ABSTRACT

The urgency to reduce knife carrying has been recognised by police services within Scotland and has been addressed by initiatives such as the sharing of knife seizure images on media outlets. This study sought to explore young peoples’ views on the use of knife seizure images as a deterrent to carrying knives by using comparative individual interviews (N = 20). Three themes were discovered: (1) negative reactions towards images of seized knives, (2) images of knives may encourage rather than deter knife carrying, and (3) reinforcement of existing beliefs, stereotypes and stigma. These findings highlight the limitations of using knife seizure images as a deterrent and the importance of involving young people in developing preventative and non-discriminatory approaches to tackling knife crime.

Introduction

Tackling knife crime has remained a key issue for UK policy makers, with growing research building a comprehensive understanding on how best to achieve this (Harding Citation2020; Silvestri et al. Citation2009; Skarlatidou et al. Citation2022). The term ‘knife crime’ encompasses a range of offences, including possession of a knife, knife-related violence, and the presence of a knife in robberies, sexual violence, and criminal damage (Grimshaw and Ford Citation2018). The pioneering work of the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit (SVRU), which was set up in 2005 at a time when Glasgow was known as Europe’s murder capital, has been credited for much of the progress in preventing knife crime in Scotland. Despite there having been a 29% decrease in police-recorded knife crimes in Scotland reported between 2010–2011 and 2019–2020 (Office for National Statistics (ONS) Citation2019, Citation2020), recent statistics indicate a 6% rise in crimes of handling an offensive weapon from 2018–2019 to 2019–2020 (ONS Citation2020). In England and Wales, an 80% increase was recorded in the 5 years preceding 2019 (Shaw Citation2019) with approximately a third of recorded offences having occurred in London, with the majority involving young people (Grierson Citation2020).

The ongoing pursuit to reduce knife crime has encouraged policy makers and researchers to scrutinise the existing deterrents implemented across the UK. Among them, sharing knife seizure images, where pictures of knives recovered by the police are posted across various media outlets and used in campaigns, is one method that has received attention. Knife seizure images are also used to show the success of police efforts to seize weapons off the streets and warn the public about the dangers of such weapons (Russell Citation2021). These images have largely been targeted towards young people (England and Jackson Citation2013; Wells Citation2008). While concerns have been raised that using knife images may potentially increase fear and perpetuate stereotypes (No Knives Better Lives Citation2019), to date, very little is known about the impact of these widely accessible images. In consideration of these speculations about the intent and outcomes of using knife seizure images, there is a need for more substantive evidence about how young people respond to the use of these images (Silvestri et al. Citation2009). Moreover, increased public concern in relation to knife crime, potentially linked to high profile cases within the media (Harding Citation2020), has called for a renewed focus to address the lack of empirical evidence on the effectiveness of deterrents (Grimshaw and Ford Citation2018; Vulliamy et al. Citation2018) and to ascertain young people’s views on the use of knife seizure images (No Knives Better Lives Citation2019). There is also a need to understand if the perceived effects and consequences of using knife-seizure images differ among young people who live in areas of high knife crime compared to those living in areas of low knife crime rates. This is pertinent given that feeling vulnerable to crime, as might be expected among young people living in areas of high knife crime, has been found to increase fear of crime (Erčulj Citation2021).

Young people and knife crime

Young people are disproportionately at risk of being exposed to higher levels of crime (Densley and Stevens Citation2014; Harding Citation2020; Wood Citation2010); this includes witnessing violence, being a victim of violence and being threatened with a weapon (Surko et al. Citation2005). In Scotland, young adults and people living in the most deprived areas are most at-risk of assault-related sharp-force injuries (Goodall et al. Citation2019; Leyland and Dundas Citation2010; Scottish Truama Audit Group Citation2016). Fear of victimisation has been identified as the primary reason for knife carrying (Foster Citation2013), which stems from the belief that knives offer a means of protection (Bannister et al. Citation2010; Goodall et al. Citation2019). A recent systematic review examining the risk factors for knife crime among young people aged 10–24 years provided further insight into this, although only 1 of the 16 studies reviewed focused specifically on the Scottish context (Haylock et al. Citation2020). Among the risk factors were social problems commonly encountered by young people living in deprived areas such as educational and occupational disadvantages, the stigma of poverty, adverse childhood experiences, and economic deprivation (Coid et al. Citation2021; Densley and Stevens Citation2014; Grimshaw and Ford Citation2018). This research draws attention to how violence involving knife crime is a complex product of people’s responses to their social situations and environment. The challenges and specific risk factors linked with knife carrying establish a need to understand the potential role of the environment in fostering different perceptions about knife carrying and crime, and whether this impacts on the effectiveness of knife-deterring initiatives (Harding Citation2020), including the use of knife seizure images.

Crime in the media

The media has always had a profound effect on how the public perceives and understands societal issues, which may create a distorted image of the reality of knife carrying and crime (Humphreys et al. Citation2019). An explanation for this can be drawn by Cultivation Theory (Gerbner et al. Citation1994), which proposes that an individual’s perception of the world’s social realities is a reflection of the frequency and type of media they consume. Cultivation research has shown an association between media consumption and various attitudes such as perceived levels of social violence, perceived crime risk and support for gun control (Chermak Citation1994; Rhineberger-Dunn, Briggs, and Rader Citation2015). Additionally, the overrepresentation of violent crimes in news media may lead to an overestimation of crime, thus misleading the public about safety concerns and intensifying fear of violence and/or victimisation (Holligan, McLean, and Deuchar Citation2017; Humphreys et al. Citation2019; Intravia et al. Citation2017; Smolej and Kivivuori Citation2006; Thompson et al. Citation2019). This relates to wider, societal consequences of how media narratives of crime may exacerbate criminal stereotypes of people or places. For example, a survey from the USA has shown that attention to crime news was positively associated with culpability judgements about people of Black or unidentified but not White racial background, and that exposure to the overrepresentation of Black people as criminals was positively related to the perception that they are violent (Dixon Citation2008). Speaking of images, Gutsche and Salkin (Citation2011) found that news photographs provided valuable information on how an area’s characteristics were defined, but these were often portrayed through inaccurate and negative narratives and stereotypes. These examples of the influence of news media and images draw attention to how images of seized knives may be interpreted, and their potential to stigmatise young people through reinforcing negative perceptions about areas, race and communities where knives are reportedly seized (Bhatia, Poynting, and Tufail Citation2018; Rogan Citation2021). Socio-economic disadvantage is apparent across specific cultural groups and media representations of particular groups of minoritised young people have been found to fuel negative racial stereotypes (Idriss Citation2021). Indeed, how racial discourses are produced and reproduced in pervasive, subtle and discursive ways through popular culture and mass media has long been viewed as a means of maintaining white hegemony (Gilroy et al. Citation2019; Hall Citation1980, Citation1996). This calls for an urgent need to investigate the impact of showing images of seized knives alongside how media narratives influence their interpretation by youth (Chadee and Surette Citation2019).

