Abstract

Young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds experience barriers accessing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) information and care. This systematic review, utilising a pre-determined protocol, performed according to PRISMA guidelines, explored SRH knowledge, attitudes and information sources for young (16–24 years) culturally and linguistically diverse background people living in Australia, to gain understanding of their sexual health literacy. CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed and Scopus were systematically searched with inclusion criteria applied to 216 articles. After title and abstract screening, backward/forward searching, and full-text review of 58 articles, 13 articles from eight studies were identified. Thematic analysis, guided by core constructs from cultural care theory, identified three themes: (1) SRH knowledge varied by topic but was generally low; (2) young people’s attitudes and beliefs were influenced by family and culture; however, ‘silence’ was the main barrier to sexual health literacy; and (3) Access to SRH information was limited. To attain sexual health literacy and equitable access to culturally-congruent and responsive SRH information and care, there is a need for theory-informed strategies and policies that address the diverse social, cultural and structural factors affecting young culturally and linguistically diverse background people, especially the ‘silence’ or lack of open SRH communication they experience.

Introduction

Young people aged 16–24 years in Australia experience a disproportionate burden of sexually transmissible infections (STI) (Australian Government Citation2018a), and other adverse sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes (e.g. unintended pregnancies, unwanted sexual activity) (Fisher et al. Citation2019; Marino et al. Citation2016). Australia is a diverse multicultural nation in which over 28% of people are born overseas (Australian Government Citation2018b). While not universal, young people born overseas living in Australia and those who have one or more overseas-born parent face additional and unique barriers to accessing quality SRH care and information, especially young people who come from minority ethnic and/or migrant and refugee backgrounds (Alarcão et al. Citation2021). These barriers plus the impact of SRH-related taboos, conservative cultural constructs and intergenerational discord (Dean et al. Citation2017a); pre-arrival experiences of mobility/displacement (Napier-Raman et al. Citation2023); and post-arrival discrimination (Alarcão et al. Citation2021; Vujcich et al. Citation2022) suggest why young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds should be recognised as a priority community. COVID-19 has exacerbated SRH barriers and inequities in part due to competing health priorities and healthcare demands (Alarcão et al. Citation2021; Vujcich et al. Citation2022), magnifying the need to better understand and respond to the nuanced SRH needs and barriers faced by young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. To achieve this, it is critical to improve understanding of how broader social contexts influence access to SRH information and care

Understanding the ways culture, social context and migration background influence SRH and access to care is important (Alarcão et al. Citation2021). Culture Care Diversity and Universality theory (CCT) highlights the need to understand how cultural values, beliefs and practices, and social and structural factors such as religion/spirituality, kinship, politics, economics, education and technology impact on the knowledge, attitudes, actions and practices/skills of individuals (McFarland and Wehbe-Alamah Citation2019). Such understandings encourage the development and provision of culturally congruent forms of care, and inform constructs that influence how people seek health information, communicate, and develop a level of health literacy that enables them to seek/access care in a safe and responsive way. A systematic review of health literacy models by Sørensen et al. (Citation2012) found health literacy frameworks grounded in theory enhance understanding of the factors which impact individual health literacy. However, health literacy models do not always recognise the impact that cultural variation has on the knowledge, attitudes and skills necessary to access information/care (Nutbeam Citation2000).

Understanding where young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds seek SRH information and apply this in the form of health-seeking/protective behaviours – i.e. sexual health literacy - is associated with improved SRH outcomes (Vongxay et al. Citation2019). While health literacy has been defined in various ways (Nutbeam Citation2000; Sørensen et al. Citation2012; Vongxay et al. Citation2019), knowledge, attitudes and access to appropriate information are key components across definitions, in alignment with CCT core constructs (McFarland and Wehbe-Alamah Citation2019). In this review, sexual health literacy is identified as the means to incorporate these key components to inform SRH decision making, thus providing a platform to better understand the intersections between culture and sexual health literacy.

