ABSTRACT

Popular attitudes in support of authoritarian alternatives and weak party systems constitute important threats to democratic consolidation and the stability of new democracies. This article explores popular alienation from established political actors in Tunisia. Under what conditions do citizens support alternatives to the elites in power and the institutional infrastructure of a new democracy? Drawing on an original, nationally representative survey in Tunisia administered in 2017, this article examines three categories of popular attitudes in support of political outsiders.Military interventionism appears in people’s preferences for anti-system politics—the most immediate challenge to the country’s stability and democratic transition. Anti-political establishment sentiments are shown in people’s preferences for an enhanced role of the country’s main trade union as a civil-society alternative to political party elites. Finally, outsider eclecticism is the seemingly incoherent phenomenon of concurrent support for a civil society actor and the military as an ‘authoritarian alternative.’ Anti-establishment sentiments will continue to be an important element in Tunisian post-authoritarian politics, evidenced by the rise to power of Kais Said in the 2019 presidential elections and his 2021 decision to dismiss parliament. In turn, popular support for military intervention may have implications for the country’s domestic security and peaceful transition.

Popular attitudes in support of authoritarian alternatives and non-institutionalized party systems constitute important threats to democratic consolidation and the stability of new democracies. Despite a plethora of studies on levels of trust in democratic institutions, we know far less about citizens’ support for political alternatives beyond the electoral arena in emerging and unconsolidated democracies. Under what conditions do citizens support alternatives to the elites in power and the institutional infrastructure of a new democracy? We focus on political alienation and popular support for political alternatives in instable democracies. Tunisia has emerged as an intriguing case to study anti-system and anti-political establishment sentiments along with their consequences for the electoral battlefield and political instability. While elite compromise has enabled the emergence of a transitional ‘pact’ (Boubekeur, Citation2016; Jermanová, Citation2020), anti-establishment sentiments have remained an important element in Tunisian post-authoritarian electoral politics ever since the 2011 founding elections (Koehler & Warkotsch, Citation2014). In the 2019 presidential elections, the only Arab democracy witnessed a run-off between two political outsiders, Kais Said and Nabil Karoui, beating all other candidates who had support from their party establishments. The rise to power of Kais Said not only brought to the fore deeply held opposition to the party establishment, but also illustrated political uncertainties that have characterized the Tunisian transition to democracy. Ultimately Said dismissed parliament during the political crisis of July 2021, raising doubts as to the sustainability of Tunisia’s democratic experiment.

This article focuses on popular support for political alternatives and unpacks anti-system and anti-political establishment sentiments in Tunisian society. While some contributions to the research programme on democratic consolidation point to the perils of popular alienation, few studies have examined the exact nature of popular support for political alternatives in new democracies. We explore attitudes among citizens that lend themselves to supporting alternatives to the elites in power and the institutional infrastructure of parties and elections in a new democracy. To this aim, we explore two interrelated phenomena. First, we introduce distinct types of popular perceptions in principal opposition to the political establishment and, second, preferences about alternatives to what people see as representatives of that very establishment.

Most importantly, we are interested in popular support for the military’s intervention in politics as empirical evidence for anti-system sentiments in society. Support for military rule, in turn, has a possibly substantial impact for social peace and stability. Keeping the military out of politics remains a necessary condition not only for successful democratization, but also for peaceful political processes. Post-Arab Spring regime trajectories have provided a laboratory of sorts to study the consequences of military interventions in politics, ranging from sustained authoritarian rule (Egypt) to the suppression of large-scale popular dissent (Bahrain) and outright civil war (Syria, Yemen).

Assessing citizens’ support for military intervention is not only relevant for Tunisia and the broader MENA region, but also likely carries implications for the research programme on security studies beyond a narrow view of violent conflicts between states or armed groups in civil war. Understanding public opinion on matters related to domestic security affairs remains key to assessing the prospects and possible catalysts of conflicts. In fact, ‘societal actors often understand the sources of insecurity they face in ways that defer from those of Arab state elites and political regimes’ (Hazbun, Citation2017, p. 656). Prior research on public opinion across the region has shown that, while citizens are generally favourable to democracy, they do resent the uncertainties and insecurity associated with democratic governance (Benstead, Citation2015).

Drawing on data from our original, nationally representative survey as well as insights from the Afrobarometer and Arab Barometer surveys in Tunisia, we conceptualize three categories of popular attitudes in support of political outsiders. First, support for military intervention characterizes the anti-system attitudes of people’s strong opposition to the core tenets of Tunisia’s democratic experiment. It is here where we see the imminent illustration of sentiments threatening the existing political order. Second, anti-political establishment sentiments remain widespread among Tunisians frustrated with the party system and its representatives. Such attitudes fall short of casting doubt on the party system per se, but manifest themselves in popular calls for an enhanced political role of the country’s most influential civil society organization, the Tunisian General Labour Union (Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail, UGTT).

Finally, popular opinion in Tunisia reveals yet another, seemingly incoherent and understudied form of attitudes, which we conceptualize as outsider eclecticism: our empirical insights show that roughly one out of five Tunisians prefer an enhanced political role for both the military and the Tunisian General Labour Union UGTT. That is, they concurrently support a civil society actor and an ‘authoritarian alternative’. This highlights a group of respondents who are prepared to simultaneously support an eclectic assortment of military intervention in politics and anti-establishment alternatives, as long as they represent a change to the status-quo. Such attitudes provide the foundations of support for outsider eclecticism.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows: we first briefly discuss the literature on democratic consolidation to introduce our premises for the study of attitudes on perceived political alternatives, namely anti-system sentiments, anti-political establishment attitudes, and eclectic attitudes. In a second part, we review the empirical scope conditions and conflict dynamics in Tunisia’s emerging democracy. A third part draws on Afrobarometer and Arab Barometer data and our own original survey to explore the attitudinal foundations of support for political outsiders in Tunisia’s transition to democracy. A final part summarizes this article’s findings and suggests paths for further research.

Democratic consolidation and support for political outsiders

Democratic consolidation is crucial for the stability of emerging democracies and the prevention of authoritarian reversals. Narrow conceptualizations of democratic consolidation focus on elites’ acceptance of democratic institutions as ‘the only game in town’ (Przeworski, Citation1991), while more substantive conceptualizations emphasize citizens’ commitment to democratic institutions, the vibrancy of civil society, and economic development, among others (Linz & Stepan, Citation1996; Merkel, Citation2004; Morlino, Citation1998). Scholars have also argued that democratic consolidation requires the institutionalization of party systems (Mainwaring & Scully, Citation1995).

