ABSTRACT

The quotation in the title from a college leader is a stark reflection of the experience of the Further Education (FE) Sector during the COVID pandemic (2020–21). Traditionally regarded as a poor relation of the English education system, evidence from Sector sources suggest that the five COVID harms identified through a scoping review of the latest research closely mirror the main social and educational features of English general FE colleges. The pandemic has led to longer-term harms on vocational learning, with major disruptions to college-based courses and to apprenticeships, a stagnation situation captured in the metaphor ‘educational long-COVID’. The analysis conceptualises the impact of the pandemic on FE provision and learners as leading to a ‘COVID learning and skills equilibrium’; whereas effective mitigations are conceptualised through the idea of ‘COVID recovery ecosystems’. Rapid review evidence suggests that the most effective way of addressing system-wide disruption is the development of integrated, strategic actions at local and regional levels to address vocational learning losses, facilitate greater entry-to-employment and to create more job opportunities for young people. Without these longer-term measures it is likely that the negative effects of the pandemic on the FE Sector could become further entrenched.

Social and educational divisions in a uniquely vulnerable sector

The last 2 years of the COVID pandemic has laid bare existing economic and social divisions in terms of the role of workplace inequalities and social deprivation (Collinson Citation2020; Elgar, Stefaniak, and Wohl Citation2020), fuelling longer-term structural inequalities (The British Academy Citation2021). This alerted us to a possible relationship between pre-existing divisions and the social and educational character of the Further Education (FE) Sector that includes full- and part-time learners, young people and adults, licence to practice courses, learners on ESOL (English to Speakers of Other Languages) programmes and independent living skills for learners with additional learning needs (Orr Citation2020). The Sector is also more likely than other parts of education to cater for the ‘forgotten 50 per cent’ of learners not progressing to higher education, many of whom come from more vulnerable and deprived sections of the population (Birdwell, Grist, and Margo Citation2011) and communities that have experienced high infection rates (Elgar, Stefaniak, and Wohl Citation2020). In the words of the Association of Colleges (AoC) (Citation2021a, 1), further education institutions have been ‘uniquely vulnerable to external shocks’. The Sector is also financially stressed, with the Institute of Fiscal Studies (Citation2020) calculating that funding per student in further education and sixth-form colleges in England fell by 12% in real terms between 2010–11 and 2019–20 and support for adult learning and apprenticeships declining by 35%.

Research approach – Rapid Review Plus

A combinational research strategy

The complex nature of the pandemic and its effects over time, the unfolding impacts of counter measures and the specificities of the Sector necessitated a ‘combinational’ research strategy. The research, originally commissioned by the DfE and SAGE that underpins this article, was intended to be based on rapid review methodology.Footnote1 At the end of 2020, these members of the policy community wanted to know what potential harms could be identified in a research literature that was relevant to the UK context, and what systematic review evidence might provide concerning mitigations of the COVID pandemic in different fields of education. However, the relatively under-researched nature of Further Education (Solvason and Elliott Citation2013; Exley Citation2021), meant that there was likely to be less relevant systematic review evidence available in further education compared with other education sectors. This paucity was compounded by the novelty of the pandemic. It was decided, therefore, to supplement systematic review evidence with targeted and focused primary research from a diverse range of FE sector stakeholders and experts in the field, a research approach that might be understood as ‘Rapid Review +’.

The rapid review element of the research reflected the constraints in delivering a systematic review in a short space of time. As rapid reviews are delivered at pace, decisions had to be made on how to narrow the focus of the review, by population or to the most comparable contexts, or by focusing only on those sources of literature where the most on-topic studies are likely to be found and only on studies that were more likely to directly answer questions on effectiveness. We took a two-step approach in evaluating the rapid evidence review for inclusion.

The first was to identify the harms experienced by students and staff of further education and sixth form colleges. We searched academic literature in the largest social science bibliographic databases available – ProQuest Central, as well as Scopus, Google Scholar and Google using keywords for students of FE colleges, FE education and Covid 19. Among the 86 studies identified in our search, we found 25 research studies that met our inclusion criteria of being in the UK and on the impacts of COVID 19 on further education. The second step examined the wider, systematic review evidence on mitigations. To be included, a study would have to be a systematic review of interventions intended to mitigate the harms related to the FE Sector and possess the key methodological features including an explicit search, listed search sources, inclusion criteria, and quality assessment. The largest social science bibliographic databases available were searched iteratively, with keywords for each of the harms identified through the scoping review phase in ProQuest Central, Scopus, as well as Google Scholar and Google as well as repositories of systematic reviews such as The International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO) Living Map (Shemilt et al. Citation2021) and the Cochrane and Campbell collaboration of systematic reviews.

The bibliographic database searches were supplemented by so-called grey literature including documentation from the Westminster Government and the Welsh Government and Sector representative associations including real-time data from the ONS (Briggs, Freeman, and Pereira Citation2021). Relevant documentation was reviewed from 30 state and civil society organisations in relation to both harms and mitigations. In addition, a total of 11 FE sector actors were interviewed with the anticipation that these conversations could provide an insight into factors and strategies not yet reported in documentation. The sample comprised five college leaders, two senior executives of vocational assessment authorities and four managers of sectoral support organisations. College leaders were also reinterviewed on December 2021 and January 2022 to provide an up-to-date picture. We also included a summary of discussion of international stakeholders from an Italian-led T20 COVID seminar (Castelli et al. Citation2021) to offer further insights in relation to potential short- and long-term harms. We conducted a thematic synthesis against the research literature and the interviews with stakeholders combined for the harms identified and the responses and implications found in the systematic review evidence for mitigations.

A staged approach

This combinational research approach was conducted through six stages.

Stage 1. Appreciating the specificities of the FE Sector – in the first scoping phase of research (early April 2021) the key features of further education providers, its learners, teachers, institutions and its regulatory mechanisms were reviewed in order to develop a conceptual grasp of the specific educational, social and economic contexts in order to inform the search questions and the research approach.

Stage 2. Developing key research questions – two clusters of research questions were developed in relation to COVID harms and mitigations. The first cluster focused on the nature and extent of COVID harms reported, their potential short- and long-term effects and the degree to which they might be related to the fundamental features of the Sector. The second cluster is related to evidence available from systematic reviews and evidence of counter measures being reported by the Sector.

Stage 3. Identifying key COVID Impact Themes – this early contextual work led to the identification of five COVID Impact Themes.

Vocational disruption – economic participation, apprenticeships and impacts on vocational courses.

Problematic transitions and access to higher education.

