ABSTRACT

This paper applies institutional theory to analyse the institutional pressures (regulatory, market, competitive) experienced by two actors within supply chains: shippers (i.e. logistics buyers) and logistics service providers (LSPs). Both actors are subject to institutional pressures to adopt green supply chain management practices, which could drive shippers to purchase green logistics services from LSPs, and LSPs to provide them. Also, the two actors are influenced by various factors that moderate the level of pressures on them and the responses they undertake. This study examines these pressures and moderators in detail to analyse how they influence green logistics purchasing/providing decisions. Empirical data were obtained from eight individual cases of three shippers and five LSPs. Accordingly, we compare these pressures and moderators based on the actors’ different roles in the supply chain. The findings aim to contribute to advancing the theory through (i) incorporating the roles of the moderating factors and (ii) providing further applications within specific shipper-LSP contexts. Further, this paper aims to assist managers within shipper and LSP organisations by demonstrating how their firm and market characteristics moderate the pressures exerted on them to buy or provide green logistics services, while providing insights on issues influencing their responsiveness.

1. Introduction

A growing trend of incorporating green measures into supply chains is observed today in response to the rising global pressures to preserve the planet. Among different supply chain sectors, the logistics and transport sector is considered one of the main contributors to various environmental threats such as air pollution, global warming and resource depletion (McKinnon et al. Citation2015). Almost 20% of global energy consumption is associated with transportation (IEA Citation2015). Even worse, the total tonne-kilometres travelled by road freight is expected to triple between 2015 and 2050 due to the latest developments of the world economy and increasing global demands (ITF Citation2017), leading to further emissions and environmental harm (Grant, Trautrims, and Wong Citation2015). Such figures expand the burden on logistics services providers (LSPs) to expedite the ‘greening’ process of their logistics functions, given their central position among supply chains and the dependability of other actors on them in carrying out their logistics functions (Colicchia et al. Citation2013; Rossi et al. Citation2013). However, LSPs are not the only actors responsible for facilitating green logistics practices; scholars started realising that shippers (i.e. logistics buyers) play an important role as well (see Rogerson Citation2017; Sallnäs Citation2016; Wolf and Seuring Citation2010), as it is shippers who select LSPs and make the choices on where and how locations are set up (Wolf and Seuring Citation2010).

Due to the significance of shippers’ and LSPs’ roles amid supply chains, investigating what drives their engagement (to either buy or provide green logistics) is garnering increased academic attention. In general, a number of studies focus on what drives supply chain actors to engage in green supply chain management (GSCM) practices (e.g. Walker, Di Sisto, and McBain Citation2008; Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2007), but without providing clear linkages to logistics purchasing/providing decisions. Others, while focusing on logistics, capture what drives shippers to purchase green logistics services (e.g. Björklund Citation2011) or LSPs to provide them (e.g. Evangelista Citation2014; Lieb and Lieb Citation2010; Perotti, Micheli, and Cagno Citation2015). However, few studies seem to incorporate both actors’ viewpoints concurrently to grasp what the main drivers for facilitating green logistics are. In an effort to investigate what drives LSPs in particular, Kudla and Klaas-Wissing (Citation2012) studied how shippers stimulate LSPs to act sustainably, and how LSPs respond. Although the authors focused on shipper-LSP dyads, empirical data were based only on LSPs’ information. The authors later remarked on instances where even sustainability-proactive shippers have barely integrated logistics purchasing in their sustainability management, stressing the demand for further research to include the shippers’ standpoint. Large, Kramer, and Hartmann’s (Citation2013) survey of shippers similarly found that placing high importance on sustainability measures by shippers does not occur to the same degree when they engage with LSPs.

Other studies that did involve both perspectives (e.g. Björklund and Forslund Citation2013; Sallnäs Citation2016; Wolf and Seuring Citation2010) seem to mainly focus on how environmental practices are coordinated in shipper-LSP relationships, neglecting to take a step backward to outline what motivates the actors’ green engagement. Moreover, when studies focus on shipper-LSP dyads, the role of other stakeholders beyond the buyer and seller (e.g. regulators and competitors) tends to be overlooked, resulting in a somewhat oversimplified analysis.

Based on the reasoning above, the purpose of this paper is threefold: (i) to investigate how the drivers for shippers to engage in GSCM practices are related to demanding green logistics practices from LSPs, (ii) to analyse the importance of shippers’ demands in driving LSPs to implement green logistics practices compared with other influencers such as regulators and competitors, and (iii) to compare what drives shippers and LSPs to engage in green logistics practices (through buying/offering them), given their vital roles in facilitating these practices.

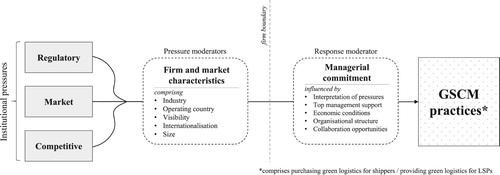

To fulfil the purpose, we will utilise institutional theory to analyse the institutional pressures (i.e. external drivers) on firms to engage in environmental actions. These pressures, within a GSCM context, alternate between regulatory, market and competitive pressures (Zhu and Sarkis Citation2007). Institutional theorists stress that firm and market characteristics moderate the level of pressure experienced by a firm via either magnifying or diminishing it (see Delmas and Toffel Citation2008; Gardberg and Fombrun Citation2006; Levy and Rothenberg Citation2002). Five of these ‘pressure moderators’ are focused upon in this paper: industry, operating country, visibility, internationalisation and size. One of the major limitations of the theory is that it ignores the role of top management in influencing the environmental responsiveness of a firm (Colwell and Joshi Citation2013; Dacin, Goodstein, and Scott Citation2002; Kostova and Roth Citation2002), thus failing to explain why firms under similar institutional contexts might respond differently. Resolving this is suggested by incorporating the role of managerial commitment in moderating the environmental responsiveness of a firm (Colwell and Joshi Citation2013; Sharma Citation2000). We shed light upon such role in this paper through the connotation ‘response moderator’.

This study contributes in advancing the theory through (i) incorporating the influence of pressure/response moderators to engage in GSCM practices, and (ii) providing further applications in specific shipper-LSP contexts. Further, by comparing buyer and seller views on environmental sustainability pressures and moderators, contrasting patterns will emerge based on the actors’ different, and significant, roles in the supply chain, providing further depth through conceptualising how their different institutionalised conditions influence green logistics practices. For the empirical part of this paper, data were collected from a multiple-case study of eight distinct cases, three shippers and five LSPs. The paper aims to assist managers within shipper and LSP organisations by demonstrating how their firm and market characteristics moderate the pressures exerted on them to buy or provide green logistics services, while providing insights on issues influencing their responsiveness.

Section 2 of this paper creates a theoretical framework encompassing the institutional pressures to implement GSCM practices and clarifying the pressure and response moderators. This is followed by constructing the main framework of the study. After section 3 on methods and section 4 on findings, section 5 discusses the findings while cross-matching them with the theory. Lastly, section 6 draws the main conclusions together with discussing the limitations and avenues for further research.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Institutional pressures to implement GSCM practices

Institutional theory highlights the role of social and cultural pressures that affect organisations’ practices and structures in order to gain legitimacy or acceptance within the society (Scott Citation1987). DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) stress that managerial decisions within organisations are primarily influenced by three institutional forces: coercive, normative and mimetic. The application of the theory is encouraged in operations management research (Ketokivi and Schroeder Citation2004), as well as environmental management studies (Delmas and Toffel Citation2004; Hoffman Citation2001), which has inspired others to utilise the theory in the GSCM context to explain why firms in a supply chain adopt environmental practices (see Wu, Ding, and Chen Citation2012; Zhu and Sarkis Citation2007; Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2013). According to Zhu and Sarkis (Citation2007), institutional forces within GSCM are projected by regulatory (coercive), market (normative) and competitive (mimetic) pressures. Colicchia et al. (Citation2013, 198) define institutional drivers within GSCM as ‘external forces that motivate companies to adopt environmental initiatives coming from regulators, the market and competitors coherently with the institutional theory’.

