Abstract

Vaccines represent one of the most important methods to reduce the risk of hospitalisation and mortality as a result of COVID-19. To ensure the spread and risk of the Delta variant of COVID-19 is minimised, as many people as possible nationally must be fully vaccinated. Ensuring success in reaching high rates of vaccination relies on both effective risk management and risk communication strategies. This paper evaluates vaccine rollout management and communication strategies in five European nations: France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and England within the UK, updating findings from a previous paper on the same topic from January 2021. This paper evaluates these five nations’ management and communication strategies regarding the vaccine rollout timeline and prioritisation. Further, we discuss the effectiveness and importance of vaccine or immunity passports, highlighting the importance of ensuring that the needs of minoritised groups are considered in promoting the vaccine rollout, and ensuring fairness when prioritising certain groups over others to have earlier access to any vaccine. In conclusion, recommendations for policy makers and public health communicators are put forward.

1. Introduction

The rollout and uptake of vaccines against COVID-19 is widely seen as one of the most effective methods of minimising the impact and spread of a virus that has already killed over 360,000 people across France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom (UK) alone (Ritchie et al. Citation2020). COVID-19 vaccines, including those created by Oxford-AstraZeneca and Pfizer-BioNTech are found to be between 69% and 90% effective against the development of a high viral load of COVID-19 14 days after the second dose is administered (Pouwels et al. Citation2021). As such, administering as many vaccines as possible has been a high-priority goal of all nations, including those in Europe, over the course of 2021. However, the growth of vaccine hesitancy and denial, widespread misinformation on social media and the COVID-19 infodemic have stymied efforts to establish the high rate of vaccination needed to reduce reliance on Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) to stop community spread of COVID-19 (van der Linden, Roozenbeek, and Compton Citation2020; Zarocostas Citation2020; Bartsch et al. Citation2020; Sherman et al. Citation2021).

This paper updates expectations and realities associated with the vaccine rollout risk communication and management strategies documented by Warren and Lofstedt (Citation2021a) in five European countries, namely: France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, and England within the UK. Here, we assess developments and progression of the vaccine rollout in these five nations since January 2021, focusing on two key areas: communication and management of the timeline and vaccine rollout speed, and rollout prioritisation. Further, we aim to extricate key themes from international examples that can act as potential lessons for other nations in how to achieve a more successful vaccine rollout. By assessing these nations’ vaccine rollouts, we aim to reflect on the uptake and impact of recommended measures outlined in our original paper and provide potential next steps for how governments can continue to improve the rates of vaccination uptake or overcome issues associated with the vaccine rollout.

2. Vaccine rollout timeline: communication and management

2.1. France

In France, the government originally employed a careful and measured communications strategy in the face of historic widespread vaccine hesitancy (Warren and Lofstedt Citation2021a). An October survey by Ipsos (Citation2020) found that only 54% of the French population were likely to get the vaccine, the lowest of all nations surveyed in this international global study. As such, effective communication aiming to overcome issues of complacency and promote solidarity with the positive impact of herd immunity was seen as key (Schwarzinger et al. Citation2021).

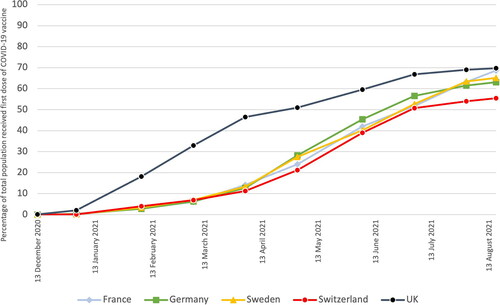

In reality, the vaccine rollout started slowly in France. As seen in , only 12% of the population had received a first dose of the vaccine by the end of March. However, between early May and mid-August the rate of first vaccinations increased dramatically, from around 23% to almost 69% of the population receiving a first dose. By mid-August, France had one of the highest rates of first vaccinations in Europe per 100 people at 69%, of which 53% had received two doses of the vaccine (Mathieu et al. Citation2021). French vaccine hesitancy has also diminished, with public willingness to take any vaccine but Oxford-AstraZeneca increasing from 42% in December 2020 to 70% in April 2021 (Odoxa Citation2021). Despite this, 16% of the public still did not intend to get vaccinated as of July 2021 (Cardot Citation2021).

Figure 1. Percentage of total population that have received at least a first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine in France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK from 13 December 2020 to 17 August 2021. Data adapted from (Ritchie et al. Citation2020) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Early on, the vaccine rollout effort was plagued by failures in procurement of the vaccine run by the European Commission, the decision the limit the use of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines, and by failures in communication. The decision to jointly procure vaccines across the European Union (EU) backfired as vaccine orders came in later than nations such as the US, UK and Israel due to a slow decision-making process (Gleißner et al. Citation2021). As such, French access to the vaccine was limited through the spring of 2021.

Further, the health authority flip-flopped on restrictions of the use of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine due to an increased risk of thrombosis, first blocking it from being given to people over 55 years (Wise Citation2021), then only giving to those over 55 from March onwards (Haute Autorité de Santé Citation2021). President Emmanuel Macron further added to the confusion by stating in January that he believed the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine to be ‘quasi-ineffective’ for those aged over 65 (France24 Citation2021). This has led to early confusion and suspicion about the vaccine. As a result, a March 2021 poll found that 61% of French respondents thought the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine was unsafe (YouGov Citation2021).

Despite the later success in the uptake of first vaccine doses in France, this cannot be attributed specifically to successful government communication efforts. If anything, commentators describe no real planned communications campaign by the French government, and a modus operandi where communications are but an addition to policy rather than being an integral part of the vaccine rollout strategy (Haudegand Citation2021). The most effective policy change to promote vaccine uptake other than opening up vaccine appointments to new priority groups has been the introduction and extension of the Pass Sanitaire, or Health Pass. The Pass Sanitaire is given to people who are fully vaccinated or have had a recent negative COVID-19 test. On 12 July, President Macron announced the requirement from the beginning of August to show a Pass Sanitaire to access cafés, restaurants, shopping centres, long distance public transport and medical establishments (Brunet Citation2021). Effectively, this expansion of the Pass Sanitaire serves to create negative consequences of not getting vaccinated, in effect creating a form of mandate in the aim of shifting individual risk-benefit calculations on getting vaccinated.

In the short-term, this policy has led to a record vaccination rate: according to Prime Minister Jean Castex, over 790,000 people were vaccinated in 24 hours on 13 July (Castex Citation2021). Indeed, the overall uptake of first doses has increased by around 15% in the last month following a lull in vaccinations (see ). However, this more coercive approach of restricting unvaccinated people’s freedoms by introducing ‘vaccine passports’ or COVID-19 immunity passes has practical and ethical considerations that must also be accounted for (Brown et al. Citation2020). These include promoting easy access to vaccination and testing and considering multiple methods of vaccine uptake incentivisation as different demographic groups will be incentivised or disincentivised in different ways (Wilf-Miron, Myers, and Saban Citation2021). If not considered, these kinds of policies can act as trust-destroying to certain groups. As Verger and Dubé (Citation2020) assert, making vaccines mandatory or using coercive mechanisms to promote uptake can increase reactance and angry responses. Despite a majority of the public supporting the introduction of the Pass Sanitaire in a July poll, some 24% of respondents were opposed (Ipsos Citation2021). France has experienced this reactance first-hand, with six consecutive weekends of protests against the Pass Sanitaire including one that attracted over 175,000 protesters from across the country on 21 August (Le Monde and AFP Citation2021).

Overall, despite overcoming a poor start, risks remain to the vaccine rollout in France that must be reinforced with ethical and practical considerations to any implementation of the Pass Sanitaire. A broader range of measures to overcome issues related to promoting perceived vaccine safety and politicisation-based vaccine hesitancy, which is widespread among the broad population who are disengaged from the political process or associate with Far-Right or Far-Left political parties, is required (Ward et al. Citation2020).

2.2. Germany

In Germany, Health Minister Jens Spahn had been optimistic about the rate of the vaccine rollout from the outset (Warren and Lofstedt Citation2021a). Unlike France, Germany’s rate of vaccine hesitancy was lower pre-vaccine rollout, recorded at 30% in October 2020 (Ipsos Citation2020). Despite experiencing similar procurement issues to France, Germany is on track to meet its target of fully vaccinating the whole population before the end of 2021. That said, only around 10% of the population had received a first dose by late March. However, in the second half of 2021 the rate of vaccination has picked up dramatically before a slight tail off into August, with 62.9% of the population receiving a first dose of the vaccine and 57% receiving both doses (Mathieu et al. Citation2021). Of the nations evaluated here, Germany is only behind the UK and France in terms of proportion of the population receiving a first dose of the vaccine as of mid-August (see ). Health Minister Spahn more recently predicted that a vaccine will be offered to every person in the country by the end of the summer, however, the rollout has not been as fast as announced (ZDF Citation2021). An August study from ARD-DeutschlandTrend found that 83% of respondents either had already or were planning to get their first dose of the vaccine, while 12% stated that they were probably or definitely not going to get vaccinated (ARD Das Erste Citation2021).