A prominent strand of this literature highlights the importance of citizens’ attitudes for successful democratic consolidation. As Gunther et al. (Citation1995, p. 17) put it: ‘If a significant portion of a population were to question the legitimacy of a regime and its key institutions, reject democratic rules of the game, or regard an authoritarian alternative as preferable to the current democratic regime, we would conclude that consolidation is incomplete, despite the absence of behavioural manifestation of this political alienation’. Similarly, Linz and Stepan argue that a democratic regime is consolidated when ‘the support for antisystem alternatives is quite small or more or less isolated from the pro-democratic forces’ (Linz & Stepan, Citation1996, p. 6).

The focus on attitudinal dimensions of democratic consolidation is echoed in a well-established research programme that warns about the adverse effects of low levels of trust in democratic institutions for democratic consolidation. What is missing, however, is an understanding of which alternatives (outside of electoral politics) citizens support in emerging democracies. In this article, we are primarily interested in unpacking citizens’ support for these alternatives. We examine the attitudes shaping citizens’ perceptions of political agents in government and institutional alternatives to the political establishment. One will be able to leverage such empirical data to explore the social sources of political instability in emerging democracies.

Survey research on popular attitudes has inspired an empirically rich research programme across several world regions – namely Latin America, sub-Sahara Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa. Often drawing on cross-country data provided by large-scale survey research projects – such as the World Value Surveys, the Pew Research Center, and regional ‘Barometer’ projects (Latinobarometer, Afrobarometer, Arab Barometer) – scholars have been particularly interested in evidence for the lack of trust in democratic institutions. Yet, largely focusing on the absence of popular trust in political institutions and elites falls short of generating knowledge about the content of popular attitudes on which anti-system or anti-establishment projects can grow and succeed. In our aim at unpacking attitudes in support of political outsiders, we are therefore interested in the popular preferences about alternatives to democratic institutions and elites.

Where citizens develop attitudes in an antagonistic relationship of the ‘pure people’ and ‘corrupted’ elites (Mudde, Citation2004), they will develop preferences in regards to two levels of the polity: the core tenets of the political system itself or the institutional (parties) and individual representatives (elites) of the political system. The first perspective prompts us to look at anti-system opposition while the second refers to anti-political establishment attitudes. With regards to a country’s existing party system, citizens may oppose the extant parties versus the very notion of a multi-party system (Poguntke, Citation1996, p. 324); according to our conceptualization, the former would emphasize anti-establishment attitudes, the latter anti-system opposition.

The notion of anti-system opposition refers to the rejection of the core ideological and institutional elements of the political order. In a classical definition, ‘an anti-system opposition abides by a belief system that does not share the values of political order within which it operates’ (Sartori, Citation1976, p. 133). Drawing on this classical definition, the notion of anti-systemness was predominantly employed for the study of radical political parties in Europe, including organizations with fascist, right-wing, or left-wing agendas (see, for instance, Cappoccia, Citation2002; Keren, Citation2000; Zulianello, Citation2018). And yet, anti-system opposition can exist in any type of political system as genuine pro-democracy preferences constitute anti-systemic opposition in authoritarian regimes (Albrecht, Citation2013). In an established democracy, anti-system attitudes would challenge the ideas and institutional practices of electoral competition, liberalism, human rights, or the rule of law. Anti-systemness in democracies refers to popular preferences for an authoritarian political alternative, such as support for political parties, movements, and institutions associated with authoritarian governance.

Support for military rule is arguably the most direct measure for such anti-system attitudes in emerging democracies. For one, military apparatuses typically have been part and parcel of the authoritarian regimes preceding democratic transitions, and civilian control over such militaries remains a necessary condition for democratic consolidation (Agüero, Citation1995; Hunter, Citation1997). Conversely, research has shown that the rise of populist leaders such as Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro can strengthen the political role of the military (Hunter & Vega, Citation2021). Across the Middle East and North Africa, military apparatuses have been involved in authoritarian politics at various degrees both during a protracted period of stable authoritarian rule (Cook, Citation2007; Koehler, Citation2017), as well as in the aftermath of the Arab Spring uprisings (Albrecht et al., Citation2016; Gaub, Citation2017). Clearly, support for what Alfred Stepan (Citation1973) coined the military’s ‘role expansion’ in politics and society would remain the most direct indicator of popular dismissal of the core tenets of democratic rule.

Rather than the core tenets of the political system, anti-establishment sentiments are directed against the ‘entire class of individuals wielding power’ (Barr, Citation2009, p. 31; see also Schedler, Citation1996; Ignazi, Citation1996). Such anti-political establishment sentiments can be imprecise as to whether citizens’ critical narratives are directed against political elites or against the parties within which political elites operate (Kenney, Citation1998). In the United States, for instance, populist narratives against ‘the swamp’ in the country’s capital city are widespread among candidates on both the Republican and Democratic party tickets. In contrast, both run-off candidates for presidential elections in Tunisia – Kais Said and Nabil Karoui – ran their campaigns outside of the established political parties at the time. While anti-political establishment opposition has been measured primarily by addressing popular views on existing parties (Poguntke, Citation1996), less emphasis was put on popular preferences for alternatives to these parties and their representatives. In emerging democracies, anti-political establishment sentiments will prompt citizens to dismiss authoritarian alternatives (as in anti-system opposition) and encourage them to look for alternatives in their countries’ civil societies: social movements, labour unions, advocacy groups, and the like. Such popular attitudes would culminate in preferences for different political elites and parties, but not fundamental changes that would lead to the destruction of the party system.

Finally, in exploring attitudes in principal opposition to the system and its political establishment, we consider whether or not citizens propose discrete choices regarding those political alternatives. One would typically expect such attitudes to be selective in that citizens discriminate between authoritarian (anti-system opposition) or civil-society alternatives (anti-establishment opposition). Yet, we also consider the prevalence of eclectic attitudes, which is an opposition of principle where citizens voice preferences in favour of any political outsider, whether they are authoritarian or civil-society actors (see ).

Table 1. Popular support for political alternatives in emerging democracies.

Where citizens in a democracy voice preferences for both anti-system and anti-establishment opposition, they would consider both civil-society and authoritarian alternatives to the established political parties and politicians. What appears to be a rather ambiguous mix of preferences reveals the most direct disposition for supporting political alternatives: a general support for political outsiders and an openness to authoritarian alternatives.

Insiders and outsiders in Tunisian party politics post-2011

Tunisia provides an ideal context for probing the questions we raise in this article. First, it is an emerging democracy and an ideal case to explore anti-system and anti-establishment attitudes beyond the conventional focus on consolidated democracies (Pappas, Citation2019). Second, Tunisia is the only country that has undergone a successful democratic transition following the 2010–2011 Arab uprisings and hence remains an important case for understanding democratic contestation in the Arab world (Bellin, Citation2019; Hassan et al., Citation2019). Third, Tunisia’s emerging political landscape is characterized by a vibrant, albeit nascent, party system as well as the presence of politically important outsiders to that party system (Berman & Nugent, Citation2019). This presents a unique opportunity to explore popular attitudes towards parties and electoral politics, on the one hand, and politically important outsiders beyond the realm of electoral politics, on the other hand, at a time where the country’s democratic transition process remains uncertain (Günay & Sommavilla, Citation2019). This section introduces the major actors in Tunisia’s emerging party system as well as two key actors that stand outside this party system, namely the military and the UGTT.

