ABSTRACT

We explore the growth, scope and impact of the academic literature that has arisen around the concept of innovation ecosystems. We highlight some of the most important definition, the place of innovation policies and the future accomplishments that could be made.

1. Definition and growth of the notion of ecosystems in management science

A considerable academic literature in the domain of management has arisen in the past two decades around the notion of ecosystems, and in particular around the notion of innovation ecosystems. A number of academic and practitioner journals, conferences and workshops have been organised in recent years on those topics. The academic interest is nowadays matched by managerial, industrial and policy makers' uptake and operationalisation of the concept. The paragraphs below seek to provide an overview of the work undertaken so far and identify key areas of progress and forthcoming research possibilities.

Anchored in the biological metaphor, several definitions of the ecosystem concept within the management literature have emerged over the years. For instance, an ecosystem encompasses ‘the alignment structure of the multilateral set of partners that need to interact in order for a focal value proposition to materialize’ (Adner Citation2016, 40). This definition embraces all types of ecosystems that can be found in the literature. In an extensive review of papers defining specifically innovation ecosystems, Granstrand and Holgersson (Citation2020) summarise different approaches. They conclude that an innovation ecosystem corresponds to ‘the evolving set of actors, activities, and artefacts, and the institutions and relations, including complimentary and substitute relations that are important for the innovative performance of an actor or a population of actors’. Moreover, Adner’s work proposes a synthesis of governance of an ecosystem and of the business model of the system. Each ecosystem can be described from an actor-centric point of view and from a structure centric point of view, the business model of the whole ecosystem reconciles these points.

Drawing on this biological metaphor, a significant amount of works in the management literature since the mid 90s focused on two main conceptual clarifications:

The differences between the notion of ‘systems’ and the notion of ‘ecosystems’, in particular in a territorial context (local, regional, national). Most of the key contributions in this perspective (Torre and Zimmermann Citation2015; Bassis and Armellini Citation2018) highlight a strong contrast between the static point of view of the notion of systems with the dynamic perspective inherent to the notion of ecosystem: In a static vision the notion of system of innovation is a set of existing formal entities, ‘which jointly and individually contribute to the development and diffusion of new technologies, and which provides the framework within which governments form and implement policies to influence the innovation process’ (Metcalfe Citation1995). A system of innovation focuses on how the nature of interactions between existing institutions (which remain unchanged in the process) conditions innovation trajectories (‘how institutions drive action’).

On the contrary, in a dynamic perspective, the notion of ecosystem refers to a set of heterogeneous formal entities and informal actors (users, diverse communities, individual talents) engaged in a process of knowledge co-building. The notion of ecosystem does not assume that institutions already exist. Instead, it concentrates on the dynamics of innovation that lead to the transformation of institutions or the formation of new institutions and practices (‘how action drives institutions’) (Bresnahan, Gambardella, and Saxenian Citation2001).

