Abstract

This review synthesises qualitative research on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake by sexual minority men to provide an overarching conceptualisation of the implementation processes involved. Twenty-four studies—comprising 734 participants from USA, UK, France, Canada, and Taiwan—were synthesised using thematic synthesis. The synthesis elucidates the dual significance of PrEP uptake: (1) risk management: reinforcing relational circumstances, and rebalancing safety and risk; and (2) sexual empowerment: reclaiming health and sexuality and refocusing on sexual fulfillment and intimacy. Overall, the findings show how gay and bisexual men use PrEP to reconcile their antagonistic desires for intimacy and safety by recalibrating protection and reimagining intimacy. This review conceptualises the essence of users’ experiences of PrEP implementation as reconciliation work—the labour and agency in making and remaking practices to manage discontinuities and incongruities—about the new HIV prevention modality. The concept of reconciliation work illustrates how using PrEP influences users’ practices, which in turn, shape the meanings of PrEP use within the community. This work engenders contingent transformations and outcomes beyond HIV protection, encompassing the broader aspects of health and sexuality. Findings support the adoption of more holistic and empowering approaches to sexual health promotion and intervention.

Introduction

The advent of antiretroviral medication as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) represents a significant milestone in biomedical HIV intervention, heralding an epochal shift in the meanings and practices of sexuality and health among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. When used correctly, PrEP is a highly effective method for reducing the risk of sexual exposure to HIV infection among seronegative individuals by taking antiretroviral medication before sexual activity. Despite its clinical efficacy, PrEP adoption among gay and bisexual men had been slow in the first half of the decade since the first PrEP medication (Truvada) received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration in 2012 (van Dijk et al. Citation2021). Although PrEP awareness and acceptance have increased in recent years (Sun et al. Citation2022), there remain concerns about suboptimal uptake and continuance at levels necessary for meaningful population-level reductions in HIV incidence (Sullivan et al. Citation2018).

Much work has examined PrEP uptake and continuance among gay and bisexual men, but largely through relatively static notions of barriers and facilitators (Birnholtz et al. Citation2022; Owens et al. Citation2020). Previous qualitative systematic reviews have consolidated the barriers and facilitators to PrEP adherence among gay and bisexual men at individual and societal levels (Ching et al. Citation2020; Edeza et al. Citation2021) and highlighted PrEP’s positive transformations of sexuality and intimacy (Curley et al. Citation2022; Grov et al. Citation2021). While helpful in identifying salient promises and challenges of PrEP uptake, these reviews stop short of illuminating underlying mechanisms and processes.

Qualitative studies have illustrated how gay and bisexual men incorporate PrEP in their lives and perceive its impact on sexual decision-making and practices (Gafos et al. Citation2019; Hojilla et al. Citation2016; Hughes et al. Citation2018; Koester et al. Citation2017; Malone et al. Citation2018). Through the thematic synthesis of pertinent qualitative studies, this review sought to develop more comprehensive and transferable theoretical insights than those provided in individual studies of how gay and bisexual men implements PrEP and makes it work for them. Such insights are valuable for developing interventions that promote not only PrEP uptake and continuance but also other beneficial outcomes.

