ABSTRACT

This study presents a distinctive type of Muslim gravestone found on the northern coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, that dates to the 15th century. These grave markers, locally known as plang-pleng, provide evidence for the formation and disappearance of an early form of vernacular Muslim material culture in Southeast Asia. We documented over 200 of these gravestones during a large-scale archaeological landscape survey. In this article, we present a typology of these gravestones based upon shape, morphology and ornamentation. We then discuss their geographical distribution and periodisation based on examples with dated Arabic inscriptions. Our results show that these gravestones were initially a cultural product of the historic trading settlement of Lamri dating from the early 15th century. By the middle of the 15th century, variations of these stones started to appear widely near the Aceh river. The plang-pleng tradition was displaced in the early 16th century by the batu Aceh gravestones associated with the Aceh sultanate, which became a standardised part of Muslim material culture in the region for the next two centuries.

Introduction

The Indonesian archipelago, at the confluence of Indian Ocean and South China Sea circuits of maritime commerce and culture, has long been a meeting point for traders (Wang Citation1958; Wolters Citation1967, Citation1970; Chaudhuri Citation1985; Lombard Citation1990; Reid Citation1993). By the turn of the 14th century, the flow of people and ideas eastwards across the Indian Ocean and westwards from the South China Sea made island Southeast Asia a rolling frontier in the expanding world of Islam,Footnote1 with major Islamic communities developing along the coast of northern Sumatra. The early Islamisation of island Southeast Asia saw local cultural traditions transforming themselves through dynamic engagement with complex and changing configurations of trans-regional Islamic influences. This resulted in the development of distinct vernacular forms of Islamic material culture across the region, ranging from mosque architecture to manuscript styles. These artifacts engaged with broader patterns recognisable as Islamic across wide reaches of the Afro-Eurasian ecumene, while also integrating distinctive local elements into forms that were specifically marked as meaningful in Islamic terms, to new Muslim communities across the region.Footnote2

These vernacular forms of Muslim material culture in Southeast Asia have, however, historically been neglected within mainstream studies of Islamic art history which have long taken the cultural products of the Nile-to-Oxus region as normative frameworks for the field more broadly. While engagement with the pre-Islamic legacies of the Mediterranean world has produced an easily recognisable range of forms that have long defined dominant conceptions of ‘Islamic art’, only recently have scholars taken on the challenge of engaging with how the analogous legacies of Indic, African and East Asian aesthetic traditions have contributed to material culture developments across broader stretches of the expanding post-classical Muslim world.Footnote3

In this paper we analyse a distinctive and geographically localised corpus of 15th-century stone grave markers found in what is today the Indonesian province of Aceh. The northern tip of the island of Sumatra was home to some of the earliest footholds of Islam in Southeast Asia and this stretch of coast became a thriving hub of regional Muslim culture (Feener et al. Citation2011). These gravestones, locally known as plang-pleng, are concentrated in an area that can be identified with the historic trading site of Lamri, which flourished on the Ujong Batée Kapal headland during the 15th century (Daly et al. Citation2019a; Daly et al. Citation2019b; Sieh et al. Citation2014). These stones index a strikingly different visual language than those associated with the other major Islamic port polities along the northern coast of Sumatra: the Pasai and Aceh sultanates (Guillot and Kalus Citation2008; Daly et al. Citationunpublished). Here we present a detailed study of the morphology, decorative styles, chronology and epigraphy of the plang-pleng gravestones to explore a heretofore unstudied body of material that presents a unique example of early Islamic aesthetics and material culture in island in Southeast Asia.

Gravestones in the historiography of Islam in Southeast Asia

The environmental and material conditions in island Southeast Asia pose particular challenges to students of art history and material culture as the warm, wet climate of the region makes long-term preservation of the perishable materials generally used in the production of architecture and other objects extremely difficult. Wooden mosques, bark paper manuscripts, buffalo leather puppets and textiles do not often last long in conditions of tropical storms, high humidity, and massive insect infestation. One of the few exceptions to this problem of preservation of the region’s material culture comes in the form of stone gravestones – and for this reason the study of gravestones has taken on a perhaps disproportionately large role in research on the early history of Islam in Southeast Asia.Footnote4

The presence of Arabic inscriptions on gravestones has attracted the attention of scholars of the history of Southeast Asia for more than a century. Pioneering studies by Ravaisse (Citation1925), Damais (Citation1957), Moquette (Citation1921), Winstedt (Citation1918) and others identified inscriptions that became standard points of reference in many studies of the early history of Islam in the region. Work on Muslim gravestones in the region entered a new phase in the 1980s with a flurry of work by scholars including de Casparis (Citation1980), Tjandrasasmita (Citation2009), Ambary (Citation1984), Chen (Citation1992), Montana (Citation1997), and Bougas (Citation1988) further expanding the corpus of known inscriptions contributing to this historiography. Generally speaking, these studies focused on deciphering textual inscriptions and especially on identifying names and dates to provide a chronology of Islamisation in the region.Footnote5

Over the past two decades, Ludvik Kalus and Claude Guillot’s extensive work on Islamic epigraphy from the region has brought major innovations to the study of Muslim gravestones through their critical reconsideration of earlier interpretations of familiar monuments, as well as their publication of a large amount of previously unstudied inscriptions.Footnote6 Within the broad corpus of inscriptions that these scholars have examined in Southeast Asia, northern Sumatra features prominently as the location of more early Muslim graves than anywhere else in the region – at least according to our current state of knowledge. Kalus and Guillot have conducted invaluable studies of material from Barus (Guillot Citation1998; Kalus Citation2003; Perret et al. Citation2009) as well as at a number of other early Muslim states in Sumatra, including Daya (Kalus and Guillot Citation2013), Pedir (Kalus and Guillot Citation2009a), Peudada (Kalus and Guillot Citation2012), and the Aceh sultanate (Kalus and Guillot Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2009c; Citation2010, Citation2014a, Citationb; Citation2015, Citation2017a, Citation2017b), but their most extensive work has been on the epigraphy of Muslim gravestones found near the capital of the Sumatran sultanate of Pasai and other sites in Aceh.

In their book on Pasai, these two scholars have drawn on the epigraphic corpus of funerary inscriptions to present a wealth of information on royal genealogy, structures of governance, and connections between this early Sumatran sultanate and the agrarian polities of contemporary sultanates in India and the Middle East (Guillot and Kalus Citation2008). This work is a remarkable example of the historiographic use of the semantic content of gravestone inscriptions from early Muslim Southeast Asia, providing an entire new level of detail and nuance based on contemporary primary sources to our understanding of an important early Islamic port polity that was heretofore known almost exclusively through references to it in later Malay manuscript sources and early modern European accounts (Jones Citation1999, Citation2013).

Their broader body of work has characterised traditions of early inscribed Muslim gravestones in Southeast Asia as first emerging in the 14th century, flourishing in the 15th, and declining after the end of the 16th century as a reflection of fluctuations in the nature and extent of trans-regional circulations (Kalus Citation2018). In the case of Pasai, they attribute particular importance to the role of locally established ‘Turkish’ and South Asian migrant communities in the development of the court culture (Guillot and Kalus Citation2008: 71–74). In Brunei, by contrast, we see clear evidence of Chinese vernacular styles reflected in early Muslim gravestones (Franke and Ch’en Citation1973; Chen Citation1991, Citation1992; Kalus and Guillot Citation2003–Citation2004, Citation2006).

Kalus postulates that a significant rupture in vernacular traditions of Arabic epigraphy in the region is evidenced around the turn of the 17th century with the disappearance of ‘true epigraphy’ and the proliferation of ornamental ‘pseudo-epigraphy’.Footnote7 Arguing that the earliest surviving examples of inscribed monuments on Java and Brunei appear to be those dedicated to the memory of ‘foreigners’, Guillot and Kalus (Citation2018) highlight that the influence of Muslim émigrés from other lands was not only formative of local traditions, but that such sojourners played a dominant role in the subsequent maintenance and development of Southeast Asian traditions of inscribed Muslim gravestones (Guillot Citation2018). Unfortunately, however, their careful focus on the transcriptions of the texts are presented in ways that make it difficult to contextualise that semantic content in relation to the complete object on which the text is preserved. In their various publications, not all stones are illustrated with photographs, and those that are, often with only detail images of calligraphic panels that do not offer a visualisation of the wider shape of and ornamentation on the stone as a whole. As they are presented partially, and without any spatial data for the objects, it is impossible to know both the exact location and the relationship between stones at a particular site.