Regulatory pressure can be defined as ‘the coercive pressures driving the implementation of GSCM by (…) managers in hopes of improving their performance’ (Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2013, 107). An example of this type of pressure is when governmental agencies enforce certain policies or taxation on firms to limit the environmental impact associated with their business (Seuring and Müller Citation2008; Walker, Di Sisto, and McBain Citation2008). Market pressure, in turn, is defined by Zhu and Sarkis (Citation2007) as the pressure from customers on suppliers to act sustainably, in which firms demand that their suppliers comply with environmental and social norms (Seuring and Müller Citation2008), such as acquiring environmental management system certifications like the ISO 14001. Last, competitive pressure is emphasised when firms mimic green strategies adopted by successful firms in their field in an attempt to increase their legitimacy, enhance their performance, and gain competitive advantages (Colicchia et al. Citation2013; Markley and Davis Citation2007).

2.2. Firm and market characteristics as pressure moderators

The level of institutional pressures exerted on firms to implement environmental practices varies across different countries and industries due to diversified market characteristics (Rowley and Berman Citation2000). In light of this, several studies particularly confirm the role of industry (Gardberg and Fombrun Citation2006; Hoffman Citation2001; Rowley and Berman Citation2000; Sweeney and Coughlan Citation2008) and operating country (Delmas Citation2002; Srivastava and Srivastava Citation2006; Yalabik and Fairchild Citation2011) in moderating the level of institutional pressures. However, even for companies operating within the same institutional context, the level of pressures exerted on them fluctuates due to their distinct firm characteristics, as noted by Delmas and Toffel (Citation2004, 219). Accordingly, the literature highlights the role of visibility (Delmas and Toffel Citation2004; Gardberg and Fombrun Citation2006; González-Benito and González-Benito Citation2006; Hoejmose, Brammer, and Millington Citation2012; Rowley and Berman Citation2000), internationalisation (Delmas and Toffel Citation2004; Levy and Rothenberg Citation2002; Zyglidopoulos Citation2002), size (Arvidsson Citation2010; Delmas and Toffel Citation2004; Rowley and Berman Citation2000; Zhu and Sarkis Citation2007), historical environmental performance (Delmas and Toffel Citation2004; Rowley and Berman Citation2000), and brand reputation (Rowley and Berman Citation2000) in moderating the level of pressures on firms. We sought experts’ opinions to limit the number of factors in this study, which was mainly to: (i) set the boundaries for this research, and (ii) to ensure relevance of the factors in the contract logistics context (see Methods for more details). We selected the factors that overlapped between the literature and experts’ opinions (), resulting in the following five firm and market characteristics: industry, operating country, visibility, internationalisation and size. These are considered as pressure moderators in this study, and each will be explained in detail next.

Table 1. Factors to be considered under pressure moderators.

2.2.1. Industry

Different industries have unique supply chains and thus are subject to distinct environmental demands. Companies whose core activities are associated with high environmental impact, such as those operating in the oil and steel industries, are expected to demonstrate a high level of responsibility in the way they conduct their business (Gardberg and Fombrun Citation2006; Hoffman Citation2001). In contrast, companies with less of an environmental impact, such as banks or insurance companies, experience lower expectations and pressures to act responsibly (Gardberg and Fombrun Citation2006). To verify this, Sweeney and Coughlan (Citation2008) performed a content analysis on sustainability reports of 28 firms operating within different industries. Their results highlight a significant variation in firms’ environmental and social disclosure due to different stakeholders’ expectations across those industries.

2.2.2. Operating country

The country where a company operates plays an important role in moderating the level of pressure exerted on it. Yalabik and Fairchild (Citation2011) find that firms operating in developed countries are under higher competitive pressures than firms operating in countries with more relaxed environmental laws. A different outcome was reported by Delmas (Citation2002), who deployed an institutional viewpoint to study the drivers to implement the ISO 14001 certificate in different parts of the world. Her results show that a significant number of companies have adopted ISO 14001 in Western Europe and Asia, whereas very few American companies have. She relates this to the effect of regulatory, normative and cognitive aspects of the institutional environment in a specific country on the costs and potential benefits of acquiring the certificate. Another example is provided by Srivastava and Srivastava (Citation2006), who argue that reverse logistics practices are ‘regulatory-driven’ in Europe, ‘profit-driven’ in the United States, and in an emerging phase in other parts of the world such as India.

2.2.3. Visibility

It is commonly acknowledged in the literature that ‘highly visible’ firms that operate in business-to-consumer (B2C) markets engage in environmental practices more intensively and proactively than those operating in business-to-business markets (B2B) (Delmas and Toffel Citation2004; Gardberg and Fombrun Citation2006; González-Benito and González-Benito Citation2006). The reason is that B2C actors have stronger incentives to act sustainably, being exposed to relatively high stakeholder expectations (González-Benito and González-Benito Citation2006). Hoejmose, Brammer, and Millington (Citation2012) attempted to authenticate this argument by surveying 340 buyer-supplier relationships (i.e. B2B relationships). They found that adopting green practices is rather ‘neglected’ in the B2B sector due to the distance from end consumers and lack of visibility. However, they suggest that facilitating successful environmental practices in B2B contexts requires sufficient top management support on green issues. Within shipper-LSP relationships, Kudla and Klaas-Wissing (Citation2012) find that shippers operating in B2C and ‘reputation-sensitive’ markets in particular demonstrate high interest in LSPs’ sustainability programmes.

2.2.4. Internationalisation

Whether a particular company is operating locally or internationally has an influence on the level of pressure exerted on it. Zyglidopoulos (Citation2002) and Levy and Rothenberg (Citation2002) argue that multinational companies are often subject to higher standards for social and environmental responsibility than their national counterparts due to their exposure to additional pressures from stakeholders in all the countries where they operate. Zyglidopoulos (Citation2002) links the formation of a more restrictive multinational atmosphere in terms of social and environmental responsibility to two mechanisms: international reputation side effects (i.e. judgement by international reputation even if a certain subsidiary operates responsibly) and foreign stakeholder salience (i.e. additional pressure exerted by stakeholders within a subsidiary’s location).

2.2.5. Size

Delmas and Toffel (Citation2004) stress that large market leaders in terms of revenue, market share or total assets are more prone to stakeholders’ pressure to act sustainably than small firms. This is because large companies are more exposed to public scrutiny and are thus likely to experience more social and political pressures (Arvidsson Citation2010). Zhu and Sarkis (Citation2007) stress that regulatory and market pressures may influence large firms, whereas small firms are more likely to be influenced by competitive pressures. Within the logistics industry, Kudla and Klaas-Wissing (Citation2012) argue that large LSPs are subject to slightly more intensive market pressure to act sustainably than are small and medium-sized LSPs.

2.3. Managerial commitment as a response moderator

Institutional forces are ‘transformed’ once they penetrate a firm’s boundary, because they are filtered and interpreted by managers in correspondence to the firm’s unique background and culture (Levy and Rothenberg Citation2002; Liu et al. Citation2010). This is crucial; when two firms are subject to the same level of pressure, they tend to respond differently (Sharma and Starik Citation2004). Two questions, however, arise alongside this notion. First, what are the factors that influence the managerial responsiveness to pressures? Second, do managers simply play reactive roles by responding to the pressures imposed, or is there room for proactivity? Institutional theory does not seem to provide answers for neither of these questions, as it ignores the role of managerial commitment in influencing the firm’s responsiveness (Colwell and Joshi Citation2013; Dacin, Goodstein, and Scott Citation2002; Kostova and Roth Citation2002), thus diminishing the chance of proactivity within environmental decisions.

