Abstract

This paper explores the capacity of yoga narratives and practices to contribute to and relate ideas about health. It adds theoretically to existing literature on yoga by introducing the concept of the ‘health imaginary’ as an analytic lens for considering yoga discourses in late modern times, where personal health care and spiritual ambitions are once again becoming blurred. With this perspective, the paper provides a thorough analysis of how yoga postures (asanas) are conceived to work therapeutically, in yoga’s recent history and in present-day yoga therapy. Taking case studies from India and Germany, it is shown empirically how the application of asanas is rationalized differently in specific geographical and therapeutic environments – particularly regarding the presumed theory of the body. Thus, the concept of the health imaginary not only provides analytic space to explore the implicit logics and goals of healing in different contexts, but also offers clues about the distinct social, cultural/religious, and local influences that draw people into yoga and contribute to its selective appropriation across the globe.

Introduction

Many people today take up yoga for health-related reasons, to ‘energize’ their body or to find relief from physical ailments, and learning the correct performance of a posture is often accompanied by some remarks on its beneficial impact. This process may also encourage a particular view of physical and mental wellbeing, the embodied self, health, and individual agency. In this article I consider these discourses in terms of the ‘health imaginary’ of postural yoga. To discuss health-related prospects in these terms is not to question the efficacy of respective strands of yoga practice. My concern is not with clinical evaluation but with the exploration of shared discourses, institutional structures, and forms of yoga practice as perceived to influence health. From a medical anthropology perspective, health is not an objective category but contingent on social and cultural influences in which measurable, naturalized/biological and imaginary aspects are interlinked. Health ideals, assumptions about the causes and development of illness, perceived symptoms, and expectations about appropriate treatments are always culturally and socially shaped and may alter over time and in different environments. Usually, these patterns escape our awareness but may emerge through comparative analysis.

In a recent paper on habitual language use in yoga classes, I show how the instruction of yoga postures has changed since the 1970s to reflect and encourage new ways of considering bodily processes in relation to the self, a healthy life, and well-being (Hauser Citation2013b). Yoga was taught to lay people in classes since about 1918, when Yogendra opened the first modern yoga school in Mumbai (Alter Citation2014, 65). Yoga teaching conventions have changed since then, but much more is at stake than didactic style in understanding these changes. Alongside the reframing of yoga as a therapeutic device – a process originating in colonial India (Alter Citation2000, Citation2004) – biomedical knowledge has expanded substantially within clinical fields and as a cultural discourse taken up in different ways across diverse contexts. It is now widely recognized within social science that a broad ‘medicalization’ of society has occurred – there has been a comprehensive reframing of basic life experiences and moral issues by means of medical categories, practices, and institutions (Conrad and Bergey Citation2015). In this process, care of the self has become an overarching strategy for cultivating body and mind, with an emphasis on individualized monitoring for body maintenance and disease control (Foucault [1986] Citation2012; Ziguras Citation2004). Against this background, popular and idealized bodily practices such as postural yogaFootnote1 provide fertile ground for cultivating ideas about the human body and its purpose, the mind-body connection, and the individual and social effects of embodied discipline.

Scholars of the recent transcultural history of yoga have stressed this capacity with respect to (1) the reframing and development of yoga as physical culture and preventive health care, (2) the epistemic twists in translating ancient Indian concepts in terms of modern human biology, aetiology and science, (3) the influence of suggestive techniques from Mesmerism, Couéism, and Mind Cure, (4) the modern emphasis on relaxation, (5) the discursive link between health-promoting yoga and Hindu-nationalist morality, and (6) the institutionalization of yoga-based healing regimes and sites (see Alter Citation1997, Citation2000, Citation2004, Citation2005; De Michelis Citation2004; Singleton Citation2005, Citation2007, Citation2010; Jain Citation2010; Baier Citation2016; Newcombe Citation2017; Birch Citation2018; Foxen Citation2020). From this perspective the social and cultural character of yoga-related health assertions is pretty clear. Yet so far these findings are primarily about cultural and historical ‘others’. What is more, in a period of all-pervading medicalization, the gradual biopolitical (self-) positioning of therapeutic forms associated with yoga provides a rich field for investigating the perfectability of health, the fringes of modern categories and social fields, and human aspirations. In this paper I therefore propose a concept to sharpen analytic focus on these issues rather than a fundamentally new approach.

In the following I adapt the idea of the ‘social imaginary’ (Castoriadis Citation1975) to the realm of health, with specific reference to yoga.Footnote2 I use the term ‘health imaginary’ to describe a set of shared notions about health, the human body, illness causality, and various dimensions of healing. As a form of cultural knowledge the health imaginary is both fairly stable and prone to gradual change. Influenced by hegemonic biomedical standards, it may also reflect complementary and alternative approaches. As embodied knowledge it is mostly pre-reflective and resonates with acquired dispositions (habitus), somatic awareness, and feelings. It can be traced empirically in narratives, shared practices, and the institutionalization of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. The health imaginary thus refers to a collectively produced, socially enacted and negotiated vision of the body and medical reality. Although the concept is grammatically singular, it encompasses a wide variety and heterogeneity of perspectives, key points, and logical operations involved. The concept is useful in inviting us to pay attention to and explore the socially constructed nature of a health reality in diverse settings. Unlike notions of the social imaginary, which are generally linked to the idea of a particular community (Castoriadis Citation1975; Anderson Citation1983; Taylor Citation2004) or to a particular era (Appadurai Citation1996, 31; Taylor Citation2004), the health imaginary, I suggest in this paper, focuses on continuities and modifications in the constitutive elements of health-related practice across time and space, without necessarily evoking a shared health identity (Whyte Citation2009). As Strauss (Citation2000, 183, Citation2005) points out in her multi-sited ethnography, bodily practices of yoga generate many different communities of practice, some of them transnational, yet still intersecting with a variety of localized circles, and shaped by diverse perspectives, values, and ideologies. Similarly, Hoyez (Citation2007) emphasizes how yoga practices can be seen as creating ‘therapeutical landscapes’, that structure the healing environment.

The health imaginary is a conceptual tool that opens up analytic space beyond normative statements about whether or not a particular therapy ‘really’ works. We know from placebo research and religious anthropology that therapeutic processes entail much more than simple cause and effect, that successful recovery is also based on reframing disorder and suffering in meaningful terms (Csordas Citation2002; Thompson, Ritenbaugh, and Nichter Citation2009). Present-day postural yoga can be identified around the world as a system for health and wellness through the use of similar key terminologies and body techniques, yet any one approach to yoga is shaped by distinct social, cultural, time-specific, and local conditions (see, for instance, Hauser Citation2018). Analysis of the implicit logics and goals of healing in these different contexts will offer insights into the factors that influence the selective appropriation and transcultural dynamics of postural yoga. I argue that in order assess to the social relevance of postural yoga for different kinds of people in today’s interconnected world we need to understand the scope and competing logics of its health imaginary. The ways we and others think about how yoga works – about how postures, breathing and so on relate to improvement of some kind – are, I suggest, also representations of how in late modern, if not post-secular times, personal health care, and spiritual ambitions are once again becoming blurred.

In what follows, I look closely at the systematic application of postural yoga for preventative and curative purposes, to increase bodily rehabilitation and as an adjunct treatment. This application can be glossed as yoga therapy, a term that I use in a generic sense to encompass a variety of specific therapeutic approaches to yoga – cognizant of the problem that this term neither indicates a defined discipline nor an accredited specialization.Footnote3 My main focus is on asanas – the Sanskrit term asana means literally ‘seat’ or ‘posture’ – i.e., on the ways that practices of yoga postures are imagined to heal. Due to limits of space, I give related techniques such as breathing (pranayama), purifying actions (kriya) or meditation (dhyana) only cursory attention. With regard to healing, conceptualizations of breath and breathing deserve more attention, but would constitute a subject of their own. Here, therefore, I concentrate on the characteristic feature of modern postural yoga: the performance of respective bodily exercises, although undoubtedly yoga cannot be reduced to mere asana practice.

In the first section I show how in the last hundred years asanas became the primary therapeutic device associated with yoga and subject of an elaborate discourse on their therapeutic benefits. I consider the therapeutic presentation of individual asanas exemplarily in a selection of influential yoga manuals and present-day websites describing the powers of specific postures. These sources cannot tell us directly how postures are, or have been, instructed therapeutically in actual class settings or used in individual practice, but they highlight how yoga postures have been imagined therapeutically from the early twentieth century onwards. Nonetheless, this section shows how individual asanas were projected as a curative inventory, presuming a physiologically influenced, simplified understanding of the body. This specific view on how yoga works resonates with a self-help approach and continues to encourage new additions to the inventory.