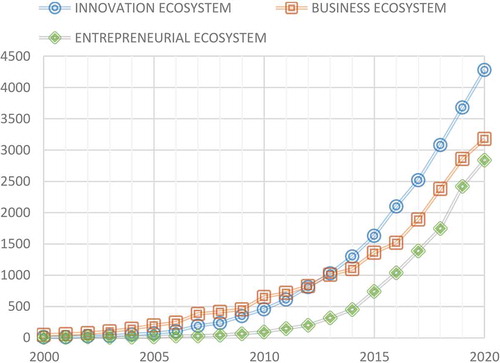

The characterisation of the different types of ecosystems. Initially, the first notion to be introduced in the literature was the concept ‘business ecosystem’ by Moore (Citation1993), followed by ‘innovation ecosystem’ (Adner Citation2006; Autio and Thomas Citation2014), ‘entrepreneurial ecosystem’ (Pitelis Citation2012; Stam and Spigel Citation2016), ‘knowledge ecosystem’ (Van Der Borgh et al. Citation2012; Clarysse et al. Citation2014), ‘service ecosystem’ (Vargo, Wieland, and Akaka Citation2015), platform ecosystem” (Gawer and Cusumano Citation2014). Each of these notions of ecosystems differs from the focus on the types of partners involved and the nature of the proposition of value at stake. As illustrated by , the literature mostly concentrated on three of these concepts of ecosystems: innovation, business and entrepreneurial ecosystems. They followed similar trends. represents the annual number of articles reported in Google Scholar for search criteria including ‘innovation ecosystem’, ‘business ecosystem’ and ‘entrepreneurial ecosystem’. With a lag of a couple of years, all three notions follow the same growth trend. In the very early 2000, the Business Ecosystems set the pace, closely followed by Innovation Ecosystems. In 2013, Innovation Ecosystems took over as the dominating trend. In the early period, Entrepreneurial Ecosystems were less of a focus, but gathered more interest as a niche concept that has almost caught up with Business Ecosystems in recent years.

Figure 1. Annual number of articles reported in Google Scholar (search criteria ‘innovation ecosystems’, ‘business ecosystems’ and ‘entrepreneurial ecosystems’

Progressively, the literature clarified the differences between these main types of ecosystems. Whereas the notion of business ecosystem construct is generally used to analyse how a given organisation manages to capture value, notably by orchestrating its interactions with various stakeholders, the notion of innovation ecosystem shifts the focus to the issue of value creation by analysing how a structure of heterogeneous actors engaged in a process of knowledge and insight exchange, acts on its environment, develops new solutions, and co-creates value. In a more focused perspective, the notion of entrepreneurial ecosystem refers to a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship within a particular territory.

The notion of innovation ecosystems which receives today the most attention from academic scholars. This notion echoes many topics linked to innovation management. In an extensive review, Gomes et al. (Citation2018) list a wide variety of strategic management-related terms linked to innovation ecosystems.Footnote1 Borrowing the relevant word cloud procedure from Chesbrough and Bogers (Citation2014) on open innovation, we took 18 seminal papers on innovation ecosystems identified by Granstrand and Holgersson (Citation2020)Footnote2 and collected the academic concepts most frequently used in the abstracts and keywords of these papers. The word cloud of indicates a strong link with the other concepts of ecosystem (business and entrepreneurial) and the ‘co-’concepts (co-creation, competition co-evolution, and so on).

2. Innovation ecosystems and policies

Innovation ecosystems are drastically changing the way firms are designing, prototyping, testing and manufacturing new products and services. The uptake of these innovations requires intersectional investment and collaboration across a wide range of organisations on an unprecedented scale (Stefani et al. Citation2019).

Models of ‘co-innovation’ (Lee, Olson, and Trimi Citation2012) both at the technological and organisational levels are required along with a new set of adapted policies to support ecosystem-based innovations. Research equips organisational actors with frameworks for thinking, public policies, decision-making tools, means of action and indicators to bring about the necessary transformations in ecosystem innovation.

Ecosystems are indeed not static, but evolve as innovations develop (Attour and Burger-Helmchen Citation2014). While countries obsess about scaling up, i.e. to create the next generation of multinational enterprises (MNE), and capitalising on their S&T investments, well-organised innovation and business ecosystems may provide an interesting and potentially more agile model to consider as an alternative. However, how to scale up ecosystems remains a challenge to be surmounted, especially in the presence of complexity resulting from the extensive combination of knowledge and technology that spans widely across numerous sectors and disciplines. In this context, governments need to co-develop new, adapted and targeted public policies as well as appropriate regulations with the right stakeholders to ensure innovation success. Breaking down disciplinary and sectoral silos within ecosystems will be crucial. In line with these public policies and government programmes as mechanisms of their implementation, industrial processes and practices will need to be put in place to benefit from this multiplicity of discontinuous technologies that will soon be available to a vast array of sectors.

