ABSTRACT

Contemporary philosophers have routinely claimed that agnostics, who lack belief that God exists, can nonetheless adopt alternative attitudes toward a supposed God that act as substitutes for belief, and may thereby reap benefits associated with theistic belief. This study tested this hypothesis empirically in an online sample of self-identified agnostics (N = 360). Previous findings that anxious attachment to God is negatively related to agnostics’ well-being while secure attachment to God is positively related to agnostics’ well-being were confirmed and extended. Anxious attachment to God predicted unique variance in life satisfaction, depression, and self-esteem in hierarchical regressions, while difference-in-means tests indicated that securely attached agnostics fared better than their insecurely attached counterparts for these variables. Two novel and more direct measures of agnostics’ acceptance or resistance of God’s supposed love also demonstrated significant associations with agnostics’ gratitude, life satisfaction, and self-esteem, even after controlling for God attachment.

A large body of research links religious participation with well-being (Koenig et al., Citation2012). For instance, daily experiences of religion are positively related to happiness (Ellison & Fan, Citation2008), attending church is related to subjective well-being (Okulicz-Kozaryn, Citation2010), and practising prayer is related to feeling more grateful (Lambert et al., Citation2009). Yet, some researchers have challenged the existence of a linear relationship between religious participation and well-being, instead arguing that the available data supports a curvilinear relationship when atheists and agnostics are considered more carefully (e.g., Galen & Kloet, Citation2011; Uzarevic & Coleman, Citation2021). According to these authors, both confident theists and confident atheists tend to experience greater well-being, while agnostics, who lack both confident belief that God exists and confident belief that God does not exist, suffer a well-being disadvantage.

If agnostics are at risk of a well-being disadvantage, this raises the question of whether and how this risk may be mitigated. One surprising hypothesis comes from contemporary research in philosophy of religion. Several philosophers of religion have argued that while agnostics are standardly understood to lack both belief that God exists and belief that God does not exist (Draper, Citation2022), they can nonetheless adopt alternative positive cognitive attitudes toward a supposed God that can act as substitutes for belief (Alston, Citation1996; Howard-Snyder, Citation2013; Jackson, Citation2022; McKaughan, Citation2016; Schellenberg, Citation2009). Although agnostics do not believe God exists or loves them, they might nonetheless assume that God exists and loves them, or sincerely act as if God exists and loves them, or belieflessly accept God’s existence and love for them, or maintain faith that God exists and loves them. But are these complex attitudes toward God at home only in a philosophical thought experiment, or are there actually real-world individuals who fit this profile? And, if there are such individuals, can it be demonstrated empirically that their belief-substituting attitudes toward God also serve to mitigate the well-being risks associated with their agnosticism? This article is concerned with these questions. Setting aside the question of whether there in fact is a God (and this is why the language of “supposed God” is sometimes used throughout), the paper considers the potential significance of agnostics’ belief-substituting attitudes about God for these individuals’ well-being.

Previous psychological research does identify some measures of religiosity that may not necessarily require belief that God exists but that may be significant for agnostics’ well-being. Even if an agnostic is not presently having any experiences of a supposed God, for instance, they may have had experiences with a supposed God in the past – whether positive or negative. Researchers have found that past negative experiences with God are predictive of present non-belief in God (Exline et al., Citation2015), and that religious/spiritual struggles are related to lower well-being for those who do not believe in God as well as those who do (Sedlar et al., Citation2018).

Likewise, even if agnostics do not believe God exists, they may vary in the way they imagine God (Bradley et al., Citation2015; Exline et al., Citation2015) – as being more loving or more vindictive, for example. Researchers have found that positive images of God are related to greater happiness and life satisfaction (Steenwyk et al., Citation2010), while negative images of God are related to depressive symptoms (Braam et al., Citation2008). While most research on God image has focused on participants who believe that God exists, some research with non-religious participants has found that their image of God is related to problems in their relationships as well (Kosarkova et al., Citation2020).

