ABSTRACT

Given that online platforms disrupt established industries and challenge existing institutions, they can only be successful if their innovation becomes both legal and legitimate. This requires ‘institutional work’ that changes perceptions and regulations within society. Rather than only focussing on the online platform as the sole agent engaging in institutional work, our study analyses institutional work as a collective process. We investigate the case of home-sharing platform Airbnb and the process of institutional change its introduction prompted regarding short-term rental in Amsterdam, London and New York. We find, contrary to the popular view of online platforms as disruptive entrepreneurs, that the platform mainly focusses on creating new institutions rather than disrupting existing ones, and that users and non-users undertake most of the institutional work activities. We also show that different types of actors carry out different types of institutional work suggesting that the process of institutional work is highly distributed.

1. Introduction

In the past few years, online platforms that enable peers to interact and transact have experienced a considerable growth (Kenney and Zysman Citation2016). In many sectors, peers supply goods and services through platforms at lower prices than professional firms, thus disrupting traditional business models (Acquier, Daudigeos, and Pinkse Citation2017; Constantiou, Eaton, and Tuunainen Citation2016; Kenney and Zysman Citation2015). Notably, Uber altered the taxi market and Airbnb the hospitality industry, while more recently platforms also entered other sectors including restaurants, parking, car rental, logistics, cleaning, handymen, babysitting, tutoring and healthcare.

In the case of online platforms, disruption does not only involve a change in business models and industry structure, but often also in the regulatory regime. Peers transacting through the platform regularly do not adhere to industry regulations, while the platform typically refrains from enforcing such regulations even if they have data to do so (Edelman and Geradin Citation2015), leading to a legal grey area (Brail Citation2017; Ranchordas Citation2015). However, the platform business model can ultimately only be successful if its new services are not just embraced by consumers, but also by other actors in the platform ecosystem, regulators and society at large (Kenney et al. Citationforthcoming).

As practices on platforms turn into popular and taken-for-granted activities, there is a growing need to adapt regulations. ‘Turning a blind eye’ becomes increasingly unaccepted while enforcing through old regulations becomes infeasible due to the sheer number of peers active on platforms. Instead, processes of institutionalisation have occurred leading to new regulations meant to contain the novel peer-to-peer practices, with diverse outcomes and effects in different countries and sectors.

Our study looks at the institutionalisation of Airbnb as the world’s largest home-sharing platform in the context of three world cities: Amsterdam, London and New York City. In our analysis, we use the sociological notion of institutional work, which has been defined as ‘the purposive action of individuals and organizations aimed at creating, maintaining and disrupting institutions’ (Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006, p. 214). Institutional work comes from institutional theory that aims to transcend the contrast between structure and agency (Seo and Creed Citation2002). Through institutional work activities such as framing, lobbying and allying, actors actively try to change institutions while still being embedded within institutions. Such actors have been called institutional entrepreneurs (Battilana, Leca, and Boxenbaum Citation2009).

In the context of the rise of home sharing as a common commercial practice, Airbnb can be considered as a typical institutional entrepreneur who disrupts not just the hospitality industry, competing with regular hotels as a partial substitute (Zervas, Proserpio, and Byers Citation2017; Uzunca and Borlenghi Citationforthcoming), but also upsets local housing regulations. They follow an institutional strategy that is typical for online platforms, summarised as: ‘don’t ask permission, ask forgiveness’ (Kenney and Zysman Citation2016). Put differently, platforms first launch their platform in search of a critical mass of users. Once a user base is established, they point to a platform’s popularity in regulatory battles and sometimes even mobilise their users in political campaigning. Their popularity among users, then, provides platforms with a credible source of legitimacy and even inevitability, which strengthen their negotiation power as well as their pleas for permissive regulation (Frenken and Schor Citation2017). These tactics make clear that platforms, including Airbnb, do not act alone, but involve the peers who use the platform. This leads us to the question to what extent and in what ways the institutionalisation of online platforms is, in fact, a collective endeavour (Jolly and Raven Citation2015). Answering this question will not only clarify the role of peers in institutional work, but also of institutional defenders – including non-users – who oppose a platform and try to block permissive regulations (Dorado Citation2005; Lakshman and Akhter Citation2015).

Our study contributes to the study of institutional change in two ways. First, digital platforms are in themselves novel phenomena. The emergence and success of these services has been studied from different perspectives, such as business model choice (Hagiu and Wright Citation2015), modes of exchange (Scaraboto Citation2015), trust and repurchase intention of users (Liang, Choi, and Joppe Citation2018a, Citation2018b), and accessibility and control of platforms (Boudreau and Hagiu Citation2008). However, how institutions shape and can be shaped by digital platforms has not yet been thoroughly investigated (Mair and Reischauer Citation2017; Uzunca, Rigtering, and Ozcan Citation2018; Vaskelainen and Münzel Citation2017). Gaining insights into this can help platform owners, users, policymakers and others to understand the process of change and how to shape policies, regulations, and laws to promote public interests including a level playing field and the protection of labour, consumer and privacy (Frenken et al. Citation2018).

Second, we contribute to a more general understanding of the interactions between innovation and institutions, which has remained underdeveloped. Innovation studies traditionally focusses on the influence of regulation on innovation (Blind, Citation2012). Only recently, studies look at the co-evolution between innovation and regulation by bringing in concepts from institutional theory (Fuenfschilling and Truffer Citation2016; Sotarauta and Pulkkinen Citation2011; Tracey, Phillips, and Jarvis Citation2011). However, there is still a need to explore innovation-regulation interactions in the context of the involvement of a heterogeneous set of stakeholders, such as innovators, regulators, users and non-users. The heterogeneity of actors involved is important in the case of digital platforms, as they involve multiple actor groups and affect non-users through externalities (Scaraboto Citation2015).

This article aims to fill these two knowledge gaps and to answer the following question: Through which activities do actors involved in digital platforms influence institutional change?

The question is explored using the case of Airbnb. Airbnb is chosen as it is currently the largest home-sharing platform and has seen extensive debates about its acceptability, making it interesting to study in the context of institutional change (Mair and Reischauer Citation2017; Schor Citation2016). We study institutional change in the context of three cities in which Airbnb is active; Amsterdam (the Netherlands), London (UK) and New York City (USA). These cities followed different institutional development paths resulting in different institutional regimes.

