ABSTRACT

Despite the low mobilization of citizenry, the lack of any strong electoral competition and consequently the expected re-election of the incumbent, the 2021 Portuguese Presidential elections gained particular interest for two main reasons. Firstly, this election took place in extraordinary circumstances amid the Covid-19 pandemic. At the time, Portugal was experiencing the world’s highest number of new cases and deaths per million. Secondly, this election was noted for the support obtained by the far-right candidate, unprecedented in national elections in Portugal. Thus, this article attempts to provide an overview of the main features of the presidential elections of 2021 in Portugal, namely the measures introduced to mitigate the threat of the pandemic and assure voters’ safety, the impact of the pandemic and the lockdown in the electoral campaign, the electoral results, and the rise of the radical right in Portugal and its implications.

Introduction

Despite the low mobilization of the citizenry and weak electoral competition that usually characterize Portuguese presidential elections, especially when the incumbent is running for a second term as in 2021, the most recent presidential elections in Portugal gained particular interest for two main reasons. First, unlike other countries that postponed elections amid the covid-19 pandemic (e.g., Spain, Italy), the Portuguese presidential election took place in particularly harsh pandemic conditions, namely less than two weeks after the start of a new lockdown and a fresh wave of the coronavirus that threatened to overwhelm hospitals. Second, this election aroused greater interest due to the radical right and populist candidate, André Ventura, leader of Chega (Enough)3, who came in third place with almost 12 per cent of the vote share. Never before had a radical right party obtained such a result in national elections in Portugal (Afonso, Citation2021). In a country once thought as immune to the radical right’s allure in the European and Mediterranean context (e.g., Mendes & Dennison, Citation2021), this election provides clear evidence of the rising support for Chega in Portugal – as a first (national) test of its resilience – and helps us to trace the party’s unexpected result in the general elections of 2022 by becoming the third-largest party in parliament.

This article attempts to provide an overview of the main features of the 2021 presidential elections by describing the particularly challenging context in which they took place, the electoral campaign (and how it was impacted by the pandemic), the electoral results, and by reflecting on the surprising result of the radical right. We rely on multiple secondary data, namely the official electoral results, polls, newspapers, Eurobarometer reports, statistics from the Portuguese Directorate General for Health (DGS) as well as data from candidates’ social media platforms retrieved from the FoxP2 platform.

Brief institutional framework: Semi-presidentialism in Portugal

Portugal underwent a democratic transition in 1974 and adopted a semi-presidential government system. After a constitutional amendment approved in 1982, which reduced presidential powers, the government system moved from ‘president-parliamentarism’ to a ‘premier-presidential system’ (Magalhães, Citation2007), where presidents are more than figureheads, but still lack considerable powers (Shugart and Carey, Citation1992).

Since these elections do not directly affect who governs, there is an ever-growing perception of presidential elections as second-order contests (Magalhães, Citation2007). This is evidenced by the usual low mobilization of citizenry and low competitiveness of these elections, especially when the incumbent is running for a second term as all incumbents have been comfortably re-elected over the years in Portugal (Jalali, Citation2012). These features might suggest that these elections are something akin to a ‘popularity contest’ (Magalhães, Citation2007). However, presidents preserve important legal prerogatives, such as veto powers on legislation and the power to dissolve parliament under certain conditions. Furthermore, depending on their personal presidential style, on whether they coexist with majority or minority governments or are from the same party as the prime-minister, presidents have used both their legal powers and soft power skills differently to influence policy outcomes.

Holding elections during a public health crisis: the pandemic context and mitigating measures

The Covid-19 pandemic has presented severe challenges to the management and scheduling of elections across the world (Vîrtosu, Citation2021). The Portuguese presidential elections on 24 January 2021 took place in particularly harsh pandemic conditions and therefore perfectly portrays most of those challenges. Following a dramatic surge in daily cases, hospitalizations and deaths after the Christmas celebrations, the country was plunged into a second nationwide lockdown (January 15). By election day, there had been 636 190 confirmed cases and 10,469 deaths.

In light of these circumstances, the leader of the main opposition party (Rui Rio) proposed postponing the election. While widely discussed in the media, the proposal received little backing from key political authorities. It was decided to go ahead with the elections and introduce measures to assure the safety of voters, such as early voting, early voting for voters in mandatory confinement, increasing the number of polling stations, and ‘the acquisition of sanitary equipment’.

