ABSTRACT

The study aimed to investigate stigma toward women with serious mental illness (SMI) within the Jewish Ultraorthodox community. It explored the impact of target motherhood, observers’ parenthood, and psychological-flexibility on stigma. 150 participants were presented with a vignette depicting a woman with\without SMI and as mothers\non-mothers, then surveyed for their attitudes and social distance. High levels of stigma were found toward women with SMI regardless of their motherhood status. Interestingly, observers’ parenthood correlated with increased social distance, and high psychological flexibility was linked to lower stigma. A third-level interaction was found in which there was a moderating effect of psychological flexibility on the interaction between target person’s motherhood, target person’s SMI, and stigma. The study highlights the need for culturally sensitive approaches and emphasises the significance of considering parenthood and psychological flexibility in combating stigma toward individuals with SMI in collectivistic religious societies like the Jewish Ultraorthodox community.

Introduction

Serious mental illness (SMI) is defined as a clinically significant behavioural or psychological condition that is accompanied by disability in preforming one or more functional and social roles in the community (Elitzur et al., Citation2010; Kessler et al., Citation2003). It includes disorders such as schizophrenia, major depression, bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Iyer et al., Citation2005).

Public stigma toward individuals with SMI includes such negative stereotypes as being dangerous, unpredictable, incapable of recovering (Read et al., Citation2006), and as responsible for their own illness (Corrigan & Watson, Citation2004). This public stigma has widespread implications in different areas. On a social level, it leads to rejection and discrimination; on a personal level, it leads to impaired quality of life, diminished self-esteem, hopelessness, an increase in depressive symptoms, and frequent hospitalisations (Dewedar et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, this stigma narrows career and education options (Thornicroft et al., Citation2009) and prevents individuals from approaching mental health services (Clement et al., Citation2015; Corrigan et al., Citation2014).

In Jewish Ultraorthodox society, which is characterised as collectivist and religious, stigma toward SMI has been found to be particularly high in comparison to stigmatising attitudes held by general society in this context (Struch et al., Citation2007). Relatively high levels of stigma have also been found in other collectivist and\or religious societies (e.g., Caplan, Citation2019; Gureje et al., Citation2006; Papadopoulos et al., Citation2013). In the current study we examined different possible correlates and moderators associated with stigma toward individuals with SMI in Jewish Ultraorthodox society.

Mental illnesses and stigma in Ultraorthodox society

The Ultraorthodox (Haredi) population is a religious minority in Israeli society and the Jewish world. In Israel, 1,175,088 Jews were officially listed as “Ultraorthodox” in 2020 (Cahaner & Malach, Citation2020, p. 11), i.e., 14% of the Jewish population. The Ultraorthodox community includes a wide range of groups, which are classified into three major streams: Hasidim, Lithuanian, Sephardim (Zalcberg-Block & Zalcberg, Citation2023).

The Ultraorthodox Jewish community is known for its conservative and traditional values, in which religious observance, dedication to studying the holy texts, and family life are given top priority. This community is highly insular and close-knit, with a strong emphasis on social cohesion and unity (Serfaty et al., Citation2020). Members of this community often place a great deal of importance on maintaining the traditions and practices of their ancestors, and they may view a deviation from these norms as a threat to the community’s stability. They also place a strong emphasis on family life and the importance of maintaining strong bonds between family members. In this context, mental illness may be seen as a potential threat to social cohesion and stability, and individuals who have mental health challenges may be viewed as being unable to fully participate in the community (Greenberg & Witztum, Citation2013).

In Ultraorthodox society, the labels associated with SMI may carry religious meaning. The philosopher Rambam believed that the rational part of the human mind is central to our existence, and that a deep connection with God is built through recognition, insight, and knowledge. In his opinion, a person with SMI lacks these attributes, as evidenced by their extreme behaviour. Such individuals’ ability to function rationally may be impaired, resulting in a limited ability to recognise and connect deeply with God (Rambam, Hilchot Deot, chapter 82).

It is important to note that in Hebrew, the word for mental, “nefesh,” holds religious significance, representing a person's Godly essence. For example, in his book sefer gerushim, Rabbi Moses Cordovero (1522–1570) wrote: “the person is the nefesh” (p.12, chapter 17). That is, the body is the vessel and the shell, but the “nefesh” is the essence of man. Therefore, those who struggle with SMI may be viewed as having deficits in their spiritual connection with God, leading to devaluation and stigma within religious society.

Studies conducted in Israel have shown that the level of stigma toward people with SMI is higher in the Ultraorthodox than in the secular community. That is, in the Israeli Ultraorthodox community there is a stronger tendency to perceive people with SMI as violent, leading to their being treated with greater social distance (Rosen et al., Citation2008; Struch et al., Citation2007).

Such higher levels of stigma may be due to a lack of knowledge and exposure to sources of information about SMI in the Ultraorthodox community (Struch et al., Citation2007). Of note, this high level of stigma stands in contrast to one of the salient values of Ultraorthodox society, which is to help and provide support to others (e.g., giving charity) (Gudman, Citation2013).