Party politics

Since Ben Ali’s removal in 2011, Tunisians elected a constituent assembly and drafted a new constitution providing the basis for a democratic transition (Jermanová, Citation2020; Zemni, Citation2015). The following decade witnessed a turbulent, albeit largely peaceful political process leading to the writing of a new constitution, the formation of a party system, two legislative assemblies, and two rounds of presidential elections in 2014 and 2019 respectively.

Until the most recent legislative elections of 2019, two parties dominated Tunisia’s party system and formed a coalition government in 2014: Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes (Yardimci-Geyikçi & Tür, Citation2018). Ennahda, led by Rachid Ghannouchi, is an Islamist party, legalized in the wake of the 2011 uprising. The party has its roots in the Islamist Ennahda movement that had been heavily repressed under Ben Ali’s rule (Wolf, Citation2017). Nida Tounes, founded by former interim prime minister Beji Caid Essebsi, is a secularist, anti-Ennahda, ‘big tent party’ (Chomiak & Parks, Citation2020, pp. 673f) that includes ‘people as diverse as former RCD members, leftists, trade unionists, independents, secular women activists, and veteran members of the Destour movement’ (Wolf, Citation2017, p. 153). Despite having originally won 86 seats in the 2014 legislative elections, Nidaa Tounes fractured internally as a result of its decision to enter into a coalition government with Ennahda. While Nidaa Tounes was united in its opposition to political Islamism, it was divided over important issues like economic policy and transitional justice.

As we will show below, the 2019 elections revealed widespread dissatisfaction with Tunisia’s political establishment. Voters punished Nidaa Tounes and Ennahda and supported a new set of political parties. For their part, the 2019 presidential elections featured the decline of established party candidates and the entry of two prominent outsiders: Nabil Karoui and Kais Said. The two men won the first round of presidential elections and competed in a run-off, where Said was elected President. Said ‘argued that corrupt political parties hijacked the revolution and that power needed to be devolved directly to the people’ (Grewal & Hamid, Citation2020, p. 15). Ennahda’s candidate, Abdul Fattah Mourou, came in third in the first round of elections, winning only 12.9 per cent of the vote. As one Ennahda party official put it, the ‘Tunisian voter directed a strong message to the entire political class … saying that it is not satisfied with its performance’ (Al-Kalbusi, Citation2019, p. 3).

Beyond parties and electoral politics

Two important political actors, namely the UGTT and the military, loom large beyond Tunisia’s electoral system. Both actors have assumed important roles in the early stages of Tunisia’s break with the authoritarian past: the military stayed on the sideline amid popular mass contestation, hence preventing a return to authoritarianism as a consequence of a possible takeover of power, as witnessed in Egypt (Bellin, Citation2019; Holmes & Koehler, Citation2020). The UGTT, in turn, played a prominent role in the early transition period as a member of the National Dialogue, negotiating the formation of the country’s constitution and democratic institutions (Hartshorn, Citation2019).

Boasting over 600,000 members, the UGTT is the largest and most organized civil society organization in Tunisia. Despite its status as a ‘legacy union’, ‘allied with the previous authoritarian regime that survive[s] in the democratic era’ (Caraway et al., Citation2015, p. 14), the UGTT emerged as a key player in the transition from authoritarian rule (Bishara, Citation2020). Following pressure from the regional and sectoral unions, the UGTT’s leadership supported anti-Ben Ali protests, and regional unions played a central role in Ben Ali’s ouster (Langohr, Citation2014; Yousfi, Citation2018). Over the course of the transition, the UGTT assumed an ‘outsized role’ (Hartshorn, Citation2016, p. 31), pursuing a dual role as a political broker and a pressure group, sometimes flexing its organizational power to press for public sector wage increases and oppose austerity measures imposed by the international financial institutions.

In 2015, the UGTT, along with three other civil society organizations, won the Nobel Peace Prize for its contribution to peaceful democracy-building following Ben Ali’s ouster in 2011. Posturing as a power broker, the union mediated conflict between competing political parties at a critical juncture in the country’s transition (Bishara, Citation2020; Yousfi, Citation2018). Today, the UGTT remains highly engaged politically, if not electorally. Despite some initial ambiguity about the precise nature of its engagement with the 2019 elections, the UGTT ultimately announced that it would not support any candidates or parties (Bishara & Grewal, Citation2021). Instead, the union capitalized on its nationwide network and deployed thousands of election observers in both parliamentary and presidential elections.

The Tunisian military has played a less visible, albeit similarly important, role in Tunisia’s democratic transition. Most importantly, the military did not support Ben Ali during the uprising. Scholars somewhat disagree as to whether the military actively contributed to the ousting of Ben Ali (Brooks, Citation2013; Jebnoun, Citation2014) or simply stayed on the sidelines to withdraw support from the authoritarian incumbency (Holmes & Koehler, Citation2020; Pachon, Citation2014). Compared to the active interventions of militaries in other MENA countries, the Tunisian military has kept a relatively low political profile, which certainly contributed to its largely positive image among Tunisians.

And yet, officers and the military as a corporate apparatus have a history of engagement in politics, including the policing of large-scale unrest and bread riots from 1978 onwards, the recruitment of officers for political offices, and an aborted military coup in 1987 (Albrecht, Citation2020). More recently, former officers have moved to enter the fray of politics by establishing a political party (Al-Hilali, Citation2019). While ultimately unsuccessful, this party project remains indicative of the military’s standing in politics as an ‘elephant in the room’, with popular support for its enhanced role in politics in particular in times of crisis and uncertainty (Albrecht et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, the military’s deepened engagement in politics would possibly be consequential for the country’s prospect for democratic consolidation, but also – as the Egyptian experience reveals – for social peace and security.

Democratic disenchantment in Tunisia

Tunisia’s democratic transition was made possible by compromises between elites in the aftermath of the 2011 revolution. However, many Tunisians, particularly on the economic margins of society, have felt left out of the political process (Koehler & Warkotsch, Citation2014). Political discontent has become manifest in declining support for democracy (Meddeb, Citation2018). Less than 41 per cent of the eligible population voted in the 2019 parliamentary elections, and approximately 25 per cent of the parliamentary vote went to parties that promoted anti-system rhetoric (Grewal, Citation2019b). As enthusiasm for democracy has waned since the revolution, Tunisians have become disillusioned with the political establishment and increasingly open to a range of political alternatives (Grewal & Monroe, Citation2019). In this section, we draw on different sources, including available survey data, to describe Tunisians’ growing democratic disenchantment, some consequences of these shifts in terms of the emergence of new electoral alternatives, as well as the rise of street politics.