Institutional theorists have both recognised these issues and proposed ways to overcome them. That is, it is acknowledged that organisations differ in the way they pursue a particular institutional practice and in their ability to institute organisational change (Delmas and Toffel Citation2008; Hoffman Citation2001). We draw from different sources of environmental management and GSCM literature (Ahmad et al. Citation2016; Branzei and Vertinsky Citation2002; Campbell Citation2007; Carter and Dresner Citation2001; Chan et al. Citation2012; Dai, Montabon, and Cantor Citation2014; Greenwood and Hinings Citation1996; Hillary Citation2004; Kudla and Klaas-Wissing Citation2012; Lieb and Lieb Citation2010; Maignan and Ralston Citation2002; Marchet, Melacini, and Perotti Citation2014; Piecyk and Björklund Citation2015; Sharma Citation2000; Zhu, Sarkis, and Geng Citation2005; Zsidisin and Siferd Citation2001) five factors that are particularly critical in influencing managers’ commitment in their response to external pressures: (i) interpretation of pressures, (ii) top management support, (iii) economic condition, (iv) organisational structure, and (v) collaboration opportunities. We argue that these factors influence the role of managerial commitment in moderating the firm’s environmental responsiveness (via adopting GSCM practices), in which the higher the commitment by managers, the higher the expected responsiveness, which could potentially lead to proactivity. Like the case with pressure moderators, selecting these factors was supported by experts’ opinions (). Each of the selected factors is explained in detail next.

Table 2. Factors to be considered to influence the response moderator.

2.3.1. Interpretation of pressures

Playing a reactive role by solely complying with pressures does not guarantee enhanced environmental performance. These pressures need to be coupled with a proactive attitude to trigger successful sustainable projects (Branzei and Vertinsky Citation2002; Carter and Dresner Citation2001). Such proactivity depends on whether managers perceive pressures as threats or opportunities, argues Sharma (Citation2000), whose survey aimed at identifying the factors affecting managers’ interpretation of pressures. He finds that managerial interpretation of environmental issues as opportunities is positively correlated with implementing environmental strategies, in which interpreting them as opportunities relies on two elements: (i) the legitimacy of environmental issues on hand, and (ii) the degree of discretionary slack afforded to managers to deal with sustainability concerns. Likewise, Maignan and Ralston (Citation2002) argue that managers are motivated to behave responsibly when they believe that such behaviour enhances the financial performance of their firms.

2.3.2. Top management support

Top management is perceived as a key influencer in shaping organisational values and strategies (Hambrick and Mason Citation1984; Hart Citation1992). This indicates that when top management’s focus is directed towards green objectives, managers and employees within different levels of the firm tend to engage further in green initiatives (Ahmad et al. Citation2016; Dai, Montabon, and Cantor Citation2014; Zsidisin and Siferd Citation2001). Zhu, Sarkis, and Geng (Citation2005, 453) argue that top management should be ‘totally committed’ to ensure complete environmental excellence. In contrast, lack of top management support is viewed as a main barrier to successful environmental practices (Hillary Citation2004). However, the influence of top management support seems to be sensitive to the visibility of the firm: Hoejmose, Brammer, and Millington (Citation2012) find that top management support is a key driver for engaging in GSCM practices among B2B firms but less important among B2C ones, reasoning that GSCM practices are not constrained by strategic imperatives in the B2B sector.

2.3.3. Economic conditions

The economic conditions of a company (particularly financial performance and level of competition) influences the chance that its managers will behave responsibly (Ahmad et al. Citation2016; Campbell Citation2007; Chan et al. Citation2012). According to Campbell (Citation2007), experiencing weak financial performance or too high/low level of competition minimises this chance, whereas having a ‘healthy’ economy and a moderate level of competition often increases the chance. The main reason relates back to the slack resource theory (Ullmann Citation1985; Waddock and Graves Citation1997), which entails that firms who are less profitable possess fewer resources to spare for social and environmental activities than firms that are more profitable (see Orlitzky, Schmidt, and Rynes Citation2003 for more details). However, Campbell (Citation2007) also argues that economic conditions are less effective in influencing mangers’ decisions when a company is subject to high regulatory and monitory pressures.

2.3.4. Organisational structure

Organisational structure and complexity also influence managerial responsiveness to pressures. Ahmad et al. (Citation2016) emphasise the importance of cross-functional integration between different departments to counter such complexity and successfully incorporate GSCM practices. Taking the logistics industry as an example, Kudla and Klaas-Wissing (Citation2012) argue that large LSPs can be slow to react to sustainability requirements due to their complex organisational structures and inefficient internal communication among their departments (e.g. sales, operations, sustainability). In contrast, small and medium-sized LSPs, such as family-run companies, are more likely to behave responsibly due to clear and flat hierarchies, direct top management support of sustainability actions and altruistic drivers (ibid.).

2.3.5. Collaboration opportunities

Keeping the focus on the logistics industry, many scholars (e.g. Lieb and Lieb Citation2010; Marchet, Melacini, and Perotti Citation2014; Piecyk and Björklund Citation2015) argue that it is mostly large LSPs that adopt environmental initiatives, whereas small and medium-sized LSPs lag behind. The main reason is that large LSPs enjoy a better access to partnerships and collaborations on sustainability efforts, where they work more closely with customers, regulators, transporters, universities, and trade associations, which keeps them abreast of the latest advancements due to greater access to data, experience and larger networks (Lieb and Lieb Citation2010).

2.4. Conceptual framework

demonstrates the main conceptual framework of this study. It depicts the three types of institutional pressures (regulatory, market, competitive) that drive firms to adopt GSCM practices, in which the level of these pressures is moderated by firm and market characteristics (industry, operating country, visibility, internationalisation, size). As explained earlier, firms tend to respond differently even if they are exposed to the same level of pressure, due to the moderating effect of managerial commitment on environmental responsiveness. The role of managerial commitment takes place after the pressures cross the firm’s boundary, and it is influenced by the factors: interpretation of pressures, top management support, economic conditions, organisational structure and collaboration opportunities.

In general, the framework can be applied to any company within the supply chain that is expected to engage in GSCM practices, which typically includes shippers and LSPs, since they are both active players in supply chains, and both are subject to institutional pressures to act in an environmentally friendly manner (which comprises buying/offering green logistics). Certainly, the level of pressure experienced to engage in green logistics practices differs among them, mainly due to their diverse industries as well as their different roles as buyer or provider.

To further explain the framework in relation to shippers and LSPs: shippers are influenced by institutional pressures to implement GSCM practices, whether these practices are conducted internally within a firm’s boundary or externally through collaboration with external partners (Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2013). External GSCM practices covers purchasing green logistics services (Min and Galle Citation1997; Pazirandeh and Jafari Citation2013). Seuring and Müller (Citation2008) argue that companies hand the pressure down to their suppliers through the downstream supply chain. Following this logic, shippers transfer a portion of the pressure exerted on them onto LSPs by demanding green logistics services.

LSPs are also influenced by institutional pressures to implement green logistics practices (Colicchia et al. Citation2013; Kudla and Klaas-Wissing Citation2012). For them, the pressure from their shippers constitutes market pressure (Colicchia et al. Citation2013), i.e. LSPs’ business customers are always shippers. We relied on Perotti et al. (Citation2012) to provide examples of green logistics practices, since their extensive literature review highlights the main environmental initiatives implemented by LSPs while grouping them into distinct categories (). Note that these practices could be implemented in response to pressures experienced by LSPs (e.g. shippers’ demands) or simply triggered by LSPs’ proactive behaviour.

Table 3. Examples of LSPs’ green logistics practices (Perotti et al. Citation2012).