Perhaps more directly relevant for the research questions of this article is previous research on attachment to God (Kirkpatrick & Shaver, Citation1992). Attachment to God concerns participants’ patterns of relationship toward a supposed God. In particular, researchers have tended to focus on three main attachment orientations: avoidant attachment, which involves resisting dependence upon God and intimacy with God; anxious attachment, which involves worry and concern about the status of one’s relationship with God and jealousy regarding others’ relationships with God; and secure attachment, which involves confidence in God’s support when needed together with an ability to engage one’s environment autonomously given this confidence. While research on God attachment has focused nearly exclusively on theistic participants, a few studies with non-theistic participants have produced significant results, which suggest especially that agnostics’ anxious attachment to God is negatively related to their well-being. For example, Strenger et al. (Citation2016) found that anxious God attachment was related to eating disorder symptoms for non-believing as well as believing participants. Byerly (Citation2022) found that anxious God attachment was significant for agnostics’ depression, while difference-in-means tests revealed secure God attachment to be significant or to trend toward significance for agnostics’ self-esteem and depression in a small sample (N = 120).

While this research suggests that agnostics may be capable of variation in their attachment toward a supposed God and this may be significant for their well-being, it is not clear that existing measures of God attachment capture very well the orientation of someone who positively accepts a supposed God’s love for them in the way envisioned by philosophers of religion. Two measures of God attachment are most frequently used. The 30-item, more emotionally-oriented measure created by Beck and MacDonald (Citation2004) has only two items that mention God’s love (“Sometimes I feel that God loves others more than me” and “I crave reassurance from God that God loves me”). Both of these assess participants’ lack of acceptance of God’s love due to anxious attachment, rather than their positive acceptance of God’s love. The nne-item, more cognitively-oriented measure created by Rowatt and Kirkpatrick (Citation2002) does not mention God’s love explicitly at all. Thus, it might be questioned whether a more direct and overt measure of participants’ beliefless acceptance of God’s love, guided by the conceptualisation provided by philosophers of religion, would provide a better tool for assessing whether agnostics’ acceptance of God’s love via means other than belief is significant for their well-being.

The present research

The objective of this research was to probe in more detail whether agnostics’ acceptance or resistance of a supposed God’s love is related to their well-being. As potential measures of agnostics’ acceptance of God’s love, the researcher employed the two most commonly used measures of God attachment, as well as two newly developed and more direct measures of acceptance or resistance of God’s love guided by philosophical theorising. Outcome measures included several indicators of healthy and unhealthy psychological functioning thought to relate to religiosity – gratitude, satisfaction with life, self-esteem, and depression. Relationships between agnostics’ acceptance or rejection of God’s love, on the one hand, and these indicators of well-being, on the other, were investigated through the use of bivariate correlations, difference-in-means tests, and hierarchical regressions used to control for other variables including demographics, Big Five personality traits, past experiences with God, and God image. Following the predictions of contemporary philosophers of religion, it was hypothesised that acceptance or resistance of God’s love on the part of agnostics would be predictive of well-being indicators. More specifically and in line with previous research, it was hypothesised that agnostics’ anxious attachment to God would relate negatively to agnostics’ well-being, both via bivariate correlations and in hierarchical regressions; and that securely attached agnostics would emerge as experiencing greater well-being than anxiously or avoidantly attached agnostics as demonstrated through difference-in-means tests. The theoretical hypothesis that acceptance or resistance of God’s love may predict even further variance in agnostics’ well-being beyond agnostics’ God attachment was also investigated. The study was ethically approved in accordance with the review policies of the University of Sheffield.

Method

Participants

Three hundred sixty participants completed an online survey in June 2022, after giving informed consent. Participants were recruited using Qualtrics’ panelist service and received Qualtrics’ standard rate as payment. A minimum completion time of six minutes, one-half of the soft-launch median completion time, was used to ensure that participants were responding thoughtfully. All participants were US residents. The sample contained 260 (73%) participants who identified as female and 98 who identified as male. Two hundred ninety-five participants identified as White, 18 as Black or African American, and fewer than 10 for any other racial or ethnic category. All participants were 18 or older, with 14% between 18 and 25, 18% between 26 and 35, 17% between 36 and 45, 18% between 46 and 55, 16% between 56 and 65, and 17% older than 65. All participants responded to the question “Which of the following best characterises your views about God?” with the answer “Agnostic: I neither believe God does exist nor believe God doesn’t exist” rather than “Theist: I believe God exists” or “Atheist: I believe God does not exist”. The supplementary data file contains responses from 315 participants who consented to their data being shared beyond the research team.

