Abstract

Infrastructure projects increasingly encounter delays due to non-technical risks (NTR), those risks arising from interactions between business and external stakeholders with the potential to create future negative impacts on society and the environment. One sector where NTR is having a significant adverse impact is the global mining sector, where industry leaders rank NTRs as the leading cause of business risk. We investigate how NTRs are assessed during project pre-feasibility using semi-structured interviews with 20 respondents from major mining companies. We find four main factors contribute to the problem of NTR assessment: there is lack of clarity about what constitutes a NTR; there are different interpretations of how NTR is defined and evaluated; there are disciplinary silos within project teams that impede a holistic assessment of risk; and there is conflation between risk and root cause. These factors contribute to striking differences in perceptions of non-technical risks between professionals in project management versus their sustainability colleagues. A four step process is proposed to improve non-technical risk assessment, align project and sustainability professionals, and identify opportunities for mitigation measures. This work seeks to improve NTR management within mining, a sector that is under-represented in existing literature, by adding empirical research examining how project teams identify and assess non-technical risk and contributes to theory at the nexus of project management and sustainability.

1. Introduction

Infrastructure projects such as those required for energy generation and transmission, mass transportation, telecommunications, and waste management, play a crucial role in sustainable socio-economic development (Sierra et al. Citation2018). These large capital projects can be developed by private enterprise, government, or, in some cases, private public partnerships. Regardless of who develops the project, all carry risk: both technical risk and non-technical risk (NTR). Definitions of risk abound but a commonly cited definition comes from the International Standards Organization (ISO) 31000:2018 standard for risk management that describes risk as the effect of uncertainty on objectives. Risk is generally perceived by industry as a threat to operations and profitability (Fredericksen Citation2018).

Research undertaken over the past decade has shown that project delays can be traced more often to NTR, the risks arising from interactions between business and a wide range of external stakeholders (Adekoya and Ekpenyong Citation2016) than to technical engineering risks such as cost, schedule and performance objectives (Brewer and Mckeeman Citation2012; Haddon et al. Citation2013; Franks et al. Citation2014). Many NTRs are tied to issues of sustainable development. Yet sustainability remains an often over looked aspect of project management (El Khatib et al. Citation2020). Stakeholders, and Indigenous rightsholders, are increasingly concerned about topics such as ethics, environmental management, and economic efficiency during the project life cycle and this has led to sustainability becoming an increasingly significant factor in project management (Kivila, Martinsuo, and Vuorinen Citation2017). Taken individually, project management and sustainability have been well studied but the intersectionality of these two fields and how they interact inside project teams requires additional attention (Martens and Carlvalho Citation2017). This has led to the emergence of a new field of study on sustainable project management, defined as, ‘the planning, monitoring and controlling of project delivery and support processes, with consideration of the environmental, economic and social aspects of the life cycle of the project’s resources, processes, deliverables and effects, aimed at realizing benefits for stakeholders, and performed in a transparent, fair, and ethical way that includes proactive stakeholder participation’ (Silvius and Schipper Citation2014 p.79).

For many years, the process for designing major projects has included the well established practice of risk assessment, which is embedded in the guidelines of leading project management associations including the Project Management Institute, the International Standards Organization, and lending agencies such as the World Bank. A common approach to risk assessment for large capital projects focusses on three attributes – cost, time and quality (Silvius et al. Citation2017) – sometimes referred to as the engineer’s iron triangle. Notwithstanding the well-established process for risk assessment, large infrastructure projects frequently are not delivered on budget or on time, thereby failing to meet project objectives (Flyvbjerg, Garbuio, and Lovallo Citation2009). And despite the finding that NTR have the potential to result in capital cost overruns, project delays, and social conflict (Pope et al. Citation2013, Citation2017), mandatory requirements for companies to integrate NTR to their trade-off scenarios and cost-benefit analysis are not common practice (Morrison-Saunders and Pope Citation2013; Boerner Citation2015; Martens and Carvalho Citation2017). These findings raise questions about the efficacy of the current risk assessment process (Haddon et al. Citation2013; Northey, Mudd, and Werner Citation2018).

One sector significantly affected by NTR is mining. In an empirical study evaluating 67 mine development projects from 2008 – 2012, 81% of project delays were due to non-technical risks such as lack of social acceptance, environmental issues, permitting concerns, and land access (Hoff et al. Citation2015). This is perhaps one reason why mining executives consistently rate NTR as the top business risks facing the sector (EY Citation2023).

Some aspects of NTR in the mining sector have been well studied. For example, the costs of conflict (Franks et al. Citation2014), issues associated with social license (Owen and Kemp Citation2013; Prno and Slocombe Citation2012; Moffat and Zhang Citation2014), and the use corporate social responsibility as a risk mitigation strategy (Fredericksen Citation2018). However, a literature review of risk assessment methods in the mining sector showed a knowledge gap between risk assessment and management, especially at the nexus of project planning and sustainability (Tubis, Werbińska-Wojciechowska, and Wroblewski Citation2020). Of note, little work has been done investigating how mining companies define and assess NTR at the stage when mining projects are being planned: a time when 80-90 per cent of a project’s life-cycle economic and ecological costs are established (Hawkin, Lovins, and Lovins Citation2010).