Due to SMI’s social stigma, Ultraorthodox individuals tend to utilise mental health services only in extreme cases in which they can no longer be taken care of at home (Gudman, Citation2013). These individuals are often reluctant to make use of psychiatric rehabilitation services, for example, due to the social stigma that would affect their social class, their family's reputation, and the Ultraorthodox matchmaking market in particular (Greenberg et al., Citation2012; Gudman, Citation2013). The ultraorthodox marriage matchmaking emphasises emotional, mental and familial stability and health. When weighing the value of a potential marriage candidate, SMI is regarded as a serious deficit (Gudman, Citation2013), Families may conceal any history of mental health challenges or difficulties, fearing that knowledge of such issues would significantly reduce the marriage prospects for their children. This fear that leads to the concealment of SMI, hinders the individual's recovery as proper treatment and support are often avoided or delayed (Greenberg et al., Citation2012).

As previously mentioned, the aim of the current study was to examine several factors as possible correlates of stigma in Jewish Ultraorthodox society. These factors are associated with either the observer (i.e., the study participant) or the characteristics of the target person (i.e., the stigmatised person).

Motherhood of women with SMI as a possible correlate of stigma

Only a few studies have referred to parenting in the context of mental health, compared to the plethora of literature focusing on other social roles in this context, such as housing, occupation, and being part of the community (Nicholson, Citation2007). A few studies have indicated that there is a higher stigma toward mothers with SMI than toward women with SMI who are not mothers. A survey conducted by Dolman and his colleagues (Citation2013) revealed that mothers with SMI felt that the stigma toward them increased when they became mothers. Another study showed that the level of stigma toward women with physical disabilities did not change, regardless of whether they were presented as mothers or not, whereas the stigma toward women with SMI increased when they were presented as mothers (Hasson-Ohayon et al., Citation2018).

In Ultraorthodox communities, marriage and parenting are considered to be supremely important social and religious values, and much effort is invested in finding a match for all single individuals, including those with SMI (Bart & Ben Ari, Citation2014; Gershuni & Ziv, Citation2018). Birth rates in Ultraorthodox society are notably high (between 6 to7), driven by the cultural and religious significance attached to fertility and reproduction (Raucher, Citation2021; Stone, Citation2023). Rooted in religious commandments, particularly the biblical directive to “be fruitful and multiply” (Genesis, 1:28), having large families is considered a sacred duty (Raucher, Citation2021). This demographic characteristic serves to preserve the unique religious and cultural identity of Ultraorthodox communities and ensure the transmission of traditions through generations (Korb, Citation2011; Okun, Citation2017). The woman's role is central in fulfilling this cultural imperative, as the expectation for large families places a substantial emphasis on her role as a mother and caregiver (Korb, Citation2011).

It is possible that, given that motherhood in this population implies success in fulfilling an important social and religious role, being a mother may reduce stigma toward women with SMI, as it may compensate for the negative stereotypes that abound. Specifically, being a mother may be perceived as the woman’s functioning and succeeding in fulfilling an important role and, accordingly, may make up for the stereotypes of non-productivity that are associated with SMI.

Observers’ parenthood and psychological flexibility as possible correlates of stigma

As mentioned above, parenting in Ultraorthodox society is seen as having supreme religious and social value and as being a primary purpose of life (Siebzehner & Lehmann, Citation2014). Parents have the responsibility to pass on the Ultraorthodox tradition to the next generation, and to do so requires much investment in their kids (Bart & Ben Ari, Citation2014). Parents also have a great deal of authority and involvement in the lives of their adult children and in their fateful decisions such as choosing a spouse for marriage, a place of study, and employment (Feldman, Citation2015; Gilboa, Citation2015). Due to the centrality of the parenting role in this society, it is possible that Ultraorthodox parents would be more judgmental toward mothers with SMI than they would be toward nonparents with SMI. Given how familiar they are with parenting’s many responsibilities, they may perceive mothers with SMI as less able to fulfil their parental role.

Although observers’ own parenthood might increase stigma toward mothers with SMI, their psychological flexibility may decrease it. According to Hayes et al. (Citation2006), psychological flexibility is “the ability to contact the present moment fully as a conscious human being, and to change or persist in behaviour when doing so serves valued ends” (p. 7). A recent meta-analysis revealed a high positive association between psychological inflexibility and stigma across 16 studies in different contexts (Krafft et al., Citation2018). Specifically, in the area of mental health, studies showed that psychological flexibility was associated with lower levels of stigma toward patients with SMI (Masuda et al., Citation2009). In addition, studies showed that psychological flexibility was negatively associated with ideological commitment to conservatism and frequency of religious practice (Buechner et al., Citation2021; Van Hiel et al., Citation2016; Zmigrod et al., Citation2019). Ultraorthodox Jewish society is a religious conservative society and therefore may show a tendency toward psychological inflexibility. In this study we examined, in addition to the expected main effect of psychological flexibility on stigma, a possible moderating role of flexibility in the effect of the interaction between target person’s motherhood and target person’s SMI on stigma. It could be that the expected effects of the target being presented as having SMI and as being a mother would be stronger among observers with low psychological flexibility.

