ABSTRACT

This paper contributes to recent debates about memorials and the persistence of outmoded forms that commemorate figures associated with slavery and colonial depredations. The focus is on John Batman, often considered to be the founder of Melbourne, and a subject that has been commemorated in numerous forms. We explore the ways in which reified understandings of Batman were consolidated by these memorials. We argue that they provided a basis for the rampant settler colonialism that was initiated by his arrival in what became Melbourne. While the power of the Batman myth has endured for many years, we show how more recently it has been challenged by a range of art-inspired memorials that provide oppositional and alternative meanings and forms. We especially focus on the potency of counter-memorials, forms that directly address these older modes of commemoration, and anti-memorials, inventive installations that seek to dissolve singular meanings and continue the work of decentring outmoded commemorative forms and narratives.

Introduction: remembering Batman

In recent years, many memorials have come under intensified scrutiny, as the values and ideologies they express about historical figures and events are critically interrogated. This especially applies to those that commemorate characters enmeshed with colonial exploitation and slave economies, ‘explorers, colonial governors and administrators, British political figures and members of the British monarchy’.Footnote1 This critical surge is manifest in the political demands and dissident demonstrations culminating in the 2020 toppling of eighteenth century philanthropist Edward Colston in Bristol, UK, because of his active role in the slave trade, and successful campaigns to remove more than 160 Confederate statues in the USA. In Australia, numerous commemorative forms have veiled the dispossession of First Nations people and ignored the violence and injustice that enabled the establishment of Australia as a British settler colony; they are similarly subject to widespread contestation.

Like other Australian cities, many colonial and nationalist figures and events are inscribed on Melbourne’s place names, punctuate its annual public holidays and are memorialized in statues. In this paper we explore the creation of these settler colonial commemorations and how they are increasingly challenged by critique and new memorials that consider settler colonial history differently. More specifically, we investigate the potentialities of counter-memorials and anti-memorials, forms that unsettle how particular subjects are memorialized by offering new symbolic, material and discursive approaches. This we do by investigating several monuments that commemorate John Batman, commonly regarded as the ‘founder’ of Melbourne, who arrived on the banks of the Birrarung (Yarra) River in 1835, concluding with a discussion about a recent unique anti-memorial that questions the possibility of commemorating such a contested historical character.

The configuration of Batman’s colonialist legend rest on two key elements. First, he is frequently cited as having proclaimed, ‘This will be the place for a village’ upon espying the shoreline of the river from his boat. Second, he subsequently declared that he had negotiated a treaty with the sovereign Kulin people of this land, exchanging around 240,000 hectares of land upon which central Melbourne would be built for 20 blankets, 30 tomahawks, 100 knives, 50 pairs of scissors, 30 looking glasses, 200 handkerchiefs, 100 pounds of flour and six shirts. This transaction has always been mired in controversy; some assert that it is a pure invention that could not have been made with those from a different cultural background and language, or that rather than ceding territory, it merely offered permission to pass through the land. Crucially, the official colonial power invalidated the treaty because it contravened the principle (or legal fiction) of terra nullius, by which the Australian continent was declared unoccupied, and therefore available for colonization,Footnote2 despite its long-lasting inhabitation by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Nonetheless, Batman’s mooted role in Melbourne’s founding came to resonate strongly with local settler colonial desires, for the story of the treaty sustained a powerful place-myth that confirmed that the land they had appropriated was rightfully theirs, obviating suggestions of dispossession.

Batman remains a controversial figure. Early accounts contend that the treaty exemplifies evidence of Batman’s affection for Aboriginal folk, the basis for a respectful ceding of territory. Some assert that however iniquitous its terms, the treaty acknowledges that Aboriginal people were the original inhabitants of the land.Footnote3 Yet narratives that regard it as opportunistic and deceitful have become more prominent. Furthermore, records of Batman’s active involvement in the hunting, capture and execution of Aboriginal people in Tasmania in the late 1820s are detailed in his reports to Governor Arthur, who noted that he had ‘much slaughter to account for’, and in the Hobart Town Courier that reported these violent encounters with Aboriginal people.Footnote4 Contemporary accounts point to his legacy of greed, murder and appropriation.Footnote5 His declining reputation is compounded by his squalid death, for Batman died penniless on 6 May 1839, probably from syphilis, his funeral attended solely by his Aboriginal servants. Yet ironically, though disregarded at the time of his death, Batman’s legacy came to be widely celebrated and subsequently contested at a host of commemorative sites across Melbourne.

Melbourne’s memorial landscapes

As MarschallFootnote6 remarks, most memorials serve as devices through which ‘groups can gain visibility, authority and legitimacy’, material reminders that the powerful can impose selective meanings, values, ordering narratives and political ideals across space. Such memorials are often familiar landmarks sited at points of congregation and passage, along major roads, squares and symbolic sites of political and civic authority. Melbourne accommodates numerous stone and bronze commemorative forms, installed between the late 19th to the early twentieth century, with many clustered in the Domain Parklands, along central thoroughfares and beside iconic buildings.Footnote7

In Melbourne, these memorials to settler colonial and imperial figures alongside the exclusion of any recognition of Aboriginal history, identity and presence has constituted a highly selective, authoritative imposition of memory on civic space by state and elite groups. These commemorative fixtures have become a familiar part of the quotidian urban experience of central Melbourne and undergird the normalcy of white possession,Footnote8 consolidating a form of common sense that this is what and how urban memorialization should be inscribed. Through such strategies, DwyerFootnote9 contends, an ongoing ‘symbolic accretion’ condenses memory, promoting ‘one cause by dampening another, in the process suturing competing versions of the past one to the other’. Such memorials are actively implicated in the process of forgetting, both by reducing the commemorative subject to a simplistic representation of what is invariably a complex history, and by focusing on the linear emergence of an urban, settler colonial identity that has excluded any Indigenous memorialization. Successive memorials to John Batman are part of this symbolic accretion, both to the man himself and as part of settler colonial commemoration.

Yet while the funders and creators of memorials seek to convey imperishable meanings and values, over time memorials are doomed to losing their symbolic and political significance, perhaps becoming indecipherable and stylistically obsolescent.Footnote10 As historical interpretations change, along with social, aesthetic and political values, once cherished monuments can be disregarded or become subject to critical re-readings, as we exemplify. Since Melbourne’s nineteenth century origins, diverse communities have contested and erected memorials. The most dramatic commemorative addition has been the colossal 1934 Shrine of Remembrance, which memorializes the sacrifice of the Anzac Troops in the First World War. An annual ritual of remembrance attended by around 40,000 people is staged at the monument,Footnote11 which remains freighted with nationalist ideologies that are repeatedly reinforced in national and local media.

Shanahan and ShanahanFootnote12 emphasize that contemporary Melbourne is continuously in a ferment concerning its relationship with the past. Such intense contestations signify the late twentieth century shift towards what AtkinsonFootnote13 terms the ‘democratisation of memory’. The decline of the ‘top-down’, authoritative dissemination of memories continues to be supplanted by a ‘polyphony of voices that start to weave together a complex, shifting, contingent but continually evolving sense of the past and its abundant component elements’.Footnote14 In Melbourne, a diverse, expanding array of memorials articulate multiple sentiments, evoke a variety of people, events and histories, and are constructed in many different styles. Moving away from commanding figures on large plinths, many post-1945 memorials move towards more interactive, grounded and abstract forms that draw onlookers into embodied encounters.Footnote15 They embrace vernacular, critical and satirical forms,Footnote16 guerrilla compositions and enigmatic installations.Footnote17 Popular cultural figures ‘with whom audiences have intimate affective relations by virtue of decades long appearances within their domestic spaces’Footnote18 increasingly appear, including the plethora of bronze athletes and cricketers that surround the iconic Melbourne Cricket Ground. Most critically, however, these monuments progressively often include formerly neglected cultural minorities, women and political activists and, as we discuss below, memorials to Aboriginal people and places in which ‘alternative constructions of identity and narratives of place’ represent what RobertsonFootnote19 terms ‘heritage from below’.

