ABSTRACT

The study of marginalia has not been widely discussed in social sciences research and occupies a marginal space in terms of methodological legitimacy. We highlight the value of paying attention to the ways in which participants speak back to the researcher. This paper draws on marginalia found in surveys written or drawn by young people in classrooms across South Wales, demonstrating how various notes and marks made spontaneously by participants can tell us something important and worthwhile about how young people engage with research. We position marginalia as a manifestation of complex power dynamics in the research process that illuminate participants’ negotiation of complex and multiple subjectivities in the literal margins and between the lines of the survey pages. Whilst the sensitive and rigorous analysis of marginalia is fraught with ethical and methodological challenges, we argue that paying closer attention to marginalia presents an opportunity for deeper engagement with participants when undertaking survey research.

Introduction

Marginalia, a variant of ‘paradata’, consists of spontaneous notes or comments offered by participants that are not directly sought by the research or that sit outside the boundaries of the designed data collection methods (McClelland, Citation2016). The forms of marginalia discussed here are notes, drawings and marks made by child participants on a paper-based survey. There is a long-standing interest in literary marginalia (Jackson, Citation2001) but it has only recently been applied as a concept in social research. Existing studies of marginalia in research are predominantly located in psychology (McClelland, Citation2016; Stroudt, Citation2016) and health sciences (Clayton, Rogers, & Stuifbergen, Citation1999; Powel & Clark, Citation2005; Smith, Citation2008). A recently edited collection on paradata in social sciences research suggests a nascent interest in the unintended by-products of social research (Edwards, Goodwin, O’Connor, & Phoenix, Citation2017), but it remains a largely untapped resource.

This paper discusses the history of marginalia, explores current debates surrounding its use in social research and describes how the authors are approaching marginalia generated by children aged 13–14 participating in paper-based surveys. These surveys were delivered as part of a wider project exploring the intergenerational sharing of family values and behaviours, completed by participants in their school classrooms. When delivering the survey, we noticed that some pupils were adding notes, drawings or scribbling out sections of their surveys. Rather than regarding this phenomenon as ‘noise’ or ‘spoiled’ data we began to wonder what additional insights could be gleaned from these instances, especially as the study was concerned with family matters, a subject which seemed to have prompted deeply emotional responses amongst some participants. We considered how we might systemically approach the analysis of these uninvited contributions to the research process, and have thus explored them as a form of paradata.

We begin by contextualising the study of marginalia and debate the various issues entailed in studying that which is considered to be extraneous to the research encounter. We then introduce the research project, discuss our analytical deliberations and provide examples of marginalia from our dataset. Applying a feminist critique of research methods, we discuss how marginalia can be viewed as a manifestation of complex power dynamics in the research process, and how it can hold interest in relation to the negotiation of the subject-as-participant. Finally, we consider the implications of our findings for survey research, arguing that where research is interested in the emotional response of participants to a subject, encouraging marginalia through various methodological techniques could be a valuable addition to research design.

The study of marginalia

The term marginalia was coined in 1832 by S. Taylor Coleridge to refer to the practice of observing reader alterations to books (Jackson, Citation2001). In the literary tradition, inscriptions, notes, highlighting, underlining and dog-earing pages have all been recognised as types of marginalia and have been used to explore the ‘histories’ of books and other documents (Orgel, Citation2015). These marks can be used to understand reader responses, and to track the intellectual development of authors themselves (see e.g. Olsen-Smith, Norberg, & Marnon, Citation2008).

Whilst the study of literary marginalia is well established, interest in the study of marginalia in a research context is a fairly new phenomenon, and as such there are no established conventions for analysing it. Edwards et al. (Citation2017) locate marginalia as a variant of paradata—a term originally intended to refer to the by-products of survey data (Couper, 1998, cited in Nicolaas, Citation2011). The study of paradata is well established in quantitative fields as a tool for enhancing recruitment and retention in survey research via the auditing of keystrokes, revisions, use of ‘help buttons’ and non-responses (Edwards et al., Citation2017). The term has since expanded to include other contextual factors, for example researcher observations of the data collection process (Kreuter and Casas Cordero, Citation2010). Edwards et al. (Citation2017) broaden the focus further to recognise researcher-generated marginalia in the form of fieldnotes in order to better understand the co-construction of research accounts between interviewer and interviewee, arguing that ‘these materials have major analytical value and can potentially add considerable depth to our understanding of the research process’ (Citation2017, p. 5).

Drawing on feminist and critical psychology, McClelland (Citation2016) draws our attention to the value of qualitative marginalia generated by participants themselves. Whilst often disregarded, this unanticipated communication allows researchers to re-imagine expertise, to pay attention when participants ‘speak back’ and to re-examine their own assumptions. Core to McClelland’s approach is a concern for: ‘what lies outside of the text and how does this “outside” perspective contribute something new to the text itself?’ (McClelland, Citation2016, p. 160). The decision to give marginalia a more prominent position within social research raises a whole host of ethical and methodological questions: Are participants writing to us? Is marginalia intended by the author to be read and interpreted?Footnote1 Does it constitute dialogue? And is marginalia supplementary to, or oppositional to the ‘official’ data collection exercise? To answer these questions, we need to consider how participants engage with social research.