The United Nations recognises SRH as a fundamental human right (United Nations Citation2014). SRH information/services should be accessible to all people in a culturally-safe and responsive way (Maheen et al. Citation2021). To achieve this, service providers and policy makers need to understand what young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds living in Australia know and feel about SRH, and where they access information. A 2016 scoping review by Botfield, Newman, and Zwi (Citation2016) called for greater awareness of this gap in understanding. The present study systematically searched and critically appraised the literature to address the following research questions:

What are the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds in Australia regarding SRH?

Where do young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds in Australia seek and receive SRH information?

Materials and methods

Search strategy

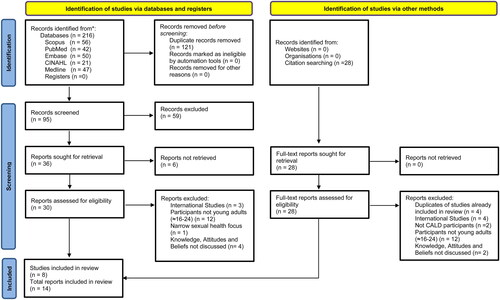

This systematic review, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al. Citation2021) used a systematic approach to search five databases: CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed and Scopus. Conducted by one reviewer (AL) in July 2021, the search used a combination of search terms developed following the PICO framework (see ) relating to young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, SRH, sexual health literacy, health literacy and Australia and a variety of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms collated from previous literature by the authors in collaboration with a university librarian.

Table 1. Complete list of search terms stratified by PICO.

Inclusion criteria included primary research of all designs that explored SRH knowledge, attitudes and/or beliefs, sexual health literacy and/or access to SRH information by young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (16–24 years) in Australia (see ). Only full-text English language papers were included. There was no restriction on publication date. Reviews, grey literature and other secondary sources were excluded along with non-English language papers, research conducted outside Australia and studies where the focus was on adults or children under 16-years, or where age range was unlimited and with no specific focus on young people.

Study selection and quality assessment

Initial database searches identified 216 articles. These were uploaded into Endnote X9. Following the removal of 121 duplicates, one author (AL) conducted a title/abstract screen against inclusion criteria, excluding 59 articles. Of the remaining 36 articles, 30 full-text articles were retrieved. Backward/forward citation searching of these identified 28 missed studies (Briscoe, Bethel and Rogers Citation2020). Two authors (AL, JD) then independently conducted a full-text review of these 58 papers with disagreements/differences resolved by discussion (see ). These two authors independently applied the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) to critically appraise the quality of selected studies with an asterisk (*) allocated for each listed methodological quality criterion met (see ). Studies were not excluded based on quality assessment outcomes.

Table 2. Descriptive details and MMAT quality assessment scores of papers included in the review.

Data extraction, presentation and synthesis of Results

Descriptive details of included studies (research questions, study design, target population, country of origin, key findings) were extracted into a table and cross-referenced by two authors (AL, JD) to enhance accuracy, consistency and reliability—with disparities resolved by discussion. The results and discussion sections of each paper were read to identify key concepts and themes. Qualitative data were first collated and coded into descriptive themes using broad constructs related to the research questions. Quantitative results were then considered for concepts and patterns, and these were interpreted and coded to align with the descriptive themes identified in the qualitative data (Harden and Thomas Citation2005). Thematic synthesis, adapted from Braun and Clarke (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), was then conducted with identified themes compared across studies and grouped under CCT constructs knowledge, attitudes, actions and practices/skills (McFarland and Wehbe-Alamah Citation2019). This allowed the authors to interpret/explain correlations between constructs, while acknowledging diversity between/within cultures (McFarland and Wehbe-Alamah Citation2019). CCT constructs also guided the outline of the findings and formed the basis for analysing diversity and understand care implications (McFarland and Wehbe-Alamah Citation2019). Quotes extracted from the included papers have been included to support the themes identified in the review. Pseudonyms and variables used to stage the quote in the original study have been used alongside the included quotes to provide context. Included studies were also assessed to determine whether their designs were underpinned by a theoretical framework.

