ABSTRACT

After 2011, several Arab states initiated decentralisation reforms to address the demonstrators’ demands for more participative governance and more efficient public services. Taking Morocco's new decentralisation reform as a case in point, this article assesses the requirements for, and impediments to, progress. It discovers that the reform articulates important democratic principles and formally opens new spaces of action that may facilitate more efficient and participative governance. However, historical legacies of centralised control, few opportunities for participation, low institutional capacities and weak accountability, and also unclear regulations within the reform, are still hindering effective decentralisation. The potentially positive impact of current reforms on political liberalisation is thus uncertain. Recent uprisings in the Rif region are symptomatic of the neglect of regional inequalities and grievances, and of related dissatisfaction. They also illustrate that increased regional autonomy can only alleviate the structural problems in the longer term and when thoroughly implemented.

Introduction

The Arab uprisings articulated deep grievances about economically and politically marginalised groups and regions.Footnote1 Limited infrastructure, poor public services, and highly concentrated political decision-making in the capital left little space for civic participation and locally rooted and efficient policies in the regions. While local protests and claims are key to understanding the root causes of the uprisings, this local and often rural dimension has been overlooked by many researchers (Kherigi Citation2017; Paciello et al. Citation2012). Since 2011, several Arab countries have initiated new decentralisation reforms aimed at addressing two of the protestors’ key demands: more participative governance and more efficient and accountable public services. As Kherigi summarises: ‘In these states, the central state has been obliged to introduce incremental reforms as a way of defusing political and social tensions by moving towards greater devolution of power and decentralisation’ (Kherigi Citation2017, 13).

In Morocco, decentralisation, participation, and public-service provision have repeatedly been merged in the articulation of the regime's reform strategies, and more specifically in the 2011 constitution and within the so-called ‘régionalisation avancée’ (advanced regionalisation) – the new phase of the decentralisation process. Six years after their initiation, it is time to review the preliminary results of these reforms. Does the decentralisation reform really contribute to improved public services and to more participative governance? Does it help address the deep crisis of confidence and legitimacy in state–society relations? And, does it enable the state to react in an appropriate way to the recent uprisings in Morocco's long-neglected Rif region?

The results are, at best, mixed. Although key principles of the reform are backed by the new constitution, implementation on the ground has been delayed several times. While some signs point to a greater formal scope for more participative governance, others rather show the persistence of centralised structures and modes of governance. Some observers even state that there is a tendency to re-centralise as opposed to decentralise (Bouabid and Iraki Citation2015). The present article sheds light on the concrete requirements for, and impediments of, participation and institutional performance in the context of decentralisation in Morocco, and explores whether and how such reforms can thereby contribute to addressing the claims of the ‘Arab Spring’.

The desire to improve public-sector performance, and the aspiration to strengthen democratic governance, have been major drivers of decentralisation reforms all over the world (Connerley, Eaton, and Smoke Citation2010; Oxhorn, Tulchin, and Selee Citation2004). As a comparative study on the Arab world revealed, governance systems are particularly centralised in this region, with an average allocation of only 5% of the national GDP to local governments – compared to a share of 20% in OECD countries and 23% in Latin America (Harb and Atallah Citation2015). One explanatory factor is the impact of colonial and post-colonial legacies, as decentralisation has historically been used to consolidate state power and control territories and political opposition (Leveau Citation1976; Pérennès Citation1993). In this context, reforms have often led to situations where formal changes for more decentralised governance have not been fully implemented, and have even been hindered by other political or financial means, fostering centralised control (ibid.). As Harb and Atallah (Citation2014) put it:

Deconcentration was the actual dominant practice, which namely served to strengthen the central government's domination. This led to a major crisis of accountability between different levels of governments as well as vis-à-vis citizens.

In Morocco, persistent regional disparities are also one of the triggers of the current decentralisation reform. The country had witnessed important economic and human development since the 1980s (a 60% increase in its HDI score since the 1980s). This includes improved access to drinking water, electricity and traffic networks, even in formerly neglected rural areas. Nevertheless, important deficits in the education and health sectors, as well as high inequalities in income distribution (at a similar level to that in Tunisia and the USA), persisted and explain Morocco's current low ranking on the Human Development Index at the regional level.Footnote2 Under- and unemployment, especially among youth and highly qualified job-seekers, is high and frequently leads to protests. Additionally, after great improvements in human rights and press freedom, and the further rise of a vibrant civil society since current King Mohammed VI ascended the throne in 1999, the political system has again witnessed increased authoritarianism and political repression since 2013 (Madani Citation2014; Monjib Citation2016). Press freedom and the freedom of assembly, as well as the human rights situation, have deteriorated, as Amnesty International (Citation2016) and Merouan Mekouar, in his Washington Post article of 24 March 2016, note. Accusations are growing that the reforms promised are only being realised in a highly restrictive manner (Bouabid and Iraki Citation2015; El Mossadeq Citation2014; Madani Citation2014). The mobilisation of several protest movements in the years before 2011 (including the unemployed graduates, the trade unions, protest against increasing living costs, against public–private partnerships in water services, or women's movements fighting for access to soil and other rights) points to the long pre-existence of governance problems and to the regime's failure to address them. This resulted in the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ in 2011 and, more recently, in several protest movements in 2016/17, including the one in the long-neglected Rif region.Footnote3 As the large demonstrations in the whole country for solidarity with the movement and against its repression show, this concern is shared by other marginalised groups and regions.

There is little trust in public institutions: according to Afrobarometer, trust in core executive institutions is much weaker in Morocco than in far less developed African countries. The country is ranked 27 out of 36 countries, and only 49% of Moroccans interviewed expressed trust in these institutions ‘somewhat’ or ‘a lot’ (Bratton and Gyimah-Boadi Citation2016).

In reaction to the 2011 upheavals (and given the limited financial means to ‘buy’ social freedom such as pertains in several Gulf countries, where rents from oil export were available), King Mohammed VI initiated several reforms, which have been widely praised by international observers. The new constitution adopted in 2011 via a plebiscite promised several structural changes, and a new decentralisation reform was supposed to lay the foundations for a more participatory, transparent and efficient political and administrative system. The process of adoption of the new constitution, the text itself as well as the slow follow-up for the implementation of the constitution itself, have been criticised by local observers (Benchemsi Citation2017; Bendourou Citation2014).

The second major motivation for implementing the decentralisation reform was to propose a solution to the longstanding conflict over the Western Sahara territories: local inhabitants would benefit from a new status of autonomy, their own locally elected representatives, and supposedly more financial means to be administered at regional level for regional priorities. Between Moroccan centralism and the striving of the Polisario Front for advanced autonomy, the process of regionalisation was intended to favour local development based on a decentralised administrative structure and thereby help counter the separatists’ objection to a high dependency on the central government. The ‘Southern provinces’ have already benefitted from vast investments in infrastructure and public services during the last years and might be expected to get more political autonomy. However, the territory concerned is now included in three of the newly designed regions, which facilitates centralised control by dividing potential political alliances within the territory. It remains to be seen if decentralisation as a means to increased local autonomy can nevertheless convince separatists.