This paper contributes to the emerging field at the nexus of project management and sustainability (for example, Martens and Carvalho Citation2017; Silvius Citation2017; Silvius and Schipper Citation2014) by investigating NTR assessment at the design stage of major infrastructure projects in the mining sector. The views of project managers and sustainability personnel within ten multi-national mining companies were compared and contrasted to explore which project risks are evaluated and how effectively NTR are integrated to project planning. The paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, the methodology is explained, then the findings and conclusions are presented and discussed, and areas for future research are explored.

2. Methods

For this study, the global mining sector was examined to build understanding of NTR assessment during project planning. This deeper understanding is intended to increase clarity about the evaluation of NTR and provide practical solutions. Three research questions were investigated. (1) What risks are assessed during project planning and design? (2) What are the root causes of inadequate NTR assessment? (3) What tools and approaches could improve NTR assessment and associated project outcomes?

To identify companies to be included in the study, a two-step sampling strategy was used. First, results from the December 2017 rankings of three leading sustainability performance indexes – Dow Jones Sustainability Index World, Sustainalytics Index World, and Mining and Metals Bloomberg ESG Index – were reviewed to identify mining companies included in the rankings. The rationale for selecting companies in those indexes is based on a ‘best in sector approach ‘, with the assumption that companies listed in those leading sustainability indexes are the most likely to have robust practices to integrate sustainability to mine planning and operations. Following the review of the indices, 10 companies were identified for this study.

Once the research sample was selected, the second step was to identify interview candidates. After considering academic evidence of departmental silos, communications issues, and decision-bias affecting decision-making (Hart, Milstein, and Ruckelshaus Citation2003; Kunz, Kastelle, and Moran Citation2017; Levine, Chan, and Satterfield Citation2015; Ostrom et al. Citation1999), the research objective was to interview two different professional perspectives – project and sustainability – from each of the 10 sample companies. It was assumed that mining project professionals (those tasked with building and commissioning large capital expense projects) would have expertise with technical risk and knowledge of non-technical risk, while the expertise of their sustainability counterparts would be the reverse.

Interview candidates were identified via LinkedIn, an online professional networking platform, and at international mining conferences and industry training sessions. The selection criteria for mining project professionals was a minimum of fifteen years of experience in management of large capital projects and with decision-power at the project evaluation stage. The selection criteria for mining sustainability professionals was their responsibility to embed sustainability considerations into the assessment of project decision options. Interview candidates were contacted by email explaining the purpose of the study. The first interviewee within the organization helped to identify his/her counterpart through snowball sampling, i.e. when a project professional was the first to be interviewed, he/she would recommend a person meeting the selection criteria from sustainability or vice-versa. The final interview sample (N = 20) consisted of nine senior project professionals (i.e. chief project officers and/or plus 25 yrs. of experience) and 11 senior sustainability professionals (i.e. chief sustainability officers, director and/or with global responsibility). Although the sample size was 20 respondents, small samples can render accurate information if participants possess a high degree of competence for the domain of inquiry (Guest, Bunce, and Johnson Citation2006, p. 74). In addition, findings of small sample qualitative studies, such as this, may be of use in informing future discussions (Marshall and Rossman Citation2014, p. 84) of NTR assessment within the mining sector.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between April and August 2018 using an interview guide. The guide was developed using questions that emerged from gaps found in sustainability science, project management, economics, and grey literature. The key questions explored during the interviews included: What types of risks do you assess when evaluation a project stage before the preferred option is selected? How do you interpret the concept of non-technical risk? How do you evaluate NTRs? What is missing for an effective integration of NTRs into project assessments? And what practical recommendations would you give to a new comer in project management who has responsibility for conducting project assessments during the pre-feasibility stage? Interviews were undertaken in compliance with the requirements of the UBC Research Ethics Board [Certificate of Minimal Risk BREB H17- 02014].

To explore the causes and effects of the inadequate integration of NTR in project evaluations, and to attempt to identify the root cause of the problem, an iterative interrogative technique – known as the five whys – was used. The five whys methods explores cause-and-effect relationships underlying a particular problem by repeatedly asking ‘why’(Chiarini, Baccarani, and Mascherpa Citation2018).

Interviews were conducted in WebEx, an online tool for video conferencing, enabling the participation of experts located in countries around the world. Interviews lasted from 30 to 45 min on average. Each interview was recorded and then transcribed using Sonix software. Section by section coding was performed in NVivo, a data analysis software tool that allows for quantitative (number of mentions of key words) plus qualitative (interpretation and understanding) analysis using key words from within the text as a proxy for importance. The data categories emerged from bottom-up coding, meaning codes are a result of data analysis not the literature. An inductive approach was used to enable a constant comparison of data with data, category with category, which is aligned with grounded theory (Charmaz Citation2006). Thus, concepts and theoretical constructs are grounded in the research data.

To maintain the confidentiality of participants, company names were masked by codes (i.e. C1) and interviewees were assigned classification per expertise ‘project ‘(PP) and ‘sustainability ‘(SP).

