ABSTRACT

As of April 2021, nine states and the District of Columbia had enacted state-specific paid family leave (PFL) programs, offering partial wage replacement to parents after the birth of a child. The Biden Administration also proposed the development of a national solution through the American Families Plan. Despite these advances, concerns with workforce disruptions and economic costs have hindered wider adoption of PFL. While studies have documented the potential health benefits of PFL for women and babies, less is known about the mechanisms that lead to PFL potentially impacting women’s mental health. This mixed-methods study is based on focus groups with over 100 women in four states with operating programs and a secondary analysis of Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data. It presents evidence of how PFL may facilitate longer leave that possibly leads to improved mental health outcomes by providing more time at home. It also demonstrates that PFL may directly support mental health by providing women with increased financial security and work/life boundaries. Implications of PFL design features on access and shortcomings are also discussed. These results aim to inform national or additional state-level PFL programs that may benefit working women, their families, and their employers.

Introduction

Approximately 20 percent of mothers experience postpartum depression or a depressive episode following childbirth (Gavin et al., Citation2005; Miller, Citation2002). The consequences of postpartum depression can be severe for both mothers and babies (Slomian et al., Citation2019). Experiences of postpartum depression is a predictor for mental health challenges later on, and women with higher depression scores may be less able to control their emotions and have higher levels of anger, anxiety, and lower reported quality of life (Slomian et al., Citation2019). Postpartum depression is also linked to poor infant outcomes such as reduced weight gain and overall growth (Slomian et al., Citation2019). Three studies found that infants of depressed mothers had three times the number of episodes of diarrhea as compared to infants with non-depressed mothers (Slomian et al., Citation2019).

Mental health issues occur more often among postpartum mothers who work (Chatterji & Markowitz, Citation2005; Gjerdingen, Citation1993; Gjerdingen et al., Citation1995; Hyde et al., Citation1995), particularly if they return to work soon after birth (Miller, Citation2002). This may be partly attributable to conflict between work and family, which is associated with feelings of depression, anxiety, and poor mental health (Frone et al., Citation1992, Citation1996; Grice et al., Citation2011). Grice et al. (Citation2011), for example, found that pressures of work and family were associated with significantly lower self-reported mental health scores among employed mothers in the Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota metropolitan area. Though six weeks of leave following birth is considered an adequate amount of time to physically recover from childbirth (National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care, Citation2006), 76 percent of mothers in the United States still experience fatigue related to depression and breastfeeding issues at eight weeks postpartum (Cheng et al., Citation2006).

At the federal level, the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) (1993) ensures up to 12 weeks of job-protected leave for eligible workers to bond with a new child, care for an ill family member, or take personal medical leave (U.S. Department of Labor, Citation2022). Although FMLA was progressive for its time, it has shortcomings. Most importantly, FMLA does not offer any paid leave, and thus fails to address the financial pressures facing families who depend on parent earnings. Currently, nine states and the District of Columbia have enacted paid family leave (PFL) policies (Stamm et al., Citation2022). Policymakers have also proposed national solutions to expand paid leave options for working families. In fact, the Biden Administration proposed the development of a comprehensive national plan through the American Families Plan (The White House, Citation2021). However, the economic costs to employers, employees, and potentially taxpayers, as well as perceived workplace disruptions, continue to be major barriers to broader PFL legislation (Rossin-Slater et al., Citation2013).

PFL offers partial wage replacement to parents after the birth of a child. While programs vary by state, the benefit is often coupled with disability leave, giving mothers approximately 12–14 weeks of paid time off to recover from childbirth and care for their babies (Romig & Bryant, Citation2021). Studies show that time away from work likely improves women’s financial security and job stability (Appelbaum & Milkman, Citation2011) and health outcomes for babies by facilitating breastfeeding (Andres et al., Citation2015; Berger et al., Citation2005; Huang & Yang, Citation2015; Kottwitz et al., Citation2016; Mirkovic et al., Citation2016). Leave time can also support mothers’ mental health (Doran et al., Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation1982; Mandal, Citation2018), which is especially important given stress and emotions tied to pregnancy, birth, and becoming a new parent (Doran et al., Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation1982; Mandal, Citation2018). However, the vast majority of studies focusing on leave time following birth do not distinguish between paid and unpaid leave, and even fewer studies focus on the mechanisms behind why leave improves outcomes. Leave outcomes have primarily been studied quantitively, which means that while there is evidence that indicates that leave time can improve women’s mental health outcomes following birth, there is very little research on why the outcomes improve.

Initial research on leave has indicated that mental health outcomes may be improved by easing financial stress associated with taking unpaid leave and by facilitating breastfeeding establishment without the stress of work (Butcher & Schanzenbach, Citation2018; Goodman et al., Citation2020). The reduction of financial stress is an important component of PFL programs, as the Human Rights Watch (Citation2011) found through their interviews with mothers that many believed the financial stress of unpaid leave worsened their depression. As a result, the longer the unpaid leave, the deeper the financial and emotional stress. In fact, researchers have found that women take shorter leaves when the leave is unpaid, likely due to the financial stress of not having an income while on leave (Hofferth & Curtin, Citation2006; McGovern et al., Citation2007). McGovern et al. (Citation2007) found a four-week difference between the length of leave between mothers with paid and unpaid leave.

PFL may also indirectly benefit breastfeeding by providing women with more time at home with their babies. Breastfeeding has physical and psychological health benefits for mothers and babies (Chatterji & Frick, Citation2005). Despite the value of breastfeeding, only 35 percent of women continue to breastfeed after six months (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2021). There may be a connection between leave duration and the initiation of breastfeeding; mothers who returned to work between six and 12 weeks after giving birth were two to four times less likely to establish breastfeeding than those who took longer leaves or who did not return (Guendelman et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, many researchers found that returning to work can be a major obstacle to breastfeeding continuation (Human Rights Watch, Citation2011; Minnesota Department of Health, Citation2015; Rowe-Finkbeiner et al., Citation2016; Schulte et al., Citation2017). Mothers may be more likely to stop breastfeeding after maternity leave given the opportunity cost of breastfeeding rises significantly with work (Andres et al., 2016; Berger et al., Citation2005; Chatterji & Frick, 2005; Huang & Yang, Citation2015; Kottwitz et al., Citation2016; Mirkovic et al., Citation2016).

This study, commissioned by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women's Health, supports existing research and provides evidence on how PFL may impact women’s mental health behaviors and outcomes. This is one of few mixed-methods studies in the United States to explore the relationship between PFL and women’s mental health. Previous studies have primarily relied on quantitative data, which cannot sufficiently explore how and why PFL may improve mental health outcomes for women. The motivation of this study was to provide insight into the health effects of state paid leave policies and the barriers and facilitators that contribute to women’s health and wellbeing within a year of childbirth. This information is valuable in the development of paid leave policies at both the national and state levels.