Based on the above reviewed literature, in the current study we assessed the associations of the target person’s motherhood, and both the observer’s parenthood and psychological flexibility, with stigma toward women with SMI among people from the Jewish Ultraorthodox community. Different types of psychiatric illness elicit different levels of stigma and negative attitudes, schizophrenia often receives the highest level of stigma (Setti et al., Citation2019). In our study we referred to a general psychiatric illness and not a specific diagnosis. Our hypotheses were: 1) Participants would show more negative attitudes toward women with SMI than toward women without SMI; 2) Participants would show more negative attitudes toward women who were not mothers than toward women who were mothers; 3) An interaction effect on stigma would be found between the target person having (or not having) SMI and being (or not being) a mother. Namely, the expected negative attitudes toward women with SMI (vs women without SMI) would be less for those presented as mothers vs those presented as non-mothers; 4) Participant’s parenthood would be related to high levels of stigma toward women with SMI, and this effect would be stronger when the target person was presented as a mother. Namely, an interaction effect between target person’s motherhood and observer’s parenthood was expected; 5) Participants with higher psychological flexibility, compared to those with lower psychological flexibility, would show lower levels of stigma toward women with SMI; 6) Psychological flexibility would moderate the expected interaction between the target person being presented as a mother and as having SMI (Hypothesis 3). Namely, the interaction would be stronger among participants with low psychological flexibility than among those with high psychological flexibility.

Method

Participants

The original sample included 163 adult men and women aged 18 and above who defined themselves as Ultraorthodox Jews. Inclusion criteria were being affiliated with the Ultraorthodox community (based on self-report), being 18 years old or above, having the ability to read and write in Hebrew, and not having a psychiatric diagnosis. Of the potential participants, 13 were excluded: Three did not complete the questionnaires, and 10 answered that they had a psychiatric diagnosis. The final sample included 150 participants, 66 men and 84 women.

Materials

Sociodemographic questionnaire: This measure included several questions regarding participants’ age, gender, education, parenthood (yes\no), and acquaintance with individuals with SMI, as well as their religious affiliation.

Vignettes: The vignettes were taken from a study by Hasson-Ohayon et al. (Citation2018), which assessed attitudes toward motherhood of women with different types of disability: physical and psychiatric. In the present study, we used four of these vignettes, describing brief scenarios of meeting with a woman who was presented as: 1. A mother with SMI; 2. A mother without SMI; 3. A woman who is not a mother but has SMI; and, 4. A woman who is both not a mother and does not have SMI. SMI was defined in the vignette as a “psychiatric illness”, the diagnosis was vague without a specific label. Each participant received one version out of these four, randomly. The vignettes were in Hebrew language.

Social Distance Scale (SDS): This is a self-report questionnaire consisting of seven items that assess the desire for different social connections (e.g., renting a home, working together). In the current study, participants completed the questionnaire with reference to the person described in the vignette they randomly received. This questionnaire was developed in English by Link et al. (Citation1987), based on the Bogardus Questionnaire (Bogardus, Citation1925) and is extensively used in its Hebrew version (e.g., Hasson-Ohayon et al., Citation2018). Participants rated each of the statements on a four-level scale (1 = disagree, 4 = strongly agree) whereby the score is constructed from the average of the seven items. A low average indicates a greater desire for social distance. We modified the original wording of the questionnaire, and for each section added the word “psychiatric” before the word “disability.” For example: “How would you feel about renting a room in your home to a person with a psychiatric disability?” Item 5 (“How would you feel about introducing this woman to your friends?”) was removed from the questionnaire due to concerns that it did not align with relevant social norms in Ultraorthodox society. Cronbach's alpha reliability in a previous study was .9 (Angermeyer et al., Citation2004). In the current study it was found to be .85.

Multidimensional Attitudes Scale (MAS): Attitudes toward people with disabilities was measured by the Multidimensional Attitudes Scale Toward Persons with Disabilities (MAS; Findler et al., Citation2007), which was developed in both English and Hebrew. Participants were asked to react after they read one of our four vignettes. The scale reflects the degree of likelihood that the participant would feel, think, or behave in a certain way. Responses are marked on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). According to Findler et al. (Citation2007), four factors can be computed from the questionnaire: (I) negative emotions, (II) distancing behaviours, (III) calmness, and (IV) positive cognitions. Higher scores indicate more negative emotions, more distancing behaviours, less calmness, and fewer positive cognitions. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for MAS factors ranges from .68 to .90 (Vilchinsky et al., Citation2010). In the current study Cronbach's alpha reliability of the total score was found to be .79 to .91.