Results

Summary of study characteristics

Of the 58 full-text articles assessed, 13 articles (published 2009–2018) arising from eight studies were included in the review. summarises the characteristics and main findings from the included articles along with outcomes of the MMAT quality assessment. Evidence suggests the majority of the studies met all listed methodological quality criteria (with the exception of Dune et al. Citation2017). Participants were either within or their mean age was within the 16–24 years target age range. One study focused on a single country of origin (Dean et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b) while the other seven included young people from a number of countries. Four studies specifically focused on young women (Ngum Chi Watts, Liamputtong and Carolan Citation2014; Ngum Chi Watts, McMichael and Liamputtong Citation2015; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2009, Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014, Citation2015; Wray, Ussher and Perz Citation2014), while the remaining four studies reported that they recruited both young women and men, (Botfield et al. Citation2018; Dean et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Dune et al. Citation2017; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009, Citation2010). Two studies utilised quantitative methods in the form of a cross-sectional survey (Dean et al. Citation2017b) and Q methodology (Dune et al. Citation2017); while the others were qualitative investigations (mostly using semi-structured interviews/focus groups and thematic analysis).

Study locations

The studies were conducted in Queensland (Dean et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014, Citation2015), New South Wales (Botfield et al. Citation2018; Dune et al. Citation2017; Wray, Ussher and Perz Citation2014) and Victoria (McMichael and Gifford Citation2009, Citation2010; Ngum Chi Watts, Liamputtong and Carolan Citation2014; Ngum Chi Watts, McMichael and Liamputtong Citation2015; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2009, Citation2010).

Key themes

Analysis and synthesis of the findings enabled the development of three themes aligned with CCT constructs which were used to guide analysis: 1) sexual and reproductive health knowledge varied by topic but was generally low; 2) attitudes and beliefs were influenced by family and culture, however ‘silence’ was the main barrier to sexual health literacy; and 3) access to SRH information was limited and influenced by family and other social and cultural factors.

SRH knowledge varied by topic but was generally low

All eight studies explored SRH knowledge: either directly through young people’s perceptions of their knowledge levels, or indirectly through questions about information sources, interpretation and implementation. Of the 13 included papers from these eight studies, 12 of them, published over a 10-year period, reported knowledge of SRH-related topics among young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds was generally low, especially concerning contraception and STIs (Botfield et al. Citation2018; Dean et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Dune et al. Citation2017; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009, Citation2010; Ngum Chi Watts, Liamputtong and Carolan Citation2014; Ngum Chi Watts, McMichael and Liamputtong Citation2015; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014; Wray, Ussher and Perz Citation2014). For example, a mixed-methods study involving young people of Sudanese refugee background found generally low knowledge, with a mean HIV knowledge score of 6.8 out of 12 (57%) and 3.6 out of 11 (33%) for STIs (Dean et al. Citation2017b). Knowledge levels about STIs and HIV were significantly higher among young women than among young men, however qualitative data suggest knowledge deficits among both were contributing to unplanned pregnancies and STIs (Dean et al. Citation2017a):

… they start having sex… and they don’t use protection. They don’t have knowledge about the sexual diseases… – 21-year-old young woman

Two studies involving young people from a range of ethnic backgrounds related low SRH knowledge levels to a lack of access to SRH education before coming to Australia (McMichael and Gifford Citation2009; Ngum Chi Watts, Liamputtong and Carolan Citation2014; Ngum Chi Watts, McMichael and Liamputtong Citation2015). McMichael and Gifford identified interruptions to education, prolonged time spent in refugee camps, minimal access to healthcare, the experience of sexual violence, and disruption to family as barriers to access to information prior to arrival whose effects may continue to exert an influence post-arrival (McMichael and Gifford Citation2009). Watts, Liamputtong and Carolan (2014) found in their study of young African Australian mothers, that some women had no knowledge of contraception prior to living in Australia:

I did not have an idea, that’s why [she became pregnant]. If I had idea then we just use something. – Veronica, aged 17

Attitudes and beliefs were influenced by family and culture, but ‘silence’ was the main barrier to sexual health literacy

This theme highlighted the extent that attitudes and beliefs were influenced by family and culture. Despite over a decade of time passing between publication, all 13 included papers reported on the influence of ‘silence’ – in the form of the lack of communication about SRH between young people, parents and the wider ethnic community—as a barrier to accessing culturally-congruent information and developing sexual health literacy. Six papers explicitly discussed this silence within families (Botfield et al. Citation2018; Dean et al. Citation2017a; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014, Citation2015), attributing it to the influence of cultural/religious beliefs preventing open communication and information exchange. Parental silence could also be an attempt to protect family social status and traditional values. However, discomfort discussing SRH within the home resulted in young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds experiencing limited family/community support. In Rawson and Liamputtong’s (Citation2009) study, young Vietnamese Australian women described how parental expectation to access medical care from a physician from within the same cultural/social community prevented them from accessing care due to fears about lack of confidentiality/anonymity.

