ABSTRACT

The catalogue to Rome-based Palestinian artist Emily Jacir’s Europa exhibition of 2015 includes a short excerpt from Franco Cassano’s Southern Thought entitled “Thinking on Foot”. This article maps key elements of Cassano’s essay, namely the focus on “Mediterranean” values of slowness, contemplation, and conviviality onto readings of Italy-based works by Emily Jacir, Diana Matar and Hisham Matar, all of which provide capacious ways to rethink the idea of pilgrimage. Reflecting on the sites, sights and routes that form the basis of these works, the article shows how they represent pilgrimage as a slow form of contemporary cultural mobility, one concerned with deep contemplation of place as a response to experiences of loss, displacement and exile. Sacred journeying is experienced here through instances of micro-travel, such as walking, standing and looking, and personal transformation is charted through moments of slow thought and memory-work, as captured in multiple, mobile artistic forms.

We must go slow like an old country train carrying peasant women dressed in black, like those who go on foot and see the world magically opening ahead, because going on foot is like leafing through a book, while running is like looking at its cover. (Cassano Citation2012, 9)

This article will map key elements of Cassano’s essay, namely his focus on the “Mediterranean” values of slowness, contemplation and conviviality, onto a comparative reading of works by three artists and writers who share similar engagements with Italian places: Emily Jacir (stazione; Via Crucis), the US photographer Diana Matar (Evidence, Citation2014) and her husband, Libyan novelist Hisham Matar (A Month in Siena, Citation2019). Reflecting on the sites, sights and routes that form the basis of these works, I show how they can be seen as pilgrimages, if we understand pilgrimage to be a slow form of contemporary cultural mobility, one concerned with a deep contemplation of place. Seen in this light, these pilgrimages become “opportunities to reflect upon, re-embody, sometimes even retrospectively transform, past journeys”: “in the process (turning) history into both myth and ritual” (Coleman and Eade Citation2004, 18). Sacred journeying is experienced here through instances of micro-travel, such as walking, standing and looking (up or down). Personal transformation is charted through moments of slow thought and memory-work, as captured in multiple, mobile artistic forms. Additionally, this article uses a framework informed by the same values of slowness, contemplation and conviviality in order to provide a meta-reflection on the experience of carrying out research in the distorted timespace of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Slowing down

There is more life in walking ten kilometres on foot than in a transoceanic route that drowns you in the loneliness of its planning, a gluttony that cannot be digested. (Cassano Citation2012, 10)

Again, I think walking, and perhaps “sacred” walking in particular, might offer one model of doing this. Tim Ingold and Jo Lee Vergunst show how walking is crucial to fieldwork practices: researchers often have to travel to where they want to carry out research, and they then continue to move around once there, visiting different places to meet and interview people, witness particular activities, or see significant sites. But these forms of travel often remain buried in the annotations of fieldnotes, rarely making it into published outcomes. There is a “separation of what is being purposefully done (arriving somewhere, say) from how it is done (by getting there, step by step, along a path)” (Ingold and Lee Vergunst Citation2008, xi). In sacred walking there is, as Coleman and Eade remark, a similar contrast between “poses of static devotion and the movement needed to reach places of pilgrimage” (Citation2004, 1). The proposition I am making here is this: let us try to retain something of the tactile, sensory, embodied experience of doing research, the “feet-first engagement with the world” (Ingold and Lee Vergunst Citation2008, 3) that our preparatory work requires of us within our published outputs. But how to do this in a pandemic when most ‘horizontal’ travel has ceased? Many commentators have famously considered walking to be a narrative form in itself (Mauss [Citation1934] Citation1973; Bourdieu Citation1977; de Certeau Citation1984; Solnit Citation2001), a form that comprises our own mapping and imprinting of a bodily rhythm or a narrative on the surroundings. But Ingold and Lee Vergunst urge us to reverse this proposition, to see “thinking and feeling as ways of walking” (Citation2008, 2). So here I will plot out stations of a pilgrimage that will be paper-based, think of obstacles to travel as resources for the mind to stretch out its imaginative faculties, and use thought patterns to pace out and map the stops on a research journey. This article shares my own experience of a vertical research journey as anti-linear, non-teleological, and resolutely slow-paced. It resonates with Frédéric Gros’ description of slow walking as “cleaving perfectly to time, so closely that the seconds fall one by one, drop by drop […] This stretching of time deepens space” (Citation2014, 37). In my framing of this article, I will explore the spatial recesses of Cassano’s Mediterranean as an archive of “redeemable” and “subaltern” values such as slowness, contemplation and conviviality; and of traditions and heritage that privilege exchange, hybridisation and plurality (Bouchard and Ferme Citation2013, 81). In order to embark on this slow, vertical journey, I turn first to the maps we might find that we need to guide us.

