ABSTRACT

In Poland, a country with a very high level of religiosity, religious education at school is confessional but not compulsory: it is an optional subject chosen by the student. In this article, we explore attitudes regarding participation in religion classes and explanations of the purpose of religious education as provided by adolescent students. We refer to the findings of our research on the rationality of school education and apply them to research on religious education. Rationality is defined as the logic of justifying the purpose of school education and four rationalities: praxeological, emancipatory, hermeneutic, and negational are distinguished. In a large and representative sample of secondary school students (N = 2,810), we examined the relationship between types of rationality and students’ attitudes and opinions towards religious education in school. We observed that high school students perceived religious education as highly conservative and declared the strongest support for more dialogical and liberal religious education. Moreover, students’ hermeneutical rationality was the primary factor associated with their lack of satisfaction with the current religious education and postulates to change it into a more dialogical one.

Introduction

Religion is taught as a school subject in the vast majority of European countries. However, there are differences in terms of organisational form and status (obligatory vs. optional subject), profile (confessional, confessional-dialogical, supra-confessional), curriculum design (responsibility solely with churches vs. churches in cooperation with educational authorities) as well as its pedagogical theory and legitimation. Notably, there are also models of religious education that do not involve churches or formal school education. ‘Religious studies’ is an example of religious education provided by institutions above the church; they do include the cultural specificity of the given country: on all levels of school education (e.g. in Sweden), in secondary schools (e.g. Denmark), or depending in form on the social institution running the given school (e.g. the Netherlands). Some Swiss cantons introduced a new subject, called ‘Religion and Culture’ or ‘Religion, Culture and Ethics.’ The concept of informal inclusive education is an entirely different matter; it is developed within the frame of the so-called career-oriented religious pedagogy. Grassroot activities of peer groups or interest groups are also examples of informal spiritual education, social, charity or cultural activity that can be inspired or supported by religious congregations.

Pedagogy of religion combines the normative character of a particular confession and the ethos of common good as well as social, cultural, and religious pluralism (Boschki Citation2008; Jackson Citation1997; Marek and Walulik Citation2020; Rothgangel Citation2014; Schweitzer and Simojoki Citation2005). The legitimacy of any school subject constitutes an important issue in educational studies. The analyses presented herein deal with the way in which the sense of religious education at school is read and attributed from the perspective of research on the rationality of school education (see e.g. Karwowski and Milerski Citation2021; Milerski and Karwowski Citation2016).

The population of Poland in 2019 amounted to 38.41 m (Statistics Poland Citation2020). Poland is a country where, both historically and currently, a dominant role is played by the Roman Catholic Church. Approximately 90% of the population declare their affiliation with it. The rest belong to other churches and religious associations or identify as atheists. It is estimated that the group of people who do not belong to any denomination amounts to ca. 8% of the society. This means that ca. 92% of people in Poland declare some kind of religious faith and confessional affiliation. It is disputed, however, how many percent of people who declare faith, do not participate in religious life (Milerski Citation2021).

Despite the statistical supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church, it should be emphasised that over 180 churches and religious associations in Poland have legal personality. The Roman Catholic Church operates on the basis of a concordat (signed: 1993; ratified: 1997). The Orthodox Church, six Protestant Churches, three Old Catholic Churches, the Union of Jewish Religious Communities, the Muslim Religious Union and the Karaite Religious Union operate on the basis of separate parliamentary laws on the relationship of the state with individual communities. In addition, 168 churches and religious associations (as of 08.02.2021) operate on the basis of legal registration with the ministry responsible for religious affairs (currently the Ministry of the Interior and Administration).

The high level of religiousness in Poland can be described as hyper-religiosity. This concept reveals a high number of declarations of confessional affiliation, but also the intensity of religious involvement and the influence of religion on social, cultural, and political views (CBOS Citation2020a, Citation2020b). The phenomenon of hyper-religiosity is defined: 1) in statistical terms, as a very high percentage of people who declare religious faith and confessional affiliation (92%); 2) in terms of religious involvement: 38% of Catholics attend worship every Sunday (ISKK Citation2020, 23); 3) in terms of a strong connection between religion and the biographical rites of passage, tradition, customs, and politics. Here, we use metaphor of hyper-religiosity in a descriptive rather than evaluative way to denote primarily external and behaviour-based indices of engagement in religious life. Consequently, by hyper-religiosity, we do not understand religion’s internalised, personal role but rather its social, largely external representations.

Religious education in Poland

Religion as a subject of school education was introduced in Poland in 1990. It was the effect of political transformation in the wake of overcoming communism, considering the role of religion in the history and current life of society. On 4 June 1989, partially free parliamentary elections were held in Poland. They resulted in the rejection of the communist system and a political, social, and economic transformation.

In a country with a predominantly conservative and Catholic tradition, the return of religious education to schools was generally well received. However, some criticism was voiced with regard to the observance of the principle of world-view neutrality of public institutions and the fact that church authorities were given the exclusive right to decide about the design of religious education curricula for schools and about the employment of religion teachers. This polemic stemmed from the dispute over the shape of the understanding, in which the visions of conservative and national democracy clashed with one of liberal and worldview-neutral democracy. In consequence, the dispute over the shape of the state also implied questions about the concept and organisation of school education, including availability of religious content, symbols and practices at school. The status of religious education at school is regulated by the 1992 Ordinance of the Minister of National Education on the conditions and manner of organising religious education in public schools (as amended, consolidated text: Journal of Laws 2020, item 983).