Innovation policies need to be adapted on the right scale of the systems they want to support. Recent work on innovation ecosystems explores their dynamic cycles (Cohendet, Simon, and Mehouachi Citation2020; Ghazinoory et al. Citation2020) and pinpoints the different needs that emerge with time. Innovation ecosystems exist both at a nationwide scale as well as in more geographically bounded areas. Therefore, the innovation policy concepts that are relevant are numerous. These include national innovation systems that encompass very broad aspects affecting learning/exploration of new knowledge, but also the diffusion of information and financial aid (Lundvall Citation1992). At a smaller scale, regional innovation systems, usually more turned towards production, can support innovation ecosystems (Asheim et al., Citation2011).

On a different level, sectoral innovation systems, i.e. more focused on a precise domain with an increased coopetition tension, are right for ecosystems with actors that are prone to market interaction already in possession of more advanced products or services (Malerba Citation2004). Finally, at the micro level, corporate innovation systems, often structured around platforms or entrepreneurship policies, may exist (Granstrand and Holgersson Citation2020; Isckia, De Reuver, and Lescop Citation2020). However, this last type of ecosystem may be less in need of innovation policies, or with the limitation of policies to supervise the position of the leading actor in the ecosystems and avoid monopole behaviours.

Further work is needed to understand the organisational structures of innovation ecosystems and how these are managed in order to accelerate and improve the innovation process and lead to better economic development and wealth creation. The goal of this special issue is therefore to provide a critical review of the past and current innovation policies and practices within and outside of innovation ecosystems in order to assess their appropriateness and effectiveness.

3. Overview of the special issue

While intense efforts of clarification have been made in the academic literature to distinguish between the concept of system and ecosystem, and between the different forms of ecosystems, very few academic works have addressed the issues of how these different forms of ecosystems are interacting in a dynamic perspective, or of how the notion of a dynamic ecosystem could emerge from the static frame of a system approach. The five articles that compose this special issue precisely aim at adding to this literature by highlighting the interplay between different types of innovation systems. A common thread among the five papers of the special issue is the recognition of the need to develop new lenses to formally account for adaptative behaviour within clusters, networks or regional innovation systems using the ecosystem metaphor. In essence, the five papers build upon these fields of the literature, by adding various complexity dimensions (relationships, knowledge, systems, etc.). As suggested by Boyer, Rondé, and Ozor (Citation2021) ‘the diversity and heterogeneity of agents, the complexity of relationships, and new forms of organisation (underground, middleground, and upperground) are the main characteristics of innovation ecosystems, in contrast to more traditional concepts like clusters or networks’.

The work of Rong et al. (Citation2021) intends to explore this theoretical and practical gap with a focus on the regional innovation ecosystems in China. Their work shows how to build on the relatively static views associated with regional, sectoral and national innovation systems (RIS, SIS and NIS), in order to construct the dimensions of regional innovation ecosystems (RIE) that take into account not only economic but also social factors. Maintaining links to RIS and SIS, these intertwined, dynamic and coevolving RIEs offer a strong value network to the actors of the ecosystem, and all together, they constitute the NIS as a whole. The findings also highlight how appropriate and well-informed governmental supports to these RIEs can significantly boost the national innovation system.

Based on a field study by Mazzoni and Lazzeretti (Citation2021) present how sectoral interactions can lead to the emergence and reinforcement of an entrepreneurial ecosystem and to better innovation management. The case-study based on 24 entrepreneurs shows that the innovation ecosystems allow better coordination, cooperation and cognition between the actors. This paper bridges the gap between complex adaptative systems (CAS) and entrepreneurial ecosystems. In contrast to Rong et al. (Citation2021), for this study, it is the entrepreneurship ecosystem lens that is not dynamic enough to account for the emergence of an entrepreneurship order. The authors categorise the entrepreneurial properties around three spheres (‘cognition’, ‘coordination’, ‘cooperation’) and explain their dynamic generative process, underlining the necessity to embrace a holistic unit of analysis, to fully understand the entrepreneurial emergent order. As the authors suggest, ‘each component acts following its “genetic heritage” but modifies its individual’, these modifications are therefore more akin to ‘genetic mutations’. As theories build upon each other, we suspect that entrepreneurship ecosystem, and innovation ecosystem theories may very likely borrow from CAS in the future to properly model such mutations and their impact.