Methods

Study selection

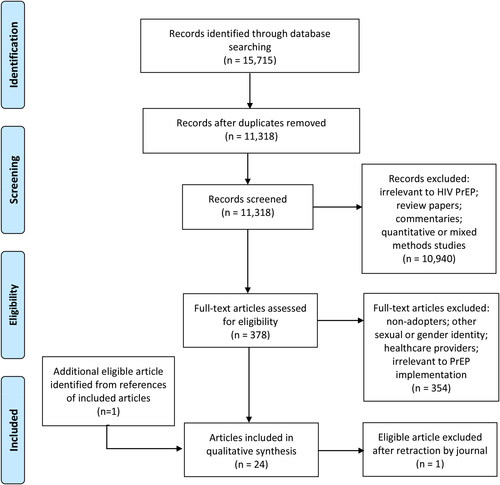

We systematically searched six electronic databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, ERIC, ProQuest, Sociological Abstracts, and PsycArticles) in July 2020 without date restrictions for English peer-reviewed journal articles using ‘PrEP’ OR ‘pre-exposure prophylaxis’ OR ‘Truvada’ AND ‘MSM’ OR ‘men who have sex with men’ OR ‘gay’ OR ‘bisexual’ OR ‘homosexual’ as search terms (see ). We selected only peer-reviewed articles, as their publication in refereed journals implies a level of sufficient quality. Articles not published in English were excluded to ensure that our research team had the language proficiency to accurately assess the articles. We identified 11,318 articles after removing duplicates. Title, abstract, and keyword screening retained 378 articles for full-text assessment by two coders (the author and an associate). One additional article was included after searching the references of eligible articles, while one retracted article was excluded.

Our inclusion criteria were qualitative empirical studies that foregrounded the perspectives and experiences of HIV PrEP uptake beyond the initial adoption decision among gay and bisexual men. We excluded studies narrowly focused on perspectives or experiences leading up to PrEP adoption and those that only examined the practicalities of accessing or taking PrEP. No studies were excluded based on quality assessment to avoid limiting the potential for discovering new insights. The included articles comprised 24 qualitative studies with 734 participants from the USA, the UK, France, Canada, and Taiwan, published in print or online between December 2015 to March 2020 (see ).

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies (n = 24).

Synthesis

Data were extracted and analysed using thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden Citation2008), which we adapted to (a) focus on processual themes by coding for action-based processes rather than topics that typically comprise descriptive themes, and (b) generate an overall line of argument instead of analytical themes. The two coders independently conducted line-by-line coding of concepts (ideas, metaphors, interpretations) about PrEP use presented in the abstract, results, and discussion sections of included studies.

We analysed the studies chronologically by publication date to account for possible shifts in understandings as PrEP became more widely used. As we coded each study, we constantly compared new codes and coded segments to previous ones, modifying and organising them into themes. Each coder maintained a separate set of organised codes and themes. After coding all included studies, we compared and discussed each other’s coding to verify the trustworthiness of our interpretations and achieved a consensus on the most salient themes identified. An overall line of argument was then generated by interpreting the storyline or pattern of sequence, correspondence, and causation among themes within and between studies.

Results

Recalibrating protection: PrEP as risk management

Reinforcing relational circumstances

Studies noted that participants often framed their PrEP uptake in terms of continuity with practices and trajectories preceding its use. PrEP was considered an optimal HIV prevention modality in reinforcing relational circumstances—making users feel safer about the risks that they were taking with their pre-existing or shifting sexual practices and relationships.

Enabling safer condomless sex

Studies highlighted participants’ desire for lower risk condomless sex as the predominant driver of PrEP uptake (Brooks et al. Citation2020), often describing their aversion and struggle to use condoms (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017; Parker et al. Citation2015). Considering the history of inconsistent or no condom use among these men, PrEP provided them with a sensible alternative for HIV protection (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017; Koester et al. Citation2017; Parker et al. Citation2015; Rivierez et al. Citation2018). ‘[I]t’s given me the confidence of having the ability to protect myself in a way that condoms are just not making it in my world’ (Sun et al. Citation2019, 57).

PrEP was especially valuable in bolstering the confidence of participants in regular relationships to maintain condomless sex with their primary partners (or initiate it in the case of serodiscordant couples) by providing a safeguard against HIV. For participants who had condomless sex based on the trust that their partners were seronegative or monogamous, PrEP provided a means of self-protection regardless of whether they were truthful about serostatus or sexual history (Devarajan et al. Citation2020; Hojilla et al. Citation2016; Quinn et al. Citation2020). Given that ‘sexual exclusivity and condom use were almost never renegotiated over time’, PrEP provided HIV protection without any disruption to the silence in situations ‘where it was not possible or desirable to talk about condomless concomitant relationships outside of the couple (and therefore to readapt prevention practices)’ (Mabire et al. Citation2019, 7).