Psychological flexibility: Level of psychological flexibility was assessed via the Hebrew version (Ben-Yaacov, Citation2014) of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II), developed by Bond et al. (Citation2011). The scale consists of seven items, and participants rate each statement on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true). This scale reflects the single domain of psychological inflexibility, with higher scores indicating greater psychological inflexibility, or experiential avoidance. In their study, Bond et al. (Citation2011) found a .84 mean α coefficient across six samples (ranging between .78 and .88). In this study, Cronbach's alpha reliability was .9.

Procedure

Following ethical approval, participants were recruited in accordance with the snowball method at centres of Ultraorthodox life, such as yeshivas, seminary and academic centres (i.e., places where Ultraorthodox men and woman study), in different cities in Israel. After participants confirmed their agreement to participate in the study, they were asked to answer the sociodemographic questionnaire and the psychological flexibility questionnaire. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of four groups according to the vignette conditions (i.e., with\without SMI, and being a mother\non-mother), followed by the stigma questionnaires (MAS and SDS). Scales and exposure to vignette were all done via Qualtrics platform online by a link sent to the participants, or through paper copies given by hand in their institution by a research assistant, without any need for more interaction with the researchers.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21.0 for Windows (SPSS-21). Chi-square tests of independence were performed to examine the association between the different background characteristics and the four test conditions. In addition, zero-order correlations were conducted to examine the associations between sample characteristics and the SDS and MAS scores.

In order to assess the association between the independent variables of SMI (with\without) and motherhood (yes\no) with stigma scales (SDS and MAS), a two-way (2X2) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted in accordance with the study's conditions. Finally, two-way and three-way interactions with the hypothesised moderators were entered into the model and their effect were examined: Target person’s SMI and motherhood, and observer’s psychological flexibility (high\low) and parenthood (yes\no).

Results

Socio-demographic variables are presented in . Chi-square tests of independence presented in indicated no significant associations between participants’ characteristics (gender, marital status, community affiliation, parenthood, academic education, and contact with person with SMI) and the different experiment conditions. When assessing possible correlations between socio variables and stigma scores, two correlations were uncovered: observer’s parenthood and contact with person with SMI were shown to be associated with stigma variables (r = .18, p < .028; r = .17, p < .03 respectively), and therefore they were entered into the model as covariates. Of note, when examining the effect of observer’s parenthood, it was considered to be an independent variable and not a covariate.

Table 1. Demographic data of the participants (n = 150).

Table 2. Participants’ attitudes (means, SDs) towards women (mothers and non-mothers) with SMI\without SMI according to the Multidimensional Attitudes Scale (MAS) and Social Distance Scale (SDS) factors.

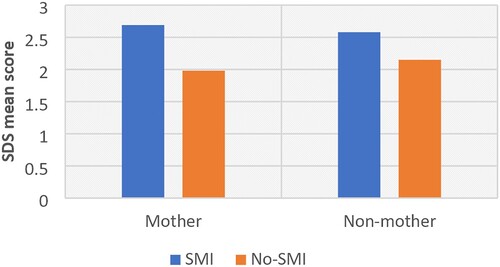

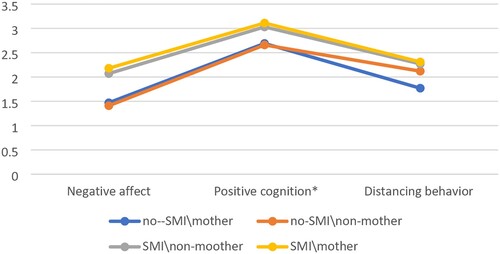

Assessing main effects of target’s SMI and motherhood and the effect of their possible interaction on stigma

MANOVA analysis showed a main effect of presenting the target person with or without SMI, Wilks’ lambda = .5, F(6,139) = 10.80, p < .0001, over all outcome variables (domains of attitudes scale and social distance scale), after controlling for previous contact with a person with SMI and observer’s parenthood. Univariate statistics indicated that this main effect was significant for SDS, F(1,144) = 31.94 p < .0001: The level of participant's tendency toward keeping social distance from the women described in the vignette was higher toward those with SMI vs. without SMI (M = 2.64, 2.06, respectively,) as can be seen in . This main effect was also found in relation to several factors of the MAS scale: negative affect, F(1,144) = 40.98 p < .0001; positive cognition, F(1,144) = 9.90 p < .002; and distancing behaviour, F(1,144) = 6.42, p < .012. Participants showed higher levels of negative affect and distancing behaviour toward women with SMI than toward women without SMI, as well as lower levels of positive cognition toward women with SMI vs. women without SMI, as can be seen in . No main effect of target person’s motherhood was observed; that is, participants showed no difference in level of negative attitude or desire for social distance regardless of whether the target person was presented as a mother or not. The expected effect of the interaction between SMI and motherhood on stigma was not found to be significant either.

