ABSTRACT

Tourism is facing an unprecedented crisis whose sheer scope is dictating global transformation of the industry. The aim of this paper is to explore how different countries and destinations responded to the initial blow of the COVID-19 pandemic, and what is expected in the recovery and restart phases. A crisis management model was developed using data from 31 interviews with tourism organizations. The findings help identify the actions required to build resilience, emphasizing the responsibilities and interventions that can achieve tourism restoration. We point out implications for theory and practice in terms of incorporating policymakers’ perceptions, while also informing tourism organizations about policy development and the reformulation of strategies. This might support countries and destinations choosing the right path in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, addressing the negative and taking advantage of the positive repercussions.

Introduction

According to the UNWTO (Citation2020), tourism is expected to be one of the industries most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Travel restrictions, quarantines, social distancing, and stay-at-home orders led to a global tourism halt at the end of March 2020 (Gössling et al., Citation2020). Policies and measures were implemented in most countries to lessen the impact of COVID-19 on social, cultural, and economic realms (UNWTO, Citation2020). While the current devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are unquestionable, the coming mid- and long-term consequences remain to be seen (UNWTO, Citation2020).

Social life in general is predicted to change, with shifting patterns in consumption, leisure and work life, mobility, as well as socialization (Romagosa, Citation2020). Individual lifestyles will modify as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, with changing cultures, values, and traditions (Wen et al., Citation2021). Tourists’ behavioural change (Bae & Chang, Citation2020) will impact the entire tourism industry (Romagosa, Citation2020; Wen et al., Citation2021). Travel risk perceptions already increased due to a large number of COVID-19 cases, wide media coverage and travel restrictions, which changed travel behaviours and pushed many tourists to cancel their travel plans and to avoid travelling (Neuburger & Egger, Citation2020). Recently, Bhati et al. (Citation2020) explored the effect of health-related destination images on travel intention of tourists, finding that health-protective behaviour and media engagement serve as mediators. Managing travel risk perception and destination image with the help of media and health-protective actions to facilitate travel intentions will therefore be more important than ever (Bhati et al., Citation2020). In spite of a lack of valid and significant predictions for the tourism industry, a consensus does exist that tourism will change in the future (Romagosa, Citation2020). Particularly the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic makes it likely that the tourism industry will experience long-term structural changes (Sigala, Citation2020).

A number of studies in tourism research have investigated crisis management as a means to enhance resilience in tourism (Filimonau & De Coteau, Citation2020; Lew, Citation2014; Prayag, Citation2018). However, the current COVID-19 pandemic is perceived as having more far-reaching consequences than previous crises (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020), making an investigation of crisis management for this specific pandemic a necessity.

Furthermore, less attention has been paid to the role and impact of tourism organizations in crises (Sigala, Citation2020). Although past studies have indeed produced institutional interest, earlier crises did not have extensive tourism policy impacts (Hall et al., Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in destination management organizations’ (DMO) and policymakers’ interventions in the tourism industry, for instance by providing stimulus payments to the tourism industry, or by restricting mobility and ordering business closures (Sigala, Citation2020). In this regard, Higgins-Desbiolles (Citation2020) questioned the effectiveness, fairness, and equal distribution of interventions, requiring research on DMOs’ and policymakers’ interventions during the crisis to help shed light on the political issues emerging as part of it (Sigala, Citation2020). Thus, this research explored the reactions and responses of tourism organizations across the globe to the COVID-19 pandemic by discussing implemented and intended policies in the initial phase of the pandemic. We examined the differences in responses, identifying the prevailing policies and strategies found during the pandemic. Qualitative interviews with tourism organizations were carried out to discover their individual crisis management approaches. In addition, the interviews were intended to show tourism organizations' perception of responsibility in the crisis by means of an in-depth understanding of the interventions of governments and destinations (Sigala, Citation2020). Two research questions were posed.

How have tourism organizations responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of crisis management?

How do they perceive current and future tourism policies for tourism restoration?

Crisis management in tourism

The tourism industry has been affected in recent years by an increasing number of crises and disasters (Aliperti et al., Citation2019; Prayag, Citation2018). When it comes to the lasting influences of these phenomena on communities, nations, businesses, and individuals, also due to indirect losses for entire economies, appropriate crisis management plans need to be implemented to impose suitable changes (Aliperti et al., Citation2019; Lew, Citation2014; Prayag, Citation2020). Although there are arguments about the tourism sector’s knowledge regarding crisis management (Prayag, Citation2018; Romagosa, Citation2020), the current COVID-19 pandemic is perceived as a crisis of unprecedented magnitude, particularly in light of its global impacts (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020).