Growing inequalities, disadvantaged young people and NEETs.

Deterioration in the mental health and well-being of young people.

A responsive but ‘stressed’ FE Sector.

Stage 4. Deciding how to combine rapid review methods with other forms of data gathering – evidence of COVID harms came mainly from the Sector, whereas the evidence of mitigations, in the main, came from systematic reviews.

Stage 5. Updating findings in late 2021 – given that the original research took place in early 2021, the evolution of the pandemic and health measures such as the vaccination programme suggested benefits of returning to the research field. Evidence for the updating was provided by follow-up interviews with five key sector actors located in different parts of England. These new data are reported in a discrete section – ‘Sector-based evidence at the end of 2021’, together with the new findings from key reports not included in the original research.

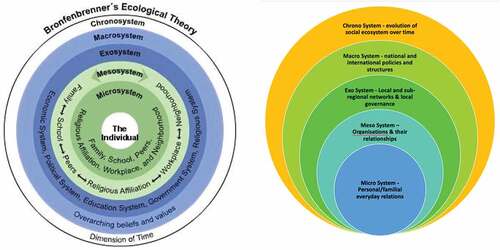

Stage 6. Analysis – the application of spatial and comparative conceptual frameworks – understanding the complex intersectional and evolving nature of the pandemic, together with the spatial and social complexities of the FE Sector, has led to a conceptual framework comprising multi-layered spatial-social scalars that interact and evolve over time. illustrates Bronfenbrenner’s original psycho-social ecological model (Citation1979), which includes the additional chronosystem (a) (Bronfenbrenner and Ceci Citation1994), together with its social and spatial adaptation applied to the world of TVET (b) (Hodgson and Spours Citation2018; Spours Citation2021).

Figure 1. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (Citation1979, Citation1994) and its social and spatial adaptation (revised Spours Citation2021).

In the social-spatial adaptation, as in Bronfenbrenner’s original model, each of the levels are in dynamic interaction. Individual, familial, social and educational differences (the micro-system) can be affected by wider scalars; for example, the institutions being attended (the meso-system); with the localities and sub-regions (the exo-system) being shaped by wider economic, political and social factors over time (macro and chrono systems). In terms of analysing the spatial dynamics of the pandemic, the conceptual framework has been used in two ways. First, to analyse the whole system effect of the pandemic on further education with the possibility that personal and familial characteristics in the micro-system might be becoming ‘embedded’ in the wider scalars, suggesting the emergence of a pandemic informed syndrome of harms in the form of a ‘COVID learning and skills equilibrium’.Footnote2 Second, using the same whole-system analysis to analyse evidence on multi-agency and strategic approaches to pandemic mitigations through the concept of ‘COVID recovery ecosystems’.

COVID harms and the FE Sector

Introduction

This section of the article reports COVID harms and mitigations separately and subsequently compares the relationship between them. The COVID Impact Themes identified in the early stages of research, reflecting the fundamental features of the FE Sector, could be viewed mainly as ‘indirect harms’ resulting from the effects of successive ‘lockdowns’ on local economies, workplaces and training opportunities.

Covid Harms 1. Vocational disruption

The pandemic and the necessary countermeasures have had a significant impact on student learning, particularly in terms of the different aspects of vocational learning, both in the UK and internationally (ILO and World Bank, Citation2021).

Decline in economic participation and apprenticeships – a rapid decline in economic participation of young people was reported by ONS data (Citation2021a, Citation2021b) with those under the age of 35 accounting for 80% of jobs lost. Apprenticeship participation has been declining since 2017 due to the impact of the Apprenticeship Levy (Seetec Outsource Citation2021). The pandemic has accelerated this trend, with Apprenticeship starts in the UK falling by 46 percentage points in 2020, compared with 2019. The worst affected sectors were health and social care, business management and hospitality (McCulloch Citation2021).

Impacts on college vocational learning – there have been noticeable reversals for those taking vocational courses with declines most marked for those studying at the lower levels and for adults. The Association of Colleges (Citation2021a) analysis of ‘college performance benchmarks’, based on MiDAS R14 ILR and 223 ILR college returns, reported a decline in performance of Functional Skills at Entry Level & Level 1 in 2019/20 compared with 2018/19; pass rates down by up to 5% in a range of vocational courses; declines in ESOL (5.7%) and Basic Maths and English (8.4%).

The move to online learning and its implications – the Education Endowment Foundation research (Francis Citation2021) concerning the impact of school closures and the digital divide on disadvantaged young people found that, as of the end of 2020, what is termed learning loss, learning gaps or learning disruption meant that learners were about 2 months behind what would be normally expected at particular stages. However, the gaps were much greater for socially disadvantaged learners. Views coming from both the Sector and T20 discussions (Castelli et al. Citation2021) suggest that vulnerable learners have been particularly disadvantaged by the absence of close teacher support together with the structure and personal discipline that comes from regular institutional attendance.

COVID harms 2. Problematical transitions including access to higher education

Research pointing to the differential impact of the pandemic and academic and vocational learning in terms of disruption reveals a clear pattern – access to higher education study has increased, while participation in vocational learning has fallen. What is not yet known is whether this will prove to be temporary or whether the vocational route will, as a result, shrink.

On the academic track, teacher-based assessment in 2020 increased the proportion of the cohort attaining the higher grades at both GCSE and A Levels. The proportion of candidates awarded A* or A rose 12.9pp, from 25.2% in 2019 to 38.1% in 2020 (Ofqual, Citation2021). The immediate impact of increases in grade attainments at A Level has been a growth in applications to university. Data from the University and College Admissions Service (UCAS) suggest that a total of 508,090 applicants accepted places at universities across the UK in 2020, an increase of 3.5% compared with 2019 (Financial Times Citation2020). As we have seen in the previous section, rising attainment in the academic track can be contrasted to falling rates in vocational learning. Moreover, pre-pandemic research on transitions within upper secondary education pointed to existing difficulties of progression for middle and lower attainers (Rogers and Spours Citation2020) and the fear is that these groups may face further disadvantage. These concerns have prompted Nuffield research into transition difficulties at post-16 for particular groups of learners; for example, those deemed to have ‘failed’ at GCSE (Raffo and Thompson Citation2021). The overall effects of these differential dynamics could result in the deepening of class gaps in terms of transitioning within and beyond the upper secondary phase.

