ABSTRACT

The hospitality sector has been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the situation of rural accommodation is particularly noteworthy due to its close relationship with the environment. In this context, the role of CSR as a strategy that contributes to social, economic, and environmental well-being takes on a crucial role. The main objective of this paper is to contribute to the early scientific literature analysing the influence of CSR strategies on the resilience of rural hotels in the wake of COVID-19. A total of 100 Spanish managers’ responses were analysed through PLS-SEM. The findings demonstrate a positive and significant impact of CSR strategies on resilience levels, and the effect of resilience on hotel performance. Additionally, we have found a mediating and moderating effect in the above-mentioned relationship. In terms of moderation, we show that the relationship is intensified when hotels possess an official sustainability certificate. And in terms of mediation, COVID-19 actions carried out by rural accommodations mediate the CSR-resilience relationship. Thus, the contribution of this study lies in providing solid long-term strategic alternatives based on sustainability to enable rural hotels to cope with cyclical crises and provide new insights in the hospitality industry literature.

Introduction

Since the outbreak of COVID-19 at the end of 2019, social, economic, and personal lives have been plagued by uncertainty, and the impact on the tourism and hospitality industry is particularly evident. All activities related to tourism have been paralyzed during the authorities’ continued efforts to reduce and control the pandemic. Though it is true that some sectors and companies have tried to adapt by making use of digital platforms and continue their struggle for survival (Mehrolia et al., Citation2021), other sectors, such as tourism, have been plunged into an unprecedented crisis due to travel restrictions and social isolation (Dube et al., Citation2021). According to WTO (Citation2021a), during the first quarter of 2021 international tourist arrivals plummeted by 83% compared to pre-pandemic levels, with a slightly lesser drop for the countries of Southern Europe (78%). The collapse of international tourism due to the coronavirus pandemic could cause a loss of more than $4 trillion in global GDP in 2020 and 2021 (Vanzetti et al., Citation2021). In Spain, the fall in international tourist arrivals in 2020 was 77% compared to the previous year, representing a 77.3% drop in international tourism receipts (WTO, Citation2021b).

In these times of crisis, it is essential to carry out solid research in hospitality to understand the aftermath of the COVID-19 phenomenon and to support managers and policy makers (Rivera, Citation2020). Following these suggestions, several scholars have been analysing the impact of COVID-19 on the tourism and hospitality sector. Some authors (Polukhina et al., Citation2021) have pointed out the impacts that the COVID-19 crisis could have caused in the achievement of sustainable tourism goals. Hao et al. (Citation2020), in a preliminary and exploratory manner, have reviewed the overall impacts of the pandemic on China's hospitality industry and explained the anti-pandemic phases, principles and strategies. However, given this extremely challenging and exceptional situation, it is important for hospitality managers to understand how to increase their resilience in order to obtain better performance.

Rural hospitality, one of the tourism segments with higher growth in recent years (Villanueva-Álvaro et al., Citation2017), has presented an encouraging evolution during COVID-19, with a faster recovery than any other type of accommodation (Moreno-Luna et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, rural tourism has demonstrated its relevance in the COVID-19 crisis since it is closely linked to social and environmental strategies. In fact, Polukhina et al. (Citation2021) stressed that the existence of a triple bottom line (economic, social and environmental) would help rural tourism not only to survive during the pandemic, but also to develop robust long-term strategies. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided an opportunity for rural hospitality development (Vaishar & Šťastná, Citation2020), but few works have been concerned with advancing the academic literature on these forms of tourism and their ability to survive.

In this context, it is essential not only to focus on the management of hospitality companies at the present time, but also on the role of these companies in society, a subject of debate since the middle of the last century (Turker, Citation2009). In fact, it has traditionally been claimed that corporate activities confer responsibilities that extend to stakeholders (Freeman, Citation2010) beyond the owners, such as to behave ethically with employees, customers, and the wider community (Carroll & Shabana, Citation2010), leading to the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Panwar et al. (Citation2006) define CSR as a strategic and proactive way of doing business in a specific context with a synergistic philosophy.

Despite the prolific research on CSR in the hospitality industry, the academic debate still remains scattered and there is no real consensus on the business case for CSR initiatives (Coombs & Holladay, Citation2015). Recently, authors such as Rhou and Singal (Citation2020) have called on academics to conduct studies examining the impact of CSR initiatives in the hospitality industry under different study contexts. Therefore, at a time such as this, asking what is the specific role of CSR in hospitality is particularly relevant for two reasons: first, in the face of dramatic situations, CSR activities or socially responsible business actions are especially necessary and, second, these practices can contribute to improving the resilience of rural hotels, which is essential for their survival.

Notwithstanding the record-breaking impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the hotel and tourism industries, many hotel organisations have engaged in various CSR initiatives and developed their strategies to help combat the crisis and show solidarity within local communities (Chen & Hang, Citation2021). Indeed, hotels, on a voluntary basis, have contributed to the fight against and recovery from the crisis, both making in-kind contributions and providing free accommodation to health workers, among others. These initiatives have been considered key CSR measures by authors such as Rhou and Singal (Citation2020). Other authors such as Shin et al. (Citation2021) have recently paid special attention to the literature on CSR during the COVID-19 pandemic in the hotel and tourism industry, and have analysed the impact of CSR strategies on hotel performance during the crisis. Likewise, authors such as Filimonau (Citation2021) have studied relevant aspects such as waste management in the hospitality sector after COVID-19, adding that the pandemic will worsen the environmental performance of the sector, although this perspective has not yet been discussed academically. Furthermore, Heinze (Citation2020) has investigated the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on sustainability in rural tourism enterprises using a multi-method approach.