I’d be really concerned if I went to my [physician] now about something sexual, that he’d contact my parents … It could be he thinks they’re from the same culture and they were looking after each other. That’s what would really concern me. – Mai, young Vietnamese woman.

Seven of the eight studies highlighted the influence of culture on the SRH of young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. All seven discussed the influence of gender roles/attitudes, especially among young women (Dune et al. Citation2017; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009, Citation2010; Ngum Chi Watts, McMichael and Liamputtong Citation2015; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014, Citation2015; Wray, Ussher, and Perz Citation2014). Traditional cultures worked to ensure that women remained ‘innocent’ and even ‘ignorant’ about SRH topics, with the belief that if knowledge was obtained there was a risk of this causing ‘shame’ or ‘stigma’ to the family (McMichael and Gifford Citation2009, Citation2010; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014; Wray, Ussher, and Perz Citation2014). The same factors surrounded attitudes towards young women’s engagement in pre-marital sexual activities (McMichael and Gifford Citation2009, Citation2010; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014; Wray, Ussher, and Perz Citation2014).

If my brother found out, I’d literally be dead. … The rest of my family would disown me as well… (Faaria, 18-year-old Muslim female)

Access to SRH information was limited and influenced by family and other social and cultural factors

Six articles explicitly discussed limited access to sources of information (Botfield et al. Citation2018; Dean et al. Citation2017b; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2009, Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2015). Reluctance to discuss SRH with family/trusted adults influenced information-seeking (Botfield et al. Citation2018; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014, Citation2015). Dean et al. (Citation2017b) found only 21.4% of 229 survey participants reported accessing mothers and 16.6% fathers as sources for SRH information. Peers were identified as a frequent source of SRH information in multiple studies, although they were often perceived as less trustworthy compared to others (Botfield et al. Citation2018; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010).

Health services as trusted information sources was a common theme across the studies. Dean et al. (Citation2017b) reported that 72% of participants greatly trusted doctors/physicians. However, similar to three other studies, they reported low access to medical staff due to lack of awareness, shame, stigma, language barriers and fears about confidentiality (Botfield et al. Citation2018; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2009, Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2015).

Schools were also identified as a common potential source of knowledge; however, one study reported traditional cultural beliefs/norms resulted in young people being prohibited from participating in school-based SRH education. As the authors, Rogers and Earnest (Citation2015) explain,

A lot of refugee and migrant parents will choose not to let their children participate in school [sexual and reproductive education] so these children are excluded from learning with their peers. This sets some of the children … back… when it comes to … knowing how to access contraception and services…

Lack of culturally safe content was identified as a further barrier to accessing information in three studies (Botfield et al. Citation2018; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010). Rawson and Liamputtong (Citation2010) reported young people found the SRH education lacked consideration of the social and cultural factors most relevant to young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. As described by Lan,

At school they focused on the biology stuff… Now, I really think young people need to know all the social things as well … The pressures, being careful and things like that, and for Vietnamese young people and really anyone from another culture, there’s all the cultural issues as well. These things are important, and I don’t think the schools are getting that. – Lan, 24-year-old Vietnamese woman

Discussion

Findings from this literature review reveal young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds from a wide range of ethnic backgrounds and arrival pathways have low SRH knowledge and limited access to appropriate and needed SRH information. Evidence suggests that their knowledge does increase with time spent in Australia (Dean et al. Citation2017a), however their family and broader traditional cultural beliefs and social context continue to influence their SRH-related attitudes and beliefs and create barriers to accessing information and care.

Traditional cultural beliefs/attitudes shaping views on gender and sexuality is not a new nor unexpected finding. However, the generally low levels of SRH knowledge found over the time period included in this review (2009–2018) suggests young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds continue to find it hard to access good quality, culturally-congruent information and opportunities to develop the knowledge, attitudes and skills necessary to access information and care—i.e. to achieving sexual health literacy (Nutbeam Citation2000).