Under the early voting measure, citizens could register to cast their vote ahead of election day. A small number of polling stations in major cities were allocated for this purpose on 17 January. A record number of 197 903 early votes were cast in these elections. Although the increase in early voting might be explained to some extent by the pandemic, the rules cannot be compared with those determining eligibility for early voting in previous elections. In addition, citizens in mandatory confinement could register up until 17 January to have their votes collected from their home by municipal teams between 19 and 20 of January. A total of 12,906 citizens registered for early voting. However, citizens who had been ordered to isolate at home after 15 January were not eligible under this measure and were therefore prevented from casting their vote. Newspapers reported that this loophole prevented around 135 884 citizens from casting their votes, a high figure when compared with the number of constituents who had indeed registered. Another measure to avoid large gatherings was the addition of extra polling stations in parishes with significantly more than 1000 registered voters. Finally, the government acquired 480,000 euros worth of Covid-19 support and personal protection material for election day.

Finally, it should be noted that the National Election Commission (CNE) launched a ‘Voting is safe’ campaign to encourage people to vote in the presidential elections in Portugal. This awareness campaign was launched online with videos of everyday activities demonstrating that ‘going to get a coffee is safe, going to vote is too’. This demonstrates the authorities’ concern about the impact of Covid-19 on turnout. Despite all the efforts and measures introduced, a poll conducted prior to election day reported that 57 per cent of Portuguese citizens were in favour of postponing the election, while 42 per cent said they did not intend to vote anyway.Footnote1

The electoral campaign

Campaigning in the midst of a pandemic crisis

The start of a new lockdown in the middle of the official electoral campaign plunged the political campaign into uncertainty and reshaped the traditional campaigning methods used by candidates, their budgets and planning activities, as well as the issues discussed.

The lockdown meant that more electoral activities had to take place online. Although parties’ political activities were excluded from the state of emergency restrictions, candidates chose to adapt their campaigns and reduce street contacts. Creative and alternative campaigning methods were used to reach out to voters. As in other countries holding elections during the pandemic , face-to-face campaigning (e.g., door-to-door campaigns; gatherings; rallies) was largely replaced by digital campaigning – using internet (e.g., webpages; advertising; search engine optimization); social media (e.g., Facebook; Twitter; WhatsApp; Snapchat; Instagram); mobile services (e.g., SMS); online rallies; and other political campaigning software. Therefore, both media and pundits described this as an ‘atypical’ campaign in which the extensive use of online campaign resulted in a lack of public mobilization around candidates. Moreover, there seemed to be increasing emphasis placed on debates between candidates on television and radio, but also on social media as the pandemic context restricted other in-person campaigning methods.

Although the incumbent, Marcelo Rebelo Sousa, excluded social media as a campaigning tool and made no use of the time he was entitled to on TV and radio, he enjoyed significant media coverage. After more than 10 years cultivating a public image as a TV commentator prior to becoming president, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa clearly benefited again from his media presence. This is particularly important as the Portuguese media enjoys one of the highest levels of trust in TV in Europe (68 per cent in October 2018 compared to EU average of 50 per cent — Standard Eurobarometer 90).Footnote2

The constraints and uncertainty of the pandemic context also affected the budgets for electoral campaigns. Overall, budgets were much lower than in the 2016 presidential campaign. Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, Marisa Matias and Tino de Rans had significantly lower budgets than in the previous presidential election. This can be explained in part by the digital tools used to support most campaign planning as they are less expensive than face-to-face campaigning. Nevertheless, campaign spending patterns over the years show that the combined budgets for presidential electoral campaigns have been in steady decline since their highest point in the 2006 presidential election (2006: €3,700,000; 2011: €2,120,000; 2016: €750,000; 2021: €450,000).

Holding the election during the pandemic also changed the policy agenda considerably. The public debate became centred on the public health crisis and its management by the government and the incumbent President. Inevitably, the National Health Service marked the campaign debate while other issues became less prominent. Like other electoral campaigns during the pandemic (see Vîrtosu, Citation2021), Covid-19 was highly politicized and used as a campaigning tool for all candidates. The overloading of the health services, the lack of investment in the National Health System in past years, the vaccination plan and the constant renewal of the state of emergency since the start of the pandemic were at the centre of the debate.