The research encounter and marginalia as gift

Marginalia has been located as a ‘by-product’ of social research (Edwards et al. Citation2017) that exists beyond ‘the bounds of what was asked’ (McClelland, Citation2016, p. 159). If, within research, we were only concerned with that which we predict or seek out, then a great deal of data in qualitative inquiry would be lost. Instead of thinking about data in this way (as something found when we seek it), we must shift our understanding of data and data ‘collection’ to something produced in and through research encounters. As such, the text, the context, the participant and the researcher must all be understood as part of the data collection and complicit in the creation of what is regarded as ‘data’.

Once we recognise marginalia as data, there are a number of different ways to frame it. Building on McClelland (Citation2016), we acknowledge that although we cannot know participants’ intentions when making uninvited marks on the page, there is a significant possibility that participants are ‘speaking back’ to us. If marginalia is located as a ‘gift’ we can interpret the impetus to give, and the necessity to ‘properly’ receive it:

Marginalia are a form of labor, a gift, and a challenge from the participant – and they can be ignored by researchers or viewed as an invitation to understand more and understand better. (McClelland, Citation2016, p. 159)

If we interpret marginalia as a form of gift giving this creates a network of social relations where reciprocity is integral (Mauss, Citation2002). This compels us to accept marginalia as ‘proper data’. Creating a ‘hierarchy of data’ based on whether or not particular information has specifically been requested by the researcher denies participants the agency to inform, as well as respond, to research as ‘experts in their own lives’ (Clark & Statham, Citation2005; Mason & Hood, Citation2011) and, ultimately, to ‘give data’. The reciprocity of and engagement with marginalia opens up a potentially valuable space for interaction and collaboration. Seen this way, attention to marginalia can contribute to the determination of what ‘counts’ both to the researcher and to participants.

Here we argue that the careful collection and analysis of marginalia, alongside researcher-requested quantitative and qualitative data, has the capacity to contribute significantly to mixed-methods research design. Marginalia creates a platform where the multi-faceted nature of learning about other people’s lives through complex research encounters is celebrated rather than simplified, with different forms of data informing each other, rather than being artificially divided into different channels of data generation. This argument, however, does not negate the crucial question of whether it is ethically and methodologically legitimate to include marginalia as data given that participants may not realise that their scribbled notes or drawings might be included within research analysis, and, in fact, might reasonably assume that they will be ignored and disposed of.

Negotiating the space between asking and telling

There is no consensus on whether or not marginalia should be considered data. Some argue that marginalia’s main use is quality control: using ‘feedback’ to refine surveys and reduce instances of participants ‘speaking back’. For example, Morse (Citation2005) sees marginalia as the result of ‘dissatisfied participants’ and indicative of the need to improve the research instrument (Citation2005, p. 584). We argue that while marginalia can certainly be employed in the redesign of data collection, it is also meaningful in its own right, rather than indicating deviation from an ‘ideal’ or ‘silencing’ survey design that does not prompt spontaneous comment.

Participant motivations for leaving marginalia are likely to be varied and complex, and we can only ever access contextual, situated and fluid accounts (Haraway, Citation1988), but some important insights can be drawn from a small body of research regarding the use of marginalia in survey research. Clarke and Schober (Citation1992) argue that participants endeavour to answer as consistently as possible when completing surveys, to the extent that they may even prioritise logically consistent responses over those that reflect the complex or inconsistent nature of their lived experience. Galasinski and Kozlowska (Citation2010) identify three distinct strategies available to participants when their lived experiences do not fit the research instrument they are presented with: (1) to reject the survey; (2) to accommodate their experience to fit the survey; (3) to reformulate the survey to accommodate their experience. Compared to the first two options, in which participants either withdraw their engagement altogether, or provide a distanced account that cannot easily be reconciled with their own lived experience, this third strategy—involving the use of marginalia to reformulate the survey—might be seen as a deeper form of engagement with research aims and objectives.

Existing studies of marginalia are predominantly located in psychology (McClelland, Citation2016, Stroudt, Citation2016) and health sciences, where standardised questionnaires are commonly used with patients (Clayton et al., Citation1999, Powel & Clark, Citation2005, Smith, Citation2008). Clayton et al. (Citation1999) found that 25% of multiple sclerosis sufferers invited to complete a survey added extra comments, indicating high levels of investment in the research process and providing further knowledge about participants’ lives. One particular comment offers significant insight into the affective consequences of engaging in research regarding deeply personal topics:

“I hope I have helped you. You certainly helped me. I’m sorry I rattled on so much. I just had to explain why some questions were so difficult for me. Because things are not so cut and dried. Thank you so much for helping me to understand myself better” (Clayton et al., Citation1999, p. 519)

In this comment, Clayton’s participant describes a compulsion to tell more of their story and share their emotional responses to the research, indicating that this process was emancipatory. The strong presence of marginalia in research on chronic conditions is replicated elsewhere (Powel & Clark, Citation2005, Smith, Citation2008).