Religious education is an optional subject – students may choose to study religion or ethics, but they may also choose not to study either of those. If they choose neither, a dash will appear on their school report card under the heading religion/ethics, but this has no bearing on the student’s progress to the next grade. Recently, the conservative ruling parties in Poland have started a discussion on making the religion/ethics block compulsory, yet currently, the classes still have the status of an additional and optional subject.

Religious education is confessional and takes 2 hours a week. The syllabus and, as a matter of fact, the appointment of teachers falls within the competence of churches and religious associations. Teachers are employed and paid by the school, but their employment is conditional upon recommendation by a church authority. Religious education at school can take place either directly in the school building or in the so-called out-of-school catechetical posts organised in church buildings. Under certain conditions, out-of-school catechetical posts are considered to be part of the public education system.

Every church or religious association in Poland may claim the right to teach religion within the public education system. The solutions adopted in Poland are conservative in terms of church supervision of curricula, employment of teachers, as well as practical implementation of religious education. However, they are very liberal with regard to the availability of religious education for all students, including those belonging to religious minorities. According to the Catholic ‘Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia AD 2020,’ 88% of students attend religious education classes (ISKK Citation2020, 46).

From today’s perspective, the phenomenon of secularisation has become a challenge (Diller and Gareis Citation2020). It is associated with society distancing itself from the normative position of churches. Religiosity is constructed in an individual, selective, and privatised manner (Berger Citation1980; Luckmann Citation1991; Mariański Citation2004). Secularisation can develop towards irreligion (EKD Citation2020). Religion and religious education can also be interpreted from a post-secular perspective (Franck and Thalén Citation2021).

In this article, we posit that in order to understand the status of religious education at school – apart from the phenomenon of secularisation – it is necessary to consider how students perceive the purpose of school education. In this paper, we refer to research on the rationality of school education (Dressler Citation2009) as a potentially insightful theoretical background that might inform inquiries in students’ perception of the sense of religious education. In the section that follows, we delineate the main assumptions of the tetragonal theory of the rationality of school education.

A tetragonal theory of the rationality of school education

The notion of rationality (Bevan Citation2009) is central to our research and analysis. We draw inspiration from various concepts: rationality of the Enlightenment (Kant) and its critical analysis (Horkheimer, Adorno); rationality of social life (Weber); humanistic rationality (Dilthey, Heidegger, Gadamer); critique of instrumental reason (Horkheimer Citation2011); as well as rationality of constructing knowledge in social sciences (Habermas Citation1973). A special role in the construction of theoretical foundations was played by the achievements of the Frankfurt School.

Habermas’ main objective in ‘Erkenntnis und Interesse’ was to define cognitive interests that guide the different types of scientific knowledge. Knowledge in social sciences as a form of social knowledge is considered neither neutral nor objective. It is guided by specific cognitive interests characteristic of a given type of scientific cognition. Habermas analysed three research traditions: positivist, hermeneutic, and critical. He argued that these three traditions result in two types of scientific knowledge construction. Despite fundamental substantive and methodological differences between them, the positivist and the hermeneutic tradition are guided by similar cognitive interests: they generate practical, technical, and adaptive knowledge. Critical theory is guided by emancipatory and communicative interests, oriented at transformation towards the empowerment and expansion of each individual’s freedom, democracy, pluralism, justice, and social inclusion (Habermas Citation1973). Rationality consists not so much in the possession of particular knowledge, but rather in ‘how speaking and acting subjects acquire and use knowledge’ (Habermas Citation1988, vol. 1, 25). This thesis, posed at the beginning of the ‘theory of communicative action’, links the problems of rationality with the way knowledge is created and used.

We applied the philosophical theory of the Frankfurt School to pedagogical issues. Pedagogical knowledge and pedagogical relationships are hardly neutral. Educational practice is guided by cognitive interests (Bourdieu and Passeron Citation1990; Giroux and Witkowski Citation2010; McLaren Citation2015; Mollenhauer Citation1968). These issues have also been addressed by a current within the pedagogy of religion that emerges from critical theory (Stock, Vierzig, Zilleßen) and one that is oriented towards the relationship between religion, pluralism, and democracy (Hull Citation1984; Schlag Citation2010).

Individual thinking, acting, and perceiving reality is not merely the result of the decisions of an isolated mind, but of the individual’s consciousness, which is individual but at the same time rooted in social consciousness and thus it expresses the ideological interests of specific social groups. These relationships are not ideologically neutral. They are linked to interests of specific social groups. An ideology is a form of social consciousness that serves the particular interests of a given social group in terms of organisation and norms of social conduct. Critical theory formulated the notion of cognitive interest as ideological interest. It originally referred to knowledge production in social sciences. Theories of social sciences are not neutral and objective (Horkheimer Citation2011). Nowadays, we also apply the concept of ideological interest to social practices, including educational practices.

Educational rationality is defined as the logic of justifying school education considering the cognitive interests specific to certain social groups (Giroux and Witkowski Citation2010). Rationality is not abstract, nor is it determined solely by an individual’s state of consciousness. It is the result of the individual and the social (Jenks Citation2012).

