ABSTRACT

Second-home tourism is a popular form of tourism in many countries. Sweden has over 600,000 second homes and more than half of the population have access to such properties. Previous literature on second-home tourism indicates that it impacts local communities and municipalities in many different ways, ranging from public services and land-use planning to the housing market and the local economy. However, it has not been sufficiently investigated how, where and by which spatial patterns these impacts might come into effect. Previous research has mostly been in the form of case studies, making generalizations difficult. This paper examines whether a theorized heterogeneity of second-home landscapes transfers into actual spatial variance in the impacts of second-home tourism. The investigation is done through semi-structured interviews with officials from 20 Swedish municipalities, selected using a theoretical model and comprehensive quantitative data. Results reveal considerable variance between different locations and argues for more context-aware second-home research.

Introduction

Contemporary society is increasingly mobile, or even hypermobile (Hall, Citation2015a; Sheller & Urry, Citation2006; Urry, Citation2007). Mobilities such as shopping, VFR tourism, second-home tourism and business travel are increasingly part of everyday life globally (Gale, Citation2008; Hall, Citation2005, Citation2015a). Second-home tourism is a popular form of tourism, particularly in the Nordic countries, where the number of second homes is large and their use widespread (Adamiak et al., Citation2015; Marjavaara, Citation2008; Overvåg & Berg, Citation2011). Sweden has over 600,000 second homes, and national statistics show that half of the population have access to second homes (Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017; Statistics Sweden, Citation2014). A survey among Swedish second-home owners in 2010 showed them spending on average about three months per year in their second homes, indicating a significant population of temporary residents in Swedish municipalities (Müller, Nordin, & Marjavaara, Citation2010). The temporary residency of second-home tourists has real impacts on local communities. Previous research has revealed a range of such potential impacts of second-home tourism, such as displacement of permanent residents, involvement in local planning, mismatch of public funds, land-use planning, gentrification, and conversion of primary residences into second homes (Hall, Citation2015b; Halseth, Citation2004; Hoogendoorn & Marjavaara, Citation2018; Müller, Citation2011; Müller & Marjavaara, Citation2012; Paris, Citation2011).

However, it has not been sufficiently investigated how, where and by which spatial patterns these impacts might come into effect. This is because research into the impacts of second-home tourism has primarily been conducted in the form of case studies, wherein particular communities, municipalities or regions are under scrutiny; see for example Adamiak (Citation2016); Blondy, Plumejeaud, Vacher, and Vye (Citation2014); Gomes, Pinto, and Almeida (Citation2017); Hoogendoorn and Visser (Citation2010). These case studies paint a picture of considerable heterogeneity between different settings and impacts, but it is difficult to ascertain whether they illustrate local exceptions or general trends. Departing from Müller, Hall, and Keen (Citation2004), Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017) argued that second-home tourism is a diverse form of dwelling use that should have equally diverse spatial effects. They argued that differences in the second-home stock should carry over generally into local differences regarding the impacts of second-home tourism and, by extension, how local authorities handle these impacts. But the literature on second homes does not recognize such heterogeneity. In other words, it is unclear whether the impacts described in the second-home literature are generalizable to second-home destinations, whether they vary across space and, if so, according to what patterns such variation takes place.

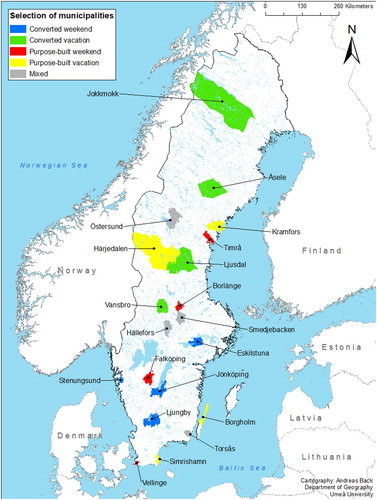

Building on Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017), the present paper examines whether a theorized heterogeneity of second-home landscapes transfers into actual spatial variance in the impacts of second-home tourism. By interviewing planning officials from 20 different Swedish municipalities, the aim is to investigate how different municipalities perceive and handle the impacts of second-home tourism. The selection of municipalities is made using comprehensive quantitative data on all second homes in Sweden from the georeferenced database ASTRID (Citation2015) at Umeå University and the mapping of second-home landscapes by Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017). Combining these to make a data-driven selection of municipalities makes it possible to draw more generalizable conclusions than from previous case studies, where cases are often fewer and selected using qualitative procedures.

The paper is structured as follows. The following section introduces the reader to the concept of second-home landscapes. This is followed by a methodological section discussing the selection of municipalities and conducting of interviews. These sections are succeeded by a short introduction to the Swedish planning system and the role of municipalities, followed by the results of the interviews, which are presented, discussed and tailed by a number of brief concluding remarks.