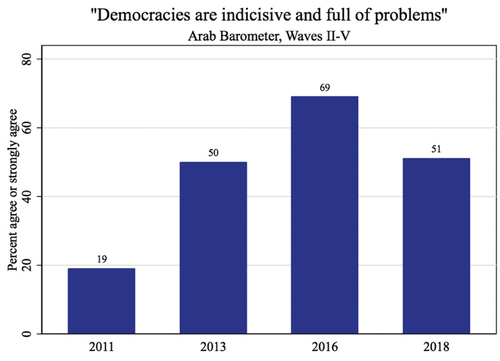

Disenchantment with democracy has increased significantly in the years following the 2011 revolution. According to the Arab Barometer, 19 per cent of respondents agreed democracy was indecisive and full of problems in 2011 compared to 50 per cent in 2013, 69 per cent in 2016, and 51 per cent in 2018 (see ). Growing frustration with democracy is also shown in the Afrobarometer data. The proportion of Tunisians who say their country is not a democracy as of 2018 was 29 per cent, up from 14 per cent in 2015. Disenchantment also showed in levels of electoral participation. The 2011 founding elections drew only 52 per cent of eligible voters to the polls; 68 per cent then participated in 2014, but turnout decreased again to a mere 42 per cent in the 2019 elections. Participation in presidential elections show a similar pattern, with turnout decreasing from around 60 per cent in the two rounds of the 2014 election to around 50 per cent in 2019.

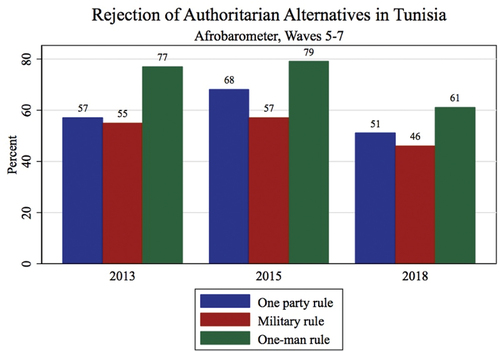

Support for authoritarian alternatives to the status quo are also on the rise. Various waves of the Afrobarometer surveys asked respondents about their support for one-party, military, and one-man rule as major authoritarian alternatives to democracy. As shows, the percentage of respondents rejecting these alternatives remains generally low, implying that between 40 and 50 per cent of Tunisians consider one-party or military rule as possible alternatives to democracy. Moreover, rejection of authoritarian alternatives has declined for all three types of rule from 2015 to 2018. As of 2018, only 46 per cent of the population rejected military rule, which is down 11 points from 2015. During that same period, opposition to one-man rule decreased from 79 per cent to 61 per cent, and opposition to one party rule decreased from 68 per cent to 51 per cent (see ). Approximately 65 per cent of the country supported at least one out of these three authoritarian alternatives as of 2018.

Democratic disenchantment has also manifested itself in increased electoral support for political parties promoting anti-system rhetoric. Frustration on the margins of the political spectrum with the compromises made by Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes since 2014 led to the emergence of anti-establishment challengers in the 2019 elections. Ennahda lost support among their social constituency of conservative citizens as a consequence of political moderation in the coalition government (Ash, Citation2021). The hardline Salafist al-Karama coalition presented a theocratic alternative to the status quo and emerged as Ennahda’s first major Islamist competitor in 2019 by taking 21 seats and coming in fourth in the parliamentary elections (Torelli et al., Citation2012).

Dissatisfaction with the compromises made by Nidaa Tounes in the secular camp led to party fragmentation and the demise of the 2014 coalition of Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes. For example, Nabil Karoui, who helped create Nidaa Tounes in 2013, founded a new party in 2019 called Qalb Tounes after splitting from Nidaa Tounes in 2017 (Grewal, Citation2019a). Furthermore, new parties have emerged that have called for the dissolution of Ennahda and the return of the authoritarian system that existed under Ben Ali’s government. Such rhetoric has characterized, for instance, the Free Destourian Party that won 6.63 per cent of the parliamentary vote in 2019 (Grewal & Hamid, Citation2020).

While support for authoritarianism in Tunisia is growing, it is important to note that opinions polls still show substantial expressions of support for the democratic system and the norms that go with it. According to Afrobarometer data in 2018, 68 per cent of Tunisians continue to believe they live in a democracy, and the majority believe that basic freedoms and civil liberties have actually improved since the revolution. Popular perceptions towards executive overreach, in turn, are mixed. While 74 per cent of Tunisians favour presidential term limits, only 56 per cent say the President must always obey the rule of law. Moreover, not all Tunisians who support democratic norms support the political establishment – that is, the political parties and politicians that control the government. Many Tunisians who support the democratic system have become increasingly disenchanted with Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes for their failure to address major socioeconomic and political problems.

While this consensus-based coalition of 2014 made the democratic transition possible (Jermanová, Citation2020), the formation of large parliamentary coalitions with actors that had different opinions on critical social and economic issues created gridlock in the legislature. Consequently, parliament failed to confront the country’s problems with economic stagnation and corruption (Boubekeur, Citation2016; Brumberg & Ben Salem, Citation2020). Rates of unemployment hovered around 15 per cent in 2018 (Meddeb, Citation2018). According to Afrobarometer data, 72 per cent of Tunisia’s population rated the economy as being bad or fairly bad in 2018, and the government had very low approval ratings on issues such as managing the economy, fighting corruption, and creating jobs.

Approval ratings for Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes, as well as for these parties’ figureheads, declined in the process. According to the International Republican Institute, disapproval of Ennahda’s leader Rachid Ghannouchi rose from approximately 20 per cent to a little less than 70 per cent from 2011 to 2017, and disapproval of Nidaa Tounes’ founder Caid Essebsi rose from approximately 15 per cent to 50 per cent in the same time period (Grewal & Hamid, Citation2020). The proportion of respondents who reported they had no trust at all in political parties rose from an (already high) 38 per cent in 2011 to 59 per cent in 2016 and to 72 per cent in 2018 according to the Arab Barometer. Afrobarometer data also showed 81 per cent of Tunisians in 2018 did not feel close to a political party, and 79 per cent said they either would not vote or would not know who to vote for if an election were held the next day.