Through insightful studies integrating the critical reading of Arabic epigraphy with an art historian’s eye to material and form, Elizabeth Lambourn (Citation2004, Citation2008) has pushed the analysis of these monuments beyond a singular focus on epigraphy – without ignoring textual inscriptions – to open up further important lines of investigation that extend beyond the horizons of deciphering semantic contents from epigraphic sources. Lambourn (Citation2008: 252) approaches Muslim gravestones not (only) as a medium for the preservation of textual sources, but rather as an ‘integral cultural product’ in which text, visual content and material are equally important and interdependent. This is, for example, strikingly demonstrated in her critical re-evaluation of the stone bearing the oft cited epigraph for the Pasai Sultan Mālik al-Ṣāliḥ – where a death date from the late 13th century appears on an elaborate stone that was most likely produced in the early 16th century (Lambourn Citation2008). Approaching a wider range of material in northern Sumatra in this way, Lambourn also traces a line of development of ‘the emergence in the mid 1420s of the first significant numbers of tombstones of possibly local, that is Pasai, manufacture’ – and demonstrates the ways in which this particular style contributed to the development of the later well known tradition of batu Aceh (Lambourn Citation2004: 214).

Indeed much of the published research on Southeast Asian gravestones focuses on the batu Aceh tradition, a range of gravestone forms widely distributed across the Indonesian archipelago and parts of the Malay Peninsula that are associated with the Acehnese sultanate. Othman Yatim first proposed a hypothesis on the evolution of batu Aceh forms in 1985. Subsequently, Daniel Perret and Kamarudin AB. Razak undertook a systematic study of batu Aceh at sites in the Malay Peninsula to produce two massive catalogues which refined a typology of forms based on the physical characteristics of each stone (Perret and Razak Citation1999, Citation2004; Perret Citation2007). Hundreds of batu Aceh have been identified both further afield on Sumatra, as well as on the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, and Sulawesi by Perret, and on Sumbawa by Ambary. The wide geographic distribution of batu Aceh reflects the substantial cultural and political influence of the Aceh sultanate across the region between the 16th and 18th centuries.

In this article, we will present the emergence, flourishing, and ultimate eclipse of another form of locally produced Muslim gravestone along the coasts of northern Sumatra in the 15th century. This form arose parallel to the initial emergence of batu Aceh – and as we argue here, might have merged to include some elements characteristic of the classical period of batu Aceh in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Muslim gravestones of this type are referred to locally in Aceh as plang-pleng, an Acehnese term connoting ‘of varied decoration’ (McKinnon Citation2011: 145).Footnote8

One of the earliest inscribed Muslim gravestones on the northern coast of Sumatra – indeed anywhere in Southeast Asia – is found on the coast of Lubhok bay situated below the eastern edge of the Lamreh headland. Kalus and Guillot (Citation2018: 348) have dated this stone to 1389 (or 1369), and it has been identified as a possible antecedent for the plang-pleng stone tradition that flourished in this same area over the course of the 15th century.Footnote9 All that survives of this stone, however, is the lower portion bearing the date in a calligraphic panel. Its rectangular footprint is similar to those of some plang-pleng, but because everything above that has been lost it is impossible to locate it with any certainty within the typology we present here. It might then be considered grouped together with what we classify below as Type D, or it may indeed be related to another set of objects altogether.

Plang-pleng gravestones take the form of pillars with square or rectangular footprints that taper upward to rounded finials. They appear in a number of variations, with distinctive types that we identified in this article by specific elements of the shape of their finials, the elaboration of broadened bases, and by different programmes of ornamentation. Across these variations, however, plang-pleng comprise a set of objects visually distinct from all other types of Muslim gravestones in the region, including the slab gravestones of Pasai and batu Aceh (broadly conceived), which generally take the form of rectangular slabs, as well as of rounded or octagonal columns. The distinctiveness of this form of Muslim gravestones thus clearly set plang-pleng apart from previously studied types of gravestones in northern Sumatra. It has been suggested that the closest analogues to plang-pleng in terms of form in the region may be found in pre-Islamic ‘buffalo posts’ known from other parts of Sumatra – but the exact nature of any such connection remains at this point merely speculative.Footnote10

Our extensive documentation of this large sample of early Muslim gravestones both includes, but also looks beyond the semantic content of textual inscriptions to ‘non-epigraphic data’ (Lambourn Citation2004: 212). This has enabled us to provide the first close examination of a large data set of objects that have not previously received any sustained scholarly investigation.Footnote11 In what follows we present a focused, systematic investigation of this type of Muslim gravestone. This includes a stylistic typology dated provisionally in relation to a sample of tombstones inscribed with legible dates, and an account of their geographic range in relation to historical dynamics of northern Sumatra in the 15th century. Based upon this data, we then propose an interpretation situating this type of gravestone in relation to a broader history of aesthetic forms and material culture in early Muslim Southeast Asia.

Methods

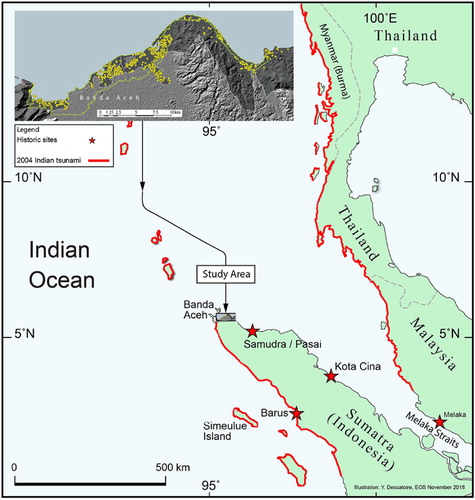

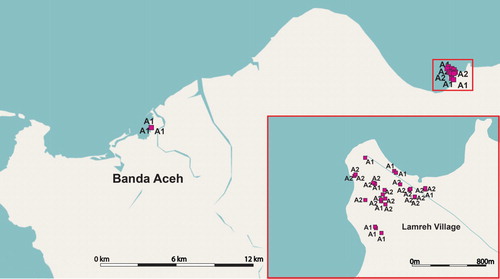

The data presented here derive from an extensive archaeological field survey conducted by a team of Acehnese researchers between 2015 and 2018 across approximately 40 km of coastal villages on either side of the city of Banda Aceh in northern Sumatra. The main aims of this project were to combine archaeological and geological data to determine if areas inundated by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami had been hit by previous historic tsunami, and to better understand the history of that coastal region before the rise of the Aceh sultanate in the 16th century (Sieh et al. Citation2014; Daly et al. Citation2019a; Daly et al. Citation2019b; Tai et al. Citation2020). The field team worked village by village to locate and document all historic material culture visible on the ground surface of the survey area (). This included structures, scatters of material culture such as ceramic sherds, and carved stone grave markers. They made detailed records for each grave marker that includes a physical description, GPS coordinates, and up to 30 photographs of each stone showing all sides, as well as close up shots of the main decorative motifs and calligraphic panels.

Figure 1. Map showing our survey area situated within the region. The inset map shows the areas we surveyed (in dark grey), with all archaeological sites depicted with yellow dots.

Our dataset provides a window into the ways in which distinctive Muslim cultural forms evolved within contexts of shifting maritime entrepôt during the 15th century – a period for which the gravestone and ceramic material provides for a much richer source base for understanding the early history of Islam in the region than was previously available through a patchwork of documentary references in Arabic, Chinese, Tamil, Javanese and Malay-language textual sources.Footnote12 We hope that the consideration of this new material might also prompt some broader reflection on the ways in which attention to the under-studied material culture of the maritime Muslim worlds of the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea might contribute to new understandings of the broader history of Islam and Muslim societies across this interconnected maritime world.

Using this data we develop a typology (presented below) of plang-pleng stones based upon physical morphology and decorative motifs. We also use GIS (geographic information system) to visualise the spatial distribution of the gravestones documented by this survey. Alongside the typology and spatial distribution of plang-pleng, we then propose a rough chronology based upon dates recovered from the sub-set of these stones that bear legible inscriptions – including a number of readings that have been published over recent years by Kalus and Guillot. Finally, we detail the main decorative motifs and styles of calligraphy on the gravestones.

Results

Our survey documented more than 5,000 carved gravestones, out of which 211 fit within the broad stylistic category designated locally as plang-pleng. All of these stones share a range of characteristics. They are oblique standing stones with squared or rectangular bases that rise to a pyramidal apex. They generally have tapered upper portions dominated by floral or geometric patterns and defined panels just above the base that contain floral designs, geometric designs, or calligraphy. Textual inscriptions, when present, are in Arabic script and generally appear in relief in panels just above the base. The texts comprise a range of pious formulae, Qur’anic verses, and – relatively rarely – the name of the deceased and/or date of death. All dated examples of plang-pleng stones come from the 15th century. The stones range from 0.3m to 1.2m in height – with most standing between 0.5m to 1m tall. All of the plang-pleng are carved from single pieces of stone of various types including locally quarried fossiliferous limestone, sandstone, and volcanic tuff. Based upon the stone used, Ed McKinnon (Citation2011: 147) has previously argued that many of them were ‘undoubtedly carved locally’. The condition of the stones varies considerably, from free standing, intact and well preserved, to highly eroded and in some cases, fragmentary. Many have been knocked over, partially buried, and/or damaged.

