a digital divide in access.

COVID has had a dramatic immediate impact on library use. It may have longer term impacts on academic staff attitudes and skills in using online learning. But it would probably be true to say it will not have made a fundamental impact on dominant pedagogies. A greater impact may arise through it prompting a reappraisal of the need for staff to work on campus, leading to the repurposing of more parts of the campus for student informal and social study. It seems to also have stimulated a wave of concern around BLM that may also shift approaches to library design.

Conclusion

This article has sought to offer a holistic review of the factors shaping use and design of library space that will be operating in the post COVID period. It has given emphasis to thinking about the library in the context of wider campus trends rather than seeing library specific factors as predominating. It has summarised the key factors that drove a growth of use of libraries in the decade pre COVID and considered how these might be impacted by the pandemic. It has then identified some strongly emerging trends concerns with student well-being; sustainability; equality, diversity and inclusion, and decolonisation; increasing co-design with students; and new technologies. It has reflected on how these factors may interact with each other and be impacted by COVID.

The underlying drivers for library use seem to remain strong. Although COVID may have accelerated experiment with digital learning, this may have also reinforced the ongoing value of face-to-face teaching and the campus experience. The most dynamic area of concern arises from t the diversity of student experience, especially of minoritized groups, and how this might affect the perception of the library as a neutral space. Given the white character of the profession this is a significant future challenge.

References

- Afacan, Y. (2017). Sustainable library buildings: Green design needs and interior architecture students' ideas for special collection rooms. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(5), 375–383. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2017.07.002

- Allen, L., Cowie, L., & Fenaughty, J. (2020). Safe but not safe: LGBTTIQA + students’ experiences of a university campus. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(6), 1075–1090. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1706453

- Andrews, P. (2016). User experience beyond ramps. In A. Priestner & M. Borg (Eds.), User experience in libraries (pp. 108–120). London: Facet Publishing. doi:10.4324/9781315548609

- Antonelli, M. (2008). The Green Library movement: An overview and beyond. Electronic Green Journal, 1(27). doi:10.5070/G312710757

- Asher, A., Amaral, J., Couture, J., Fister, B., Lanclos, D., Lowe, M. S., … Smale, M. A. (2017). Mapping student days: collaborative ethnography and the student experience. Collaborative Librarianship, 9(4), 293–317.

- Aulisio, G. J. (2013). Green libraries are more than just buildings. Electronic Green Journal, 1(35). doi:10.5070/G313514058

- Beckers, R., van der Voordt, T., & Dewulf, G. (2015). Aligning corporate real estate with the corporate strategies of higher education institutions. Facilities, 33(13/14), 775–793. doi:10.1108/F-04-2014-0035

- Beilin, I. G. (2017). The academic research library’s white past and present. In G. Schlesselman-Tarango (Ed.), Topographies of whiteness: mapping whiteness in library and information science (pp. 77–96). Sacramento CA: Library Juice Press.

- Bladek, M. (2021). Student well-being matters: Academic library support for the whole student. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(3), 102349. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102349

- Breeding, M. (2020). The systems librarian the stark reality of COVID-19’s impact on libraries: technology for the new normal. Computers in Libraries, September, 9–10.

- Brewster, L. (2014). The public library as therapeutic landscape: A qualitative case study. Health & Place, 26, 94–99. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.12.015

- Brook, F., Ellenwood, D., & Lazzaro, A. E. (2015). In pursuit of antiracist social justice: Denaturalizing whiteness in the academic library. Library Trends, 64(2), 246–284. doi:10.1353/lib.2015.0048

- Broughton, K. M. (2019). Belonging, intentionality, and study space for minoritized and privileged students. Cleveland, OH: Association of College & Research Libraries Conference.

- Cerdan Chiscano, M. (2021). Giving a voice to students with disabilities to design library experiences: an ethnographic study. Societies, 11(2), 61. doi:10.3390/soc11020061

- Clement, K. A., Carr, S., Johnson, L., Carter, A., Dosch, B. R., Kaufman, J., … Walker, T. (2018). Reading, writing, and… running? Assessing active space in libraries. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 19(3), 166–175. doi:10.1108/PMM-03-2018-0011

- Costello, C. Y. (2002). Schooled by the classroom: The (re) production of social stratification in professional school settings. In E. Margolis (Ed.), The hidden curriculum in higher education (pp. 53–70). London: Routledge.

