ABSTRACT

The six Western Balkan economies are facing similar challenges and opportunities in upgrading their tourism sectors. Currently, all six economies are preparing the design and implementation of smart specialization strategies, thus adapting an approach known from EU cohesion policy to their needs. Montenegro is the first country in the Western Balkans to have drafted its strategy, and health tourism is part of the priorities defined. Based on the theoretical perspectives of self-discovery, related variety, tourism innovation and sustainability, the article analyzes the role of tourism in Montenegro's smart specialization strategy and draws conclusions for other Western Balkan economies on how to seize the opportunities of the smart specialization approach in developing tourism in a cross-sectoral way.

JEL CODES:

Introduction

In 2018, the European Commission reaffirmed the EU accession perspective for Western Balkan economies (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, KosovoFootnote1, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia). Thus, the Western Balkans are confronted with the challenge of gradually aligning their economies and policies with EU standards (European Commission, Citation2018).

In this alignment processes, improving the competitiveness of key sectors will be critical (OECD, Citation2018). While there are a number of manufacturing sectors that afford Western Balkan economies growth opportunities such as the agri-food, metal processing, automotive, or machinery industries (OECD, Citation2019), the potential of service industries should not be neglected. Given the proximity to major European markets and the secular growth of tourism, it is plausible to assume that the tourism sector could be another key sector to drive the Western Balkans’ catching-up process.

The policy frameworks Western Balkan economies are adopting in the process of EU alignment offer an opportunity to promote their tourism sectors. In particular, the smart specialization approach that is currently introduced in the Western Balkans provides such an opportunity. Including tourism as a priority in smart specialization strategies can serve to tackle the current challenges of tourism development, and to link tourism with other key sectors. This argument is well illustrated in the case of Montenegro, the first Western Balkan country to have adopted a smart specialization strategy (S3).

This article pursues the aim of placing tourism into the wider logic of economic diversification to be promoted under the smart specialization approach. The article presents conceptual arguments on the role of tourism in smart specialization, building on a document analysis of policy documents from Montenegro in light of the literature on self-discovery, related variety, tourism innovation, and sustainability. The article argues that the collective, public-private smart specialization process can serve to promote tourism in a perspective of related variety.

Theoretical perspectives: self-discovery, related variety, tourism innovation, sustainability

In recent years, the smart specialization approach has been widely used in EU cohesion policy, driven by the ex-ante conditionality for countries or regions to develop smart specialization strategies (Radosevic, Citation2017). The approach stipulates that policy should focus its attention and funds on a limited set of priorities that can generate growth through diversification, and that the resulting cross-sectoral S3 should be based on evidence and developed jointly by policymakers, the private sector and academia in a participatory process called entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP) (Foray, David, & Hall, Citation2009; Foray et al., Citation2012; McCann & Ortega-Argilés, Citation2015).

The EDP is supposed to be based on evidence such as qualitative and quantitative analysis, and to lead to the joint prioritization of activities and measures by agents involved in formats such as interviews, focus groups, or conferences (e.g. Foray et al., Citation2012; Matusiak & Kleibrink, Citation2018). The EDP goes back to the idea of self-discovery (Hausmann & Rodrik, Citation2003) emanating from the debate on new industrial policies (Martínez-López & Palazuelos-Martínez, Citation2015, p. 5) and from the general trend to develop economic development strategies in public-private partnership.

Since tourism is an important industry for a number of countries and promoting it fits well into a cross-sectoral logic, smart specialization is a relevant policy framework for tourism (Benner, Citation2017; Del Vecchio & Passiante, Citation2017; Weidenfeld, Citation2018). In particular, smart specialization focuses on diversification across different kinds of knowledge bases and supporting cross-sectoral platform policies (Asheim, Boschma, & Cooke, Citation2011) and is thus relevant for tourism diversification (Weidenfeld, Citation2018). As a platform policy, S3 can serve to promote economic growth along related variety (Boschma & Iammarino, Citation2009; Frenken, Van Oort, & Verburg, Citation2007), i.e. diversification into related sectors based on similar knowledge. In the case of tourism, related variety can mean, for instance, diversification into agri-tourism, wine tourism, or health tourism.

