Abstract

Increasing recognition of the difficulties women and adolescent girls face during menstruation has the prompted rapid implementation of menstrual health programmes and policies. Yet, there remains limited understanding of the influence of these interventions on individuals’ menstrual experiences. We systematically reviewed and synthesised qualitative studies of participant experiences of menstrual health interventions. Included studies were undertaken in 6 countries (India, Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, South Africa) and involved over 900 participants. Interventions focused on menstrual product or education provision. Only 6 of the 12 included studies were rated as high or medium trustworthiness. Exposure to new menstrual products led to changes in women’s and girls’ expectations of what a menstrual material should offer, with recipients highly valuing reduced fears of leakage and improved freedom of movement. After learning how to use new products or receiving educational materials, women and girls reported feeling more empowered and aware of the physiological process of menstruation, and in some cases wanted to share this knowledge with others in their communities. For each intervention, the process of introduction, trial and error, and acceptance of the new technologies or information was influenced by the sociocultural environment including parents, peers and teachers.

Background

Growing recognition of the difficulties women and girls face during menstruation has prompted accelerated investment in policies and programmes to improve menstrual health (Sommer et al. Citation2015; Bobel Citation2018). Qualitative research and insights from practice have identified multiple levers for intervention including: access to preferred menstrual materials, improved menstrual knowledge, supportive infrastructure such as girl and woman friendly toilets and addressing broader sociocultural contributors such as menstrual stigma and social support (Schmitt et al. Citation2018; Caruso et al. Citation2013; UNICEF Citation2019; Hennegan et al. Citation2019). Despite the proliferation of menstrual health programmes and policies to address these needs, there remains limited research examining their effects.

Systematic reviews of trials have found inadequate evidence for the impact of menstrual health interventions (Hennegan and Montgomery Citation2016; Sumpter and Torondel Citation2013). Trial reviews are well-positioned to synthesise extant evidence for the effectiveness of tested programs. These reviews focus on ‘what works’, with primary outcomes for MH interventions often focused on education outcomes such as school attendance, health measured through reproductive tract infections, or improvements in menstrual knowledge (Hennegan and Montgomery Citation2016; Sumpter and Torondel Citation2013). Systematic reviews of trials have not offered a more holistic analysis of what happens in response to intervention implementation (Harris et al. Citation2018; Munn et al. Citation2018). As trials have focused on education and health impacts, there has been less attention to the intermediary influence MH programmes may have on menstrual experiences. Qualitative studies collected alongside programme implementation offer an opportunity to understand the lived experience of interventions. Findings can go beyond specified primary outcomes to unearth other influences of the intervention on individuals, highlight the pathways through which the intervention may have led to changes on quantitative outcomes, and identify barriers and facilitators to effectiveness (Harris et al. Citation2018). Systematic review and synthesis across these studies can generate new insights to inform the design of more effective interventions and trials (Booth et al. Citation2019).

The present review aims to synthesise, for the first time, the findings from qualitative studies of women and girls exposed to new menstrual health interventions or products. Rather than asking ‘what works’ or seeking to capture the effectiveness of interventions, we sought to understand how interventions influenced experiences of menstruation.

Methods

This review is reported in accordance with PRISMA guidance (see supplementary Appendix 1 online material). Systematic searches were conducted on 11 databases (Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts; Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature; ProQuest Dissertation and Theses; Embase; Global Health; Medline; Open Grey; Popline; PsycINFO; Sociological abstracts; WHO Global Health Library) using the search strategy reported in Appendix 2 of the online supplementary material. Grey literature was searched through databases and hand-searches of relevant websites. Reference lists of large menstrual health reports were searched, as were citations and reference lists of included studies (House et al. Citation2012; Geertz et al. Citation2016). Searches were conducted in January 2019 with no language or date restrictions. Two authors (AS, JH) independently screened titles and abstracts, followed by a full text screening (JH).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

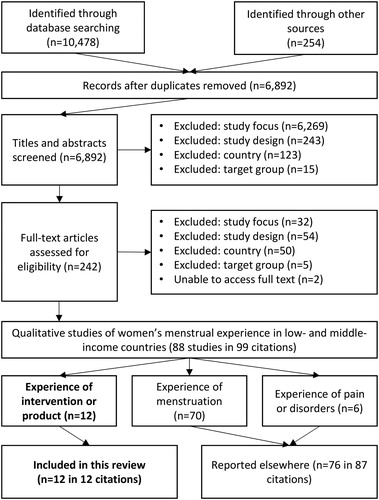

Searching, title and abstract screening were undertaken as part of a review of all qualitative studies of women and girls’ menstrual experiences in low- and middle-income countries, see (Hennegan et al. Citation2019). As part of an iterative screening process, studies were grouped according to their research questions. Studies of experiences of menstrual health interventions delivered by investigators were identified as a distinct sub-group for separate review, presented here.

