ABSTRACT

The relationship between gender, working conditions, occupational gender composition and wages is investigated to test the support for the mother-friendly job hypothesis in the family-friendly welfare state of Sweden. The Swedish level-of-living survey (LNU2010) is used to measure two dimensions of working conditions: flexibility and time-consuming work. The findings do not support the notion that women’s work is more family-friendly as neither women in general nor mothers have more flexibility than men. Furthermore, femaledominated occupations have, in comparison with other occupations, less flexible work arrangements. Instead, gender-integrated occupations have the most flexible work arrangement. Time-consuming work is also most common in gender integrated occupations. Flexibility and timeconsuming work largely go hand in hand and are both positively associated with wages and also more common in the service class. Finally, women are not economically compensated for their job characteristics in the same extent as men, especially not for their time-consuming work which partially account for the gender wage gap. Taken together the findings counters the notion that the remaining gender wage gap largely is due to women avoiding time consuming work or choosing flexibility. Instead it seems like women are compensated less regardless of their job characteristics.

RÉSUMÉ

La relation entre genre, conditions de travail, composition professionnelle par genre et salaires est explorée. La dernière vague de l'Étude suédoise sur les conditions de vie (LNU2010) est utilisée afin de mesurer deux dimensions se référant aux conditions de travail, la flexibilité et le travail chronophage. Les résultats ne corroborent pas l'hypothèse selon laquelle le travail des femmes serait plus compatible avec la famille, dans la mesure où ni les femmes en général, ni les mères n'ont plus de flexibilité dans leur travail que les hommes. De plus, les professions à prédominance féminine ont, en comparaison avec d'autres professions, des conditions de travail moins flexibles. En revanche, les professions à prédominance mixte présentent les conditions de travail les plus flexibles. Flexibilité et travail dit chronophage vont en grande partie de pair et sont tous deux associés positivement aux salaires, et sont aussi plus répandus dans les services. Enfin, les femmes ne sont pas rémunérées pour les caractéristiques de leur travail au même niveau que les hommes, et c'est plus précisément le cas lorsque qu'elles ont un travail dit chronophage, ce qui explique partiellement les écarts de salaires entre hommes et femmes.

Introduction

Gender differences in working conditions are often singled out as at least a partial explanation for women’s lower wages. It is often assumed that women choose flexibility and the possibility to combine work life and family life instead of pay (e.g. Filer, Citation1985; McCrate, Citation2005). Some argue that the tendency among women to choose so-called mother-friendly jobs is one of the most central explanations to the remaining gender wage gap (see Goldin, Citation2014). The idea of mother-friendly jobs is connected to the ‘idea of compensating wage differentials’ (dating back to Adam Smith; see, e.g. Smith Citation1979). This theory holds that jobs with unfavorable conditions (e.g. dangerous or physically strenuous work) are associated with higher compensations (pecuniary rewards) than are jobs with more-favorable working conditions to attract sufficient labor supply (e.g. Jacobs & Steinberg, Citation1990; Killingsworth & Heckman, Citation1987). In this view, female-dominated occupations are assumed to have more-favorable working conditions than male-dominated occupations have (e.g. Filer, Citation1985). Although there is empirical support for the premise that unfavorable working conditions tend to be associated with a wage increase (see, e.g. Daw & Halliday Hardie, Citation2012 for an overview), compensating wage differentials do not appear to account for the wage gap between women’s and men’s work (see, e.g. Glass & Camarigg, Citation1992; le Grand, Citation1997; McCrate, Citation2005). The idea of mother-friendly jobs also rests on a compensating principle; female-dominated occupations are assumed to have flexible working arrangements that on the one hand facilitate combining family and work, but on the other hand, result in lower wages. The empirical findings concerning mother-friendly jobs are mixed. Although some studies show that the proportion of women in an occupation is positively correlated with flexible work arrangements (e.g. Davis & Kalleberg, Citation2006; Lowen & Sicilian, Citation2009), other studies fail to find support for the idea that women’s jobs are more flexible (e.g. Glass & Camarigg, Citation1992; Glauber, Citation2012, Citation2011; Grönlund & Öun, Citation2018; le Grand, Citation1997) or find that female-dominated occupations have less flexible work arrangements than other occupations (e.g. Chung, Citation2019a).

Although a job can be family friendly, it can also be ‘family-unfriendly’. In other words, work arrangements can be difficult to reconcile with family duties. For instance, prior research indicates that employees in high-skilled or high-prestige occupations have time-consuming work arrangements, such as demands for constant availability, significant overtime work and business travel. Such working conditions are often difficult to combine with an actual, or with an employer-assumed, responsibility for the family (Magnusson, Citation2010; cf. Goldin, Citation2014; Nsiah, DeBeaumont, & Ryerson, Citation2013; Williams, Citation2000, Citation2010). Overall, time-consuming work characteristics are difficult to combine with family life but tend to be associated with high wages. Gender differences in these work arrangements are thus important for the understanding of the gender wage gap, in particular, the gender wage gap in high-prestige occupations (Magnusson & Nermo, Citation2017). For instance, Goldin (Citation2014) asserts that a large part of the remaining gender wage gap is due to firms rewarding individuals who work long hours and who are available most of the time.Footnote1 Likewise, Cha and Weeden (Citation2014) show that today’s gender wage gap, in the US, is linked to an increasing economic return to overtime work. As men, on average, work overtime to a larger extent then women this has risen men’s wages compared to women’s.

Naturally, both flexibility and time-consuming work are closely linked to the type of occupation and social class. According to the class scheme based on Erikson-Goldthorpe-Portocarero (EGP), which distinguishes between employees with service contracts and employees with labor contracts, the service class on average has a large amount of authority, whereas the worker-class is more supervised (see Erikson & Goldthorpe, Citation1992; Erikson, Goldthorpe, & Portocarero, Citation1979). It is plausible to assume that occupations including much authority are also more flexible (see Schieman, Schafer, & McIvor, Citation2013). According to the high-performance work organizations view is flexibility offered to employees to increase commitment and performance. Thus, employees control and flexibility over own work is a strategy to increase productivity (Davis & Kalleberg, Citation2006; Ortega, Citation2009). Prior research also shows that high-skilled workers have greater access to flexibility (Glass & Noonan, Citation2016; Golden, Citation2009; Riva, Lucchini, den Dulk, & Ollier-Malaterre, Citation2018; Schieman et al., Citation2013; Swanberg, Pitt-Catsouphes, & Drescher-Burke, Citation2005). However, according to the mother-friendly job hypothesis, women, particularly mothers, are assumed to choose or be allocated to more mother-friendly job tasks also within social classes and categories of occupational gender compositions. How working conditions are distributed between men and women both in general but also within classes and across occupational gender composition in Sweden are to my knowledge unknown. The present paper attempts to fill this void.

To summarize, the aim of the paper is to explore the association between working conditions, occupational gender composition, social class, and the gender wage gap. By using the latest wave of the Swedish-level-of-living survey (LNU2010), I focus both on well-known indicators of working conditions such as flexible work arrangements and on more ‘novel’ but crucial indicators, drawing from the concepts used by Goldin (Citation2014), such as demand for constant availability and the ability to postpone when to perform a job task. Even when flexibility eases the combination of work life and family life whereas time-consuming work aggravates it, it is likely that flexibility and time-consuming work go hand in hand, that is, if you get flexibility you also get time-consuming work. Employees who have control over when and where they work are also expected to work long hours and to be high performance (Gallie et al., Citation2012). Accordingly, it is likely that workers have flexible arrangements simultaneously with high demands to devote much time to their work. Furthermore, the combination of time-consuming work but no flexibility could be considered the most difficult to combine with duties outside work. Thus, the approach of investigating both, and also separating between, family friendly (flexible) and family unfriendly (time-consuming) working conditions concurrently, and considering the interaction between them, suggests important implications for the field.