Furthermore, most of the debate was very personalized with candidates scrutinizing each other’s past and character traits. Contrary to the last presidential elections, most debates were highly polarized, with substantive political disagreement between the candidates, especially with André Ventura. In addition, a January poll conducted by ICS/ISCTE revealed that many voters (56 per cent) were following the campaign with ‘a lot’ or ‘some’ interest.Footnote3 Therefore, the importance of TV debates increased in the pandemic context due to the impossibility of using various traditional campaigning methods. This trend is also supported by TV audience figures: the three most watched debates in the 2021 electoral campaign gathered a larger audience than the most watched TV debates in the previous presidential campaign.Footnote4

The most exciting debates featured André Ventura. The first, between the incumbent, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa and Ventura, was broadcast live on (6 January) and watched by almost 2 million viewers. The focus was on the issues that divided the two right-wing candidates, such as the integration and representation of minority groups. The second, between Ventura and a left-wing candidate, Marisa Matias, was again broadcast live (7 January) and watched by 1.7 million viewers. This debate, like others with Ventura, was marked by accusations, insults and many interruptions. With every passing debate, political pundits increasingly recognized Ventura’s astute rhetorical skills.

Moving from traditional campaigning methods to digital tools

Due to a new lockdown, most electoral activities had to take place online during the electoral campaign. Face-to-face campaigning was largely replaced by digital campaigning, with most candidates other than Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa shifting the reaching out activities to social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter. In this ‘atypical’ pandemic scenario, social media became increasingly relevant as a channel through which candidates could directly engage in discussions with voters. Given the importance of social media in this particular campaign, we collected data from the multiple social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter and Instagram) used by all candidatures in January (during the official electoral campaign period) to depict (and compare) their usage and performance.

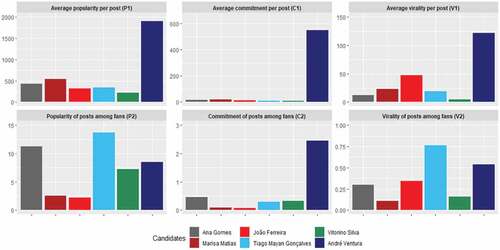

Following the metrics developed by Bonsón and Ratkai (Citation2013), the focus is placed specifically on three dimensions: popularity, commitment, and virality of candidates’ posts. Each dimension has two complementary measures: 1) an absolute average of likes, comments, and shares per post (P1, C1, and V1 respectively), and 2) a relative measure that weighs the data by the number of ‘followers’/friends for the page (P2, C2, and V2). The figures were multiplied by 1,000 for a better comparison as the original results were close to zero (Bonsón & Ratkai, Citation2013; Serra-Silva et al., Citation2018).

As shown in , the radical right candidate, André Ventura, has the most shared, discussed, and liked posts if we consider absolute numbers. This reflects Ventura’s reliance on social media to build and strengthen his support base as it is believed to offer a channel for the populist yearning to ‘represent the unrepresented’, providing a voice to a voiceless and unifying a group of divided people (Gerbaudo, Citation2018).

Figure 1. Candidates’ engagement on social media (1–22 January).

However, a different picture emerges when these absolute values are weighted by the number of ‘followers’/friends. Despite André Ventura’s noteworthy performance, Tiago Mayan Gonçalves, who is more viral and popular with his audience, takes the top ranking for the number of comments made by his followers. In other words, although André Ventura’s content resonates very well in social media, the content of Tiago Mayan, the right-wing liberal candidate, is the most engaging among his followers. This is particularly relevant as sharing is a low-limit but potentially very effective mass-centric form of party and candidate mobilization.

The electoral results

A comfortably re-election of the incumbent

On 24 January, a little over 4 million Portuguese went to the polls at the peak of the pandemic. Turnout hit a historic low of 39.2 per cent and was particularly poor in Northern and Central regions such as Bragança (33.3 per cent), Guarda (37.4 per cent) and Viseu (37.3 per cent), as well as in the autonomous region of Azores (36.1 per cent). The increase in the number of voters is largely due to the automatic voter registration of emigrants with a valid citizen’s card following a change in the legislation in 2018. This increase was expected to lead to a dramatic fall in turnout rates. Despite the historically low turnout, political pundits and analysts had expected it to be even lower even in the absence of the pandemic, foreseeing abstention of around 75 per cent pointsFootnote5.

Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa was comfortably re-elected at the first ballot with 60.7 per cent of the vote share. Although it was not the greatest electoral result in presidential elections, it was the first time a candidate had won in every Portuguese municipality. Just as in the last election, Marcelo’s ability to build a catch-all electoral coalition and blur ideological cleavages was crucial to garner popular support across the political spectrum (Fernandes and Jalali, Citation2017). Marcelo’s vote share was almost twice the electoral supportobtained by his supporting parties, the centre-right Social Democratic Party (PSD) and the Christian Social Democratic Centre (CDS-PP), in the last legislative elections (2019).