Heterogeneous second-home landscapes

This paper builds on two previous studies: a typology of second homes in Müller et al. (Citation2004) and the mapping of second-home landscapes by Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017). Both work on the underlying assumption of difference, meaning that different geographical contexts entail different impacts from second-home tourism. Müller et al. (Citation2004) separate second-homes into four different types depending on frequency of use and supply of amenities in the surrounding area. The types are called (1) converted weekend second homes, (2) converted vacation, (3) purpose-built weekend and lastly (4) purpose-built vacation second homes. Each of these four types correspond to certain geographical settings, meaning differences in amenities and second-home use. Müller et al. (Citation2004, p. 16) describe converted weekend second homes as being located in an ‘ordinary rural landscape in urban hinterlands’, converted vacation in ‘extensively used peripheral landscapes’, purpose-built weekend in ‘amenity rich hinterlands, coast and mountain landscapes’ and purpose-built vacation in ‘major vacation areas, coast and mountain landscapes’.

Whereas Müller et al. (Citation2004) theorize difference among second homes and link such differences to certain contexts, Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017) map the geography of these differences in Sweden using a set of quantitative variables on all second homes in the country. The variables used are linked to the premises underlying the typology in Müller et al. (Citation2004), for example second-home density, assessed property values and distance between the owners’ permanent residences and second homes. In effect, they transfer the four second-home types by Müller et al. (Citation2004) to four types of geographical areas called second-home landscapes. Each of the four second-home landscapes are assumed to share traits with a type of second home from Müller et al. (Citation2004). As such, they transfer the differences in the typology of Müller et al. (Citation2004) to a theoretical concept mapping the spatial differences of second-home tourism. Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017) anticipate impacts of second-home tourism to vary between these different second-home landscapes. The present paper builds on these two previous studies. In short, is can be seen as an inquiry into the actual facts on the ground and whether they resemble the heterogeneity anticipated by Müller et al. (Citation2004) and Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017).

Interviewing municipalities

Choice of method

The source of data in this paper are municipalities. There are principally two ways to get municipalities’ views of second-home tourism, through official documents or interviews. Documents have not been examined in this paper, primarily because Swedish municipalities often exclude or skim over second homes in their planning documents (Frykholm, Citation2017). Instead, this study is based on semi-structured interviews in order to get sufficient information and a deeper understanding of the subject (Dunn, Citation2016; Robinson, Citation1998). Using semi-structured interviews allowed for the collection of sufficiently rich and diverse data material for analysis without losing the opportunity to pose follow-up questions (Dunn, Citation2016; Rubin & Rubin, Citation2011). Structured interviews could have allowed for more respondents, but with less depth, while unstructured interviews could not be managed with a sufficient number of municipalities. For practical reasons, interviews were held via telephone.

All in all, planning officials from 20 municipalities were interviewed. This sample size was chosen in order to be able to better reflect the differences and similarities between municipalities and second-home landscapes in the data. The selection was data-driven, based on public data with the exact number and location of second homes from the georeferenced database ASTRID at Umeå University (ASTRID, Citation2015). This data was used in conjunction with the second-home landscapes in Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017) to select 20 municipalities.

The selection was made using GIS software by overlapping the second-home landscapes from Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017) with a point layer of all second homes in Sweden, where each point represented the exact location of a second home. In this way the number of second homes in each second-home landscape could be tallied for all municipalities. Using this information four municipalities were selected to represent each second-home landscape, for a total of 16 municipalities in four groups, one group for each second-home landscape. These 16 were all extreme cases in the data, which meant having the largest possible share of second homes in one of the four second-home landscapes. The second-home landscapes in Back and Marjavaara (Citation2017) intersect municipal jurisdictions, so that different second-home landscapes cover parts of most municipalities. But in the 16 extreme cases selected here, between 45 and 99% of all second homes were located in one of the second-home landscapes (see ). Another four municipalities were selected that had many second homes, but with no dominance of any single second-home landscape. They were included as a mixed group in order to give a more complete picture of the presumed variation in second-home impacts, but also as a way of controlling how well the second-home landscapes captured real circumstances. In a few instances, minor adjustments were made to the selection to get a geographical spread of municipalities, so as to avoid having neighbouring municipalities in the same group. Apart from these adjustments, made to provide more nuanced interview data, the selection was completely driven by quantitative data. Basic information on the demography and size of the selected 20 municipalities can be seen in . Elementary data on second-home tourism in the municipalities is available in , and geographical location in .

Table 1. Basic information on the selected municipalities (Statistics Sweden, Citation2018b, Citation2018c).

Table 2. Second homes in selected municipalities (ASTRID, Citation2015).

In order to get both broad insight and detailed knowledge into different planning-related topics, all interviewees were civil servants, most of them working directly with planning issues or public service provision. A majority were heads of planning or public service departments, but some were tourism developers or planning engineers, and in one instance the head manager of a municipality. None of the interviewees worked specifically with the promotion of second-home tourism in their municipalities. To avoid political bias, elected officials were excluded from the study. In cases in which interviewees did not have complete knowledge of all the themes discussed, the interview was supplemented with further information – via telephone or e-mail – from others employed within the municipality in question.