Alongside the same procurement issues France suffered, Germany also had problems rolling out the vaccine due to bureaucratic issues. Although the original procurement was organised at the national- and EU-level, the domestic vaccine rollout was decentralised and controlled by the Bundesländer, or States, as seen with other German COVID-19 NPIs, resulting in slow progress until April (Warren, Lofstedt, and Wardman Citation2021; Oltermann, Giuffrida, and Willsher Citation2021). In mid-March, an agreement was reached to allow GPs and family doctors to administer the vaccine, and Merkel adopted a new motto in the resulting press conference of ‘vaccinate, vaccinate, vaccinate’ (AFP and DPA 2021). Because of their very even geographical distribution throughout Germany, the move to allow GPs and family doctors to vaccinate has been lauded as reinvigorating the ailing vaccination effort, as seen in the vaccination rates since early April (Oltermann, Giuffrida, and Willsher Citation2021). Alongside this, fundamentally high levels of trust in GPs and family doctors across Europe mean that healthcare providers are a highly recommended entity to rely on to administer and promote acceptance of vaccines and other health interventions to hesitant groups (Warren and Lofstedt Citation2021a; Bouder et al. Citation2015; Paterson et al. Citation2016).

Despite this success, the German government vaccination communications strategy has otherwise been critiqued for using a poor choice of imagery, not offering real incentives to get vaccinated, and for exhibiting inconsistent policy and communication. Recent communications promoting vaccination have used images of clinical settings and images of vaccines in arms, which may have the reverse impact by triggering fear or other negative emotions among unvaccinated individuals due to the presence of needles (Scholz Citation2021). Fear of needles is strongly linked to reduced willingness to get vaccinated and heightened vaccine hesitancy so communicating in this way should be avoided (McLenon and Rogers Citation2019; Guidry et al. Citation2021). A recent communications campaign titled ‘Ärmel Hoch’ or ‘Sleeves up’ aims to diverge from past strategies and highlight famous celebrities who have been vaccinated with the aim of returning to normal life (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit Citation2021a).

Unlike France, incentives to get vaccinated have as yet been comparatively trivial, inconsistent and not particularly widespread despite public support for incentivisation. Conflicting responses to questions regarding government plans to vaccinate children and the impact of mask wearing have also eroded vaccine-hesitant groups’ trust in government entities (Scholz Citation2021). A recent study has found positive relationships between willingness to get vaccinated and trust in state institutions, science and media (Illner Citation2021). This highlights that reasoned transparency in communication alongside consistency and clarity are key elements to avoid long-term vaccine hesitancy and widespread vaccine refusal (Warren and Lofstedt Citation2021a; Citation2021b; Balog-Way and McComas Citation2020; Petersen et al. Citation2021).

2.3. Sweden

At the end of November 2020, Swedish state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell noted that he thought the vaccination rollout would most likely take all of 2021, as that is what the companies manufacturing the various vaccines had told the Swedish Public Health Agency (PHA) (Dagens Nyheter Citation2020). Tegnell’s rather pessimistic view was swept aside when Richard Bergström, Sweden’s lead vaccination coordinator, stated that he thought it was possible that everyone over the age of 18 would be completely vaccinated by the Midsummer holiday on 26 June, sticking to this position until late January (Söderlund and Berntsson Citation2021).

In the New Year, however, Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna announced that they had problems scaling up their factories, leading to fewer vaccines being available than previously announced. The impact was that by 10 February fewer than 430,000 had received their first vaccine dose, less than half the goal set by the PHA of 1.2 million individuals from phase 1 to have been vaccinated by end of January (Larsson Citation2021). This was further complicated by AstraZeneca announcing on 11 March that it would only be able to deliver half the promised doses to Sweden in the spring (SVT Nyheter Citation2021). Rather than 6.6 million doses, Sweden would instead receive 3.3 million. This led to several regional vaccine coordinators noting that the Midsummer goal was now unrealistic (Jacobsson Citation2021).

Like Germany and Switzerland, the responsibility of handling the vaccine roll out has been placed on Sweden’s 21 regions. They each appoint their own vaccine coordinator and they are ones who decided who should get vaccinated based on the recommendations coming from the PHA. By March this decision to decentralise the vaccine rollout process had become somewhat problematic. In many regions, local politicians, local vaccine coordinators or other senior doctors noted that they felt that the goals set by Bergström were unrealistic and needed to be re-examined as there were simply not enough vaccines available. Richard Bergström had noted on the 26 March that 5 million Swedes will be fully vaccinated by 25 June, which a spokesperson representing the Regions said was completely unrealistic (Olofsson Citation2021). Or as Gilbert Tribo, the Liberal head of public health Skåne, noted:

‘We don’t feel listened to, and that is not just my opinion. It has happened a number of times that we find out late on Friday afternoon that deliveries of the vaccine will be halved by Monday. That causes extreme uncertainty and extreme frustration.’ (Carlsson Citation2021).

On 1 April, at a press conference led by Minister for Health Lena Hallegren, the end goal of the Swedish rollout strategy was changed. The goal was altered from the aim that everyone who wants to will be fully vaccinated by 30 June, to the goal of all adults who want the vaccine would receive one dose by the 15 August and that everyone over the age of 65 would have received one dose by 16 May (Emanuelsson and Stjerberg Citation2021). This goal was further changed a few more times, including on the 24 June, when the PHA announced that everyone who wants to get a first dose will be able to do so by 19 September (Folkhälsomyndigheten Citation2021c).

The PHA also changed the timeframe between first and second doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines. In March, when the PHA was very concerned about people not getting their first vaccine, and as such the timings between doses were initially increased to 6 weeks and then 7 weeks in May (Sinclair Citation2021). Yet at the end of July, when most of Swedes had left the city centres for holidays and demand for the vaccine had reduced, the interval between the two doses was decreased from 7 weeks to 4 weeks (Gestblom Citation2021).

By 3 September, 82.3% of all adults in Sweden had received a first dose while 71.5% had received a second dose (Mathieu et al. Citation2021). Among teenagers born between 2003 and 2005, 56.4% had received their first dose of the vaccine while 7.1% had received both doses (Folkhälsomyndigheten Citation2021e). That said, there are still large regional differences in public vaccine uptake. Rosengård, Malmo, for example, has the lowest uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine in Sweden with only 43.7% of the local population having taken their first dose by 1 September (Laurell Citation2021). As seen in the UK, foreign-born individuals are less likely to have received the vaccine (Folkhälsomyndigheten Citation2021b). As such, the local Muslim community in Malmö wanted to offer vaccines in their mosque at Friday prayers to overcome lower minority ethic vaccine uptake, however, received no response from the Skåne region’s government (Laurell Citation2021). Likewise in the Stockholm region, in the wealthy area of Taby and Vaxholm, 75% of the inhabitants have been fully vaccinated, whereas in the poorer areas with a greater proportion of immigrants such as Rinkeby-Kista only 44% have been fully vaccinated (Dagens Nyheter Citation2021). To address this issue, local health officials are now using COVID-19 vaccination buses and pop-up tents to ensure that a greater percentage of foreign-born individuals get vaccinated (Fredling Citation2021).

Over time, Swedes have become increasingly positive about taking a COVID-19 vaccine. In November 2020 a Novus survey showed that 26% of the population would not get vaccinated against COVID-19 (Stiernstedt, Jakobsson, and Kaun Citation2020). In June 2021 the PHA did a survey and found that 69% said they would definitely take the vaccine while 18% noted that they probably would. Only 6% said they would not take the vaccine while 7% remained undecided (Folkhälsomyndigheten Citation2021d).

2.4. Switzerland

Switzerland’s original communication on the vaccine rollout timeline was much more measured than France and Germany, announcing that there was some uncertainty in the speed of the rollout in December 2020 (RTS Citation2020a, Citation2020b). In January, statements from the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) had been more optimistic, with the nation outlining their aim to vaccinate the entire willing population by the summer (Davis Plüss, Turuban, and Hunt Citation2021). However, only 49% of Swiss respondents were willing to get vaccinated in October 2020 (Sotomo Citation2020). In addition, Switzerland has relied on its own medical regulatory authority Swissmedic to approve vaccines over the EU-based European Medicines Agency. This means that the Swiss vaccine rollout is working on a different timeline and approval process to France, Germany and Sweden: Swissmedic approved the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine on 19 December, the Moderna vaccine on 12 January and the Janssen vaccine on 22 March. However, Swissmedic rejected the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine for approval despite the Swiss authorities having ordered 5.3 million doses (RTS Citation2021).

Like all countries discussed thus far, the Swiss vaccine rollout also started slowly, with 10% of the population receiving a first dose by the end of March (see ). Since early April this has increased dramatically, rising from 11% receiving their first dose of the vaccine to 49% in late June. Since late June, however, the rate of first vaccination uptake has slowed somewhat: only 6% of the population received their first dose of the vaccine between late June and mid-August. As of late August, 55.4% of the Swiss population had received their first dose, and 50% received both doses of the vaccine (Mathieu et al. Citation2021). A recent RTS report found that, overall, only 60% may get fully vaccinated. This is far below the desired target of 80% set by Health Minister Alain Berset and also presented wide regional disparities in uptake (Renfer Citation2021). A survey from July also found that 25% of respondents had no intention of getting vaccinated, while a further 12% stated that they would rather wait to get vaccinated at this time (Sotomo Citation2021). Counterintuitively, public trust in the government has increased since failings from the winter months have been resolved (see Warren, Lofstedt, and Wardman Citation2021). Of the five nations evaluated in this article, Switzerland has the lowest rate of vaccine uptake.