Thus for this review we included studies which: (i) were qualitative or mixed methods studies of experiences of menstruation, (ii) included post-menarche girls and women as the population of interest, (iii) drew on populations from low- and middle-income countries as defined by the World Bank (Citation2017), and (iv) focused on girls’ and women’s experiences of interventions designed to improve menstrual experience or a provided menstrual product (material for absorbing or collecting menses, e.g. disposable or reusable pads or menstrual cups).

We excluded studies focused on the acceptability of menstrual suppression and those regarding puberty or sanitation infrastructure that did not report on participant menstrual experiences. We also excluded studies that did not report qualitative results (e.g. qualitative responses backcoded for quantitative description).

Study quality assessment

Included studies were appraised using the EPPI-Centre quality appraisal tool (Rees et al. Citation2009). Two reviewers (AS, JH) independently assessed each study and assigned ratings across the following criteria: rigour in sampling, data collection strategies, analysis and interpretation; qualitative depth and breadth; and privileging of the experiences of women and girls in the study design. Reviewers then assigned overall quality and relevance ratings of low, medium or high and discussed differences to reach consensus.

Data synthesis

Informed by thematic synthesis methods (line-by-line coding and extraction of study themes), salient themes within and across studies were identified. Thematic networks, in the form of visual representations of the links between themes were utilised to organise themes and develop a visual representation of findings (Melendez-Torres, Grant, and Bonell Citation2015; Attride-Stirling Citation2001). This approach was chosen to identify commonalities in the findings between studies, leading to the naming and description of a) third-order constructs that encompass and go beyond multiple studies’ locally specific findings and b) the links between these third-order constructs. This is also known as ‘reciprocal translation’ (Noblit and Hare Citation1988), or the process of understanding one study’s findings in terms of another. Synthesis was undertaken in four steps:

Two authors (AS, JH) independently reviewed each study of high and medium quality and identified salient themes across studies, collating representative quotations for cross-comparison.

Authors mapped the relationships between themes across and within studies.

Multiple consultations were held among the review team to identify final themes and the thematic structure with the greatest explanatory depth.

Studies of low quality were assessed for their fit and integrated by the first author.

Results

The review flowchart in presents the searching and screening results from the broad review and the studies included in this review.

Figure 1. Review flow diagram showing the number of titles, abstracts and full text citations assessed for eligibility and reasons for exclusion.

Characteristics of included studies

Study characteristics are presented in . Included studies captured experiences from 6 countries and over 900 participants. Four were undertaken in India, three in Uganda, two in Kenya, and one in Ethiopia, Zimbabwe and South Africa. Most studies focused on adolescent girls (n = 8), with fewer concerning adult women (n = 3), or a combination of women and girls (n = 1). Six of the included studies used a mixed-methods approach. Four studies drew exclusively from focus group discussions (FGDs), four from a mix of FGDs and individual interviews, and three from interviews alone. One study used anonymous written responses to open-ended questions (Blake et al. Citation2018).

Table 1. Included study and intervention characteristics and overall trustworthiness rating.

provides a summary of study characteristics and interventions. Seven studies included participants who were provided a menstrual product or asked to report on their perceptions of different products (reusable cloths and pads, disposable pads, and menstrual cups), two studies included participants exposed to education alone, and in five studies participants received both education and products together. One marketing study sought women’s perceptions of the different menstrual products they had experienced or used, as well as their awareness and perceived acceptability of tampons (Rane Citation2014).

Four qualitative studies were conducted alongside controlled trials (Hyttel et al. Citation2017; Mason et al. Citation2015; Hennegan et al. Citation2017; Blake et al. Citation2018). Trial outcomes varied across menstrual knowledge, school attendance, reproductive tract infections and acceptability of the intervention. Other studies were qualitative follow-ups of programmes implemented, or in one instance the acceptability of a potential product intervention (menstrual cup) (Averbach et al. Citation2009). Objectives of programmes were not always clearly described but included improving attitudes towards menstruation, and menstrual knowledge (Chikulo Citation2015), testing the acceptability and feasibility of interventions (Garikipati and Boudot Citation2017; WoMena Citation2017), and improving hygiene practices (Rajagopal and Mathur Citation2017; Shah et al. Citation2013)

Study quality

Only half of the included studies were rated as high or medium quality (n = 6) with overall trustworthiness reported in , and full appraisal in Appendix 3 of the online supplementary materials. Lower quality studies exhibited poor reporting of participant selection and analysis. Included studies of high and medium quality were conceptually developed and provided more rigorous sampling, data collection and analysis.