3. Results

3.1. Risk identification

Both groups of respondents indicated that NTR are not being adequately assessed in the early planning of mining projects. When asked to comment on why that was the case, SP and PP had similar views, noting that, ‘Within mining we don’t often [consider] social and environmental [issues] as being technical risks …Non-technical risks are considered as externalities’ (SP interview quote). PP had a similar view, making the observation that: ‘… we understand the risks that are within our [mine license] boundary. We don’t understand the risks on the outside of the boundary very well. In the past [externalities] were not considered important… ‘ (PP interview quote). Respondents were of the opinion that, within mining companies, there can be a tendency to think of technical risk as internalities, those items that can be controlled by the company. NTR are viewed as externalities, items that are outside company control.

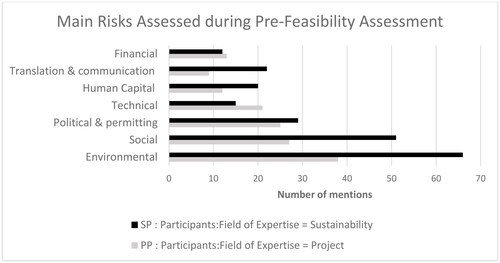

To clarify how risks are categorized, interviewees were asked, ‘What risks are considered during the project evaluation stage?’ (). Somewhat surprisingly, NTR were ranked ahead of technical risks: environmental risks (25%), social risks (19%) and political/permitting risks (13%).

Figure 1. Topics most frequently raised by respondents when asked to identify risks considered during the project evaluation stage. Risks were categorized based on number of mentions by project professionals (PP - grey) and sustainability professionals (SP - black). Top environmental risks included water, biodiversity and energy/climate change .Other risks raised where number of mentions were fewer include: reputation (14 total mentions); closure (11 total mentions); health and safety (eight total mentions), corporate governance (six total mentions), catastrophe (five total mentions), exploration (five total mentions), and value chain (two total mentions).

Within the top three categories, there were interesting similarities and differences of opinion between SP and PP. For example, NTRs that were classified to the environment category included water (33%), biodiversity (23%) and energy/climate change represented (17%). Both SP and PP identified water, biodiversity, energy, and climate change as the top environmental risks, yet when interviewees were asked why these risks are critical, significant differences of opinion were noted. For most PP, environmental risk must be considered because it constitutes an inbound risk – a threat to operations and profitability. SP see the need for a more holistic approach to considering environmental risk. While acknowledging the importance of inbound risk, SP stressed the need to consider outbound risk - the potential environmental risk imposed by the mining operation upon nearby communities. SP also acknowledged that outbound risks can rebound thereby creating inbound risks to a projectFootnote1. For example, in areas of water scarcity, PP note there can be inbound risk associated with the ability, or lack thereof, to access water of the quality and quantity needed for mining operations. SP warned that competition for a scarce resource such as water can create an outbound risk to nearby communities, which also need water, and that competition can trigger conflict, creating a rebound, or additional inbound risk for the mine. SP therefore argue that ‘… [we need to consider] anything where an external community of interest can impact a project or we can impact an external community of interest in a way that impairs their access to resources or isn’t aligned with their development aspirations or community value’ (SP interview quote).

PP indicated that adequate project decisions and effective environmental risk management can usually be achieved as long as regulatory requirements are met. SP disagreed yet noted that companies ‘… are more likely to [pay attention to issues] if there is a regulatory requirement. That’s the reality’ (SP interview quote). Biodiversity provided an illustrative example of the differences of opinions between SP and PP.

Although both PP and SP identified biodiversity as one of the leading NTR environmental risks, it is noteworthy that biodiversity was defined as a NTR almost three times more frequently by SP than PP. SP questioned whether corporate objectives (such as net positive impact) can be achieved if project decisions continue to be based primarily on regulation requirements, which can vary widely from one operating jurisdiction to the next, with one SP noting ‘…you’re more likely to dig into this [net positive impact on biodiversity] in more detail if you got regulatory requirements, that’s the reality’ (SP). SP called for comprehensive biodiversity screening to be added to design scenarios so that, regardless of regulatory requirements, areas for protection could potentially be identified proactively. SP believe early biodiversity screening could reduce tensions with neighbouring communities that view the area worthy of protection.

Of note, SP and PP agree there is one area where action is being taken in the absence of regulation: climate risk. Both groups of respondents noted that climate risk is increasingly being integrated to project models as a forward-looking strategy before costs materialize, and that consideration of carbon risk appears to be happening even in regions where carbon costs are not yet regulated.

Additional common ground was found on the issue of social risk, defined as risk to people from the project (Kemp, Worden, and Owen Citation2016). Both SP and PP agreed that social risks are not being adequately assessed as project plans and design options are considered, and both groups pointed to the potential for project impairment and capital erosion if community opposition develops. However, SP noted that social risk – the outbound risk to surrounding communities from mining operations - can be conflated with business risk – the inbound risk to the mining operation from community opposition. Interviewees’ concern about risk directionality is consistent with research showing that social risk and business risk are inter-related and conflated (Franks et al. Citation2014, Graetz & Franks Citation2016, Kemp, Worden, and Owen Citation2016). SP believe that to effectively manage social risk, NTR assessments need to consider cultural values, human rights, the impact of mining on community livelihoods, infrastructure and services, and traditional pursuits; not just impacts to the operations from community opposition.