Some of these are counter-memorials that explicitly question dominant historical accounts, reflect ambivalence about national histories, or are physically positioned to dialogically interrogate older memorials. They encourage debate and reflection, offering ‘a way to think about … history that reveals it as complex and internally contested, rather than the settled and monolithic version of the past’.Footnote20 Other forms, anti-memorials, decentre reified narratives and ‘encourage multiple readings’.Footnote21 They exemplify Tello’sFootnote22 conception of ‘counter memories’ that ‘contest the hegemony of monolithic, monumental memory sites and historiography’ not by dialectically counterposing one history against another but by assembling multiple histories. Such approaches are attuned to heterogeneity and excess and can sidestep universalist, dualistic and stagnant ways of interpreting and feeling. Anti-memorials acknowledge the multiplicity and fluidity of memories, and often emerge after a period of artistic experimentation, historical research and widespread consultation. Moreover, anti-memorials often extend spatial and material relationships, and this includes digital and online approaches.

In what follows, we discuss diverse monuments to John Batman from different periods of Melbourne’s history. We combine written historical and contemporary accounts with our own experiences, gleaned on joint visits to the sites in 2022 and 2023. As their histories reveal, monuments are apt to be erased, moved or diminished, as the urban context changes around them, or as new understandings of historical characters and events emerge. Our discussion registers the wider political and cultural conditions within which memorials are created, installed and experienced, and how they generate what Closs StephensFootnote23 calls ‘forces of encounter’ that draw bodies together and apart at different times. Here, these memorials demonstrate the diverse ways in which the public have been invited to consider Batman’s legacy and how his presence and meaning in Melbourne’s landscape continues to change. Batman’s story has constituted an extraordinarily recurrent foundation myth in Melbourne for many decades, its key lineaments stabilized, reinforced and reiterated in many commemorative forms. Yet recent memorials remember John Batman otherwise.

Batman’s obelisk: a traditional nineteenth century memorial to a foundation myth

Following Batman’s unheralded death, his significance to the story of Melbourne was sidelined. Yet four decades later, a retrospective surge of desire to establish foundational myths for what had become ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ gathered force, and this was supplemented by compulsions to honour colonialist and nationalist figures as numerous memorials were installed across the city. The city’s extraordinary expansion fuelled by the wealth generated by the Victorian gold rush, AttwoodFootnote24 details, prompted the accumulation of romantic, heroic accounts that emphasized Batman’s critical role in founding the city. These legends drew on the aforementioned treaty that ceded the land to settlers and his oft-repeated claim that this was an ideal site for a settlement. Key governmental figures assigned Melbourne Old Cemetery, where Batman’s remains rested in an unknown, unmarked grave, as the site for a monument. As reported in The Argus (5/61882),Footnote25 the sponsors ‘deplored the fact that the remains of the founder of the city of Melbourne lay without any indication of the spot where they were buried’. Once they were discovered, an ‘obelisk of dressed bluestone’, paid for by public subscription, was erected in June 1882, over Batman’s remains, fashioned by local sculptor, J. W. Brown.

The obelisk design, a highly popular memorial form of the era, was shaped according to neo-classical Egyptian, Greek and Roman influences, underpinning ideological assertions that the British Empire historically chimed with these ancient empires. An inscription details Batman’s supposed founding of the city and concludes with the word ‘Circumspice’, an injunction to ‘look around’, implying that a gaze from the memorial disclosed the growing city that is his overarching legacy. A formal opening ceremony drew a ‘large gathering of old colonists and a numerous assemblage of other visitors’.Footnote26 A large Victorian ensign concealing the monument was uncovered as a band played the national anthem and a series of speeches evoking Batman’s supposed accomplishments followed.Footnote27 Similar statements about the significance of the Treaty and Batman’s identification of the riverside as an ideal location for a settlement would be reiterated through commemorative visual forms, ceremonies and historical accounts for decades to come.

Batman’s obelisk is not particularly distinguished or skilfully wrought. Yet it is archetypal in its colonial form and message, and as a monument to a ‘great man’, it joined the growing array of tributes to explorers, statesmen, royal personages and military figures that came to populate the urban landscape. However, in 1922, as the Queen Victoria Market was expanded and the old graveyard was closed, Batman’s remains were reinterred at the new Fawkner Cemetery beneath the Pioneer Memorial, which besides including an inscription to Batman, also commemorates Victoria’s first Lieutenant Governor La Trobe and colonial secretary William Lonsdale. The Batman obelisk was removed to the South Bank of the Yarra on Batman Avenue, so named in 1913.

Commemorations surged and waned around the obelisk over the next 50 years. In 1992, it was moved back to the original site, where in response to the changing political climate, the memorial was augmented by a council-organized inscription which read, ‘When the monument was erected in 1881, the colony considered that the Aboriginal people did not occupy land. It is now clear that prior to the colonization of Victoria, the land was inhabited and used by Aboriginal people’. Melbourne’s Aboriginal consultative group subsequently argued that this was too feeble a statement and in 2004, an alternative plaque was attached:

The City of Melbourne acknowledges that the historical events and perceptions referred to by this memorial are inaccurate. An apology is made to indigenous people and to the traditional owners of this land for the wrong beliefs of the past and the personal upset caused.

In 1994, following the rise in notions and policies devised to further ‘Reconciliation’, the Wurundjeri Tribal Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council staged a ceremony at the obelisk that foregrounded the treaty and its voiding by the Crown (Attwood, 2015). This spurred a call for compensation. In 1995, the Another View Walking Trail, sought to install a counter memorial, as we discuss below. More recently, HolsworthFootnote28 has called for what he regards as a ‘memorial to a genocidal colonial’ to be removed, on political and aesthetic grounds and because it is detached from its historical context. He further remarks that it has never been included on visitor tours or become a popular local meeting place. As contemporary academics, activists and residents reckon with the complex histories and legacies of settler colonialism, respectful reverence no longer surrounds Batman’s modest obelisk.

The Batman Stone and the stained-glass window at the Town Hall: memorial reiterations of the Batman myth

From the 1882 erection of the obelisk to the interwar decades, the lineaments of the Batman myth were critiqued only by a few dissenting writers, with the tale repeated in schoolbooks and in public histories, amidst a corresponding dearth of Aboriginal narratives.Footnote29 Written accounts were consolidated by publicly staged ceremonies, a range of artistic tributes and further memorials to provide material, symbolic and affective reminders of his significance to place. In 1925, following a campaign by the Historical Society of Victoria, the city council arranged for the iron Batman Stone, roughly 7 feet by 3 feet, to be embedded into the pavement at Flinders Street adjacent to the Customs House (now the Immigration Museum). As we subsequently discuss, towards the end of the twentieth century, this prominent marker became an object of increasing controversy, concluding with its removal.