Switzerland’s vaccine communications strategy has used some recommended elements from risk communicators: a solidarity-based strategy was launched by the FOPH in May 2021 to promote vaccine uptake (FOPH Citation2021). This approach is recommended when aiming to promote altruistic public actions as seen in the case of getting a vaccine as vaccines offer protections to both the individual and others throughout the population (Bierhoff and Küpper Citation1999; Warren and Lofstedt Citation2021b; Porat et al. Citation2020; Rieger Citation2020). However, this solidarity campaign has not seemed to be as successful as it was expected to be (Logean Citation2021). Despite this new solidarity campaign, an information campaign has instead formed an overriding backbone of the FOPH’s vaccination communication efforts (Wong Sak Hoi Citation2021). As outlined consistently over the last 20 years of risk communication research, top-down information-based efforts based on the paradigm of the knowledge-deficit model to improve public decision-making is insufficient at best, and flawed at worst (Burgess, Harrison, and Filius Citation1998; Owens Citation2000; Simis et al. Citation2016).

Further, despite Switzerland launching a COVID-19 vaccine certificate in June 2021, the certificate has, until recently, been optional and not enforced by many businesses, much to the disappointment of Health Minister Berset (SWI swissinfo.ch Citation2021). This weak application of NPIs follows a similar approach to enforcement of COVID-19 rules seen during the winter lockdown (Warren, Lofstedt, and Wardman Citation2021). The Swiss Federal Council announced a widening of the COVID-19 certificate’s use and requirement from 13 September, with its use now mandatory in restaurants, leisure and cultural buildings until January 2022 (Schäfer and Forster Citation2021). This decision was made in the aim of reducing rapidly increasing rates of hospitalisation as a result of COVID-19, rather than to exclusively increase vaccine uptake.

2.5. England within the United Kingdom

Originally, the UK government was very optimistic about the rate at which the vaccine would be rolled out in England but gave mixed messages in the winter of 2020 as to how soon restrictions would be lifted as a result of a successful vaccine rollout campaign (The Guardian Citation2020; BBC News Citation2020; Warren and Lofstedt Citation2021a). The UK has historically experienced substantial vaccine hesitancy and denial, with the 1998 MMR vaccine scandal only being overcome with serious public engagement in the mid-2010s (Larson et al. Citation2015). As such, only 37% of respondents to a November 2020 poll stated they would definitely take a COVID-19 vaccine (Ipsos MORI Citation2020). The UK was the first nation globally to approve the use of a vaccine against COVID-19 that had been tested in clinical trials (Ledford, Cyranoski, and van Noorden Citation2020).

Contrary to all other nations examined, the UK’s vaccine rollout commenced very quickly. The proportion of the population who had received a first dose of the vaccine rose from 3% on 3 January to 41% on 21 March. Following this fast deployment, the rate of vaccination slowed somewhat between late March and late June, increasing to 65.5% receiving at least one dose of the vaccine (see ). Since then, the rate of vaccination has slowed considerably: between late June and mid-August the proportion of the total population that has received a first dose of the vaccine increased by around only 4% to 69.8% (Mathieu et al. Citation2021). Overall, 88.4% of the population aged 16 or over has received at least one dose of the vaccine, and 78.7% has received both doses by 1 September (Public Health England Citation2021). This represents the most successful vaccine rollout of the five nations examined here as a proportion of the population until 1 September.

In broad terms, the successful and fast start to the vaccine campaign for first doses came down to two main reasons: the comparatively greater availability of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines for older individuals in the UK, and the decision taken by the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) in December 2020 to prioritise first doses and lengthen the time between first and second doses of all vaccines to around 12 weeks rather than three employed by other nations (Department of Health and Social Care Citation2020; Tregoning et al. Citation2021). The rollout has also been singularly administered by the National Health Service (NHS), which is one of the most widely trusted institutions in the UK and experiences comparatively high levels of public support (van der Schee et al. Citation2007). As such, using a trusted organisation in this way over more privatised means has been effective in promoting higher levels of uptake (Neville and Warrell Citation2021). The NHS’s successful track record on the rollout of the annual flu vaccine also put it in good stead to ensure consistent and effective delivery of vaccine doses across the country (Hui Citation2021). Furthermore, vaccine delivery across a wide range of locations and types of venues including GP and family doctor surgeries, cultural and sports venues catered to multiple different groups and has been very effective, in line with past expert recommendations (Anderson and Thornley Citation2014; Warren and Lofstedt Citation2021a).

Additionally, a communications strategy in England which showed images of key politicians and medical advisors receiving, and in the case of England’s deputy chief medical officer Jonathan Van-Tam administering, the vaccine has highlighted the importance of leading by example in general to promote NPIs an in specific on public vaccine uptake (BBC News Citation2021a; van Bavel et al. Citation2020). The consistent news of celebrities and public figures such as Elton John, Michael Caine and the Royal Family getting vaccinated have also been used to promote the vaccine to multiple groups, including vaccine sceptics (Campbell Citation2020; NHS England Citation2021). This approach has since been taken up as part of the German health authorities’ communications efforts (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit Citation2021a).

Despite the widespread success of the vaccine rollout, there is concern at the comparatively lower rate of vaccine uptake among younger age groups and the slowed rate of vaccination overall (Rigby Citation2021; Henley Citation2021). Among younger age groups this is not necessarily surprising: recent studies have found that these groups are more vaccine hesitant and less willing to get vaccinated than older age groups in the UK (Lazarus et al. Citation2020; Robertson et al. Citation2021). As such, recent communications campaigns have focused more specifically on the 18–29 age group, including one focused on highlighting that young people could miss out on nightlife and ‘good times’ unless they get vaccinated which includes pop-up vaccination centres at nightclubs (Mehta Citation2021). However, since 19 July all lockdown restrictions have been lifted in England and no incentive currently exists to promote vaccine uptake to younger age groups that involves restricting freedoms unless specified by businesses. There are new plans to introduce a vaccine or immunity passport for entry into nightclubs and other large indoor venues as a method of promoting vaccine uptake, although pubs and bars will not be included (Stewart Citation2021). Although the introduction of an immunity passport has been found to be effective in France, the lack of breadth of the planned UK version suggests that this will not be particularly effective and may be counterproductive (Grover, Stewart, and Quinn Citation2021). Recent inconsistent messaging on this issue between the government and Health Minister Sajid Javid is unlikely to promote confidence in the government’s approach and support for vaccine or immunity passes (see Jackson Citation2021).

Vaccine uptake among minority ethnic groups has been documented as lower than average, in line with expectations from studies conducted pre-rollout (Kadambari and Vanderslott Citation2021; Woolf et al. Citation2021). Alongside well-documented historical barriers to minoritised ethnic groups engaging with health systems globally (Scheppers et al. Citation2006), barriers to COVID-19 uptake among minority ethnic groups in the UK include being historically marginalised through continuing systemic discrimination and racism in the healthcare sector, prior improper research on minority ethnic groups, safety fears due to perceived lack of testing and the spread of misinformation (Razai et al. Citation2021; Lintern Citation2021; Reverby Citation2011). The UK government must therefore engage specifically with these groups in England to build trust, engaging in two-way communication and providing tailor-made material suitable to these groups’ contexts and language needs (Kadambari and Vanderslott Citation2021).

The government has attempted to engage with these groups, including a minority ethnic celebrity-led TV campaign urging those eligible to get vaccinated in February 2021 (Mohdin Citation2021) and the aforementioned introduction of vaccine or immunity passports. However, the latter coercion strategy is not likely to be successful based on findings from a recent study by Citationde Figueiredo, Larson, and Reicher (Citation2021). As such, further tailor-made multidirectional engagement with minority ethnic groups is needed (Paul, Steptoe, and Fancourt Citation2021), including language-based tailoring, trust-building conversations with communities and increased ease of access to vaccination (Hoppe and Eckert Citation2011; Kadambari and Vanderslott Citation2021).

3. Vaccine prioritisation strategy: communication and management

3.1. France

In France, the original vaccine prioritisation strategy outlined in November 2020 highlighted five key groups, mainly based around age but also allowing certain key workers to receive the vaccination early (Haute Autorité de Santé Citation2020; see Warren and Lofstedt Citation2021a). In the eventual rollout, three main phases prioritised these groups in order: (1) from 27 December 2020 onwards, Phase 1 prioritised ‘the highest priority audiences’ including nursing home residents and staff over 50, caregivers and firefighters from 5 January 2021; (2) from 18 January Phase 2 focused on ‘high risk groups’, including over individuals over 75 years not in care homes, and in late February and March vaccination bookings were opened to 65-74 year olds and those over 50 with comorbidities; (3) from May, Phase 3 included those aged 18-49 with comorbidities, the general population aged 50-64 and essential workers (Direction de l’information légale et administrative (Premier ministre)) Citation2021). Restrictions on ability to book a vaccine were fully lifted on 31 May, two weeks earlier than expected, allowing all individuals over 18 to be vaccinated (Citationle Figaro Citation2021). The French government has broadly followed the prioritisation strategy outlined in November 2020, and the approach to include health personnel alongside those with high-risk comorbidities and older individuals was broadly in line with public prioritisation beliefs in May 2021 (Cevipof Citation2021).