As innovation can be thought of as a major driver of related variety, S3 can serve as a vehicle to promote tourism innovation, taking into account the specificities of innovation in the tourism sector (Hjalager, Citation2010; Hjalager & Jezic von Gesseneck, Citation2019; Narduzzo & Volo, Citation2018; Williams & Shaw, Citation2011). While tourism innovation policies can, in theory, be implemented in a top-down or bottom-up way (Rodríguez, Williams, & Hall, Citation2014) and either focus on the tourism sector specifically or address innovation horizontally (Hjalager, Citation2010, p. 8), S3 offer an opportunity to reconcile these different orientations. They can do so first through self-discovery in the EDP that aligns bottom-up knowledge with top-down funding, and second by promoting innovation not only within the tourism sector but in a cross-sectoral way along related variety.

Further, promoting the tourism sector under smart specialization will have to consider aspects of tourism sustainability. While sustainable tourism is a vague term subject to a wide-ranging debate (Cohen, Citation2002; Hunter, Citation1997; Saarinen, Citation2014), as is the related concept of carrying capacity (Lindberg, McCool, & Stankey, Citation1997; McCool & Lime, Citation2001; O'Reilly, Citation1986), it is clear that focusing on purely quantitative growth of tourist arrivals or overnight stays is not a long-term option (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2018). Developing innovative and high value-added niches of tourism then becomes a major task of policymakers (Benner, Citation2019) that can be addressed in an EDP.

Tourism in the Western Balkans

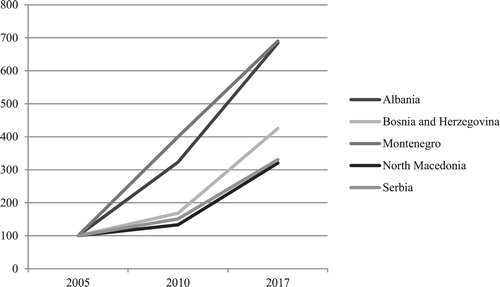

Western Balkan economies are not among the world's primary tourist destinations and even in comparison to their neighbours are dwarfed by Croatia's almost 15.6 million non-resident tourist arrivals in 2017 (UN Data, Citation2019). Still, as shows, given their small sized the five countries for which data is available attract sizeable numbers of tourists. Each of these five countries witnessed strong growth in inbound tourist arrivals with Montenegro and Albania showing the strongest growth between 2005 and 2017, as illustrates. This growth may be driven in part by the emergence of low-cost carriers and the affordability of Western Balkans destinations (OECD, Citation2018, p. 592). While Albania is the tourism champion among Western Balkan economies, between 2010 and 2017 tourist arrivals grew most rapidly in Bosnia and Herzegovina at a rate of almost 153 percent (UN Data, Citation2019).

Figure 1. Growth of non-resident tourist arrivals in the Western Balkans (2005 = 100). (Source: authors’ elaboration based on ‘Arrivals of non resident tourists/visitors, departures and tourism expenditure in the country and in other countries’ from UN Data / World Tourism Organization; UN Data, Citation2019).

Table 1. Non-resident tourist arrivals in the Western Balkans (thousands).

According to the OECD (Citation2018), all Western Balkan economies have put tourism development strategies in place and focus on developing their product and on branding the destination in segments such as cultural tourism, adventure tourism, or mountain tourism. However, remaining challenges include strengthening tourism-specific technical and vocational education and training, upgrading the quality of accommodation, congress and spa facilities, overcoming seasonality, addressing institutional constraints that lower the quality of the tourism product (Lehmann & Gronau, Citation2019), achieving a cross-sectoral approach to tourism development that spans different government ministries and agencies and different spatial levels, and consultation with civil society. Since the cost-based attractiveness of the Western Balkans as tourist destinations will be hard to sustain, these challenges will have to be addressed (OECD, Citation2018, pp. 585–624; World Bank, Citation2017, pp. 35–37).