Materials

Participants completed several previously developed measures along with two newly developed measures and some individual questions. While participants were allowed to skip any question, this very rarely occurred. The previously developed measures included Beck and MacDonald’s (Citation2004) 28-item measure of anxious (α = .92) and avoidant (α = .83) God attachment and Rowatt and Kirkpatrick’s (Citation2002) nine-item measure of anxious (α = .79) and avoidant (α = .83) God attachment, described in the introduction. Participants were instructed to rate their agreement or disagreement with statements about their experiences with God or how God seems to them, respectively. They also completed a Rasch-derived 10-item short form of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (Cole et al., Citation2004; α = .9), the 10-item Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, Citation1965; α = .92), and the five-item Satisfaction With Life Scale (Deiner et al., Citation1985; α = .85). Participants completed the Values-in-Action Scale (Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004) for the virtue of gratitude (α = .84). They completed a 10-item measure of Big Five personality traits for agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness (Rammstedt & John, Citation2007). And participants completed the God-10 (Exline et al., Citation2015) – a measure of how they imagine God as being, whether kind (α = .96), cruel (α = .93), or distant (α = .92).

Participants’ past experiences with God were assessed using variations of the question “Looking back over your life, how often have you … ?” with the ellipsis filled in by “had positive feelings toward God”, “felt angry at God”, “believed that God was angry at you”, and “had doubts about God’s existence” (Exline et al., Citation2015). Participants answered separate questions asking how important religion and spirituality are for them. They were asked to assess to what extent their evidence supports God’s existence or non-existence using a sliding bar with 50 representing their evidence offering exactly as much support for God’s existence as for God’s non-existence, 100 representing their evidence conclusively supporting God’s existence, and 0 representing their evidence conclusively supporting God’s non-existence.

One newly developed measure aimed to assess to what extent participants accept God’s supposed love in a way that does not require them to believe that God exists and loves them. To create this measure, the researcher used the most commonly employed phrases in the contemporary philosophy of religion literature to express this attitude toward God’s love. Thus, participants rated their agreement with the items “I hope that God really loves me”, “I accept that God really loves me”, “I have faith that God really loves me”, “I assume that God really loves me”, and “I act as if God really loves me” (α = .92). A second newly developed measure used a similar procedure to capture an opposed, more doubtful and resistant orientation toward God’s love. Participants rated their agreement with the items “I doubt that God really loves me”, “I question whether God really loves me”, “I dispute whether God really loves me”, “I challenge whether God really loves me”, and “I dismiss whether God really loves me” (α = .89). The supplementary data file contains the responses from 315 participants who agreed for their data to be shared beyond the immediate research team.

Procedures

Bivariate correlations were calculated for the variables measured, focusing on the relationships that God attachment and acceptance and resistance of God’s love had to other variables.

A new categorial variable was created to compare participants’ attachment orientations toward God for purposes of conducting difference-in-means tests. Secure attachment to God was operationalised as scoring below the 40th percentile for both anxious and avoidant God attachment, while avoidant and anxious God attachment were operationalised as scoring above the 60th percentile in each of these, following the procedure employed by (Njus & Sharmer, Citation2020). A series of one-way ANOVAs was performed using attachment security as independent variable and satisfaction with life, depression, and self-esteem as dependent variables. In cases where the ANOVA revealed significant between-group differences, a Tukey HSD test was undertaken to compare each group with the others in order to determine which comparisons were significant. Group means for the dependent variables are reported.

A series of three-step hierarchical regression procedures was then used to determine the potential unique contribution to well-being indicators made by God attachment and acceptance and resistance of God’s love. At step one, age and sex, importance of religion and spirituality, God image, evidence for God, and past experiences with God were entered as predictors. At step two, God attachment was added as a predictor. And, at step three, accepting and resisting God’s love were added as predictors. This procedure was repeated with gratitude, satisfaction with life, depression, and self-esteem as dependent variables.