3.2. Germany

The German prioritisation strategy largely followed the recommendations set out by STIKO and the Robert Koch Institut (RKI) (2020) in early November. The prioritisation dates, however, were set by individual States. The priority groups were split into three: (1) Group 1, those with ‘the highest priority’ included individuals aged over 80, vaccinators, carers, and medical staff in high-risk areas; (2) from March Group 2, those with ‘high priority’ included those aged over 70, individuals with highly relevant health conditions, those working in public services, childcare workers and those working with the elderly were offered the vaccine; (3) from late April Group 3, those with ‘heightened priority’ including those aged over 60, those with relevant but not severe health conditions and their close contacts, key workers such as food retail workers, and those at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 were offered a first dose of the vaccine (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit Citation2021b, Citation2021c). Since 7 June, the vaccine prioritisation order has been lifted nationwide and all adults have since been eligible to receive a vaccine (Bundesregierung Deutschland Citation2021).

The approach taken by the government is somewhat in contrast to public opinion: while the government prioritised those at highest risk, a nationally representative study by Sprengholz et al. (Citation2021) finds that the public would have preferred a strategy prioritising staff working in the medical field and carers for elderly individuals. Despite staying broadly in line with the prioritisation groups outlined by STIKO in December, the German prioritisation strategy has suffered due to the decentralised State-led rollout of the vaccine that has led to inconsistencies in prioritisation timings and indeed varying eligibility between States. For example, in late January Bavaria began vaccinating trainee doctors in cities with many clinics while seniors were not able to book appointments (Mehr Citation2021). The opening up of availability to risk groups 2 and 3 has also been occurring at different times in different States (das Erste Citation2021), highlighting inconsistency and risking confusion and diminishing trust in the vaccine rollout as seen in Bavaria (Mehr Citation2021).

Alongside group prioritisation, certain States such as Berlin allowed individuals to choose which brand of vaccine they preferred to receive in Winter 2020–21 (Kinkartz Citation2021). This approach was deemed in error by State Health Minister Dilek Kalayci after a large amount of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine doses were left unadministered (Gallersdörfer Citation2021). This issue has continued in the rollout of second doses in Rheinland-Palatinate among other states, where individuals have been able to decide not to have the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine for their second dose (SWR Citation2021).

3.3. Sweden

In terms of vaccine prioritisation, the rollout in Sweden had 4 phases: (1) Phase 1 included residents in old people’s homes, people in need of home help, care and health staff associated with old people homes and home help, and close household contacts; (2) Phase 2 included those aged 65 or older, individuals in certain risk groups such as those on dialysis and people with new organ transplants, close household contacts of these people, and individuals working in the public health sector; (3) Phase 3 included 60-64 year olds, those aged 18-59 with certain medical risks such as diabetes or Downs syndrome and individuals who have difficulties in following the Agencies recommendations; (4) Phase 4 consisted of all those aged 18-59 (Folkhälsomyndigheten Citation2021a). The regions themselves can decide who should be first vaccinated in Phase 4. Phase 4 equates to around 4 million people (Johansson Citation2021).

In reality, the regions themselves prioritised different groups over others even before Phase 4. For example, in some cases nurses and doctors were prioritised before over 65-year-olds (Kudo Citation2021). In addition, even when Phase 4 was announced, most regions maintained age brackets early on. In other words, once those pertaining to Phase 3 of the vaccine prioritisation were vaccinated, the regions began Phase 4 with older age groups starting with those aged 55 and above, and then 50 and above, progressively working through age groups from oldest to youngest (see MSB Citation2021). By early July, however, when there was no shortage of vaccines, most regions such as Gotland opened the booking systems to everyone over the age of 18 (see Region Gotland Citation2021). Disparities have also developed on vaccination priorities between regional health authorities. By the end of March, it became clear the regions did not necessarily follow the recommendations set by the PHA. This is best witnessed by the fact that only 17% of the hospital staff had received their first dose of the vaccine in Dalarna compared to 64% in Kalmar (Kudo Citation2021). As Tegnell noted:

‘The regions are independent and take their own decisions. We can’t tell them what to do but we give them recommendations. It is as clear as it could be. Then if one is working in different ways in the various regions that happens all the time in Sweden.’ (Kudo Citation2021).

3.4. Switzerland

Like Germany, Switzerland’s vaccine rollout has been decided to a great extent on a Cantonal level (Davis Plüss, Turuban, and Hunt Citation2021). The Swiss Federal Commission for Vaccinations had originally decided in December that those with relevant comorbidities, those close to those with comorbidities, and workers in the health sector would be prioritised (24 Heures Citation2020). In actuality, Switzerland has operated a system of Target Groups, although the criteria could be changed by individual Cantons (see Bundesamt für Gesundheit, Citation2021b). These groups, in order of priority, include: (1) Group 1, comprising of people at risk aged 16 or over; (2) Group 2, including health workers that come into contact with patients or carers of people at risk; (3) Group 3, composed of close contacts to vulnerable people; (4) Group 4, those aged over 16 in community facilities with those of varying age groups at higher risk of infection and transmission; (5) Group 5, all individuals aged between 16 and 64; (6) Group 6, including those aged 12 to 15 (Bundesamt für Gesundheit Citation2021a).

Switzerland opened up the vaccine to individuals in Group 5, all adults aged over 16, in May and to those aged 12 to 15 on 4 June (Bundesamt für Gesundheit (BAG) and Eidgenössische Kommission für Impffragen (EKIF) Citation2021). However, issues with the broadness of the original risk groups have meant large amounts of the population were eligible earlier on, despite reduced amounts of vaccine, creating difficulty and panic to book appointments that were hard to find and in short supply (Davis Plüss, Turuban, and Hunt Citation2021). As such, an approach that was more specific and was therefore more forgiving to the situation Switzerland was in, of a low level of vaccines in spring 2021, would have been more appropriate.

Similar to Germany, Switzerland also has regional and Cantonal disparities (Davis Plüss, Turuban, and Hunt Citation2021; Hoffmeyer Citation2021). In some Cantons such as Zurich, the vaccine appointments system has run on a ‘first come, first served’ basis over any kind of random allocation which has been deemed unfair, favouring those who use the internet and have more flexible work or school situations (SRF Citation2021). Although there is some more positive belief in the Federal Council among Swiss people in a recent poll, vaccination intentions remain starkly divided between age groups: 52.5% of 16 to 25-year-olds have either been vaccinated once or twice, or plan to get vaccinated, compared to 88% of over 75-year-olds (Kissling Citation2021).

3.5. England within the United Kingdom

A very structured 9-group plan to vaccinate the most vulnerable was outlined by the JCVI in September 2020 and has been adopted by the UK government in England (JCVI Citation2020). After successively opening up each of these groups as Phase 1 of the vaccine rollout, Phase 2 continued to move through lower age groups, split into Group 10 (all adults aged 40 to 49), Group 11 (individuals aged 30 to 39) and Group 12 (all those aged 18 to 29) (JCVI Citation2021). This highly age-based prioritisation strategy has come under criticism for not offering added priority to those deemed in high-risk or essential roles, such as teachers, bus drivers and police officers as seen in other nations such as France and Germany (BBC News Citation2021b). A recent study by Liu et al. (Citation2021) found that a very incremental age-based strategy is not necessarily as effective as broader age group prioritisation, especially when the rollout is fast, contrary to the approach in England.

Overall, prioritisation strategies have broadly been in line with expert recommendations and original plans set in late 2020. This is important to ensure perceived consistency and fairness. However, certain nation-specific issues, including inconsistencies surrounding decentralised state rollouts in Germany and Switzerland and debates around the need for certain professions or characteristics to be prioritised in the UK highlight need for reasoned transparency and fairness in any vaccine rollout.

4. Vaccine rollout timeline and prioritisation: evaluation

In the early stages of the vaccine rollout, the timeline was dictated by the speed by which vaccine doses could be procured in all five countries. Several nations had been cautious in communications about the potential speed of their vaccine rollout in late 2020, which followed an approach recommended by experts (Warren and Lofstedt Citation2021a; Hrynick, Ripoll, and Schmidt-Sane Citation2020; Peiris and Leung Citation2020). However, this has broadly not had much of an impact in mitigating reduced public support for government in the wake of perceived failures in spring 2021.