Both SP and PP identified permitting and political risks, including the potential for government nationalization, political instability, and changing regulatory requirements, as critical topics to assess early in project planning. Both groups felt that due to lower levels of governance, social-economic conditions and corruption, NTR arising from permitting and politics is higher in non-OECD countries. Although several PP did highlight the importance of integrating NTR as a corporate strategy beyond regulation, their primary focus during capital project evaluation, as noted above, was complying with regulation versus the mitigation of societal costs.

[Permitting risks] drive the project schedule. Because it doesn’t matter how much we have planned the construction and everything else. If we cannot build it, we cannot operate it. So, until [permitting risks] are all vetted and set, we usually don’t give a green light for major [project] spending. (PP)

This is contrasted with SP who suggested that companies have an obligation to deliver benefits from mining to resource-rich communities.

You come into a country, you are going into a partnership, so you have an ethical and moral obligation to help bring them along the journey, not just sit back and say we do not need to do that in this country because it is not required [by law]. (SP)

Among the NTR that respondents raised, several risks not identified in the literature were referenced by both groups and thus are interesting to explore in more detail. The topics raised by interviewees were grouped according to human capital risks, or translation and communication risks. The human capital category captured mentions of lack of skills, knowledge, and the experience possessed by, or needed by, company employees. Items classified to translation and communication included mentions of disciplinary silos that impede inter-team communication, different interpretations of risk with NTR classified as soft risks versus quantifiable technical risks, and a lack of agreement between PP and SP on the relevance of social issues to project planning.

As will be further explored in the discussion, it could be argued that human capital and poor communication across disciplinary silos represent root causes of inadequate NTR assessment, rather than NTR in and of themselves. It is therefore important to note that respondents had a rationale why human capital and translation and communication challenges should be identified as NTR. Respondents felt that a lack of expertise (52%), lack of integration among departments or discipline silos (18%) and lack of representation in the decision room - i.e. not having the right people involved in project appraisal decision-making (15%) - creates a danger that the risk assessment process for new projects will miss input that is critical for good decision making early in project planning. In other words, these non-technical issues pose a risk to the success of the project.

Respondents also suggested that human capital risks are exacerbated by communication barriers between social scientists and engineers (‘It’s like having people in a room that speak different languages’ SP); a failure to make sense of the data from communities – or to make it relevant for project decisions; a failure to understand the ways in which community perspectives can affect project decisions; and, a subsequent risk of failing to incorporate that information to the project’s technical planning. Once again, these non-technical issues create project risk.

SP reflected that decision makers for large mining projects are likely to be more familiar with technical problems and solutions versus the ambiguities and complexities of social risks. Moreover, the difficulty of translating social science data into financial valuations can mean that SP concerns, based on qualitative assessments, may not resonate with project decision makers.

Project engineers say, we discarded those potential criteria because they are too qualitative or we don’t have hard data for it. Whereas I’m trying to say that if it’s important, we should try to capture it, even as a qualitative measure. (SP)

Communication challenges were also on the minds of PP who suggested that problems arise because SP do not understand the scheduling and budget constraints of major projects, their recommendations need to be more practical and less aspirational, and that SP can fail to build a financial business case for their recommendations. SP warn that when making the business case for NTR management, PP need to recognize that even risks that cannot be monetized need to be considered. And teams seem to be moving in this direction, with some companies in the sample beginning to offering training to engineers in various sustainability valuation tools. The challenge is that,

There’s no mathematic formula for [NTR assessment]. There’s no spreadsheet that can do it. And I think that frustrates a lot of people in our industry. Engineers and finance people find the messiness, the uncertainty, the lack of linear process around [NTR assessment] hard to understand. (SP)

3.2. Root causes of ineffective NTR assessment

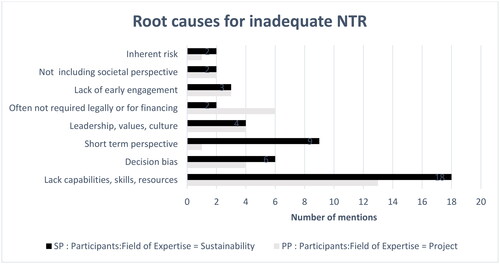

Having determined there is consensus that NTR are not being assessed as rigorously as technical risks, and having identified the main NTR that PP and SP feel are important to consider, interviewees were asked to reflect upon the potential root causes of weak NTR assessment (). SP and PP were in agreement that a lack of capabilities, skills and resourcesFootnote2 is the most likely root cause for poor NTR assessment. Both groups also worried that local stakeholders and rightsholders are not engaged in planning discussions until formal environmental and social impact assessments are initiated. This can mean that social perspectives are not an input to the evaluation undertaken when mining projects are being designed. The two groups were also relatively aligned on the idea that decision bias towards technical considerations and the tendency to make assumptions based on past experience are root causes for the under-valuation of NTR into project decisions. However, while the top root cause was mentioned almost equally by SP and PP, the two groups differed on the second most mentioned topics.