Maps

Every frontier carries with it, like a shadow, its transgression, something that goes against the prohibitions of nations. (Cassano Citation2012, 44)

This reflection on the bent and deviated time of folded maps recalls our contemporary experiences of what has been termed pandemic time: where the temporal arc of each day can feel loose and roomy, as if it is passing exquisitely (or dreadfully) slowly. Yet retrospectively time appears to be moving more quickly than usual, because of the repetitive nature of our activities, and as we look forward, we reckon with an unusually “open-ended, uncertain future” (Pong Citation2020). There are few anchors to mark out the passing of past, present and future time, aligning with Hisham Matar’s description of his time spent in Siena in 2015, where “time folds together and collapses like a concertina of days made of the same fabric” (Citation2019, 26). This altered perception of time is exacerbated by the sense of both belatedness and temporal syncopation that we experience being plotted out over the infection curves replicated daily in data visualisation sets (Pong Citation2020). Yet Pong also reminds us that pandemic time will be experienced differently depending on one’s circumstances and location, since “we occupy dissonant, even if interconnected rhythms” (Citation2020). For most academics, daily reading and writing now take place in makeshift home offices, urging us to pay attention to the folds of our own bodies as we research. We might follow Gros’ exhortation for us to think of what we write as an “expression of physiology”, where the felt presence of a seated writer (“doubled up, stopped, shrivelled in on itself”) makes the narrative indigestible, but a book written by someone on the move acquires a sense of the walking body as “unfolded and tensed like a bow: opened to wide spaces like a flower to the sun, exposed torso, tensed legs, lean arms” (Citation2014, 19).

Hisham Matar’s A Month in Siena is a walking book, a map folded into a hundred pages. Matar notes that Siena was the first Italian city to restrict access to its streets by motorised vehicles, back in the 1960s. The author’s explorations are therefore resolutely pedestrian, as he winds back and forth through the “folds of the city” (Citation2019, 36) on foot. When darkness falls, the narrow, cobbled alleys and tall medieval buildings give him the sense of “entering a living organism. With every step I pressed deeper into it, and, as if in response, it made room. I was inside a place both known and deeply familiar” (Citation2019, 9). Each step marks a physical contact: a corporeal impression made by the foot rather than a writerly inscription by the hand. Tim Ingold reminds us that footprints exert a physical pressure on the ground below them, and as such the impressions they leave are also temporary: the wet slick of a shoe’s tread on asphalt, indents in mud, snow or grass that will be washed away by rain or erased by other marks of subsequent passage (Citation2010, 129). But Matar wants more than to impress himself onto the city, he wants his contact with the city to have an analogous physical effect on him: “like a stonemason grinding his chisel on a rough slab”, he wants to “sharpen (him)self against the city” (Citation2019, 49). This mutual bodily “brushing up” (see Dinshaw Citation1999) that leaves both city and walker changed by the encounter reminds us that the ground we walk upon “is not a white page, but an intricate design of historical and geographical sedimentation’ on which the pedestrian adds another layer to those already present” (Careri Citation2002, 150). Matar’s impressionistic, palimpsestic walking is the opposite of the drive for colonial conquest inscribed in maps that erroneously and conveniently assumed previously blank spaces on which the author “can exercise his own will” (see De Certeau Citation1984, 134).

