Abstract

Medication is closely involved in the subjective experience of chronic diseases, but also in the chronification process of illnesses which is described in this paper in the specific case of HIV. The development of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) and the progressive recognition of their potential dual use as treatment as prevention (TasP) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) reshape the experience of HIV and its transmission. Acknowledging the importance of a socioanthropological approach to drugs, this paper highlights how therapeutic strategies of treatment and prevention currently shape the process of HIV chronification and its experience for people concerned with ARVs in Switzerland, whether they are seropositive patients on lifelong treatment or seronegative people affected by the preventive properties of drugs.

Introduction

HIV has been considered a unique illness, since its emergence in the 1980s. The fundamental work of Steven Epstein on the early years of the epidemic explores the history of the identification of the virus (Epstein Citation2001a), but also the exemplary social mobilization of HIV seropositive people to obtain treatment (Epstein Citation2001b). Both of these phenomena arguably participated to biosocialisation of HIV (Rabinow Citation2010; Rose and Novas Citation2005): a drastic change in the life perspectives and socialities of seropositive people emerged from the availabilities of these treatments. It is this shift from fatality to chronicity (Pierret Citation1997; Squire Citation2010; Swendeman, Ingram, and Rotheram-Borus Citation2009) that is the starting point of our research on HIV normalization in the specific context of HIV routine of care in Switzerland.

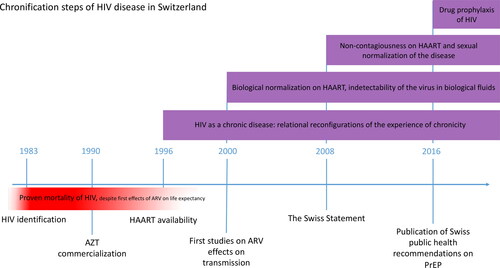

If antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) are participating to the broad and well described phenomenon of pharmaceuticalisation (Collin and David Citation2016), one of the effects of this is the chronification of living on treatment that we describe in this paper. Our work inscribes itself in the recent studies linking materialities and medical anthropology (Parkhurst and Carroll Citation2019). We define chronification as a dynamic, temporal process through which the biosocial existence of subjects concerned by an acute disease is (re)shaped by a therapy (one-time and past and/or present and long term) that alleviates, but does not eliminate, the symptomatic and organic manifestations of the disease. When producing chronification, treatments generate a reconfiguration of the bio-psycho-social experience of illness (Pierret Citation2003), as well as the reshaping of patient’s self-objectives, particularly in narrative and relational terms (Dumit Citation2004). More generally, this focus on chronification allows us to highlight how these biosocial trajectories of illness reorient what others have called modes of existence (Souriau Citation2009; Simondon and Simondon Citation2012) through looping effects (Hacking Citation1996) that are at once embodied, experiential and relational. As we will see, while HIV cannot be eradicated from bodies, treatments can strongly modulate it as an organic and experiential illness by integrating it into the daily lives of both infected people and non-infected ones who consider themselves at risk of infection. One crucial element of this modulation is precisely the temporal dimension: these therapeutic innovations are the vectors of an extended process by which people, as well as their partners and relatives, are inscribed into a dynamic and iterative approach to the disease, which overcomes the illness’s formerly fatal character without eradicating it. This process is characterized by four main vectors: (i) molecular effects on bodies and transmission; (ii) the enrolment over time in an essential dependency on drugs that become existential equipment at the biological and biographical levels; (iii) the long-term experiences of living with the illness (whether one is HIV-positive or considered to be at risk); and (iv) the healthcare structures, health policies, and clinical practices. Consequently, the aim of this paper is to describe the nexus of embodied experiences shaped by ARV as these partake to the larger chronification of HIV initiated by the emergence of antiretroviral therapy (ART) ().

Figure 1. Chronification steps of HIV in Switzerland, under the effects of ARVs, showing the piling experiences of chronicity lived by the concerned people.

In line with anthropological studies on drugs, we start from the assumption that the ‘biography of [HIV] pharmaceuticals’ (Van Der Geest, Whyte, and Hardon Citation1996), or the contextually and socially metabolized ‘fluid drugs’ (Hardon and Sanabria Citation2017), induce the clinical chronification of HIV by profoundly (re)configuring the everyday lives of people living with HIV as a chronic condition (Langstrup Citation2013). In expanding these perspectives, we then suggest that the chronification of the illness, far from being only an experiential and/or relational matter, is also shaped by the drugs’ biological effects. The disappearance of medical symptoms such as viremia or the decrease in immune cells has a looping effect that induces forms of sociality profoundly modulating the existential dimensions of patients’/people’s lives (Collin, Otero, and Monnais-Rousselot Citation2006). As it will be emphasized in the remaining, what we observe is then the entanglement of different phenomena, which have traditionally been explained in alternative biological and social terms. Pharmaceuticalization induces the chronicification of living with the disease, which becomes a shared condition in a community, linked, in turn, by the use of specific treatments that produce a specific form of biosociality driven by drugs: the chemosociality, through a new ‘chemical ecology’ of molecules and/or therapeutic indications (Shapiro and Kirksey Citation2017, 485).