Consistent with other literature (Mullens et al. Citation2018), findings from this review support the need for SRH information and service to be tailored to the gender, backgrounds and needs of a heterogeneous group of young people in Australia. Men’s control over women is a recurrent theme in SRH literature (Hussein and Ferguson Citation2019) and our findings reinforce the idea that young culturally and linguistically diverse background women are a key group to work with given the potential negative impacts of traditional cultural attitudes/gender role norms on autonomy regarding SRH decision making (McMichael and Gifford Citation2009, Citation2010; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014; Wray, Ussher and Perz Citation2014).

According to CCT, thought processes and choices are influenced by cultural values, ideals, norms and traditions, as well as by social structures (McFarland and Wehbe-Alamah Citation2019). Our review highlights that this influence occurs at individual and intergenerational levels and that intergenerational disparities in normative beliefs create barriers to accessing information including struggles to communicate with parents, families and the broader community (Botfield et al. Citation2018; Dean et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Dune et al. Citation2017; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009, Citation2010; Ngum Chi Watts, Liamputtong and Carolan Citation2014; Ngum Chi Watts, McMichael, and Liamputtong Citation2015; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014; Wray, Ussher and Perz Citation2014). These communication barriers, when combined with individual perceived and actual normative attitudes/beliefs toward SRH, can prevent young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds accessing social support (Viner et al. Citation2012). Research has shown how parental involvement in young people’s lives increased condom use and reduced the likelihood of negative sexual health outcomes (Majumdar Citation2006; Wang et al. Citation2014). Strategies for improving intergenerational communication ‘addressing the silence’ and promoting social support should be a focus for future research and sexual health literacy programmes (Dean et al. Citation2017a).

Understanding and addressing negative social norms can increase cultural safety/responsiveness of SRH information and care (McFarland and Wehbe-Alamah Citation2019). To improve sexual health literacy for young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds we need to develop information and services using evidence-informed culturally relevant theory, a gap identified in the studies included in this review. Such approaches may include adopting a human rights-based approach to mediate the effects of traditional culture or religious values and increase agency, and providing interventions in a co-designed/culturally-tailored manner (Power et al. Citation2022; Ussher et al. Citation2017); as well as improving education for communities, parents and health professionals to better support young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (Metusela et al. Citation2017). It may also be beneficial to utilise now forms of technology (such as social media) to enhance acceptability and reach (Carswell et al. Citation2012; Cordoba et al. Citation2021).

Strengths and limitations of the included studies

A key strength of the studies included in this review was the cultural responsiveness demonstrated by researchers in the research designs and methodologies applied – for example, community involvement in sampling methods and design (Botfield et al. Citation2018; Dean et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Dune et al. Citation2017; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009, Citation2010; Ngum Chi Watts, Liamputtong and Carolan Citation2014; Ngum Chi Watts, McMichael, and Liamputtong Citation2015; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014; Wray, Ussher and Perz Citation2014). While the included studies were assessed as being of relatively strong quality, there are notable limitations. For example, a commonly cited limitation in the studies selected was lack of generalisability across ethnic backgrounds (Botfield et al. Citation2018; Dean et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Dune et al. Citation2017; McMichael and Gifford Citation2009, Citation2010; Ngum Chi Watts, Liamputtong and Carolan Citation2014; Ngum Chi Watts, McMichael and Liamputtong Citation2015; Rawson and Liamputtong Citation2010; Rogers and Earnest Citation2014; Wray, Ussher and Perz Citation2014). There was also minimal use of cultural frameworks/theories in some of the included studies. Health promotion and applied research interventions are more effective if informed by research underpinned by evidence-based approaches and theoretical frameworks (Poobalan et al. Citation2009; Vujcich et al. Citation2021). Future research underpinned by culturally informed theories taking into consideration factors relevant to the target population will increase contextualised understanding of the diverse sociocultural and structural factors that influence young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds’ knowledge, attitudes and access to information/services. Such understandings have the potential to increase efficacy of programmes targeting the SRH needs and literacy of members of this heterogeneous group of young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Strengths and limitations of this review

This review involved a search of five databases and included studies conducted over a 10-year period. The studies reported broadly similar findings, although the authors acknowledge qualitative synthesis of mixed-methods data can be methodologically complex and subjectively influenced by the researcher’s background and experiences. Steps were taken during the review to improve synthesis accuracy, consistency and reliability (Pope, Ziebland and Mays Citation2000) as well as congruency with the original findings reported in included studies.