On examining all seven contestants, we find that Ana Gomes suffered a heavy defeat in this election, obtaining just 13 per cent of the vote share and failing to achieve the goal of forcing a second round. Nevertheless, she was victorious in the dispute for second place with André Ventura, who obtained almost 12 per cent of the vote share. The outcome of the dispute between these two candidates was the most anticipated result in a particularly uncompetitive election and unveiled the potential growth of Chega in Portugal after its establishment in mid-2019. Marisa Matias, supported by BE (Left-Bloc), also suffered a resounding defeat, obtaining around 300 000 fewer votes than in the last presidential election. As for the Communist candidate, João Ferreira obtained 4.3 per cent of the vote share, fewer votes than his predecessor, Edgar Silva, suggesting his inability to reach beyond the Communist faithful. Finally, minor candidates achieved around 3 per cent of the vote share: Tiago Mayan Gonçalves obtained more votes than his party in the 2019 legislative elections, already indicating the growing support for IL (Liberal Initiative) and later confirmed in the 2022 general elections; on the other hand, Vitorino Silva’s performance was slightly worse than in the last presidential election.

Presidential elections, a perfect scenario for the radical right?

The main candidate contesting Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa’s dominance on the right of the political spectrum was André Ventura, leader of Chega, a party considered in previous literature to be both populist and radical right (Afonso, Citation2021; Mendes & Dennison, Citation2021). Established in mid-2019, Chega rapidly secured one parliamentary seat in the October 2019 general election and has subsequently seen its popularity rise quickly.

Polling numbers reveal that André Ventura was close to disputing second place. As the difference narrowed between voting intentions for Ana Gomes, a former deputy in the European Parliament for the Socialist Party (PS) between 2004 and 2019, and André Ventura, the possibility emerged of Ventura becoming the main opposition figure in this election. In fact, he missed coming in second place by just one point and was also ahead of a number of candidates supported by established parties, as shown above. Despite a timid start in the 2019 parliamentary elections, ‘the presidential election of January 2021 was a breakthrough in the history of the radical right in Portugal’ (Afonso, Citation2021:2). Never before had a radical right party obtained such a high score in national elections in the country (Afonso, Citation2021). This achievement highlights the undeniable political weight of André Ventura and Chega in the Portuguese party system today. This was further confirmed later in the September 2021 local elections when the party achieved almost 5 per cent of the vote share and managed to elect 19 councilors across the country; the party built on this further in the 2022 snap general election when it obtained 7.2 per cent of the vote share and became the third-largest party in the Portuguese parliament.

These results suggest some signs of dissatisfaction with established parties. In a country usually thought to be ‘immune’ to the populist and radical right surge in the rest of Europe, the 2021 Presidential election unveiled for the first time the extent of support for the radical right in Portugal. Chega’s rise in popularity in its first (national) resilience test after entering parliament in 2019 confirms Mudde and Kaltwasser’s (Citation2017) assertion that no country is immune to populist, nativist and authoritarian appeals – it was only a matter of getting the most appropriate populist radical right party or political entrepreneur. André Ventura’s results show he seems to meet this requirement. Although the reasons for the radical right’s historic result in Portugal still remain unclear, the literature shows the importance of strong leadership, the capacity to avoid the stigma usually associated with radical right parties, the impact of media coverage and the nature of elections as possible explanatory factors. Although it is not our goal to advance any form of empirical test and assess the explanatory power of these features, we can add a few notes based on this particular election.

First, Ventura stood out for his strong leadership, rhetorical skills, and media savviness, which was clear during the debates in the electoral campaign. Second, in the past Ventura not only ran for local elections with the support of the main centre-right party (PSD), but also cultivated a public image as a well-known football TV commentator; these factors combined might have helped to overcome the above-mentioned stigma. Finally, given the expected re-election of the popular incumbent President among voters and the lack of competition and mobilization in this electionFootnote6, some voters might have felt free to use their votes to opt for candidates that are closer to their preferences or to signal their protest and dissatisfaction with political elites – literature has shown that this generally benefits far right parties.

Conclusion

The aim of this electoral profile was to describe the 2021 presidential elections, setting them against the backdrop of the current pandemic and the recent rise of a populist and radical right party in Portugal. The presidential election took place on 24 January 2021 during a nationwide lockdown, a difficult and challenging scenario. Additionally, these presidential elections provided the radical right with the perfect setting to increase and establish its popular support: not only were the candidates’ personal characteristics more relevant due to the nature of this election, with André Ventura’s traits favouring his political aspirations, but the left-leaning electorate was also split between three candidates, enabling André Ventura to dispute second place; moreover, the second-order nature of this particular election might have left space for expressive (i.e., sending a costless signal of voters’ level of dissatisfaction) and sincere voting (i.e., opting for candidates closer to their preferences).