Blake and Sinclair (Citation2003) state that the issues in crisis management include the severity of the decrease in tourism activity, the duration of the crisis which steers policymakers into adaptation to the situation or minimization of costs, the assessment of the possible responses from stakeholders, and the implementation of proper tourism policies. Ritchie (Citation2004) believes that a strategic proactive approach is needed in tourism crisis management, which includes proactive scanning and planning, implementing strategies when crises happen and evaluating the strategies regarding their effectiveness. Up-to-date statistics, effective communication between government departments, and transparency are crucial for proactive management when defending the tourism sector (de Sausmarez, Citation2007). Thus, it is widely endorsed in tourism research that crisis management needs action before, during, and after a crisis (Sigala, Citation2020). Faulkner’s (Citation2001) tourism disaster management framework is comprised of six phases: pre-event when potential disaster can be prevented; prodromal when the disaster is imminent; emergency when the disaster is felt; intermediate when people’s needs have been met and restoration take place; long-term (recovery) when the healing continues and additional longer-term activities are addressed; and resolution when the daily routine is restored. Sigala (Citation2020) categorizes the crisis management phases into respond, recovery and restart stages in order to integrate a transformational stage in the post phase, whereby different strategies can be pursued in the respond and recovery phase.

Crisis management knowledge is perceived as enhancing defence mechanisms, limiting potential damages, and returning back faster to normality after a crisis. In this vein, procedural knowledge relates to particular crisis management plans as explicit knowledge, and behavioural knowledge generated from formal crisis knowledge (Paraskevas et al., Citation2013).

Building resilience as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic

However, it’s also argued that crisis management doesn’t work, requires too much time, or provides only minimal learning outcomes (Prayag, Citation2018). This in turn makes it necessary to move beyond disaster and crisis management (Prayag, Citation2018) towards resilience, which emphasizes systems evolving, responding, and adapting to and from change processes, including learning from extraordinary circumstances (Lew, Citation2014). Therefore, resilience addresses the insufficiencies of crisis management in advancing and informing knowledge (Prayag, Citation2018), noting how resilience offers a ‘glimpse of recovery responses’ (Ioannides & Gyimóthy, Citation2020, p. 628). It incorporates an integrative and inclusive social ecological systems approach via an acknowledgement of the possible influences of multiple contexts for adaption (Espiner et al., Citation2017). In addition, resilience is regarded as capturing various core aspects of sustainable development (Espiner et al., Citation2017). McCool (Citation2015) considers sustainability to be a strategy for building and maintaining resilience, thus regarding sustainable tourism development as a requirement for resilience. It is argued that tourism planning needs to shift the focus of the preservation of an unchanging state to an inevitable change responsiveness (Farrell & Twining-Ward, Citation2004), emphasizing and encouraging a resilience approach to tourism development and planning (Espiner et al., Citation2017). Sharma et al. (Citation2021) demonstrate that the development of resilience can transform tourism into a more sustainable industry that focuses on well-being, community engagement, and climate action.

The destination level is considered an appropriate application level for the resilience concept due to stakeholders’ involvement, the heterogeneity of supply, and the wide range of resources in the tourism industry (Amore et al., Citation2018). Considering this, community-oriented destinations are perceived to accentuate social structures, stakeholder relations, as well as community involvement (Flagestad & Hope, Citation2001). Basing their argument on tourism systems, Jamaliah and Powell (Citation2018) signify the four dimensions of social, governance, environmental, and economic resilience. Social resilience relates to the capacity for coping with disturbances and stresses triggered by change (Adger, Citation2000). The economic flexibility and economic capacity relate to economic resilience, while the environmental resilience dimension emphasizes natural resource protection (Dai et al., Citation2019). The governance resilience dimension consists of policy and law, with institutional arrangements and various regulations (Amore et al., Citation2018); this addresses the ability of governmental and non-governmental institutions to provide effective change responses (Jamaliah & Powell, Citation2018). In light of the COVID-19 pandemic and in order to develop resilience in tourism, Sharma et al. (Citation2021) argue that all stakeholders of the tourism value chain need to join forces. In particular, governments, market operators, as well as local communities are responsible for building resilience (Sharma et al., Citation2021).