Six years after the adoption of the 2011 constitution, the new division of the country into two regions was adopted in 2015, the first regional elections took place in the same year, and important organic laws have been adopted that provide an initial indication of future implementation of the reform. Nevertheless, discontent over persisting centralised and authoritarian control over the political system, dominated by the Monarch, and claims for more egalitarian, participative, transparent and efficient governance are on the rise again. The lack of progress on economic and political development, and a precarious security situation (The Bureau Central d’Investigation Judiciaire, BCIJ, frequently reports on dismantled terrorist cells and arrested IS-supporters) further complicate the situation.

In the face of these multiple challenges and expectations, does the decentralisation reform enable significant progress in the sense of the population's claims for improved governance? And, more specifically, does it help improve public-sector performance and allow for more participative and democratic governance, which were two key concerns of the protestors?

The paper seeks to answer these questions in the case of Morocco by first summarising key research findings on if and how decentralisation can influence institutional performance as well as participative and democratic governance. Second, it analyses the implementation of the reform in Morocco with respect to its possible impact on these two issues. Third, the conclusion summarises these findings and puts them in the broader context of prospects for political liberalisation in the country. The results are based on qualitative research conducted in 2015 and 2016, including a review of scientific literature and local newspapers, journals and media websites, as well as interviews conducted with local scientists, policymakers and representatives of the international development cooperation.

The potential impact of decentralisation on public-sector performance and participation

During the 2011 uprisings, protestors in Morocco expressed a range of concerns, but discontent over the bad performance of public services and insufficient freedom for political participation were particularly widespread. Both issues were also explicitly addressed in several speeches of King Mohammed VI relating to the new constitution and to the decentralisation reform, and were put forward as milestones of a modernised administrative and political system. However, besides the adoption of the principle of subsidiarity,Footnote4 the exact mechanisms meant to positively influence political participation and public-sector performance through decentralisation were only partly articulated in the reform. Against this background, and in order to evaluate the potential of the current reform to positively influence these two issues, the present section summarises major research findings on the links between decentralisation and public-sector performance, as well as between decentralisation and political participation.

In general, decentralisation includes administrative, fiscal and political aspects. In terms of administrative decentralisation, it is helpful to distinguish between deconcentration (transfer of competences to subnational entities of the central government), delegation (transfer of competencies to subnational bodies) and devolution (transfer of tasks from the central government to elected subnational institutions). According to the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) and others, one usually observes a mix regarding the types of administrative decentralisation (GIZ Citation2014). However, for successful implementation, tasks have to be clearly defined and assigned to the responsible entity.

Overlaps and interdependencies between decentralisation and public-sector performance, or between decentralisation and political participation, are obvious. Decentralisation is widely thought to improve democratic governance by bringing political decision-making to local levels and reinforcing accountability and state responsiveness through localised governance. Conversely, performance incentives and accountability benefit strongly from good political relations among citizens, civil society, and state leadership (Devarajan, Khemani, and Walton Citation2011). Moreover, both aspects are also of crucial importance for political legitimacy. With respect to institutional performance Grävingholt et al point out:

(…) in particularly fragile states and those with key deficits in the capacity dimension, the strengthening of administrative capacities and the development of competencies at all levels are important approaches that the promotion of decentralisation can offer. This includes increasing the actual capabilities of the state as well as improving the conditions that could enable political and fiscal decentralization to succeed. (Grävingholt and von Haldenwang Citation2016, 13)

As for public-sector performance, research and practice show that decentralisation can only have a positive influence if institutions at all levels are able to properly exert their functions and responsibilities. Otherwise, citizens will not be able to increase trust in public-sector institutions and officials. This, in turn, depends on three key issues: adequate legal frameworks, sufficient competences and capacities of public institutions at all governance levels (including the national, regional and local level), allowing meaningful public participation that may reinforce the two former elements.

First, effective decentralisation requires adequate legal frameworks regulating the competences of public administrations and of elected bodies, as well as the institutional interplay at horizontal and vertical levels (LDI Citation2013). As Grävingholt et al. point out: the basic assumption is that ‘(…) decentralisation increases the efficiency and the demand-orientation of the public sector. Here, the key drivers are the competition between sub-national units and the superior configuration of public services to local demand profiles’ (Grävingholt and von Haldenwang Citation2016). However, it is also important to note that ‘When it succeeds, decentralisation by definition disrupts the deeply embedded relationships and networks that previously sustained decades – if not centuries – of centralised rule’ (Connerley, Eaton, and Smoke Citation2010, 3). Effective decentralisation reforms involve complex changes in terms of public institutions and the way a society functions. These processes take time during the implementation and consolidation phase of the reforms.

Second, financial and human capacities also greatly influence institutional performance; to function at full capacity, an institution requires a sufficient number of well-trained staff, disposing of adequate financial resources. In contrast, many Arab countries lack financial autonomy at local levels and therefore centralised decision-making persists, in spite of decentralisation reforms, hampering institutional performance (Harb and Atallah Citation2015). Moreover, when tasks and duties are transferred to local levels but institutional competences and capacities are too weak, this may overburden administrations and lead to even worse outcomes than before the reform, for example, when reinforcing regional disparities. Research also shows that remote areas are less able to benefit from decentralised service delivery because of weak administration and democratic practices (Mansuri and Rao Citation2013); these regions would therefore need particular support. Technical assistance can help build up relevant capacities in this sense, and this has been one of the key activity areas of international donors in the last decade in support of effective decentralisation processes (Connerley, Eaton, and Smoke Citation2010). Beyond the institutions’ technical capacities, political support, active motivation of and incentives for local bureaucracies, their ability to assume or divest responsibilities and work cooperatively across levels are important factors in the implementation of the reform (Connerley, Eaton, op.cit.). Getting all these elements together is challenging and time consuming. This is why implementing decentralisation takes years, and sometimes decades.

Even in cases where decentralisation is adequately implemented, its effects on the performance of public services – and thus on ordinary citizens’ quality of life – are not guaranteed (Eaton, Kaiser, and Smoke Citation2010). The third key issue in this respect is meaningful participation of local populations, for example through community empowerment. According to research findings, this can positively influence institutional performance (Fung Citation2006). As Brixi, Lust, and Woolcock (Citation2015) have found out in a comparative study of success stories in the MENA region, public participation can considerably increase accountability in service delivery. In their comprehensive review of practical experiences with participation in local development, Mansuri and Rao (Citation2013) came to the conclusion that citizen engagement, in turn, strongly depends on the availability of information and the enabling environment for citizens to act on this basis. Moreover, they highlight the importance of participation for better performance in service delivery: ‘Only those local governments that are pushed by citizens and civil society to be more accountable are likely to become more responsive when bolstered by the increased funding and authority that comes with autonomy or decentralization.’ (cited in: Brixi, Lust, and Woolcock Citation2015, 306).

