ABSTRACT

A contentious issue in the Israel-Palestine conflict is the ongoing construction of settlements in the occupied West Bank along with its related policies, both of which have had impacts on the lives of resident Palestinians. These impacts have been documented by various UN and non-governmental agencies yet have been insufficiently studied in the academic literature. This article aims to review the literature on the social determinants of health for West Bank Palestinians and understand how settlement construction and policy influence these determinants. To accomplish these aims, the article first includes an analysis of how military infrastructure, resource allocation, land appropriation and house demolition related to the settlements influence the lives of West Bank Palestinians. The article then proceeds to review available literature on the social determinants of health in the West Bank, most notably: access to healthcare, exposure to political violence, economic conditions and water contamination, with the goal of understanding how settlement-related policies are related to these social determinants of health.

Introduction

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is characterized by a violent history and complex political disputes over borders, Jerusalem, the right of return of refugees, the Gaza Strip blockade, distribution of resources, and the West Bank settlements. For political, economic, ideological, and religious reasons there is no straightforward solution to the conflict, and likely no solution that will satisfy all Israelis and Palestinians. With the aim of contributing to an expanding body of literature that recognizes how, in the midst of this protracted conflict, the health and well-being of individuals is utterly ignored, this article focuses on the impact that Israeli settlement-building in the West Bank has had on the health and well-being of Palestinians. It does so by analysing the conditions under which settlements are built, the resulting security and resource infrastructure that accompanies these settlements, and the consequent impact on various social determinants of health for Palestinians in the West Bank. The section below will briefly elaborate on Israeli settlement policy in the context of key events of the conflict.

Israeli settlement construction and related policies in the West Bank

The history of Israeli settlement construction in the occupied Palestinian Territories (oPT) begins following the June 1967 Arab-Israeli war and the subsequent Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip (UNOCHA Citation2007). Since 1967, Israeli governments have taken various measures to establish and consolidate West Bank settlements, including:

(a) building infrastructure; (b) encouraging Jewish migrants to Israel to move to settlements; (c) sponsoring economic activities; (d) supporting settlements through public services delivery and development projects; and (e) seizing Palestinian land, some privately owned, requisitioning land for ‘military needs’, declaring or registering land as ‘State land’ and expropriating land for ‘public needs’ (UNHRC Citation2013).

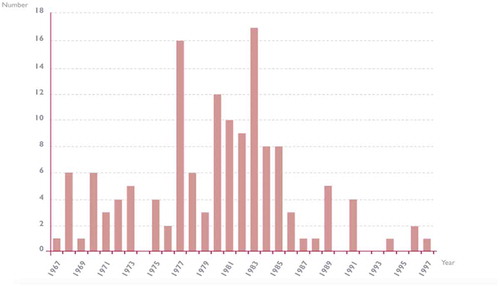

Every government since 1967 has contributed to the planning, construction, development and/or expansion of settlements in the West Bank, despite being illegal under the 4th Geneva Convention, which Israel is party to (Berger Citation2018; Lein Citation2002; UNHRC Citation2013; UNOCHA Citation2007) ().

Figure 1. History of Israeli settlement construction (1967–1997): year and number of new Israeli settlements in the West Bank. From: the Humanitarian Impact on Palestinians of Israeli Settlements and Other Infrastructure in the West Bank, by the United Nations – Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), ©2007 United Nations. Used with the permission of the United Nations.

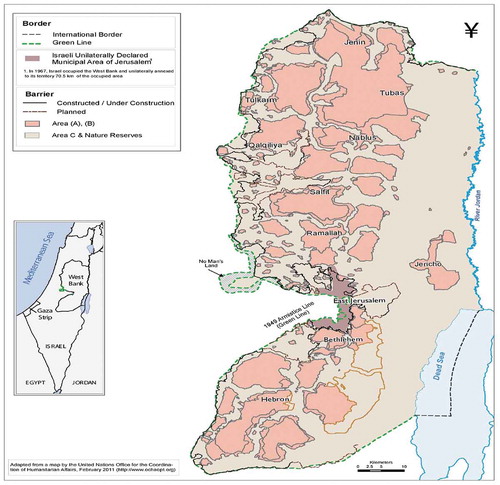

In September 1993, the Declaration of Principles, also known as the Oslo Accords, was signed between the Israeli government and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), transferring sovereignty of a small part of the West Bank to the Palestinian representative body (Lein Citation2002). shows a map of the administrative boundaries that resulted from the Oslo Accords. Area A is under full Palestinian administration (18% of the West Bank); Area B is under Palestinian civil and Israeli security administration (22% of the West Bank); and Area C is under full Israeli administration (60% of the West Bank) (UNHRC Citation2013) ().

Figure 2. Map of the West Bank and its administrative regions under the Oslo Accords of 1993. From area C, by the Palestinian academic society for the study of international affairs, © PASSIA.

In the period following the Oslo Accords, the number of new settlements decreased, and Israel made a commitment to halt settlement-building outside the Jordan Valley and Greater Jerusalem area (Lein Citation2002) (). During this time, the Israeli government expanded existing settlements by approving thousands of new housing units and offering financial incentives to Israeli migrants to move to the West Bank (Lein Citation2002), leading to a 65% increase in the settler population between 1993–2004 (UNOCHA Citation2007). By 2012, 250 settlements had been established in the West Bank, with a population of about 520,000, including 200,000 in East Jerusalem (UNHRC Citation2013). Since 2009, government spending on the consolidation and expansion of settlements has increased significantly (UNHRC Citation2013) along with the number of new housing units under construction (Fulbright Citation2017).