3. Methods

Case studies enable gaining a profound understanding of logistics antecedents (Frankel, Naslund, and Bolumole Citation2005) and are particularly encouraged when investigating interactions among shippers and LSPs (Selviaridis and Spring Citation2007). Because this research aims to provide an in-depth investigation onto how institutional pressures influence shippers and LSPs to engage in green logistics, we chose a case study approach. Ketokivi and Choi (Citation2014) classify case research into three distinct modes: theory generation, theory testing and theory elaboration. The latter appears to appropriately represent this study; theory elaboration implies applying an existing general theory to an under-researched context to attain premises that can be used in aggregation with the general theory (Ketokivi and Choi Citation2014). One might question why theory testing was not the selected approach; theory testing requires obtaining sufficient premises already in the theoretical phase of the research, and then testing them empirically (Ketokivi and Choi Citation2014). Since the context of this study (i.e. the influence of pressures and moderators on shippers/LSPs) is not well-established in the contract logistics literature yet, forming sufficiently detailed premises to deduce testable hypotheses was not achievable at the current stage.

Due to the lack of well-developed theoretical frameworks that identify the factors to be included under pressure/response moderators on shippers/LSPs in particular, we expanded our research by looking into broader disciplines, mainly within the domains of environmental management and GSCM. Various factors were found under these disciplines (see and ). To ensure covering the factors that are most relevant to our study, we sought experts’ opinions, in a fashion similar to a Delphi approach. This helped in enhancing the content validity of the selected factors (Flynn et al. Citation1990), and set the boundaries for the research. Four experts with substantial experience in the supply chain management and contract logistics fields were asked to identify (i) the main firm and market characteristics that would moderate the pressures on firms to adopt GSCM practices, and (ii) the main factors that influence firms’ managerial commitment to engage in such practices. The questions were asked in subsequent rounds until a consensus among the experts was reached, in line with Flynn et al. (Citation1990). Then, we highlighted the factors that overlapped between the literature and experts’ opinions, yielding five factors under each subgroup, as shown in and . However, limiting the number of factors, although useful for focusing the research, bears a limitation of excluding other factors that might be of relevance. We therefore encourage testing the influence of the other extracted factors (e.g. brand reputation, historical environmental performance) in further studies, which might offer an expansion to our framework.

3.1. Case selection

Multiple-case studies are generally favoured over single cases because they enhance the external validity and rigour of the research (Yin Citation2009). Accordingly, we approached eight case companies, three shippers and five LSPs. Not having dyadic relationships as the unit of analysis enabled us to focus on the two supply chain actors separately through analysing the pressures and moderators experienced by each as a first step, and then drawing comparisons between them based on their different buying/selling roles as a second step. Further, limiting the study to dyads would restrict conceptualising the externalities influencing each of the actors in their GSCM decisions, as shippers and LSPs (particularly large ones) often form numerous partnerships with various logistical partners.

Finding suitable cases with resemblances between them is required in the case selection process to enhance the generalisability of outcomes (Yin Citation2009). Hence, all the approached shippers are large, possess known brands, demonstrate sustainability awareness on their business profile, operate globally and outsource logistics activities to LSPs. By this, they exemplify typical multinational companies that pay attention to environmental sustainability and may reflect this in their logistics purchasing behaviour. However, since this research suggests that various firm characteristics and backgrounds (i.e. pressure and response moderators) influence institutional pressures and environmental responsiveness, we also intended to discover contrasting patterns in the data sample when selecting the cases (in line with Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007). Accordingly, the three shippers in the sample operate in diverse industries (mining and materials technology, telecommunication equipment, food and salted snacks) that are associated with varying environmental risks and different proximities to end consumers. By the same logic, the approached LSPs have different sizes, geographical coverages and product portfolios (within logistics offerings), whereas all of them exhibit environmental sustainability alertness on their websites and deal with a wide range of shippers (small and large ones). The contrasting characteristics of the LSPs allowed analysing the different pressures and moderators, yet the LSPs are expected to offer green logistics services to a diversity of customers with different green demands. provides information about the cases and their participants, noting we agreed with them on anonymity. The business units in the sample operate within Swedish and German markets, two countries that actively engage in environmental debates (EPI Citation2016), which appears relevant to our purpose. However, we recognise the risk of limited generalisability due to confining the sample to these countries. Even among the considered industries for shippers, each was represented by one case only, thus generalisation cannot be claimed on their entire industries. In addition, due to the extreme difficulty in finding cases that cover all firm and market characteristics provided in our framework (), our study will mainly illustrate the framework and elaborate the theory (as mentioned earlier). Further empirical testing for the framework is recommended at a later stage.

Table 4. Case companies and participants.

3.2. Data collection and analysis

Data were collected mainly from interviews, as is common with case studies (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007). A total of 20 semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted, in line with Yin (Citation2009). For shipper companies, logistics and supply chain managers were interviewed, and those are acquainted with their companies’ sustainability strategies and responsible for procuring logistics services from LSPs. In turn, LSPs’ participants were mainly chief executives and environmental directors who interact with shippers (and governmental actors) and engage in environmental discourse with them. More information about the participants can be found in . Each interview lasted one to two hours, either face-to-face or via Skype (depending on accessibility).

The interview questions aimed to grasp the participants’ perceptions within six major categories:

General inquiry about the company and the participant’s role

General inquiry about environmental commitments adopted by the company

Main motives for adopting GSCM practices in general, and for purchasing green logistics services in particular (for shippers)

Main motives for conducting green logistics services (for LSPs)

Detailed questions about regulatory, market and competitive environmental sustainability pressures experienced by the company

Detailed questions about how firm’s characteristics and internal settings influence the pressures and responsiveness

Detailed questions about the company’s logistics partners (shippers/LSPs) and their environmental sustainability engagement with the company

17 of the interviews were permitted to be recorded, and all were backed by note-tacking. All interview recordings were fully transcribed and electronically filed to establish a trail of evidence (Yin Citation2009). The information obtained from the interviews was coded into different categories based on related subject areas, as advised by Voss, Tsikriktsis, and Frohlich (Citation2002). The software NVivo was used for the coding process, allowing multi-layer sub-categorisation, which in turn supported the analysis process. The categorisation was based on: (i) the role of the case company (shipper/LSP), (ii) the specific case company and (iii) the factors covered in the conceptual framework (). This allowed us to specify how each of the pressures and moderators influenced the actors’ green engagement on a case-wise and actor-wise basis.

There are two commonly recognised forms for determining institutional pressures: perceptual measures (based on participants’ viewpoints) and objective measures (based on private/public data sources). Capturing both is suggested to gain an inclusive understanding of the pressures (Delmas and Toffel Citation2004). However, perceptual measures often correlate with objective ones (Dawes Citation1999), and have been widely adopted in environmental management studies (e.g. Henriques and Sadorsky Citation1996; Min and Galle Citation1997; Zhu and Sarkis Citation2007). We assessed the pressures on firms through analysing the perceptions of the interviewed participants. To provide adequate depth for such analysis, we moved one step beyond determining whether the pressures are high or low. That is, we clustered the pressures into four categories based on their (i) timeliness, and (ii) effectiveness (see section 4.3 for details).

Information obtained from category vii (in interview questions) was used to further validate how the characteristics of an actor could moderate the pressures experienced by it based on the other actor’s viewpoint. For example, if LSPs indicated that large shippers are more demanding for green logistics services than small ones, such an argument provided supporting evidence for the shippers’ pressure moderator ‘size’.

The analysis of the data was carried out along two steps: within-case and cross-case, in compliance with Eisenhardt (Citation1989). The within-case analysis entailed writing up a storyline for each of the cases, whereas the cross-case step facilitated: (i) inspecting the cases against each other and (ii) matching evidence with the established theory. To facilitate the cross-case analysis, we constructed two charts (one for each actor) that depict the association of each of the cases with the studied factors (available in section 4.3). In addition, two tables (: Shippers; : LSPs) that summarise the findings from the cases are provided in Appendix.

To secure secondary data and enable triangulation, we accessed all the companies’ websites together with their corporate social sustainability (CSR) reports and supplier codes of conducts (CoC) – if available. The information obtained from these sources helped us to further validate the interviews’ information. For example, if participants from a shipper company expressed that no pressure on green logistics is passed down onto their LSPs, secondary documents (e.g. supplier CoC) were checked to validate this assertion.