According to Ioannides and Gyimóthy (Citation2020), governmental policies and interventions are required to strengthen and further develop resilience in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sigala (Citation2020) considers governmental interventions as ‘economic support (e.g. subsidies, tax reliefs) to tourism business and employees’ (p. 313), while Sharma et al. (Citation2021) plead for governmental stimulus packages and interventions. For Higgins-Desbiolles (Citation2020), however, tourism businesses are just about always eager to return back to ‘normal’ by accepting governmental interventions and stimulus packages, leading to questions regarding their fairness, effectiveness, and distribution. In addition, it remains unclear which policies can create a shift towards more sustainable directions. Thus, the responses and reactions of tourism organizations, which receive and provide stimuli and assistance in the form of e.g. payment deferrals, tax relief, and subsidies should be investigated. In this vein, a research gap regarding governmental behavioural impacts on tourism policymaking and strategy development exists (Sigala, Citation2020). Our paper addresses this gap by extending the focus of the resilience concept to include crisis management that is applied to intended and implemented policies, policymaking, and interventions which focus on building resilience in an effort to recover from the pandemic.

Method

Research design

Research on crisis and disaster management in tourism has predominantly focused on qualitative research that uses semi-structured interviews and secondary data analysis. Quantitative research has relied strongly on experiments, scenario designs, and questionnaires (Ritchie & Jiang, Citation2019). However, as the current pandemic is a crisis of a larger scale (Prayag, Citation2020), further qualitative research is needed to provide in-depth insight into its management.

Thus, we built on a qualitative research design (Flick, Citation2015) to explore the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism organizatons. The aim was to discuss destinations’ resilience and crisis management to obtain a better understanding regarding their feasibility and adaptability to cope with the crisis. Interviews are the most widely employed method in qualitative research (Bryman, Citation2012), which Kvale (Citation1983) describes with the aim to collect ‘descriptions of the life-world of the interviewee with respect to interpretation of the meaning of the described phenomena’ (Kvale, Citation1983, p. 174). Contrary to quantitative research, where the survey reflects the researchers’ concerns, in qualitative interviews, the main interest is the opinion of the interviewee (Bryman, Citation2012). Thus, semi-structured interviews were conducted because they enabled the researchers to obtain factual information while leaving them free to probe deeper into the interviewees’ experiences (Halperin & Heath, Citation2017). This provided the researchers with more flexible opportunities to explore the topic of crisis management and resilience in tourism.

The interview guideline was constructed in a way that guided the researchers in answering the research questions. Thus, the interview questions were based on previous literature, addressing key topics around policymaking, resilience, and crisis management. The interview guideline was divided into three main parts. In line with crisis management strategies, analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats can help countries and destinations to evaluate crisis impacts and develop contingency plans for reducing negative effects (Tse, Citation2006). Thus, for instance the question ‘Which opportunities and threats do you identify for your destination during the COVID-19 crisis?’ was asked. The next part of the interview guideline was concerned with existing and new policies to cope with the pandemic. Previous crises have not had such an impact on tourism policy, so very few destinations and countries have had any crisis-related policies in place prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Hall et al., Citation2020). Immediately after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, most destinations and countries implemented numerous tourism policies (Sigala, Citation2020; UNWTO, Citation2020). Regarding this, questions like ‘Are the existing policies at your destination adequate for coping with the COVID-19 crisis?’ and ‘Which are newly implemented tourism policies at your destination for coping with the COVID-19 crisis?’ were asked. The last part was focused on the roles of the stakeholders. In emergency situations, stakeholder involvement and collaboration are crucial (Amore et al., Citation2018; Blake & Sinclair, Citation2003). Therefore, questions like ‘How do tourism stakeholders cooperate during the COVID-19 pandemic?’ and ‘How will tourism stakeholders cooperate after the COVID-19 pandemic?’ were posed.

This study targeted DMOs, national tourist boards (NTO), and tourism policymakers. Purposive sampling was employed to recruit participants for the interviews due to the study’s unique context (Miles et al., Citation2014). According to Babbie (Citation2008), purposive methods are useful when a study needs to ‘select a sample on the basis of knowledge of a population, its elements and the purpose of the study’ (Babbie, Citation2008, p. 204). Respondents were either reached personally by phone, or by email to confirm their willingness to take part in the study.

31 interviews were conducted (see ) in April 2020. The interviews were conducted in English with managers of tourism organizations of different countries and destinations around the globe. The majority of the interviews were conducted via Skype and Zoom. At the specific request of some organizations, a few of the interviews were done via email.

Table 1. Sample overview.