These studies highlight a somewhat cumbersome articulation between lived experiences and subjectivities, and the standardised items in survey-based research. This may particularly be the case in the field of health sciences where experiences of pain and disease draw the contrast between the personal (experiential) and medical (scientific, standardised) into sharper relief. Ignoring or side-lining these interactions as ‘by-products’ of the research instrument could be seen to do violence to these accounts and the efforts of participants to communicate them. Indeed, Smith argues that participants invoke an ‘imagined researcher’ when completing a survey, and that their marginalia is an attempt to communicate to the researcher, indicating, for example, ‘you won’t know [the answer] by asking like this’, ‘I can’t make my experience fit here’, or ‘this is what you need to know’ (Citation2008, p. 993).

In providing a way for participants’ voices to be heard, marginalia can also take the form of more unruly input—it can often be oppositional, non-co-operative, ‘chaotic, challenging and provocative’ (McClelland, Citation2016, p. 160). Nonetheless, if the creation of marginalia is driven by the belief that the researcher will be able to use it to make sense of the social world, McClelland argues that it should not be seen as beyond the bounds of the research design. Again, these issues provoke us to consider what data is; how we conceptualise it and understand its analysis. The space between the asking and the telling challenges our assumptions about the researcher as all-knowing and privy to ways of framing the narratives of the participants in a way that is meaningful to them. To explore this argument, we now discuss marginalia data generated by young people completing surveys on their family lives, values and relationships—covering deeply personal topics. The complex negotiation of the participant-self is clear in our participants’ written additions and comments.

The research project

The marginalia we draw on in this paper comes from paper-based questionnaires completed by young people in South Wales, administered as part of a wider project into the intergenerational transmission of values and behaviours linked to society (Muddiman, Taylor, Power and Moles; Citationin press). WeFootnote2 developed the questionnaire to explore various behaviours, views and beliefs linked to civil society, alongside young peoples’ relationships with their parents and grandparents. Questions were arranged thematically into sections including: school, views on social issues, where you live, eating habits, clubs and groups, helping other people and the environment, politics, religion, language, mum/dad/carer, grandparents. After piloting, the research team negotiated access to seven secondary schools in South and West Wales. Researchers visited year nine classes (pupils aged 13–14) to introduce the project and to oversee pupils' completion of the surveys between November 2016 and March 2017. We offered both English and Welsh versions of the survey; as will be seen below, the majority of respondents’ marginalia was in the medium of English.

Our research encounters

During our research encounters in classrooms pupils were keen to discuss various aspects of the questionnaire with each other, and we found ourselves having to discourage debate. Participants started to reveal themselves as ‘unruly subjects’ through their interactions with us as researchers—asking us to clarify points and critiquing aspects of the questionnaire. For example, one participant told us that a statement about migrants was ‘racist’ and another said it is ‘stupid’ to ask people whether they think that we should try and stay in the EU because ‘Brexit is happening no matter what’. We also observed instances of students staring blankly at pages, scribbling out sections or spontaneously writing notes in the margins, but did not realise the scope or magnitude of these additional contributions until later.

The next stage of the project was to digitally input the data so that it could be analysed using SPSS. It was at this point that, traditionally, all additional marks and ‘noise’ would be wiped from the dataset, as is standard practice in the quantification of survey content. This did not sit comfortably, especially in cases where it seemed like participants had been trying to communicate directly with us. We decided to catalogue and examine the marginalia, photographing each instance alongside a participant identifier: this catalogue formed our ‘data set’.

Analysing marginalia

There are few instances of shared practice regarding marginalia in social research methods literature. Obtaining participant marginalia was not part of our research design and we could not have predicted that we would be in possession of such a dataset. Once we decided that we wanted to analyse this data in earnest, we were faced with the challenge of devising an appropriate analytical strategy.Footnote3 We began by arranging the physical copies of the marginalia by participant, and then into the different sections of our survey. We could immediately see which sections had the biggest ‘piles’ of marginalia, and began to sift through, section by section, to try and absorb and interpret the different types and instances of marginalia. Guided by the categorisations of marginalia constructed by others (e.g. Stroudt (Citation2016) identified six dimensions: correcting/editing, emphasis/importance, emotions/desires, qualifying, elaborating, theorising), we explored the data thematically (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) in conjunction with our fieldnotes. Through our individual analyses, we developed themes and made notes, then came together to identify shared ground.

While we have chosen to present marginalia as public data here, we have not included all contributions. Specifically, we distinguished between amendments and additions, on the one hand, and deletions, on the other. Locating participants as ‘experts in their own lives’, we felt that amendments and additions are a form of participant contribution where active attempts are being made to affect the data generation. This form of marginalia provides the opportunity to draw on this expertise to improve analysis and interpretation through the incorporation of viewpoints not initially conceived of by the research designer/s. The incorporation of deletions is more problematic; here participants are exercising the right presented by the paper survey format to edit and revise their views; we argue that deleting written content should be held in the same regard as an interviewee immediately withdrawing comments or details of a narrative and, as such, amounts to a withholding of consent to access that specific data. We therefore decided to exclude this data.

