?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The teaching and learning that takes place in clinical settings has a significant influence on the practice of future health professionals. This article describes the use of a logic model and case study methodology to evaluate an online and face-to-face video-club, a novel professional development activity designed with the aim of improving clinical educators’ teaching practice. A video-club brings together a small group of clinical educators who have a shared interest in exploring their educator role through collective inquiry, using video-recordings of their authentic teaching practices as stimuli for learning discussions. The article focuses on the extent to which the learning design was both implemented and working as intended and offers an examination of proximal outcomes and an initial examination of distal outcomes. The authors claim that the video-club’s core activity – watching and discussing the video-excerpts – was successful in generating the requisite ‘teacher talk’ necessary to influence clinical educators’ teaching practices. The examination of the video-clubs’ impact on clinical educators’ practice was promising and justifies a larger study to fully investigate the intervention’s effectiveness. In order for the video-club to grow and thrive, systemic changes, particularly at the level of policy and ‘culture’, are likely to be required.

Introduction

For clinicians to become effective teachers, they initially need to be taught how to teach and then commit to continually improve as educators (Bearman et al. Citation2018; Irby Citation2014; Steinert et al. Citation2016; Tai et al. Citation2016). Reviews of ‘faculty development’ activities in medical education highlight short-term professional development offerings, such as face-to-face workshops, as a common means of trying to impact clinical educator effectiveness (Olanrewaju and Thistlethwaite Citation2013; Steinert et al. Citation2006, Citation2016). However, a review of the impact of ‘continuing medical education’ suggests that any resulting improvements in practice from these types of professional development are likely to be small (Forsetlund et al. Citation2009).

In a published paper, we have described a novel professional development activity that we designed for Australian general practice clinical educators that broke with the short-term instructor-led workshop format, which we thought had the potential to impact strongly on their teaching practice (Clement et al. Citation2020). We labelled this activity a video-club, a term appropriated from the broader education literature (Sherin Citation2000). In essence, a video-club brings together a small group of clinical educators who have a shared interest in exploring their educator role over time and supports their learning through collective inquiry, using video-recordings of their authentic teaching practices as stimuli for discussion.

Although video-clubs had been used successfully in the education field, we thought it important to demonstrate that an unfamiliar and potentially threatening intervention was acceptable to general practice clinical educators, whose teaching practice is rarely the focus of intense scrutiny. We also aimed to establish whether the intervention could be operationalised according to its learning design, prior to scaling-out and investigating for stronger evidence of impact. These aims align with the view that trialling innovative professional development on a small scale should precede a comprehensive outcome evaluation (Borko Citation2004; Hill, Beisiegel, and Jacob Citation2013; Institute of Education Sciences & National Science Foundation Citation2013; Patton Citation2008).

In this article we describe the use of a logic model to evaluate an online and a face-to-face video-club, focusing on the extent to which the learning design was both implemented and working as intended, offering an examination of proximal outcomes and an initial examination of distal outcomes.

The intervention

The video-club’s learning design was strongly influenced by both the reviewed research and our experiential knowledges, which we depicted as a theory-based logic model (Kellogg Foundation Citation2004). depicts in graphic form the final iteration of the logic model, which includes minor revisions resulting from insights gained through implementing the video-clubs (Peyton and Scicchitano Citation2017). These revisions are either discussed below or explained in Clement et al. (Citation2020).

Figure 1. Logic model of the video-club interventiona.

An outline of the intervention follows, which, when considered with the narrative description of the logic model in the earlier paper (Clement et al. Citation2020), covers the requisite information for reporting an intervention outlined by Phillips et al. (Citation2016) and Hoffmann et al. (Citation2014).

Setting

The video-clubs were trialled in the training footprint of Murray City Country Coast (MCCC) General Practice (GP) Training, one of nine Regional Training Organisations contracted by the Australian Department of Health to deliver the Australian GP Training program (Australian Government Department of Health Citation2018). In this program, the bulk of registrars’ training takes place in accredited training posts, where trainees work under the supervision of experienced general practitioners; that is, clinical educators who are available to observe, work with, support, and teach the trainees in formal and informal settings. As well as responding to trainees’ immediate learning needs that arise during consultations with patients, clinical educators must provide an hour of ‘protected teaching’ each week during the first 12 months of training (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners Citation2017). In order to gain accreditation as supervisors, these clinical educators meet eligibility criteria rather than competency standards, and are required to participate in a minimal amount of teaching-related professional development each year, typically organised as face-to-face, instructor-led workshops by ‘host’ Regional Training Organisations.

Video-club participants

Clinical educator participants and two Medical Educator (ME) facilitators were recruited from within MCCC’s training footprint to participate in the two video-clubs. All participants provided both verbal and written informed consent. The two facilitators were purposefully recruited from MCCC’s pool of MEs, based on their clinical experience and expertise in education. The facilitators received a half-day orientation to video-clubs and the facilitator role, with an emphasis on nurturing reflective dialogue and enabling the groups to be self-directed in their learning (Clement et al. Citation2020; Heron Citation1999). provides details of the clinical educator and facilitator participants. Pseudonyms are used to refer to participants throughout the article.

Table 1. Demographic details of the video-club participants.

There were four clinical educators in the face-to-face video-club and six in the online version; close to the mean size of video-clubs in the published research and congruent with the evidence on optimal size for small group learning (Dennick and Spencer Citation2011). The project’s funding determined that the video-clubs were a time-limited activity, which placed restrictions on the number of participants, as an important part of the intervention was that participants should present video-excerpts from their teaching as triggers for discussion at one meeting.

In both video-clubs, the clinical educators had a range of educator and general practice experience, but there were no absolute novices. All had had previous experience of using video-recordings as a learning aid, typically for reviewing their own or others’ consultations with patients. Most participants were Australian-trained, with few having a teaching qualification. Overall, there were more male participants, with the online group being particularly unbalanced. The online group also had more participants working in metropolitan areas. The clinical educators were remunerated for attending the video-clubs, as they would have been for attending MCCC’s approved professional development activities.

The two facilitators had significant clinical and education experience. They both had a teaching qualification, but were different by sex, where they had trained, and the online facilitator had recently given up his role as a clinical educator. The facilitators were paid for their work.

The video-clubs: structure and timing

Each facilitated video-club met six times, once a month, over a six-month period, between October 2018 and March 2019. Each meeting ran for one hour, except for the first and final meetings, which ran for 90 minutes, to enable setting-up and adjourning activities. The video-clubs had a basic tripartite structure; in essence, a beginning, middle, and an end. At the heart of each meeting the participants watched and discussed short video-excerpts from a participant’s teaching, typically from ‘protected teaching’ sessions, although not exclusively, as it is both easier to record and for clinical educators to accentuate their teacher role when patients are not present. The video-excerpts were complemented by a verbatim transcript, created by a member of the research team (TC). (An exemplar transcript is included as an online supplemental file. Although not as rich as a video-recording, it may give readers a sense of what the participants watched and discussed.) The pattern of providing context to a video-clip, watching and discussing it was repeated twice at each meeting. At the end of each meeting, the participants shared what they had learnt and identified any implications for their practice. Apart from the inaugural meeting, each video-club began with participants being invited to make reflective comments about the previous meeting and share relevant stories about teaching and learning from any interim teaching.

Researchers as participants

TC, a social researcher, attended all video-club meetings, and DH, a general practitioner and clinical educator, participated in the online version, with Gold’s (Citation1958) ‘participant as observer’ role usefully describing their contributions. That is, both were known as members of the research team and actively participated in the meetings. We chose not to minimise the influence of the researchers but thought that they may have complementary educational expertise that may help to shape and enhance the other participants’ understandings of teaching and learning (Sherin Citation2003). Primarily, the researchers brought additional perspectives for interpreting the video-excerpts to supplement the other participants’ frames of reference.