After describing these early mechanistically influenced health assumptions – rarely questioned in the social context of yoga practice –, I introduce two case studies where yoga postures are applied and rationalized in different healing contexts. As a trained anthropologist with extensive fieldwork experience in India, but living in Germany and participating in an urban yoga setting for more than a dozen years, I chose a therapeutic institution from each country. The second section examines how postural yoga is put to work in the therapeutic settings of a yoga clinic in the vicinity of Bengaluru (Bangalore) in southern India, where distinct asana routines are employed to cure patients with a great variety of symptoms and diseases. In the third section I examine posture practice as part of a mind-body cure through the work of one of Germany’s largest providers of postural yoga, Yoga Vidya, at its headquarter in a provincial spa town. Since German naturopathy historically influenced the modern reframing of asana practice in India (see first section), the present-day application of yoga in this therapeutic realm promised an interesting point of comparison. I show that at both sites, therapists refer to a five-layered concept of the human body, but have different opinions on how asana practice affects these layers and thus influences the healing process. Clearly, posture practice as a therapeutic device can be imagined in various ways. In conclusion I argue that metaphysical ways of framing the therapeutic application of yoga seem to increase, and thus resonate with the diagnosis of a post-secular era.

The material presented in these case studies originates from a preliminary study of promotional material, selected primary archival literature, and publications by medical staff at the yoga clinic in India, to which I made a brief fieldtrip in 2017, and by therapists at the German site, in particular their lectures on the healing properties of yoga that are available online. Ideally this preliminary study will lead to more substantial fieldwork on how the health imaginary is put in practice in the course of social interaction.

Asanas as therapy

Postural yoga differs from other kinds of physical exercise in the emphasis given to the variety of benefits of stretching and cultivating the body. When considering taking up yoga – by surfing the internet, flipping through a yoga manual or trying a yoga class – a potential student’s attention is sooner or later drawn to statements about the therapeutic advantages of particular postures, sometimes alongside the view that a specific ‘yogic’ mental attitude is the ideal prerequisite of sincere asana practice. According to a survey in Germany, for instance, people usually practice yoga for its expected health benefits (in 2014).Footnote4 While yoga styles and individual teachers differ in the depth or detail in which they explain the healing properties of particular postures, routine statements suggesting that each has a specific therapeutic field of application constitute a significant didactic element in yoga tuition, teacher trainings, and printed instructions.Footnote5 Moreover, asanas are appreciated not only for stabilizing the musculoskeletal system but also for improving organ and endocrine function. On the German website of a Bikram Yoga studio, this capacity is symbolized by small organ emblems.Footnote6 Practicing the bow pose (dhanurasana), for instance, is claimed to ‘alleviate or even heal almost any back problem; the stimulation of the body’s front side helps improve digestion, immune and hormonal disorders (even diabetes); [it also] strengthens kidney, spleen and liver function’ (Author translation).Footnote7

B. K. S. Iyengar’s Light on Yoga was a path-breaking paradigm for this medicalized view of yoga, an encyclopaedic yoga manual first published in 1966 and now available in several translations and new editions. Its Appendix on ‘Curative Āsanas for Various Diseases’ lists 88 different health problems ranging from ‘asthma’ to ‘diabetes’ and ‘displacement of the spinal discs’, each to be treated with the accurate and regular performance of selected asanas.Footnote8 The bow pose for example was recommended for all three of the health problems just mentioned (Iyengar Citation1979, 489, 494, 495). Iyengar deserves credit for having compiled and enhanced the then existing therapeutic knowledge of postural yoga and its physiological effects. His compendium differentiated more than 200 asanas and his step-by-step and photographic instructions about how to set up a posture, contributed significantly to the precision of asana performance, since yoga at that time was often self-taught. Iyengar’s use of medical-anatomical terminology was also pivotal in the medicalization of asana practice.

Iyengar’s conceptualization of postural yoga was shaped by a scientific discourse that emerged in the nineteenth century, with the related reconsideration of yoga as science (De Michelis Citation2004). Yet the assessment of biomedicine in the colonial encounter was, for various reasons, ambivalent and also created an interest in Nature Cure (see Alter Citation2004; Jansen Citation2016, chapter 2). As Alter shows, Yogendra, Kuvalayananda and other Indian pioneers of the yoga revival were strongly influenced by originally German writings such as Louis Kuhne’s New Science of Healing (Citation1892, German original 1883), available in English and translated in several Indian languages from 1893 onwards (Alter Citation2000, 55–82, Citation2015, Citation2018). These writings were influential in part because of the postulates of Nature Cure itself: (1) the assumption that the human body as a natural organism is able to heal itself, (2) that sickness has to be understood as a sign of unnatural living conditions and alienation, and (3) that ideally the individual could diagnose and treat his or her body (Alter Citation2015, 12, 15, Citation2018). Additionally, the countercultural spirit of German Nature Cure as a tool to empower the common people, closely linked to a romantic sense of belonging and patriotic feelings, offered an ideology suited for appropriation in Indian anticolonial activism – prominently in case of Gandhi and his politics of swadeshi (self-sufficiency) (see Alter Citation2000, 69, Citation2015, 7, 12; Jansen Citation2016, 34–35). So finally, Alter argues, Nature Cure became a kind of template through which postural yoga was modernized and medicalized (Alter Citation2000, Citation2015, Citation2018). Since the 1920s, it became ‘virtually impossible to distinguish yoga therapy from naturopathy’ (Alter Citation2000, 56), a nexus finalized by the development of respective curative regimes and clinics.Footnote9

All the same, the presumed concept of the body in this new yogic aid to improve health resembled the biomedical fragmentation of the human organism, and thus contemporary anatomical and physiological jargon became the diagnostic vocabulary of the naturopathic yoga healer. The performance of asanas, and also breathing techniques, came to be prescribed analogously to a medical treatment. This discursive pattern can be found in the work of several pioneers of modern yoga. Yogendra, for instance, explained: ‘The posture-dosage can then be regulated or prescribed with scientific precision to meet specific requirements of both the students and patients’ ([1931] Citation1952, 277, emphasis added). Similarly Kuvalayananda prescribed asanas as a health cure; his most famous patient was Gandhi in 1927 (Goldberg Citation2016, 97). In 1924 Kuvalayananda had founded a research laboratory to verify scientifically the health benefits of yoga. His findings resulted in the publication of a yoga manual that introduced the asana repertoire in the didactic form familiar today, with step-by-step instructions on performance and comments on each posture’s benefits differentiated as ‘cultural advantages’ (referring to physical culture, i.e. bodily cultivation) and ‘therapeutical advantages’.Footnote10 Being a medical autodidact Kuvalayananda was fascinated by contemporary discoveries and hype about endocrine glands and their functions and by findings on cell theory that date from nineteenth-century human physiology (see Goldberg Citation2016, 76). It seemed that the intense bends, twists and positional changes common in postural yoga could, by altering internal pressure and blood flow, stimulate hormone production, improve organ function and increase brain activity. Headstand (sirsasana) and shoulderstand (sarvangasana) were regarded as possessing particular healing powers.Footnote11 Fifteen years later Sivananda, a former biomedical physician who had devoted his life to yoga, recommended the shoulderstand be performed as ‘a good substitute for modern thyroid treatments’, preferably ‘twice daily’ ([1939] Citation1959, 50). Like several of his contemporaries, Sivananda favoured naturopathy and treated common ailments with a selection of roughly 15 asanas, plus a few additional yogic exercises. He considered that the bow pose, for instance, ‘energized’ digestion, relieved ‘congestion of the blood in the abdominal viscera’, cured several gastro-intestinal disorders and rheumatism ([1939] Citation1959, 56). As I shall argue in the following section, Sivananda was also pivotal for his reference to a Vedanta view on the human organism.

The formulaic reference to an asana’s efficacy, however, is not a modern invention (Birch Citation2018, 45–47). Some eighteenth century hatha yoga manuscripts include standardized phrases promising, along with soteriological benefits, the prevention of disease. Certain postures (and even so, specific cleansing, contraction and breathing techniques) were said to remove ‘fever’, ‘swelling’, ‘phlegm evils’, ‘hunger’ and, much more frequently, ‘any disease’, ‘age’ and ‘death’.Footnote12 However, the intention behind these claims was very different from those underlying systematic modern yoga therapeutics: it was to acknowledge the mundane benefits of a spiritual discipline transmitted among adepts, among whom the goal was perfecting the metaphysical or transcendental yogic body, and disease was regarded as an obstacle to this goal. These manuscripts addressed religious disciples rather than ordinary people or professional healers. Before the twentieth century yoga was in no sense a common practical aid to recovery or improvement of the human physique (Alter Citation2000, 57). Although asanas were described in pre-modern literature as affecting health, they were not conceptualized within a regime of treatment (Birch Citation2018, 47, 63).