2. Institutional work

Institutional theory explains the behaviour of actors and the emergence and diffusion of practices by emphasising the relevance of institutions (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983, Citation1991; Meyer and Rowan Citation1977; Scott Citation1995). The institutional context consists according to Scott (Citation1995) of three types of institutions; regulative, normative, and cognitive institutions. Here, we make a similar distinction, assuming that an innovation institutionalises in two dimensions: the degree of legitimacy and the degree of legality. A change in the degree of legitimacy refers to a change in common habits, norms, values, and established practices (i.e. normative and cognitive institutions), while a change in the degree of legality refers to a change in rules and laws that regulate relations and interactions (i.e. regulative institutions).

Changes in legitimacy and legality are necessary for new organisational forms to become part of institutional frameworks (Aldrich and Fiol Citation1994; Hampel and Tracey Citation2017; Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006). Online platforms are an example of such a new organisational form that does not fit existing institutions. More permissive regulations are needed for platforms to scale up and to become regarded as mainstream among investors, users, and the public at large. For such favourable regulations to be put in place, however, platforms need to become considered as a legitimate organisational form and the peer activities that platform enables need to be become considered as a legitimate practice as well. Favourable regulations, in turn, are likely to strengthen the legitimacy of platforms and their peers, as regulations mainstream an activity in the public eye by removing uncertainties among investors and users alike.

To study institutional change caused by platforms we thus take into account the degree of legality and legitimacy. The institutionalisation process of innovations can follow two typical pathways (). In Pathway 1 regulation follows legitimacy, which resonates with ‘permissionless innovation’ (Thierer Citation2016) represented by Silicon Valley’s adage of ‘don’t ask permission, ask forgiveness’ (Kenney and Zysman Citation2016). In such a process, a platform first focusses on creating a large user base providing them ‘practical legitimacy’ (Suchman Citation2011). Legislation then follows to codify a common practice. In the context of platforms, some even argue that regulatory oversight is not needed at all, because through review systems sharing economy platforms have their own ways of ensuring quality (Brail Citation2017).

In Pathway 2, legitimacy follows from regulation and covers the more traditional technology assessment approach, assessing the impacts of new technology through scientific research and social deliberation (Frenken and Schor Citation2017). This process, then, leads to the incorporation of new rules and should ultimately be followed by societal recognition.

We assume that pathway 1 is dominant in the case of the introduction of digital platforms. Platforms bypass established institutions and render existing intermediaries superfluous, making them almost inevitably in conflict with regulations (Edelman and Geradin Citation2015; Tseng, Hung, and Chan Citation2017). The associated ‘permissionless innovation’ rhetoric puts a large emphasis on the institutional work activities of the platform, acting as an assertive ‘institutional entrepreneur’ (Battilana, Leca, and Boxenbaum Citation2009). However, the popular image of a platform as the disruptor denies the fact that platforms do not act on their own, but connect buyers, sellers and auxiliary technologies and services, and, as such, constitute an ecosystem (Gawer Citation2009) consisting of a heterogeneous set of actors (Boudreau Citation2012; Yoo et al. Citation2012). What is more, regulators can be considered to be part of the platform’s ecosystem as well, as the specific regulatory actions of government may affect, either positively or negatively, the scope of operation of a platform and the business model options it can explore. Finally, one should also consider non-users of a platform that try to exert their influence on the operations of a platform, for example, by protest or sabotage (Wyatt Citation2005).

Taking an ecosystem perspective on the process of institutionalisation of platforms suggests that the notion of institutional entrepreneurship should be understood more precisely as a collective process. Collective institutional entrepreneurship, then, suggests that institutions change through a process of sustained engagement in which actors need to deal with disagreements and different frames of reference (Jolly and Raven Citation2015; Wijen and Ansari Citation2007). Although one would expect the collective to aim for change in an organised way, more often the collective efforts remain uncoordinated, dispersed and divergent (Dorado Citation2005), that is, actions are essentially ‘distributed’ (Gehman, Trevino, and Garud Citation2013).

In the context of collective institutional entrepreneurship, a wide range of activities to pursue institutional change can be employed. Here the notion of institutional work is useful. The notion widens the scope of activities, not only focussing on the creation of divergent visions and mobilisation of actors as emphasised in the institutional entrepreneurship framework (Battilana, Leca, and Boxenbaum Citation2009), but also leaving room for 1) interactions and collaborations among disparate groups, and 2) activities that concern the maintenance of existing institutions in which some members of a collective, such as incumbent firms or regulators, might still find important.

Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) have defined a set of institutional work activities that can be executed by actors to create, maintain or disrupt institutions. Creating institutions involves especially political work to enable the introduction of new regulations and policies. It also involves reconfiguring belief and meaning systems in order to change normative and cognitive institutions (Fuenfschilling and Truffer Citation2016). Creating institutions thus refers to both initiating change in the degree of legitimacy as well as in the degree of legality. Maintaining institutions refers to activities that are employed to keep institutions in place. Institutions do not automatically remain in effect without maintenance (Fuenfschilling and Truffer Citation2016). Maintenance activities are therefore not likely resulting in changes in the degree of legitimacy and the degree of legality. Disrupting institutions pertain to destabilisation of institutions which are expected to influence changes in the degree of legality and the degree of legitimacy. The set of institutional work activities is presented in . We use the list to investigate which activities what actors in and around digital platforms employ at what stage in the process of institutional change.

Table 1. Forms of institutional work for creating, maintaining and disrupting institutions (adapted from: Fuenfschilling and Truffer Citation2016; Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006).

3. Methodology

3.1. Case selection

We conduct a qualitative study to study the forms of institutional work undertaken by distributed actors. We apply the notion of institutional work in a novel context (that of online platforms). Our study is thus an explorative study, which is appropriate because it enables obtaining a deeper understanding of concepts and the relations between these concepts (Bryman Citation2015).

We chose to study the case of home sharing in three cities – Amsterdam, London and New York – focussing on Airbnb as the leading online platform in this sector. Although our study only deals with a short time period, the widespread public debates in each city and the frequent regulatory responses by government ensures that the relatively small timeframe still covers substantial institutional change. This will also become apparent below from the large number of relevant events that we were able to extract from media sources. Further note that we do not intend to systematically compare the multiple cases. Rather, we use the cases to explore different patterns in institutional work activities contributing to changes in the degree of legitimacy and legality, as well as to regulatory changes being implemented in each of the cities.

Airbnb started in 2008 in Amsterdam and New York, while the introduction in London followed one year later. In all three cities, its success is apparent from its rapid growth (). In Amsterdam and New York, the listings accounted in 2017 for over 1.5 percent of all households. In London, growth has been even more explosive, with listings already accounting for 2 percent of all households.

Figure 2. Percentage of Airbnb listings relative to inhabitants (AirDNA, Citation2017; WCCF, Citation2017). Numbers not corrected for hosts that provide multiple listings.