- Cox, A., & Brewster, L. (2020). Library support for student mental health and well-being in the UK: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(6), 102256. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102256

- Cox, A. M., & Benson Marshall, M. (2021). Drivers for the usage of SCONUL member libraries. SCONUL https://www.sconul.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Drivers_for_the_Usage_of_SCONUL_Member_Libraries.pdf

- Cox, J. (2021). The higher education environment driving academic library strategy: A political, economic, social and technological (PEST) analysis. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(1), 102219. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102219

- Decker, E. N. (2020). Engaging students in academic library design: emergent practices in co-design. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 26(2-4), 231–242. doi:10.1080/13614533.2020.1761409

- Dempsey, L. (2020). Collection directions accelerated? Pandemic effects. https://blog.oclc.org/lorcand/collection-directions-accelerated/.

- Dugdale, S. (2009). Space strategies for the new learning landscape. Educause Review, 44(2), 50–52.

- Ellis, S. J. (2009). Diversity and inclusivity at university: A survey of the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) students in the UK. Higher Education, 57(6), 723–739. doi:10.1007/s10734-008-9172-y

- Frederick, J. K., & Wolff-Eisenberg, C. (2020). Academic library strategy and budgeting during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the Ithaka S + R US library survey 2020. https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/academic-library-strategy-and-budgeting-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

- Gair, M., & Mullins, G. (2002). Hiding in plain sight. In The hidden curriculum in higher education (pp. 31–52). London: Routledge.

- Gierbienis, M. (2019). Applications of biophilic design in contemporary library architecture. In 19th International Mulitidisciplinary Scuebtific GeoConference SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 30 June - 6 July, 2019 (pp. 365–377). doi:10.5593/sgem2019/6.2

- Gourlay, L., & Oliver, M. (2018). Student engagement in the digital university: Sociomaterial assemblages. London: Routledge.

- Greenhall, M. (2020). Covid-19 and the digital shift in action. https://www.rluk.ac.uk/covid-19-and-the-digital-shift-in-action/.

- Hajrasouliha, A. H. (2017). Master-planning the American campus: Goals, actions, and design strategies. URBAN DESIGN International, 22(4), 363–381. doi:10.1057/s41289-017-0044-x

- Hall, H., Irving, C., Ryan, B., Raeside, R., Dutton, M., & Chen, T. (2015). A study of the UK information workforce. UK: CILIP/ARA.

- Hamraie, A. (2016). Universal design and the problem of “post-disability” ideology. Design and Culture, 8(3), 285–309. doi:10.1080/17547075.2016.1218714

- Harwood, S. A., Mendenhall, R., Lee, S. S., Riopelle, C., & Huntt, M. B. (2018). Everyday racism in integrated spaces: mapping the experiences of students of color at a diversifying predominantly white institution. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(5), 1245–1259. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1419122

- Hicks, A., Nicholson, K. P., & Seale, M. (2022). Towards a critical turn in library UX. College and Research Libraries, 83(1), 355. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/fimspubhttps://ir.lib.uwo.ca/fimspub/355.

- Hoy, M. B. (2016). Smart buildings: An introduction to the library of the future. Medical Reference Services Quaterly, 35(3), 326–331. doi:10.1080/02763869.2016.1189787

- Jaeger, P. T. (2018). Designing for diversity and designing for disability: New opportunities for libraries to expand their support and advocacy for people with disabilities. The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion (IJIDI), 2(1/2), 52–66. doi:10.33137/ijidi.v2i1/2.32211

- Jankowska, M. A., & Marcum, J. W. (2010). Sustainability challenge for academic libraries: Planning for the future. College & Research Libraries, 71(2), 160–170. doi:10.5860/0710160

- Jiao, Q.G., & Onwuegbuzie, A.J. (1999). Is library anxiety important? Library Review, 48 (6), 278–282. doi:10.1108/00242539910283732

- JISC. (2018). Guide to the intelligent campus: Using data to make smarter use of your university or college estate. https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/6882/1/Intelligent_Campus_Guide.pdf.