Data analysis

Following the template analysis approach (Crabtree & Miller, Citation1992; King, Citation2017), the interviews conducted were transcribed, coded, and examined with the qualitative data analysis software MAXQDA. Here, a priori codes within the construction of an initial coding template were developed, followed by a revision with inductive codes, thus representing a flexible but structured data analysis approach (King et al., Citation2019). The data analyses pursued to understand the different phases of crisis management and resilience based on the tourism organizations’ perceptions, as well as the template emphasized the different key determinants within the divergent phases. illustrates the final coding template with its respective categories, codes, and exemplary quotes.

Table 2. Coding template.

Results

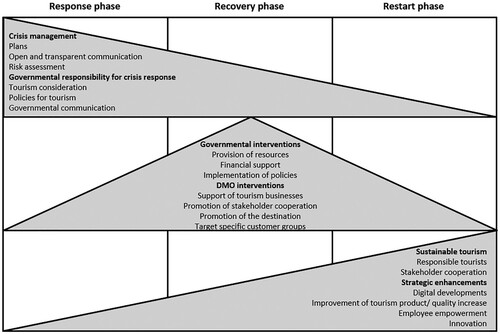

The results are structured in three crisis phases, elaborating on actions that prevail in each of these phases. The actions in the response stage are part of the crisis management and governmental responsibility for crisis response. In the recovery phase, governmental and DMO interventions are crucial. In the restart phase, sustainable tourism development and strategic enhancements are emphasized. Further, as the three phases contribute to build resilience, illustrates the proportion of perceived importance of the above stated measures for destination resilience, allocated to each of the phases (response/recovery/restart). The respective measures in the different phases are described in detail below.

Response phase

At first, interviewees described the response phase with the importance of crisis management approaches and governments’ responsibility to respond to the crisis.

Crisis management

Thus, crisis management was discussed in the interviews within the context of existing crisis plans or precautions for the crises’ response stage. The interviewees showed that, although plans for crises do exist, neither the nature of the crisis nor its extent were considered in the crisis plans. Still others have made no plans for crises whatsoever, as seen in the interview:

There was no previously made plan for managing a crisis, all measures are taken at the moment and depend on the development of the situation, which changes all the time. (Interview 21)

In addition, in order to identify and assess the crisis risks, the interviewees addressed the temporarily prevailing regulations such as travel restrictions, closures, and hygiene guidelines. These had reduced tourism to a minimum, or even brought a complete stop. Here the interviewees mentioned the strengths and weaknesses associated with the pandemic. Financial reserves, nature-based tourism, and a broad-based target group were seen as strengths/opportunities for the interviewees, while a weak health care system, limited infrastructure, and a poorly differentiated economy represented the weaknesses of destinations in the current pandemic.

I think the main weakness is the structure of the mono industry. With gambling and tourism, in this case when the businesses are closed, the whole economy is negatively and severely affected. It is very risky to have tourism as a pillar industry. (Interview 15)

Governmental responsibility for crisis response

Moreover, within the response phase, the interviewees considered the government as having a duty to respond to and manage the crisis:

The main responsible institution is the government. Local mayors of the city can intervene, but 90% of the responsibility lies on the government. (Interview 13)

As I have already mentioned, there is a crisis management team working directly under the leadership of the Prime Minister. The team is gathered from experts working in ministries, committees and other state organizations to ensure quick communication of the policies to the responsible entities. (Interview 23)

Recovery phase

Corresponding to the recovery phase, the interviewees addressed certain responsibilities to help tourism recover, emphasizing the responsibility of the government and DMOs to provide assistance. On the one hand, according to the interviewees, governmental interventions were required for the provision of resources, as well as financial support and implementations of policies were needed in order to contribute to tourism recovery. On the other hand, DMO interventions took form in support of tourism businesses, promotion of stakeholder cooperation, promotion of the destination and attraction of specific customer groups.