The potential of the tourism sector for Western Balkan economies is underpinned by their assets in terms of cultural and natural heritage that position them as attractive destinations for nature and cultural tourism (Metodijeski & Temelkov, Citation2014, pp. 237–238; OECD, Citation2018, pp. 588–589; Seidl, Citation2014). The current introduction of the smart specialization approach to the region could provide an opportunity to tackle the challenges for tourism development and to build on these assets, as the case of Montenegro illustrates.

The case of Montenegro

Although non-EU countries are not subject to the ex-ante conditionality for cohesion policy, Western Balkan economies are currently introducing smart specialization as a way to facilitate economic growth and to align policy priorities across sectors with support from the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (Matusiak & Kleibrink, Citation2018). Given that the current challenges to tourism development include the need to upgrade tourism infrastructure and to enhance public-private cooperation (OECD, Citation2018, pp. 585–624), introducing smart specialization to the Western Balkans provides an opportunity to tackle them, and the case of Montenegro offers an example of how to do so in a cross-sectoral perspective based on related variety.

Montenegro has a tourism strategy that covers the period until 2020. The strategy aims at positioning Montenegro as a high-quality destination and defines measures such as upgrading accommodation infrastructure, raising service quality, diversifying the offer through nautical tourism, mountain tourism, golf tourism, congress tourism, agri-tourism, wellness tourism, camping, cultural/religious tourism, and national parks, and linking tourism with other industries (Ministry of Tourism and Environment, Citation2008).

The introduction of smart specialization to Montenegro included a detailed quantitative and qualitative analysis of the economy that confirmed the importance of the hospitality and tourism industry and identified it as a promising sector together with agriculture, energy, information and communication technologies (ICT), manufacturing, medicine/health, and construction (Ministry of Science, Citation2019a).

During the EDP, the field of sustainable and health tourism was addressed and a sectoral vision and goals were formulated. Segments targeted are largely consistent with the tourism strategy but put a stronger focus on health. These segments include nautical tourism, congress tourism, adventure tourism, speleological tourism, oncology, prevention, palliative care, medicinal and aromatic herbs, nutritionism, and medical services. Tourism thus provides an example for the cross-sectoral logic of the smart specialization approach (Ministry of Science, Citation2018).

The S3 reflects the results of the EDP and defines sustainable and health tourism as a priority. This priority aims at seizing the potential of Montenegro's medical, ICT, and tourism industries and relates to the regional initiative of establishing a South East European International Institute for Sustainable Technologies for cancer therapy and biomedical research. While the strategy does not explicitly define the notion of sustainable tourism and the description of the sustainable and health tourism field refers to more generic tourism-related assets such as cultural, religious and natural heritage, the focus is clearly on health tourism. For instance, the strategy calls for the modernization of the Adriatic centre for bone and muscular system diseases with the aim of making it an international hub for treatments, rehabilitation and prevention. Health tourism is seen as a driver to develop a ‘diversified and authentic tourism offer’ (Ministry of Science, Citation2019b, p. 69). The strategy emphasizes the use of new technologies in nautical tourism, therapies for chronic diseases and dental treatments, and rehabilitation programmes as focus areas. Inter alia, sports and wellness tourism are seen as fields with potential, as are nutritionism and aromatic herbs. However, remaining challenges stated in the strategy include seasonality and gaps in the accommodation and transport infrastructure (Ministry of Science, Citation2019b, pp. 67–71).

The cross-sectoral character evident in the link between tourism and the health industry but also the agri-food sector in the Montenegrin strategy is consistent with the theoretical perspective of related variety. Hence, Montenegro's S3 provides an example for linking tourism with other priorities. The fact that this cross-sectoral logic was laid out during the EDP (Ministry of Science, Citation2018) hints at the use of a self-discovery process in promoting related variety through tourism. Whether Montenegro's strategy will contribute to promoting tourism innovation and to developing sustainable forms of tourism will need to be seen upon implementation.

Conclusions and further research

Smart specialization offers opportunities for Western Balkan economies to modernize their tourism development strategies, to link tourism with other sectors in a perspective of related variety, and to promote tourism innovation and sustainability. Montenegro's example in particular illustrates the cross-sectoral logic that developed in self-discovery during the EDP. While other Western Balkan economies may benefit from Montenegro's experience, each one will have to find its own niches and to develop its tourism sector according to its specific assets and opportunities.