DH showed excerpts of his teaching at the inaugural online video-club, an action mirrored by Anne, the face-to-face facilitator. This was a change to the initial learning design; an outcome of a discussion at the facilitators’ orientation, illustrating how stakeholders’ views can be incorporated into the design (Peyton and Scicchitano Citation2017). In showing video-excerpts of their teaching first, we thought that Anne and DH were likely to create a learning environment that was initially safer for the other participants and that they would also be able to demonstrate the necessary risk-taking required for their own learning and the promotion of learning for the other participants (Molloy and Bearman Citation2019).

Timing of meetings

Although the clinical educator participants were the key drivers in the scheduling of the video-clubs, fitting the meetings into their busy schedules, we were adamant that as a valued ‘work activity’ it should not intrude on their ‘free time’ (e.g., as a late ‘after hours’ meeting) but be embedded in or linked to their work time (see Le Cornu and Ewing Citation2008). The online meetings were scheduled at the start of the working day and the face-to-face meetings at its end; that is, prior to consulting or having finished consulting with patients.

Modes of delivery

Before the first online meeting, preparatory work was undertaken with each participant by TC to ensure that the technology worked well. Although there are many similarities between online and face-to-face groups, there are some important differences in how they operate (Lantz-Andersson, Lundin, and Selwyn Citation2018). All the online participants experienced ‘online socialisation’; learning how to use and become accustomed to the technology, and adjusting to the social cues, which are different to those in face-to-face meetings (Dennick and Spencer Citation2011). So, as well as being skilled in facilitating small groups, the online facilitator also needed the specific knowledge and abilities to facilitate an online group (Gill, Parker, and Richardson Citation2005). (The more frequent use of video-conferencing during the COVID-19 pandemic has made many people more comfortable with online meetings.)

Underpinning pedagogical ideas

The video-club’s learning design is intended to be pedagogically rich (Billett, Noble, and Sweet Citation2018), drawing on a number of educational approaches, such as adult learning, constructivism, and situated learning (Kaufman and Mann Citation2014); best-practice evidence from systematic reviews of professional development (Anderson and Henderson Citation2004; Beach Citation2012; Hawley and Valli Citation1999; Maher et al. Citation2018; Olanrewaju and Thistlethwaite Citation2013; Steinert et al. Citation2006, Citation2016); and specific ideas about ‘teacher talk’ (Loughran Citation2006).

Discussing video-excerpts of each other’s teaching is a pedagogically rich activity because it encompasses all five types of activity in Caladine’s (Citation2008) Learning Activities Model. The video-excerpts constitute the provision of authentic material (i) with which the participants interact (ii). In discussing the video-excerpts, the participants interact with one another (iii) and a knowledgeable facilitator (iv) permitting reflection, critical thinking, comparing knowledge and experiences, and so on (v).

Loughran’s (Citation2006) concept of ‘teacher talk’ is similar to Lord’s (Citation1994) notion of ‘critical colleagueship’, Prestridge’s (Citation2009) writing on ‘collegial dialogue’, and Fullan’s (Citation2016) description of ‘professional learning communities’. Improvement in teaching practice results from clinical educators having ongoing opportunities to meet and inquire into practice together, raising questions about their own and others’ teaching, attending to these questions, and sometimes answering them. The video-excerpts allow the participants to expose their actual practices to other clinical educators, so that they can learn with and from each other. ‘Teacher talk’ manifests itself in observable ‘behaviours’, such as a critical stance towards teaching, confronting traditional practice, a willingness to reject flimsy reasoning, and self-reflection (Lord Citation1994).

Methods/design

In addition to developing a logic model, we drew on case study methodology to guide our data collection and approaches to data analysis (Yin Citation2014). We used an embedded two-case design, with the video-club being the ‘unit of analysis’. The embedded design allowed us to undertake a finer-grained analysis at the individual participant level. Framing the two cases from descriptive, exploratory, and explanatory perspectives enabled us to address multiple interests. Our primary interest was exploratory, investigating the feasibility of implementing the learning design of a novel professional developmental activity. Describing the intervention in sufficient detail meets reporting guidelines, enabling others to implement video-clubs with fidelity (Phillips et al. Citation2016). A theory-based logic model offers an explanation of how the video-club should work, against which the empirical data can be compared.

The research team

In addition to the aforementioned ‘participant as observer’ roles, the members of the research team brought diverse health, education, and research perspectives to the project, including both insider and outsider standpoints. EL and DH are experienced general practitioners, clinical educators, and medical educators. EM is a medical education researcher with expertise in workplace learning, faculty development, and qualitative methods. TC is a social scientist who has worked in the postgraduate medical education environment for eight years.

Data collection instruments and purpose

We collected multiple sources of qualitative data to ascertain whether the learning design was implemented as intended and provide indicative evidence of the hoped-for outcomes. Video-recordings were made of the video-club meetings, a record of how the facilitators enacted their role, and how participants discussed the video-excerpts, shared perceptions of what had been learned, and stated how any learnings had been subsequently applied. The final video-club meetings were extended by 30 minutes to capture participants’ concluding thoughts about the intervention (Orsmond and Cohn Citation2015). Guided by a semi-structured questionnaire, facilitators made an audio-recording after each meeting, reflecting on different facets of the meetings, such as how they enacted their role, perceived the learning climate, and judged how well the task of watching the video-excerpts stimulated discussions on teaching and learning. (The semi-structured questionnaire is available as an online supplemental file.) TC similarly wrote ‘fieldnotes’ after each meeting. These complementary data sources were used to corroborate and challenge the respective findings (Barbour Citation2001; Richardson and Pierre Citation2005; Yin Citation2014).

Data analysis and philosophical assumptions

It should be apparent that utilising a logic model demands that we retain an ontological realism, as it offers an explanation of how the video-clubs work (or not) to produce the observed outcomes (Yin Citation2014). For example, that we can describe a video-club’s learning climate and claim that participants’ perceptions of that climate – for instance, in terms of psychological safety – have consequences for both how they engage with one another and their learning. At the same time, our account of the research holds on to the epistemological constructivism that underpins the video-club intervention. That is, our descriptions, explanations, and understandings are our constructions. Maxwell (Citation2012) argues that the integration of ontological realism and epistemological constructivism is a common-sense basis for conducting social research.

Coding and analysing the data

Verbatim transcripts were produced from the audio- and video-recordings. We used deductive and inductive approaches to coding the different textual sources, drawing on template analysis (King Citation1998), and employed two deductive and inductive analytic strategies outlined by Yin (Citation2014); ‘relying on theoretical propositions’ and ‘working the data from the ground up’. Template analysis was appropriate because we held a number of a priori ‘ideas’ about how the learning design should work and how ‘teacher talk’ – a ‘measure’ of how well the intervention was working – would manifest. We created a series of initial coding templates with a small number of higher-order a priori codes that were determined from the research questions and the reviewed literature. In presenting our findings, we indicate how we used a priori codes in our analysis.

We coded the transcripts of the video-club meetings in ways that enabled coarser- and finer-grained analysis (Chi Citation1997). We labelled any time a participant spoke an ‘utterance’, which could be one word or a much longer contribution. An utterance was a basic analytic unit. Each utterance could be coded multiple times. Disaggregating an utterance allowed a finer-grained analysis of each participant’s ‘talk’, and a coarser-grained analysis was facilitated by aggregating the data. This is congruent with the use of an embedded case study, investigating individual data, aggregating data for each video-club, and making comparisons between the face-to-face and online video-clubs.

Our initial codes were revised as we analysed the data by inserting new codes, revising a priori codes, and deleting irrelevant a priori codes. Through this process we created a series of ‘final’ templates in a master codebook.

Subsequently, we used summative qualitative content analysis to quantify content in the transcripts (Chi Citation1997; Elo and Kyngäs Citation2008; Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005; Morgan Citation1993) that allowed us to compare this empirical data against the logic model and explore whether the learning design was working as intended. NVivo12 was used to assist in the coding and categorisation of the data (QSR International Citation2018). The platform’s ‘query tools’ were used to quantify the qualitative data.