Siena is no such passive canvas to Matar’s wanderings. The city “engineers” conversations (Citation2019, 13) and engineers itself into conversations – to the author, it seems to be the one “determining the pace and direction of my walks” (Citation2019, 50). As a walled and strangely self-sufficient organism, it affords no view of the horizon, encapsulating its own universe. “My compass could only be guided by it, by its twists and turns, its manoeuvres and decisions, by its tastes and purposes. Siena is its own North Star” (Matar Citation2019, 50). Matar decides to test out its frontiers, by walking each day to one of the city gates and once he can no longer see the city, to return to it, and in so doing to experience the “transformative possibility of crossing a threshold” (Citation2019, 10). Cassano terms Ulysses the enduring archetype of the “Mediterranean man” precisely because of his desire both to wander and explore, whilst at the same time still desiring to return home (Citation2012, 36). This dance with limits leads to self-definition through the encounter with the other. “On the frontier, on the limit, each of us ends and is defined, acquires one’s shape, accepts to be limited by something else that is obviously also limited by us” (Cassano Citation2012, 42). The definition that borders provide is lost in infinite views of the horizon, triggering a sense of claustrophobia that can be countered by practices of microspection, compartmentalisation and “cordoning off” (Matar Citation2019, 51). And so the desire to be lost within the micro-folds of the city returns. The map Matar once spread out on a small table at home to consult is left at home when he walks his circuitous paths of departure and return (Citation2019, 50). The written account of his walks gathered up into the pages of the book functions as his map, a map gifted to his reader, where we find tucked in the folds and margins the traces of other Mediterranean pasts – in Jordan, Libya, and elsewhere.

Stumbling

The debris accumulates near the frontier. (Cassano Citation2012, 45)

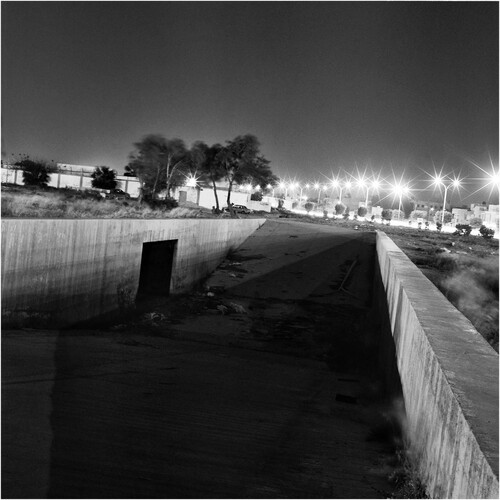

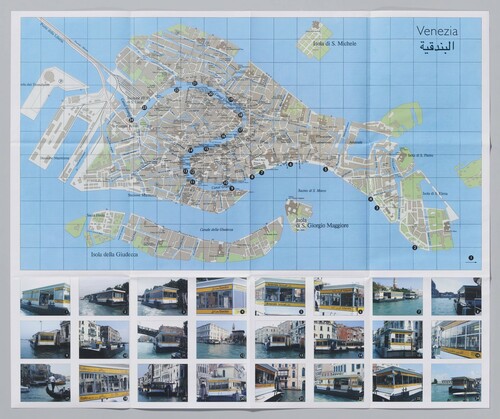

Figure 1. Emily Jacir, stazione 2008-2009. Public intervention on Line 1 vaporetto stops, Venice, Italy. Commissioned for Palestine c/o Venice, collateral event of the 53rd International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia © Emily Jacir, photograph by Michael Agee.

I mentioned above that stazione was never exhibited at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009 as planned. In fact, it was censored. No full explanation for its removal from the Biennale programme was ever given to Jacir by the organisers, the water bus company or the municipality of Venice; there were only “vague allusions” made to “political pressure from an outside source, and equally oblique references to the Gaza bombing” (Fisher Citation2009, 798). Shifting tack with excuses and silences shows how things are stopped, when what stops movement moves itself. As Sara Ahmed explains: “When the mechanisms for stopping something are mobile, to witness the movement can mean to miss the mechanism” (Citation2019, 153). The censorship that stazione came up against was a blockage, yet Jacir’s project did not shatter on impact with it – perhaps because the disruption only served to replicate the point of what her work is always trying to show.