Our study focuses on four states with active PFL programs at the start of the project in 2019: California (implemented 2004), New Jersey (implemented 2009), Rhode Island (implemented 2014), and New York (implemented 2018). A quantitative analysis drew on the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) survey data to demonstrate that women with paid leave may experience better mental health outcomes. Findings from focus groups conducted with 106 mothers in the four study states help explain this positive associative relationship, primarily by giving women more time at home, financial security, and work/life boundaries. Implications of PFL design features on access and shortcomings of the program are also discussed.

Materials and methods

This mixed-methods study relies on data collected through focus groups with 106 women and national survey data. This research received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and followed all ethical guidelines for human subjects research. Focus groups were conducted in California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and New York. Survey data was collected from PRAMS, 2012–2018. These methods and their limitations are discussed below.

Focus groups

We conducted twenty focus groups with 106 mothers in California (33 participants), New Jersey (19 participants), Rhode Island (27 participants), and New York (27 participants) between January and June 2020 (see ). We recruited women through social media ads, online forums for mothers, and local organizations that work with low-income families. Interested women were screened by phone to determine focus group eligibility. Women had to be eligible for PFL programs in their states, regardless of whether they used the benefit or not, and had babies between 12 weeks (the typical amount of time to complete disability leave and PFL) and one year old. Focus groups addressed themes related to women’s postpartum physical and mental health and perceived impacts of PFL.

Table 1. Characteristics of Focus Group Participants by State, Focus Group Survey.

Focus groups were conducted in-person and virtually in multiple geographic areas throughout each state to ensure the representativeness of urban, suburban, and rural participants. Overall, focus group participants were diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, and income and generally reflected the overall demographic characteristics of the state with some minor exceptions. Participants in New York, New Jersey, and Rhode Island tended to be slightly higher income and were more likely to be white than in state populations overall (see ). Additionally, focus group participants in California had a higher share of participants who had lower incomes and were Hispanic than the state population as a whole, partially due to the successful recruitment of social service organizations in California who supported our participant requirement efforts. Approximately 25 percent of focus group participants did not use the program despite being eligible.

Prior to each focus group, participants were given a survey that collected information on demographic characteristics, work status, and health behaviors. The survey captured discrete data such as the length of leave, duration of breastfeeding, and whether or not participants attended their six-week postpartum appointment. Focus group discussions were recorded and transcribed. The research team coded transcripts in a qualitative data analysis software, NVivo 12, using a code set based on key research questions and themes that emerged from the literature review and pilot focus groups. All coding was conducted by members of the research team who actively participated in the focus groups, either through facilitation or logistical support. Coders frequently met to discuss data segments and to develop and maintain coding standards.

We developed several structured data fields from focus group discussions, including whether women experienced severe maternal morbidity or suffered from postpartum depression. We linked focus group discussion segments to survey and structured focus group responses with pseudonyms women used during focus groups and surveys through qualitative data analysis software. This methodology allowed researchers to analyze data by use and non-use of PFL.

Survey data

The research team also analyzed PRAMS survey data, which captures women’s attitudes, behaviors, and physical and mental health conditions surrounding pregnancy. PRAMS (2012–2018) contains data on 38 states. We assessed the relationship between paid leave and self-reported feelings of depression following birth, a postpartum depression indicator created in PRAMS and the differences in length of leave between those with paid and unpaid leave. Propensity score matching was used to explore the relationship between paid leave and women’s experiences of depression following birth. Rank-sum analysis was used to demonstration the connection between paid family leave and longer leave time. The PRAMS survey did not differentiate between PFL and PTO offered by a woman’s employer, so our analysis focused on paid leave of any kind, rather than specifically on PFL.

To evaluate the relationship between paid leave and mental health, we examined postpartum mental health indicators in PRAMS for the years 2012–2018. We analyzed data for all 38 states that participated in the survey and separately for New Jersey and New York, which implemented their PFL programs in 2009 and 2018, respectively. California did not participate in PRAMS. Unlike New Jersey and New York, Rhode Island participated in the PRAMS survey but did not include a paid family leave or length of leave indicator in its data collection processes. We assessed overall rates of depression through two indicators: self-reported feelings of depression following birth and a postpartum depression indicator created in PRAMS from a set of responses, including respondent discussions with providers about depression and the self-reported depression response. Women were asked to self-report their level of depression, indicating whether they never, sometimes, often, or always felt depressed. To test the significance of these responses, we dichotomized that indicator in two ways: 1) those who indicated they felt depressed always, often, or sometimes following birth, and 2) those who indicated they felt depressed always or often following birth. These responses were compared for women with paid and unpaid leave to see if these two groups of women experienced different levels of self-reported depression following birth.

While we aimed to compare these mental health outcomes for women who reported taking state-level PFL to those who did not, Rhode Island did not include questions about work leave following birth, and New Jersey and New York did not include a specific question about whether the respondent’s paid leave was state-sponsored. However, we expect that the effect of paid leave is independent of the sponsor because benefits should occur through the financial security afforded by paid leave. State-level PFL merely expands the pool of women who can access paid leave. Therefore, any effect we may see for paid leave is expected to work through both employer-sponsored leave and state-sponsored leave.

Based on the findings of our environmental scan, we assumed that external factors associated with use of paid leave may also influence whether new mothers experience depression (Cheng et al., Citation2006; Miller, Citation2002). To control for these factors, we used propensity score matching to create two analysis groups, women who took exclusively paid leave and women who took exclusively unpaid leave, for which confounding factors were distributed equally across the groups. The factors we controlled for were education level, income, marital status, and race. Other factors, including job satisfaction and family dynamics, may also influence depression (Cheng et al., Citation2006; Miller, Citation2002), but are outside the scope of this analysis as these variables were not clearly delineated in the survey. Using propensity score matching, we ensured that the variation in our selected factors was equal across groups.

Paid leave in the PRAMS survey is operationalized as a yes/no response to the question, ‘Did you take leave from work after your new baby was born?’ Responses to this question include, ‘I took paid leave from my job’, ‘I took unpaid leave from my job’ and ‘I did not take any leave.’ For our analysis, we compared women who indicated that they took paid leave to women who indicated they took unpaid leave. The PRAMS survey also asked if respondents had already returned to work and how many weeks of leave, in total, they took from their job or planned to take after their most recent pregnancy. We limited our analysis to women who indicated that they had already returned to their jobs. Therefore, we were able to determine the number of weeks women took off from work following the birth of their child and if that leave was paid or unpaid. An important limitation to this analysis is that PRAMS did not give respondents a way to indicate if they took both paid and unpaid leave. From our focus group findings, we believe it is likely that at least some women who indicated that they took paid leave also took unpaid leave. Therefore, our analysis likely compares women who took any paid leave to women who took only unpaid leave.

