ABSTRACT

This article defines the concept of open recognition and places its development within the context of the development of Wikipedia. The potential impact of open recognition on higher education is explored. This article defines Open Recognition as consisting of three elements a philosophy, a framework, and a practice. Open recognition has the potential to fundamentally alter higher education by lowering costs of reporting learner knowledge, skills, and abilities, while altering the scope of recognition to add informal recognition. Both open recognition and Wikipedia share common features and can both be categorised as open knowledge movements. However, in order to succeed as a robust network, Wikipedia had to overcome scepticism and public distrust around reporting accurate and relevant knowledge, partly by making its writing around knowledge formation visible. This article observes how Wikipedia overcame these obstacles and demonstrates how a fully mature and robust open recognition framework can create more durable experiences to connect learners to employers and the public.

As readers of this publication know all too well, the arrival of Wikipedia was facilitated by the arrival of creative commons licensing. Unlike traditional copyright licenses, which bundle together multiple kinds of permissions into one omnibus license, creative commons licenses allow users to create more narrowly tailored licenses. For example, a traditional copyright license combines the permission to resell, the permission to share, the permission to edit, and the permission to remix (among other permissions) into one license. In contrast, creative commons licenses dissect that copyright bundle of permissions and lay them bare for users so that they can tailor a license to suit their needs. The license used on Wikipedia, CC-BY-SA, allows anyone to take the Wikipedia content as long as they acknowledge Wikipedia as the source and similarly use the CC-BY-SA license if they share the Wikipedia content onward.

So the arrival of creative commons licenses was in effect an “un-bundling” of traditional copyright. Prior to this development, few people noticed that copyright was actually several types of permissions rolled up together. With the arrival of creative commons licenses, and the witness of more nuanced licenses popping up all over the internet, we saw in hindsight that our legal, commercial, and cultural institutions had conditioned us to think that the copyright bundle was the only method for framing permissions.

We are on the cusp of another “un-bundling” moment. This time, the un-bundling is coming for education, and the name of this next disrupter is open recognition. Just in the same way that we had been conditioned to think that copyright was the only method for conveying permissions until creative commons licenses arrived, so too does the arrival of open recognition demonstrate to us that our legal, commercial, and cultural institutions have trained us to think of the college degree as the main credential of learning accomplishment. Open recognition promises to change the landscape of education by dissecting the degree into smaller components, and allow for broader forms of recognition of accomplishment.

One might ask “What is Open Recognition?” at this point. Open recognition is the acknowledgement of lifelong and lifewide knowledge, skills, abilities, or accomplishments of individuals, shared across networks both electronic and human, and aggregated to the benefit of all. Just as Wikipedia is both a movement, and the manifestation of several articulations of openness, so too does open recognition sit atop three statements of openness: one political, one educational, and one vocational. In 1999, the Bologna Declaration created a political framework for open sharing of education throughout the European Higher Education Area. Subsequently, the 2008 Cape Town Declaration created an educational framework for the open sharing of learning objects through the creation of open educational resources. And lastly, a 2016 Bologna Open Recognition Declaration was issued as “a call for a universal open architecture for the recognition of lifelong and lifewide learning achievements” (Open Recognition Alliance, Citation2016). This latest Bologna declaration creates a framework for the free sharing of credentials, and seeks to extend to the workplace the principles of openness already established in political and educational realms.

In addition to these foundational frameworks, open recognition has also been nurtured by the culture of an academic conference, the ePortfolio and Identity Conference (ePIC, Citation2020). The first edition of this conference was billed as “The first International Conference on the e-portfolio” and was held in Poiters, France, in 2003 (e-portfolio, Citation2003). First proceedings of the conference highlight the goal of “structuring lifelong and life wide learning and continuing professional development” and also connecting the academic work of students with potential employers (e-portfolio, Citation2003). Over time, the conference would shift its focus to empowering learners, to employability, to developing competencies, to digital badging, and finally to open recognition, while maintaining an emphasis on supporting the ability of learners to claim and share accomplishments with larger audiences. The 2017 version of ePIC saw the launch of the “Make Informal Recognition Visible and Actionable” (MIRVA) project, with the express goal of “making visible and valuing learning that takes place outside formal education and training institutions, [e.g. at work, in leisure, in social settings, and at home]” through the introduction of open endorsements (MIRVA, Citation2020). The MIRVA project was funded by the European Union's Erasmus+ programme, with the goal of articulating a specific framework for open recognition under the lead author Serge Ravet and lead editor Dominic Orr (Ravet & Orr, Citation2020). The growth of the conference itself parallels the evolution from ePortfolio to open recognition, and highlights one of the essential connections between the ePortfolios and open recognition: using electronic platforms to translate academic accomplishments within formal education institutions for employers to discover.