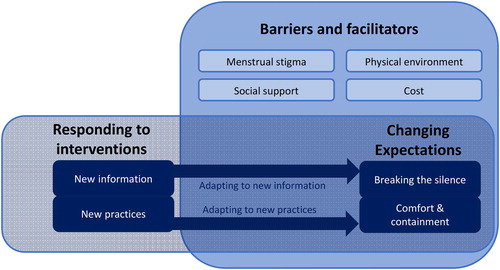

Emergent themes reflected participants’ experiences of exposure to the interventions or investigator-presented products, and the interaction between this experience and participants’ environments (identified as barriers and facilitators). Initial and final themes are reported in Appendix 4 of the online supplementary material.

We present findings according to the following thematic network () where top level themes are represented by bolded text, and sub-themes by un-bolded text.

Lower quality studies fit within the thematic network, although typically offered less depth. These studies often reinforced themes around barriers and facilitators but provided fewer insights on responses to interventions.

Responding to interventions

New information

In all studies, education or the presentation of menstrual product options exposed women and girls to new information. Participants reflected on this new knowledge, often contrasting it with deficits they had experienced before. In studies of education interventions, this ranged from improved understanding of reproductive biology; ‘It is important as it clearly shows that menstruation does not mean that the girl has started sexual intercourse with male’ (Blake et al. Citation2018, 13), to practical management; ‘[I] didn’t know how to put the pads in the knickers very well’. (Hennegan et al. Citation2017, 84).

Reproductive education and product information need to be integrated with individuals’ past experiences, misconceptions and advice from other sources. Hennegan et al. (Citation2017) reported that girls expressed confusion about which sources of information to believe. For example, they were told during the education intervention that they did not need to restrict physical activity during menstruation but received conflicting warnings from family members. This finding was not echoed in a study of book-based puberty information which was reportedly adopted at four-week follow-up, although participants stated that the information in the book should be shared with others in the community (Blake et al. Citation2018).

In Kenya, Mason et al (Citation2015) identified challenges of conflicting information where members of the community had warned girls of dire consequences of using the provided menstrual cup. Hyttel et al. (Citation2017) also described that girls sought support to help them assess which information to believe about the use of menstrual cups.

I also hear people saying that it enlarges the uterus, so I tried to leave using it, but then I thought that I should first ask the senior woman teacher… and then she gave me advice on that thing and up to today, I am not using people’s words (Hyttel et al. Citation2017, 119).

When introducing new products, the way the information was shared with recipients was important for their trust and acceptance of the technology. Technologies were often introduced in the format of FGDs where girls could digest new information together (Hyttel et al. Citation2017; Averbach et al. Citation2009), or with accompanying nurses who could answer questions (Mason et al. Citation2015).

Why I felt that that [cup] is good was because of how they explained; how to fold, insert all made me feel that using it is easy and I joined and received it (Hyttel et al. Citation2017, 117).

In contrast, women in slums exposed to a programme to support door-to-door sales of sanitary pads which was not paired with education reported more hesitance to adopt new technologies. Participants reported a preference for a more familiar reusable product than the disposable pads promoted, with one participant stating: ‘I don’t know how to use pads, once I tried and it leaked…’ (Garikipati and Boudot Citation2017, 44).

New practices

Adapting to the use of new products was a learning process. Authors described initial reactions, periods of experimentation, and mastery or comfort with new practices. At first, most women and girls expressed shock and surprise at the menstrual cup (Averbach et al. Citation2009; Mason et al. Citation2015; Hyttel et al. Citation2017). The inserted nature evoked fears of discomfort and consequences for health.

…but first days when we saw [the menstrual cup] we thought – it is too big! It cannot fit! (Mason et al. Citation2015, 18).

Similar thoughts about the inserted nature of tampons were voiced by women in a market study by Rane (Citation2014), where authors note usage by a small proportion of women in India, as in other low- and middle-income countries.

Adolescents reported experiences of physical pain during first insertions of the menstrual cup. Authors noted mastering the technique of inserting and removing the cup took time and practice (Hyttel et al. Citation2017; Mason et al. Citation2015). Willingness to keep trying, support from other women and girls, and training provided as part of the interventions were all important.

I felt pain, then I said to myself ‘this thing is difficult to insert’, then I said again ‘no, I heard people talking that it is good’ so I went to try again. So, from that day up to now I have been using it (Mason et al. Citation2015, 19).

This growing mastery and sense of trust in the technology was a salient narrative in studies of experiences with menstrual cups. Hyttel et al. (Citation2017) noted the adoption of new practices at a personal, but also social level, invoking the diffusions of innovations approach to cup uptake (Rogers Citation1995).

While the provision of more familiar technologies such as reusable pads required less practice than cups, properties of these material provoked changes in management and hygiene practices (Hennegan et al. Citation2017; WoMena Citation2017). Hennegan et al. (Citation2017) found that when using commercially produced AFRIpads some girls noted they could change their materials more quickly, and thus may be more willing to do so in existing school latrines, in contrast to those in control conditions (largely using cloth). It was not clear if students adapted to this change after a period of experimentation as described for the adoption of menstrual cups. In one study, the colour of the new product influenced changing menstrual practices as it could be more discreetly dried:

The new cloth is good because it is easy to dry, stains are not visible as it is red coloured and we could dry it easily in an open place in sunlight (Shah et al. Citation2013, 209).