Given this history, the fact that today yoga practitioners in search of therapeutic help seemingly without question consider the health effects of yoga in terms that single out and emphasize the benefits of individual asanas and tend to view yoga postures as a kind of curative inventory is, I argue, a remarkable feature of the health imaginary constructed in and by popular yoga discourse. The idioms in which yoga’s health effects are most often expressed have parallels in the field of focused muscle training common in physiotherapy and in certain sports, from the beginning of the twentieth century onwards.Footnote13 This structural similarity was most likely the reason why the early therapeutic reclassification of yoga concentrated on posture practice rather than related techniques such as breath control or the irrigation of body orifices. Yet, to my knowledge, the specific therapeutic benefits of any individual asana have not been demonstrated in scientific research.Footnote14 Rather, modern yoga practice – and therefore any clinical studies of it – is based on a series of postures; such practice includes loosening, stretching and breathing exercises, pre-modern asanas as well as recent additions to the repertoire (see Hauser Citation2013a, 13–15). Furthermore, a yoga course may include Om chanting, visualization and other elements specific to a particular yoga school or tradition. It is therefore impossible to draw therapeutic conclusions about isolated elements such as the effects of a distinct posture. The complex mechanisms underlying the reported effects of yoga-based practices are still subject to research.Footnote15 However, the claim for scientific evidence by itself can be seen as an element of yoga’s health imaginary, similarly to the relevance of personal self-assessment and experience as proposed by the framework of Nature Cure.Footnote16

A health imaginary projecting asanas suitable for each and every health problem – ready for self-medication – also correlates with the central tenets of late modernity: the individual as proactive agent must shape and care for his/her body; the hegemony of biomedical discourse; health as a social site for framing and negotiating notions of well-being; lifestyle, and human improvement. Basic to this new health consciousness is the belief in the attainment of better health through enhanced self-care (Ziguras Citation2004, 2). The elaborated discourse on the health benefits of postural yoga both reflects and (re-)creates this self-help ideology whereby the individual is almost magically bestowed with the power of self-transformation. Whereas this understanding of self and self-care was first recognized in respect to European and Anglo-American society, the present discourse circulates on a global scale and also catches the Indian middle and upper class.Footnote17

It is an ironic feature of ‘holistic’ mind-body medicine that in the last few decades the utilitarian approach to asanas has been expanded to include claims about their mental health effects, in an apparent refinement of the desire to intervene in bodily processes to improve individual lives. Seemingly, some yoga teachers now differentiate asanas according to their emotional or psychological benefits. According to a manual of the long-established German association of yoga teachers (BDY), any yoga exercise would help one ‘to learn something about one’s self’ (Trökes [1991] Citation2007, 115). For instance, asanas requiring good physical coordination are described as enhancing emotional ‘balance’ and ‘strength’, while an inverted posture encourages ‘new perspectives’:

‘To perform an inverted posture also means to relinquish deep-rooted behaviours like, for instance, workaholism, hectic rush, eating disorders and so on, and to try out something completely new. This serves to encourage … other priorities in regard to caring for one’s self, interacting with fellow human beings and the environment (Author translation).’Footnote18

No doubt, body posture and emotions mutually influence each other, but to understand a particular asana as a tool to bring about a distinct emotional state – and possibly a lasting change of awareness – presumes once again an overly simplistic and mechanistic understanding of human beings. This association of posture and emotion possibly stems from the German term Haltung, which translates both as ‘posture’ and ‘attitude’. At any rate, it has long been a common trope in yoga discourse that performing asanas implies or entails something more than doing gymnastics or sports. This rhetoric hints at yoga’s associated liberating and transcending capacity – at distinct mental states seen as indicative of spiritual development such as a sense of equanimity or inner peace. By contrast, conceiving of singular asanas as means of manipulating emotions seems to be a fairly recent addition from New Age healing (see Hanegraaff Citation2007, 33). With respect to Iyengar, yoga historian Goldberg (Citation2016, 435, chapters 33–35) assumes that theorizing on the psychological side effects of asanas began only in the 1980s, a development that Goldberg regards as an effort to re-spiritualize postural yoga. I return to this point later.

Let me now turn to the application and (re-) creation of the health imaginary in contemporary yoga therapy and explore the role of asana practice in two different curative settings. In this process I will show how current assumptions about yogic healing incorporate explicitly Indian/Hindu concepts of aetiology and the body, a development generating new ways of rationalizing the therapeutic effectiveness of asanas.

Asanas in a clinical setting

In present-day India several types of clinical institutions offer yoga therapy, commonly in connection with naturopathy and Ayurveda (Alter Citation2004, Citation2015, Citation2018; Hoyez Citation2011; Jansen Citation2016). The following example concerns Arogyadhama – literally: ‘health home’, – an inpatient residential sanatorium with 250 beds in the outskirts of the modern metropolis Bengaluru (Bangalore). It is managed be (S)VYASA, a registered charitable organization that emerged in 1986 from the Hindu-nationalist Vivekananda Kendra movement and also accommodates a research laboratory and a ‘Yoga University’ (since 2002), attached to the clinic.Footnote19 With regard to the Indian medicalization of yoga, (S)VYASA is a comparatively recent player. It is was founded and is presided over by H. R. Nagendra, a graduated Mechanical Engineer who after an international career turned to yoga. He was pivotal in the canonization and implementation of the ‘Common Yoga Protocol’, a mandatory course structure used for the nationwide mass celebration of the International Yoga Day established in 2015.Footnote20 Apparently he is also the personal yoga advisor of the current Indian prime minister.Footnote21

Arogyadhama advertises yoga therapy as ‘very effective holistic treatment’ for a variety of ‘modern NCDs’ (non-communicable diseases):

‘Epilepsy, Migraine, Parkinson’s, Muscular dystrophy, Cerebral Palsy, Multiple sclerosis, Mental retardation, Bronchial Asthma, Nasal Allergy, Chronic Bronchitis, High PB, Low BP, Heart Disease (CAD), Anxiety, Depression, Psychosis, OCD, Arthritis, Back Pain, Spondylosis, Disc Prolapse, Diabetes, Gastritis, Peptic Ulcer, Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), Ulcerative Colitis, Obesity, Thyrotoxicosis, Short Sight, Long Sight, Astigmatism, Squint, Early Cataract, Glaucoma.’Footnote22

Patients can book in by the week (commencing each Friday) and the majority choose a one-week treatment. Individual fees vary according to the accommodation and treatment package selected. Sometimes a longer stay is required; 30 beds are reserved for cancer patients. Over twelve months from April 2013, 2292 people consulted Arogyadhama, mostly with spinal disorders, metabolic or rheumatic complaints (VYASA. Citation2014, 15). Whoever seeks help at the clinic is considered a ‘therapy participant’. After an initial case assessment on the basis of medical records, patients are assigned to one of the following sections: (1) neurology/oncology, (2) pulmonology/cardiology, (3) psychiatry, (4) rheumatology, (5) spinal disorders, (6) metabolic disorders, (7) gastroenterology, (8) endocrinology, and (9) promotion of positive health. An interdisciplinary team of nine doctors with allopathic and other degrees (Ayurveda, Naturopathy, Yoga) attend to the patients’ needs. The medical director is R. Nagarathna, Nagendra’s sister, who received her medical training in the UK. There is a dispensary on the premises for patients require additional medication.

In contrast with its clinical protocols, the daily schedule at Arogyadhama follows the conventions and rules of a Hindu ashram: a wake-up call at 4:30 am, followed by collective meditation, breathing techniques, asana classes, recitation of the Bhagavad Gita, lectures on spiritual topics, singing of devotional songs, and so on up to 9:30 pm. In between their scheduled therapy sessions, participants follow a healthy diet, and can see a doctor (vital signs are measured daily), watch a video on yoga’s health benefits, have an Ayurvedic massage, or take a naturopathic mud bath. Asanas are taught within each medical section, twice or trice daily for one hour.Footnote23 In short, spiritual and Hindu practices constitute major parts of the daily routine, mostly provided at the clinic’s own prayer hall. A starting (1) and a closing (2) prayer are also integral to each asana session, the opening prayer varying according to the type of disease, and the closing prayer is usually the same. I quote here from a schedule to prevent and treat type 2 Diabetes mellitus:

(1) ‘From ignorance, lead me to truth, from darkness, lead me to light,

From death, lead me to immortality, Om, peace, peace peace.’