As for the second aspect, political participation, research findings on a potential causal relation between decentralisation and participation/democratisation are equally ambiguous. Strengthening local governance is a key objective of many decentralisation reforms and there is a widespread belief that such a reform per se leads to democratisation. This is based on the assumption that decentralisation strengthens the accountability and transparency of local politicians and institutions, inter alia due to increased public pressure, new and multiple opportunities for political activism, and stronger local competences for decision-making (Connerley, Eaton, and Smoke Citation2010). However, research also shows that decentralisation can also reinforce authoritarian or centralistic regimes where election mechanisms are inadequate (Bland Citation2010), or political parties are too strong or too weak (Mainwaring and Scully Citation1995; Montero and Samuels Citation2004). A strong civil society and active participation processes, including innovative formats (citizen councils or dialogues, public budgeting, gender balanced approaches …) that go beyond the electoral processes, are therefore considered to be highly important for strengthening the democratic potential of decentralisation (Brinkerhoff and Azfa Citation2010; Fung Citation2006). In the Arab context, a study in Lebanon points out that effective leadership at regional and local levels, strong multi-level networks and a high degree of political competition are conducive to the implementation of decentralisation and democratic governance in this context (Harb and Atallah Citation2015).

However, the impact of decentralisation reforms on democratisation is disputed, and research shows that the principle of subsidiarity as such does not guarantee a strengthening of local decision-making and participatory processes. Oxhorn, Tulchin, and Selee (Citation2004, 296) highlight that ‘the kinds of institutional arrangements employed often limit the capacity and autonomy of subnational governments to implement the functions that they are supposed to perform, which, in turn, undermine their relevance in the democratic process’. Moreover, the devolution of power to local levels may reproduce or even reinforce local power structures and corruption, for example when predatory elites capture local power centres, as seen in many cases (Faguet Citation2011; Harb and Atallah Citation2015; Tomsa Citation2015). As Mansuri and Rao (Citation2013, 6) highlight, this may be due to poor education/information and/or low public pressure:

The benefits of decentralization seem to be weaker in more remote, more isolated, and less literate localities. Such localities also tend to be more poorly served by mass media and other sources of information, and they are less likely to have adequate central oversight.

This also points to the potentially critical role donors can play in influencing the design and implementation of such reforms. In academia, there is a vast debate on potential positive and negative effects of such an engagement. For example, donors may negatively influence the local political economy and contribute to reinforce local corruption and/or illegitimate local leaders by injecting resources and partnering with the ‘wrong’ leaders (Smoke Citation2010). This may result in uneven development and the marginalisation of some population groups, and ultimately even increase the fragility of the respective country (Grävingholt and von Haldenwang Citation2016). Donor coordination and common approaches to their support of these reform processes is key to avoiding such developments and uniting forces to support effective implementation.

Strong donor support, but without the necessary coordination among the different actors, may also overburden national and local governments, as well as increase ineffective management of funds and means (Smoke Citation2010). Nevertheless, as much as the goals of decentralisation processes may differ from one country to another, there can be a wide range of donor priorities in such reform processes. The harmonisation of the donors’ objectives should therefore be a priority.

Against the background of these insights, the current phase of the decentralisation reform in Morocco is discussed below regarding its potential impact on public-service performance and participation. Given the very limited engagement of donors in the Moroccan process so far, the article discusses the potential scope for, and limitations on, action in the light of the remaining research findings in the conclusion.

The decentralisation process in Morocco

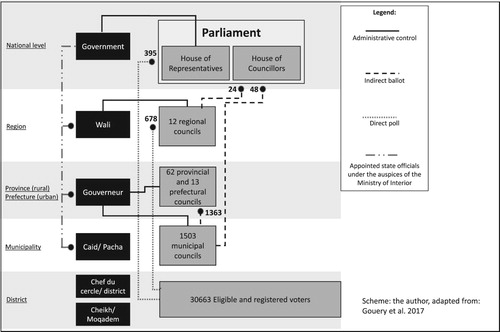

Morocco is a constitutional monarchy where the impact of the colonial legacy which Harb and Atallah (Citation2015) point out for various Arab countries is still visible: a double-headed administrative system originally put in place by the French rulers persists to the present day. When the administrative system was first instigated, the strategy of the colonial power was already aimed at weakening national resistance movements by strengthening local regional authorities (Bouabid and Iraki Citation2015). The father of the present King, Hassan II, adopted this ruling strategy and specifically established corresponding alliances with rural and urban elites, with the goal of diluting the influence of the partly republican independence movement (Leveau Citation1976; Waterbury Citation1970). This structure is symbolised by parallel institutions at all levels of the state apparatus, where centralised authorities under the auspices of the Ministry of Interior (which is, in turn, controlled by the King) supervise and often dominate elected bodies in planning and decision-making processes (see ).

Irrespective of this strongly centralised structure, there have been several attempts by kings and governments to strengthen decentralisation. The first attempts in this sense go back to the time period before independence in 1956. In 1976, municipalities were officially recognised as legal entities, although they were still supervised by the Ministry of Interior. This decision was based on article 93 of the constitution of 1969. This is the reason why the recent decentralisation process is often dated back to 1976. The municipal charter articulates, in Article 30:

The Council has the right to determine the affairs of the municipality and to decide on measures ensuring its full economic, social, and cultural development. The State and other public institutions can assist the Council in carrying out its mission.

As a second phase, one can describe the time period of the constitutional reforms of 1992 and 1996 leading to the official recognition and establishment of the regions in 1997. The municipal charter was reformed five years later in 2002. However, no significant decentralisation of relevant competencies, for example with regard to financial decentralisation, had been implemented at this stage. It was only in 2009 that the next reform of the municipal charter laid significant foundation for the current stage of the decentralisation process.

As Manuel Goehrs, an expert on participation and local governance in Morocco states: if there has been a true moment of local democracy, it is the year 2009 (Goehrs Citation2014). Substantial changes were introduced, which also affected the potential for political participation and representation: the possibility of leave from work for officials elected as presidents of municipalities; citizens’ right to information (by electronic means); a commission on equality and gender; public information on how a municipality was organised and functioned; the strengthening of the coordination role of Secretary General of the municipality; a municipal development plan; local development companies [note by the authors: private companies performing public services,]; reinforcement of ‘unity of the city’ (conference of the presidents of district councils) [note by the authors: an approach that pools a city's funds for infrastructure projects and public services]; the grouping of agglomerations. (Goehrs Citation2014, 30).

However, in the subsequent two years, no major further achievements were made with regard to the implementation of these reforms. The dual structure described above, and informal power relationships and bargaining, largely assumed central control of regional and local structures. As Ojeda and Suárez confirm:

The Makhzen has indeed been able to control local elites through various mechanisms operating in the regional sphere, and in particular by appointing local governors, by accepting the duplication of offices to allow candidates to be elected members of regional councils and the national Parliament at the same time, and by supporting rural notables. (Ojeda García and Suárez Collado Citation2015, 50)

Irrespective of the current difficulties in the implementation of the reform, its framing and the articulation of supportive policy principles in the 2011 constitution could indeed contribute to reinforcing the regime's legitimacy if public institutions would perform better, and chances for political participation and decentralised decision-making would improve. However, compared to the expectations raised and the urgency of progress on this matter, implementation is so far still weak and leaves expectations behind. The following section analyses the progress and challenges since 2011, first concerning perspectives for improved public-sector performance and then regarding the reform's possible impact on participation.