COVID harms 3. Inequalities, disadvantaged young people and NEETs

Young people Not involved in Education, Employment or Training (NEETs) – ONS data (Citation2021b) reported that those known as NEETs rose by 39,000 to 797,000 in the final 3 months of 2020 and that an estimated 44.3% of NEETs were looking for, and available for, work and therefore classified as unemployed. The Resolution Foundation, the Institute for Employment Studies and the Learning and Work institute have predicted there will be at least 600,000 more unemployed young people, with a further 500,000 expected to become NEET over the next 18 months (Youth Employment UK, Citation2021). Recent rises in the number of NEETs appear to have reversed the historical downward trajectory of NEET numbers over the past decade.

Regional, social and racial inequalities – in terms of youth unemployment, 42% of black people aged 16–24 were unemployed compared to an unemployment rate among white workers of the same age of 12% (ONS, Citation2021a). Moreover, area-based research showed that the pandemic has been exacerbating geographical inequality in England, with London boroughs and the most deprived local authorities of the country experiencing the biggest rise in Universal Credit claimants (Sarygulov Citation2021). The socially differential impact of the pandemic has been confirmed by a COVID-19 Social Study surveying 70,000 adults in the UK (Fancourt and Bradbury Citation2021). It found that minoritised groups, those from lower socio-economic positions and young people, struggling much more than those with greater social privilege.

A diverse range of vulnerable learners in the FE Sector – interviews with leading Sector figures highlighted the broad range of vulnerable groups affected by risk factors such as poverty, ethnicity, family breakdown, ill-health, precarious work situations and being on a vocational study course. There were also reports of a significant number of students experiencing various forms of exclusion, whether this be access to wi-fi, suitable computers or a quiet space in which to study. College leaders also remarked about a loss of study habit and discipline, a loss of ‘agency’ and growing alienation. Concerns about growing inequalities linked to reduced access to resources were captured by one college leader who referred to a ‘precariat’ with stalled social mobility.

COVID harms 4. The mental health and well-being of young people

There has been consistent evidence, both from review research evidence and reporting by institutions, of the negative impact of the pandemic on mental well-being – those young people 16–24 reporting a deterioration in their mental state who did not previously have a confirmed mental health condition. There is also evidence prior to the pandemic that depression and anxiety is greater among NEETs (Feng et al. Citation2017). Of particular interest in relation to the theme of vocational disruption was the finding of young peoples’ concern about their ‘futures’, a finding confirmed by a Welsh Government survey of learners aged 16 or older (Mylona and Jenkins Citation2020).

COVID harms 5. A ‘stressed’ FE Sector

Over the past decade, further education and sixth form colleges have lost out financially compared with schools (Farquaharson, Britton, and Sibieta Citation2019; IFS Citation2020) and at the beginning of the pandemic, this pattern has persisted thus further entrenching sector disparities.

Despite the Government stating that they think the FE sector has an important role to play in ‘building back better’ and announcing £1.5 billion in capital funding to be invested in college buildings and facilities (PM’s Office, Citation2020), colleges have been finding it difficult to attract appropriately skilled staff domestically because of higher incomes in skilled employment and from overseas because of the income threshold for immigrants (Parrett Citation2021). In response, teachers in FE have been working longer hours, worsening the situation of burnout prior to the pandemic (Rasheed Karim Citation2020).

Mitigation approaches – what the evidence says

In relation to mitigations, evidence has been drawn from relevant systematic reviews and Sector-related proposals.

Theme 1. Vocational disruption

Systematic review evidence

Systematic review evidence was selected concerning recovery from forms of ‘vocational disruption’ in fields and time-periods beyond the Sector in 2020–21. We found a total of 11 relevant systematic reviews in this topic area. Evidence of successful interventions included the following.

Apprenticeships improve skill levels and have a positive effect on participants’ subsequent employment (What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth Citation2015).

Individual placement with additional support showed improved vocational outcomes with particularly beneficial effects for vulnerable groups (Vetsch et al. Citation2018).

Literature on vocational rehabilitation highlighted the importance of early intervention (Waddell, Burton, and Kendall Citation2008).

Intensive multi-component interventions effectively decrease unemployment among NEETs and other vulnerable groups (South Australia Centre for Economic Studies Citation2008; Mawn et al. Citation2017).

Evidence from government schemes, the FE Sector and wider stakeholders

The Government provided support to employers, through its ‘Kickstart Scheme’ that offered a six-month work placement to 18-to-24 year-olds making a claim to Universal Credit (DWP Citation2021). However, recent data has suggested that fewer than 500 places have been found in the North-East for a programme that was intended to provide 250,000 places nationally (Savage Citation2021), with reported hurdles affecting the participation of SMEs (Ruzicka Citation2021).

Awarding bodies and assessment regulatory agencies have focused on flexibility measures for 2021, new flexibility arrangements for learners to catch up, particularly in relation to LTP courses and return-to-work and various forms of work-based and technical qualification assessment (City and Guilds Citation2020). In addition, a range of actions have been suggested in response to the pandemic and imposed counter measures.

Expanding the use range of the apprenticeship levy (Redrow Citation2021).

Improving co-ordination of government funding streams at the local level with a focus on developing the green economy with young people at the centre (e.g. Quilter-Pinner, Webster, and Parkes Citation2020; LGA Citation2020).

The introduction of a Youth Guarantee or Opportunity Guarantee of a job, Apprenticeship or training offer for all young people (e.g. Evans and Clayton Citation2021). This is now policy in Scotland and Wales.

Providing targeted additional support for young people with additional needs (The All-Party Parliamentary Group for Youth Employment Citation2021).

Theme 2. Problematical transitions and access to higher education

Systematic review evidence

Evidence from systematic reviews point to the benefits of integrated and aligned programmes for young people that emerge as personalised packages of skills, financial, emotional and practical support (e.g. Hagell et al. Citation2019; Newton et al. Citation2020). In addition, international studies highlight the role of effective career education and guidance in relation to a changing labour market (Mann, Denis, and Percy Citation2020).

Evidence from the FE Sector and wider stakeholders

Beyond measures to help learners catch up, there have been a range of calls for a longer-term system reform – improving careers education, focusing greater resources on disadvantaged learners (Social Mobility Commission Citation2021), creating a more flexible and inclusive qualifications system and providing more learning opportunities outside that of formal schooling such as summer schools. Wider research literatures, once again, point to the potential of local collaborations combined with national strategic leadership.