This article will begin by further defining open recognition, and compare this new concept with examples from closed, proprietary networks of recognition. But in addition to introducing open recognition to many readers, this article will also argue that to best comprehend the potential of open recognition, we should also consider its development path in light of Wikipedia and other Wikimedia projects. This is for two primary reasons. The first reason why we should associate open recognition with Wikipedia is that like Wikipedia, open recognition must overcome deep societal scepticism and disbelief around credibility in order to reach its full potential. Just as Wikipedia was first mocked as folly for positing that complete strangers connected via the internet would collaborate to share useful knowledge, so too is open recognition challenged by the disbelief that complete strangers can provide accurate estimations of the knowledge, skills, and experience of a third party.

Second, both Wikipedia and open recognition share a special connection with education, and in particular writing education. In general, both Wikipedia and open recognition platforms operate as writing venues. They connect authors and audiences through specific knowledge on a shared topic of interest. In the case of Wikipedia the shared topic of interest is an encyclopaedia article and the knowledge written therein; in the case of open recognition, the shared topic of interest is a person and the knowledge, skills, and abilities attributed through the network. And, when deployed in educational settings, both Wikipedia and open recognition have the potential to connect students with larger audiences. Faculty who have taught with Wikipedia for the last two decades know that student writers feel connected to Wikipedia's readers and editors as they respond to the knowledge that students share (Cummings, Citation2020; Jemielniak, Citation2020). So too is it possible to design student projects on open recognition platforms to share knowledge and expertise about individuals, thereby connecting students with the world beyond higher education—specifically employers.

The stakes are high. If open recognition indeed has the potential of a knowledge platform similar to Wikipedia, its arrival could prove to be truly astounding for formal education systems. Why? Currently, the widest form of recognition is shared via proprietary networks such as LinkedIn. These networks, as rational actors within a capitalist system, seek to deploy the system of endorsements so as to maximise the value of their own network. Users freely (so far) surrender their valuable data about talents, skills, abilities, and experiences, in order to have access to the proprietary network and most likely improve their compensation for those talents, skills, and abilities. As the saying goes, if you’re not paying, you’re the product.

But open recognition, should it grow and develop along the path of Wikipedia, has the opportunity to radically alter the collection and sharing of recognition in at least two important ways. First, it can change the cost structure. If the platform for sharing knowledge about a user's vocational potential is open, then his or her participation can also be free, dramatically widening the potential audience and improving the connection of users with potential employers. Secondly, if these platforms can be open, then the scope of the knowledge shared on them can also be shifted. Currently the knowledge shared in networks such as LinkedIn or Indeed are arranged around the employment market. Users enter the network and claim knowledge, skills, and abilities which are generally tied to improving their marketability. As we will see when we visit the work of Serge Ravet, an open recognition network need not follow the same model. Instead, an open recognition network can record not only formal skills which are acknowledged through degree programmes, but also informal and much more narrowly defined skills—all the way down to recognising someone for simply reading a chapter in a book or sharing an insight in an online network. Thus the rise of open recognition has the potential to change formal education not only by reducing costs for student sharing of accomplishments in formal education, but also by incentivising the types of education which are less comprehensive than a degree or a certificate, and also those which happen beyond the timeline of a degree. In other words, open recognition networks, like Wikipedia, can open up the sharing of knowledge and turn it into a truly “lifelong and lifewide” pursuit. Again, the stakes are high, because should open recognition fail to reach its full potential, students and institutions in formal education could remain dependent on propriety networks, such as LinkedIn, to share accomplishments.

But before moving on to explore the similarities with the development of Wikipedia and open recognition, and their potential impact for education systems, we should first define open recognition. An adequate explanation of open recognition involves three components: a philosophy, a framework, and a practice.

Open recognition: philosophy

Similar to movements in open knowledge, open-source software, and open licensing, the philosophy of open recognition is that individuals own the ability to acknowledge lifelong and lifewide knowledge, skills, abilities, or accomplishments of other individuals, shared across networks both electronic and human, and aggregated to the benefit of all. Individuals may choose to organise themselves into collectives, and make recognition on behalf of organisations, but the philosophical distinction of open recognition is that the power of recognition rests with individuals first. Open recognition calls out the difference between formal recognition and non-formal recognition: formal recognition is knowledge recognised through degrees or certificates backed by collaborative judgments from those with positions in traditional institutions such as schools, colleges, and universities; informal recognition is knowledge recognised throughout life by individuals in multiple contexts and without necessarily invoking institutional affiliation or professional reputation.