In what follows, after a brief pharmacological account of the recognition of the extension of ARVs properties in Switzerland, which allows us to define also the methodological approach of our research, we first describe the reconfigurations of the experience of chronicity among HIV-positive persons on ART. Following the properties of ARVs on viremia and transmission, we then discuss two situations of prevention through drugs. The first one is the so-called treatment as prevention (TasP), by which seropositive people undergoing treatment become non-infectious for their partner(s) – a medically recognised practice by physicians in Switzerland since 2008 (Vernazza et al. Citation2008). As we will see, this situation participates to HIV normalization while still retaining several complexities of experiencing the disease (Persson Citation2013). The second situation we analyse is the emergence of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in Switzerland, officially recognised by a medical publication in 2016 (Office Fédéral de la Santé Publique Citation2016), which consists of HIV-negative people taking a medication to avert the infection as a preventive actionFootnote1. We show how PrEP also engenders routines of medical follow-up for HIV-negative people, which modulate chronicity of the illness not only in relation to the organic presence of the disease in one’s body and its curability, but also in relation to the preventive perspective of HIV-negativity. Moreover, due to its non-recurring nature, we decided not to analyse post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) – which consists of a preventive treatment with ARVs for one month following a potential exposure to the virus. PEP can be taken once and never again and thus does not engage most individuals to a regular medical follow-up for this treatment. To sum up, by analysing the stacking experiences of people taking ARV in different contexts of treatment and prevention, we wish to demonstrate the growing pivotal place of drugs in the chronification process of HIV. This dual use of the same drug in TasP and PrEP is indeed at the roots of profound reconfigurations with regard to, as Shapiro and Kirksey (Citation2017) also argued, the extension of chemosociality to people who are not biologically infected with HIV.

The chronification process as guiding thread

The current population of Switzerland is about 8 million people: approximately 17,000 of them are living with HIV, and about 450 people are diagnosed per year. Since the first protease inhibitors were commercialized in Switzerland in 1996, the multiplication of molecular classes used to treat HIV allow to block the replication of the virus inside the patient’s CD4 cells, in order to protect his or her immune system and to limit the virus’ proliferation into the body (so called ART). This has led to the first great improvement in the life expectancy of patients: while the HIV diagnosis until then used to be a near-death sentence, HIV became a medically manageable chronic disease with the emergence of ART. The second biological change produced by ARVs is the effect on HIV transmission and the relative experiences of chronicity of people concerned by the virus. As ARVs lead to a drastic decrease of viremia in the biological fluids of HIV-positive people, new properties of HIV treatment were gradually recognised during the 2000s: these drugs also reduce HIV transmission in serodiscordantFootnote2 heterosexual couples (Castilla et al. Citation2005) and during pregnancy (Garcia et al. Citation1999). Later, in 2008, the Swiss Federal Commission for AIDS-Related Issues officially recognized the non-infectiousness of people on ART during sexual intercourse (Vernazza et al. Citation2008). Since then, it has generally been admitted that TasP allows people on treatment to be considered sexually noninfectious for their partner(s). Indeed, these molecules have an evidence-based dual effect: they treat HIV-positive people and protect the HIV-negative partner from transmission (Cohen et al. Citation2011, Citation2016). As described by Guta, Murray, and Gagnon (Citation2016), this theoretical possibility to control the transmission of the disease may also imply forms of surveillance of the individuals concerned. Furthermore, ongoing biomedical research on drugs and their effects on viremia and infectiousness has led to recognize PrEP as prevention of infection even before exposure to the virus (Grant et al. Citation2010; Molina et al. Citation2015)—that is to say, from at-risk sexual relations. The drug on which these enquiries are based is Truvada®: a combination of two antiretroviral active ingredients, tenofovir disoproxil and emtricitabine, which is used to treat HIV in combination with a third molecule and is therefore frequently part of the treatment prescribed to HIV-positive people. In 2016, the Swiss Federal Commission for AIDS-Related Issues published guidelines for prescribing Truvada®, in order to help physicians to follow-up people on PrEP (Office Fédéral de la Santé Publique Citation2016), leading HIV-negative people to take a drug for HIV prophylaxis.

In order to analyse the chemosocial transformations of the embodied, experiential and relational processes involving the concerned people and ARVs, we conducted a socioanthropological inquiry based on interviews with HIV-positive people taking ARVs and with nurses, physicians, and pharmacists involved in TasP and PrEP administration. We observed the key role that the ARVs play at the crossroad of biological effects and practical uses (Akrich Citation1996), and as a ‘life-transformer’ in the daily lives of people. According to the perspective proposed by Keogh (Citation2017), rather than observing the ‘acceptance’ of these indications, we explored how people use them as well as the meaning and significance they invest in their practices. We specifically explored how people concerned by drugs are closely involved in constructing this multifaceted process of chronification.

The present analysis is therefore based on two sets of data. The first includes interviews with people on ART (n = 8) conducted in 2015. These interviews took place within a longstanding immersion in clinical follow-up. The second set of data focuses on HIV prevention through drugs and is built upon a set of interviews conducted with professionals (n = 18) as well as observations conducted during a collaborative research with a healthcare centre for men who have sex with men (MSM). In Switzerland, the follow-up of people considered ‘at risk’ of HIV transmission varies according to the canton in which it takes place. The institution where we conducted fieldwork is a hybrid structure that emerged around 2010, and its development is intertwined with institutional processes. This specialized sector is hosted in a broader public funded institution dedicated to sexual and reproductive health. Its implementation shines light on the institutional recognition of HIV struggles carried out by local HIV-militants, who sometimes are working with this institution and are increasingly included in clinical practices. Let us also mention that Truvada®’s indication for PrEP is not officially recognized by the Swiss agency for therapeutic products, Swissmedic, and, as a consequence, its purchase is not reimbursed by Swiss insurance plans for this specific prophylactic use. But beyond these national specificities, it is crucial to consider that PrEP, as an extension of TasP, has radically transformed the ontology of these drugs from a pivotal part of the treatment approaches to the pathology to a potential preventive tool. This shift is moving HIV towards the wider range of diseases characterized by drug-induced chronification at the crossroad of treatment and risk prevention (e.g. some genetic disorders, forms of cancer, metabolic disorders, etc.). As we will see, this chronification is not only an obviously practical issue but also induces a deep embodied, experiential and relational reconfiguration in the lives of the people directly concerned by the illness and/or indirectly by the risk of it, as well as of the clinical settings and institutional norms around HIV prevention and treatment.