Results

provides key bivariate correlations. God anxiety and God avoidance were negatively related both within and across the two scales used for God attachment. God anxiety was positively related to both accepting and resisting God’s love, while God avoidance related negatively to accepting and positively to resisting God’s love. Accepting and resisting God’s love are negatively related to each other, though the relationship is small.

Table 1. Key Bivariate Correlations.

In terms of their relationships to other variables, God anxiety and God avoidance tended to exhibit opposing or at least divergent relationships, especially where one had at least a moderate relationship with the variable in question. This included their relationships to importance of religion and spirituality, God image, evidence for God, past positive experiences with God and doubts about God, and the well-being indicators of satisfaction with life, depression, and self-esteem. Generally, the Beck and MacDonald (Citation2004) measure of anxious God attachment had larger relationships to other variables than did the Rowatt and Kirkpatrick measure of anxious attachment, including its relationship to focal well-being indicators. Differences between the Beck and MacDonald (Citation2004) measure of avoidant God attachment and the Rowatt and Kirkpatrick (Citation2002) measure of the same were less pronounced.

Like anxious and avoidant attachment, accepting and resisting God’s love tended to relate to other variables in opposed or divergent ways, with acceptance of God’s love relating to positive well-being indicators (or relating negatively to negative well-being indicators) and resistance of God’s love relating to negative well-being indicators (or relating negatively to positive well-being indicators). Accepting and resisting God’s love also related differently and in accordance with theoretical expectations to variables such as importance of religion and spirituality, God image, evidence for God, and past experiences with God, providing some support for the validity of these new scales. For instance, accepting God’s love was significantly related to importance of religion and spirituality and evidence for God, while resisting God’s love was not; and accepting and resisting God’s love exhibited significant and opposed relationships to cruel, kind, and distant God image. Accepting and resisting God’s love showed somewhat stronger relationships to the generally positive (e.g., agreeableness and conscientiousness) and negative (i.e., neuroticism) Big Five personality attributes than did God anxiety and God avoidance.

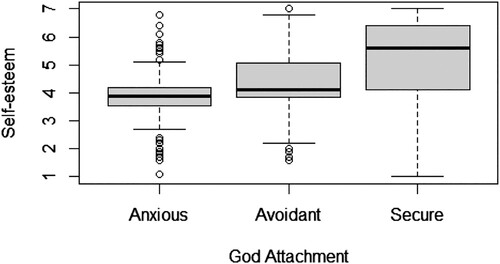

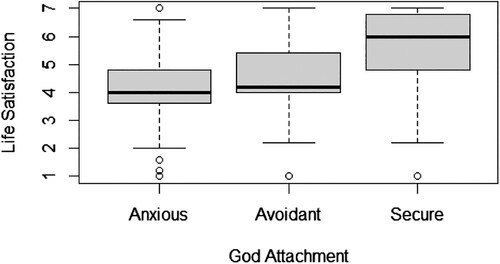

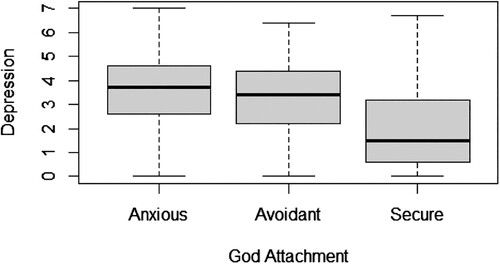

Operationalising avoiant, anxious, and secure attachment led to the formation of groups with 138, 138, and 118 members respectively, with some participants not being included in one of these groups. One-way ANOVA tests revealed significant results for the relationship between attachment security and self-esteem, life satisfaction, and depression, all at the p < .001 level. Tukey HSD tests revealed that the difference in means for self-esteem were significant between all three pairs of groups, while the difference in means for life satisfaction and depression were significant between secure and avoidant and secure and anxious groups but not between avoidant and anxious groups. The pattern of results, graphically represented in , suggests that agnostics with secure God attachment are significantly better off with respect to these well-being indicators than their comparison groups.