In 1934, an extensive civic programme commemorated the centenary of the first settlement in Victoria, established at Portland, some 225 miles west of the city, and following this, the first European settlement at what would become Melbourne. Official ceremonies and populist celebrations generated an enhanced civic pride about the pioneers, most notably Batman.Footnote30 The festivities included sporting events, an air race, fairs, pageants - including one in which a float of Batman’s boat featured - agricultural shows, illuminated tableaux, a royal visit, the removal and reassembly of Cook’s Cottage from Great Ayton in North Yorkshire to Fitzroy Gardens, and the bedecking of the city in flags and festive lighting. These events were more emotionally expressive, populist and ludic than the sober unveiling of the Batman obelisk, and less oriented around the city’s elite.

In addition, a stained-glass triptych was installed on the first-floor foyer of the symbolically significant Town Hall. Stained glass memorialization stems from the tradition that commemorates the dead in medieval churches and later, to secular war memorials. Unlike other memorial forms, stained glass works radiate light and colour and while they lack the tactile qualities of stone and bronze, they dramatically lure the gaze. In modern as in medieval times, light resonates with metaphorical ‘concepts of clarity and opacity that functioned as primary dichotomies for both moral and ontological systems’, and these ‘translucent tapestries’ are ‘planes for storytelling’.Footnote31 Combining symbolic meaning and visual allure, radiant stained glass stands out from gloomy interiors to disseminate biblical episodes as well as local and national histories.

BremnerFootnote32 remarks that during the Victorian period, throughout the British Empire, stained glass was used in both religious and secular settings as part of a pan-imperial extension of Gothic revivalism. Renewed interest in the medium was also triggered by new techniques and materials. English managers, designers and artisans were repeatedly recruited, retaining a link in taste and style with the former colonial power. While bestowed with a sacred charisma generated through common ecclesiastic use, stained glass was also deployed to transmit and reinforce cultural values, including ‘civilizational advancement, material improvement, moral and spiritual edification, the pioneering impulse, and/or the appropriation and symbolic reassignment of local environments (such as non-European flora, fauna, and people)’ (ibid). These designs extended shared values and aesthetics beyond the colonial centre and fostered networks through which supplies, fashions and ideas were distributed.

The three stained glass windows in the Town Hall are mounted in front of light boxes; according to the City Collection siteFootnote33 the maker is unknown. The panel to the left imagines a romantic image of a standing Batman in a rowing boat, accompanied by three oarsmen and a partially clothed Aboriginal man holding a spear (). Surrounded by a flowering shrub in the foreground and leafy trees in the background – Batman’s mooted declaration that ‘This will be the place for a village’ is inscribed on a decorative inset immediately below the image. The middle window features the old city crest and motto, ‘Vires Acquirit Eundo’, translated as ‘We Gather Strength As We Go’, and the statement that ‘These Windows Commemorate the Centenary of the Founding of Melbourne’. The window on the right is dominated by an image of Melbourne in 1935, also framed by botanic effusion with its civic, ecclesiastical and corporate buildings implicitly representing the culmination of Batman’s vision. The symbolic trajectory from Batman’s treaty and arrival to the building of the modern city suggests civilisational, material and pioneering triumph as well as the harnessing of indigenous environments for ‘improvement’. This conforms to Bremner’sFootnote34 observation that in secular settings, stained glass designs frequently featured ‘some colonial foundation narrative or seminal figure (or figures) in the history of the place concerned’ through which the past was ‘translated into spectacle’Footnote35 as a means to cultivate a sense of shared citizenship.

Figure 2. 1935, First window in the 1935 stained-glass triptych, Melbourne Town Hall (photograph by authors)

Like the obelisk, the stained-glass triptych remains in situ and can be seen by all who enter the Town Hall, along with a 1934 portrait of Batman by William Beckwith. Though somewhat unheralded, it continues to reside at the heart of Melbourne’s political and symbolic power. Batman’s historical salience persists here, although the website detailing the portrait includes the statement that the ‘1930s were the high point of Batman’s historical reputation. He is now widely acknowledged for his shameful treatment of Aboriginal people, including charges of murder in Tasmania’.Footnote36

The windows exemplify how foundational myths can be rendered through a variety of memorial forms. It belongs to a wider memorial landscape in which the mythical story of Batman quietly endures, even though it has been decentred. Perhaps its aesthetic form, its less intrusive interior location and its official setting has ensured that this memorial has resisted critical scrutiny. It is a reminder of the 1930s celebratory atmosphere that included the Batman myth but is also a remnant of a larger settler colonial memoryscape that has partially disappeared and been supplemented by counter- and anti-memorial elements.

The Batman statue in Collins Street: a memorial out of time

As we have emphasized, the historic narrative of Batman served as a recurrent foundation myth in Melbourne for many decades, its key lineaments stabilized and reinforced through retelling in diverse material and discursive forms. Yet following World War 2, dissonant and alternative accounts emerged that began to undermine these dominant versions, some led by concerned white scholars who referred to his violent acts in the Black Wars of Tasmania. Rather differently, Indigenous activists recruited Batman to support their campaigns for wider political representation, echoing earlier narratives that regarded his treaty as recognizing Aboriginal rights over the land.Footnote37

In this context, it seems curious that the Liberal Party controlled City of Melbourne Council commissioned the installation of a statue of Batman, dedicated on 28 January 1979, by Stanley Hammond.Footnote38 Ironically, Hammond also created an adjacent statue of John Pascoe Fawkner, Batman’s rival as founder of Melbourne. His party had established a settlement near Melbourne’s current centre before Batman’s party returned to establish their dwelling place, and Fawkner repeatedly disparaged Batman’s character. The sculpture was situated on downtown Collins Street in the plaza of the now demolished National Mutual Building and stood on a low plinth. A bearded Batman was garbed in farming clothes: knee-length boots, a wide brimmed hat, necktie, work shirt and trousers. One foot was placed upon his swag, a rolled-up blanket, and he was signing a document, presumably the treaty, supported by his raised knee (). The work deviates from the bronze figures of an earlier era who grandly stand aloft on high plinths, unreachable and gazing out impassively. Rather, it epitomizes the trend for post-war figurative memorials to be sited at ground level. Batman thus joined the plethora of sporting icons, popular musicians, comics and actors who have supplemented Melbourne’s late 19th and early twentieth century marble and bronze figures commemorated for their military, exploratory or political accomplishments.

Though not positioned in a ‘traditional’ heroic pose, art critics, notably Holsworth,Footnote39 considered this statue of Batman to be ‘uninspiring’ and ‘old fashioned’, signifying that late 1970s Melbourne remained ‘introspective, isolationist and conservative’. Yet things were to change as the 1980s and 90s spawned more challenging approaches by Aboriginal artists and activists. Narratives focused on the settler-colonial dispossession of Indigenous land, pointed out the inequities of Batman’s treaty and foregrounded stories in which Kulin histories and culture were pre-eminent. Moves to undermine the basis of the legal fictions that justified settler possession and displace the central myth that had surrounded Batman culminated in October 1991, when a crowd of Aboriginal protestors gathered around the statue, signifying a particular historical turn to activist engagements with memorial statues. One ripped up a copy of the original treaty before a mock trial was staged that accused Batman of war crimes perpetrated in Tasmania and Victoria: theft, trespass, rape and genocide. As each charge was read out, the assembled throng shouted ‘guilty!’. A sign for each crime was placed around the statue’s neck and the hands coloured with red tape to signify the bloodshed for which Batman was responsible. White participants were asked to sign an alternative treaty in which reparations for land theft were foremost. This theatrical protest prefigured a later intervention at the memorial as we discuss below.