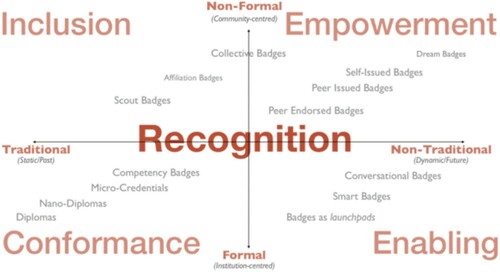

By its very existence, open recognition broadens the traditional conceptualisation of recognition across a spectrum with twin axes, as demonstrated through the illustration “Plane of Recognition” by Serge Ravet ()

On one end of the latitude of the spectrum of recognition is traditional learning, which is capped on the other end by non-traditional learning. The key difference on the latitudinal axis is an orientation toward time: traditional recognitions are focused on the past, with a static measurement of knowledge, skills, and abilities. Non-traditional recognitions are dynamic and future focused, as they are designed to respond more quickly and with specialisation toward recognising accomplishments. On the longitudinal axis, recognition runs from formal, institution-centred recognitions, toward the opposite pole of non-formal, or community-centred recognitions.

Open recognition also broadens the scope of what is deemed worthy of recognition. Traditional, formal institutions create organised courses and multiple assessments culminating in certificates and diplomas based on fields of study with deep historical, intellectual, and cultural histories. Open recognition places the scope and review of what is worthy of recognition strictly within the judgment of the recogniser. Open recognition might occur when an individual completes a free online course based on a specific topic—say, an emerging cryptocurrency—and receives a digital badge from the organisers of the course. Alternatively, it might occur when an individual grants a badge to a neighbour for simply doing a good deed. In either case, the philosophy of open recognition is that the decision of what is worthy of recognition and who meets that standard to receive that recognition rests entirely with the person or persons who decide to issue the recognition.

This philosophy represents a radical shift from a cultural and historical approach that is built around the foundations of reserving judgement of accomplishments to those who are vested with specific offices. Much in the same way open knowledge movements like Wikipedia have de-centralised the power to create knowledge by removing the step of qualifications as a pre-requisite for contributing knowledge, so too does open recognition remove the barriers of qualification in order to create recognition. Moreover, although Wikipedia allows a system of open contributions of knowledge, not all contributions remain online: the community has created and distributed the responsibility of reviewing submissions to maintain credibility. As we will see in the upcoming discussion of the open recognition framework, the methods for reviewing recognition are not identical to Wikipedia's methods and are largely determined at the level of specific projects (e.g. badges), but review does exist.

In general, the philosophy of open recognition is similar to the philosophies of other open movements in that once the barriers of sharing information have been reduced by the arrival of electronic networks, then the underlying cultural, historical, and legal frameworks of producing, distributing, and aggregating those information flows are re-examined. In addition, as in other open movements, open recognition has led to an awareness that not all recognition need be reserved for formal institutions. Once the costs of recognition have been lowered so that any individual can choose to award a badge to another individual, the scope of those recognitions can be similarly lowered and recognitions can operate at a granular level.

Open recognition: framework

The open recognition framework (aka “open recognition ecosystems”) provides mechanisms for the free exchange of recognition by creating a common framework for publishing and sharing tokens of recognition among the parties of issuer, holder, and the public. The framework reduces barriers to recognition, much in the way open licensing reduced the barriers of traditional copyright for the free exchange of ideas, by the technical platform or “highway” on which the philosophy of open recognition can be rendered and realised. To borrow an analogy from open source software: the software itself is the product, while the underlying framework of the open licensing and culture of sharing are the “pipes” or “highway” which make the distribution possible.