In the later stages of the vaccine rollout, there has been a shift in the strategy of promoting vaccine uptake, from ensuring enough doses are available to persuading the largest number of individuals possible to decide to take the vaccine (DeRoo, Pudalov, and Fu Citation2020; French et al. Citation2020). This change towards communication and management techniques for incentivising and motivating individuals to get vaccinated has led to multiple methods across the five countries analysed, including more recently the idea of a vaccine or immunity passport in domestic settings. The nature, breadth, and enforceability of such a pass varies between the countries analysed, with France having the strictest and broadest requirements, Switzerland using until recently a broad yet unenforceable pass, and the UK planning an internal pass focused on large-scale events rather than limiting day-to-day activity. This form of incentive puts those refusing a vaccine at a disadvantage in order to motivate them to change their mind, and some authors claim this can be effective to increase uptake (Jecker Citation2021; Brown et al. Citation2021).

However, findings from multiple studies highlight disparities between populations in different nations’ willingness to accept the introduction of a vaccine or immunity passport and a minority stating strong opposition in the case of the UK (Kowalewski et al. Citation2021; Nehme et al. Citation2021; Lewandowsky et al. Citation2021; Citationde Figueiredo, Larson, and Reicher Citation2021). There are also different national public expectations regarding their use and application between nations, such as a preference for paper-based documents in Germany or an expectation that certification would not be needed for social events in Switzerland (Kowalewski et al. Citation2021; Nehme et al. Citation2021). If a vaccine or immunity passport is inappropriately introduced or enforced in the national and local context, this could negatively impact on public trust especially among already mistrustful groups (Drury et al. Citation2021). Because there is a strong relationship between higher levels of public trust in authorities and vaccine acceptance (Lazarus et al. Citation2021), any trust-destroying incident could exacerbate vaccine hesitancy and denial (Lindholt et al. Citation2021). As such, care must be taken to ensure the appropriate use and applicability of any vaccine or immunity passport. Overall, incentivisation methods must be measured, including positive incentives alongside any potential penalties for non-vaccinated individuals (Saban et al. Citation2021).

Certain nations, such as the UK and Sweden, have attempted to address disparities in vaccine uptake between various demographic groups. These have tended to involve top-down messaging campaigns led by trusted community leaders (see Mohdin Citation2021). Although this technique may be effective, ensuring that more participatory methods of communication are key to promoting wider public engagement and eventual vaccine uptake (Hoppe and Eckert Citation2011; Kadambari and Vanderslott Citation2021; Paul, Steptoe, and Fancourt Citation2021). Alongside engagement to persuade groups to overcome vaccine hesitancy, communication must serve as part of a wider strategy to increase accessibility to vaccines especially among minoritised groups (Thomas, Osterholm, and Stauffer Citation2021). Examples of this include pop-up vaccination centres in Sweden and the UK (Mehta Citation2021; Fredling Citation2021). However, this strategy to ensure equitable uptake across demographic groups should further include promotion of accessibility including protected paid time off to get vaccinated or recover from potential side-effects and producing materials relevant to the language or demographic group in question across all European nations examined.

All nations studied in this article have generally given vaccination priority to high-risk groups, those at highest risk of contracting COVID-19, and to some extent those working in certain choice professions. These strategic decisions have largely been based on expert recommendations, which has avoided any egregious cases of perceived unfairness apart from in isolated cases (see Mehr Citation2021). Ensuring fair prioritisation, despite a decentralised system such as in Germany or Switzerland, is also key. Disparities in vaccine prioritisation between communities and regions risk the creation of perceived unfairness, therefore equitable national prioritisation strategy with a consistent application across local and regional administrations is vital (Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2020). This approach is recommended, as fairness is one of the key drivers of public trust in government risk management strategies (Lofstedt Citation2005). Public trust in scientists and public health authorities has been found to be one of the strongest drivers of vaccine acceptance, and so maintaining it is vital for any successful vaccine rollout (Lindholt et al. Citation2021).

5. Recommendations

Based on the analysis above, we recommend the following actions to governments and health authorities with regards to future vaccine rollout management and communication strategies:

Ensure that a broad range of vaccination locations and trusted vaccinators are available to those willing to be vaccinated, from more habitual locations such as family doctors’ offices to sports stadia;

Cautious and realistic communication of the vaccine rollout timeline is important to avoid perceived failures;

Communicators should exercise reasoned transparency to the public on issues related to vaccine safety, the timeline of the rollout and prioritisation strategies;

Flexibility in promoting the vaccine to groups with lower vaccination rates and improved accessibility are key. This can involve using mobile vaccination units, pop-up centres, longer opening times and ensuring paid leave from work;

Among groups with lower vaccination rates such as minoritised groups, two-way deliberative engagement as a trust-building exercise can be a key part of promoting greater vaccine uptake;

Ensure communication efforts are accessible to all, not only in terms of content, messenger, and delivery process, but also accounting for language and social context;

Governments should consider a range of incentives and penalties to promote vaccination rates that are balanced and present consequences for vaccine refusal. However, vaccines should not be mandated amongst the general public;

Considered use and application of vaccine or immunity passports based on the national context is vital to avoid trust-destroying incidents;

Prioritisation of specific groups to be vaccinated ahead of others must follow expert recommendations and avoid local disparities to overcome risks of unfairness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- AFP, and DPA. 2021. “Germany: Merkel, State Leaders Agree on Strategy to Jump-Start Vaccinations.” Deutsche Welle, March 19. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-merkel-state-leaders-agree-on-strategy-to-jump-start-vaccinations/a-56931483.

- Anderson, Claire, and Tracey Thornley. 2014. ““It’s Easier in Pharmacy”: Why Some Patients Prefer to Pay for Flu Jabs Rather Than Use the National Health Service.” BMC Health Services Research 14 (1): 35–36. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-35.

- ARD Das Erste. 2021. “ARD-DeutschlandTrend: Impfpflicht Umstritten.” ARD, August 5. https://www.presseportal.de/pm/6694/4986955.

- Balog-Way, Dominic H. P., and Katherine A. McComas. 2020. “COVID-19: Reflections on Trust, Tradeoffs, and Preparedness.” Journal of Risk Research 23 (7–8): 838–811. doi:10.1080/13669877.2020.1758192.

- Bartsch, Sarah M., Kelly J. O’Shea, Marie C. Ferguson, Maria Elena Bottazzi, Patrick T. Wedlock, Ulrich Strych, James A. McKinnell, et al. 2020. “Vaccine Efficacy Needed for a COVID-19 Coronavirus Vaccine to Prevent or Stop an Epidemic as the Sole Intervention.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 59 (4): 493–503. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.011.

- BBC News. 2020. “Hancock ‘thrilled’ with Covid Vaccine Approval.” BBC.

- BBC News. 2021a. “Covid: Jonathan Van-Tam Gives out Vaccination Jabs.” BBC News, January 13. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-nottinghamshire-55653966.

- BBC News. 2021b. “Age Not Job Prioritised in Second Phase of Covid Jab Rollout.” BBC, February 26. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-56208674.

- Bierhoff, Hans W., and Beate Küpper. 1999. “Social Psychology of Solidarity.” In Solidarity. Philosophical Studies in Contemporary Culture. 5th ed., edited by Kurt Bayertz, 133–156. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-015-9245-1_7.

- Bouder, Frederic, Dominic Way, Ragnar Löfstedt, and Darrick Evensen. 2015. “Transparency in Europe: A Quantitative Study.” Risk Analysis : An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis 35 (7): 1210–1229. doi:10.1111/risa.12386.

- Brown, Rebecca C. H., Dominic Kelly, Dominic Wilkinson, and Julian Savulescu. 2021. “The Scientific and Ethical Feasibility of Immunity Passports.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 21 (3): e58–e63. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30766-0.

- Brown, Rebecca C. H., Julian Savulescu, Bridget Williams, and Dominic Wilkinson. 2020. “Passport to Freedom? Immunity Passports for COVID-19.” Journal of Medical Ethics 46 (10): 652–659. doi:10.1136/medethics-2020-106365.

- Brunet, Romain. 2021. “Vaccination Obligatoire, Pass Sanitaire, Tests PCR : Emmanuel Macron Met Les Non-Vaccinés Sous Pression.” France24, July 12. https://www.france24.com/fr/france/20210712-en-direct-vaccination-obligatoire-et-pass-sanitaire-%C3%A9tendu-au-menu-de-l-allocution-d-emmanuel-macron.

- Bundesamt für Gesundheit (BAG), and Eidgenössische Kommission für Impffragen (EKIF). 2021. “Covid-19-Impfstrategie (Stand 22.06.2021).” Bern.

- Bundesamt für Gesundheit. 2021a. “Coronavirus: Covid-19-Impfung.” BAG, August 31. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/krankheiten/ausbrueche-epidemien-pandemien/aktuelle-ausbrueche-epidemien/novel-cov/information-fuer-die-aerzteschaft/covid-19-impfung.html.

- Bundesamt für Gesundheit. 2021b. “Coronavirus: Impfung.” BAG, September 3. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/krankheiten/ausbrueche-epidemien-pandemien/aktuelle-ausbrueche-epidemien/novel-cov/impfen.html.

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. 2021a. “Deutschland Krempelt Die #ÄrmelHoch | Zusammen Gegen Corona.” Bundesrepublik Deutschland. https://www.zusammengegencorona.de/mitmachen/deutschland-krempelt-die-aermel-hoch/.