The art of Emily Jacir is full of delays, deferrals and disruptions. Her works […] tend to concern moments of rupture, destruction, extreme violence and palpable dispossession. At the heart of her practice is the experience of […] a place being difficult, hard to reach, return to or revive; of a place being impossible to realize as a real place at all. (Wilson-Goldie Citation2015)

Sometimes we ourselves put obstacles in the pathway of progress. Hisham Matar originally decided to visit Siena after finishing his Pulitzer prize-winning book on Libya, The Return (Citation2016). His trip to Italy marked twenty-five years of fascination with the Sienese school of art, which he developed as a passionate distraction in the aftermath of his father’s disappearance and presumed murder by Libyan government in 1990. Depleted by the emotional and intellectual labour required by this previous writing project, he decided to enact a pilgrimage to Siena: a spiritual quest that incorporated past and future journeys of both loss and growth within it. “I had come to grieve alone, to consider the new terrain and to work out how I might continue from here” (Matar Citation2019, 67). The object of the quest here is an “instrument of insight” (Basu Citation2004, 162). But Matar is suspicious of his own desire to see Siena and its art: increasingly so as Siena begins to occupy in his mind “the sort of uneasy reverence the devout might feel towards Mecca or Rome or Jerusalem” (Citation2019, 8). He begins to delay, to procrastinate, to put obstacles in his own path to reaching his destination. He decides to fly to Florence and walk: “I like the idea of small steps covering a long distance and of finally entering the city on foot” (Citation2019, 1). But in a mundane accident, he twists his knee before departing – the sixty odd kilometres south through Tuscan hills now too much for him to contemplate with his injured leg. With no direct flights available due to his “reticence” at booking, he has to change planes in Zurich. Again, an obstacle presents itself, and the plane turns back over the Alps due to a technical fault. In a third attempt, he gets as far as Florence, but the night bus to Siena makes an unscheduled and scary stop to pick up passengers from an earlier bus that has broken down. All the omens are bad. Or are they? They nod to a forced deceleration, an acknowledgment of the physical and logistical efforts demanded by journeying, a rebellion against the seamlessness of fast travel. The trials of the journey require a deeper engagement with the environment, the need for problem-solving skills, and paying close attention, also to fellow passengers and sights glimpsed on the way (echoing Cassano’s reminder that “going slow are the stations in between” [Citation2012, 10]). There is something to be gained in a slow mode of arrival, the satisfaction experienced as fruit of challenges. Slow time is formed of chance encounters, of bumping into things and people, the experience of travelling on “a bus worn out by an upward climb” (Cassano Citation2012, 10).

Obstacles, then, can be productive and meaningful, as they can offer alternative routes as options and chance moments of revelation. Let us take one further step back in time to a different map point: Benghazi, in March 2012, when Hisham is in Libya with his wife, Diana Matar – an episode recounted both in A Month in Siena, and in Diana’s Evidence. The couple go for a walk with their friend at night. Diana walks ahead, unable to hear more than snippets of their conversation because of the strong wind. She walks through the darkness, and stumbles on a patch of uneven earth. “Something cold came rushing through my body” (Matar Citation2014, 87). She had come across a small wall made of cement, about a foot high. An underground bunker, in which prisoners had been kept for years. When discovered after the fall of Benghazi, some were still alive. Although it is no more than a ruin now, Matar comments that “something remains in these places. I wasn’t prepared for that” (Citation2014, 128).

This is, in Caitlin DeSilvey’s words, an example of “storying matter” (Citation2017, 6): where what might seem like an obstacle to the walker’s progress is actually the earthly sedimentation of narrative, its stratification, a sign of resistance taking root. Things tend to accumulate if they are not disturbed from doing so, since “the disarticulation of the object can lead to the articulation of other histories, and other geographies” (DeSilvey Citation2006, 324). And this potential for articulation is more likely in the Mediterranean, “with its sluggishness, with time and space that resist the laws of universal acceleration”: southern obstacles now “become a resource” (Cassano Citation2012, 3). Southern thought means we have the time to slow down and look around, but also to look up, and to look down. We can pause to reflect on detail, and our “perception of the part, rather than the whole, opens up a space that invites speculation and connection” (DeSilvey Citation2017, 187).