Theme 3. Inequalities, disadvantaged young people and NEETs

We found no systematic review evidence on mitigating the increased educational inequalities directly relevant to the FE Sector. However, there were a number of sources reviewing studies on overcoming inequalities in wider society including evidence of a range of structural, individual and practice-level factors that can enable families to escape from persistent poverty; and practices focused on individual vulnerable learners including accurate identification, effective engagement, effective assessment and profiling, a trusted, consistent advisor and delivery of personalised support packages (Newton et al. Citation2020). In addition, a range of research projects on the issue of widening inequalities during the pandemic were identified. These included the drivers of socio-economic differences in post-16 course choices and their likely social mobility consequences (Social Mobility Commission Citation2021); investigation into ethnic disparities in employment, the criminal justice system, healthcare and education and the benefit of a new ‘Opportunity Guarantee’ for young people in England (Quilter-Pinner, Webster, and Parkes Citation2020).

Theme 4. The mental health and well-being of young people

Reviews concerned with mental health in relation to transitions to working life have consistently suggested benefits of comprehensive multi-agency ‘recovery frameworks’ that comprise different interventions – collaborative strategies covering training, work practices, therapeutic support; creating appropriate work environments, with active involvement of young people based on local and network collaboration (e.g. Fazel, Citation2014; Hart et al. Citation2020).

Within the Sector, the AoC noted that colleges have significantly increased resources being allocated to improving student and staff mental health and well-being during the pandemic and have recommended that FE providers go further to develop a ‘social prescribing model’ with the integration of a range of support activities.

Theme 5. A ‘stressed’ FE Sector

Systematic review evidence is very limited given the specificities of the FE Sector in the UK.

However, evidence coming from the Sector is contested. Throughout the pandemic, colleges have been supported by a range of government agencies including operational guidance documents (DfE Citation2021) and catch-up funding of £96 millions for colleges, although in England colleges were initially left out of the catch-up plan. Support for the Sector has also come from awarding bodies to help those learners who have had their studies delayed. However, the AoC has proposed a recovery plan comprising fair funding of practical courses targeted support for those most disadvantaged through 16–19 student premium and provision of extra-curricular activities such as sport, drama, music and volunteering to support learner progression (2021b).

Sector-based evidence 2021/early 2022

At the end of 2021 and into early 2022 we returned to five college leaders to ask them about the continued impact of the pandemic as the COVID Omicron variant took hold. The emerging picture was one of the persistence and evolution of Covid harms reported in earlier research.

The second lockdown has more of an unseen impact - less resilience, less proficiency, less practical learning which can’t be done on-line. Behavioural issues will continue to emerge over time, creating a lost generation. There has been a loss of part-time jobs, enhanced digital poverty, deferred progression, hardship and destitution, loss of practical skills, loss of community and diminished student experience.

This insightful quote from a college leader summarised the combined sense of loss that potentially impacts all learners and, in particular, the most vulnerable. It is worth remembering that many young people elect to come to FE colleges for practical learning and close support and it has been these experiences, despite the best efforts of college staff, that the pandemic has reduced. As will be seen, the reduced FE experience has been the result of the continued effects of several inter-related factors.

Vocational disruption

While some reported that the backlog in licence to practice (LTP) provision was largely resolved by October, these work-based courses were experiencing a knock-on legacy of learning and assessment disruption in 2020–21 with major concerns about delays in internal progression and endpoint assessment, depriving students of income and employers of skills. One college reported that of 800 apprentices, 400 were still being delayed. The catching-up process in other forms of vocational learning had also come at a cost. Vocational assessment was being organised back to back and deemed to be far too rushed. As a result, students had insufficient practice to digest the required competences and some did not have the stamina to match the necessary pace. Moreover, colleges were running out of resources to progress students through. The situation regarding work placements was reported as variable. Some colleges noted that the situation was almost back to normal, but with difficulties in particular areas such as digital skills because of homeworking thus restricting access to the workplace.

Learning, assessment and participation

The differential effect of the pandemic on academic and vocational learning continued to evolve. As a result of teacher assessed grades, colleges were seeing a significant increase in applications to high tariff higher education, but vocational students continued to struggle and were much further behind than expected. Where a qualification is based upon the demonstration of competence, it is not possible to dilute the assessment regime, thus causing institutional strain arising from a backlog of assessments. Increases in behavioural issues were also reported with signs of an inability to concentrate and an unwillingness to take on complex structures or rules. Face masks, for example, were proving hard to enforce. The sense of challenge reported early in 2021 was turning to fatigue.

Several colleges noted drops in student numbers, with one college leader remarking that ‘a whole chunk of the cohort had wandered off’. While there was insufficient strong data at the time of writing to explain this, hypotheses were that students got better (inflated) grades and so chose to stay at school; some had been moving into an expanded casualised labour market and more were staying at home and going NEET.

Inequalities

Earlier in our research we speculated that the social and demographic features of the Sector could result in deepening social and educational inequalities. Some two years into the pandemic, college leaders reported that inequities emerging at school (access to study space, resources, parental support) were flowing into FE and were particularly apparent in learners taking maths and English. Lecturers were being faced with a great variety of disruption of previous learning and socialisation (some have experienced exams and others have not), so there was little uniformity from which to plan future learning. Moreover, there remained a big divide between students in relation to access to suitable computers, wi-fi and a hierarchy at home over accessibility to space and privacy. One college leader referred to this as ‘accessibility poverty’.

Staffing and the FE Sector

All respondents reported staffing difficulties, with one remarking that bricklayers could now earn £100k a year, and with this being replicated in other skilled trades, who would want to teach for £35k a year? Moreover, this year’s budget was viewed as ‘a kick in the teeth’ with colleges unable to contemplate decent salaries. Staffing shortfalls in key areas were also worsened by the effects of the Omicron variant on sickness rates. Despite all of this, most of those interviewed considered that staff morale had been maintained, although many were exhausted with no end to the crisis in sight.

From a COVID learning and skills equilibrium to COVID recovery ecosystems?

In this analytical section, we apply the adaptive social ecosystem model to discuss evidence regarding the systemic impacts of COVID harms and potential system-wide mitigations. An earlier part of the article introduced the idea of a ‘COVID driven learning and skills equilibrium’ in which a series of factors across ecosystem scalars interact to frustrate the development of learning and skills in FE. In terms of the social ecological model, the learning and skills equilibrium results from harms that spill out across ever-widening geo-social scalars (e.g. individual and familial vulnerability; micro-level – becoming compounded at the institutional level; learning and skills providers experiencing multiple stresses – meso-level; communities, localities and sub-regions being affected by economic and social disruption – exo-level – and impacts on important parts of the national macro-level such as the qualification system) – all of which continue to evolve over time.

The chrono dimension – the emergence of ‘educational long-COVID’?