Materials and methods

This article consists of two parts. The first reviews the available literature on the short- and long-term impact of Israeli settlement-building and related policies on the daily lives of West Bank Palestinians. This section primarily reviews reports published by United Nations (UN) agencies and analyses by the World Bank and World Health Organization that have documented various health, economic, and social impacts of occupation-related policies on the West Bank. The second section is a review of the literature on the social determinants of health of West Bank Palestinians. While the first section will undoubtedly identify social, economic, and political factors that are known to influence health, the purpose of the literature review in the second section is to identify primary studies that examine health outcomes in the West Bank, in order to provide a snapshot of the state of current literature and gaps that are present. Following a search using relevant MeSH terms and keywords in Ovid Medline and Embase, title and abstract screening produced 163 articles for full-text review. Inclusion criteria were primary studies examining how one or more social factors influence health outcome(s) in the West Bank and 27 articles were identified.

The goal of the discussion is to synthesize the two sections of the paper and identify direct and indirect links between Israeli settlement policy and the social determinants of health for West Bank Palestinians.

Results

Section 1: the impact of Israeli settlements and related policies on life in the West Bank

Military infrastructure and mobility restrictions

The military infrastructure that supports the Israeli settlements in the West Bank includes the separation wall, military bases, firing zones, closed military areas, and checkpoints (UNOCHA Citation2007). In addition to this infrastructure, a road network connecting the settlements to each other and to the State of Israel runs throughout the West Bank (UNOCHA Citation2007). Use of these roads by Palestinians is restricted by checkpoints, roadblocks, and a system of permits (UNOCHA Citation2007). A spatial analysis study from The Hebrew University used geographical data to show that the settlements form a contiguous community that is both gated and separated from the surrounding Palestinian community, but also acts as a gating community that forms small ‘islands’ of Palestinian land by separating and dividing them from each other (Handel Citation2014). The author highlights that although the ‘built-up’ areas in the settlements take up only 2% of the West Bank, the total area occupied by the settlement complex, through their location, spatial organization, interconnected network of roads, and surrounding military structures amounts to 42% of the West Bank (Handel Citation2014). The subsections below describe the consequences of this fragmentation on various health determinants, including access to healthcare, the economy, and the exposure of Palestinians to political violence by the military and settlers.

Access to healthcare

A consequence of the West Bank’s fragmentation are the barriers to delivery of health services due to travel limitations for patients and providers and restrictions on transport of medical supplies (Pourgourides Citation1999). A Geographical Informations Systems study used data on travel times, checkpoints, and distances to general hospitals to study accessibility of health services, and concluded that those most affected often lived in governorates with no general hospital (Salfit and Tubas) and in rural areas (Eklund and Mårtensson Citation2012). These individuals can face major travel delays due to the presence of checkpoints separating them from communities with a general hospital (Eklund and Mårtensson Citation2012). While individuals in major urban areas have less issues accessing primary care, access to tertiary care or referral hospitals – located primarily in East Jerusalem – is much more restricted due to the permits needed to enter the city (UNOCHA Citation2007).

Following the Second Intifada (2000–2005), increased restrictions on mobility led to significantly impaired access to sexual and reproductive health services for women, limiting the supply of drugs, contraceptives, and medical equipment (Bosmans et al. Citation2008). These restrictions led to an increase in pre-term births, reduced hospital births, an increased need for caesarean sections, and reduced use of post-natal care (Bosmans et al. Citation2008). Moreover, there were increased reports of births, stillbirths and cases of maternal mortality at checkpoints due to denial of passage to reach hospitals (Bosmans et al. Citation2008). These findings are contrary to the requirements of the occupying power to ensure the well-being of the civilian population under occupation (Stefanini and Ziv Citation2004).

Economic impacts

In 2012, a United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) fact-finding mission to determine the implications of illegal Israeli settlements for Palestinians’ rights in the oPT (UNHRC Citation2013) found that restriction to movement directly related to the settlements (i.e. settler-only roads, checkpoints, closures, and permit systems that improve connectivity between the settlements and the State of Israel) directly limit access for Palestinians to their agricultural land, ultimately reducing their ability to work and earn income (UNHRC Citation2013). The mission notes particular economic pressures on the city of Hebron and the Jordan Valley region, where the permit system, obstacles to movement, and off-limit areas that facilitate movement for Israeli settlers in Hebron and Kiryat Arba, all limit movement for Palestinians, leading to hundreds of Palestinian business closures due to limited access for customers and suppliers, in addition to several hundred more due to Israeli military order (UNHRC Citation2013). An economic analysis of labour flows in the West Bank examined the impact of mobility restrictions – such as ID/permit status and checkpoints/border closures – on economic outcomes by analysing the number of comprehensive closure days and closure obstacles per day from 2000 until 2008. The author found that increased closures significantly increased the odds of unemployment, particularly for those who live outside of Jerusalem and do not have a Jerusalem ID (Adnan Citation2015). Moreover, the author showed that for an increase in closures days by one standard deviation during a quarter, the economic loss for the next quarter would be $1 million USD per day (Adnan Citation2015). A separate analysis by the World Bank concluded that the economic and mobility restrictions imposed in Area C of the West Bank are the ‘most significant impediment to the Palestinian private sector growth’, with their limitations on the movement of people and goods within, into, and out of the oPT, justified by the occupying power in order to protect Israeli citizens residing in these territories (World Bank Citation2013).

Exposure to political violence

Finally a further consequence of the presence of Israeli military infrastructure in the West Bank is the heightened exposure of Palestinians to political violence through interactions with the Israeli Defence Force (IDF); this is combined with exposure to violence instigated by settlers. Authors studying the impacts of political violence in the oPT define political violence broadly as the exposure to checkpoints; loss of land, family or income; barriers to travel and daily living; experiencing or witnessing arrest, detainment, or shootings; house demolitions, strip-searches, beatings, and other forms of humiliation (Sousa Citation2013; Giacaman et al. Citation2007b). The UNHRC mission finds that Palestinians are routinely subjected to arbitrary arrests and detention by the Israeli military, and that many of those detained are children. Children face violations of their rights to fair trial through ‘interrogation, arbitrary detention and abuse, trial and sentencing’ that pressures 90% of children to plead guilty whether or not the offence was committed, as serving the sentence is the fastest way out of the system (UNHRC Citation2013).