It is accepted that the complexity of a system is both a source of richness and value creation, and a potential limit to good interaction (Heraud, Kerr, and Burger-Helmchen Citation2019). Organisations most probably adapt their behaviour to overcome these limitations. The study of such mutations is indeed suggested in the conclusion of the third paper of this special issue: Reischauer, Güttel, and Schüssler (Citation2021) recommend to study how Technology Transfer Organisations (TTOs) change their ‘designs [activities and structure] with respect to ecosystem evolution’. Their work takes a close look at the role of intermediary organisations and how their design can be better aligned with the ecosystems. They argue that coupling, specialisation, centralisation, and formalisation are the key structural dimensions of TTOs. The authors propose some key points to ensure a better governance and design of TTOs interacting with ecosystems. For instance, when the complexity of the solution sought warrants to search far and wide for new non-local knowledge, these TTOs are likely to play an important intermediary role within inter-RIE networks in the first paper of this special issue.

The smaller local innovation ecosystem studied in the fourth paper is a perfect microcosm of the RIE, entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystems studied in the other contributions to this special issue. Taking a quantitative approach, on more micro data, Boyer, Rondé, and Ozor (Citation2021) show how the local innovation ecosystem brings together a set of heterogeneous actors, leading to a higher diversity of outcomes for those firms. The study covers ecosystems related to health and nutrition, green chemistry, agro-sourced materials, fashion and textiles and digital/IoT, offering a large spectre of results. The paper empirically shows that the ‘innovation ecosystem impacts adaptive capacities of firms’, hence contributing the ‘mutations’ mentioned above, but also rendering the local innovation ecosystem more resistant to shocks. In particular, the results highlight that firms belonging to local innovation ecosystems centred on innovation parks are both more innovative and more technologically diversified than others.

Finally, Gifford, McKelvey, and Saemundsson (Citation2021) study the co-evolution of an entrepreneurial ecosystem and innovation policies in the Swedish maritime system. The authors propose a governance model where the policy activity (top-down) and entrepreneurial activity (bottom-up) are interrelated to build an effective innovation ecosystem, promoting both public and private returns. This last paper of the special issue echoes the first in that it promotes a mixed-driven policy approach that encompasses both purely policy-driven and spontaneously driven policy approaches. Focusing partly on sustainable development goals within the knowledge-intensive innovation ecosystem, the authors argue that ‘the existing actors need to be incentivised to change their business to accommodate sustainable development’, ergo favouring a beneficial ‘mutation’ for the ecosystem. This of course requires experimentation, but also exploring policies in other sectors. As a consequence, adaptation and sustainability of innovation ecosystems requires intersectoral in addition to inter-RIE.

Those papers highlight the variety of interactions at the heath of innovation ecosystems, but also the numerous interactions with a more global environment. Those interactions impact the structure and governance of ecosystems, creating spaces for improvisation and creation of new routines or reshaping of existing routines. The circumstances of those evolutions are among the next challenges research needs to answer about innovation ecosystems (Attour et al. Citationforthcoming).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Strategic Management is increasingly taking ecosystems into account. It is or will undoubtedly be a central strategic concept in the coming years. The inclusion of the term into the mainstream strategic management literature is, however, quite recent. Many strategic books, handbooks and encyclopædia only recently acknowledged the concept of innovation ecosystems or ecosystems in general. For instance, Faulkner and Campbell (Citation2006) handbook on strategy do not mention ecosystems, and in the 1800 pages of Augier and Teece (Citation2020) encyclopædia of strategic management, only business ecosystems appear, only hinting at innovation ecosystems as examples around leading technology firms such as Apple.