Knife-carrying deterrents

Young people often feature as the main focus of knife-related research and deterrents (Batchelor et al. Citation2010; Fraser Citation2013). The empirical research on the reasons and subjective meanings of knife carrying among young people tends to be unsystematic and lacks contextualisation within Scotland (Palasinski and Riggs Citation2012), which has hindered both local and government efforts to introduce more effective counter measures for knife carrying (Ang et al. Citation2012). The SVRU has been recognised as a global innovator in violence reduction by adopting an upstream public health approach and focusing on preventative action at the root cause (Rainey et al. Citation2015; Scottish Government Citation2021). By utilising a multi-levelled social ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner Citation1977), the objective is to examine the interplay of individual, interpersonal, community and societal factors on violence reduction (Dahlberg and Mercy Citation2009). Research evaluating programmes guided by this framework, including peer-led parenting, community initiatives and school-based education initiatives, has reported positive results in relation to deterring weapon-carrying (Day et al. Citation2012; Gavine, Williams, and Donnelly Citation2014; Local Government Association Citation2018; Measor and Squires Citation2000; Russell Citation2021; Ward Citation2019; Williams et al. Citation2014) yet there is a need for further longitidunal work. While these findings provide growing support for the importance of intervention programmes to help mitigate the environmental and societal factors that may contribute towards knife crime among youth, there is little empirical research evaluating police-led crime deterrents implemented across the UK (Rosbrook-Thompson Citation2019). Further, existing research on fear-based deterrent methods, such as arrest and punishment responses, scare tactics, and confrontational techniques, have not only been found to be ineffective, but may even have adverse effects such as fear of victimisation (Youth Justice Board Citation2010). One of the most widely reported and researched programmes, ‘Scared Straight’, at New Jersey’s Rahway State Prison (Finckenauer Citation1980) involved prison inmates (lifers) scaring delinquents or suspected delinquents ‘straight’. The programme involved organised visits to prisons by delinquents or at-risk youths with the aim of deterring through direct observations of prison life and interactions with inmates. Deterrence is the theory behind the programme; that delinquent youths would refrain from criminal activities because they would not want to follow the same path as inmates and end up in an adult prison (Petrosino, Petrosino, and Buehler Citation2005; Pestrosino et al. Citation2013). Such programmes encompass a range of traditional deterrent techniques, including fear and intimidation, but appear to be potentially harmful as the exposure to crime may result in reoffending or increased probability of committing criminal offences in the future (Pestrosino et al. Citation2013; Russell Citation2021). Lipsey’s (Citation2009) meta-analysis of the characteristics associated with effective interventions for young offenders provides additional evidence against deterrence or discipline techniques, reporting that they are associated with a 2–8% increase in rates of recidivism.

Although further evaluation of the context and delivery of such programmes is needed, as well as consideration of which groups of young people may benefit from such interventions (Wortley and Hagell Citation2021), these findings highlight the potential advantages of engaging with young people about the consequences of knife crime. Yet, no known research has explored the impact of using knife seizure images as a deterrent method, where images of knives recovered by the police are shared across various media outlets including social media, television and within school campaigns. Given that fear, protection, victimisation, peer pressure, gang warfare and fashion are considered to be some of the prime motivations for knife carrying (Kelly et al. Citation2018; Lynes et al, Citation2020; Squires Citation2009) the important role of wider socio-cultural factors and the influence of social media are important considerations (Nijjar Citation2021). Indeed, theories of media effects have long established a link between media consumption, fear and exposure to crime (Intravia et al. Citation2017). Further research involving young people is required to ascertain whether sharing such images through diverse media outlets contributes effectively to addressing the knife-crime crisis.

Current study

Our research involved interviews with young people using photos of seized knives to encourage conversations about their thoughts and feelings in relation to such images. To our knowledge, this is the first study to ascertain young people’s views on the use of knife seizure images as a crime deterrent. Our primary objectives were to: (1) explore if knife seizure images were viewed by young people to be an effective deterrent against knife crime and (2) compare the views of young people living in areas of high knife crime with young people from areas of low knife crime in Glasgow, Scotland.

Method

Participants

A purposive sample (N = 20) was obtained, whereby participants were considered eligible for the study if they were: (1) aged 18–25; (2) currently living in an area identified as having high reported rates of knife crime within Glasgow (Canal Council Ward area; community sample) or in areas that were not identified as having high knife crime (comparative sample); (3) had lived in the area for at least 6 months; (4) could speak English well and were able to provide informed consent for participation. Young people with direct experience of being a victim of knife crime or involved in knife carrying or crime were excluded from the study. This was to help safeguard young people who had such direct and potentially traumatic experiences with the view to this being a focus for future longitudinal work with appropriate support and guidance. Information about the participants’ characteristics is detailed in .

Table 1. Participant characteristic.

Recruitment and procedure

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from the lead author’s University Ethics Committee. The study was promoted through an online recruitment poster shared via social media (e.g. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) and third sector agencies (e.g. SVRU, One Communities, North United Communities and Love Milton). Those who expressed an interest were sent a copy of the participant information sheet. They were offered an opportunity to ask questions about the study. All participants provided electronic written consent. Participants engaged in a semi-structured interview via Zoom, which is a viable tool for qualitative investigations due to its relative ease of use, cost-effectiveness, data management options and security (Archibald et al. Citation2019). The interviews were conducted during January–April 2021.