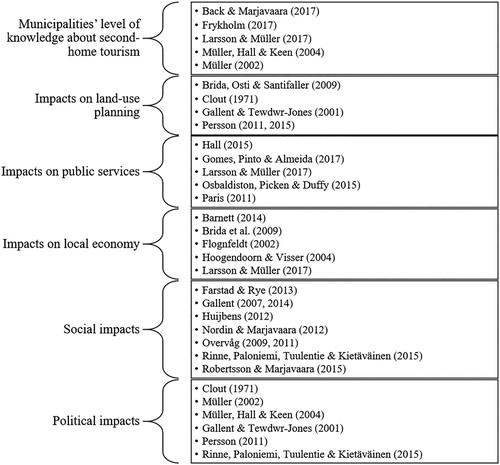

The interviews were conducted via telephone from November 2017 to March 2018, using a scheme of talking points (see ). The talking points revolved around broad themes extracted from previous literature on second-home tourism and planning issues. In addition, questions around second homes and second-home tourism in the municipality were posed to get an overall picture of the level of knowledge on second-home tourism. The interview data from all municipalities was compiled using the themes in , and was then analysed for each municipality and each group of municipalities. This examination searched for reoccurring patterns, similarities and differences between municipalities in the same second-home landscape and between municipalities in different second-home landscapes. Data connected to the impacts of second-home tourism on the housing market was also collected during the interviews, but this will be treated in a separate paper.

The results from the interviews are summarized by theme and type of municipality in below. Note that the terms used in the summary are qualitative descriptions, not representative of a quantitative scale.

Table 3. Summary overview of interviews.

Impacts of second-home tourism

Swedish municipalities and planning system

Before going into the actual analysis of the interview data, it might be pertinent to offer a brief overview of the Swedish municipal and planning system to give the reader a better understanding of the context for this study. Sweden is divided into 290 municipalities of varying size and population density. Kiruna, the largest municipality, is about 20,000 km2, whereas Sundbyberg is the smallest with its 8.8 km2 (Statistics Sweden, Citation2018c). Stockholm is the most populous, with nearly a million inhabitants, while Bjurholm, with only about 2,500 residents, is at the opposite end of the scale (Statistics Sweden, Citation2018c). No matter these variations, all municipalities have exclusive control over land-use and water resource planning (Planning and Building Act, Citation2010). They are the primary sources of vital public services in Sweden, such as libraries, elderly care, and the entire educational system from pre-school to upper secondary education. They are also in charge of building permits, infrastructure, waste disposal and sewerage (SKL, Citation2017). Many of these services are directly impacted by second-home tourism (Larsson & Müller, Citation2017; Persson, Citation2011). Municipal sources of income for covering expenses are income taxes, fees for services rendered, and property fees.

Similarities in relation to second-home tourism

Before going into what characterizes the different groups of municipalities in the study, it is worthwhile to note a few things that are common to them. These issues unite all or most of municipalities in the study. Refer to for an overview of the differences and similarities between the interviewed municipalities.

First of all, the level of specific knowledge about second homes and second-home tourism was generally quite vague. As can be seen in , most interviewees had only general knowledge about second homes in their municipality. An interviewee from Torsås coined the illuminating phrase ‘takenforgrantedness’ to describe her municipality’s stance on second-home tourism. The interviewee from Åsele said that ’no one has any knowledge about this’, while respondents from Östersund, Borlänge and Simrishamn said that second-home tourism is ‘almost never discussed’, ‘hardly noticed’ or ‘something that’s just there’. Information on who the second-home tourists were and where they hailed from was equally unclear. A few interviewees knew of inquiries into register data to find out where second-home owners in their municipality were registered as permanent residents, but the absolute majority of interviewees had no such information and as such resorted to educated guesses or ‘hunches’. Although they had limited information on the number of second homes, most interviewees had a notion as to whether the typical second home in their municipalities was a converted or purpose-built house, the kind of setting where most of them were located, whether the owners were locals or non-locals, and whether the number of second homes was increasing or decreasing. As can be seen in , the interviewees with the most substantial knowledge on second homes represented municipalities dominated by purpose-built vacation second-homes, such as Simrishamn and Härjedalen.

Another part of knowledge about second-home tourism’s impacts concerns public expenditures associated with it. Taxation is often discussed in relation to second-home tourism and its impacts on local communities, public services and housing markets (Gallent, Citation1997; Langdalen, Citation1980; Paris, Citation2011). In 2008, the previous Swedish state property tax based on assessed property value was transformed into a more or less uniform municipal property fee (Swedish Tax Agency, Citation2015). This meant that municipalities were given a new source of revenue from second homes, to finance things such as public services. Most interviewees in this study had only a vague notion of these fees and their contribution to the municipal coffers. The only deviation from this pattern was the second-home hotspot Härjedalen, where the interviewee used expenses for public services available to second-home tourists to illustrate that the property fee had provided a welcome windfall for his municipality since its introduction.

All but one of the interviewees stated that their municipality had plans devised to increase the number of tourists, but it was only in two municipalities that this included policies explicitly dealing with second-home tourism. This picture was repeated in the fact that second-home tourism was only seldom a political issue in the municipalities included here (see Political impacts in ). Most interviewees shared the view that second-home tourism was a topic either removed from political discourse or where politicians of all stripes were in agreement. Often, discussions on the impacts of second-home tourism were present primarily among planners and other municipal staff as an issue of varying practical importance. Since several interviewees said that second homes were an issue that was either taken for granted or hardly noticed, this might explain why municipalities with a highly disparate relative number of second homes shared a similar mind-set on the topic. This seems to be in line with Frykholm (Citation2017), showing that only a third of Swedish municipalities mention second homes in their comprehensive plans.