(2) ‘Let all be happy, let all be free from diseases.

Let all realize the self, let none be distressed, Om, peace, peace, peace.’Footnote24

The spoken verses are in Sanskrit and originate in the Upanishads (dating from circa 500 BCE). Towards the end of an asana session therapy participants also make a resolution or state an intention. This implies an affirmative phrase, e.g., ‘I am completely healthy’, or ‘I shall never give up’, conceptualized as sankalpa, a self-commitment commonly spoken in a ritual context (see Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2014, 37, 164).

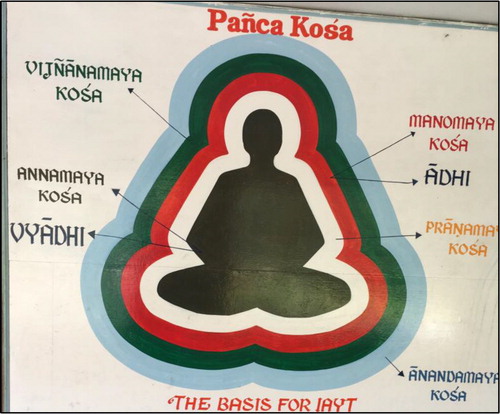

This combination of religious elements with asana practice corresponds to a particular understanding of the human body and of disease development, its core being a five-layered body-concept gradually popularized in the realm of yoga therapy. In line with this, at Arogyadhama the human being is conceived in terms of five ‘sheaths’ (kosha) or existential dimensions that constitute the body: (1) the physical sheath or material body sustained by food (annamaya kosha), (2) the energetic body made of breath and other vital flows (pranayamaya kosha), (3) the mind body (manomaya kosha), a kind of ‘mental and emotional library’, (4) the wisdom sheath/body shaped by the intellect (vijnanamaya kosha), and (5) the bliss sheath (anandamaya kosha).Footnote25 A mural in the clinic yard suggests that each kosha is imagined like another exterior layer, of increasing subtlety in ascending order, and projecting a human being with a multi-coloured halo-like aura ().Footnote26 The outermost sheath describes the highest quality of human life, a desirable state of complete harmony and health that implies transcendence:

Figure 1. Mural at the clinic yard, depicting the five sheaths (pancha kosha) of human existence (photo: Hauser 2017).

‘This is the most subtle aspect of our existence which is devoid of any form of emotions; a state of total silence – a state of complete harmony, and perfect health… to realise and live in this blissful state under all circumstances is the goal of life.’Footnote27

The origin of disease is located at the intermediate mind sheath (manomaya kosha): bad thoughts, anxiety, worries, pain and suffering that cause ‘emotional imbalance’. This critical view on sentiments is common in Hindu thought, because emotions symbolize worldly attachment, and if untreated emotional imbalance disturbs energetic flow (the vital sheath). Corrupted breathing habits may then adversely affect the physical sheath (annamaya kosha) and contribute to the somatization of an initial disorder in the form of a disease (Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2016, 25–29). The theory of the five sheaths therefore explains why some diseases cannot be cured by biomedicine alone. Conversely, yoga therapy should not result in physical and emotional ease but – by means of spiritual self-education (refining the wisdom sheath) – help to achieve tranquillity, associated with Patanjali’s fourth-century understanding of yoga as the ‘cessation of the modifications of mind’ (Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2015, 3).

Reference to the five-kosha model is not limited to Arogyadhama but theorised in various streams of modern yoga, with different conclusions. According to yoga historians Mallinson and Singleton (Citation2017, 184) its current significance is remarkable, since the five koshas are hardly mentioned in pre-modern yoga manuscripts. Birch (Citation2018, 30), who assessed 42 yoga manuscripts from the eleventh to the nineteenth century, found only one reference to the kosha, given in a quotation from an Advaitavedanta text. Rather, the model can be ascribed to the Taittiriya Upanishad 2.1-5 (ca. 500 BCE), reshaped in a Vedanta perspective about a millennium later (Samuel Citation2013, 34). Mallinson and Singleton assume that it was only during the late nineteenth-century revival of Vedanta philosophy that the idea of the five koshas became more closely linked with yoga, competing with earlier metaphysical (tantric) notions of the body formed by channels (nadis), points of focus (chakras) and the vital force (kundalini). Eventually Sivananda ([1939] Citation2000, 1952) integrated the five-kosha model with his particular way of conceptualizing postural yoga (Mallinson and Singleton Citation2017, 491). In contrast to (S)VYASA, Sivananda assumed that the subtlety of the sheaths increases inwards, with the ‘soul’ (atman) at its centre.Footnote28 According to his view, the five sheaths correlated with another pre-modern Hindu concept of three bodies, addressed by Sivananda in theosophically-shaped terms as ‘gross’, ‘astral’ and ‘causal’ body (the middle subtle body made of vital, mental and intellectual sheaths) – a common trope in New Age healing. Footnote29 Sivananda’s disciple Vishnu-devananda disseminated this vision of the five sheaths and included the theory in his Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga (Citation1960). However, neither Sivananda nor Vishnu-devananda mentioned that asanas might function as a tool to manipulate these sheaths of human existence. In 2005 Iyengar devoted an entire book on the five koshas with chapters theorizing the impact of each sheath for spiritual realization. In Iyengar’s view, disease is avoided by achieving ‘harmony’ between these sheaths, rather than by overcoming the lower koshas (Iyengar Citation2005, 4–5). Moreover, Iyengar (Citation2005, 267–270) regards asana practice as instrumental to emotional stability – i.e. to the mind sheath – a view consistent with the trend discussed towards the end of the first section of this paper. In recent yoga therapy manuals the Vedanta notion of the five koshas has been developed into full-fledged ‘yogic’ theories on aetiology and health (see, for instance Majewski and Bhavani Citation2020). However, let us return to the Indian clinic and see which therapeutic conclusions they draw from the five-kosha model.

At Arogyadhama the kosha model is linked to another popular pre-modern concept: the distinction between ‘stress born’ and ‘non-stress born’ diseases (Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2016, 11, 32–33, see Majewski and Bhavani Citation2020, 31). The first type of disease (adhiya vyadi) is defined by adhi, literally: pain, grief, and in a figurative sense ‘suffering’ or ‘illness’. This typology is ascribed to the Yogavasishtha (ca. 900–1200 CE), a medieval source that alludes to contemporary ways of conceptualizing human existence and disorder. At Arogyadhama, adhiya vyadi is used as a synonym for ‘chronic disease’, ‘psychosomatic disorder’, ‘non-communicable disease’, ‘life-style disease’ and ‘stress-related disorder’. The Sanskrit concept thus serves as an umbrella term for various types of modern, biomedical classifications, as if ‘the sages’ already anticipated today’s health challenges, suggesting the timelessness and superiority of ‘ancient Hindu knowledge’. In (S)VYASA’s publications, adhi is freely linked to biomedical treatment logics, anatomical explanatory models and terminology (see, for instance, Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2016, 24). In the treatment logics described, adhi-caused diseases constitute the major field of yoga therapy and biomedical expertise is duly acknowledged for its share in achieving curative success.