Conducting the interviews required attention to ethical considerations, the specific challenges facing young people during the COVID-19 pandemic and appropriate forms of communication. It was anticipated that young people might have fears about discussing knife carrying and crime. They were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time and issues regarding confidentiality and the protection of their anonymity were discussed. Information on suitable support, online resources and wellbeing advice was provided. With the participants’ consent, interviews were audio-recorded. A notebook was also used for keeping reflective field-notes. The data were transcribed verbatim and in full to ensure no data were lost that may have become significant in the wider analysis of the research findings.

Photo-elicitation during interviews

Photo-elicitation methodology involves conducting interviews with questions which are stimulated and guided by images (Collier and Collier Citation1986; Harper Citation1998; Citation2002). Guided by the principle that this methodology offers unique perspectives and responses in comparison to standard text-based research (Prosser Citation1998; Rose Citation2007), it has been successfully employed in research specifically involving young people (Walton and Niblett Citation2013) and was adopted in the current work. The series of knife images utilised for the interviews were obtained from published articles by UK news media (with appropriate permissions) and from stock images produced by the No Knives Better Lives (https://noknivesbetterlives.com/) programme. Both traditional (e.g. television news coverage, newspapers) and social media outlets have been used to promote knife seizure images. The images were used to encourage discussion on the following topics: (1) feelings about knife seizure images, (2) thoughts about areas of high knife crime, (3) aims of using knife seizure images, (4) police and media engagement with these images, and (5) the effects of images in influencing likelihood of knife carrying. The questions were developed from a review of relevant research and designed for the specific purposes of this study.

Analysis

The data were analysed in accordance with an inductive thematic approach (Braun and Clarke Citation2006; Braun, Clarke, and Hayfield Citation2019; Clarke and Braun Citation2018) adopting a comparative analysis (Fram Citation2013). The data set was read in its entirety by the first and second authors, looking for key themes that were evident across both community and comparative groups of young people, yet which potentially took differing forms in each of the cohorts. The intent behind this analytic approach was to identify group-based differences in a comparative sense (Riggs, Bartholomaeus, and Due Citation2016).

First, this involved becoming closely familiar with the data by reading and re-reading the transcripts. Initial codes were then generated through focusing on what the participants were saying in relation to their thoughts and feelings about knife seizure images. This consisted of identifying meaningful extracts and coding them into themes. All the data relevant to each theme were extracted, the themes were defined and named, and later refined depending on the overall meanings captured for each theme. Themes are key characters in the story being told about the data (Clarke and Braun Citation2019). Each theme is an active creation of the lead researcher that unites data that, at first sight, might appear disparate, capturing implicit meaning beneath the data surface (Braun and Clarke Citation2014). Preliminary themes created by the lead researcher were cross-checked by the co-researchers. This procedure resulted in three main themes largely present within all 20 interviews. Importantly, whilst these themes were captured across the community and comparative groups, we were interested in identifying any differences between the groups. Whilst each group gave relatively internally homogenous responses, between the groups the responses were diverse. In this sense, group-level differences are sub-themes under the main themes. In illustrating the themes from the data, any names used in the interviews have been changed to pseudonyms. Words or phrases inserted to make meanings clearer are enclosed in brackets.

Findings

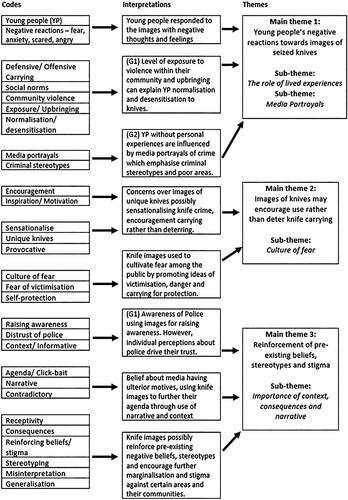

Three main themes (with associated sub-themes in brackets) were created: (1) Negative reactions towards images of seized knives (the role of lived experiences versus media portrayals), (2) Images of knives may encourage use rather than act as deterrent (culture of fear) and (3) Reinforcement of pre-existing negative beliefs, stigma and stereotypes (context, narrative and consequences). Our principal interest was to create an open dialogue to discuss the use of knife seizure images and to highlight any notable similarities and differences between the opinions of the young people within community and comparative groups, differentiated by their experiences of living in areas of high or low crime rates. A schematic diagram of the themes is presented in . Differences in perspective among the groups are highlighted within the sub-themes.

Young people’s negative reactions towards images of seized knives (The role of lived experiences versus media portrayals)

During the initial presentation of the knife seizure images, similarities were noted in the negative emotions captured by the young people in both community and comparative groups. These ranged from high to moderate levels of intensity although the most common expressions used were: ‘scary’ (Amy), ‘uneasy’ (James), ‘anxious’ (Ryan), ‘nervous’ (Hannah), ‘angry’ (Abbie) and ‘intimidating’ (Tina).

When asked about their initial thoughts and impressions of the images, the young people in both groups were quick to point out how ‘easily obtainable’ (Lina) select knives were, mainly referring to the smaller knives and those that were considered kitchen knives. They believed that, since ‘everyone has knives at home’ (Ivy), they were readily accessible for those considering using them as weapons.

A notable difference between the participants in the community and comparative groups concerned the means by which they had acquired awareness of knife carrying and their thoughts about knife crime. In the comparative group, 9 out of 10 of the young people explained that different sources of media (e.g. movies and news, social media) served as the foundation of their knowledge about knives:

My kind of understanding or like, you know, visual of them [knives] has always been like more in a media sense. (Susan).

As soon as I think of knife crime, violence and gangs, I think of men and young men, and I think that’s just from what I’ve seen on TV and the news and what I read in the paper. (Amy).

The ones like swords and the ones that look bigger and stuff, they’re a bit more threatening cause you don’t see them very often. (Susan).

In contrast, all of the community group drew upon their personal experiences of living in an area prominent for knife crime and being ‘very aware that there’s a lot of crime’ (Tina). They appeared to have developed an intimate understanding of the realities of knife carrying and crime, sharing details about how knife carrying was believed to be a ‘part of the area’ (Max) where they lived. As a result, the community participants described how exposure to knife crimes and violence led them to being ‘accustomed’ (Skye) to knives.

Just, you’re brought up being told there’s knife crime … . And that’s just how it is. It’s not right but … I’m not surprised by it. It’s not a hidden crime. People know about it. (Emily).