We (Milerski and Karwowski Citation2016) distinguish four types of school rationality: praxeological, emancipatory, hermeneutic, and negational (see also Karwowski and Milerski Citation2021). Praxeological rationality justifies the meaning of schooling in utilitarian terms, referring to concrete benefits that result from education. It is characterised by quantifiable learning outcomes and the possibility to measure them. Emancipatory rationality refers to the concept of emancipatory and communicative interest derived from critical theory. School education is intended to emancipate and increase the extent of a student’s freedom, which will be achieved through their participation in the social discourse around the norms and values of society and their assumption of responsibility for social transformation. Hermeneutic rationality justifies the sense of learning in terms of the ability to understand and value one’s own existence as well as the external social and cultural reality. Negational rationality is related to a protest against school education in its current form. It may consist in a complete rejection of the school or in a criticism of it, which allows for the possibility to modify the forms and content of education.

The present study

The present investigation employs a sequential, mixed-method design to explore a fundamental research question concerning adolescent students’ attitudes towards religious education. More specifically, we integrate a massive quantitative survey, representative for secondary school students, with a qualitative part that allows us to better understand the nuances of students’ opinions. Our critical variable of interest is students’ perception of the current and ideal status of religious education. We attempted to operationalise it quantitatively (see description below) and qualitatively during in-depth individual and focus group interviews. Consequently, our main question of interest was potential discrepancy (as perceived by students) in the current form of religious education versus a preferred (ideal) situation. Our secondary questions addressed plausible predictors and moderators of these differences. We were particularly interested in a possible role played by participants’ gender, their school types (high school, secondary technical school, vocational school), and perceived educational rationalities.

Method

Data availability statement

The dataset used in this study is available in the OSF Archive: https://osf.io/s8fdt/?view_only=e11fcef6704b470d952fb79026e81b30

Participants

In the quantitative survey, the participants included secondary school students (N = 2,810), as well as their teachers (N = 321) and parents (N = 2,676). The group of students was selected so as to be representative of the entire population of secondary school students in Poland. All participants attended public schools; according to participants’ declarations in all these schools, religious classes were taught according to the Catholic Church rules. Given the focus on this investigation, we analyse only data obtained from the students sample.

Measures

Participants’ background and demographics

Participants were asked to provide basic information regarding their demographic and social background; namely, they reported their gender (53% females), age (range 16–21, M = 18.00, SD = 0.86), and parents’ education (24% of mothers and 17% of fathers were college or university graduates).

Attitudes towards religious education

To capture the attitudes towards religious education, we created a questionnaire consisting of two main parts (see Supplementary Online Material in the OSF archive). The first question assessed religious education from the perspective of its contribution to human development. There were four possible answers ranging from the statement that religion classes impart important knowledge and support human development to the statement that religion classes have little educational value.

The second question referred to the level of participation in religious education in schools. The following two items consisted in selecting the opinion that most closely matched participants’ beliefs. The first question concerned the shape of religious education in schools: 1) ‘schools should deliver religious classes in the way it’s been doing it to-date,’ 2) ‘religion should not be taught at schools,’ 3) ‘religion classes should be taught at schools only when much greater emphasis is placed on multitude of views, including other churches and religions.’ The second question concerned the conceptualisation of religious education at school: from understanding religious education as a form of instruction in the spirit of a particular church to understanding education as a form of transmission of knowledge about different churches, religions, and world views, considering the position of one’s own confession.

Central to our research questions were the next two sections of the questionnaire. They were based on a semantic differential that included seven questions, with poles marked by polarised responses. An example included: ‘Religion classes at school are conveying a doctrine of a specific church’ versus ‘Religion classes at school are conveying knowledge of various churches.’ All seven questions are provided in the Results section (see ). The attitudes towards each of these issues were measured on a 7-point scale. We used semantic differentials twice: in the first case, students expressed their opinions about the current state (‘how it is’), in the second case about ‘how it should be.’

Table 1. Items used to measure the attitudes towards current and ideal religious education and their descriptive statistics.

Educational rationality

We measured students’ educational rationality using the full version of the Educational Rationality Questionnaire (ERQ, see also Karwowski and Milerski Citation2021 for a shortened version of this instrument). The version of the ERQ used in this study consisted of 45 items. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses presented elsewhere (Milerski and Karwowski Citation2016) confirmed a four-factor structure of ERQ, with four rationalities being covered, namely: hermeneutic (15 items, sample item: ‘Schools should teach to interpret culture and traditions,’ Cronbach’s α = .82 in this study), negational rationality (10 items, sample item: ‘Nowadays, schooling is a waste of time,’ α = .82), emancipatory rationality (13 items, sample item: ‘Thanks to education people find it easier to be themselves,’ α = .65), and praxeological rationality (7 items, sample item: ‘It’s important to learn useful things at school,’ α = .81). All items were presented to the participants twice. First, using a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 = definitely not and 7 = definitely yes, participants responded to all items. In the second part, after some buffer questions, they were presented with all items once again and asked to indicate no more than five responses they consider the most important. Items that received a score of 7 in the first part and then were selected among the five most important were recoded to a value of 9, to increase variability and emphasise their relevance. Consequently, the average results in four rationality scales ranged from 1 to 9 (see SOM for the full version of ERQ).