As the fieldwork was carried out in collaboration with medical actors and given that the data were considered sensitive under Swiss law because of their relation to the participants’ health, the research required ethical approval – obtained in December 2014 – by the local ethical commission. In order to explore the chronification process of HIV, we identified people for whom the HIV diagnosis was known and whose treatment was established for several years. These participants were aged from 35 to 65 years old at the time of the interviews. The first author, both a pharmacist and as a socio-anthropologist, conducted the fieldwork. To be reflexive about this position, we must notify that given that people living with HIV were recruited within a pharmaceutical setting, the research had a limited access to people living with HIV without any medical follow-up, whose understanding of health may be less in line with that of the Swiss healthcare system. While limiting as to the scope and extension of our findings, this is also one specificity of our research: the specific positionality of a relationships between the main investigator and the interviewers, situated inside the process of medical follow-up, allowed both a deep knowledge of the individual care trajectories and of the shared knowledges on molecules as they shaped the everyday life of all participants. Furthermore, this has also made it possible to engage with people that could have been hardly met outside this system.

Experiences of chronicity among seropositive persons on lifelong ART

The implementation of ART has brought radical changes in the care and the life perspectives of HIV-positive people, but it has also, and above all, induced major embodied, experiential and relational reconfigurations in their lives, redefining their experience of chronicity. Such changes can be grasped in three complementary registers characterised by different temporalities whose synchronicity can vary from one case to another, composing – to use a musical metaphor – various tessituras of the existence transformed by the treatments. The first one is the redefinition of identity, in which the lived special effects of ARVs reported by people underline new perspectives on mortality, highlighting the self-definition strengthened by drugs. The second one concerns the life projects allowed by ART: it is worth noting the symmetrical chronification induced by ARVs with regard to both HIV and medical care, specifically through the imperative of following-up still associated with the monitoring of ARVs’ side effects. This follow-up is shaped by the ARVs’ properties, leading to personal life events like parenthood, for instance, being absorbed into clinical relations. A third register concerns living daily with drugs and the chemosociality associated, shaped by a paradoxical effect of ARVs: while these treatments allow immunological normality, their material and visible presence in people’s daily lives remains a social marker of illness, both to their relatives and to themselves.

Identity and sense of mortality

An important reconfiguration in HIV-positive people’s account of their engagement with drugs concerns their relationship with their own mortality, as evidenced by Christiane, a 48 years old woman who was on ART for fifteen years:

To me, I take them unwillingly, of course, because I try to heal myself with natural medicines, so drugs are problematic to heal myself this way [laughs]. I’m sure that every medicine is, somewhere, like a poison. I’m very aware that we have no idea about long-term effects. We don’t know what they could do. I know all of that. So, I take them because I have to, because if I don’t, we know the result. That’s what keeps me alive. I know it and I have no choice… . But on the other hand, I think that maybe I will not die of HIV, but I will die because of my medicines [laughs].

We see here how the theme of mortality – prevented or induced by the drug – runs along another recurrent narrative: that of the potential of other threats to one’s life. The immune normalization produced by the treatments enables a consideration of dying from something other than HIV, such as the medicines themselves in this case, or more frequently simply any another potential illness. More generally, the recent treatment-induced chronification of HIV has brought forth a new life perspective to seropositive people, which allows them to feel, consider, and experience an ordinary account of a human’s mortal condition. This notwithstanding, the chronicity of their treatments still plays a major role in their understanding of their life trajectories. They continue to fear living their whole life with drugs, especially because of the uncertainties related to the risk of long-term adverse events—such as renal or bone impairment, as documented for Truvada®. Here, one’s own experience of side effects becomes the biographical perspective of an imagined mortality alternative to the threat of HIV. This, we argue, illustrates the role of ARVs in the fashioning of one’s own identity narratives as they emerge from the experience of ART chronicity.

ART as vector of life projects

In our analysis of the Swiss case, ART also induces transformations in the life projects envisaged by people concerned, deeply linked to the medical follow-up required by drugs. Clinical relationships were already centred on viremia and immunological monitoring, much like tolerance of adverse effects and compliance with treatment. Yet, people on ART have addressed the possibility of them becoming parents, particularly women who were susceptible to transmitting the virus to their children during pregnancy before the introduction of the treatment. Christiane explains how such properties of ARVs allowed her and her husband to have HIV-negative children:

When I learned I was seropositive, I’d met my husband, who was negative. But we would have liked kids, but with all we heard… I wanted to do the right thing. (…) So, I started taking the medicine, and it was my first pregnancy. (…) And then we had two children, who are negative and are doing well, so that is pure happiness. That’s why I am so glad for all that you do for us. That’s why I never refused a study for 15 years. That’s thanks to you, the institution, to all those studies, that we can have a normal life, and me, I can fulfil my life project of becoming a mum.