Acquiring extra protection

Another oft-cited reason for PrEP uptake was acquiring extra protection. Many participants considered PrEP an ‘additional layer of protection’ within a larger risk management strategy, encompassing condoms (Brooks et al. Citation2020; Huang et al. Citation2019) and/or other risk-reduction methods (Gafos et al. Citation2019; Hojilla et al. Citation2016; Koester et al. Citation2017; Rivierez et al. Citation2018). Additionally, PrEP was regarded as a ‘safety net’ during occasional slipups and other known unknowns like condom breakage (Brooks et al. Citation2019; Gafos et al. Citation2019; Hojilla et al. Citation2016; Kecojevic et al. Citation2021; Malone et al. Citation2018; Rivierez et al. Citation2018).

PrEP uptake for extra protection was especially salient among participants who were more risk-averse (‘The more preventative medicines there are, the better’; Yang et al. Citation2020, 239), had had episodes of ‘HIV scare’ (near exposure), and with ‘seasons of risk’ (contexts of peak sexual activity) and participation in riskier sex scenes, such as ‘chemsex’ (Hojilla et al. Citation2016; Storholm et al. Citation2017). In these contexts, PrEP flexibly provided both short (on-demand dosing) or longer-term (daily pill) options for users with different risk profiles (Gafos et al. Citation2019).

Rebalancing safety and risk

While participants typically framed their PrEP uptake as congruent with pre-existing practices, studies have also highlighted PrEP’s role as a catalyst for rebalancing safety and risk.

Re-examining acceptable risk

As with their uptake motives, participants’ risk mentalities and condom usage varied both before and after initiating PrEP. Nevertheless, participants’ sexual risk calculus tended to be commonly shaped by the idea of acceptable risk, which was changed by the advent of PrEP (Martinez-Lacabe Citation2019). Many participants described experiencing ‘peace of mind’ from the knowledge and confidence that PrEP dissipates non-acceptable risk, which was largely identified with HIV (Quinn et al. Citation2020; Yang et al. Citation2020). While some participants proclaimed PrEP as ‘miraculous’ (Martinez-Lacabe Citation2019) or ‘protection of the century’ (Hughes et al. Citation2018), most participants were more restrained in that they acknowledged ‘it may not protect me fully from HIV, but it’s going to help’ (Yang et al. Citation2020, 239).

A common narrative across studies was that PrEP uptake invariably entailed reconsidering the use of condoms. This consideration was strongly shaped by individual differences in tolerance of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) vs. the desire for condomless intimacy. While HIV was widely regarded as a non-acceptable risk, participants expressed ambivalence about other STIs if condoms were abandoned when using PrEP (Hughes et al. Citation2018; Orne and Gall Citation2019; Storholm et al. Citation2017). Participants who felt more comfortable with condomless sex while on PrEP tended to view ‘potential exposure to STIs as an acceptable, albeit undesirable, risk when balanced against the drawbacks of condom use’ (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017, 59). For a few participants, however, other STIs could be ‘as bad or worse than HIV… it’s just that HIV is the poster boy for the “bad” STD’ [age 29] (Hughes et al. Citation2018, 393). Taking PrEP strengthened some participants’ resolve to use condoms by reinforcing their cautious mindsets and increasing their awareness of other STIs (Orne and Gall Citation2019; Storholm et al. Citation2017). For several participants, the fear of other STIs became ‘a motivator for selective condom use based on risk perception’ (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017, 59).

Revising safer sex practices

A consistent finding across studies was the overall trend of reduced condom use, despite the large variance in condom use frequency before and after PrEP initiation (Storholm et al. Citation2017). Nevertheless, studies highlighted different patterns of shifts in risk mentalities and adjustments in safer sex practices among participants after PrEP uptake (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017; Gafos et al. Citation2019; Hojilla et al. Citation2016; Hughes et al. Citation2018; Koester et al. Citation2017; Storholm et al. Citation2017). A predominant experience among participants, particularly those who had used condoms more consistently, was the subtle and gradual change in their attitude and usage of condoms that ensued (Gafos et al. Citation2019; Storholm et al. Citation2017). Exemplifying the underlying shift in risk mentality, a participant continued to carry condoms after initiating PrEP but described less pressure to insist on using them in every situation: ‘I don’t want to say I’m throwing caution to the wind, but… I just feel more secure about not being secure’ [age 49, White] (Koester et al. Citation2017, 1307).