We also decided to rule out some ‘minor’ instances of marginalia, for example, misplaced ticks in a multiple-choice grid that had been scribbled out and moved across to the corresponding column—unless it was accompanied by a note or drawing. We did include comments that were written in a box at the end inviting feedback. Whilst these instances were initiated rather than spontaneous, we believe that they are still an important part of participants’ narratives and have been recognised elsewhere as marginalia (e.g. Powel & Clark, Citation2005). Overall, we recorded 334 instances of individual marginalia from n = 104 individuals (just over 10% of our 976 participants) in addition to 62 invited responses in the comments box at the end of the survey.

Data

The data we present here offer some examples of the marginalia we encountered. They all highlight the ways in which data collection is part of a contextual, situated engagement and that the data we collect offers an account of the experiences of the young people, rather than any sort of complete or fixed representation of their ‘life’ or ‘identity’.

Qualification, customisation and reclaiming messiness

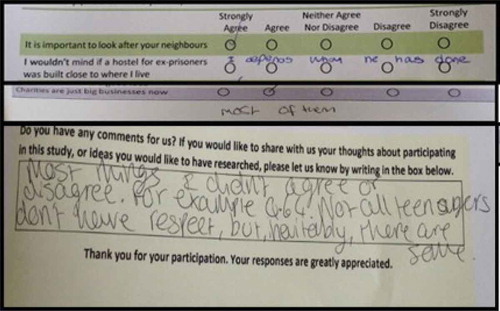

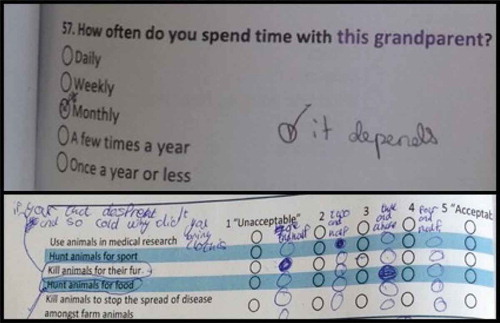

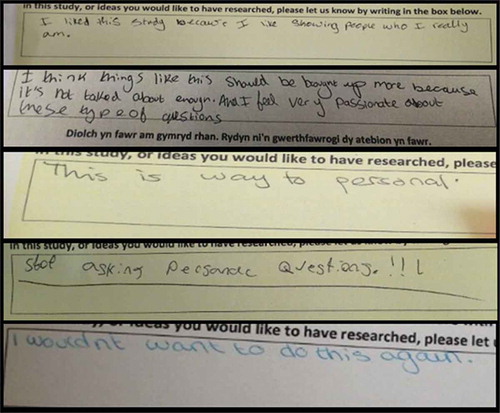

The most common form of marginalia that we encountered was that of adding extra detail and qualifying answers with clauses like ‘it depends’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘mostly’—telling us it’s not that simple. This was reflected in a comment made by one participant at the end of the survey, suggesting a degree of discomfort or frustration about having to select a single answer to represent their thoughts or feelings about certain issues ().

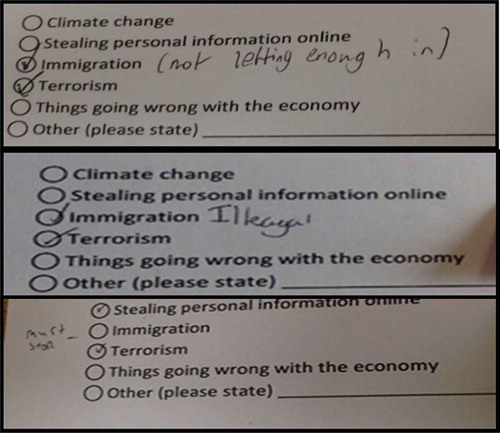

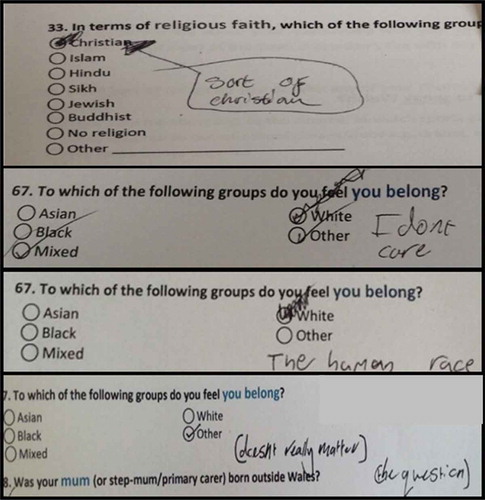

While the level of nuance added by some types of marginalia could potentially aid interpretation of survey answers, some additions also raise questions about how to input and analyse the data statistically. Indeed, in some cases, marginalia troubled our understanding of the selections that participants had made. For example, when asked to select two issues that they feel strongly about from a list, three participants who selected ‘immigration’, added comments suggesting a different orientations to the question: one writes ‘illeagal’ [sic], another writes ‘(not letting enough in)’ and the third writes ‘must stop’ next to immigration (see ). These comments suggest that although all three participants selected the same box, they ascribed different meanings to their selection.

