ABSTRACT

Conceptualisations of well-being show cultural variations. In Ghana, traditional culture emphasises collectivistic values. However, the growth of Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity has dispersed individualistic values, which may be even more pronounced in emerging adults. The aim of the current study was to explore how Ghanaian Pentecostal Charismatic Christian university students conceptualise well-being. Twelve participants belonging to different religious groups within Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity were interviewed. The interviews were then analysed with inductive thematic analysis. The results showed that the participants’ aspirations were situated in a social context with mutual dependence. They experienced well-being by contributing to family, friends, and society at large. However, at times there would be conflicts between their individual strivings and the wishes of others. Collectivistic and individualistic values seemed to have coexisted and interplayed, possibly with a stronger emphasis on traditional collectivistic values than those individualistic values transmitted through Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity.

Well-being consists of six dimensions (Ryff, Citation1989, Citation2018): self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. However, the relative emphasis and content of these dimensions may vary across cultures (Henrich et al., Citation2010; Muthukrishna et al., Citation2020). In Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic (also known as WEIRD) contexts, such as countries in North America and Western Europe, conceptualisations of well-being are imbued with individualistic values and revolve around the idea of an independent self (Ferraro & Barletti, Citation2016; Henrich et al., Citation2010; Muthukrishna et al., Citation2020).

Individualistic values are less prominent outside WEIRD contexts (Muthukrishna et al., Citation2020). Ghana is a country where traditional culture emphasises collectivistic values (Hofstede Insights, Citation2020) and the idea of an interdependent self, where the self in relation to others is the focus of the individual’s experience (Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991; Oyserman et al., Citation2002).

In line with this, previous research showed that Ghanaian conceptions of well-being focus on harmony in social relationships and on fulfilment of social obligations, in the household, at work, or to God (Fadiji et al., Citation2019; Osei-Tutu et al., Citation2020; Suh & Oishi, Citation2002). In this sense, well-being is primarily associated with social units rather than with the individual (Elliott et al., Citation2017; Ferraro & Barletti, Citation2016; Kangmennaang & Elliott, Citation2018; Steele & Lynch, Citation2013). An important part of harmony in social relationships is the idea of reciprocity and generosity, that well-being is related to giving, rather than being dependent on what is received from others (Fadiji et al., Citation2019; Tsai & Dzorgbo, Citation2012).

However, recent changes in religiosity have introduced individualistic values also to Ghana (World Bank, Citation2019; Yirenkyi, Citation1999). One example is Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity that emerged from evangelism and started to spread through West Africa during the 1980s (Asamoah-Gyadu, Citation2020). It is now one of the fastest-growing religions in Ghana (Dovlo, Citation2004; Kalu, Citation2008; Sarbah et al., Citation2020), and constitutes the largest religious group in the country with 31.6% of the Ghanaian population (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021). This strand of Christianity emphasises autonomy and personal growth (Freeman, Citation2015), aspects of well-being that some researchers have argued are associated with individualistic values (Asamoah-Gyadu, Citation2020; Iyengar & Lepper, Citation1999; Komolova & Lipnitsky, Citation2018; Ryff, Citation1995, Citation2018). More specifically, Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity preaches the prosperity gospel that emphasises redemption and prosperity on an individual level (Asamoah-Gyadu, Citation2020; Köhrsen, Citation2015; Lauterbach, Citation2017). The movement fosters members toward becoming proactive and goal oriented with regards to their own lives (Lauterbach, Citation2017; Van Dijk, Citation2012), and to believe that they can improve their lives as individuals with hard work and deeply felt prayer (Freeman, Citation2015). Salter and Adams (Citation2012) also argued that the Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity affects social structures by focusing more on nuclear family and marriage rather than kinship networks.