Studies have highlighted that other risk-reduction methods (e.g. avoiding internal ejaculation) used during condomless sex while on PrEP augment an incremental shift in risk mentality (Gafos et al. Citation2019; Hojilla et al. Citation2016). Participants mostly revised risk management measures undertaken before PrEP uptake rather than entirely abandon them (Hojilla et al. Citation2016). Before initiating PrEP, participants typically used condoms with casual partners but not trusted or regular ones. After PrEP uptake, many participants continued using condoms with new or unknown partners (Storholm et al. Citation2017), although some participants considered the concurrent use of PrEP and condoms as ‘too safe’ (Puppo et al. Citation2020).

Participants have reported that being on PrEP meant relaxing their rules on serosorting (selecting partners who report being HIV-negative) and strategic positioning (selecting ‘less risky’ positions e.g. insertive anal sex) or switching to biomedical sorting (selecting partners who also take PrEP) when practicing condomless sex (Gafos et al. Citation2019; Hojilla et al. Citation2016; Orne and Gall Citation2019). Observations of adjustments to participants’ safer sex practices highlight the normalisation of condomless sex among PrEP users (Huang et al. Citation2019). Storholm et al. (Citation2017) described the transformation of a participant from using condoms ‘almost like 100% of the time’ to ‘I never use a condom now, ever’ after he and his regular partners started taking PrEP: ‘I kind of stopped using condoms with them. And then once that – that’s just kind of like the domino effect… where I wasn’t using them with people that I didn’t know’ [age 31, White] (740).

Several studies discussed participants’ experiences of a ‘honeymoon period’ of heightened sexual activity, such as condomless sex with multiple partners after initiating PrEP (Hojilla et al. Citation2016; Hughes et al. Citation2018; Koester et al. Citation2017; Storholm et al. Citation2017). The experiences of these participants, who had mostly used condoms inconsistently, provided a stark contrast to the inertia of habituated condom use experienced by other participants who were slow to act on their desires for condomless sex (Koester et al. Citation2017). However, this ‘do whatever I want’ phase was often halted by the experience of one or more STIs and subsequent regret, prompting participants to reconsider their behaviour (Hughes et al. Citation2018; Koester et al. Citation2017). While it is unclear if these participants would have contracted an STI regardless, their situation showed how PrEP shifts users’ fluid sense of safety: ‘waxing during the onset of PrEP use and waning once the novelty wore off and when a negative event, such as a gonorrhoea or Chlamydia diagnosis, occurred’ (Koester et al. Citation2017, 1307).

Pointing to a feedback loop, Hughes et al. (Citation2018) contend that ‘the aftermath of some “risky” sexual encounters became an experiential resource, helping participants determine what they felt was the “right” way to have sex on PrEP’ (392). Beyond sexual risk concerns, the authors highlighted participants’ reflexive monitoring of their sexual relations and ‘navigation of the moral and ethical dimensions of sexual decision-making when using PrEP’ (392).

Reimagining intimacy: PrEP as sexual empowerment

By diminishing the threat of HIV, PrEP holds the potential to neutralise the negativity around sex between men and empower gay and bisexual users to refocus on the positive aspects of their sexuality and reconceptualise sexual intimacy beyond risk management.

Reclaiming health and sexuality

Assuming control of one’s well-being

Participants often characterised their PrEP uptake as empowering and proactive in that it ‘allowed them to be in control and do something for themselves to reduce their risk of HIV’ (Grace et al. Citation2018, 27, emphasis as in original), increased reflexivity (Sun et al. Citation2019), bolstered self-efficacy (Storholm et al. Citation2017) and afforded a sense of self-determination (Brooks et al. Citation2020; Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017). Unlike condoms, PrEP provides control and autonomy for users ‘to protect themselves against HIV at an individual-rather than partner-level’ irrespective of ‘relationship status, power imbalances, or ability and comfort negotiating condoms’ (Quinn et al. Citation2020, 1382).