Therefore, following the claim of authors such as Hao et al. (Citation2020), who state that research on CSR during crises or disasters has been neglected in the hospitality and tourism context, we will contribute to the emerging literature addressing the role of CSR in the resilience of rural hotels in the aftermath of COVID-19. Thus, the main objective of this paper is to analyse the influence of CSR strategies on the resilience of rural hotels in the wake of COVID-19, paying special attention to the moderating role of sustainability certificates and the mediating effect of specific social actions carried out by hotels to help customers, employees, and society.

The contribution of this study lies in providing solid long-term strategic alternatives based on sustainability to enable rural hotels to cope with cyclical crises and thus increase their resilience. Furthermore, according to Alonso et al. (Citation2020), our empirical research is extremely useful for the industry in terms of practical strategies since it includes owners-managers’ viewpoints. The paper is organized as follows: First, it reviews the theoretical background, developing the empirical model to be tested. Second, it explains the most important aspects related to the methodology used. Third, it analyses and discusses the results, in order to finish with the conclusions, limitations and future lines of research.

Theoretical background and empirical model

Impact of CSR strategies in the rural hospitality industry

On the premise that companies have responsibilities beyond their profit-making activities and mere legal liability (de los Salmones et al., Citation2005; Maignan et al., Citation1999), and these responsibilities apply not only to shareholders, we draw on the stakeholder perspective (Freeman, Citation2010) to delve into current thinking on CSR in the rural hospitality industry.

Since its introduction in the 1990s, CSR has been very popular in the field of hospitality and tourism and has been considered an integral aspect of the strategic decisions of tourism and hospitality companies (Camilleri, Citation2014). Given the tourism industry's close relationship with environment and society, these companies are expected to have social and ethical responsibilities that go beyond their profit-driven objectives. The specific literature on tourism and CSR includes research such as Kastenholz et al. (Citation2016), who pointed out that one of the topics that was attracting attention was sustainability in rural tourism (Saxena & Ilbery, Citation2010). Indeed, respect for the environment is one of the pillars of the growth of rural tourism, as it is an attraction for today's tourists, whose preferences include sustainability (Villanueva-Álvaro et al., Citation2017).

Several authors initially focused their studies on the phenomenon known as rural tourism, specifically in Spain (Perales, Citation2002), being in line with sustainable rural tourism (Bramwell, Citation1994). Thus, the concept of rural tourism has been linked to sustainability or sustainable and socially responsible development (Ponnan, Citation2013). In addition to the above, Rosalina et al. (Citation2021) add that sustainable development tended to be discussed in almost 41% of the reviewed rural tourism literature. More specifically, in a content analysis of CSR research, Moyeen et al. (Citation2019) indicates rural tourism development and sustainable development among the CSR issues in the hotel industry.

Even though sustainable tourism has received several criticisms in recent years, mainly from academia (Romagosa, Citation2020), highlighting the need to bring it closer to resilience (Cheer & Lew, Citation2017; Hall et al., Citation2017), the relationship between CSR and the performance of hospitality companies has been considered debatable (Nicolau, Citation2008; Rhou & Singal, Citation2020), and has been little examined (Kang et al., Citation2010). Recently, authors such as Shin et al. (Citation2021) highlight the existence of a research stream in hospitality and tourism focused on the impact of hotel CSR on the performance of companies. In general terms, it is noted that studies in this line of literature find a positive impact between the CSR activities of hotel companies and their performance. Meanwhile, Kang et al. (Citation2010) examined different positive and negative impacts of CSR activities on the financial performance of hospitality companies in response to the growing concern for CSR. Nonetheless, several recent authors have argued the multiple benefits for tourism and hospitality companies of incorporating CSR as an essential part of their business strategy, including improved financial performance and competitive advantage (Franco et al., Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2020; Singjai et al., Citation2018; Theodoulidis et al., Citation2017).

On the other hand, much of the research on CSR in hospitality has been concerned not only with organizational performance, but also with building stronger relationships with stakeholders (Martínez et al., Citation2014), where employee perceptions have played an essential role (Mao et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2021). The impact on branding and customer loyalty has also been investigated (Fatma & Rahman, Citation2017) so that CSR activities can serve as a good marketing technique for hotels. However, based on the literature review of CSR in the hospitality and tourism industry by Wong et al. (Citation2019), we note that none of the reviewed papers examined the relationship of CSR with organizational resilience in crisis situations, having focused only on resilience of tourism destinations.

Rural hotels’ CSR strategies in the face of crises or disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic

The populazisation of CSR in tourism and hospitality is not surprising considering the significant challenges faced by companies in this sector, such as climate change, environmental disasters and economic crises (Park & Levy, Citation2014). Given the particular obligations of the tourism industry due to its close relationship with destinations’ environment and society, Henderson (Citation2007) considered it essential to examine the linkages and CSR aspects of hospitality in a context characterised by the devastation caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. He noted that hotels have an ethical responsibility to be prepared for disasters and to recover quickly. Nevertheless, one wonders what constitutes the ability of hospitality companies to cope with critical situations. Authors such as Alonso et al. (Citation2020) put forward resilience theory as a basic framework from which to explore the ability of companies to adapt to current and future external disasters such as COVID-19.

Although it has traditionally been argued that the tourism sector has a high resilience and the ability to adapt and recover from catastrophic or unexpected phenomena (Romagosa, Citation2020), the study of rural hotel resilience towards disasters has been limited (Brown et al., Citation2021). In view of the current situation, hotel managers have been encouraged to take advantage of the shutdown period to make structural and far-reaching changes in the sector, starting with a rethinking of its sustainability with the intention of cleaning up several dark sides of the growth of tourism (Niewiadomski, Citation2020).