The three cities have experienced several regulatory changes regarding short-term rental by inhabitants leading to three quite different regimes at the start of 2018. Before the advent of Airbnb, home owners in Amsterdam were allowed to rent out their home without a permit for seven days or longer. Home owners, however, started to use Airbnb to rent out their homes for shorter periods as well. This prompted the municipality in 2014 to introduce a new regulation stating that home owners could rent out their home for short periods up to a maximum of 60 days a year and to no more than four guests at the same time. This regulation, codified in a ‘Memorandum of Understanding’ with Airbnb at the end of 2014, was intended to avoid that people would exploit their home as an illegal hotel by renting out their property all year long to tourists. The new regulation thus created a legal market for short-stay home sharing, explicitly separating this home-sharing market from the existing hotel market. In response to widespread non-compliance by home owners renting out their homes for more than 60 days, the municipality and Airbnb agreed in 2016 that Airbnb would actively enforce the 60 days rule by automatically removing listings that were rented out longer than 60 days in one year until the start of the next calendar year. The municipality of Amsterdam also introduced compulsory registration for hosts in 2017. Not complying to this compulsory registration leads to a fine of 6,000 euro. This unilateral move by the municipality was publicly criticised by Airbnb on grounds of excessive bureaucracy and a violation of privacy (Het Parool, 6 May 2017).

In New York there are stricter regulations in place than in Amsterdam. The municipality introduced the Multiple Dwelling Law in 2010, which prohibits renting out apartments that are part of 3+ apartment buildings for less than 30 days when the host is not present during the stay. The objective was to ‘protect guests, ensure the proper fire and safety codes, and protect permanent residents who must endure the inconvenience of hotel occupancy in their buildings’ and to ‘preserve the supply of affordable permanent housing’ (New York Times, 1 October 2014). As Airbnb is mostly used for overnight stays with the host not being present, these new regulations rendered the home-sharing practice in most of the cases illegal. Home owners who do not comply to these regulations can face a fine of 7,500 US Dollar (Katz Citation2017; Marcus Citation2016). Later, in 2016, additional regulation was put in place prohibiting advertisement of listings through websites like Airbnb to which the multiple dwelling law is applicable.

In London, regulations for short-stay rentals were initially very strict. From 2009 to 2014, regulations applied that made it illegal to host tourists for periods of less than three months through Airbnb without planning permission from the local planning authority. This effectively made it very hard for a regular home owner to legally rent out one’s home. This specific regulation was abolished by the Deregulation Act, which exempted home owners from the existing regulation by allowing them to rent out one’s home for a maximum of 90 days a year. Home sharing was further encouraged by two tax breaks. By now, home-sharing earnings are exempted from tax up to 7,500 British Pounds annually (Woolf Citation2016). Similar to the Amsterdam case, Airbnb also started to enforce the 90 days limit itself by removing listings that were rented out longer than 90 days per calendar year.

In sum, New York is the most restrictive as it allows home-sharing only for 30 days a year and requires the host to be present. Amsterdam is less restrictive allowing home-sharing for 60 days a year without the host being present, but requiring home owners to register each rental. London adopted the most liberal regime allowing home-sharing for 90 days a year and without the host being present. It further promotes home-sharing by exempting a substantial amount of the host’s earnings from tax.

3.2. Data collection

To map the institutional work activities, we adopted an empirical approach to institutional change as a process in which multiple activities need to be executed and events need to happen consecutively. Such process approach enables the mapping of these activities, events, opinions and actors involved (Hekkert et al. Citation2007; Van de Ven Citation1999). We used event history analysis to structure the mapping over time.

Event history analysis has been used more often in innovation studies and it explains outcomes as the result of events and activities (Hekkert et al. Citation2007; Van de Ven Citation1999). In the analysis events are the units of measurement that carry the processes under study and ‘are what central subjects do or what happens to them’ (Poole et al. Citation2000; p. 40). Data from various sources were entered as events into a database constructed in Excel. These entries featured ‘incident date’, the incident itself, the primary actor (who initiated the incident), source type, and source date. Because the events are the unit of analysis it could happen that multiple sources (newspaper articles, etc.) fed into one event entry.

Data is collected using four data sources. Using a media search, data were collected from newspaper articles about Airbnb in Amsterdam, London and New York over the time period of January 2009 (Airbnb being introduced in all three cities) until the end of May 2017. The LexisNexis Academic database was used, which includes a wide range of newspapers. For each city we assembled newspaper articles from the two most-read newspapers. Articles were searched for using a query containing ‘Airbnb’ and ‘name of the city’. In total 2,324 articles were read, of which 513 articles were selected that covered institutional change and were used for the analysis. The articles that were not selected were either duplications or did not cover concepts related to institutional change. In an overview is presented of the newspapers and the number of articles.

Table 2. Number of articles per newspaper and per city.

The events coming out of the media analysis were then triangulated with data from three other sources. First, the newspaper articles mentioned (non-)user initiatives that are either proponents or opponents of Airbnb. Examples include ‘Pretpark 020ʹ in Amsterdam, The Inside Airbnb Project, Subletspy.com and home sharing clubs from the Airbnb community in each city. We collected reports and opinions found on the websites of these user initiatives or on social media platforms that these initiatives used. In doing so, we could track the main events, arguments and perceptions that these actors are engaged in, with which we enriched the timelines.

Second, policy documents were analysed to obtain a clear overview of the legal situation and changes in rules and regulations regarding Airbnb in a city. These documents were mostly produced by the city governments, and sometimes originated from the national government.

Third, expert interviews were performed in order to verify, validate, and nuance the data obtained from newspaper articles, user initiatives, and policy documents and to obtain a deeper understanding of institutional change. Six in-depth semi-structured interviews were executed (respondents indicated below by R1 to R6) including two representatives of the municipalities, one of Airbnb, one web-based data collector on Airbnb, and two experts on home sharing. We approached these respondents because they were either mentioned in newspaper articles, referred to by contacts at organisations that featured prominently in the timelines, or referred to by other researchers on digital platforms. The interviews were transcribed and sent back to the respondents for validation.