The entire data set was available to the research team so that they could undertake different ‘readings’ of it (Mauthner and Doucet Citation1998). First, readings for familiarisation. Second, open readings to draw out individual interpretations, and thirdly, readings to apply the coding templates. The template coding was completed primarily by TC. EL used the templates to code data samples, which he discussed with TC. In line with our epistemological constructivism, our goal here was not ‘degree of concordance’, but to generate valuable discussion for refining the coding templates and generating analytic insights (Barbour Citation2001). The process of peer review (Creswell Citation2013) was a regular activity in team meetings that involved all the authors. We used the meetings to discuss immediate findings; compare, contrast, and challenge individual interpretations; and monitor the analytic and interpretative processes. These cycles of analysis and interpretation underscore that our exploration of the data was an iterative process, drawing on the analytic insights of the research team.

Results

Introduction

We begin the results section by highlighting two rhetorical devices that we have used in this section: one a commonplace format for reporting case studies, and the other a minor break with the dominant convention for presenting findings in an academic paper. We have chosen to present our findings primarily as a cross-case analysis (Yin Citation2014), a synthesis of the findings from the two video-clubs organised in relation to key elements of the logic model. Rather than present our findings in a discrete section, we have opted to weave description, analysis, and interpretation together seamlessly (Richardson and Pierre Citation2005). Being case studies, we describe some aspects of the video-clubs, but support our major claims with evidence, so that readers can evaluate them alongside the related argumentation.

Shape and structure of the video-club meetings and quantity of ‘talk’

We labelled the sections of the video-club’s tripartite structure as Teaching tales, Video-excerpts, and Learnings (described in The Intervention). shows the duration (in minutes) of these sections for each video-club and their mean duration.

Table 2. Duration of video-club meetings (in minutes) and meeting sub-sections.

The facilitators ensured that the meetings adhered closely to the allotted 60 minutes, with similar amounts of time being apportioned to the three sections in both video-clubs. The face-to-face meetings were a little longer, with most of this extra time being spent discussing the video-excerpts. As the online meetings preceded the start of the participants’ consulting day, there was a stronger imperative to finish on time.

reflects an aspect of the intervention’s tight–loose structure; its tightness, which stems from the allotted tasks to be completed in one hour. Watching and discussing the video-excerpts are the key learning activities. Either side of these activities, the facilitator’s role is to prompt participants to articulate what they have learnt, identify actions for their practice, tell teaching and learning stories arising from interim teaching sessions, and share any reflective comments about previous content. The meetings are ‘loose’ in the sense that what is discussed is not predetermined but triggered by what people ‘notice’ in the two three-to-four-minute video-excerpts.

Meeting via technology shapes how participants interact and engage with the intervention (Lantz-Andersson, Lundin, and Selwyn Citation2018). TC’s experience of the respective video-clubs was that they were qualitatively different, a finding that has been reported in other studies comparing face-to-face and video-conference meetings (see Delaney et al. Citation2004, for example). The face-to-face meetings had more over-talking and fewer silences and pauses. A crude indicator of ‘more talk’ in the face-to-face meetings is provided by the average ‘word count’ in the transcription documents, with about 1900 more words being transcribed (i.e., spoken) when compared with the online meeting (face-to-face: = 10,837 words per meeting; online:

= 8961). This additional ‘talk’ is not accounted for by the slightly longer face-to-face meetings. Although this aspect of the data suggests a minor difference in the way that the online and face-to-face modes operated, we claim that it did not impact on how the learning design functioned.

Talking about teaching and learning

In the learning design, the video-excerpts are stimuli presented to the participants. We borrowed the term ‘noticing’ from Van Es and Sherin (Citation2002) to describe the process through which the participants identify what they think is important in a video-excerpt. Each noticing is a response to the video-excerpt and is a starting point to the emergent discussion that follows. Mead’s ‘conversation of gestures’ (1934, cited in Stacey Citation2007) provides a close account of this emergent conversation. In articulating a noticing, a participant makes a ‘gesture’ to the other participants, which evokes a response from another participant. This response is a ‘gesture’ to both the original speaker and the other participants that evokes a further response, which continues as an unpredictable ongoing responsive process. This process is ‘managed’ by both the participants and the facilitator.

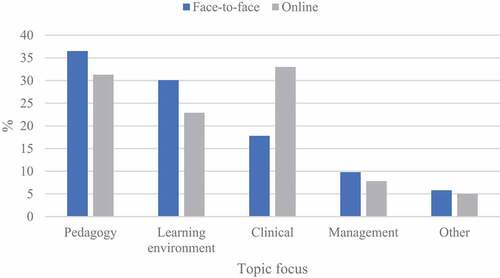

We coded the ‘noticings’ in participants’ utterances, beginning with three a priori categories identified by Sherin and Van Es (Citation2009); Climate, Management, and Pedagogy. Our final template included two additional categories: Clinical and Other. shows, by percentage, the extent to which participants’ discussions of the video-excerpts focused on the four primary ‘topics’ in the two video-clubs. This is a coarse-grained analysis of everyday discussions of what Schwab (1978, in Loughran Citation2006) calls ‘the commonplaces of pedagogical practice’ (23).

Figure 2. Topics discussed by video-club participants in response to video-excerpts by mode of delivery.

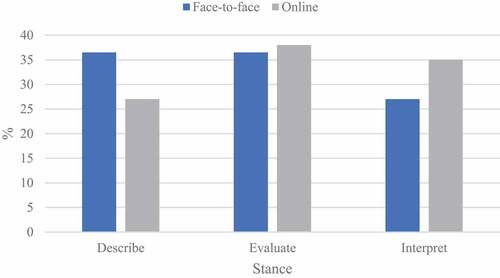

We additionally coded participants’ utterances for ‘stance(s)’, which are general approaches for making sense of the topics being discussed (Sherin and Van Es Citation2009). We used the Describe, Evaluate, and Interpret categories identified by Sherin and van Es as a priori codes. shows, by percentage for each video-club, the proportion of utterances related to discussing the video-excerpts for these three categories.

Figure 3. Percentage of utterances coded by stance when discussing video-excerpts by mode of delivery.

Although we think that it is crucial that clinical teachers adopt an interpretive stance, the relationship between the three stances is intricate. Description relates directly to ‘noticing’ and reflects the participants’ abilities to identify and differentiate between relevant teaching and learning events in the video-excerpts. This is influenced by their knowledge of teaching and learning and any expectations they have of the situation (Tanner Citation2006). Sound evaluation and interpretation relies on adequate description. Evaluation relates to participants’ positive and negative judgements about aspects of the video-excerpts, and interpretation provides explanations of what took place in the excerpts, both of which are based on their extant knowledge of teaching and learning and teaching experience. Participants’ reasoning about ‘noticings’ provides a window into their understandings of teaching and learning and an indication of how this knowledge might transfer to the teaching context (Stürmer, Könings, and Seidel Citation2013).

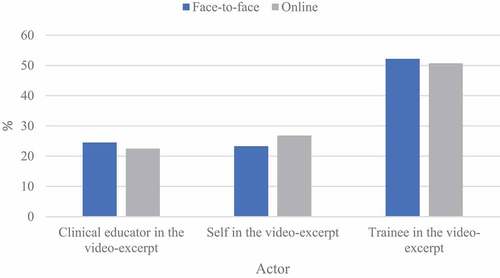

We further coded participants’ utterances for ‘Actors’ in the video-extracts; that is, whom the participants discussed, as a rudimentary indicator of the degree to which participants’ discussions were teacher- or learner- centred. shows by percentage for each video-club, the proportion of utterances focused on self (i.e., the presenting participant talking about him or herself), the supervisor, and the trainee.