Some authors such as Hall et al. (Citation2017) have reviewed the literature on resilience and tourism, focusing on 3 different levels: individual, organizational and destination. Focusing on the organizational level, Orchiston and Espiner (Citation2017) have compared two different resilience practices followed in New Zealand as a consequence of rapid change and uncertainty in this critical tourism sector. In the face of the impact of COVID-19, Ntounis et al. (Citation2021) have studied the resilience of the tourism and hospitality industry, nuancing the different levels of resilience within and between industries. Furthermore, following the review of the emerging literature covering the impact of COVID-19 on the tourism and hospitality sector, Sharma et al. (Citation2021) argue that the study of the resilience of the different actors involved, such as hotels, takes on particular relevance. This situation may enable the creation of new business models, which will determine the sector's chances of survival by converting it into a much more sustainable form.

It should be noted that external disasters can be understood in terms of a natural disaster such as a tsunami (Henderson, Citation2007), an earthquake or a global pandemic (Brown et al., Citation2021). As indicated by Dobie et al. (Citation2018), the hospitality industry plays an essential role in disaster situations as it provides many basic services that contribute to enhancing community resilience. However, Gürlek and Kılıç (Citation2021) stated that the evidence on CSR activities carried out by hotels during the pandemic or during past disasters is scarce. These authors have sought to report on the CSR activities carried out by the world's top hotels during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting among the activities most widely followed: offering free accommodation for health professionals, donating protective equipment to the general population, training employees to stay safe from COVID-19, and eliminating rebooking and cancellation fees.

Recently, authors such as Rosalina et al. (Citation2021) and Marques et al. (Citation2021) have highlighted the need to analyse the impacts of COVID-19, specifically on rural tourism due to its fast recovery capacity, which is its resilience. In fact, rural tourism has been shown to be one of the less damaged types of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading the tourists’ choices (Moreno-Luna et al., Citation2021), as it is considered a safe option in a pandemic (Seraphin & Dosquet, Citation2020) compared to other tourism typologies. Nevertheless, there is little empirical work that has evaluated the impact of CSR strategies on rural hotels in the face of COVID-19. Chen and Hang (Citation2021) have examined the impact of CSR initiatives on rural tourists’ intentions to spread positive word-of-mouth and their intentions to visit when the current pandemic ends. On their part, authors such as Shin et al. (Citation2021) have focused on the impact of socially responsible actions (related to strategic philanthropy towards external stakeholders) aimed at employees. From a different perspective, authors such as Filimonau et al. (Citation2020) have evaluated the organizational resilience of rural hotel companies and CSR practices, in this case to find their impact on the job security of senior executives and their commitment to remain in the company. Indistinctly, there are several studies that relate involvement in CSR activities to the reputation of organizations (Shin et al., Citation2021) and its influence on resilience in times of crisis.

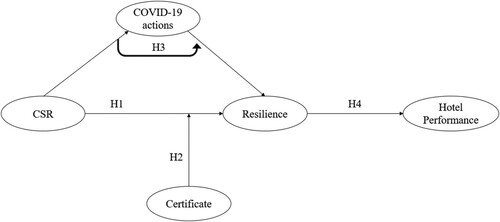

In view of the need to provide a solid empirical development that allows us to further explore the role of CSR in rural hotels in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis, we propose the following research model (see ). First, we consider that there is a direct positive relationship between CSR and the resilience of rural hotel establishments, leading to higher long-term performance. Given the complexities of this relationship, we consider that it is not exclusively direct and is therefore moderated by sustainable certificates, and mediated by specific social actions that hotels have taken in response to COVID-19.

Hypothesis 1. CSR strategies have a positive impact on rural hotel resilience.

Hypothesis 2. The CSR-rural hotel resilience relationship is moderated by the tenure of sustainable certificates.

Hypothesis 3. COVID-19 actions mediate the impact of CSR strategies on rural hotel resilience.

Hypothesis 4. Rural hotel resilience positively influences rural hotel performance.

Methodology

Sample and population

In order to carry out this study, quantitative methods were used and primary sources of information were collected through an ad hoc, self-administered questionnaire. Before the questionnaire was sent out, it was validated using a pre-test in which experts in strategic management of tourist accommodation provided feedback on the clarity and validity of the items employed, concretely three experts in strategic management in tourism and two hotel managers. The target population of the questionnaire is made up of Spanish rural accommodations that are listed in ‘Alimarket’, ‘Central de Comunicación’ and official tourism offices from Spanish autonomous communities’ databases.

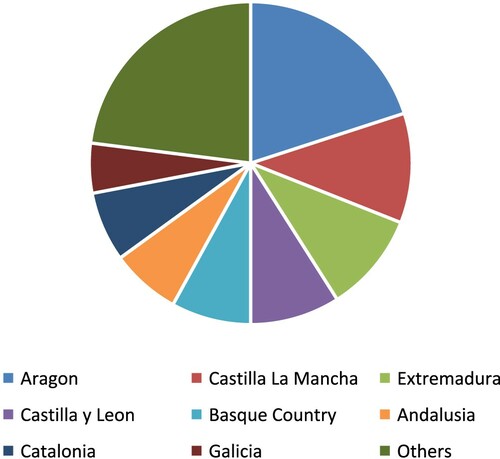

The questionnaire was distributed via the Qualtrics online survey tool in the period between January and May 2021, as the intention was to measure the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on this population during the crisis. Specifically, the questionnaire was addressed to the managers of the rural accommodation in question, obtaining a total of 105 responses, of which we had to eliminate 5 due to the lack of complete responses. Therefore, our study sample is composed of 100 Spanish rural accommodation valid responses. Specifically, the largest number of establishments in our sample are located in Aragon, followed by Castilla La Mancha, Extremadura and Castilla y Leon, although, as can be seen in Graph 1, all Spanish Autonomous Communities are to a greater or lesser extent represented in our sample.