This ability to self-protect enabled users to assume personal responsibility for one’s own well-being and helped to build resilience among users to adapt to potential sexual health disruptions, counteracting the tendency to self-blame and feel guilty: ‘I no longer have, as soon as I have a doubt about maybe having caught something, to contact my doctor and… justify myself… I no longer feel the guilt I felt before when I went to see my doctor’ (Mabire et al. Citation2019, 8). Beyond HIV prevention, several participants tethered their PrEP uptake to broader notions of holistic or integral self-care that entails making thoughtful, fulfilling, and responsible life decisions (Devarajan et al. Citation2020; Hughes et al. Citation2018; Quinn et al. Citation2020; Sun et al. Citation2019; Yang et al. Citation2020).

Liberating ingrained apprehensions of sex

A predominant experience discussed by participants was how using PrEP liberated ingrained apprehensions surrounding sex and HIV—replacing ‘feelings of worry with feelings of safety’ (Koester et al. Citation2017, 1306) and enabling ‘the kind of sex that you can have’ (Martinez-Lacabe Citation2019, 1125). Participants emphasised how adopting PrEP as a prevention strategy allowed them to alleviate ‘the psychological burden of living with high HIV risk’ (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017, 63), a major source of anxiety in their life (Brooks et al. Citation2019; Schwartz and Grimm Citation2019). ‘[I]t has definitely reduced my anxiety and urgency of needing to be safe… I feel better that I have a way of just knowing and really just being able to relax due to the effectiveness of being on PrEP’ (Kecojevic et al. Citation2021, 1887). Being able to live without that stress and fear was perceived as very liberating (Schwartz and Grimm Citation2019) in making participants feel much safer and ‘more comfortable connecting with guys physically’ (Storholm et al. Citation2017, 743).

Participants further described forming new conceptualisations of their sexual selves that involved ‘drawing sharp contrasts to previously held perceptions of constrained agency’ and relinquishing ‘notions of seroconversion as an inevitable outcome of their sexuality’ (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017, 60). Studies highlighted ingrained apprehensions of gay sex engendered by the cultural construction of HIV as punishment for homosexual promiscuity. ‘Growing up in the late ‘80s, early ‘90s… it was drilled into our heads: “If you have sex you are going to die. Especially if you have gay sex, you are going to catch AIDS and you will die!”’ [age 33] (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017, 60). PrEP disconnected sex between men from the harm-reduction model of HIV that appropriates shame and fear to deter ‘unsafe’ sex (Dubov et al. Citation2018), and which pathologises queer sexuality, condomless sex, and people living with HIV. As one participant said, ‘PrEP helped me feel not so shameful with men. It made me feel like I reclaimed a part of my sexuality that had been co-opted from me a long time ago by the stigma of HIV and antiqueer forces’ (Sun et al. Citation2019, 56).

Participants portrayed PrEP as a liberating technology that reconciled their desire for unbridled sex and strong aversion to infection (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017; Gafos et al. Citation2019; Martinez-Lacabe Citation2019; Quinn et al. Citation2020; Storholm et al. Citation2017). ‘I feel a lot more free to do whatever I feel like… it gives me a sense of control that I can be with whoever I want, sleep with whoever the fuck I want’ [age 28] (Martinez-Lacabe Citation2019, 1125). These practices of freedom included an impetus or openness to ‘bottoming’ (receptive anal sex) among men who had previously avoided it out of concern for increased HIV risk (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017) and dating or having sex with HIV seropositive partners for the first time (Storholm et al. Citation2017).

The potential for PrEP to facilitate sexual relationships between serodiscordant partners by reducing HIV stigma and anxiety was especially salient for participants who were already in serodiscordant relationships before initiating PrEP (Yang et al. Citation2020). Although studies have highlighted an increased willingness to consider serodiscordant relationships among many participants (Devarajan et al. Citation2020; Sun et al. Citation2019), being on PrEP did not necessarily make all participants felt comfortable with having sex with people with HIV, particularly if they had previously been resistant to the idea (Quinn et al. Citation2020).