Beyond exposure to violence as a result of the Israeli military, there are numerous reports of violence instigated by Israeli settlers targetting Palestinians and their property (UNHRC Citation2013; UNOCHA Citation2007; B’Tselem Citation2018; UNOCHA Citation2008). The UNHRC mission noted evidence of attacks on individuals and property, intimidation that obstructed access to water resources and children’s schooling, and the use of various weapons as well as shootings. In a one-year period between 2011 and 2012, 147 Palestinians were injured as a result of settler violence, including 34 children (UNHRC Citation2013). Limiting access of Palestinian farmers to their land through violence and intimidation, as well as the burning and uprooting of crops, and appropriation of agricultural land, has also imposed an economic burden on Palestinians’ livelihoods, particularly disrupting the olive industry (UNHRC Citation2013). In 1994, following the murder of Palestinians at a Hebron mosque, UN resolution 904 called upon Israel ‘to continue to take and implement measures, including, inter alia, confiscation of arms, with the aim of preventing illegal acts of violence by Israeli settlers’ (UNOCHA Citation2007). However, settler violence continues to be a source of exposure to violence for Palestinians in the West Bank (B’Tselem Citation2018).

Water resource allocation and waste management

Settlement communities, especially those dependent on agriculture, require an extensive water supply – a limited resource in the West Bank. In the year 2000, 215,000 Palestinians living in over 150 villages had no water supply network and were forced to share water resources with other municipalities (UN ECOSOC Citation2001). During this period, water consumption in the West Bank was 40 litres per person per day, less than the WHO recommended minimum (UNOCHA Citation2007). While an estimated 390,000 Israeli settlers used up 592,000 litres of water, an estimated 3 million Palestinians used only 114,500 litres (UN ECOSOC Citation2001). This constitutes Israel using up 80% of West Bank water resources for Israeli citizens (UN ECOSOC Citation2001), a figure cited at 90% in 2009 (UNHRC Citation2013). Moreover, due to restrictions imposed on movement and commerce in Area C of the West Bank, most Palestinian water projects are rejected, leaving the water supply fragmented and particularly limited for Palestinians in Area C (UNHRC Citation2013). The UN mission also reports increased destruction of Palestinian water infrastructure by Israeli authorities since 2010 in areas planned for settlement expansion, often leading to the displacement of Palestinian communities that rely on this water for agriculture (UNHRC Citation2013).

Finally, a related issue is the problem of waste management in the West Bank and the transfer of untreated sewage and/or waste from Israeli settlements and the State of Israel to Palestinian land (Hartling Citation2002; Abdel-Qader and Roberts-Davis Citation2018). The UN General Assembly (UNGA) has adopted numerous resolutions that call upon Israel to:

“[halt] all actions, including those perpetrated by Israeli settlers, harming the environment, including the dumping of all kinds of waste materials, in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and in the occupied Syrian Golan, which gravely threaten their natural resources, namely water and land resources, and which pose an environmental, sanitation and health threat to the civilian populations” (United Nations General Assembly Citation2013; Abdel-Qader and Roberts-Davis Citation2018).

Waste products from the Israeli settlements and the State of Israel come from various manufacturing industries, including those related to agriculture and the military, as well as medical and recycling plant waste (Abdel-Qader and Roberts-Davis Citation2018). The potential downstream effects of these waste products is exemplified by a study showing significant differences between levels of DNA damage – a risk factor for cancer – for individuals sampled from the Palestinian village of Bruqeen, a dump site for the Barqan Israeli industrial settlement, compared to Palestinians from Bethlehem (Hammad and Qumsiyeh Citation2013).

Land appropriation and house demolition

Key to the ongoing construction and expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank are land resources, used for building the settlement infrastructure and as agricultural and/or industrial land that supports their sustenance. Settlement construction has often occurred on the land of Palestinian villages or agricultural communities (UNHRC Citation2013). Land appropriation is justified through a number of mechanisms, including military seizures and the declaration of Israeli State land, displacing Palestinians from their homes through house demolitions and forced evictions (UNHRC Citation2013). Seized land is repurposed for settlement building or expansion by granting jurisdiction of the land to settlement councils, in particular to consolidate settlement communities (UNHRC Citation2013). A further mechanism by which land is appropriated is the harsh system of building permits required for Palestinians to build new homes, with an approval rate of 2.3% between 2009–2012 according to Israeli Civil Administration data, a period during which 927 Palestinian homes were demolished (Ryan Citation2017). Due to this sytem, Palestinians are either left without a home or forced to build houses without a permit, risking demolition and displacement (UNHRC Citation2013), and creating insecurity that disproportionately affects women in Palestinian society (Ryan Citation2017). Areas at high risk of demolition are often food insecure with limited access to other essential needs and services (Save the Children UK Citation2009).

Finally, the West Bank barrier, which began construction in 2002 and separates the West Bank from the State of Israel, does not run along the 1949 armistice line (‘the green line’), but rather cuts deep into the West Bank villages and agricultural land and when completed, would isolate approximately 10% of the land in the West Bank (UNOCHA Citation2013). In 2013, the area between the green line and the barrier included 85% of the settler population, 11,000 Palestinians with restricted access to their workplaces and essential services, and the agricultural land for thousands of Palestinians (UNOCHA Citation2013).

Section 2: social determinants of health in the West Bank

Access to healthcare

A series of studies on maternal mortality in the oPT found that 69% of the deaths recorded in the study period were avoidable, and that 15% of the deceased women of reproductive age died due to injuries or accidents, including 1.9% of which were due to alleged Israeli gunfire (Al-Adili, Johansson, and Bergström Citation2006; Al-Adili et al. Citation2008). In a study describing stillbirths and neonatal deaths in the oPT, 10% of the 112 deliveries that resulted in death were linked to constraints on care imposed by Israeli checkpoints (Kalter et al. Citation2008).