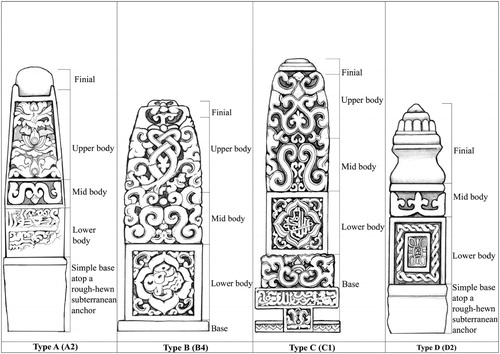

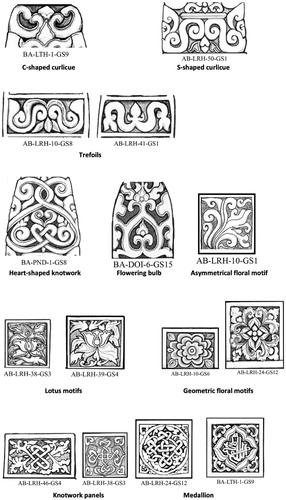

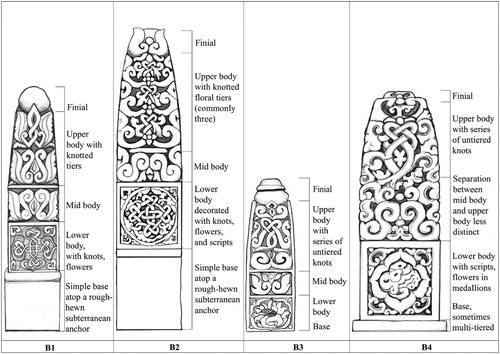

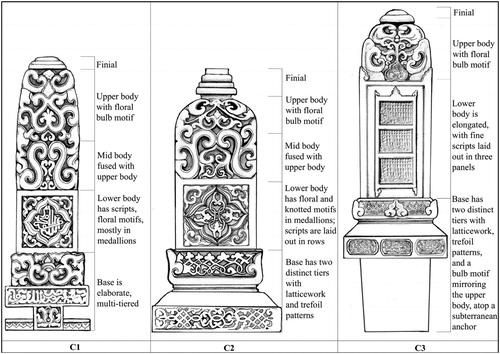

As shown in , in the construction of our typology we have conceptually divided the bodies of plang-pleng stones into five distinct diagnostic sections: the base, the lower body, the mid body, the upper body and the finial. As presented in detail below, analysis of the arrangement of these parts, and the composition of the various programmes of ornamentation contained within these parts, allows us to define four distinct styles: Types A, B, C and D – each of which contains sub-types (; ). Throughout our descriptive analysis of the types we reference a number of distinctive elements as outlined in a visual glossary of terms we use in and elaborate upon in the online supplement.

Figure 2. We identify four main types of plang-pleng, structuring our analysis around five potential segments of each stone (from top to bottom): the finial; upper body; mid body; lower body; and base. Type A (A2): AB-LRH-46-GS5; Type B (B4): BA-PND-2-GS12; Type C (C1): BA-LTH-1-GS9; Type D (D2): AB-LRH-26-GS1. Details of each of the types by segment of gravestone are provided in the online supplement Appendix 1 (drawings by Luca Lum En-Ci).

Figure 3. Examples of terminology used to describe decorative motifs in our analysis. For a more extensive visual glossary of types of decoration refer to online supplement Appendix 2 (drawings by Luca Lum En-Ci).

Table 1. Summary counts of graves by type and sub-type. Here we distinguish them based upon geographic location as 89 stones are concentrated on the Lamreh headland associated with the historic trading port Lamri, while the rest are more dispersed in low-lying areas along the coast stretching towards the west. A complete inventory of all the graves in this study, including GPS coordinates, is provided in the online supplement.

Morphology and types

Type A

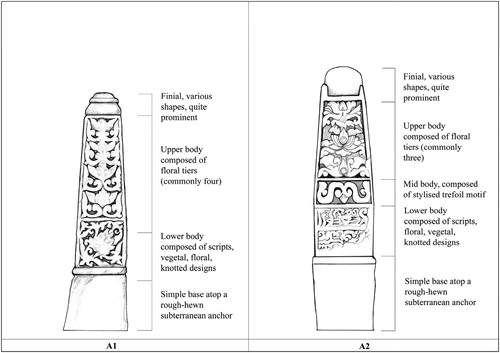

Type A plang-pleng are standing obelisks with a square (or sometimes rectangular) pillar footprint and straight sides that taper up towards a finial (). Like all plang-pleng, Type A stones have a roughly hewn subterranean segment with no distinguished demarcation at the base of the finished part of the stone. The lower bodies generally have panels with Arabic inscriptions or non-calligraphic ornamentation. In Type A1 stones this is followed by a sequence of repeated floral patterns on the upper body to the finial. Type A2 stones have a clear mid body containing a trefoil motif which wraps around the corners of the stone in a frieze, though some stones also have a distinct border around the ornamental carving on each side. The ubiquity of this trefoil and other ornamental motifs on plang-pleng – including a distinctive four-petalled flower – are reminiscent of elements also common on early Muslim gravestones in south India.

Figure 4. Type A can be separated into two sub-types, A1 and A2, and both are characterised by repeated tiers of floral motifs on the upper body. A1 stones tend to be slightly asymmetrical and lack the distinct mid body found on A2 (drawings by Luca Lum En-Ci).

We have identified a total of 50 Type A plang-pleng, which we place into two sub-types: A1 (20 stones) and Type A2 (30 stones).

A1 characteristics

A1 stones share a standard programme of ornamentation but can take slightly irregular forms. The gently tapering upper bodies of A1 plang-pleng take up most of surface area of A1 stones. This sub-type lacks the rectangular mid body section found in A2 plang-pleng. A1 stones are generally wider at the front and back than at the sides, making for a more rectangular footprint.

A1 finial. A1 plang-pleng are topped by finials that rise a few centimetres above the upper body. This section is generally unornamented on Type A1 plang-pleng (S1 Fig. 1).

A1 upper body. The upper body covers roughly 70% of the surface area of the exposed stone (excluding bases that were intended to be buried). Almost all of the stones in this category have highly distinctive tiers of floral patterns that extend upwards, towards the finial. The main motifs are blossoms executed in varying degrees of stylisation, as well as other buds and four-petalled flowers. Another pronounced feature of these ornamental programmes are prominent C-shape curlicue arms extending from the central floral motifs. Some of the floral patterns are open and in full bloom while others resemble halved trefoil motifs. Ornamental extensions to either side of the central blossom on each face of the stone often wrap around the corners to form a frieze of repeating trefoil patterns (S1 Fig. 2).

A1 mid body. A1 plang-pleng do not have a distinct mid body section.

A1 lower body. The lower body contains square panels within clearly demarcated frames on all four faces of the stone. These panels contain a range of asymmetrical floral and vegetal patterns, symmetrical floral patterns, knotwork, and Arabic-script calligraphy, either in clearly defined rows of text or amalgamated across the entire panel. Lotus and other floral motifs are particularly common in lower body panels (S1 Fig. 3).

A1 base. The ornamented lower body section is separated from the buried anchor by a slight finished ridge (S1 Fig. 4).

A2 characteristics

A2 plang-pleng generally have consistent body shapes, typically with slightly curved sides and more clearly defined edges than those found on A1 plang-pleng. A2 stones have distinct mid body sections differentiated from the upper body by a clear border. This clearly defined mid body usually replaces at least one ornamented tier in the upper body. These stones present a somewhat pyramidal appearance, and are wider across the front and back faces than at the sides.

A2 finial. A2 finials are relatively prominent compared to A1 finials. A common type of finial has its width spanning the top of the upper body, though others are narrower than the width of the stone at the top of the upper body. These finials take various shapes: tapering, boulder-like, flat at the top, or pot-like in appearance and stacked in tiers of decreasing width as they rise (S1 Fig. 5).

A2 upper body. The upper body contains repeated tiers of floral patterns of either lotus, four-petalled flowers, or trefoil, which sometimes wrap around the stones to form a frieze. The motifs may be unified or segmented into clearly defined bands (S1 Fig. 6).

A2 mid body. The mid body sections commonly contain variations on a vine motif, often taking the form of a trefoil shape that wraps around the stone in a frieze (S1 Fig. 7).

A2 lower body. The lower body sections are defined by square and rectangular panels containing floral and geometric motifs, knotwork patterns, and Arabic-script calligraphy. Floral motifs are common in the lower body sections. Corner elements, in the shape of leaves or curlicues are present on some stones, usually accompanying simple medallion forms (S1 Fig. 8).

A2 base. The ornamented lower body section is separated from the buried anchor by a slight ridge (S1 Fig. 9).