We expected presenters to focus on their practice (self in the video) and the other participants to comment on the educator (supervisor in the video) but were less sure to what extent participants would comment on the trainees. Some general practice studies have commented on the teacher-centredness of clinical educators’ practices (Caird and Ogden Citation2001; Cantillon and de Grave Citation2012). This is likely due to a number of reasons. The ‘apprenticeship’ discourse positions trainees as the recipient of senior doctors’ expertise, and work pressures tend to impel a ‘quick fix’ rather than an exploration of underlying issues (Korthagen and Vasalos Citation2005). Beginning educators often have a view of teaching as transmissive (Loughran Citation2006), and clinical educators are unlikely to have their beliefs about teaching and learning as strongly challenged as education professionals are. Loughran (Citation2006) claims that getting inside learners’ heads is one of the more difficult pedagogic tasks, but it is crucial if clinical educators are to understand how trainees learn. TC consciously came to the video-club meetings with questions crafted to encourage participants to discuss aspects of the videos from a learner’s perspective, which is likely to have impacted on the (roughly) equal time given to discussing the teachers and learners. In the following example, a group of registrars were discussing an examination question. Having generated an initial list of differential diagnoses, the clinical educator asked them to narrow the list to three ‘likely’ differential diagnoses for the patient’s presentation. In the video-excerpt, interactions between the clinical educator and one registrar became heated. TC thought this was because the clinical educator failed to ‘get inside the learner’s head’.

What you’re trying to do is understand the learner’s perspective and that’s what you’ve picked up on. So, I was interested in what you picked-up in the transcript that makes you think that. And the reason I chose these two extracts was that the registrar was struggling with – in both – her understanding of the term ‘likely’. So, as the educator, what did you understand about her problem with the notion of ‘likely’? She had a particular understanding that seemed to be a barrier. (TC/F5/270219)

The three major coding categories of ‘Topic’, ‘Stance’, and ‘Actor’ provide a practical measure of ‘teacher talk’. complements the narrative in this section, listing the codes with corresponding definitions and illustrative quotations.

Table 3. Topics, stance, and actors: labels, definitions, and illustrative quotations.

We think it is reasonable to claim that the video-club’s core learning activity – watching and discussing the video-excerpts – was successful in triggering the requisite types of conversations that we think enable clinical educators to become better teachers. The video-excerpts were triggers for conversations about the content being taught, procedures and strategies for teaching the subject matter, organising the ‘educational environment’, and the social and material environment of the (protected) teaching session. In discussing these commonplaces of teaching, the participants articulated their related reasoning. As well as identifying and differentiating between teaching and learning events, participants made judgements and offered explanations about those events, and tried to make sense of them from their own and trainees’ perspectives.

Facilitator moves

The facilitator is a mediator between the video-club program and participants’ experience of it (Borko Citation2004; van Es et al. Citation2014). The logic model posits the facilitator’s role as being crucial to the success of the video-clubs, and we had some clear ideas about how it should be enacted, which we shared in the facilitator orientation. We believed facilitators needed to be in tune with the educational approaches that underpin the learning design and come to each video-club with the goal of activating learning rather than delivering any prearranged content (Sherin and Han Citation2004). They had to comprehend the goals of the video-club, help structure the learning experiences, enable substantive and respectful interactions between the participants, and establish a ‘community of inquiry’ (Beach Citation2012; Wells Citation1999). We purposefully recruited MEs with these ideas in mind and created an orientation program with the aim of encouraging this style of facilitation.

van Es et al. (Citation2014) use the term ‘facilitator moves’ to describe facilitators’ in-the-moment practices. We drew on Heron’s (Citation1999) work to create an initial coding template to categorise the video-club facilitators’ utterances in order to explore how they enacted their role. lists the final codes that were applied to the facilitators’ utterances, with definitions and illustrative quotations.

Table 4. Facilitator moves: labels, definitions, and illustrative quotations.

shows the frequency with which the codes in were applied to the facilitators’ utterances by meeting, and the overall proportion by which the codes were applied by facilitator. This data indicates that the facilitators enacted a variety of moves in co-creating the video-club endeavour and addressing the requisite activities and processes.

Table 5. Facilitators’ utterances coded as ‘moves’, by meeting and overall proportion (%).

Anne made more total utterances than Robert. Some of this is accounted for by the fact that more utterances were made in the face-to-face modality and that she presented her video-excerpts at the first meeting. (On average, about 100 more utterances were made at each face-to-face video-club. Face-to-face: = 224 utterances per meeting; Online:

= 121.) Anne was also more likely to drop the ‘pure’ facilitator role and engage as a ‘regular participant’, indicated by the higher Informative coding. In contrast, Robert’s reflection indicates a conscious holding back that encourages the group’s self-direction:

The most fruitful times were really when I just stepped-out and people naturally jumped-in with their comments and picked-up on each other’s points as well. My ‘noticings’ were actually picked-up, I think, by the group anyway, so I didn’t use them, or get them to shape the supervisors’ inputs. And again, I think this is my role as a facilitator, to focus on the supervisors’ [video-club participants] activities and encourage their interactions rather than to jump-in with my own structured process and task. (Robert/O2/211118)

We do not claim that withholding one’s comments is better than sharing them. Both facilitators remarked on how stimulating the video-excerpts were and wanted to join in the discussion. Robert’s reflection indicates the importance of providing space to learners (Molloy Citation2009), and the common occurrence, if one does ‘pause’, that a learner makes the point that the educator wanted to raise. ‘Jumping in’ to give the educator’s perspective, or ‘talking too much’, is closely aligned with ‘teaching as transmission’, which was notably a recurring topic for discussion in both video-clubs. The related ‘meta reflection’, that some of the issues that participants were discussing in the video-excerpts were also playing out in the video-clubs, was identified by both the video-club participants and the research team, generating a further resource for discussing teaching and learning.

The Schooling label was additionally created to code a small number of Anne’s utterances that relate to the ‘transmission of knowledge’, which were likely induced by her previous and current Medical Educator roles within the organisation. Although these comments are beyond the role of the facilitator as we initially described it, there are times when it is entirely appropriate for an educator to provide information and share one’s practice wisdom.

Nearly 70% of Robert’s utterances were comprised of the Prescriptive and Managing the Environment categories, both of which broadly relate to the smooth running of the video-club, the former being task oriented and the latter attending to its social aspects. The online meeting had specific challenges related to using video-conferencing technology, and the Managing the Environment code includes facilitator utterances about ‘connectivity’, which featured at the start of every meeting. In addition, there were times when the online meeting more or less ran itself. Managing the Environment also included the numerous occasions when Robert had to ratify the next speaker, who had silently indicated that he or she wanted to speak. In face-to-face meetings people either interjected or made use of superior visual cues to ‘decide’ who should speak.

We wondered whether the amount of prescriptive moves might reduce over time as participants became more familiar with the structure and took on some of the facilitation tasks. Remembering that the first meeting comprised a high volume of setting-up tasks, the data in may show a downward trend in the face-to-face video-club, but not in the online one. These numbers may reflect both the different modalities and/or the aforementioned differences in the ways the facilitators enacted their roles. The highly structured nature of the meetings, together with the tight one-hour timeline, ensured that some prescription was always likely to be needed.

Anne used the core Catalytic, Cathartic, and Confronting facilitator moves more than Robert, highlighting a more active role in this regard, either through style or perceived need. We make the case below that participants’ behaviour in both groups was congruent with the notion of reciprocal learning relationships (Le Cornu and Ewing Citation2008), which minimised the need for the facilitators to make these moves.

Overall, the comparison of the facilitators’ moves indicates slightly different patterns. We agree with van Es et al. (Citation2014) that one cannot isolate individual moves as being definitively more important than others in influencing outcomes, but suggest that it is the way in which the moves are used together that is likely to be important in supporting clinical educators’ learning. Like teaching, facilitating a video-club involves the simultaneous pursuit of multiple goals, which requires personal judgement. The data suggests that facilitators ensured the video-clubs maintained a common structure, and when taken as a whole, they both operated in a way that reflected our preferred facilitator orientation. These approaches supported the group engaging in a fruitful ongoing dialogue about teaching and learning.