Political violence and mental health

A study on the prevalence of psychological morbidity in West Bank rural villages found that 42% of children suffered from emotional or behavioural psychopathology prior to the violence of the Second Intifada (Zakrison et al. Citation2004). The authors suggest that the high psychological morbidity in a period of relatively low violence may be attributed to the anticipation of violence in the context of Israeli settlement encroachment (Zakrison et al. Citation2004), a concept supported in an earlier study (Thabet, Abed, and Vostanis Citation2002). Numerous studies have demonstrated a significant association between exposure to political violence in adolescents and severe negative impacts on mental health, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and depression (Al-Krenawi, Graham, and Sehwail Citation2007; Giacaman et al. Citation2007a), with a disproportionate burden on girls and on refugees (Giacaman et al. Citation2007b), and additional associations with functional impairment in school (Abdeen, Qasrawi, and Nabil Citation2008), reduced family and social functioning as well as increased aggression (Al-Krenawi and Graham Citation2012). Both lifetime and 30-day exposure to political violence were positively correlated with PTSD symptoms in women (Sousa Citation2013), and the odds of intimate partner violence were found to significantly increase when the husbands of affected women have been directly and indirectly exposed to political violence (Clark et al. Citation2010).

In a 2010 study, authors found that in addition to the relationship between political violence/socio-political stressors and psychological morbidity found in previous studies, PTSD and major depression were consistently associated with psychological resource loss, defined as loss of social or personal resources (Canetti et al. Citation2010). A later study found that exposure to violence and both psychological and material resource loss were predictors of more serious PTSD and symptoms of depression that were less likely to improve (Hobfoll et al. Citation2011). This research was later extended to examine the effects of political violence/socio-political stressors on physical health. Trauma exposure, loss of social support, and psychological resource loss, through their effects on symptoms of depression and PTSD, negatively impacted self-reported health, and economic resource loss directly impacted self-reported health (Hobfoll, Hall, and Canetti Citation2012). Analysis from a further study on this relationship strongly suggests that psychosocial resource loss due to the occupation predicts psychological distress symptoms, which then leads to further psychosocial resource loss, known as a loss spiral (Heath et al. Citation2012).

Long-term effects of political violence

A study on the effects of political violence in the West Bank was conducted by assessing mental health burden and its association with retrospective reports of violence 7–12 years earlier (Haj-Yahia Citation2008). The study indicated a significant association between retrospective reports of violence and various psychological symptoms. The study also showed that social determinants such as parents’ low education levels, poor standards of living, refugee status, and low socioeconomic status were risk factors for these psychological symptoms (Haj-Yahia Citation2008). A longitudinal study over a 25-year period (1987–2011) examined the effects of annually documented exposure to political violence in the oPT and found that 12% of study participants living in areas with a higher relative presence of Israeli military reported high levels of sustained humiliation in addition to having significantly lower health, economic, political, and psychological functioning compared to other study participants that only intermittently experienced political violence (Barber et al. Citation2016). A study on the broader impacts of political conflict as a health determinant through its effects on the economic and living conditions in Palestinian society examined how land confiscation, permit denials, restricted movement, access to electricity, and issues at checkpoints, can impact PTSD, depression, health-related limitations on an individuals functioning, and emotional exhaustion. The authors conclude that beyond the well-studied impacts of conflict-related violence on PTSD and depression, the economic burden of the conflict and the associated human insecurity also impact various other measures of health (McNeely et al. Citation2014).

Socioeconomic factors

A study of adolescents in the West Bank delineates the links between socioeconomic factors such as food availability, standards of living, education and income with obesity, overweight, underweight, and stunting (Mikki et al. Citation2009). The prevalence of these conditions and their links with sociodemographic factors varied across gender and region (Hebron vs Ramallah) but highlight a clear link between the health status of Palestinians and their daily living conditions (Mikki et al. Citation2009).

A multi-country study on infants born small for their gestational age (SGA) found that among 29 countries in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and Asia, the oPT had the third highest prevalence of SGA for term and preterm infants (Ota et al. Citation2014). SGA increases an infant’s risk for chronic diseases later in life and SGA infants are at a higher risk of mortality than appropriate for gestational age (AGA) infants. While preterm SGA was associated primarily with the medical condition of the mother, term SGA was found to be associated with sociodemographic factors and malnutrition, suggesting a role for these factors in the high prevalence of SGA in the oPT (Ota et al. Citation2014). A separate study on the determinants of birthweight in the oPT found that the primary determinants of birthweight are biological factors, while social and environmental factors play a smaller role (Halileh et al. Citation2008). However, a study in the oPT on the determinants of stunting found that other than age and birthweight, socioeconomic status and level of food insecurity were the factors most strongly associated with stunting (Gordon and Halileh Citation2013). Food insecurity in particular, when controlled for other variables, was shown to be directly associated with stunting among children less than 5 years of age (Gordon and Halileh Citation2013).

In a study on the prevalence of anaemia in adolescents, low standard of living was associated with higher levels of anaemia for boys in Hebron (22.5% prevalence) which was signigicantly higher than in Ramallah (6%) which is associated with higher living standards (Mikki et al. Citation2011). Interestingly, the prevalence for girls was similar at 9.2% and 9.3% respectively. The authors also found that the prevalence of anaemia was significantly higher among boys that suffered from stunting or were underweight (Mikki et al. Citation2011). As well as gender and family size, socioeconomic deprivation is associated with an increased prevalence of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among Palestinians in the occupied territories (Thabet et al. Citation2010).