Research questionnaire

For the measurement of the variables we have designed the questionnaire based on previously-validated scales in line with previous studies to ensure consistency, reliability and validity (Agag et al., Citation2020). For CSR we have adapted the scale implemented by Úbeda-García et al. (Citation2021) in the Spanish hotel sector, which was originally developed by Turker (Citation2009), Bai and Chang (Citation2015), Youn et al. (Citation2018) and Su and Swanson (Citation2019) and adapted to measure CSR towards three primary stakeholders: employees, customers, and society (Aguinis & Glavas, Citation2012). In this sense, we have followed Úbeda-García et al.’s (Citation2021) approach when considering the CSR variable as a second-order construct conformed by three first-order constructs following the stakeholders’ approach (CSR customers, CSR employees and CSR society). For the measurement of COVID-19 actions we have used the scale developed and validated by Filimonau et al. (Citation2020) in their recent study focused on Spanish hotels. As the authors indicate in their study, the novelty of the topic revealed the inexistence of previously validated scales to measure the organizational response of hotels to COVID-19. In the case of resilience, the dependent variable of the main regression, we have measured it through an adjustment of the organizational resilience scale of Orchiston and Higham (Citation2016), also previously adapted by Pathak and Joshi (Citation2021). For the performance variable, we have considered the scale of hotel performance adapted from the study of Úbeda-García et al. (Citation2021). In the case of the moderating variable, sustainable certificates, we have followed Aznar et al. (Citation2016), considering it as a dummy variable where 0 meant the absence of certification and 1 its availability. We consider certification to mean any accreditation of compliance with certain social and/or environmental conditions according to criteria established by independent official bodies, examples of which are the certificates ISO, ECOLABEL, HES, Green Key, Rainforest Alliance Certified, among others. The authors of the present study decided not to limit the study to a concrete type of certificate as the interest of the research is not so much to analyse the holding of one certificate over another but rather to find if the possession of an external official certificate granted by a competent authority has an effect when compared to not having a certificate. Thus it is included as a moderating variable.

Analysis technique

Regarding the chosen method of data analysis, we apply Structural Equations Modelling (SEM) based on variance using the statistical package SmartPLS v3.3 (Hair et al., Citation2022). The reasons why we decided to use SEM are diverse, considering that Partial Least Squares (PLS) does not impose a specific distribution group for indicators such as normality and does not require the observations to be independent of each other (Chin, Citation2010). Nevertheless, we should check for kurtosis and skewness so that there is no excessively abnormal data. Additionally, this SEM was highlighted as a ‘silver bullet’ to estimate causal models in many theoretical models and empirical data situations (Hair et al., Citation2014), which has led to a massive development in the PLS-SEM field over the last decade (Hair et al., Citation2019b). In this sense, in the study of Hair et al. (Citation2014) on PLS-SEM in business research, the authors point out that one of the reasons for using PLS-SEM is that it is relevant for studies with relatively small samples, demonstrating high levels of statistical power and much better convergence behaviour than CB-SEM, according to authors such as Reinartz et al. (Citation2009). Additionally, Hair et al. (Citation2020) stress that confirmatory composite analysis (used in PLS-SEM as a substitute for confirmatory factor analysis) is a very useful alternative approach which allows us to confirm the previously established measurement methods that have been adapted or updated to a different context, as is the case in this study. The bootstrapping procedure of 5000 subsamples has been used to estimate the theoretical model. Further characteristics have been taken into consideration when choosing this technique, such as its widespread use in the hospitality sector (Ali et al., Citation2018) and its effectiveness when dealing with multidimensional estimations (Henseler et al., Citation2015).

Results

The analysis of the model presented in the theoretical framework will be divided into two phases, in order to fulfil the theoretical recommendations (Hair, Hult, et al., Citation2017). In the first step, we confirm the reliability and validity of all the indicators, so that we are sure that they are the proper ones to measure our model according to the measurement criteria suggested by the literature (Hair, Hult, et al., Citation2017). In this sense, we should indicate that all the latent variables analysed in our model are reflective constructs.

In the assessment of the measurement model, we focused on individual reliability of the items showing that all factorial loadings exceed both 0.4 (Hair et al., Citation2011) and the most demanding requirement of 0.707 (Carmines & Zeller, Citation1979; Hair et al., Citation2019a) in the great majority of cases. Then, we also checked whether the composite reliability index was higher than 0.7 (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994). Additionally, convergent validity of the constructs was examined through the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) metric (Henseler et al., Citation2009), showing that all constructs’ AVE exceeded 0.5. For the examination of discriminant validity, two different criteria were taken into consideration. On the one hand, we checked that Fornell and Larcker’s (Citation1981) criterion was fulfilled. On the other hand, we have also verified the Heterotrait-Monotrait criterion following Henseler et al.'s (Citation2016) advice, where we show that all values are below 0.9, which shows the existence of discriminant validity.

Once the first step was completed, we moved on to the second step, in which we measured the results of the structural model and tested the hypotheses. As a preamble, we checked that the desired levels of collinearity between the variables of the model were met. To this end, we analysed the VIF (Variance Inflation Factor), based on the recommended values of VIF <3.3 or <5 acceptable for all predictor variables in the model (Hair, Matthews, et al., Citation2017). In this sense, we can demonstrate (see ) that there are no collinearity problems between the variables in our model.

Table 1. Assessment of collinearity between the variables.

In this second step, for the assessment of the structural model, we focused on hypotheses testing through a bootstrapping process, with a resample amount of 5000, using a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval and a two-tailed test. This process was performed before testing the mediation effects. shows the results of the analysis. As shown in , the effect of CSR on resilience is highly significant, presenting a coefficient value (β) of 0.539 at p < 0.01, which allows us to demonstrate the main relationship of our model through Hypothesis 1, in line with previous studies such as Filimonau et al. (Citation2020). As for Hypothesis 4, which showed the direct relationship Resilience-Hotel Performance, it is also confirmed, turning out to be positive and significant, in this case with a coefficient value (β) of 0.393 (p < 0.01). These results are in accordance with those of previous studies that demonstrate the existence of a relationship between resilience and performance (Sobaih et al., Citation2021).