In accordance with the five-kosha model and the crucial role of adhi in the development of disease, yoga is regarded as the ultimate method to treat every aspect or ‘sheath’ of a suffering person. In this sense yoga is regarded as holistic: asanas, diet and purification techniques serve the physical sheath; controlled breathing influences the vital sheath; meditation and devotional songs improve the mind sheath; spiritual lectures and the study of the Bhagavad Gita strengthen the wisdom sheath, and meditation and selfless action (karma yoga) consolidate the bliss sheath. From a Hindu viewpoint all these elements constitute yoga. Furthermore, the research section of (S)VYASA has developed five kosha-specific therapeutic formats constituting an ‘Integrated Approach to Yoga Therapy’ (IAYT). For instance, the ‘Pranic Energization Technique’ (PET) improves the energetic sheath; it includes a specific combination of prayers, breath regulation, hand gestures (mudra), visualization and self-monitoring with the resolution to convalesce (Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2014, 130–144). Acknowledging the significance of evidence-based medicine, clinical trials have surveyed the efficacy of these curative approaches and the results have been published in various scientific journals and listed in global medical databases.Footnote30

In this understanding of yoga therapy, asana practice at Arogyadhama serves as an entry into the healing process. Although each medical section teaches its specific asana routine, there is little emphasis on differentiating their respective functions. Unlike the yoga pioneers mentioned in the first section, Nagarathna, the medical director, and Nagendra, (S)VYASA’s founder and president, claim that ‘yoga therapy is not organ specific but it is a science that works holistically to strengthen the inner being’ (Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2016, iv). Spiritual practices are instrumental in this process. Consequently, (S)VYASA interprets – and expands – the WHO definition of health as ‘complete physical, mental, social and spiritual well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2015, 19, emphasis added). So at Arogyadhama the goals of yoga therapy are far-reaching and have several moral implications. The desired transformation refers to changes in life-style – to regular prayers, devotion, Om chanting, Bhagavad Gita recitation and daily yoga – to stabilize the mind (sheath) and as panacea in stress management. This appeals not only to particularly pious health seekers but also attracts technology-oriented middle-class Hindus whose career and life-style may not encourage religious practice but who are regularly exposed to advertisements from various healthcare providers – India’s healthcare sector being based predominantly on private institutions and funding. As mentioned in regard to naturopathy as a template to make yoga a practical aid in health care, the Gandhian idea of Indian self-sufficiency, if not patriotism, might also contribute to Arogyadhama’s attraction.

Asanas as part of a mind-body cure

The five-kosha model is also relevant for some yoga practitioners in Germany, but on the basis of a slightly different interpretation. Yoga Vidya, a charitable organization with 80 franchises nationwide, is one of the largest providers of postural yoga in Germany. Founded in 1992 by Volker ‘Sukadev’ Bretz, a former ordained monk in the lineage of Sivananda, with the self-declared aims of ‘national education’ (Volksbildung) by means of yoga and the ‘promotion of religion’,Footnote31 Yoga Vidya has developed its own brand and curriculum, providing courses at an average price level.

Additionally, Yoga Vidya offers yoga therapy, first and foremost at Bad Meinberg, a sleepy spa town at the edge of the Teutoburg forest. In regard to this location, one could claim that asana-practice-turned-into-naturopathy in India has been (re-)integrated in German Bäderkultur (spa culture). There, in 2003, the organization purchased a former sanatorium and converted it into ‘the largest yoga ashram beyond India’ (Yoga Vidya Citation2017, 2). The building complex is indeed enormous. The transformation of the central construction – designed in the 1970s with seven step-wise arranged upper floors – to a spiritual yoga retreat was accompanied by renaming it ironically and affectionately as a ‘chakra pyramid’. The interior has been restyled in bright warm colours with natural materials, plants and fresh flowers. It is light-filled and simply furnished with meditation cushions and armchairs in some areas, and decorated here and there with symbols of Hindu and New Age religiosity. Against the German background these aesthetics create a specific therapeutic space – an environment that evokes feelings of caring, intimacy and contemplation. This ensures an experience that contrasts with standard clinical settings and with the luxuries of a spa and wellness hotel. This atmosphere is enhanced by the obligatory daily routine typical of a Hindu ashram. Though in comparison very moderate, for Germans it requires considerable personal commitment since attendance in meditation sessions is mandatory (e.g., at 7 am), food is provided only twice daily, and residents are asked to contribute to housekeeping. In 2017 the ashram had a capacity of approximately 600 beds and reportedly offered yoga classes and therapy to 90,000 people (residential and daytime visitors).Footnote32 Visitors were looked after by 180 ‘sevakas’, Yoga Vidya community members who are permanent residents, remunerated by a monthly allowance.

Yoga Vidya offers yoga therapy in the format of three to seven-day ‘seminars’ promoted in a special yearly catalogue.Footnote33 Each seminar addresses a particular (mental) health issue, to be treated by either ‘body-focused’ or ‘psychological’ yoga therapy, i.e. asana theory and training (90 minutes twice a day), completed by respective health information and/or personal counselling. There are approximately 60 instructors, some of them residential, with various qualifications mainly in the fields of alternative medicine, physiotherapy, psychology and spiritual disciplines. In 2018 Yoga Vidya advertised a total of 107 seminars: 86 of them at Bad Meinberg, again 59 classified as body-focused and indexed as follows:

yoga for head, shoulders and neck 6 seminars

yoga for back pain 13 seminars

yoga for joints and rheumatic disorders 6 seminars

yoga for the respiratory system and metabolism 2 seminars

yoga for internal organs 4 seminars

yoga for relaxation from stress 11 seminars

yoga-harmonization of hormonal effects and metabolism 2 seminars

yoga for the chakras 6 seminars

purification by means of fasting and other forms of cleansing 9 seminars

The description and scope of the seminars clearly addresses lay ideas about common medical ailments. Visitors book seminars on the basis of personal choice and self-assessment rather than an initial biomedical assessment as in the Indian clinic. This creates some distance from biomedicine and acknowledges the perspective of the patient, who in a medicalized society is familiar with their own biomedical history and, in line with Nature Cure, should know what will best aid their recovery. The body-focused therapy variant also includes more unspecific or more subtle health issues such as stress reduction, harmonious/hormonal balance, energetic flows (‘for the chakras’) and detoxification. In addition, in 2018 Yoga Vidya offered 27 seminars on ‘psychological yoga therapy’. This approach is conceived as deriving from yogic philosophy in synthesis with humanistic psychology, and assumes that human beings have the desire to develop their full potential. Accordingly, seminars are advertised to overcome fear, to increase self-love, self-worth and self-confidence, for personality development and self-transformation. Moreover, psychological yoga therapy is recommended as a coping strategy for ‘internal and external life crises’. The therapeutic nexus is, in one way or another, the self.

At Bad Meinberg yoga therapy is conceptualized as a ‘holistic health-oriented lifestyle-concept for strengthening human self-healing powers’ (Yoga Vidya Citation2017, 4). For this purpose posture practice is crucial, though the emphasis varies between each type of yoga therapy. Asanas are considered instrumental not only for improving physical deficiencies but also to provide energetic, emotional, cognitive and spiritual benefits. This extraordinary power attributed to bodily conditioning is, once again explained with the help of the five-kosha model. Asanas are identified as the means to adjust each of the five human sheaths, in certain specified ways – not only in the physical sheath, as assumed at Arogyadhama. Moreover, the five sheaths are conceptualized in relation to personhood rather than the human body, as if the physical, energetic, emotional, cognitive and spiritual dimension constituted the self (Yoga Vidya Citation2017, 5). Strictly speaking, the Sanskrit terminology serves to refine the classic Cartesian distinction of mind and body rather than overcome it. In the writings of Sivananda and Vishnu-devananada (Citation1960, 18), the declared yogic goal to ‘bring the body under the control of the mind’ reveals perplexing similarity with the Cartesian superiority given to the mind. However, without any further data on the perspectives of residential visitors (patients) and staff (community members) it is problematic to assess whether and how this rhetoric in fact influences and mirrors the health imaginary associated with yoga. At any rate, similar to the Indian clinic, Yoga Vidya employs the kosha-theory as the rationale for its range of therapeutic choices; in this case the revaluation of asanas as a therapeutic device affecting much more than the human physique. At the energetic level, Yoga Vidya claims, posture practice stimulates the seven chakras; this indicates how the concept of the chakras has been integrated as a supportive theory (a feature not limited to this provider of yoga therapy). Sukadev, the founder of Yoga Vidya, explains the impact of asanas on the emotional level (manomaya kosha) in one of his various YouTube-lectures:Footnote34

‘in the course of a yoga class you go through various emotions. When you bend forward you feel something like confidence, release and dedication. When you turn backwards it may cause open-mindedness, pleasure and vastness. […]. By the means of asanas you cultivate all these abilities … when you struggle with an asana you can, to some extent, get access to your emotions. Many people who perhaps at one time suffered from emotional blocks, who were not able to sense their body, or who felt deeply disappointed and experienced joylessness, can by the means of asanas quickly experience pleasure, quickly feel heart opening, quickly experience self-love. Well, on the level of manomaya a lot happens, with regard to self-love, with regard to heart opening, heart opening towards fellow humans and a higher reality’Footnote35 (Author translation).