Procedure

An external research company recruited schools. Using a multilevel and multi-strata selection procedure enabled us to obtain a sample of Polish secondary school students, which might be considered representative for secondary schools. The sample was drawn from the Polish Educational Information System (https://cie.men.gov.pl/sio-strona-glowna/). Schools were randomly selected and two or three randomly chosen classes from each school were invited to participate in the study. Students filled the questionnaires during their regular classes and were randomly recruited to the study’s second – qualitative – part. Informed consent was obtained from all the teachers and students as well as from school principals and students’ parents.

Qualitative part

The qualitative study consisted of in-depth individual interviews (IDIs) and focus group interviews (FGIs). We conducted 21 IDIs and 8 FGIs. The interviews were based on a script that covered an introductory section, past biographical experiences, current experiences, a vision of the future. All interviews focused on the issue of experiences and perceptions related to school education. In all interviews, the scripts included questions about students’ experiences and opinions related to religious education.

Analysing the transcripts of the interviews, we referred to the framework of humanistic hermeneutics (Danner Citation1998; Rittelmeyer & Parmentier Citation2001). We applied the objective hermeneutics methodology (Oevermann Citation1981, Citation2002; Wernet Citation2006), and termed it the ‘hermeneutics of intersubjectivity.’ Interpretation comes as a result of recognising four categories: latent meanings, interpretative selection, sequentiality of certain types of interpretation, and the relationship between part and whole – the meaning of an utterance in the context of the entire narrative and vice versa (Oevermann Citation2002; Wernet Citation2006).

Results

Religion classes at school were attended by 80.3% of students, and almost ¾ (74.5%) of them declared participation in more than 50% of classes. Participation in religion classes was more profound in high schools (83%) and secondary technical schools (84%) than in vocational schools (75%, χ2[df = 2, N = 2745] = 18.27, p < .001) and more often observed among female (85%) than male students (79%, χ2[df = 1, N = 2693] = 12.76, p < .001.

General opinions on and attitudes towards religious education in school

As for the question about the perception of the general educational relevance of religious education at school, the opinions were almost equally divided. Every fourth (24%) student believed that religion classes impart important knowledge and support human development. An almost the same amount (26%) thought that religion classes realise these goals only partially, 14% declared that religion classes realise these goals to an insufficient degree, while every third student (33%) answered that religion classes are of little educational importance.

Almost half (44%) of the students seemed to accept the current form of religious education at school, 28% were clearly against religious education at school, while 26% believed that religious education can be conducted at school provided that it is open to pluralism of views. These results indicate a slight predominance of students rejecting the relevance of religious education in school or demanding a change in the concept. Notably, the rejection of religious education in school may have two reasons. The first is tied to a liberal attitude criticising religion in its conservative variety, while the second reason, on the contrary, is tied to a conservative and charismatic attitude. According to people representing such an attitude, religion should not be taught at school as a matter of principle.

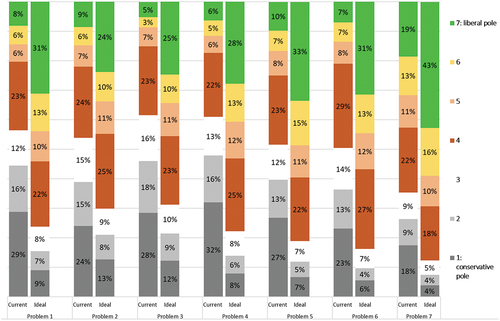

To explore potentially more nuanced attitudes, we analysed responses to the seven problems included in our semantic differential measure. presents the problems as well as descriptive statistics.

As mentioned, all these problems were defined in two versions: ‘how it is now’ (current) and ‘how it should be’ (ideal). illustrates the distribution of the responses.

Figure 1. Semantic differential: religious education in school – current vs. ideal (%). See for the exact wording of problems 1–7.

In their opinions about ‘how it is now,’ most students pointed to the conservative nature of religious education at school. Not only did it apply to the content, but also to the form of teaching, as demonstrated by the distribution of responses to problems 5, 6 and 7. We emphasise that all the differences presented were highly statistically significant (p < .001). To more synthetically quantify the gap between ‘what is’ and what should be”, we created two aggregate variables: one describing the status quo (‘current,’ Cronbach’s α = .87), the other describing how students think things should be (‘ideal,’ α = .89). In both cases, a higher score corresponded to the preference for more open and dialogical religious education at school.

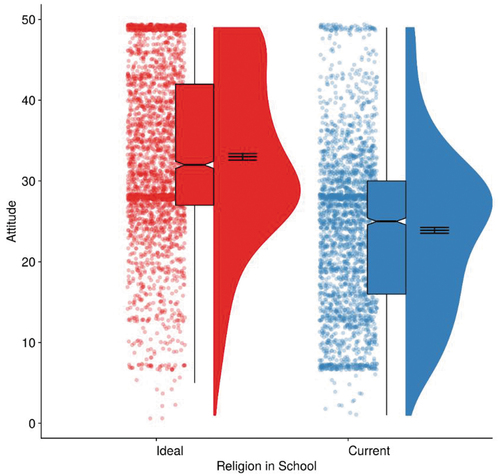

As expected, we found that students demanded significantly more dialogue (M = 33.67, SD = 10.58) than is currently the case (M = 22.89, SD = 9.79). Not only was this difference statistically significant, t(df = 2743) = 38.16, p < .001, but it also indicated a fairly robust effect expressed in standardised unit: Cohen’s d = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.59, 0.67 (see ). The correlation between views on the current and ideal state of religious education was negative and weak but statistically significant: r = −.06, p = .004.