Governmental interventions

The interviewees requested the government to step in to help tourism recover after the initial response phase of the crisis. For instance, support for tourism businesses, as well as policies focusing on tourism development were considered as non-financial interventions. Financial aid was the primary assistance mentioned, including tax relief, reduction, hiatus, and deferrals; financial aid; grants; funding; guaranteed bridge loans; furlough payments; and bonuses. This financial support is essential for tourism recovery, as this interview quote showed:

In terms of finance, marketing and labour, we can say that all sums up in government funding and subsidies or grants. We have seen that funding is what is going to help tourism businesses to boost tourism in the future. (Interview 13)

We are now in discussion about more policies to implement after the COVID-19 pandemic to facilitate the recovery of the tourism industry. (Interview 9)

DMO interventions

Also, DMOs were perceived as responsible for the recovery of tourism. DMO interventions in assisting with the application for grants, in advertising, and promotion, as well support for cooperation between tourism stakeholders were mentioned by the interviewees:

The DMO team is working closely with the tourism businesses, together we can reconstruct tourism. (Interview 13)

We encourage all the industry partners to see each other as partners rather than competitors. (Interview 9)

The positive side of the crisis for now is that we are not strongly hit by the virus. The number of confirmed cases is quite low, so the pandemic will not affect our brand image negatively. Therefore, we can work on enhancing the existing image of the destination in the minds of potential visitors as soon as the lockdown is over. (Interview 23)

The interviewees also pointed out that it is important to address specific customer segments when achieving crisis recovery. In general, the aim here is to diversify the customer groups.

We realized that it is worth diversifying our target markets more. (Interview 7)

Even now, the challenge is to actively develop domestic tourism. This task, of course, has always been there, but now it is a priority. (Interview 7)

Restart phase

After the tourism recovery phase, the respondents primarily focused on strategic adjustment in order to restart tourism. Regarding this, a strategic orientation was suggested, which determines concrete strategies and specific areas. The tourism organizations recommended carrying out a strategic planning, with a status quo analysis of potential strategies, as well as how to follow these strategies. One of the suggested directions was the development of sustainable tourism, focusing on responsible tourism behaviour and stakeholder cooperation. Strategic enhancements in form of digital developments, improvement of tourism products and quality increases, employee empowerment and innovations were moreover suggested for the restart phase.

Call for sustainable tourism concepts

Referring to the tourism restart phase, the interviews indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a rethinking of tourism towards a more sustainable and responsible service. The restart of tourism was seen as a chance to offer a different kind of tourism for the future. Some interviewees spoke of a future pivot away from ‘overtourism’ or mass tourism, with others also showing that sustainable development is needed in all areas of tourism.

Long-term vision indeed, I think concepts like sustainability will be considered. (Interview 4)

The lockdown may also allow people to rethink their way of consuming and might provoke a desire to return to a simpler way of life, more focused on personal development than on materialism, which could be an opportunity for a radical change in consumption patterns, for more sustainability and environmental awareness. (Interview 25)

Connected destinations will certainly have more positive and faster effects and results. (Interview 17)

Strategic enhancements

The interviewees expected improvements in different areas in the future to enable the restart of tourism. This included strategic areas that can be improved during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, supporting and expanding digitalization could strengthen tourism development. The interviewees also considered the COVID-19 pandemic to be an opportunity to improve the tourism product itself and increase the quality of various offerings. In this sense, they mentioned a higher product differentiation, which will be obligatory for the restart of tourism. In addition, the restart of tourism was seen as an opportunity for employee empowerment. Education and training were recommended here to help counter unemployment in tourism, while improving the qualifications of tourism employees at the same time. Human resource policy should be revised to help better achieve this.

We have also started online training of tourism staff already in quarantine, even with the waiters, concierges and receptionists. So that they can start work with better qualifications once the crisis is over. (Interview 23)

Through the cooperation and communication of tourism stakeholders, more innovative ideas will be generated. (Interview 9)

Building resilience

In terms of coping with the three phases (response, recovery, and restart), the interviewees described the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to build resilience for the future, as they learn from experiences during the current crisis.

Stakeholder collaboration can be particularly useful when enabling and enhancing resilience. The interviewees perceived that the association with and cooperation of stakeholders leads to the strengthening of tourism and the entire destination. Employee training, product enhancement, innovation, development of new target groups, digitization, and sustainable development were additionally perceived as facilitators of resilience. Governments and tourism organizations should thus contribute to an enhanced destination resilience, as shown here:

The leadership during the crisis is very important. Without a strong government, you cannot make a strong decision and long-term decision. (Interview 15)

Discussion

This paper provides insights into tourism organizations’ perceptions of a global crisis in the early phase of crisis response. The first phases of the tourism disaster management framework pre-event and prodromal described by Faulkner (Citation2001) were considered particularly relevant for the interviewees. Although some destinations were preparing for crises in terms of prevention or imminent reactions (Faulkner, Citation2001), the specificity and impact of this pandemic could not, in their opinion, be considered within crisis management plans.