Another variant of marginalia was to add extra tick boxes or additional scale points (). These additions can be viewed as creative responses to the issue of trying to make your experiences or thoughts fit into the survey structure provided—allowing participants to express themselves with more precision. Through these qualifications and customisations, participants are opening up the closed response options we have provided to clarify or aid our interpretations of their response.

Qualifications, clarifications and customisation might also be regarded as a type of as identity work—where participants choose to express more about themselves than the question asked of them, for example telling us ‘both parents work’, or ‘I eat a packed lunch’ in answer to a question about Free School Meal eligibility, or adding ‘I only eat Halal meat’ to a question about food choices.

Informed consent?

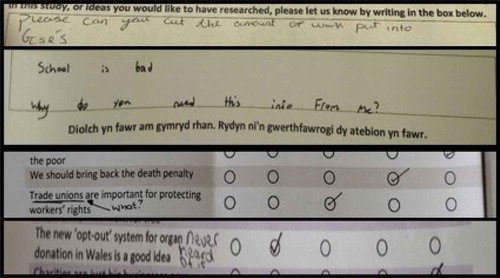

Some comments trouble the idea of informed consent—despite our careful introductions some participants indicated that they didn’t understand why we were asking them to complete the survey, or wrongly assumed that we had more power than we did, for example requesting that we make the school day shorter or reduce homework. Similarly, two questions sparked confusion—the opt-out system for organ donation and views on trade unions—suggesting that responses that assume knowledge of particular things need to be carefully interpreted (). Had these questions been approached in a qualitative interview setting, there would perhaps have been space for explanation, though the responses would not necessarily be ‘improved’ or made ‘more accurate’ as a result: we cannot determine what people do and do not understand, or assume understanding can be improved through information delivery.

Agency, humour and subversion

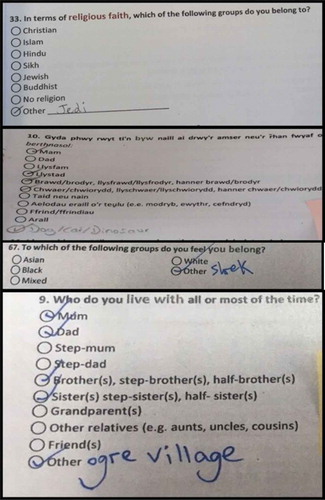

Another form of participant marginalia came in the form of humour. It was common for participants to add details about their pets when asked ‘who do you live with all or most of the time?’; one participant wrote ‘dog, cat, dinosaur’ next to this question, while another recorded their religion as ‘Jedi’. One participant maintained a ‘Shrek’ theme throughout his questionnaire, telling us that he lived in ‘ogre village’ (). We read these accounts back as playful commentaries on the presentation of self implied in the research process, much like the examples of teenager’s subversive survey responses described by Tilbury, Gallegos, Abernethie, and Dziurawiec (Citation2008).

Unease, resistance and agency

Alongside these light-hearted approaches to the task, we found some indications of unease and resistance. Some participants were reluctant to fit themselves within the religious or ethnic categories provided in the survey, and identified themselves between our outside of the options provided. When asked to select the ethnic group they felt they belong to, one participant ticked and scribbled out a few options and wrote ‘I don’t care’ next to the question. Another scribbled out their initial response and wrote ‘the human race’ and another told us ‘(doesn’t really matter) (the question)’ ().

Some participants peppered their surveys with ‘I don’t know’—suggestive of partial disengagement with the research exercise, but not going so far as to leave questions or pages blank as many other participants did. Other participants took a blunter approach simply writing ‘not answering’ next to each question about grandparents.

Evaluations of the participant experience

At the end of the survey participants were asked for their comments, thoughts and suggestions. Whilst some participants gave very positive feedback, indicating that they had found the survey interesting and enjoyable, a number of participants were critical and took the opportunity to tell us that the survey was too personal (). The vast majority of these critical examples are from data collected from one school, where the survey was conducted in a large exam hall rather than the classroom, suggesting that this physical context caused a greater sense of emotional vulnerability and exposure amongst participants. The issue of intrusiveness has been encountered elsewhere in survey research undertaken in schools (Tilbury et al., Citation2008). It is, undoubtedly, deeply troubling that one participant used this space to tell us ‘I wouldn’t want to do this again’ and raises important questions about the nature of voluntary participation in the context of undertaking research in a school environment.

Discussion: power, identity and the ethics of analysing children’s marginalia

Power dynamics are always present in research encounters, particularly where children and young people are the subjects of that research (Grover, Citation2004). Informed by Foucault’s work, Gallagher encourages to think about ‘the ways in which power are enacted; the effects they have, their relations and the various power-apparatuses that operate at various levels of our society’ (Foucault, Citation2003 [1997], p. 13). As such, we can start to think about who has the power to act in the research encounter, and how we then can think about the data ‘collected’ and ‘analysed’. In this discussion we draw on Gallagher’s (Citation2008; with Gallacher, Citation2008) conceptualisation of power as a means of control, resistance, ambivalence and promise, to raise various questions about the ethical and methodological implications of studying participant marginalia, arguing that the manner in which researchers handle marginal data exposes the inherent power dynamics in play during research.