As for social impacts of second-home tourism (), none of the interviewees had heard about any special-interest associations for second-home owners as discussed by, for example, Rinne, Paloniemi, Tuulentie, and Kietäväinen (Citation2015). On the other hand, most confirmed the image conveyed by Nordin and Marjavaara (Citation2012) of second-home owners’ involvement in other organizations along with permanent residents, such as village associations or cooperative associations for sewerage or road maintenance. This was perhaps best illustrated by the interviewee from Kramfors, who said that second-home owners ‘see themselves as part of the village’ and therefore have no separate organizations for themselves. In the same vein, and in line with Robertsson and Marjavaara (Citation2015), interviewees were asked about signs of networking between locals and second-home tourists. It was only the interviewee from Jokkmokk who had any knowledge about such things taking place, but he was actively involved in trying to connect second-home owners to locals active in similar businesses.

Differing impacts of second-home tourism

Converted weekend municipalities

According to the interviewees, second homes in these municipalities were most often spread out in the rural landscape, frequently in areas with a mixed set-up of second homes and primary residences. There were no, or few, areas with only second homes, and most owners were assumed to be locals or from the near region. The current trend was a shrinking number of second homes, due to their conversion into primary residences (see also Müller & Marjavaara, Citation2012).

Persson (Citation2011, Citation2015) and Gallent (Citation2007) discuss how local communities are affected by conflicting legislation and discourse based on the notion that a second home is a different – and more or less implicitly lesser – form of dwelling than a primary residence. The converted weekend municipalities conveyed this duality, ruling out differentiation due to the Planning and Building Act (Citation2010) while at the same time restricting building sizes so much that it would be unappealing for second-home owners to begin using their houses as primary residences. Restrictions were motivated by the costs conversions could entail for the municipality in the form of infrastructure, school buses and rescue services, but also for aesthetic reasons. As in for example Overvåg and Berg (Citation2011), Paris (Citation2011) and Rye (Citation2011), land-use planning could also be a source of conflict in some cases, with a disproportionate number of appeals on building permits and land-use plans coming from second-home owners as a result (see Impacts on land-use planning and Social impacts, ).

A common theme in second-home literature is the impacts of second-home tourism on the local economy (Flognfeldt, Citation2002; Hoogendoorn & Visser, Citation2010; Larsson & Müller, Citation2017). The converted weekend municipalities experienced a positive inflow of consumers thanks to second-home tourism. Local shops and entrepreneurs were not dependent on second-home tourists, but they did provide a seasonal boon to the regular business year (see Impacts on local economy, ).

Converted vacation municipalities

These municipalities are sparsely populated, and have been affected by a sustained period of out-migration and an ageing population (Statistics Sweden, Citation2018a, Citation2018c). According to the interviewees, this meant that many buildings that had been used as primary residences were now used as second homes, often by relatives of the previous owners. Parallel to this, there was also a trend of an increasing number of purpose-built second homes in attractive locations. Although not many new houses were built in these municipalities, the absolute majority of new housing were second homes. In for example Jokkmokk, the only new housing built from the early 1990s until only recently was second homes.

Since the primary source of income for Swedish municipalities is income taxes, a diminishing and retired population has a negative effect on the public coffers. The interviewees in the converted vacation municipalities expressed a hope that second-home tourism could be used as a way to work against this trend and re-resource rural land to attract new residents and revenue (see Flognfeldt, Citation2002; Overvåg, Citation2010). This can be seen in how interviewees argued when it came to questions regarding second-home tourism’s impact on land-use planning and public services (). One interviewee put this as ‘I guess it’s a question of survival’ for small municipalities and communities, while another stated that ‘there really is no alternative’ than growth. Several means were used to achieve this end, for example investing in infrastructure and sewerage to actively pave the way for second-home development, or using legislation allowing dispensation from the national regulation protecting coastal and lake areas in order to make them available for second homes. The interviewee from Åsele said that his municipality’s attitude was quite liberal when it came to things like building permits, describing it as being ‘closer to common sense than the paragraphs’. By being accommodating and offering attractive housing opportunities, the explicit goal in these municipalities was to entice second-home owners to move there permanently. Vansbro municipality even invited second-home owners to meetings in conjunction with public events during the summer, where officials informed second-home owners about the municipality and the benefits of living there.

The effects of second-home tourism on the local economy were substantial in most converted vacation municipalities (see ). Populations grew noticeably larger during peak season, and this provided businesses opportunities for local grocery shops, carpenters, farm shops and restaurants. In places with a great concentration of second homes, businesses that would otherwise be closed for parts of the year could stay active thanks to revenues during peak season. This meant that second-home tourism not only provided business opportunities that would otherwise be lacking, but also helped maintain a level of service beyond the demand generated by the permanent population.

Purpose-built weekend municipalities

As can be seen in , these municipalities seemed to be where second-home tourism led the most anonymous existence. Typical second homes in these municipalities were purpose-built in attractive locations, such as lake or coastal areas. In Vellinge, the biggest town was an old second-home area that was slowly being converted into an area for primary residences. The number of second homes in purpose-built weekend municipalities were slowly shrinking due to their being used as primary residences instead.