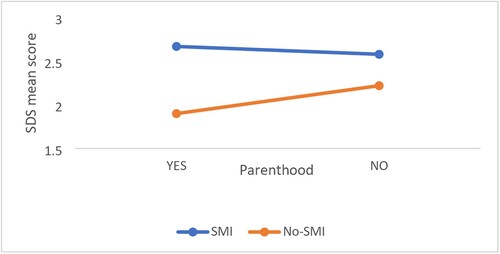

Assessing the moderating effects of observer’s parenthood and psychological flexibility

Two-way interactions and three-way interactions were found. First, a two-way interaction effect between the target person being presented as having or not having SMI and observer’s parenthood (i.e., participants either being or not being parents) was found to be significant beyond all outcome variables, Wilks’ lambda = .9, F(6,138) = 2.45, p < .028. Univariate analysis revealed that this effect was found significant only for the SDS, F(1,143) = 4.46, p < .036, as can be seen in . The tendency toward keeping social distance from the women described in the vignette was higher toward women presented with SMI vs. without SMI, and this effect was significantly stronger among participants who were parents than those who were not parents.

Figure 3. An interaction effect between SMI of the target person and parenthood of the observer of SDS.

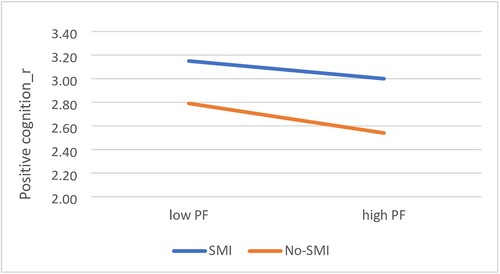

Second, a two-way interaction between level of observer’s psychological flexibility and target person’s being presented as having or not having SMI was found to be significant beyond all variables, Wilks’ lambda = .894, F(6,148) = 2.93, p < .010. This effect was found to be specifically significant for the positive cognition dimension of MAS, F(1,153) = 4.79, p < .011. A lower level of positive cognition toward the women described in the vignette was found toward women presented with SMI vs. without SMI, and this effect was significantly stronger among participants who had low vs. high psychological flexibility, as can be seen in .

Figure 4. An interaction effect between of SMI and psychological flexibility (PF) on positive cognition. Note: Positive cognition-high scores mean lower level of positive cognition and vice versa.

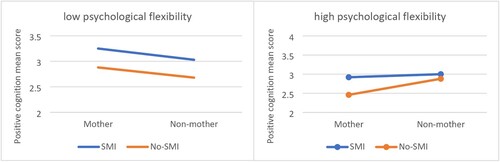

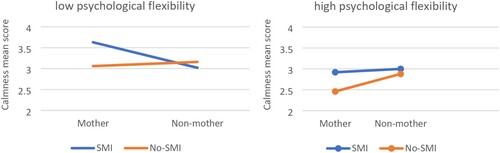

In addition, although there was no significant two-way interaction effect between the target person’s being presented as having or not having SMI and as being or not being a mother, a three-way interaction between the target person’s being presented as having/not having SMI and as being/not being a mother, and level of observer’s psychological flexibility (high\low), was found to be significant beyond all outcome variables, Roy's Largest Root = F(6,138) = 3.17, p < .006. A between-subjects test revealed that psychological flexibility moderated the effect of the interaction between SMI and motherhood on the calmness (i.e., the level of calmness in response to a person with SMI), F(4,140) = 2.57, p < .04, and positive cognition, F(4,140) = 2.63, p < .036, dimensions of the MAS.

shows that among participants with low psychological flexibility, there were fewer calmness responses when a woman with SMI was presented as a mother than when she was presented as a non-mother. In contrast, among participants with high psychological flexibility, the number of calmness responses did not change whether the woman with SMI was presented as a mother or not.

Figure 5. Psychological flexibility moderates the interaction between SMI and motherhood, on the hand, with calmness, on the other. Note: Calmness-high scores mean lower levels of calmness and vice versa.

Similarly, shows that among participants with low psychological flexibility, there were fewer positive cognitions when a woman with SMI was presented as a mother than when she was presented as a non-mother. In contrast, among participants with high psychological flexibility, the level of positive cognition did not change toward the woman with SMI, whether she was presented as a mother or not.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine the correlates of stigma toward women with SMI in Ultraorthodox Jewish society. The factors that were examined were motherhood of the target woman with SMI, parenthood of the observer, and psychological flexibility of the observer. Findings indicated high levels of stigma toward women with SMI, regardless of whether they were presented as mothers or not. Observer’s parenthood was found to have an adverse effect on stigma; that is, parents had a greater desire for social distance from women with SMI than did participants who were not parents. In addition, we found that psychological flexibility was negatively associated with level of stigma and moderated the interaction between target person’s motherhood and SMI. Specifically, among participants with high psychological flexibility, the level of stigma did not change regardless of whether the woman with SMI was presented as a mother or not. Among participants with low psychological flexibility, however, higher levels of stigma were shown toward women with SMI who were presented as mothers compared to women with SMI who were presented as non-mothers.