Figure 2. Reasons given by project professionals (PP) and sustainability professionals (SP) for the undervaluation and/or under representation of NTR in project decisions. Rather than a single root cause, interview participants pointed to a set of interwoven factors.

For SP, the second most mentioned root cause of inadequate NTR evaluation was pressure to deliver short-term project objectives. More specifically, that a short-term focus makes it harder to integrate NTR proactively and creates obstacles for project commitments to sustainable development. This consideration was rarely mentioned by their PP counterparts who felt that a lack of regulatory and legal requirements are amongst the leading causes of poor NTR assessment. PP noted that the incorporation of NTR is seldom required by law, something they suggested was necessary to support more stringent corporate environmental and social action.

Comparing and points to a paradox with interviewees identifying a number of issues as both a risk and a root cause of ineffective NTR assessment. For example, 38% of interviewees mention lack of capabilities, skills and resources as a leading root cause for a failure to adequately assess NTR. The issue also appeared within the human capital risks category, suggesting there may be conflation between risk and root causes. This point is elaborated on within the discussion.

3.3. Tools and approaches to improve NTR assessment

When asked, ‘What tools and approaches could improve NTR assessment and associated project outcomes? interviewees had a number of suggestions. They identified a variety of tools available to support NTR assessment and incorporate NTR considerations and estimates to the business case. Some of the most frequently mentioned tools included performance guidance (e.g. the Equator Principles) standards (e.g. those developed by the International Finance Corporation), reporting protocols (e.g. Towards Sustainable Mining) management processes (e.g. multi-criteria decision analysis) and proprietary sustainability valuation tools. However, given the complex nature of NTR assessment, the interconnectedness of root causes, and the potential for risks and root causes to be conflated, both PP and SP agree that better tools alone are not the only solution to the problem. As pointed out by one SP, ‘Tools are one piece, but the tools are only as good as the people using them’.

Rather than relying solely upon tools, interviewees advocated for an integrated toolset, mindset, and skillset approach. The objective of the integrated approach is to reduce decision, optimism, confirmation, and anchoring biases, and help teams overcome a compliance mindset, which, as discussed earlier, may ignore or undervalue sustainability considerations.

A triangle of toolset, mindset and skillset [should be considered]. So good tools are one thing, you need to know how to use tools, to use those skills, but mindset is even more critical (SP).

To improve NTR assessment, interviewees also pointed to the need to minimize unilateral decisions based on disciple-oriented expertise. Having a multi-disciplinary team was cited as a means to complement the traditional ‘within-the-fence’ evaluations with an ‘outside-the-fence perspective. It was suggested this will provide a better sightline on both risk to people (social risk) and risk to the project (business risk), and enable better NTR assessment early in project planning. Interviewees also argued for improving stakeholder engagement skills and processes so that community interests and recommendations can be integrated early in the planning process.

There was also recognition that to effectively assess NTR, there is a need for project leaders to operationalize corporate values of sustainable development and collaboration. Interviewees pointed to the criticality of combining incentives for the long-term, from what one SP called ‘conscious capitalism’, to enable companies in the mining sector to develop capital assets that have a smaller environmental footprint and contribute to social-cultural-economic well being.

provides a summary of the main points of differentiation in the interview responses between project professionals and sustainability professionals.

Table 1. Summary of key points of differentiation in how project professionals and sustainability professions define, assess and measure non-technical risks that both groups agree have the potential for project impairment and capital erosion should community opposition develop.

4. Discussion

PP and SP agree that NTR is not being adequately assessed early in the planning process for mine development. Analysis of the interview data suggests the causes for this failure are complex and interwoven. Four main factors contribute to the problem: there is lack of clarity about what constitutes a NTR; there are different interpretations of how NTR is defined and evaluated; there are disciplinary silos within project teams that impede a holistic assessment of risk; and there is conflation between risk and root cause.

Differences of opinion about what constitutes a NTR are evident in the research findings and create barriers to effective risk identification, assessment, and management. At issue is the question of whether it is sufficient for project teams to assess only those risks with the potential to adversely affect operations or profitability – inbound risks. There is a growing body of literature suggesting this traditional approach is ineffective. In addition, there are increasing demands from stakeholders, including funding agencies such as the World Bank and International Finance Corporation, for the definition of NTR to include outbound risk – those risks created by a proposed project to the environment and people living nearby. There is also the potential for inbound or outbound risks to change direction, creating a rebound risk. As Kemp, Worden, and Owen (Citation2016) have noted, the issue of risk directionality is pertinent as it can lead to situations where risk assessment is incomplete thereby affecting both project management and sustainability performance.