By 2019, the establishment began to crack, and suffered losses at the polls. Nidaa Tounes collapsed as the party has remained divided over important policy issues (Grewal & Hamid, Citation2020). From 2014 to 2019, 61 out of the 86 parliamentarians associated with the party left and joined new parties; most notably, 43 parliamentarians joined Tahya Tounes and 14 joined Mashrou Tounes. All three parties fared badly in the 2019 elections, with Nidaa Tounes picking up only three seats and the other two parties 14 and four seats, respectively. Ennahda also suffered a decline, dropping from 69 seats in 2014 to 52 in 2019. While the supporters of the 2014 coalition were able to win enough seats in 2019 to create a new government, many new parties and independent politicians emerged, which further reflected people’s discontent with the establishment

One example of this is the independent politician Kais Said who won the 2019 presidential elections. His campaign tapped into the anger felt within marginalized regions of Tunisia over the asymmetrical distribution of power and resources between the northeastern coastal region and the rest of the country (Buehler & Ayari, Citation2018; Grewal, Citation2019a). Said used grievances over this issue, along with socially conservative rhetoric and promises to fight corruption, to mobilize people from marginalized regions of the country. In his 2019 campaign, he claimed that the country’s problems were caused by the established political parties’ domination of the government. According to Laryssa Chomiak, ‘[h]e earned adulation for his non-establishment status, his commitment to public service, and his disinterest in the material gains of joining the elite political class’ (Chomiak, Citation2019). Said’s success in the presidential elections showed that such anti-establishment rhetoric found a very receptive audience in 2019.

Anti-establishment attitudes also show high levels of support for civil society organizations that previously did not directly partake in parliamentary elections. Civil society organizations were critical in mobilizing protestors during the revolution, and hundreds of new civil society organizations have emerged since 2011 in support of a variety of different socioeconomic and political causes from feminism to unemployment to transitional justice (Antonakis-Nashif, Citation2016). One of the most important civil society organizations is the UGTT. As a labour organization that was critical in Tunisia’s independence movement in 1956 and in the mobilization of protestors during the 2011 revolution, the UGTT has enjoyed widespread support historically (Yousfi, Citation2018). The organization has been involved since the revolution not only in crafting compromise between political parties, but also in the organization of protests (Zemni, Citation2013). And yet, the organization stayed above the political fray of party politics by not directly nominating candidates in previous parliamentary and presidential elections (Bishara & Grewal, Citation2021).

According to our 2017 survey data, approximately 55 per cent of the public view the UGTT as being independent from other political parties while only 29 per cent view it as not being independent, and approximately 72 per cent of the population believes the UGTT has a role to play in resolving political and social issues. While the majority view the UGTT as an independent force not associated with political parties, our data also show that 34 per cent of the Tunisians have expressed support for the UGTT to participate directly in elections in the future. Such high levels of support for electoral alternatives imply widespread dissatisfaction with existing parties and hence anti-establishment attitudes.

Finally, democratic disenchantment is reflected in the fact that citizens are increasingly turning towards political activities outside of the electoral arena, specifically street politics. While voting rates have declined, the number of protests increased in the years after the revolution – in particular socioeconomic protests in marginalized regions of the country. Tunisians have increasingly resorted to protests to express their discontent. Research on protest activity shows an increase in the number of yearly protests from 183 in 2011 to 571 in 2016, while the proportion of socio-economic protests as a percentage of all protests increased from 20.7 per cent in 2011 to 69.8 per cent in 2016 (Jöst & Vatthauer, Citation2020, p. 76). According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, in 2011, there were 4.58 socioeconomic protest events per one million inhabitants in the south and interior of the country, a number that increased to 72.1 such protests per one million inhabitants by 2016 (Vatthauer & Weipert-Fenner, Citation2017).

Some protestors have been motivated by anti-establishment attitudes. For example, the women’s rights protests in the summer of 2012, led by the Tunisian Association of Women and the UGTT, mobilized against the Ennahda-led troika government’s attempt to establish a difference between genders in the constitution (Antonakis-Nashif, Citation2016). Other protestors were motivated by anti-system attitudes. In the summer of 2013, protests against the troika government led by the National Salvation Front were endorsed by members of Nidaa Tounes, many of whom have called on the military to push Ennahda out of power. While protestors have differed in terms of their goals, they have shared a common animosity towards the current status quo and have sought non-electoral means to influence the body politic.

Anti-system, anti-establishment, and anything but

As we have shown in the last section, democratic disenchantment can find different empirical expressions. In this section, we inquire into popular attitudes driving these different expressions. Drawing on original survey evidence, we describe three distinct currents of popular preferences for alternatives to the political status quo: support for military intervention in politics, anti-establishment sentiments, and outsider eclecticism. Empirically, we are particularly intrigued by what we conceptualized earlier as attitudes in support of outsider eclecticism held by a category of respondents who simultaneously support non-electoral authoritarian alternatives and civil-society based electoral challenges at the same time.

We base this analysis on our nationally representative telephone survey conducted in 2017 by One to One Polling, a survey firm in Tunisia. The survey was administered in Tunisian Arabic and consisted of 48 questions in total. The questions on support for a stronger political role of the military and an electoral challenge by the UGTT are of particular importance. We asked respondents to (strongly) agree or (strongly) disagree with the statement that ‘officers from the Tunisian military should serve in government’ to gauge support for a political role of the military and with the statement ‘the UGTT should directly present candidates for political office’ to measure support for the UGGT’s entry into electoral politics. In the following, we use these two questions to outline the extent of anti-system attitudes, anti-establishment sentiments, and attitudes in support of outsider eclecticism in Tunisia at the time of our survey.

Anti-system attitudes, to begin with, find expression in support for non-majoritarian, extra-electoral alternatives. As shown above, disenchantment with democracy reached a high point in 2016, with more than two-thirds of respondents voicing doubts about the functioning of democracy. Democratic disenchantment has galvanized support for different authoritarian alternatives, including support for military intervention. In our survey data, just above 40 per cent of respondents support the idea of military officers serving in government. Anti-establishment sentiments, by contrast, are different but equally widespread in Tunisia. As we have shown above, support for the political parties that have dominated Tunisian politics since at least 2014, has gradually decreased. Consequently, Tunisian voters were more likely to support outsider challengers in the electoral arena – a trend that was on display in the 2019 legislative and presidential elections. In our own survey, we find that 34 per cent of respondents supported or strongly supported an electoral challenge by the UGTT.

Thus far, these findings are not particularly surprising. We know a section of the Tunisian population has grown disillusioned with democracy and this disillusionment feeds popular support for an authoritarian alternative, such as a stronger role of the military (Albrecht et al., Citation2021). We also know political parties that have dominated Tunisian politics over the last years were in crisis, illustrated by the 2019 election results (Wolf, Citation2017). However, looking at disillusionment with democracy or anti-establishment sentiments alone risks overlooking a third current in Tunisian public opinion, namely what we refer to as ‘outsider eclecticism’.