Pentecostal Charismatic Christian Ghanaians thus navigate between the collectivistic values in traditional Ghanaian culture, and the individualistic values usually found in WEIRD contexts, transmitted to them through their religion (Assimeng, Citation1999; Dovlo, Citation2004; Kalu, Citation2008; Vondey, Citation2014). It has been argued that this may create a tension in members between inconsistent goals (Dovlo, Citation2004; Fadiji et al., Citation2019; Kalu, Citation2008; Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991; Oyserman et al., Citation2002).

This tension may be even more pronounced in young members of Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity. Emerging Adulthood refers to a developmental period that spans from age 18 up to 29 (Arnett, Citation2000). It is characterised by developmental challenges that include identity exploration, making important vocational decisions, and dealing with a new found independence from family (Arnett, Citation2000). This developmental period is also characterised by high rates of psychiatric problems, especially in college settings (Auerbach et al., Citation2016), which is partly explained by the difficulties some emerging adults face in dealing with developmental challenges and finding a smooth transition to adult life (Baggio et al., Citation2015; Lisha et al., Citation2014). Although not as extensively studied, the same difficulties in dealing with developmental challenges may also lead to detrimental effects on psychological well-being (Baggio et al., Citation2017). Indeed, Ofori et al. (Citation2018) found that academic stress in final year Ghanaian university students was associated with decreased quality in interpersonal relationships and reduced psychological well-being.

Pentecostal Charismatic Christians embrace both collectivistic and individualistic values, which should have implications for how they think about well-being. The tensions between these two sets of values may also be even more pronounced in young members of the church. For this reason, the aim of the current study was to explore how Ghanaian Pentecostal Charismatic Christian university students conceptualise well-being.

Method

Participants and recruitment

We recruited a sample of 12 participants from the student population at the University of Ghana (). This is a public university with a broad educational programme situated in Accra. To be included, the participants had to be 18 years or older, fluent in English, and members of a Pentecostal Charismatic Christian Church. Nine of the participants were recruited through Pentecostal student organisations at the University of Ghana (i.e., convenience sample) and three participants were recruited by students and university employees passing on contact information to friends (i.e., snowball sampling).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the samplea (N = 12).

Data collection

We did semi-structured interviews based on an interview guide constructed by the research team. The interviews investigated the participants’ narratives on their experience of well-being, i.e., the research question. Three areas of life were included in the interview guide for exploration: family, education, and spare time. These areas were thought to cover most of the participants’ lives and to be important to well-being (Addai et al., Citation2014; Kangmennaang & Elliott, Citation2019; Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991; Oyserman et al., Citation2002; Yankholmes & Lin, Citation2012). To avoid abstract, general, and socially desirable answers, participants were continuously asked for concrete examples and situations in which they experienced well-being. Questions about religious participation were asked in the beginning of the interview to prime the participants to think about well-being within a religious framework. The interviews were conducted in English on the University of Ghana campus, and each interview lasted for about 50 min.

Data analysis

The analysis was conducted with an inductive thematic approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). In thematic analysis, researchers look for patterns (i.e., themes) in the participants’ narratives (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). We chose an inductive approach to minimise the risk of biases coming from researchers’ preconceptions.

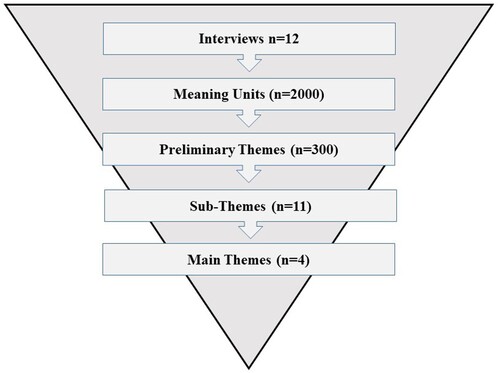

We followed the steps recommended by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). In the first step, the interviews were transcribed verbatim. In the second step, the transcriptions were sorted into meaning units (n = 2000), that is, small sections of sentences relevant to the research question. The meaning units were summarised with one or a few key words (“codes”). We strived to keep the names of the meaning units as close to the participants answers as possible to ensure objectivity. For example, the meaning unit “I shouldn't dress in a certain way that makes me look odd” was given the code name “Shouldn’t dress odd”.