The main effect of SMI on level of stigma in the Ultraorthodox community found in this study is consistent with findings from studies that were previously conducted in the general population (e.g., Gaebel et al., Citation2002; Read et al., Citation2006) as well as in Ultraorthodox society (Rosen et al., Citation2008; Struch et al., Citation2007). That said, whereas the focus of previous studies conducted in this community was on the desire for social distance and discrimination (e.g., Struch et al., Citation2007), the current study highlights specific dimensions of feelings, thoughts, and behaviours that are associated with stigma toward SMI – that is, distancing behaviours, negative affect, and fewer positive cognitions toward women with SMI.

Although no positive effect of target person’s motherhood was found on level of stigma, observer’s parenthood showed a negative effect, as expected. Participants who were parents expressed a tendency for more distance from a woman with SMI, compared to non-parents. That said, this finding was revealed regardless of the target person’s being a mother or not. The higher stigma that was found among Ultraorthodox individuals who were parents could be related to the culturally-sanctioned involvement of parents in their children’s lives in this community, including concerns regarding their children’s marriage options. It could be that the significant implications of having SMI, or even of being in touch with a person with SMI, for arranged matches (Greenberg et al., Citation2012) is related to the greater desire for social distance that was found among these parents. To the best of our knowledge, the effect of the parenting variable (i.e., of the observer) on stigma has not been examined in previous studies. This finding may have important implications for the design of stigma reduction strategies tailored for parents. As this finding is preliminary, further in-depth studies with other populations are needed to explore possible reasons why parents tend to severely judge those who have SMI.

Consistent with previous studies on psychological flexibility and stigma in different contexts (e.g., Levin et al., Citation2014; Masuda et al., Citation2009), the current study showed that high psychological flexibility was related to lower levels of stigma. Interestingly, high psychological flexibility seemed to buffer against the negative effect of motherhood of women with SMI, as only among participants with low psychological flexibility did the presentation of a woman with SMI as a mother increase stigma. Thus, the motherhood of women with SMI seems to create a more judgmental attitude, but only on the part of people with low psychological flexibility. A possible explanation for this finding is that people with low psychological flexibility also tend to have rigid perceptions of traditional gender roles (McGlenn, Citation2020; Mendoza et al., Citation2018) and therefore may have a more stigmatising attitude toward a mother with SMI (i.e., whose ability to fulfil her traditional role is sometimes in question).

Limitations

The current study had a few limitations. First, Ultraorthodox society is diverse and is made up of various groups. Some are open to different levels of connectedness with secular society, and have more access to internet and the media, and some are relatively closed and isolated. In this study we tried as much as possible to obtain a representative sample, but it may be that the somewhat heterogeneous sample still does not represent all Ultraorthodox individuals. Second, the vignettes depict women coping with SMI, even though many of the study’s participants were men. It is possible that if a male figure had been depicted in the vignettes, the findings would have been different, due to identification with a male or female figure. Third, in the present study there was no comparison group of participants from the general public, as there was in a previous comprehensive study conducted by Struch et al. (Citation2007). Fourth, a large percentage of participants stated that they had previous contact with a person with SMI. Although the previous contact includes a wide range of possible closeness (e.g., family contact, coincidental contact), this may indicate a possible bias in the current sample. Last, in this study we did not take into account differences in stigma toward the target people on the basis of the kind of SMI they had, for example, depression versus schizophrenia.

Conclusions and implications of the study

In light of the current study’s findings, we would recommend developing culturally sensitive interventions to reduce social stigma toward those with SMI in Ultraorthodox society. We would also recommend integrating into existing interventions (e.g., campaigns and education) elements that focus on increasing psychological flexibility. One option for strengthening psychological flexibility is via interventions that promote non-judgmental acceptance (such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and mindfulness: Hayes et al., Citation2006; Marais et al., Citation2020), which are compatible with Judaism’s mindset and values. Possible adjustments may include cultural elements such as addressing religious beliefs and values, the importance of the family, and community resources. Also, it will be important to use language that is familiar and understandable to the community. In addition, we would recommend providing targeted psychoeducation to reduce stigma among parents. To this end, professionals must act through accepted channels in Ultraorthodox society such as rabbis, sectoral journals aimed at parents, sectoral radio, and educational institutions. It is crucial to work closely with community leaders and organisations to ensure that interventions are culturally and socially appropriate and meet the needs of the Ultraorthodox Jewish community.

From a research point of view, it is recommended to continue mapping the complex and unique causes of stigma toward people with SMI in Ultraorthodox Jewish society. In addition, the effectiveness of interventions to reduce stigma among the Ultraorthodox population should be evaluated, as there may be valuable implications for other collectivist religious societies as well.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statements

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- Angermeyer, M. C., Matschinger, H., & Corrigan, P. W. (2004). Familiarity with mental illness and social distance from people with schizophrenia and major depression: Testing a model using data from a representative population survey. Schizophrenia Research, 69(2-3), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00186-5

- Bart, A., & Ben Ari, A. (2014). After the altar tears down: Personal and social dealing with divorce in Ultra-Orthodox society. Journal of Haredi Society Research, 1, 100–126. Hebrew.