ART enables a consideration of existential issues or life projects of patients, which are now made conceivable and achievable by the availability of the treatments and the chronicity of the illness it produces. In other words, the clinic extends from short-term surveillance to long-term counselling, generated for patients the possibility to pursue life projects of a ‘normal life’ (think also about the previous example of dying from something else than the virus besides the realization of parenthood).

Biological undetectability and social visibility

One can observe an interesting chemosocial tension in the daily life of ARVs users, actively participating to the chronification process because of the necessary daily works it requests (Baszanger Citation1986). While ART can lead to immunological normality – confirmable by a blood test of CD4 T-cells and an undetectable viral load – the material and visible presence of the drugs in people’ daily lives remains a social marker of illness for both their relatives and themselves. Fred, a 48 years-old respondent on ART since ten years exemplifies how cultivating immunological normality with these treatments renders the disease visible in one’s close social circles. As a reaction, then, Fred explains how he hides from his boyfriend when he takes the pills: a behaviour which could seem of little importance but which is pivotal in the people’s real life.

For him … It was difficult to see the drugs. At the beginning, it was always because the drugs put him in front of … Well, he learned about the disease at this time so … He learned about it when I arrived at the emergency room, a week before. I told him, ‘Well, here I am. I am HIV-positive’. So here it is … So, it was recent for him too. And then, when I learned this, I know that the first week, or maybe the first three months, I thought about it every day. I told myself, ‘Here, I am HIV positive’… ‘It’s not cool, I’m not healthier, it’s not right’ … So I think the same exact thing happened to him. And each time, my drugs put him in front of the disease. So, I am quite discreet when I take them.

As Fred explains, in his view, watching him taking his treatment reminds his companion about the illness and saddens him. Fred links his boyfriend’s reaction to the fact that he had decided not to talk with his companion about the diagnosis during the first five years after the virus’ discovery. He said that the absence of sex between them did not expose his partner to a risk of transmission, but when the ART was introduced the secret of the diagnosis became unbearable. These very practical difficulties in relation to the treatment indicate an often unsuspected or neglected dynamics initiated by the drug. While producing the absence of the disease organically, the treatment becomes a visible social marker of the illness, not only for the HIV-positive person him/herself but also for his/her relatives, which in turn leads to active processes of unknowing of the disease presence in these relationships.

These tactics and strategies of unknowing in these everyday drug practices are consistent with the observations of Sylvie Fainzang (Citation2003). On the one hand, she described the practical and functional logic of handling drugs in the private sphere – which often leads individuals to place the current treatments in the kitchen, for example, to simplify the decision. On the other hand, she also underlined the symbolic logic of these active processes of visibilization/invisibilization, as in the case of potentially stigmatizing antidepressants being stored in the intimacy of one’s bedroom (Fainzang Citation2003, 146). It appears clear that everyday HIV drug practices follow a comparable symbolic logic, albeit somewhat different: most of the interviews show that ARVs are well hidden so that they are not visible to visitors. Yet, they are also generally visible, in the sense of locatable and identifiable by relatives who are aware of the treatment. Considering more generally these kinds of relational, strategic, and processual aspects of visibility and invisibility, an analogy can be drawn between the drug and the virus. While drugs allow people to make the disease materially undetectable at the viremic level,Footnote3 the object of the drugs is also a relational marker of HIV, deeply hidden in the intimacy of private spaces were accessibility and visibility gets negotiated with relatives aware of the infection. And yet, it is precisely this biological undetectability of the virus in the body that, in turn, can become a publicly stated evidence of control and visibility of disease in interaction with others. To summarize, day-to-day uses and experiences of ARVs reshape the identities and socialities of seropositive people on lifetime treatment (and their relatives) through an active process of biological and/or social (in)visibilization of the disease.

From HIV treatment to HIV prevention: TasP and PrEP

We will now define and observe in further detail the two preventive uses of ARVs: TasP, where the treatment of an HIV-positive people protects his or her partner(s), and PrEP, where seronegative people considered ‘at risk’ of HIV use a specific ARV before sexual intercourse.

TasP as “molecular condom”

As described above, highly active antiretroviral therapy marks not only the experience of chronicity but also relationships and sexuality of HIV-positive people. These are specifically transformed by TasP (Persson, Ellard, and Newman Citation2016).

Since 2008, the clinical recognition of ARVs’ preventive properties offered new possibilities for the medical follow-up of HIV-positive patients; specifically, it became possible to treat someone to prevent HIV transmission in serodiscordant couples. In an illustrative way, a physician related the story of one of his HIV-positive patients who had unprotected sex with his girlfriend while his viremia was high. Acting as though he was medically considered infectious, he thought that if he did not ejaculate in her partner, it was safer sex, when this is not the case. Facing this problematic situation, the physicians proposed that he be treated for HIV, even if the medical criteria for initiation were not reached (i.e. low CD4 count), in order to protect his partner. It is important to note the complex history of how these preventive properties were recognized. Indeed, before 2011, it was exceptional to use TasP as an indication to begin treatment when clinical criteria were not present. Since then, a turning-point medical trial demonstrated that early HIV treatment has huge benefits for the illness’s evolution (Cohen et al. Citation2011). As a result, HIV guidelines have gradually been adapted recommending that every person newly diagnosed with HIV be treated right away (European AIDS Clinical Society Citation2019; AIDSinfo Citation2019), regardless of CD4 count. As a consequence, TasP became a secondary advantage of ART for physicians and was no longer an indication to treat. It is important to note that, at least in North America, these properties of ART became the basis of a new prevention strategy allowing for the monitoring of the communities’ viral load of HIV-positive population and by extension their contagiousness (Gagnon and Guta Citation2012).