An epidemiological study of Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) data found that individuals who had never attended school were 2–4 times more likely to have cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, diabetes, and cancer (Abukhdeir et al. Citation2013). Unemployed individuals, as well as those who were divorced, separated, or widowed, were significantly more likely to have these four diseases. Refugee status and age were also important risk factors for chronic diseases, while certain factors such as being a full-time student and living in a rural setting were protective for various chronic diseases (Abukhdeir et al. Citation2013).

Water contamination

A study conducted between 1999–2003 showed worsening conditions of water contamination in the West Bank, with 20.4% of samples contaminated, as well as high levels of chlorine and nitrates (Mourad et al. Citation2008). By 2004, 25% of food samples were contaminated by chemical or biological agents and food poisoning had risen by 22% since 1999 (Mourad et al. Citation2008). A pilot study on blood lead levels among Palestinian schoolchildren in Nablus found that most children had levels comparable to neighbouring countries, but that 4.5% had levels that call for public health interventions based on the CDC recommendations (Sawalha et al. Citation2013). Moreover, lead levels were significantly higher among children in refugee camps near industrial areas compared to those in residential areas (Sawalha et al. Citation2013).

Discussion

Settlement construction and associated policies have several downstream consequences that impact various aspects of life in the West Bank, including mobility restrictions; employment; economic well-being; access to healthcare, clean water, housing and agricultural land; and exposure to political violence. In light of the results presented above, the direct and indirect links between the social health determinants of Palestinians and Israeli settlement policy will be discussed below.

Health determinants linked to the settlements

Section one presented evidence of the direct impacts of settlement construction and related policies on the socioeconomic conditions in the West Bank, through their association with demolitions and lost agricultural land, restrictions on water resources, as well as the downstream effects of mobility restrictions on employment and trade. The resulting poor socioeconomic conditions have been shown, in section two, to be major health determinants in the oPT, in particular on the health and developmental status of children and adolescents, but also their association with chronic diseases. Political violence, a side effect of the security infrastructure that protects Israeli settlers in the West Bank, has been shown to be a major determinant of mental health for Palestinian children, adolescents and adults. Moreover, the literature suggests that access to healthcare as a health determinant was particularly critical for the health of pregnant women and their feti, with several studies citing mobility restrictions as the primary barrier to accessing care. Finally, water contamination in the West Bank, to which a major contributor is the channelling of waste from the State of Israel and the settlements, has been shown to pose a major risk for food poisoning and potential lead poisoning.

Health determinants unrelated to the settlements

It is important to acknowledge that Israeli settlements and related policies are not the sole causes of poor access to healthcare, poor socioeconomic conditions, exposure to political violence, and water contamination. While settlements are important contributors to these conditions, various other factors beyond the scope of this article, such as governance at various levels, trade and relationships with surrounding countries, and other side effects of the conflict also play a role. In particular, various limitations in the healthcare system place significant financial burden on low-income patients and hinder access to health services (Abu-Zaineh et al. Citation2011; Mataria et al. Citation2010), particularly for those with a disability (Nahal et al. Citation2017; Dababnah and Bulson Citation2015; Hamdan and Al-Akhras Citation2009). It is also important to view the oPT in light of its colonial history and the chronic conditions of conflict and occupation that have shaped its development and impacted various aspects of people’s everyday lives. Giacaman, Abdul-Rahim, and Wick argue that solutions and reform strategies that attempt to address technical efficiencies, governance, and resource issues in the context of the healthcare system, for example, have led to wasted investments that do not get at the heart and scope of the issues in the occupied territories (Giacaman, Abdul-Rahim, and Wick Citation2003).

Future directions

This article focuses on the social determinants of health for Palestinians in the West Bank and should be viewed in the context of the literature on biological, cultural, and individual health determinants of the Palestinian population to obtain a more comprehensive picture of causal and underlying factors that affect health outcomes (Husseini, Khatib, and Abu-Rmeileh Citation2008; Assaf and Khawaja Citation2009). The review in section two identifies gaps in the literature on Palestinian social determinants of health. Though numerous studies identify limitations on access to heatlhcare in the West Bank, surprisingly few studies examine the health impacts of these limitations. Moreover, though chronic, non-communicable diseases are the major causes of death in the oPT, very few studies examined the determinants and risk factors for chronic diseases in this population. Finally, a small number of studies examined the effects of water contamination on the health of Palestinians, with no recent studies assessing the links to infectious disease, and no nationwide studies available to provide comprehensive data. Beyond contributing to the gaps in the health determinants literature, future goals of the health science community should be to solidify our understanding of how these determinants come about, and what role they can play in contributing to the improved health of individuals living under these conditions.

Finally, a major limitation of this article is that it does not discuss the Gaza Strip. The Gaza Strip has one of the highest unemployment rates in the world, an extremely limited clean water supply, and poor access to healthcare for its population (UNCTD Citation2015; Giacaman et al. Citation2009) – factors which have been reliably shown to predict negative health outcomes (Marmot et al. Citation2008). While these same factors are important in the discussion of health and social determinants in the West Bank, the land, air, and sea blockade of the Gaza Strip makes its situation gravely unique, and one that has been described as ‘unliveable’ by the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in the oPT (UNGA Citation2018). An important future direction is to extend the discussion of social determinants of health in the context of occupation to the Gaza Strip in order to shed light on the available literature and guide future research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Harry Shannon and Laura Banfield for their support during the early stages of organizing and outlining this review. We would also like to thank the students and faculty in the MSc Global Health programme at McMaster for their feedback on the oral presentaton of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Khalid Fahoum

Khalid Fahoum is a medical student at Weill Cornell Medical College with primary research interests in the social determinants of health and how they disproportionately impact vulnerable communities locally and abroad. His experience ranges from basic to clinical research at the undergraduate, graduate, and medical school level. During his MS in Global Health, his research focused on the social determinants of health for West Bank Palestinians and his work in large part is published in this paper. At the medical school level, his research has focused on alcohol-related liver disease with the goal of exploring how social determinants can be prioritized to a greater extent in clinical decision-making.