Working conditions under study

Flexible working conditions have no clear definition. In previous research, they have been measured in several ways (Hill, Grzywacz, Allen, & Blanchard, Citation2008). Glauber (Citation2011), for instance, uses a measure of flexible scheduling, whereas Glass and Camarigg (Citation1992) measure flexibility by the ability to take breaks, take time off to take care of family matters and the ability to change job days and job hours. A common theme for many studies is to relate flexibility to time on and time off the job, that is, flexibility in when to start, stop and perform a job task (e.g. Chung Citation2019a; Grestel & Clawson, Citation2014; Kelly & Moen, Citation2007). This type of schedule control has put forward as being of major importance for the possibility to combine work and family life (Kossek, Lautsch, & Eaton, Citation2006). The measure used in the present paper captures traditional aspects such as having flexible working time (when to start and stop work) as well as the ability to postpone (or reschedule) when to perform a job task which could be seen as a measurement of working-time autonomy (see Lott & Chung, Citation2016). Having working-time autonomy and thus the ability to control when to work is, probably, the most important flexible working condition of all because it eases the work-family conflict the most (see e.g. Chung, Citation2019a; Kossek et al., Citation2006). Having the possibility to reschedule work facilitates taking care of sick children, taking time off to visit a child welfare center (BVC) and, for example, participation in parent-teacher meetings without the job being affected. Thus, it is possible to recapture working time or to perform job duties whenever doing so suits the employee. Moreover, family friendly working arrangements in Sweden are offered to all parents by the state (e.g. Grönlund & Öun, Citation2018). The right to parental leave and the right to reduce work hours when having children are for example provided by the state and not by the employer. The measurement of flexibility used here is therefore aimed to distinguish those who have extensive flexible work arrangements over and above the family friendly arrangements that are offered to all parents.

Flexibility often serves as a family friendly arrangement but can also be used to increase performance – performance-oriented flexibility. In particular, working-time autonomy is related to both performance and commitment. That is, employees get control over their work to raise their productivity (e.g. Ortega, Citation2009). For instance, prior research has shown working-time autonomy to be related with increased unpaid overtime work (e.g. Chung & van der Horst, Citation2018). Accordingly, have working-time autonomy also parallels with how time-consuming work is used in present paper.

Time-consuming working conditions are related to time, but here, time is a resource the employee is expected to give to the employer. Work characteristics such as constant availability, overtime work, taking part in meetings outside regular working time and travel on short notice can all be expected to take a great deal of time from the employee and be difficult to combine with duties outside work (Magnusson, Citation2010). The possibilities of being available most of the time and of working long hours could both be a means of signaling work commitment by the employee and/or a demand from the employer (Blair-Loy, Citation2003; Cha & Weeden, Citation2014). ‘The long hours culture’, that is, the ability to work significant overtime, is a key desideratum in filling managerial and prestigious positions. The norm of the long hour culture is embedded in workplace organizations and in beliefs of what is an ideal worker (Acker, Citation1990; Cha & Weeden, Citation2014; Williams, Citation2000). The norm of long hours of work is more common in professional and managerial occupations, and the importance of long hours of work has been increasing overtime (Cha & Weeden, Citation2014). Rutherford (Citation2001) asserted that ‘the time resource’ has become a factor that distinguishes men from women in promotion processes because time is more available to men because of their lesser family responsibilities. Demands of time-consuming work are difficult to meet when having obligations outside paid work (cf. Goldin, Citation2014). Because women still, in general, perform a larger share of unpaid work, such working conditions could be considered difficult to reconcile with motherhood. Time-consuming working conditions could accordingly be labeled ‘family-unfriendly’.

Working conditions and occupational gender composition

The relationship between flexible working conditions and occupational gender composition is not clear-cut. According to the hypothesis of mother-friendly jobs, access to flexibility should be greatest in female-dominated occupations; women need flexible arrangements to combine work life with family life. Women (or mothers) will hence choose to work in female-dominated occupations to facilitate everyday family life (Becker, Citation1991; Filer, Citation1985).

From another point of view, access to job flexibility should be greatest in gender-integrated occupations because these occupations have been categorized as ‘clustered in “good” segments of the labor market’ (Glauber, Citation2011; p. 473 cf. Cotter, Hermsen, & Vanneman, Citation2003). These occupations consist largely of a highly skilled labor force (Magnusson, Citation2009), and prior research has found high-skilled workers (e.g. Chung, Citation2019b; Golden, Citation2009; Riva et al., Citation2018) and privileged workers (e.g. Swanberg et al., Citation2005) have more access to flexibility compared with other groups. Theoretically, job flexibility is linked to social class, because the service class has more authority over their work and thus also more flexibility (cf. Erikson & Goldthorpe, Citation1992). Chung (Citation2019b), for example, shows that skill level of occupations is one of the most important factors for explaining different access to flexible work arrangements. The theory of a dual labor market distinguish between insiders and outsiders in the labor force, where insiders are fully integrated with the labor market and have favorable working conditions and the latter ones consist of a more vulnerable group with poor working conditions and high turnover (Schwander & Häusermann, Citation2013). More women than men tend to be outsiders which, according to the perspective of dual labor market, gives them less access to flexible work arrangements. Präg and Mills (Citation2014), for instance, find women and young workers to have less access to flexible work arrangements across 29 European countries.

Regarding the relationship between occupational gender composition and flexibility, empirical studies find a positive correlation between the proportion of women in the occupation and flexibility (Davis & Kalleberg, Citation2006; Lowen & Sicilian, Citation2009). Other studies, however, find no (e.g. Glass & Fujimoto, Citation1995) or a negative association (e.g. Glass & Camarigg, Citation1992). Most previous studies have modeled the relationship as linear, but a few exceptions indicate that it can be non-linear (Chung, Citation2019a; Deitch & Huffman, Citation2001; Glauber, Citation2011). For instance, Glauber (Citation2011) finds that workers in the US have greater access to flexibility in gender-integrated occupations. Likewise, Chung (Citation2019a) show in a cross-country study, based on 27 European countries, that workers in gender-integrated occupations have larger access to flexible schedule compared with both male- respective female-dominated occupations. Furthermore, that workers in female-dominated occupations have the least access to flexible schedules across all countries. One study based on Swedish data from 1991 indicates that female-dominated occupations have low flexibility (le Grand, Citation1997).

To summarize, both theories and the empirical findings provide conflicting views concerning the association between occupational gender composition and flexible work arrangement.

Concerning the relationship between occupational gender composition and time-consuming work, prior research is lacking. According to the mother-friendly hypothesis, access to time-consuming working conditions should be lower in female-dominated occupations because these conditions are difficult to reconcile with family duties. Because time-consuming work is more common among high-prestige occupations, the amount of time-consuming work most likely is greater in gender-integrated occupations because such occupations, in general, are highly skilled occupations (Magnusson, Citation2009).

The present study adds to the scarce Swedish evidence by using updated indicators on flexibility, investigating both flexibility and time-consuming work simultaneously and by modeling the association between working conditions and share of women in the occupations as non-linear.