Type B

There is considerable variation in the shape and ornamentation found on Type B plang-pleng (). We identify Type B primarily on the basis of the decorative motifs on the upper bodies, where we see a clear shift away from the repeated floral tiers seen on Type A, and towards a more complex array of knotted and intertwined floral and geometric patterns that give the impression of less distinct tiers. Where a distinct mid body section is in evidence on Type B stones, the ornamentation often takes the form of two S-shape curlicues around a bud set beneath it. There are also clear differences in the ornamentation of the lower body panels. For example, there is a pronounced use of medallions to enclose lower body ornamental panels, and Arabic inscriptions also tend to take the form of medallions, rather than being presented in demarcated horizontal registers or filling the panel of the lower body section.

Figure 5. Type B can be separated into four sub-types B1 – B4. All the sub-types share a basic set of floral and geometric motifs. The mid body blends into the upper body on B4 stones. Sub-type B1: AB-LRH-38-GS3; Sub-type B2: AB-LRH-24-GS2; Sub-type B3: AB-LRH-10-GS1; Sub-type B4: BA-PND-12-GS2 (drawings by Luca Lum En-Ci).

Curlicue motifs appear at both the top of the upper body fringing the finial, and in the lower body of the stone as borders framing medallion panels. Type B bases show some ornamentation, particularly in the form of a series of parallel horizontal lines, at least one of which may present some ornamentation in the form of scalloped lines or (more rarely) calligraphy. The faces of most Type B stones are not framed within borders, allowing the ornamentation to wrap around the four faces. There are, however, some exceptions to this in some sub-types (B2 and B3) included in our sample. We have identified a total of 50 Type B plang-pleng, which we place into 4 sub-types: B1 – 4 stones, B2 – 9 stones, B3 – 6 stones, and B4 – 31 stones) ().

B1 characteristics

B1 plang-pleng take the form of narrow obelisks with ornamental carving on all sides. They share some features with Type A stones, particularly with the presentation of distinct tiers of upper body ornamentation.

B1 finial. The top of these stones terminates in pronounced, rounded finials (S1 Fig. 10).

B1 upper body. The upper body typically comprises about half the height of the stone, ornamented with upwardly twisting floral and intertwined knot motifs that converge towards the finial (S1 Fig. 11).

B1 mid body. The mid body section is distinct and clearly separates the lower and upper body panels with a pronounced border. This section is ornamented with trefoil motifs and double S-shape curlicues (S1 Fig. 12).

B1 lower body. The lower body contains square panels with symmetrical floral designs, ornamental knotwork, heart-shape motifs, and four-petalled flowers. Some examples contain medallions inside the lower-body panel. Corner elements are often present in the framing around these medallions (S1 Fig. 13).

B1 base. There is no distinctive feature separating the ornamented section of the lower body from the rougher cut subterranean anchor section of sub-type B1 stones (S1 Fig. 14).

B2 characteristics

B2 stones are obelisks with a square base that taper towards the top. The stones of this sub-type demonstrate significant standardisation of style and carving technique.

B2 finial. The finials are rounded or pointed (S1 Fig. 15).

B2 upper body. The upper body is covered in dense and elaborate ornamental carvings of abstract patterns usually incorporating four-petalled flowers among sinuous knotwork running up the centre towards large curlicue motifs just below the finial (S1 Fig. 16).

B2 mid body. The mid body is clearly delineated and often ornamented with trefoil motifs. In at least one example, the mid body is ornamented with a lotus bud motif instead.

B2 lower body. The lower body contains square or rectangular panels featuring floral or vegetal motifs, elaborate geometric patterns, and/or and ornamental knotwork. Arabic calligraphy appears rarely, but when present it either fills the entire panel, or takes the form of calligraphic medallions (S1 Fig. 17).

B2 base. B2 stones have a slight lip at the base delineating the finished face of the stone from the rough-hewn subterranean anchor. This band is sometimes ornamented with a curved line motif that may suggest lotus petals (S1 Fig. 18).

B3 characteristics

B3 stones take the form of square-based obelisks. This sub-type is defined by a lack of demarcated tiers within the upper body section. The dominant ornamental motif is comprised of knotwork patterns.

B3 finial. This sub-type has pronounced finials, some ornamented with a ridged knob (S1 Fig. 19).

B3 upper body. The upper body lacks the distinct tiers found in Type A or sub-types B1 and B2. The most prominent ornamental motif on the upper bodies is knotwork, interlaced with pendant, heart-shape, vegetal, and floral elements. A pair of curlicue motifs are usually found just below the finial (S1 Fig. 20).

B3 mid body. The mid body section is generally ornamented with trefoil motifs (S1 Fig. 21).

B3 lower body. The lower body contains square panels framing ornamental carving in floral and knotwork patterns or, less frequently, Arabic calligraphy (S1 Fig. 22).

B3 base. This sub-type does not have a distinct base separating the lower body from the unfinished subterranean anchor (S1 Fig. 23).

B4 characteristics

There is significant variation within the B4 form. Most of these stones demonstrate a high calibre of craftmanship that is characterised by elaborate knotted geometric and floral patterns. There are generally no distinguishable tiers in the upper body, and an increased emphasis on negative space in the carving.

B4 finial. B4 stones generally have understated flat or slightly rounded tops with no distinct finial. Just below, near the very top of the upper body, a floral or bud motif is often placed on the crown. It is also very common to see this motif flanked by a pair of C-shape curlicues. In some B4 stones, these motifs are cruder, carved with less detail, and are shaped more like spirals or commas (as also seen in some B2 and B3 stones) (S1 Fig. 24).

B4 upper body. The central ornamental motif on the upper body sections is knotwork, usually surrounded by a complex array of curls that tighten towards the sides of each face. These ornamental motifs are not presented in separate tiers. The knot patterns vary – some are heart-shape, while others take the form of stars, or more abstract patterns. Often, curlicue arms extend from the knots, and curve outwards and downwards, towards the mid body to form the shape of an upside-down heart enclosing smaller knotwork or floral motifs (S1 Fig. 25).

B4 mid body. The ornamentation of the mid body features either a trefoil motif, or a squat lotus bloom. It is common for the upper border between the mid body and upper body sections to be marked by a partial horizontal line somewhat de-emphasising the mid body as a distinctive register. The smaller B4 stones lack a distinct mid body section (S1 Fig. 26).

B4 lower body. The lower body sections contain well defined square or rectangular panels framing lotus and/or abstract floral and geometric motifs, or Arabic calligraphy in the form of medallions – though more extensive inscriptions filling the panel are found in a small number of examples. The motifs of the lower body show a trend towards symmetry, as only a few of the stones include the kind of asymmetrical floral or vegetal ornamentation found on B3 or Type A stones. Most motifs are enclosed within medallions, often flanked in four corners by curlicues. If the lower body does not include a medallion, the ornamentation of this section still follows a similar pattern and is flanked at four corners by a simpler leaf motif (S1 Fig. 27).

B4 base. B4 stones have a range of different bases, most with some form of distinct base section separating the ornamented lower body panels from the subterranean anchors of the stone. Most of the bases take the form of a simple squat pedestal, although some are ornamented with a curved line pattern that may indicate lotus petals (S1 Fig. 28).

Type C

The footprints of Type C plang-pleng are generally more square than elongated rectangular in shape. Type C stones do not feature clearly demarcated tiers in the ornamental programme of the upper body. The distinct mid body sections seen in Type B and sub-type A2 are absent here, with that range fully incorporated into the upper body of Type C stones (). In some of the shorter Type C stones, defined mid body sections are entirely absent. The dominant ornamental pattern is a flowering bulb motif, which we interpret as a further variant of the range of trefoil and heart design elements common across nearly all plang-pleng. The lower bodies are marked by square panels of symmetric floral or geometric ornamentation, or with calligraphic medallions. Similar to Type B, the medallions are bordered with corner elements in the form of winged curlicues or leaves. Like Type B, Type C stones also have C-shape curlicues at the top of the upper body section. However in Type C stones, the C-shape curlicues are larger and more defined than those of Type B. Type C plang-pleng have well defined tiered bases, some banded with geometric ornamentation.

Figure 6. Type C can be separated into three sub-types C1 – C3. There is considerable variation between the sub-types. All three sub-types contain elements that become common within the later classical batu Aceh gravestones, in particular, the elaborate pedestal bases and the crowned calligraphic panels found on C3. Sub-type C1: BA-LTH-1-GS9; Sub-type C2: AB-LBT-1-GS1; Sub-type C3: AB-MRK-1-GS1 (drawings by Luca Lum En-Ci).

Type C is also distinguished from Types A and B by the inclusion of a number of formal features generally associated with the batu Aceh tradition, such as more distinct and elaborate finials. Additionally, some Type C stones have wider, multi-tiered pedestal bases with extensive ornamentation featuring motifs common on many types of batu Aceh. One Type C (AB-MRK-1-GS1) in our sample even has an extended calligraphic panel extending upwards through the body of the stone, producing a long rectangular window of text framed in three horizontal panels. This layout matches, almost exactly, that used to frame calligraphic inscriptions on stones of the batu Aceh tradition. We have identified a total of 57 Type C plang-pleng, which we place into 3 sub-types: C1 – 47 stones, C2 – 6 stones, and C3 – 4 stones ().