In the third step, meaning units with similar content were grouped into preliminary themes (n = 300), e. g., the meaning units named “need to control emotions”, “can’t be overly angry” and “important to control emotions” were categorised together into the preliminary theme “Control emotions”.

In the fourth step, the preliminary themes were sorted into eleven sub-themes. For example, the preliminary themes “Manners are important”, “Dress appropriately” and “Learn to adapt” were grouped together into the sub-theme “Fitting in”. In the fifth step, the eleven sub-themes were grouped into four main-themes. For example, the sub-themes “Learning” and “Being active” were sorted into the main-theme “Advancing in many areas”. We then assessed that we had reached theoretical saturation (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) and that there was no need for more themes. shows an overview of the data analysis process.

The researchers’ preconceptions

The study was carried out by LP and SH, under supervision by JN, JC, and AO-T. Both LP and SH were masters students at the psychology programme at Örebro University in Sweden. Both had grown up in Sweden, a secular state with a culture based on Christian values and practices, but they had no personal involvement in religious practices. Neither had previously visited Ghana nor studied cultural psychology but did familiarise themselves with Ghanaian culture as well as research on well-being prior to data collection. JC and JN are Swedish PhD-level psychologists with experience from qualitative research, and some previous experience from research on well-being and cross-cultural psychology. Both identified as atheists. AO-T is a PhD-level counselling psychologist, who has lived most of her life in Ghana as a Christian. AO-T has relevant experience from cultural psychology.

Ethical considerations

The study was ethically approved by the Ethics Committee for the Humanities at University of Ghana (registration number ECH 046/18-19) and by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (registration number 2019-01926). Participants consented to participate in the study after receiving information orally and in writing about purpose and process. Participants were informed that the result of the study would be on a group level. Participants were offered confidentiality and the right to withdraw their participation from the study within a 30-day period.

Results

Main theme 1: advancing in many areas

The participants said that their well-being benefitted from expanding their horizons and gaining new experiences. The learning they did through the courses at university were important in this regard. One participant said that: “ … it depends on how you see things and also your perception of others, and education changes perception. You get it? So anytime I get to know that I’m being educated I feel happy because the future is bright basically”. Participants also said that activities during their spare time, such as watching movies, reading, and listening to preaching, contributed to their well-being by expanding their horizons.

Participants also wanted to gain status. Receiving an education by going to the University was an important way to get higher status. The learning they did at the university or in their spare time also provided them with skills and knowledge that they needed to be successful. One participant said that: “ … your social status speaks a lot, if you are not educated in my community nobody respects you”. Participants also said that friends contribute to their status, and they were for that reason chosen carefully. Family members often advised on the type of friends they should associate with. Intelligence and a sense of responsibility were mentioned as desirable qualities in friends.

Further, participants expressed a need for success. Indeed, the participants’ minds were not only set on the present, but also on the future, and they wanted to take every opportunity to prepare for it. Often these goals were related to dreams of financial stability and a good life. As one participant described it: “ … I already have my goals and the more, the higher I get and the closer I get to reaching my goals the better I feel my well-being is being achieved”.

Main theme 2: the value of reciprocity

Participants considered relationships essential to their well-being, not only with family, but also with friends and God. Relationships contributed to well-being by having others to care for them, both emotionally, spiritually, and financially. Other people contributed to the participants’ well-being by providing emotional support and checking up on them. One participant said:

… making sure I’m okay, I’m not in need of something like anything I’m in need of something even if she doesn’t have she tries her personal best to make me feel okey, make me feel comfortable so like I can be able to feel freely with my peers and everybody. So she is always there when I need her.

Relationships also made the participants feel like they were part of a greater social whole. The thought of being cut out of that greater social whole, to become alone, was for many a dreaded scenario. They needed to relate to and connect with other people, to spend time and have fun together. Life without friendship would be lonely. One participant said:

It’s important because if you are going through something and you don’t have good friends around you to talk to, or if you don’t have good friends to make you feel okey you’ll always be depressed. You will feel depressed because there is no one to talk to.