In defining the framework of open recognition, it is useful again to draw distinctions from proprietary recognition frameworks. In this case, the proprietary model of the LinkedIn network draws the most meaningful contrast with open recognition. LinkedIn is defined as “an American business and employment-oriented online service that operates via websites and mobile apps [...] mainly used for professional networking, including employers posting jobs and job seekers posting their CVs [with] most of the company's revenue [arising] from selling access to information about its members to recruiters and sales professionals” (“LinkedIn”, Citation2020). Within LinkedIn, it is possible for members to recognise the contributions of other members through a system known as “endorsements”. As with open recognition, whom to endorse and for what to endorse them is left up to the individual giving the recognition. However, unlike open recognition, all of the data—the name of the individual receiving the recognition, and the reason for the recognition, as well as the name of the recogniser—are proprietary data of the LinkedIn business. So while many might read about open recognition and challenge the viability of a framework of individuals awarding other individuals a range of recognitions—from the micro to the macro level—and wonder whether such a network could ever exist, LinkedIn demonstrates that not only can such a network exist, but that it can have a footprint conveyed by more than 675 million users and annual revenue of more than $154 million USD in 2011 (“LinkedIn”, Citation2020). And although some recent research has questioned the efficacy of job searches conducted via LinkedIn, there is ample evidence that the network has now come to dominate the job search market in terms of employment searches and employer recognition, with 75% of job searchers using the platform and a staggering 85% of employers relying on it for hiring decisions (Johnson & Leo, Citation2020; Kluemper et al., Citation2016; “LinkedIn”, Citation2020). In addition, Thus, while much about the open recognition framework is still in its infancy, the idea of sharing recognition for accomplishments across a large electronic network is a mature idea.

As mentioned in the introduction, the project Make Informal Recognition Visible and Actionable (MIRVA) is leading the work in articulating a framework for open recognition and has articulated a specific framework for open recognition under the lead author Serge Ravet and lead editor Dominic Orr (Ravet & Orr, Citation2020). Additional outputs of MIRVA include guidelines for communities and individuals; organisations and practitioners; technology providers and clients; framework validation; and guidance for linking informal recognition with frameworks (MIRVA, Citation2020). In articulating a framework for open recognition, Ravet is interested in tracking and making visible existing societal flows of recognition. To better track and articulate these relationships, he speaks of a recognition ecosystem, “operating within and across three levels: Micro (individual): recognition of and by individuals; Meso (organisational): recognition of and by communities formal and informalnetworks, groups, organisations, businesses, local and regional authorities, etc.; [and] Macro (societal): recognition of and by law—and the institutions enforcing the law at local, national and international levelsand by extension, market, culture and other societal/global systems” (Ravet & Orr, Citation2020). The vision of an ecosystem for discovering and locating existing recognitions is truly broad and suggestive a powerful new force for acknowledgement of knowledge skills and abilities. But how does such an ecosystem play out? This is the concern of the third aspect of the definition for open recognition.

Open recognition: practice

The practice of open recognition is where the philosophy, as applied through the framework, plays out for effect. And the most visible artefact in the practice of open recognition is the open badge.

Open recognition is often tokenised through open badges, which are sharable electronic instances of open recognition. More generally, open badges are a subset of digital badges, defined as a “validated indicator of an accomplishment, skill, quality or interest that can be earned in various learning environments” (Carey, 2012; as cited in Devedžić & Jovanović, Citation2015). What distinguishes open badges from digital badges more generally? Most open badges utilise the Open Badging Infrastructure, initiated through a 2012 collaboration between the Mozilla Foundation, Peer2Peer University, and the MacArthur Foundation (Knight, Citation2011).Footnote1 As the standards organisation IMS Global Learning Organization makes clear, “Open Badges is the world's leading format for digital badges. Open Badges is not a specific product or platform, but a type of digital badge that is verifiable, portable, and packed with information about skills and achievements” (OpenBages.org, Citation2020). IMS registers multiple projects that create and publish open badges. These include projects like Credly, Accredible, Badgr, Hyland Credentials, and Acclaim, each with its own emphasis and strategy to deliver open badges (IMS, Citation2020). While open badging is not the equivalent of open recognition, it most certainly is the largest and most comprehensive practice of open recognition to emerge.

Much in the way open licensing revealed that a set of intellectual property rules which are commonly associated with traditional copyright could be unbundled and recombined with more precise intents, so too does the establishment of open recognition make clear that the act of recognition has too often been culturally assigned to the institutions of formal recognition. Schools, colleges, and universities have for so long held legal and regulatory rights (often exclusive rights) to issue degrees, certificates, and licenses that our cultures have grown to accept these judgements of an individual's capabilities almost without question. The domination of formal recognition has such extensive roots in our cultural identity, that the idea of non-traditional recognition seems hard to fathom, even though non-traditional recognition is most certainly older than traditional recognition.