Reciprocal learning relationships

The logic model identifies collaborative inquiry as a core video-club activity, indications of which are a commitment to reciprocity and reciprocal learning relationships (Le Cornu and Ewing Citation2008). Clearer manifestations of these concepts are participants sharing their own experiences, showing and discussing the video-recordings of their teaching, the comments they make, and the questions they ask.

We made the point above that asking a question or offering another perspective removes the need for the facilitator to ‘make a move’. In this quotation, Charles is both confronting and catalytic, sensitively challenging the transmissive style of teaching that had been a recurring focus of discussion and asking Thomas to elaborate his thoughts.

Thomas … can I just ask something? Thomas, you were saying that you felt that you talked a lot during that session … Do you look at that in a critical sense or do you think that is still a useful way, like, did you feel like the registrar was engaged with you when you were talking like that? ’Cause, we’ve talked about how a lot of us talk a lot, and we think that it can be useful, but maybe it’s not always useful. What’s your sense looking at it now and thinking about it? Is that, do you think that was a useful session? Did he get a lot out of it when you were talking like that? (Charles/O6/130319)

Contributions like this were common to both video-clubs and highlights how participants can contribute to others’ learning. This sits well with the underpinning constructivist and situative views of learning in the logic model (Putnam and Borko Citation2000; Wenger Citation1998). Learning takes place through a collaborative framework, where any new knowledge that participants take from the discussion arises from interaction between the participants (Bond and Barbara Citation2018; Le Cornu and Ewing Citation2008). As well as using the video-excerpts as a trigger for learning, the video-club itself is a resource for discussions about teaching and learning, where facilitators can model learner-centred practice, participants can observe one another’s contributions, trial novel forms of questioning, and reflect on and discuss these in vivo practices.

Outputs, outcomes, and impact

In the Introduction we stated that innovative professional development should be trialled on a small scale before undertaking a comprehensive outcome evaluation. Directly investigating whether clinical educators’ changed understandings of teaching and learning impact on their teaching practice and trainees’ learning will require an adequately resourced long-term project.

In our logic model we identified some basic outputs (e.g., number of video-club meetings), the proximal outcomes that are related to ‘teacher talk’ (e.g., reasoning about educational environments in new ways), which we think are a precursor to changes in practice (a distal outcome). In the final ‘impact’ column we identified some ambitious systems-related goals. In the Kellogg Foundation’s (Citation2004) model, distal outcomes should be attainable within one to six years, which are subsequently reflected in an intervention’s impact within seven to ten years. The Kellogg Foundation’s long-term perspective is congruent with an assumption in the logic model, derived from our review of the professional development literature, that lasting change will be a slow process (Anderson and Henderson Citation2004; Borko Citation2004).

We used data from the ‘Learnings’ and ‘Teaching tales’ sections of the video-clubs to support tentative claims in relation to the intervention’s intended outcomes; particularly that participants experienced changed understandings of teaching and learning that impacted on their practice. These section labels also served as broad categories for coding the data. The quotations in supplement those that follow.

Participation in the video-club resulted in a heightened consciousness of the teacher role that transferred to the workplace. In this quotation, the clinical educator implies that thinking about teaching and learning made him more aware of his teacher role in his next ‘protected teaching’ session.

Just like to thank Charles for his clip of the glandular fever teaching opportunity, and this week it happened to be at the same time I was recording my video footage with our registrar, and the first case was a woman who came in with tonsillitis, so I felt really primed to make this a really good learning opportunity. … So, I thought that was a valuable learning thing, which I probably would have managed differently in the teaching session if we hadn’t had the prior one. (George/O2/191118)

Participation in the video-club expanded participants’ repertoire of teaching procedures and strategies that they could either use in practice immediately or hold until the right opportunity arose. In the second face-to-face meeting, the group had watched a colleague use role play to simulate a ‘breaking bad news’ consultation with a trainee. Two meetings later, Edward reflected that this was an appropriate procedure to use with a trainee new to general practice.

Henry did the breaking bad news [role play]. I would never have thought of using that, but I think that’s perfect introduction to general practice. So, before you get dumped with your breaking bad news, you can practice on me, but I would never have thought that. I would have spoken about breaking bad news, you know, what are some questions you can use … So, really, the best way to apply it is by putting him in the chair. So, you do learn by asking other people, watching other people. (Edward/F4/300119)

Having learnt a new teaching procedure, Edward had to wait until the start of the new training year before the time was right to use it, some four months after watching the video-excerpt.

On Friday, I’m doing the breaking bad news using role play. I thought that was a good idea, so I’ll try it. (Edward/F6/270319)

Dialogue enables the development of a shared language that allows participants to articulate and communicate what they know to each other so that they can discuss the professional knowledge of teaching (Loughran Citation2006). For example, the concept of a ‘teachable moment’ became part of the vocabulary of both video-clubs. In the first part of the quotation, Elinor suggests that ‘teachable moments’ are easier to identify via reflection-on-action. In the second half she identifies two potential changes that she could make to her practice, the second contrasting learner- and teacher-centred approaches.

I was just thinking about what Brandon said about the teachable moment and being more mindful of; it’s so easy to look at these [video-excerpts] and go, ‘There it was’. [Laughter. Anne: ‘I’ve spotted it’.] Yeah. Wooh! Um, but, it’s hard, and it’s hard when you’re delivering it in the moment. So, I think, trying to slow down a little bit and just, you know, even just slowing my own thinking, just to stop and go, ‘Right, are they getting it? How can I ask the question that’s going to shape their thinking rather than giving an answer?’ (Elinor/F6/270319)

These outcomes, a heightened self-awareness of the teacher role; the development of shared language to discuss teaching; and an enhanced repertoire of teaching procedures, are attained and refined over time. The ‘breaking bad news’ role play example illustrates how the ongoing nature of the video-club allows cycles of extended reflection about what is taking place in protected teaching and why it is taking place. We offer a further example about the use of anecdotes for enabling learning (Valencia Citation2016). George problematised the use of anecdotes as a pedagogical device in the first online meeting.

I enjoyed people’s thoughts about personal anecdotes or personal experience … and it makes me realise I enjoy doing that in my consulting sessions and I think there’s a purpose to it, but at the end of the day it’s my anecdote and my opinion and my interpretation, and maybe the registrar would value that, but maybe they wouldn’t. There might have been lots of times I’ve given opinions that [they don’t?] think are helpful and so, over time then, maybe that exchange is just satisfying me and my sense of interest and not really providing a good learning moment for the registrar. I don’t know the answer to that, but that is something I would like to get a better feel of over the next number of sessions. (George/O1/311018)

Five months later, George was still reflecting on and uncertain about the use of anecdotes in the final meeting, underscoring the earlier point that change associated with new understandings will be a slow process.

Um. I’d like to develop, I guess the skills at creating and recognising learning situations and whether you can modify and direct the teaching session to produce a learning moment, and so, I use anecdotes a lot like Thomas does, and then, I have the same thoughts that really, that’s of real great value for me; it should be a value for the registrar. Is it? And so, to then do, at times, a discussion with the registrar as to how helpful this approach has been. (George/O6/130319)

Requisite learning climate

Productive critique, discussion, and reflection is a consequence of a psychologically safe learning environment. Inferences drawn from the above quotations coupled with more direct comments from the final evaluation suggest that the facilitator, together with the participants, established and sustained the learning climate necessary to learn through exposing and discussing their practice with others, indicating that the intervention was both suitable for and acceptable to the clinical educators (Orsmond and Cohn Citation2015).

I think it is a unique learning experience and we’re looking at what we actually do, not what we say we do, and it’s, it is so helpful I think to do that, particularly in an environment that is supportive and safe, where we’re all showing ourselves and, in all of our mistakes and flaws and so, but it’s a safe environment and a wonderful environment to learn in. (Charles/O6/130319)

Results summary

Our aim in this section was to provide enough detail to claim that the learning design of the video-club was implemented as intended and show that the activities at the heart of the intervention can combine to influence clinical educators’ teaching practices. The logic model in and the embedded description provide the detail for readers to understand both the learning design, its influences, and how it was enacted. In addition, we have provided an examination of proximal outcomes, an initial examination of distal outcomes, and suggest that the evidence relating to the distal outcomes is promising, warranting a larger study to fully investigate its effectiveness (Institute of Education Sciences & National Science Foundation Citation2013).