… you can’t just decide to do things your own way because you feel that’s fine, it’s your life. As much as it’s your life in a certain direct or indirect way you affect someone in a long way, and you should be able to check that it’s very important.

… you can’t just decide to do things your own way because you feel that’s fine it’s your life. As much as it’s your life in a certain direct or indirect way you affect someone in a long way and you should be able to check that it’s very important.

Main theme 3: who’s in charge?

Participants said they wanted to be able to make decisions independently and to express their own opinions. For example, they wanted to be allowed to decide which university courses or churches to attend. This independence was thought to be essential to their well-being. Independently made decisions were thought to provide the energy and motivation needed to be successful. For this reason, independent educational decisions were thought to be a facilitating factor for learning. One participant said:

… when whatever you chose, it goes in accordance with what you want, and it makes it easy to learn. That’s something I know, because most people that got forced to do things they didn’t want even if some of them got the skills they are able to learn it, practicing it is very difficult for them. Yes. They do it but they don’t have the heart in it, they do it because maybe it’s a requirement for them.

I am an adult, so I need to learn how to do things on my own. It’s important for me. So once I have learned all these things and acquired all this knowledge I can be able to do everything on my own.

She is there for me … she is always there to try to let you know “you can do better” like “you can do more, there is more to achieve. Don’t just stay where you are, like there are greater heights to get to so just push through”. So, for me she is amazing that’s what I say.

Main theme 4: dealing with society’s demands

The participants said that their well-being depended on them conforming to the norms of Ghanian society. Some norms concerned religion, such as praying and attending church services regularly. Other norms concerned how to behave in every-day life, such as dressing appropriately. One thing that stood out was how important the participants thought it was to always be in control of their emotions. This was because showing too much emotion was thought to increase the risk of breaking unwritten social rules. One participant explained it in this way:

It has to be moderate, that’s how the world is supposed to be like. Everything has to be moderate, you don’t have to be excessively overjoyed, excessively happy, excessively in love, excessively angry. Anything has to be in a reasonable state, not something that would at the end cause you harm or cause you regret.

Failing to conform to norms would also reflect badly on their families, since it was the family’s responsibility to teach them about what is prudent as they grew up. One participant said:

Yeah, the values are far more important than anything. I think values are far more important than money … in my opinion. For instance, if the family says that they provide money for us there wouldn’t be anything to look up to because if they give you money today I will spend it today and tomorrow it is no more. But the values my family have taught me are for life, they are with me. But I think the family is really a very, very important institution, because it’s the first, how do you call it, eh, encounter with socialization in the life of the African child.

So all the values, all that they need to live to be able to, how do you call it, live among diverse groups of people without being seen as a radical or being seen in a weird manner, it is a demean of the family.

Discussion

The present study investigated how Pentecostal Charismatic Christian university students in Ghana experience well-being. The results showed that individual pursuits were expressed in a social context with acute awareness of mutual dependence. At times there were conflicts between the individual’s strivings and the wishes of others that had negative effects on well-being.

Main theme 1 (“Advancing in many areas”) corresponds to Ryff’s concepts of personal growth and environmental mastery (Ryff, Citation1989, Citation2018). Such ideas are thought to be related to Western individualistic values (Komolova & Lipnitsky, Citation2018; Ryff, Citation1995, Citation2018), and it is possible that the participants were encouraged to embrace them through their affiliation with Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity (Freeman, Citation2015; Köhrsen, Citation2015; Van Dijk, Citation2012). Also, the participants were enlisted university students currently undertaking training, and were for that reason in a social context where learning was expected.