Only primary research was analysed in this review. The authors appreciate that the inclusion of grey literature (e.g. community/government reports) could have provided greater insights. Some of the included research was more than 10 years old, however, despite this, more recent research had tended to reach similar findings to that undertaken earlier and highlights the continued need for services providers and policy makers to prioritise the development and implementation of contextually-relevant and culturally-informed strategies to address the barriers identified in this review.

Conclusion

Sexual health literacy is a protective factor for the prevention of negative SRH outcomes and enables young people to be more in control of their SRH and rights. Findings from this review suggest that SRH literacy in Australia has remained low over a nearly 10-year period among a heterogeneous group of young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. This suggests we need to do more and do better in providing culturally congruent SRH information, interventions and care to these young people. Consideration of the varied needs and many barriers experienced by young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds must be prioritised with greater consideration given to diversity of cultures and attitudes, and their impact on sexual health literacy. There remains a need for the greater use of culturally informed theory throughout the research process. Outcomes of such research will increase understanding of the intersection between the social and cultural factors affecting sexual health literacy among young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, and inform the development of more culturally-congruent and responsive SRH services.

Acknowledgments

This paper was part of the first author’s Bachelor of Health Science studies, we thank the examiners for their comments and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Much of the data supporting the findings of this study are available in public domain resources and databases. Supporting material described here is available on request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alarcão, V., M. Stefanovska-Petkovska, A. Virgolino, O. Santos, and A. Costa. 2021. “Intersections of Immigration and Sexual/Reproductive Health: An Umbrella Literature Review with a Focus on Health Equity.” Social Sciences 10 (2): 63.https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10020063

- Australian Government. 2018a. Fourth National Sexually Transmissible Infections Strategy 2018-2022. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Australian Government. 2018b. Shaping a nation: Population growth and immigration over time. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Botfield, J. R., C. E. Newman, and A. B. Zwi. 2016. “Young People from Culturally Diverse Backgrounds and their Use of Services for Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs: A Structured Scoping Review.” Sexual Health 13 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH15090

- Botfield, J. R., A. B. Zwi, A. Rutherford, and C. E. Newman. 2018. “Learning about Sex and Relationships among Migrant and Refugee Young People in Sydney, Australia: ‘I Never Got The Talk About the Birds and the Bees.” Sex Education 18 (6): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1464905

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Briscoe, S., A. Bethel, and M. Rogers. 2020. “Conduct and Reporting of Citation Searching in Cochrane Systematic Reviews: A Cross-sectional Study.” Research Synthesis Methods 11 (2): 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1355

- Carswell, K., O. McCarthy, E. Murray, and J. V. Bailey. 2012. “Integrating Psychological Theory Into the Design of an Online Intervention for Sexual Health: The Sexunzipped Website.” JMIR Research Protocols 1 (2): E 16. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.2114

- Cordoba, E., B. Idnay, R. Garofalo, L. M. Kuhns, C. Pearson, J. Bruce, D. S. Batey, et al. 2021. “Examining the Information Systems Success (ISS) of a Mobile Sexual Health App (MyPEEPS Mobile) from the Perspective of very Young Men Who Have Sex with Men (YMSM).” International Journal of Medical Informatics 153: 104529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104529

- Dean, J. A., M. Mitchell, D. Stewart, and J. Debattista. 2017a. “Intergenerational Variation in Sexual Health Attitudes and Beliefs among Sudanese Refugee Communities in Australia.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 19 (1): 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2016.1184316

- Dean, J. A., M. Mitchell, D. Stewart, and J. Debattista. 2017b. “Sexual Health Knowledge and Behaviour of Young Sudanese Queenslanders: A Cross-sectional Study.” Sexual Health 14 (3): 254–260. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH16171

- Dune, T., J. Perz, Z. Mengesha, and D. Ayika. 2017. “Culture Clash? Investigating Constructions of Sexual and Reproductive Health From the Perspective of 1.5 Generation Migrants in Australia using Q Methodology.” Reproductive Health 14 (1): 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0310-9

- Fisher, C. M., A. Waling, L. Kerr, R. Bellamy, P. Ezer, G. Mikolajczak, G. Brown, M. Carman, and J. Lucke. 2019. 6th National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health 2018. (ARCSHS Monograph Series No. 113). Bundooraa: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University.

- Harden, A., and J. Thomas. 2005. “Methodological Issues in Combining Diverse Study Types in Systematic Reviews.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (3): 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570500155078

- Hussein, J., and L. Ferguson. 2019. “Eliminating Stigma and Discrimination in Sexual and Reproductive Health Care: A Public Health Imperative.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 27 (3): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2019.1697103

- Maheen, H., K. Chalmers, S. Khaw, and C. McMichael. 2021. “Sexual and Reproductive Health Service Utilisation of Adolescents and Young People from Migrant and Refugee Backgrounds in High-Income Settings: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis.” Sexual Health 18 (4): 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20112

- Majumdar, D. 2006. “Social Support and Risky Sexual Behavior among Adolescents: The Protective Role of Parents and Best Friends.” Journal of Applied Sociology 23 (1): 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/19367244062300103

- Marino, J. L., L. N. Lewis, D. Bateson, M. Hickey, and S. R. Skinner. 2016. “Teenage Mothers.” Australian Family Physician 45 (10): 712–717.

- McFarland, M. R., and H. B. Wehbe-Alamah. 2019. “Leininger’s Theory of Culture Care Diversity and Universality: An Overview With a Historical Retrospective and a View toward the Future.” Journal of Transcultural Nursing 30 (6): 540–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659619867134

- McMichael, C., and S. M. Gifford. 2009. “It Is Good to Know Now…Before It’s Too Late": Promoting Sexual Health Literacy amongst Resettled Young People with Refugee Backgrounds.” Sexuality & Culture 13 (4): 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-009-9055-0

- McMichael, C., and S. M. Gifford. 2010. “Narratives of Sexual Health Risk and Protection amongst Young People from Refugee Backgrounds in Melbourne, Australia.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 12 (3): 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050903359265

- Metusela, C., J. Ussher, J. Perz, A. Hawkey, M. Morrow, R. Narchal, J. Estoesta, and M. Monteiro. 2017. “In My Culture, We Don’t Know Anything About That”: Sexual and Reproductive Health of Migrant and Refugee Women.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 24 (6): 836–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9662-3

- Mullens, A. B., J. Kelly, J. Debattista, T. M. Phillips, Z. Gu, and F. Siggins. 2018. “Exploring HIV Risks, Testing and Prevention among Sub-Saharan African Community Members in Australia.” International Journal for Equity in Health 17 (1): 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0772-6

- Napier-Raman, S., S. Z. Hossain, M.-J. Lee, E. Mpofu, P. Liamputtong, and T. Dune. 2023. “Migrant and Refugee Youth Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in Australia: A Systematic Review.” Sexual Health 20 (1): 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH22081

- Ngum Chi Watts, M. C., P. Liamputtong, and M. Carolan. 2014. “Contraception knowledge and attitudes: Truths and myths among African Australian teenage mothers in Greater Melbourne, Australia.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 23 (15-16): 2131–2141. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12335

- Ngum Chi Watts, M. C., C. McMichael, and P. Liamputtong. 2015. “Factors Influencing Contraception Awareness and Use: The Experiences of Young African Australian Mothers.” Journal of Refugee Studies 28 (3): 368–387. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feu040

- Nutbeam, D. 2000. “Health Literacy as a Public Health Goal: A Challenge for Contemporary Health Education and Communication Strategies into the 21st Century.” Health Promotion International 15 (3): 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/15.3.259

- Page, M. J., J. E. McKenzie, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, L. Shamseer, et al. 2021. “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 372: N 71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Poobalan, A. S., E. Pitchforth, M. Imamura, J. S. Tucker, K. Philip, J. Spratt, L. Mandava, and E. van Teijlingen. 2009. “Characteristics of Effective Interventions in Improving Young People’s Sexual Health: A Review Of Reviews.” Sex Education 9 (3): 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810903059185