Gender differences in the distribution of working conditions and the gender wage gap

The distribution of flexible work arrangements and time-consuming work between men and women could vary regardless of occupational gender composition and social classes. Thus, irrespective of occupation women could (according to the mother-friendly job hypothesis) choose more job flexibility and avoid, or be assigned, less time-consuming work overpay, which in the end results in an overall wage gap between men and women (cf. Goldin, Citation2014). Goldin (Citation2014) talks about the importance of ‘being around’ and be at the workplace during work hours. Goldin (Citation2014) asserts that employees that leave early and, for example, instead work at home or during evenings and therefore not is around during standard hours miss out in terms of wages even if they work as much as those employees that are ‘around’. Flexibility and the possibility to work at home or have control over where and when to work is in this perspective negative for earnings in occupations where attendance during ‘right hours’ is important. So, for this point of view, in line with Goldin (Citation2014) reasoning, seems time-consuming work (being available and/or being ‘around’) to be positive for wages. On the other hand, making use of flexible arrangements could instead be seen, from the employer, as a sign of lower commitment (Glass, Citation2004; Goldin, Citation2014; Williams, Blair-Loy, & Berdahl, Citation2013) and thereby be negatively related with wages.

However, in contrast to the hypothesis of mother-friendly jobs, prior studies indicate that men have more access to job flexibility than women do (McCrate, Citation2005; Präg & Mills, Citation2014; Weeden, Citation2005). Furthermore, quite a few studies show that high earners and managers have more access to job flexibility (e.g. Riva et al., Citation2018; Swanberg et al., Citation2005; Golden, Citation2009). For example, Williams et al. (Citation2013) emphasize that men’s greater access to job flexibility is due to men, in general, belonging in high-status jobs. Moreover, and maybe most important for wage differentials between men and women, some studies indicate a positive relationship between flexible work arrangements and wages (e.g. Glass & Noonan, Citation2016; Langer, Citation2018; Lott & Chung, Citation2016).

Both flexibility and time-consuming work have parallels with social class, in which the working class, in general, is more supervised and is therefore expected to have a lower degree of flexibility, whereas workers in the service class have more flexibility but are simultaneously expected to devote more time in their work (e.g. Gallie et al., Citation2012). Offering employees control over their own work could be seen as a way to increase both commitment and performance (Chung & van der Horst, Citation2018; Davis & Kalleberg, Citation2006). Both high flexibility and time-consuming work are, accordingly, related with high wages. From this point of view women could have lower wages than men because they have less access to flexibility and time-consuming work even when working in occupations with high skill requirements (e.g. Golden, Citation2009; Swanberg et al., Citation2005). Prior research indicates a gender difference in time-consuming work to women’s disadvantage, which partially accounts for the gender wage gap, particularly in high-prestige occupations (Cha & Weeden, Citation2014; Goldin, Citation2014; Magnusson, Citation2010; Magnusson & Nermo, Citation2017). Likewise, Williams et al. (Citation2013) show that US women in the service classes have less control and flexibility compared with men in the same class. Similarly, Grönlund and Öun (Citation2018) found, based on sample of newly graduated men and women in five high-skilled occupations in Sweden that women have less family friendly conditions compared to men. Moreover, rewards associated with flexibility and time-consuming work could vary between genders, where women’s pay off to such working conditions is lower (Schieman et al., Citation2013) which in the end results in wage differentials between men and women. Lott and Chung (Citation2016), for instance, display that schedule control is associated with a gain in wage but the gain is larger for men than women.

The use of flexibility could also be gendered, where women to a larger extent use flexibility to meet family demands while men, to a larger extent use schedule control to increase performance (Chung & Van der Lippe, Citation2018; Kim, Citation2018; Kurowska, Citation2018) which in the end lead to gender wage differentials to women’s disadvantages (e.g. Lott & Chung, Citation2016).

Thus, the importance of working conditions for the gender wage gap is not clear-cut. According to the mother-friendly hypothesis, part of the gender wage gap could be due to women having more job flexibility. Conversely, part of the gender wage gap could, according to the perspective of high-performance work organizations and to earlier empirical findings reported above, be due to women’s lower access to job flexibility and time-consuming work because both of these work arrangements empirically appear to be associated with high wages (e.g. Golden, Citation2009; Swanberg et al., Citation2005).

Swedish case

The association between working conditions, gender and wages is especially interesting to analyze in the Swedish context because Sweden has active policies to help men and women to combine work and family (a dual-earner family policy model) (Korpi, Ferrarini, & Englund, Citation2013). The family policies provide men and women with generously compensated parental leave arrangements, access to public childcare and possibilities to reduce their working time when their children are young (Korpi, Citation2000; Thévenon, Citation2011). The Swedish labor market is characterized by a high employment rate among women, particularly among mothers, and by a large public sector in which women are over-represented. Based on these policies, it is plausible to assert that to some extent, all Swedish employees have a legal right to ‘family-friendly’ working conditions (Grönlund & Öun, Citation2018). Thus, the state provide, and not the employer, all parents with the possibility to reduce work hour to take care of children, stay at home and take care of sick children and to take parental leave. According to the crowding out theory countries with generous family policies on national level ‘crowd out’ informal caring relations as well as family friendly arrangements on occupational and organization level (e.g. van Oorschot & Arts, Citation2005). From another perspective generous policies on the national level will increase family friendly arrangements also at the company level (e.g. Davis & Kalleberg, Citation2006). The empirical support is mixed where some indicate that workers in countries with family friendly policies have larger access to schedule control (Chung, Citation2019b; Lyness, Gornick, Stone, & Grotto, Citation2012) while others did to find support for such associations (Kassinis & Stavrou, Citation2013). Moreover, there are empirical evidence that flexible schedules are more common for employees in public sector and in large companies (Den Dulk, Groenevelda, Ollier-Malaterreb, & Valcour, Citation2013).

Recently, scholars – (notably Mandel (Citation2012); Mandel & Semyonov, Citation2005) – have argued that Scandinavian family policies do not only lead to greater gender equality in the sense that most women are economically active but also have certain non-egalitarian consequences. They claim that these policies increase the gendered nature of the labor market, in which women are trapped in female-dominated occupations, mostly in the public sector, with family friendly working conditions – yet with lower wages (Mandel & Semyonov, Citation2005). According to the critic raised by Mandel and Semyonov (Citation2005) flexible working arrangements should be more common in the public sector and in female-dominated occupations compared with other occupations and be associated with lower wages.

Summary and expectations

Both prior empirical research and the theoretical arguments reveal contradictory findings that lead to conflicting expectations.

According to the theory of mother-friendly jobs and compensating wage differentials, female-dominated occupations, the public sector and women, particularly mothers, are supposed to have flexible working conditions. The theory also indicates flexibility should be negatively associated with wages.

In contrast, job flexibility empirically has been shown to be greatest among highly skilled and highly paid workers and among men. From that point of view, flexible working conditions could be expected to be more common among men, in the upper service class and in gender-integrated occupations and to have a positive association with wages.

Because time-consuming work theoretically is supposed to be hard to combine with family responsibilities together with the fact that earlier studies indicated that time-consuming working conditions were more common in highly skilled occupations are time-consuming working conditions expected to more common among men, in the upper service class and in gender-integrated occupations and to be positively associated with wages.

Expectations concerning working conditions and the gender wage gap also point in different directions depending upon whether flexibility is related positively or negatively to wages. According to the mother-friendly hypothesis, women’s lower wages are expected to be partially explained by women having more job flexibility and less time-consuming work. If flexibility, instead, is positively related to wages, women’s lower wages are expected to be partially explained by women having less job flexibility or by a gender difference, to women’s disadvantages, in wage gain related to flexible work arrangements.