To feel safe, some people carry knives. Maybe not intending on using it but purely cause that area’s known for knife crime. Causes people to … join onto the sort of pattern that follows. (Emily).

I think most people have seen these things in their life. It’s not a shocking thing. There’s not different weapons to kill and different weapons to cut your chicken. They’re the same. (Cassie).

Images as an encouragement rather than deterrent (culture of fear)

There was a marked difference between how the young people described their own impression of the knife seizure images and how they perceived the images may affect others. Both groups said that they were personally opposed to carrying knives, providing different reasons such as ‘I don’t think in my whole life I would think to do it’ (Lina), ‘fear of the consequences’ (Amy), ‘risks of being arrested’ (Cassie) and concerns about harming others:

I just know that I could get caught and that could f**k up my whole life. I can’t. I can’t. I can’t let that happen … The stakes are too high for me. (Skye).

I think partially they kind of want the publicity to be like ‘this is a bad thing’, but in doing so, they kind of make it seem, you know, a little bit more thrilling … ‘Look at this cool, pretty image of this knife that was like used’. (Susan).

If people have been involved in knife crime, as the victim, they don’t want to see knives. It might be a trigger in some way. (Emily).

It would make most people be just like, scared and ‘em, feel uncomfortable and less safe and they’re like going about their lives when there probably isn’t much need for that, I don’t know. (Megan).

It’s going to lead to more people carrying knives cause then they have a sort of feeling that they need to protect themselves. (Isaac).

Reinforcing pre-conceived beliefs, stigma and stereotypes

How the knife images were perceived by young people was influenced by two important factors, the context surrounding the images and the source of the images (e.g. police, school, media). Ultimately, the young people in both groups agreed that knife seizure images were used with the intention to ‘raise awareness of the different types of weapons that are being used’ (Sandra) and to remind the public that knife crime is still a ‘serious issue’ (Shaun). However, it was evident that most believed there to be distinctive differences between how the media and the police portrayed the knife images to the public, which was often contradictory to the main objective.

Regarding the latter, both groups generally agreed that the police would likely use the knife seizure images responsibly for the purpose of deterring knife crime; albeit 3 out of 10 in the community group expressed concerns about ‘trusting the police’ (Max). In contrast, the media was perceived to have an ulterior motive for using the knife seizure images. The term ‘click-bait’ (Sandra) was frequently used, suggesting that the media used such images to lure the public to ‘view their stories’ (Ivy). Both groups shared similar concerns that the media were deliberate about selecting specific knife images that were most ‘provoking’ (Emily) in order to create their desired responses, such as ‘to get a reaction out from people’ (Tina). Young people believed that this was purposefully done to ‘exaggerate the truth’ (James) in relation to knife crime and to pursue their own agenda:

I think that media portrayals can affect a narrative in such a big way. They can completely change public perceptions of someone, and they would maybe use these for their political agenda. (Cassie).

The sort of contradictions in today’s society that leads to this situation where knife crime tends to happen … You should try to explain the socio-economic context … Cause otherwise, you’re just titillating your audience with graphic images and telling everyone ‘Oh look how dangerous society is’ you know. (Max).

I think that by using more of it (knife images), it will highlight areas to be worse than they are, almost putting people in the community under a stereotype. (Emily).

Associating these images with a certain place doesn’t exactly give off a great reputation so I wouldn’t go out my way to visit that place knowing that it isn’t very safe and that I didn’t have any business being in that area. (Hannah).

Discussion

Through using in-depth photo-elicitation interviews, our research is the first to gain insight into young people’s thoughts and feelings about the use of knife seizure images as a deterrent against knife carrying and crime within Glasgow, Scotland. We found that young people living in areas of high (community sample) and low (comparative sample) levels of knife crime reacted negatively towards the images and considered that they were more likely to encourage knife carrying than act as a deterrent. While young people living in areas of high knife crime referenced their own lived experiences in describing how they learned of knife carrying and crime within their communities, those living in areas of low knife crime tended to draw upon the media, which were felt to sensationalise and contribute towards a culture of fear. Given that cultivation research has drawn attention to the important role that the media play in shaping audiences’ perceptions of their social realities and crime risk (Chermak Citation1994; Pollock, Tapia, and Sibila Citation2021; Rhineberger-Dunn, Briggs, and Rader Citation2015), this finding highlights the importance of considering how the media’s institutional practices shape meanings in the mass production of messages and images involving knife carrying and crime and thereby shape public attitudes over the long term (Potter Citation1993).

Overexposure to crime news and images through diverse social media has been related to the formation of racial, gender and class stereotypes about criminality (e.g. Beckman and Rodriguez Citation2021; Dixon Citation2008; Intravia and Pickett Citation2019). Indeed, the vast majority of our participants from the comparative group admitted that knife images seized from an area with higher crime rates would likely influence their attitudes about the area and the people living in that area. This finding suggests that such images may contribute towards the stigmatisation of such areas and people living within them. That is, rather than raise awareness or address the root causes of knife crime, such as poverty and racial inequalities, such images may further exacerbate discriminatory views about perpetrators of knife crime (Humphreys et al. Citation2019). One possible mitigation, which was proposed by participants, is the provision of context to the seized images and also to (knife) crime overall. Context of the knife seizures may work to reduce their sensationalisation and help raise awareness of the upstream factors which often influence crime (Lodge et al. Citation2021). This may also help shift attitudes from blaming the individual to raising questions about the societal and institutional hurdles that often influence personal actions, all of which relate to the social determinants of health model (Lodge et al. Citation2021). Supporting previous work (DuRant et al. Citation2000; Holligan, McLean, and Deuchar Citation2017; Mrug, Madan, and Windle Citation2016), young people living in areas of high knife crime were found to normalise knife carrying, particularly as a form of protection. In contrast to fear of crime theory (Erčulj Citation2021), despite being potentially more vulnerable to knife crime, they did not describe being more fearful; they reported being desensitised towards it. Thus, the interplay of different experiential, environmental, personal and socio-cultural factors may further contribute towards the perceived negative impact of using knife seizure images as a deterrent (Frisby-Osman and Wood Citation2020; Leober and Farrington Citation2011). The mechanisms by which young people perceive their living environments include primary sources, such as personal experiences with crime, and secondary sources, such as local gossip about anti-social behaviour and crime within the community (Burcar Citation2013; Holligan, McLean, and Deuchar Citation2017). In our study, the young people in the community group noted that news about crime was readily shared within the community, echoing previous research (Bannister et al. Citation2010; Goodall et al. Citation2019), and this may have reinforced beliefs about fear of victimisation and encouraged knife-carrying beliefs (e.g. as self-protection, gang status). Such factors may also reinforce pre-existing negative beliefs, stigma and stereotypes about who is likely to carry a knife as well as the areas in which knife crime may be more prevalent (Coid et al. Citation2021; Grimshaw and Ford Citation2018; Williams et al. Citation2014). While knife seizure images may be used with the aim of deterring knife crime, young people expressed concerns about who (e.g. mistrust of police, media) and why (e.g. to increase views of media stories, provoke a reaction, political agenda) such images are used.

These findings highlight the importance of considering the narrative, source and context in which such images are used. Local, community-based organisations including former knife carriers, victims of knife offences, health and social care professionals, and experienced youth workers have an important role to play in developing and facilitating knife deterrent programmes and initiatives (Brennan Citation2019; England and Jackson Citation2013; Tribe, Harris, and Kneebone Citation2018). Their ability to relate to the unique experiences of young people suggests they might have a more positive impact since one of the factors associated with a heightened risk and frequency of offending among youth is mistrust of the police (Wilson, Sharp, and Patterson Citation2006). Trust in the police is essential in order for young people to be willing to engage and cooperate with the police (Skarlatidou et al. Citation2022). The policing of young people, especially through stop and search, has been increasingly seen as a response to knife crime; its use needs to be balanced against the limited evidence demonstrating its effectiveness. Recent research with young people in Scotland and England found that stop and search may damage trust in the police and perceptions of police legitimacy, resulting in increased offending behaviour (Murray et al. Citation2021). While the police have an important role in the prevention and detection of knife crime, their relationship with young people is key to the success of such initiatives.

Challenging negative stereotypes, which can influence judgments about knife crime and young people and indirectly affect policy-making about youth crime (Greene, Duke, and Woody Citation2017), is essential in raising awareness about knife crime. There is a real need to understand not just the causes, but also to understand the mechanisms (in particular the communication mechanisms) that can inflame and/or reduce the impact of these causes. The need for a public health approach, adopting a multi-agency response that seeks to understand and address the complex root causes, as well as responding to incidents of knife crime and youth violence is evident (Astrup Citation2019; Wells Citation2008). The SVRU has adopted such an approach throughout Scotland and, despite ongoing challenges in tacking knife crime, has witnessed a large fall in offending rates involving weapons for teenagers and people in their 20s (Scottish Trauma Audit Group Citation2016). Investing in youth services in health, education, social services and early intervention is needed in order to tackle the complex and widespread problem of knife crime (Astrup Citation2019).

In terms of the limitations of the current research, it is acknowledged that while rich and in-depth information was gathered within the context of this qualitative study, it is not possible to make generalisations based on our findings (Boudieu and Wacquant Citation1992). Nonetheless, transferable findings that will inform the development of our future work in the area of youth and knife crime prevention have emerged. Of importance is gaining a more nuanced understanding of the varying access to, and frequency of use of diverse social media by young people as this may be a significant influencing factor in how they respond to images of knives and knife crime prevention promoted through such platforms. Given the substantial increase in young people’s consumption of ‘contemporary’ mass media such as the Internet and social media, it is important that future research explores how these growing media platforms influence their attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions of knife carrying and crime (Intravia et al. Citation2017).

We also had an under-representation of young people who were male and from diverse ethnicities across both groups and it is possible that they may have different perspectives towards knife seizure images. To address this limitation, we are currently building an online quasi-experimental survey using images of seized knives incorporating the views of a wider and more diverse demographic (e.g. older adults, ethnic minorities, gender) of participants throughout Scotland. We envisage that this will help us understand any intergenerational and socio-cultural differences in how the use of knife seizure images are perceived.

Research with school-aged children is needed given that knife images have been used in school campaigns aiming to tackle knife crime (England and Jackson Citation2013). Future work with those that have been directly involved with knife crime (as perpetrator and/or victim) will also help illuminate the complexities associated with the cycle of knife crime (Ward Citation2019). We recommend utilising participatory approaches involving young people in all stages of the research process, which would help increase community engagement in research aiming to inform intervention programme development, particularly in areas of high knife crime. There is a need for high-quality, multi-method, longitudinal research to evaluate knife deterrent programmes incorporating images of knives in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the key components of such programmes that are most effective in deterring knife carrying and crime. Exploring the important contextual links between mental health, poverty and knife crime should contribute to efforts aimed at reducing the knife carrying and crime and intervention development (Haylock et al. Citation2020).

Conclusion

Our study provides important insight into young people’s thoughts and feelings in relation to the use of knife seizure images as a crime deterrent. We highlight areas of convergence and divergence between young people’s perspectives in relation to those living in areas of high knife crime in Glasgow and those in areas with lower rates. Our findings suggest that the use of knife seizure images may provoke negative reactions and create a culture of fear (as exacerbated by the media), potentially encourage knife carrying (e.g. for protection) and perpetuate negative stereotypes and pre-conceived beliefs about who is likely to carry a knife. We need to understand young people’s perspectives and experiences of knife crime, raise awareness and engagement with relevant partner agencies and community-based activities, and encourage efforts to build trust and cooperation between young people affected by knife crime. The importance of engaging with young people and other key stakeholder groups to gain an understanding of their perceived risks, worries, needs and expectations, especially about the reasons for knife carrying and crime, will provide the basis for establishing a trusting relationship, paving the way for long-term, effective solutions to knife crime.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ang, R. P., V. S. Huan, S. H. Chua, and S. H. Lim. 2012. “Gang Affiliation, Aggresion, and Violent Offending in a Sample of Youth Offenders.” Psychology, Crime & Law 18 (8): 703–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2010.534480.

- Archibald, M. M., R. C. Ambagtsheer, M. G. Casey, and M. Lawless. 2019. “Using Zoom Videoconferencing for Qualitative Data Collection: Perceptions and Experiences of Researchers and Participants.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18. doi:10.1177/1609406919874596.

- Astrup, J. 2019. “Knife Crime: Where’s the Public Health Approach?” Community Practitioner 92 (6): 14–17.

- Bannister, J., J. Pickering, S. Batchelor, M. Burman, K. Kintrea, and S. McVie. 2010. Troublesome Youth Groups, Gangs and Knife Carrying in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Batchelor, S., A. Fraser, M. Burman, and S. McVie. 2010. Youth Violence in Scotland: Literature Review. Scottish Government.

- Beckman, L., and N. Rodriguez. 2021. “Race, Ethnicity, and Official Perceptions in the Juvenile Justice System: Extending the Role of Negative Attributional Stereotypes.” Criminal Justice and Behavior 48 (11): 1536–1556.

- Bhatia, M., S. Poynting, and W. Tufail. 2018. Media, Crime and Racism. Camden: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bourdieu, P., and L. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2014. “What Can “Thematic Analysis” Offer Health and Wellbeing Researchers?” International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 9: 1. doi:10.3402/qhw.v9.26152.

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, and N. Hayfield. 2019. “‘A Starting Point for Your Journey, not a Map’: Nikki Hayfield in Conversation with Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke About Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 19 (2): 424–445.

- Brennan, I. R. 2019. “Weapon-Carrying and the Reduction of Violent Harm.” British Journal of Criminology 59 (1): 571–593.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1977. “Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development.” American Psychologist 32 (7): 513–531.

- Burcar, V. 2013. “Doing Masculinity in Narratives About Reporting Violent Crime: Young Male Victims Talk About Contacting and Encountering the Police.” Journal of Youth Studies 16 (2): 172–190.

- Chadee, D., and R. Surette. 2019. “Exploring the Relationship Between Weapons Desirability and Media.” Psychology of Popular Media Culture 8 (4): 464–472.

- Chermak, S. M. 1994. “Body Count News: How Crime is Presented in the News Media.” Justice Quarterly 11 (4): 561–582.

- Clarke, V., and V. Braun. 2018. “Using Thematic Analysis in Counselling and Psychotherapy Research: A Critical Reflection.” Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 18 (2): 107–110.

- Clarke, V., and V. Braun. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597.

- Coid, J., Y. Zhang, Y. Zhang, J. Hu, L. Thomson, P. Bebbington, and K. Bhui. 2021. “Epidemiology of Knife Carrying among Young British men.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 56: 1–19.

- Collier, J., and M. Collier. 1986. Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method. Revised ed. University of New Mexico Press.

- Dahlberg, L. L., and J. A. Mercy. 2009. “History of Violence as a Public Health Issue.” AMA Virtual Mentor 11: 167–172.

- Day, C., D. Michelson, S. Thomson, P. Caroline, and L. Draper. 2012. “Evaluation of a Peer Led Parenting Intervention for Disruptive Behaviour Problems in Children: Community Based Randomised Controlled Trial.” British Medical Journal (BMJ) 344: e1107. doi:10.1136/bmj.e1107.

- Densley, J. A., and A. Stevens. 2014. “We’ll Show you Gang": The Subterranean Structuration of Gang Life in London.” Criminology and Criminal Justice 15 (1): 102–120.

- Dixon, T. 2008. “Crime News and Racialized Beliefs: Understanding the Relationship Between Local News Viewing and Perceptions of African Americans and Crime.” Journal of Communication 58: 106–125.

- DuRant, R. H., D. Altman, M. Wolfson, S. Barkin, S. Kreiter, and D. Krowchuk. 2000. “Exposure to Violence and Victimization, Depression, Substance Use, and the use of Violence by Young Adolescents.” The Journal of Pediatrics 137 (5): 707–713.

- England, R., and R. Jackson. 2013. “A Nurse Clinician’s Approach to Knife Crime Prevention.” British Journal of Nursing 22 (13): 774–778.

- Erčulj, V. 2021. “The ‘Young and the Fearless’: Revisiting the Conceptualisation of Fear of Crime.” Quality & Quantity 256 (3): 1177–1192.

- Finckenauer, J. O. 1980. “Scared Straight and the Panacea Phenomenon—Discussion.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 347 (1): 213–217.

- Foster, R. 2013. Knife Crime Interventions: What Works? Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research. http://www.sccjr.ac.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2014/01/SCCJR_Report_No_04.2013_Knife_Crime_Interventions.pdf.

- Fram, S. M. 2013. “The Constant Comparative Analysis Method Outside of Grounded Theory.” Qualitative Report 18: 1–25.

- Fraser, A. 2013. “Street Habitus: Gangs, Territorialism and Social Change in Glasgow.” Journal of Youth Studies 16 (8): 970–985.

- Frisby-Osman, S., and J. L. Wood. 2020. “Rethinking How We View Gang Members: An Examination Into Affective, Behavioural, and Mental Health Predictors of UK Gang-Involved Youth.” Youth Justice 20 (1-2): 93–112.

- Gavine, A., D. J. Williams, and P. Donnelly. 2014. The Effectiveness of Universal School-based Programmes Aimed at the Primary Prevention of Violence in Secondary School-aged (11-18 years) Young People: Results from a Systematic Review . American Public Health Association Annual Meeting.

- Gerbner, G., L. Gross, M. Morgan, and N. Signorielli. 1994. Growing up with Television: The Cultivation Perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbam Associates.

- Gilroy, P., T. Sandset, S. Bangstad, and G. R. Høibjerg. 2019. “A Diagnosis of Contemporary Forms of Racism, Race and Nationalism: A Conversation with Professor Paul Gilroy.” Cultural Studies 33 (2): 173–197.

- Goodall, C. A., F. MacFie, D. I. Conway, and A. D. McMahon. 2019. “Assault–Related Sharp Force Injury among Adults in Scotland 2001–2013: Incidence, Socio-Demographic Determinants and Relationship to Violence Reduction Measures.” Aggression and Violent Behaviour 46: 190–196.

- Greene, E., L. Duke, and W. D. Woody. 2017. “Stereotypes Influence Beliefs About Transfer and Sentencing of Juvenile Offenders.” Psychology, Crime & Law 23 (9): 841–858.