Changing expectations

In response to both product and information-focused interventions, women and adolescents in high and medium trustworthiness studies consistently expressed a change in expectations for their menstruation (n = 6), and this theme was also evident in two low trustworthiness studies (WoMena Citation2017; Rane Citation2014). This included changed perceptions of the level of comfort a menstrual material should provide and what one should be able to do while wearing it. It also included new expectations about what menstrual information should be discussed with others.

Comfort and containment

In studies where products had been provided (n = 7), authors reported on participants’ appraisals of performance (or perceived performance), compared to their past practices. Most intervention products were viewed as better fit-for-purpose, causing less irritation and being more reliable than past practices (Hennegan et al. Citation2017; Mason et al. Citation2015; Hyttel et al. Citation2017). Some participants still reported discomfort when wearing pads (reusable or disposable) for too long, or feared that others might be able to see the pad when they were wearing it (Hennegan et al. Citation2017; Garikipati and Boudot Citation2017; Mason et al. Citation2015).

Where multiple options were provided, participants contrasted between these (Shah et al. Citation2013; Garikipati and Boudot Citation2017; Rajagopal and Mathur Citation2017; Mason et al. Citation2015). Shah et al. (Citation2013) found adolescents reported improved experiences of a reusable cloth pad due to the comfort and colour of the cloth and preferred this product to an alternative single-use pad which presented disposal challenges. Garikipati and Boudot (Citation2017) reported mixed findings with some women preferring disposable pads and other reusables.

The reliability of menstrual materials to prevent staining of under or outer garments was a salient narrative across all product studies (n = 12). Studies noted reduced concerns that menstrual materials would ‘fall out’ of place or produce detectable odour. In studies that included women and girls who had used the menstrual cup (Mason et al. Citation2015; Hyttel et al. Citation2017), women who had used commercial sanitary pads versus cloth pads (Shah et al. Citation2013) and women who had used tampons (Rane Citation2014), the freedom of movement afforded by inserted products was associated with positive appraisal. In one study, parents also reported observing girls’ demeanour as more ‘free’ and ‘confident’ during menstruation after using a menstrual cup (Mason et al. Citation2015). After experience with new products, girls noted that they and others could ‘contain’ their menstruation as needed and could engage in activities they had not previously considered doing during menstruation, such as playing sports.

I found using it was interesting and easy because once you have inserted it you can play so freely you will not feel that there is something in your body (Hyttel et al. Citation2017, 120).

Breaking the silence

Interventions or products presented to participants were often appraised by their ability to reduce anxiety around managing menstruation, or the ways in which they dispelled shame and taboos surrounding periods (Hennegan et al. Citation2017; Mason et al. Citation2015; Hyttel et al. Citation2017; Blake et al. Citation2018). Education interventions reframed menstruation as a natural process and prompted girls to raise menstruation as a topic with parents (Hennegan et al. Citation2017; Blake et al. Citation2018), possibly breaking existing communication barriers. These interventions resulted in new expectations around what girls felt was appropriate to share with others. For example, many quotations from Blake et al. (Citation2018) captured girls’ new perspectives that menstruation was normal and should not be kept secret.

It [the book] encourages us to tell our family when we see menstruation for the first time. Moreover, it also gives us confidence about our physical growth (Blake et al. Citation2018, 13).

When contrasting education conditions against control and product-only interventions, Hennegan et al. (Citation2017) noted that girls who had received education were freer discussing menstruation and using terms for female anatomy in interviews.

Barriers and facilitators

Menstrual stigma

Despite positive changes resulting from the interventions, all studies noted that women and girls continued to operate in a socio-cultural environment of menstrual stigma. Few studies directly addressed how this impacted participant experiences, but the influence of stigma was evidenced in participant’s continued concerns about washing, drying and disposing of used menstrual materials or responses to the idea of menstruation as a less secretive topic communicated in education interventions. As noted above, many girls expressed the new desire to openly share menstrual information and experiences, but it is unclear from included studies how this was received by community members not participating in the intervention. Hennegan et al (Citation2017) noted that girls’ seeking help for menstrual challenges, such as pain relief, met an unsupportive environment. Girls also stated that they would be too embarrassed to seek help if they experienced genital itching or discharge.