To increase our understanding of these rather complicated relationships, I first investigate how working conditions in Sweden are associated with occupational gender composition, social class and gender. Furthermore, I investigate whether there are gender differences in the distribution of working conditions within classes and within occupational gender composition.

Second, the relationship between working conditions and the gender wage gap is investigated. Because flexible and time-consuming work could be linked to each other, possible interactions between flexible and time-consuming work are analyzed.

Data and method

The present study uses individual-level data from the sixth and most recent wave of the Swedish-Level-of-Living Survey conducted in 2010 (LNU-2010), which is a national representative survey of 0.1% of the Swedish population between the ages of 18 and 75. The study sample consists of 2285 employees (age 19 to 65) that were in a paid occupation and worked at least ten hours per week at the time of the interview.

I initially estimate how working conditions are associated with occupational gender composition, social class and gender using linear probability models (LPM).Footnote2 In the following step, the relationships between gender, working conditions and wages are estimated with OLS-regressions.

Variables

Dependent variables

Flexible working conditions is a dummy variable based on a combination of three items measuring flexible working conditions; ‘Do you have any kind of flexible working hours, i.e. can you within certain limits decide yourself when you want to begin and end work’ (response categories yes/no), ‘If you need to go on a private errand, can you leave your workplace for about half an hour without informing a supervisor’ (response categories yes/no) and the item ‘Can you make a decision to move your own working hours up to an hour, several hours or one to several days?’(response categories: No, Up to an hour, Up to a few hours, Several hours, One to several days). Employees who have no fixed times, who offer the ability to perform errands during working hours and who also offer the ability to postpone a job task at least several hours are here defined as having flexible working conditions. Thus, employees are coded 1 in the dummy variable flexible working conditions if they have no fixed (no = 1) times and have the ability to perform errands during working hours (yes = 1) and have the ability to postpone a job task several hours (Several hours and one to several days = 1).Footnote3

Time-consuming work is a dummy variable based on a combination of three items measuring time-consuming work; ‘How often do you work overtime?’ (By and large never, A few times a year, A couple times a month, A couple of times a week, Several times a week), ‘Do you ever stay overnight away from home because of your work, e.g. on a business trip? About how many nights are you away altogether during one year’s time?’, ‘Are you entitled to financial compensation for the overtime you work?’ (yes/no). Employees who frequently work overtime (overtime once or more a week = 1), have at least one overnight stay yearly and who are expected to work overtime without extra compensation (no = 1) are here defined as having time-consuming work. Thus, employees are coded 1 in the dummy variable time-consuming work if they work overtime once or more a week and also have at least one overnight stay yearly and not are compensated for their overtime. Working overtime, having overnights stays and working unpaid overtime are commonly time-consuming, and they can thus be difficult to combine with responsibilities outside work (Magnusson, Citation2010). Unpaid overtime indicates whether the employee is expected to work overtime without extra compensation. If the employee is not economically compensated for overtime, the hourly wages are normally set higher because the compensation is already included in the normal salary. Unpaid overtime is here used as indication of demand for constant availability. That is, the employee is expected to work overtime if needed to meet the requirements that the position demanding, even if this implies working on evenings or weekends. Working unpaid overtime could also be seen as an indication of worker commitment and performance (cf. Davis & Kalleberg, Citation2006). Thus, it could be seen as a signal of being an ‘ideal worker’ which is connected with time-consuming work (Acker, Citation1990). The measurement used here of time-consuming work has parallels with performance-oriented flexibility (see Chung & van der Horst, Citation2018).

As it is possible that workers have flexibility simultaneously with high demands to devote much time to their work some of the analysis include a measure of the combination of flexibility and time-consuming work. This is measured with four dummy variables: No flexibility and no time-consuming work (respondents who according to the variables presented above have no flexibility and no time-consuming work is coded 1), Time-consuming work with no flexibility (respondents who have time-consuming work but no flexibility is coded1), Flexibility but no time-consuming work (respondents who flexibility work but no time-consuming work is coded1), and Flexibility with time-consuming work (respondents who have both flexible and time-consuming work is coded 1).

In the second step of the analysis, the dependent variable is the logarithm of hourly wage. When using a logarithmic dependent variable in an OLS-regression, a change by one unit in the independent variable produces a percentage change in the dependent variable (Allison, Citation1999). The following estimation is used to calculate percent change: 100(exp(b-1)). In cases in which data on hourly wages are missing, other types of pay (e.g. daily, weekly or monthly) have been converted into hourly wages. The wage variable also includes bonuses, price-rate payments, other earnings benefits and compensation for overtime.

Independent variables

Occupational gender composition is measured by percentage of women in each occupation. Occupations are classified (at the three-digit level) according to the Swedish Standard Classification of Occupations (SSYK), which is based on the International Standard of Classification of Occupations (ISCO-88). To capture a non-linear association between occupational composition and flexibility, the variable percentage female is used as a categorical variable divided into five groups: 0–20, 21–40, 41–60, 61–80 and 81–100 percent women in the occupation. Thus, this division yields one male-dominated category, one female-dominated, one gender-integrated category and two somewhat gender-integrated occupations but which have an overrepresentation of either men or women.

Social class is here coded according to socioeconomic classification (SEI), developed by Statistics Sweden, which bear a close resemblance to the international EGP class schema (Erikson-Goldthorpe-Portocarero). Four categories are used: unskilled/skilled manual workers, assistant non-manual employees, intermediate non-manual employees and higher non-manual employees.

Number of children living in the respondent’s household is measured with three variables, one child in household, two children in the household, three of more children in the household. I also control for having young children (under 6 years of age) in the household (1 = having young children in the household). Public sector indicates whether the employee works in the public or private sector (Public = 1). A control for working part-time is included (1 = work part-time fewer than 35 h per week).

To control for individual human capital and occupational skill level, the analysis also includes years of total Education (continuous variable ranging between 5 years to 33 years of education), years of total Work experience (continuous variable ranging between 0 and 48 years in paid work) (squared work experience is used in the wage regressions) and Initial trainingFootnote4, which refers to the duration of introduction time that is normally necessary for learning to perform the job tasks. Educational requirementsFootnote5 are a continuous variable measuring the number of years of post-compulsory schooling normally demanded in their present job (ranging between 0 and 20 years). Supervisory position is a continuous variable and indicates number of subordinates (lowest value 0 subordinates, highest value 1300 subordinates).

Results

Below, we find how working conditions are distributed by gender, occupational gender composition and social class.

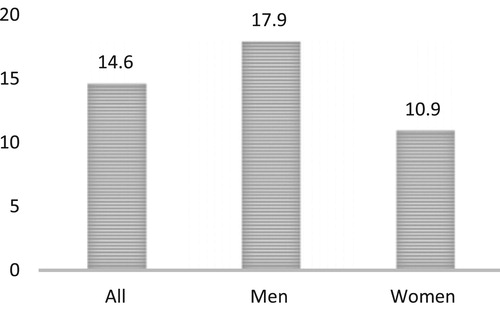

shows the distribution of flexible working conditions by gender. About 15 percent of all employees report flexible working conditions, meaning that these 15 percent have the ability to perform errands during working hours, have the ability to postpone a job task at least several hours and have no fixed times. Overall, the gender differences are relatively small, but the disparities that are shown indicate that women’s working conditions, in general, are less flexible. Among women 11 percent states that their working conditions are flexible, compared to18 percent among men. Accordingly, appear, men’s job characteristics to be easier to combine with responsibilities outside work life.