Table 2. Hypotheses testing and summary of the main results.

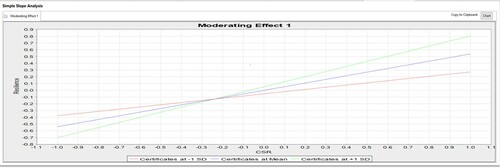

At the same time, we analysed the moderating effect of the availability of sustainability certificates on the relationship between CSR and resilience (see ). In this sense, once the requirement for hotels to engage in CSR practices is fulfilled, the influence of CSR on resilience is higher for hotels with sustainability certificates (green) compared to those lacking such certificates (red) (see ).

In this part, we also carried out a mediation analysis of the variable ‘COVID-19 actions’ in the main relationship (CSR-Resilience) through the testing process of Hypothesis 3. The results obtained can be checked in , where we show that the mediation of COVID-19 actions in the CSR-resilience relationship is significant with β = 0.640 with p > 0.05. As we can see, there is complementary partial mediation, as the relationships CSR-COVID-19 actions and COVID-19 actions-Resilience as well as CSR-Resilience are positive and significant.

Table 3. Summary of the mediating effect results.

As for the control variables, size exerts a positive and significant influence on hotel performance, in accordance with other views. Nevertheless, the gender of the rural hotel manager was not found to be significant.

Furthermore, the structural model has also been evaluated using the coefficient of determination (). In this case, the values that have been obtained for the endogenous variables ‘Resilience’ and ‘Performance’ are 0.478 and 0.242, respectively, which indicates a substantial and moderate (Chin, Citation1998; Hair et al., Citation2014) explanatory power. Finally, we checked whether the model presented in this paper has a good overall fit and predictive relevance, through Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMSR) and Geisser test (Q2) values, respectively. The SRMSR value is 0.096, which compared to 0.10 (Williams et al., Citation2009) is considered as acceptable. The Q2 is higher than zero (Hair et al., Citation2019a), which demonstrates predictive relevance of the model for each endogenous variable.

Conclusions and implications

In this paper we have provided new insights in the hospitality industry, regarding one of the most recommendable strategies for increasing resilience levels in times of uncertainty.

The aim of this paper focuses on analysing the relevance of CSR strategies for the achievement of optimal resilience levels in the hospitality industry, specifically in the rural hotel subsector in Spain. This approach is in line with recent theoretical recommendations by authors such as Sharma et al. (Citation2021) or the theoretical approach recommended by Alonso et al. (Citation2020). The choice of the aforementioned objective responds to the call of researchers specialized in the area who point to the need to carry out solid research to enable managers and policy makers in the hospitality industry to address the COVID-19 crisis (Rivera, Citation2020).

Pioneering authors have analysed the impact of COVID-19 in different areas of the hospitality sector (Hao et al., Citation2020; Hsieh et al., Citation2020) but few studies have examined the impact of COVID-19 in the field of rural accommodation, which was a compelling factor to develop the current research, taking into consideration the reported benefits that the COVID-19 crisis has brought to rural hotels (Marques et al., Citation2021; Moreno-Luna et al., Citation2021; Rosalina et al., Citation2021; Seraphin & Doquet, 2020; Vaishar & Šťastná, Citation2020).

Our results demonstrate the existence of a positive and significant impact of the development of a CSR strategy by Spanish rural accommodations on their resilience levels (Hypothesis 1). This relationship is intensified when hotels possess an official sustainability certificate, with this variable acting as a moderator in the main relationship (Hypothesis 2), which allows us to contribute to the field of research that points to the moderating power of sustainability certificates (Kim et al., Citation2016; Duque-Grisales et al., Citation2020). Additionally, we have been able to demonstrate that COVID-19 actions carried out by selected rural accommodations mediate the relationship between CSR and resilience (Hypothesis 3), being able to bring a new approach to recent studies on COVID-19 actions that had analysed the role of organizational response to COVID-19 in the hospitality industry (Filimonau et al., Citation2020) and specifically the relevance of this type of actions in the field of CSR (Rhou & Singal, Citation2020). These results are also in line with those of He and Harris (Citation2020), who suggested that the pandemic represented an opportunity for tourism companies to demonstrate their commitment to a more authentic CSR. According to these authors, it is hoped that these CSR commitments will be perceived as more significant and impactful by clients and the general public than pre-pandemic CSR actions. It should be stressed that, despite the demonstrated existence of mediation, the CSR impact on resilience is preponderant over mediation, thus the present study demonstrates the imperative capacity of solid long-term strategies such as CSR to enable hotels to cope with cyclical crises such as COVID-19, as compared to short-term actions aimed at survival. This aspect can be seen in the high level of variance explained by strategic CSR of resilience. In line with the above, our results on the existence of higher resilience levels derived from CSR strategies support the conclusions of previous authors in the field (Marques et al., Citation2021) who propose strengthening rural tourism in the face of the pandemic. Another relevant result was the impact of resilience on performance, with a significant and positive relationship, which is in line with previous findings (Hallak et al., Citation2018; Sobaih et al., Citation2021). Given this relationship and taking into account the variance explained by resilience in performance, we argue that, although it could be an explanatory factor, it requires another series of strategic factors that complement and explain it to a greater extent, which opens another very interesting line of research in this field.