Limitations

We intended to recruit an equal number of women who had used PFL and eligible women who had not. However, recruiting eligible non-users was a challenge. Due to these challenges, 75% of the focus group participants in the study used PFL. Previous studies indicate that women with lower incomes or language barriers may be less likely to use PFL. For this reason, we developed recruitment techniques that attempted to reach these women, such as partnering with social service agencies and developing recruitment materials in Spanish. Despite these efforts, the majority of focus group participants had participated in PFL. The focus group participants who did not use PFL, often because they did not know about the program or think they were eligible, tended to have lower incomes. Some experiences and views may have been missed for non-PFL users.

Results

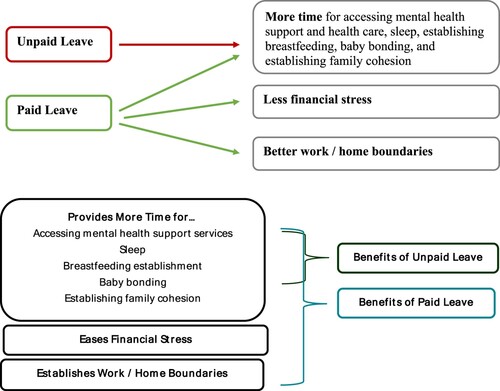

Several potential direct and indirect benefits of paid family that may support women’s mental health have been identified through this study (). These potential benefits are discussed in the sections below. Findings related to women’s mental health challenges in the postpartum period are discussed, followed by how longer leave times and paid family leave may be associated to better mental health for women in the postpartum period.

Virtually all women in the focus groups experienced challenges with mental health during the postpartum period

Regardless of whether participants used PFL, focus group participants universally faced mental health issues. Women described feeling like their lives had flipped upside down or that there wasn’t enough time in the day. Many women reported feeling like they were juggling a new baby and the day-to-day responsibilities of taking care of themselves, their homes, and their families. Journee (CA), who took four weeks of leave (WOL), described her postpartum experiences as hectic and said she still struggled even though her baby was 10 months old. Journee said,

It was a struggle juggling working and taking care of children and not being in tune with myself and not putting myself first after pregnancy. So that was a big concern for me because I didn't really get that time. Even now I don't get that relaxation because I feel like I'm still juggling with an infant, an older child, and there's just no time to decompress. – Journee, CA, 4 WOL –

Paid leave is related to better mental health

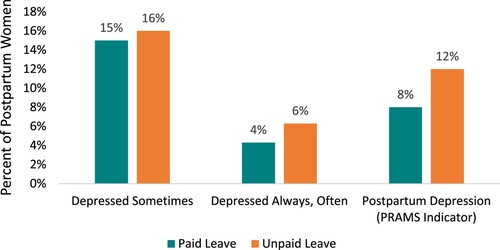

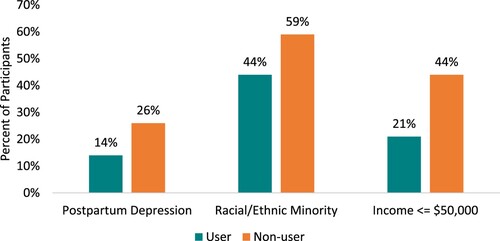

Our analysis of Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) found that that paid leave may support women’s mental health. Propensity score matching showed that women who took paid leave were significantly less likely to report being depressed following birth after adjusting for covariates (see ). About a quarter of women with paid leave reported feelings of depression always, often, or sometimes compared to 28 percent of women with unpaid leave. Similarly, propensity score matching showed women with paid leave were significantly less likely to be identified through PRAMS as having postpartum depression (8 percent compared to 12 percent). We found that for these measures, women with paid leave showed statistically significant lower rates of depression when we controlled for education level, income, marital status, and race. Among focus group participants, PFL users were less likely to experience postpartum depression than non-users of the program (14 percent compared to 26 percent, see and ), following findings from PRAMS and the literature.

Figure 2. Depression Indicators by Paid or Unpaid Leave, PRAMS 2012–2018 (n = 24,161). Source: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012–2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/prams/index.htm

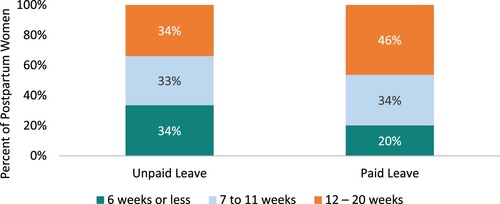

Figure 3. Length of Leave by Leave Status, PRAMS 2012–2018 (n = 24,161). Source: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012–2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/prams/index.htm

Table 2. Characteristics of Focus Group Participants by PFL Use, Focus Group Survey.

PFL helps mitigate postpartum mental health issues through more time, financial security, work/home boundaries and facilitating partner support

Focus group discussions built on the findings from PRAMS and revealed how PFL may lead to benefits related to mental health, both directly and indirectly. We identified four mechanisms through which PFL may improve mental health: providing financial peace of mind, creating work-related boundaries, facilitating partner support and, most importantly, offering more time at home. Providing financial peace of mind and creating work-related boundaries are possible direct benefits of PFL. While offering more time at home and facilitating partner support are direct benefits of longer leave time which may be partially enabled by PFL. While focus group and survey data indicates that PFL may enable women to spend more time at home on average, there are many avenues through which women may take leave following the birth of a child. This is clear from our finding that that average length of leave for women who did not take PFL in the focus groups was 12 weeks. Even though these women did not use the six weeks of leave offered by PFL, they often found a way to remain home with their babies. However, women who did take PFL averaged 19 weeks at home, or seven weeks longer than women who did not take PFL. With this additional time, women reported that they were able to better access mental health services, sleep more, establish breastfeeding, and bond with their babies. While some women could choose to take longer unpaid leave, the data from PRAMS and focus groups indicated that there were barriers to taking extended unpaid leave, and women taking unpaid leave returned to their jobs on average earlier than women with paid leave .

Table 3. Results of Rank-Sum Test for PRAMS Length of Leave Analysis.

Direct benefit of PFL: financial ‘Peace of Mind’

Women often experience financial anxiety after the birth of a baby due to mounting expenses and a reduction in income from time off work or reduced hours. Focus group participants described how the additional costs of a new baby, including formula and diapers, generated stress. In addition, several women noted anxiety due to employer cuts to their work hours or having to cover health insurance expenses while they were not working.

Women commonly reported that PFL reduced stress by giving them financial peace of mind. For example, Mila (CA, 16 WOL) noted that ‘just knowing that you have some sort of income coming in, you have to see which [expenses] you’re going to move around, but it was a little less stressful.’ A handful of participants indicated that PFL helped them finance additional activities and services that improved their mental health. For example, with her PFL money, one participant was able to maintain childcare for her toddler to focus on the baby. Maddie from RI who took 16 WOL said,

You’re facing all kinds of new expenses, with a new baby. You need to buy, maybe newer bottles than the ones you bought previously, because the ones you thought you needed aren’t working for this baby. Just the expenses are there, and then to take time off and not get paid. It’s such a relief to know that your state is looking out for you a little bit. – Maddie, RI, 16 WOL –

Table 4. Results of Depression Indicators by Paid or Unpaid Leave, PRAMS 2012–2018 Propensity Score Analysis.