Analogously, asana practice promises profound and liberating ‘insights’, i.e. a refinement of the wisdom sheath. In Sukadev’s words ‘you may possibly realize the meaning of your life’. Yet the ultimate power of asanas is seen in their capacity to evoke ‘spiritual experiences’:

‘When you perform an asana, it may be that … your mind becomes very calm. It may be that you turn completely inwards, that you get the deep experience of bliss, of joy, of substantial presence, possibly deep inside or as some kind of connection. During deep relaxation or while holding an asana more than a few people have had deep spiritual experiences and allowed themselves to access a deeper dimension of their life’ (Author translation).Footnote36

What exactly constitutes a spiritual experience of this kind remains vague, or is at least not advertised on YouTube. The excessive meanings associated with posture practice, I argue, illustrate a recent spiritualization of body techniques that Sarbacker (Citation2014) and Goldberg (Citation2016) have described in case of other current forms of postural yoga as ‘making yoga sacred again’. Not surprisingly, Yoga Vidya contributes to the systematic differentiation of asanas discussed in the first section. Their online dictionary identifies ‘physical’, ‘energetic’ and ‘mental’ effects for each of the 61 portrayed yoga postures. For example, in addition to its physiological benefits, the bow pose is advertised as activating the ‘sun braid’ (Sonnengeflecht), stimulating the chakras near the navel, heart, throat and eyebrows. Furthermore, this pose is believed to encourage self-confidence, ‘open the heart’ and provide a feeling of sublimity (Erhabenheit).Footnote35

In Yoga Vidya’s yearly catalogue the healing effects of yoga therapy are described in diffuse, ambivalent phrases: ‘new energy and creativity’, ‘resurrection of your energy’, ‘vitality and inner clarity’, ‘inner radiance’, ‘inner peace’, ‘self-love’, ‘emotional balance’, ‘renewed vigour and positivity’, ‘to experience the beauty of life in a more intense way’, ‘to get in touch with your higher self’. Clearly, recovery is understood as healing in a broad if not soteriological sense. Seemingly, yoga therapy serves to boost self-healing in two respects: to heal the inner self (awareness) and to empower the self as an agent of healing (‘be your personal saviour’). As mentioned above, in what respect these phrases mirror and structure the experience of yoga practitioners at Bad Meinberg still needs to be explored. As Ziguras (Citation2004) and Hanegraaff observe (Citation2007, 34), the close connection between health and spiritual growth is indicative of New Age thinking and has significantly influenced post-secular self-care. The discursive link is ensured by psychologization as well as by the process of embodiment. Physical experience, sensual awareness and somatic modes of attention are acknowledged as legitimate channels for personality development. As the science historian Harrington (Citation2009) notes, decoding bodily messages is one of the major concepts that constitute holistic medicine. Thus introspection is crucial and given particular emphasis. Whether yoga therapy is indeed perceived as cathartic recovery or simply as ‘time-out’ is likely to vary; either way, it constitutes a privately financed adjunct to biomedical healthcare, which is in Germany covered by public health insurance.

Conclusions

My aim in this paper has been to identify the implicit logics, beliefs and meanings (ethnotheories) contained within popular discourse and forms of practice. I focussed on yoga therapy in order to access the particular set of socially negotiated ideas about postural yoga that can be described as its health imaginary. The health imaginary of postural yoga projects a particular view of yogic healing that provides meaning for individuals seeking therapy. Similarly those who teach yoga for therapeutic purposes presume a salutary framework in which they situate their care. For methodological reasons I concentrated on asana practice and examined a few of the body concepts circulated by two providers of yoga therapy.

Modern yoga clearly is a cultural hybrid that has emerged in the course of the last 150 years through transcultural encounters in numerous places and of various scales, characterized by selected adoptions, mutual exchange and multiple re-contextualization (De Michelis Citation2004; Singleton Citation2010). To propose, as I do here, a focus on the present-day health imaginary of yoga, and on claimed health benefits in particular, is not to imply any uniform approach to the therapeutic use of asanas, and any attempt to classify the present range of yoga styles and institutes as either spiritual-oriented or body-/health-oriented would be highly problematic. As I have indicated in this paper with two institutional case studies, contemporary therapeutic applications of yoga postures provide exactly the social spaces that invite exploration of how multiple meanings may be invoked and produced, drawing from both Hindu religion and from non-denominational (Neo Vedanta and New Age) spirituality.

This paper has also illustrated that there are some striking differences in how yoga therapy providers relate to biomedicine. In case of (S)VYASA, a range of medical aesthetics, categories, structures and methods are appropriated, while pre-modern Hindu concepts – which have been differently theorized at various points in history – project a vision of a multi-layered human being as the object of yogic healing. Ancient Hindu terminology has been selectively transformed into seemingly coherent, timeless and universal medical language. The five-kosha model and also the category of adhi-induced diseases have been adapted for use alongside present-day biomedical categories and functional descriptions of the human organism. Other aspects of the subtle body, such as kundalini, receive hardly any attention in the contexts examined here. Both biomedicine and what may be labelled as ‘religious therapy’ are closely intertwined and confirm India’s medical pluralism. With regard to current Indian biopolitics, therapeutically applied yoga practice constitutes one option within an extremely wide range of healing possibilities, accompanied by heavily nationalized public representations.

In contrast, Yoga Vidya staff made substantial efforts to convert a former sanatorium building into an ashram that feels nothing like a clinic. Here, the aesthetics and daily regime allude to the field of social care, educational facilities, and possibly psychotherapy. In this environment yoga therapy is associated with complementary and alternative medicine; it is consistent with therapeutic discourse (see Illouz Citation2008) rather than biomedical treatment. This approach also ensures the social acceptance of yoga (therapy), quite different to the 1970s and 1980s when a self-declared ashram in Germany would have raised public suspicion about cultic activities. On the other hand, aspirations towards ‘new energy’, ‘inner peace’, and ‘self-love’ cannot simply be viewed as opposed to medicine or mainstream religion since references to spirituality have meanwhile become part of Germany’s popular culture (see Knoblauch Citation2009). These phrases are ambiguous, simultaneously belonging to the wellness sector and to consumerism, for instance, in the case of marketing teabags with inspirational messages.

Clearly what yoga is and does depends to a large extent on the social and cultural context and related expectations. At any rate, my analysis indicates that those who seek therapeutic help from postural yoga are in effect offered, and may obtain, more than the improvement of their physical or indeed emotional health status. They confront possibilities of healing in a comprehensive way: to reach either an ideal blissful state undisturbed by pain and emotional volatility, or a new quality of body- and self-awareness. In this regard the recent therapeutic application of the kosha-model is indicative of another twist in the medicalisation of postural yoga towards mind-body medicine as shaped by either New Age ideas or Hindu spirituality. Moreover, to meet these comprehensive ends a short-term therapeutic intervention is insufficient and at best provides a first taste of the desired state. The promise of fulfilment requires a fuller change in life-style. This claim and call for long-lasting consequences is significant. It connects the social sites that trust in the powers of yoga therapy, whether in a Hindu-patriotic fashion, presuming an integrated approach to health, or from a New Age perspective. This call for commitment is dressed as a ‘yogic’ attitude of some kind.

As I argued in the first section of this paper on how asanas are conceived as a therapeutic tool, I suggest that the belief in asana practice as a technique of self-monitoring encourages a sense of an individual’s responsibility for his/her own (psycho-)physical health status and implies commitment and endurance. A second perspective is offered in the case study of yoga therapy in India, in that here yoga therapy presumes a different subject position: wellbeing as being grounded in devotion, facilitated by divine grace, and Hindu elements being an addition to biomedical diagnostics. In the third variant explored here, therapeutic yoga points to a specific health consciousness: an increased sensitivity for somatic self-reflection, reframing a continuum of bodily and emotional feelings as signs of healing and growth. Hence engaging in postural yoga for a therapeutic purpose resonates with a variety of distinct health care subjectivities.

What these case studies indicate, then, is that a close look at the health imaginary of postural yoga does not permit any straightforward conclusions about health identities. Whether and to what extent yoga practitioners themselves adhere to the respective bodily and therapeutic categories provided by (S)VYASA and Yoga Vidya, for instance would be a matter for empirical investigation. In any medical environment patients pick up only those expert views, foreign words, and concepts that appear meaningful to them within their personal backgrounds. Apart from the popular narrative of successful yoga healing – a cultural genre of its own (see e.g. Shaw, this issue) – we simply do not know how relevant a (weeklong) yoga treatment is for the individual illness biography. A fundamental insight of medical anthropology is that health seeking behaviour is pluralistic, and it is likely that yoga constitutes just one stage in the course of what has been referred to as ‘healer shopping’ (Kroeger Citation1983) or ‘hierarchy of resort’ (Romanucci-Ross [Citation1969] 1977). The health imaginary is equally contingent in defining communities. Although health-oriented yoga practice may provide reference points for the negotiation of collective identities or a social movement, any conclusions in this regard would require further information about the respective local environments: personal viewpoints, preferred interpretative frames, forms of social distinction, health politics etc.