Outsider eclecticism combines the anti-establishment thrust of opposition against the party-political elite with the illiberal element of support for an extra-electoral alternative. While it would be easy to dismiss such views as an instance of cognitive dissonance, we suggest taking these views seriously because the phenomenon affords us interesting insights into the drivers of popular discontent with the political status quo. In our survey, 20 per cent of all respondents support both military intervention and an electoral challenge by the UGTT.

is a graphical representation of the distribution of these three categories in our data with the size of each square representing the relative distribution of each category. Respondents holding anti-system attitudes are the largest single group with about 40 per cent (N = 423). 34 per cent (N = 352) of respondents hold anti-establishment attitudes. Supporters of outsider eclecticism, however, make up the largest group (N = 211, or 20 per cent) when taken together with those respondents who exclusively support military government (N = 212, or 20 per cent). Respondents who support an electoral challenge by the UGTT, but not military government, finally, make up a significantly smaller group with about 14 per cent of respondents (N = 141). In the next section, we examine the drivers of these different sets of attitudes and demonstrate that the category of outsider eclecticism is indeed empirically relevant.

Drivers of outsider eclecticism

Why does political disenchantment lead citizens to support any alternative to the political status quo in some cases and specific alternatives in others? Put differently, what are the drivers of outsider eclecticism as opposed to anti-establishment or anti-system attitudes? In this section, we draw on our original survey data to explore this question. This effort is explorative in that we do not present a theoretically inspired causal explanation of variation among different attitudinal preferences. Our main aim is to show that the category of outsider eclecticism is indeed a meaningful empirical category driven by a distinct set of factors.

The phenomenon of outsider eclecticism implies two distinct sub-questions: first, disenchantment does not automatically translate into support for any alternative, be it anti-establishment, anti-system, or the combination of both. Instead, citizens might just disengage from the political process altogether. Of the 486 respondents in our survey who abstained in the 2014 elections, 189 (or 39 per cent) do not support either anti-system or anti-establishment alternatives. The first question therefore is why some disenchanted citizens support outside options, while others do not. Second, disenchanted citizens might support different alternatives. Of the 564 respondents in our survey who support some kind of outsider alternative, 352 (or 62 per cent) are in favour of UGTT candidates in elections, 423 (or 75 per cent) want to see officers in government, and 211 (37 per cent) want both.

These two questions are interdependent. Different dimensions of political disenchantment might influence whether respondents support different alternatives and which alternative they support; crucially, some factors might drive one stage of the decision, but not the other, or they might impact the different levels differently. Hence, we can only arrive at a realistic assessment of the drivers of anti-system, anti-establishment, and attitudes in support of outsider eclecticism if we control for the drivers of support for outsider alternatives in general.

We address these issues by specifying two-stage models controlling for sample selection. This empirical approach allows us to examine the drivers of support for different types of alternatives while controlling for factors increasing the likelihood that respondents will support any challenge in the first place. More specifically, we created an anti-system dummy variable capturing whether respondents agreed or strongly agreed that officers should serve in government but did not endorse an electoral challenge by the UGTT; we created the same variable for anti-establishment sentiments, which is coded 1 if respondents (strongly) agreed with the UGTT fielding candidates, but not with officers serving in government. The dummy captures simultaneous support for officers in government and UGTT-fielded candidates in elections. Finally, the selection equations in each model capture whether respondents supported any of these three alternatives.

We estimate three two-stage probit models, one examining anti-system attitudes, one anti-establishment sentiments, and one outsider eclecticism. All three models analyse the impact of three main sets of factors. First, we look at attitudes towards the formal political process as captured by self-reported electoral abstention in the 2014 parliamentary election (non-voter), as well as support for Nidaa Tounes in the same contest. Second, we examine two variables capturing different dimensions of attachment to Tunisia’s emerging democracy, namely whether or not respondents participated in the 2011 revolution (protest), and whether they emphasize socio-economic outputs, rather than political rights when asked about their understanding of democracy (output democracy). A last set of factors examines whether or not respondents are (former) members of the UGTT or the armed forces (UGTT member and military service, respectively), and whether or not respondents believe the UGTT or the military have a positive influence on economic issues (UGTT or military influence). In the selection equations, we additionally control for a range of demographic variables, including gender, employment status, geographical location, age, education, and income.

We highlight two main findings in . First, the category of outsider eclecticism represents a distinct current of public opinion. Comparing the three main equations suggests there is no single explanation for anti-system attitudes, anti-establishment attitudes, and attitudes in support of outsider eclecticism. Model 1 suggests anti-system attitudes are more prevalent among those with an understanding of democracy that focuses on socio-economic output, rather than institutional processes. Moreover, respondents who participated in the 2011 revolution are less likely to support military rule. Model 2 shows that voting for Nidaa Tounes as well as membership in the UGTT are negatively associated with support for an electoral challenge by the UGTT. In Model 3, finally, we find very different drivers of outsider eclecticism: Nidaa voters in 2014 are more likely to endorse eclectic preferences for political alternatives, as are those who think the UGTT and the military have a positive influence on the economy. By contrast, (former) military service members are less likely to be supporters of outsider eclecticism.

Table 2. Two-stage probit models with sample selection.

Second, we find interesting and largely consistent effects across the selection equations. When compared to supporters of Ennahda and smaller parties, non-voters are more likely to support an outsider alternative; women also consistently appear more prone to support outsider challenges. At the same time, respondents who protested in 2011 and more highly educated and older Tunisians are less likely to support an alternative to the status quo; none of these factors, however, explains which alternative they support in particular, with the exception of the non-voter and protest variables in Model 1. This supports our choice of modelling this dynamic as a two-stage process.

These findings suggest two empirical conclusions. First, we find broad attitudinal patterns that will be familiar to students of Tunisian politics. Support for outsider alternatives, irrespective of whether they are anti-system, anti-establishment, or both, is more widespread among less educated, younger respondents in the more marginalized geographical areas of the country. We also find that women and non-voters are more likely to look for alternatives outside of the electoral arena, while those having participated in the 2011 revolution are less likely to do so. This suggests a social profile of disenchanted citizens, which is largely in tune with previous findings on the determinants of formal political participation (e.g., Franklin, Citation2002).

Beyond such broad patterns, our analysis reveals that disenchantment with the status quo in Tunisia does not lead to support for a single political alternative. Indeed, disenchanted Tunisians have distinct views on which alternatives they support. This has important theoretical and policy implications. Theoretically, it underscores the need to explore the drivers of support for different alternatives to the status quo, as we have started to do in this article. It also implies that scholars need to go beyond the predominant focus on socio-economic marginalization as the basis for understanding Tunisians’ attitudes towards alternatives to the status quo. While socio-economic marginalization may explain citizens’ propensity to support political alternatives to the status quo, this does not explain variation in the types of political preferences they endorse.