The research material was sent out to the participants to ensure a correct understanding of their case-related data and to gain their final approval. Additionally, previous drafts of this paper were revised by research colleagues acquainted with the subject, which helped in reducing the potential bias of subjective analysis that is common in qualitative research.

4. Findings

This section presents a case-by-case summary of the findings (4.1: Shippers; 4.2: LSPs), followed by a cross-case representation (4.3).

4.1. Shippers

4.1.1. SI

The pressures on this Swedish global mining and materials technology firm to engage in environmental actions are mainly split between market (customers) and regulatory pressures – the former seems to dominate in driving the company’s green engagement. In contrast, competition was not expressed as an important driver for its green actions today; the global freight and customs manager noted, ‘since we’re B2B, I still think the bottom line [i.e. service level, cost] is more interesting for our customers, but environmental concerns will come more and more, and some customers will start pushing us soon in that area’. Environmental policies mainly concern the company’s production processes due to the high energy consumption and environmental impact associated with the steel and mining industry. This caused the firm to mainly direct its environmental focus to internal production issues. In terms of green logistics purchasing, operating from Sweden seems to stimulate its ambition; the participants expressed a willingness to comply with the Swedish target to reach a fossil-free transportation sector by 2030. In contrast, one participant explained how environmental logistics policies are more relaxed in, for example, Eastern and Southern European countries. This led to observing a lack of understanding of the company’s green demands by LSPs operating in those regions. A top managerial vision to preserve the environment triggers the company’s green initiatives, but the operationalisation of such initiatives in the logistics procurement process is difficult due to a complex organisational structure, as one participant noted, ‘we have four departments managing our logistics functions: sales, freight, finance and production, where they often have contradicting objectives when it comes to sustainability’. For example, the sales unit would prefer the fastest transport alternative to satisfy the customer, whereas the freight unit favours consolidating shipments to minimise cost. The company aims to compensate for its large environmental impact by demanding green logistics services from its LSPs, which comprises requesting trucks that meet high Euro standards and detailed calculations of CO2 emissions. Whereby, particularly large and global LSPs excel in complying with such demands. This shipper is an active participant in several workshops that shed light on green transport challenges, and these are often attended by LSPs, consultants and governmental representatives. Also, a willingness to pay extra for green logistics solutions was expressed once a direct relationship between cost and environmental performance was clarified by LSPs, though LSPs often lag in this area.

4.1.2. SII

This Swedish global telecommunication equipment provider finds the regulatory pressures exerted on it to engage in green logistics somewhat ‘loose’ and ‘could have been tougher’, as expressed by the head of distribution management. He also explained that the company is ahead of the environmental policy curve in most of the countries where it operates, although policies in developed European countries noticeably exceed those in developing ones. Regarding market pressure, customers’ green demands often concern the end product, due to the high energy consumption of telecom equipment, which directs the focus towards eco-design approaches. Moreover, SII’s customers (i.e. telecom operators) are increasingly requesting energy-efficient telecom equipment and networks powered by renewable energy grids in order to enhance their green image for their end users. Top management’s vision to preserve the environment is one of the main drivers for the company’s green engagement, which was emphasised in the company’s core values. In contrast, competition does not seem to be a driver for GSCM today (though expected to be in the future), nor to prioritise purchasing green logistics from LSPs, which was emphasised by one participant’s statement: ‘when I talk to the industry, most companies are acting in a similar way as us, they think it [the environmental concern] is important, but when they choose a global LSP to work with, it’s not the number one concern’. The company takes a global perspective when aiming to reduce the environmental impact associated with its logistics activities, which comprises utilising rail networks across Asia, providing technologies for vessel companies to help reduce their fuel consumption and reducing reliance on air shipments. However, the company puts ‘little’ pressure on LSPs to provide green solutions (i.e. no explicit green demands are in place), whereas cost and service levels occupy the highest priorities when selecting LSPs. However, one participant felt that more pressure on LSPs is needed to facilitate green improvements.

4.1.3. SIII

This German food and snacks producer faces tough regulatory pressures to implement environmental standards within the food production processes (e.g. reducing water consumption and chemical usage) due to the sensitivity of the food industry and the extensive scrutiny on it. Yet, little focus is directed towards how logistics functions should be handled. Logistics-related environmental policies were described as ‘not strict enough’. These limited policies are transferred without modification to LSPs, for example by requesting a certain type of Euro class trucks that are required by German laws. Competition was not perceived as a driver for GSCM nor green logistics purchasing. The company’s business customers (i.e. supermarket chains) do not prioritise green issues when goods are transported, because the focus is only on price and lead times. This has led the company to neglect such criteria when purchasing logistics services from its LSPs. The same issue was observed with its end consumers (i.e. buyers of snacks), whose interests do not stimulate the company’s GSCM nor green logistics purchasing initiatives. In addition, focusing only on price in negotiations with LSPs was partly linked to the company’s new organisational structure. As the supply chain manager stated, ‘the negotiations with our freight forwarders are moving out from our logistics department into the procurement department (…) this means, for this other department, that it’s not really about operations, and doing business is all about the price’. The company has a strong top managerial focus on efficiencies and cost reduction when dealing with its LSPs, whereas environmental issues are seen as a ‘luxury’ topic. This lack of green engagement relates back to a tough economic condition experienced by the company, due to current high competition and tight profit margins within its segment.

4.2. LSPs

4.2.1. LSPI

This large global LSP offers integrated logistics solutions. Generally, operating in the logistics industry places it under high pressure. As the CEO stated, ‘the logistics industry is not very cherished because we’re creating pollution, traffic jams, noisy environment, etc. So everybody is pointing at us’. The participants expressed an influence by all three pressure sources (regulatory, market, competitive) to engage in green logistics. Of these, market pressure seems to dominate. This was evident by the sales director’s statement, ‘if the customer is willing to reduce its carbon footprint, the company will contribute as a response to the customer’s demands’. Further, it was explained that the company has played a proactive role during several endeavours (e.g. creating techniques to increase the load factor in trucks), but such proactivity was stimulated by the increasing customers’ demands that pushed the company to ‘think outside the box’, as stressed by the CEO. However, the participants expressed that most customers do not prioritise environmental concerns when buying logistics services, but the ones who do are often the large companies who also contribute to the majority of this LSP’s turnover. Besides size, several characteristics were outlined for environmentally conscious customers: operating in B2C sector, possessing popular consumer brands, enlisting on the stock exchange, operating internationally, operating in industries associated with high environmental impact via production processes (e.g. steel and pulp industries), or via their end products. All these actors ‘have much focus from outside on what they’re doing and cannot neglect sustainability’, as stated by the sales director. In addition, companies who are exceeding their financial targets are seen as more demanding of green logistics in comparison to underperforming ones, who tend to solely focus on cost reductions in their negotiations with this LSP. Operating from Sweden appears to play a role as well, where one participant explained that Nordic customers (including small and medium-sized ones) are at the forefront in demanding green logistics, which is not the case with U.S. or Asian customers, for instance. The role of competition in driving the LSP’s green engagement was acknowledged only when dealing with large companies, as noted by one participant, ‘if you want to be on the list of potential suppliers for the big companies then you have to have a program for sustainability’. Regulatory pressures do not seem central in driving the LSP’s green actions, as it considers the current policies rather ‘soft’ (e.g. no specific law to limit CO2 emissions is in place), and the LSP perceives itself way ahead of the current policies. Also, one participant explained that regulatory demands might have a ‘political touch’, making them less realistic and applicable in the logistics industry (e.g. prioritising railroad solutions at the expense of other efficient transport modes). The LSP has initiated a number of collaborative green projects with several organisations such as government agencies, universities, truck manufacturers and even logistics competitors. This enabled gathering all relevant stakeholders under one roof to trigger effective discussions. There is a ‘strong voice’ from top management that triggers sustainability initiatives across the LSP's departments, as conveyed by the environmental manager. Yet, such values seem associated with financial incentives, as stated by the CEO, ‘to be profitable tomorrow, we are convinced that we have to do a lot of proactive things; in the end we’re not giving away anything’.