2 The papers are (Adner Citation2006; Autio and Thomas Citation2014; Bomtempo, Chaves Alves, and De Almeida Oroski Citation2017; Carayannis and Campbell Citation2009; Dattée, Alexy, and Autio Citation2018; Gastaldi et al. Citation2015; Gobble Citation2014; Gomes et al. Citation2018; Guerrero et al. Citation2016; Jackson Citation2011; Kukk, Moors, and Hekkert Citation2015; Nambisan and Baron Citation2013; Scozzi, Bellantuono, and Pontrandolfo Citation2017; Still et al. Citation2014; Tamayo-Orbegozo, Vicente-Molina, and Villarreal-Larrinaga Citation2017; Tsujimoto et al. Citation2018; Walrave et al. Citation2018; Witte et al. Citation2018) . The words corresponding to a limited or specific application of the ecosystems e.g. automobile or chemistry are not taken into account, we kept only the academic concepts.

References

- Adner, R. 2006. “Match Your Innovation Strategy to Your Innovation Ecosystem.” Harvard Business Review 84 (4): 98–107.

- Adner, R. 2016. “Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable Construct for Strategy.” Journal of Management 43 (1): 39–58. doi:10.1177/0149206316678451.

- Asheim, B. T., R. Boschma, and P. Cooke. 2011. “Constructing Regional Advantage: Platform Policies Based on Related Variety and Differentiated Knowledge Bases.” Regional Studies 45 (7): 893–904. doi:10.1080/00343404.2010.543126.

- Attour, A., C. Beaudry, T. Burger-Helmchen, and P. Cohendet. forthcoming. “From Improvisation to Routines: How Ecosystems Evolve under Special Circumstances.” International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management.

- Attour, A., and T. Burger-Helmchen. 2014. “Écosystèmes et modèles d’affaires: Introduction.” Revue d’Economie Industrielle 146: 11–25. doi:10.4000/rei.5784.

- Augier, M., and D. J. Teece. 2020. The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management + Ereference. 2018 édition. 1st ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Autio, E., and L. D. W. Thomas. 2014. “Innovation Ecosystems.” In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management, edited by M. Dodgson, D. M. Gann, and N. Phillips, 204–228. Oxford University Press.

- Bassis, N. F., and F. Armellini. 2018. “Systems of Innovation and Innovation Ecosystems: A Literature Review in Search of Complementarities.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 28 (5): 1053–1080. doi:10.1007/s00191-018-0600-6.

- Bomtempo, J.-V., F. Chaves Alves, and F. De Almeida Oroski. 2017. “Developing New Platform Chemicals: What Is Required for a New Bio-based Molecule to Become a Platform Chemical in the Bioeconomy?” Faraday Discussions, the Royal Society of Chemistry 202: 213–225. doi:10.1039/C7FD00052A.

- Boyer, J., P. Rondé, and J. Ozor. 2021. “Local Innovation Ecosystem: Structuralisation and Impact on Adaptive Capacity of Firms”. Industry and Innovation. Routledge. doi:10.1080/13662716.2020.1856047.

- Bresnahan, T., A. Gambardella, and A. Saxenian. 2001. “‘Old Economy’inputs for ‘New Economy’outcomes: Cluster Formation in the New Silicon Valleys.” Industrial and Corporate Change 10.4: 835–860. doi:10.1093/icc/10.4.835.

- Carayannis, E. G., and D. F. J. Campbell. 2009. “‘Mode 3ʹ and ‘Quadruple Helix’: Toward a 21st Century Fractal Innovation Ecosystem.” International Journal of Technology Management 46 (3/4): 201. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374.

- Chesbrough, H., and M. Bogers. 2014. “Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an Emerging Paradigm for Understanding Innovation.” In New Frontiers in Open Innovation, edited by H. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, and J. West, 3–28, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Clarysse, B., M. Wright, J. Bruneel, and A. Mahajan. 2014. “Creating Value in Ecosystems: Crossing the Chasm between Knowledge and Business Ecosystems.” Research Policy 43 (7): 1164–1176. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2014.04.014.