Like the COVID virus itself and its constant mutations, the effects of the pandemic on the further education sector appear to be persisting and evolving: a situation confirmed in the follow-up interviews that could be captured in the metaphor of ‘educational long-COVID’. The longer-term effects on different communities in their wider contexts have been highlighted in a British Academy report The COVID Decade (2021) which used an analytical approach similar to the social ecosystem conceptual framework employed in this article.

Throughout the process of collating and assessing the evidence, the dimensions of place (physical and social context, locality), scale (individual, community, regional, national) and time (past, present, future; short-, medium- and longer-term) played a significant role in assessing the nature of the societal impacts and how they might play out, altering their long-term effects (2021, 6).

Ongoing research is required, however, as to the precise relationship between learning disruption and behavioural issues that may be remediated and longer-term negative effects on learner aspirations, educational engagement and progression (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD Citation2020). Possible longer-term patterns of harm can be understood through a brief analysis of the interaction of different scalars (from micro to macro) in the COVID learning and skills equilibrium.

Micro-level individual and familial vulnerabilities

Catering for more economically and socially vulnerable learners is a notable feature of FE colleges (Hyland and Merrill Citation2010). Evidence concerning COVID harms experienced by socially vulnerable families and their children links multiple factors, including the lack of underlying economic resilience prior to the pandemic; the impact of overcrowded housing and dangerous workplaces on levels of infection in the early stages of the pandemic; and the disproportionate economic impacts on the livelihoods of young workers.

The FE institutional meso-level has also proved to be vulnerable

Sector-based research has also pointed to the vulnerabilities of FE colleges – including continued funding stresses (NOA Citation2020) and shocks from workplaces that have disrupted work-based learning and attainment. Further education colleges have also seen a decline in full-time participation during the first year of the pandemic (DFE Citation2021), added to which have been reports from college of chronic staff shortages in key skill sectors. The accumulation of these challenges has led FE leaders to speculate that it will take a decade to fully recover. Despite concerted efforts to support their learners, it remains the case that individual and familial harms and vulnerabilities at the micro-level have, in many cases, have been compounded at the institutional meso-level. Another issue that requires ongoing research, is how far these COVID-related harms might be subjected to further shocks coming both from the persistence of the pandemic and the impact of wider economic problems.

The variable impact of COVID on the local and sub-regional economic exo-levels

The negative impacts of the pandemic have not been confined to the individual micro and institutional meso levels; they have also occurred on the wider economic, local and sub-regional levels. British Academy evidence (2021) pointed to nine areas of impact including widening geographic, structural and educational/skills inequalities located in the local and sub-regional exo-systems. Research also suggests a highly variable picture of financial health with a significant minority of SMEs deeply in debt, particularly those companies that are consumer facing (Bank of England Citation2021). The picture in the Bank of England study, however, was not entirely negative, with findings concerning the increased importance of community networks and engagement. But even here, new inequalities could emerge, with some communities able to become more self-organised than others.

Effects of the macro-level – widening the academic/vocational divide?

The influence of the macro-system in terms of national policy and regulatory frameworks was always present, whether this be the power of funding or the impact of curriculum and qualifications. Interestingly, different types of learning disruption may have added to the historical divide between academic and vocational learning in the English upper secondary system. As reported earlier, teacher assessment of GCSEs and A Levels has led to an increase in the number of young people applying for university, whereas Sector-based ILR statistics point to a decline in participation in vocational courses, particularly among adults. As a consequence, the academic track, which includes the critical transition to higher education, may be expanding whereas the vocational track could be shrinking. Viewed historically, growing attainment rates in GCSEs and A Levels in 2020–21 appear to correlate with growth phases of the academic track in the late-1980s and early 2000s and to diverge from the policy inspired attainment and participation ‘stagnation’ since 2012 (Rogers and Spours Citation2020). By way of contrast, participation and attainment in TVET including apprenticeships have indeed gone into reverse, with the Institute for Fiscal Studies confirming this trend, particularly at the lower levels. In 2020, there were only 3% of 16- and 17-year-olds in apprenticeships and only 2% in employer-funded training – ‘both at their lowest levels since at least the 1980s’ (Sibieta and Tahir Citation2021, 2). As the IFS noted, this trend would be unprecedented in recent decades because college-based TVET has consistently performed the ‘heavy lifting’ in terms of rising participation and attainment of 14–19-year-olds, notably at Level 3 (Rogers and Spours Citation2020).

Mitigation strategies – from short-term steps to comprehensive ‘COVID recovery ecosystems’

‘Complex problems require complex solutions’ (Hersen Citation1981; Ward et al. Citation2011). The complex inter-relationship between the various scalars of harms (from the micro-macro) affecting different aspects of working, living and learning has given rise to calls for comprehensive recovery programmes (e.g. AoC Citation2020b; LGA Citation2020). Some of these are sector-based, whereas others are area-based. However, taken together, they could be seen to constitute the building of learning and skills recovery ‘ecosystem’ (Grainger and Spours Citation2018) adapted to the COVID Decade.

This mitigation discussion thus mirrors the previous one focused on harms by briefly discussing key support activities at the different ecosystem levels that are supported by research. But first, as reported in the mitigations evidence section, systematic review evidence is very clear about the basic actions of this system approach – targeting support at key vulnerable groups; creating comprehensive local recovery plans; building a multi-agency approach involving collaboration between key civil society actors at the local and sub-regional levels; and a strategic and facilitating approach by national government. A key conceptual question is how these linked actions might be practiced across the multiple scalars of the recovery ecosystem.

The chrono dimension – creating longer-term approaches

COVID recovery ecosystems suggest a longer-term approach. Thus far, however, the Government has confined its approach to relatively short-term steps including government guidance to FE providers, additional funding, IT resources and special programmes; the role of national agencies such as awarding bodies and Ofqual in terms of assessment flexibilities to assist vocational catch-up; adapted Ofsted inspections and monitoring visits and college-based support measures aimed at particular cohorts of learners. These measures, which are essentially short term to address the immediate and foreseeable impacts of the pandemic, have been largely welcomed by Sector leaders as both timely and necessary. However, as we have seen earlier, Sector actors have also argued for a more comprehensive and multi-faceted strategy.

The micro-level – targeted support for vulnerable learners and improved rights for all

While FE institutions have always tried to support their learners, particularly the more socially and educationally vulnerable, systematic review evidence has highlighted the importance of the funding and organisation-personalised support packages and the offer of additional learning opportunities such as summer schools. In addition, as can be seen from Sector-based evidence, the pandemic has led to calls from key Sector actors for a learning at skills entitlement for all learners. This is now policy in Scotland and Wales.