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. 2021b. “Verordnung Zum Anspruch Auf Schutzimpfung Gegen Das Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (Coronavirus-Impfverordnung – CoronaImpfV) Vom 10. März 2021.” Berlin. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/C/Coronavirus/Verordnungen/Corona-ImpfV_BAnz_AT_11.03.2021_V1.pdf.

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. 2021c. “Impfung Für Risikopatientinnen Und -Patienten.” BfG. August 19. https://www.zusammengegencorona.de/impfen/basiswissen-zum-impfen/impfung-fuer-risikopatientinnen-und-patienten-wer-wird-wann-geschuetzt/.

- Bundesregierung Deutschland. 2021. “Impf-Priorisierung Für Corona-Impfung Entfällt.” Bundesregierung Deutschland. June 7. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/coronavirus/corona-impfung-priorisierung-entfaellt-1914756.

- Burgess, J., C. M. Harrison, and P. Filius. 1998. “Environmental Communication and the Cultural Politics of Environmental Citizenship.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 30 (8): 1445–1460. doi:10.1068/a301445.

- Campbell, Denis. 2020. “NHS to Enlist ‘sensible’ Celebrities to Persuade People to Take Coronavirus Vaccine.” The Guardian, November 29. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/nov/29/nhs-enlist-sensible-celebrities-coronavirus-vaccine-take-up.

- Cardot, Marine. 2021. “Covid: Ces 16% de Français Qui Ne Veulent Pas Des Vaccins.” Les Echos, July 23. https://www.lesechos.fr/economie-france/social/covid-ces-16-de-francais-qui-ne-veulent-pas-des-vaccins-1334302.

- Carlsson, D. 2021. “Skånes Utspel: ‘Alla Har Fatt Vaccin Forst I Oktober.” Kvallsposten, March 22.

- Castex, Jean. 2021. “Jean Castex on Twitter: "Vous Êtes 792 339 à Avoir Reçu Une Injection Ce Jour : Record Battu. Cet Élan Doit Encore s’amplifier et Se Poursuivre Dans Les Semaines Qui Viennent. Faites-Vous Vacciner!” Twitter, July 13. https://twitter.com/JeanCASTEX/status/1414992143836487684.

- Cevipof. 2021. En Qu(o)i Les Français Ont-Ils Confiance Aujourd’hui ? - Le Baromètre de La Confiance Politique - Vague 12b, Mai 2021. Paris. https://www.sciencespo.fr/cevipof/sites/sciencespo.fr.cevipof/files/Barome%CC%80tre%20Vague%2012%20bis%201-%20VERSION%20FINALE%20(pour%20mise%20sur%20le%20site%20CEVIPOF).pdf.

- Dagens Nyheter. 2020. “Tegnell: Osäkert När vi Har Vaccin till Alla Svenskar.” Dagens Nyheter, December 1. https://www.dn.se/sverige/tegnell-osakert-nar-vi-har-vaccin-till-alla-svenskar/.

- Dagens Nyheter. 2021. “Vaccinskillnaden Fortsätter Att Öka i Stockholm.” DN, September 1. https://www.dn.se/sthlm/vaccinskillnaden-fortsatter-att-oka-i-stockholm/.

- Davis Plüss, Jessica, Pauline Turuban, and Julie Hunt. 2021. “Switzerland’s Stop-and-Go March to Vaccinate Everyone by the Summer.” SWI Swissinfo.Ch, January 19. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/switzerland-s-stop-and-go-march-to-vaccinate-everyone-by-the-summer/46297784.

- de Figueiredo, Alexandre, Heidi J., Larson, and Stephen Reicher. 2021. “The Potential Impact of Vaccine Passports on Inclination to Accept COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United Kingdom: Evidence from a Large Cross-Sectional Survey and Modelling Study.” MedRxiv, June, 2021.05.31.21258122. doi:10.1101/2021.05.31.21258122.

- Department of Health and Social Care. 2020. Statement from the UK Chief Medical Officers on the Prioritisation of First Doses of COVID-19 Vaccines. London. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/statement-from-the-uk-chief-medical-officers-on-the-prioritisation-of-first-doses-of-covid-19-vaccines.

- DeRoo, Sarah Schaffer, Natalie J. Pudalov, and Linda Y. Fu. 2020. “Planning for a COVID-19 Vaccination Program.” JAMA 323 (24): 2458–2459. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8711.

- Direction de l’information légale et administrative (Premier ministre). 2021. “Épidémie de Coronavirus (Covid-19) -Vaccination Contre Le Covid-19: Quel Calendrier?” République Française. July 13. https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/actualites/A14557.

- Drury, John, Guanlan Mao, Ann John, Atiya Kamal, G. James Rubin, Clifford Stott, Tushna Vandrevala, and Theresa M. Marteau. 2021. “Behavioural Responses to Covid-19 Health Certification: A Rapid Review.” BMC Public Health 21 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11166-0.

- Emanuelsson, E., and M. S. Stjerberg. 2021. “Regeringen Tvingas Andra Vaccinplanen-Kritiseras.” Expressen, April 2.

- Erste, das. 2021. “Corona Vaccination: This Is How the Federal States Assign Vaccination Dates | The First.” BRISANT, January 22. https://www.mdr.de/brisant/corona-impfung-termin-100.html.

- Figaro, le. 2021. “Covid-19 : La Vaccination Ouverte à Tous Les Adultes Dès Le 31 Mai.” Le Figaro, May 20. https://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/covid-19-la-france-va-avancer-l-ouverture-de-la-vaccination-pour-tous-les-adultes-20210520.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. 2021a. “Nationell Plan För Vaccination Mot Covid-19.” Solna. www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/publicerat-material/.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. 2021b. “Fortsatt Stor Vilja Att Vaccinera Sig Mot Covid-19.” Solna. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/nyheter-och-press/nyhetsarkiv/2021/maj/fortsatt-stor-vilja-att-vaccinera-sig-mot-covid-19/.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. 2021c. “Presskonferens Med Anledning Av Covid-19.” Solna. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iy95jFNwrwo.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. 2021d. “Undersökning Om Acceptans För Vaccination Mot Covid-19 – Resultat Juni 2021.” Solna. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/statistik-och-analyser/acceptans-for-vaccination-mot-covid-19/resultat-juni-2021/.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. 2021e. “Statistik För Vaccination Mot Covid-19.” Solna. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/folkhalsorapportering-statistik/statistikdatabaser-och-visualisering/vaccinationsstatistik/statistik-for-vaccination-mot-covid-19/.

- FOPH. 2021. “Nouvelle Campagne : « Un Geste Du Coeur Pour Tous ».” Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, May 17. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/fr/home/das-bag/aktuell/news/news-17-05-2021.html.

- France24. 2021. “Macron: AstraZeneca Vaccine ‘quasi-Ineffective’ for over-65s.” France24, January 29.

- Fredling, Simon. 2021. “Nu Planeras Covid-Bussar Och Tält För Att Vaccinera Utlandsfödda.” Sveriges Television, September 1. https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/jonkoping/nu-planeras-covid-bussar-for-att-vaccinera-utlandsfodda.

- French, Jeff, Sameer Deshpande, William Evans, and Rafael Obregon. 2020. “Key Guidelines in Developing a Pre-Emptive COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake Promotion Strategy.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (16): 5893. doi:10.3390/ijerph17165893.

- Gallersdörfer, Margarethe. 2021. “Schleppende Nachfrage Für Astrazeneca in Berlin: Impfstoff-Wahlfreiheit War Laut Senatorin Kalayci „vielleicht Ein Fehler”.” Der Tagesspiegel, February 18. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/schleppende-nachfrage-fuer-astrazeneca-in-berlin-impfstoff-wahlfreiheit-war-laut-senatorin-kalayci-vielleicht-ein-fehler/26926026.html.

- Gestblom, Jasmine. 2021. “Stockholms Region Sänker Väntetiden – Nu Får Du Andra Dosen Vaccin Efter Fyra Veckor.” Sveriges Television, July 29. https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/stockholm/stockholms-region-sanker-dosintervallen-nu-kan-du-fa-andra-dosen-vaccin-efter-fyra-veckor.

- Gleißner, Werner, Florian Follert, Frank Daumann, and Frank Leibbrand. 2021. “EU’s Ordering of COVID-19 Vaccine Doses: Political Decision-Making under Uncertainty.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (4): 2169–2112. doi:10.3390/ijerph18042169.

- Grover, Natalie, Heather Stewart, and Ben Quinn. 2021. “Vaccine Passports Will Make Hesitant People ‘Even More Reluctant to Get Jabbed.’” The Guardian, August 31. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/31/vaccine-passports-will-make-hesitant-even-more-reluctant-to-get-jabbed.

- Guidry, Jeanine P. D., Linnea I. Laestadius, Emily K. Vraga, Carrie A. Miller, Paul B. Perrin, Candace W. Burton, Mark Ryan, Bernard F. Fuemmeler, and Kellie E. Carlyle. 2021. “Willingness to Get the COVID-19 Vaccine with and without Emergency Use Authorization.” American Journal of Infection Control 49 (2): 137–142. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018.