The contributions of this study are of great relevance for academia as well as for rural accommodation managers. In terms of theoretical contributions, we have increased the empirical evidence that demonstrates the existence of a positive relationship between CSR and resilience, as well as between resilience and performance, providing robust empirical demonstrations that strengthen the foundations of the initial contributions in this field, such as that of Filimonau et al. (Citation2020), who introduced the relationship between CSR and resilience, and that of Sobaih et al. (Citation2021) on the relationship between resilience and performance. In fact, this study clears the path for researchers who wish to redirect tourism strategies towards sustainability by relating responsible strategies with capabilities linked to business survival, such as resilience, in line with contributions such as Romagosa (Citation2020). This finding allows us to guide managers’ actions towards the adoption of solid CSR strategies that will allow them to survive in the face of cyclical crises and maintain a stable position in the long term. Moreover, demonstrating the moderating effect of certificates will encourage them to effectively materialize their CSR activities, moving away from the greenwashing practices that have traditionally been linked to CSR as a superficial way of demonstrating the sustainable position of hotels, supporting views such as that of Geerts (Citation2014) who advocated the role of certificates in combating greenwashing in the context of hotels.

Regarding the limitations and future lines of research, we highlight the fact that our focus on one sub-sector, specifically rural accommodation, prevents us from generalizing our results to the rest of the sub-sectors that make up the hospitality industry. Furthermore, focusing our study on Spain could limit the study to national idiosyncrasies, so two possible future lines of research could deal with both limitations, on the one hand extending the analysis to other countries, and, on the other hand, broadening the study to other sub-sectors that make up the hospitality industry.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agag, G., Brown, A., Hassanein, A., & Shaalan, A. (2020). Decoding travellers’ willingness to pay more for green travel products: Closing the intention–behaviour gap. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(10), 1551–1575. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1745215

- Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311436079

- Ali, F., Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Ryu, K. (2018). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(1), 514–538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2016-0568

- Alonso, A. D., Kok, S. K., Bressan, A., O’Shea, M., Sakellarios, N., Koresis, A., Buitrago Solis, M. A., & Santoni, L. J. (2020). COVID-19, aftermath, impacts, and hospitality firms: An international perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102654. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102654

- Aznar, J. P., Sayeras, J. M., Galiana, J., & Rocafort, A. (2016). Sustainability commitment, new competitors’ presence, and hotel performance: The hotel industry in Barcelona. Sustainability, 8(8), 755. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su8080755

- Bai, X., & Chang, J. (2015). Corporate social responsibility and firm performance: The mediating role of marketing competence and the moderating role of market environment. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32(2), 505–530. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9409-0

- Bramwell, B. (1994). Rural tourism and sustainable rural tourism. Journal of Sustainable tourism, 2(1-2), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589409510679

- Brown, N. A., Feldmann-Jensen, S., Rovins, J. E., Orchiston, C., & Johnston, D. (2021). Exploring disaster resilience within the hotel sector: A case study of Wellington and Hawke’s Bay New Zealand. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 55, 102080. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102080

- Camilleri, M. (2014). Advancing the sustainable tourism agenda through strategic CSR perspectives. Tourism Planning & Development, 11(1), 42–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2013.839470

- Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. N. 07-017, Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. Sage.

- Carroll, A. B., & Shabana, K. M. (2010). The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 85–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00275.x

- Cheer, J. M., & Lew, A. A. (Eds.). (2017). Tourism, resilience and sustainability: Adapting to social, political and economic change. Routledge.

- Chen, Z., & Hang, H. (2021). Corporate social responsibility in times of need: Community support during the COVID-19 pandemics. Tourism Management, 87, 104364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104364

- Chin, W. W.. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research (pp. 295–336).

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In V. Esposito, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (pp. 655–690). Springer-Verlag.

- Coombs, T., & Holladay, S. (2015). CSR as crisis risk: Expanding how we conceptualize the relationship. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 20(2), 144–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-10-2013-0078

- de los Salmones, M. M. G., Crespo, A. H., & del Bosque, I. R. (2005). Influence of corporate social responsibility on loyalty and valuation of services. Journal of Business Ethics, 61(4), 369–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-5841-2

- Dobie, S., Schneider, J., Kesgin, M., & Lagiewski, R. (2018). Hotels as critical hubs for destination disaster resilience: An analysis of hotel corporations’ CSR activities supporting disaster relief and resilience. Infrastructures, 3(4), 46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures3040046

- Dube, K., Nhamo, G., & Chikodzi, D. (2021). COVID-19 cripples global restaurant and hospitality industry. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(11), 1487–1490. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1773416

- Duque-Grisales, E., Aguilera-Caracuel, J., Guerrero-Villegas, J., & García-Sánchez, E. (2020). Does green innovation affect the financial performance of multilatinas? The moderating role of ISO 14001 and R&D investment. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(8), 3286–3302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2572

- Fatma, M, & Rahman, Z. (2017). An integrated framework to understand how consumer-perceived ethicality influences consumer hotel brand loyalty. Service Science, 9(2), 136–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/serv.2016.0166

- Filimonau, V. (2021). The prospects of waste management in the hospitality sector post COVID-19. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 168, 105272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105272

- Filimonau, V., Derqui, B., & Matute, J. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational commitment of senior hotel managers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102659. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102659

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Franco, S., Caroli, M. G., Cappa, F., & Del Chiappa, G. (2020). Are you good enough? CSR, quality management and corporate financial performance in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102395

- Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Geerts, W. (2014). Environmental certification schemes: Hotel managers’ views and perceptions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 39, 87–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.02.007

- Gürlek, M., & Kılıç, İ. (2021). A true friend becomes apparent on a rainy day: Corporate social responsibility practices of top hotels during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 905–918. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1883557

- Hair Jr, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Castillo Apraiz, J., Cepeda Carrión, G., & Roldán, J. L. (2017). Manual de partial least squares structural equation modeling (pls-sem). OmniaScience Scholar.

- Hair Jr, J. F., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.10008574

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019a). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019b). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 566–584. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0665

- Hall, C. M., Prayag, G., & Amore, A. (2017). Tourism and resilience: Individual, organisational and destination perspectives. Channel View Publications.