C1 characteristics

C1 stones feature an ornamental motif in the upper body that looks like a flowering bulb with an inverted heart-shape trefoil bud inside of it. The stones show some variance in the delineation of a distinct mid body section and degree of elaboration at the base.

C1 finial. The finials comprise one, two, or three tiers and can be flat, rounded or slightly pointed at the top (S1 Fig. 29).

C1 upper body. In all C1 stones, the curlicues in the upper body form a motif composed of a flowering bulb. Several stones show identical motifs or motifs with only slight variation. In some cases the bulb encloses Arabic calligraphy (S1 Fig. 30).

C1 mid body. The mid body sections are not clearly distinct from the upper body sections. Ornamentation generally takes the form of a pair of S-shape curlicue motifs. In the smaller stones, a distinct mid body section is completely absent (S1 Fig. 31).

C1 lower body. The lower body sections comprise square or rectangular panels, often with symmetrical ornamentation in the form of floral medallions bordered on the four corners by winged curlicues or vegetal motifs. Some examples, however, present ornamentation (including calligraphy) that does not take the form of medallions. The smallest C1 stones, for example, have more petite and simplified geometric or floral motifs and inscriptions presented in multiple horizontal registers (S1 Fig. 32).

C1 base. C1 stones have elaborate, multi-tiered bases. The ornamentation on the various tiers can include floral patterns, curlicue motifs, or Arabic calligraphy (S1 Fig. 33).

C2 characteristics

The overall taper of the upper body and the shape of the finial create a less pointed look to this sub-type. The proportion of the upper body (with integrated mid body) to the lower body is about 50:50, and the base features elements that clearly distinguish these stones from Type C1.

C2 finial. The large finials are flat-topped with multiple tiers (S1 Fig. 34).

C2 upper body. The upper body sections feature the flowering bulb motif, flanked by curlicues. Another pair of C-shape curlicues often crowns the top of the upper body (S1 Fig. 35).

C2 mid body. The mid body sections are integrated with the upper body with no distinct borders. The ornamentation features mirrored S-shape curlicues. On some stones, however, these are replaced by a bulbous shape (S1 Fig. 36).

C2 lower body. The lower body section features medallions with knotted and/or floral motifs flanked by winged curlicues at the corners. Inscriptions, where present, are presented in horizontal rows within these panels (S1 Fig. 37).

C2 base. This sub-type has multi-layered bases, the upper registers of which take the form of jutting sills that feature patterns in the form of a chain of delicate knotted trefoil motifs. The lower tier slopes downwards from the first tier in the shape of a rectangular block, ornamented with a knotwork frieze (S1 Fig. 38).

C3 characteristics

C3 stones are notably distinct from all other C sub-types, and indeed from all other types of plang-pleng. The upper body takes up a much smaller proportion of the stone, while the lower body takes up most of the visible surface. The central motif of the upper body is a trefoil motif encapsulated within a stylised flowering bulb. Type C3 stones contain a number of decorative elements that are found on the later batu Aceh stones common within our study zone, and might thus be viewed as something of a transitional form.

C3 finial. The finials are composed of two layers, slightly rounded at the top (S1 Fig. 39).

C3 upper body. The upper body is considerably shorter than those of C1 and C2. A pair of large C-shape curlicues are positioned directly beneath the finial. The major ornamental feature here is a flowering bulb, flanked by another pair of large C-shape curlicues (S1 Fig. 40).

C3 mid body. There is no distinct mid body section.

C3 lower body. The lower body sections feature a long vertical rectangular window framing three (or more) horizontal panels of Arabic calligraphy. The layout and ornamental framing of these panels are similar to those found on batu Aceh type gravestones (S1 Fig. 41).

C3 base. Similar to sub-type C2, the bases of C3 are multi-layered. The upper tier takes the form of a jutting sill ornamented with a panel containing a chain of knotted trefoil wrapping around the corners to form a frieze. Further elaboration of the ornament on this register of C3 feature the prominent placement of an additional larger trefoil in the middle of each panel. The lower tier takes the shape of a rectangular block on each face of which are carved three lozenge-shape panels ornamented with knotwork motifs (S1 Fig. 42).

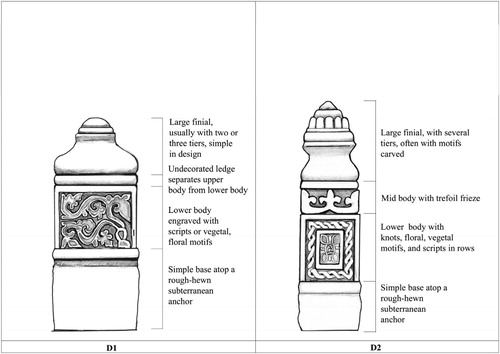

Type D

Type D stones present the furthest outliers in terms of style in this typology of plang-pleng grave markers. We include analysis of Type D stones because there are a number of significant similarities in both the basic form and shared ornamental motifs, their spatial distribution and chronological range overlap considerably with those of Type A, B, and C plang-pleng, and they have not received focused attention in previous scholarly publications. The basic pillar form of Type D stones rise from rectangular or (more rarely) roughly square footprints (). They have elongated and sometimes elaborately tiered finials. A number of Type D stones have large lower bodies with ornate carvings. We have identified a total of 11 Type D plang-pleng, which we categorise into 2 sub-types: D1 – 6 stones and D2 – 5 stones ().

Figure 7. Type D can be separated into two sub-types D1 and D2. The carvings of these stones differ significantly from the other types of plang-pleng. Type D stones have multi-tiered and sometimes elaborate finials. Sub-type D1: AB-LRH-59-GS1; Sub-type D2: AB-LRH-26-GS1 (drawings by Luca Lum En-Ci).

D1 characteristics

D1 stones are visually distinct in that significant portions of the stone face form part of extended and usually unornamented finials. These usually take the form of multi-tiered, curved bulbous forms set above the lower body for sub-type D1. D1 stones are characterised by thick, unornamented dividing lines separating lower body from the upper body. D1 stones lack a clearly defined mid body.

D1 finial. Finials take relatively simple, squat-looking bulbous forms topped with a narrower rounded tip (S1 Fig. 43).

D1 upper body. Type D1 stones do not present a distinct upper body section (, S1 Fig. 44).

D1 mid body. Type D1 stones do not present a distinct mid body section ().

D1 lower body. The most common forms of ornamentation on the lower bodies are multi-lobed vegetal or floral designs. Their execution can, however, range considerably from symmetrically stylised to more naturalistic. Calligraphy is present in panels of text, and a lone example (AB-LRH-1-GS17) prominently features calligraphy on both the upper and lower body sections (S1 Fig. 43).

D1 base. The base comprises a thick ornamented ledge, demarcating the ground level between the ornamented faces of the stone and its rough-hewn subterranean anchor (S1 Fig. 46).

D2 characteristics

On D2 stones a significant portion of the main body merges seamlessly into extended and usually unornamented finials. These usually take the form of multi-tiered, curved bulbous forms set above an ornamented band around the mid body. D2 mid bodies often feature a pair of halved trefoil, joined to a rectangular border separating the upper body from the lower body section.

D2 finial. The finials take squat-looking forms, which may be rectangular or bulbous, spanning the width of the stone and tapering near the top. Type D2 finials are generally more elaborate than D1, encompassing more tiers, and sometimes including more extensive ornamentation (S1 Fig. 47).

D2 upper body. Type D2 stones do not present a distinct upper body section.

D2 mid body. The mid body takes the form of a trefoil frieze wrapping around each corner. The central element of the frieze pattern may be either upward or downward facing – in the latter case the general aspect then becomes something perhaps more generally recalling a heart shape. Some D2 stones present a mid body section ornamented with a trefoil frieze with leaves wrapping around each corner (S1 Fig. 48).

D2 lower body. The lower bodies combine multi-lobed vegetal ornamentation with knotwork chains and floral or vegetal designs across a range similar to that described for D1 above. Inscriptions, where present, tend to appear on the wider front and back sides of the stone, while vegetal or floral motifs adorn the narrower sides of the stone. Symmetrical floral patterns with a knotted chain, however, tend to be placed on the wider front and back faces where no textual inscription is present (S1 Fig. 49).

D2 base. The typical base comprises a thick, ornamented ledge, demarcating the ground level between the ornamented faces of the stone and its rough-hewn subterranean anchor.

Spatial distribution

We have identified clear spatial patterns in the distribution of the plang-pleng stones (). Nearly all Type A stones are located on the Lamreh headland to the far eastern extent of our survey zone – an area we have previously demonstrated was the centre of the Lamri polity (Daly et al. Citation2019a; Daly et al. Citation2019b). Five sub-type A1 stones are, however, clustered together in a cemetery at Gampong Pande, over 30 km to the west of Lamreh. The spatial distribution of the A1 stones in Gampong Pande suggests some sort of connection between that site and Lamri. Guillot and Kalus (Citation2008: 329 – TK I/01) have also published the inscriptions on a number of gravestones that we would classify as Type A from Gampong Pande and the Tuan di Kandang Cemetery in Banda Aceh.