Despite the overall peace of mind many women discussed in the focus groups, some women reported that they found paying health insurance premiums while on leave stressful. California, Rhode Island, New York, and New Jersey all require employers to continue paying their normal contributions to their employees’ healthcare coverage while they are on pregnancy disability leave. However, in each state, PFL users may be expected to continue paying their normal share of their insurance premiums (LegiScan, Citation2012; New York State, Citation2021b; Prudential, Citation2021; State of New Jersey, Citation2019). This means that some women reported they had to write their employer a check for their insurance premiums every two weeks. Other women reported that several months of premiums were deducted from their paychecks when they returned to work. This experience represented a financial burden while many were not receiving 100 percent of their paychecks and was reported as stressful given mailing a check was one more thing to remember while on leave. Jessica (RI, 12 WOL) said, ‘My employer took out my insurance payments all at the end. So, when I returned to work, they took out three months of my insurance, so that wasn't helpful.’ Women also reported that they were reluctant to expand their leave with unpaid time off for fear of losing their insurance if they did not return to work promptly after their PFL, or disability in the case of non-users, ended. Victoria (CA, 17 WOL) said,

I wasn't going to get [my healthcare] covered until I went back to work. [My employers] were telling me I was going to have to pay like $1,000 for the month of August if I didn't go back to work for that month … I could have taken another six weeks unpaid, which I would have preferred, but I couldn’t afford to pay the insurance. It was a little stressful. – Victoria, CA, 17 WOL –

Direct benefit of PFL: establishment of work-related boundaries, reducing related stress

Focus group participants reported that PFL also improved mental health by giving women a set amount of time to be away from work. Women did not have to request time off, negotiate with their employers, or as reported by Peach (NY, 12 WOL), ‘worry about should I go back now.’ Women also felt comforted because they believed they would not be fired while on PFL and could, therefore, disconnect from work knowing their leave was defined. This was notable, as only Rhode Island and New York have legal job protection built into the state’s PFL polices. In California and New Jersey, women can be dismissed from their job while taking PFL, though many women who take PFL also qualify for FMLA, which does offer job protection (U.S. Department of Labor, Citation2022). Despite official job protection status, women in all states felt leave taken through PFL was more accepted by their employers because the length of the leave was defined by the state rather than by the women themselves.

Benefit of longer leave time: more time away from work

Women in the focus groups reported taking a combination of paid time off offered by their employers (PTO), unpaid leave, TDI, and PFL following the birth of their babies. By combining these leave types, many users of PFL were able to take more than 12–14 weeks of leave offered by a combination of TDI and PFL. Similarly, women who didn’t take PFL were able to take longer leave than the six weeks of TDI they could have taken. Anna from CA, for example, took six weeks of TDI, six weeks of PFL, and nine weeks of PTO for a total of 21 weeks of leave following the birth of her baby. Lily from RI did not take PFL, but she did take six weeks of TDI prior to giving birth, followed 13 weeks of TDI after giving birth for a total of 19 weeks of leave. Lily was able to take so much leave despite not using PFL due to ongoing complications related to prenatal hypertension that extended her TDI. While her case is unusual, it does demonstrate the varied nature of women’s leave taking.

Focus group participants reported that longer leave time from work allowed them to adjust to their new schedules, thus reducing stress and anxiety. In addition, participants indicated this extra time gave them more opportunity to engage in positive mental health behaviors such as sleep, self-care, and professional and social supports. However, the data did not indicate that non-PFL users always took very short leaves. In fact, women in the focus groups who did not take PFL took an average of 12 weeks of leave, which is the time allotted by most state’s combined PFL and TDI programs. However, women who took PFL took an average of 19 weeks. This may indicate that while PFL empowered women to take longer leaves, many women did not feel like the 12 weeks was sufficient. In this sense, the strength of PFL may come from offering new parents the opportunity to stack unpaid and paid leave to gain more time off, rather than in the 12 weeks allotted by PFL and TDI. However, despite this important distinction, women did speak highly of their PFL experience, and believed it was important for their mental health. Women often indicated that they did not have the time to address their mental health once they returned to work, highlighting the importance of taking as much time off as they could. For example, Bianca (NY, 20 WOL) took the full 12 weeks of PFL and eight weeks of unpaid leave. She reported that if she had not had PFL she would have had to return to work after eight weeks. While she would still have been able to take those eight weeks of unpaid leave without PFL, Bianca believed that the 20 weeks she was able to get because of PFL improved her experience. Bianca said,

I have literally been out since I had my baby. So, I’ve been able to recover and be able to get my mental health right. I was struggling with depression right after birth. If I didn’t have paid family leave, I would have had to go right back to work a few weeks after having him and I don’t think that would have been enough time for me to get myself together. I work with small kids and they’re very energetic and I didn’t want to be ill around them. – Bianca, NY, 20 WOL –

Figure 4. Demographic Comparison of PFL-Users and Non-Users (n = 106), Focus Group Participants. Source: Primary focus group survey data.

Access Professional Mental Health and Social Support. The majority of focus group participants (95 percent) were screened for mental health concerns during well-baby or postpartum health appointments, which typically occur around eight week postpartum. At these appointments, women were connected to professional support if needed for mental health concerns. Focus group participants reported that longer leave facilitated entry into these professional therapeutic supports, primarily by allowing them to attend appointments at a time of day when they otherwise would have been at work. Among women who did not take paid family leave, 26% returned to work before eight weeks. These women needed to schedule not only their ongoing mental health treatment around work, but their initial postpartum check-up where many issues were first identified. Among women who took PFL, 10 weeks was the shortest leave time, meaning that all the PFL users would have been able to attend their postpartum check-up while still on leave. Women who returned to work early reported delaying or foregoing treatment because of their work schedules. Several women in the focus group reported that mental health support was critical for their and their baby’s wellbeing. Jenny (NY, 12 WOL) reported that when her baby was three and a half weeks old, she ‘couldn't care less if he was in the room or not’ and ‘realized that maybe something else was going on.’ She indicated that ‘the leave was good’ because she could start seeing a therapist on a weekly basis at the hospital where she gave birth. While this leave could have been paid or unpaid, women with PFL were all able to access the initial postpartum checkup, while over a quarter of women without PFL struggled to schedule the appointment around work.