Interviewees observe that projects may appear to have optimal engineering design, with solid financial forecasts, however, if the views of community stakeholders and rightsholders are not sought during the risk assessment process the project budget and timeline can be subjected to delays. It appears that few companies proactively seek external validation of risks identified by the project team during the project assessment process. Yet, the views of external stakeholders can identify potential social, regional biodiversity, and ecosystem services impacts not foreseen by company personnel. The tension that can develop between companies and communities when NTR are not adequately assessed in the early stages of project planning is costly, both in terms of the financial cost for redesign and re-engineering, and in terms of operational and reputational erosion. Franks et al. (Citation2014) estimate that mining projects with a capital budget of U$3 – 5 billion are at risk of losing up to US$20 million per week (in delayed production in net present value terms) if social unrest stalls or derails projects. In addition, there is the potential for adverse impacts on a company’s reputation capital. Eccles (Citation2007) warn that in ‘an economy where 70% to 80% of market value comes from hard-to-assess intangible assets such as brand equity, intellectual capital, and goodwill, organizations are especially vulnerable to anything that damages their reputations ‘. As many mining companies are large multinational businesses that are publicly traded on the world’s financial exchanges, and therefore subjected to scrutiny by investors, regulators and others with an interest in environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance, the value of reputation capital can be considerable.

Defining what constitutes a NTR and determining which ones should be assessed is part of the problem. Evaluating NTR is another part of the problem. The research highlights the potential for project teams in the mining sector to view technical risks and the associated economic considerations as easier to manage. This focus arises because many engineering project teams are most comfortable assessing risk that can be quantified and categorized according to probability and impact. Furthermore, there can be government or financial market regulations governing technical risk, with financial penalties for non-compliance. Interview respondents noted that regulation is an important consideration in project planning and, if present could, function as a motivation for companies to consider NTR more diligently.

Part of the problem defining and evaluating NTR arises from disciplinary silos that exist within mining companies. Fredericksen (Citation2018) noted that the language of risk unifies disparate departments within mining companies. Nevertheless, disciplinary silos can cause the definition and evaluation of NTR to be ‘lost in translation’ (SP). Even when PP and SP are assigned to the same team, interviewees noted that their ability to communicate effectively with one another can be challenging: technical personnel tend to use quantitative methods to model risk, sustainability professionals often rely upon qualitative methods. Furthermore, while SP have expertise in NTR assessment and management, and, increasingly, access to frameworks to support a business case for NTR, it appears their skills may not be sufficient to offset a decision bias towards technical factors. Valuing NTR, and associated externalities such as natural capital and human well-being, are viewed as complex and messy. The end result may be a feeling that technical issues, which can more easily be quantified and monetized, are more legitimate risks than social, political, and environmental considerations during capital project assessments. This decision bias, combined with the difficulty to measure and monetize NTR risks, causes SP to worry that social considerations may be screened out of the risk register before being assessed, or given less weight than merited. The resulting risk register will therefore be incomplete which, in turn, impedes the ability to deliver projects on time and on budget.

shows the agreement of SP and PP on the top three risks considered in project management for new mining projects. There are also commonalities in the next most referenced risks with both groups nominating technical risks, as well as risk labelled as human capital and translation and communication. The fact that both groups see internal company issues as a NTR merits discussion to assess whether these issues constitute non-technical risk, as interviewees suggest, or if they are a root cause of inadequate NTR assessment, where the issue is once again raised by respondents.

The definition of non-technical risk used in this paper is risks arising from interactions between business and external stakeholders with the potential to create future negative impacts on society and the environment. A central tenet of this definition is that NTR arises from interactions with external stakeholders. When PP and SP reference human capital and translation and communication risk, they are identifying barriers to effective communication within project teams – i.e. internal stakeholders. While poor communication by internal experts and/or a lack of understanding within project teams can impede project success, we contend that the inability of project teams to communicate well is a root cause of poor NTR assessment and management, not in and of itself a NTR.

Conflation between risk and root cause is a concern. Resolving internal barriers to NTR requires different action and resources than those required to detect, assess and abate inbound risk to the project, outbound risk to people and the environment from the project, and rebound risks that affect both. As project management teams continue to be adversely impacted by NTR, we conclude by proposing a four step process which we theorize could help to guide project teams in improving NTR assessment.

Step 1: Clarify the definition of NTR so the project managers and sustainability professionals are in agreement. Reducing conflation between risk and root cause will allow technical, financial and human resources to be appropriately allocated.

Step 2: Identify social, environmental and political considerations by assessing inbound risks to the project; outbound risks from the project; and those risks that – if poorly managed – could change direction creating a rebound risk.

Step 3: Determine the methods - quantitative, qualitative, and mixed - that will be used to assess each type of risk. Agree on how a risk will be valued in cases where it is not possible to monetize it.

Step 4: Seek external validation of the risk assessment and mitigation measures from communities of interest most immediately impacted by the proposed project. The external validation may also identify opportunities for risk mitigation and/or for collaboration to support sustainable development.

An interesting opportunity for future research would be to test the extent to which this proposed process improves NTR risk assessment and management.

5. Conclusions

Interviews with project management and sustainability professionals from 10 mining companies ranked on leading sustainability indices provide empirical evidence that non-technical risks are not being adequately assessed when major capital projects are being planned. There is no single reason for this deficiency. There are both internal and external issues to resolve.