Subjectivities and the power of categorisation

There is a long and well-documented lineage of critique relating to survey research—not least from feminist and post-colonial theory, which share many concerns relating to the method’s dichotomous and reductive approach to subjectivities. On the other hand, it is well-evidenced that many researchers applying survey methods have responded thoughtfully to these concerns in recent years, with multiple choice and ‘other’ options expanding dramatically on such critical markers as race, gender sex and class (Price, Citation2011; Steinbugler, Press, & Dias, Citation2006). That said, surveys continue to hold strong potential for reduction relating to identity and experience; indeed the very principle underlying multiple choice answers lies in the asserted ability of the researcher to define what the possible answers (and, hence, experiences and subjective locations) may be in relation to a topic deigned by that researcher to be relevant to their research question. This power of definition and boundary-marking practice enacts hierarchies that disempower participants and can lead to misrecognition and marginalisation (England, Citation1994). Stacey and Thorne (Citation1985) define this power as an enactment of social organisation, where hierarchies of power, contradictions and multiplicities are concealed behind what are apparently equally weighted options of identity.

Harding’s challenge to scientific objectivity is also writ large in this critique, where the social location of scholars as ‘value-neutral, objective, dispassionate, disinterested’ (Citation1987, p. 182) conceals their position of privilege in enacting social inequality and reduction via the gloss of science and research (for a fuller discussion of these ongoing debates see Harnois, Citation2013). This is particularly problematic when participants are already located within a socially marginalised group, such as children and young people, people of colour, or those experiencing disability (Beresford, Citation1997; Holland, Renold, Ross, & Hillman, Citation2010; Liamputtong, Citation2007; Truman, Citation1999). Indeed, ‘it is rare for young peoples’ reactions to the research process to be heard’ (Tilbury et al., Citation2008).

Ethical research with children and young people demands an acute awareness of the power dynamics and psychosocial implications of the recruitment of child participants, their positionality in research contexts and the requests for personal information from them that social research entails. Issues relevant include a lack of experience and knowledge regarding the nature and use of research data; a potential sense of powerlessness relative to adults organising and conducting research; uncertainty regarding matters of consent and anonymity; and an increased psychological vulnerability to distress caused by the subjects and methods of research (Holt, Citation2004; Valentine, Citation1999). This lack of experience may contribute to the impulse to leave marginalia—indicating that younger participants are not yet fully ‘disciplined’ into the role of research participant.

These issues may be heightened by the lack of direct human interaction when requesting personal details of a person’s life via a survey. When generating qualitative data via conversation the researcher is able to demonstrate empathy and care towards a participant in a manner that surveys, as proxy researchers, cannot. This distance—particularly where survey research relates to deeply personal subjects—may be felt as a mundane symbolic violence to vulnerable participants.

Collaborative research and being ‘on the record’

A feminist approach to renegotiating the ‘inevitability of power hierarchies’ (Maynard, Citation1994) within research has been suggested though ensuring a collaborative approach to data generation is pursued; the question is, whether a survey in its traditional form can ever be located as ‘collaborative’, given the clearly set, pre-printed (or pre-loaded, for internet surveys) questions and answers that participants are presented with, and the solitude of completion. It could be that marginalia represents a desire present within participants to reach towards this sense of collaboration—of co-producing the survey instrument—yet so often these elements are unexplored in analysis or diminished and obscured by the categorisation ‘spoiled data’. This prompts us to consider issues of power as tangled up with the on-going, unfolding negotiation of ethics across the entire research process. Rather than something that can be signed off and left behind, marginalia raises questions of representation and analytical privilege throughout: who gets to make what claims and how they can be justified and presented in a robust, compelling manner?

The study of marginalia is potentially problematic from an ethical perspective as participants may be unclear about what is ‘on the record’, however, it is also important to consider the potential costs of disregarding marginalia. Whilst the exclusion of marginalia appears to eliminate ethical uncertainty regarding data ownership and consent, and enables a ‘clean’ reporting of data within the boundaries of the initial research design, it also removes the opportunity to recognise and engage with the participant ‘reach’ for collaboration in co-producing research. Indeed, this ‘extraneous’ data has the potential to produce useful critiques and to enable reflexivity regarding the nature of such hypotheses and research questions, and to disregard this data may be short-sighted if a meaningful contribution to a field of study is intended.

We suggest, then, that any study of marginalia should be guided by the intention of recognising and respecting participants’ ‘reach’ for collaboration, remaining alert to the potential ethical issues and with an eye firmly trained on the critiques and suggestions they have offered. We therefore argue that the incorporation of some forms of marginalia—as a form of reflexivity applied to a medium that traditionally discourages dialogue—is both ethical and valuable. In this sense, marginalia can be used as a tool for researchers to re-examine their own assumptions about research design and data collection (McClelland, Citation2016). This requires a reconceptualisation of what rigour means, what ethics covers, and a consideration of whether this approach tallies with participants’ expectations of taking part.