Given the cultural and natural assets of the Western Balkans, ensuring the sustainability of tourism development will be important. If the strong growth of tourist arrivals the region witnessed in recent years were to continue over the long run, problems of overtourism such as those known from Croatia's Dubrovnik (e.g. Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2018; Panayiotopoulos & Pisano, Citation2019) could become acute. Managing tourism development carefully and with a long-term focus on careful diversification and linkage with other innovative sectors of the economy is therefore necessary, and smart specialization might offer an opportunity to develop such a focus in public-private cooperation. When implementing their S3, Montenegro’s policymakers and stakeholders will need to focus on such a careful and sustainable approach, and further research along a research agenda addressing organizational, institutional, and behavioral questions (Benner, Citation2019) will be useful to accompany this process and to evaluate the results.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Dimitrios Kyriakou, Monika Matusiak and Nikola Radovanovic for comments or suggestions. Of course, all remaining errors are the author’s.

Disclosure statement

The author is involved in the Joint Research Centre’s support activities for smart specialization in the Western Balkans.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

References

- Asheim, B. T., Boschma, R., & Cooke, P. (2011). Constructing regional advantage: Platform policies based on related variety and differentiated knowledge bases. Regional Studies, 45(7), 893–904. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2010.543126

- Benner, M. (2017). From clusters to smart specialization: Tourism in institution-sensitive regional development policies. Economies, 5, 26. doi: 10.3390/economies5030026

- Benner, M. (2019). Overcoming overtourism in Europe: Towards an institutional-behavioral research agenda. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie. doi:10.1515/zfw-2019-0016.

- Boschma, R., & Iammarino, S. (2009). Related variety, trade linkages, and regional growth in Italy. Economic Geography, 85(3), 289–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01034.x

- Cohen, E. (2002). Authenticity, equity and sustainability in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(4), 267–276. doi: 10.1080/09669580208667167

- Del Vecchio, P., & Passiante, G. (2017). Is tourism a driver for smart specialization? Evidence from Apulia, an Italian region with a tourism vocation. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(3), 163–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.09.005

- European Commission. (2018). A credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/communication-credible-enlargement-perspective-western-balkans_en.pdf

- Foray, D., David, P. A., & Hall, B. (2009). Smart specialisation - the concept. Knowledge Economists Policy Brief, 9.

- Foray, D., Goddard, J., Goenaga Beldarrain, X., Landabaso, M., McCann, P., Morgan, K., … Ortega-Argilés, R. (2012). Guide to research and innovation strategies for smart specialisation (RIS 3). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the EU.

- Frenken, K., Van Oort, F., & Verburg, T. (2007). Related variety, unrelated variety and regional economic growth. Regional Studies, 41(5), 685–697. doi: 10.1080/00343400601120296

- Hausmann, R., & Rodrik, D. (2003). Economic development as self-discovery. Journal of Development Economics, 72(2), 603–633. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00124-X

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2018). Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.017

- Hjalager, A. M. (2010). A review of innovation research in tourism. Tourism Management, 31(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.08.012

- Hjalager, A. M., & Jezic von Gesseneck, M. (2019). Capacity-, system-and mission-oriented innovation policies in tourism – characteristics, measurement and prospects. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events. doi:10.1080/19407963.2019.1605609.

- Hunter, C. (1997). Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(4), 850–867. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00036-4

- Lehmann, T., & Gronau, W. (2019). Tourism development in transition economies of the western Balkans – Addressing the seeming oxzmoron of institutional voids and tourism growth. Zeitschrift für Tourismuswirtschaft, 11(1), 45–64.

- Lindberg, K., McCool, S., & Stankey, G. (1997). Rethinking carrying capacity. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 461–465. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(97)80018-7

- Martínez-López, D., & Palazuelos-Martínez, M. (2015). Breaking with the past in smart specialisation: A new model of selection of business stakeholders within the entrepreneurial process of discovery. Journal of Knowledge Economy, 6, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s13132-014-0234-3

- Matusiak, M., & Kleibrink, A. (Eds.). (2018). Supporting an innovation agenda for the Western Balkans: Tools and methodologies. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the EU.