4.2.2. LSPII

This large and global LSP engages in green logistics practices to satisfy three main stakeholder groups: customers, employees and investors, whereas legislators occupy a secondary rank, as expressed by the sustainability director. Several customers seem not only to request green solutions but also willing to pay a surplus charge for them. These are often the large customers, the ones incorporating clear sustainability values in their own vision, or the ones operating in B2C segments who are close to the end users. One example is the e-commerce customers, who focus on green measures to ensure that the purchased logistics services are clearly branded on the parcels delivered to their recipients. Meanwhile, the ones operating in B2B contexts tend to demand green services ‘selectively’. Regarding regulatory pressures, the company sees itself ‘beyond what every government is demanding’, which causes sort of ‘a comfortable situation’, although some countries have tougher regulations than others. However, the LSP utilises global standards to deal with the differing regulations, such as reporting via global reporting initiative (GRI) standards. The LSP perceives itself as ahead of competitors when it comes to green performance (e.g. achieving CO2 reduction targets). Despite its large size, the company tries to carefully manage its sustainable initiatives among its different departments. This is achieved by establishing networks driven by the topic; responsibilities are assigned in each business division and then broken down into regions and countries. However, some target conflicts between environmental management and sales departments were expressed by one participant. Achieving sustainability goals is supported by the top management’s attention on sustainability issues, where a dedicated council looks onto the overarching sustainability agenda of the company and reports directly to its top executives to ensure compliance.

4.2.3. LSPIII

This Swedish LSP offers warehousing and value-added services. Its CEO expressed a general ‘lack of interest’ from customers in demanding green solutions, especially when higher costs are associated. But few customers (often large and global ones, the ones within the B2C sector, or the ones operating in fast-moving consumer goods) emphasise green topics, and competition to satisfy this segment is expected to rise in the future. Although this LSP is ahead of environmental policies, being abreast with regulatory activities is part of its strategy, as expressed by the head of CR. He further explained that regulators’ focus is pointed towards the company due to its large size, making compliance an unescapable matter. The LSP’s green ambition is driven by a strong owner’s commitment to protect the environment while proactively exceeding legal requirements and market demands. As a result, a number of green warehousing practices are implemented, such as attaining an ISO 14001 certificate, harnessing renewable energies in buildings, enabling automatic on/off lighting in facilities and deploying waste recycling programmes. According to the CEO, two factors are seen as enablers for such applications: ‘common sense’ (i.e. human behaviour to preserve the environment) and ‘financial muscles’ (i.e. financial capacity to invest in green projects). It was expressed that the absence of transportation among its service offerings makes environmental compliance easier to attain due to: (i) the limited environmental risks in the warehousing industry compared with transportation and (ii) the narrowed managerial focus on resources and assets that are confined within the facilities’ boundaries. However, the LSP’s organisational complex structure makes it ‘difficult’ to follow up on sustainability measures and ensure their penetration across the organisation, as expressed by the COO.

4.2.4. LSPIV

This Swedish LSP specialises in providing local transportation services for heavy industries. Environmental protection is embedded in its corporate brand and core values; it strives to distinguish itself from competitors by operating trucks that run by renewable fuels (e.g. hydrotreated vegetable oil – HVO). Its strong green top managerial focus drove the company to move beyond customers’ requests by proactively offering solutions exceeding them. Large customers and the ones operating in industries with tangible environmental impact (e.g. paper industry) are often the ones prioritising green criteria when outsourcing to this LSP, whereas customers associated with low-value products (e.g. limestone industry) are seen as less green-demanding due to tight competition in their business segment. Regulatory pressure seems to play only a minor role in motivating this LSP’s green engagement, as it perceives itself ‘way above’ the local policies.

4.2.5. LSPV

This Swedish small-sized LSP offers warehousing and transportation services. Its green engagement is mainly driven by customers’ pressure, though only a few of them demand green services. These are described as the large companies that have a ‘bigger responsibility towards society’ and ‘produce a large carbon footprint’. Although this LSP is relatively small with limited resources, it still considers itself to be doing better than what the regulations in Sweden require. Competition does not appear to motivate its green engagement, due to the prevalence of price competitiveness in the logistics market. The generally low environmental pressure seems to position this LSP in a reactive role where it satisfactorily responds to policies and customer demands. Nevertheless, its slight managerial focus on sustainability led to implementing a number of internal environmental measures such as calculating CO2 emissions and switching lights off in warehouses. But these measures are seen as somewhat costly due to the additional human effort and time needed for following up with them.

4.3. Cross-case representation of findings

This section presents cross-case information to enable synthesising our empirical findings and displaying them in a systematic manner. The analysis of the findings will be carried out in the discussion section.

presents a group of characteristics outlined by shippers/LSPs about their logistics partners who tend to emphasise green concerns in their interactions. We used these characteristics to provide further validation and support for the influence of the pressures and moderators experienced by each actor on demanding/offering green logistics.

Table 5. Characteristics of shippers/LSPs who emphasise green concerns.

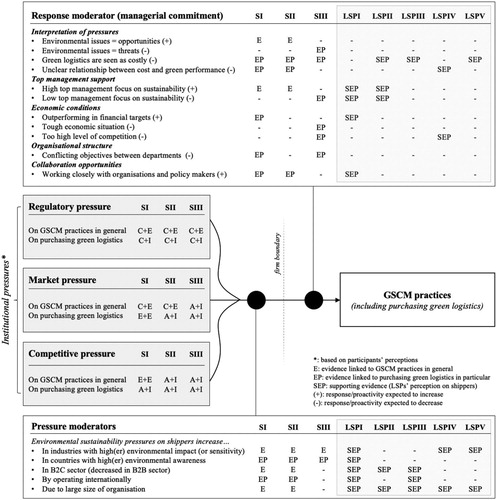

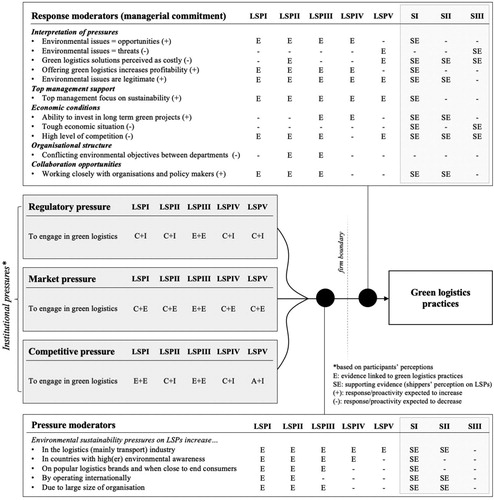

shows a chart that links each of the shipper cases with the studied factors, along with the supporting evidence provided by LSPs. First, the three pressure sources are assessed for each of the cases while distinguishing whether these pressures are related to GSCM practices in general and/or purchasing green logistics in particular. We assessed the pressures based on their timeliness and effectiveness, and categorised them as follows:

Current + effective (C + E): the company feels a current pressure, and responds to it through its activities.

Emergent + effective (E + E): the company anticipates that a pressure will emerge, and initiates preparations in response.

Current + ineffective (C + I): the company acknowledges a pressure, but does not view it as sufficient in affecting its activities.

Absent + ineffective (A + I): the company does not feel a pressure (this also includes when a pressure is emergent but ineffective in driving the company's activities).

in Appendix provides direct quotes from the interviews that justify the chosen category for each shipper case.

Evidence related to each factor under the pressure/response moderators is checked for each case, while also differentiating between GSCM in general (code: E) and purchasing green logistics in particular (code: EP). To explain, if the participants recognised an influence of a certain moderator in engaging in GSCM practices without highlighting its role in moderating green logistics purchasing behaviour, the code E will be given. Whereas, the code EP is given if the participants explicitly emphasised green logistics purchasing in relation to the moderator. Supporting evidence of LSPs’ perceptions on green demanding shippers is given the code: SEP. As an outcome, shippers engage in GSCM practices, which includes purchasing green logistics. Examples of these for each shipper case can be found in in Appendix.

We followed a similar approach for the LSPs’ chart (): the three pressure sources were assessed in driving the LSPs’ green logistics engagement (see in Appendix), and evidence for the pressure/response moderators in the cases was checked. The outcome here is green logistics practices, and examples of these are provided in in Appendix.

5. Discussion

This section provides a cross-case analysis of the cases of shippers and LSPs while reflecting on the established theoretical framework. We aim to analyse the pressures, pressure moderators and response moderator for (i) shippers to engage in GSCM practices and eventually purchase green logistics services and (ii) LSPs to engage in green logistics practices. Accordingly, a comparison between the two actors is established based on their different roles, which is later summarised in .

Table 6. Comparison between shippers and LSPs.

5.1. Institutional pressures

5.1.1. Regulatory

Shippers: our findings indicate that environmental policies affecting shippers mainly concern their own business practices and internal activities, whereas little emphasis is placed on how they should handle and outsource their logistics functions. For instance, logistical environmental policies were described as ‘loose’ (SII) and ‘not strict enough’ (SIII), and all the shippers expressed that tougher regulations would motivate them to put higher green demands on LSPs. This implies that shippers’ engagement in green logistics purchasing activities does not appear directly driven by regulations, as these mainly concern industry-specific functions. Such findings complement Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai (Citation2013), who stress that institutional pressures drive firms to mainly adopt internal GSCM practices, and not external ones.

LSPs: although regulatory pressures seem to form a driver for LSPs to engage in green logistics, all the studied LSPs (large and small ones) indicated that they are ahead of the imposed policies (globally and locally), creating a sort of ‘comfortable situation’. This is surprising in two ways: first, the business units within the studied LSPs are located in countries with relatively high focus on environmental issues (Sweden, Germany), and if the regulations in such countries are not tough enough to push LSPs to go greener, then perhaps a general lack of global initiatives is the case. Second, the findings challenge many studies that consider regulatory pressures as a ‘key’ driver for LSPs’ green engagement (e.g. Lieb and Lieb Citation2010; Lin and Ho Citation2011; Rossi et al. Citation2013), especially in countries taking the lead on environmental change. However, the case might be that the studied LSPs are already aware of the governmental concerns on environmental topics, and thus moved from a reactive role towards a proactive one by taking initiatives surpassing the imposed policies.

5.1.2. Market

Shippers: customers’ green demands represent a main driver for SI and SII to engage in GSCM practices. Similar to regulatory pressure, most of these demands are industry-specific and not logistics-related. For example, SII expressed how its customers’ green demands relate to its end-product design due to the high energy consumption of telecom equipment. Absence of logistical focus within market pressure was also seen with SIII, where its customers (e.g. supermarket chains) prioritise cost and speed of delivery with no attention to environmental matters. This could relate to the lack of regulatory pressures on shippers concerning logistics functions, as firms often demand their suppliers to comply with the environmental policies applicable in their specific fields (Seuring and Müller Citation2008).

LSPs: unlike regulatory pressure, market pressure (i.e. shippers’ demands) seems to play a key role in motivating LSPs’ green logistics engagement, thus confirming previous literature (Evangelista Citation2014; Lieb and Lieb Citation2010; Rossi et al. Citation2013; Wolf and Seuring Citation2010). However, the findings from LSPs suggest that only few shippers (characterised in ) put strong pressure on green requirements. But these, according to the LSPs’ viewpoint, are also the large ones who often contribute to the majority of LSPs' revenues. This appears to drive LSPs to offer green solutions to attract/satisfy these large buyers as a way increase profitability.

5.1.3. Competitive

Shippers: competing via offering green products and solutions was found to potentially drive SI to differentiate itself over the long term only, whilst not representing a competitive edge to secure business deals today. However, competition did not form a driving force for neither SII nor SIII to engage in GSCM practices. Also, it was not found to drive any of the study’s shippers to purchase green logistics from LSPs.

LSPs: all the studied LSPs (except for LSPIV) expressed that competing with their rivals is mainly based on price and service levels and not environmental issues (except when dealing with large shippers, as seen with e.g. LSPI). Yet, and as seen with LSPI and LSPIII, a trend of ‘green competitiveness’ is growing over the long term (in line with Colicchia et al. Citation2013), aiming to attract environmentally conscious shippers. The lack of high competitive pressure on LSPs was attributed to one of two reason: (i) a lack of green interest by many shippers (expressed by LSPI, LSPIII and LSPV), or (ii) perceiving oneself ahead of competitors (expressed by LSPII and LSPIV). Shippers’ pressure on low prices appears to shift the LSPs’ focus away from green competition, especially due to their limited capacity to invest in green projects – given the tight profit margins in the logistics industry.

5.2. Pressure moderators (firm and market characteristics)

5.2.1. Industry

Shippers: the three shipper companies in our sample belong to three different industries. These companies described the pressures on them to engage in GSCM in relation to their industries as follows: (i) SI (mining and material technology) expressed increased pressures due to the large environmental impact of its production processes, (ii) SII (telecommunication equipment) expressed increased pressure due to the high energy consumption of its end products, and (iii) SIII (food and snacks) expressed increased pressures due to the high sensitivity of its end products. Linking increased pressure to large environmental impact is supported by LSPI, LSPIV and LSPV when describing their environmentally conscious shippers (), and is in line with previous literature (Gardberg and Fombrun Citation2006; Hoffman Citation2001). Whilst linking increased pressures to energy consumption of end products is supported by LSPI and LSPV. Spotting supporting evidence from LSPs might suggest that when shippers cause large environmental impact (via operations or end products), they not only receive increased pressure to mitigate their impact but also tend to react by finding ways to compensate such impact through green logistics purchasing. The weak link between GSCM and green logistics purchasing found with SIII may be because of the nature of the food industry: although highly scrutinised, does not necessarily entail a large environmental impact, hence a feeling to compensate through buying green logistics does not seem as crucial.

LSPs: in general, the logistics industry is portrayed as an environmentally detrimental industry due to its association with high pollution and emissions, placing LSPs under strong pressure by external stakeholders. However, the pressures on LSPs diverge based on their different product portfolios: LSPs offering transportation services (e.g. LSPI, LSPII, LSPIV and LSPV) seem to witness stronger pressures than LSPs not offering them (e.g. LSP III, which offers warehousing and value-added services). This is not surprising, as among logistics activities, only 9–10% of the overall emissions are emitted from logistics warehouses, whereas the rest come from transportation activities (McKinnon et al. Citation2015).

5.2.2. Operating country

Shippers: in line with previous literature (Delmas Citation2002; Yalabik and Fairchild Citation2011), the cases suggest that operating in environmentally aware regions (e.g. Sweden and Germany) might increase the regulatory and market pressures to engage in GSCM practices, and possibly, to engage in green logistics purchasing practices. For instance, SIII demands trucks with certain Euro standards from LSPs just to comply with the imposed German regulations. Similarly, SI’s green logistics purchasing decisions are stimulated by the Swedish national targets to achieve fossil-free transportation by 2030. Such a notion is further supported by LSPI, who asserted that Nordic shippers demand green logistics services more than U.S. and Asian ones do, which could be attributed to the higher pressures they experience in the first place. In contrast, all the studied shippers expressed some sort of leeway within green logistics obligations in countries with relatively less environmental focus, such as Eastern European countries.

LSPs: our findings confirm that the region where an LSP operates influences the level of pressures exerted on it, as noted by the global LSPI and LSPII. For instance, LSPI’s participants expressed that its environmental development pace differs across the various geographical markets where it operates due to diversified policies and market demands (as explained above). For the other local LSPs in the sample, such as LSPIII and LSPIV, operating from Sweden is found to influence their green engagement in conjunction with the Swedish governmental focus on environmental issues. Yet, regulations on green logistics were portrayed as soft and easy to fulfil – calling for more regulatory intervention in this area.