Social support

Social support sources included peers, parents and female teachers. Across studies, support sources either enhanced the impact of the interventions or presented a barrier to positive experiences (WoMena Citation2017; Mason et al. Citation2015; Hyttel et al. Citation2017; Hennegan et al. Citation2017; Stopford Citation2011; Rajagopal and Mathur Citation2017). For example, mothers’ reactions to the menstrual cup featured in their successful uptake:

[B]oiling nowadays is easy because my mother also now knows about the cup, so she is the one who gives me the opportunity to boil it … My mother said, if it is a good thing, you use it and make sure you follow the right teachings they gave you about using the cup, if you know that it will not bring any problem to you (Hyttel et al. Citation2017, 118).

At the same time, menstrual cup studies also described girls receiving negative comments from community members. It is unclear if this led to reduced uptake among some girls.

Female teachers were influential. In the case of menstrual cups, teachers helped to dispel misconceptions and encourage uptake, particularly in one study where teachers were also provided with cups (Hyttel et al. Citation2017). Hennegan et al. (Citation2017) noted that supportive behaviour among teachers was common and it was unclear if the education and other intervention components had prompted these behaviours, such as keeping extra school skirts for girls to change into.

A teacher might be teaching and then a friend stands up when she has soiled her clothes, you advise her to go out she leads the way and you follow to shadow her up. You get her other clothes to put on (Hennegan et al. Citation2017, 85).

In contrast, in a control school authors described an unsupportive response from teachers where girls were punished for missing class or arriving late due to menstruation. School-going girls in India reported that female teachers were unable to discuss menstruation or provide support as they themselves felt uncomfortable with the topic (Rajagopal and Mathur Citation2017).

Peers were an important source of support. Girls provided each other with spare clothes, cloths, and in some cases would help by holding latrine doors closed or by standing behind others who were menstruating (Hyttel et al. Citation2017; Hennegan et al. Citation2017). Early adopters of menstrual cups in two studies were influential in encouraging others and providing advice for girls to master the necessary techniques for their use (Hyttel et al. Citation2017; Mason et al. Citation2015).

Physical environment

The uptake of new menstrual products was supported or made more challenging by individuals’ physical environments, that is, the existing water and sanitation infrastructure, waste disposal mechanisms, housing structure, and environmental (climate) factors. Reusable sanitary pads needed to be washed and dried which presented ongoing challenges (Hennegan et al. Citation2017; Shah et al. Citation2013; Stopford Citation2011; WoMena Citation2017). Authors or participants across multiple studies highlighted that inadequate sanitation infrastructure, particularly at school, meant latrines were often avoided during menstruation (Rajagopal and Mathur Citation2017; WoMena Citation2017; Hyttel et al. Citation2017; Blake et al. Citation2018).

The toilets are not clean. In such a situation we try and avoid using the toilets. We also refrain from drinking too much water (Rajagopal and Mathur Citation2017, 311).

Restricted waste disposal options for single-use sanitary pads made this less attractive than the reusable cloths provided in two studies in India (Shah et al. Citation2013; Garikipati and Boudot Citation2017). Girls in rural Uganda and in Ugandan refugee camps reported challenges in sourcing containers for boiling menstrual cups, finding time and space to boil the cup, the need to transport water to latrines to clean the cup between uses, as well as fears around keeping the cup safe or hidden from others (WoMena Citation2017; Hyttel et al. Citation2017).

There was a problem of getting a tin [container] for boiling [the cup] … as the container has to be ‘something [we] no longer use’ (Hyttel et al. Citation2017, 116).

The seasonal availability of water also emerged as a barrier to cleaning and reusing pads in the dry season. Participants used products interchangeably to accommodate water availability in different seasons.

In the dry season you can use the cup because the cup does not need a lot of water. Like the AFRIpad, people will be using it when there is enough water and they can wash it, then that is why we are saying if the idea of giving two AFRIpads and a menstrual cup is there, it can work … (WoMena Citation2017, 36).

Costs

The cost of menstrual products was a key consideration for participants continued use of intervention menstrual products (n = 7 studies), with implications for the sustainability of these interventions. Funds for the material itself, as well as soap to wash reusable cloths, pads or the menstrual cup were deciding factors. The lower cost of reusable products over time was an attractive feature for reusable cloths in India (Shah et al. Citation2013), menstrual cups in Kenya and Uganda (Mason et al. Citation2015; Hyttel et al. Citation2017), and the Duet cup in Zimbabwe (Averbach et al. Citation2009).

We will use them [pads] if available from government at low cost (Shah et al. Citation2013, 209).

The longevity of the menstrual cup was particularly attractive, not only because it reduced quantity of soap needed for cleaning, but also because it could be dried quickly and reinserted with less hygiene concerns.

It will help you from wasting money monthly on buying pads … you can just only buy soap and if you use that soap specifically for the cup and your periods, one bar of soap you can use for 4 or 5 months (Hyttel et al. Citation2017, 119).

However, the high cost of the cup raised concerns that it could be lost or stolen, as well as other risks such as dropping the cup into the latrine or reports that one girl accidentally melted her cup in the fire while boiling it (Hyttel et al. Citation2017).