Does the Moroccan decentralisation reform help to improve public-sector performance?

The analysis of Morocco's current decentralisation reform with respect to the above-mentioned research findings in other countries reveals that there are three key concerns that may hinder improved public-sector performance in this context. The first is the persisting double-headed system, the second concerns the legal frameworks regulating the responsibilities and capacities of public institutions, and the third refers to the lack of institutional accountability.

First, institutional performance will continue to be affected by the above-mentioned structure of Morocco's politico-administrative system. In addition to the formal institutional setting illustrated in , the monarch's and the political elite's power is further strengthened by other mechanisms, including the monarch's right to dismiss ministers, to nominate Walis (these are nominated by the ministerial council presided over by the King, and not by the parliamentary council) and by the considerable influence of extra-parliamentarian commissions and councils. Moreover, the whole apparatus of institutions and people close to the monarch, known as the Makhzen, also includes strong and widely dispersed informal networks and relationships. At the municipal level, for example, financial decisions, and virtually all administrative processes, had to be validated by the Ministry of the Interior (Bouabid and Iraki Citation2015).

Additionally, in Morocco, as in other countries, negotiation processes are often conducted informally, with the consequence that the distribution of competencies between the elected structures and structures subordinate to the King is in many cases a formality (Reifeld Citation2014).

Second, as observed in other countries and detailed in the previous section, legal frameworks regulating the public institutions’ competencies and capacities as well as their adequate financial and human resources are crucial for institutional performance in the context of decentralisation. Both elected bodies and administrative entities are affected by the design and implementation of these factors. With respect to both, the capacities of public institutions in Morocco are, overall, estimated to be inefficient for an effective implementation of the reform (Bouabid and Iraki Citation2015).

Morocco adopted organic laws in 2015, in particular three laws relating to territorial authorities, most importantly for the current reform, law 111–14 regarding the regions. They articulate important frameworks in this sense, but as long as further specifications are not spelled out and formally adopted, implementation cannot progress. With the amendments in the constitution and new regulations adopted via the organic laws, the 12 regions (formerly 16 until the new territorial division implemented in 2015) are now promoted, to become major actors in decentralised policy design and implementation. The principle of subsidiarity is laid down in the constitution, and the regions’ formal tasks now include economic development, including industry, training and vocational training, rural development, transport, culture, the environment and international cooperation; they are also largely responsible for designing strategies for local infrastructure development, as in the energy and water sectors. However, the exact sharing of responsibilities, competences and resources at vertical and horizontal levels is not yet clear, and is supposed to be spelled out by upcoming laws and decrees that are necessary for further implementation. While the regions have witnessed a considerable increase in their budgets, and benefit from new fiscal revenues (see details in Goeury, Slassi, and Benmoumen Citation2017, 17), it is still uncertain how these resources will be allocated to different sectors or institutions. The persisting struggle over the establishment of new regional development agencies illustrates this.

In every region, new and influential agencies for project implementation (‘Agence régionale d’exécution des projets (AREP)’) have been created since 2016, and some of these have taken up their work, under the supervision and the control of the regional council. Their task is to support the regional council in technical and financial aspects of project design and in their implementation. However, in three regions these institutions so far still compete with the already existing and powerful development agencies (‘Agences de Développement’ under the auspices of the chief of government), which have until now been used to channel important sums to strategically relevant border regions under centralised governmental control. In the Oriental region, the former institution covers the same geographical area as the new one. The situation is even more complicated in the two other, strategically very relevant, regions: the North (including the rebellious Rif region) and the South (including the Western Sahara), where the geographical boundaries of the existing and of the new institutions do not overlap due to the reform of the regions. While rumours spread about the closing of the three ‘Agences de Développement’(AD), this has not yet been officially confirmed at the time of writing this article. Nevertheless, the very slow pace of decisions on this matter reflects the related power-struggles, which include the interests of the central government (responsible for the AD) and of the regional councils (responsible of the AREP), but also of the administrative staff (AD's staff are afraid of being dismissed, having their pay or reduced, or being transferred to other services). While the ARUP in the rebellious region of the North has been allocated an important budget to calm local protest against insufficient development, observers fear that the AREPs in general may never be able to mobilise as much funding as the AD did because of the limited financial means of the regions, and that they may be understaffed in comparison to the previous institutions (Abou El Farah Citation2016).

In many regards the exact design – and thus the impact – of the decentralisation reform will remain unclear until the respective regulations are adopted, but major concerns arise with respect to its impact on institutional performance.

The first regional elections, held in 2015, were a significant step towards political decentralisation. However, deconcentration and decentralisation are co-existing parallel structures at all governance levels, even after the implementation of the current reform, if authority is not really transferred between levels of government, and responsibilities are shifted to local levels while the means to deal with these and related decision-making processes remain at the central level. This leads to power-struggles, bargaining and often opaque decision-making procedures. Building trust in elected government officials and the respective institutions behind them is often perceived as very challenging. In addition to the double-headed politico-administrative system, insufficient and unclear regulations concerning institutional competences and resources, as well as low capacities of existing bodies, are considerably hindering successful further implementation. While capacity building at different levels will be inevitable to stem the reform, this takes time, and shortcomings may open the door to abuse of newly transferred power or resources, as observed in other countries (see introduction of this article). It remains to be seen if new institutions at the regional level will effectively be able to exert power and to allocate resources for the implementation of the newly assigned tasks e.g. in different sectors as explained above.

Third, the lack of transparency in Morocco's public and private sectors makes it hard to hold institutions accountable (A. Akesbi Citation2014). This negatively affects institutional performance and is a root cause of the persisting high level of corruption. Even though the government joined the International Budget Partnership, which aims to strengthen these factors, the state's institutions are scored very low in the IBP report. As of 17 August 2017, the IBP lists on its website the overall score for 2015 as 38/100 points. Control and oversight of the parliament and of the Court of Auditors are scored at even lower levels (21/100 and 17/100 respectively. The 2011 constitution explicitly raises the issue, articulates principles of transparency and accountability (inter alia in article 15) and promotes public institutions in charge of these issues (such as the ‘Conseil de la concurrence’– the competition council; the ‘Instance de lutte contre la corruption’ – the institution for fighting corruption; the ‘Institution du Médiateur’ – the mediation institution), but implementation is so far lagging behind due to unclear regulations and nomination issues (N. Akesbi Citation2014). Lack of access to information is not only a problem for citizens and civil societies, but also for the exchange among public institutions themselves and their co-ordination. The Chairman and Governor of the state bank Al-Maghrib, Abdellatif Jouahri, for example, assesses the public use of funds as very poor, and calls for organic laws to be applied promptly and comprehensively to finances in order to allow for more transparency and better information exchange. He points out that the actual implementation of all plans to achieve the transparency of public finances formulated in the constitution would prove to be a major challenge due to the lack of data (e.g. regarding state property), as Belghiti notes in L’Economiste (L’Economiste, September 19, 2016).