Figure 2. Religious education in school: a comparison between ‘how it is now’ (‘current’) and ‘how it should be’ (‘ideal’).

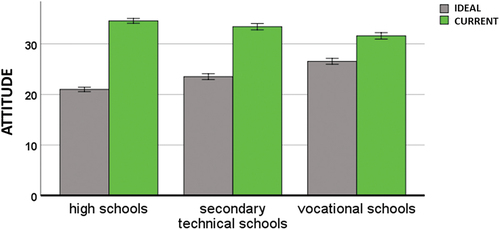

Did the attitudes of students depend on the type of school they attended? To answer this question, we conducted an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using a mixed-effects model, where the within-factor was the current-vs.-ideal state of religious instruction and the between-factor was the type of school the students attended. Given the unequal representation of male and female students between types of schools (female students formed 65% of all high school students, 42% of secondary technical schools students, and 32% of vocational schools students, χ2[df = 2, N = 2751] = 200.13, p < .001), we included participants’ gender as a covariate in this analysis. The analysis confirmed the main effect of the ‘current state – ideal state’ comparison noted earlier, F(1, 3627) = 223.76, p < .001, η2 = .06, but also a statistically significant effect of school type, F(2, 3627) = 10.73, p < .001, η2 = .01 and an interesting Type x Attitude interaction, F(2, 3627) = 136.45, p < .001, η2 = .07. The latter effect was moderate in strength and showed that students of high schools were most critical of the current state of religious education at school and had the highest demand for a change towards a more dialogical and open character of religious education at school (). Participants’ gender included as a covariate significantly differentiated the current-vs.-ideal comparisons (F[1, 3627] = 17.13, p < .001, η2 = .005), thus supporting the decision to control for gender differences between types of schools.

Rationality of education and the perception of religious education

The next step of our analyses was oriented towards showing the relationship between opinions about religious education at school and dominant types of educational rationality.

Analysis of variance demonstrated that praxeological (technical, utilitarian) rationality was most prominent in opinions regarding the purpose of education (M = 6.87, SD = 1.13). Hermeneutic rationality describing the other extreme – intrinsic nature of education was slightly less endorsed (M = 5.08, SD = 1.03), followed by emancipatory (M = 4.35, SD = 1.14), and negational rationality (M = 4.12, SD = 1.37) (F[1, 3784] = 5811.15, p < .001, η2 = .61.

In order to examine the extent to which individual rationalities are related to opinions about religious education at school, we conducted regression analysis. More specifically, we proceeded with three hierarchical models: the first used the ‘current’ situation of religious education as a dependent variable, the second explained the variability in the ‘ideal’ attitude, while the third utilised the difference between the ‘ideal’ and ‘current,’ meaning that it predicted the distance between the status quo and the desired situation. In all three models, we first introduced control variables (participants’ age, gender, and type of school), while the second step included four rationalities as predictors ().

Table 2. Relationships between educational rationality and opinions about religious education at school: results of regression analyses.

As illustrated in , the models were characterised by a good fit and explained between 9% (current religious education), 11% (ideal religious education), and 17% (the difference between ideal and current situation) of dependent variables’ variability.

Participants’ gender and age were unrelated to opinions regarding the current religious education, while male and younger students tended to have higher expectations regarding the ideal religious education. At the same time, female and slightly older students tended to have a bigger gap in their perception of ‘what should be’ and ‘what is.’ As illustrated before, compared to high school students, their peers from technical secondary and vocational schools were more satisfied with the current state of religious education and demanded less potential changes that should be introduced. Consequently, the gap between ‘what should be’ and ‘what is’ in their perception was smaller than in the case of high school students. Overall, control variables were associated with 3% of ‘the ideal’ situation, 5% of the current situation and 7% of the ideal-current variance. Thus, although statistically significant, this effect size could be considered a small-to-medium effect (Cohen Citation1992).

Was students’ educational rationality related to their attitudes and assessment of religious education? The second step in our models focused on this particular research question. As presented in , in all three models, rationalities were associated with a unique and significant portion of the variability of dependent variables of interest: be it a perception of the current religious education, demand for the ideal, as well as the ideal-current gap. In short, students with predominantly hermeneutic rationality tended to reject the existing practice of religious education in school and argued for greater openness to plurality of views, dialogue, and discursive character. The stronger their hermeneutic rationality was, the bigger the gap between what ought to be and what is in religious education. Intriguingly, the opposite effects were observed in the case of emancipatory rationality. The higher students’ emancipatory rationality was, the more satisfied they were with the current status of religious education and expected less changes in the future. This pattern presents an interpretive challenge we focus on in our qualitative study and Discussion section. The effects of negational and praxeological rationalities were less systematic and negligible in terms of size (beta coefficient).