Discussion

In the Discussion, we address anticipated difficulties in demonstrating unequivocally that video-clubs improve teaching and learning outcomes in the general practice training context. At a minimum, this requires ‘replicating’ video-clubs in larger numbers at multiple sites (Hill, Beisiegel, and Jacob Citation2013), which Riddell and Moore (Citation2015) call ‘scaling out’. Riddell and Moore also prompt leaders of change to consider ‘scaling up’ and ‘scaling deep’, drawing attention to systemic changes that may be necessary to support an innovation such as the video-club over time. Informal conversations about video-clubs have typically been met with great interest. It is, however, a long way from ‘interest’ to committed action. Readers can judge whether the issues we highlight are germane to their own contexts.

The video-club as a complex intervention

It should be apparent that the video-club is a complex learning design, where a positive impact depends on the cumulative success of multiple factors (Pawson et al. Citation2004). An intervention such as this, which is sensitive to context, cannot be mechanistically replicated (Patton Citation2011). Any video-club will have unique features: the clinical educators, the facilitators, the particular video-excerpts, and so on. Our video-clubs uniquely involved the ‘participant as observer’ researchers. Additionally, as this was a trial, we do not underestimate the importance of the facilitators’ energy, the enthusiasm of the clinical educators, and the close interest of the research team and the resources they provided to design the video-club. Although our study demonstrates the feasibility of implementing video-clubs, these factors may be diminished in a less pioneering context (see Mansell et al. Citation1987, for example).

This complexity makes it hard to identify which elements of the logic model ‘determine’ the outcomes. The research team identified additional factors of uncertain impact, and there will be others of which we are not yet aware. For example, in our study, some of the participants had ‘prior relationships’ with one another. We do not know what impact ‘knowing’ and ‘not knowing’ had on how they engaged with one another or approached the tasks, but we think that ‘prior relationships’ are an additional factor that could either increase or decrease a person’s sense of vulnerability, depending on the related sense of distrust or trust. From a research perspective, scaling out increases the factors that affect success and reduces control over those factors at the same time (Patton Citation2011).

The ‘loose’ aspect of the intervention makes prediction hard. We could not, for example, predict how facilitators would enact their role or how the clinical educators would respond to their actions, which is why we think Mead’s ‘conversation of gestures’ (1934, cited in Stacey Citation2007) is an apt description of the discussion triggered by the video-excerpts and accounts for the video-club’s emergent properties. So, although our logic model is depicted linearly, we suggest that, like most interventions, it does not operate in this way. The same action can have multiple consequences (Hammersley Citation2013). For example, a facilitator’s confrontational challenge may provoke a rebuttal by one participant but may result in another being less likely to offer an opinion.

Designing the requisite research to demonstrate the video-club’s efficacy will be challenging, as the steps leading from what clinical educators have learned in the video-clubs to what they do in workplace teaching which may contribute to trainees’ learning, are anything but straightforward (Cook and West Citation2013; Newton et al. Citation2013). It will require recreating the learning design with high fidelity and having a good understanding of its non-negotiable aspects (Riddell and Moore Citation2015). Yet, highlighting these difficulties does not devalue our findings. The utility of case studies is that they reveal what outcomes are possible and help to provide explanations for observations (Grossman Citation1990).

Scaling-up

Patton (Citation2011) argues that innovative programs cannot grow and thrive in an unchanged system. We think that increasing the number of video-clubs will require strategies that impact on both our institutional context and the wider training system, because of the over-burdened general practice training environment in Australia (Thompson et al. Citation2011). Riddell and Moore (Citation2015) call this ‘scaling up’; a consideration of necessary institutional changes at the level of policy, rules, and laws. We use the related constructs of time and cost to illustrate two important considerations.

In the medical education journals, there is a strong discourse around clinical educators being trained to perform their teacher role to the same standard as professional teachers. Whilst acknowledging that this is difficult (Stoddard and Brownfield Citation2016), it is hard to argue for lower expectations, given that the teaching in clinical settings shapes the practice of health professionals and ultimately impacts on patients’ health outcomes (Delany and Molloy Citation2018). If we promote high standards, then leaders need to ensure that clinical education is truly valued and receives the necessary support and resources that underpins this view (Dotters-Katz Citation2018; Irby, O’Sullivan, and Steinert Citation2015).

Rather than a time-limited program, we prefer to frame the video-clubs as an ongoing process, similar to Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) (Dufour et al. Citation2016). Enabling the same participants to meet each month for an hour would require doubling the teaching-related professional development requirement for our clinical educators, which is currently six hours each year (MCCC GP Training Citation2017). This could be mandated by a change of organisational policy but would also need to be backed up by additional funding from the Federal Government. Even 12 hours of professional development a year is significantly lower than the average of 15.3 days given to professional teachers in Europe (Calleja Citation2018). When one considers that four years is required to furnish graduate teachers with the requisite knowledge, skills, and abilities, it is wishful thinking to believe that comparable expertise can result from the short-term medical education professional development we currently offer. The systemic use of PLCs as the central instrument to produce sustained and substantive improvement in the education system (Dufour and Fullan Citation2013) serves as a useful model for systemic reform in clinical educator professional development.

Although many Australian clinical educators who work in general practice indicate that they are motivated by the satisfaction they get out of teaching, many training posts are private businesses that operate on a fee-for-service arrangement. As well as impacting on the clinician role, teaching in these settings can negatively affect their income, even though it attracts a teaching payment (Laurence et al. Citation2010). Requests to review the teaching incentives paid to training posts are a regular occurrence in Australia (Laurence et al. Citation2014) and are mirrored by calls to reward clinical educators more generally (Irby and O’Sullivan Citation2018). The rate at which we can reimburse clinical educators is dependent on funding from the Federal Government.

Scaling deep

Scaling deep relates to the belief that ‘durable change has been achieved only when people’s hearts and minds, their values and cultural practices, and the quality of relationship they have, are transformed’ (Riddell and Moore Citation2015, 3). This means winning the hearts and minds of the medical educators who currently design and deliver professional development, the clinical educators who partake in it, and the trainees who benefit from the subsequent learning and teaching interactions.

Recruiting 10 clinical educators to take part in the two video-clubs was onerous. In part, we believe this was because video-clubs were unfamiliar and potentially threatening, which may have been exacerbated by being a research project. We should therefore be aware that the participants may be an extreme sample (Miles and Huberman Citation1994) of MCCC’s clinical educators, who possibly valued the concept and shared an interest in the clinical educator role, or they may have been more confident about their educational skills compared to peers. Regardless, clinical educators’ teaching practice, especially protected teaching, is currently a relatively private undertaking. Hattie (Citation2009) claims that this is the case for most teachers; teaching takes place behind closed doors and is seldom questioned. Video-clubs require clinical educators to de-privatise their practice, which renders the participants vulnerable. In our recruitment process, a number of clinical educators stated that they could see the benefits of revealing their educational practice to an audience of peers, but weighed the perceived risk of doing so as greater (Damodaran, Shulruf, and Jones Citation2017). With hindsight, our interest in educational practice had also blinded us to the fact that participants may also have concerns about exposing their clinical practice to others. In contrast to other specialties, general practice is also a relatively private undertaking. The de-privatisation of clinical teaching requires a significant change to current cultural practices. In the parallel context of education, Fullan (Citation2016) argues that a new culture needs to be developed before learning by observing one another’s practice becomes the norm.