Figure 8. The distribution of Type A stones. The map inset on the lower right is an elevated headland in Lamreh village, which can be identified with the historic trading site of Lamri in the 15th century

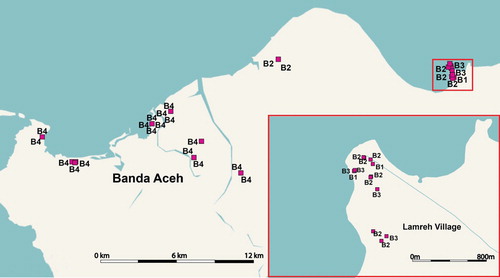

Figure 9. The distribution of Type B stones. Almost all B1 – 3 stones are located on the Lamreh headland, whereas all the B4 stones are distributed in clusters across the western half of our survey area.

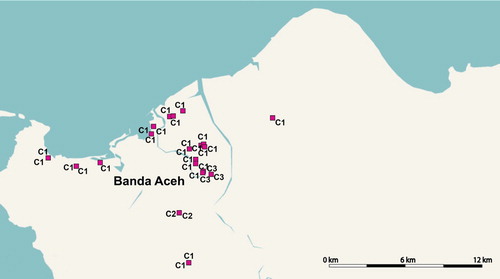

Figure 10. The distribution of Type C stones. All Type C stones are distributed in clusters across the western half of our survey area. None were found at Lamreh.

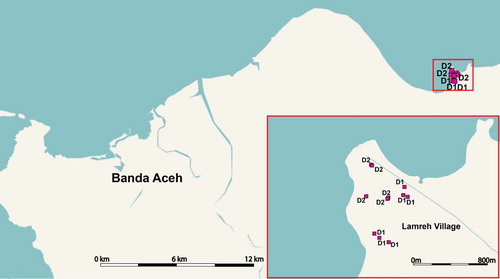

Figure 11. The distribution of Type D stones, all of which that were documented in our survey are located at Lamreh.

Type B stones are more widely distributed across our survey area, but with a clear spatial differentiation between the sub-types. Almost all B1, B2 and B3 stones are found at Lamri, with the exception two B2 graves recorded in Lam Ujong. This suggests that these sub-types share a similar cultural context with the Type A stones which are also centred on Lamri. Conversely, all B4 stones are located in eight clusters across the western end of our survey area, and there are no B4 stones present at Lamri. While clearly the Type B4 stones are broadly connected to the plang-pleng tradition centred on the Lamri headland, it seems that a distinct sub-type was developed for local use by inhabitants of a range of lowland settlements along the coast stretching towards the west.

All the Type C stones are located in clusters along the banks of the lower reaches of the Aceh river. C1 stones are found at 22 different sites. In contrast all C2 plang-pleng are located in one cemetery in Lam Blang Trieng village, and all the C3 stones are similarly found in a single cemetery in the village of Miruek. Notable here is the fact that no Type C stones have been documented on the Lamreh headland, suggesting that Type C gravestones were only used by inhabitants of what seems to be a number of dispersed lowland settlements on the western side of our study area. Here again, stylistic differences across our typology map clearly onto a distinct spatial distribution.

Finally, all stones documented by this survey that we would classify as Type D were found at Lamreh. We did not document any Type D stones in the western side of our study area. However, Kalus and Guillot have published a number of stones that might be situated within Type D in our typology, including fragmentary examples from Lamreh, one along the coast towards the east at Lubhok Bay (Guillot and Kalus Citation2008: 345–346 [KL 05]), and another at Gampong Pande on the western side of our study zone (Guillot and Kalus Citation2008: 332 [TK I/05], dated to 1483–84). We were not, however, able to locate and verify the latter during the course of our survey work. Further afield, down the Sumatran coast of the Straits of Melaka at Pasai is an apparently unique pair of plang-pleng with some features associated here with Type D that date to 1415 (Guillot and Kalus Citation2008: 164–165 [KK21].

Epigraphy

Not all plang-pleng gravestones carry inscriptions, but those that do tend to have them arranged and presented in a distinct set of ways. This includes integrated panels of calligraphy set in distinctly framed horizontal registers as well as calligraphic medallions. The texts presented on plang-pleng are almost invariably rendered in relief, rather than incised. Calligraphy tends to be placed in panels on the lower body sections with the exception of a sole example of a Type D plang-pleng where an inscription also appears in relief across the upper body section (AB-LRH-53-GS1).Footnote13 The dominant calligraphic style of plang-pleng inscriptions is cursive, but not presented in a way that maps neatly on to any single classical style of Arabic calligraphy as defined in standard treatments of the subject. All this clearly distinguishes plang-pleng inscriptions from those found on contemporary gravestones from Pasai further down the east coast of Sumatra, as well as from those of the batu Aceh tradition that arose later across much of the area covered by our survey.

Our survey has, however, also recorded examples of what might be viewed as a transitional form of plang-pleng that incorporate a number of stylistic features that are more widely recognisable as characteristic of batu Aceh. These stones (Sub-type C3) feature both the elaborate multi-tiered bases and ornamental motifs, as well as the distinct framing and calligraphic aesthetic common on batu Aceh. In a small number of cases this extends to the presentation of pseudo-calligraphy.

The language of the inscriptions is almost exclusively Arabic, with only a few instances of Malay words in evidence. The vast majority of legible inscriptions comprised verses from the Qurʾan, Hadith, and other Islamic religious formulae – with the shahada being particularly common. In some cases, these reflect patterns of religious text found on Muslim funerary markers across the broader Muslim world during this period. A smaller subset of inscriptions also contains information on the deceased – including names and death dates, which we have used here to establish the chronological range of various sub-types. A comprehensive study of the epigraphy of plang-pleng is beyond the scope of this article, but detail photographs of calligraphic panels on all stones documented by our survey have been made open-access available online for any interested scholars to examine.Footnote14

Chronology

All dated plang-pleng stones documented in our survey area date to the 15th century. Date ranges have been determined by a combination of reading the epigraphy of stones documented in the course of our field survey, and inscriptions published previously by Kalus and Guillot (see ). Dated examples of Type A plang-pleng stones range from 1406 to the 1470s,Footnote15 Type B from 1437-1460, and Type C stones from later in the fifteenth century (1441-1483). The stylistic typology we have developed here coincides with a fairly clear date range for each type. Moreover, the periodisation also seems to align with distinct patterns of spatial distribution. Type A presents the earliest date range, and appear almost exclusively on the Lamreh headland. The earliest dated Type B is from Kuta Lubhok just below the Lamreh headland, while later dated examples come from further west around present-day Banda Aceh and further afield at Lamno/Daya. Early Type C plang-pleng have been documented by Guillot and Kalus at the Tuan di Kandang Cemetery in Banda Aceh, while the latest comes from the area of Kuta Alam, which is identified as part of the realm of Lamri in local textual traditions narrating the rise of the Aceh sultanate.Footnote16 Type D plang-pleng not only present the most diverse range in terms of stylistic variations, but also the most widely distributed spatially. Unlike the other three types, then, Type D is a more diffuse category than a reflection of a uniform stylistic tradition, and depending how far one might extend this, the date range could also vary considerably across a ‘long’ 15th century.Footnote17

Table 2. Dated examples of plang-pleng, by type.

Discussion

Our documentation and analysis present a distinctive set of Muslim gravestones along the Aceh coast that developed a range of stylistic variations rooted in specific locations over the course of the 15th century. The basic obelisk or rectangular pillar form of these objects clearly distinguish plang-pleng from nearly every other known type of Islamic grave marker in Southeast Asia, which tend to take the form of either wider slabs, or rounded / polygon columns, as for example in the batu Aceh tradition that developed along this same stretch of the Sumatran coast immediately after the eclipse of the plang-pleng tradition at the turn of the 16th century.

Our survey has revealed clear correlations between stylistic variants and their relative chronologies and patterns of spatial distribution. The prevalence of many of the earliest dated examples (Types A, B1, B2, and B3, as well of some Type D) on the Lamreh headland establishes that site as the centre of the plang-pleng tradition.Footnote18 This strongly suggests the plang-pleng form was a distinct cultural product of Lamri – possibly initially representing high status members of the community. The location of five A1 plang-pleng in a tight cluster at the lowland site of Gampong Pande suggests a settlement with some form of shared cultural aesthetic, and perhaps political connection, with Lamri.

Though textual sources in Arabic, Chinese, and other languages point to Lamri’s place in trans-regional trade for more than a millennium, plang-pleng are known only from around the turn of the 15th century. This is, notably, after the coastal regions of northern Sumatra had been devastated by a massive tsunami in 1394. After that the Lamreh headland remained the most prosperous surviving settlement in the area particularly over the first half of the 15th century (Daly et al. Citation2019a: 11679–11686). The Type A1 and D plang-pleng erected on the headland over the early decades of the 15th century apparently served as models for emulation as lower lying areas of the coast stretching to the west of the Lamreh headland recovered and were resettled.