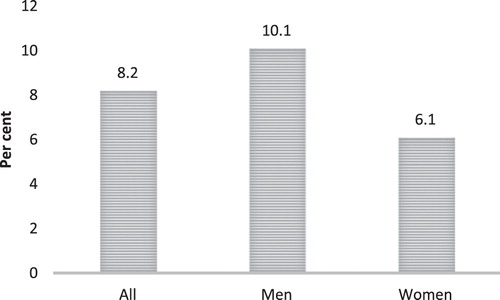

shows the gender distribution in time-consuming working conditions. Only about 8 percent among all employees have time-consuming working conditions, that is, they do frequently work overtime, have at least one overnight stay yearly and they work unpaid overtime. Men are over-represented within this group and have in general more time-consuming working conditions than women.

The next step displays how flexibility and time-consuming work are related to each other using the variable measuring the combination of working conditions. shows that most men and women have neither time-consuming work nor flexible work. Among women, 85.5 percent indicate that they have no flexibility and no time-consuming jobs compared with 77 percent of men. The category containing both flexible work and time-consuming work is the smallest one, only 5.1 percent among men and 2.6 percent among women have this combination. Almost 13 percent of men state that their working conditions are flexible but not time-consuming compared with approximately 8 percent among women. More men than women state that their working conditions are time-consuming but not flexible – a combination that can be assumed to be the hardest one to combine with family duties.

Table 1. Combination of flexibility and time-consuming work.

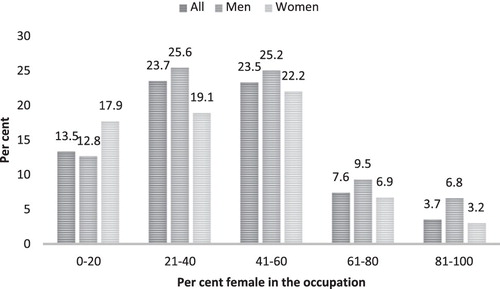

shows the distribution of flexible work according to occupational gender composition. Gender-integrated occupations (21–40 and 41–60 percent female) tend to be most flexible. Among these employees men tend to have more flexible working conditions than women, especially in occupations with 21–40 percent female. Men have in general more flexible working conditions regardless of gender composition, except from male-dominated occupations. In these occupations women have tend to have more flexible conditions compared with men. Both employees in female-dominated occupations and employees in the male-dominated occupations report low flexible work arrangements. The descriptive statistics indicate that female-dominated occupations have the lowest degree of flexible working conditions.

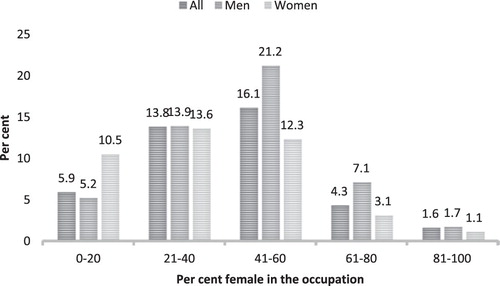

reports that employees in gender-integrated occupations have the greatest amount of time-consuming working conditions overall. In particular have men in gender-integrated occupations time-consuming work. According to the descriptive statistics, these occupations are most flexible but at the same time claim a great deal of time. Time-consuming work is also rather common in occupations with 21–40 percent female, but less common in male and female-dominated work in particular. Time-consuming work tends, however, to be more common among women in male-dominated work.

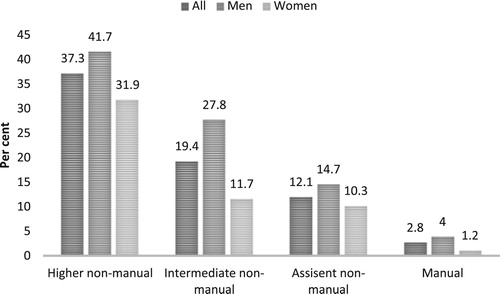

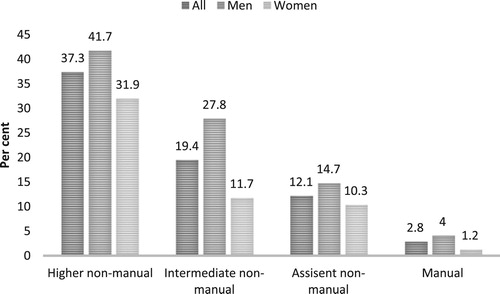

and display how working conditions are related to social class. As expected, flexibility is more common in the high non-manual class, whereas few manual employees (less than 5 percent) indicate that they have flexible working conditions. Men tend to have more flexibility than women within all social classes.

shows that higher non-manual employees also have a large amount of time-consuming conditions. Also here men have more time-consuming work than women regardless of social class.

To summarize, the descriptive statistics indicate gender differences in both flexible and time-consuming working conditions and furthermore that these types of working conditions vary by occupational gender composition and social class. In the next step, these associations are explored with multivariate models.

Relationship between occupational gender composition and flexible working conditions

Model 1 in shows that women have less flexible working conditions than men do when controlling for occupational gender composition and parenthood, albeit only statistically significant at the 10-% level. We also see that parents with two children have more flexible working conditions than non-parents No significant interactions between gender and parenthood were shown (not displayed). Furthermore, model 1 shows that female-dominated occupations have, compared with other categories of occupation, significantly the least flexible working arrangements. The largest difference is between female-dominated occupations and gender-integrated occupations (21–40 and 41–60% female). Workers in the latter categories have much more flexible work arrangements.Footnote6 When testing interactions between gender and occupational gender composition, no significant interactions were found, indicating that men and women do not tend to differ in flexibility when working in occupations with similar gender composition (results available upon request).

Table 2. Flexible working conditions Linear probability model n:2285 (robust s.e.).

In model 2, social class and sector are added to the models. Flexible work is least common among manual workers which is the reference category. Employees in higher non-manual occupations have significantly the most flexible working arrangements compared with all other social class categories. Moreover, when controlling for class, the large difference between female-dominated occupations and the other categories of gender composition weakens, particularly the large difference between occupations with 40–60 percent women and female-dominated occupations. This weakening suggests that the lower access to flexible working conditions in female-dominated occupations compared with other categories of occupations can be partly attributed to employees in female-dominated occupations having lower skills (or social class). Flexible working conditions are however more common in male-dominated occupations and occupations with 20–40 percent female than in female-dominated occupations even when controlling for social class. Model 2 also shows that employees in the public sector, in which many women are active, tend to have less flexible working conditions compared with the private sector.

The pattern in Model 2 remains in Model 3 where a large battery of control variables is included. In model 3, we find required education, and initial training to be positively associated with flexible working conditions. These associations indicate that highly skilled workers are more likely to have access to flexible working conditions. Thus, in line with prior research (e.g. Chung, Citation2019b; Glauber, Citation2011; Swanberg et al., Citation2005), the results from Model 3 show that ‘privileged’ workers have greater access to flexible working conditions even when controlling for social class. We also find a positive association between time-consuming work and flexible working conditions, implying that time-consuming work goes hand in hand with flexibility. Of note is that part-time work has no significant association with flexible working arrangements.