- Haudegand, Nelly. 2021. “Il Est à Craindre Que La Communication Sur La Vaccination Ne Demeure En France Un Impensé.” Le Monde, April 19. https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2021/04/19/il-est-a-craindre-que-la-communication-sur-la-vaccination-ne-demeure-en-france-un-impense_6077256_3232.html.

- Haute Autorité de Santé. 2020. “Vaccins Covid-19 : Quelle Stratégie de Priorisation à l’initiation de La Campagne ?” Paris. https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3221237/fr/vaccins-covid-19-quelle-strategie-de-priorisation-a-l-initiation-de-la-campagne.

- Haute Autorité de Santé. 2021. “Covid-19 : La HAS Recommande d’utiliser Le Vaccin d’AstraZeneca Chez Les 55 Ans et plus.” March 19, 2021. https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3244305/fr/covid-19-la-has-recommande-d-utiliser-le-vaccin-d-astrazeneca-chez-les-55-ans-et-plus.

- Henley, Jon. 2021. “Six EU States Overtake UK Covid Vaccination Rates as Britain’s Rollout Slows.” The Guardian, August 6. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/06/six-eu-states-overtake-uk-covid-vaccination-britain-rollout-slows.

- Heures. 2020. “Les Personnes à Risques et Les Soignants Parmi Les Premiers Vaccinés.” 24 Heures. https://www.24heures.ch/les-personnes-a-risques-et-les-soignants-parmi-les-premiers-vaccines-884487868023.

- Hoffmeyer, Dennis. 2021. “In Diesen Kantonen Können Sie Sich Bereits Impfen: Ein Blick Auf Die Impfkampagne Der Schweiz.” Neue Zürcher Zeitung, May 7. https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/schweizer-impfkampagne-gegen-das-coronavirus-eine-uebersicht-ld.1623835?reduced=true.

- Hoppe, Kara K., and Linda O. Eckert. 2011. “Clinical Study Achieving High Coverage of H1N1 Influenza Vaccine in an Ethnically Diverse Obstetric Population: Success of a Multifaceted Approach.” Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2011: 7462142011. doi:10.1155/2011/746214.

- Hrynick, T., S. Ripoll, and M. Schmidt-Sane. 2020. “‘Rapid Review: Vaccine Hesitancy and Building Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccination.” Brighton.

- Hui, Sylvia. 2021. “UK Eager for a Big Reopening Thanks to Vaccine Success.” AP News, May 14. https://apnews.com/article/europe-coronavirus-vaccine-lifestyle-travel-coronavirus-pandemic-acb1a950e774b1dd8ba12523ea02b545.

- Illner, Marie. 2021. “Corona: Warum so Viele Menschen Die Impfung Verweigern.” Web.De. January 14. https://web.de/magazine/gesundheit/corona-menschen-impfung-verweigern-35429676.

- Ipsos MORI. 2020. Ipsos MORI Coronavirus Polling. London.

- Ipsos. 2020. “Global Attitudes on a COVID-19 Vaccine Ipsos Survey for the World Economic Forum.”

- Ipsos. 2021. “LE REGARD DES FRANÇAIS SUR L’INTERVENTION TÉLÉVISÉE D’EMMANUEL MACRON.” Paris. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2021-07/Ipsos%20-%20Intervention%20E.%20Macron%20-%20France%20Info-Le%20Parisien-Aujourd%27hui%20en%20France%20.pdf.

- Jackson, Marie. 2021. “England Vaccine Passport Plans Ditched, Sajid Javid Says - BBC News.” BBC News, September 13. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-58535258.

- Jacobsson, Joel. 2021. “Vaccinplanen Spricker – Alla i Gävleborg Kommer Inte Vara Vaccinerade till Midsommar.” Sveriges Television, March 15. https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/gavleborg/vaccinplanen-spricker-alla-gavleborgare-kommer-inte-vara-vaccinerade-till-midsommar.

- JCVI. 2020. “Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation: Advice on Priority Groups for COVID-19 Vaccination. 2 December 2020.” London. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/224864/JCVI_Code_of_Practice_revision_2013_-_final.pdf.

- JCVI. 2021. “JCVI Interim Statement on Phase 2 of the COVID-19 Vaccination Programme: 26 February 2021.” London. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/priority-groups-for-phase-2-of-the-coronavirus-covid-19-vaccination-programme-advice-from-the-jcvi/jcvi-interim-statement-on-phase-2-of-the-covid-19-vaccination-programme.

- Jecker, Nancy S. 2021. “Vaccine Passports and Health Disparities: A Perilous Journey.” Journal of Medical Ethics. doi:10.1136/medethics-2021-107491.

- Johansson, Åsa. 2021. “Yngre Kan Få Covidvaccin Före Äldre.” Svenska Dagbladet, April 2. https://www.svd.se/yngre-kan-fa-vaccin-fore-aldre-nar-fas-4-inleds.

- Kadambari, Seilesh, and Samantha Vanderslott. 2021. “Lessons about COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Minority Ethnic People in the UK.” The Lancet. Infectious Diseases 21 (9): 1204–1206. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00404-7.

- Kinkartz, Sabine. 2021. “COVID: AstraZeneca Vaccine Remains Unpopular in Germany | Germany | News and in-Depth Reporting from Berlin and Beyond.” DW, February 20. https://www.dw.com/en/covid-astrazeneca-vaccine-remains-unpopular-in-germany/a-56630827.

- Kissling, Victorien. 2021. “Bien Que Divisée Sur Le Vaccin, La Suisse Retrouve Le Moral, Selon Un Sondage SSR Sur Le Covid.” RTS, July 9. https://www.rts.ch/info/suisse/12333960-bien-que-divisee-sur-le-vaccin-la-suisse-retrouve-le-moral-selon-un-sondage-ssr-sur-le-covid.html.

- Kowalewski, Marvin, Franziska Herbert, Theodor Schnitzler, and Markus Dürmuth. 2021. “Proof-of-Vax: Studying User Preferences and Perception of Covid Vaccination Certificates.” ArXiv.

- Kudo, Per. 2021. “Vårdpersonal Prioriterades Framför Äldre.” Svenska Dagsbladet, March 24. https://www.svd.se/vardpersonal-prioriteras-framfor-aldre-i-riskgrupp.

- Larson, Heidi J., William S. Schulz, Joseph D. Tucker, and David M. D. Smith. 2015. “Measuring Vaccine Confidence: Introducing a Global Vaccine Confidence Index.” PLoS Currents 7 (February): ecurrents.outbreaks.ce0f6177bc97332602a8e3fe7d7f7c. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.ce0f6177bc97332602a8e3fe7d7f7cc4.

- Larsson, Ylva. 2021. “Modernas Vaccin Försenas – Och Halveras.” Sveriges Television, February 10. https://www.svt.se/nyheter/inrikes/modernas-vaccin-forsenas-och-halveras.

- Laurell, Isak. 2021. “Moskén Vill Hjälpa till Med Vaccineringen – Får Inget Svar Från Region Skåne.” Sveriges Television, September 2. https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/skane/mosken-erbjuder-hjalp-med-vaccinationer-regionen-nappar-inte.

- Lazarus, Jeffrey v., Scott C. Ratzan, Adam Palayew, Lawrence O. Gostin, Heidi J. Larson, Kenneth Rabin, Spencer Kimball, and Ayman El-Mohandes. 2021. “A Global Survey of Potential Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine.” Nature Medicine 27 (2): 225–228. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9.

- Lazarus, Jeffrey v., Katarzyna Wyka, Lauren Rauh, Kenneth Rabin, Scott Ratzan, Lawrence O. Gostin, Heidi J. Larson, Ayman El-Mohandes, and Ayman El. 2020. “Hesitant or Not? The Association of Age, Gender, and Education with Potential Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine: A Country-Level Analysis.” Journal of Health Communication 25 (10): 799–807. doi:10.1080/10810730.2020.1868630.

- Le Monde and AFP. 2021. “Passe Sanitaire: Plus de 175 500 Manifestants à Travers La France, Selon Le Ministère de l’intérieur.” Le Monde, August 21. https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2021/08/21/sixieme-samedi-de-mobilisation-pour-les-opposants-au-passe-sanitaire_6091988_3224.html.

- Ledford, Heidi, David Cyranoski, and Richard van Noorden. 2020. “The UK Has Approved a COVID Vaccine - here’s what scientists now want to know.” Nature 588 (7837): 205–206. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03441-8.

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Simon Dennis, Andrew Perfors, Yoshihisa Kashima, Joshua P. White, Paul Garrett, Daniel R. Little, and Muhsin Yesilada. 2021. “Public Acceptance of Privacy-Encroaching Policies to Address the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United Kingdom.” Plos ONE 16 (1): e0245740. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245740.

- Lindholt, Marie Fly, Frederik Jørgensen, Alexander Bor, and Michael Bang Petersen. 2021. “Public Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccines: Cross-National Evidence on Levels and Individual-Level Predictors Using Observational Data.” BMJ Open 11 (6): e048172. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048172.

- Lintern, Shaun. 2021. “Institutional Racism Exists in UK and Healthcare, Says Head of NHS Race Body.” The Independent, April 1. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/nhs-health-racism-commission-uk-b1825705.html.