The ethnotheories presented here are not, moreover, mutually exclusive. Health-related ideas, beliefs, and concepts do not constitute a homogeneous system, but map a shared imaginary space that provides grounds for various forms of rationalizing personal health behaviour, therapeutic approaches, and institutional structures. To speak of this repertoire of floating signifiers as a health imaginary offers a way of linking, analytically, micro-social practices and the production of local meanings with a globally and historically defined network of possibilities. In this way it brings health care realities into social perspective, taking into account a multiplicity of locations, contexts, and peoples, shaped by time and history. Practically, it may enable comparison and thus highlight differences in yoga’s social landscape, indicating, for instance, why yoga is perceived to be beneficial, what exactly it is thought to offer, how this has changed over time, which Sanskrit terms serve as interface for human creativity, and in what respects yoga providers relate to each other.

The health imaginary not only helps circumvent the problematic question of therapeutic truth. Paying attention to the continuum of bodily, emotional, psychological and spiritual aspirations associated with therapeutic yoga also reveals substantial fluidity across these domains, despite the modern dichotomy of the secular (health) versus religion. From the perspectives of social anthropology and the comparative study of religion, this is may be the greatest advantage of the concept: the health imaginary provides an analytic model capable of exploring the fringes of modern categories and social fields. Moreover, the metaphor of the imaginary suggests that there is no superior epistemological standpoint to analyse (trans-) cultural dynamics. Any understanding of yoga (therapy) is situated, and has its own premises, objectives and politics.

Ethical approval

Formal ethics clearance is not required for the analysis of publicly available data.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the volunteers at (S)VYASA who generously shared their time to show me around Arogyadhama and also the adjoining yoga campus. I am grateful to the University of Bremen for the financial support of this research trip in March 2017 and to the DAAD for supporting a conference visit at Oxford. I also want to thank Jason Birch for sharing his thoughts on the development of health assertions in pre-modern yoga manuscripts (and the Jogapradīpyakā in particular) and the two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful and clarifying comments. Above all I really appreciate the support given by Alison Shaw and Esra Kaytaz to shape and refine my arguments, at the conference panel at Oxford, by their wise comments and valuable suggestions on a draft version of this paper, and for their expert corrections during the editing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 I use the term ‘postural yoga’ to emphasize the difference from hatha yoga as described in pre-modern Indian manuscripts (see Singleton Citation2010, 5; Birch Citation2011).

2 For reflections on the heuristic potential of the social imaginary see Traut and Wilke (Citation2015) and Vandenvoordt, Clycq, and Verschraegen (2018).

3 Seemingly, anyone who subscribes to the US-based International Association of Yoga Therapists may obtain a certificate as ‘registered yoga therapist’ (Broad Citation2012, 151). Not surprisingly the abbreviation RYT alludes to professional titles in the medical domain (MD, MBBS or Dr. Med.). See Birch (Citation2018, 56) for the particular way in that yoga therapy (yoga chikitsa) was understood in the eighteenth-century Hatha Pradipika.

4 75% of actual and previous yoga practitioners claimed to have taken up yoga practice in order to ‘improve physical well-being, e.g. in case of back pain’ (n = 68). According to this nationally representative survey (n = 2048), 3,3% of Germans engaged in postural yoga (Cramer Citation2015, see also BDY and GfK Citation2014, 14). Following a market survey in the United States from 2015, the five main reasons given for starting yoga were flexibility (61%), stress relief (56%), general fitness (49%), improve overall health (49%), and physical fitness (44%), see Yoga Journal and Yoga Alliance Citation2016, 19).

5 This feature seems to be common in yoga manuals/classes in the traditions of Sivananda, Iyengar and Bikram.

6 For an anthropological case study on Bikram Yoga see Hauser Citation2013b.

7 Https://www.bikramaltona.de/bikram-yoga/26-übungen, last retrieved 22.10.2019.

8 Here I quote the revised English edition (Iyengar Citation1979, 487–506). The same list is given in the most recent English edition from 2015.

9 From this perspective the present connection of yoga with Ayurveda is a fairly recent addition, not least because of the combined promotion boosted by the Indian ministry AYUSH (see Newcombe Citation2017; Birch Citation2018). See Newcombe (Citation2017) for a related early media discourse in the 1940s.

10 Kuvalayananda [1931] Citation1964. Goldberg (Citation2016, chapter 12) argues that Sundaram deserves credit for the first modern hatha yoga manual and also its didactic pattern. Published in 1929 Yogic Physical Culture or the Secret of Happiness not only adopted Kuvalayananda’s original asana routine but also borrowed his therapeutic assumptions, published since 1924 in his journal Yoga-Mimansa (Goldberg Citation2016, 157–166). Since my interest is in the therapeutic statements I emphasize Kuvalayananda’s contribution.

11 For a contemporary critique of Kuvalyananda’s ‘pseudo-scientific attempts’ see his competitor Yogendra ([1931] Citation1952, 276). On present-day ‘yoga myths’ about asana results see Dalmann and Soder (Citation2016, 164–167), two medical professionals specialized in yoga therapy.

12 Jogapradīpyakā Citation2006, 32–79. For an evaluation of health-related terminology and theory as well as claimed curative applications in yoga manuscripts from the eleventh to nineteenth century see Birch (Citation2018).

13 Goldberg (Citation2016, 39, 92) has pointed to striking parallels between health assertions provided by Kuvalayananda and those made by physical culturists at the early twentieth century. On the semiotic ambiguity of bodily postures see Singleton (Citation2010, 60–63, chapter 4).

14 Apart from, perhaps, Kuvalayananda’s highly speculative articles on shoulderstand from 1924–26 (Goldberg Citation2016, 108).

15 On the assumptions, parameters, components and prospects of medical research on yoga see Schmalzl, Powers, and Blom (Citation2015).

16 I wish to thank an anonymous reviewer for Anthropology and Medicine for pointing to the impact of scientific proof as a discursive trope in the health imaginary (see Alter Citation2004; in regard to naturopathy see Jansen Citation2016, chapter 3).

17 See, for instance, an article in the magazine India Today: ‘6 Asanas for a Healthy Body and Mind that should be part of your New Year Resolution’, published in December 26, 2016 (https://www.indiatoday.in/lifestyle/wellness/story/6-yoga-asanas-healthy-body-mind-new-year-resolution-2017-fitness-goal-ira-trivedi-lifest-359566-2016-12-26, last retrieved 22.10.2019).

18 Trökes [1991] Citation2007, 134.

19 (S)VYASA stands for (Swami) Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana (Swami Vivekananda Yoga Research Foundation). On the role of yoga in the Vivekananda Kendra movement see Beckerlegge (Citation2014), for a brief account of (S)VYASA from the 1990s see Strauss (Citation2002, 244–245).

20 Ministry of AYUSH Citation2016, viii. This protocol was preceded by a similar schedule provided for the national Stop Diabetes-campaign.

21 See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._R._Nagendra (last retrieved 22.10.2019).

22 Advertisment in Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2014.

23 The time any individual patient spends on asana practice varies according to their booked treatment package. The daily meditation program also includes primary (seated) asanas.

24 Prayer titles mentioned in the Common Yoga Protocol for T2DM, published in S-VYASA’s monthly journal Yoga Sudha, November 2016; English translation of the original Sanskrit prayer text from Nagarathna and Nagendra (Citation2014, 128–129).

25 Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2014, 47–52; Citation2016, 25–31. The term kosha may indicate a ‘sheath’, ‘layer’ and also a bodily ‘container’.

26 This visualisation is possibly influenced by the reception of Kirlian photography, popular in complementary and alternative medicine (see Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2016, 25).

27 Nagarathna and Nagendra Citation2016, 31, 116 (emphasis added).

28 Sivananda [Citation1939] Citation2000, 61, Citation1952; Vishnu-devananda 1960, 14–17.

29 Clearly, more research is needed on the Theosophical Society as a multiplier of bodily theories. On theosophical notions of the body and their transcultural adaption see Johnston Citation2012; on notions of the subtle body in pre-modern Hindu literature see Samuel Citation2013.

30 For instance, Oswal et al. (Citation2011) conducted a study on PET as an adjunct therapy for healing fresh fractures.

31 Https://www.yoga-vidya.de/netzwerk/yogavidya0/vereinssatzung/, last retrieved 22.10.2019. In addition, Yoga Vidya organizes a variety of teacher training programs.