Wikipedia has also demonstrated the power of informal knowledge. As a platform which has greatly reduced the barriers of sharing knowledge, Wikipedia gestures toward a possible future of higher education in a world with robust open recognition. Much in the same way the audience of Wikipedia has overcome its scepticism about the knowledge presented on the platform by engaging with knowledge quickly and offering verification for those who want it, so too is there the possibility that in the future robust systems of open recognition could partner with formal education to manifest badges of competencies which are readily available and verifiable. The systems of formal recognition of knowledge may be required to grow and adapt to a world which demands formal knowledge as well as informal knowledge.

Even if the value proposition of open recognition is not directly tied to the growth of open badging, certainly the challenges of open badging inform the challenges to the growth and adoption of open recognition systems. In the next section, we will examine these challenges more closely.

Open recognition, wikipedia, and eportfolios: overcoming deficits of trust

Wikipedia, ePortfolios, and open recognition are examples of projects which have struggled to establish trust with the audiences they wish to serve. Initially, Wikipedia was mocked and ridiculed for its inability to ensure the accuracy and relevance of the information on its platform. If anyone could contribute to the world's largest and free encyclopaedia, how could audiences trust the information found there? Similarly, for decades, ePortfolios have claimed the ability to connect students with employers and convey the knowledge, skills, and abilities students have acquired in higher education. But the audience of employers has never fully embraced ePortfolios: there have been smatterings of engagement, but the employer audience has struggled to locate and trust evidence of knowledge, skills, and abilities acquired by students. Now comes open recognition, an expansive framework which seeks to extend the conversations between students and a larger public audience, including potential employers. Open recognition not only improves the abilities of students and graduates of higher education to share their accomplishments, but it also provides the ability to shift the scope of the content which they share. Open recognition envisions a future in which students can share not only degrees and certificates with employers, but also a world where informal accomplishments can be recognised by almost anyone.

And yet public trust remains elusive for open recognition. In addition to the struggle of establishing trust, open recognition also faces challenges of scale, habits of mind, and a cultural preference of embedding the authority of recognition solely within formal institutions. Cultural patterns and habits of mind dictate that the most meaningful recognition is reserved for formal institutions of education. In theory, open recognition allows for more granular measurements of learning, awarded on a more casual basis by peers. But trust proves to be an obstacle: since we do not trust ourselves to make recognitions of formal education, we are also trained not to trust ourselves to make smaller recognitions of learning. Many people are conditioned to think that recognition is solely the province of accredited institutions of education and therefore are not likely to grasp the new affordances of open recognition and participate in awarding recognition to peers. Many accomplishments will not rise to the level of a comprehensive certificate or degree. Open recognition provides the affordance of peer recognition. But because many of us are conditioned to pass recognition to those with qualifications, we are not attuned to the affordances of offering smaller and more granular representations ourselves.

Scale also remains a key barrier to widespread adoption of open recognition and is linked to the hurdle of individuals’ resistance to trust themselves to make informal judgements, inhibiting open recognition from becoming a larger movement. As the innovation of awarding recognition on a granular level is overlooked on an individual level, this phenomenon will play out on a larger level to keep open recognition relatively suppressed. The fact that both institutions and individuals are not conditioned to look for open recognition tokens means that open recognition is challenged in terms of building cultural momentum.

It is difficult for any new concept to take hold in popular imagination, especially when the first encounter with the new concept cannot be controlled. For open recognition, the inability to achieve scale is closely associated with the problem of creating a uniform and representative first experience for new users to engage with the concept while relying on user-generated content. What does this mean? Consider how most users will first encounter open recognition. Most likely, when open recognition networks reach a certain level of maturity, open badges will start to penetrate the dominant social media platforms. Then, through the experience of receiving a badge or encountering a badge given to another person, the potential new users of open recognition will start to engage with the concept. But the representation of the overall concept of open recognition may not be accurately encapsulated through this first user engagement with a badge: the badge may not be relevant (it could be issued for the wrong skill or the wrong person), the badge may not be accurate (the skill attributed might not truly be held), the new user might not become aware of all the features of the badge (for instance, they might not be aware that they themselves—as opposed to institutions—can also issue badges), and badges themselves are one instance of open recognition (as opposed to the entirety of affordances available under open recognition). In short, a user's first impression of the concept of open recognition is entirely dependent on how another user decides to deploy open recognition. This introduces a great amount of variability to any user's initial experience.