Contemplation

Going slow means […] being faithful to our senses, tasting with our body the earth we cross. (Cassano Citation2012, 10)

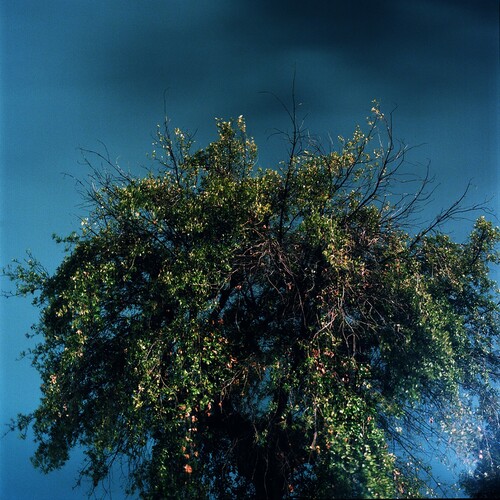

We look up at the Roman witness trees that Diana Matar has photographed – their tangled branches and folded shadows – much as we might look at paintings in churches or galleries. The contemplation they demand combines the reverence one feels towards the trees as art objects (a contemplation that Hisham Matar describes as resembling prayer [Citation2019, 14]) with the peaceful wellbeing that can be gained through looking at nature (where staring at the sea is equivalent to praise [Matar Citation2019, 14]). As living things, the trees also acquire the potential to communicate, or even to commune with the viewer, which is activated through contemplative looking. They “pull (us) back to (our) senses” (Tsing Citation2015, 1), incorporating us into each photographed scene and the history it holds. In their autonomous, uncontrolled life, the trees represent a “gift and a guide”, and they “can catapult us into the curiosity that […] [is] the first requirement of collaborative survival in precarious times” (Tsing Citation2015, 2). One of the most detailed episodes recounted in A Month in Siena also takes place in Rome, during the same trip on which Diana photographed the series of witness trees in Evidence. After visiting the Galleria Borghese to see Caravaggio’s painting of David with the Head of Goliath, they walk down to the city centre from the Borghese park and pause in the gardens of Bernini’s baroque church of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale. The couple lie down on the grass side by side, Diana’s head resting on Hisham’s chest, Hisham lying with his head lower down on the slope than his chest.

I remember getting that odd feeling, a sort of mystery towards my own anatomy, […] that an independent will operated these secret clocks inside of me, that the operations and very texture of my organs and the blood that ran through them belonged to some other order of existence that stood apart from my sense of my self, from my ideas and emotions. “I have such a beautiful perspective,” Diana said suddenly. (Matar Citation2019, 23)

Back in Siena, Hisham lies down once more, alone this time, on the central square of the Campo, having spent some time contemplating Lorenzetti’s frescoes in the Palazzo Pubblico. He lies on the brick tiles, warmed by the sun, and “polished by centuries of pedestrians and horses and carts”, and remembers his late father speaking to him in Italian (Matar Citation2019, 46) – a language he does not speak. His father would find amusement in his son’s inability to understand him, but Hisham remembers feeling floored by the sudden mystery of his father, his foreignness, “how stonily impenetrable his thoughts seemed” (Citation2019, 46). The memory makes Matar reflect on his first forays in the National Gallery in London, which would see him spend his lunch hour in deep contemplation of one picture, and only after a full week of visits had passed would he feel able to move on. What strikes him in his current, supine position is that he was looking for traces of his father in these moments of contemplation, and that although this venture has failed, he has retained his method of slow looking as the most productive and revelatory way of experiencing art.

A picture changes as you look at it and changes in ways that are unexpected. I have discovered that a painting takes time. Now it takes me several months and more often than not a year before I can move on. (Matar Citation2019, 4)

I myself wonder if – rather than replacing sacred practices – some artworks demand that we experience them precisely as if they were part of a pilgrimage. Jacir’s Via Crucis (2014–15) is a permanent installation in the side aisles of the San Raffaele Arcangelo church in Milan, commissioned by artache. Jacir displays a series of Palestinian relics underneath fourteen aluminium tondi that mark alternative stations of the cross (half the stations are marked in Arabic, and half in Italian). This is, in John Lansdowne’s words, “a story told in things” (Citation2016, 4): things that range from a black and white keffiyeh, to barbed wire and spent Israeli artillery shells, to traditional embroidered dress, olive wood and fishing nets, through which Jacir spins a story of Palestinian destruction, loss and diaspora, but also of creativity, craft, resourcefulness and resilience. Following the new stations of Jacir’s cross requires both sides of the devotional art experience to be activated: the circular movement around single objects to form a route with meaning, and the close contemplation of each individual station. The objects speak to the contemporary experience of Palestine but also to that of Lampedusa, where Jacir spent a formative month in 2013. Objects such as the photograph of a migrant family, the fishing nets and the pieces of boat wood take on new meanings when they conjoin the Palestinian experience with that of Mediterranean migration. And when told through the lens of an allegory of Christ’s Passion, they also work to reference the huge number of relics brought to Europe via the Crusades, becoming a new collection of “mirabilia”. They reference and revive the memory of past journeys between Italy and Palestine that might also have taken place as part of a solely “mental journey”, in which the deep contemplation of devotional images in churches across Italy “amounted to […] a pilgrimage by proxy” (Lansdowne Citation2016, 8). The saint that the church is named after, San Raffaele Arcangelo, is the patron saint of travellers, and given its location in central Milan, Jacir hoped that her new Via Crucis would act as a new community hub for migrants from the eastern and southern shores of the Mediterranean passing through the city. “Avevo la speranza che quei profughi della Siria, dell’Iraq, o della Palestina, entrando nella chiesa di San Raffaele, si sentissero un po’ a casa” (De Leonardis, Citation2016) [I hoped that if those refugees from Syria, Iraq and Palestine came into the church of San Raffaele, they would feel at home]. By tracing throughlines of connection and belonging from place to place and through multiple times, Jacir’s Via Crucis “builds narrative continuity, assembling an interconnected history for a people dispersed geographically” (Demos Citation2013, 118): both international migrants and members of the Palestinian diaspora. And it is in the act of slow contemplation that she hopes a new sense of (Mediterranean) community will eventually form.

Conviviality

In its names and bodies, in its histories, the Other has always been present (Cassano Citation2012, 147)

The hybridization of cultures and people weakens all claims to exclusivity, purity, and integrity, as the Mediterranean knows well, having been fraught, from time immemorial, with intertwined stories, mestizos, migrations, and shelters. (Cassano Citation2012, 147)

This linguistic mosaic designating the passage of peoples and cultures through different Mediterranean spaces demonstrates the need for translations and conversations that include a reflection on the violent entanglements of past colonial contact (Cassano Citation2012, 3). One evening Matar comes across footage of the 1939 documentary Tripolitania playing on Italian television and is struck by how the lens of the Italian camera “eras(es) figures and objects from view” (the Libyan background context) in order to focus on a bellicose young Italian boy “loading and firing imaginary rockets” (Citation2019, 63). But the roundtable discussion afterwards is stuck in sentimentality for the past (and present) – there is no critical engagement either with the contemporary situation in Libya, nor the legacies of Italian colonial atrocities. In contrast, Diana’s insertion of the names of the Roman streets where Libyan dissidents were murdered in plain sight in the 1980s once more im-pli-cates Italy’s lived cartography into a shared history of violence: these are well-known streets such as Via del Castro Pretorio, Via Veneto, Piazza Cavour, Via Principe Amedeo and Via Gioberti. A new, southern-facing map of Rome is being drawn up and translated through cultural prisms so as to incorporate other times and elsewhere spaces. Diana also includes a press image in Evidence of proud, fighting Libyan rebels during the Italian occupation of Libya, guns raised on horseback, in order to illustrate the 2011 uprisings against the Gaddafi regime, collapsing time so as to confront the present legacies of the past. Stories of strength and resistance not only connect temporal points but also unite countries along the shores of the Mediterranean: Labanca comments that one of the principal streets in Palestine is named after Omar al-Mukhter, leader of the Libyan anti-colonial resistance, who was hanged by the Italians in 1931, dislocating any stable sense of “national” memory-at-work (Labanca Citation2010, 13).