32 See ‘Entspannt durch ein Vierteljahrhundert’, in Lippische Landeszeitung, May 22, 2017, p. 26.

33 The following information is taken from Yoga Vidya Therapie 2018. Psychologische & Körperorientierte Yoga-Therapie, published in 2017.

34 Since 2007 Yoga Vidya runs its own yoga channel on YouTube with 1,171 videos and more than 45.000 subscribers (22.10.2019).

35 Lecture YVS079 (11:19 – 13:09), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JBwtas-Hp-Q, last retrieved 22.10.2019).

36 ‘Lecture YVS079 (14:27 – 15:02), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JBwtas-Hp-Q, last retrieved 22.10.2019).

37 Https://www.yoga-vidya.de/yoga-uebungen/asana/bogen-284/, last retrieved 22.10.2019.

References

- Alter, Joseph S. 1997. “A Therapy to Live by: Public Health, the Self and Nationalism in the Practice of a North Indian Yoga Society.” Medical Anthropology 17 (4): 309–335. doi:10.1080/01459740.1997.9966144.

- Alter, Joseph S. 2000. Gandhi’s Body: Sex, Diet, And the Politics of Nationalism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Alter, Joseph S. 2004. Yoga in Modern India: The Body between Science and Philosophy. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Alter, Joseph S. 2005. “Modern Medical Yoga. Struggling with a History of Magic, Alchemy and Sex.” Asian Medicine 1 (1): 119–146. doi:10.1163/157342105777996818.

- Alter, Joseph S. 2014. “Shri Yogendra: Magic, Modernity, and the Burden of the Middle-Class Yogi.” In Gurus of Modern Yoga, edited by Mark Singleton and Ellen Goldberg, 60–79. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Alter, Joseph S. 2015. “Nature Cure and Ayurveda: Nationalism, Viscerality and Bio-Ecology in India.” Body & Society 21 (1): 3–28. doi:10.1177/1357034X14520757.

- Alter, Joseph S. 2018. “Yoga, Nature Cure and ‘Perfect’ Health: The Purity of the Fluid Body in an Impure World.” In Yoga in Transformation: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Karl Baier, Philipp A. Maas, and Karin Preisendanz, 441–461. Göttingen: V & R unipress.

- Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: The Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Baier, Karl. 2016. “‘Das Evangelium der Entspannung’. Euroamerikanische Entspannungskultur und die Genese des modernen Yoga.” Entspannungsverfahren 33: 45–62.

- BDY (Berufsverband der Yogalehrenden in Deutschland e.V.) und GfK (Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung). 2014. Yoga in Zahlen.

- Beckerlegge, Gwilym. 2014. “Eknath Ranade, Gurus, and Jīvanvratīs: The Vivkananda Kendra’s Promotion of the Yogic Way of Life.” In Gurus of Modern Yoga, edited by Mark Singleton and Ellen Goldberg, 327–350. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Birch, Jason. 2011. “The Meaning of Haṭha in Early Haṭhayoga.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 131 (4): 527–554.

- Birch, Jason. 2018. “Premodern Yoga Traditions and Ayurveda: Preliminary Remarks on Shared Terminology, Theory, and Praxis.” History of Science in South Asia 6: 1–83. doi:10.18732/hssa.v6i0.25.

- Broad, William. 2012. The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. 1975. The Imaginary Institution of Society. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Conrad, Peter, and Meredith Bergey. 2015. “Medicalization: Sociological and Anthropological Perspectives.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, edited by. James D. Wright, 105–109. Amsterdam. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.64020-5.

- Cramer, Holger. 2015. “Yoga in Deutschland – Ergebnisse einer national-repräsentativen Umfrage.” Complementary Medicine Research 22 (5): 304–310. doi:10.1159/000439468.

- Csordas, Thomas. 2002. Body/Meaning/Healing. Houndsmill: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dalmann, Imogen, and Martin Soder. 2016. Heilkunst Yoga. Yogatherapie heute. Konzepte, Praxis, Perspektiven. 2nd Revised ed. Berlin: Viveka.

- De Michelis, Elizabeth. 2004. A History of Modern Yoga: Patañjali and Western Esotericism. London: Continuum.

- Foucault, Michel. [1986] 2012. The Care of the Self. Vol. 3 of the History of Sexuality. New York: Vintage Books.

- Foxen, Anya. 2020. Inhaling Spirit: Harmonialism, Orientalism, and the Western Roots of Modern Yoga. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Goldberg, Elliott. 2016. The Path of Modern Yoga: The History of an Embodied Spiritual Practice. Rochester: Inner Traditions.

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 2007. “The New Age Movement and Western Esotericism.” In Handbook of New Age, edited by Daren Kemp and James R. Lewis, 25–50. Leiden: Brill.

- Harrington, Anne. 2009. The Cure within. A History of Mind-Body Medicine. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Hauser, Beatrix. 2013a. “Introduction: Transcultural Yoga(s). Analyzing a Traveling Subject.” In Yoga Traveling. Bodily Practices in Transcultural Perspective, edited by Beatrix Hauser, 1–34. Cham (Switzerland): Springer.

- Hauser, Beatrix. 2013b. “Touching the Limits, Assessing Pain: On Language Performativity, Health, and Well-Being in Yoga Classes.” In Yoga Traveling. Bodily Practices in Transcultural Perspective, edited by Beatrix Hauser, 109–134. Cham (Switzerland): Springer.

- Hauser, Beatrix. 2018. “Following the Transcultural Circulation of Bodily Practices: Modern Yoga and the Corporeality of Mantras.” In Yoga in Transformation: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Karl Baier, Philipp A. Maas, and Karin Preisendanz, 507–528. Göttingen: V & R unipress.

- Hoyez, Anne-Cécile. 2007. “The ‘World of Yoga’: The Production and Reproduction of Therapeutic Landscapes.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 65 (1): 112–124. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.050.

- Hoyez, Anne-Cécile. 2011. “Health, Yoga and the Nation: Dr. Karandikar and the Yoga Therapy Centre, Pune, Maharashtra.” In Cultural Entrenchment of Hindutva, edited by Daniela Berti, Nicolas Jaoul, and Pralay Kanungo, 145–160. New Delhi: Routledge.

- Illouz, Eva. 2008. Saving the Modern Soul: Therapy, Emotions, and the Culture of Self-Help. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Iyengar, Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja (with John J. Evans and Douglas Abrams). 2005. Light on Life: The Yoga Journey to Wholeness, Inner Peace, and Ultimate Freedom. Emmaus: Rodale Books.

- Iyengar, Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja. 1979. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Revised ed. New York: Schocken Books.

- Jain, Andrea. 2010. “Health, Well-Being, and the Ascetic Ideal: Modern Yoga in the Jain Terapanth." PhD diss., Rice University.

- Jansen, Eva. 2016. Naturopathy in South India: Clinics between Professionalization and Empowerment. Leiden: Brill.

- Jogapradīpyakā of Jayatarāma. 2006. Critically edited by Swāmī Maheśānanda, B. R. Sharma, G. S. Sahay, and R. K. Bodhe. Lonavla: Kaivalyadhama S.M.Y.M Samiti.

- Johnston, Jay. 2012. “Theosophical Bodies: Colour, Shape and Emotion from Modern Aesthetics to Healing Therapies.” In Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production, edited by Carol M. Cusack and Alex Norman, 153–170. Leiden: Brill.

- Knoblauch, Hubert. 2009. Populäre Religion: Auf dem Weg in eine spirituelle Gesellschaft. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Kroeger, Axel. 1983. “Anthropological and Socio-Medical Health Care Research in Developing Countries.” Social Science & Medicine 17 (3): 147–161. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(83)90248-4.

- Kuhne, Louis. 1892. The New Science of Healing: Or, the Doctrine of the Oneness of All Diseases Forming the Basis of a Uniform Method of Cure, without Medicines and without Operations. An Instructor and Adviser for the Healthy and the Sick. New York: International News Co.

- Kuvalayananda, Swami (Jagannath Ganesh Gune). [1931] 1964. Âsanas. Popular Yoga. Bombay: Popular Prakashan.

- Majewski, Lee, and Anand Bhavani. 2020. Yoga Therapy as a Whole Person Approach to Health. London: Singing Dragon.

- Mallinson, James, and Mark Singleton. 2017. Roots of Yoga. Milton Keynes: Penguin.

- Ministry of AYUSH. 2016. 21st June International Day of Yoga. Common Yoga Protocol. 2nd revised ed. Delhi: Ministry of AYUSH.

- Nagarathna, Raghuram, and Hongasandro Ramarao Nagendra. 2014. Yoga for Cancer. Bangalore: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana.