ABSTRACT

This paper uses empirical evidence to explore the nature of employment transitions for a cohort of marginalised young people in England. The findings presented reveal the importance of past experiences, largely determined by prevailing opportunity structures, in shaping the present and reiterate the need to see transition as a historical process. Longitudinal data collected as part of an evaluation of a youth employment programme called Talent Match provides the evidence for the paper. The routes participants took in terms of securing and sustaining employment are examined. The paper develops a typology of different transitional groups to explore these routes based on the movement (or lack of) into and out of employment. The relative importance of different factors in explaining the groupings are assessed, with results underlining how the ongoing change participants were encountering in the present was inextricably linked to their past. In response, this paper suggests a reemphasis on understanding youth as both a stage of ‘being’ and ‘becoming’, seeing youth as both a condition in its own right but also part of the life course process, and calls for a more dynamic understanding of youth transitions among policymakers and those designing youth employment programmes.

Introduction

It is widely argued that since the 1970s youth transitions in ‘advanced capitalist societies’ have become increasingly complex, protracted and non-linear (McDowell Citation2002; Furlong and Cartmel Citation2007; Thompson Citation2011). The transitional period between childhood and adulthood has extended, in terms of the move from education to employment, the passage to independent housing, and family formation (McDowell Citation2002; Calvert Citation2010).

This paper is concerned with a specific sub-group of marginalised young people in England who engaged with an employment programme called Talent Match (TM), the routes they took in terms of securing employment and whether this was sustained. Empirical data from a longitudinal dataset is utilised to examine the transitions into work (or not) made by this sub-group. The paper looks specifically at whether this group experienced the complex employment transitions the literature indicates you would expect. The rare dataset provides a unique insight into the experiences of almost 2000 young people who were typically unemployed for 12 months or longer and faced multiple barriers to employment. With this group also often hidden from the sight of official statistics, the analysis presented makes an important empirical contribution to the literature examining how youth transitions are understood today.

The development of a heuristic typology also makes a methodological contribution to a growing body of quantitative work focusing less on single-status changes, instead deploying more processual approaches to understanding youth transitions. A sample of young people are followed, both during their time on the programme and beyond, with a wide-ranging dataset, collecting participant data across an extensive range of characteristics, experiences and competencies, allowing a comprehensive statistical assessment of the different factors explaining patterns of transition. This assessment demonstrates how past experiences are influential in determining transitions, going beyond many previous studies limited by the types of exploratory variables available. The paper makes a conceptual contribution by suggesting a reemphasis on understanding youth as both a stage of ‘being’ and ‘becoming’ (France Citation2008), recognising youth as both a condition in its own right but also as a part of the continuous life course process. It underlines how the ongoing changes encountered by young people in the present are inextricably linked to their past experiences largely determined by prevailing opportunity structures (Roberts Citation2009). These past experiences in turn inform future trajectories.

The next section provides a brief background to the youth transitions tradition and youth transitions today and a basis for the hypothesis to be tested. A consideration of the TM programme in England and the insight participant data collected can provide then follows. The methodology and methods, namely the development of the typology, are then discussed before the results and analysis are presented. A discussion examining the implications of the evidence for both youth policy and employment programmes such as TM and how youth transitions are understood is presented and a conclusion then follows.

Youth transitions

A significant body of literature addressing youth transitions has developed since the 1970s, with the transition to adulthood generally accepted to have become more protracted, complex and non-linear over time (McDowell Citation2002; Furlong and Cartmel Citation2007; Thompson Citation2011). In the UK the decline of heavy industry and restructuring of the labour market; the raising of the school leaving age (twice since the 1970s); the expansion of higher education; and, more recently, increasingly restricted access to housing (Clapham et al. Citation2014) have all contributed to the transitional period between childhood and adulthood becoming extended – ‘adulthood arrested’ as some have stated (Côté Citation2000; du Bois-Reymond Citation2009). It has been suggested that youth and adulthood are now separated by a new phase, with the term ‘emerging-adulthood’ gaining prominence in the literature (Arnett Citation2000), although this particular term has been contested (Furlong and Cartmel Citation2007; Hendry and Kloep Citation2010; Côté Citation2014).

While research has indicated that the level of complexity which characterised youth transitions in the 1960s and 1970s may have been understated and the de-linearisation of modern transitions over-stated (Vickerstaff Citation2003; Goodwin and O’Connor Citation2005), there remains a consensus in youth studies that modern transitions are invariably, more fluid, complicated, risky, uncertain and prolonged. Indeed, in the UK in the mid-1970s ‘two-thirds of teenagers went straight into employment at age 16, at the end of the 1990s less than one in ten 16-year-olds looked for work as they completed compulsory schooling’ (McDowell Citation2002, 42).

Certainly, young people in the UK continue to face overwhelming challenges in finding secure employment. Youth unemployment has been a feature of the UK economy since the 1980s and unemployment has remained typically higher among young people. The unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds was 11.1% in July to September 2018 compared to 3.8% of 25- to 34-year-olds and 2.8% of 35- to 49-year-olds (Office for National Statistics Citation2018a). This is despite younger people today being better qualified than any previous generation (Hills et al. Citation2015). Young people are also more likely to experience growing conditionality and increasingly reduced entitlement in the benefits system (Watts et al. Citation2014; Crisp and Powell Citation2017a).

France (Citation2016) highlights how youth unemployment is also becoming more entrenched around the globe, emphasising new and deeper problems around underemployment and the precarious nature of work. In Australia, for example, the length of time a young person has been unemployed increased from 16 weeks on average in 2008 to 29 weeks in 2014 (France Citation2016, 117). In addition, in 2013, 13% of 15–24-year olds in the EU-28 were not in employment, education or training (O’Reilly et al. Citation2015). The implications of the findings discussed in this paper are therefore of interest not just for those targeting youth unemployment in England but in other national contexts.

Policy discourses and approaches are also shaped by blunt labour market statistics and measures, which are aspatial. Labour market statistics provide only a partial picture at best. In the UK, labour market flows are measured by the Labour Force Survey (LFS). People aged 16 years and over who do one hour or more of paid work per week are considered to be in employment, as are those who regard themselves as self-employed. Non-standard and insecure work, of which there has been a move towards, with young people heavily involved in this shift (MacDonald and Giazitzoglu Citation2019), is therefore subsumed into the employment figures. The LFS also suffers from both attrition and time-aggregation bias. The LFS deploys a five-quarter longitudinal structure and some households are more likely to drop out of the survey than others, including those in the 20–29 years age bands and those in self-employment. A high proportion of interviews with younger respondents are also undertaken by proxy: 76% of those aged 18–19 compared to 33% of all respondents during January to March 2018 (Office for National Statistics Citation2018b). Labour market transitions which occur between quarters are also not picked up. Young people who are unemployed but not claiming benefits, and therefore less visible in administrative datasets, are also an ongoing concern. In early 2018 the estimated proportion of unemployed young people (not counting students) not claiming Jobseeker's Allowance and therefore not receiving official help with job search was 54.6% (Learning and Work Institute Citation2018). Clearly official statistics lauded by Government fail to provide an accurate picture of the reality of the youth labour market.

The notion of ‘youth in transition’ has also been criticised for assuming linearity and ignoring complexity (Fergusson et al. Citation2000; Wyn and Woodman Citation2006). Studies of youth transitions have, however, been defended against this critique (MacDonald et al. Citation2001; Roberts Citation2007; France and Roberts Citation2015), and as MacDonald et al. emphasise, ‘that transitions have been extended into other life-phases, and that the destinations to which they lead are now less clear and less easily obtainable to some, does not mean they are any less interesting’ (Citation2001, paragraph 5.3). There does, nevertheless, continue to be debate around how youth transitions should be examined and understood, and developing a more holistic, temporally sensitive understanding of the transitions and interdependencies young people are negotiating has become a focus for many scholars. (Woodman and Bennett Citation2015; Wood Citation2017; Smith and Dowse Citation2019). For Wood (Citation2017) this means a framework of analysis focusing on understandings of genealogy (longer and deeper dimensions of time); wayfaring (the ordinariness of change); and threads (the entangled and integrated nature of young people's lives). Similarly, Smith and Dowse’s (Citation2019) research with young people with complex support needs, revealed times during transition to be ‘not as much about moving forwards, as about simultaneously living with complex and chaotic pasts and presents’ (Citation2019, 1).

A processual approach to understanding youth is clearly a focus for these authors, as it has been for others. Valentine (Citation2003) warned against conceptualising childhood as a fixed category but rather a process that shapes us throughout the life course. The role of the transition to work in the broader process of the transition to adulthood was also a key concern for Elias, along with the increasing distance between childhood and adulthood and the growing separation between adults and young people over the long-term (Citation2000, Citation2008). Youth has also been understood as a process of becoming (Spence Citation2005; Worth Citation2009) with France (Citation2008) recognising youth as both a stage of ‘being’ and of ‘becoming’. However, while youth studies may have begun to adopt a more processual approach, this has not been reflected in youth policy and practice. There remains a focus on achieving normative markers such as completing education, entering employment and living independently in a timely, sequential fashion, with a lack of understanding regarding the experiences of those who do not achieve this.

This paper builds on these empirically informed debates in providing further evidence on the processual nature of youth transitions today. It explores the employment transitions that were being made (or not) by a group of marginalised young people in England through the development of a typology. The typology was designed to test the hypothesis that this sub-group were experiencing the complex employment transitions the literature suggests you would expect. The findings presented reveal that the majority of young people engaged on TM were indeed struggling to gain sustainable employment and a substantial number were struggling to gain employment at all. This evidence raises questions around the difficulties in securing work for marginalised young people and how their experience of employment transitions, and indeed wider youth transitions, are understood by policymakers and those developing employment programmes. These questions are returned to within the discussion section of this paper.

The Talent Match programme

TM was a National Lottery Community FundFootnote1 strategic programme investing £108 million over five years to address high levels of unemployment amongst 18–24-year olds in England. Support focussed on those furthest from the labour market, meaning participants had typically been unemployed for 12 months or longer and faced multiple barriers to employment. It is likely a group of young people even more disadvantaged and disconnected from the labour market exists in the wider population, for example those with a very limiting disability, who did not engage with the programme due to its voluntary nature. Nevertheless, TM recognised the cohort engaged were not a single group, but may have had complex mental health and physical health barriers, face physical and practical barriers (such as transport access or availability of childcare) and might be seeking employment in areas where competition for (entry level) jobs was high (CRESR and IER Citation2014). The programme aimed to facilitate pathways for these young people into secure, meaningful, sustainable employment or enterprise. TM had a target of assisting one-fifth of those supported into sustained employment (defined as six months in employment as an employee, or 12 months self-employment).

TM was delivered through voluntary and community sector led partnerships in 21 Local Enterprise Partnership (LEPFootnote2) areas. All partnerships engaged participants in some form of pre-employment support, from an initial assessment on first engagement through to more specialised services and job search. Some partnerships also provided therapeutic support and peer mentoring, some of the more innovative approaches being used. The vast majority also offered pre-enterprise advice and support, short term work experience and work placements and structured volunteering. Almost all performed some form of job brokerage, but there was less consistency in terms of job creation activities and the development of demand-side interventions. Around half of partnerships provided employment opportunities directly through the TM programme, while fewer provided employer subsidies to those who employed TM participants with a view to more sustainable employment further down the line.

The programme included innovative features which set it apart from other existing approaches. Most notable amongst these was that TM actively involved young people in the co-production of the design and delivery of activities.Footnote3 Other features included the long-term duration and flexibility of the programme, the lack of prescription, its non-mandatory nature, and the acceptance that some innovative aspects of the programme might be tested even though they could fail.

Methodology and methods

Data from the evaluation of TM forms the evidence for this paper. A Common Data Framework (CDF) collecting robust and reliable data on all participants forms a central part of the evaluation (CRESR and IER Citation2014). The CDF was designed in the form of an online questionnaire, with data collected at the baseline stage (on entry to the programme) and then at three, six, 12, 18 and 24 months. The participant data has allowed monitoring of who participated in TM; what they did; what difference it made to them; and the impact it made on their labour market outcomes.

The CDF was designed by an independent evaluation team, commissioned by the National Lottery Community Fund to evaluate the TM programme. Ethical approval for the evaluation and associated data collection was granted via University ethics review. The CDF dataset provides a unique insight into a sub-group of young people in England, marginalised in terms of their proximity to the labour market. Young people engaged on TM were typically unemployed for 12 months or longer and faced multiple barriers to employment. For example, there was a high prevalence of poor mental health among participants and a substantial minority had experienced homelessness, alcohol and/or drug use and offending. For many of the young people in this group, their marginalisation in terms of their proximity to the labour market was therefore a symptom of their wider marginalisation.

The CDF dataset has allowed us to look at this sub-group for up to two years. Longitudinal data like this on the types of young people participating in TM is extremely rare. As discussed earlier in this paper, official statistics struggle to provide an accurate picture of the reality of the complex and dynamic youth labour market and the CDF offers a valuable opportunity to shine a light on the experiences of a group of young people less visible in the national datasets. Whilst a large proportion of participants on the programme are claiming benefits when they start the programme (77% of those engaged by the end of March 2017) and will therefore feature in these datasets, they do not offer the same longitudinal perspective as the CDF, being unable to track young people in the way the CDF can. In addition, a substantial minority of those on the programme are not claiming benefits when they join and being neither in employment nor education, are hidden from the sight of administrative datasets.

In order to examine the transitions made by TM participants, a typology of different transitional groups was created to explore the routes young people had taken in terms of securing employment (or not) and whether this had been sustained. The development of this typology provides a methodological contribution to a growing body of quantitative work in youth studies focusing less on single-status change and instead adopting a more process outcome approach (Schoon and Lyons-Amos Citation2016; Cebulla and Whetton Citation2018). While qualitative research has utilised longitudinal techniques relatively widely to examine ongoing change (for example MacDonald et al. [Citation2005] and Simmons, Russell, and Thompson [Citation2014]), traditionally quantitative approaches have taken a more static approach, in part due to the extent and nature of the data available, for example focusing on the marker of entry to employment but not what happens next.

Increased availability of longitudinal datasets and methodological advances in the social sciences, however, such as the use of sequence analysis techniques, have started to allow an examination of more holistic trajectories (see Dlouhy and Biemann, [Citation2015] for a summary of studies on careers and occupational trajectories using optimal matching analysis). Cebulla and Whetton (Citation2018), building on the work of Fry and Boulton (Citation2013), provide a recent example of the use of optimal matching and cluster analysis to examine labour market pathways of young Australians. Similarly, Schoon and Lyons-Amos (Citation2016) used sequence analysis to examine transition patterns among cohorts born in 1980–1984 and 1985–1989 featuring in the British Household Panel Study. There is still, however, more evidence available on gaining employment than on sustaining it (Adam, Atfield, and Green Citation2017). Consequently, this paper aims to contribute to this developing body of quantitative work through the development of a typology which attempts to capture the dynamism of youth transitions for a group of marginalised young people today in England.

Typology

An indicator of whether a young person had gained employment was the main outcome variable used in the development of the typology. This was derived from the following survey question:

‘Which of the following currently apply to you?’

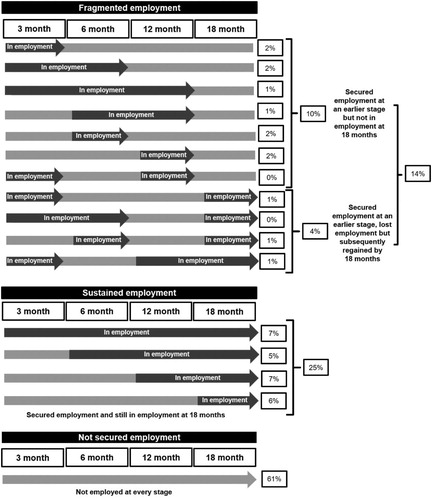

The analysis focused on responses received to the CDF questionnaires from a subset of young people who had completed a full questionnaireFootnote6 at every stage from baseline up until 18 monthsFootnote7 by the end of March 2017. By this point there were approximately 8900 young people who first engaged with the programme at least 18 months previous. Of these participants, 5275 had completed a full questionnaire at the 18-month stage, and of this sample, 1980 had also completed a full questionnaire at the baseline, three, six- and 12-month stages. It is these 1980 who were included in the subset under consideration. Responses from these young people were weighted to take into account bias in the non-response as participants who achieved an employment outcome were overrepresented in the follow-up responses. Based on their responses across the four survey stages the young people in this subset were placed into three different groupings. below provides detail on who was included in each group.

Table 1. Routes and groupings.

The first group labelled as ‘sustained employment’ included those who had indicated at some point over the follow-up stages that they were working 16 hours or more per week and this was still the case at subsequent follow-up stages completed. This includes those who first indicated they were employed at the 18-month stage. These young people have been included in this initial group as they had not indicated this status had been lost so were viewed for the purposes of analysis as sustaining employment. Of course, this status could then be lost and regained in the future as could be the case for all young people included in the sample. Indeed, this first group also includes young people indicating employment at just two survey stages, suggesting a period of just six months in continuous employment out of the 18-month period examined. This is in line with TM's definition of sustained employment; however, this could arguably also be defined as relatively short-term employment. These limitations should be borne in mind when drawing conclusions from the data. Further limitations of the data are considered at the end of this section.

The second group named ‘fragmented employment’ consisted of young people who indicated that they were working 16 hours or more per week at some point over the four stages but had subsequently lost this status. Included in this group were those who then regained employment. The final group labelled ‘not secured employment’ comprised young people who did not indicate at any follow-up stage that they were working 16 hours per week or more.

An initial descriptive assessment of the characteristics, experiences and competencies by the groups identified was undertaken followed by an assessment of the relative importance of these different factors in explaining the groupings using logistic regression modelling. A further brief descriptive assessment of the type and quality of employment secured was also carried out.

Methodological limitations

The loss of employment status beyond the period covered by the CDF was identified above as a limitation of the dataset. Indeed, as Goodwin and O’Connor (Citation2016) demonstrate, employment transitions can continue for decades. The CDF provides a longitudinal perspective; however, it is unable to pick up long-term change like this. There are clearly other limitations to the data. There will, for example, be young people excluded from the sample as their follow-up data is incomplete. Like the LFS discussed above, the CDF will also suffer from time-aggregation bias, with any transitions occurring between the different survey stages not picked up. However, those in the 20–29 years age band were more likely to drop out of the LFS survey and a high proportion of interviews with younger respondents are undertaken by proxy. The data presented, therefore, helps fill some of our gaps in knowledge of the youth labour market.

The quantitative approach utilised examining movements into employment, while valuable, also has limitations. It is important to go beyond patterns of difference in sociology and discuss the content and meanings for people (Looker and Dwyer Citation1998). This is something the quantitative approach used here cannot do. A consideration of the qualitative data available on the subset of young people discussed has not been possible within the confines of this paper but could go some way to address this and build on the findings presented below. The dataset also focuses on a particular group of young people engaged on a particular employment programme. It cannot tell us about the experiences of marginalised young people across England more generally. Nevertheless, the insight from this unique dataset is valuable in allowing us to explore the experiences of a group of young people often hidden from sight from official statistics; and whose characteristics and labour market position mirror those of unemployed young people in other European and north American contexts.

Results and analysis

This section explores the hypothesis that young people participating in the TM programme in England were experiencing complex employment transitions and were finding these difficult to negotiate.

Descriptive assessment of routes and groups

Three-fifths of participants did not indicate that they were working 16 hours or more per week at any follow up stage (). These young people have been placed in the ‘not secured employment’ group. In contrast seven per cent of participants indicated they were employed at every follow-up stage. A further 18% had indicated at some point over the follow-up stages that they were working 16 hours or more per week and this was still the case at subsequent follow-up stages completed (five per cent at the six, 12 and 18 month stages, seven per cent at the 12 and 18 month stages and six per cent at the 18 month stage). These young people added together make up one-quarter of participants and have been placed in the ‘sustained employment’ group. A further 14% of young people indicated that they were working 16 hours or more per week at some point over the four stages but had subsequently lost this status, including those who also then regained employment. These have been placed in the ‘fragmented employment’ grouping ().

Table 2. Groups.

An initial descriptive assessment of the characteristics, experiences and competencies by group is shown in below. The variables explored are those identified in a statistical modelling exercise on CDF responses as part of the TM evaluation, as statistically associated with being in work.

Table 3. Characteristics, experiences and competencies at baseline by group.

A z-test for proportions was used to test for differences between each of the groups in the percentage identifying the characteristics, experiences and competencies explored. Statistical testing is important because it is only in instances where the difference is statistically significant that there is sufficient evidence to indicate that the observed difference has not occurred due to chance. A number of statistically significant differences were identified.

For every characteristic, experience or competency in excluding having children, having appropriate clothing to wear to an interview and engagement with drugs/alcohol support before starting on the programme, there was a significant difference in the proportion not securing employment when compared to the other two groups. The proportion of participants who had appropriate clothing to wear was significantly higher among those sustaining employment when compared to those not securing employment at all.

Modelling

The relative importance of the different factors listed above in explaining the groupings was also assessed. Logistic regressionFootnote8 modelling was used to test which of these factors were statistically associated to the different groups.

There were seven variables statistically associated with being in the sustained employment group. Young people with a limiting disability were statistically less likely to be part of this group as were those with children and those who had engaged with mental health services before engaging with the programme. In contrast, young people who had achieved at least 5 GCSEs, felt they had confidence before starting on the programme, appropriate clothing to wear to an interview and those who had previously gained employment were statistically more likely to have sustained employment ().

Table 4. Results of logistic regression – sustained employment.

Five variables were statistically associated with the fragmented employment group. Young people who indicated they felt they had good specific skills for the job they were looking for when starting on the programme, those who felt they were good at managing their feelings and those who had previously gained employment were statistically more likely to be in this group. In contrast, young people with a limiting disability and those who had engaged with mental health services before starting on the programme were statistically less likely to be in this group ().

Table 5. Results of logistic regression – fragmented employment.

Seven variables were statistically associated with being in the group who had not gained employment. Young people with a limiting disability were 2.5 times more likely to be in this group while those who had been involved with mental health services were 2 times more likely. Young people with children were also statistically more likely to be in this group. In contrast participants who had achieved at least 5 GCSEs, felt they had confidence before starting on the programme and those who had previously gained employment were statistically less likely to be in this group ().

Table 6. Results of logistic regression – not secured employment.

Descriptive assessment of type and quality of employment secured

below provides a descriptive assessment of the type and quality of employment young people who indicated they were working 16 hours or more per week via at least one follow-up stage had gained. A z-test for proportions was again used to test for differences between each of the groups in the percentage identifying the type and quality of employment explored.

Table 7. Employment contract type, satisfaction and underemployment; based on the latest response provided.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the proportion of young people with a permanent contract was noticeably higher for those sustaining employment when compared to those placed in the fragmented employment group (74% compared to 53%). This difference was statistically significant. The differences in the proportions in each group with a temporary contract with no fixed end date and the proportions in self-employment were also identified as statistically significant (both proportions higher among the fragmented employment group). One-fifth of young people experiencing a fragmented transition into employment indicated they were on a zero hours contract compared to one in ten of those sustaining employment (again a statistically significant difference). These figures seem low in the context of recent research by Purcell et al. (Citation2017) which found nearly all the opportunities faced by young jobseekers with low or no educational or vocational qualifications in their study to be confined to low-paid, zero-hours work. Nationally, however, just 2.8% of those in employment report that they are on a zero hours contract (Office for National Statistics Citation2017). These figures are based on estimates from the LFS, the limitations of which are discussed elsewhere in this paper, but suggest a greater role for these types of contracts among the group of young people under discussion than among the wider population. The majority of young people in both groups on a zero-hour contract stated they would prefer a contract with permanent hours. The majority of young people in both groups also indicated they were satisfied with their present job overall, although the proportion among those sustaining employment was higher and this difference was identified as statistically significant.

The CDF asks those in work if in the past four weeks they had: looked for an additional job; looked for a new job with longer hours; or wanted to work longer hours in their current job.Footnote9 Responses to these questions were combined to assess whether young people could be considered underemployed. If a respondent indicated they had done any of the three things above they have been identified as underemployed. Underemployment was higher for those experiencing a fragmented transition, however over one-third of those sustaining employment also indicated they were underemployed and the difference in the proportions was statistically significant.

In summary, the findings from the empirical evidence presented appear to support the hypothesis outlined at the start of the paper. Young marginalised people on the TM programme did appear to be experiencing complex employment transitions and were finding these difficult to negotiate. Only one-quarter of young people who had completed a full questionnaire at every stage from baseline up until 18 months had sustained employment. Three-fifths did not indicate at any point that they were working 16 hours a week or more. A further 14% of the subset indicated that they were working 16 hours or more per week at some point over the four stages but subsequently lost this status; although some did then go on to regain employment.

Discussion and conclusion

The evidence presented suggests that the majority of young people engaged on the TM programme struggled to gain sustainable employment and a substantial number struggled to gain employment at all. Of those who did gain employment, a sizeable minority did not have permanent employment contracts. Almost two-fifths of the young people in the subset examined had gained employment, however, this was only after joining the programme. Typically, these young people will have been unemployed for 12 months or longer prior to joining TM and a number likely to be aged well into their twenties. A sizeable minority also then went on to lose employment at some point. These findings support the notion that employment transitions for these young people are complex and protracted. This is important as there are likely to be negative consequences, such as long-term negative scarring effects on wellbeing, health status and job satisfaction (Bell and Blanchflower Citation2011). There is also growing evidence that early transitions and ‘pathways’ themselves are predictive of longer-term outcomes and future labour market experiences (Anders and Dorsett Citation2017; Cebulla and Whetton Citation2018).

The findings also highlight the churn between statuses experienced by this group. This is most visible among those in the fragmented employment group shown in . However, several of those who had not gained employment are likely to go on to secure work and some in employment, particularly those on temporary contracts, are likely to become unemployed. In addition, there may have been people who moved between statuses in the periods between survey stages. That the analysis presented here has focused on those working 16 hours or more per week, in contrast to the UK national employment figures, which include those working just one hour per week, is also significant. Even when discounting those working under 16 hours, who could be engaging in informal or casual employment, the young people who secured employment are shown to have faced impermanence and precarity in their jobs. Clearly securing work does not mean an end to the transition into employment.

Yet, the most striking result presented was that three-fifths of the young people in the subset examined had not secured employment at all. This has clear resonance with the work of Smith and Dowse (Citation2019) who concluded that ‘transition is not a sequential, phased or ahistorical process with a clear starting point or defined destination’. Securing employment was arguably not a realistic target for many within the time frame of their participation on TM, and of those who did reach this ‘destination’ this did not represent a finalised state marking the end of their transition into employment. Perhaps as Karhula et al. (Citation2019) argue, there is a need for a focus on ‘destination as a process' in understanding how processes of attainment unfold over time.

Moreover, it is important to avoid treating these three-fifths as a monolithic grouping, focusing simply on their failure to meet this destination. This denies the wider experiences of this group and does not correspond with a processual understanding of youth. The ways in which members of this grouping may (or may not) have progressed to states that bring them closer to a successful labour market outcome is important. Indeed, some further exploratory analysis finds that at some point during the 18-month period since starting on TM: 13% were working less than 16 hours per week; 62% were volunteering; and 17% had started a work placement. This suggests these young people had potentially moved closer to the labour market or at least broadened their life experiences.

Critically, the findings presented reveal the importance of past experiences on shaping the present, reiterating the need to see transition as an historical process. The young people who had not secured employment were more likely to have a limiting disability, have been involved in mental health services, have children, have not achieved 5 GCSEs or more, have low confidence before starting on the programme and not previously gained employment. These young peoples’ inability to secure employment appears inextricably linked to what happened in their past. Yet it is impossible to understand young people's experiences outside of the landscape that frames their lives. Young people today face new opportunities and risks, but social structures continue to shape life chances (Furlong and Cartmel Citation2007). As Roberts (Citation2009) has demonstrated, prevailing opportunity structures, formed by the inter-relationships between family backgrounds, education and jobs, remain critical in determining young peoples’ transitions into employment. Opportunity structures will have shaped the past experiences of the young people under discussion and continue to govern their transitional experiences.

Indeed, two of the most striking results presented concern young people who reported a limiting disability and those who had engaged with mental health services. These two groups were significantly less likely to secure employment (2.5 times and 2 times less likely respectively). These results resonate with recent research highlighting the challenges young people with mental health problems and disabilities are facing in the current context and make a necessary contribution to a still limited evidence base. There is a lack of published up-to-date data concerning young people and mental health (the prevalence of selected diagnosed mental health conditions in the UK youth population is not measured regularly), however, clear evidence exists pointing to a growing incidence of mental health/well-being problems among young people not in education, employment or training (see Powell et al. [Citation2015] for a summary of the relevant literature). Similarly, most research on disability and barriers to employment focuses on adults and not young people. An exception is the work of Lindsay (Citation2011) which found that young adults with disabilities encounter several barriers and discrimination when looking for work.

The findings presented also have implications for employment programmes and youth policy generally. A departure from traditional normative notions of time towards a more dynamic understanding of youth transitions has become important to youth scholars. However, youth policy and practice lag behind in adopting this approach. Qualitative research with TM participants found that finding work was not an immediate expectation for some, but something to be aspired to in the future. For example, some participants wished to upskill before commencing job search and a number of those experiencing mental health conditions felt that dealing with these issues was their initial priority. The impact of these longer-term aspirations is perhaps reflected in the quantitative evidence presented above. Nonetheless, TM was an employment programme and securing employment for participants, or moving them closer to the labour market, was its fundamental objective. TM had targets for numbers engaged and those achieving sustained employment. This suggests limits to the extent to which these longer-term aspirations could be countenanced.

TM did, however, hold a greater appreciation of these aspirations compared to mainstream provision and the logic of welfare conditionality. Powell et al. (Citation2015) found that welfare conditionality and the JCP benefit sanctions regime were key contributory factors to mental health issues among TM participants. Mainstream provision today has little appreciation for the role of past experiences, their impact and the time required to resolve long-standing issues, instead demanding a constant flow of job applications in order to satisfy advisors (see Flint (Citation2019) for an examination of the growing use of welfare conditionality in the UK). In contrast, TM was presented as an innovative programme, offering a more holistic approach to tackling youth unemployment; nonetheless, a substantial proportion of young people participating still failed to gain employment. Of course, it is worth re-emphasising that TM worked with those far from the labour market often facing multiple barriers to employment. In recognition of this TM aimed to move all participants closer to the labour market but just one-fifth into sustained employment, albeit for a period of just six months minimum.

Nevertheless, the evidence presented still begs the question if TM cannot help a substantial number of young people to find work who or what else can? As discussed earlier there was less consistency across TM partnerships in terms of job creation activities and the development of demand-side interventions, with the primary focus on pre-employment support. This model relies on a labour market that is working reasonably well to take up the stock of work-ready young people. In the absence of this, it is questionable how much programmes like TM can achieve. As emphasised above, an understanding of the landscape that frames young people's lives is critical. Indeed, a systematic review of 113 impact evaluations of youth employment programmes worldwide (Kluve et al. Citation2019) found that while, on average, programmes reported statistically significant positive effects, the unconditional average effect size across programmes was small both for employment-related and earnings-related outcomes. Programmes integrating multiple interventions and services were more likely to have a positive impact, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, suggesting the labour market constraints in these countries might be more easily navigated than in high-income countries.

The empirical evidence presented in this paper provides further weight to a growing body of work employing a more temporally sensitive approach to understanding youth transitions. Past experiences, influenced by prevailing opportunity structures, are shown to be influential. The findings underline how it is essential that any understanding of youth today needs to recognise the simultaneous presence of aspects of childhood, youth and adulthood in characterising transitional experiences. This conclusion therefore suggests a reemphasis on understanding youth as both a stage of ‘being’ and ‘becoming’ (France Citation2008), recognising youth as both a condition in its own right but also as a part of the life course process. In terms of policy and practice, a greater appreciation of young people's complex pasts, and their ongoing impact is required. This might mean more relational, long-term approaches to solutions. Indeed, the focus in this paper has been on individual characteristics but this needs to be accompanied by an understanding of the social worlds of young people in terms of the wider factors and processes that coalesce to produce labour market marginalisation.

Mainstream approaches to tackling youth unemployment in the UK have generally deployed coercive, individualised methods and even the objectives of the TM programme were largely couched in terms of individualised solutions. There has been little focus on the role of others, for example families and institutions, in shaping experiences and outcomes. A more biographical, relational understanding regarding the ongoing changes young people are encountering (see also Crisp and Powell Citation2017b) would help understand how policy and practice can best tackle youth unemployment today. Elias (Citation1978) emphasised the ‘interdependence’ of humans on each other and for Burkitt (Citation2016) this interdependence means a more relational understanding of agency. A more in-depth qualitative assessment of where the marginalised young people participating in TM are situated both socially and geographically would therefore add to the labour market evidence presented here.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the National Lottery Community Fund for funding the Talent Match evaluation. In particular thanks are due to James Godsal and Matthew Poole. The views expressed here are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Lottery Community Fund. Thanks are also due to the 21 Talent Match partnerships collecting data on participants and to the members of the evaluation team, in particular: Chris Damm, Sarah Pearson, Ryan Powell, Peter Wells and Ian Wilson at the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at Sheffield Hallam University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The organisation changed its name from the Big Lottery Fund in early 2019.

2 LEPs are voluntary partnerships between local authorities and businesses in England set up by government to help determine local economic priorities and lead economic growth and job creation within a local area.

3 Activities young people were involved in included: evaluation, research and gathering feedback; engaging other young people/outreach; marketing; membership of the Core partnership group or committee; media and dissemination; delivering services; management of the TM Partnership and/or service delivery; and the commissioning of services.

4 Not working and not looking for work; Not working and looking for work; Working less than 16 hours per week; Working 16 hours or more per week (excluding apprenticeship); Self-employed; Volunteering; Work Placement; Apprenticeship; Formal education e.g. college; In training; Long-term sick or disabled; In custody; Travelling; Looking after children; Caring; Other.

5 The evaluation does however take into consideration young people working less than 16 hours per week with caring responsibilities/childcare commitments/disability/ ill health or education commitments which limit the number of hours they can work.

6 If a young person is unable to complete a questionnaire themselves then a short section at the start of the questionnaire is completed instead by the delivery organisation.

7 Responses from the 24-month survey were not been included at this stage due to a low base at this point in the programme and evaluation.

8 Forward LR method was utilised – this method adds explanatory variables to the model which meet the Likelihood Ratio.

9 Based on questions designed by the Office for National Statistics.

References

- Adam, D., G. Atfield, and A. E. Green. 2017. “What Works? Policies for Employability in Cities.” Urban Studies 54 (5): 1162–1177. doi: 10.1177/0042098015625021

- Anders, J., and R. Dorsett. 2017. “What Young English People do Once They Reach School-Leaving Age: A Cross-Cohort Comparison for the Last 30 Years.” Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 8 (1): 75–103. doi: 10.14301/llcs.v8i1.399

- Arnett, J. J. 2000. “Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development From the Late Teens Through the Twenties.” American Psychologist 55 (5): 469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

- Bell, D. N., and D. G. Blanchflower. 2011. “Young People and the Great Recession.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 27 (2): 241–267. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grr011

- Burkitt, I. 2016. “Relational Agency: Relational Sociology, Agency and Interaction.” European Journal of Social Theory 19 (3): 322–339. doi: 10.1177/1368431015591426

- Calvert, E. 2010. Young People’s Housing Transitions in Context. ESRC Centre for Population Change Working Paper.

- Cebulla, A., and S. Whetton. 2018. “All Roads Leading to Rome? The Medium Term Outcomes of Australian Youth’s Transition Pathways from Education.” Journal of Youth Studies 21 (3): 304–323. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2017.1373754

- Clapham, D., P. Mackie, S. Orford, I. Thomas, and K. Buckley. 2014. “The Housing Pathways of Young People in the UK.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 46 (8): 2016–2031. doi: 10.1068/a46273

- Côté, J. E. 2000. Arrested Adulthood: The Changing Nature of Maturity and Identity. New York: NYU Press.

- Côté, J. E. 2014. “The Dangerous Myth of Emerging Adulthood: An Evidence-Based Critique of a Flawed Developmental Theory.” Applied Developmental Science 18 (4): 177–188. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2014.954451

- CRESR, and IER. 2014. Evaluation of Talent Match Programme: Annual Report. Sheffield: CRESR.

- Crisp, R., and R. Powell. 2017a. “Young People and UK Labour Market Policy: A Critique of ‘Employability’ as a Tool for Understanding Youth Unemployment.” Urban Studies 54 (8): 1784–1807. doi: 10.1177/0042098016637567

- Crisp, R., and R. Powell. 2017b. “Youth Unemployment, Interdependence and Power: Tensions and Resistance within an Alternative, “Co-Produced” Employment Programme.” In Decentring Urban Governance: Narratives, Resistance and Contestation, edited by M. Bevir, P. Matthews, and K. McKee, 38–64. London: Routledge.

- Dlouhy, K., and T. Biemann. 2015. “Optimal Matching Analysis in Career Research: A Review and Some Best-Practice Recommendations.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 90: 163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.04.005

- du Bois-Reymond, M. 2009. “Models of Navigation and Life Management.” In Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood: New Perspectives and Agendas, edited by A. Furlong, 31–38. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Elias, N. 1978. What is Sociology? Translated by S. Mennell, and G. Morrissey. London: Hutchinson.

- Elias, N. 2000. The Civilizing Process. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Elias, N. 2008 [1980]. “The Civilising of Parents.” In Essays II: On Civilising Processes, State Formation and National Identity, edited by R. Kilminster, and S. Mennell, 14–40. Dublin: UCD Press.

- Fergusson, R., D. Pye, G. Esland, E. McLaughlin, and J. Muncie. 2000. “Normalized Dislocation and New Subjectivities in Post-16 Markets for Education and Work.” Critical Social Policy 20 (3): 283–305. doi: 10.1177/026101830002000302

- Flint, J. 2019. “Encounters with the Centaur State: Advanced Urban Marginality and the Practices and Ethics of Welfare Sanctions Regimes.” Urban Studies 56 (1): 249–265. doi: 10.1177/0042098017750070

- France, R. 2008. “From Being to Becoming: The Importance of Tackling Youth Poverty in Transitions To Adulthood.” Social Policy and Society 7 (4): 495–505. doi: 10.1017/S1474746408004454

- France, A. 2016. Understanding Youth in the Global Economic Crisis. Bristol: Policy Press.

- France, A., and S. Roberts. 2015. “The Problem of Social Generations: A Critique of the new Emerging Orthodoxy in Youth Studies.” Journal of Youth Studies 18 (2): 215–230. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2014.944122

- Fry, J., and C. Boulton. 2013. Prevalence of Transition Pathways in Australia. Canberra: Productivity Commission Staff Working Paper.

- Furlong, A., and F. Cartmel. 2007. Young People and Social Change: New Perspectives. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Goodwin, J., and H. O’Connor. 2005. “Exploring Complex Transitions: Looking Back at the ‘Golden Age’ of From School to Work.” Sociology 39 (2): 201–220. doi: 10.1177/0038038505050535

- Goodwin, J., and H. O’Connor. 2016. “From Young Workers to Older Workers: Eliasian Perspectives on the Transitions to Work and Adulthood.” Belvedere Meridionale 28 (1): 5–21. doi: 10.14232/belv.2016.1.1

- Hendry, L. B., and M. Kloep. 2010. “How Universal is Emerging Adulthood? An Empirical Example.” Journal of Youth Studies 13 (2): 169–179. doi: 10.1080/13676260903295067

- Hills, J., J. Cunliffe, P. Obolenskaya, and E. Karagiannaki. 2015. Falling Behind, Getting Ahead: The Changing Structure of Inequality in the UK, 2007–2013. Social Policy in Cold Climate Research Paper No. 5.

- Karhula, A., J. Erola, M. Raab, and A. Fasang. 2019. “Destination as a Process: Sibling Similarity in Early Socioeconomic Trajectories.” Advances in Life Course Research 40: 85–98. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2019.04.015

- Kluve, J., S. Puerto, D. Robalino, J. M. Romero, F. Rother, J. Stöterau, F. Weidenkaff, and M. Witte. 2019. “Do Youth Employment Programs Improve Labor Market Outcomes? A Quantitative Review.” World Development 114: 237–253. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.10.004

- Learning and Work Institute. 2018. Comment on February 2018 Unemployment Statistics. https://www2.learningandwork.org.uk/statistics/labour/february-2018.

- Lindsay, S. 2011. “Discrimination and Other Barriers to Employment for Teens and Young Adults with Disabilities.” Disability and Rehabilitation 33 (15–16): 1340–1350. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.531372

- Looker, D. E., and P. Dwyer. 1998. “Rethinking Research on the Education Transitions of Youth in the 1990s.” Research in Post-Compulsory Education 3 (1): 5–25. doi: 10.1080/13596749800200024

- MacDonald, R., and A. Giazitzoglu. 2019. “Youth, Enterprise and Precarity: Or, What is, and What is Wrong with, the ‘Gig Economy’?” Journal of Sociology 00: 1–17. Accessed 25 May 2019.

- MacDonald, R., P. Mason, T. Shildrick, C. Webster, L. Johnston, and L. Ridley. 2001. “Snakes and Ladders: in Defence of Studies of Youth Transition.” Sociological Research Online 5 (4): 1–13. http://www.socresonline.org.uk/5/4/macdonald.html. doi: 10.5153/sro.552

- MacDonald, R., T. Shildrick, C. Webster, and D. Simpson. 2005. “Growing Up in Poor Neighbourhoods: The Significance of Class and Place in the Extended Transitions of 'Socially Excluded' Young Adults.” Sociology 39 (5): 873–891. doi: 10.1177/0038038505058370

- McDowell, L. 2002. “Transitions to Work: Masculine Identities, Youth Inequality and Labour Market Change.” Gender, Place and Culture 9 (1): 39–59. doi: 10.1080/09663690120115038

- Office for National Statistics. 2017. Contracts that do not Guarantee a Minimum Number of Hours: April 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/contractsthatdonotguaranteeaminimumnumberofhours/april2018#how-many-no-guaranteed-hours-contracts-nghcs-are-there.

- Office for National Statistics. 2018a. A05 SA: Employment, Unemployment and Economic Inactivity by Age Group (Seasonally Adjusted) Table A05 13 November 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/datasets/employmentunemploymentandeconomicinactivitybyagegroupseasonallyadjusteda05sa/current.

- Office for National Statistics. 2018b. Labour Force Survey Performance And Quality Monitoring Report: October to December 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/methodologies/labourforcesurveyperformanceandqualitymonitoringreports/labourforcesurveyperformanceandqualitymonitoringreportjanuarytomarch2018.

- O’Reilly, J., W. Eichhorst, A. Gábos, K. Hadjivassiliou, D. Lain, J. Leschke, S. Mcguinness, L. M. Kureková, T. Nazio, and R. Ortlieb. 2015. “Five Characteristics of Youth Unemployment in Europe: Flexibility, Education, Migration, Family Legacies, and EU Policy.” Sage Open 5 (1). doi:10.1177/2158244015574962.

- Powell, R., N. Bashir, R. Crisp, and S. Parr. 2015. Talent Match Case Study Theme Report: Mental Health and Well-Being. Sheffield: CRESR.

- Purcell, K., P. Elias, A. Green, P. MIzen, M. Simms, N. Whiteside, D. Wilson, et al. 2017. Present Tense, Future Imperfect? Young People’s Pathways Into Work. Warwick: Institute for Employment Research, University of Warwick.

- Roberts, K. 2007. “Youth Transitions and Generations: A Response to Wyn and Woodman.” Journal of Youth Studies 10 (2): 263–269. doi: 10.1080/13676260701204360

- Roberts, K. 2009. “Opportunity Structures Then and Now.” Journal of Education and Work 22 (5): 355–368. doi: 10.1080/13639080903453987

- Schoon, I., and M. Lyons-Amos. 2016. “Diverse Pathways in Becoming an Adult: The Role of Structure, Agency and Context.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 46 (A): 11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2016.02.008

- Simmons, R., L. Russell, and R. Thompson. 2014. “Young People and Labour Market Marginality: Findings from a Longitudinal Ethnographic Study.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (5): 577–591. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2013.830706

- Smith, L., and L. Dowse. 2019. “Times During Transition for Young People with Complex Support Needs: Entangled Critical Moments, Static Liminal Periods and Contingent Meaning Making Times.” Journal of Youth Studies 00: 1–18. Accessed 25 May 2019.

- Spence, J. 2005. “Concepts of Youth.” In Working with Young People, edited by R. Harrison, and C. Wise, 46–56. London: Sage.

- Thompson, R. 2011. “Individualisation and Social Exclusion: The Case of Young People not in Education, Employment or Training.” Oxford Review of Education 37 (6): 785–802. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2011.636507

- Valentine, G. 2003. “Boundary Crossings: Transitions from Childhood to Adulthood.” Children's Geographies 1 (1): 37–52. doi: 10.1080/14733280302186

- Vickerstaff, S. A. 2003. “Apprenticeship in the ‘Golden Age’: Were Youth Transitions Really Smooth and Unproblematic Back Then?” Work, Employment and Society 17 (2): 269–287. doi: 10.1177/0950017003017002003

- Watts, B., S. Fitzpatrick, G. Bramley, and D. Watkins. 2014. Welfare Sanctions and Conditionality in the UK. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Wood, B. E. 2017. “Youth Studies, Citizenship and Transitions: Towards a New Research Agenda.” Journal of Youth Studies 20 (9): 1176–1190. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2017.1316363

- Woodman, D., and A. Bennett. 2015. “Cultures, Transitions, and Generations: The Case for a new Youth Studies.” In Youth Cultures, Transitions, and Generations, edited by D. Woodman, and A. Bennet, 1–15. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Worth, N. 2009. “Understanding Youth Transition as ‘Becoming’: Identity, Time and Futurity.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 40 (6): 1050–1060.

- Wyn, J., and D. Woodman. 2006. “Generation, Youth and Social Change in Australia.” Journal of Youth Studies 9 (5): 495–514. doi: 10.1080/13676260600805713