To investigate whether there are any gender differences in the distribution of working conditions within classes, Model 4 includes interactions between gender and social class. Women in both the middle service class and the high service class have statistically significant (albeit only at 10% level for the high service class) less flexible working conditions than do men within these classes.

Relationship between occupational gender composition and time-consuming working conditions

In , the focus turns to time-consuming work. Model 1 shows a significant gender difference in time-consuming work; women have less of these working conditions, albeit only statistically significant at the 10% level. Parents have more time-consuming working conditions than non-parents, and this applies to both men and women (no statistically significant interactions were found between gender and number of children). Accordingly, these results do not indicate that mothers have less time-consuming work. However, having young children in the household tend to be negatively associated with time-consuming working conditions, for both men and women. Furthermore, the results in Model 1 show that all categories of occupations have statistically significant more time-consuming working conditions compared with female-dominated occupations, which is the reference category. Compared with female-dominated occupations, the amount of time-consuming work is greatest in gender-integrated occupations. The difference in time-consuming work between male-dominated and female-dominated occupations is small. Interactions between gender and occupational gender composition show no statistical significant (at the 5% level) interactions, indicating that men and women do not tend to differ in time-consuming work when working in similar occupational gender compositions (results available upon request).

Table 3. Time-consuming working conditions. Linear probability model n:2285 (robust s.e.).

When adding social class and sector to the model (Model 2), the differences between categories of gender compositions almost disappear. The only statistically significant difference is between occupations with 21–40 percent female and female-dominated occupations. This statement is also true when changing reference category. Examined together, these results suggest that the differences in time-consuming work between the categories of gender composition could partially be attributed to differences in skills (or social class) between the categories. Manual workers have less time-consuming work than employees in other social classes. Model 3 shows that time-consuming work is positively associated with years of education, required education and supervisory positions, while employees who work part-time tend to have less time-consuming work. These associations indicate that time-consuming work is more common among highly skilled individuals.

In model 4, we find gender differences in time-consuming work within social classes. Women in the middle service class and in the high service class have less time-consuming work compared with men in these classes.

Examined together, and show that both flexible and time-consuming working conditions are most common in occupations with rather balanced gender composition and least common in female-dominated occupations and in the public sector. Flexibility and time-consuming work appear to be most common among privileged groups in the labor market, but within these privileged groups, women’s work is somewhat less flexible and time-consuming.

Flexibility and time-consuming work clearly go hand in hand. The next step considers how these associations are related to wages and gender wage differentials.

Relationship between occupational gender wage gap and working conditions

The following analysis investigates the relationship between working conditions, gender and wages. Model 1, , displays a gender wage gap of approximately 7 percent when controlling for other known factors that hare relevant for wager differentials; years of education, work experience, share of female in the occupation, sector and social class.

Table 4. Unstandardized coefficients from an OLS-regression model of log hourly wages n:2285.

In model 2, we include flexible working conditions and find flexibility to be positively related to the wage level. The gender wage gap decreases to about 6 percent when accounting for flexibility. A negative, albeit only significant at 10% level, interaction between flexible work and gender were found, indicating that there are gender differences in payoff to flexibility.

Model 3 contains controls for time-consuming working conditions. Time-consuming work is positively related to wage. Compared with the coefficients in Model 1, the gender wage gap decreases partially (−0.070 to −0.056, approx. 20 percent). The interaction between time-consuming work and women is significantly negative, indicating that women obtain a lower economic payoff than men do for having time-consuming working condition. This indicates that a part of the wage difference between men and women can be explained by a gender differences in payoff to these conditions – to women’s disadvantages.

In the last model, Model 4, the combined measurement of flexibility and time-consuming work is tested. Thus, we do know that both flexibility and time-consuming work are positively related with wages and that these working conditions often are highly correlated. However, we do not know how the combinations of these working conditions are related to wages. Furthermore, the model includes interactions between gender and the combinations of working conditions to test whether there are any gender differences in the economic payoff to these combinations of working conditions.

All combinations of flexible and time-consuming working conditions have higher wages than does the reference category, which is having jobs with no flexibility and no time-consuming work. Having jobs entailing both flexible working conditions and time-consuming working conditions yields the highest economic payoff compared with all other combinations (a significant difference, tested by changing the reference category). All of the interactions in the model display gender differences in economic payoff for these combinations of working conditions to women’s disadvantage. However, the interaction between gender and having both time-consuming work and flexibility is not statistically significant.

Conclusions

Several conclusions can be drawn from present findings. First, women do not have more flexibility than men. In addition, there is no significant association between children in the household and access to flexibility. These findings do not provide support for the notion that women, and mothers, in particular, tend to choose or be assigned more flexible working conditions compared with men. Second, female-dominated occupations have, in comparison with other occupations, the least flexible work arrangements. In contrast to what is supposed in the mother-friendly job hypothesis, female-dominated jobs have working conditions that constrain rather than facilitate the relationship between family life and work life. Instead, somewhat gender-integrated occupations have the most flexible work arrangements. Third, flexible working conditions are strikingly positively associated with wages, implying that employees need not forgo high wages to achieve flexibility; instead, flexible working conditions come with high wages. Furthermore, flexible conditions are most common among managerial/professional workers and among workers with long initial training. Overall, the results support findings from prior research which have shown that access to flexible working conditions is greatest in high-paying and high-skilled occupations (Chung, Citation2019b; Glauber, Citation2011; Golden, Citation2009) and lowest in female-dominated occupations (Chung, Citation2019b; Grönlund & Öun, Citation2018).

Accordingly, these results give little support for the statement that the gender wage gap is due to women refrain from higher wages to access flexible work arrangements like some scholars have argued. Likewise, these findings counter the idea of compensating wage differentials.

The findings concerning time-consuming working conditions follow the same pattern as flexible work. That is, time-consuming work is most common in gender-integrated occupations and least common in male-dominated and female-dominated occupations. Higher non-manual workers and privileged workers have more time-consuming work. There is also a strong association between flexibility and time-consuming work. Thus, jobs include flexibility but concurrently claim a great deal of time. A result in line with prior research which has shown that flexible work time is associated with an increase of unpaid overtime (Chung & van der Horst, Citation2018).

Both flexibility and time-consuming conditions are positively related with wages. This has consequences for the gender wage gap. The gender difference is to some extent driven by gender differences in distribution of job characteristics, but mostly driven by gender differences in economic payoff to these job characteristics. Women are not economically compensated for their job characteristics to the same extent as men, especially not for their time-consuming work. This finding is in line with research from US (e.g. Winder, Citation2009) and Europe (e.g. Lott & Chung, Citation2016). Because both occupational gender composition and sector of employment are considered, it is difficult to explain the gender difference by noting that men and women work in different segments in the labor market.

Both flexibility and time-consuming work are much more prevalent in the service classes. That the amount of flexibility and time-consuming work is greatest among high-skilled workers is perhaps not surprising. As Williams et al. (Citation2013) assert, workers in high-status jobs are often considered ‘trusted workers’ and thus have more control over their work arrangements. Note that even when high-skilled workers largely have flexible arrangements, the degree of flexibility obviously also varies among this group. Flexible work is closely linked to the type of work performed in the occupations. For instance, there most likely are more difficulties with postponing a job task for a surgeon than for an engineer. To investigate working conditions, particularly gender differences in working conditions, within specific occupations would be an important and interesting future study that, however, requires a more large-scale dataset.