The effects of this reconfiguration are well illustrated by the question of parental projects related to reducing the biological risks of transmission. Pregnancy was possible before for serodiscordant couples but only by using different technical strategies to protect the HIV-negative partner, such as by using artificial insemination or sperm washing. Physicians now say that TasP, and abandoning condom use, allows couples to have children in a more ‘normal’ way. As Tom, a physician working in hospital, said:

So, classically, what we propose when there is a new HIV diagnosis, maybe at the second or third consultation, is to bring the partner along, to be transparent and give him all the information because it’s still a scary disease. And now, we explain rather than reassure people, by saying that now on treatment, the majority of people are undetectable pretty quickly and can have an almost normal sexuality, even having children in a normal way—that’s a message that is not at all passed in the mainstream discourses. […] People have not at all integrated these prevention messages [such as TasP]. Well, they often come to see me because they have trouble believing the spouse, so the doctor has to explain [laughs]. And anyway, the choice is left to the patient and finally to the HIV-negative partner. If he does not feel comfortable with it and wants to continue using condoms, in the end, he is the one who chooses. So, it must be a decision within the couple, and both must agree to stop the use of the condom.

This professional, like others among our respondents, highlights the importance of TasP in his clinical practice and underlines the main advantage of TasP for couples; allowing them to become parents without the need to rely on burdensome reproductive measures. In fact, we observe here a substitution of tools: drugs overcome reproduction technologies that were habitual until recently for HIV-positive people and their partners. In a nutshell, the drug replaces the condom and becomes a ‘molecular condom’. Yet, the drug implies the recurring need to consult and discuss with a physician, in order to really earn confidence in its effects, and integrate this biomedical fact of non-infectiousness into one’s habits. In sum, the long-term medication with ARVs here is a way of cultivating – through exceptional measures like chronic treatment and medical surveillance – the non-exceptionality of one’s life projects, such as natural procreation for heterosexual couples.

Importantly, this preventive strategy symmetrically reconfigures the experience of the chronic illness and the medical follow-up for both the HIV-positive and the HIV-negative partner. An office-based physician with longstanding experience, Mathilde, tells us, when describing people who have been on ART for a long time, that the TasP becomes a routine not without difficulties in the medical follow-up:

So, I recommend that the HIV-negative partner be tested once a year. But, in practice, they do it once and never again, because the worried ones are the HIV-positive partners, not the HIV-negative ones. It’s the infected partner who is very often worried about contaminating their partner. And frequently, the most reticent is the seropositive patient. And frequently, the seronegative person has no worries about that.

This recurrent absence of fear of getting the virus among HIV-negative partners led this professional to develop specific strategies: she sees the couple during the first treatment appointment and then only the HIV-positive patient for the usual follow-up. According to this physician, the absence of fear indeed leads partners to not being regularly screened for HIV, even though the medical recommendations require them to do so. At the same time, she adapts her clinical practice by meeting the seronegative partner once and never again, precisely because of TasP’s reliability and safety when its criteria are fulfilled. Note that it is not yet clear how couples’ experiences within this treatment strategy in the Swiss context will affect the abandonment, or not, of condom use, nor how it will more generally affect the variability of the serological identities created by TasP (Persson, Newman, and Ellard Citation2017).

Pre-exposure prophylaxis: HIV-negative patients and new meanings of ARVs

One very important pharmacological, clinical, and social characteristic of ARVs is their acknowledged third use—after ART and TasP—as HIV prevention for HIV negative people, in the form of PrEP. Its prescription now includes people who are not infected but at risk of being infected, with this risk being not only biological but also strongly linked to their relational life, in particular their sexuality. Indeed, the evidence of preventive properties of drugs for seropositive persons (TasP) paved the way for their prescription to prevent transmission to seronegative persons during sexual intercourse (McCormack et al. Citation2016). PrEP consists of people taking Truvada®—which, as we have seen, is a well-known ARV already used in treatments for seropositive people—before sexual intercourse when they have the potential risk of HIV infection (Office Fédéral de la Santé Publique Citation2016).

To continue with the reconfigurations linked to ARVs’ preventive uses, we observed that the same drug has specific and contrasted meanings depending on the situations in which it is used. This is the case of Truvada®, which is blurring the frontier between ‘safe’ and ‘unsafe’ sex (Auerbach and Hoppe Citation2015), between drugs and sexualities, and is also linked to bareback sex history (Brisson Citation2017). Indeed, Truvada® is now characterized by different ‘modes of existence’ (Latour Citation2013). The pharmacological ontology of these two molecules gets negotiated among users and prescribers, each questioning each other’s understanding of the drug and its use. Indeed, Truvada® has different meanings depending on whether it is taken as a treatment or a prophylaxis measure. When Truvada® is a part of ART, imposed by the virus, it may acquire a demarcated profile associated with chronic drug intake and the ensuing constraints it imposes of patient experience. In PrEP, the drug takes up liberating allure, almost an anxiolytic one. People often ask it to their physician to prevent HIV, but also to decrease the fear of becoming infected by HIV. Or it used to relax from the trauma of the first decades of the disease, to distance oneself from the atrocious past experiences of the disease. As Anna, physician in a MSM medical centre, puts it:

Well, in the gay world, in general, there is still a huge trauma of what HIV has been like in the last 30–40 years. There are a lot of people who have lost – well, I’m talking about the older generations, but – people who have lost half of their friends, and so it’s left a mark on a whole generation. And then I think that this PrEP, beyond even an extremely effective treatment to prevent HIV, there are a certain number of people who feel reassured by the fact that they are taking it and that the HIV that has marked them for 40 years, […] with this treatment, they can forget about it. And so PrEP can have different effects, as other medicines, not just on prevention but… it’s suddenly also something that reassures you, you know.