Does the Moroccan decentralisation reform help enable more participative governance?

This section highlights that decentralisation can benefit political participation and eventually also democratisation (or at least political liberalisation) when the population's contribution to political decision-making is guaranteed by formal institutions and is also made possible and encouraged. Information and education, as well as accountability and transparency, play an important role in this context.

In Morocco, the principles of democratic and transparent decision-making are prominently spelled out both in the constitution and in the decentralisation reform, which formally open new avenues for civil society participation and local decision-making. While these statements raised high expectations, implementation is, so far, lagging behind. One example is the election of the regional presidents supposed to strengthen democratic and decentralised decision-making: although the first elections were held in 2015, the system of indirect election has led to several negotiations ‘behind the scenes’, with the result that the presidents appointed do not always reflect the majority of the direct electoral votes. While the Justice and Development Party (PJD) won the 2015 elections, obtaining four times more seats than in 2009, it controls only two regions. The president and the vice-president of the region are elected by indirect vote by the members of the regional council. As the parties had agreed to stick to their national-level alliances when voting for these regional positions, in many regions the heads of the region do not entirely reflect the direct votes of the population. In five regions, the indirect vote has led to the designation of monarchist PAM (Authenticity and Modernity Party) representatives as presidents, while in some of them, such as in the region of Beni Mellal-Khenifra, the number of regional councillors from the PAM is inferior to the number of another party's elected councillors (in this case the MP). In other cases, agreements between the PJD and other parties have not held, at the expense of PJD's power. Several reports confirm that negotiations behind the scene contributed to marginalising the PJD party in spite of its good election results, which points to the strong influence of the King and his allies in the democratic ‘game’ (Wenger Citation2015).

Beyond the electoral system, the population still does not have many opportunities to participate in political decision-making. Important institutions for progress in this sense had been announced in the aftermath of the 2011 protests but are either not yet implemented or rather designed as ‘paper tigers’. Examples include the right, guaranteed in the constitution, to launch petitions, which has been severely restricted in the respective law for its implementation. Disappointment also prevails over the current draft of the law of access to information, which is much more restrictive than the previous regulations (TransparencyMaroc Citation2014). Given that information plays a key role in political information and mobilisation, to combat insufficient accountability and as a prerequisite for the decentralisation reform, this development does not encourage progress towards political liberalisation/democratisation. Moreover, the creation of institutions supposed to improve the inclusion of civil society, women and youth into political decision-makingFootnote5 has either not yet materialised or been restricted to a very narrow scope of action (FIDH Citation2015).

Beyond formal changes, the persistence of the Makhzen system and the deconcentrated institutions will continue to limit political liberalisation and participation as long as the institutions that are subordinated to the King dominate elected bodies and informal decision-making. For example, even if both the constitution and the organic law have attributed more competences to decentralised institutions, it is highly probable that these – including the supposedly strong regions – will still be subject to the influence and decisions of the Walis and governors. Article 145 of the constitution points to necessary ‘coordination’ between the regions and the governors/Walis, but does not clarify the respective mechanisms of decision-making (Reifeld Citation2014). It states that governors are in charge of ‘support and coordination of public policies’ together with the Walis and the presidents of the regional councils, but so far no law defines the respective mandates, responsibilities and rights of these three different actors. According to the think tank Tafra and other observers, the Wali will continue to be the focal point for all investment and development policies (Goeury, Slassi, and Benmoumen Citation2017, 21). The municipalities in turn, which had made some progress in designing six-year-development plans in a very participatory way, are now limited to a more technical role and are to conceive municipal action plans for the implementation of strategies to be developed at regional levels (Goehrs Citation2014). Mayors are reported to be deceived about this new top-down approach, which replaces the former bottom-up mechanism (Bouabid and Iraki Citation2015), and takes decision-making competencies, crucial for trust-building and ownership, away from citizens. It remains to be seen how the institutional interplay between the regional and local level develops. This will also depend on the power of the people in office and their respective networks. At the national level, article 49 of the constitution guarantees the right of the council of ministers, chaired by the King, to decide about all ‘strategic orientations of state policies’. The latter are not further detailed and therefore potentially encompassing virtually every topic (A. Akesbi Citation2014).

Conclusion

Based on existing research on the potential effects of decentralisation reforms on public-sector performance and on participation, this paper has reviewed the respective developments in Morocco since the uprisings in 2011. While reform was presented as a key measure in addressing the protestors’ claims, progress with respect to these two issues has been very slow so far. The reforms did indeed lay important foundations for political change, including improvements in public-service delivery and participation (in spite of the limitations mentioned above) and high-level commitment to related values and principles. Nevertheless, institutional performance is severely hampered by a lack of progress in the design and implementation of respective regulations, and the limited capacity of public institutions to efficiently cope with the current workload. The implementation of new tasks and duties required by decentralisation reform will challenge institutional capacities even more. Political participation and interest in formal political processes has so far not progressed much in the context of the decentralisation reform either. Even young people and people working on political issues do not participate in elections, mainly because they feel that it does not make a difference (source: interviews with civil society members, 2015/16). As the 2016 Arab Human Development Report states for the whole region, ‘outside demonstrations, political participation and civic engagement are weak among young people’ (UNDP Citation2016, 61). Civic engagement in Morocco is lower than in all other Arab countries except Jordan and Iraq (UNDP Citation2016, 60). At the same time, as demonstrated by the new uprisings in the Rif region since 2016, in the city of Jerada and its surroundings (since 2017) and in Zagora (2017), as well as the multiplication of demonstrations since 2011, engagement in – sometimes violent – protest is increasing. The low rates of civic engagement and of voting in elections reflect the low formalised participation, and confirm a lack of trust in formal processes of decision-making and conflict resolution (where political participation might be possible, but inefficient), while mobilisation of support for several local and national movements, in spite of sometimes harsh repression, illustrates the high interest in public affairs and concern for improved development, including democratic decision-making. Decentralisation reform could therefore only contribute to strengthening political participation and liberalisation if the newly elected institutions were to gain substantially more authority and legitimacy. Their room for manoeuvre and strengthening in relation to the structures answerable to the King will largely depend on the tailoring of their competencies, the improvement of personnel capacities and the provision of financial and legal means for the implementation of policy, as well as freedom of decision regarding their own priority projects. Monitoring and control through reinforced and independent accountability structures are key to effectively implementing these changes. Nevertheless, where important advances in terms of political commitment for change were made and officially adopted, implementation is either lagging behind or more restrictive than expected. As the response to the Hirak movement and related regional development plans, but also the promotion of public investments and the role of private enterprises, have shown, the central government seems to privilege decentralisation as an instrument for economic growth rather than for regional political autonomy. The ongoing dispute about the fate of the centrally controlled development agencies (see above) also illustrates this observation.