Distinctions being made between second homes and primary residences in land-use planning and building restrictions were the result of old plans that were yet to be updated (and relaxed), or due to ambitions to preserve certain aesthetic qualities of certain areas. These municipalities were generally generous when it came to the size permitted for second homes, partly as a way to offer attractive housing and incite conversion into primary residences. As such, there were no restrictions on second-home areas to obstruct their being used as primary residences (see Impacts on land-use planning, ).

When it came to second-home tourism’s impact on public services, the general opinion of the interviewees in these municipalities was perhaps best captured by one planner, who said it was a ‘non-issue’ with ‘negligible’ effects on the municipal budget. The process of housing shifting use from second homes to primary residences has meant that these municipalities have had to invest in extending the public sewerage to certain new areas and assuming control over previously privately managed roads, but there were few troubling costs connected to this process (see ). In the same vein, interviewees deemed the economic effects of second-home tourism on local businesses to be negligible (see ). This rather unproblematic situation is reminiscent of second-home contexts described by Huijbens (Citation2012) and Farstad and Rye (Citation2013).

Plans for the development of the municipalities generally included tourism, but not second-home tourism. However, tourism did not seem to be a politically prioritized issue in purpose-built weekend municipalities. One interviewee stated that her municipality was not a big second-home destination, whereas a planner from Borlänge said that they ‘didn’t want to become some kind of tourism municipality’ since neighbouring municipalities were better suited for this.

Purpose-built vacation municipalities

These municipalities are mostly rural, with an ageing population and out-migration. According to the interviewees, most second-homes have been purpose-built and clustered in certain areas, but there were also instances of permanent residences being converted into second homes. As can be seen in , this is the group of municipalities most impacted by second-home tourism. The interviewee in Simrishamn spoke of a doubled population during the summer. An official in Härjedalen stated a seven- to eightfold increase in the population during peak season, while a planner in Borgholm said that her municipality worked on an estimated tenfold increase in population during summer. This extreme fluctuation in real population meant that the impacts on public services were substantial (see ). For example, these municipalities needed to have sewerage that operates at maximum capacity for only a few weeks, or even days, per year. The interviewee in Kramfors described sewerage in certain places as ‘copiously over-dimensioned’ in order to cater for the permanent residents and second-home population, while her colleague in Simrishamn said that her municipality had stopped further development of second homes in certain areas, since the sewerage would experience overload during peak season. For this reason, interviewees from these municipalities expressed a need for ways to differentiate between primary residences and second homes in relation to land-use planning, public services and housing, as discussed by, for example, Persson (Citation2011) and Gallent and Tewdwr-Jones (Citation2001). The interviewees were not entirely in agreement as to whether municipalities were already within their legal rights make such distinctions but they mentioned different solutions, for instance the possibility to have higher fees for second homes’ building permits or having rules allowing municipalities to designate certain plots of municipal land solely for primary residences when new housing is built.

In Sweden, home care for the elderly is handled by the municipalities. The Social Services Act (Citation2001) gives recipients of elderly care the right to receive home care in their second home. This is carried out and administered by the municipality where the second home is located, but is paid for and billed by the recipient’s home municipality in cases in which the primary residence and the second home are in different municipalities. Many elderly second-home owners received home care in the purpose-built vacation municipalities, which could cause a substantial increase in the administrative burden and associated costs. One interviewee from Borgholm stated that her municipality wanted regulations to be more restrictive towards, or at least more considerate of, second-home municipalities, where large numbers of elderly wanting home care can be problematic and costly. She described peak season as: ‘it always feels like mission impossible’ to arrange everything, ‘but I can relax when the summer’s over’.

An additional problem is that peak season often coincides with vacations for regular staff, which can be a problem in municipalities with a small labour force. Getting people to come from other places to work can also be a challenge, since demands on housing during peak season can be so high that temporary staff have a hard time finding somewhere to stay during the course of their contract. This is a problem that affects municipal services as well as local businesses. A planner in Borgholm said that they had about 100 restaurants, pubs and other businesses that open only for the summer; this means a great deal of temporary staff coming into the municipality and needing a place to stay.

The above example goes to show that second-home tourism are an integral part of purpose-built vacation municipalities’ local economies (see ). Carpenters and construction companies live off second-home development, maintenance and renovation. Grocery stores, restaurants, bars, artisans and artists are dependent on second-home tourism. Some of them can stay open for the entire year thanks to the income they receive during peak season, while others open temporarily. One interviewee said that this provided employment for locals as well as tourists, for example second-home owners’ children working in local tourism industry during the summer.

As in several of the other groups of municipalities in this study, second-home tourism was seen as a way to get new permanent residents. The difference in this case is that it can become a ‘politically sensitive issue’, as the interviewee from Simrishamn stated. This was mainly because the size of investments needed to meet the demand from second-home tourists is disproportionally large in relation to the permanent population. That was also the main reason that the purpose-built vacation municipalities were the only places where interviewees told about second-home tourism having political impacts (see ). For example, two interviewees mentioned very large upcoming sewerage investments in their respective municipalities, which would mean a hike in fees that might adversely affect locals’ view of second-home tourism. One interviewee said that the pros and cons of tourism continued to be a matter in the political discourse, while a planner in Kramfors stated that it was ‘better to have second homes than nothing, but better to have primary residences than second homes’. An interviewee in Härjedalen mentioned assorted problems connected to second-home tourism, but concluded by saying that these were ‘luxury problems’ compared to the stagnation in neighbouring municipalities. The situation for the purpose-built vacation municipalities is comparable to hotspots discussed by, for example, Overvåg and Berg (Citation2011); on the other hand, it seems to be less conflictual than has often been described for similar locations (e.g. Brida, Osti, & Santifaller, Citation2009; Gallent, Mace, & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2003; Paris, Citation2011).

Mixed municipalities

The mixed municipalities were highly disparate when it came to the different themes in this paper. Apart from the similarities in relation to second-home tourism discussed above, they had no clear common profile as a group. Individually, however, they were rather similar to the typical attributes of the four different second-home landscapes. Östersund, for example, was quite akin to converted weekend municipalities, while Hällefors was rather similar to the converted vacation municipalities. This could mean that the mixed or neutral position occupied by the municipalities in this group describes a position in-between the four second-home landscapes, signifying that the lines between them are blurry and not easily delineated. On the other hand, the second-home landscapes are snapshots of processes that are in motion, for example the mobility of owners and the attractiveness of an individual milieu. This could therefore mean that municipalities’ position in relation to the landscapes can change. If so, the neutral municipalities are in a position whereby different forces such as shifting housing markets, increased popularity, out-migration or increased development are driving change towards any of the second-home landscapes. Their current neutral position can therefore be interpreted as a signifier of change from one second-home landscape to another.

Temporary resident evil?

The title of this paper asks, albeit somewhat flippantly, whether the temporary resident in the form of a second-home tourist is evil. If these interviews on the impacts of second-home tourism are any indication, she is not. Rather, second-home tourism is an integral part of many local communities and economies. Although the interviews show just how heterogeneous these impacts can be, it is striking that none of the interviewees framed second-home tourism as something mainly problematic or negative, even in cases where the impacts on for example public services and land-use planning posed real challenges. In short, second-home tourism was taken for granted and any associated problems were deemed to be outweighed by its real, potential or imagined positive effects.

Judging by how the interviewees discern the impacts of second-home tourism, it is clear that the theorized second-home landscapes capture real differences. The municipalities might differ more or less from each other, but as is described above, there are patterns that reinforce the picture of four distinct second-home landscapes. But are there other variables that might explain the differences? There is no question that there is variation in how the interviewees discussed second-home tourism, depending on whether the municipalities are mainly rural or urban. There are also patterns that can be connected to whether the owners live far from their second homes and whether the municipality is located in an amenity-rich area attractive to (second-home) tourists. It is also possible to see links between sustained periods of out-migration and certain impacts of second-home tourism. These other variables alone, however, do not provide a complete picture. An analysis of second-home impacts resting on an urban-rural divide does not explain the differences between municipalities that are tourism hotspots and those that are not. Likewise, analysing the interview data from the perspective of distance, attractiveness or out-migration does not explain the variation between different municipalities. These variables are not in themselves enough to offer satisfactory explanations for the patterns in this study. The second-home landscapes, on the other hand, are based on elements of all these variables, which gives a more nuanced picture of the uneven geography of second-home tourism’s impacts on municipalities, planning authorities and local economies.

This does not mean, however, that the spatial variation of these impacts is constant over time. Fluctuations in factors such as the labour market, investments in infrastructure, trends, finance, migration and mobility can be assumed to cause long-term changes for second-home destinations. In this way, second-home tourism and accompanying impacts can change character in a given municipality over time. But changes also occur in the shorter term in the form of seasonal fluctuations. Although it is implicit in the theoretical framework of second-home landscapes, many interviewees in this study pointed to how seasonality changes second-home destinations during the course of a year. Acknowledging this spatio-temporal heterogeneity means that researchers, planners and policy-makers have to be cognizant of the context for where (and when) second-home tourism takes place.

Second-home research is often based on case studies, which makes it hard to generalize identified impacts to other second-home destinations. The results from this study contributes to the theoretical framework of second-home landscapes. This framework can be drawn upon to for further research on second homes in Sweden or elsewhere. It enables more robust selection of cases in case studies, it allows for situating research on second homes in relation to the real and anticipated impacts for a given context, to generalize or contrast results with other second-home destinations. It also makes it possible to perform hypothesis testing with regards to anticipated impacts of second-home tourism. From a policy and planning perspective, this paper argues against one-size-fits-all solutions in favour of recognizing the heterogeneous geography of second-home impacts. Knowing how places differ when it comes to the impacts of second-home tourism can be a powerful tool for planners and policy-makers, not only nationally and regionally but also locally. The theoretical framework of second-home landscapes can be applied for analysing or anticipating impacts from second-home tourism in different destinations. It can also be used for applying suitable planning or policy measures, or enabling comparisons across different planning or policy jurisdictions.