Internally, we find a divide between project management professionals and their sustainability counterparts on important issues related to identifying and assessing non-technical risks. It appears most companies remain focussed on technical and economic considerations during project planning, with a view to securing permits and to meeting other regulatory or legal requirements. The research found that there is little evidence of mandated requirements for assessing NTR. Even within companies considered sustainability leaders, externalities can be considered outside the scope of requirements for risk assessment. Overwhelmingly, it was found that project management professionals focus on inbound risk to the project – or business – while their sustainability colleagues stress the need to consider outbound and rebound risks as well as business risk.

With NTR continuing to be a leading cause of major project delays, the business case for NTR should be clear. Sustainability professionals accept the importance of finding ways to translate NTR into language that resonates with those more familiar with technical risk but tensions remain over how best to assess externalities.

A number of research participants, both SP and PP, felt that internal issues, such as disciplinary silos, a lack of understanding of qualitative methods, and the aforementioned decision bias towards technical risks, constitute NTR. While there is potential for internal factors to impede project success we posit that internal barriers are root causes of poor NTR assessment, not non-technical risks.

This paper makes three contributions to research at the nexus of project management and sustainability. First, it adds empirical research examining how project teams within mining companies identify and assess NTR when planning large capital projects. Second, the research is focussed on a sector under examined in project management literature. Third, the research draws attention to the continuing debate between root cause and non-technical risk. The potential conflation between a NTR and a root cause of poor NTR was not evident until the data analysis of the interviews was underway. As a result there was no opportunity to explore this finding with the research participants, thereby creating an area for future research.

Resolving the conflation between risk and root cause is one step to improve the process. Equally important, is the need to assess inbound as well as outbound risks, and to consider where there is the potential for a change in risk direction thereby creating a rebound risk. The desire to rely upon quantitative methods for risk assessment and monetization needs to be balanced with qualitative methods that support non-financial valuation. And all risks should be reviewed with external communities of interest earlier in the planning process to ensure the assessment is robust and to identify sustainable development priorities. As Graetz and Franks (Citation2016) have noted, the inverse of risk is opportunity. This research identifies opportunities to improve non-technical risk assessment, which is predicted to help project teams meet their objective of delivering projects on time, on budget and in a manner that supports sustainable development outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Kemp, Worden and Owen (Citation2016) provide a discussion of risk directionality.

2 It should be noted that respondents identified a number of frameworks, tools and guidance documents to support the integration of NTR to project assessments. These included the International Finance Corporations Performance Standards, Towards Sustainable Mining, the Global Reporting Initiative, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, as well as company specific risk registers, scenario planning, decision trees, probability assessments and, in some jurisdictions, permitting requirements for consultation and social impact assessment.

References

- Adekoya, A., & Ekpenyong, E. (2016). Managing non-Technical Risks in Exploration and Production (E&P) Projects: Opportunities to leverage the Impact Assessment Process. Paper presented at the 36th Annual Conference of the International Association for Impact Assessment. Aichi-Nagaya: IAIA.

- Boerner, H. 2015, March/April. “Importance of Intangibles Reflected in ESG Performance Metrics for aGrowing Number of Investors.” Corporate Finance Review, 19 (5): 28–32.

- Brewer, L., and R. Mckeeman. 2012. “Non-Technical Risk Leadership : Integration and Execution.” In Spe 157575

- Charmaz, K. 2006. “In Vol. 10 Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage. doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2007.11.003.

- Chiarini, A., C. Baccarani, and V. Mascherpa. 2018. “Lean Production, Toyota Production System and Kaizen Philosophy: A Conceptual Analysis from the Perspective of Zen Buddhism.” The TQM Journal 30 (4): 425–438. doi:10.1108/TQM-12-2017-0178.

- Eccles, R. N. 2007. “Reputation and Its Risk.” Harvard Business Review 85 (2): 104–114.

- El Khatib, M., K. Alabdooli, A. AlKaabi, and S. Al Harmoodi. 2020. “Sustainable Project Management: Trends and Alignment.” Theoretical Economics Letters 10 (06): 1276–1291. doi:10.4236/tel.2020.106078.

- ERM. 2015. “Managing Non Technical Risks in Major Capital Projects Why is Social Licence to Operate Important?” Accessed July 20 2022. https://www.erm.com/insights/effective-management-of-esg-risks-in-major-infrastructure-projects/

- EY. 2023. “Top 10 Business Risks and Opportunities for Mining and Metals in 2023.” EY. Accessed February 15 2023. https://www.ey.com/en_gl/mining-metals/risks-opportunities

- Flyvbjerg, Bent, Massimo Garbuio, and Dan Lovallo. 2009. “Delusion and Deception in Large Infrastructure Projects.” California Management Review 51 (2): 170–194. doi:10.2307/41166485.

- Franks, D., R. Davis, A. Bebbington, S. Ali, D. Kemp, and M. Scurrah. 2014. “Conflict Translates Environmental and Social Risk into Business Costs.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (21): 7576–7581. doi:10.1073/pnas.1405135111.

- Fredericksen, T. 2018. “Corporate Social Responsibility, Risk and Development in the Mining Sector.” Resources Policy 59: 495–505. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.09.004.

- Graetz, G., and D. Franks. 2016. “Conceptualising Social Risk and Business Risk Associated with Private Sector Development Projects.” Journal of Risk Research 19 (5): 581–601. doi:10.1080/13669877.2014.1003323.