Izzeldin Abuelaish

Dr. Izzeldin Abuelaish is a Palestinian Canadian physician and an internationally recognized human rights and inspirational peace activist devoted to advancing health and education opportunities for women and girls in the Middle East, through both his research and his charitable organization: The Daughters for Life Foundation. He has dedicated his life to using health as a vehicle for peace, and, despite all odds, succeeded, aided by a great determination of spirit, strong faith, and a stalwart belief in hope and family. He is a man who walks the walk and who leads by example. Dr. Abuelaish has been nominated five times for the Nobel peace Prize, and he is fondly known as Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Ghandi and the “Martin Luther King of the Middle East”, having dedicated his life to using health as a vehicle for peace. Dr. Abuelaish’s impact on peace-seeking communities is exceptional. He is an internationally-renowned speaker, having spoken at the Canadian House of Commons, the American Congress, the Chilean Senate and Parliament, the European Parliament at Place Du Luxembourg in Brussels, the State Department, Forum 2000 in Prague, and many more. Dr. Abuelaish has also spoken at academic institutions and organizations in Canada, the United States, Europe, Africa, and Australia and Asia. Currently, Dr. Abuelaish is an associate professor at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto. He remains deeply committed to his humanitarian activism in addition to his roles as a charity leader and inspirational educator.

References

- Abdeen, Z., R. Qasrawi, and S. Nabil. 2008. “Psychological Reactions to Israeli Occupation: Findings from the National Study of School-Based Screening in Palestine.” International Journal of Behavioral Development 32 (4): 290–297. doi:10.1177/0165025408092220.

- Abdel-Qader, S., and T. L. Roberts-Davis. 2018. “Toxic Occupation: Leveraging the Basel Convention in Palestine.” Journal of Palestine Studies 47 (2): 28–43. doi:10.1525/jps.2018.47.2.28.

- Abukhdeir, H. F., L. S. Caplan, L. Reese, and E. Alema-Mensah. 2013. “Factors Affecting the Prevalence of Chronic Diseases in Palestinian People: An Analysis of Data from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 19 (4): 307–313. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.021.Secreted.

- Abu-Zaineh, M., A. Mataria, J. P. Moatti, and B. Ventelou. 2011. “Measuring and Decomposing Socioeconomic Inequality in Healthcare Delivery: A Microsimulation Approach with Application to the Palestinian Conflict-Affected Fragile Setting.” Social Science and Medicine 72 (2): 133–141. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.018.

- Adnan, W. 2015. “Who Gets to Cross the Border? The Impact of Mobility Restrictions on Labor Flows in the West Bank.” Labour Economics 34: 86–99. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2015.03.016.

- Al-Adili, N., A. Johansson, and S. Bergström. 2006. “Maternal Mortality among Palestinian Women in the West Bank.” International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 93 (2): 164–170. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.11.009.

- Al-Adili, N., M. Shaheen, S. Bergström, and A. Johansson. 2008. “Deaths among Young, Single Women in 2000–2001 in the West Bank, Palestinian Occupied Territories.” Reproductive Health Matters 16 (31): 112–121. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31340-8.

- Al-Krenawi, A., and J. R. Graham. 2012. “The Impact of Political Violence on Psychosocial Functioning of Individuals and Families: The Case of Palestinian Adolescents.” Child and Adolescent Mental Health 17 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00600.x.

- Al-Krenawi, A., J. R. Graham, and M. A. Sehwail. 2007. “Tomorrow’s Players under Occupation: An Analysis of the Association of Political Violent with Psychological Functioning and Domestic Violence, among Palestinian Youth.” The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 77 (3): 427–433. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.77.3.427.

- Assaf, S., and M. Khawaja. 2009. “Consanguinity Trends and Correlates in the Palestinian Territories.” Journal of Biosocial Science 41 (1): 107–124. doi:10.1017/S0021932008002940.

- B’Tselem. 2018. “Plowing Season 2018, Ramallah District: Settler Violence Serves Israel.” https://www.btselem.org/video/20180509_settler_violence_during_plowing_season_serves_israel#full

- Barber, B. K., J. A. Clea McNeely, R. F. B. Olsen, and S. B. Doty. 2016. “Long-Term Exposure to Political Violence: The Particular Injury of Persistent Humiliation.” Social Science and Medicine 156: 154–166. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.011.

- Berger, Y. 2018. “Israel Greenlights Hundreds of New Settlement Homes in Isolated West Bank Outposts.” Haaretz, May 30.

- Bosmans, M., D. Nasser, U. Khammash, P. Claeys, and M. Temmerman. 2008. “Palestinian Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights in a Longstanding Humanitarian Crisis.” Reproductive Health Matters 16 (31): 103–111. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080%2808%2931343-3.

- Canetti, D., B. J. Sandro Galea, R. J. Hall, P. A. P. Johnson, and S. E. Hobfoll. 2010. “Exposure to Prolonged Socio-Political Conflict and the Risk of PTSD and Depression among Palestinians.” Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes 73 (3): 219–231. doi:10.1521/psyc.2010.73.3.219.

- Clark, C. J., S. A. Everson-Rose, S. F. Suglia, R. Btoush, A. Alonso, and M. M. Haj-Yahia. 2010. “Association between Exposure to Political Violence and Intimate-Partner Violence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: A Cross-Sectional Study.” The Lancet 375 (9711): 310–316. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61827-4.

- Dababnah, S., and K. Bulson. 2015. “‘on the Sidelines’: Access to Autism-Related Services in the West Bank.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 45 (12): 4124–4134. doi:10.1007/s10803-015-2538-y.