3.3. Data analysis

The resulting database consisted of events and related dates and actors. We coded the events using the institutional work concepts as categories and using six actor categories: the Airbnb platform, users (mainly hosts), regulatory bodies, market participants (including landlords, real estate agencies, lawyers, and hotels), facilitators, and non-users. Non-users cover different people (Wyatt Citation2005) including ‘rejecters’ who had a negative experience with either hosting or renting through Airbnb, ‘expelled users’ who misused the platform in any way, and ‘resisters’, particularly neighbours experiencing nuisance from home-sharing practices. One event could be related to one or more institutional work and actor categories. To provide context to the data and prevent that implicit results are ignored, there was also room for open coding. After completing the coding, the database allows for the selection of different categories, which enables the counting of activities and the counting of actors performing these activities. These counts are visualised in graphs in order to identify which activities are relatively performed most (for each city) and which actors are relatively most involved. The visualised graphs and the results are supported by narratives based on the qualitative data obtained in this study (Van Weele, van Rijnsoever, and Nauta Citation2017).

4. Analysis

The following sections report the institutional work processes we found in the three cities. presents the main results of the media analysis mapping the amount of articles associated with creating, maintaining and disrupting institutions broken down per actor category for each of the three cities. The immediate observation one can make is that actors were most active in New York and least so in London, with Amsterdam in between. This pattern is consistent with the legal process, with regulations being most restrictive in New York and most liberal in London. It shows that is most contested in New York causing high rates both in creating activities by proponents proposing permissive institutions and in maintaining activities by opponents defending strict regulations by opponents. By contrast, in London, much less institutional work is visible as well as a higher ratio of creating activities over maintaining activities compared to New York and Amsterdam.

Figure 3. Involvement of actor categories in creating, maintaining and disrupting institutions in the three cities.

A second striking observation holds that actors are mainly engaged in creating and maintaining institutions, while disrupting activities are very rare. This suggests that the process of institutional change in each of the cities has been one in which proponents and opponents are part of a continuous process of negotiation about balancing new and existing regulations, without any serious undermining of the regulatory order as such.

A third observation holds that platforms are not the most active type of actors in the public debate. Instead, users and non-users are most active with users being involved in creating new institutions legitimising home sharing more generally, while non-users focussing on maintaining regulations that restrict home sharing. Interestingly, this pattern is rather similar across the three cities.

If we look at the time trends in each of the cities in , we cannot observe any particular pattern in the times series of creating, maintaining and disrupting activities. In each of the three cities, we see a continuous stream of creating and maintaining activities, which suggests that institutional change is a gradual process and did not cease to be heated and contested. If anything, the trend is upward suggesting that the process has not reached any form of consensus despite the new regulations that were put in place. Instead, regulatory events may provoke new discussions about the legitimacy of platforms, for example, regarding enforcement and effectiveness of regulation. Furthermore, one may note that the upward trend also reflects the growth of home sharing itself, leading to more contestation due to rising usage and related impacts.

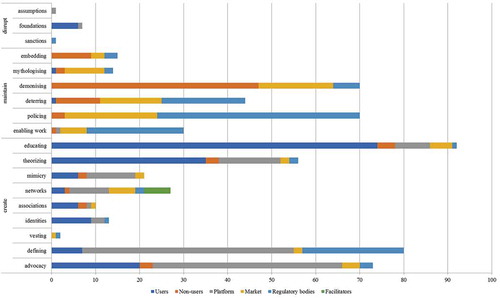

Once we break down the creating, maintaining and disrupting activities into our finer categorisation as in , we can observe that that different actors display rather specific roles in the process of institutional change. The platform focusses on defining the regulatory systems (jointly with regulators) while advocating the platform’s interests (jointly with users). Users mostly theorise about the benefits of online home sharing and educate prospective users supporting the further adoption of home sharing. Non-users mainly oppose the rapid growth of home sharing and accordingly engage in maintaining activities to defend existing social norms and restrictive regulations already in place. They do so almost exclusively by demonising home sharing as a new practice from a normative point of view, pointing to the negative effects for neighbourhoods, including excessive tourism, rising rents and nuisance among neighbours. Market participants with incumbent interests and regulatory bodies also try to maintain existing norms and regulations, but they do so in a more formal way by policing and deterring. Finally note that regulatory bodies, in particular municipalities, can be considered as taking a position in between all actors as reflected by their simultaneous roles in creating and maintaining institutions. In particular, we observe that regulatory bodies are very active in defining new institutions as well as policing existing institutions at the same time. One can thus conclude from the many actors who are part of the public debate as well as their specific roles in institutional work activities that the process is not just a collective, but also a distributed process.

Figure 5. Number of institutional work activities performed by different actors across the three cities.

To understand institutional work in more depth, we go into more detail regarding the most salient activities regarding creating, maintaining and disrupting activities.

4.1. Work activities to create institutions

4.1.1. Theorising

With the launch of its website, Airbnb offered a new kind of service linking home owners with people who needed short-stay accommodation. It introduced a new category of accommodation rental that was dissimilar to what had existed before. The platform applied multiple theorising activities to establish the new category with related logics. ‘Airbnb’s real innovation is not online rentals. It’s “trust”. It created a framework of trust that has made tens of thousands of people comfortable renting rooms in their homes to strangers’ (NYT21/07/2013). What is more, Airbnb actively underlined the economic and social benefits to cities and its residents in blogs (blog.atairbnb.com/), while also emphasising the wider sustainability impacts of home sharing on their website based on a commissioned environmental impact study (https://blog.atairbnb.com/environmental-impacts-of-home-sharing/). In the face of looser quality controls compared to hotels, Airbnb emphasises the quality-boosting nature of peer-to-peer reviewing (R4). Theorising also involves conceptualising the embedding of the platform service in a wider context: ‘Airbnb hosts need to be able to change their insurance cover between commercial and personal at the flick of a switch. The level of societal change we will see in the next five years demands a huge rewiring of the industry. This will impact the big players in traditional financial services, regulators, government and new entrants alike’ (DT31/03/2017). Theorising influences the degree of legitimacy as it focuses on embedding and placing Airbnb in a prevailing context, which makes the new services more familiar and less contested.

4.1.2. Educating

Related to theorising is the day-to-day, operational education of suppliers and users on the platform. In each city one of the first activities was bringing Airbnb to the attention through word-of-mouth advertising, which consisted of educating citizens in skills and knowledge necessary to support and use Airbnb. On the user side Airbnb needed to gain brand awareness: ‘for anyone low on cash and high on wanderlust, there’s a new option: AirBed & Breakfast, a Web-based company that hooks up locals with visitors looking for a place to crash’ (NYT17/05/2009). Education was also offered to suppliers of homes. Books and articles were published about skills of how best to use Airbnb, e.g. ‘The Guide to Being an Airbnb Superhost’ (NYT11/01/2017) or how to protect yourself from fraud: ‘what can you do to ensure a problem-free letting through Airbnb, Wimdu and other “social travel” sites?’ (G11/10/2014). Platform users played a significant role in educating, i.e. creating awareness about the platform and about how to use the service. Next to the platform’s own community environment (community.withairbnb.com), users also established their own web fora, such as airhostsforum.com and learnairbnb.com. Suppliers of homes exchanged experiences and tips, e.g. on how to relate to requirements from landlords, insurance companies and mortgage lenders: ‘many of these hosts might not be aware that their sideline rental business could lead to trouble with their mortgage lender, insurer, freeholder or local authority. If you are thinking of joining this new branch of Britain’s “sharing economy”, read these warnings first’ (DT07/06/2016). Other organisations started acknowledging Airbnb and assisted in the progress and use of Airbnb: real-estate agencies marketed houses by emphasising suitability for Airbnb listing, and facilitating companies were created that manage listings and arrange key transfers. Consequently, educating has predominantly influenced normative and cognitive institutions and by this the degree of legitimacy.