Moving forward with survey data: subjectivity and capturing complexity

Marginalia can be seen to ‘disrupt and challenge assumptions about the research processes, conceptual definitions, and issues of measurement and analysis’ (McClelland, Citation2016, p. 160), by drawing our attention to the assumptions inherent in surveys but also more broadly underpinning much social science research. Instead of imagining data as something uncovered through astute research methods, we can consider research encounters as assemblages of participant, researcher, context and setting, with the research method—survey, interview, fieldnotes—an active part of the production of the data, and the researcher as complicit in the production and the research data and encounter. As the marginalia we present here demonstrates, participants in survey research have the power to resist reductive practices in survey design and implementation—particularly where paper ‘hard copies’ are used to generate data. The materiality of the survey itself; the blank spaces of survey pages provide space for participants to involve themselves in the co-production of design by adding detail to multiple choice options, exceeding an implied ‘character limit’ in the length of a line to be filled in, or scribbling notes and drawing pictures in the margins. The contemporary transition to online survey tools offers no such spaces—one cannot write in the margins of webpages. This digital shift quashes the potential for co-productive capacity, and the data that we share here would be invisible to us were online survey methods implemented rather than the distribution of paper copies:

The move to online survey data collection, even when a comment box is offered, removes the potential for marginalia to be given over the course of the survey; comment boxes frame participant feedback differently than the unsolicited and spontaneous feedback that comments on a written page can provide (McClelland, Citation2016, p. 161)

Our suggestion here is that online surveys would benefit from the incorporation of space where marginalia can occur. In current iterations of commonly used online survey tools, this could be accomplished by the liberal use of free text boxes across surveys, along with text prompts to suggest that participants might like to comment on their answer further, clarify, or critique the nature of the question. With current technology, however, there is scope to achieve much more; particularly as tablet and mobile devices accommodate the use of electronic pens or fingers to make notes, highlight and draw on pages outside of text fields. We would like to see a tool designed for survey research that is not just open to marginalia but actively encourages it. This would function to preserve the traditional benefits of survey research whilst also encouraging the collaborative, interactive approach to research suggested by Maynard (Citation1994). This might enable a more positive research encounter for participants, and could also result in deeper engagement and more nuanced accounts of their lived experiences and views.

Being alive to the possibility of engagement with marginalia opens up new avenues of interaction with survey data, and new understandings of the research encounter itself.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all of those young people who participated in the survey, and in particular, those who left the unexpected gift of marginalia—we hope that we have done justice to their ‘extraneous’ communications. We are also grateful to all of the teachers who welcomed us into their classrooms, and to colleagues who gave up their own time to assist us with data collection far and wide: Rhian Powell, Rhian Barrance, Hannah Blake, Dan Evans and Constantino Dumangane Jr. We could not have begun to analyse all of this data without the help of Liza Donaldson and our two undergraduate research placement students Louise and Josie, who did an excellent job of cataloguing the data and were a pleasure to work with. The research underpinning this paper comes from a project instigated and led by Prof Sally Power and Prof Chris Taylor. We thank them for their overarching support of this venture and for their valuable intellectual contributions during the research, analysis and writing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Esther Muddiman

Esther Muddiman is a research associate at the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods at Cardiff University. She is particularly interested in identity, belonging, food, family and youth engagement, and is currently working on an Economic and Social Research Council project exploring the intergenerational sharing of values and behaviours linked to civil society. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2630-6134 Twitter: @drmuddiman

Jen Lyttleton-Smith

Jen Lyttleton-Smith is a research fellow at the Cascade Children’s Social Care Research and Development Centre at Cardiff University. A childhood sociologist, she is particularly interested in issues around gender, power, subjectivity and the participation of children and young people in research and public decision-making. She is currently undertaking a post-doctoral fellowship funded by Health and Care Research Wales investigating the implementation of co-productive practice in children’s social care services. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0704-2970. Twitter: @jensmithcardiff

Kate Moles

Kate Moles is a Lecturer in Sociology at Cardiff University. She is interested in the relationships between everyday practices of memory, heritage, mobility and place, and particularly the sensitivities and sensibilities an ethnographic approach to these topics brings. She has an on-going interest in the margins, edges and boundaries; from post-colonial identities in a park to the place where the sea hits the shore and now, here, to the scribbles on the sides of surveys. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1926-6525. Twitter: @molesk)

Notes

1. It is important to distinguish between comments made spontaneously throughout the course of a questionnaire, and the comments/feedback invited at the close of a study. Whilst the latter may not be considered to be true marginalia, both types of contribution are valuable in the goal of better understanding how participants engage with research. We return to this issue when considering our analytical approach.

2. Author 1 and Author 3 were directly involved in this project.

3. At this point, Author 2 was recruited to the analytic process.

References

- Beresford, B. (1997). Personal accounts: Involving disabled children in research. London: Social Policy Research Unit.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

- Clark, A., & Statham, J. (2005). Listening to young children: Experts in their own lives. Adoption & Fostering, 29, 45–56.