- Ben-Yaacov, D. (2014). Hebrew version of the AAQ-II. https://contextualscience.org/AAQ_Hebrew

- Bogardus, E. S. (1925). Measuring social distance. Journal of Applied Sociology, 9, 299–308. https://brocku.ca/MeadProject/Bogardus/Bogardus_1925c.html

- Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. C., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., Waltz, T., & Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

- Buechner, B. M., Clarkson, J. J., Otto, A. S., Hirt, E. R., & Ho, M. C. (2021). Political ideology and executive functioning: The effect of conservatism and liberalism on cognitive flexibility and working memory performance. Social Psychological and Personality Science 12(2), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620913187

- Cahaner, L., & Malach, G. (2020). The yearbook of the Haredi society in Israel: 2020. Israel Democracy Institute.

- Caplan, S. (2019). Intersection of cultural and religious beliefs about mental health: Latinos in the faith-based setting. Hispanic Health Care International, 17(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540415319828265

- Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., Maggioni, F., Evans-Lacko, S., Bezborodovs, N., Morgan C., Rüsch N., Brown J. S. L., & Thornicroft, G. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000129

- Corrigan, P. W., Druss, B. G., & Perlick, D. A. (2014). The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15(2), 37–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614531398

- Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2004). At issue: Stop the stigma: Call mental illness a brain disease. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 30(3), 477. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007095

- Dewedar, A. S., Harfush, S. A., & Gemeay, E. M. (2018). Relationship between insight, self-stigma and level of hope among patients with schizophrenia. IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science, 7, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.9790/1959-0705031524

- Dolman, C., Jones, I., & Howard, L. M. (2013). Pre-conception to parenting: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature on motherhood for women with severe mental illness. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 16(3), 173–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0336-0

- Elitzur, A., Tiano, S., Munitz, H., & Neumann, M. (2010). Select chapters in psychiatry. Papyrus Publishing, Tel Aviv University.

- Feldman, N. (2015). Health capital and manipulativeization in the Ultraorthodox ‘society of matchmakers’ [Master's thesis]. Tel Aviv University. https://primage.tau.ac.il/libraries/theses/humart/free/002533814.pdf

- Findler, L., Vilchinsky, N., & Werner, S. (2007). The Multidimensional Attitudes Scale Toward Persons with Disabilities (mas): Construction and validation. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 50(3), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/00343552070500030401

- Gaebel, W., Baumann, A., Witte, A. M., Zaeske H. (2002). Public attitudes towards people with mental illness in six German cities. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 252(6), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-002-0393-2

- Gershuni, H., & Ziv, N. (2018). The right to marry women with disabilities in the Ultraorthodox sector-critical aspects [Master's thesis]. Tel Aviv University. https://www.kshalem.org.il/uploads/pdf/article_4356_1548690075.pdf

- Gilboa, H. (2015). “She bringeth her food from afar”; Haredi women working in Israel's high-tech market. The Study of Haredi Society, 2, 193–220. Hebrew. https://jerusaleminstitute.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/05

- Greenberg, D., Buchbinder, J. T., & Witztum, E. (2012). Arranged matches and mental illness: Therapists’ dilemmas. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 75(4), 342–354. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2012.75.4.342

- Greenberg, D., & Witztum, E. (2013). Challenges and conflicts in the delivery of mental health services to Ultra-orthodox Jews. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 6(1), 71–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2012.10.008

- Gudman, J. (2013). The exile of broken tools: Anxious in the shadow of madness. University of Haifa, Hamed Press.

- Gureje, O., Olley, B. O., Olusola, E. O., & Kola, L. (2006). Do beliefs about causation influence attitudes to mental illness? World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 5(2), 104–107. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.5.436

- Hasson-Ohayon, I., Hason-Shaked, M., Silberg, T., Shpigelman, C. N., & Roe, D. (2018). Attitudes towards motherhood of women with physical versus psychiatric disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 11(4), 612–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.05.002

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J., Bond, F., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

- Iyer, S. N., Rothmann, T. L., Vogler, J. E., & Spaulding, W. D. (2005). Evaluating outcomes of rehabilitation for severe mental illness. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.50.1.43

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Koretz, D., Merikangas, K. R., Rush, A. J., Walters, E. E., & Wang, P. S. (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(23), 3095–3105. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.23.3095

- Korb, S. (2011). Mothering fundamentalism: The transformation of modern women into fundamentalist mothers. Institute of Transpersonal Psychology.