An inherent challenge in scaling open recognition is that any human who encounters a new concept will comprehend it by establishing a comparison to a known concept. As the new concept slowly evolves in the mind of the new user, it will be actively compared and contrasted with this known and similar concept. Thus, open recognition, which will most likely be introduced through the open badging, will be compared to other tokens of recognition with which a user will already be familiar. This may include the badges of the boy scouts or girl scouts (in the US context), or other similar examples of learning outside of formal education institutions. However, this first analogous comparison will likely hide essential features of the new concept from the user, too, if the user holds too tightly to the analogy, i.e. the open badge for hiking may well contain data as evidence of the accomplishment, while the user who equates the open badge to the old boy scout badge may not know to look for that affordance.

To borrow an organic metaphor, open recognition must grow in a forest within the shadow of mature competitors, demonstrated primarily through LinkedIn. As discussed above, LinkedIn has already established a broad electronic network around professional identity and representation. Within that network, a key feature is the ability to offer an endorsement of another person's abilities, skills, or services. This practice essentially mirrors one aspect of open recognition—micro recognition—but within a closed and proprietary network. This proprietary framework is particularly restrictive in that the potential equity value of the recognitions of network participants goes not to those who are doing the work, but to the network itself. Thus, LinkedIn demonstrates the incredible public demand for a knowledge base of recognition but keeps that knowledge under lock and key. Large public demand for knowledge which is shared by that very public calls to mind another model of knowledge sharing—Wikipedia.

The experience of Wikimedia and Wikipedia can inform the development of open recognition

The experience of Wikipedia is especially informative for the development of open recognition, as Wikipedia faced many of the same sets of challenges when it began operations in 2001. Wikipedia's relevant challenges include those of trust, scale, habits of mind, and a cultural preference of embedding the authority of recognition (or the authority to create knowledge) solely within formal institutions. Since its founding, the editing community behind Wikipedia frequently heard that the project could never succeed. In fact, Thomas Leitch identifies no less than fourteen arguments against Wikipedia in his chapter “The Case Against Wikipedia” (Leitch, Citation2014). And there have been numerous studies conducted on trust of Wikipedia's content (Dondio et al., Citation2006; Kwan & Ramachandran, Citation2009), but none more famous than the comparison of Wikipedia's content to the online version of The Encyclopædia Britannica (Giles, Citation2005). This most durable criticism against Wikipedia could be worded in this way: “Wikipedia will fail because it allows anyone to contribute to the website, and users must be qualified in order to speak knowledgably about a particular topic; no one can trust random strangers on the internet to provide accurate content”. This critique echoes the challenges to open recognition around embedding the authority solely within formal institutions, but also with around the issue of trust: whom do we trust to pronounce statements of knowledge, or to make the judgment of recognition? This criticism against the accuracy of information provided on Wikipedia by unqualified editors is similar to the trust issues of relying on judgements of complete strangers to speak to the qualifications of others in the system of open recognition. How did Wikipedia overcome this objection? And how can the experience of this Wikimedia project overcoming widespread doubt inform the growth path of open recognition?

The answer lies in part to the rhetorical situation that Wikipedia is able to duplicate widely through its user experience. When a user contributes knowledge to Wikipedia, s/he converts to the role of writer and is most likely able to envision a specific audience for the knowledge s/he is offering up. This impulse to share may have been created in the writer's mind by reviewing the existing article on Wikipedia and seeing a gap in the knowledge as it is presented. Once the user is aware that s/he can repair that gap, often with little effort, sharing becomes a powerful incentive. It is similar to being stopped by a stranger on the street, who is asking you for directions, in a neighbourhood you know well. Why not share the knowledge? And if you wish to question the knowledge on Wikipedia, contributors have also written about how the knowledge was collected. By reducing the barriers to sharing, by enhancing the visibility of who will benefit from the sharing, and by bolstering the confidence of the contributors of that knowledge, open recognition networks can similarly position themselves to capitalise on a powerful rhetorical structure.

What does this look like? Open recognition reduces barriers to sharing by removing costs already: it does not cost money to award an open badge to recognise the accomplishments of another. However, it may cost time: new users must familiarise themselves with the procedures of awarding badges. Open recognition systems can improve participation by agreeing upon a standard writing protocol for participating in sharing badges, regardless of the content of the specific recognition. Open recognition systems could improve participation, however, if they could help users visualise their audiences more reliably. To be sure, when one considers awarding a badge for recognition, the recipient of that badge is top of mind for the user. However, the secondary audience—those potential employers or colleagues who will benefit from seeing that the subject holds a badge—are more difficult for the badge giver to envision. If they were able to envision the cumulative good which awarding the badge might accomplish, they would be more likely to participate.