Beyond the institutional meso-level – the role of multi-agency local collaboration

While the supporting role of further education institutions is absolutely vital, the potential of a longer-term approach is to be found at the levels above. It is on the middling scalars of the recovery ecosystem, embracing the local economy and various civil society actors, that arguably the most decisive action can be created. Systematic reviews provided consistent evidence of potentially transferable mitigations including the provision of significant incentives for employers to expand work-based learning and particularly apprenticeships and collaborative multi-agency interventions at the regional and local levels that bring together job placements; relevant careers education and guidance; personal support for vulnerable learners. The building of this middling level of the recovery ecosystem would also see the further development of strong collaborative local and sub-regional networks comprising FE Sector providers, schools, HE institutions, employers and work-based learning providers together with a range of civil society organisations implementing comprehensive recovery plans that addressed fundamental structural issues of working, living and learning laid bare by the pandemic.

The macro level – national government actions count

While the middle or intermediate levels of the COVID recovery ecosystem are vital to its successful operation, systematic review evidence also pointed to the crucial role of national government at the macro-level. It is here that overall health and economic policies and strategies are devised in order to provide a framework of support for those at the lower levels within the social ecosystem. At the same time, systematic review evidence also suggested that it was important for national governments to devolve important responsibilities to the lower levels in order to harness local knowledge and support networks of civil society actors.

Concluding reflections – methodological and strategy-related

The methods of this rapid review will be of interest to readers who wish to match the evidence of effective mitigations against harms specific to their contexts. We employed a novel, mixed methods systematic review methodology that combined the advantages of matching the best available evidence of mitigations to specific harms identified in the latest research relevant to the UK FE sector at the time of COVID19 as it happened. The interviews with key stakeholders anchored the findings into real-world implications of implementation and decision-making going forward, overcoming some of the limitations of the time lag in the availability of research in a time-sensitive context.

Despite the challenges of researching an under-research sector, we found a point of agreement between systematic review evidence and the views of the Sector concerning effective strategies to address the entanglement of COVID harms. Common mitigation themes include focused funding for the most vulnerable; guarantees of training and employment for all young people; multi-faceted support measures and local collaborative systems. Some of these are being implemented by the governments of Scotland and Wales, but not by the Westminster Government. Measures in England, on the other hand, have been essentially short term along with the distant promise of infrastructure investment. What is needed in addition is a comprehensive recovery plan and collaborative networking that we have termed a ‘COVID recovery ecosystem’. Without this type of holistic approach, the deepening inequalities of the pandemic risk becoming further entrenched.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ken Spours

Ken Spours is a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Capital Normal University, Beijing. He is also Emeritus Professor of Post-Compulsory Education at UCL Institute of Education, specializing in post-14 curriculum and qualifications, organization and governance and further education and skills. His most recent research includes a study of the impact of COVID on further education and the concept of the Just Transition applied to further and higher education.

Paul Grainger

Paul Grainger’s expertise is in skills education. He was Principal of a College in Liverpool before moving to UCL in 2006, as Co-Director of the Centre for Education and Work. He is now a Senior Research Associate and continues to undertake research into strategic skills planning, management, and governance development within the TVET sector. Paul has been a member of the G20 Task Force on the Future of Work since 2018 and in 2021 he was appointed as Co-Chair of the Task Force on Digital Transformation. He is a member of the Internet Governance Group (GIDE) which advises the G7 group of nations.

Carol Vigurs

Carol Vigurs is a Senior Research Fellow with the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Coordinating Centre (EPPI Centre) in the Social Research Institute at UCL. Her interests are in systematic review methods for policy and practice, including health and social care guidelines, realist review methods, rapid review methods, systematic mapping and living maps.

Notes

1. A complete account of the research methodology and detailed findings can be found in the research report – Spours, K. Grainger, P. and Vigurs, C. Citation2021. Mitigating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the further education sector – a rapid evidence review, UCL Social Research Institute, EPPI Centre.

2. The concept of a COVID learning and skills equilibrium is an adaptation of the Finegold and Soskice ‘Low Skills Equilibrium’ (Citation1988) model of economic and skills stagnation.

References

- AoC. 2020b. Rebuild: A Skills-led Recovery Plan - https://www.aoc.co.uk/sites/default/files/REBUILD%20-%20A%20skills%20led%20recovery%20plan%20%28full%20doc%29%20FINAL_0.pdf accessed 17 May.

- Association of Colleges (AoC). 2021a. Coronavirus Resource Hub - https://www.aoc.co.uk/covid-19-resources accessed 8 December 2021a.

- Bank of England. 2021. The impact of the Covid pandemic on SME indebtedness https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/bank-overground/2021/the-impact-of-the-covid-pandemic-on-sme-indebtedness accessed 22 January 2022.

- Birdwell, J., M. Grist, and J. Margo 2011. The forgotten half: a demos and private equity report - https://www.demos.co.uk/files/The_Forgotten_Half_-_web.pdf?1300105344 accessed 1 July 2021.

- Briggs, B., D. Freeman, and R. Pereira 2021. “Understanding the Impact of Covid-19 on UK Population” – ONS - https://blog.ons.gov.uk/2021/01/25/understanding-how-the-pandemic-population/ Accessed 11 July 2021.

- British Academy. 2021. The COVID Decade: Understanding the long-term societal impacts of COVID-19 - https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/3238/COVID-decade-understanding-long-term-societal-impacts-COVID-19.pdf accessed 7 December 2021.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and S.J. Ceci. 1994. “Nature-nurture Reconceptualized in Developmental Perspective: A Bioecological Model.” Psychol. Rev 101 (4): 568–586. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.568.

- Castelli, S., P. Grainger, S. Goldberg, and B. Sethi 2021. “Education and Training: Recovering the Ground Lost during the Lockdown. Towards a More Sustainable Competence Model for the Future” G20 Insights https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/education-and-training-recovering-the-ground-lost-during-the-lockdown-towards-a-more-sustainable-competence-model-for-the-future/ accessed 21 May 2021.

- City and Guilds Group. 2020. Act Now or risk levelling down the life chances of millions. https://www.cityandguildsgroup.com/research/act-now-or-risk-levelling-down-the-life-chances-of-millions [ Accessed 13 May].

- Collinson, A. 2020. The new class divide – how Covid-19 exposed and exacerbated workplace inequality in the UK - https://www.tuc.org.uk/blogs/new-class-divide-how-covid-19-exposed-and-exacerbated-workplace-inequality-uk Accessed 7 December 2021.