However, the participants in this study expressed thoughts about advancement that took their relational framework into account, as revealed in main theme 2 (“The value of reciprocity”). Strong focus on social relationships constitutes the foundation of collectivistic cultures, where individuals are concerned with maintaining an interdependent self, meaning that the self in relation to others is the focus of the individual’s experience, rather than uniqueness found in Western contexts (Hofstede Insights, Citation2020; Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991; Oyserman et al., Citation2002). This theme resembles Ryff’s concept of a need for positive relations with others (Ryff, Citation1989, Citation2018), that focuses on the ability to create warm and trusting relationships. In Self Determination Theory, this dimension has been developed to also include dependence on others (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Deci et al., Citation2001), which reflects some of the content in our main theme 2.

This theme also includes the participants’ dependence on support from others, such as payment of food and school fees, possibly resulting from the relatively weak Ghanaian social protection network (McCauley, Citation2014). However, there was one notable difference between the Pentecostal Charismatic Christian participants in this study and the traditional African culture with regards to relationship patterns: In traditional African culture, family formation consists of wide networks of kins. Much like Pentecostal Charismatic Christians in general (Salter & Adams, Citation2012), our participants focused mainly on the close, nuclear family.

The participants appreciated being able to express their own opinions and make their own decisions, as revealed in main theme 3 (Who’s in charge?). This is similar to Ryff’s concept of autonomy (Citation1989, Citation2018), which is thought to be a product of Western, individualistic values (Komolova & Lipnitsky, Citation2018). Such values may have been transmitted to our participants through their affiliation with Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity (Freeman, Citation2015; Van Dijk, Citation2012). Also, our participants were in the developmental phase described as emerging adulthood, that is characterised by developmental challenges related to independence (Arnett, Citation2000).

However, a potential conflict was evident in this theme between the will of the individual and the wishes of the social units they belonged to. Once again, this was most prominently their families, and not extended networks of kin. Sometimes, the participants accepted that they had to prioritise their families’ wishes to their own. This agrees with previous research that showed that Ghanaian conceptions of well-being focus on social harmony (Fadiji et al., Citation2019; Osei-Tutu et al., Citation2018). Indeed, Deci et al. (Citation2001) have developed the idea about autonomy to also include self-determined choices with regards to others (“autonomously interdependent”). To some extent, having the social unit decide was thought to also create well-being for the individual, so the concept of reciprocity also surfaces here. Sedikides and Gebauer (Citation2010) have argued that religiosity is a basic means of self-enhancing to improve psychosocial health and adjusting the self to impress others is more prominent among the devoted religious. In this way, contributing to others in a social unit was also a form of personal growth. But not always: Sometimes the participants felt that their well-being was hampered when they had to carry out demands that were not aligned with their own wishes.

This conflict was further developed in main theme 4 (“Dealing with society’s demands”). This theme is the one that stands out in comparison with hegemonic conceptualisations of well-being. In Ryff’s model (Citation1989, Citation2018), the content of this main theme would correspond to low levels of autonomy, and thus decreased well-being (Ryff, Citation1989, Citation2018). Even though the participants to some extent expressed a need for autonomy, they also thought that adjusting to society’s demands was incremental to their well-being since in this way they would get status and respect. In this way, adjusting to society’s demands was perceived as an autonomous decision that contributed to personal growth. It was also a way to self-enhancement (Sedikides & Strube, Citation1995). This suggests that the concept of autonomy, as defined by Ryff, may not be applicable in a collectivistic country like Ghana.

Limitations

The cultural framework of researchers may influence interpretations of data. In this study, we made sure to include a culturally heterogenous research team to ensure both objectivity and cultural sensitivity. A member check would have further improved validity.