The considerable variations across individual stones within both A1 and D may, furthermore serve as indicators of a nascent tradition that developed more standardisation in other sub-types as they emerged over the course of the 15th century. Types B4 and C plang-pleng exhibit considerably less individual variation. These types fall within a somewhat later date range and are distributed across a larger number of cemeteries in the western half of our survey area, with a notable pattern of C1 stones located in cemeteries along the meanders of the Aceh river. We did not, however, find any examples of these types on the Lamreh headland, linking these manifestations of the plang-pleng tradition to low lying settlements around the Aceh river that fell within the broader cultural orbit of the trading settlement that flourished at Lamri during the 15th century.

In those areas stretching along the coast towards the west, the plang-pleng form appears to have been both adopted and adapted in ways that contributed to the emergence of an expanding range of stylistic variations. The Type C stones documented along that stretch present the latest date range of plang-pleng, mostly spanning the second half of the 15th century. They also exhibit a number of distinctive features that came to characterise the batu Aceh tradition of Muslim gravestones that developed following the rise of the Aceh sultanate. We see this, for example, in the prominent elaboration of multi-tiered bases, and the appearance of a new way to present Arabic script calligraphy. By the turn of the 16th century the area where these stones were being erected along the banks of the Aceh river rose to prominence as home to the Aceh sultanate. With this, the earlier centre of plang-pleng production at Lamri was eclipsed in the economic, political and cultural spheres to the point that the headland site was abandoned (Daly et al. Citation2019b).

Guillot and Kalus (Citation2008: 131) have suggested that the range of inscribed plang-pleng may be seen as a reflection of the territory commanded by Lamri during the 15th century, while noting that a number of such stones found in the environs of present-day Banda Aceh are located in cemeteries that continued to be used during the sultanate period. At the same time, they contend that the pair of plang-pleng that they transcribed from Lamno (in what was earlier the polity of Daya) indicates that this relatively distant settlement was also ‘partie intégrante de royaume de Lamuri’. This, however, may be something of a stretch, as the adoption of cultural forms across regional settlements does not necessarily imply the recognition of state sovereignty. Rather we may have here a pattern of social organisation distinct from that of both Pasai further down the Straits of Melaka during that period, or the Aceh sultanate over the century that followed. Such a model would seem to fit well with an important observation the same authors have also made based upon their readings of inscriptions on plang-pleng stones. In that sample, the title ‘raja’ appears five times, as opposed to only two instances where the title ‘sultan’ is used. This is despite the fact that by the time that the plang-pleng tradition emerged at Lamri, the title of sultan had already been in common use at Pasai for more than a century, and later came to define the powerful polity that arose in Aceh at the turn of the 16th century. Though this is a small sample to base any generalisation upon, Guillot and Kalus (Citation2008: 132) have postulated that, ‘this apparent incongruity may mean that the rulers of Lamri did not bear the title of Sultan but that of raja … ’.

It is important to consider here what the title ‘raja’ may have actually meant in local contexts. Rather than assuming that both titles were intended to signal ‘king’ in the same way that we might imagine, it may actually be that the use of raja in plang-pleng inscriptions was not necessarily a simple substitute to that of sultan – but rather indicates a different form of social organisation and local models of leadership. Indeed, the particularly local use of the title raja at Lamri in the 15th century appears to be reflected in a chronicle of the Ming voyages of Zheng He’s fleets (Ying yai sheng lan) which refers to the local usage of the title raja there in a somewhat mocking tone:

Each man styles himself a king; if you ask his name, he says in reply ‘A-ku la-ch’a,’ [Aku raja] … If you ask the next man, he says ‘A-ku la-ch’a’ … ; it is most laughable.

We may, however, conceive of the social and political arrangements that framed their production. The materiality of surviving plang-pleng presents clear evidence for a unique aesthetic of Muslim cultural expression in 15th-century Southeast Asia. The objects that we have documented here reflect a tradition of funerary art characterised by gravestones in a distinctive obelisk/pillar form and with a very specific range of stylistic features. As we have outlined here, all sub-types of plang-pleng exhibit ornamentation drawing from an overlapping set of motifs, ranging from asymmetrical vegetal designs, knotwork, medallions, and a number of distinctive floral and geometric elements. Within this shared visual vocabulary some elements are particularly pronounced, such as the four-petalled flower which presents a form on these Sumatran stone that seems to mirror its usage on medieval Muslim monuments of south India (see e.g. ), and which became near ubiquitous in wood carving traditions in many parts of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula.

Perhaps most striking though is the prominence of trefoil motifs, which sometimes appear inverted to take the form of pendants that can be stylised to the point that they appear as heart shapes. This instantly recognisable motif is found across a strikingly broad range of early Muslim monuments in Southeast Asia. It is visible, for example, at sites associated with the Wali Songo and the Sendang Duwur mosque on the north Java coast (). In many places, this floral motif is integrated into symmetrical S-curlicue framing elements (e.g. ) – a combination that, as we have noted above, is also common on plang-pleng. In such usage, both the pendant trefoil and the space framed by the S-shape curves presents the shape of a stylised heart.

Figure 12. The heart-shape trefoil motif in the Masjid Sendang Duwur cemetery, East Java. Photo by R. Michael Feener, 2015.

Figure 13. S-curlicue framing a heart-shape motif on a gravestone in the complex of Maulana Ibrahim, East Java. Photo by R. Michael Feener, 2015.

The general shape of this peculiar motif may for some recollect that of the Buddhist triratna, reflecting a strong connection with Indian aesthetic traditions. Similar motifs found on other examples of material culture from Muslim Southeast Asia have also been characterised by some as depicting lotus.Footnote20 While, as noted above, more directly identifiable lotus motifs do appear in the ornamentation of some plang-pleng stones, those should not be conflated with what we have described here under the broader rubric of trefoils.Footnote21 We should begin to wean ourself off the working assumption that any floral motif found on a bit of old stone in Southeast Asia must somehow indicate ancient Indic associations.Footnote22 The dominant tendency of ascribing pre-Islamic religious symbolism so widely to such elements may in fact obscure other, more proximate and productive lines of interpretation.

The ubiquity of trefoil motifs on plang-pleng stones, we argue, presents something more complicated than a simple ‘survival’ of a Buddhist or Hindu element in the emergent Muslim cultures of Southeast Asia – as indeed it may have actually been associated more with Islam by the populations of the archipelago in the 15th century than it was with Buddhism. Uka Tjandrasasmita (Citation1975) argued that the heart-shape leaf motif does not appear to have been known in the region before the coming of Islam. More recently, Hadi Sidomulyo (Citation2012: 114) has remarked on the presence of the ‘heart-shape leaves’ in a similar trefoil form at a number of late Majapahit sites on the slopes of Mount Penanggungan (), where they may reflect a new cultural style that emerged with the transition from Hindu-Buddhist traditions to Islam over the 15th and 16th centuries. Closer to the home of the plang-pleng tradition, this motif appears frequently on ornamental bands along the lower registers of many batu Aceh type grave stones, as well as on the ten corners of the base of the Gunongan () in the former garden precinct of the palace of the Aceh sultanate. This last example in particular evidences the continuing use over later centuries of this motif beyond the plang-pleng tradition along the north coast of Aceh on another monument that embodies elements of Indic cosmology incorporated within new Islamicised forms of material culture.Footnote23

Figure 14. The heart-shape trefoil motif on fragmentary ruins at Mount Penanggungan, East Java. Photo by R. Michael Feener, 2015.

Figure 15. The heart-shape motif on the base of the Gunongan, Banda Aceh. Photo by R. Michael Feener, 2008.

While there may be nothing intrinsically ‘Islamic’ about this motif, its ubiquity on early Muslim monuments in Southeast Asia suggests that variations of this trefoil or heart shape were associated with the spread of Islam among early communities of believers in the region. It may also have held some trans-regional associations, as we find occurrences of the motif at Muslim sites elsewhere along the shores of the Indian Ocean, such as in southern India on both the Malabar and Coromandel coasts (, ).

Figure 16 The heart-shape leaf motif on the lintel of a Sufi shrine in Kozikhode, Kerala, India. Photo by R. Michael Feener, 2015.

Figure 17. The heart-shape leaf motif on an ornamented panel in the Jāmiʿ al-Kabīr / Khuṭba Parriapaḷḷi (mosque), Kayalpattinam, Tamil Nadu, India. Photo by R. Michael Feener, 2015.

Photographs of 15th-century Muslim gravestones from southern India displaying this same motif have been previously published by Mehrdad Shokoohy (Citation2003: 276). Some of these same stones, moreover, also prominently feature S-curlicues as framing motifs, particularly for the upper portions. Most often on gravestones, these surround relatively side spaces, and the bottom of these framing lines does not meet at the bottom (Shokoohy Citation2003: 279–282). Some of the oldest mosques in Tamil Nadu, however, are ornamented with forms of this motif that also frame stylised hearts (e.g. ). This, it must be noted, is not to argue for a straightforward, single vector transfer of the motif from southern India to Southeast Asia. Rather, what we may be seeing here is the interactive formation of new vernacular styles of Islamic ornament across new Muslim communities linked through maritime circulations of commerce and culture in the late medieval period.