During the response phase, crisis’ impacts need to be assessed and understood, especially regarding the supply and demand of the tourism market. The data highlighted that the response was characterized by the DMOs expecting governmental response. This is in line with earlier research showing that this kind of globally intertwined crisis cannot truly be handled by regional managers. This is why they seek communication with provincial or governmental bodies in situations such as a pandemic, which directs them into the appropriate strategic and even legal directions (Blake & Sinclair, Citation2003). DMOs are key players in tourism destinations; in Europe they play a much more prominent role in managing stakeholders. At these community-oriented destinations (see e.g. Flagestad & Hope, Citation2001), DMOs are responsible for communicating governmental directives to the entrepreneurs at the destination level themselves. Paraskevas et al. (Citation2013) mention how it can be explained that the actors in a tourism destination have different levels of crisis knowledge. Procedural knowledge and ability can usually be found in organizations dealing with natural disasters in the Alps: mountain rescuers, alpine club associations, and disaster control organizations. These correspond to the crisis management plans of the interviewees described above. DMOs often possess behavioural knowledge because they coordinate the complex network of actors at tourism destinations. So, while DMOs take over crisis leadership, they also determine the overall crisis culture at the respective destinations in the long-run. Some actors also display ‘learned ignorance’ (Paraskevas et al., Citation2013, p. 141) i.e. they realize they have no knowledge – this even holds true for the tourism organizations calling for governmental action. During the COVID-19 pandemic, governmental responsibility for crisis response has been addressed by means of tourism policies and governmental communication. Where tourism businesses have waited for DMO actions, the DMO was in turn waiting for the government to formulate precise action. The net effect has been a lack of entrepreneurial action because no proactive initiatives emerged from the local companies.

For the recovery phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, the tourism organizations recognized a strong sense of collaboration within the destination. They had the sense that the single actors try to assist each other using both informal and direct measures. This has been reported in earlier research focusing on natural disaster management (Orchiston & Higham, Citation2016). However, good communication and trust (see Jiang & Ritchie, Citation2017) are key success factors in disaster collaboration. The DMO again plays an important role here in supporting the development of an effective destination crisis culture. The DMO as a collaboration manager can bring together key individuals in the region to respond to a crisis. Further, the DMO itself can take immediate action in terms of carefully reformulating target segments.

The findings connected to government interventions within the recovery phase correspond to the work by Sigala (Citation2020) and Ioannides and Gyimóthy (Citation2020). Economic support such as subsidies or tax relief are considered key determinants of tourism recovery. In this sense, a more sustainable development can be pursued to rebuild a destination into an even stronger business (Ioannides & Gyimóthy, Citation2020; Sigala, Citation2020). With this in mind, Higgins-Desbiolles (Citation2020) nevertheless expresses her concern about governmental interventions encouraging a return to old business practices; the author therefore asks for fair and effective distribution of funds during crises. The interviews clearly showed that these interventions are urgently needed, not only to be able to help in the short term, but also to make the long-term changes discussed above possible. Many of the actions addressed by the interviewees are prerequisites for the creation of future destination resilience, and ultimately achieve an effective crisis culture that includes crisis awareness, communication, and collaboration (Cochrane, Citation2010; Jiang et al., Citation2019; Luthe & Wyss, Citation2014). It can be shown that tourism managers are aware of resilience development actions in the midst of the global health crisis.

Furthermore, DMOs focus on their local resources when it comes to a restart. As a logical response, a stronger focus on sustainability and responsible tourism, as well as on local resources (including employees) was articulated in the interviews, in line with previous studies on resilience in a post-COVID-19 tourism industry (Sharma et al., Citation2021). Sustainability is no longer only a buzzword; it now includes elements that expand well beyond target segmentation. DMOs are key experts who need to initiate further sustainability action. In times of crisis, actors are very aware of the need for change, and as highlighted in earlier research, crises can trigger innovations in tourism destinations (Pechlaner & Tschurtschenthaler, Citation2003; Pikkemaat & Weiermair, Citation2007).

Conclusion and implications

The findings contribute to the growing literature on crisis management and resilience. This paper proposes a crisis management model that entails actions to manage a crisis and build resilience in the response, recovery and restart phases. In particular, the concept of resilience is enhanced by incorporating tourism organizations’ perceptions during a pandemic. The study discussed the importance of government interventions and stimulus packages for destinations to tackle the COVID-19 crisis. Moreover, a connection to the sustainable tourism concept was developed as a recovery strategy for future phases of the crisis. On the practical level, the study informs local authorities and tourism organizations in policy establishment for crisis recovery, as well as in strategy reformulation and development. Practical implications can be drawn for destination managers and tourism policymakers that help them make informed decisions, benchmark their policies during the crisis, and generate new ideas. The determination of policies in this sense refers to the provision of financial support, but also to the inclusion of preferential policies targeting stakeholder collaboration, health and sanitary policies, as well as regulations and rules about registration and visa policies.