Main results of the qualitative study

The qualitative research shows differences in the justification of the purpose of religious education in school. Interview transcripts have been analysed from the perspective of interpretative selections (choices) made by students, the sequential nature of such selections, and the relationship between the interpretation of individual fragments and the interpretation of the interview transcript as a whole. Combination of these three elements of interpretation allowed us to define the latent meaning that binds the transcripts of individual interviews into a meaningful whole. It also allowed to read the intentions, motivations, and individual interpretations regarding the meaning of school education in the perspective of one’s life experiences.

Through qualitative analysis, we were able to identify the following phenomena: conditionality of one’s declared rationality of education on one’s cultural capital and educational aspirations; inter-rationality: complementarity of rationalities of education; negational rationality as a result of negative experiences; praxeological rationality as a result of an adaptive and utilitarian attitude; emancipatory rationality as perceived from the perspective of the primacy of inward oriented emancipation and hermeneutic rationality as a humanistic legitimation of education.

In general, students in whom praxeological rationality predominated were guided by practical, utilitarian, and often conformist arguments. The practical arguments covered a spectrum of issues, such as historical tradition, belonging to a confessional tradition, national identification (Polish = Catholic), fulfiling the conditions for receiving the sacraments, and the opinion of one’s community. They also included typically utilitarian issues: religious education interferes with other activities (e.g. sports, music, etc.), meetings with friends, is planned in the first or last period of a day (time-saving argument). Another important aspect was the evaluation not so much of religion as such, but of the way in which religious education was implemented in practice at school. These arguments were used to justify both positive and negative opinions about religious education at school.

The spectrum of hermeneutic arguments was broad too: religious education vis a vis developing one’s personality and spirituality, teaching how to understand oneself, one’s interpersonal relations and the surrounding reality, to analyse one’s existential and social problems in a reflective and discursive way, developing the ability to evaluate individual and social actions, creating a ‘reconciled’ vision of religion, culture, individual, and social life. If religious education in a particular school fulfilled these conditions (according to students), it was evaluated positively. If it did not meet these conditions, it was criticised from a hermeneutical perspective.

The most intriguing finding was related to emancipatory rationality. According to critical pedagogy, emancipatory rationality should combine the formation of empowerment with social responsibility, communication, and social transformation. However, in our study it became apparent that from the perspective of students emancipation means first and foremost individual self-determination in terms of self-actualisation as well as in professional and financial terms. We referred to this phenomenon as inward-looking emancipation. The humanistic approach, typically associated with the justification of schooling as a process aimed at developing one’s competence in understanding and assessing reality, is revealed primarily within the framework of hermeneutic rationality. These are the most general conclusions of the study on the rationality of school education per se.

Discussion

Religion can be dangerous: this statement is often voiced following the recent wars in the Balkans, the September 11 attacks, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, or the current tensions in the Middle East. It also appeals to the imagination of modern multicultural societies, where conflicts of a social, political, or interpersonal nature are instrumentally transformed into religious disputes. Therefore, modern societies need rational religious literacy and education. Its primary setting should be school. Religious education in school must not be merely a matter of conveying confessional beliefs (Kittelmann Flensner Citation2017). Instead, it is very much a part of public enlightenment and general education (Cush Citation2021; Dewey Citation1903).

As we argued in this article, in Poland we are faced with the phenomenon we called hyper-religiosity. It not only concerns declarations of faith, but primarily external factors as participation in religious services, including religious education. The percentage of secondary school students participating in religious education is still very high – about 80% in our investigation. Nevertheless, a decline is being observed. Traditionally, this decline is associated with the secularisation processes taking place in modern societies.

In the article, we point to one more important determining factor. This factor is the prevailing praxeological rationality of school education and a phenomenon we called an inward-oriented emancipation (Karwowski and Milerski Citation2021). This type of rationality seems to influence perceptions of the purpose of school education, including religious education. Moreover, we observed that students with prevailing hermeneutic rationality have a clear negative attitude towards the current form of religious education in school. The overall results indicate that students are in favour of changing the concept and practice of religious education in school. They demand a broader spectrum of topics, openness to other confessions, a dialogical, and discursive approach.

The biggest surprise and interpretational challenge came with the results regarding the effect of emancipatory rationality on the concept of religious education in school. As we demonstrated, students with predominantly emancipatory rationality were found to be more positive about the current state of religious education in school and much less in favour of a liberal and dialogical change. Consequently, the higher their emancipatory rationality scores were, the lower the perceived gap between the ‘ideal’ and ‘experienced’ situation. Although surprising at very first sight, this pattern seems to be in line with our interpretation of emancipatory rationality as inward-looking emancipation. It is plausible that for a certain category of students, religious education, in whatever form, serves primarily to satisfy utilitarian ends. In the case of the Catholic religion, this may have to do with the practical necessity of obtaining a certificate, which – for example – is required if one’s wants to have a church wedding.

Students’ praxeological rationality was unrelated to their opinions regarding ‘how it is now’ in religious education, but the more praxeologically oriented students were slightly more open to changes in future religious education. This effect, however, was close to zero and is unlikely to be meaningful practically. We have also observed a weak yet positive effect of negational rationality on the opinions about religious education at school in terms of ‘how it is now,’ but negational rationality was unrelated to ‘how it should be.’ Once again, it seems that students’ negational rationality does not interfere with their perception of religious education. In short, what our analyses demonstrated is a robust effect of hermeneutical and emancipatory rationality on the attitudes towards current and future (demanded) religious education.