- Eklund, L., and U. Mårtensson. 2012. “Using Geographical Information Systems to Analyse Accessibility to Health Services in the West Bank, Occupied Palestinian Territory.” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 18 (8). doi:10.26719/2012.18.8.796.

- Fulbright, A. 2017. “West Bank Settlement Construction up in 2016 — Report.” Times of Israel, March 22. https://www.timesofisrael.com/west-bank-settlement-construction-up-in-2016-report/

- Giacaman, R., A. Mataria, V. Nguyen-Gillham, R. A. Safieh, A. Stefanini, and S. Chatterji. 2007a. “Quality of Life in the Palestinian Context: An Inquiry in War-like Conditions.” Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 81 (1): 68–84. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.05.011.

- Giacaman, R., H. F. Abdul-Rahim, and L. Wick. 2003. “Health Sector Reform in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT): Targeting the Forest or the Trees?” Health Policy and Planning 18 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1093/heapol/18.1.59.

- Giacaman, R., H. S. Shannon, H. Saab, N. Arya, and W. Boyce. 2007b. “Individual and Collective Exposure to Political Violence: Palestinian Adolescents Coping with Conflict.” European Journal of Public Health 17 (4): 361–368. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckl260.

- Giacaman, R., R. Khatib, L. Shabaneh, A. Ramlawi, B. Sabri, G. Sabatinelli, T. Laurance, and T. Laurance. 2009. “Health Status and Health Services in the Occupied Palestinian Territory.” The Lancet 373 (9666): 837–849. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60107-0.

- Gordon, N. H., and S. Halileh. 2013. “An Analysis of Cross Sectional Survey Data of Stunting among Palestinian Children Less than Five Years of Age.” Maternal and Child Health Journal 17 (7): 1288–1296. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1126-4.

- Haj-Yahia, M. M. 2008. “Political Violence in Retrospect: Its Effect on the Mental Health of Palestinian Adolescents.” International Journal of Behavioral Development 32 (4): 283–289. doi:10.1177/0165025408090971.

- Halileh, S., N. Abu-Rmeileh, G. Watt, N. Spencer, and N. Gordon. 2008. “Determinants of Birthweight; Gender Based Analysis.” Maternal and Child Health Journal 12 (5): 606–612. doi:10.1007/s10995-007-0226-z.

- Hamdan, M., and N. Al-Akhras. 2009. “House-to-House Survey of Disabilities in Rural Communities in the North of the West Bank.” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 15 (6): 1496–1503. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med6&NEWS=N&AN=20218143

- Hammad, K. M., and M. B. Qumsiyeh. 2013. “Genotoxic Effects of Israeli Industrial Pollutants on Residents of Bruqeen Village (salfit District, Palestine).” International Journal of Environmental Studies 70 (4): 655–662. doi:10.1080/00207233.2013.823050.

- Handel, A. 2014. “Gated/Gating Community: The Settlement Complex in the West Bank.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39 (4): 504–517. doi:10.1111/tran.2014.39.issue-4.

- Hartling, O. J. 2002. “Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Health Consequences of Israeli Settlements in Occupied Lands.” BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 324 (7333): 361. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med4&NEWS=N&AN=11841099

- Heath, N. M., B. J. Hall, E. U. Russ, D. Canetti, and S. E. Hobfoll. 2012. “Reciprocal Relationships between Resource Loss and Psychological Distress following Exposure to Political Violence: An Empirical Investigation of COR Theory’s Loss Spirals.” Anxiety, Stress and Coping 25 (6): 679–695. doi:10.1080/10615806.2011.628988.

- Hobfoll, S. E., A. D. Mancini, B. J. Hall, D. Canetti, and G. A. Bonanno. 2011. “The Limits of Resilience: Distress following Chronic Political Violence among Palestinians.” Social Science and Medicine 72 (8): 1400–1408. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.022.

- Hobfoll, S. E., B. J. Hall, and D. Canetti. 2012. “Political Violence, Psychological Distress, and Perceived Health: A Longitudinal Investigation in the Palestinian Authority.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 4 (1): 9–21. doi:10.1037/a00187439.

- Husseini, A., R. Khatib, and N. Abu-Rmeileh. 2008. “Smoking and Associated Factors in the Occupied Palestinian Territory.” April.

- Kalter, H. D., R. R. Khazen, M. Barghouthi, and M. Odeh. 2008. “Prospective Community-Based Cluster Census and Case-Control Study of Stillbirths and Neonatal Deaths in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.” Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 22 (4): 321–333. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00943.x.

- Lein, Y. 2002. “Land Grab: Israel’s Settlement Policy in the West Bank.” http://www.btselem.org/sites/default/files/publication/200205_land_grab_eng.pdf

- Marmot, M., S. Friel, R. Bell, T. A. Houweling, and S. Taylor, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2008. “Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health.” The Lancet 372 (9650): 1661–1669. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6.

- Mataria, A., F. Raad, M. Abu-Zaineh, and C. Donaldson. 2010. “Catastrophic Healthcare Payments and Impoverishment in the Occupied Palestinian Territory.” Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 8 (6): 393–405. doi:10.2165/11318200-000000000-00000.

- McNeely, C., B. K. Barber, C. Spellings, R. Giacaman, C. Arafat, M. Daher, E. E. Sarraj, and M. A. Mallouh. 2014. “Human Insecurity, Chronic Economic Constraints and Health in the Occupied Palestinian Territory.” Global Public Health 9 (5): 495–515. doi:10.1080/17441692.2014.903427.

- Mikki, N., H. F. Abdul-Rahim, F. Awartani, and G. Holmboe-Ottesen. 2009. “Prevalence and Sociodemographic Correlates of Stunting, Underweight, and Overweight among Two Major Governorates in the West Bank.” BMC Public Health 9 (485): 1471–2458. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-485.