The hierarchical regressions yielded significant results as well, particularly for anxious God attachment as measured by the Beck and MacDonald (Citation2004) instrument and for accepting God’s love (). Anxious God attachment predicted additional variance beyond the variables included in Step 1 for life satisfaction, self-esteem, and depression. Accepting God’s love predicted additional variance at Step 3 for gratitude, life satisfaction, and self-esteem, but not depression. Avoidant God attachment predicted additional variance at Step 2 for depression and was near-significant at Step 3 for self-esteem, being negatively related the former and positively related to the latter. This raises an interpretive question, discussed below, about why accepting God’s love might be generally positive for well-being while avoiding God might also be positive to some extent. Resisting God’s love did not predict additional variance in any dependent variable at Step 3, though it was near-significant for self-esteem.

Table 2. Accepting God’s love predicting additional variance in gratitude.

Table 3. Anxious God attachment and Accepting God’s love predicting additional variance in life satisfaction.

Table 4. Anxious God attachment and Accepting God’s love predicting additional variance in self-esteem.

Table 5. God attachment predicting additional variance in depression.

It is important when considering these results to keep in mind that seventeen predictor variables are included at Step 1. Generally speaking, for any dependent variable, between five to ten of the total predictor variables was significant, with the beta coefficients for anxious God attachment and acceptance of God’s love being at or above the mean in size among these. As a point of comparison, the unique contribution of anxious God attachment or acceptance of God’s love was often comparable to the unique contribution of variables such as age, neuroticism, or conscientiousness.

General discussion

Philosophical research has suggested that agnostics, who lack belief that God exists, may nonetheless adopt alternative cognitive attitudes toward a supposed God, such as assuming that God exists and loves them, which may be significant for agnostics’ well-being (Alston, Citation1996; Howard-Snyder, Citation2013; Jackson, Citation2022; McKaughan, Citation2016; Schellenberg, Citation2009). The present research is the most thorough empirical test of this proposal to date. Existing measures of attachment to God as well as novel measures of accepting and resisting God’s love were investigated to consider their potential significance for agnostics’ well-being, using bivariate correlations, difference-in-means tests, and hierarchical regressions.

Results generally confirmed that accepting God’s supposed love is positively related to indicators of agnostics’ well-being. Acceptance of God’s love was positively correlated with indicators of well-being and negatively correlated with indicators of ill-being, while resisting God’s love and anxious God attachment were negatively correlated with indicators of well-being and positively correlated with indicators of ill-being. Difference-in-means tests revealed that agnostics with secure attachment to God had significantly higher self-esteem and life satisfaction and significantly lower depression than their counterparts with avoidant or anxious God attachment. Hierarchical regressions demonstrated that anxious God attachment predicts additional variance in life satisfaction, self-esteem, and depression when controlling for several other variables, while accepting God’s love predicts additional variance in gratitude, life satisfaction, and self-esteem when controlling for these same variables along with God attachment.

These results are consistent with previous findings that God attachment – particularly anxious God attachment – is significant for non-theists’ well-being, being related to lower well-being in much the way that it is for theists (Byerly, Citation2022; Strenger et al., Citation2016). They extend these findings by providing more compelling evidence for the significance of secure God attachment for agnostics’ well-being, and also by showing that accepting God’s love can be measured independently of existing measures of God attachment and is predictive of additional variance in agnostics’ well-being beyond these measures of God attachment. Individuals who neither believe that God exists nor believe that God does not exist but who are also more secure in their attachment relationship toward a supposed God and more accepting of this God’s love for them may experience greater well-being than their counterparts.