Conclusion

Drawing on original survey data from Tunisia, this article has shed light on the foundational attitudes in support of extra-electoral political alternatives in an emerging democracy. In doing so, it identified three distinct sets of attitudes that represent support for alternatives to the status quo: (1) support for military intervention in politics as evidence for anti-system attitudes; (2) anti-establishment attitudes, reflected in support for a civil society alternative; and (3) outsider eclecticism, reflected in support for both an authoritarian and civil society alternative.

These findings allow us to make several contributions to the literature on democratic consolidation. Past studies have warned against the erosion of trust in democratic institutions and established parties (Galston, Citation2018; Pappas, Citation2019), and increased popular support for authoritarian alternatives for democratic consolidation. At the same time, however, scholars of democratic consolidation have largely neglected the political alternatives that citizens are willing to support. Understanding the nature of political alternatives that citizens are willing to support helps us theorize threats to democratic stability.

These findings are relevant not only for scholars of democratic transitions, but also for observers interested in political stability and social peace across the southern Mediterranean region. As the Egyptian example reveals, the military’s possible intervention in politics does not just mark the transition of power to a political group underrepresented in government; it paved the way for more repressive state-society relations under strongman Abdelfattah Sisi. As Tunisia has thus far avoided the fate of countries plagued with direct military rule, popular support for an enhanced role of the military suggests Tunisia’s status as an exception in a largely authoritarian environment across the Arab world is not a foregone conclusion.

Finally, this article contributes to the literature on democratic transitions. While past studies on popular attitudes in the context of democratic transitions and democratic backsliding have tended to focus on attitudes towards democratic institutions such as levels of trust and support (see for examples Norris, Citation2011; Pietsch et al., Citation2014), we show why it is important to also focus on attitudes towards establishment and system alternatives. A country in transition may not only face difficulty consolidating its democratic institutions because citizens fail to express support for democracy or because the political establishment is perceived as failing in terms of governance, but because attractive alternatives exist to the status quo that can destabilize the democratization project. Support for authoritarian or antisystem alternatives is only one of several possible forms of opposition that can destabilize an emerging democracy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agüero, F. (1995). Soldiers, civilians, and democracy: Post-Franco Spain in comparative perspective. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Albrecht, H. (2013). Raging against the machine: Political opposition under authoritarianism in Egypt. Syracuse University Press.

- Albrecht, H. (2020). Diversionary peace: International peacekeeping and domestic civil-military relations. International Peacekeeping, 27(4), 586–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2020.1768073

- Albrecht, H., Bufano, M., & Koehler, K. (2021). Role model or role expansion? Popular perceptions of the military in Tunisia. Political Research Quarterly, online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129211001451

- Albrecht, H., Croissant, A., & Lawson, F. (2016). Armies and insurgencies in the Arab Spring. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Al-Hilali, A. (2019, July 31). Former military officers jump into Tunisia’s political arena. Al-Monitor. https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/07/tunisia-army-veterans-political-party-elections-neutrality.html

- Al-Kalbusi, J. (2019, September). Siyasiyun yuqayimun nata’ij al-ri’asiya (Politicians evaluate the results of the presidential [elections]). al-Sabah, 17, 3.

- Antonakis-Nashif, A. (2016). Contested transformation: Mobilized publics in Tunisia between compliance and protest. Mediterranean Politics, 21(1), 128–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2015.1081447

- Ash, K. (2021). How did Tunisians react to Ennahda’s 2015 reforms? Evidence from a survey experiment. Mediterranean Politics, 1–25, online first. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2021.1894541

- Barr, R. (2009). Populists, outsiders and anti-establishment politics. Party Politics, 15(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068808097890

- Bellin, E. (2019). The puzzle of democratic divergence in the Arab World: Theory confronts experience in Egypt and Tunisia. Political Science Quarterly, 133(3), 435–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/polq.12803

- Benstead, L. (2015). Why do some Arab citizens see democracy as unsuitable for their country? Democratization, 22(7), 1183–1208. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.940041

- Berman, C., & Nugent, E. (2019). Regionalism in new democracies: The authoritarian origins of voter-party linkages. Political Research Quarterly, online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912919862363

- Bishara, D. (2020). Legacy trade unions as brokers of democratization? Lessons from Tunisia. Comparative Politics, 52(2), 173–195. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041520X15657305839654

- Bishara, D., & Grewal, S. (2021). Political not partisan: The Tunisian General Labor Union under democracy. Comparative Politics, online first. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041522X16240414667941

- Boubekeur, A. (2016). Islamists, secularists, and old regime elites in Tunisia: Bargained competition. Mediterranean Politics, 21(1), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2015.1081449

- Brooks, R. (2013). Abandoned at the palace: Why the Tunisian military defected from the Ben Ali regime in January 2011. Journal of Strategic Studies, 36(2), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2012.742011

- Brumberg, D., & Ben Salem, M. (2020). Tunisia’s endless transition? Journal of Democracy, 31(2), 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2020.0025

- Buehler, M., & Ayari, M. (2018) The autocrat’s advisors: Opening the black box of ruling coalitions in Tunisia’s authoritarian regime. Political Research Quarterly,71(2), 330–346. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1065912917735400

- Cappoccia, G. (2002). Anti-system parties: A conceptual reassessment. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 14(1), 9–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/095169280201400103

- Caraway, T., Crowley, S., & Cook, M. L. (2015). Introduction: Labor and authoritarian legacies. In T. L. Caraway, M. L. Cook, & S. Crowley (Eds.), Working through the past: Labor and authoritarian legacies in comparative perspective(pp. 1–24). Cornell University Press.

- Chomiak, L. (2019). Cracks in Tunisia’s democratic miracle. Middle East Report, 293/3(Fall/Winter), 20–23. https://merip.org/2019/12/cracks-in-tunisias-democratic-miracle/

- Chomiak, L., & Parks, R. P. (2020). Tunisia. In E. Lust (Ed.), The Middle East(pp. 661–695). CQ Press.

- Cook, S. A. (2007). Ruling but not governing: The military and political development in Egypt, Algeria, and Turkey. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Franklin, M. (2002). The dynamics of electoral participation. In L. Leduc, R. Niemi, & P. Norris (Eds.), Comparing democracies: Elections and voting in global perspective(pp. 148–168). Sage.

- Galston, W. A. (2018). The populist challenge to liberal democracy. Journal of Democracy, 29(2), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0020

- Gaub, F. (2017). Guardians of the Arab State: When militaries intervene in politics, from Iraq to Mauritania. Oxford University Press.