- Guest, B., A. Bunce, and L. Johnson. 2006. “How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability.” Field Methods 18 (1): 59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903.

- Haddon, M.,. L. Brewer, T. Hall, and B. Spence. 2013. “SPE 163735 a License to Grow : Three Strategies to Meet the Challenge of Non- Technical Risk in Capital Project Portfolios.”

- Hart, S. L., M. B. Milstein, and W. Ruckelshaus. 2003. “Creating Sustainable Value.” Academy of Management Perspectives 17 (2): 56–67. doi:10.5465/ame.2003.10025194.

- Hawkin, P., A. Lovins, and H. Lovins. 2010. Natural Capitalism: The Next Industrial Revolution. London: Earthscan.

- Hoff, M., J. Das, S. Murfatt, and A. Martin. 2015. “Effective Management of ESG Risks in Major Infrastructure Projects.” In Managing Risk in Infrastructure Investment, edited by J. Altman, 281. London: Private Equity International. https://www.erm.com/insights/effective-management-of-esg-risks-in-major-infrastructure-projects/.

- Kemp, D., S. Worden, and J. Owen. 2016. “Differentiated Social Risk: Rebound Dynamics and Sustainability Performance in Mining.” Resources Policy 50: 19–26. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2016.08.004.

- Kivila, J., M. Martinsuo, and L. Vuorinen. 2017. “Sustainable Project Management through Project Control in Infrastructure Projects.” International Journal of Project Management 35 (6): 1167–1183. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.02.009.

- Kunz, N. C., T. Kastelle, and C. J. Moran. 2017. “Social Network Analysis Reveals That Communication Gaps May Prevent Effective Water Management in the Mining Sector.” Journal of Cleaner Production 148: 915–922. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.175.

- Levine, J., K. M. A. Chan, and T. Satterfield. 2015. “From Rational Actor to Efficient Complexity Manager: Exorcising the Ghost of Homo Economicus with a Unified Synthesis of Cognition Research.” Ecological Economics 114: 22–32. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.03.010.

- Martens, M. L., and M. M. Carvalho. 2017. “Key Factors of Sustainability in Project Management Context: A Survey Exploring the Project Managers’ Perspective.” International Journal of Project Management 35 (6): 1084–1102. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.04.004.

- Marshall, C., and G. B. Rossman. 2014. Designing Qualitative Research, 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage publications.

- Moffat, K., and A. Zhang. 2014. “The Paths to Social Licence to Operate: An Integrative Model Explaining Community Acceptance of Mining.” Resources Policy 39: 61–70. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2013.11.003.

- Morrison-Saunders, A., and J. Pope. 2013. “Conceptualising and Managing Trade-Offs Insustainability Assessment.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 38: 54–63. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2012.06.003.

- Northey, S. A., G. M. Mudd, and T. T. Werner. 2018. “Unresolved Complexity in Assessments of Mineral Resource Depletion and Availability.” Natural Resources Research 27 (2): 241–255. doi:10.1007/s11053-017-9352-5.

- Ostrom, E., J. Burger, C. B. Field, R. B. Norgaard, and D. Policansky. 1999. “Revisiting Thecommons: Local Lessons, Global Challenges.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 284 (5412): 278–282. doi:10.1126/science.284.5412.278.

- Owen, J., and D. Kemp. 2013. “Social Licence and Mining: A Critical Perspective.” Resources Policy 38 (1): 29–35. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.06.016.

- Pope, J., A. Bond, J. Hugé, and A. Morrison-Saunders. 2017. “Reconceptualising Sustainability assessment.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 62: 205–215. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2016.11.002.

- Pope, J., A. Bond, A. Morrison-Saunders, and F. Retief. 2013. “Advancing the Theory and Practice of Impact Assessment: Setting the Research Agenda.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 41: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2013.01.008.

- Prno, J., and S. Slocombe. 2012. “Exploring the Origins of ‘Social License to Operate’ in the Mining Sector: Perspectives from Governance and Sustainability Theories.” Resources Policy 37 (3): 346–357. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.04.002.

- Sierra, L., V. Yepes, T. García-Segura, and E. Pellicer. 2018. “Bayesian Network Method for Decision-Making about the Social Sustainability of Infrastructure Projects.” Journal of Cleaner Production 176: 521–534. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.140.

- Silvius, G. 2017. “Sustainability as a New School of Thought in Project Management.” Journal of Cleaner Production 166: 1479–1493. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.121.

- Silvius, G., M. Kampinga, S. Paniagua, and H. Mooi. 2017. “Considering Sustainability in Project Management Decision Making: An Investigation Using Q-Methodology.” International Journal of Project Management 35 (6): 1133–1150. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.01.011.

- Silvius, G., and R. P. J. Schipper. 2014. “Sustainability in Project Management: A Literature Review and Impact Analysis.” Social Business 4 (1): 63–96. doi:10.1362/204440814X13948909253866.

- Tubis, A., S. Werbińska-Wojciechowska, and A. Wroblewski. 2020. “Risk Assessment Methods in Mining Industry—A Systematic Review.” Applied Sciences 10 (15): 5172. doi:10.3390/app10155172.