5.2.3. Visibility

Shippers: comparing the two B2B shippers in our sample: SI expressed that the bottom line (cost and service levels) occupies its customers’ top priority, whereas green measures are minimally considered. In contrast, SII explained how its customers put quite high emphasis on green measures. This difference might relate to their varying proximities to end users. To explain, SII’s customers are telecom operators (B2C) who request specific measures to enhance their green image among their end consumers (mobile phone users). Whereas, SI’s customers operate in heavy B2B segments (e.g. machining, oil and gas) that are quite far from the end user, where a need to enhance their green image did not seem as vital. These findings could further elaborate the common argument in the literature: B2C actors are exposed to more pressures than B2B ones (Delmas and Toffel Citation2004; Gardberg and Fombrun Citation2006; González-Benito and González-Benito Citation2006). That is, it seems that even among B2B actors, the level of pressure may vary in proportion to proximities to end users, in which the closer the business is to the end user, the more pressure it might experience to engage in GSCM practices. Although it was not found in the shippers’ cases how these pressures are linked to green logistics purchasing, the way LSPI, LSPII and LSPIII described their environmentally conscious shippers provides a possible connection (). For instance, LSPII expressed that shippers with direct contact with end users (e.g. e-commerce firms) purchase green services to have green labels placed on the parcels delivered to their recipients, whereas B2B shippers who operate far from end users tend to purchase green services ‘selectively’. However, exceptions to this were found: Shipper III (B2B/B2C) was neither influenced by its business customers (supermarket chains) nor end consumers (buyers of snacks) to purchase green logistics, which might be attributed to the relatively low environmental risks associated with the food industry.

LSPs: although most of the LSPs in the sample operate in mainly B2B contexts, it was found that LSPs who possess popular brands (LSPI, LSPII and LSPIII; supported by SI) were subject to relatively strong pressures due to their susceptibility to increased public criticism. In addition, and similar to shippers, the cases (e.g. LSPII) indicate that the closer the LSP is to the end user the more pressure it receives from its customers (as explained above).

5.2.4. Internationalisation

Shippers: the two global shippers in our sample (SI, SII) demonstrated caution and attendance to environmental topics in an international prospect. For example, SII expressed a global sense of responsibility towards environmental logistics issues, leading it to react by implementing certain global measures such as utilising rail networks across Asia and reducing reliance on air shipments in its cross-border deliveries. The role of internationalisation in increasing environmental sustainability pressures is endorsed by the literature (Levy and Rothenberg Citation2002; Zyglidopoulos Citation2002), and its linkage to purchasing green logistics is supported by LSPI and LSPIII ().

LSPs: as found with the global LSPs in the sample (LSPI and LSPII), operating internationally seems to expose them to increased pressures, because they are expected to comply with all market and regulatory demands in each country they operate in. This applies the views of Zyglidopoulos (Citation2002) and Levy and Rothenberg (Citation2002) on the contract logistics literature. Coincidentally, global LSPs are also the ones at the forefront in proposing green initiatives (supported by SI, SII; Lieb and Lieb Citation2010), and these ones in our sample expressed a feeling of ‘comfort’ in complying with the present policies. For instance, LSPII perceives itself ‘beyond what every government is demanding’. Nevertheless, internationalisation seems to pose a difficulty for LSPs due to the lack of unified global standards imposed by regulators and shippers, which highlights a need for facilitating more standardised initiatives such as the GRI standard.

5.2.5. Size

Shippers: two of the large shippers in our sample (SI, SII) expressed relatively increasing pressures on them to engage in GSCM practices. This might relate to their prominence and large market share, which could lead to high exposure to public criticism, as explained by Arvidsson (Citation2010) and Delmas and Toffel (Citation2004). In addition, and according to all the LSPs in the study (), large shippers are found at the forefront in demanding green logistics services, which may be a result of strong pressures they experienced originally.

LSPs: in line with Kudla and Klaas-Wissing (Citation2012), large LSPs experience more pressures to act responsibly than small and medium-sized ones, and this was evident in the cases through two scenarios: (i) large size in terms of market share indicates a large customer portfolio and thus more diversified demands that need to be fulfilled (expressed by LSPI and LSPII), and (ii) large size in terms of assets and number of employees exposes LSPs to more scrutiny, which leads to greater public attention (expressed by LSPIII; supported by SI and SII). These two scenarios complement the notion of Zhu and Sarkis (Citation2007) that regulatory and market pressures typically influence large firms.

5.3. Response moderator (managerial commitment)

Based on our theoretical framework (section 2.3), managerial commitment moderates the environmental responsiveness of a firm, whereas such commitment is influenced by mainly five factors. Each of these factors is analysed in relation to our findings next.

5.3.1. Interpretation of pressures

Shippers: according to Sharma (Citation2000), perceiving environmental issues as opportunities increases a firm’s adoption of environmental strategies, whereas viewing them as threats decreases it. In this study, both SI and SII expressed that engaging in green actions could lead to enhanced profitability, leading them to incorporate GSCM practices in their portfolio in an attempt to attract customers over the long run. However, all the studied shippers perceived green logistics solutions as costly. For instance, SIII views green issues as a ‘luxury’ that does not help the business case. This attitude has caused its lack of engagement in requesting green logistics. For SI and SII, a direct relationship between cost savings and environmental performance when purchasing logistics from LSPs was not clearly acknowledged, resulting in a reluctance to engage further in green logistics purchasing practices.

LSPs: four out of five LSPs in the sample view green strategies as a way to increase profitability over the long run due to the anticipated rise in green demands in the future. Those are also found to demonstrate further engagement and proactivity in green logistics practices. LSPV, in contrast, views green initiatives as a burden with additional costs, which might explain its limited engagement. Sharma (Citation2000) denotes that legitimacy of environmental issues increases the chance of viewing environmental issues as opportunities. All the participants within the approached LSPs showed sensitivity to the detrimental nature of logistics activities to the environment, implying their consideration of environmental issues legitimate. This could explain LSPs’ proactivity to implement green initiatives beyond the imposed policies and customer demands, as observed with some LSPs in the sample (e.g. LSPIII and LSPIV).

5.3.2. Top management support

Shippers: SI and SII experience a strong top managerial focus on green topics, which was also reflected by both companies’ core values. This, as conveyed by the interviewed managers, created a motivational atmosphere for their green engagement, as they strived to align their performance and decisions with top management’s ambitions. Such findings conform with previous literature (Ahmad et al. Citation2016; Zhu, Sarkis, and Geng Citation2005). In contrast, and in line with Hillary (Citation2004), lack of top management support appears to clearly demotivate managers within SIII to engage in green initiatives, as the focus was solely on cost reduction strategies. However, even when the support is there, it does not seem necessarily related to purchasing green logistics; no emphasis on green logistics was detected on neither of SI’s or SII’s values and strategies, nor was that emphasised by the participants’ input.

LSPs: similar to shippers, the influence of top management support was evident by all the LSP cases. However, evidence from LSPI, LSPII, LSPIII and LSPIV shows that top management demonstrates such awareness not only to protect the environment, but also due to a belief that such engagement would attract more customers and increase profitability.

5.3.3. Economic conditions

Shippers: the tough economic situation experienced by SIII due to high competition in its segment has shifted the company’s focus from green measures to cost-cutting strategies, which resulted in adopting a strictly reactive approach by minimally complying with the imposed policies to maintain its license and avoid penalties. This scene complements the argument of Campbell (Citation2007), who asserts that too high (or too low) a level of competition decreases the chance of responsible behaviour, which also seems to explain SIII’s lack of interest in requesting green logistics from LSPs. In contrast, SI expressed a willingness to pay more for green logistics solutions, which might indicate a healthy financial situation. Such a notion was further supported by LSPI, asserting that shippers that are outperforming financially tend to request green logistics services.