While participants across studies mostly gave positive evaluations of their sexual experiences after PrEP uptake, some expressed ambivalence and scruples—stemming from internalised stigma about promiscuity rather than HIV/STI anxiety—about their more liberalised sexual attitudes and behaviours (Brooks et al. Citation2020; Gafos et al. Citation2019). ‘I came off PrEP because it was a reason just to have more sex. I didn’t want that anymore’ (Kecojevic et al. Citation2021, 1887).

Refocusing on sexual fulfilment and intimacy

Participants’ constructions of quality and fulfilling sexual life after PrEP uptake were mostly centred on ‘emancipation from recurrent constraints’ (Mabire et al. Citation2019, 7)—fear and condoms—that compromised pleasure and intimacy.

Backgrounding protection and foregrounding pleasure

PrEP backgrounded protection by providing an unobtrusive safety net that relieved users from worrying about slipping up during sex. Gone were the tension between fear and pleasure during sexual practices with increased HIV risk (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017), or the persistent anxiety that some participants experienced even when using condoms (Quinn et al. Citation2020). PrEP-induced reduction of fear and anxiety allowed users to become ‘more evolved sexually’ and had an ‘awesome’ impact on sexual enjoyment (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017; Devarajan et al. Citation2020; Hughes et al. Citation2018; Mabire et al. Citation2019; Quinn et al. Citation2020; Rivierez et al. Citation2018; Storholm et al. Citation2017).

PrEP also foregrounded pleasure by engendering ‘a positive feeling of serenity’ (Mabire et al. Citation2019, 7) that enabled users to be fully present (‘giving your all’; Hughes et al. Citation2018, 394) during the sexual experience and ‘feel more connected and good about what I’m doing’ (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017, 60). ‘Now I get to deal with what I feel are actually important issues about sex, like whether or not I enjoy it and whether or not my partner is enjoying it’ [age 26] (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017, 60). This foregrounding pleasure also meant greater spontaneity and not compromising or holding back on particular forms of sexual expression (e.g. internal ejaculation) out of safety concerns (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017; Mabire et al. Citation2019; Quinn et al. Citation2020).

Rehabilitating sexual intimacy without condoms

Participants’ descriptions of improvements to relationship quality and fulfillment from ‘the kind of sex that you can have’ (Martinez-Lacabe Citation2019, 1125) were predominantly threaded through condomless intimacy. Participants often reported physical discomfort with condoms (lack of sensitivity and inability to maintain an erection), which interfered with sexual functioning (longer penetration, ability to have anal insertive sex or physical pleasure) and sexual satisfaction (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017; Devarajan et al. Citation2020; Hughes et al. Citation2018; Quinn et al. Citation2020; Rivierez et al. Citation2018). After ceasing to use condoms, a participant conceded, ‘(Sex) has gotten way better. It has nothing to do with the way it was before… I said to myself, for all these years I had sex and I was only faking it (pleasure)’ (Rivierez et al. Citation2018, 51).

Beyond physical pleasure, participants often cited the desire for more intimate and emotionally satisfying sex involving fluid exchange and deeper connection with their partner as a major reason for starting PrEP (Dubov et al. Citation2018). A participant described the enhanced connection of not having a condom on as ‘just so much more intimate that I’m actually giving my body to somebody and letting them cum inside me. I think that’s how we’re wired’ [age 48] (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017, 59).

Participants’ accounts illustrate condomless sex and internal ejaculation—the antithesis of traditional safer sex norms—become rehabilitated by PrEP as natural and authentic sexual intimacy between men. Some participants compared PrEP to the birth control pill, suggesting that being on PrEP allowed them to have exciting and pleasurable sex without the need for condoms, which they saw as a way to regain a sense of normalcy (Grace et al. Citation2018). Several participants who had previously used condoms more routinely reflected that being on PrEP had led them to reimagine condomless sex (Gafos et al. Citation2019; Hughes et al. Citation2018; Koester et al. Citation2017; Martinez-Lacabe Citation2019). ‘I am really, genuinely surprised… a few years ago… I would have just said… sex with condoms is totally fine…. Whereas now… I actually think a rubber makes [a] huge difference’ [age 54] (Martinez-Lacabe Citation2019, 1124).