Across studies, the lower prioritisation of menstrual products in contrast to other urgent needs was apparent. In some cases, menstrual needs were contrasted with the money needed to buy food or other essential household items. Multiple comments from girls in the study by Hyttel et al (Citation2017) and in the 2017 WoMena study characterised repeated spending on pads as ‘wasteful’.

That cup I liked because they said it will last for 10 years, so I felt that for the 10 years, it will help us not to waste money (Hyttel et al. Citation2017, 119). [emphasis added]

Discussion

Women and girls reported positive experiences of interventions, expressing that the products or information were welcomed and helpful. This supports the continued potential for menstrual health interventions to address unmet menstrual needs and improve menstrual experiences.

Responding to interventions

Included studies described the way women and adolescents responded to interventions and integrated new knowledge or practices into their lives. Initial responses to new information or products were shaped by participants’ existing expectations and knowledge. This manifested in surprise or concern at the menstrual cup which varied substantially from past menstrual practices, or the need to digest new education considering conflicting information from other sources. These findings indicate that a population’s current menstrual expectations may influence the acceptability and effects of interventions. Programme results or trial effect estimates may not generalise to other settings, and implementors should be mindful of contextual needs when adapting interventions tested in other settings.

With the exception of one study which reported on a follow up four-weeks after receiving a puberty education book (Blake et al. Citation2018), participants’ narratives revealed changes to menstrual experience that evolved over the months following the intervention. This was particularly notable in studies of menstrual cups where participants described periods of learning and mastering use of the product. In multiple studies it was unclear how long was required for participants to feel confident using new knowledge or practices. In future research, follow-ups at multiple time points may be useful to understand how experiences change and provide more insights into the differences between initial response to interventions, as well as how these evolve and are maintained over time.

Changing expectations

Equipped with new information or practice using new products, women and girls across studies compared their menstrual experiences at the time of data collection with what they knew or felt before the intervention. Women and girls described new expectations of what their menstrual materials should provide them in containing menstruation and supporting free movement, as well as preferences for more open discussions around menstrual topics. Changing expectations of the comfort, containment, freedom of movement and secrecy of menstruation were positive outcomes of interventions. However, this change also presents a risk of harms where interventions are poorly sustained. Most study follow-up periods were short and there was no exploration of experience after interventions concluded, which may have the potential to increase negative self-concept and shame if women and girls are unable to continue using the products provided. Future research should investigate participant experiences at longer-term follow-up and implementers should attend to the potential harms of discontinuing menstrual health programmes.

Barriers and facilitators

Participants’ narratives revealed barriers and facilitators to intervention effectiveness in improving menstrual experiences. These included menstrual stigma, social support, the physical environment, and costs. The latter was a salient barrier to sustainability of the changes introduced by interventions; however, all identified barriers are likely to inhibit or enhance intervention impacts over the long-term. While barriers clearly emerged from higher quality included studies, few explicitly focused on these topics. Future research is needed to explore the performance and experience of interventions with greater attention to the physical and socio-cultural context. Emergent barriers and facilitators provoke questions and considerations for future menstrual health research and practice.

First, how do communities respond to new attitudes of openness discussing menstruation? In two studies of education interventions, schoolgirls exhibited more openness and desire to discuss menstruation with others. It was unclear how others in the community responded to these attitudes, and if positive attitudes to menstruation would be sustained if girls were chastised or shamed for sharing menstrual information with community members who were not exposed to the intervention.

Social support either provided avenues for recipients to maximise the benefits of the intervention or discouraged change. Future interventions should consider how parent or teacher engagement may enhance or inhibit the effects of their programmes. Included studies of menstrual cup interventions described effective strategies of providing cups to teachers or having nurses on hand to answer questions and support use (Hyttel et al. Citation2017; Mason et al. Citation2015). It is unclear how such interventions could be brought to scale and the implications for the acceptability of menstrual cups if delivered through other modalities. Averbach et al. (Citation2009) suggested that women without this introduction process may still be interested in use of cups, but it was unclear if this extended to girls or if this would manifest in uptake if women initially struggled to afford or use a cup.

Physical infrastructure such as water, sanitation and hygiene facilities and other structures for changing or managing menstruation, together with climate, should be considered when planning and implementing interventions. Participants’ ability to implement behavioural changes was contingent on the available facilities, consistent with findings from qualitative studies of menstrual experiences in absence of intervention which have repeatedly highlighted the critical role of water, sanitation and hygiene in menstrual health (Girod et al. Citation2017; Sommer Citation2013; Hennegan et al. Citation2019). It was unclear from included studies the extent to which infrastructure deficits may have impeded desired impacts. More attention is needed, as is the consideration of more holistic interventions that address infrastructure.