- Cohendet, P., L. Simon, and C. Mehouachi. 2020. “From Business Ecosystems to Ecosystems of Innovation: The Case of the Video Game Industry in Montréal.” Industry and Innovation 1–31. Routledge. doi:10.1080/13662716.2020.1793737.

- Dattée, B., O. Alexy, and E. Autio. 2018. “Maneuvering in Poor Visibility: How Firms Play the Ecosystem Game When Uncertainty Is High.” Academy of Management Journal 61 (2): 466–498. doi:10.5465/amj.2015.0869.

- Faulkner, D. O., and A. Campbell. 2006. The Oxford Handbook of Strategy: A Strategy Overview and Competitive Strategy. New ed. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

- Gastaldi, L., F. P. Appio, A. Martini, and M. Corso. 2015. “Academics as Orchestrators of Continuous Innovation Ecosystems: Towards a Fourth Generation of CI Initiatives.” International Journal of Technology Management 68 (1–2): 1–20. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2015.068784.

- Gawer, A., and M. A. Cusumano. 2014. “Industry Platforms and Ecosystem Innovation.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 31 (3): 417–433. doi:10.1111/jpim.12105.

- Ghazinoory, S., A. Sarkissian, M. Farhanchi, and F. Saghafi. 2020. “Renewing a Dysfunctional Innovation Ecosystem: The Case of the Lalejin Ceramics and Pottery.” Technovation 96–97: 102122. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2020.102122.

- Gifford, E., M. McKelvey, and R. Saemundsson. 2021. “The Evolution of Knowledge-intensive Innovation Ecosystems: Co-evolving Entrepreneurial Activity and Innovation Policy in the West Swedish Maritime System.” Industry and Innovation 1–26. Routledge.

- Gobble, M. M. 2014. “Charting the Innovation Ecosystem.” Research-Technology Management 57 (4): 55–59. Routledge.

- Gomes, L. A., V. De, A. L. F. Facin, M. S. Salerno, and R. K. Ikenami. 2018. “Unpacking the Innovation Ecosystem Construct: Evolution, Gaps and Trends.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 136: 30–48. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.009.

- Granstrand, O., and M. Holgersson. 2020. “Innovation Ecosystems: A Conceptual Review and A New Definition.” Technovation 90–91: 102098. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2019.102098.

- Guerrero, M., D. Urbano, A. Fayolle, M. Klofsten, and S. Mian. 2016. “Entrepreneurial Universities: Emerging Models in the New Social and Economic Landscape.” Small Business Economics 47 (3): 551–563. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9755-4.

- Heraud, J.-A., F. Kerr, and T. Burger-Helmchen. 2019. Creative Management of Complex Systems. 1 ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-ISTE.

- Isckia, T., M. De Reuver, and D. Lescop. 2020. “Orchestrating Platform Ecosystems: The Interplay of Innovation and Business Development Subsystems.” Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 32 (2): 197–223. doi:10.3917/jie.032.0197.

- Jackson, D. 2011. What Is an Innovation Ecosystem. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation.

- Kukk, P., E. H. M. Moors, and M. P. Hekkert. 2015. “The Complexities in System Building Strategies — The Case of Personalized Cancer Medicines in England.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 98: 47–59. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2015.05.019.

- Lee, S. M., D. L. Olson, and S. Trimi. 2012. “Co-innovation: Convergenomics, Collaboration, and Co-creation for Organizational Values.” Management Decision 50 (5): 817–831. doi:10.1108/00251741211227528.

- Lundvall, B.-Å., ed. 1992. National Systems of Innovation: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. London: Pinter Publishers. (Accessed 14 February 2021). available at https://vbn.aau.dk/en/publications/national-systems-of-innovation-towards-a-theory-of-innovation-and

- Malerba, F., Ed. 2004. Sectoral Systems of Innovation: Concepts, Issues and Analyses of Six Major Sectors in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511493270.