4.1.3. Defining

Defining activities centred on the maximum amount of days that a home can be rented out per year (30 days in New York, 60 days in Amsterdam, 90 days in London). Airbnb does not oppose such maxima and have regularly indicated that hosts renting out all year round constituted an illegal hotel (R4). The way in which Airbnb demarcated these maxima had a legal but certainly also a legitimacy reason, which became apparent when they announced to provide support enforcing the 90-days rule in London: ‘“we want to help ensure that home-sharing grows responsibly and sustainably, and makes London’s communities stronger,” the company said when it introduced the change. “That is why we are introducing a change to our platform that will create new and automated limits to help ensure that entire home listings in London are not shared for more than 90 days a year, unless hosts confirm that they have permission to share their space more frequently”’ (G03/01/2017). Following these regulations, governments and other stakeholders expected to gain more insights into Airbnb statistics, in particular, to find out to what extent the listings follow the law and to be able to tax hosts. Airbnb, however, was extremely reluctant to be transparent on the matter, pointing to safeguarding users’ privacy: ‘if a city comes to us, as NY did, and just say we’re going to demand that you hand over the data of everybody in the city, because we think that some of them might break the law. We are going to challenge that’ (R4). In Amsterdam and later in New York in December 2015, Airbnb released anonymised data about its listings and where, how, and how often these listings were offered. However, in the case of New York the insights led data activists to become active. An independent initiative ‘Inside Airbnb’ scrapped data from the online platform and released statistics that were different from the Airbnb data: ‘an independent report released Wednesday cast a shadow on that rosy picture, claiming that the company “misled the media and the public” by removing more than 1,000 listings from its site in November before making available the data’ (NYT12/02/2016). Thus, Airbnb’s transparency backfired and led the municipality to create additional rules regarding the Multiple Dwelling Law, prohibiting to advertise illegal listings and strengthening enforcement by instating high fines. Airbnb questioned the validity of the data provided by data scrapers: ‘we have to fight bad data with good data’ (R4). Defining activities are also employed as a reaction to negative publicity. In New York accusations of discrimination on the platform spurred new rules: Airbnb ‘told its rental hosts that they needed to agree to a “community commitment” starting on Nov. 1 and that they must hew to a new non-discrimination policy’ (NYT09/09/2016). Moreover, defining can also take the form of deleting listings from the platform: ‘the online home-sharing company said that the listings removed from its platform in New York City “were controlled by commercial operators and did not reflect Airbnb’s vision for our community”’ (DN25/02/2016). In sum, defining aims to influence the degree of legality and legitimacy.

4.1.4. Advocacy

In Amsterdam regulative institutions were mostly created through direct interactions between the municipality and Airbnb, making advocacy activities unnecessary. Extensive negotiations led to a first ‘Memorandum of Understanding’ in 2014 and an updated one in 2016. The only exception was the introduction of the compulsory registration, which Airbnb tried to counteract by mobilising its users to advocate against the registration (T24/05/2017). Too fierce advocacy also has a pushback. For example, Airbnb pursuing a lawsuit against the municipality created a public image of sharks: ‘the expensive Airbnb lawyers against the losers from the municipality’ (R1). In London, Airbnb faced little governmental resistance so there was less need for advocacy activities. However, in New York the illegal nature of the platform service forced Airbnb to mobilise political support. One way was to encourage hosts to lobby on the company’s behalf: Airbnb created ‘“Home Sharing Clubs” […] for hosts to connect with others in their neighbourhood and advocate for the company. On Monday, several picketed outside Democratic Assemblywoman Linda Rosenthal’s Upper West Side office to protest her bill that would prohibit advertising illegal home shares in New York City’ (DN15/06/2016), ‘About two dozen New Yorkers who rent their homes out through Airbnb are going to the Democratic National Convention to plead the case for home-sharing to the state’s elected officials’ (DN26/07/2016), and ‘Airbnb provided funding for the “Fair to Share” campaign in the Bay Area, which lobbies to allow short-term housing rentals, and is currently hiring “community organizers” to amplify the voices of home-sharing supporters’ (NYT07/08/2015). These three cases show that users have played a role in supporting lobbying activities: ‘our response is to help organise our hosts to be advocates of their own interests’ (R4).

4.2. Work activities to maintain institutions

4.2.1. Policing

Policing is the most often executed maintaining activity in order to ensure compliance of Airbnb with the existing institutional framework. It is used to restrict Airbnb’s operations in the cities. In Amsterdam and New York, being less accepting to Airbnb, the municipalities mobilised more enforcement activities. These took e.g. the form of handing out fines, which in reaction led to home owners going to court. The platform was monitored by means of data scraping and hotlines for complaints: ‘the mayor’s Office of Special Enforcement, charged with cracking down of scofflaws, has wisely used that power strategically – responding to complaints dialed to the city’s 311 system by neighbors and using data analysis to catch illegal hotel operators who deal in bulk’ (DN10/12/2016) and ‘the war against illegal hotels and housing fraud is being intensified. By using new digital search methods, not only physical locations, but also all citizens who do not follow the rules will be proceeded against. This “scraping” is the automated collection of content of databases from booking sites, such as Airbnb’ (P15/02/2016). In Amsterdam a political party created a hotline and the municipality founded a knowledge centre, DataLab, to produce and analyse platform data. Airbnb explicitly distanced itself from active enforcement (‘privatising policing is not a desirable outcome’, R4). It regarded policing as a public matter, and claimed that it would be impossible for them to distinguish legal from illegal offerings on their platform (R4), but later on decided to support local government’s enforcement by removing hosts after 60 days (in Amsterdam) or 90 days (in London). Meanwhile, some facilitating agencies like ’60 days’ assisted with soft enforcement, offering to keep an eye on the 60 day limit. Policing influences both the degree of legality and the degree of legitimacy. For example, when more enforcement action is taken, more users are hesitant to use the service as they often do not know whether their activity is fully legal and they do not want to face a fine: ‘a bill […] would hit New Yorkers with fines ranging from $10,000 to $50,000 […] Penalties of that magnitude would put Airbnb and its competitors out of business, because very few people would risk having to pay so much money in order to earn far less in rental fees’ (D25/10/2015). This thus lowers the degree of legitimacy. It influences the degree of legality in the sense that it became clear during enforcement processes that more and more illegal activities were taking place and that enforcing the rules was difficult. This subsequently resulted in more restrictive regulations, such as the compulsory registration in Amsterdam (R1; R2).