- Jones, K. M. L., Briney, K. A., Goben, A., Salo, D., Asher, A., & Perry, M. R. (2020). A comprehensive primer to library learning analytics practices, initiatives, and privacy issues. College and Research Libraries, 81(3), 570–591. doi:10.5860/crl.81.3.570

- Kellert, S. (2013). 4 Dimensions, elements, and attributes of biophilic design. In S. Kellert, J. Heerwagen, & M. Mador (Eds.), Biophilic design: The theory, science and practice of bringing buildings to life (pp. 3–19). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=818992.

- Lenstra, N. (2020). Student wellness through physical activity promotion in the academic library. In Holder, S. and Lannn, A. (Eds.), Student wellness and academic libraries: case studies and activities for promoting health and success (pp. 223–240).

- LIBER. (2020). COVID-19 Survey report: how have academic libraries responded to the COVID-19 crisis? (Issue December). https://libereurope.eu/article/covid19-survey-research-libraries-europe/.

- Lucivero, F. (2020). Big data, big waste? A reflection on the environmental sustainability of big data initiatives. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(2), 1009–1030. doi:10.1007/s11948-019-00171-7

- Middleton, A. (2018). Reimagining spaces for learning in higher education. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Min-Allah, N., & Alrashed, S. (2020). Smart campus-A sketch. Sustainable Cities and Society, 59, 102231. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2020.102231

- Mirza, R., & Seale, M. (2017). Who killed the world? White masculinity and the technocratic library of the future. In G. Schlesselman-Tarango (Ed.), Topographies of whiteness: Mapping whiteness in Library and Information Science (pp. 171–197). Litwin Books and Library Juice Press. doi:10.1353/lib.2016.0015.3

- Obringer, R., Rachunok, B., Maia-Silva, D., Arbabzadeh, M., Nateghi, R., & Madani, K. (2021). The overlooked environmental footprint of increasing Internet use. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 167, 105389. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105389

- Pionke, J. J. (2017). Toward holistic accessibility. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 57(1), 48–56. doi:10.5860/rusq.57.1.6442

- Pontoriero, C., & Zippo-Mazur, G. (2019). Evaluating the user experience of patrons with disabilities at a community college library. Library Trends, 67(3), 497–515. doi:10.1353/lib.2019.0009

- Pyati, A. K. (2019). Public libraries as contemplative spaces: a framework for action and research. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 68(4), 356–370. doi:10.1080/24750158.2019.1670773

- Sahavirta, H. (2018). A garden on the roof doesn’t make a library green: A case for green libraries. In J. Schmidt (Ed.), Going green: Implementing sustainability strategies in libraries around the world (pp. 5–21). Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Salisbury, F., Dollinger, M., & Vanderlelie, J. (2020). Students as partners in the academic library: co-designing for transformation. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 26(2–4), 304–321. doi:10.1080/13614533.2020.1780275

- Santamaria, M. R. (2020). Concealing white supremacy through fantasies of the library: Economies of affect at work. Library Trends, 68(3), 431–449. doi:10.1353/lib.2020.0000

- Scholl, K. G., & Betrabet Gulwadi, G. (2015). Recognizing campus landscapes as learning spaces. Journal of Learning Spaces, 4(1).

- Schöpfel, J. (2018). Smart libraries. Infrastructures, 3(4), 43. doi:10.3390/infrastructures3040043

- Shea, G., & Derry, S. (2019). Academic libraries and autism spectrum disorder: what do we know? The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(4), 326–331. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2019.04.007

- Soria, K. M. (2013). Factors predicting the importance of libraries and research activities for undergraduates. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 39(6), 464–470. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2013.08.017

- Stewart, B., & Kendrick, K. D. (2019). Hard to find”: Information barriers among LGBT college students. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 71(5), 601–617. doi:10.1108/AJIM-02-2019-0040

- Tor, D. (2015). Exploring physical environment as hidden curriculum in higher education: A grounded theory study. Middle East Technical University.

- Wexelbaum, R. S. (2018). Do libraries save LGBT students? Library Management, 39(1/2), 31–58. doi:10.1108/LM-02-2017-0014

- Whitmire, E., Soria, K. M., Long, D., Harwood, S. A., Mendenhall, R., Lee, S. S., … Beilin, I. (2011). Everyday racism in integrated spaces: mapping the experiences of students of color at a diversifying predominantly white institution. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 4(6), 504–511. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1419122

- Wise, M. J. (2018). Naps and sleep deprivation: why academic libraries should consider adding nap stations to their services for students. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 24(2), 192–210. doi:10.1080/13614533.2018.1431948