- Grierson, J. 2020. “Knife Offences Hit Record High in 2019 in England and Wales.” The Guardian, April 23. Accessed September 4, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/apr/23/knife-offences-hit-record-high-in-2019-in-england-and-wales.

- Grimshaw, R., and M. Ford. 2018. Young People, Violence and Knives - Revisiting the Evidence and Policy Discussions. UK Justice Policy Review Focus, November. https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/sites/crimeandjustice.org.uk/files/Knife%20crime.%20November.pdf.

- Gutsche Jr, R. E., and Salkin, E. R. 2011. “News Stories: An Exploration of Independence Within Post-Secondary Journalism.” Journalism Practice 5 (2): 193–209.

- Hall, S. 1980. “Race, Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance.” In Sociological Theories: Race and Colonialism, edited by United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 305–345. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. 1996. “New Ethnicities.” In Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by D. Morley, 441–449. New York: Routledge.

- Harding, S. 2020. “Getting to the Point?” Reframing Narratives on Knife Crime. Youth Justice 20 (1-2): 31–49.

- Harper, D. 1998. “An Argument for Visual Sociology.” In Image-based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers (pp. 24–41), edited by J. Prosser. London: Falmer Press.

- Harper, D. 2002. “Talking About Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation.” Visual Studies 17 (1): 13–26.

- Haylock, S., T. Boshari, E. C. Alexander, A. Kumar, L. Manikam, and R. Pinder. 2020. “Risk Factors Associated with Knife-Crime in United Kingdom among Young People Aged 10-24 Years: A Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health 20 (1451): 1–19.

- Holligan, C., R. McLean, and R. Deuchar. 2017. “Weapon-Carrying Among Young Men in Glasgow: Street Scripts and Signals in Uncertain Social Spaces.” Critical Criminology 25 (1): 137–151.

- Humphreys, D. K., M. D. Esposti, F. Gardner, and J. Shepherd. 2019. “Violence in England and Wales: Does Media Reporting Match the Data?” British Medical Journal 367 (16040): 1–19.

- Idriss, S. 2021. “Researching Race in Australian Youth Studies.” Journal of Youth Studies 25 (3): 275–289.

- Intravia, J., and J. T. Pickett. 2019. “Stereotyping Online? Internet News.” Social Media, and the Racial Typification of Crime. Sociological Forum 34 (3): 616–642.

- Intravia, J., K. T. Wolff, R. Paez, and B. R. Gibbs. 2017. “Investigating the Relationship Between Social Media Consumption and Fear of Crime: A Partial Analysis of Mostly Young Adults.” Computers in Human Behavior 77 (1): 158–168.

- Kelly, Y., A. Zilanawala, C. Booker, and A. Sacker. 2018. “Social Media use and Adolescent Mental Health: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study.” EClinicalMedicine 6: 59–68.

- Leober, R., and D. P. Farrington. 2011. Young Homicide Offenders and Victims: Risk Factors, Prediction and Prevention from Childhood, 1st ed. New York: Springer.

- Leyland, A. H., and R. Dundas. 2010. “The Social Patterning of Deaths due to Assault in Scotland, 1980-2005: Population-Based Study.” Journal of Epidemiol Community Health 64: 432–439.

- Lipsey, M. W. 2009. “The Primary Factors That Characterize Effective Interventions with Juvenile Offenders: A Meta-Analytic Overview.” Victims and Offenders 4 (2): 124–147.

- Local Government Association. 2018. Public Health Approaches to Reducing Violence. Local Government Association, June. https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/15.32%20-%20Reducing%20family%20violence_03.pdf#:~:text=What%20is%20a%20public%20health%20approach%20to%20reducing,of%20all%20individuals%20by%20addressing%20underlying%20risk%20factors.

- Lodge, E. K., C. Hoyo, C. M. Gutierrez, K. M. Rappazzo, M. E. Emch, and C. L. Martin. 2021. “Estimating Exposure to Neighborhood Crime by Race and Ethnicity for Public Health Research.” BMC Public Health 21 (1): 1–13.

- Lynes, A., C. Kelly, and E. Kelly. 2020. “THUG LIFE: Drill Music as a Periscope Into Urban Violence in the Consumer age.” The British Journal of Criminology 60 (5): 1201–1219.

- Measor, L., and P. Squires. 2000. Young People and Community Safety: Inclusion, Risk, Tolerance and Disorder. Furnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Mrug, S., A. Madan, and M. Windle. 2016. “Emotional Desensitization to Violence Contributes to Adolescents’ Violent Behaviour.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 44: 75–86.

- Murray, K., S. McVie, D. Farren, L. Herlitz, M. Hough, and P. Norris. 2021. “Procedural Justice, Compliance with the law and Police Stop-and-Search: A Study of Young People in England and Scotland.” Policing and Society 31 (3): 263–282.

- Nijjar, J. S. 2021. “Police–School Partnerships and the war on Black Youth.” Critical Social Policy 41 (3): 491–501.

- No Knives Better Lives. 2019. New Stock Images on Knife Crime Aim to Change Media Narrative Around Young People. March 12. noknivesbetterlives.com: https://noknivesbetterlives.com/practitioners/discussion/new-stock-images-on-knife-crime/.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). 2019. Office for National Statistics (ONS). April 26. www.ons.gov.uk: file:///C:/Users/alb19208/Downloads/Crime%20in%20England%20and%20Wales%20year%20ending%20March%202018.pdf.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). 2020. Office for National Statistics. September 29. www.gov.scot: file:///C:/Users/alb19208/Downloads/recorded-crime-scotland-2019-20%20(1).pdf.

- Palasinski, M., and D. W. Riggs. 2012. “Young White British Men and Knife-carrying in Public: Discourses of Masculinity, Protection and Vulnerability.” Critical Criminology 20 (4): 463–476.

- Pestrosino, A., C. Turpin-Petrosino, M. E. Hollis-Peel, and J. G. Lavenberg. 2013. “‘Scared-Straight’ and Other Juvenile Awareness Programs for Preventing Juvenile Deliquency.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 30 (4): 1–55.

- Petrosino, A., C. T. Petrosino, and J. Buehler. 2005. ““Scared Straight” and Other Juvenile Awareness Programs for Preventing Juvenile Delinquency.” Campbell Systematic Reviews 1 (1): 1–62.