Subsequently, there were calls for the statue’s removal, including by artist Ben Quilty, who describes Batman as a ‘mass murderer’ that ‘makes the American Confederates look friendly’, although this opinion is opposed by Aboriginal historian and tour guide, Dean Stewart, who echoes recent debates that such abject colonial histories need to be remembered through the retention of settler-colonial memorials.Footnote40 In any case, both the Batman and Fawkner statues were removed in 2017 to accommodate the high-rise office development of the Collins Arch Project; their re-installation seems unlikely. Indeed, MillarFootnote41 reports that a City Council spokesperson asserted that the statues would not be purchased or received as a gift from the developers since they were outmoded forms: ‘globally contemporary art practice has moved away from figurative bronze statues of individual historical figures’. HolsworthFootnote42 contends that following its removal, there has been ‘no evidence of any loss of knowledge of history nor any sanitisation of history’. Repudiating populist and conservative concerns about the effects of its ejection, he concludes, ‘it appears that people are enjoying the absence of Batman’.

The removal of Batman’s statue on Collins Street marks a significant change in council policies towards commemoration that acknowledges his contested legacy and welcomes particular Indigenous memorial practices. However, this has also incorporated an official ambivalence towards more radical political commemorative statements about historical violence and dispossession and the ongoing denial of territorial rights, as we now discuss.

Another View Walking Trail and Lie of the Land: counter-memorials

The systematic reiteration of the Batman myth discursively, artistically and materially has perpetuated a settler-colonial forgetting of the place’s original inhabitants, yet this somewhat singular foundational story has been impossible to sustain over the past four decades. The outmoded political and cultural values that inhered in the 1979 statue of Batman were widely critiqued in the 1990s and after, as Aboriginal modes of commemoration emerged to mark indigenous presence on Melbourne. A time of reckoning for the uncritical commemoration of Batman had duly arrived.

While informal demonstrations such as the mock trial cited above displayed changing moods amongst the Kulin people, the advent of the national Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation Act of 1991 encouraged official strategies to support the installation of Indigenous forms of commemoration in Melbourne that were regarded as necessary steps in the coming into representation of Kulin presence. In the following two cases, these have involved the creation of counter-memorials. The first example is the 1995 City Council funded Another View Walking Trail through central Melbourne, intended to reveal a previously ‘hidden’ Aboriginal history.Footnote43 As MorganFootnote44 details, the trail was planned to directly challenge ‘the way that history is inscribed in architecture and urban design’, by inserting Aboriginal historical interpretations, stories, characters and events in readings and in artworks. Several of the trail’s components aligned with Stevens et al.’sFootnote45 depiction of counter-memorials that explicitly critique existing memorials in part by way of proximate siting.

Incorporating seventeen inner city sites at which counterpoints ‘to the city’s historical markers, including artworks, installations, plaques and stories’Footnote46 were devised, the scheme sought to redress previous exclusions. The trail was designed through a collaboration between Gunnai artist Ray Thomas, non-Aboriginal artist Megan Evans and Woorabinda/Berigaba researcher Robert Mate Mate. They explicitly aimed to foreground sites of Aboriginal resistance, spirituality and history and reveal ‘alternative histories of the city that are obscured and concealed by buildings, statues and public spaces and draws on the silences implicit in existent sites to force memory of the often-violent histories they disavow’.Footnote47 They further asserted that ‘Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians have a shared history, and that in order to have a shared future we need to acknowledge successes and failures from the past in our contemporary reading of history’.

However, while some of the resultant counter-memorials were permitted, five planned installations were withdrawn by the council due to their perceived confrontational nature. Counter-memorials were devised that were to be sited at three of the Batman memorials discussed above. One, a brass map displaying sites of Aboriginal massacres in Victoria was to have been placed close to the 1882 Batman obelisk, but was regarded by the council as too inflammatory, and inimical to the spirit of reconciliation. Another work was successfully installed next to the 1979 Batman Statue on Collins Street: Aboriginal wooden poles were inscribed with the blood lines of both Indigenous and settler colonialists, and more provocatively, with images of bones to represent the deleterious effects of colonialism on Indigenous people, effects in which Batman was complicit. The poles gradually disappeared from the site and are no longer present, their upkeep having been neglected following persistent disquiet within the local authority, an unease that ultimately led to the decommissioning of the trail in 2000. One vestige of the trail remains: a pavement mosaic that overtly responds to the Batman Stone once installed on Flinders Street (see ). It commemorates a silhouette of a Wurundjeri man, Simon, who threatened to kill the first settlers in 1835,Footnote48 although this cannot be discerned by visual scrutiny and without context, and also includes horseshoe motifs to represent the Melbourne Cup race originally staged near this location.

Figure 4. Ray Thomas, 1995, Plaque formerly adjacent to the now removed Batman Stone, a remnant from the now decommissioned Another View Walking Trail.

As MorganFootnote49 states, the ‘deterioration of the trail gives the walker a further layer of meaning to explore, such as sanctioned and repressed histories’ and the absence of what was formerly disclosed. While three remaining brass inlay works wrought into bluestone paving easily go unnoticed, they constitute lingering traces of another way of remembering place. However, their potency relies upon their relation to these earlier memorials; now these are absent, their critical force wanes. Moreover, as WareFootnote50 observes, while such counter-memorials critically addressed the memorials that they were strategically placed alongside, they ‘lacked the cohesiveness of a memorial designed to be open to multiple readings’, as well as the polysemy and disorienting effects that anti-memorials might conjure up.

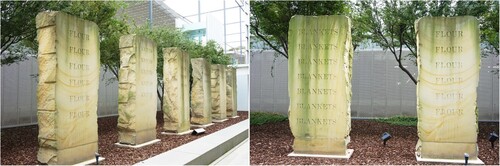

A more powerful riposte to the uncritical commemoration of Batman, an overt response to the silencing of historical events under settler colonialism, is Lie of the Land, designed by Badtjala visual artist Fiona Foley and sound artist Chris Knowles. The work was commissioned by the City of Melbourne to mark the Australian Reconciliation Convention held in the city in 1997 and commemorate the 30th anniversary of the 1967 referendum in which the constitutional status of Indigenous Australians was amended. It was initially situated directly in front of the main entrance to the Town Hall, a few metres away from the stained-glass commemoration of Batman, and acted to interrogate the history of this highly symbolic building. The work comprises seven three-metre-high sandstone pillars, each inscribed with an item listed in Batman’s 1835 Treaty with the Wurundjeri people: ‘looking glasses’, ‘knives’, ‘tomahawks’, ‘beads’, ‘scissors’, ‘flour’ and ‘blankets’, with slabs etched with successively higher numbers of these words (see (a,b)). The etched tombstone-like pillars powerfully articulate the historical fate of many Indigenous people, conveying an implacable, melancholic aura that summons up the death toll following European colonization. Knowles’ accompanying soundscape includes a reading of Batman's entry on the controversial deal in Woiwurrung, readings in several other languages that whisper the names of the items Batman supposedly exchanged for land, and native bird sounds.

Figure 5. Left: Fiona Foley and Chris Knowles, The Lie of the Land, 1998, Courtyard in Melbourne Museum; right: Detail from Lie of the Land.