Another limitation of the study is that the measurement of time-consuming work is not optimal as I do not have a stringent measurement of demand of constant availability. The proxy used here, unpaid overtime (together with overtime work and overnight stays) is mostly related to commitment and performance. Thus, the employees are not economically compensated for their overtime work but they have high wages as their compensation for overtime work is already, in general, included in the normal wage. Accordingly, they are expected to work overtime if needed to meet the requirements that the position demanding, even if this implies working on evenings or weekends. They have to perform and to be committed to the workplace. Time-consuming work could thus be seen as related to performance-oriented flexibility.

This has parallels with the debate of types of flexibility, where some flexible arrangements could be seen as aimed to reconcile work with family while other forms, such as work time autonomy, is more oriented to performance (e.g. Chung & van der Horst, Citation2018; Ortega, Citation2009). Prior research has found gender differences in these types of flexibility, where women use flexibility to reconcile work and family, while men use flexibility to increase performance (e.g. Chung & Van der Lippe, Citation2018; Lott, Citation2018; Sullivan & Lewis, Citation2001). Here the findings point out gender differences in economic payoff for both types of flexibility, if we chose to consider time-consuming work as a type of performance-oriented flexibility. This indicates that women are compensated lower even when having access to performance-related flexibility.

All in all the findings presented here counters the notion that the remaining gender wage gap largely is due to women avoiding time-consuming work or choosing flexibility. Instead it seems like women are compensated lower even when they work under such job conditions. Women seem to have demands of constant availability in their work life but do not get the economic benefits of it. Furthermore, in line with prior research (e.g. Lott & Chung, Citation2016), the findings here, point out that flexible work arrangement are associated with high, and not low, wages, but the economic compensation for flexibility is gendered where women are less economic rewarded compared with men. Taken together, women’s preference towards or resistance against certain job characteristics does not explain why they are paid less. The problem lies elsewhere, and we need to refocus our attention to these factors, including employer’s perception on women’s performance outcomes, if we want to really readdress the gender inequalities in the labor market.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Charlotta Magnusson

Charlotta Magnusson is an associate professor of sociology at the Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University, Sweden. Her current research focuses on gender stratification in the labour market; in particular wage, occupational prestige and working conditions. Her work has recently been published in Acta Sociologica, British Journal of Sociology, and Work, Employment and Society.

Notes

1 Goldin (Citation2014) does not refer to these requirements as time-consuming working conditions. She instead shows that flexible schedules and flexible work arrangements have a negative effect on wages. However, she defines flexible working conditions such as not being able to work long hours and not being able to work at particular moments.

Workplace flexibility is a complicated, multidimensional concept. The term incorporates the number of hours to be worked and the particular hours worked, being ‘on call,’ providing ‘face time,’ being around for clients, group meetings, and similar. Because these idiosyncratic temporal demands are generally more important for the highly educated workers … . (Goldin, Citation2014, p. 1094)

2 According to Mood (Citation2010), there are major problems with comparing odds ratios across models and groups. To overcome this problem, the analyses are performed with LPM using robust standard errors to minimize heteroscedasticity problems.

3 Analyses including part-time work in this index have also been done. However, the correlations between part-time work and the other indicators of flexibility are low. Among those who could postpone their job task, could perform errands and had no fixed work time, there were only 19 individuals who worked part-time. Moreover, in Sweden, all parents are entitled to reduce their working time when having young children regardless of workplace or occupational arrangement. Part-time work can therefore not be considered a characteristic of a particular occupation or working condition, because employers cannot deny an employee with young children permission to reduce their working time (See also Grönlund & Öun, Citation2018). Because women are over-represented as part-time workers (Statistics Sweden, Citation2014), part-time work is important to consider when analyzing wage differences between men and women. Part-time work is thus not included in the combined measurement of flexibility but as a control variable.

4 Based on the question: ‘Apart from the competence necessary to get a job such as yours, how long does it take to learn to do the job reasonably well?’ (response categories: 1 day or less, 2–5 days, 1–4 weeks, 1–3 months, 3 months–1 year, 1–2 years, and more than 2 years). The response alternatives have been recoded into number of months.

5 Based on the question: About how many years of education above elementary school are necessary?

6 The relationship between flexible working conditions and occupational gender composition has also been tested with a linear variable that indicated that access to flexible working conditions increases as the number of women in the occupation increases. A squared term of percentage of women in the occupation also was included in these additional tests, showing that the positive effect of percentage of women decreases when occupations become highly feminized. Thus, these tests point in the same direction as the result presented here.

References

- Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4, 139–158.

- Allison, P. (1999). Multiple regression. A primer. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

- Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Blair-Loy, M. (2003). Competing devotions: Career and family among women executives. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cha, Y., & Weeden, K. (2014). Overwork and the slow convergence in the gender wage gaps. American Sociological Review, 79(3), 457–484.

- Chung, H. (2019a). Women’s work penalty in access to flexible working arrangements across Europe. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 25(1), 23–40.

- Chung, H. (2019b). National-level family policies and workers’ access to schedule control in a European comparative perspective: Crowding out or in, and for whom? Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 21(1), 25–46.

- Chung, H., & van der Horst, M. (2018). Flexible working and unpaid overtime in the UK: The role of gender, parental and occupational status. Social Indicators Research, 1–26. doi: 10.1007/s11205-018-2028-7

- Chung, H., & Van der Lippe, T. (2018). Flexible working, work-life balance, and gender equality: Introduction. Social Indicators Research, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s11205-018-2025-x

- Cotter, D., Hermsen, J., & Vanneman, R. (2003). The effects of occupational gender segregation across race. The Sociological Quarterly, 44(1), 17–36.

- Davis, A. E., & Kalleberg, A. (2006). Family-friendly organizations? Work and family programs in the 1990s. Work and Occupations, 33, 191–223.

- Daw, J., & Halliday Hardie, J. (2012). Compensating differentials, labor market segmentation, and wage inequality. Social Science Research, 41(5), 1179–1197.

- Deitch, C., & Huffman, M. (2001). Family-responsive benefits and the two-tiered labor market. In R. Hertz & N. Marshall (Eds.), Working families: The transformation of the American home (pp. 103–130). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Den Dulk, L., Groenevelda, S., Ollier-Malaterreb, A., & Valcour, M. (2013). National context in work-life research: A multi-level cross-national analysis of the adoption of workplace work-life arrangements in Europe. European Management Journal, 31(5), 478–494.

- Erikson, R., & Goldthorpe, J. (1992). The constant flux: A study of class mobility in industrial societies. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Erikson, R., Goldthorpe, J., & Portocarero, L. (1979). Intergenerational class mobility in three western European societies: England, France and Sweden. The British Journal of Sociology, 30(4), 415–441.

- Filer, R. (1985). Male-female wage differences: The importance of compensating differentials. Industrial & Labour Relations Review, 38, 426–437.

- Gallie, D., et al. (2012). Teamwork, skill development and employee welfare. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 50, 23–46.

- Glass, J. (2004). Blessing or curse? Work and Occupations, 31, 367–394.

- Glass, J., & Camarigg, V. (1992). Gender, parenthood and job-family compatibility. American Journal of Sociology, 98, 131–151.

- Glass, J., & Fujimoto, T. (1995). Employer characteristics and the provision of family responsive policies. Work and Occupations, 22(4), 380–411.

- Glass, J., & Noonan, M. (2016). Telecommuting and earnings trajectories among American women and men 1989–2008. Social Forces, 95(1), 217–250.

- Glauber, R. (2011). Gender, occupational composition, and flexible work scheduling. The Sociological Quarterly, 52, 572–494.