For without clear evidence and meaningful memorialisation, things risk getting lost in translation. Jacir’s ongoing work Material for a Film (2005–) pieces together the fragments of the parallel story of another assassination in Rome: this time of Palestinian translator Wael Zuaiter, as part of Israel’s retaliation attacks following the 1972 Munich massacre. At the time of his death, Zuaiter was translating One Thousand and One Nights into Italian and had the second volume of tales in his jacket pocket. It was struck by a Mossad bullet during Zuaiter’s assassination in Rome’s Piazza Annibaliano, on 16 October 1972, and the bullet lodged in its pages. Jacir’s multiform work aims to perform a “recuperative reconstitution” of both Zuaiter’s life, and his death (Kholeif Citation2015, 17).

It is a memorial to untold stories. To that which has not been translated. To stories that will never be written. To the refusal to perform tragic stories for people to read. The one bullet hole of Wael’s story serves as an entrance into all the other stories. (Vali Citation2007)

Conclusions

Going slow is to respect time, inhabit it with few things of great value, with boredom and nostalgia (Cassano Citation2012, 10)

It was as if Europe had woken up and discovered it had all along been living in the kingdom of death. It wanted this to be expressed in art. It feared forgetting. It trusted in that fear, and wanted to communicate and propagate it. The plague had traumatized the imagination. (Citation2019, 92)

Two methods of embracing what Cassano sees as a Mediterranean propensity towards melancholy, boredom and nostalgia are extended by the works of art examined here. First, collecting evidence collating memories and material into a recovery plan becomes crucial, so that “every precious detail of a culture faced with the threat of oblivion (is) salvaged” (Fisher Citation2015, 33). Art such as Emily Jacir’s and Diana Matar’s bears witness to absence and offers wholesale “resistance to cultural erasure” (Fisher Citation2015, 31). The second is that we ourselves undertake to endorse and practise southern values of slowness, contemplation and conviviality in our work and in our responses to the work of others. Drawing on Spivak, David Huddart advocates for slow reading as the utmost responsibility of the critic, the only way possible to attend to the uneven planetary conditions that have been caused by colonialism (Citation2014, 122). “Only through slow and patient negotiations of reading and writing can we adequately relate the nodes that, with varying levels of connectedness, make up our world” (Citation2014, 132). Slowness is an antidote not only to the accelerated rhythms of capitalist progress, but it also counters derogatory notions of belatedness that have so often characterised representations of the south. Indeed, Hisham Matar finds Siena, his own Mediterranean point of pilgrimage, to be perfectly in time. “I never felt rushed or felt myself hurried by anything. Everything I experienced was happening at the pace at which it ought to happen” (Citation2019, 97). Slowness is necessary to form considered understandings of blockages but also to promote deep understanding and lasting impressions. This is a call to us all as writers and readers to attend not only to what we read and write, but how we do so: to reflect on what remains left behind in our notes, the sentences we skip, the words we stumble over, the location of our blind spots on the folds and creases of pages. “When we slow down our reading and thinking, we can be truly critical and attend to the decisions and omissions that necessarily structure our knowledge but that cannot be allowed to go unconsidered and unremembered” (Huddart, Citation2014, 128). The pandemic has slowed down time for so many of us; let us take the opportunity to think, read and write more slowly as we map out new routes of vertical travel in its wake.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Emily Jacir and Diana Matar for permission to reproduce images of their work. The author also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Leverhulme Trust.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2019. What’s the Use? Durham, NC; London: Duke University Press.

- Basu, Paul. 2004. “Route Metaphors of ‘Roots-Tourism’ in the Scottish Highland Diaspora.” In Reframing Pilgrimage. Cultures in Motion, edited by Simon Coleman, and John Eade, 153–178. London: Routledge.

- Bouchard, Norma, and Valerio Ferme. 2013. Italy and the Mediterranean: Words, Sounds and Images of the Post-Cold War Era. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Careri, Francesco. 2002. Walkscapes: Walking as an Aesthetic Practice. Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili.

- Cassano, Franco. 2012. Southern Thought and Other Essays on the Mediterranean. Translated by Norma Bouchard and Valerio Ferme. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Chambers, Iain. 2008. Mediterranean Crossings: The Politics of an Interrupted Modernity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Chambers, Iain. 2010. “Another Map, Another History, Another Modernity.” California Italian Studies 1 (1): 1–14.

- Coleman, Simon, and John Eade, eds. 2004. Reframing Pilgrimage: Cultures in Motion. London: Routledge.