Similarly, women described the therapeutic benefit of moms’ groups and the role of ongoing leave, whether paid or unpaid, in supporting access. Kristen (RI, 29 WOL) shared that, ‘it’s like therapy too.’ Anna (CA, 21 WOL) described joining a new moms’ group as ‘really helpful to have people going through the same experiences at the same time.’ Participants pointed out that they would not have been able to join these groups if they were not on leave because groups typically meet during the workday. Of the 12 women who discussed joining a mom’s group, only two of them did not use PFL. Of these two women, one took 12 weeks of leave total, using six weeks of TDI and six weeks of unpaid leave. The other woman had not yet returned to her job, as she was planning on taking two years of unpaid leave. Other non-PFL users indicated that mom’s group were not feasible give their work schedules. Maria (CA, 2 WOL), who did not take PFL, indicated that she was unable to access support due to work conflicts. She said,

When I started having really bad anxiety issues I realized, ‘You can’t go to these groups, they're 10:00 am Tuesday.’ A lot of these social services are setup with the assumption that you're either a stay-at-home mom, or you're on leave. – Maria, CA, 2 WOL –

Women who took shorter leave times reported sleep challenges related to contending with returning to work and a new infant. While many women who did not take PFL did have longer leave times, all the women who took less than 10 weeks of leave did not use PFL. Journee (CA, 4 WOL) said,

It's hard because I'm juggling with lack of sleep because I'm taking care of the baby during the day and working at night. Disability helped a lot. When I had to go to work, that was a hard transition because I had to fit a time management for myself, like when I needed to get that sleep. I'm working opposite schedules with my partner. – Journee, CA, 4 WOL –

Somewhere around the eight to 10-week mark I felt more physically normal and capable. That said, I felt like there were a lot of other demands on my body. I wasn't in pain, but things were very difficult to manage due to lack of sleep. Getting up in the middle of the night and then having to get to class at 9:00 AM was a struggle. – Mollie, NY, 5 WOL –

More Time in Which to Establish Breastfeeding. Research and data analyzed in this study show an association between breastfeeding, postpartum mental health, and leave time. Focus group participants often demonstrated that breastfeeding, whether it comes easy or is a challenge, can impact mental health positively or negatively. Several focus group participants who successfully breastfed described breastfeeding as calming and enjoyable. Women who faced challenges with breastfeeding, on the other hand, reported experiencing stress and anxiety given they wanted to provide their babies with what they saw as an important benefit.

Focus group participants also described the challenges they faced with breastfeeding when they returned to work, especially related to the decrease in milk production, their babies’ inability or unwillingness to take a bottle, and lack of employer accommodations for pumping. Several women indicated they felt like they had to choose between breastfeeding and treating their mental health issues through medication. Camryn (CA, 10 WOL) for example, opted to take medications instead of breastfeeding because she felt like she was not able to be the mother she wanted to be without getting support. She said, ‘I wasn't going to be able to be a mother to my son if I hated him. I need to fix myself because how [else] can I be a good parent to him?’

Given the inherent challenges of breastfeeding, exacerbated by work-related barriers, focus group participants indicated that longer leaves gave them more time to establish breastfeeding before having to return to work, reducing overall stress and anxiety. Participants were able to access lactation services during their leave. Alanna (CA, 16 WOL), who did not use PFL because she did not know about the program, said, ‘See, if I was getting paid family leave, I probably would’ve still been breastfeeding my daughter because I stopped breastfeeding [when] I went back to work, and my milk actually stopped.’ Alanna reported that she quit her job soon after returning due to the stress of trying to balance a work schedule at newborn baby. Ali (RI, 12 WOL), who was able to take PFL, described a different experience despite take less leave than Alanna. Ali highlighted how her 12 weeks of PFL/TDI helped facilitate breastfeeding. While these examples do not indicate that a woman must take PFL to successfully breastfeed, it does indicate how women believed PFL helped facilitate breastfeeding. Ali said,

I don't think that I would have breastfed at all if I didn't have [PFL] because I needed that time to … get used to it. It was really difficult, and I had a lactation consultant come in, and [nurses from home visiting programs] came to help that I wouldn't have been able to. I was really stressing out about it, and it wasn't working. He wasn't latching correctly and the whole thing, so I definitely needed that time. – Ali, RI, 12 WOL –

Additional Bonding Time. Given emotional ties between mother and baby, the return to work can be painful for some women, especially with young infants. When women returned to work, they reportedly missed their babies, experienced guilt that they were losing out on key milestones and felt anxious over the quality of their babies’ care. Separation anxiety was a common source of stress for women in the focus groups, often related to the need to put their babies in childcare when they returned to work. This anxiety was often exacerbated for women who had physically or mentally demanding jobs, long commutes, or difficulty maintaining breastfeeding while working. Maribel (CA, 8 WOL) said,

I was just crying all the time. I just felt like, ‘Oh, I’m not a good enough mother,’ or, ‘What if something happens to the baby?’ I was very overwhelmed. I felt like even just taking out the trash was overwhelming. Even now I still get sort of thoughts in my head. Not of harming or anything, but more like, ‘Oh, is the baby even going to love me because he’s not with me?’ – Maribel, CA, 8 WOL –

It is important to note that focus group participants who did not use PFL did not all enroll their babies in daycare following the end of their leave from work – 29% of non-users quit their jobs following the birth of their babies, and either had no plans to return to work or planned to return to a different job when they were able to. Of PFL users, only 11% left their job after the birth of their babies. This may indicate that some non-users chose to leave their positions, rather than return to work before they felt they are their babies were ready. Others, like Alanna, tried to return to work soon after birth but found it too difficult and quit. This is in line with other findings from the literature which indicates that PFL may facilitate work retention for women (Winston et al., Citation2019).

Additional support from partners due to partner’s use of leave

When their partners were able to take extended leave whether unpaid, PFL, or through work, the women in the focus groups reported that their partner’s leave supported family cohesion by giving them time to bond as a family and establish patterns and routines. Women reported that the time they were able to take as a family was very special to them, and that they appreciated the support they received from their partners. This, in turn, improved women’s mental health by making them feel that they were part of a team, rather than facing the challenge of a new baby alone. Mayflower (NY, 2 WOL) for example, said that ‘[My husband’s] PFL helped us to get into the swing of everything.’ Jane (NY, 8 WOL) indicated that without the first six weeks she and her husband had together she wasn’t sure they ‘would be the parents that [they were] today.’ Lily (RI, 19 WOL) reported a similar experience. She said,

When you see your husband taking such good care of your child it just makes you fall in love with him even more. Having him able to be so hands on from the start made him more involved and more invested, totally all in. I think it really helps your relationship. – Lily, RI, 19 WOL –

[My partner’s use of PFL] allowed us to be home together in the first six weeks right after. It helped us to get a rhythm co-parenting and figure out our family unit together. So, it didn’t feel like I was having to learn everything about [our daughter] and then having to try to relay that information while everything else was happening. – Joey, CA, 12 WOL –

Financial anxiety also contributed to the leave-taking behaviors of the partners of the women in the focus groups. Women indicated their partners did not take PFL because they could not get by on only 60 percent to 70 percent of their salaries. This was especially true if the partner was already the primary breadwinner prior to the participant’s pregnancy. Abigail (NJ, 22 WOL), for example said, ‘My husband did not take PFL because we needed a hundred percent paid. We didn’t need partial pay.’