- Department for Education. 2021. FE remote and blended learning case studies: Good practice developed during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/966511/FE_remote_and_blended_learning_case_studies.pdf [ Accessed 3 June].

- Department of Work and Pensions (DWP). 2021. Kickstart Scheme, 21 January https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/kickstart-scheme accessed 26 April.

- Elgar, F. J., A. Stefaniak, and M. Wohl. 2020. “The Trouble with Trust: Time-series Analysis of Social Capital, Income Inequality, and COVID-19 Deaths in 84 Countries.” Social Science & Medicine 263 (1982): 113365. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113365.

- Evans, S., and N. Clayton 2021. One Year On: The labour market impacts of coronavirus and priorities for the years ahead https://learningandwork.org.uk/news-and-policy/pandemic-has-widened-jobs-and-skills-inequalities-putting-levelling-up-at-risk/ accessed 26 April.

- Exley, S. 2021. Building an FE Research Community of Practice – Further Education Learning Trust (FETL) – https://fetl.org.uk/publications/building-an-fe-research-community-of-practice Accessed 4 June 2021.

- Fancourt, D., and A. Bradbury 2021. “We Asked 70,000 People How Coronavirus Affected Them – What They Told Us Revealed a Lot about Inequality in the UK”, The Conversation https://theconversation.com/we-asked-70-000-people-how-coronavirus-affected-them-what-they-told-us-revealed-a-lot-about-inequality-in-the-uk-143718 Accessed 15 May 2022.

- Farquaharson, C., J. Britton, and L. Sibieta 2019. Big New Money for Schools and FE, But FE Spending Still Over 7% Down On 2010 IFS, https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14370 accessed 2 June.

- Fazel, M., K. Hoagwood, F. Stephan, and T. Ford. 2014. “Mental Health Interventions in Schools in High-Income Countries.” The Lancet. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70312-8.

- Feng, Z., K. Ralston, D. Everington, and C. Dibben. 2017. “Long-term Health Effects of NEET Experience: Evidence from a Longitudinal Analysis of Young People in Scotland.” International Journal for Population Science 1 (1). doi:10.23889/ijpds.v1i1.327.

- Financial Times. 2020. UK universities see record admissions, despite the pandemic, https://www.ft.com/content/8f3ab80a-ec2b-427d-80ae-38ad27ad423d Accessed 16 May 1988.

- Finegold, D. 1999. “Creating self-sustaining, high-skill Ecosystems.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 15 (1): 60–81. doi:10.1093/oxrep/15.1.60.

- Finegold, D., and D. Soskice. 1988. “The Failure of Training in Britain: Analysis and Prescription.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 15 (3): 21–53. doi:10.1093/oxrep/4.3.21.

- Francis, B. 2021. Why research on remote learning offers hope https://www.sixthformcolleges.org/1412/blog-6/post/38/why-research-on-remote-learning-offers-hope accessed 27 April.

- Grainger, P., and K. Spours 2018. A Social Ecosystem Model: A New Paradigm for Skills Development? Insights T20 Argentina https://t20argentina.org/publicacion/a-social-ecosystem-model-a-new-paradigm-for-skills-development/

- Hagell, A., R. Shah, R. Viner, McGowan J. Hargreaves, and M. Heys 2019. “Young People’s Suggestions for the Assets Needed in the Transition to Adulthood: Mapping the Research Evidence” – Health Foundation Working Paper - https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2019/Health%20Foundation%20working%20paper%20assets%20final_v3.pdf accessed 21 May.

- Hart, A., A. Psyllou, S. Eryigit-Madzwamuse, B. Heaver, A. Rathbone, S. Duncan, and P. Wigglesworth. 2020. “Transitions into Work for Young People with Complex Needs: A Systematic Review of UK and Ireland Studies to Improve Employability.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 48 (5): 623–637. doi:10.1080/03069885.2020.1786007.

- Hersen, M. 1981. “Complex Problems Require Complex Solutions.” Behavior Therapy 12 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(81)80103-7.

- Hodgson, A., and K. Spours 2018. A social ecosystem model: conceptualizing and connecting working, living and learning in London’s New East https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A76419 accessed 2 July 2021.

- Hyland, T., and B. Merrill. 2010. “Community, Partnership and Social Inclusion in Further Education.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 25 (3): 337–348. doi:10.1080/03098770120077694.

- Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS). 2020. 2020 annual report on education spending in England - https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/15150 accessed 17 May 2021.

- International Labour Organisation (ILO) and World Bank. 2021. Skills Development in the Time of COVID-19: Taking Stock of the Initial Responses in Technical and Vocational Education and Training. Geneva: ILO.

- Local Government Association (LGA). 2020. Rethinking Local, https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/3.70%20Rethinking%20local_%23councilscan_landscape_FINAL.pdf

- Lupton, R., S. Thomson, S Velthuis, and L. Unwin 2021. Moving on from initial GCSE ‘failure’: Post-16 transitions for ‘lower attainers’ and why the English education system must do better https://mk0nuffieldfounpg9ee.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Post16-transitions-for-lower-attainers_summary.pdf accessed 3 June.

- Mann, A., V. Denis, and C. Percy 2020. “Career Ready? How Schools Can Better Prepare Young People for Working Life in the Era of COVID-19” – OECD - https://cica.org.au/wp-content/uploads/e1503534-en.pdf accessed 21 May.

- Mawn, L., EJ. Oliver, N. Akhter, CL. Bambra, C. Torgerson, C. Bridle, and HJ. Stain. 2017. “Are We Failing Young People Not in Employment, Education or Training (Neets)? A Systematic Review and meta-analysis of re-engagement Interventions.” Systematic Reviews. 6(16).

- McCulloch, A. 2021. “Which Apprenticeships are Worst Affected by Covid-19?”, Personnel Today, 8 February https://www.personneltoday.com/hr/which-apprenticeship-sectors-are-worst-affected-by-covid-19/

- Mylona, S., and H. Jenkins 2020. Survey of effect of Covid-19 on learners (2020) - Results summary – Welsh Government Social Research - Social Research Number: 25/2021 - https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2021-03/survey-of-effect-of-covid-19-on-learners-2020-results-summary.pdf

- National Audit Office (NAO). 2020. “Financial Sustainability of Colleges in England” ” https://www.nao.org.uk/report/financial-sustainability-of-colleges-in-england/ accessed 22 January 2022.