Destination managers are willing to take future actions towards responsible and sustainable tourism. They also indicated this kind of orientation among their destination stakeholders such as tourism entrepreneurs (who are key for the success of tourism crisis management (Dahles & Susilowati, Citation2015)). Tourism policymakers and DMOs need to effectively build on this willingness. They can also be motivated to develop strategies and tactical pathways towards responsible tourism. The provision of tourism organizations was also approached in connection with addressing specific customer groups. Here it can be deduced that a focus on domestic tourism contributes not only to crisis recovery, but also adds to a more sustainable development in the long term. In this regard, concrete policies can be addressed to improve the recovery of tourism, for example by implementing policies that promote domestic tourism, in which residents receive tourism vouchers for a holiday in their country.

The interviews besides emphasized that although many actors react, this doesn’t automatically make them proactive. This puts more pressure on DMOs and tourism policy, and often costs time to tackle a crisis of the magnitude of COVID-19. Stronger resilience management in tourism destinations will be necessary, as future crisis management can profit from destinations that are resilient and prepared. Resilience management can only be developed using a participative process involving the major actors at the respective destination (Tosun, Citation2006). The COVID-19 crisis places the focus on a destination’s ability to implement several management competences. A destination-wide management of employees, quality management, digitalization and internal communication is required to be improved to develop resilient tourist destinations. Another recommendation for tourism organizations involves the support of tourism businesses during crises. Tourism organizations should develop standardized systems for the assistance of these businesses, such as guidelines that help companies apply for financial support.

The qualitative nature of this study in general represents a limitation, restricting the generalizability of its results. The interviews were carried out to obtain in-depth insight to achieve an understanding of tourism organizations’ crisis management during the COVID-19 pandemic; they did not aim to achieve generalizable results. Another limitation of the study is its convenience sample of worldwide tourism organizations. A future comparison of destinations based on different systems, for example focused on community-oriented destinations, will provide further insight into the management of the different phases of the crisis. Furthermore, the data was assessed in the midst of the crisis or the first wave of COVID-19, providing an interesting perspective of the tourism organizations’ intentions to act. Future studies should however investigate whether these intentions have equated into consequent action. In addition, longitudinal studies carried out at different phases of the crisis can provide insight into the changing opinions and perspectives of tourism organizations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the 13th generation of Erasmus Mundus European Master in Tourism Management students for their support in the data collection phase.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adger, W. N. (2000). Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Progress in Human Geography, 24(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/030913200701540465

- Aliperti, G., Sandholz, S., Hagenlocher, M., Rizzi, F., Frey, M., & Garschagen, M. (2019). Tourism, crisis, disaster: An interdisciplinary approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 79(5), 102808. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102808

- Amore, A., Prayag, G., & Hall, C. M. (2018). Conceptualizing destination resilience from a multilevel perspective. Tourism Review International, 22(3), 235–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3727/154427218X15369305779010

- Babbie, E. A. (2008). The basics of social research. Thomson Learning Inc.

- Bae, S. Y., & Chang, P.-J. (2020). The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020). Current Issues in Tourism, 11(5), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1798895

- Bhati, A. S., Mohammadi, Z., Agarwal, M., Kamble, Z., & Donough-Tan, G. (2020). Motivating or manipulating: The influence of health-protective behaviour and media engagement on post-COVID-19 travel. Current Issues in Tourism, 29(4), 1–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1819970

- Blake, A., & Sinclair, M. T. (2003). Tourism crisis management. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(4), 813–832. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00056-2

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Cochrane, J. (2010). The sphere of tourism resilience. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(2), 173–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2010.11081632

- Crabtree, B. F., & Miller, M. A. (1992). A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In B. F. Crabtree & W. F. Miller (Eds.), Research methods for primary care: Doing qualitative research (pp. 93–109). Sage.