- Hallak, R., Assaker, G., O’Connor, P., & Lee, C. (2018). Firm performance in the upscale restaurant sector: The effects of resilience, creative self-efficacy, innovation and industry experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 40, 229–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.10.014

- Hao, F., Xiao, Q., & Chon, K. (2020). COVID-19 and China’s hotel industry: Impacts, a disaster management framework, and post-pandemic agenda. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102636

- He, H., & Harris, L. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. Journal of Business Research, 116, 176–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.030

- Heinze, L. M. (2020). Covid-19 as an opportunity for more sustainable tourism: A realistic expectation? (Unpublished doctoral dissertation).

- Henderson, J. C. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and tourism: Hotel companies in Phuket, Thailand, after the Indian Ocean tsunami. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26(1), 228–239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2006.02.001

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In R. R. Sinkovics & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), New challenges to international marketing (Advances in International Marketing, Vol. 20) (pp. 277–319). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Hsieh, H. C., Nguyen, X. H., Wang, T. C., & Lee, J. Y. (2020). Prediction of knowledge management for success of franchise hospitality in a post-pandemic economy. Sustainability, 12(20), 8755. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208755

- Kang, K. H., Lee, S., & Huh, C. (2010). Impacts of positive and negative corporate social responsibility activities on company performance in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(1), 72–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.05.006

- Kastenholz, E., Carneiro, M. J., & Eusébio, C. (Eds.). (2016). Meeting challenges for rural tourism through co-creation of sustainable tourist experiences. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Kim, H, Rhou, Y, Topcuoglu, E. (2020). Why hotel employees care about Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Using need satisfaction theory. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87, 102505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102505

- Kim, W. G., Li, J. J., & Brymer, R. A. (2016). The impact of social media reviews on restaurant performance: The moderating role of excellence certificate. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 55, 41–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.03.001

- Maignan, I., Ferrell, O. C., & Hult, G. T. M. (1999). Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(4), 455–469. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070399274005

- Mao, Y., He, J., Morrison, A. M., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. (2021). Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: From the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(19), 2716–2734. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1770706

- Marques, C. P., Guedes, A., & Bento, R. (2021). Rural tourism recovery between two COVID-19 waves: The case of Portugal. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1910216

- Martínez, P., Pérez, A., & del Bosque, I. R. (2014). Exploring the role of CSR in the organizational identity of hospitality companies: A case from the Spanish tourism industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1857-1

- Mehrolia, S., Alagarsamy, S., & Solaikutty, V. M. (2021). Customers response to online food delivery services during COVID-19 outbreak using binary logistic regression. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(3), 396–408. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12630

- Moreno-Luna, L., Robina-Ramírez, R., Sánchez, M. S. O., & Castro-Serrano, J. (2021). Tourism and sustainability in times of COVID-19: The case of Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1859. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041859

- Moyeen, A., Kamal, S., & Yousuf, M. (2019). A content analysis of CSR research in Hotel Industry, 2006–2017. In David Crowther, Shahla Seifi, & Tracey Wond (Eds.), Responsibility and governance (pp. 163–179). Springer.

- Nicolau, J. L. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: Worth-creating ctivities. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(4), 990–1006. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.09.003

- Niewiadomski, P. (2020). COVID-19: From temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 651–656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757749

- Ntounis, N., Parker, C., Skinner, H., Steadman, C., & Warnaby, G. (2021). Tourism and hospitality industry resilience during the Covid-19 pandemic: Evidence from England. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1883556

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Orchiston, C., & Espiner, S. (2017). Fast and slow resilience in the New Zealand tourism industry. In Alan A. Lew & Joseph M. Cheer (Eds.), Tourism resilience and adaptation to environmental change (pp. 250–266). Routledge.

- Orchiston, C., & Higham, J. (2016). Knowledge management and tourism recovery (de)marketing: The Christchurch earthquakes 2010–2011. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(1), 64–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.990424

- Panwar, R., Rinne, T., Hansen, E., & Juslin, H. (2006). Corporate responsibility: Balancing economic, environmental, and social issues in the forest products industry. Forest Products Journal, 56(2), 4–13.

- Park, S. Y., & Levy, S. E. (2014). Corporate social responsibility: Perspectives of hotel frontline employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(3), 332–348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2013-0034

- Pathak, D., & Joshi, G. (2021). Impact of psychological capital and life satisfaction on organizational resilience during COVID-19: Indian tourism insights. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(17), 2398–2415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1844643

- Perales, R. M. Y. (2002). Rural tourism in Spain. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(4), 1101–1110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00025-7

- Polukhina, A., Sheresheva, M., Efremova, M., Suranova, O., Agalakova, O., & Antonov-Ovseenko, A. (2021). The concept of sustainable rural tourism development in the face of COVID-19 crisis: Evidence from Russia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(1), 38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14010038

- Ponnan, R. (2013). Broadcasting and socially responsible rural tourism in Labuan, Malaysia. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 5(4), 398–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-03-2013-0019

- Reinartz, W., Haenlein, M., & Henseler, J. (2009). An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 26(4), 332–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2009.08.001

- Rhou, Y., & Singal, M. (2020). A review of the business case for CSR in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 84, 102330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102330

- Rivera, M. A. (2020). Hitting the reset button for hospitality research in times of crisis: Covid19 and beyond. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87, 102528. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102528

- Romagosa, F. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 690–694. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763447

- Rosalina, P. D., Dupre, K., & Wang, Y. (2021). Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47, 134–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.03.001

- Saxena, G., & Ilbery, B. (2010). Developing integrated rural tourism: Actor practices in the English/Welsh border. Journal of Rural Studies, 26(3), 260–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2009.12.001