Asserting in advance that the learning climate will be ‘safe’ and ‘supportive’, as we did, will not tip the scales for some potential participants, as this quality can only be judged through experience by video-club participants. Nor is ‘safety’ an absolute characteristic, but has to be created and re-created at every meeting and moment to moment. Facilitators have a major role in this regard, and our data suggests they were skilled in helping to generate these conditions; evidenced by participants’ reports of comfort, along with the frequent occasions of ‘intellectual candour’ within the group, which implied repeated preparedness to be vulnerable for the purposes of learning (Molloy and Bearman Citation2019).

One outcome in helping us to scale out the intervention is that we have 10 clinical educators and two facilitators who, on the basis of their experiences, are prepared to promote it. Yet, not all clinical educators are motivated by intrinsic factors related to teaching and learning. There are also extrinsic factors that motivate general practitioners to take on the clinical educator role. For example, in Australia, trainees may reduce the clinical load on other over-burdened doctors (Ingham et al. Citation2014). Convincing clinical educators to join a video-club who are not primarily motivated by a desire to improve their teaching may be a difficult proposition.

Conclusion

We think that our description of the video-clubs supports our claim that we were able to implement the learning design as intended, and the findings provide evidence that its core activities generate the ‘teacher talk’ that we think is necessary to influence clinical educators’ teaching practices. Our initial examination of distal outcomes is promising and justifies a larger study to fully investigate the intervention’s effectiveness.

‘Replicating’ video-clubs in larger numbers is initially necessary to demonstrate their effectiveness, but subsequently we have argued that systemic changes, particularly at the level of policy and ‘culture’, are likely to be required in order to support it as a viable intervention. Scaling deep also requires designers of professional development for health professionals to reflect on the purposes and consequences of their work. A significant motivation for us in developing the video-clubs was a recognition that much of the short-term professional development we offered appeared to have a small impact on teaching practice (Clement et al. Citation2020). The challenge is artfully captured in the title of two papers, Professional Development: A Great Way to Avoid Change (Cole Citation2004) and ‘If We Keep Doing What We’re Doing We’ll Keep Getting What We’re Getting’ (Wilkes, Cassel, and Klau Citation2018).

We are not suggesting that video-clubs are the magic solution to clinical educators’ professional development needs. They do however reflect the inquiry-oriented approach that we think is crucial to clinical teacher education (Zeichner Citation1983), which, if adopted widely, may lead to the design of many novel professional development programs that aspire to have effect sizes that are, in Hattie’s (Citation2009) words, ‘visible to the naked eye’ (8).

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee – Project Identification Number: 2018–169) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the GP-supervisors and video-club facilitators who participated in the research. We would like to thank Professor Jonathan Silverman for his guidance during the project’s implementation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tim Clement

Tim Clement is a Lecturer in Work-integrated Learning in the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences at the University of Melbourne and a Senior Research Fellow with Murray City Country Coast GP Training. Tim completed his PhD in 2004 in the School of Health and Social Welfare at The Open University. He has a particular interest in the work of clinical educators and how to support their role through professional development.

Duncan Howard

Duncan Howard is a General Practitioner and clinical educator. He is the Research Medical Educator Team Lead with Murray City Country Coast GP Training. Duncan was awarded the degree of Master of Medical Anthropology by the University of Melbourne.

Eldon Lyon

Eldon Lyon is a General Practitioner and clinical educator. He is a medical educator with Murray City Country Coast GP training. Eldon has been awarded the degree of Master of Clinical Education by the University of New South Wales. Eldon has held lecturer and tutor positions at Deakin University’s School of Medicine. He was Regional Head of Education for Southern General Practice Training.

Elizabeth Molloy

Elizabeth Molloy is Professor of Work Integrated Learning and Academic Director of Interprofessional Education and Practice in the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences at the University of Melbourne. Liz started her career as a physiotherapist and completed a PhD (2006) on feedback in clinical education at the University of Melbourne. Liz’s work seeks to better prepare students to learn through practice in the clinical workplace. Liz has published more than 115 peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters and books, with a focus on workplace learning, feedback and assessment, interprofessional education and clinical supervisor professional development.

References

- Anderson, N., and M. Henderson. 2004. “e-PD: Blended Models of Sustaining Teacher Professional Development in Digital Literacies.” E-Learning 1 (3): 383–394.

- Australian Government Department of Health. 2018. “Australian General Practice Training – Homepage.” Accessed 3 September. http://www.agpt.com.au/

- Barbour, R. S. 2001. “Checklists for Improving Rigour in Qualitative Research: A Case of the Tail Wagging the Dog?” BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 322 (7294): 1115–1117. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115.

- Beach, R. 2012. “Can Online Learning Communities Foster Professional Development?” Language Arts 89 (4): 256–262.

- Bearman, M., J. Tai, F. Kent, V. Edouard, D. Nestel, and E. Molloy. 2018. “What Should We Teach the Teachers? Identifying the Learning Priorities of Clinical Supervisors.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 23 (1): 29–41. doi:10.1007/s10459-017-9772-3.

- Billett, S., C. Noble, and L. Sweet. 2018. “Pedagogically-rich Activities in Hospital Work: Handovers, Ward Rounds and Team Meetings.” In Learning and Teaching in Clinical Contexts, edited by C. Delany and E. Molloy, 207–220. Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier.

- Bond, M. A., and B. L. Barbara. 2018. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Faculty Inquiry Groups as Communities of Practice for Faculty Professional Development.” Journal of Formative Design in Learning 2 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/s41686-018-0015-7.

- Borko, H. 2004. “Professional Development and Teacher Learning: Mapping the Terrain.” Educational Researcher 33 (8): 3–15. doi:10.3102/0013189x033008003.

- Caird, R., and J. Ogden. 2001. “Understanding the General Practice Tutorial: Towards and Assessment Tool.” Education for General Practice 12 (1): 57–61.

- Caladine, R. 2008. “Learning Activities Model.” In Encyclopedia of Information Technology Curriculum Integration, edited by L. Tomei, 503–510. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Calleja, J. 2018. “Teacher Participation in Continuing Professional Development: Motivating Factors and Programme Effectiveness.” Malta Review of Educational Research 12 (1): 5–29.

- Cantillon, P., and W. de Grave. 2012. “Conceptualising GP Teachers’ Knowledge: A Pedagogical Content Knowledge Perspective.” Education for Primary Care 23 (3): 178–185. doi:10.1080/14739879.2012.11494101.

- Chi, M. T. H. 1997. “Quantifying Qualitative Analyses of Verbal Data: A Practical Guide.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 6 (3): 271–315. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls0603_1.

- Clement, T., D. Howard, E. Lyon, J. Silverman, and E. Molloy. 2020. “Video-triggered Professional Learning for General Practice Trainers: Using the ‘Cauldron of Practice’ to Explore Teaching and Learning.” Education for Primary Care 31 (2): 112–118. doi:10.1080/14739879.2019.1703560.

- Cole, P. 2004. Professional Development: A Great Way to Avoid Change. Melbourne: Incorporated Association of Registered Teachers of Victoria.

- Cook, D. A., and C. P. West. 2013. “Reconsidering the Focus on “Outcomes Research” in Medical Education: A Cautionary Note.” Academic Medicine 88 (2): 162–167. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827c3d78.

- Creswell, J. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, .

- Damodaran, A., B. Shulruf, and P. Jones. 2017. “Trust and Risk: A Model for Medical Education.” Medical Education 51 (9): 892–902. doi:10.1111/medu.13339.

- Delaney, G., S. Jacob, R. Iedema, M. Winters, and M. Barton. 2004. “Comparison of Face-to-face and Videoconferenced Multidisciplinary Clinical Meetings.” Australasian Radiology 48 (4): 487–492. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1673.2004.01349.x.

- Delany, C., and E. Molloy. 2018. “Becoming a Clininal Educator.” In Learning and Teaching in Clinical Contexts: A Practical Guide, edited by C. Delany and E. Molloy, 3–14. Chatswood: Elsevier Australia.