Regarding the variations observed in drug intake experiences, a particularity of ARVs is their side effects, such as nausea for Truvada®. Many studies about drug adherence underline the importance of this phenomenon in peoples’ daily lives on ART, when medicines complicate the illness experience (Nguyen et al. Citation2007) and sometimes even lead people to voluntarily not take the drugs. This is, in a surprising and perhaps paradoxical way, less observed in PrEP, notwithstanding the fact that the same molecules are involved. But a wider reconfiguration is at stake with PrEP: the emergence of new actors in the HIV healthcare system and the creation of new roles for others already present actors, such as physicians. In Switzerland, PrEP is indicated for MSM exposed to high HIV risk, including a significant number of partners (Office Fédéral de la Santé Publique Citation2016), creating new biosocialities along the way (Girard et al. Citation2019) but also ‘stratified biomedicalization’ (Torres-Cruz and Suárez-Díaz Citation2019). The new actors include seronegative people, people ‘at risk’ of contracting the virus due to their sexual behaviour. Some of them enter medical follow-ups which did not take place before the drug intake; and for some others, their usual medical follow-up is reinforced by more frequent recommended HIV and STI tests.

Associated with the emergence of this new patient in healthcare systems, new roles are also being created by PrEP, particularly in physicians’ activities (Nicholls and Rosengarten Citation2020). If they are not already followed in an MSM medical centre, people asking for PrEP are often referred to a health community centre because of the specificity of the indication for this drug, as HIV was usually prevented with non-drug-based tools before PrEP. Physicians at health community centres are now prescribing Truvada® or its generic version in their daily practice, a drug which was usually reserved for HIV specialists, for the sake of PrEP. This shift in preventive tools then leads physicians to routinely use a drug which requires specific follow-ups, such as of renal and bone function, along with more frequent blood tests. Furthermore, we observe that this potentially chronic follow-up of HIV-negative people varies according to the affective and sexual life of the PrEP user, who may, for instance, stop using the PrEP if he or she decides to abandon all prevention measures with a partner he or she trusts.

To summarize, we observe that ARVs get used as preventive measures, which allow users to replace some tools by others, that is, drugs. Established reproductive procedures for seropositive individuals get supplanted by TasP. Widely employed preventive tools like condoms get replaced by TasP and PrEP depending on the end-user of the drug. In doing so, these drugs become part of larger chemosocial experiential and relational processes. At the same time, taking up these drugs in these forms of sociality also involves an increased medical follow-up—in principle, at least—both for people living with the virus and for seronegative people, whether they are a partner of a seropositive person or a seronegative PrEP user. This, then, is another major reconfiguration linked to drug prophylaxis, which goes at the core of institutional configurations of HIV healthcare: the greater the diversification of people concerned by chronic drug usage, the larger the associated medical follow-ups and, simultaneously, the more moderate the specialization of how this follow-up is performed.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have highlighted some aspects of the complex and multilevel trajectories of drug-based HIV treatment and prevention strategies at the crossroad of biological and social ontologies of these drugs, lay uses and experiences, clinical practices, as well as relational processes of sense making. We have shown how illness chronification is deeply fashioned by drugs in a specific context where novel possibilities and constraints emerge for HIV patients, at risk individuals family and professional caregivers.

In the first part, we have shown how the emergence of ART modulates HIV chronification, with a specific expansion of disease temporalities that ‘normalizes’ the presence of the disease thus removing its centrality for mortality and parental projects of patients. Then, following the same drugs and the growing acknowledgment of their preventive properties, we have highlighted how TasP and PrEP as drug prophylaxis lead to the chronification of prevention, engendering chronic but also reversible follow-ups for HIV-negative people, whether they are the partner of a seropositive person or a PrEP user. Consequently, as HIV eradication from bodies is, for now, impossible, ARVs instate a complex biological and social dynamics that extends over time. The temporally reduced protection provided by the drugs requires regular intakes, induces specific experiences of (health) care, demands cultivating the visibility/invisibility of the disease in viral (biological) and relational terms, inaugurates forms of sociality that simultaneously depart from and depend upon the presence of the virus.

This, to conclude, is the HIV chronification described in this paper: a shift from chronic illness to chronic condition not only for people biologically infected by the virus. A merging of care and prevention that takes place through a dynamic process involving a chemo-functional dependence on molecules, the reversible biological immunity they produce, and the follow-up monitoring of adverse effects or sexually transmitted disease this process demands. Far from being only a matter of drug effects and adherence, this process entails an embodied, experiential and relational reconfiguration in the lives and the life perspectives of the people involved. The increasing preventive recognition and uses of ARVs not only participate to the silencing of the disease in bodies, but also to the shaping of chronic condition where the boundaries between communicable and non-communicable disease, patient and at-risk individual, immunity and infectivity get eminently blurred.

Notes

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the Commission cantonale d’éthique de la recherche sur l’être humain du Canton de Vaud (CER-VD), Lausanne, Switzerland.