- Seraphin, H, & Dosquet, F. (2020). Mountain tourism and second home tourism as post COVID-19 lockdown placebo. Worldwide hospitality and tourism themes, 12, 485–500. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-05-2020-0027

- Sharma, G. D., Thomas, A., & Paul, J. (2021). Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100786. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100786

- Shin, H., Sharma, A., Nicolau, J. L., & Kang, J. (2021). The impact of hotel CSR for strategic philanthropy on booking behavior and hotel performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Management, 85, 104322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104322

- Singjai, K., Winata, L., & Kummer, T. F. (2018). Green initiatives and their competitive advantage for the hotel industry in developing countries. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 75, 131–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.03.007

- Sobaih, A. E. E., Elshaer, I., Hasanein, A. M., & Abdelaziz, A. S. (2021). Responses to COVID-19: The role of performance in the relationship between small hospitality enterprises’ resilience and sustainable tourism development. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102824. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102824

- Su, L., & Swanson, S. R. (2019). Perceived corporate social responsibility’s impact on the well-being and supportive green behaviors of hotel employees: The mediating role of the employee-corporate relationship. Tourism Management, 72, 437–450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.01.009

- Theodoulidis, B., Diaz, D., Crotto, F., & Rancati, E. (2017). Exploring corporate social responsibility and financial performance through stakeholder theory in the tourism industries. Tourism Management, 62, 173–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.03.018

- Turker, D. (2009). Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 411–427. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9780-6

- Úbeda-García, M., Claver-Cortés, E., Marco-Lajara, B., & Zaragoza-Sáez, P. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the hotel industry. The mediating role of green human resource management and environmental outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 123, 57–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.055

- Vaishar, A., & Šťastná, M. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural tourism in Czechia preliminary considerations. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1839027

- Vanzetti, D, Peters, R, & Gopalakrishnan, B N. (2021). Assessing the Economic Consequences of Covid-19. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. http://tcmih.ku.ac.ke/handle/123456789/245

- Villanueva-Álvaro, J. J., Mondéjar-Jiménez, J., & Sáez-Martínez, F. J. (2017). Rural tourism: Development, management and sustainability in rural establishments. Sustainability, 9(5), 818. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su9050818

- Williams, L. J., Vandenberg, R. J., & Edwards, J. R. (2009). 12 structural equation modeling in management research: A guide for improved analysis. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 543–604. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903065683

- Wong, A. K. F., Kim, S., & Lee, S. (2019). The evolution, progress, and the future of corporate social responsibility: Comprehensive review of hospitality and tourism articles. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 1–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2019.1692753

- World Tourism Organization. (2021a). UNWTO Global Tourism Dashboard INTERNATIONAL TOURISM AND COVID-19 [Data Dashboard]. Retrieved July 15, 2021, from https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-and-covid-19

- World Tourism Organization. (2021b). UNWTO Global Tourism Dashboard COUNTRY PROFILE – INBOUND. Retrieved July 15, 2021, from https://www.unwto.org/country-profile-inbound-tourism

- Youn, H., Lee, K., & Lee, S. (2018). Effects of corporate social responsibility on employees in the casino industry. Tourism Management, 68, 328–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.018

- Zhang, J., Xie, C., & Morrison, A. M. (2021). The effect of corporate social responsibility on hotel employee safety behavior during COVID-19: The moderation of belief restoration and negative emotions. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 233–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.12.011

A

Measurement of variables

CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY (1 = I totally disagree; 7 = I totally agree)

CSR towards society

Our hotel implements special programmes to minimize its negative impact on the natural environment.

Our hotel participates in activities designed to protect and improve the natural environment.

Our hotel seeks sustainable growth to help future generations.

Our hotel emphasizes the importance of its social responsibilities to society.

CSR towards customers

Our hotel provides full and detailed information to our guests.

Our hotel respects the rights of consumers over and above the legal requirements.

Client satisfaction is a priority for our hotel.

CSR towards employees

Our hotel supports employees that wish to receive additional training.

Our hotel encourages its employees to develop their skills and professional careers.

Our hotel has a flexible working policy.

The management of our hotel consider the needs and wishes of the employees.

COVID-19 ACTIONS (1 = infrequently; 7 = very frequently)

Our employees have been offered financial aid during the periods of temporary closure.

Our employees have been offered temporary alternative employment.

100% of reservations cancelled by guests due to COVID-19 have been reimbursed.

Vouchers have been offered to clients to compensate for reservations that have been paid for but which they were unable to enjoy.

The facilities of our hotel have been used as hospitals or shelters for essential workers.

Excess food has been donated (employees, charities, etc.) due to closure of the hotel.

RESILIENCE (1 = fully disagree; 7 = fully agree):

Our hotel proactively studies its competitive environment in order to be prepared for any crisis or disaster.

Our hotel has clearly defined priorities during and after COVID-19.

Our hotel has established relationships with organizations which it can work with during and after COVID-19.

Our hotel has enough resources in reserve to face unexpected changes such as COVID-19.

The management of our hotel show good leadership in the face of these situations.

Our hotel has appropriate planning for the unexpected.

The employees of our hotel are committed and contribute solutions to these situations.

Our employees are trained to perform any tasks where necessary.

Our hotel is known for its capacity to use knowledge in novel ways.

Our hotel is able to make difficult decisions quickly.

We consider that the development and implementation of our emergency plans is effective in these situations.

HOTEL PERFORMANCE (1 = fully disagree; 7 = fully agree)

The growth of our market share is greater than the industry average.

Our company's brand awareness is greater than the industry average.

Our sales growth is larger than the industry average.

Our employee satisfaction is greater than the industry average.

Our customer satisfaction is greater than the industry average.

Our income-per-room is greater than the industry average.

Our occupancy rate is greater than the industry average.

Our average daily rate is greater than the industry average.