- de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- De Leonardis, Manuela. 2016. “Mille e una notte, I fili della vita.” Il Manifesto. https://ilmanifesto.it/mille-e-una-notte-i-fili-della-vita/.

- Demos, T. J. 2013. The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary During Global Crisis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- DeSilvey, Caitlin. 2006. “Observed Decay: Telling Stories with Mutable Things.” Journal of Material Culture 11 (3): 318–338.

- DeSilvey, Caitlin. 2017. Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dinshaw, Carolyn. 1999. Getting Medieval: Sexualities, Communities, Pre- and Postmodern. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Fisher, Jean. 2009. “Voices in the Singular Plural: ‘Palestine c/o Venice’ and the Intellectual Under Siege.” Third Text 23 (6): 789–801.

- Fisher, Jean. 2015. “Emily Jacir: Visual Poems and Silent Songs.” In Europa, edited by Emily Jacir, and Omar Kholeif, 22–35. Munich: Prestel.

- Fusi, Lorenzo. 2015. “No More Enemies, no More Frontiers. The Borders are red Flags.” In Europa, edited by Emily Jacir, and Omar Kholeif, 46–57. Munich: Prestel.

- Gansel, Mireille. 2017. Translation as Transhumance. Translated by Ros Schwartz. New York: The Feminist Press.

- Gros, Frédéric. 2014. A Philosophy of Walking. Translated by John Howe. London: Verso.

- Huddart, David. 2014. Involuntary Associations: Postcolonial Studies and World Englishes. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Ingold, Tim. 2010. “Footprints Through the Weather-World: Walking, Breathing, Knowing.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 16 (1): S121–S139.

- Ingold, Tim, and Jo Lee Vergunst, eds. 2008. Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Kholeif, Omar. 2015. “Europa: Performance, Narration and Reconstitution.” In Europa, edited by Emily Jacir, and Omar Kholeif, 14–21. Munich: Prestel.

- Labanca, Nicola. 2010. “The Embarrassment of Libya: History, Memory, and Politics in Contemporary Italy.” California Italian Studies 1 (1): 1–18.

- Lansdowne, John. 2016. “The Truth in Material Things.” In Translatio, edited by Emily Jacir, John Lansdowne, and Christopher MacEvitt, 1–11. Rome: NERO Editions.

- Matar, Diana. 2014. Evidence. Schilt Publishing: Amsterdam.

- Matar, Hisham. 2016. The Return. London: Viking.

- Matar, Hisham. 2019. A Month in Siena. London: Viking.

- Mauss, Marcel. (1934) 1973. “Techniques of the Body.” Economy and Society 2 (1): 70–88.

- Parati, Graziella. 2015. “An Art for New Italians: Emily Jacir’s Installations in Milan and Venice.” In Europa, edited by Emily Jacir, and Omar Kholeif, 58–71. Munich: Prestel.

- Pong, Beryl. 2020. “How we experience pandemic time.” July 14th. https://blog.oup.com/2020/07/how-to-experience-pandemic-time/.

- Re, Lucia. 2010. “Italians and the Invention of Race: The Poetics and Politics of Difference in the Struggle Over Libya, 1890-1913.” California Italian Studies 1 (1): 1–58.

- Reed, Arden. 2017. “On Slow Art: Introduction.” Brooklyn Rail.

- Reed, Arden. 2019. Slow Art: The Experience of Looking, Sacred Images to James Turrell. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rothberg, Michael. 2019. The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Solnit, Rebecca. 2001. Wanderlust: A History of Walking. London: Verso.

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Vali, Murtaza. 2007. “All That Remains. Emily Jacir.” ArtAsiaPacific 54 (July/August). http://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/54/AllThatRemainsEmilyJacir.

- Wilson-Goldie, Kaelen. 2015. “Influences: Emily Jacir.” Frieze. https://www.frieze.com/article/influences-emily-jacir.

- Yessis, Mike. 2017. “These Five ‘Witness Trees’ Were Present at Key Moments in America’s History.” Smithsonian Magazine. August 25th. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/these-five-witness-trees-were-present-at-key-moments-in-americas-history-180963925/.