- Dahles, H., & Susilowati, T. P. (2015). Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 51, 34–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.01.002

- Dai, S., Xu, H., & Chen, F. (2019). A hierarchical measurement model of perceived resilience of urban tourism destination. Social Indicators Research, 145(2), 777–804. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02117-9

- Espiner, S., Orchiston, C., & Higham, J. (2017). Resilience and sustainability: A complementary relationship? Towards a practical conceptual model for the sustainability–resilience nexus in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(10), 1385–1400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1281929

- Farrell, B. H., & Twining-Ward, L. (2004). Reconceptualizing tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(2), 274–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.12.002

- Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism Management, 22(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00048-0

- Filimonau, V., & De Coteau, D. (2020). Tourism resilience in the context of integrated destination and disaster management (DM2). International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2329

- Flagestad, A., & Hope, C. A. (2001). Strategic success in winter sports destinations: A sustainable value creation perspective. Tourism Management, 22(5), 445–461. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00010-3

- Flick, U. (2015). Introducing research methodology: A beginner’s guide to doing a research project (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 12(5), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Hall, C. M., Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2020). Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 577–598. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759131

- Halperin, S., & Heath, O. (2017). Political research: Methods and practical skills (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 610–623. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

- Ioannides, D., & Gyimóthy, S. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 624–632. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763445

- Jamaliah, M. M., & Powell, R. B. (2018). Ecotourism resilience to climate change in Dana Biosphere Reserve, Jordan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(4), 519–536. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1360893

- Jiang, Y., & Ritchie, B. W. (2017). Disaster collaboration in tourism: Motives, impediments and success factors. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 31, 70–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.09.004

- Jiang, Y., Ritchie, B. W., & Verreynne, M-L. (2019). Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: A dynamic capabilities view. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(6), 882–900. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2312

- King, N. (2017). Doing template analysis. In G. Symon & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges (pp. 426–449). Sage.

- King, N., Horrocks, C., & Brooks, J. M. (2019). Interviews in qualitative research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Kvale, S. (1983). The qualitative research interview. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 14(1–2), 171–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/156916283X00090

- Lew, A. A. (2014). Scale, change and resilience in community tourism planning. Tourism Geographies, 16(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.864325

- Luthe, T., & Wyss, R. (2014). Assessing and planning resilience in tourism. Tourism Management, 44, 161–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.03.011

- McCool, S. (2015). Sustainable tourism: Guiding fiction, social trap or path to resilience? In T. V. Singh (Ed.), Challenges in tourism research (pp. 224–234). Channel View Publications.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Neuburger, L., & Egger, R. (2020). Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(5), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1803807

- Orchiston, C., & Higham, J. E. S. (2016). Knowledge management and tourism recovery (de)marketing: The christchurch earthquakes 2010–2011. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(1), 64–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.990424

- Paraskevas, A., Altinay, L., McLean, J., & Cooper, C. (2013). Crisis knowledge in tourism: Types, flows and governance. Annals of Tourism Research, 41(2), 130–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.005

- Pechlaner, H., & Tschurtschenthaler, P. (2003). Tourism policy, tourism organisations and change management in alpine regions and destinations: A European Perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(6), 508–539. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500308667967

- Pikkemaat, B., & Weiermair, K. (2007). Innovation through cooperation in destinations: First results of an empirical study in Austria. Anatolia, 18(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2007.9687036

- Prayag, G. (2018). Symbiotic relationship or not? Understanding resilience and crisis management in tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 133–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.012

- Prayag, G. (2020). Time for reset? Covid-19 and tourism resilience. Tourism Review International, 24(2), 179–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3727/154427220X15926147793595

- Ritchie, B. W. (2004). Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 25(6), 669–683. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.004

- Ritchie, B. W., & Jiang, Y. (2019). A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 102812. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102812

- Romagosa, F. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 690–694. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763447

- de Sausmarez, N. (2007). Crisis management, tourism and sustainability: The role of indicators. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 700–714. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2167/jost653.0

- Sharma, G. D., Thomas, A., & Paul, J. (2021). Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100786. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100786

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

- Tosun, C. (2006). Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management, 27(3), 493–504. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.12.004

- Tse, T. S. M. (2006). Crisis management in tourism. In D. Buhalis & C. Costa (Eds.), Tourism management dynamics-trends, management and tools (pp. 28–38). Elsevier. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-7506-6378-6.50014-7

- UNWTO. (2020). UNWTO World tourism barometer, May 2020: Special focus on the impact of COVID-19. https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-05/Barometer%20-%20May%202020%20-%20Short.pdf

- Wen, J., Kozak, M., Yang, S., & Liu, F. (2021). COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tourism Review, 76(1), 74–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2020-0110