Importantly, our study was not only concerned with the teaching of religion, but also with the broader meaning of school education as a whole. The perspective that included a holistic understanding of education informs a more fine-grained analysis of the perception of religious education at school. Therefore, our analyses integrated survey results of students’ opinions using an educational rationality questionnaire with the insights coming from individual and group interviews. A methodological synergy these two methods bring allows for a more realistic description and attempts to shape the teaching processes in school. For example, from a praxeological perspective, religious education can serve as an introduction to ritual religious practices. At the same time, however, by some students it can also be perceived as a school subject that is detached from practical life. From a hermeneutical perspective, it can become the foundation of humanistic and social education. Our research clearly shows that hermeneutic rationality denotes an openness to religious discourse. However, this openness is conditional upon the open substantive, instructional and cultural nature of religious education. Our qualitative research showed that students with a hermeneutic orientation accepted religious education at school as long as it fulfilled their hermeneutic existential, social, cultural needs. If religious education failed to meet these needs, they simply abandoned it.

Limitations and future directions

Although this study is based on a large and representative sample of Polish adolescents and synergistically utilised quantitative and qualitative results, its findings should be read in light of some natural limitations. We particularly emphasise two of them. First, while the representativeness of the sample is a strength, it also forms a challenge. More specifically, based on our results, we were unable to compare the results to opinions of students outside of the dominant Catholic Church. Therefore, the extent to which the patterns we obtained generalise to students who attend to religious classes conducted by other than Catholic churches remains a question that is open for future investigations. Although it was not a main focus of our investigation, we believe that such a comparison would be both interesting and meaningful.

Second, we note that our dependent variables in the quantitative study were largely based on declarations and self-report measures. Although we did our best to create our attitude measures in a way that will be engaging and valid, (i.e. having a form of semantic differential rather than typical questionnaire) and we demonstrated excellent reliability of our ‘current’ vs. ‘ideal’ measures, future studies might benefit from a better situated, ethnographical, and observational studies. What seems to be particularly worthwhile to consider are observational studies, including dynamic diaries conducted in-class. Such more naturalistic measures could provide even more meaningful data about the reasons for students’ attitudes towards religious education.

Conclusion

In this article, we sought to explore students’ attitudes regarding participation in religion classes and explanations of the purpose of religious education as provided by secondary school students. Our study demonstrated that students perceived religious education as highly conservative and called for a more dialogical and liberal religious education, with this effect being strongest among high school students. Importantly, students’ hermeneutical rationality was the primary variable associated with their lack of satisfaction with the current state of religious education and postulates to change into a more dialogical one.

From the vantage point of the history of ideas, the primacy of praxeological rationality can lead to totalitarian social changes (Horkheimer and Adorno Citation1994; Milerski Citation2019). From the perspective of the analysis of contemporary educational policies, one must state that measurable effects have become the principles of these policies. This approach is supported by the dominance of praxeological rationality diagnosed among students. In our opinion, the school is faced with a choice: it either accepts utilitarianism or it dares to educate holistically (Adorno Citation1956).

Data availability

The dataset used in this study is available in the OSF Archive: https://osf.io/s8fdt/?view_only=e11fcef6704b470d952fb79026e81b30

Funding

This article was supported by a grant from the National Science Center Poland [NCN, Narodowe Centrum Nauki 2016/23/B/HS6/03898].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bogusław Milerski

Bogusław Milerski, Ph.D., Associate Professor of religious and culture education, Department of Social Sciences, Christian Theological Academy in Warsaw (Poland); [email protected]

Maciej Karwowski

Maciej Karwowski, Ph.D., Associate Professor of educational psychology and theory of creative education, University in Wrocław; [email protected]

References

- Adorno, T. W. 1956. “Theorie der Halbbildung.” In Gesammelte Schriften, edited by T. W. Adorno, 93–121. Vol. 8. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Berger, P. L. 1980. Der Zwang zur Häresie. Religion in der pluralistischen Gesellschaft. Frankfurt/M: S. Fischer.

- Bevan, R. 2009. “Expanding Rationality: The Relation between Epistemic Virtue and Critical Thinking.” Educational Theory 59 (2): 167–179. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5446.2009.00312.x.

- Boschki, R. 2008. Einführung in die Religionspädagogik. Darmstadt: WBG.

- Bourdieu, P., and J.-C. Passeron. 1990. Reprodukcja. Elementy teorii systemu nauczania. Warszawa: PWN.

- CBOS (Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej = Public Opinion Research Center). 2020a. “Religijność Polaków w ostatnich 20 latach. Komunikat z badań.” Warsaw: CBOS. Accessed 4 January 2021. www.cbos.pl

- CBOS (Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej = Public Opinion Research Center). 2020b. “Religijność Polaków w warunkach pandemii.” Komunikat z badań. Warsaw: CBOS. Accessed 4 January 2021. www.cbos.pl

- Cohen, J. 1992. “A Power Primer.” Psychological Bulletin 112: 155–159. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

- Cush, D. 2021. “Changing the Game in English Religious Education: 1971 and 2018.” In Religious Education in a Post-Secular Age. Case Studies from Europe, edited by F. Olof and P. Thalen, 139–156. Switzerland: Springer - Palgrave Macmilan.