Conclusions

Like participants in previous research on emerging adulthood (Arnett, Citation2000), the participant in this study expressed that their well-being was related to independence and preparing for opportunities in the future. Still, they often experienced well-being through their social engagement, and only occasionally perceived yielding to the social norms and other’s will as detrimental to well-being. The results suggest that collectivistic and individualistic values coexisted and interplayed, possibly with a stronger emphasis on traditional collectivistic values than those individualistic values transmitted through Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity. These results are valuable to bear in mind for psychologists, social workers, and other professionals meeting emerging adults in the Pentecostal churches for counselling services. It is possible that the tension between individualistic and collectivistic values also exist in members of other evangelical churches, and future studies should investigate this. Also, the results may be limited to a public university setting. Future studies should investigate if the results extend to private university settings with more restricted student populations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Addai, I., Opoku-Agyeman, C., & Amanfu, S. K. (2014). Exploring predictors of subjective well-being in Ghana: A micro-level study. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 15(4), 869–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9454-7

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

- Asamoah-Gyadu. (2020). Pentecostalism in Africa: Experiences from Ghana's charismatic ministries. Regnum Books International.

- Assimeng, J. M. (1999). Social structure of Ghana: A study in persistence and change. Ghana Publishing Corporation.

- Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Axinn, W. G., Cuijpers, P., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hwang, I., Kessler, R. C., Liu, H., Mortier, P., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Andrade, L. H., Benjet, C., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., Demyttenaere, K., … Bruffaerts, R. (2016). Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 46(14), 2955–2970. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001665

- Baggio, S., Iglesias, K., Studer, J., & Gmel, G. (2015). An 8-item short form of the Inventory of Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA) among young Swiss men. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 38(2), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278714540681

- Baggio, S., Studer, J., Iglesias, K., Daeppen, J.-B., & Gmel, G. (2017). Emerging adulthood: A time of changes in psychosocial well-being. Health Behavior Etiology and Promotion Among Young Persons, 40(4), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0163278716663602

- Baumeister, R., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201278002

- Dovlo, E. (2004). African culture and emergent church forms in Ghana. Exchange, 33(1), 28–53. https://doi.org/10.1163/1572543041172639

- Elliott, S. J., Dixon, J., Bisung, E., & Kangmennang, J. (2017). A glowing footprint: Developing an index of wellbeing for low to middle income countries. International Journal of Wellbeing, 7(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v7i2.503

- Fadiji, W., Meiring, A. W., & M, L., & Wissing, P. (2019). Understanding well-being in the Ghanaian context: Linkages between lay conceptions of well-being and measures of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(3), 935–935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09777-2

- Ferraro, E., & Barletti, J. (2016). Placing wellbeing: Anthropological perspectives on wellbeing and place. Anthropology in Action, 23(3), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3167/aia.2016.230301

- Freeman, D. (2015). Pentecostalism and economic development in Sub-saharan Africa. In E. Tomalin (Ed.), The routledge handbook of religions and global development (pp. 114–126). Routledge.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). 2021 PHC general report Vol 3C, background characteristics. Sankofa Press Limited.

- Henrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

- Hofstede Insights. (2020). Country comparison tool. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool?countries=ghana*

- Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (1999). Rethinking the value of choice: A cultural perspective on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.349

- Kalu, O. (2008). African Pentecostalism: An introduction. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195340006.001.0001.

- Kangmennaang, J., & Elliott, S. (2018). Towards an integrated framework for understanding the links between inequalities and wellbeing of places in low and middle income countries. Social Science & Medicine, 213, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.002

- Kangmennaang, J., & Elliott, S. J. (2019). ‘Wellbeing is shown in our appearance, the food we eat, what we wear, and what we buy’: Embodying wellbeing in Ghana. Health & Place, 55, 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.12.008

- Komolova, M., & Lipnitsky, J. Y. (2018). “I want her to make correct decisions on her own:” Former Soviet Union mothers’ beliefs about autonomy development. Frontier in Psychology, 8, 2361. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02361

- Köhrsen, J. (2015). Pentecostal improvement strategies: A comparative reading on African and South American Pentecostalism. In A. Heuser (Ed.), Pastures of plenty: Tracing religio-scapes of Prosperity Gospel in Africa and beyond (pp. 49–64). Frankfurt am Main. http://edoc.unibas.ch/dok/A6438701

- Lauterbach, K. (2017). Christianity, wealth, and spiritual power in Ghana. Springer International Publishing.