PFL access and shortcomings

Despite indicating positive benefits associated with PFL and longer leave-taking in general, our study also found barriers to using PFL, which limited access and positive impact. One in four of the focus group participants did not use PFL despite being eligible. Barriers discussed in the focus groups included restrictive or confusing eligibility requirements, lack of information or incorrect information, concern for employment repercussions, and wage replacement levels.

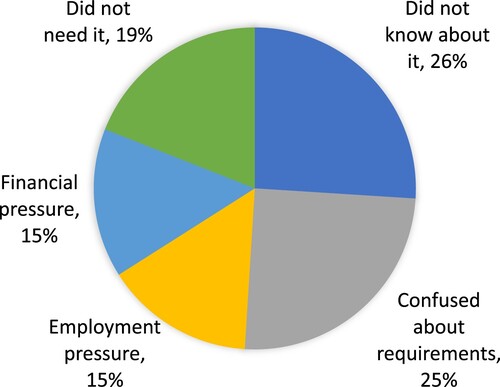

Some women in the focus groups did not take PFL because they did not feel like they could take the time from work (15 percent of non-users) (see ). One participant shared that during her disability leave period, she felt worried and concerned about the type of environment to which she would return. She said, ‘that's why I am waiting to use my [PFL] because I feel like if I took more time out, I don't know, they would find a reason to get rid of me somehow.’

Figure 5. Reasons Why Women Who Were Eligible for PFL Did Not Take the Benefit, Focus Group Participants. Source: Primary data collected from focus group participants.

Other women did not take their leave because they needed their full wages instead of the 60 percent to 70 percent typically offered by PFL at the time of the study in 2019 (New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, Citation2021; New York State, Citation2021a; State of California Employment Development Department, Citation2022; The Economic Progress Institute, Citation2021). Mayflower (NY), for example, took two weeks off because she ‘really needed to get back to work,’ and Journey (CA, 4 WOL) stated, ‘financially, it's not worth it to stay. You can't survive off the little amount that they give you.’ Misunderstanding was also a substantial barrier to PFL usage. A quarter of these non-users were unaware the program existed. Another quarter of non-users in the focus groups did not participate in PFL because they thought they were not eligible.

Finally, about a fifth of eligible women in the focus groups did not participate in the program because they did not need it. Of those, one was able to take four months of employer-sponsored leave before returning to work. Another participant took two weeks of paid time off (PTO) and extended her disability leave to 12 weeks after being diagnosed with postpartum anxiety. After 14 weeks, she felt ready to return to her work as a nurse and decided not to take PFL.

While women who were not eligible for PFL were excluded from this study, our screening process revealed that ineligibility was a significant barrier to PFL usage. During our screening phase, women indicated they were ineligible for PFL because they were paid under the table or were self-employed. In the Rhode Island focus group discussions, some women shared that while they qualified for PFL, their partners did not because they worked across state lines. Women in New York reported what may have been the most considerable PFL eligibility challenges across the study states. These issues were attributed to New York’s requirement that individuals must remain with the same employer for 26 weeks in the PFL eligibility period to remain eligible for the program. Women who changed employers or quit their jobs prior to giving birth were not eligible for PFL benefits and were therefore not included in the study. However, for some women in the focus groups, the possibility of losing their PFL eligibility if they had left their employer was a source of stress.

While women who used their state’s program universally spoke of their gratitude for PFL, there were still barriers women who used the program had to overcome. Some women who used PFL found the payments were not sufficient to cover their expenses. For a handful of women, the administrative hurdles associated with PFL created additional stress. One participant indicated that the delay in payment was overwhelming because her husband’s income was not enough to support the family. Many women also agreed that 12 weeks, the typical amount of time off with disability leave and PFL, were not enough to eliminate or significantly reduce separation anxiety. Similarly, some women indicated that the amount of leave they took was not enough time to normalize their sleep. As a result, many felt they were not competent upon their return to work and suffered mentally and perhaps professionally.

Discussion

Focus group data revealed that the benefits of paid and unpaid leave include time to seek professional mental health support, sleep challenge mitigation, breastfeeding establishment, and greater bonding with infants. The additional benefits of paid leave include improved financial security, better work boundaries, and the facilitation of longer leave time. PRAMS data revealed that women who took paid leave were less likely to report being depressed following birth and were less likely to be identified through PRAMS as having postpartum depression. PRAMS data also demonstrated that women with paid leave were significantly more likely to take at least 12 weeks off work than those with unpaid leave.

Given the apparent benefits of PFL and the identified limitations and challenges of accessing these programs, researchers should continue to explore how the programs impact mental health outcomes and what designs work best at delivering these outcomes. Policy characteristics that may impact outcomes include:

Differences between national program and state-level programs. While state-level programs allow state governments to tailor benefits to local needs and environments, the number of women in New York who were unable to access their state program and the general confusion around eligibility requirements expressed by women in all states indicate that a national program designed with access in mind would likely increase overall PFL usage.

Wage replacement levels for lower-income women. PFL’s partial wage replacement serves as a hurdle for some. An even more progressive wage replacement rate could support lower-income women accessing this benefit and reduce financial hardship and related stress and anxiety.

Employers’ role in contributions. Policymakers should consider the tradeoffs of the New York model where employers contribute to leave payments. Under the current policy, if a woman leaves her employer, she is no longer eligible for PFL. While involving employers in either the management or funding of PFL reduces state and taxpayer burden, it may impact access to the program, especially among lower-wage earners, given they may have less job stability (Butcher & Schanzenbach, Citation2018). The bar for qualification is much lower in other states. In California, for example, people must only have been employed or actively looking for work when the family leave begins, and must have made at least $300 in the 12 months prior (State of California Employment Development Department, Citation2022). This flexibility gives women a choice to resign from their position during their pregnancy for their health or that of their baby. Several focus group participants attempted to continue working while pregnant and had to resign for health reasons (e.g. excessive manual labor or exposure to radiation).

Dissemination of program eligibility and benefits. Despite states’ efforts to adopt increasingly progressive wage replacement rates and efforts to target low-wage earners in dissemination campaigns, we found that 26 percent of PFL non-users did not know about the program, and another 15 percent did not feel they could afford to take it. Of the women who did not know about the program, 43 percent made less than $50,000 a year. This indicates that continued dissemination strategies may improve PFL access, especially among women with low wages, immigrants, and women of color, who are less likely to be aware of PFL benefits (Berger et al., Citation2005).