Figure 18 S-curlicues framing a heart adorning the Jumaʿ Mosque at Kilakirai, Tamil Nadu, India. Photo by R. Michael Feener, 2015.

Tamil engagement with trans-regional trade networks and the cultural circulations they facilitated has long been noted in the history and archaeology of Sumatra (Guy Citation2011: 248). That this facilitated the transfer of forms of Muslim gravestones is clear from one particularly striking example from Barus. The oldest dated Arabic inscription there appears on a stone (PNG2) unique among all others documented by the EFEO/NRCA team, featuring a prominent example of the same motif in the photo above from a medieval mosque in Tamil Nadu (). The epitaph dates this stone to 1350, and inscribed (as is common in southern India), rather than presented in relief as in the case of plang-pleng (Perret et al. Citation2009b: 487). While presenting an early example of a motif that was featured prominently on plang-pleng half a century later in another part of Sumatra, this solitary example was clearly not a ‘prototype’ for the distinctive style of Muslim gravestone that developed at Lamri.Footnote24

Reporting on other aspects of their extensive archaeological investigations at Barus, Perret and his colleagues write that most of the earthenwares found at Lobu Tua show ‘strong similarities regarding shapes and decorations with pottery found in south India and Sri Lanka’. At the same time, however, they assert that these particular pieces are less homogeneous and suffer from an inferior quality of firing when compared to examples of pottery in a similar style found at South Asian sites (Perret et al. Citation2009a: 167). Ed McKinnon (Citation2011: 144) has also noted similar examples of ‘Indianised’ redware at both the Kota Cina site on the opposite coast of northern Sumatra, as well at Ujong Batée Kapal on the Lamreh headland.

McKinnon (Citation2011: 147) conducted some of the earliest explorations of the headland site where we have now identified as the centre of the 15th-century plang-pleng tradition, calling attention to the ways in which both these gravestones and earthenware sherds recovered there point towards important connections between Lamreh and the Tamil Nadu region of southern India. The strength of these cultural connections is further corroborated by other archaeological evidence on the headland, including fragments of Indian glass bangles and sections of limestone plaster flooring (McKinnon Citation2010).

These material traces of commercial and cultural connections at Lamreh do not, however, necessarily establish that the community that produced plang-pleng to mark Muslim burials was exclusively or even primarily comprised overseas migrants. Sojourning merchants associated with Chola guilds were most likely present on this stretch of the Aceh coast prior to the rise of the sultanate, as evidenced by the Tamil inscription from Neusu (Subbrayalu Citation2009). This may have facilitated the emergence of new communities along the coast, born out of their unions with local women and the subsequent expansion of these families in positions of commercial and cultural prominence.Footnote25 There is no evidence, however, that they transplanted imitations of the same style of gravestones found in early Muslim cemeteries back home across the Bay of Bengal to northern Sumatra. For while the circulation of a distinct set of ornamental motifs does present evidence of some shared elements of visual culture across the networks of Islamic communities in medieval maritime southern Asia, plang-pleng present an altogether distinct type of object from the Muslim gravestones known in Tamil Nadu.

The ubiquity of ornamental motifs common in southern India on plang-pleng stones clearly reveals the significant role that Muslims from that region played within the complex and still only partially understood historical dynamics of Islamisation in Southeast Asia. Their influence, however did not take the form of simply transplanting a style of Muslim gravestone from Tamil Nadu to 15th-century Sumatra (). Rather, we find various motifs from the visual language of Islam in south India selectively drawn upon by the emerging community on the Lamreh headland to produce something altogether new. This is immediately evident upon comparison of the basic slab form of the latter, presenting a profile strikingly different from the obelisk shape characteristic of plang-pleng. Also, rather unlike the pyramidal or tapered finials found on most plang-pleng, traditional Muslim gravestones in Tamil Nadu are commonly capped with what appear to be horizontal cross-sections of an onion dome. Furthermore, whereas the epigraphy on plang-pleng is invariably presented in relief, texts tend to be inscribed in Muslim funerary markers of southern India.

Figure 19. Muslim gravestones at Kayalpattinam, Tamil Nadu, India. Photo by R. Michael Feener, 2015.

The sole known case of Arabic text being inscribed into a stone from nearby the area covered by our survey is on a fragment that can only inconclusively be considered a Type D, as the sections above the calligraphic panel have been lost. Some Type D stones present footprints that are more rectangular than the squares of other types of plang-pleng obelisks. This innovation may reflect early experiments at mediating diverse influences into the creation of a distinctive local form of cultural expression in 15th-century Sumatra, as local Muslim communities were established and came to identify themselves in relation to a diverse and expanding world of co-religionists.

Conclusion

The extended set of plang-pleng stones documented by our survey expands the material available for the consideration of the historical significance of these objects well beyond the handful that had previously been mined solely for the semantic content of their inscriptions. In the process, it allows us to track the rise, development and demise of a distinct and heretofore, unexplored tradition of artistic production reflecting one of the earliest examples we have of the vernacularisation of Islamic civilisation in Southeast Asia.

The choice of the term vernacularisation here is deliberate, drawing on the understandings of this process that have been stimulatingly developed by Sheldon Pollock (Citation2009) in connection with the proliferation of literary traditions in interaction within what he has described as the ‘Sanskrit cosmopolis’. This presents a view of the vernacular that is not a mere popularisation of a high tradition for local consumption, but rather as a reflection of cultural choices opting to create new forms of expression that bring local production into a conscious engagement with the broader ‘cosmopolitan’ registers. Extending the basic dynamics of this model beyond the sphere of literature to other forms of cultural expression, we might view the development of the plang-pleng form in an analogous way.

In this case combinations of formal characteristics and ornamentation drawing selectively upon motifs introduced through trans-regional circulations and on locally established repertoires were brought together to create objects that participated in an explicitly and recognisably Islamic way with a universalist tradition during an important phase of its expansion across the Indian Ocean world. Plang-pleng thus not only mark the acceptance of a way of memorialising the dead, but also a new way of life on the Southeast Asian frontier of an expanding world of Islam in the 15th century. They reflect then not so much a local ‘accommodation’ of Islam as a ‘foreign’ tradition, but rather an active project of local initiative for a form of local production that signalled the community’s connection to the wider Islamic world.

The trans-oceanic imagination and religious valences reflected in the production of plang-pleng continue to speak in stone through the text inscribed on a sub-type A2 example found on the Lamreh headland (AB-LRH-10-GS13):

والبحر عميق // بلا سفن فكيف // تعبرون

‘The ocean is deep. Without vessels how can it be crossed?’

Wa’l-baḥr ʿamīq // bi-lā sufun fa-kayf // taʿburūna

The relatively tight constraints on both the geographic range and the chronology of dated plang-pleng presents us with a striking case of the emergence of a distinctive localised form of Muslim visual and material culture during a pivotal phase in the history of Islamisation in Southeast Asia. Situating the emergence and eclipse of the 15th-century plang-pleng form in relation to other, better known regional styles, such as those of Pasai and the batu Aceh tradition highlights the remarkable diversity of vernacular Muslim cultural formations that were taking shape in the region at the time. The short-lived but distinctive plang-pleng tradition reflects the aesthetic choices of a heretofore under-studied early Muslim community as it came to identify itself as Muslim over a pivotal period of history, during which the Indonesian archipelago was becoming increasingly integrated into the expanding religious and economic networks of a maritime world of Islam.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.7 MB)Acknowledgements

The survey work upon which this article was written was conducted by the Aceh Geohazards Project, a collaborative effort by the Earth Observatory of Singapore and the International Centre for Aceh and Indian Ocean Studies (ICAIOS) to study the impacts of natural hazards upon past communities along the Aceh coast. Assembling this data set would not have been possible without the efforts of the Field Survey Team: M. Irawani (project manager); Hayatullah (field team leader); D. Satria, S. Wahyuni, M. Zahara, C. Salfiana, Fitriani, J. Taran, A. Wahid, A. Zaki, A. Munandar, Ariyusnanda, A. Husni, A. Gapi, A. Mujiburrahmi, and M. Ikhsanuddin (heritage survey team); Jihan, P. Arafat, Muksalmina, A. Yamani, S. Novita, M. Syafruddin, and R. Zahara (artifact and data processing); and Safrida, C. Dian, H. Adnin, and Evan (administrative and logistical support). We would also like to especially thank Professor E. Srimulyani, Dr Arfiansyah, Dr S. Ihsan, Dr A. Widyanto, Dr S. Mahdi, Dr T. Zulfikar, and Dr Cut Dewi for their advice and support. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore, and the Singapore Ministry of Education under the Research Centres of Excellence initiative. This work comprised Earth Observatory of Singapore contribution no. 338.