Last, some users might lack confidence to award recognition. They may hold doubts about their own judgments, or about how potential users might utilise their recognition. To bolster self-confidence in participating in open recognition, badging systems can publicise successful experiences. Or, open recognition might also solicit recognitions from additional users in a network, i.e. if I give recognition to my neighbour for playing the guitar at a block party, other residents might receive suggestions for similar micro recognitions. Ultimately, Wikipedia was able to overcome this problem through the growth of the network, aided by automatic suggestions linked to Google searches, and introducing itself to new users by providing ready information. A similar system could aid the development of open recognition systems and clearly help with problems of scale.

A similar criticism, also based on a lack of faith in the lowest common denominator of the public, simply mistrusts the ability of strangers to refrain from vandalism. This criticism reads something like: “Wikipedia will never succeed because anything on the internet which attracts attention will also attract malicious actors who will disfigure or destroy it either accidentally (with accidental or sloppy edits) or intentionally (by displacing legitimate content with gibberish or simply deleting content) because it is easier to destroy a free resource than to maintain it”. In many ways, this problem is a restatement of the concept of the tragedy of the commons.

Criticism toward Wikipedia's knowledge relevance editing structures and the general concerns about vandalism speak to challenges of trust. In the first case, critics are mistrustful of the ability of Wikipedia's contributors to self-edit and offer contributions that are on topic. If they are not able to do this, there will be a need for some editing, and there is often a deficit of trust for strangers to self-organise on a large network. And lastly, the fear of vandalism is simply a lack of trust for individuals to refrain from destructive behaviours when consequences are removed. But in each circumstance, Wikipedia has overcome these logical challenges in the only way its structure will allow: by distributing the tasks of editing content for relevance, organising for governance, and reverting destructive entries back to the community of editors. And over time, collaborating to make Wikipedia work better has built trust among the members of the community.

Open recognition faces similar challenges of trust deficits to those of Wikipedia. Open recognition users must trust that those who are making recognition are well-informed about the credential at hand. Systems of open recognition will also need communities of practice; the communities who are writing the technical frameworks for open badging will not be able to enforce community applications of those standards. And lastly, the community will need governance. Although vandalism might be less prevalent in a system of open recognition, there is always a possibility for bad actors to disrupt the intent of open recognition. And like Wikipedia, systems of open recognition will need to rely on its community of users to provide the labour for making sure that recognitions are relevant, administered reliably, and governed uniformly. The key will be distributing methods for community tending across multiple users in the open recognition network and in a format which does not overly tax any one user.

In sum, as Wikipedia gained content, it also built up a community. This community was able to successfully meet the existential challenges of this Wikimedia open knowledge project, and to gradually increase trust with its audiences. But for open recognition to meet its similar challenges, how will it attract and retain a community of users to do more than receive badges? How can open recognition create meaningful roles for users which expand beyond the transactional nature of badging? And how is providing general knowledge for the public different from providing knowledge about the accomplishments of an individual? What doubts must be overcome?

The path to overcoming a trust deficit for open recognition is located in the success of the two related frameworks of Wikipedia and ePortfolios, in that they are both electronic platforms which encourage writing as evidence to dispel doubt. Wikipedia, as a platform, encourages writing not only about the topic at hand, but also writing about how that knowledge was formed: what evidence was considered, what disputes arose, and how they were resolved. Similarly, the older iteration of open recognition, ePortfolios, encourages reflective writing, with students providing evidence of how they reached conclusions and milestones within higher education. When their audiences—the public, for Wikipedia, or employers, for open recognition—want more evidence to challenge claims, these platforms can provide it. This writing fluency is the reason why the categories of evidence selected for inclusion in digital badging systems will be key to supporting claims of knowledge made for the employer audience.

In their early days, ePortfolios were full of hope that they could help students connect formal learning with potential employers. ePortfolios could not only offer evidence of student learning but could also help students articulate that learning to employers, a conversation now bundled under the heading “the future of work”. But as we have transitioned from ePortfolios to badges, we run the risk of losing reflection. The structure of passive badges, or those received by a person without much engagement with the badge itself, mimics the structure of “leveling up” in video games and has brought criticism of digital credentials more generally (Mathews, Citation2016). Open badges share two fundamental components with ePortfolios: the ability to define learning outcomes and to provide evidence of that attainment. But badges of all types have not yet created a platform for reflection.