There were several areas for further research identified during this study. A clearer understanding of the role PFL plays in non-birth parents’ experiences after the birth of a new child would also help inform PFL policy. This study specifically examined the experiences of women who gave birth to a child, which meant that non-birth parents were excluded from the study. However, non-birth parents are equally eligible for PFL, and their experiences should also inform future policy. Individuals who were ineligible for PFL were also excluded from this study. This population would likely provide additional information about the barriers to PFL access.

Conclusion

Through focus groups we found that virtually all women who participated in this study experienced challenges with mental health during the postpartum period, whether they were able to access PFL or not. However, we also found that PFL was associated with financial peace of mind, and greater empowerment to take the full leave benefit without worrying about work repercussions. Women reported this helped them establish healthy work/home boundaries. We did not explore how employer-sponsored leave compared to state-level PFL in this regard.

We also found that longer leave time, whether paid or unpaid, may help women mitigate postpartum mental health issues by giving them more time to bond with their babies following birth. Women reported that this time eased separation anxiety and the immediate need to enroll infants in daycare. Taking leave after birth may also contribute to better mental health by allowing women time to establish breastfeeding, engage in healthy sleep habits, and seek mental health support during work hours. It’s possible that many of these benefits could be gained through longer leave time, whether it be paid or unpaid (see ). However, we identified four mechanisms through which PFL may be associated with improved mental health. These mechanisms include providing financial peace of mind, creating work-related boundaries, facilitating partner support and, most importantly, offering more time at home. Data from this study indicated that providing financial peace of mind and creating work-related boundaries may be direct benefits of PFL, while offering more time at home and facilitating partner support may be indirect benefits of PFL.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women's Health: Grant Number Task Order 18-233-SOL-00349-0002. We would like to thank Adrienne Smith with the Office on Women’s Health and the rest of the staff at OWH for their contributions to this work. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of OWH.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2012–2018 data used in this study is available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/prams/index.htm

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elizabeth Coombs

Elizabeth Coombs, MPP, is a Managing Associate at Mission Analytics Group where she directs projects, conducts quantitative and qualitative research, and provides training and technical assistance. She has been the project director for numerous complex projects within the Department of Health and Human Services, including the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), the Office on Women’s Health (OWH), and the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy (OIDP). Her areas of expertise include HIV care delivery, hepatitis C treatment access and policy, data management and reporting, paid family leave policy, maternal health, rural health, and Medicaid-funded home and community-based services (HCBS).

Nick Theobald

Nick Theobald, Ph.D, is an Owner and Managing Associate at Mission Analytics Group. He has nearly 20 years of experience producing academic and applied policy research. He currently directs the project for the California Department of Managed Health Care developing and analyzing regulatory standards for access to care measures. He also directs the data collection project for Health Equity Report on American Indians and Alaska Natives for the Office of Health Equity in the Health Resources Administration. He serves as the quantitative and task lead on several projects, including work with the California Department of Developmental Services; Health and Human Services Office on Women’s Health Paid Family Leave Project; the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Rural Community Hospital Demonstration, and the CMS Health Care Innovations Award R2 Evaluation.

Anna Allison

Anna Allison, MPH, is a Senior Analyst at Mission Analytics Group where she contributes to site visits, report production, technical assistance and other analytical support for projects related to maternal health, individuals with disabilities, mental illness, and HIV/AIDS.

Natalie Ortiz

Natalie Ortiz is an Analyst at Mission Analytics Group where she contributes to report production and other analytical support for projects related to maternal health and individuals with disabilities.

Amy Lim

Amy Lim is an Analyst at Mission Analytics Group where she contributes to report production, programing, and other analytical support for projects related to maternal health and individuals with disabilities.

Brittany Perrotte

Brittany Perrotte, MPH, is a Public Health Analyst at U.S. Health and Human Services, Office on Women’s Health. Brittany manages the technical and operational aspects of the Challenge, in addition to providing coaching support to our 10 city-based teams. Brittany’s passion for public health and health equity was originally inspired by her experience working as a public-school teacher in the city of Chicago. Prior to joining APHA, Brittany worked for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women’s Health, where she led policy initiatives to improve the health and wellbeing of women and girls. Brittany holds an MPH in Maternal and Child Health and a BA in Hispanic Languages and Literature from the George Washington University.

Adrienne Smith

Adrienne Smith, Ph.D, is the Director of the Division of Policy and Performance Management (DPPM) where she oversees activities focused on women's health policy, program evaluation, strategic planning, and performance reporting. With the OWH, Dr. Smith has been involved with initiatives primarily for minority women including the Minority Women's Health Panel of Experts, two National Minority Women's Health Summits and the Health and Wellness Grant Initiative for Women Attending Minority Institutions. She also partnered with the HHS Administration for Children and Families (ACF) Office on Trafficking in Persons to develop the SOAR (Stop. Observe. Ask. and Respond) to Human Trafficking Training for health care and social service professionals. Most notably she has established more than one hundred contracts supporting small minority, community – and faith-based organizations serving women and girls.

Pamela Winston

Pamela Winston, Ph.D is a Senior Researcher in Human Services Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where her portfolio includes work-family and other supports for low-income families. Prior to joining ASPE, she was a senior researcher at Mathematica Policy Research, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute, and a postdoctoral research fellow at Johns Hopkins University. She has a B.A. from Swarthmore College, an M.B.A. from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in political science from Johns Hopkins.

References

- Andres, E., Baird, S., Bingenheimer, J. B., & Markus, A. R. (2015). Maternity leave access and health: A systematic narrative review and conceptual framework. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(6), 1178–1192. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1905-9

- Appelbaum, E., & Milkman, R. (2011, January 11). Leaves that pay: Employer and worker experiences with paid family leave in California [Center for Economic and Policy Research]. https://cepr.net/report/leaves-that-pay/.

- Berger, L. M., Hill, J., & Waldfogel, J. (2005). Maternity leave, early maternal employment and child health and development in the US. The Economic Journal, 115(501), F29–F47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-0133.2005.00971.x

- Butcher, K., & Schanzenbach, D. (2018, July 24). Most workers in Low-wage labor market work substantial hours, in volatile jobs. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/most-workers-in-low-wage-labor-market-work-substantial-hours-in.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, August 24). Facts about nationwide breastfeeding goals. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/facts.html.