- Liu, Yang, Frank G. Sandmann, Rosanna C. Barnard, Carl A. B. Pearson, CMMID COVID-19 Working Group, Roberta Pastore, Richard Pebody, Stefan Flasche, and Mark Jit. 2021. “Optimising Health and Economic Impacts of COVID-19 Vaccine Prioritisation Strategies in the WHO European Region.” MedRxiv (Preprint), January, 2021.07.09.21260272. doi:10.1101/2021.07.09.21260272.

- Lofstedt, Ragnar. 2005. Risk Management in Post-Trust Societies. Risk Management in Post-Trust Societies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9780230503946.

- Logean, Sylvie. 2021. “En Matière de Vaccination, La Suisse Est à La Traîne.” Le Temps, July 28. https://www.letemps.ch/opinions/matiere-vaccination-suisse-traine.

- Mathieu, Edouard, Hannah Ritchie, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Max Roser, Joe Hasell, Cameron Appel, Charlie Giattino, and Lucas Rodés-Guirao. 2021. “A Global Database of COVID-19 Vaccinations.” Nat Hum Behav 5 (7): 947–953. doi:10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8.

- McLenon, Jennifer, and Mary A. M. Rogers. 2019. “The Fear of Needles: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 75 (1): 30–42. doi:10.1111/jan.13818.

- Mehr, Klaus-Maria. 2021. “Corona-Impfstoff-Verteilung in Bayern: Kliniken Impfen Studenten - Auf Dem Land Sterben Die Senioren.” Merkur, January 31. https://www.merkur.de/bayern/corona-impfstoff-bayern-senioren-klinik-verteilung-studenten-land-stadt-zr-90182817.html.

- Mehta, Amar. 2021. “COVID-19: Young People Told to Get Jabbed or ‘miss out on the Good Times’ as Vaccine Take up Slows.” Sky News, August 11. https://news.sky.com/story/covid-19-nightclubs-join-vaccine-drive-as-young-people-told-to-get-jabbed-or-miss-out-on-the-good-times-12373844.

- Mohdin, Aamna. 2021. “BAME Groups Urged to Have Covid Vaccine in UK TV Ad Campaign.” The Guardian, February 18. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/18/bame-groups-urged-to-have-covid-vaccine-in-uk-tv-ad-campaign.

- MSB. 2021. “Arkiv Regional Information - Krisinformation.Se.” Myndigheten För Samhällsskydd Och Beredskap, April 8. https://www.krisinformation.se/detta-kan-handa/handelser-och-storningar/20192/myndigheterna-om-det-nya-coronaviruset/regional-information-om-coronaviruset/arkiv-regional-information.

- Nehme, Mayssam, Helene Baysson, Nick Pullen, Ania Wisniak, Francesco Pennacchio, María-Eugenia Zaballa, Vanessa Fargnoli, et al. 2021. “Perceptions of Immunity and Vaccination Certificates among the General Population.” MedRXiv doi:10.1101/2021.06.22.21259189.

- Neville, Sarah, and Helen Warrell. 2021. “UK Vaccine Rollout Success Built on NHS Determination and Military Precision.” Financial Times, February 12. https://www.ft.com/content/cd66ae57-657e-4579-be19-85efcfa5d09b.

- NHS England. 2021. “Elton John and Michael Caine Help the NHS Promote COVID Jabs.” NHS, February 10. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2021/02/elton-john-and-michael-caine-help-the-nhs-promote-covid-jabs/.

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics. 2020. Fair and Equitable Access to COVID-19 Treatments and Vaccines. London.

- Odoxa. 2021. Vaccins Contre Le Covid-19 et Autotests. Paris. http://www.odoxa.fr/sondage/oui-a-vaccination-astrazeneca/.

- Olofsson, J. 2021. “Region Skånes Kritik Mot Prognosen: ‘Helt Orimligt.’” Kvallposten, March 29.

- Oltermann, Philip, Angela Giuffrida, and Kim Willsher. 2021. “‘It’s Such a Relief’: How Europe’s Covid Vaccine Rollout Is Catching up with UK.” The Guardian, June 19. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/19/its-such-a-relief-how-europes-covid-vaccine-rollout-is-catching-up-with-uk.

- Owens, Susan. 2000. “Engaging the Public’: Information and Deliberation in Environmental Policy.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 32 (7): 1141–1148. doi:10.1068/a3330.

- Paterson, Pauline, François Meurice, Lawrence R. Stanberry, Steffen Glismann, Susan L. Rosenthal, and Heidi J. Larson. 2016. “Vaccine Hesitancy and Healthcare Providers.” Vaccine 34 (52): 6700–6706. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042.

- Paul, Elise, Andrew Steptoe, and Daisy Fancourt. 2021. “Attitudes towards Vaccines and Intention to Vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for Public Health Communications.” The Lancet Regional Health - Europe 1: 100012. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012.

- Peiris, Malik, and Gabriel M. Leung. 2020. “What Can We Expect from First-Generation COVID-19 Vaccines?” The Lancet 396 (10261): 1467–1469. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31976-0.

- Petersen, Michael Bang, Alexander Bor, Frederik Jørgensen, and Marie Fly Lindholt. 2021. “Transparent Communication about Negative Features of COVID-19 Vaccines Decreases Acceptance but Increases Trust.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (29): e2024597118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2024597118.

- Porat, Talya, Rune Nyrup, Rafael A. Calvo, Priya Paudyal, and Elizabeth Ford. 2020. “Public Health and Risk Communication during COVID-19-Enhancing Psychological Needs to Promote Sustainable Behavior Change.” Frontiers in Public Health 8: 573397. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.573397.

- Pouwels, Koen B., Emma Pritchard, Philippa C. Matthews, Nicole Stoesser, David W. Eyre, Karina-Doris Vihta, Thomas House, et al. 2021. “Impact of Delta on Viral Burden and Vaccine Effectiveness against New SARS-CoV-2 Infections in the UK.” MedRXiv [Preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2021.08.18.21262237

- Public Health England. 2021. “Vaccinations in the UK | Coronavirus in the UK.” Gov.Uk, September 1. https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/vaccinations#card-latest_reported_vaccination_uptake.

- Razai, Mohammad S., Tasnime Osama, Douglas G. J. McKechnie, and Azeem Majeed. 2021. “Covid-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Ethnic Minority Groups.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 372: n513. doi:10.1136/bmj.n513.

- Region Gotland. 2021. “Vaccinationsbokningen Öppnar För Alla Över 18 År - Region Gotland.” Region Gotland, July 8. https://www.gotland.se/111519.

- Renfer, Marc. 2021. “La Vaccination Contre Le Covid-19 Bientôt Au Point Mort En Suisse.” RTS, July 11. https://www.rts.ch/info/suisse/12334559-la-vaccination-contre-le-covid19-bientot-au-point-mort-en-suisse.html.

- Reverby, S. M. 2011. “Listening to Narratives from the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.” Lancet (London, England) 377 (9778): 1646–1647. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60663-6.

- Rieger, Marc O. 2020. “Triggering Altruism Increases the Willingness to Get Vaccinated against COVID-19.” Social Health and Behavior 3 (3): 78. doi:10.4103/SHB.SHB_39_20.

- Rigby, Jennifer. 2021. “Covid-19 Vaccine Rates Plummet as Roll-out Hits Young and Hard-to-Reach.” The Telegraph, July 8. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/science-and-disease/covid-19-vaccine-rates-plummet-roll-out-hits-young-hard-to-reach/.

- Ritchie, Hannah, Edouard Mathieu, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Cameron Appel, Charlie Giattino, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Joe Hasell, Bobbie Macdonald, Diana Beltekian, and Max Roser. 2020. “Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19).” Our World in Data, March 5. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths.

- Robertson, Elaine, Kelly S. Reeve, Claire L. Niedzwiedz, Jamie Moore, Margaret Blake, Michael Green, Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi, and Michaela J. Benzeval. 2021. “Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the UK Household Longitudinal Study.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 94: 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.008.

- RTS. 2020a. “Le Plan de Vaccination Contre Le Covid-19, Un Véritable Défi Logistique.” https://www.rts.ch/info/suisse/11793091-le-plan-de-vaccination-contre-le-covid19-un-veritable-defi-logistique.html.

- RTS. 2020b. “Vaccination Possible Dès Janvier.” https://www.rts.ch/info/11793235-toujours-des-incertitudes-sur-le-deroulement-des-vacances-de-fin-dannee.html#timeline-anchor-1606895175996.

- RTS. 2021. “La Suisse Repousse l’approbation Du Vaccin AstraZeneca Contre Le Covid-19.” RTS, February 3. https://www.rts.ch/info/sciences-tech/medecine/11947549-la-suisse-repousse-lapprobation-du-vaccin-astrazeneca-contre-le-covid19.html.

- Saban, Mor, Vicki Myers, Shani Ben Shetrit, and Rachel Wilf-Miron. 2021. “Issues Surrounding Incentives and Penalties for COVID-19 Vaccination: The Israeli Experience.” Preventive Medicine 153: 106763. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106763.