A comparison of both institutional performance and participation in the current reforms has also revealed that both issues are intrinsically linked. Institutional performance, for example, benefits from independent oversight institutions that are accessible to all citizens. Therefore, while decentralisation reform is undoubtedly a complicated and long-lasting process, both the technical and the political aspects need to be addressed at the same time, and only when progress in one area is closely linked to improvements in the other can implementation advance.

As some authors have warned, new institutions may be captured by old and new elites undermining political change or explicitly serving centralised control (Bergh Citation2013; Hoffmann Citation2013). However, given the fragile regional environment, with several Arab states suffering from civil war (Libya, Syria) or high instability (Egypt) in the aftermath of 2011, and ongoing protest for more efficient, transparent, egalitarian and participatory governance even in Morocco, political stability in the country is closely linked to progress on these matters. While Morocco's dual structure of elected and appointed institutions is not likely to disappear, political change, with real progress in both public-service delivery and political participation, needs to be brought within this system. So far, the monarchic structure defines the boundaries of decision-making processes and policy outcomes. Nevertheless, as studies in other countries have shown, even in authoritarian regimes the implementation of decentralisation has, in the longer term, led to important concessions of the very same regime (Falleti Citation2011).

Effective implementation of decentralisation in Morocco would, however, benefit from three major developments.

First, a real political commitment is needed to effective power-sharing by the monarchy and decisive support of and by the political elite, the administration and other institutions at all levels to handle the reform and related changes in power structures and allocation of resources. Political commitment will clearly depend on possible gains to be made by the regime. As Eaton et al. (Eaton, Kaiser, and Smoke Citation2010, 24) rightly point out: ‘understanding decentralisation requires appreciating its fundamental underlying paradox: what motivates the central government to give up powers and resources to subnational governments?’ In the Moroccan case, the main motivation for the regime – which includes the King – would be its increased political legitimacy, which would improve political stability in an overall turbulent political and security situation in the region. Uprisings in the Rif region and elsewhere in the country are symptomatic of the neglect of regional inequalities, grievances and deficient local governance. They clearly show that the decentralisation reform's current state of implementation does not help foster local decision-making or efficient local governance and public services. Several commissions appointed by the King have the task of enquiring why development projects have not been implemented as planned. While it is worthwhile asking this question, the process is also a tactical manoeuvre by the King, contributing once again to weakening the parties’ and local governments’ authority and legitimacy and thereby reinforcing the King's raison d’être. Moreover, the protests also highlight that decentralisation, as such, is always embedded in the larger politico-economic system. Except for limited progress in local spaces of action, increased regional autonomy can therefore only tackle the above-mentioned structural challenges in the context of broader change, in the longer term and when thoroughly implemented. The Hirak protests in the Rif and its solidarity movements seem to have created a new political momentum for change and may support political commitment for real change. In his throne-day speech on 29 July 2017, and as a response to the uprisings in the Rif region and widespread criticism regarding regional disparities and poor public services, King Mohammed VI acknowledged many of the structural problems (Mohammed VI Citation2017). When blaming the elected politicians for failing to improve regional development or to implement the reforms articulated in the 2011 constitution, he successfully presented himself as a neutral mediator and not as part of the problem. However, if the changes he called for, such as better transparency and improved accountability of public institutions, as well as more participatory decision-making, are truly implemented, this would also benefit the implementation of the decentralisation reform and its potential effects on institutional performance and political liberalisation.

The second major development required for decentralisation is for elected bodies – the parliament first of all, but also decentralised bodies – to be given a real opportunity to engage in meaningful decision-making and policy implementation. Only then would they stand a chance of strengthening their currently low legitimacy.

Besides the formal requirements for enabling participative governance, trust building is essential to allow for a new and more egalitarian relationship between elected bodies and institutions dominated by the monarch. Due to Morocco's monarchical structure and its long history of centralised rule, it is challenging to build trust in public bodies besides the well-known institutions. The dominance of the Makhzen is seen as the main reason why many people interviewed by the authors (interviews in Rabat and in the Souss-Massa region in 2016 and 2017) perceive that political participation will not make a difference. Effective decentralisation will not be possible without shifting power to elected government bodies, including an increased transparency in decision-making processes. This, however, will be a process of decades, and will only be possible if the monarchy indicates clear commitment by allowing significant changes and implementation of the reform. Slowly shifting the political culture will be key to successfully engaging citizens in political decision-making processes on the ground. Therefore, a key success factor for the current reform will be to establish strong linkages between the new regional institutions and the local level and local communities to really reach the citizens. In order for the reform to be successful over the next few years, communities must be able to access information more easily and feel that their engagement will make a difference. So far, it remains unclear how the new regional bodies will exercise their functions and engage local authorities in political, administrative and fiscal terms. The legitimacy of public institutions is also closely related to their improved performance and accountability, especially in service delivery. It requires an adequate legal and political environment for them to engage in this process, but also related capacity development and information.

Third, development cooperation could support the effective implementation of the decentralisation reform regarding public sector performance and participation Given the potential pitfalls of donor engagement in such contexts, discussed in the introduction of this article, any support should, however, be based on a sound understanding of the local political economy and related trade-offs or side-effects, and be coordinated among the different donors. As stated above, when external support is disconnected from the local context and works solely or primarily with state institutions, support to decentralisation processes can further strengthen marginalisation and benefit already powerful groups (Grävingholt and von Haldenwang Citation2016; Harb and Atallah Citation2014, Citation2015; Jari Citation2010); it would then even reinforce the structural underlying causes of the ‘Arab Spring’ and contribute to new unrest and instability in the region. If donors do not take into account the local political economy and the interests and power-relations of their partners, there is a danger that donor support to the reform contributes to what Bergh (Citation2013) calls an ‘authoritarian upgrading’, i.e. the appropriation of the new structures and institutions by old elites in order to reinforce centralised governance. In Morocco, external support should focus on very precise activities in capacity development and an exchange of lessons learned from other countries or institutions. Possible activities include supporting institutional development, offering training and capacity building for government officials at all levels, including the municipalities, to assist cooperation between the different institutional bodies, leading to sound policy outcomes. At the same time, support to civil society organisations and citizens, including young people, to enable a better understanding of the principles of and opportunities for decentralised participatory governance, is also crucial, as public awareness is currently low, and only an informed public can meaningfully engage in the process. In line with the international development agenda, it is crucial to design projects focused on stakeholder needs and not driven by donors. It is, furthermore, important to allow and strengthen effective bi- and multilateral donor coordination, including the activities of foundations and think tanks in addition to official bilateral projects.

It becomes clear that decentralisation reform, as it is currently implemented, does not represent an adequate answer to the concerns raised during, and the origins of, the ‘Arab Spring’, nor to the recent protests in the Rif region and elsewhere. Nevertheless, together with the intentions articulated in the 2011 constitution, it does provide for important principles that could enable better public-sector performance and increased political participation, including political liberalisation. The implementation process so far however is dominated by its own political economy: the renegotiation of social resources such as power, money and legitimacy.