The study’s findings pertaining to avoidant God attachment are more difficult to interpret. On the one hand, the Beck and MacDonald (Citation2004) instrument for measuring avoidant God attachment was positively correlated with life satisfaction and negatively correlated with depression, and it also predicted additional variance in depression and was near-significant for self-esteem when controlling for other variables in multiple regressions. One might speculate that these results could be due to a positive relationship between avoidant God attachment and independence, autonomy, or self-reliance among agnostics. On the other hand, the difference-in-means tests revealed that individuals who scored above the 60th percentile in avoidant God attachment were significantly worse off than their securely attached counterparts who scored below the 40th percentile in both avoidant and anxious God attachment. The former findings may seem not to fit well with the evidence of the study that accepting God’s love is positively related to agnostics’ well-being, since it would seem that accepting God’s love would involve not avoiding God. The latter findings would seem to fit better with the findings of this study regarding accepting God’s love, since acceptance of God’s love would seem to cohere well with having a secure attachment with God. Indeed, it seems an open question whether the newly created measure of acceptance of God’s love provides a different way of measuring secure God attachment or some facet of it, rather than measuring a distinct phenomenon.

These findings may make more sense when the items used to measure avoidant God attachment are considered more carefully. When these items are considered, it seems that what they capture most clearly is avoiding an emotionally intense relationship with God. Items such as “My experiences with God are very intimate and emotional” or “It is uncommon for me to cry when sharing with God” (both reverse scored) indicate an emotionally intense relationship with God. Yet, emotionally intense relationships do not equate to securely attached relationships, or healthy relationships more generally. It may be that some agnostics who do not avoid God do so only by having an emotionally intense relationship with God that is not healthy. In this way, avoiding God may be better than not avoiding God for some. But, better than either of these options may be having a secure attachment to God and accepting God’s love.

If forming a secure attachment with a supposed God and accepting this God’s love for oneself is related to better well-being for agnostics, this finding may be particularly important given research which suggests that agnostics may suffer a well-being deficit in comparison to both theists and atheists (Galen & Kloet, Citation2011; Uzarevic & Coleman, Citation2021). One possibility for the agnostic which may mitigate potential dangers to their well-being related to agnosticism is to engage in a positive relationship with a supposed God that does not require belief.

Limitations

This study is limited in several ways. It relies exclusively on self-reports as indicators of agnostics’ attachment to God, acceptance of God’s love, and well-being. Future studies could employ alternative methods for measuring these variables, such as an attachment to God interview (Proctor et al., Citation2009). This study is also cross-sectional and so does not indicate a causal relationship between the variables. Previous research does suggest that secure attachment to God may be causally related to improved well-being, at least for theists (Ellison et al, Citation2012). Future research with agnostics using longitudinal designs could help to confirm whether this is true in their case as well. The fact that the newly developed measures for accepting and resisting God’s love related as theoretically expected to various other variables provides some informal validation for these scales; however, it is a limitation of the study that the newly developed measures for accepting and resisting God’s love had not received previous, independent validation. While the study controlled for several variables, it did not examine whether God attachment or accepting God’s love predicts additional variance in agnostics’ well-being beyond what is predicted by their attachment relationships to other attachment figures, such as parents or romantic partners. Previous studies have found that for theists God attachment is uniquely significant beyond parental and romantic attachment (e.g, Keefer & Brown, Citation2018; Njus & Sharmer, Citation2020); it would be desirable to test this hypothesis with agnostics as well. The sample used in this study is also limited, being restricted to participants from the United States and primarily to participants who identify as White. Future research should examine whether the findings reported here hold for other populations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alston, W. (1996). Belief, acceptance, and religious faith. In J. Jordan & D. Howard-Snyder (Eds.), Faith, freedom, and rationality (pp. 3–27). Rowman and Littlefield.

- Beck, R., & MacDonald, A. (2004). Attachment to God: The Attachment to God Inventory, tests of working model correspondence, and an exploration of faith group differences. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 32(2), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164710403200202

- Braam, A. W., Jonker, H. S., Mooi, B., De Ritter, D., Beekman, A. T., & Deeg, D. J. (2008). God image and mood in old age: Results from a community-based pilot study in The Netherlands. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 11(2), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670701245274

- Bradley, D. F., Exline, J. J., & Uzdavines, A. (2015). The god of nonbelievers: Characteristics of a hypothetical god. Science, Religion and Culture, 2(3), 120–130. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.src/2015/2.3.120.130