Disclsoure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgments

We thank Cinzia Greco and Nils Graber for their very useful inputs on the paper, Mélody Pralong and Elio Panese for proofreading, and Luca Chiapperino for the final proofreading and his important comments. Finally, we also thank all the informants met during the research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 PrEP can be taken in two ways: an everyday pill, or an “on demand” posology, which means the drug is taken just a few days around the sexual intercourse(s). This two posologies for the same drug will be analysed here together, because the data mobilised here are principally interviews with healthcare professionals and do not show great fluctuations on this point. The « informal PrEP », which is the use of ARV for HIV-prevention without any medical follow-up is also very interesting. But we were unfortunately unable to observe it because of our study design, which complicated significantly the access to informal PrEP users.

2 Serodiscordant couple: when one partner is seropositive and the other one is seronegative.

3 This means that the virus can no longer be detected through blood testing, which is one of the therapeutic objectives of the treatment, together with increased CD4 lymphocyte count.

References

- AIDSinfo. 2019. “Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV.” https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines.

- Akrich, Madeleine. 1996. “Le Médicament Comme Objet Technique.” Revue Internationale de Psychopathologie 21: 135–158.

- Auerbach, Judith D., and Trevor A. Hoppe. 2015. “Beyond ‘Getting Drugs into Bodies’: Social Science Perspectives on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 18 (Suppl 3): 19983. doi:https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.18.4.19983.

- Baszanger, Isabelle. 1986. “Les Maladies Chroniques et Leur Ordre Négocié.” Revue Française de Sociologie 27 (1): 3–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3321642.

- Brisson, Julien. 2017. “Reflections on the History of Bareback Sex through Ethnography: The Works of Subjectivity and PrEP.” Anthropology & Medicine 26 (3): 315–345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2017.1365430.

- Castilla, Jesús, Jorge Del Romero, Victoria Hernando, Beatriz Marincovich, Soledad García, and Carmen Rodríguez. 2005. “Effectiveness of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy in Reducing Heterosexual Transmission of HIV.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 40 (1): 96–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.qai.0000157389.78374.45.

- Cohen, Myron S., Ying Q. Chen, Marybeth McCauley, Theresa Gamble, Mina C. Hosseinipour, Nagalingeswaran Kumarasamy, James G. Hakim, et al. 2011. “Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy.” New England Journal of Medicine 365 (6): 493–505. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1105243.

- Cohen, Myron S., Ying Q. Chen, Marybeth McCauley, Theresa Gamble, Mina C. Hosseinipour, Nagalingeswaran Kumarasamy, James G. Hakim, et al. 2016. “Antiretroviral Therapy for the Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission.” New England Journal of Medicine 375 (9): 830–839. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1600693.

- Collin, Johanne, and Pierre-Marie David, eds. 2016. Vers une pharmaceuticalisation de la société?: Le Médicament Comme Objet Social. Problèmes Sociaux et Interventions Sociales 77. Québec (Québec): Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Collin, Johanne, Marcelo Otero, and Laurence Monnais-Rousselot, eds. 2006. Le Médicament au Coeur de la Socialité Contemporaine: Regards Croisés Sur Un Objet Complexe. Collection Problèmes Sociaux & Interventions Sociales 23. Sainte-Foy, Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Dumit, Joseph. 2004. Picturing Personhood: Brain Scans and Biomedical Identity. Information Series. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Epstein, Steven. 2001a. Histoire du Sida. 1, 1,. Paris: Les empêcheurs de penser en rond.

- Epstein, Steven. 2001b. Histoire du Sida. 2, 2,. Paris: Les empêcheurs de penser en rond.

- European AIDS Clinical Society. 2019. “EACS Guidelines.” https://www.eacsociety.org/guidelines/eacs-guidelines/eacs-guidelines.html.

- Fainzang, Sylvie. 2003. “Les médicaments dans l’espace privé: Gestion individuelle ou collective.” Anthropologie et Sociétés 27 (2): 139. doi:https://doi.org/10.7202/007450ar.

- Gagnon, Marilou, and Adrian Guta. 2012. “Mapping HIV Community Viral Load: Space, Power and the Government of Bodies.” Critical Public Health 22 (4): 471–483. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2012.720674.

- Garcia, Patricia M., Leslie A. Kalish, Jane Pitt, Howard Minkoff, Thomas C. Quinn, Sandra K. Burchett, Janet Kornegay, et al. 1999. “Maternal Levels of Plasma Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 RNA and the Risk of Perinatal Transmission.” New England Journal of Medicine 341 (6): 394–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199908053410602.

- Girard, Gabriel, San Patten, Marc-André LeBlanc, Barry D. Adam, and Edward Jackson. 2019. “Is HIV Prevention Creating New Biosocialities among Gay Men? Treatment as Prevention and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Canada.” Sociology of Health & Illness 41 (3): 484–501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12826.

- Grant, Robert M., Javier R. Lama, Peter L. Anderson, Vanessa McMahan, Albert Y. Liu, Lorena Vargas, Pedro Goicochea, et al. 2010. “Preexposure Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men Who Have Sex with Men.” New England Journal of Medicine 363 (27): 2587–2599. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1011205.

- Guta, Adrian, Stuart J. Murray, and Marilou Gagnon. 2016. “HIV, Viral Suppression and New Technologies of Surveillance and Control.” Body & Society 22 (2): 82–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X15624510.

- Hacking, Ian. 1996. “The Looping Effects of Human Kinds.” In Causal Cognition: A Multidisciplinary Debate, edited by Dan Sperber, David Premack, and Ann James Premack, 351–394. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hardon, Anita, and Emilia Sanabria. 2017. “Fluid Drugs: Revisiting the Anthropology of Pharmaceuticals.” Annual Review of Anthropology 46 (1): 117–132. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041539.