A limitation of this study is that it does not analyse how second-home tourism impacts local housing markets. Although this topic was discussed in the interviews, it has been consciously omitted to be treated separately in an upcoming paper. Therefore, it remains to be seen whether the impact of second-home tourism on housing markets follows the same patterns as those discussed here. Furthermore, this paper is based on data on detached second homes, meaning that flats and caravans used as second homes are excluded. Including such data in future studies could provide an even deeper understanding of second-home tourism and its impacts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Andreas Back http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2299-6833

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adamiak, C. (2016). Cottage sprawl: Spatial development of second homes in Bory Tucholskie, Poland. Landscape and Urban Planning, 147, 96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.11.003

- Adamiak, C., Vepsäläinen, M., Strandell, A., Hiltunen, M. J., Pitkänen, K., Hall, C. M., … Åkerlund, U. (2015). Second home tourism in Finland. (22). Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE).

- ASTRID. (2015). Data on Swedish second homes and second-home owners, for the years 1997 and 2012.

- Back, A., & Marjavaara, R. (2017). Mapping an invisible population: The uneven geography of second-home tourism. Tourism Geographies, 19(4), 595–611.

- Barnett, J. (2014). Host community perceptions of the contributions of second homes. Annals of Leisure Research, 17(1), 10–26. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2014.886156

- Blondy, C. B., Plumejeaud, C., Vacher, L., & Vye, D. (2014). Do second home owners only play a secondary role in coastal territories? A case study in Charente-Maritime (France). Tourism, Leisure and Global Change, 1, 1–14.

- Brida, J. G., Osti, L., & Santifaller, E. (2009). Second homes and the need for policy planning. TOURISMOS, 6(1), 141–163.

- Clout, H. D. (1971). Second homes in the Auvergne. Geographical Review, 61(4), 530–553.

- Dunn, K. (2016). Interviewing. In I. Hay (Ed.), Qualitative research methods in human geography (pp. 149–188). Don Mills: Oxford University Press.

- Farstad, M., & Rye, J. F. (2013). Second home owners, locals and their perspectives on rural development. Journal of Rural Studies, 30, 41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.11.007

- Flognfeldt, T. (2002). Second-home ownership: A sustainable semi-migration. In C. M. Hall & A. M. Williams (Eds.), Tourism and migration: New relationships between production and consumption (pp. 187–203). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Frykholm, K. (2017). Strategier för fritidshusturism? En översikt av Sveriges kommuner [Strategies for second-home tourism? An overview of Sweden’s municipalities]. (BA), Umeå University, Umeå.

- Gale, T. (2008). The end of tourism, or endings in tourism. In P. M. Burns, & M. Novelli (Eds.), Tourism and Mobilities (pp. 1–14). Wallingford: CABI.

- Gallent, N. (1997). Practice forum improvement grants, second homes and planning control in England and Wales: A policy review. Planning Practice & Research, 12(4), 401–410. doi: 10.1080/02697459716419

- Gallent, N. (2007). Second homes, community and a hierarchy of dwelling. Area, 39(1), 97–106.

- Gallent, N. (2014). The social value of second homes in rural communities. Housing, Theory and Society, 31(2), 174–191. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2013.830986

- Gallent, N., Mace, A., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2003). Dispelling a myth? Second homes in rural Wales. Area, 35(3), 271–284.

- Gallent, N., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2001). Second homes and the UK planning system. Planning Practice and Research, 16(1), 59–69. doi: 10.1080/02697450120049579

- Gomes, R. D. S. D. E., Pinto, H. E. D. R. S. D. C., & Almeida, C. M. B. R. D. (2017). Second home tourism in the Algarve: The perception of public managers. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo, 11(2), 197–217. doi: 10.7784/rbtur.v11i2.1246

- Hall, C. M. (2005). Tourism: Rethinking the social science of mobility. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Hall, C. M. (2015a). On the mobility of tourism mobilities. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(1), 7–10. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2014.971719

- Hall, C. M. (2015b). Second homes planning, policy and governance. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(1), 1–14. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2014.964251

- Halseth, G. (2004). The “cottage” privilege: Increasingly elite landscapes of second homes in Canada. In C. M. Hall & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground (pp. 35–54). Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Marjavaara, R. (2018). Displacement and second home tourism: A debate still relevant or time to move on? In C. M. Hall & D. K. Müller (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second home tourism and mobilities (pp. 98–111). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2004). Second homes and small-town (re)development: The case of Clarens. Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences, 32(1), 105–115.

- Hoogendoorn, G., & Visser, G. (2010). The role of second homes in local economic development in five small South African towns. Development Southern Africa, 27(4), 547–562. doi: 10.1080/0376835x.2010.508585

- Huijbens, E. H. (2012). Sustaining a village's social fabric? Sociologia Ruralis, 52(3), 332–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2012.00565.x

- Langdalen, E. (1980). Second homes in Norway: A controversial planning problem. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift [Norwegian Journal of Geography], 34, 139–144.

- Larsson, L., & Müller, D. K. (2017). Coping with second home tourism: Responses and strategies of private and public service providers in Western Sweden. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2017.1411339

- Marjavaara, R. (2008). Second home tourism: The root to displacement in Sweden? (PhD), Umeå University, Umeå.