Although not directly addressing any specific existing memorial in its present location, at the Melbourne Museum the work is implicitly a powerful counter-memorial to older modes of commemoration that remember Batman. Foley explicitly refers to the political necessity of supplementing and challenging such authoritative forms: ‘How do we reconcile an exchange of functional and non-functional goods in return for 60,000 acres of land and a yearly rent that was not honoured? As the history was written by the victors it is only now that the silent history of the indigenous populations is given a voice’.Footnote51

Though always envisioned as a temporary sculpture, Lie of the Land remained in its city centre location for a couple of months longer than intended following entreaties by Indigenous parties, and was subsequently purchased as a permanent work by the council. Yet its political force as a rebuke to settler-colonial power was drastically reduced when it was moved from the Town Hall to its present location in a steep-walled, quiet basement courtyard of the Melbourne Museum. Despite this, when we visited its inconspicuous setting, Lie of the Land radiated an undisturbed material presence, and the sound recordings were not silenced by the roar of traffic, though the screeches of skateboards above on the wide, paved precinct resounded loudly at times. Austere, imposing and impassive, the material inequities of Batman’s treaty are solemnly recorded, rebuking the celebratory narratives spun around the city’s foundation. It remains an effective counter-memorial.

Lie of the Land conveys a clear political message in sculptural form. Counter-memorial approaches such as this may be somewhat singular in offering directly oppositional challenges to reified memorial forms; critiques that they restrict interpretation and complexity by construing a binary relationship with another memorial object under critique seem apposite. Nonetheless, we argue that Lie of the Land offers a powerful, unambiguous and clear rebuke to the reiterative fixings perpetrated by previous memorials to John Batman scattered throughout central Melbourne.

Chimney in Store (Towards a Monument to Batman’s Treaty): an anti-memorial

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, a range of installations has highlighted the continued presence of Aboriginal people in Melbourne, supplementing traditional memorials and diversifying commemorative forms. While official memorialization has typically erased Aboriginal existence,Footnote52 the widening of political and aesthetic modes of commemoration, governmental, artist-led and activist, has encouraged creative memorials to Indigenous figures, practices, myths and tragedies. In this section, we identify a few of the most prominent.

Birrarung Marr, a central riverside park created in 2001, incorporates diverse Indigenous forms, including a winding, eel-shaped path, a semi-circle of shields representing each of the five groups of the Kulin Nation, and a meeting place bordered by ten bluestone boulders carved with animal petroglyphs. A realist sculptural memorial created by Louis Lauman and erected in Parliament Gardens in 2007 commemorates the prominent Indigenous rights activists Doug and Gladys Nicholls. Rather differently, inner-suburban Footscray’s shopping centre accommodates the bluestone sculptural form of a giant, buried Welcome Bowl, or Wominjeka Tarnuk Yooroom. Created in 2013 by Kulin artists Maree Clarke and Vicki Couzens, this resembles a traditional receptacle for burning grasses that welcomes all inhabitants of the city, old and new, commemorating the Aboriginal history of the place and the migrants who have made Footscray home. A 2016 conceptual sculpture created by Wiradjuri artist, Brook Andrew, and Water Trent, Standing by Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, commemorates the site of the execution of two nineteenth century Aboriginal men who resisted colonial rules. Such installations are fashioning a more inclusive memorial landscape that transcends the reified monuments that typically honour male colonialists and nationalists.

Yet as with all commemorative forms, those that remember Aboriginal figures, events and places are created by a variety of non-Indigenous and Indigenous individuals and groups who are motivated according to diverse perspectives, aesthetic preferences and intentions. In Melbourne, such incentives have revolved around political ideas about justice, historical redress, civic responsibility and cultural presence, but have also more dubiously been motivated by commercial interests, most glaringly by the 2015 portrayal of the face of nineteenth century Aboriginal activist, William Barak (1824–1903), on the facade of a large residential apartment tower.

Porter et al.Footnote53 exemplify how this particular commemorative form involves the ongoing transformation of Wurundjeri land into property, thereby reinforcing settler-colonial understandings of land as that which is possessed while simultaneously ‘fuelling specific forms of remembering, forgetting and practices of belonging, as a public imagination’. This involves a move towards the removal of settler colonial guilt by ostensibly celebrating heritage while ignoring the violent historical dispossession that made the contemporary primacy of property possible, along with the laws, land speculation, planning and forms of governance that sustain settler colonial space.

In addition to these commemorative innovations, in 1997, the formerly eastern part of Batman Park, Enterprize Park, was renamed after the vessel organized by Fawkner that brought the first settlers from Tasmania to land nearby. This is further commemorated by the riverside Enterprize Landing Memorial, installed in 1985, an anchor, and a mast atop which is raised the City flag each Melbourne Day. In contrast, just beyond these symbols is the city council funded Scar: A Stolen Vision, comprising an eclectic collection of 30 river red gum poles carved by nine Aboriginal artists,Footnote54 some depicting the cruelty and violence of colonial strategies.

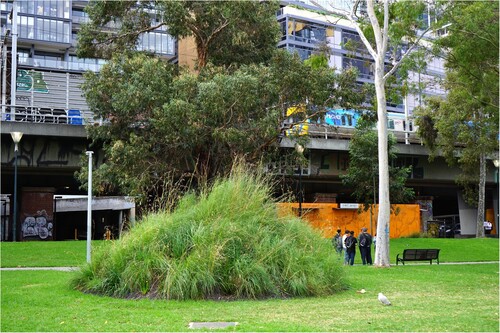

Adding to this dense, complex memorial landscape, a few hundred metres away is Tom Nicholson’s artwork Chimney in Store (Towards a Monument to Batman’s Treaty) in Batman Park. Created in 2021 (see ) and having followed a significant formative period of artistic experimentation, extensive historical research and widespread consultation, including with Aboriginal collaborators, we consider this to be an anti-memorial. Commissioned by the City of Melbourne and the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, the work was inspired by the first European chimney built in the city in 1836 for John Batman by escaped convict William Buckley, a skilled bricklayer who had lived with Aboriginal people for 32 years. Chimney in Store consists of a pile of 3,520 used bricks, the number required to construct a similar chimney. They are entirely covered with earth and native grasses to form a small hillock that rises from the surrounding lawns. Importantly, the bricks were collected from an area some 50 kilometres northeast of Melbourne, and potentially include some that were recycled in the construction of Healesville from the demolished buildings of Coranderrk. This once thriving Indigenous mission station, founded in 1863, was an important centre of farming, brickmaking and fishing, and a hub of political advocacy and self-organization, and was forcibly dismantled under expansionist settler colonial land systems and its inhabitants dispersed in 1924.Footnote55

Figure 6. Tom Nicholson, 2021, Chimney in Store (Towards a Monument to Batman’s Treaty), Batman Park, Melbourne.

On the ground near the Batman Park artwork is a single bronze plaque inscribed with the following text:

On 26 April 2021, 3,520 bricks are transported here from the upper reaches of the Birrarung/Yarra River, Wurundjeri Country. These bricks are stored here for a future monument: a free-standing chimney encased in thousands of words in plaques. This vertical form reprises this city’s first European chimney, built by William Buckley for John Batman. It is a monument to Batman’s treaty, the confected document Batman claims he signed with Wurundjeri elders in 1835. These bricks here – towards an obelisk that is also a hearth for a treaty that triggers an invasion – become this store.

- Buckley’s close affiliation with a group of Wathaurung people with whom he lived for many years.

- How the smoke from an Indigenous fire in Tasmania that chimes with the chimney’s purpose revealed Aboriginal presence to a raiding party led by Batman, allowing his party to perpetrate a massacre.

- An Indigenous Tasmanian boy held captive by Batman’s party following a similar raid who escaped at night by climbing up the chimney of the house in which he was held.

- The parallel memorial recently installed at the dismantled Indigenous settlement of Coranderrk, discussed below.