- Mazzoni, L., and L. Lazzeretti. 2021. “Entrepreneurship in the Current Techno-economic Landscape: What are the Emerging Styles? Some Evidences from a Field Study on Tuscany”. Industry and Innovation. Routledge. doi:10.1080/13662716.2020.1856047.

- Metcalfe, J. S. 1995. “Technology Systems and Technology Policy in an Evolutionary Framework.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 19.1: 25–46.

- Moore, J. F. 1993. “Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition.” Harvard Business Review 71.3: 75–86.

- Nambisan, S., and R. A. Baron. 2013. “Entrepreneurship in Innovation Ecosystems: Entrepreneurs’ Self–Regulatory Processes and Their Implications for New Venture Success.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37 (5): 1071–1097. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00519.x.

- Pitelis, C. 2012. “Clusters, Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Co-creation, and Appropriability: A Conceptual Framework.” Industrial and Corporate Change 21 (6): 1359–1388. doi:10.1093/icc/dts008.

- Reischauer, G., W. H. Güttel, and E. Schüssler. 2021. “Aligning the Design of Intermediary Organisations with the Ecosystem.” Industry and Innovation 1–26. doi:10.1080/13662716.2021.1879737.

- Rong, K., Y. Lin, J. Yu, Y. Zhang, and A. Radziwon. 2021. “Exploring Regional Innovation Ecosystems: An Empirical Study in China.” Industry and Innovation 1–25. Routledge.

- Scozzi, B., N. Bellantuono, and P. Pontrandolfo. 2017. “Managing Open Innovation in Urban Labs.” Group Decision and Negotiation 26 (5): 857–874. doi:10.1007/s10726-017-9524-z.

- Stam, F. C., and B. Spigel. 2016. “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems.” USE Discussion paper series 16.13.

- Stefani, U., F. Schiavone, B. Laperche, and T. Burger-Helmchen. 2019. “New Tools and Practices for Financing Novelty: A Research Agenda.” European Journal of Innovation Management 23 (2): 314–328. doi:10.1108/EJIM-08-2019-0228.

- Still, K., J. Huhtamäki, M. G. Russell, and N. Rubens. 2014. “Insights for Orchestrating Innovation Ecosystems: The Case of EIT ICT Labs and Data-driven Network Visualisations.” International Journal of Technology Management 66 (2/3): 243. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2014.064606.

- Tamayo-Orbegozo, U., M.-A. Vicente-Molina, and O. Villarreal-Larrinaga. 2017. “Eco-innovation Strategic Model. A Multiple-case Study from A Highly Eco-innovative European Region.” Journal of Cleaner Production 142: 1347–1367. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.11.174.

- Torre, A., and J.-B. Zimmermann. 2015. “Des clusters aux écosystèmes industriels locaux.” Revue d’économie industrielle 152: 13–38. doi:10.4000/rei.6204.

- Tsujimoto, M., Y. Kajikawa, J. Tomita, and Y. Matsumoto. 2018. “A Review of the Ecosystem Concept — Towards Coherent Ecosystem Design.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 136: 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.06.032.

- Van Der Borgh, M., M. Cloodt, A. Georges, and L. Romme. 2012. “Value Creation by Knowledge‐based Ecosystems: Evidence from a Field Study.” R&D Management 42.2: 150–169. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9310.2011.00673.x.

- Vargo, S. L., H. Wieland, and M. A. Akaka. 2015. “Innovation through Institutionalization: A Service Ecosystems Perspective.” Industrial Marketing Management 44: 63–72. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.10.008.

- Walrave, B., M. Talmar, K. S. Podoynitsyna, A. G. L. Romme, and G. P. J. Verbong. 2018. “A Multi-level Perspective on Innovation Ecosystems for Path-breaking Innovation.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 136: 103–113. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.04.011.

- Witte, P., B. Slack, M. Keesman, J.-H. Jugie, and B. Wiegmans. 2018. “Facilitating Start-ups in Port-city Innovation Ecosystems: A Case Study of Montreal and Rotterdam.” Journal of Transport Geography 71: 224–234. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.03.006.