- Glauber, R. (2012). Women’s work and working conditions: Are mothers compensated for lost wages? Work and Occupations, 39(2), 115–138.

- Golden, L. (2009). Flexible daily work schedules in U.S. jobs: Formal introductions needed. Industrial Relations, 48(1), 27–54.

- Goldin, C. (2014). A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter. American Economic Review, 104(4), 1091–1119.

- Grestel, N., & Clawson, D. (2014). Class advantage and the gender divide: Flexibility on the job and at home. American Journal of Sociology, 120(2), 395–431.

- Grönlund, A., & Öun, I. (2018). In search of family-friendly careers? Professional strategies, work conditions and gender differences in work-family conflict. Community, Work & Family, 21(1), 87–105.

- Hill, J., Grzywacz, J., Allen, S., & Blanchard, V. (2008). Defining and conceptualizing workplace flexibility. Community, Work and Family, 11(2), 149–163.

- Jacobs, J., & Steinberg, R. (1990). Compensating differentials and male-female wage gap: Evidence from the New York state comparable worth study. Social Forces, 69, 439–468.

- Kassinis, G. I., & Stavrou, E. T. (2013). Non-standard work arrangements and national context. European Management Journal, 31(5), 464–477.

- Kelly, E. L., & Moen, P. (2007). Rethinking the clockwork of work: Why schedule control may pay off at work and at home. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 9, 487–506.

- Killingsworth, M. R., & Heckman, J. J. (1987). Female labor supply. In O. Ashenfelter & R. Layard (Eds.), Handbook of Labor Economics (Chapter 2, 1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 103–204). North-Holland, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Kim, J. (2018). Workplace flexibility and parent–child interactions among working parents in the U.S. Social Indicators Research, 1–43. doi: 10.1007/s11205-018-2025-x

- Korpi, W. (2000). Faces of inequality: Gender, class, and patterns of inequalities in different types of welfare states. Social Politics, 7, 127–191.

- Korpi, W., Ferrarini, T., & Englund, S. (2013). Women’s opportunities under different family policy constellations: Gender, class and inequality trade-offs in western countries re-examined. Social Politics, 20, 1–40.

- Kossek, E. E., Lautsch, B. A., & Eaton, S. C. (2006). Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control and work-family effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 347–367.

- Kurowska, A. (2018). Gendered effects of home-based work on parents’ capability to balance work with nonwork. Two countries with different models of division of labour. Social Indicators Research, 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s11205-018-2034-9

- Langer, L. A. (2018). Flexible men and successful women: The Effects of flexible working hours on German couples wages. Work, Employment and Society, 32, 687–706.

- le Grand, C. (1997). Kön, lön och yrke. In I. Persson & E. Wadensjö (Eds.), Kvinnors och mäns löner – varför så olika?. SOU:1997:136. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Lott, Y. (2018). Does flexibility help employees switch off from work? Flexible working-time arrangements and cognitive work-to-home spillover for women and men in Germany. Social Indicators Research, 1–24. doi: 10.1007/s11205-018-2031-z

- Lott, Y., & Chung, H. (2016). Gender discrepancies in the outcomes of schedule control on overtime hours and income in Germany. European Sociological Review, 32, 752–765.

- Lowen, A., & Sicilian, P. (2009). Family-friendly fringe benefits and the gender wage gap. Journal of Labor Research, 30(2), 101–119.

- Lyness, K. S., Gornick, J., Stone, P., & Grotto, A. R. (2012). It’s all about control. Worker control over schedule and hours in cross-national context. American Sociological Review, 77(6), 1023–1049.

- Magnusson, C. (2009). Gender, occupational prestige and wages: A test of devaluation theory. European Sociological Review, 25(1), 87–101.

- Magnusson, C. (2010). Why is there a gender wage gap according to occupational prestige? An analysis of the gender wage gap by occupational prestige and family obligations in Sweden. Acta Sociologica, 53(2), 99–117.

- Magnusson, C., & Nermo, M. (2017). Gender, parenthood and wage differences – The importance of time-consuming job characteristics. Social Indicators Research, 131(2), 797–816.

- Mandel, H. (2012). Winners and losers: The consequences of welfare state policies for gender wage inequality. European Sociological Review, 28, 241–262.

- Mandel, H., & Semyonov, M. (2005). Family policies, wage structures, and gender gaps: Source of earnings inequality in 20 countries. American Sociological Review, 70, 949–967.

- McCrate, E. (2005). Flexible hours, workplace authority, and compensating wage differentials in the US. Feminist Economics, 11(1), 11–39.

- Mood, C. (2010). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82.

- Nsiah, C., DeBeaumont, R., & Ryerson, A. (2013). Motherhood and earnings: Wage variability by major occupational category and earnings level. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34, 224–234.

- Ortega, P. (2009). Why do employers give discretion? Family versus performance concerns. Industrials Relations: A Journal of Economic and Society, 48(1), 1–26.

- Präg, P., & Mills, M. (2014). Family-related working schedule flexibility across Europe. In R. Europe (Ed.), Short statistical report No. 6. European Commission, Rand Europe. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR365.html.

- Riva, E., Lucchini, M., den Dulk, L., & Ollier-Malaterre, A. (2018). The skill profile of the employees and the provision of flexible working hours in the workplace: A multilevel analysis across European countries. Industrial Relations Journal, 49(2), 128–152.

- Rutherford, S. (2001). ‘Are you going home already?’ The long hours culture, women managers and patriarchal closure. Time Society, 10, 259–276.

- Schieman, S., Schafer, M. H., & McIvor, M. (2013). The rewards of authority in the workplace: Do gender and age matter? Sociological Perspectives, 56(1), 75–96.

- Schwander, H., & Häusermann, S. (2013). Who is in and who is out? A risk-based conceptualization of insiders and outsiders. Journal of European Social Policy, 23(3), 248–269.

- Smith, R. (1979). Compensating wage differentials and public policy: A review. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 32, 339–352.

- Statistics Sweden. (2014). På tal om kvinnor och män. Lathund om jämställdhet 2014. Retrieved from http://efsvasterbotten.se/wpcontent/uploads/2014/10/P%C3%A5-tal-om-kvinnor-och-m%C3%A4n.pdf

- Sullivan, C., & Lewis, S. (2001). Home-based telework, gender and the synchronization of work and family: Perspectives of teleworkers and their co-residents. Gender, Work and Organization, 8(2), 123–145.

- Swanberg, J., Pitt-Catsouphes, M., & Drescher-Burke, K. (2005). A question of justice: Disparities in employees’ access to flexible schedule arrangements. Journal of Family Issues, 2(6), 866–895.

- Thévenon, O. (2011). Family policies in OECD countries: A comparative analysis. Population and Development Review, 37(1), 57–87.

- van Oorschot, W., & Arts, W. (2005). The social capital of European welfare states: The crowding out hypothesis revisited. Journal of European Social Policy, 15(1), 5–26.

- Weeden, K. (2005). Is there a flexiglass ceiling? Flexible work arrangements and wages in the United States. Social Science Research, 34, 454–482.

- Williams, J. (2000). Unbending gender. Why family and work conflict and what to do about it. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Williams, J. (2010). Reshaping the work-family debate: Why men and class matter. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Williams, J., Blair-Loy, M., & Berdahl, J. (2013). Cultural schemas, social class, and the flexibility stigma. Journal of Social Issue, 69(2), 209–234.

- Winder, K. (2009). Flexible scheduling and the gender wage gap. The B. E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 9(1), 1–27. Article 30.