- Newton, B., A. Sinclair, C. Tyers, and T. Wilson 2020. “Supporting Disadvantaged Young People into Meaningful Work an Initial Evidence Review to Identify What Works and Inform Good Practice among Practitioners and Employers”. Institute for Employment Studies https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/548_0.pdf accessed 21 May.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). 2021a. “Youth Unemployment, January to March 2019 to October to December 2020”. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/adhocs/12960youthunemploymentjanuarytomarch2019tooctobertodecember2020 accessed 26 April.

- Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual). 2021. Grading GCSEs, AS and A levels in 2021 Setting out Ofqual’s decision on grading in 2021 and the rationale for that decision https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/940665/6720-2_Grading_GCSEs_AS_and_A_levels_in_2021.pdf accessed 16 May.

- ONS. 2021b. Young people not in education, employment or training (NEET), UK https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/bulletins/youngpeoplenotineducationemploymentortrainingneet/march2021 accessed 27 April.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD. 2020. Education and COVID-19: Focusing on the long-term impact of school closures - https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/education-and-covid-19-focusing-on-the-long-term-impact-of-school-closures-2cea926e accessed 22 January 2022.

- Orr, K. 2020. “A Future for the Further Education Sector in England.” Journal of Education and Work 33 (7–8): 507–514. doi:10.1080/13639080.2020.1852507.

- Outsource, Seetec. 2021. Apprenticeships: The Key to Social Mobility and ‘Levelling Up’ https://www.seetecoutsource.co.uk/insights/thought-leadership/apprenticeships-the-key-to-social-mobility-and-levelling-up/# accessed 8 December 2021.

- Parrett, S. 2021. “The Education Skills Crisis: Urgent Action Needed.” FE News, October 7.

- Prime Minister’s Office (2020) Major expansion of post-18 education and training to level up and prepare workers for post-COVID economy https://www.gov.uk/government/news/major-expansion-of-post-18-education-and-training-to-level-up-and-prepare-workers-for-post-covid-economy accessed 17 May.

- Quilter-Pinner, H., S. Webster, and H. Parkes 2020. Guaranteeing the right start - Preventing youth unemployment after Covid-19. IPPR https://www.ippr.org/files/2020-07/guaranteeing-the-right-start-july20.pdf accessed 12 May.

- Raffo, C., and S. Thompson 2021. Students who do not achieve a grade C or above in English and Maths https://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/project/students-who-do-not-achieve-a-grade-c-or-above-in-english-and-maths accessed 21 May.

- Rasheed-Karim, W. 2020. “The Influence of Policy on Emotional Labour and Burnout among Further and Adult Education Teachers in the U.K.” International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (Ijet) 15 (24): 232–241. doi:10.3991/ijet.v15i24.19307.

- Redrow. 2021. “Construction Careers and Apprenticeships post-coronavirus: The Impact of Earn while You Learn”. https://www.redrowplc.co.uk/media/3047/op21439725_apprenticeship_report_2021_v4.pdf accessed 12 May.

- Rogers, L., and K. Spours. 2020. “The Great Stagnation of Upper Secondary Education in England: A Historical and System Perspective.” British Educational Research Journal 46 (6): 1232–1255. accessed 16 May. doi:10.1002/berj.3630.

- Ruzicka, A. 2021. “‘How Does the Kickstart Scheme Work? 10 Key Questions Answered on the long-awaited £2bn Plan to Get Young People into Jobs’”, This is the Money https://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/smallbusiness/article-8694325/Kickstart-Scheme-does-work-good.html accessed 26 April.

- Sarygulov, A. 2021. Widening chasms - http://www.brightblue.org.uk/widening-chasms-analysis/ accessed 15 May.

- Savage, M. 2021. ‘Youth jobs scheme creates just 490 posts in north-east of England.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/apr/25/youth-jobs-scheme-creates-just-490-posts-in-north-east-of-england [ Accessed 26 April].

- Shemilt, I., D. Gough, J. Thomas, C. Stansfield, M. Bangpan, J. Brunton, K. Dickson, et al. 2021. Living Map of Systematic Reviews of Social Sciences Research Evidence on COVID-19. London: EPPI Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London.

- Sibieta, L., and I. Tahir 2021. Further Education and Sixth Form Spending in England. Institute for Fiscal Studies - https://ifs.org.uk/publications/15578 accessed 22 January 2022.

- Social Mobility Commission. 2021. The road not taken: the drivers of course selection: The determinants and consequences of post-16 education choices https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/973596/The_road_not_taken_-_drivers_of_course_selection.pdf accessed 12 May.

- Solvason, C., and G. Elliott. 2013. “Why Is Research Still Invisible in Further Education.” Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education 1 (6). doi:10.47408/jldhev0i6.206.

- South Australia Centre for Economic Studies. 2008. “Review of Initiatives into Workforce: Re-Engagement of Long Term Disengaged Workers” https://www.adelaide.edu.au/saces/ua/media/86/reviewofinitiativesintoworkforcereportsept2008.pdf accessed 21 May.

- Spours, K. 2021. Elite entrepreneurial and inclusive social ecosystems - https://www.kenspours.com/elite-and-inclusive-ecosystems accessed 8 December 2021.

- Spours, K., P. Grainger, and C. Vigurs 2021. Mitigating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the further education sector – a rapid evidence review, UCL Social Research Institute, EPPI Centre. - https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=3838 accessed 31 January 2022.

- Vetsch, J, CE. Wakefield, BC. McGill, RJ. Cohn, SJ. Ellis, N. Sawyer Stefanic, SM. Zebrack, and UM. Sansom-Daly. 2018. “Educational and Vocational Goal Disruption in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors.” Psycho Oncology 27 (2): 532–538. doi:10.1002/pon.4525.

- Waddell, G., A. Burton, and N. Kendall 2008. “Vocational Rehabilitation: What Works, for Whom, and When?” https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/209474/hwwb-vocational-rehabilitation.pdf

- Ward, P.R., S.B. Meyer, F. Verity, T. Gill, and T. Luong. 2011. “Complex Problems Require Complex Solutions: The Utility of Social Quality Theory for Addressing the Social Determinants of Health.” BMC Public Health 11 (1): 630. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-630.

- What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth. 2015. Evidence Review 8 Apprenticeships - https://whatworksgrowth.org/public/files/Policy_Reviews/15-09-04_Apprenticeships_Review.pdf accessed 21 May.

- Youth Employment, UK. 2021. New Inquiry Launch – APPG for Youth Employment - https://www.youthemployment.org.uk/new-inquiry-launch-appg-for-youth-employment/