- Grewal, S. (2019a, September 16). Political outsiders sweep Tunisia’s presidential elections. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/09/16/political-outsiders-sweep-tunisias-presidential-elections/

- Grewal, S. (2019b). Winners and losers of Tunisia’s parliamentary elections. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/10/11/winners-and-losers-of-tunisias-parliamentary-elections/

- Grewal, S., & Hamid, S. (2020). The dark side of consensus in Tunisia: Lessons from 2015-2019. Foreign Policy at Brookings, No. 1. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-dark-side-of-consensus-in-tunisia-lessons-from-2015-2019/

- Grewal, S., & Monroe, S. (2019). Down and out: Founding elections and disillusionment with democracy in Egypt and Tunisia. Comparative Politics, 51(4), 497–539. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041519X15647434970027

- Günay, C., & Sommavilla, F. (2019). Tunisia’s democratization at risk. Mediterranean Politics, online first. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2019.1631980

- Gunther, R., Diamandouros, N. P., & Puhle, H.-J. (eds). (1995). The politics of democratic consolidation: Southern Europe in comparative perspective. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hartshorn, I. M. (2016). Tunisia’s labor union won the nobel peace price. But can it do its job? (POMEPS Studies, No. 18: Reflections Five Years after the Uprisings). http://pomeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/POMEPS_Studies_18_Reflections_Web.pdf

- Hartshorn, I. M. (2019). Labor politics in North Africa: After the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia. Cambridge University Press.

- Hassan, M., Lorch, J., & Ranko, A. (2019). Explaining divergent transformation paths in Tunisia and Egypt: The role of inter-elite trust. Mediterranean Politics, online first. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2019.1614819

- Hazbun, W. (2017). The politics of insecurity in the Arab World: A view from Beirut. PS: Political Science & Politics, 50(3), 656–659. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517000336

- Holmes, A. A., & Koehler, K. (2020). Myths of military defection in Egypt and Tunisia. Mediterranean Politics, 25(1), 45–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2018.1499216

- Hunter, W. (1997). Eroding military influence in Brazil: Politicians against soldiers. University of North Carolina Press.

- Hunter, W., & Vega, D. (2021). Populism and the military: Symbiosis and tension in Bolsonaro’s Brazil. Democratization, 1–23, online first. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1956466

- Ignazi, O. (1996). The intellectual basis of right-wing anti-partyism. European Journal of Political Research, 29(3), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1996.tb00653.x

- Jebnoun, N. (2014). In the shadow of power: Civil-military relations and the Tunisian popular uprising. The Journal of North African Studies, 19(3), 296–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2014.891821

- Jermanová, T. (2020). From mistrust to understanding: Inclusive constitution-making design and agreement in Tunisia. Political Research Quarterly, online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912920967106

- Jöst, P., & Vatthauer, J. P. (2020). Socioeconomic contention in post-2011 Egypt and Tunisia. In I. Weipert-Fenner & J. Wolff (Eds.), Socioeconomic protests in MENA and Latin America: Egypt and Tunisia in interregional comparison(pp. 71–103). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kenney, C. D. (1998). Outsider and anti-party politicians in power. Party Politics, 4(1), 57-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068898004001003

- Keren, M. (2000). Political perfectionism and the anti-system party. Party Politics, 6(1), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068800006001007

- Koehler, K., & Warkotsch, J. (2014). Tunisia between democratization and institutionalized uncertainty. In M. Hamas & K. al-Anani (Eds.), Elections and democratization in the Middle East. Elections, voting, technology(pp. 9–34). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Koehler, K. (2017). Political militaries in popular uprisings: A comparative perspective on the Arab Spring. International Political Science Review, 38(3), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512116639746

- Langohr, V. (2014). Labor movements and organizations. In M. Lynch (Ed.), The Arab uprisings explained: New contentious politics in the Middle East(pp. 180–200). Columbia University Press.

- Linz, J. J., & Stepan, A. (1996). Problems of democratic transition and consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and post-communist Europe. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Mainwaring, S., & Scully, T. (eds). (1995). Building democratic institutions: Party systems in Latin America. Stanford University Press.

- Meddeb, Y. (2018). Support for democracy dwindles in Tunisia amid negative perceptions of economic conditions (Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 323). http://afrobarometer.org/sites/default/files/publications/Dispatches/ab_r7_dispatchno232_support_for_democracy_dwindles_in_tunisia_1.pdf

- Merkel, W. (2004). Embedded and defective democracies. Democratization, 11(5), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340412331304598

- Morlino, L. (1998). Democracy between consolidation and crisis: Parties, groups, and citizens in Southern Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 542–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Norris, P. (2011). Democratic deficit: Critical citizens revisited. Cambridge University Press.

- Pachon, A. (2014). Loyalty and defection: Misunderstanding civil-military relations in Tunisia during the ‘Arab Spring’. Journal of Strategic Studies, 37(4), 508–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2013.847825

- Pappas, T. S. (2019). Populism and liberal democracy: A comparative and theoretical analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Pietsch, J., Miller, M., & Karp, J. (2014). Public support for democracy in transitional regimes. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 25(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2014.925904

- Poguntke, T. (1996). Anti-party sentiment—conceptual thoughts and empirical evidence: Explorations into a minefield. European Journal of Political Research, 29(3), 319–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1996.tb00655.x

- Przeworski, A. (1991). Democracy and the market: Political and economic reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Cambridge University Press.

- Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Schedler, A. (1996). Anti-political-establishment parties. Party Politics, 2(3), 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068896002003001

- Stepan, A. (1973). The new professionalism of internal warfare and military role expansion. In A. Stepan (Ed.), Authoritarian Brazil: Origins, policies, and future(pp. 47–65). Yale University Press.

- Torelli, S., Merone, F., & Cavatorta, F. (2012). Salafism in Tunisia: Challenges and opportunities for democratization. Middle East Policy Council, 19(4). https://mepc.org/salafism-tunisia-challenges-and-opportunities-democratization

- Vatthauer, J.-H., & Weipert-Fenner, I. (2017). The quest for social justice in Tunisia: Socioeconomic protest and political democratization post 2011. Peace Research Institute. https://www.hsfk.de/en/publications/publication-search/publication/the-quest-for-social-justice-in-tunisia-socioeconomic-protest-and-political-democratization-post-2/

- Wolf, A. (2017). Political Islam in Tunisia: The history of Ennahda. Oxford University Press.

- Yardimci-Geyikçi, Ş., & Tür, Ö. (2018). Rethinking the Tunisian miracle: A party politics view. Democratization, 25(5), 787–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2017.1422120

- Yousfi, H. (2018). Trade unions and Arab revolutions: The Tunisian case of UGTT. Routledge.

- Zemni, S. (2013). From socio-economic protest to national revolt: The labor origins of the Tunisian revolution. In N. Gana (Ed.), The making of the Tunisian revolution: Contexts, architects, prospects(pp. 127–146). Edinburgh University Press.

- Zemni, S. (2015). The extraordinary politics of the Tunisian revolution: The process of constitution making. Mediterranean Politics, 20(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2013.874108

- Zulianello, M. (2018). Anti-system parties revisited: Concept formation and guidelines for empirical research. Government and Opposition, 53(4), 653–681. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2017.12