- Clarke, H. H., & Schober, M. F. (1992). Asking questions and influencing answers. In J. M. Tanur (Ed.), Questions about questions: Inquiries into the cognitive bases of surveys (pp. 15–48). New York: Russell Sage.

- Clayton, D. K., Rogers, S., & Stuifbergen, A. (1999). Answers to unasked questions: Writing in the margins. Research in Nursing & Health, 22, 512–522.

- Edwards, R., Goodwin, J., O’Connor, H., & Phoenix, A. (Eds.) (2017). Working with paradata, marginalia and fieldnotes: The centrality of by-products of social research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- England, K. V. (1994). Getting personal: Reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. The Professional Geographer, 46, 80–89.

- Foucault, M. (2003 [1997]). Society must be defended: Lectures at the College de France, 1975–76 (D. Macey trans.). London: Penguin.

- Galasinski, D., & Kozłowska, O. (2010). Questionnaires and lived experience: Strategies of coping with the quantitative frame. Qualitative Inquiry, 16, 271–284.

- Gallacher, L. A., & Gallagher, M. (2008). Methodological immaturity in childhood research? Thinking through participatory methods’. Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark), 15, 499–516.

- Gallagher, M. (2008). ‘Power is not an evil’: Rethinking power in participatory methods. Children’s Geographies, 6, 137–150.

- Grover, S. (2004). Why won’t they listen to us? On giving power and voice to children participating in social research. Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark), 11, 81–93.

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14, 575–599.

- Harding, S. G. (Ed.) (1987). Feminism and methodology: Social science issues (introduction to chapter six). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Harnois, C. E. (2013). Feminist measures in survey research. London: Sage.

- Holland, S., Renold, E., Ross, N. J., & Hillman, A. (2010). Power, agency and participatory agendas: A critical exploration of young people’s engagement in participative qualitative research. Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark), 17, 360–375.

- Holt, L. (2004). The ‘voices’ of children: De-centring empowering research relations. Children’s Geographies, 2, 13–27.

- Jackson, H. J. (2001). Marginalia: Readers writing in books. London: Yale University Press.

- Kreuter, F., & Casas-Cordero, C. (2010). “Paradata”, Working Paper Series of the German Council for Social and Economic Data, Working Paper No. 136. Germany: Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

- Liamputtong, P. (2007). Researching the vulnerable: A guide to sensitive research methods. London: Sage.

- Mason, J., & Hood, S. (2011). Exploring issues of children as actors in social research. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 490–495.

- Mauss, M. (2002). The gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Maynard, M. (1994). Methods, practice and epistemology: The debate about feminism and research. In M. Maynard & J. Purvis (Eds.), Researching women’s lives from a feminist perspective (pp. 10–26). Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

- McClelland, S. I. (2016). Speaking back from the margins: Participant marginalia in survey and interview research. Qualitative Psychology, 3, 159–165.

- Morse, J. M. (2005). Evolving trends in qualitative research: Advances in mixed-method design. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 583–585.

- Muddiman, E., Taylor, C., Power, S., & Moles, K. (in press). Young people, family relationships and civic participation. Journal of Civil Society.

- Nicolaas, G. (2011). Survey paradata: A review (Publication No. NCRM/017). ESRC National Centre for Research Methods (NatCen). Retrieved from http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/1719/1/Nicolaas_review_paper_jan11.pdf

- Olsen-Smith, S., Norberg, P., & Marnon, D. C. (Eds.) (2008). Melville’s Marginalia Online Retrieved from. http://melvillesmarginalia.org/

- Orgel, S. (2015). The reader in the book. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Powel, L. L., & Clark, J. A. (2005). The value of the marginalia as an adjunct to structured questionnaires: Experiences of men after prostate cancer surgery. Quality of Life Research: an International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 14, 827–835.

- Price, K. (2011). It’s not just about abortion: Incorporating intersectionality in research about women of color and reproduction. Women’s Health Issues, 21, 55–57.

- Smith, M. V. (2008). Pain experience and the imagined researcher. Sociology of Health and Illness, 30, 992–1006.

- Stacey, J., & Thorne, B. (1985). The missing feminist revolution in sociology. Social Problems, 32, 301–316.

- Steinbugler, A. C., Press, J. E., & Dias, J. J. (2006). Gender, race, and affirmative action: Operationalizing intersectionality in survey research. Gender & Society, 20, 805–825.

- Stroudt, B. (2016). Conversations on the margins: Using data entry to explore the qualitative potential of survey marginalia. Qualitative Psychology, 3, 186–208.

- Tilbury, F., Gallegos, D., Abernethie, L., & Dziurawiec, S. (2008). ‘Sperm milkshakes with poo sprinkles’: The challenges of identifying family meals practices through an online survey with adolescents. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11, 469–481.

- Truman, C. (1999). New social movements and social research. In B. Humphries & C. Truman (Eds.), Research and inequality (pp. 33–45). London: Routledge.

- Valentine, G. (1999). Being seen and heard? The ethical complexities of working with children and young people at home and at school. Ethics, Place and Environment, 2, 141–155.