- Keogh, Peter. 2017. “Embodied, Clinical and Pharmaceutical Uncertainty: People with HIV Anticipate the Feasibility of HIV Treatment as Prevention (TasP).” Critical Public Health 27 (1): 63–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2016.1187261.

- Langstrup, Henriette. 2013. “Chronic Care Infrastructures and the Home.” Sociology of Health & Illness 35 (7): 1008–1022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12013.

- Latour, Bruno. 2013. An Inquiry into Modes of Existence: An Anthropology of the Moderns. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- McCormack, Sheena, David T. Dunn, Monica Desai, David I. Dolling, Mitzy Gafos, Richard Gilson, Ann K. Sullivan, et al. 2016. “Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent the Acquisition of HIV-1 Infection (PROUD): Effectiveness Results from the Pilot Phase of a Pragmatic Open-Label Randomised Trial.” The Lancet 387 (10013): 53–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2.

- Molina, Jean-Michel, Catherine Capitant, Bruno Spire, Gilles Pialoux, Laurent Cotte, Isabelle Charreau, Cecile Tremblay, et al. 2015. “On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection.” The New England Journal of Medicine 373 (23): 2237–2246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1506273.

- Nguyen, Vinh-Kim, Cyriaque Yapo Ako, Pascal Niamba, Aliou Sylla, and Issoufou Tiendrébéogo. 2007. “Adherence as Therapeutic Citizenship: Impact of the History of Access to Antiretroviral Drugs on Adherence to Treatment.” AIDS 21 (Suppl 5): S31–S35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000298100.48990.58.

- Nicholls, Emily Jay, and Marsha Rosengarten. 2020. “PrEP (HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis) and Its Possibilities for Clinical Practice.” Sexualities 23 (8). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460719886556.

- Office Fédéral de la Santé Publique. 2016. “Recommandations de la commission fédérale pour la santé sexuelle (CFSS) en matière de prophylaxie pré- exposition contre le VIH (PrEP) En Suisse.” Bulletin 4.

- Parkhurst, Aaron, and Timothy Carroll, eds. 2019. Medical Materialities: Toward a Material Culture of Medical Anthropology. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Persson, Asha. 2013. “Non/Infectious Corporealities: Tensions in the Biomedical Era of ‘HIV normalisation.” Sociology of Health & Illness 35 (7): 1065–1079. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12023.

- Persson, Asha, Jeanne Ellard, and Christy E. Newman. 2016. “Bridging the HIV Divide: Stigma, Stories and Serodiscordant Sexuality in the Biomedical Age.” Sexuality & Culture 20 (2): 197–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-015-9316-z.

- Persson, Asha, Christy E. Newman, and Jeanne Ellard. 2017. “Breaking Binaries? Biomedicine and Serostatus Borderlands among Couples with Mixed HIV Status.” Medical Anthropology 36 (8): 699–615. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2017.1298594.

- Pierret, Janine. 1997. “Un Objet Pour la Sociologie de la Maladie Chronique: la Situation de Séropositivité au VIH ?” Sciences Sociales et Santé 15 (4): 97–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.3406/sosan.1997.1413.

- Pierret, Janine. 2003. “The Illness Experience: State of Knowledge and Perspectives for Research: The Illness Experience.” Sociology of Health & Illness 25 (3): 4–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.t01-1-00337.

- Rabinow, Paul. 2010. “L’artifice et Les Lumières: de la Sociobiologie à la Biosocialité.” Politix 90 (2): 21–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/pox.090.0021.

- Rose, Nikolas, and Carlos Novas. 2005. “Biological Citizenship.” In Global Assemblages, edited by A. Ong, S. J. Collier, 439–463. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Shapiro, Nicholas, and Eben Kirksey. 2017. “Chemo-Ethnography: An Introduction.” Cultural Anthropology 32 (4): 481–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.14506/ca32.4.01.

- Simondon, Gilbert, and Nathalie Simondon. 2012. Du Mode D’existence Des Objets Techniques. Nouv. éd. rev. et Corr. Philosophie. Paris: Aubier.

- Souriau, Etienne. 2009. Les Différents Modes D’existence: suivi de, du Mode D’existence de L’oeuvre à Faire. Métaphysiques. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Squire, Corinne. 2010. “Being Naturalised, Being Left behind: The HIV Citizen in the Era of Treatment Possibility.” Critical Public Health 20 (4): 401–427. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2010.517828.

- Swendeman, Dallas, Barbara L. Ingram, and Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus. 2009. “Common Elements in Self-Management of HIV and Other Chronic Illnesses: An Integrative Framework.” AIDS Care 21 (10): 1321–1334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120902803158.

- Torres-Cruz, César, and Edna Suárez-Díaz. 2019. “The Stratified Biomedicalization of HIV Prevention in Mexico City.” Global Public Health 15 (4): 598–513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2019.1679217.

- Van Der Geest, Sjaak, Susan Reynolds Whyte, and Anita Hardon. 1996. “The Anthropology of Pharmaceuticals: A Biographical Approch.” Annual Review of Anthropology 25 (1): 153–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.25.1.153.

- Vernazza, Pietro, Bernard Hirschel, Enos Bernasconi, and Markus Flepp. 2008. “Les Personnes Séropositives ne Souffrant D’aucune Autre MST et Suivant un Traitement Antirétroviral Efficace ne Transmettent Pas le VIH Par Voie Sexuelle.” Bulletin Des Médecins Suisses 89 (5): 165–169.