A challenge for anyone engaging open recognition at this stage of its development is to see the potential in the platform and what the future holds. No doubt it would be easier for readers if we could simply point to examples of robust open recognition networks. We cannot yet. The best we can do is point to proprietary credentialing networks, such as LinkedIn, and call out how they might operate if they were open platforms like Wikipedia. In 2007, Wikipedia was housed on a few servers in a strip mall in St. Petersburg, Florida. Today, most of the public in developed nations is comfortable with freely accessing “the sum of all human knowledge” via cell phones in their pockets. Should we expect any less for the credentials of all human actors?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 The initial thinking behind this collaboration is captured in a white paper “Open Badges for Lifelong Learning” attributed to the Mozilla Foundation, Peer2Peer University, the MacArthur Foundation, and Erin Knight, founding director of the open badging project at Mozilla.

References

- Cummings, R. (2020). The first twenty years of teaching with wikipedia: From faculty enemy to faculty enabler. In J. Reagle & R. Koerner (Eds.), Wikipedia@ 20: Stories of an Incomplete revolution (pp. 141–150). MIT Press.

- Devedžić, V., & Jovanović, J. (2015). Developing open badges: A comprehensive approach. Educational Technology Research and Development, 63(4), 603–620. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-015-9388-3

- Dondio, P., Barrett, S., Weber, S., & Seigneur, J. M. (2006). Extracting trust from domain analysis: A case study on the Wikipedia project. In L. T. Yang, H. Jin, J. Ma, & T. Ungerer (Eds.), Autonomic and trusted computing. ATC 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer science, vol 4158 (pp. 362–373). Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/11839569_35

- ePIC: the ePortfolio and Identity Conference. (2020). The ePortfolio and Identity Conference Home. Retrieved June 14, 2020, from https://epic.openrecognition.org/

- e-portfolio: The First International Conference on the e-portfolio. (2003). Retrieved October 27, 2020, from https://epic.openrecognition.org/proceedings/2005-3/

- Giles, J. (2005). Internet encyclopaedias go head to head. Nature, 438(7070), 900–901. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/438900a

- IMS Global Learning Consortium. (2020). “Product Certifications.” Retrieved June 28, 2020, from https://site.imsglobal.org/certifications?refinementList[standards_lvlx][0]=Open%20Badges

- Jemielniak, D. (2020). Wikipedia as a role-playing game, or why some academics do not like Wikipedia. In J. Reagle & R. Koerner (Eds.), Wikipedia@ 20: Stories of an Incomplete revolution (pp. 151–158). MIT Press.

- Johnson, M. A., & Leo, C. (2020). The inefficacy of LinkedIn? A latent change model and experimental test of using LinkedIn for job search. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1262–1280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000491

- Kluemper, D. H., Mitra, A., & Wang, S. (2016). Social media use in HRM. In M. R. Buckley, J. R. B. Halbesleben, & A. R. Wheeler (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 153–207). Emerald Group Publishing.

- Knight, E., Mozilla Foundation, Peer 2 Peer University, MacArthur Foundation (2011). Open badges for lifelong learning. Mozilla Wiki. Retrieved June 28, 2020, from https://wiki.mozilla.org/Badges

- Kwan, M., & Ramachandran, D. (2009). Trust and online reputation systems. In J. Golbeck (Ed.), Computing with social trust. Human–Computer interaction series. Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84800-356-9_11

- Leitch, T. (2014). Wikipedia u: Knowledge, authority, and liberal education in the digital Age. Johns Hopkins UP.

- LinkedIn. (2020, June 10). In Wikipedia. Retrieved June 14, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=LinkedIn&oldid=961805440

- Mathews, C. (2016, September 22). Unwelcome Innovation. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved June 28, 2020, from https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2016/09/22/essay-flawed-assumptions-behind-digital-badging-and-alternative-credentialing#.XwCv7fATvcc.link

- MIRVA: Making Informal Recognition Visible and Actionable. (2020). Retrieved June 29, 2020, from. https://mirva.openrecognition.org

- OpenBadges.org. (2020). Open Badges Home. Retrieved June 28, 2020, from https://openbadges.org/

- Open Recognition Alliance, The. (2016). The Bologna Open Recognition Declaration. Retrieved June 14, 2020, from https://www.openrecognition.org/bord

- Ravet, S., & Orr, D. (2020). Open recognition framework. Retrieved June 14, 2020, from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1n9Md4Dje9pTEyzbfTCtqSLhdf911cY_NvvvEe868nPY/edit?usp=sharing