4.2.2. Deterring

Deterring is mostly performed by incumbent players in the hotel market and by non-users that resist or reject Airbnb. The association for the hospitality industry started lobbying: ‘I do see that this [referring to Airbnb] is a trend, and we do not oppose that. However, equal rules must apply. The owners should pay tourist and income taxes. And they should be similarly enforced and controlled’ (T22/08/2012). In New York the hospitality industry was actively deterring Airbnb: it ‘has declared war on the short-term rental company by raising regulatory concerns, even as hotel executives have tried to play down the effect Airbnb has had on their businesses’ (NYT18/04/2017). Incumbent firms also reacted by improving their own business: ‘it is not impacting the business yet but we do keep a very close eye on rivals and do things to protect us from things like Airbnb, such as refurbishing rooms and upgrading our technology’ (DT02/05/2017). In Amsterdam, the association for the hospitality industry lobbied with national Parliament for the compulsory registration. Non-users established barriers for the use of Airbnb by actively articulating reasons that make Airbnb unattractive. One non-user mentions multiple reasons: ‘putting horror stories of swinging parties aside, there are still many reasons why people may be deterred from becoming hosts – from having to stop using the spare room as an offshoot of the airing cupboard, to the faff of changing the sheets after each guest’ (DT22/01/2016). Non-users also started wider-spanning initiatives to actively counteract change and mobilise resisters. In Amsterdam and New York multiple initiatives were founded, such as the Inside Airbnb Project (started by a resister), subletspy.com (started by a rejecter), and Pretpark020 (started by resisters). These web-based initiatives are either focused on creating more transparency with regard to the new service (Inside Airbnb Project and subletspy.com), or communicating negative stories about the service (Pretpark020). For example, the reason of founding subletspy.com was that: ‘a techie entrepreneur whose Chelsea pad was trashed after he rented it on Airbnb and it was used to host an orgy has launched a website to help landlords crack down on illegal subletters’ (DN04/04/2016). Deterring is focused on establishing barriers for use and thus predominantly influences the degree of legitimacy.

4.2.3. Demonising

Incumbent players, regulatory bodies and non-users performed demonising activities, such as writing negative stories in newspapers and using titles such as: ‘If you want to hear a real Airbnb horror story … ’ (G17/09/2016). In addition, ad campaigns were launched to communicate negative stories, for example: ‘ShareBetter has a new ad; it will run for a week starting Monday on broadcast and cable television accusing Airbnb of saying it wants to help the middle class while actually hurting the availability of affordable housing units in the city’ (DN24/10/2016). The controversial nature of Airbnb in Amsterdam was highlighted in an influential documentary [VPRO Tegenlicht ‘Sleeping Rich’] in late 2016: opponents articulated their dissatisfaction and the negative externalities associated with Airbnb. Non-users such as resisters, rejecters and for a smaller part expelled users were active in demonising activities, e.g. through writing letters to newspapers: ‘this all sounds great, but what if you live in a high-rise rental apartment in Manhattan (like me) when the elevators are filled with foreign tourists rolling in large suitcases, clogging the lobby, the doormen and the hallways, maids walking through halls changing beds, etc.? […] Fortunately it has stopped due to other tenant complaints. But even if visitors sub-rent an apartment, they can easily disturb, even frighten the rest of the tenants who also pay to live there but receive no profit from this’ (NYT04/05/2014). Demonising is focused on influencing normative and cognitive institutions and the perception of Airbnb and by this influences the degree of legitimacy.

4.3. Work activities to disrupt institutions

Airbnb and other actors around the platform have not been engaged much in disruptive institutional work activities. Airbnb was mostly engaged in creating new institutions next to existing ones, rather than attacking or destabilising institutions. The few disruptive activities we found were the result of Airbnb being pictured as a threat to hotels and jobs, to which the platform reacted by emphasising its radically new practice that needs to become part of the extant short-stay culture.

5. Conclusions and discussion

Contrary to the popular view of online platforms as disruptive entrepreneurs, we found in the case of home sharing that Airbnb mainly focused on creating new institutions rather than disrupting existing ones. We also found that the platform users and platform non-users undertake most of the institutional work activities with users engaging in creating institutions by theorising and educating about benefits of home sharing and non-users in maintaining institutions by demonising home sharing by pointing to risks and detrimental social impacts. Regulators stand in between as they recognise both the pros and cons and delineate the practice by introducing and policing new regulation. Our study suggests that the process of institutional work accompanying the introduction of a P2P platform may thus not be one orchestrated by the platform, but rather a collective and relatively distributed development involving a multitude of stakeholders playing different roles.

Our study () also made clear that the process of institutional work may follow rather ‘erratic’ dynamics with a continuous exchange of opinions, views and proposals among proponents (the platform and its hosts) promoting new institutions and their opponents (incumbents and non-users) defending existing institutions. Regulatory bodies, in particular municipalities, stand in between as reflected in their simultaneous role in creating and maintaining activities. The process underlying institutional change is essentially one of contestation, aptly described before as ‘the creative embrace of contradiction’ (Hargrave and Van De Ven Citation2009).

Consistent with our theoretical framework, we found that the varying levels of legitimacy across the three cities could be related to varying regulatory outcomes, with New York being the most restrictive city and London as the most liberal with Airbnb. Yet, we also observed that the various regulatory changes – though responsive to legitimacy concerns – did not lead to institutional work activities to diminish. If anything, institutional work activities only increased over time in all three cities. This shows that collective institutional work co-evolves in complex ways with regulatory changes. In the specific case of Airbnb, these ‘zigzag’ dynamics do not only reflect ongoing contestation about what regulations should be, but also a collective learning process about how regulations can be enforced. Over time, once enforcement problems were widely acknowledged among all actors, follow-up regulations were introduced (in Amsterdam and New York), and agreements with Airbnb was reached about policing by the platform itself (in Amsterdam and London).