- Krafft, J., Ferrell, J., Levin, M. E., & Twohig, M. P. (2018). Psychological inflexibility and stigma: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 7, 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.11.002

- Levin, M. E., Luoma, J. B., Lillis, J., Hayes, S. C., & Vilardaga, R. (2014). The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–Stigma (AAQ-S): Developing a measure of psychological flexibility with stigmatizing thoughts. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 3(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2013.11.003

- Link, B. G., Cullen, F. T., Frank, J., & Wozniak, J. F. (1987). The social rejection of former mental patients: Understanding why labels matter. American Journal of Sociology, 92(6), 1461–1500. https://doi.org/10.1086/228672

- Marais, G. A., Lantheaume, S., Fiault, R., & Shankland, R. (2020). Mindfulness-based programs improve psychological flexibility, mental health, well-being, and time management in academics. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(4), 1035–1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10040073

- Masuda, A., Hayes, S. C., Lillis, J., Bunting, K., Herbst, S. A., & Fletcher, L. B. (2009). The relation between psychological flexibility and mental health stigma in acceptance and commitment therapy: A preliminary process investigation. Behavior and Social Issues, 18(1), 25–40.

- McGlenn, M. P. (2020). The relationship between psychological inflexibility, cognitive fusion, gender role conflict, and normative male alexithymia in a sample of cisgender males (Order No. 13425254) [ProQuest dissertations and theses, 110]. Alliant International University. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/relationship-between-psychological-inflexibility/docview/2166838153/se-2

- Mendoza, H., Goodnight, B. L., Caporino, N. E., & Masuda, A. (2018). Psychological distress among Latina/o college students: The roles of self-concealment and psychological inflexibility. Current Psychology, 37(1), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9500-9

- Nicholson, J. (2007). Helping parents with mental illness: Providers often do not take into account adult consumers' family roles. Behavioral Healthcare, 27(5), 32–33. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A164807477/AONE?u=anon∼e01577c0&sid=googleScholar&xid=15782008

- Okun, B. S. (2017). Religiosity and fertility: Jews in Israel. European Journal of Population, 33(4), 475–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9409-x

- Papadopoulos, C., Foster, J., & Caldwell, K. (2013). ‘Individualism-collectivism’ as an explanatory device for mental illness stigma. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(3), 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-012-9534-x

- Raucher, M. (2021). Jewish pronatalism: Policy and praxis. Religion Compass, 15(7), e12398. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec3.12398

- Read, J., Haslam, N., Sayce, L., & Davies, E. (2006). Prejudice and schizophrenia: A review of the ‘mental illness is an illness like any other’ approach. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114(5), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00824.x

- Rosen, D., Greenberg, D., Schmeidler, J., & Shefler, G. (2008). Stigma of mental illness, religious change, and explanatory models of mental illness among Jewish patients at a mental-health clinic in North Jerusalem. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 11(2), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670701202945

- Serfaty, D. R., Cherniak, A. D., & Strous, R. D. (2020). How are psychotic symptoms and treatment factors affected by religion? A cross-sectional study about religious coping among Ultraorthodox Jews. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113349

- Setti, V. P. C., Loch, A. A., Modelli, A., de Almeida Rocca, C. C., Hungerbuehler, I., van de Bilt, M. T., Gattaz Wagner Farid, & Rössler, W. (2019). Disclosing the diagnosis of schizophrenia: A pilot study of the ‘Coming Out Proud’ intervention. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 65(3), 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019840057

- Siebzehner, B., & Lehmann, D. (2014). Arranged marriage in the Haredi world: Authority, boundaries, and institutions. Megamot, 49, 641–668. Hebrew.

- Stone, L. (2023). Ultra-Orthodox fertility and marriage in the United States: Evidence from the American community survey. Demographic Research, 49, 769–782. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2023.49.29

- Struch, N., Shereshevsky, Y., Baidani, A., Lachman, M., Zehavi, T., & Sagiv, N. (2007). Stigma, discrimination and mental health in Israel: Stigma against people with psychiatric illnesses and against mental health care. Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute and Mental Health Services of the Israel Ministry of Health.

- Thornicroft, G., Brohan, E., Rose, D., Sartorius, N., & Leese, M. (2009). Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional survey. The Lancet, 373(9661), 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61817-6

- Van Hiel, A., Onraet, E., Crowson, H. M., & Roets, A. (2016). The relationship between right-wing attitudes and cognitive style: A comparison of self-report and behavioral measures of rigidity and intolerance of ambiguity. European Journal of Personality, 30(6), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2082

- Vilchinsky, N., Werner, S., & Findler, L. (2010). Gender and attitudes toward people using wheelchairs: A multidimensional perspective. Re-habilitation Counseling Bulletin, 53(3), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355209361207

- Zalcberg-Block, S., & Zalcberg, S. (2023). Experiences, Perceptions, and Meanings of the Ultra-Orthodox in Israel Regarding Premarital Genetic Testing. Journal of Religion and Health, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-023-01833-4

- Zmigrod, L., Rentfrow, P. J., Zmigrod, S., & Robbins, T. W. (2019). Cognitive flexibility and religious disbelief. Psychological Research, 83(8), 1749–1759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-018-1034-3