Beyond the case of Morocco, the present analysis of decentralisation reform as a policy response to the ‘Arab Spring’ sheds light on the ambiguity of related political promises. In the past, decentralisation reforms in many Arab states mainly served to reinforce centralised control over territories and population groups. This historical legacy shows that such reforms cannot be assessed based on their political claims alone. The crisis of accountability and trust between different levels of government, as well as between public institutions and citizens, that was caused by the strategic ‘misuse’ of decentralisation processes has been a major factor of the 2011 unrests. The fact that Arab governments now explicitly refer to decentralisation as an adequate answer to address the claims for more political participation and improved institutional performance and accountability is therefore somehow ironic.

In the face of decades of authoritarian rule, reallocation of state resource and economic opportunities towards selected elites and high corruption, a crisis of trust, credibility and legitimacy has emerged in most states of the Arab world. The answer lies in the regimes’ response to the uprisings and to the democratic challenges, they pose: are they really willing to install more participatory and transparent modes of governance and power-sharing, which will also enable better institutional performance and contribute to increase the regimes’ legitimacy? Or will the old and new regimes stick to authoritarian, centralised rule and use their scarce economic resource to continue supporting the small elite at the expense of the living conditions and political freedom of the majority? Decentralisation per se does not lead to one or to the other, but if properly implemented it can be a powerful instrument – in either way. The Moroccan example also shows that, independently from the current political situation, the changes endorsed in 2011 – such as the democratic principles adopted in the new constitution and in the decentralisation strategy – do provide room for manoeuvre and can help support the claims of the – in this case very active and often influential – civil society. Therefore, the appropriation of the decentralisation process as a tool and a claim for more democratic governance will remain a key issue in the further implementation of reform in Morocco and in the region.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We thank the reviewers for their thoughtful and supportive comments.

2 2014: rank 126, which is better than its rank of 130 in 2011, but worse than that of Tunisia (96), Algeria (83) and Egypt (108).

3 In the first half of the 1920s, the colonial power, Spain, later joined by France, fought against the local Berber population in the so-called Rif War. The movement's famous leader Abd el-Krim headed the independent Rif Republic that existed between 1920 and 1926 but was then taken into exile. In 1958 and 1984 the Rif Berbers revolted against King Hassan II and the central authority, whose security forces cracked down on the movement. Tense relations and political neglect of the region under King Hassan II have dominated the relation between the region and central government since then until the more open and integrative policies of current King Mohammed VI.

4 This principle states that a larger and greater body should not exercise functions that can be carried out efficiently by one smaller and lesser, but, rather, the former should support the latter and help to coordinate its activity with the activities of the whole community.

5 These are the Autorité pour la Parité et la Lutte contre toutes les formes de Discriminations (APALD) and the Conseil Consultatif de la Famille et de l’Enfance (CCFE).

References

- Abou El Farah, Tahar. 2016. “Les agences mettent en place leur bras exécutif : 12 agences pour bientôt.” La vie éco, 6.4.2016. http://lavieeco.com/news/politique/les-regions-mettent-en-place-leur-bras-executif-12-agences-pour-bientot.html.

- Akesbi, Azeddine. 2014. “La Constitution et sa mise en oeuvre : gouvernance, responsabilité et (non) redevabilité.” In La nouvelle Constitution marocaine à l’épreuve de la pratique, edited by Omar Bendourou, Rkia El Mossadeq, and Mohammed Madani, 339–365. Casablanca: La Croisée des Chemins/ Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Akesbi, Najib. 2014. “La dimension économique de la nouvelle Constitution, à l’épreuve des faits.” In La nouvelle Constitution marocaine à l’épreuve de la pratique, edited by Omar Bendourou, Rkia El Mossadeq, and Mohammed Madani, 255–282. Casablanca: La Croisée des Chemins/ Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Amnesty International. 2016. “Le Maroc intensifie la répression de la liberté de la presse avec un procès contre le journalisme citoyen.” Amnesty International, January 26. https://www.amnesty.org/fr/latest/news/2016/01/morocco-ramps-up-crackdown-on-press-freedom-with-trial-over-citizen-journalism/.

- Benchemsi, Ahmed. 2017. ‘Mohamed VI, despote malgré lui’ : Pouvoirs, n°145, mars 2013.

- Bendourou, Omar. 2014. “Réflexions sur la Constitution du 29 juillet 2011 et la démocratie.” In La nouvelle Constitution marocaine à l’épreuve de la pratique, edited by Omar Bendourou, Rkia El Mossadeq, and Mohammed Madani, 123–152. Casablanca: La Croisée des Chemins/ Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Bergh, Sylvia. 2013. “Governance Reforms in Morocco - Beyond Electoral Authoritarianism?” In Governance in the Middle East and North Africa: A Handbook, edited by Abbas Kadhim, 435–450. London: Routledge.

- Bland, Gary. 2010. “Elections and the Development of Local Democracy.” In Making Decentralization Work: Democracy, Development, and Security, edited by Ed. Connerley, Kent Eaton, and Paul Smoke, 81–114. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Bouabid, Ali, and Aziz Iraki. 2015. “Maroc: Tensions Centralisatrices.” In Local Governments and Public Goods: Assessing Decentralization in the Arab World, edited by Mona Harb, and Sami Atallah, 47–90. Beirut: The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

- Bratton, Michael, and E. Gyimah-Boadi. 2016. “Do Trustworthy Institutions Matter for Development? Corruption, Trust and Government Performance in Africa.” Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 112, p. 6. http://www.afrobarometer.org/publications/ad112-do-trustworthy-institutions-matter-development-corruption-trust-and-government.

- Brinkerhoff, Derick, and Omar Azfa. 2010. “Decentralization and Community Empowerment.” In Making Decentralization Work: Democracy, Development, and Security, edited by Ed. Connerley, Kent Eaton, and Paul Smoke, 81–114. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Brixi, Hana, Ellen Lust, and Michael Woolcock. 2015. Trust, Voice, and Incentives: Learning From Local Success Stories in Service Delivery in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Catusse, Myriam. 2013. “Au-delà de «l’opposition à sa majesté: mobilisations, contestations et conflits politiques au Maroc.” Pouvoirs, revue française d’études constitutionnelles et politiques 145: 31–46.