- Pope, C., S. Ziebland, and N. Mays. 2000. “Qualitative Research in Health Care. Analysing Qualitative Data.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 320 (7227): 114–116. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114

- Power, R., J. M. Ussher, A. Hawkey, O. Missiakos, J. Perz, O. Ogunsiji, N. Zonjic, C. Kwok, K. McBride, and M. Monteiro. 2022. “Co-designed, Culturally Tailored Cervical Screening Education with Migrant and Refugee Women in Australia: A Feasibility Study.” BMC Women’s Health 22 (1): 353. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01936-2

- Rawson, H. A., and P. Liamputtong. 2009. “Influence of Traditional Vietnamese Culture on the Utilisation of Mainstream Health Services for Sexual Health Issues by Second-generation Vietnamese Australian young women.” Sexual Health 6 (1): 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1071/sh08040

- Rawson, H. A., and P. Liamputtong. 2010. “Culture and sex education: The Acquisition of Sexual Knowledge for a Group of Vietnamese Australian Young Women.” Ethnicity & Health 15 (4): 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557851003728264

- Rogers, C., and J. Earnest. 2014. “A Cross-Generational Study of Contraception and Reproductive Health Among Sudanese and Eritrean Women in Brisbane, Australia.” Health Care for Women International 35 (3): 334–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2013.857322

- Rogers, C., and J. Earnest. 2015. “Sexual and Reproductive Health Communication among Sudanese and Eritrean Women: An Exploratory Study from Brisbane, Australia.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17 (2): 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2014.967302

- Sørensen, K., S. Van den Broucke, J. Fullam, G. Doyle, J. Pelikan, Z. Slonska, and H. Brand. 2012. “Health Literacy and Public Health: A Systematic Review and Integration of Definitions and Models.” BMC Public Health 12 (1): 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80

- United Nations. 2014. Programme of Action of the International Conference of Population Development - 20th Anniversary Edition. New York: United Nations Population Fund.

- Ussher, J. M., J. Perz, C. Metusela, A. J. Hawkey, M. Morrow, R. Narchal, and J. Estoesta. 2017. “Negotiating Discourses of Shame, Secrecy, and Silence: Migrant and Refugee Women’s Experiences of Sexual Embodiment.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 46 (7): 1901–1921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0898-9

- Viner, R. M., E. M. Ozer, S. Denny, M. Marmot, M. Resnick, A. Fatusi, and C. Currie. 2012. “Adolescence and the Social Determinants of Health.” Lancet 379 (9826): 1641–1652. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4

- Vongxay, V., F. Albers, S. Thongmixay, M. Thongsombath, J. E. W. Broerse, V. Sychareun, and D. R. Essink. 2019. “Sexual and Reproductive Health Literacy of School Adolescents in Lao PDR.” PLoS One 14 (1): e0209675. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209675

- Vujcich, D., G. Brown, J. Durham, Z. Gu, L. Hartley, R. Lobo, L. Mao, et al. 2022. “Strategies for Recruiting Migrants to Participate in a Sexual Health Survey: Methods, Results, and Lessons.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (19): 12213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912213

- Vujcich, D., M. Roberts, G. Brown, J. Durham, Z. Gu, L. Hartley, R. Lobo, et al. 2021. “Are Sexual Health Survey Items Understood as intended by African and Asian Migrants to Australia? Methods, Results and Recommendations for Qualitative Pretesting.” BMJ Open 11 (12): e049010. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049010

- Wang, B., B. Stanton, L. Deveaux, X. Li, V. Koci, and S. Lunn. 2014. “The Impact of Parent Involvement in an Effective Adolescent Risk Reduction Intervention on Sexual Risk Communication and adolescent Outcomes.” AIDS Education and Prevention 26 (6): 500–520. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2014.26.6.500

- Wray, A., J. M. Ussher, and J. Perz. 2014. “Constructions and Experiences of Sexual Health among Young, Heterosexual, Unmarried Muslim Women Immigrants in Australia.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 16 (1): 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2013.833651