Our study provides some new theoretical insights into the institutionalisation process of innovations and the interplay between an innovation’s legitimacy and legality. In our initial theoretical framework (), we distinguished between two archetypical processes of institutional change: one in which regulation follows from legitimacy (pathway 1) and one in which legitimacy follows from regulation (pathway 2). In the first case, regulation builds on established user practices that have gained widespread legitimacy. In the second case, legitimacy follows from regulation that is based on a scientific impact assessment and/or public consultation processes. Pathway (1) does not apply to the Airbnb case since regulations have emerged despite home sharing being widely regarded as illegitimate. Pathway (2) does not apply either as the regulations have not been based on a scientific impact assessment or public consultation process nor have regulations been enforced effectively (at least, until recently). After new regulations were introduced – and with home sharing ever growing – public opinion among non-users has remained negative. Instead, we would describe the institutional change process as following a zigzag pattern (pathway 3) as depicted in our extended theoretical framework in .

Our study has a few limitations. First, there are limits to the generalisability of the study. The three cities studied all have their own historical and institutional backgrounds. Making a direct comparison between the cities as well as trying to extend lessons learnt to other cities is thus difficult. Furthermore, drawing conclusions regarding home-sharing platforms more generally should be done carefully. Airbnb is rather specific being the only home-sharing platform actively collaborating with municipalities. And, when generalising to other online P2P platforms, caution should be taken as these platforms operate in different sectoral institutional contexts. There other enabling conditions may hold, which may result in different activities to be executed.

Second, although we used a wide range of data sources including interviews and documents, the reliance on media outings such as newspaper articles might mean that we did not cover all nuances of the cases. Especially informal institutional work and changes in legitimacy are not always codified. In future research, more detailed mapping of institutional work could be achieved by analysing e-mail exchanges between peers and platform, and by analysing platform blogs using netnography (Grabher and Ibert Citation2013).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Acquier, A., T. Daudigeos, and J. Pinkse. 2017. “Promises and Paradoxes of the Sharing Economy: An Organizing Framework.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 125: 1–10. doi:10.1016/J.TECHFORE.2017.07.006.

- AirDNA. 2017. “Airbnb Data & Insights to Succeed in The Sharing Economy.” Accessed July 11, 2017. https://www.airdna.co/

- Aldrich, H. E., and C. M. Fiol. 1994. “Fools Rush In? the Institutional Context of Industry Creation.” Academy of Management Review 19 (4): 645–670. doi:10.5465/AMR.1994.9412190214.

- Battilana, J., B. Leca, and E. Boxenbaum. 2009. “2 How Actors Change Institutions: Towards a Theory of Institutional Entrepreneurship.” The Academy of Management Annals 3 (1): 65–107. doi:10.1080/19416520903053598.

- Blind, K. 2012. “The Influence of Regulations on Innovation: A Quantitative Assessment for Oecd Countries.” Research Policy 41 (2): 391–400. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.08.008.

- Boudreau, K. J. 2012. “Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom? an Early Look at Large Numbers of Software App Developers and Patterns of Innovation.” Organization Science 23 (5): 1409–1427. doi:10.1287/orsc.1110.0678.

- Boudreau, K. J., and A. Hagiu. 2008. “Platform Rules: Multi-Sided Platforms as Regulators.” SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1269966.

- Brail, S. 2017. “Promoting Innovation Locally: Municipal Regulation as Barrier or Boost?” Geography Compass 11 (12): e12349. doi:10.1111/gec3.12349.

- Bryman, A. 2015. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Constantiou, I., B. Eaton, and V. K. Tuunainen. 2016. “The Evolution of a Sharing Platform into a Sustainable Business.” 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, January 5–8, 2016. 1297–1306. IEEE. 10.1109/HICSS.2016.164

- DiMaggio, P. J., and W. W. Powell. 1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review 48: 147–160. doi:10.2307/2095101.

- DiMaggio, P. J., and W. W. Powell, eds. 1991. “Introduction.” In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, 1–38. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Dorado, S. 2005. “Institutional Entrepreneurship, Partaking, and Convening.” Organization Studies 26 (3): 385–414. doi:10.1177/0170840605050873.

- Edelman, B. G., and D. Geradin. 2015. “Efficiencies and Regulatory Shortcuts: How Should We Regulate Companies like Airbnb and Uber.” Stanford Technology Law Review 19: 293–326.

- Frenken, K., A. Van Waes, M. Smink, and R. Van Est (2018). “Safeguarding Public Interests in the Platform Economy.” Vox.

- Frenken, K., and J. B. Schor. 2017. “Putting the Sharing Economy into Perspective.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 23: 3–10. doi:10.1016/J.EIST.2017.01.003.

- Fuenfschilling, L., and B. Truffer. 2016. “The Interplay of Institutions, Actors and Technologies in Socio-Technical Systems — An Analysis of Transformations in the Australian Urban Water Sector.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 103: 298–312. doi:10.1016/J.TECHFORE.2015.11.023.

- Gawer, A. 2009. Platforms, Markets, and Innovation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Gehman, J., L. K. Trevino, and R. Garud. 2013. “Values Work: A Process Study of the Emergence and Performance of Organizational Values Practices.” Academy of Management Journal 56 (1): 84–112. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0628.

- Grabher, G., and O. Ibert. 2013. “Distance as Asset? Knowledge Collaboration in Hybrid Virtual Communities.” Journal of Economic Geography 14 (1): 97–123. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbt014.

- Hagiu, A., and J. Wright (2015). “Multi-Sided Platforms.” Harvard Business School Working Paper, 15–037.

- Hampel, C. E., and P. Tracey. 2017. “How Organizations Move from Stigma to Legitimacy: The Case of Cook’s Travel Agency in Victorian Britain.” Academy of Management Journal 60 (6): 2175–2207. doi:10.5465/amj.2015.0365.

- Hargrave, T. J., and A. H. Van De Ven. 2009. “Institutional Work as the Creative Embrace of Contradiction.” In Institutional Work: Actors and Agency in Institutional Studies of Organizations, edited by T. B. Lawrence, R. Suddaby, and B. Leca, 120–140. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hekkert, M. P., R. A. Suurs, S. O. Negro, S. Kuhlmann, and R. E. H. M. Smits. 2007. “Functions of Innovation Systems: A New Approach for Analysing Technological Change.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74 (4): 413–432. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2006.03.002.

- Jolly, S., and R. P. J. M. Raven. 2015. “Collective Institutional Entrepreneurship and Contestations in Wind Energy in India.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 42: 999–1011. doi:10.1016/J.RSER.2014.10.039.