Strengths and limitations

The findings of this synthesis are, like all systematic reviews, dependent on the quality of the included studies. There was a small number of included studies, only half of which were of high or medium trustworthiness. Most studies, particularly higher quality studies of intervention experiences, were undertaken with schoolgirls. Our emergent themes and thematic network are likely to be most representative of this population. Adult women and adolescent girls may have different experiences and responses to interventions. More research capturing the needs of adult women is needed (Hennegan et al. Citation2019). In the context of the thematic network from this study, older women will have a longer history of menstrual experience and may have more ingrained preferences or beliefs about the physical or social role of menstruation. They may be more hesitant to change behaviour, with one included study noting that many adult women in India expressed preferences for reusable pads rather than disposables as they were more familiar with them (Garikipati and Boudot Citation2017). Reflecting the quantitative evidence (Hennegan and Montgomery Citation2016), no studies included interventions to improve sanitation infrastructure, to which participants may respond differently.

Conclusions

As the scale of menstrual health intervention implementation increases, more research is needed to understand the experiences of women and girls participating in such programmes. High quality research is needed to understand responses to interventions, and the process through which they are integrated into recipients’ lives. Findings suggest that in future qualitative studies undertaken alongside interventions, researchers should attend to the ways in which the physical and sociocultural environment interacts with interventions. This synthesis found MH interventions provoked changes to women’s and girls’ expectations of their menstrual experience. These changes may mediate desired impacts on outcomes such as attendance at school. Implementers should be mindful of the sustainability of interventions where women and girls may struggle to maintain access to new levels of open communication or menstrual materials after programmes conclude.

Acknowledgement

The protocol for this review was pre-registered on the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews: PROSPERO CRD42018089581.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Attride-Stirling, J. 2001. “Thematic Networks: An Analytic Tool for Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research 1 (3): 385–405. doi:10.1177/146879410100100307

- Averbach, S., N. Sahin-Hodoglugil, P. Musara, T. Chipato, and A. van der Straten. 2009. “Duet for Menstrual Protection: A Feasibility Study in Zimbabwe.” Contraception 79 (6): 463–468. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.12.002

- Blake, S., M. Boone, A. Yenew Kassa, and M. Sommer. 2018. “Teaching Girls about Puberty and Menstrual Hygiene Management in Rural Ethiopia.” Journal of Adolescent Research 33 (5): 623–646. doi:10.1177/0743558417701246

- Bobel, C. 2018. The Managed Body: Developing Girls and Menstrual Health in the Global South. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Booth, A., J. Noyes, K. Flemming, G. Moore, Ö. Tunçalp, and E. Shakibazadeh. 2019. “Formulating Questions to Explore Complex Interventions within Qualitative Evidence Synthesis.” BMJ Global Health 4 (Suppl 1): e001107. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001107

- Caruso, B. A., A. Fehr, K. Inden, M. Sahin, A. Ellis, K. L. Andes, and M. C. Freeman. 2013. WASH in Schools Empowers Girls’ Education in Freetown, Sierra Leone: An Assessment of Menstrual Hygiene Management in Schools. New York: UNICEF.

- Chikulo, B. C. 2015. “An Exploratory Study into Menstrual Hygiene Management Amongst Rural High School for Girls in the North West Province, South Africa. (Special Issue: Sexual and Reproductive Health Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa.).” African Population Studies 29 (2): 1971–1987. doi:10.11564/29-2-777

- Garikipati, S., and C. Boudot. 2017. “To Pad or Not to Pad: Towards Better Sanitary Care for Women in Indian Slums.” Journal of International Development 29 (1): 32–51. doi:10.1002/jid.3266

- Geertz, A., L. Iyer, P. Kasen, F. Mazzola, and K. Peterson. 2016. “An Opportunity to Address Menstrual Health and Gender Equity.” FSG. https://www.fsg.org/publications/opportunity-address-menstrual-health-and-gender-equity#download-area

- Girod, C., A. Ellis, K. L. Andes, M. C. Freeman, and B. A. Caruso. 2017. “Physical, Social, and Political Inequities Constraining Girls’ Menstrual Management at Schools in Informal Settlements of Nairobi, Kenya.” Journal of Urban Health 94 (6): 835–846. doi:10.1007/s11524-017-0189-3

- Harris, J. L., A. Booth, M. Cargo, K. Hannes, A. Harden, K. Flemming, R. Garside, T. Pantoja, J. Thomas, and J. Noyes. 2018. “Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group Guidance Series-Paper 2: Methods for Question Formulation, Searching, and Protocol Development for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 97: 39–48. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.023

- Hennegan, J., C. Dolan, L. Steinfield, and P. Montgomery. 2017. “A Qualitative Understanding of the Effects of Reusable Sanitary Pads and Puberty Education: Implications for Future Research and Practice.” Reproductive Health 14 (1): 78. doi:10.1186/s12978-017-0339-9