Considering the initial questions raised in the introduction, two main conclusions can be drawn. First, despite having the highest number of new Covid-19 cases and deaths per million in the world at the time of election, the Portuguese authorities were apparently able to ensure the pandemic would not affect overall participation. Second, the electoral campaign was profoundly affected by the pandemic: debates were strongly focused on Covid-19 management and an increasing proportion of campaigning activity moved online. While the pandemic undoubtedly constrained campaigning activities, not all candidates were successful in moving from traditional campaigning methods to digital campaigning. The most successful on this count was André Ventura, since his Facebook posts were the most shared, discussed, and liked. This might be explained by the fact that Ventura had already been relying heavily on social media even before this election. Third, this presidential election is a confirmation of the end of ‘Portuguese exceptionalism’ due to the absence of a successful populist radical right party given that André Ventura came in third place with 11.9 per cent of the vote share and almost half a million votes. This represents a major increase in popular support vis-à-vis the previous legislative elections when Chega obtained 67,825 votes. Nevertheless, in the January 2022 snap general elections, the party managed to garner 7 per cent of the vote share, fewer votes than in the 2021 Presidential election but still keeping much of its electoral support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. ICS/ISCTE, September 2019 survey: https://sondagens-ics-ul.iscte-iul.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Sondagem-ICS_ISCTE_Setembro2019_parte2.pdf

2. Standard Eurobarometer 90. The data are available at: https://ec.europa.eu/portugal/sites/default/files/eb90-portugal-outono2018_pt.pdf

3. ICS/ISCTE, January 2021 survey: https://sondagens-ics-ul.iscte-iul.pt/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Relatório-presidenciais-janeiro-2021.pdf

4. ‘Em tempo de pandemia, portugueses mais interessados nos debates presidenciais’, Dinheiro Vivo, 11 January 2021, available online at: https://www.dinheirovivo.pt/empresas/em-tempo-de-pandemia-portugueses-mais-interessados-nos-debates-presidenciais-13216414.html

5. ‘Abstenção nas presidenciais deveria chegar aos 75 per cent, mesmo sem pandemia’, Público, 12 January 2021, available online at:https://www.publico.pt/2021/01/12/politica/noticia/abstencao-presidenciais-iria-chegar-75-pandemia-1945909.

6. The Socialist Party (PS) chose not to have an official candidate, thus contributing to the increasing perception of these elections as second-order.

References

- Afonso, A. (2021). Correlates of aggregate support for the radical right in Portugal. Research & Politics, 8(3), 205316802110294. https://doi.org/10.1177/20531680211029416

- Bonsón, E. and Ratkai, M. (2013). A set of metrics to assess stakeholder engagement and social legitimacy on a corporate Facebook page. Online Information Review, 37(5), 787–803. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-03-2012-0054

- Fernandes, J. M., & Jalali, C. (2017). A Resurgent Presidency? Portuguese Semi-Presidentialism and the 2016 Elections. South European Society & Politics, 22(1), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1198094

- Gerbaudo, P. (2018). Social media and populism: An elective affinity? Media, Culture & Society, 40(5), 745–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718772192

- Jalali, C. (2012). The 2011 Portuguese presidential elections: Incumbency advantage in semi-presidentialism? South European Society & Politics, 17(2), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2011.624688

- Magalhães, P. (2007). What are (semi)presidential elections about? A case study of the Portuguese 2006 elections. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 17(3), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457280701617094

- Mendes, M. S., and Dennison, J. (2021). Explaining the emergence of the radical right in Spain and Portugal: Salience, stigma and supply. West European Politics, 44(4), 752–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1777504

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780190234874.001.0001

- Serra-Silva, S., Carvalho, D. D., & Fazendeiro, J. (2018). Party-citizen online challenges: Portuguese parties’ Facebook usage and audience engagement. In M. C. Lobo, F. C. Silva, & J. P. Zúquete (Eds.), Changing societies: legacies and challenges. Citizenship in Crisis (Vol. II, pp. 185–214). Lisbon: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. https://doi.org/10.31447/ics9789726715047.08

- Shugart, & Carey. (1992). Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139173988

- Vîrtosu, I. (2021). How COVID-19 changed ‘the anatomy’ of political campaigning. Central and Eastern European E|dem and E|gov Days 2021, 341, 351–369. https://doi.org/10.24989/ocg.v341.26