- Müller, D. K. (2002). German second home development in Sweden. In C. M. Hall & A. M. Williams (Eds.), Tourism and migration: New relationships between production and consumption (pp. 169–185). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Müller, D. K. (2011). Second homes in rural areas: Reflections on a troubled history. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift [Norwegian Journal of Geography], 65(3), 137–143. doi: 10.1080/00291951.2011.597872

- Müller, D. K., Hall, C. M., & Keen, D. (2004). Second home tourism impact, planning and management. In C. M. Hall & D. K. Müller (Eds.), Tourism, mobility and second homes: Between elite landscape and common ground (pp. 15–32). Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

- Müller, D. K., & Marjavaara, R. (2012). From second home to primary residence: Migration towards recreational properties in Sweden 1991-2005. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 103(1), 53–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9663.2011.00674.x

- Müller, D. K., Nordin, U., & Marjavaara, R. (2010). Fritidsboendes relationer till den svenska landsbygden [Second-home dwellers’ relation to the Swedish countryside]. Retrieved from GERUM Kulturgeografisk arbetsrapport.

- Nordin, U., & Marjavaara, R. (2012). The local non-locals: Second home owners associational engagement in Sweden. Tourism, 60(3), 293–305.

- Osbaldiston, N., Picken, F., & Duffy, M. (2015). Characteristics and future intentions of second homeowners: A case study from Eastern Victoria, Australia. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(1), 62–76. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2014.934689

- Overvåg, K. (2009). Second homes in Eastern Norway: From marginal land to commodity. (PhD), Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim.

- Overvåg, K. (2010). Second homes and maximum yield in marginal land: The re-resourcing of rural land in Norway. European Urban and Regional Studies, 17(1), 3–16. doi:10.1177%2F0969776409350690

- Overvåg, K., & Berg, N. G. (2011). Second homes, rurality and contested space in Eastern Norway. Tourism Geographies, 13(3), 417–442. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2011.570778

- Paris, C. (2011). Affluence, mobility and second home ownership. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Persson, I. (2011). Fritidshuset som planeringsdilemma [The second home as a planning dilemma]. (PhD), Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona.

- Persson, I. (2015). Second homes, legal framework and planning practice according to environmental sustainability in coastal areas: The Swedish setting. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(1), 48–61. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2014.933228

- Planning and Building Act. (2010). Plan- och bygglagen [Planning and Building Act]. Retrieved from https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/plan–och-bygglag-2010900_sfs-2010-900

- Rinne, J., Paloniemi, R., Tuulentie, S., & Kietäväinen, A. (2015). Participation of second-home users in local planning and decision-making: A study of three cottage-rich locations in Finland. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(1), 98–114. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2014.909818

- Robertsson, L., & Marjavaara, R. (2015). The seasonal buzz: Knowledge transfer in a temporary setting. Tourism Planning & Development, 12(3), 251–265. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2014.947437

- Robinson, G. M. (1998). Methods and techniques in human geography. Chichester: Wiley.

- Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2011). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Rye, J. F. (2011). Conflicts and contestations: Rural populations’ perspectives on the second homes phenomenon. Journal of Rural Studies, 27(3), 263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.03.005

- Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (2006). The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 38, 207–226.

- SKL. (2017). Kommunernas åtaganden [The responsibilities of municipalities]. Retrieved from https://skl.se/tjanster/kommunerlandsting/faktakommunerochlandsting/kommunernasataganden.3683.html

- Social Services Act. (2001). Socialtjänstlagen (2001:453) [Social Services Act]. Retrieved from https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/socialtjanstlag-2001453_sfs-2001-453

- Statistics Sweden. (2014). Undersökningarna av levnadsförhållanden, semesterresande och fritidshus. Andel personer i procent efter indikator, ålder, kön och årsintervall [Surveys of living conditions, vacations and second homes. Percentage of people by indicator, age, gender and year range]. Retrieved from http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__LE__LE0101__LE0101F/LE0101F01/?rxid=8e3464cf-d8c9-4774-8235-69a5d292176c

- Statistics Sweden. (2018a). Befolkningens medelålder efter region och kön. År 1998-2017 [The population's average age by region and sex. Year 1998-2017]. Retrieved from http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101B/BefolkningMedelAlder

- Statistics Sweden. (2018b). Folkmängden efter region, civilstånd, ålder och kön. År 1968–2017 [Population by region, marital status, age and sex. Year 1968-2017]. Retrieved from http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101A/BefolkningNy/?rxid=f5790986-ce9d-4cdc-9658-fbc9c700b7ef

- Statistics Sweden. (2018c). Kommuner i siffror [Municipalities in numbers]. Retrieved from https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/kommuner-i-siffror/

- Swedish Tax Agency. (2015). Kommunal fastighetsavgift kalenderåren 2008–2016 [Municipal property fee for years 2008-2016]. Retrieved from https://www.skatteverket.se/download/18.5a85666214dbad743ff17283/1443419155035/Kommunal+fastighetsavgift+kalender%C3%A5ren+2008-2016_Version+1.0_2015-09-28.pdf

- Urry, J. (2007). Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity Press.