- Pollock, W., N. D. Tapia, and D. Sibila. 2021. “Cultivation Theory: The Impact of Crime Media’s Portrayal of Race on the Desire to Become a US Police Officer.” International Journal of Police Science & Management 24 (1): 42–52.

- Potter, W. J. 1993. “Cultivation Theory and Research: A Conceptual Critique.” Human Communication Research 19 (4): 564–601.

- Prosser, J. 1998. “The Status of Image-Based Research.” In Image-based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers (pp. 97–112), edited by J. Prosser. London: Falmer Press.

- Rainey, S. R., J. Simpson, S. Page, M. Crowley, J. Evans, M. Sheridan, and A. J. Ireland. 2015. “The Impact of Violence Reduction Initiatives on Emergency Department Attendance.” Scottish Medical Journal 60 (2): 90–94. doi:10.1177/0036933015576297.

- Rhineberger-Dunn, G., S. Briggs, and N. Rader. 2015. “Clearing Crime in Prime-Time: The Disjunture Between Fiction and Reality.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 41: 255–278.

- Riggs, D. W., C. Bartholomaeus, and C. Due. 2016. “Public and Private Families: A Comparative Thematic Analysis of the Intersections of Social Norms and Scrutiny.” Health Sociology Review 25 (1): 1–17.

- Rogan, A. 2021. “The Demonization of Delinquency: Contesting Media Reporting and Political Rhetoric on Youth Crime.” International Modern Perspectives on Academia and Community Today 1. doi:10.36949/impact.v1i1.35.

- Rosbrook-Thompson, J. 2019. “Legitimacy, Urban Violence and the Public Health Approach.” Urbanities-Journal of Urban Ethnography 9 (S2): 37–43.

- Rose, G. 2007. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Russell, K. 2021. What Works to Prevent Youth Violence: A Summary of the Evidence. February. Scottish Violence Reduction Unit: http://www.svru.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/570415_SCT0121834710-001_p2_YVMainReport.pdf.

- Scottish Government. 2021. Violence Including Knife Crime. https://www.gov.scot/policies/crime-prevention-and-reduction/violence-knife-crime/#:∼:text=Scotland%20uses%20a%20public%20health,more%20we%20need%20to%20do.

- Scottish Trauma Audit Group. 2016. Audit of Trauma Management in Scotland Annual Report. NHS National Services Scotland. https://www.stag.scot.nhs.uk/docs/Scottish-Trauma-Audit-Group-Annual-Report-2016.pdf Scotland.

- Shaw, D. 2019. “Ten Charts on the Rise of Knife Crime in England and Wales.” BBC News. July 18. Accessed September 4, 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-42749089.

- Silvestri, A., M. Oldfield, P. Squires, and R. Grimshaw. 2009. Young People, Knives and Guns: A Comprehensive Review, Analysis and Critique of Gun and Knife Crime Strategies. London: Centre for Crime and Justice Studies.

- Skarlatidou, A., L. Ludwig, R. Solymosi, and B. Bradford. 2022. “Understanding Knife Crime and Trust in Police with Young People in East London.” Crime & Delinquency 1–28. doi:10.1177/00111287211029873.

- Smolej, M., and J. Kivivuori. 2006. “The Relation Between Crime News and Fear of Violence.” Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention 7 (2): 211–227.

- Squires, P. 2009. “The Knife Crime ‘Epidemic’and British Politics.” British Politics 4 (1): 127–157.

- Surko, M., D. Ciro, E. Carlson, N. Labor, V. Giannone, E. Diaz-Cruz, K. Peake, and I. Epstein. 2005. “Which Adolescents Need to Talk About Safety and Violence?.” Social Work in Mental Health 3 (1/2): 103–120.

- Thompson, R. R., N. M. Jones, E. A. Holman, and R. C. Silver. 2019. “Media Exposure to Mass Violence Events Can Fuel a Cycle of Distress.” Science Advances 5 (4): 1–6.

- Tribe, H. C., A. Harris, and R. Kneebone. 2018. “Life on a Knife Edge: Using Simulation to Engage Young People in Issues Surrounding Knife Crime.” Advances in Stimulation 3 (1): 1–9.

- Vulliamy, P., M. Faulkner, G. Kirkwood, A. West, B. O’Neill, M. P. Griffiths, F. Moore, and K. Brohi. 2018. “Temporal and Geographic Patterns of Stab Injuries in Young People: A Restrospective Cohort Study from a UK Major Trauma Centre.” BMJ Open 8 (10): e023114.

- Walton, G., and B. Niblett. 2013. “Investigating the Problem of Bullying Through Photo Elicitation.” Journal of Youth Studies 16 (5): 646–662.

- Ward, M. 2019. “The Knife Crime Epidemic: In Defence of Schools.” British Journal of School Nursing 14 (6): 298–299.

- Wells, J. 2008. “Knife Crime Education.” Emergency Nurse 16 (7): 30–32. doi:10.7748/en2008.11.16.7.30.c6784.

- Williams, D. J., D. Currie, W. Linden, and P. D. Donnelly. 2014. “Addressing Gang-Related Violence in Glasgow: A Preliminary Pragmatic Quasi-Experimental Evaluation of the Community Initiative to Reduce Violence (CIRV).” Aggression and Violent Behavior 19 (6): 686–691.

- Wilson, D., C. Sharp, and A. Patterson. 2006. Young People and Crime: Findings from the 2005 Offending, Crime and Justice Survey. December. Home Office: https://aashaproject.files.wordpress.com/2008/08/young-people-and-crime-home-office.pdf.

- Wood, R. 2010. “Youth Deaths: The Reality Behind the ‘Knife Crime’ Debate.” Institute of Race Relations Briefing Paper, 5.

- Wortley, E., and A. Hagell. 2021. “Young Victims of Youth Violence: Using Youth Workers in the Emergency Department to Facilitate ‘Teachable Moments’ and to Improve Access to Services.” Association for Young People’s Health 106: 53–59.

- Youth Justice Board. 2010. Exploring the Needs of Young Black and Minority Ethnic Offenders and the Provision of Targeted Interventions. January 1. Youth Justice Board. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/354686/yjb-exploring-needs-young-black-minority-ethnic-offenders.pdf.