- Dennick, R., and J. Spencer. 2011. “Teaching and Learning in Small Groups.” In Medical Education: Theory and Practice, edited by T. Dornan, K. Mann, A. Scherpbier, and J. Spencer, 131–156. Sydney: Elsevier.

- Dotters-Katz, S. K. 2018. “Medical Education: How are We Doing?” Medical Education 52 (1): 5–7. doi:10.1111/medu.13478.

- Dufour, R., R. Dufour, R. Eaker, T. W. Many, and M. Mattos. 2016. Learning by Doing: A Handbook for Professional Learning Communities at Work. 3rd ed. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

- Dufour, R., and M. Fullan. 2013. Cultures Built to Last: Systemic PLCs at Work. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

- Elo, S., and H. Kyngäs. 2008. “The Qualitative Content Analysis Process.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 62 (1): 107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

- Forsetlund, L., A. Bjørndal, A. Rashidian, G. Jamtvedt, M. A. O’Brien, F. M. Wolf, D. Davis, J. Odgaard‐Jensen, and A. D. Oxman. 2009. “Continuing Education Meetings and Workshops: Effects on Professional Practice and Health Care Outcomes.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2.

- Foundation, K. 2004. Using Logic Models to Bring Together Planning, Evaluation, and Action: Logic Model Development Guide. Battle Creek, MI: W. K. Kellogg Foundation.

- Fullan, M. 2016. The New Meaning of Educational Change. 5th ed. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Gill, D., C. Parker, and J. Richardson. 2005. “Twelve Tips for Teaching Using Videoconferencing.” Medical Teacher 27 (7): 573–577. doi:10.1080/01421590500097026.

- Gold, R. L. 1958. “Roles in Sociological Field Observations.” Social Forces 36 (3): 217–223. doi:10.2307/2573808.

- Grossman, P. L. 1990. The Making of a Teacher: Teacher Knowledge and Teacher Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Hammersley, M. 2013. The Myth of Research-based Policy and Practice. London: Sage Publications .

- Hattie, J. 2009. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-analyses Relating to Achievement. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hawley, W. D., and L. Valli. 1999. “The Essentials of Effective Professional Development.” In Teaching as the Learning Profession: Handbook of Policy and Practice, edited by L. Darling-Hammond and G. Sykes, 127–150. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Heron, J. 1999. The Complete Facilitators’ Handbook. London: Kogan Page.

- Hill, H. C., M. Beisiegel, and R. Jacob. 2013. “Professional Development Research: Consensus, Crossroads, and Challenges.” Educational Researcher 42 (9): 476–487. doi:10.3102/0013189x13512674.

- Hoffmann, T. C., P. P. Glasziou, I. Boutron, R. Milne, R. Perera, D. Moher, D. G. Altman, et al. 2014. “Better Reporting of Interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist and Guide.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 2014;348:g1687. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1687.

- Hsieh, H., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Ingham, G., P. O’Meara, J. Fry, and N. Crothers. 2014. “GP Supervisors – An Investigation into Their Motivations and Teaching Activities.” Australian Family Physician 43 (11): 808–812.

- Institute of Education Sciences & National Science Foundation. 2013. Common Guidelines for Education Research and Development. Washington, DC: Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation.

- Irby, D. M. 2014. “Excellence in Clinical Teaching: Knowledge Transformation and Development Required.” Medical Education 48 (8): 776–784. doi:10.1111/medu.12507.

- Irby, D. M., and P. S. O’Sullivan. 2018. “Developing and Rewarding Teachers as Educators and Scholars: Remarkable Progress and Daunting Challenges.” Medical Education 52 (1): 58–67. doi:10.1111/medu.13379.

- Irby, D. M., P. S. O’Sullivan, and Y. Steinert. 2015. “Is It Time to Recognize Excellence in Faculty Development Programs?” Medical Teacher 37 (8): 705–706. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2015.1044954.

- Kaufman, D. M., and K. V. Mann. 2014. “Teaching and Learning in Medical Education: How Theory Can Inform Practice.” In Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice, edited by T. Swanwick, 7–29. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- King, N. 1998. “Template Analysis.” In Qualitative Methods and Analysis in Organizational Research: A Practical Guide, edited by G. Symon and C. Cassell, 118–134. London: Sage Publications .

- Korthagen, F., and A. Vasalos. 2005. “Levels in Reflection: Core Reflection as a Means to Enhance Professional Growth.” Teachers and Teaching 11 (1): 47–71. doi:10.1080/1354060042000337093.

- Lantz-Andersson, A., M. Lundin, and N. Selwyn. 2018. “Twenty Years of Online Teacher Communities: A Systematic Review of Formally-organized and Informally-developed Professional Learning Groups.” Teaching and Teacher Education 75: 302–315. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.07.008.

- Laurence, C. O., L. E. Black, J. Karnon, and N. E. Briggs. 2010. “To Teach or Not to Teach? A Cost-benefit Analysis of Teaching in Private General Practice.” Medical Journal of Australia 193 (10): 608–613. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb04072.x.

- Laurence, C. O., M. Coombs, J. Bell, and L. Black. 2014. “Financial Costs for Teaching in Rural and Urban Australian General Practices: Is There a Difference?” Australian Journal of Rural Health 22 (2): 68–74. doi:10.1111/ajr.12085.

- Le Cornu, R., and R. Ewing. 2008. “Reconceptualising Professional Experiences in Pre-service Teacher Education … Reconstructing the Past to Embrace the Future.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24 (7): 1799–1812. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.02.008.

- Lord, B. 1994. “Teachers’ Professional Development: Critical Colleagueship and the Role of Professional Communities.” In The Future of Education: Perspectives on National Standards in America, edited by N. K. Cobb, 175–204. NewYork, NY: College Entrance Examination Board.

- Loughran, J. 2006. Developing a Pedagogy of Teacher Education: Understanding Teaching and Learning about Teaching. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Maher, B., R. O’Neill, A. Faruqui, C. Bergin, M. Horgan, D. Bennett, and C. M. P. O’Tuathaigh. 2018. “Survey of Irish General Practitioners’ Preferences for Continuing Professional Development.” Education for Primary Care 29 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1080/14739879.2017.1338536.

- Mansell, J., D. Felce, J. Jenkins, U. de Kock, and S. Toogood. 1987. Developing Staffed Housing for People with Mental Handicaps. Tunbridge Wells: Costello.

- Mauthner, N., and A. Doucet. 1998. “Reflections on a Voice-centred Relational Method.” In Feminist Dilemmas in Qualitative Research, edited by J. Ribbens and R. Edwards, 119–146. London: Sage Publications.

- Maxwell, J. A. 2012. A Realist Approach for Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- MCCC GP Training. 2017. ED0025 Supervisor Professional Development. Warrnambool: Murray City Country Coast GP Training.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Molloy, E. 2009. “Time to Pause: Giving and Receiving Feedback in Clinical Education.” In Clinical Education in the Health Professions, edited by C. Delany and E. Molloy, 128–146. Australia: Churchill Livingstone.

- Molloy, E., and M. Bearman. 2019. “Embracing the Tension between Vulnerability and Credibility: ‘Intellectual Candour’ in Health Professions Education.” Medical Education 53 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1111/medu.13649.

- Morgan, D. L. 1993. “Qualitative Content Analysis: A Guide to Paths Not Taken.” Qualitative Health Research 3 (1): 112–121. doi:10.1177/104973239300300107.

- Newton, X. A., R. C. Poon, N. L. Nunes, and E. M. Stone. 2013. “Research on Teacher Education Programs: Logic Model Approach.” Evaluation and Program Planning 36 (1): 88–96. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.08.001.

- Olanrewaju, O. S., and J. Thistlethwaite. 2013. “A Systematic Review of Faculty Development Activities in Family Medicine.” Medical Teacher 35 (7): e1309–e1318. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.770132.

- Orsmond, G. I., and E. S. Cohn. 2015. “The Distinctive Features of a Feasibility Study: Objectives and Guiding Questions.” OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health 35 (3): 169–177. doi:10.1177/1539449215578649.