- Mikki, N., H. F. Abdul-Rahim, H. Stigum, and G. Holmboe-Ottesen. 2011. “Anaemia Prevalence and Associated Sociodemographic and Dietary Factors among Palestinian Adolescents in the West Bank.” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 17 (3): 208–217. doi:10.26719/2011.17.3.208.

- Mourad, A., S. R. Tayser, S. Shashaa, C. Lionis, and A. Philalithis. 2008. “Palestinian Primary Health Care in Light of the National Strategic Health Plan 1999-2003.” Public Health 122 (2): 125–139. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2007.04.017.

- Nahal, M., S. Hmeidan, H. Wigert, A. Imam, and Å. B. Axelsson. 2017. “From Feeling Broken to Looking beyond Broken: Palestinian Mothers’ Experiences of Having a Child with Spina Bifida.” Journal of Family Nursing 23 (2): 226–251. doi:10.1177/1074840717697436.

- Ota, E., T. Ganchimeg, N. Morisaki, J. P. Vogel, and C. Pileggi. 2014. “Risk Factors and Adverse Perinatal Outcomes among Term and Preterm Infants Born Small-for-Gestational- Age : Secondary Analyses of the WHO Multi-Country Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health.” PloS One Edited by Gulmezoglu A M Souza JP Carroli G, Lumbiganon P, Qureshi Z, Costa MJ, Fawole B, Mugerwa Y, Nafiou I, Moumouni UA, Neves I, Wolomby-Molondo JJ, Thi H, Chandhiok N, Cheang K, Chuyun K, Jayaratne K, Jayathilaka CA, Mazhar SB, Mori R, Mustafa L, Pathak LR, Perera D, Rathav. 9 (8): e105155. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105155.

- Pourgourides, C. 1999. “Palestinian Health Care under Siege.” The Lancet 354: 420–421. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)90138-1.

- Ryan, C. 2017. “Gendering Palestinian Dispossession: Evaluating Land Loss in the West Bank.” Antipode 49 (2): 477–498. doi:10.1111/anti.v49.2.

- Save the Children UK. 2009. “Life on the Edge : The Struggle to Survive and the Impact of Forced Displacement in High Risk Areas of the Occupied Palestinian Territory.”

- Sawalha, A. F., R. O. Wright, D. C. Bellinger, C. Amarasiriwardean, A. S. Abu-Taha, and W. M. Sweileh. 2013. “Blood Lead Level among Palestinian Schoolchildren: A Pilot Study [concentration Sanguine De Plomb Chez Des Ecoliers Palestiniens: Une Etude Pilote].” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 19 (2): 151–155. doi:10.26719/2013.19.2.151.

- Sousa, C. A. 2013. “Political Violence, Health, and Coping among Palestinian Women in the West Bank.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 83 (4): 505–519. doi:10.1111/ajop.12048.

- Stefanini, A., and H. Ziv. 2004. “Occupied Palestinian Territory: Linking Health to Human Rights.” Health and Human Rights 8 (1): 160–176. doi:10.2307/4065380.

- Thabet, A. A. M., H. Al Ghamdi, T. Abdulla, M.-W. Elhelou, and P. Vostanis. 2010. “Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Symptoms among Palestinian Children.” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal = La Revue De Santé De La Méditerranée Orientale = Al-Majallah Al-?i??iyah Li-Sharq Al-Mutawassi? 16 (5): 505–510. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20799549

- Thabet, A. A. M., Y. Abed, and P. Vostanis. 2002. “Emotional Problems in Palestinian Children Living in A War Zone: A Cross Sectional Study.” Lancet 359 (9320): 1801–1804. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08709-3.

- UN ECOSOC (United Nations Economic and Social Council). 2001. “Economic and Social Repercussions of the Israeli Occupation on the Living Conditions of the Palestinian People in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Including Jerusalem, and of the Arab Population in the Occupied Syrian Golan (A/56/90–E/2001/17).”

- UNGA - United Nations General Assembly. 2013. “Permanent Sovereignty of the Palestinian People in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Including East Jerusalem, and of the Arab Population in the Occupied Syrian Golan over Their Natural Resources, A/RES/68/235 (20 December 2013).” http://undocs.org/A/RES/68/235

- UNGA - United Nations, General Assembly. 2018. “Gaza ‘unliveable’, Expert Tells Third Committee, as Mandate Holders Present Findings on Human Rights Situations in Iran, Eritrea, Somalia, Burundi, GA/SHC/4242 (10/24/2018).” https://www.un.org/press/en/2018/gashc4242.doc.htm

- UNHRC. 2013. “Report of the Independent International Fact- Finding Mission to Investigate the Implications of the Israeli Settlements on the Civil, Political, Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of the Palestinian Territory, Including East Jerusalem.” https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/A-HRC-22-63_en.pdf

- United Nations, Conference on Trade and Development. 2015. “Report on UNCTAD Assistance to the Palestinian People: Developments in the Economy of the Occupied Palestinian Territory, TD/B/62/3 (7/6/2015)”. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/tdb62d3_en.pdf

- UNOCHA. 2008. “Unprotected: Israeli Settler Violence against Palestinian Civilians and Their Property.” OCHA Special Focus.

- UNOCHA. 2013. “The Humanitarian Impact of the Barrier.” https://www.ochaopt.org/sites/default/files/ocha_opt_barrier_factsheet_july_2013_english.pdf

- UNOCHA (United Nations - Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs). 2007. “The Humanitarian Impact on Palestinians of Israeli Settlements and Other Infrastructure in the West Bank.” https://www.ochaopt.org/sites/default/files/ocharpt_update30july2007.pdf

- World Bank. 2013. “West Bank and Gaza: Area C and the Future of the Palestinian Economy.” Report No. AUS2922.

- Zakrison, T. L., A. Shahen, S. Mortaja, and P. A. Hamel. 2004. “The Prevalence of Psychological Morbidity in West Bank Palestinian Children.” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 49 (1): 60–63. doi:10.1177/070674370404900110.