- McCann, P., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2015). Smart specialization, regional growth and applications to European Union cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1291–1302. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2013.799769

- McCool, S. F., & Lime, D. W. (2001). Tourism carrying capacity: Tempting fantasy or useful reality? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 9(5), 372–388. doi: 10.1080/09669580108667409

- Metodijeski, D., & Temelkov, Z. (2014). Tourism policy of Balkan countries: Review of national tourism development strategies. UTMS Journal of Economics, 5, 231–239. doi: 10.1080/09765239.2014.11884999

- Ministry of Science. (2018). Sustainable and health tourism: Results of entrepreneurial discovery process. Retrieved from http://www.mna.gov.me/ResourceManager/FileDownload.aspx?rid=330698&rType=2&file=Sustainable%20and%20Health%20Tourism_Final%20EDP%20Conference_18%20September%202018.pdf

- Ministry of Science. (2019a). Quantitative and qualitative analysis: Mapping economic, innovation and scientific potential in Montenegro. Retrieved from http://www.mna.gov.me/ResourceManager/FileDownload.aspx?rid=375203&rType=2&file=Quantitative%20&%20Qualitative%20Analysis%20S3.me.pdf

- Ministry of Science. (2019b). Smart specialisation strategy of Montenegro 2019-2024. Retrieved from http://www.mna.gov.me/ResourceManager/FileDownload.aspx?rid=375205&rType=2&file=Smart%20Specialisation%20Strategy%20of%20Montenegro%202019-2024.pdf

- Ministry of Tourism and Environment. (2008). Montenegro tourism development strategy to 2020. Retrieved from http://www.mrt.gov.me/ResourceManager/FileDownload.aspx?rid=89273&rType=2&file=01%20Montenegro%20Tourism%20Development%20Strategy%20To%202020.pdf

- Narduzzo, A., & Volo, S. (2018). Tourism innovation: When interdependencies matter. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(7), 735–741. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2016.1214111

- O'Reilly, A. M. (1986). Tourism carrying capacity: Concept and issues. Tourism Management, 7(4), 254–258. doi: 10.1016/0261-5177(86)90035-X

- OECD. (2018). Competitiveness in South East Europe: A policy outlook. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- OECD. (2019). Unleashing the transformation potential for growth in the Western Balkans. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Panayiotopoulos, A., & Pisano, C. (2019). Overtourism dystopias and socialist utopias: Towards an urban armature for Dubrovnik. Tourism Planning & Development. doi:10.1080/21568316.2019.1569123.

- Radosevic, S. (2017). Assessing EU smart specialization policy in a comparative perspective. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorgiu, L. Andreescu, & I. Wage (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 2–37). London: Elsevier.

- Rodríguez, I., Williams, A. M., & Hall, C. M. (2014). Tourism innovation policy: Implementation and outcomes. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 76–93. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2014.08.004

- Saarinen, J. (2014). Critical sustainability: Setting the limits to growth and responsibility in tourism. Sustainability, 6, 1–17. doi: 10.3390/su6010001

- Seidl, A. (2014). Cultural ecosystem services and economic development: World Heritage and early efforts at tourism in Albania. Ecosystem Services, 10, 164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.08.006

- UN Data. (2019). Arrivals of non resident tourists/visitors, departures and tourism expenditure in the country and in other countries. New York: United Nations Statistics Division. Source: World Tourism Organization. Retrieved from http://data.un.org/DocumentData.aspx?q=tourism&id=401

- Weidenfeld, A. (2018). Tourism diversification and its implications for smart specialisation. Sustainability, 10, 319. doi: 10.3390/su10020319

- Williams, A. M., & Shaw, G. (2011). Internationalization and innovation in tourism. Annals in Tourism Research, 38(1), 27–51. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2010.09.006

- World Bank. (2017). Montenegro: Policy notes 2017. Washington: The World Bank.