This compilation of tales on the website further reinforces Tello’sFootnote58 point that commemoration might move beyond a dialectic version of historical narrative and instead offer heterogenous and possible interpretations. Critically, this can be greatly extended by the plethora of accounts and interpretations that can be transmitted online.Footnote59 Indeed, Drozdzewski et al.Footnote60 describe how this signifies a progressive trend whereby geographies of commemoration are increasingly ‘neither wholly material nor digital, but as connected and encountered through the confluence of digitality that shapes, embodies and permeates our experiential worlds’.

Importantly, besides expanding into digital space, Chimney in Store’s resonance extends physically to a companion work installed in 2019 that shares formal and conceptual elements, untitled (seven monuments),Footnote61 created by Wurundjeri elder Auntie Joy Murphy Wandin, Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones and Tom Nicholson. Seven squat brick forms, composed from the same sources as those supplied to Chimney in Store, mark the 1866 boundaries of Coranderrk at sites that range from suburb to bush, roadside to country park. Each monument features an upturned flagpole, its hollow tube visible on the surface. This resonates with the buried bricks in Batman Park in inverting the overt claims of possession deployed through marking symbolic memorial sites with flags. Plaques are affixed to each of the four faces of the brick footings, one relating generic details about the work, a second describing historic stages in the growth and decline of Coranderrk, a third featuring key historical figures in the settlement’s story, and the fourth poetically describing the flowers, animals and birds that characterize one of the Wurundjeri’s seven annual seasons. Once more, no singular character or event predominates ().

Figure 7. Two Monuments from untitled (seven monuments), Corranderk Boundary, Auntie Joy Murphy Wandin, Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones and Tom Nicholson.

In forging geographical relationships with other commemorative forms, Chimney in Store belongs to a memorial space that is dense in Melbourne but also extends beyond the city into a wider historical landscape of violent settler colonialism, aligning with other memories of dispossession. The ambiguous buried form of Chimney in Store is not a memorial that tidies up history, or indeed remains in the past. Instead, it offers multiple interpretations at once, and purposefully emphasizes the notion of futurity that inheres in any memorial. Its form, a mound unrecognizable as a conventional monument, questions outmoded commemorative norms and suggests that perhaps no alternative convention can replace them. By remaining a purely potential memorial, the artwork draws the visitor into a speculative, reflective encounter with history and futurity. We might surmise about what form such a chimney might take. What did the original chimney look like, and should any future memorial replicate this? Most pertinently, the visible absence of the usual material components requires us to ask whether such a memorial should actually ever be constructed given the controversies that surround the contested figure of Batman.

The website for the installation writes that it is ‘poised between a final repudiation of the monument (and its burial, out of site); an enduring persistence of the monument (where the spectre of the monument becomes its own topography) or its deferral into subterranean storage’.Footnote62 This hints at how Chimney in Store looks forward to a future in which all memorials are ultimately subject to entropic forces and slide into oblivion, perhaps leaving depressions and mounds in the landscape. Appropriately, the introduction of native plants suggests that these will eventually reclaim the memorial. In this sense, the work resonates with Robert Smithson’sFootnote63 notion of ‘ruins in reverse’ that did not gradually become ruinous having been built but rather foretold of their future ruination during their construction, prefiguring their inevitable fate. The prematurely ruinous structure of Chimney in Store further emphasizes that building a new memorial to Batman in the present and in the future would be misguided since such a project would already be based on a ruined idea. In any case, indecipherability and entropy will inescapably render all such objects obsolescent vestiges. In seeking to dissolve dominant symbolic, historical and narrative impositions by adopting formal and discursive approaches that mobilize multiple references and overwhelm desires to inscribe singular meanings in space, as an anti-memorial, Chimney in Store underlines the inevitable eventual demise of all memorials. Its setting in a quiet, green swathe of open space adjacent to the River Birrarung offers a conducive atmosphere to thoughtful, reflective interactions with the memorial and the multiplicities, absences, presences and questions that it conjures.

The formal, textual and enigmatic qualities of Chimney in Store highlight that memorials always emerge in particular cultural and historical contexts, indicating specifically how the ideologies, identities and public practices that have resulted in the proliferation of obelisks, plaques, statues, stained-glass windows, eponymous parks, streets and districts created to commemorate Batman over the past 140 years have endured, disappeared and shifted.

Counter-memorials such as Lie of the Land typically contest the hegemonic force of these traditional monuments by providing commemorative forms that honour the repressed, the excluded and those who resist, and by directly critiquing particular memorials, as with the installations of Another View Walking Trail. By contrast, an anti-memorial such as Chimney in Store critically interrogates Batman’s repeated commemoration in multiple ways, but not in dialectical opposition to any single memorial. Here we draw on Tello’sFootnote64 notion of ‘counter memories’ that are constitutive of ‘multiple histories being held together, or networked’, attuned to heterogeneity and excess, and characterized by diverse styles, subjects, geographies and histories. These manifold reference points and connections offer numerous perspectives, recalibrating understandings while foregrounding constant shifts in meaning and experience. A memorial such as Chimney in Store assembles ‘a constellation of subjectivities to disrupt binaries, dualisms, universalisms and institute total difference’. In incorporating an array of complex stories that decentres the pre-eminence of one historical narrative, the memorial reveals the historical context in which Batman emerged as complex, uncertain and replete with diverse interests, incidents and actors.

Moreover, Tello argues,Footnote65 such memorials appositely resonate with the contemporary global city, a heterogenous realm in which ‘the uneven co-presence of the diasporic, the settler-colonialist, the indigenous and the stateless’ prevails, making claims to singular histories, experiences and memories ludicrous. The work ranges across text, earth, brick and digital forms, exploding both the material form and the discursive coherence of the memorial. The companion memorial untitled (seven monuments) geographically extends the ideas, forms and stories of Chimney in Store, and the online artist’s book expands the reach of Batman commemoration in virtual space, further extending the dense spatial links constituted by successive memorials to Batman and settler colonial monuments throughout Melbourne. It moves us far beyond a contained memorial form, like an obelisk or even a sound work, stirring imaginations and challenging longstanding narratives.

Conclusion

The 2022 election of a national government in Australia committed to the constitutional recognition of First Nations people has advanced a reckoning with the violence of settler colonialism. This has spurred moves to reflect growing acknowledgement of the ongoing violence of colonialism and the importance of official events, monuments and place names in promulgating this. As part of these accelerating changes, recent developments are recontextualising existing fixtures and place names that mark Batman’s legacy. In Melbourne suburb Northcote, Batman Park was renamed Gumbri Park by Darebin Council in 2018, and in 2019, the inner city federal electoral seat of Batman was renamed after Indigenous rights campaigner William Cooper. Batman Avenue remains but it is now situated alongside Birrarung Mar and the features installed there inspired by Aboriginal cultures and histories. According to Pinto,Footnote66 these interventions ‘quietly undermine’ the old road. Over a longer period, most of the Batman memorials we discuss here have had their meanings and functions substantially challenged since their creation: the 1882 obelisk lingers in a marginal spot, with some calling for its removal;Footnote67 the Batman Stone and the statue on Collins Street have been removed. In contrast, the 1936 stained-glass image of Batman is still unashamedly displayed in the Town Hall, consolidating Batman’s long connection to elite geographies of power. Though a seductive foundational narrative lingers, overall, it has been decentred through the work of diverse groups including councils, elite citizens, artists and Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal activists, motivated by divergent approaches at different times, and the creation of a wide variety of commemorative forms.