- Connerley, Ed, Kent Eaton, and Paul Smoke. 2010. Making Decentralization Work: Democracy, Development, and Security. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Devarajan, Shantayanan, Stuti Khemani, and Michael Walton. 2011. Civil Society, Public Action and Accountability in Africa. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Eaton, Kent, Kai Kaiser, and Paul Smoke. 2010. The Political Economy of Decentralization Reforms: Implications for Aid. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- El Mossadeq, Rkia. 2014. “Les dérives du pouvoir constituant.” In La nouvelle constitution marocaine à l’épreuve, edited by Omar Bendourou, Rkia El Mossadeq, and Mohammed Madani, 9–32. Rabat: La croisée des chemins/ Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Faguet, Jean-Paul. 2011. “Decentralization and Governance.” In Economic Organisation and Public Policy Discussion Papers, 2–13. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Falleti, Tulia G. 2011. “Varieties of Authoritarianism: the Organization of the Military State and its Effects on Federalism in Argentina and Brazil.” Studies in Comparative International Development 46: 137–162. doi: 10.1007/s12116-010-9077-5

- Falleti, Tulia G. 2013. “Decentralization in Time: A Process-Tracing Approach to Federal Dynamics of Change.” In Federal Dynamics: Continuity, Change, and the Varieties of Federalism, edited by Arthur Benz, and Jörg Broschek, 140–166. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- FIDH (Mouvement Mondial des Droits Humains). 2015. Maroc: l’Autorité pour la Parité et la Lutte contre toutes formes de Discrimination - Un projet de loi vidé de substance. Rabat: Mouvement Mondial des Droits Humains.

- Fung, Archon. 2006. Empowered Participation: Reinventing Urban Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit). 2014. Dezentrale Regierungs- und Verwaltungssysteme: bürgernah, demokratisch und leistungsfähig. Eschborn: GIZ.

- Goehrs, Manuel. 2014. L’Expérience Communale au Maroc – De la Jemaa à la libre administration. Rabat: Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

- Goeury, David, Laila Slassi, and Younes Benmoumen. 2017. La responsabilité des élus dans le cadre de la régionalisation avancée. Rabat: Tafra/ TelQuel Media.

- Grävingholt, Jörn, and Christian von Haldenwang. 2016. The Promotion of Decentralisation and Local Governance in Fragile Contexts. Bonn: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE)/ German Development Institute.

- Harb, Mona, and Sami Atallah. 2014. Decentralization in the Arab World Must be Strengthened to Provide Better Services. IE Med Mediterranean Yearbook 2015. Barcelona: European Institute of the Mediterranean.

- Harb, Mona, and Sami Atallah. 2015. Local Governments and Public Goods: Assessing Decentralization in the Arab World. Beirut: The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

- Hoffmann, Anja. 2013. “Morocco between Decentralization and Recentralization: Encountering the State in the ‘Useless Morocco’.” In Local Politics and Contemporary Transformations in the Arab World - Governance Beyond the Center, edited by Malika Bouziane, Cilja Harders, and Anja Hoffmann, 158–177. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jari, Mostafa. 2010. “Local Governance in the MENA Region: Space for (Incremental and Controlled) Change? Yes, Promoting Decentralized Governance? Tough Question.” Journal of Economic and Social Research 12 (1): 9–32.

- Josua, Maria. 2016. “Co-optation Reconsidered: Authoritarian Regime Legitimation Strategies in the Jordanian ‘Arab Spring’.” Middle East Law and Governance 8 (1): 32–56. doi: 10.1163/18763375-00801001

- Kherigi, Intissar. 2017. Devolving Power After the Arab Spring: Decentralization as a Solution. Istanbul: Al Sharq Forum Paper Series.

- LDI (Local Development International). 2013. The Role of Decentralization/Devolution in Improving Development Outcomes at the Local Level: Review of the Literature and Selected Cases, Prepared for the Southeast Asia Research Hub of the UK Department for International Development. Brooklyn: Local Development International.

- Leveau, Remy. 1976. Le fellah marocain, défenseur du trône. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

- Madani, Mohammed. 2014. “Constitutionnalisme sans démocratie : la fabrication et la mise en oeuvre de la Constitution marocaine de 2011.” In La nouvelle Constitution marocaine à l’épreuve de la pratique: actes du colloque organisé les 18 et 19 avril 2013, edited by Omar Bendourou, Rkia El Mossadeq, and Mohammed Madani, 33–100. Casablanca: Editions la Croisée des Chemins/ Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Mainwaring, S., and T. Scully. 1995. Building Democratic Institutions: Party Systems in Latin America. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Mansuri, Ghazala, and Vijayendra Rao. 2013. Localizing Development: Does Participation Work? Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Mohammed VI, King. 2017. “Royal Speech on the Occasion of the Throne Day.” Agence Marocaine de Presse, July 29. http://www.mapnews.ma/en/discours-messages-sm-le-roi/full-text-royal-speech-occasion-throne-day.

- Monjib, Mâati. 2016. “Morocco: Marching Place.” In Five Years on a New European Agenda for North Africa, edited by Anthony Dworkin, 30–38. London: European Council on Foreign Relations.

- Montero, Alfred, and David Samuels. 2004. Decentralization and Democracy in Latin America. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Ojeda García, Raquel, and Ángela Suárez Collado. 2015. “The Project of Advanced Regionalisation in Morocco: Analysis of a Lampedusian Reform.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 42 (1): 46–58. doi:10.1080/13530194.2015.973187.

- Oxhorn, Philip, Joseph S. Tulchin, and Andrew Selee. 2004. Decentralization, Democratic Governance, and Civil Society in Comparative Perspective: Africa, Asia and Latin America. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

- Paciello, Maria Cristina, Habib Ayeb, Gaëlle Gillot, and Jean-Yves Moisseron. 2012. Reversing the Vicious Circle in North Africa’s Political Economy: Confronting Rural, Urban, and Youth-Related Challenges. Washington, DC: The German Marshall Fund of the United States.

- Pérennès, Jacques. 1993. L’Eau et les Hommes au Maghreb - Contribution à une politique de l’eau en Méditerrannée. Paris: Karthala.

- Reifeld, Helmut. 2014. “Vom Machtpolitischen Instrument zum Demokratischen Wert – Dezentralisierung in Marokko.” KAS Auslandsinformation (8): 93–116. http://www.kas.de/wf/doc/kas_38635-544-1-30.pdf?140826151651.

- Sater, James N. 2016. Morocco: Challenges to Tradition and Modernity. New York: Routledge.

- Smoke, Paul. 2010. “Implementing Decentralization: Meeting Neglected Challenges.” In Making Decentralization Work: Democracy, Development, and Security, edited by Ed. Connerley, Kent Eaton, and Paul Smoke, 191–217. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Tomsa, Dirk. 2015. “Local Politics and Corruption in Indonesia’s Outer Islands.” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 171 (2–3): 196–219. doi:10.1163/22134379-17101005.

- Transparency Maroc. 2014. Journée Internationale du Droit d’Accès à l’Information. Appel de Transparency Maroc. Casablanca/ Rabat: Transparency Maroc. http://dai-transparencymaroc.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Appel-de-Transparency-Maroc.pdf.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2016. Arab Human Development Report 2016: Youth and the Prospects for Human Development in a Changing Reality. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

- Waterbury, John. 1970. The Commander of the Faithful: The Moroccan Political Elite: A Study in Segmented Politics. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Wenger, Stéphanie. 2015. “Au Maroc, une bipolarisation sous contrôle du Palais.” Magazine OrientXXI, 19.10.1915.