- Katz, M. (2017). “A Lone Data Whiz Is Fighting AirBnB and Winning.” Wired. https://www.wired.com/2017/02/a-lone-data-whiz-is-.

- Kenney, M., and J. Zysman. 2015. “Choosing a Future in the Platform Economy: The Implications and Consequences of Digital Platforms.” Kauffman Foundation New Entrepreneurial Growth Conference, Amelia Island, FL, 156–160.

- Kenney, M., and J. Zysman. 2016. “The Rise of the Platform Economy.” Issues in Science and Technology 32 (3): 61–69.

- Kenney, M., P. Rouvinen, T. Seppälä, and J. Zysman. forthcoming. “Platforms and Industrial Change. Industry & Innovation.” https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13662716.2019.1602514

- Lakshman, C., and M. Akhter. 2015. “Microfoundations of Institutional Change: Contrasting Institutional Sabotage to Entrepreneurship.” Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences De l’Administration 32 (3): 160–176. doi:10.1002/cjas.1325.

- Lawrence, T. B., and R. Suddaby. 2006. “Institutions and Institutional Work.” In Handbook of Organization Studies, edited by R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, and W. R. Nord, 215–254. London, UK: Sage.

- Liang, L. J., H. C. Choi, and M. Joppe. 2018a. “Exploring the Relationship between Satisfaction, Trust and Switching Intention, Repurchase Intention in the Context of Airbnb.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 69: 41–48. doi:10.1016/J.IJHM.2017.10.015.

- Liang, L. J., H. C. Choi, and M. Joppe. 2018b. “Understanding Repurchase Intention of Airbnb Consumers: Perceived Authenticity, Electronic Word-Of-Mouth, and Price Sensitivity.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 35 (1): 73–89. doi:10.1080/10548408.2016.1224750.

- Mair, J., and G. Reischauer. 2017. “Capturing the Dynamics of the Sharing Economy: Institutional Research on the Plural Forms and Practices of Sharing Economy Organizations.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.023.

- Marcus, L. (2016). “Airbnb Banned in NYC? What Actually Just Happened.” CN Traveller, https://www.cntraveler.com/story/airbnb-banned-in-.

- Meyer, J. W., and B. Rowan. 1977. “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (2): 340–363. doi:10.1086/226550.

- Poole, M. S., A. H. Van de Ven, K. Dooley, and M. E. Holmes. 2000. Organizational Change and Innovation Processes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ranchordas, S. 2015. “Does Sharing Mean Caring: Regulating Innovation in the Sharing Economy.” Minnesota Journal of Law, Science and Technology 16. Accessed. http://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/mipr16&id=421&div=11&collection=journals

- Scaraboto, D. 2015. “Selling, Sharing, and Everything in Between: The Hybrid Economies of Collaborative Networks.” Journal of Consumer Research 42 (1): 152–176. doi:10.1093/jcr/ucv004.

- Schor, J. 2016. “Debating the Sharing Economy” Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics 4 (3): 7–22. Accessed. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=430188.

- Scott, R. W. 1995. Institutions and Organizations. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Seo, M.-G., and W. E. D. Creed. 2002. “Institutional Contradictions, Praxis, and Institutional Change: A Dialectical Perspective.” Academy of Management Review 27 (2): 222–247. doi:10.5465/AMR.2002.6588004.

- Sotarauta, M., and R. Pulkkinen. 2011. “Institutional Entrepreneurship for Knowledge Regions: In Search of a Fresh Set of Questions for Regional Innovation Studies.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 29 (1): 96–112. doi:10.1068/c1066r.

- Suchman, M. C. 2011. “Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches.” Academy of Management Review 20 (3): 571–610.

- Thierer, A. 2016. Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom. Arlington: Mercatus Center.

- Tracey, P., N. Phillips, and O. Jarvis. 2011. “Bridging Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Creation of New Organizational Forms: A Multilevel Model.” Organization Science 22 (1): 60–80. doi:10.1287/orsc.1090.0522.

- Tseng, Y.-C., S.-C. Hung, and C.-L. Chan. 2017. “When Sharing Economy Meets Established Institutions: A Comparative Case Study.” Academy of Management Proceedings 2017 (1): 15627. doi:10.5465/ambpp.2017.15627abstract.

- Uzunca, B., and A. Borlenghi. forthcoming. “Regulation Strictness and Supply in the Platform Economy: The Case of Airbnb and Couchsurfing .”

- Uzunca, B., J. P. C. Rigtering, and P. Ozcan. 2018. “Sharing and Shaping: A Cross-Country Comparison of How Sharing Economy Firms Shape Their Institutional Environment to Gain Legitimacy.” Academy of Management Discoveries 4 (3): 248–272. doi:10.5465/amd.2016.0153.

- Van de Ven, A. H. 1999. The Innovation Journey. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Van Weele, M., F. J. van Rijnsoever, and F. Nauta. 2017. “You Can’t Always Get What You Want: How Entrepreneur’s Perceived Resource Needs Affect the Incubator’s Assertiveness.” Technovation 59: 18–33. doi:10.1016/J.TECHNOVATION.2016.08.004.

- Vaskelainen, T., and K. Münzel. 2017. “The Effect of Institutional Logics on Business Model Development in the Sharing Economy: The case of German Carsharing Services.” Academy of Management Discoveries 4 (3): 273–293. doi:10.5465/amd.2016.0149.

- WCCF. 2017. “World Cities Culture Forum: Number of Households.” Accessed July 11 2017. http://www.worldcitiescultureforum.com/data/number-of-households

- Wijen, F., and S. Ansari. 2007. “Overcoming Inaction through Collective Institutional Entrepreneurship: Insights from Regime Theory.” Organization Studies 28 (7): 1079–1100. doi:10.1177/0170840607078115.

- Woolf, N. (2016). “Airbnb Regulation Deal with London and Amsterdam Marks Dramatic Policy Shift.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/dec/03.

- Wyatt, S. 2005. “Non-Users Also Matter: The Construction of Users and Non-Users of the Internet.” In How Users Matter: The Co-Construction of Users and Technologies, edited by N. Oudshoorn and T. Pinch, 67–80. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Yoo, Y., R. J. Boland, K. Lyytinen, and A. Majchrzak. 2012. “Organizing for Innovation in the Digitized World.” Organization Science 23 (5). doi:10.1287/orsc.1120.0771.

- Zervas, G., D. Proserpio, and J. W. Byers. 2017. “The Rise of the Sharing Economy: Estimating the Impact of Airbnb on the Hotel Industry.” Journal of Marketing Research 54 (5): 687–705. doi:10.1509/jmr.15.0204.