- Danner, H. 1998. Methoden geisteswissenschaftlicher Pädagogik. Einführung in Hermeneutik, Phänomenologie und Dialektik. München, Basel: Ernst Reinhardt Verlag.

- Dewey, J. 1903. “Religious Education as Conditioned by Modern Psychology and Pedagogy.” The Religious Education Association: Proceedings of the First Convention, Chicago: Religious Education Association, 60–66. Historical REA Articles, Accessed 4 January 2021. www.old.religiouseducation.net

- Diller, C., and P. Gareis. 2020. “Secularisation, Religious Denominations, and Differences in Regional Characteristics: The State of Research and a Regional Statistical Investigation for Germany.” Religions 11 (12): 657. doi:10.3390/rel11120657.

- Dressler, B. 2009. “Die pragmatische Vernunft der Bildung.” In Religion, Rationalität und Bildung, edited by M. Meyer-Blanck and S. Schmidt, 19–30. Würzburg: Ergon Verlag.

- EKD (Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland). 2020. Religiöse Bildung angesichts von Konfessionslosigkeit. Aufgaben und Chancen. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt.

- Franck, O., and P. Thalén, eds. 2021. Religious Education in a Post-Secular Age. Case Studies from Europe. Switzerland: Springer - Palgrave Macmilan.

- Giroux, H., and L. Witkowski. 2010. Edukacja i sfera publiczna [Education and the Public Aera]. Kraków: Impuls.

- Habermas, J. 1973. Erkenntnis und Interesse. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Habermas, J. 1988. Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns. Vols. 1–2. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Horkheimer, M., and T. Adorno. 1994. Dialektyka oświecenia. Fragmenty filozoficzne [Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical Fragments]. Warszawa: IFIS PAN.

- Horkheimer, M. 2011. Traditionelle und kritische Theorie. Fünf Aufsätze. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag.

- Hull, J. 1984. Studies in Religion and Education. London, New York: Falmer Press.

- ISKK. 2020. “Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia AD 2020.” In edited by W. Sadłoń and L. Organek. Warszawa: Instytut Statystyki Kościoła Katolickiego SAC.

- Jackson, R. 1997. Religious Education an Interpretative Approach. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Jenks, C., ed. 2012. Rationality, Education and the Social Organization of Knowledge. Papers for a Reflective Sociology of Education. London: Routledge.

- Karwowski, M., and B. Milerski. 2021. “Educational Rationality: Measurement, Correlates, and Consequences.” Education Sciences 11 (4): 182. doi:10.3390/educsci11040182.

- Kittelmann Flensner, K. 2017. Discourses of Religion and Secularism in Religious Education Classrooms. Cham: Springer International.

- Luckmann, T. 1991. Die unsichtbare Religion. Frankfurt/M: Suhrkamp.

- Marek, Z., and A. Walulik (eds.). 2020. “Religious Pedagogy.” Social Dictionaries. Krakow: Ignatianum University Press.

- Mariański, J. 2004. Religijność społeczeństwa polskiego w perspektywie europejskiej. Próba syntezy socjologicznej. Kraków: Nomos.

- McLaren, P. 2015. Życie w szkołach. Wprowadzenie do pedagogiki krytycznej. Wrocław: DSW. [original edition: Life in Schools: An Introduction to Critical Pedagogy in the Foundations of Education, Boulder 2014].

- Milerski, B., and M. Karwowski. 2016. Racjonalność procesu kształcenia. Teoria i badanie [Rationality of Education. Theory and Research]. Kraków: Impuls.

- Milerski, B. 2019. “Antisemitismus und praxeologische Rationalität als religionspädagogische Herausforderung am Beispiel von Polen.” Theo-Web. Zeitschrift für Religionspädagogik. Academic Journal of Religious Education 18 (1): 93–104.

- Milerski, B. 2021. “Konfessionslosigkeit als Herausforderung für den religionspädagogischen Diskurs in Polen.” Theo-Web. Zeitschrift für Religionspädagogik. Academic Journal of Religious Education 20 (1): 83–93.

- Mollenhauer, K. 1968. Erziehung und Emanzipation. München: Juventa Verlag.

- Oevermann, U. 1981. “Fallrekonstruktionen und Strukturgeneralisierung als Beitrag der Objektiven Hermeneutik.” www.publikationen.ub.uni-franfurt.de

- Oevermann, U. 2002. “Klinische Soziologie auf der Basis der Methodologie der objektiven Hermeneutik - Manifest der objektiv hermeneutischen Sozialforschung.” www.ihsk.de

- Rittelmeyer, C., and M. Parmentier. 2001. Einführung in die pädagogische Hermeneutik. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Rothgangel, M. 2014. Religionspädagogik im Dialog I. Disziplinäre und interdisziplinäre Grenzgänge. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag.

- Schlag, T. 2010. Horizonte demokratischer Bildung. Evangelische Religionspädagogik in politischer Perspektive. Freiburg, Basel, Wien: Herder Verlag.

- Schweitzer, F., and H. Simojoki. 2005. Moderne Religionspädagogik. Ihre Entwicklung und Identität. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlag.

- Statistic Poland. 2020. Rocznik statystyczny Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Statistcal Yearbook of the Republic of Poland. Warsaw: GUS.

- Wernet, A. 2006. Hermeneutik - Kasuistik – Fallverstehen. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.