- Chatterji, P., & Frick, K.D. (2005). Does returning to work after childbirth affect breastfeeding practices? Review of Economics of the Household, 3, 315–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-005-3460-4

- Chatterji, P., & Markowitz, S. (2005). Does the length of maternity leave affect maternal health? Southern Economic Journal, 72(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.2307/20062092

- Cheng, C.-Y., Fowles, E. R., & Walker, L. O. (2006). Postpartum maternal health care in the United States: A critical review. Journal of Perinatal Education, 15(3), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1624/105812406X119002

- Doran, E. L., Bartel, A. P., Ruhm, C. J., & Waldfogel, J. (2020). California's paid family leave law improves maternal psychological health. Social Science and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113003

- Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Barnes, G. M. (1996). Work–family conflict, gender, and health-related outcomes: A study of employed parents in two community samples. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.57

- Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65

- Gavin, N. I., Gaynes, B. N., Lohr, K. N., Meltzer-Brody, S., Gartlehner, G., & Swinson, T. (2005). Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 106(5), 1071–1083. http://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db

- Gjerdingen, D. K. (1993). Changes in women’s physical health during the first postpartum year. Archives of Family Medicine, 2(3), 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1001/archfami.2.3.277

- Gjerdingen, D. K., McGovern, P. M., Chaloner, K. M., & Street, H. B. (1995). Women’s postpartum maternity benefits and work experience. Family Medicine, 27(9), 592–598. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8829985/

- Goodman, J. M., Elser, H., & Dow, W. H. (2020). Among low-income women in San Francisco, low awareness of paid parental leave benefits inhibits take-up: study examines the impact of the San Francisco paid parental leave ordinance, the first in the United States to provide parental leave with full pay. Health Affairs, 39(7), 1157–1165. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00157

- Grice, M. M., McGovern, P. M., Alexander, B. H., Ukestad, L., & Hellerstedt, W. (2011). Balancing work and family after childbirth: A longitudinal analysis. Women's Health Issues, 21(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2010.08.003

- Guendelman, S., Pearl, M., Graham, S., Hubbard, A., Hosang, N., & Kharrazi, M. (2009). Maternity leave in the ninth month of pregnancy and birth outcomes among working women. Women's Health Issues, 19(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2008.07.007

- Hofferth, S. L., & Curtin, S. C. (2006). Parental leave statutes and maternal return to work after childbirth in the United States. Work and Occupations, 33(1), 73–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888405281889

- Huang, R., & Yang, M. (2015). Paid maternity leave and breastfeeding practice before and after California’s implementation of the nation’s first paid family leave program. Economics and Human Biology, 16, 45–59. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2013.12.009

- Human Rights Watch. (2011). Failing its families: Lack of paid leave and work-family supports in the US. https://www.hrw.org/report/2011/02/23/failing-its-families/lack-paid-leave-and-work-family-supports-us.

- Hyde, J. S., Klein, M. H., Essex, M. J., & Clark, R. (1995). Maternity leave And women’s mental health. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19(2), 257–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1995.tb00291.x

- Kottwitz, A., Oppermann, A., & Spiess, C. K. (2016). Parental leave benefits and breastfeeding in Germany effects of the 2007 reform. Review of Economics of the Household, 14(4), 859–890. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-015-9299-4

- Lee, B. C., Modrek, S., White, J. S., Batra, A., Collin, D. F., & Hamad, R. (1982). The effect of California's paid family leave policy on parent health: A quasi-experimental study. Social Science and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112915

- LegiScan. (2012). California SB299 | 2011–2012 | Regular Session. LegiScan. https://legiscan.com/CA/text/SB299/id/353995.

- Mandal, B. (2018). The effect of paid leave on maternal mental health. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(10), 1470–1476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2542-x

- McGovern, P., Dowd, B., Gjerdingen, D., Dagher, R., Ukestad, L., McCaffrey, D., & Lundberg, U. (2007). Mothers’ health and work-related factors at 11 weeks postpartum. The Annals of Family Medicine, 5(6), 519–527. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.751

- Miller, L. J. (2002). Postpartum depression. JAMA, 287(6), 762. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.6.762

- Minnesota Department of Health. (2015). White paper on paid leave and health (p. 39). https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/equity/reports/2015paidleave.pdf.

- Mirkovic, K. R., Perrine, C. G., & Scanlon, K. S. (2016). Paid maternity leave and breastfeeding outcomes. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, 43(3), 233–239.

- National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care. (2006). Routine postnatal care of women and their babies. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55925/.

- New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. (2021). Division of employer accounts | Rate information, contributions, and due dates. https://www.nj.gov/labor/ea/employer-services/rate-info/.

- New York State. (2021a). New York paid family leave updates for 2021. Paid Family Leave. https://paidfamilyleave.ny.gov/2021.

- New York State. (2021b). Your rights and protections. Paid Family Leave. https://paidfamilyleave.ny.gov/protections.

- Prudential. (2021). Rhode Island Temporary Disability Insurance (TDI). https://convatecbenefits.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/RI-TDI-FAQs-2021.pdf.

- Romig, K., & Bryant, K. (2021, April 27). A national paid leave program would help workers, families. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/a-national-paid-leave-program-would-help-workers-families.

- Rossin-Slater, M., Ruhm, C., & Waldfogel, J. (2013). The effects of California’s paid family leave program on mothers’ leave-taking and subsequent labor market outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management : [The Journal of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management], 32(2), 224–245. http://doi.org/10.3386/w17715

- Rowe-Finkbeiner, K., Martin, R., Abrams, B., Zuccaro, A., & Dardari, Y. (2016). Why paid family and medical leave matters for the future of America’s families, businesses and economy. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(Suppl 1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2186-7

- Schulte, B., Durana, A., Stout, B., & Moyer, J. (2017, June 16). Paid family leave: How much time is enough? New America. http://newamerica.org/better-life-lab/reports/paid-family-leave-how-much-time-enough/.

- Slomian, J., Honvo, G., Emonts, P., Reginster, J.-Y., & Bruyère, O. (2019). Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women's Health, 15, 1745506519844044. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745506519844044

- Stamm, C., Glass, R., & Marshall, K. (2022, January 19). 2022 State paid family and medical leave contributions and benefits. Mercer. https://www.mercer.com/our-thinking/law-and-policy-group/2022-state-paid-family-and-medical-leave-contributions-and-benefits.html.

- State of California Employment Development Department. (2022). Am i eligible for paid family leave benefits? https://edd.ca.gov/en/Disability/Am_I_Eligible_for_PFL_Benefits.

- State of New Jersey. (2019, February). Leave of absense and your benefits, fact sheet #20. https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/pensions/documents/factsheets/fact20.pdf.

- The Economic Progress Institute. (2021, April). Expand access to paid family leave (TCI). https://www.economicprogressri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2021-TCI-Fact-Sheet-4-26-21-FINAL.pdf.

- The White House. (2021, April 28). FACT SHEET: The American families plan. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/04/28/fact-sheet-the-american-families-plan/.

- U.S. Department of Labor. (2022). Family and Medical Leave Act | U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmla.

- Winston, P., Coombs, E., Bennett, R., Antelo, L., Landers, P., & Abbott, M. (2019). Paid family leave: Supporting work attachment among lower income mothers, Community, Work & Family, 22(4), 478–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2019.1635436