- Lisha, N. E., Grana, R., Sun, P., Rohrbach, L., Spruijt-Metz, D., Reifman, A., & Sussman, S. (2014). Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Revised Inventory of the Dimensions of Emerging Adulthood (IDEA–R) in a sample of continuation high school students. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 37(2), 156–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278712452664

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

- McCauley, J. (2014). Pentecostalism as an informal political institution: Experimental evidence from Ghana. Politics and Religion, 7(4), 761–787. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048314000480

- Muthukrishna, M., Bell, A. V., Henrich, J., Curtin, C. M., Gedranovich, A., McInerney, J., & Thue, B. (2020). Beyond western, educated, industrial, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) psychology: Measuring and mapping scales of cultural and psychological distance. Psychological Science, 31(6), 678–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620916782

- Ofori, I. N., Addai, P., Avor, J., & Quaye, M. G. (2018). Too much academic stress: Implications on interpersonal relationships and psychological well-being among final year university of Ghana students. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 2(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.9734/AJESS/2018/43193

- Osei-Tutu, A., Dzokoto, V. A., Adams, G., Hanke, K., Kwakye-Nuako, C., Adu-Mensa, F., & Appiah-Danquah, R. (2018). ‘My own house, car, my husband, and children’: Meanings of success among Ghanaians. Heliyon, 4(7), e00696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00696

- Osei-Tutu, A., Dzokoto, V. A., Affram, A. A., Adams, G., Norberg, J., & Doosje, B. (2020). Conceptions of well-being in four Ghanaian languages. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 1798. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01798

- Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

- Ryff, C. D. (1995). Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4(4), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772395

- Ryff, C. D. (2018). Eudaimonic well-being: Highlights from 25 years of inquiry. In K. Shigemasu, S. Kuwano, T. Sato, & T. Matsuzawa (red.) (Eds.), Diversity in harmony–insights from psychology: Proceedings of the 31st international Congress of Psychology (pp. 375–385). John Wiley and Sons.

- Salter, P. S., & Adams, G. (2012). Mother or wife? An African dilemma tale and the psychological dynamics of socio-cultural change. Social Psychology, 43(3), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000124

- Sarbah, E. K., Niemandt, C. J., & White, P. (2020). Migration from historic mission churches to Pentecostal and Charismatic churches in Ghana. Verbum et Ecclesia, 41(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v41i1.2124

- Sedikides, C., & Gebauer, J. E. (2010). Religiosity as self-enhancement: A meta-analysis of the relation between socially desirable responding and religiosity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309351002

- Sedikides, C., & Strube, M. J. (1995). The multiply motivated self. Personality and Social Psychology Bullentin, 21(12), 1330–1335. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672952112010

- Steele, L. G., & Lynch, S. M. (2013). The pursuit of happiness in China: Individualism, collectivism, and subjective well-being during China’s economic and social transformation. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0154-1

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE Publications.

- Suh, E. M., & Oishi, S. (2002). Subjective well-being across cultures. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 10(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1076

- Tsai, M.-C., & Dzorgbo, D.-B. S. (2012). Familial reciprocity and subjective well-being in Ghana. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(1), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00874.x

- Van Dijk, R. (2012). Pentecostalism and post-development: Exploring religion as a developmental ideology in Ghanaian migrant communities. In D. Freeman (Ed.), Pentecostalism and development: Churches, NGOs and social change in Africa (pp. 87–108). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vondey, W. (2014). The unity and diversity of Pentecostal theology – a brief account for the ecumenical community in the West. Ecclesiology, 10(1), 76–100. https://doi.org/10.1163/1745531G-01001006

- World Bank. (2019). The world bank in Ghana: Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ghana/overview on 28/01/2020

- Yankholmes, A. K., & Lin, S. (2012). Leisure and education in Ghana: An exploratory study of university students’ leisure lifestyles. World Leisure Journal, 54(1), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2012.668044

- Yirenkyi, K. (1999). Changing patterns of mainline and charismatic religiosity in Ghana. Research in the Scientific Study of Religion, 10, 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004496224_012