- Byerly, T. R. (2022). The transformative power of accepting God’s love. Religious Studies, 58(4), 831–845. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034412521000408

- Cole, J. C., Rabin, A. S., Smith, T. L., & Kaufman, A. S. (2004). Development and validation of a Rasch-derived CES-D short form. Psychological Assessment, 16(4), 360–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.360

- Deiner, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Draper, P. (2022). Atheism and agnosticism. In E. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Available at Atheism and Agnosticism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/

- Ellison, C. G., & Fan, D. (2008). Daily spiritual experiences and psychological well-being among US adults. Social Indicators Research, 88(2), 247–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9187-2

- Ellison, C. G., Mradshaw, M., Kuyel, N., & Marcum, J. P. (2012). Attachment to God, stressful life events, and changes in psychological distress. Religious Research Association, 53(4), 493–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-011-0023-4

- Exline, J. J., Grubbs, J. B., & Homolka, S. J. (2015). Seeing God as cruel or distant: Links with divine struggles involving anger, doubt, and fear of God’s disapproval. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 25(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2013.857255

- Galen, L. W., & Kloet, J. (2011). Mental well-being in the religious and the non-religious: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14(7), 673–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2010.510829

- Howard-Snyder, D. (2013). Propositional faith: What it is and what it is not. American Philosophical Quarterly, 50(4), 357–372. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24475353

- Jackson, E. (2022). Faith, hope, and justification. In L. R. G. Oliveira & P. Silva (Eds.), Propositional and doxastic justification (pp. 201–216). Routledge.

- Keefer, L., & Brown, F. (2018). Attachment to God uniquely predicts variation in well-being outcomes. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 40(2), 225–257. https://doi.org/10.1163/15736121-12341360

- Kirkpatrick, L. A., & Shaver, P. R. (1992). An attachment-theoretical approach to romantic love and religious belief. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167292183002

- Koenig, H. G., King, D. E., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health (2nd ed). Oxford University Press.

- Kosarkova, A., Malinakova, K., van Dijk, J. P., & Tavel, P. (2020). Childhood trauma and experience in close relationships are associated with the God image: Does religiosity make a difference? International Journal for Environemental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238841

- Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., Braithwaite, S. R., Graham, S. M., & Beach, S. R. H. (2009). Can prayer increase gratitude? Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 1(3), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016731

- McKaughan, D. (2016). Action-centered faith, doubt, and rationality. Journal of Philosophical Research, 41(9999), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.5840/jpr20165364

- Njus, D. M., & Sharmer, A. (2020). Evidence that God attachment makes a unique contribution to psychological well-being. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 30(3), 178–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2020.1723296

- Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. (2010). Religiosity and life satisfaction across nations. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 13(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670903273801

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

- Proctor, M., Minder, M., McLean, L., Devenish, S., & Bonab, B. G. (2009). Exploring christians’ explicit attachment to God representations: The development of a template for assessing attachment to God experiences. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 37(4), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164710903700402

- Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

- Rowatt, W. C., & Kirkpatrick, L. A. (2002). Two dimensions of attachment to God and their relation to affect, religiosity, and personality constructs. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41(4), 637–651. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5906.00143

- Schellenberg, J. (2009). The will to imagine: A justification of skeptical religion. Ithaca.

- Sedlar, A. E., Stauner, N., Pargament, K. I., Exline, J. J., Grubbs, J. B., & Bradley, D. F. (2018). Spiritual struggles among atheists: Links to psychological distress and well-being. Religions, 9(8), 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9080242

- Steenwyk, S. A. M., Atkins, D. C., Bedics, J. D., & Whitley, B. E. (2010). Images of God as they relate to life satisfaction and hopelessness. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 20(2), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508611003607942

- Strenger, A., Schnitker, S., & Felke, T. (2016). Attachment to God moderates the relation between sociocultural pressure and eating disorder symptoms as mediated by emotional eating. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 19(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2015.1086324

- Uzarevic, F., & Coleman, T. J. (2021). The psychology of nonbelievers. Current Opinion in Psychology, 40, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.08.026