These recent memorials have sought to redress the former erasure of Indigenous presence and history. However, as Tuck and YangFootnote68 emphasize, a focus on a purely symbolic politics, including of commemoration, can act to domesticate decolonization while underlining settler sovereignty and neglecting to recognize ongoing historical injustice. Such practices ‘attempt to reconcile settler guilt and complicity, and rescue settler futurity’ without addressing fundamental questions about land redistribution and sovereignty. The ongoing ‘profound epistemic, ontological, cosmological violence’ of land dispossession and capitalist exploitation continues as before.Footnote69 Moreover, Tuck and Yang claim, the granting of the presence of memorials to Indigenous presence and history at a metaphorical and figurative level fosters an illusory innocence that detaches settler colonial identities from historical violence, further relieving ‘the settler of feelings of guilt or responsibility without giving up land or power or privilege’.Footnote70 The most egregious example of this is the aforementioned giant portrait of William Barak on the large apartment block critiqued by Porter et al.;Footnote71 a cynical view might suggest that the establishment of all recent memorials that acknowledge Aboriginal history and presence are similarly complicit in contributing to settler colonial manoeuvres that claim innocence while seeming to redress invisibilization.

Such negative inferences might also be stoked by official decisions to debar memorial forms deemed to exceed political acceptability. As the constraints placed on selective elements of the Another Way Walking Trail demonstrate, memorials that sought to disclose violent settler colonial massacres were disallowed by the local state on the grounds that they were too confrontational. Moreover, according to Pinto,Footnote72 memorials created by Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists remain on the margins of Melbourne’s central axes. The removal of Lie of the Land from its formerly central location to an extremely peripheral setting most dramatically exemplifies such a spatial politics.

However, while such arguments are powerful, they may seem unduly static and pessimistic, denying the potential for commemoration to make important political interventions in civic space that can contribute to changing political values and public moods. In Melbourne, memorialization is, as we have shown throughout this paper, a dynamic and volatile process and currently, commemorative practices and meanings are continuously changing according to shifting spatial, aesthetic and political contexts, with existing memorials being reinterpreted in different ways. The recent emergence of memorials that restore and reassert the presence of Aboriginal Australians has introduced inventive forms that critique traditional monuments and instantiate new ways of remembering. They seek to undergird the city as an Indigenous place both in the past and into the future and contribute to the emergence of an ever-more complex, multivalent memorial landscape in which forms of commemoration afford greater prominence to subaltern groups, thereby registering the shifting complexities of cultural and political power across the city.

More broadly, the feverish atmospheres that currently surround monuments, most notably in post-slavery and postcolonial contexts, have prompted demands to topple or destroy memorials, relocate them to storerooms, marginal sites or museums, or reinterpret and recontextualize them. In the particular settings of Australian settler colonialism, such debates are especially charged. Rose Redwood et al.Footnote73 contend that geographers can explore these issues by examining the tensions between those who seek to maintain the political infrastructures of universalizing memorial forms and those who champion the very different world-making practices and ideals that inhere in pluriversal memoryscapes. In Melbourne, commemorations to the highly controversial John Batman, have for decades been dominated by reified, repetitive discourses that have sought to ideologically fix settler colonial meaning in space. But in recent decades, these monuments have been challenged by counter-memorials and anti-memorials, forms that offer potent responses to commemorative stasis in different ways. Inspired by creative experimentation and historical research, they interrogate the outmoded values that sustain older memorials while offering inventive, alternative approaches to specific objects of memorialization and to the future of commemoration. Their distinctiveness can stimulate an awareness of the manifold possibilities that might be adopted in advancing a more progressive, more inclusive, imaginative and fluid politics of public remembering, which in turn, can begin to inform discussion about wider political inequities.

As a counter-memorial, Lie of the Land repudiates all previous memorials to Batman by transmitting a blatant but plaintive statement that refuses the forgetting of the depredations wrought by settler-colonialism upon Indigenous communities. The anti-memorial of Chimney in Store goes further, deconstructing the notion of future-oriented memorialization in its form as a grassy mound that renounces any aspirations towards permanence. The installation will be engulfed by botanical fecundity, subside and become ruined. Furthermore, by means of its digital presence, Chimney in Store can feature multiple stories, refusing to represent settler colonialism and decolonization as anything other than complex and multiple. This narrative excess resonates with Tuck and Yang’sFootnote74 claim that ‘lasting solidarities may be elusive, even undesirable’, a suggestion that decolonization should avoid dialectical relationships while recognizing the incommensurability of diverse perspectives. Finally, a critical focus on the land dispossession perpetrated by settler colonialism is integral to Chimney in Store through its inextricable link to its companion memorial, a work that remembers the baleful dispossession of the Indigenous inhabitants of Corranderk over several decades. Such malign inequities chime with those perpetrated by Batman but are foregrounded, not concealed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tim Edensor

Tim Edensor is Professor of Social and Cultural Geography at the Institute of Place Management, Manchester Metropolitan University. He is the author of Tourists at the Taj (1998), National Identity, Popular Culture and Everyday Life (2002), Industrial Ruins: Space, Aesthetics and Materiality (2005), From Light to Dark: Daylight, Illumination and Gloom (2017), Stone: Stories of Urban Materiality (2020) and Landscape, Materiality and Heritage: An Object Biography (2022). He is editor of Geographies of Rhythm (2010), and co-editor of The Routledge Handbook of Place (2020) and Rethinking Darkness: Cultures, Histories, Practices (2020).

Shanti Sumartojo

Shanti Sumartojo is Associate Professor of Design Research at Monash University in the Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture and a member of the Emerging Technologies Research Lab. Her research investigates how people experience and understand their surroundings, particularly in shared, public and urban spaces. She is a co-author of Commemoration in a Digital World (2021, with Danielle Drozdzewski and Emma Waterton).

Notes

1 Sarah Pinto, Places of Reconciliation: Commemorating Indigenous History in the Heart of Melbourne, Melbourne: Melbourne University, 2021, p 14.

2 See Alistair Campbell, John Batman and the Aborigines, Malmesbury: Kibble Books, 1987.

3 Bain Attwood, Possession: Batman’s Treaty and the Matter of History, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2015.

4 Nicholas Clements, ‘The Truth About John Batman: Melbourne’s Founder and “Murderer of the Blacks”’, The Conversation, 13 May 2011, https://theconversation.com/the-truth-about-john-batman-melbournes-founder-and-murderer-of-the-blacks-1025 (accessed 11 October 2022).

5 Jeff Sparrow and Jill Sparrow, Radical Melbourne, Melbourne: Vulgar Press, 2001.

6 Sabine Marschall, Landscape of Memory: Commemorative Monuments, Memorials and Public Statuary in Post-Apartheid South Africa, Leiden: Brill, 2009.

7 Mark Holsworth, Sculptures of Melbourne, Melbourne: Melbourne Books, 2015.

8 Libby Porter, Sue Jackson and Louise Johnson, ‘Remaking Imperial Power in the City: The Case of the William Barak Building, Melbourne’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(6), 2019, pp 1119–1137.

9 Owen Dwyer, ‘Symbolic Accretion and Commemoration’, Social and Cultural Geography, 5(3), 2004, pp 419–435, p 421.

10 Tim Edensor, ‘The Haunting Presence of Commemorative Statues’, Ephemera, 19(1), 2019, pp 53–76.

11 Shanti Sumartojo, ‘Local Complications: Anzac Commemoration, Education and Tourism at Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance’, in James Wallis and David Harvey (eds), Commemorative Spaces of the First World War: Historical Geographies at the Centenary, London: Routledge, 2017, pp 156–172.

12 Madeleine Shanahan and Brian Shanahan, ‘Commemorating Melbourne’s Past: Constructing and Contesting Space, Time and Public Memory in Contemporary Parkscapes’, in L McAtackney and K Ryzewski (eds), Contemporary Archaeology and the City: Creativity, Ruination, and Political Action, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

13 David Atkinson, ‘The Heritage of Mundane Places’, in B Graham and P Howard (eds), The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, 2008, pp 381–396, p 381.