- Hennegan, J., and P. Montgomery. 2016. “Do Menstrual Hygiene Management Interventions Improve Education and Psychosocial Outcomes for Women and Girls in Low and Middle Income Countries? a Systematic Review.” PLoS One 11 (2): e0146985. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146985

- Hennegan, J., A. K. Shannon, J. Rubli, K. J. Schwab, and G. J. Melendez-Torres. 2019. “Women’s and Girls’ Experiences of Menstruation in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Metasynthesis.” PLoS Medicine 16 (5): e1002803. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002803

- House, S., S. Cavill, T. Mahon, and A. Against Hunger. UNICEF, and WASH Advocates. 2012. Menstrual Hygiene Matters: A Resource for Improving Menstrual Hygiene Around the World. WaterAid. https://www.wsscc.org/resources-feed/menstrual-hygiene-matters-resource-improving-menstrual-hygiene-around-world/

- Hyttel, M., C. F. Thomsen, B. Luff, H. Storrusten, V. N. Nyakato, and M. Tellier. 2017. “Drivers and Challenges to Use of Menstrual Cups among Schoolgirls in Rural Uganda: A Qualitative Study.” Waterlines 36 (2): 109–124. doi:10.3362/1756-3488.16-00013

- Mason, L., K. Laserson, K. Oruko, E. Nyothach, K. Alexander, F. Odhiambo, A. Eleveld, et al. 2015. “Adolescent Schoolgirls’ Experiences of Menstrual Cups and Pads in Rural Western Kenya: A Qualitative Study.” Waterlines 34 (1): 15–30. doi:10.3362/1756-3488.2015.003

- Melendez-Torres, G. J., S. Grant, and C. Bonell. 2015. “A Systematic Review and Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Metasynthetic Practice in Public Health to Develop a Taxonomy of Operations of Reciprocal Rranslation.” Research Synthesis Methods 6 (4): 357–371. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1161

- Munn, Z., C. Stern, E. Aromataris, C. Lockwood, and Z. Jordan. 2018. “What Kind of Systematic Review Should I Conduct? a Proposed Typology and Guidance for Systematic Reviewers in the Medical and Health Sciences.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4

- Noblit, G., and R. Hare. 1988. Meta-Ethnography. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Rajagopal, S., and K. Mathur. 2017. “Breaking the Silence around Menstruation’: Experiences of Adolescent Girls in an Urban Setting in India.” Gender & Development 25 (2): 303–317. doi:10.1080/13552074.2017.1335451

- Rane, R. 2014. “Marketing Tampons in Urban India: A Study of Barriers and Triggers to Purchase.” Degree of PGDM, Mudra Institute of Communications, Ahmedabad. Ann Arbor: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Rees, R.,. K. Oliver, J. Woodman, and J. Thomas. 2009. Children’s Views about Obesity, Body Size, Shape and Weight: A Systematic Review. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

- Rogers, E.M. 1995. Diffusion of Innovation Theory. New York: The Free Press.

- Schmitt, M., D. Clatworthy, T. Ogello, and M. Sommer. 2018. “Making the Case for a Female-Friendly Toilet.” Water 10 (9): 1193–1202. doi:10.3390/w10091193

- Shah, S. P., R. Nair, P. P. Shah, D. K. Modi, S. A. Desai, and L. Desai. 2013. “Improving Quality of Life with New Menstrual Hygiene Practices among Adolescent Tribal Girls in Rural Gujarat, India.” Reproductive Health Matters 21 (41): 205–213. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41691-9

- Sommer, M. 2013. “Structural Factors Influencing Menstruating School Girls’ Health and Well-Being in Tanzania.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 43 (3): 323–345. doi:10.1080/03057925.2012.693280

- Sommer, M., J. S. Hirsch, C. Nathanson, and R. G. Parker. 2015. “Comfortably, Safely, and without Shame: Defining Menstrual Hygiene Management as a Public Health Issue.” American Journal of Public Health 105 (7): 1302–1311. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302525

- Stopford, A. L. 2011. “The Effect of Commercial Sanitary Pad Use on School Attendance and Health of Adolescents in Western Kenya.” Master’s Thesis, Duke University. https://hdl.handle.net/10161/5062

- Sumpter, C., and B. Torondel. 2013. “A Systematic Review of the Health and Social Effects of Menstrual Hygiene Management.” PLoS One 8 (4): e62004. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062004

- UNICEF. 2019. Guidance on Menstrual Health and Hygiene. New York: UNICEF.

- WoMena. 2017. “Pilot Intervention Report: Menstrual Health in Rhino Camp Refugee Settlement West Nile, Uganda.” Uganda: WoMena. http://womena.dk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/WoMena-ZOA-Rhino-Camp-Refugee-Settlement-MHM-Pilot-Intervention-Report.pdf

- World Bank. 2017. “World Bank Country and Lending Groups.” World Bank. Accessed December, 20.