14 Atkinson, ‘The Heritage of Mundane Places’, p 385.

15 Quentin Stevens and Shanti Sumartojo, ‘Introduction: Commemoration and Public Space’, Landscape Review, 15(2), 2015, pp 2–6.

16 Tim Edensor, Stone: Stories of Urban Materiality, London: Palgrave, 2020.

17 Tim Edensor and Meg Mundell, ‘Enigmatic Objects and Playful Provocations: The Mysterious Case of Golden Head’, Social and Cultural Geography, 24(6), 2021, pp 891–911, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2021.1977994.

18 David Wright, ‘“One of Our Own”: Statues of Comedians, Popular Culture, and Nostalgia in English Towns’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, 2022, p 15, https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494221126547.

19 Iain Robertson, Heritage from Below: Heritage, Culture and Identity, London: Routledge, 2006, p 10.

20 Shanti Sumartojo, ‘Memorials and State Sponsored History’, in B Bevernage and N Wouters (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of State Sponsored History After 1945, London, Palgrave Macmilan, 2018, pp 449–476, p 455.

21 SueAnne Ware, ‘Contemporary Anti-memorials and National Identity in the Victorian Landscape’, Journal of Australian Studies, 28(81), 2004, pp 121–133, p 122.

22 Veronica Tello, ‘Counter-Memory and and–and: Aesthetics and Temporalities for Living Together’, Memory Studies, 15(2), 2022, pp 390–401, p 190.

23 Angharad Closs Stephens, National Affects: The Everyday Atmospheres of Being Political, London: Bloomsbury, 2022.

24 Attwood, Possession.

25 The Argus (5/6/1882) ‘The Batman Memorial’.

26 Argus (5/6/1882).

27 Attwood, Possession.

28 Mark Holsworth, ‘The John Batman Memorial’, Black Mark: Melbourne Art and Culture Critic, https://melbourneartcritic.wordpress.com/2020/10/17/the-john-batman-memorial/?preview_id=8142&preview_nonce=b55c3cbc58&preview=true (accessed 11 January 2023).

29 Attwood, Possession.

30 Shane Carmody, ‘John Batman’s Place in the Village’, The La Trobe Journal, no (80), 2007, pp 85–102.

31 Virgina Raguin, Stained Glass: From its Origins to the Present, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003, p 13.

32 G A Bremner, ‘Colonial Themes in Stained Glass, Home and Abroad: A Visual Survey’, 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, no (30), 2020, pp 1–23, p 1, https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.2900 (accessed 28 January 2023).

33 Melbourne City Collection (a) (n.d.), https://citycollection.melbourne.vic.gov.au/centenary-of-melbourne-windows/ (accessed 14 April 2023).

34 Bremner, ‘Colonial Themes’, p 4.

35 Bremner, ‘Colonial Themes’, p 5.

36 Melbourne City Collection (b) (n.d.), https://citycollection.melbourne.vic.gov.au/portrait-of-john-batman/ (accessed 14 April 2023).

37 Attwood, Possession.

38 Monument Australia (n.d.), ‘John Batman’, https://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/people/settlement/display/32372-john-batman) (accessed 13 December 2022).

39 Holsworth, Sculptures of Melbourne, p 68.

40 Joe Hinchcliffe, ‘Call to Remove Statue of John Batman, “Founder of Melbourne”, over Role in Indigenous Killings’, The Age, 26 August 2017, https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/call-to-remove-statue-of-john-batman-founder-of-melbourne-over-role-in-indigenous-killings-20170826-gy4snc.html (accessed 20 January 2023).

41 Benjamin Millar, ‘Statue of Limitations: No Place in the City for Men we’d Rather Forget’, The Age, 18 September 2018, https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/statue-of-limitations-no-place-to-call-home-for-two-old-green-men-20180916-p5045d.html (accessed 11 January 2022).

42 Mark Holsworth, ‘The Absence of Batman’, Black Mark: Melbourne Art and Culture Critic, 2022, https://melbourneartcritic.wordpress.com/tag/john-batman/ (accessed 11 January 2023).

43 Another View Walking Trail, 1995, https://koorieheritagetrust.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Another-View-Walking-Trail.pdf (accessed 12 January 2020).

44 Fionnula Morgan, ‘What Lies Beneath: Reading Melbourne’s CBD Through “The Another View Walking Trail”’, PAN: Philosophy, Activism, Nature, 12, 2016, pp 69–80, p 70.

45 Quentin Stevens, Karen Franck and Ruth Fazakerley, ‘Counter-Monuments: The Anti-Monumental and the Dialogic’, The Journal of Architecture, 23(5), 2018, pp 718–739.

46 Pinto, Places of Reconciliation, p 199.

47 Morgan, ‘What Lies Beneath’, pp 70–71.

48 Carmody, ‘Batman’s Place’.

49 Morgan, ‘What Lies Beneath’, p 74.

50 Ware, Contemporary Counter Memorials’, p 123.

51 Cited in Carmody, ‘Batman’s Place’, p 98.

52 Pinto, Places of Reconciliation.

53 Porter, Jackson and Johnson, ‘Remaking Imperial Power’, p 1123.

54 See Pinto, Places of Reconciliation, for details.

55 Giodanni Nanni and Alison James, Coranderrk: We will Show the Country, Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2013.

56 Acca, Chimney in Store (Towards a Monument to Batman’s Treaty), 2022, https://acca.melbourne/exhibition/tom-nicholson-chimney-in-store/ (accessed 28 October 2022).

57 Tom Nicholson, Artist’s Book for Chimney in Store (Towards a Monument to Batman’s Treaty), 2021, https://chimney-in-store.acca.melbourne (accessed 27 October 2022).

58 Tello, ‘Counter-Memory’.

59 Sam Merrill, Shanti Sumartojo, Angharad Closs Stephens and Martin Coward, ‘Togetherness After Terror: The More or Less Digital Commemorative Public Atmospheres of the Manchester Arena Bombing’s First Anniversary’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 38(3), 2020, pp 546–566.

60 Danielle Drozdzewski, Shanti Sumartojo and Emma Waterton, Geographies of Commemoration in a Digital World: Anzac @ 100, Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan, 2021, p 11.

61 Untitled (seven monuments), n.d., http://www.untitledsevenmonuments.com.au (accessed 10 March 2023).

62 Acca, Chimney in Store.

63 Robert Smithson, ‘The Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey’, Artforum, December 1967, pp 52–57.

64 Tello, ‘Counter-Memory’, p 391.

65 Tello, ‘Counter-Memory’, p 395.

66 Pinto, Places of Reconciliation, p 37.

67 Holsworth, ‘The John Batman Memorial’.

68 Eve Tuck and K Wayne Yang, ‘Decolonisation is not a Metaphor’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society, 1(1), 2021, pp 1–40, p 3.

69 Tuck and Yang, ‘Decolonisation’, p 4.

70 Tuck and Yang, ‘Decolonisation’, p 10.

71 Porter, Jackson and Johnson, ‘Remaking Imperial Power’.

72 Pinto, ‘Places of Reconciliation’.

73 Reuben Rose-Redwood, Ian Baird, Emilia Palonen and CindyAnn Rose-Redwood, ‘Monumentality, Memoryscapes, and the Politics of Place’, ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 21(5), 2022, pp 448–467, p 454.

74 Tuck and Yang, ‘Decolonisation’, p 28.