For participants in serodiscordant relationships, PrEP was a means of validating their relationships and normalising sex with their partners by putting them and their partners’ minds at ease to engage in ‘real sex’ (Collins, McMahan, and Stekler Citation2017; Hojilla et al. Citation2016). Additionally, taking PrEP allowed the seronegative partner to demonstrate solidarity and commitment to their seropositive partner (Yang et al. Citation2020).

Discussion

The overall line of argument developed in this synthesis is that PrEP uptake by gay and bisexual men beyond the initial adoption decision constitutes a form of implementation and social shaping of practices that entails reconciliation work. This work refers to the agentic effort by men to resolve the incongruities of their intimacy needs and the desire for safety, as well as attune themselves to new and modified practices. As an HIV prevention modality, PrEP was operationalised by gay and bisexual men across the studies as a means of reinforcing relational circumstances, enabling safer condomless sex, and acquiring extra protection. As these men assimilated PrEP into their lives, it provided the catalyst for rebalancing safety and risk through re-examining acceptable risk and revising safer sex practices. By mitigating the threat of HIV, PrEP empowered men to reclaim health and sexuality by assuming control of their well-being and liberating ingrained apprehensions of sex. Freed from this constraint to sexual enjoyment, men got to improve their sexual quality of life by refocusing on sexual fulfillment and intimacy. Taken together, reconciliation work illustrates how using PrEP influences the practices of gay and bisexual users, which in turn, shape the meanings of PrEP use within the community.

Several studies, particularly those conducted early during PrEP rollout, addressed the potential for PrEP to trigger ‘risk compensation’ or increased sexual behaviours with a higher risk of HIV/STI transmission, thereby undermining its benefits. Participants (and authors) mostly highlighted that the disinhibition triggered by PrEP was largely manifested as feelings of relief during sex or short-lived bursts of sexual activity after initial use. Almost all the included studies suggested that discourses of risk-taking and risk compensation cannot fully represent the experiences of PrEP users. Instead of risk compensation based on a zero-sum sexual risk calculus, our synthesis explicates the salient patterning of gay and bisexual users’ sexual decision-making and practices as appropriating PrEP to realise intimacy desires while shielding themselves from the attendant HIV risk. The narrative of risk compensation and similar sex-negative rhetoric of risky sexual behaviour represents an outdated and harmful approach to gay sexual health (Yeo Citation2021), as exemplified by the included studies that illustrate participants’ struggles with such a homonegative cultural logic and the notion of condom use as a moral code for responsible gay sexual conduct.

This review enhances our understanding of the implementation and outcomes of PrEP uptake by gay and bisexual men. Consistent with previous reviews, it notes that PrEP uptake had benefits beyond HIV prevention, including reduced sexual anxiety, greater self-efficacy, lessened HIV stigma, and better quality of sexual life. Our synthesis provides three additional insights, however. First, the outcomes of PrEP uptake were neither universally experienced nor merely a confluence of factors, but contingent on the dynamic and situated implementation process. Second, positive transformations associated with PrEP implementation emanated from users’ purposive and directed efforts in adapting their thinking, actions, and organisation of sex after PrEP uptake. Third, changes in sexual practices after PrEP uptake tended to be gradual and incremental, reflecting PrEP’s role in facilitating pre-existing sexual desires and relational goals.

Our findings support a paradigm shift in sexual health programming and research, moving away from a disease-focused approach centred on HIV/STI and sexual risk-taking, towards a people-centred approach emphasising holistic and empowering notions of health and sexuality. As this review elucidates, PrEP empowers users to assume greater awareness, control, and responsibility over their sexual health. Greater attention is warranted to promote sexually empowering pedagogy and messages about PrEP uptake, alongside programmes that address the link between sexual health and internalised stigma, discrimination, and trauma.

Limitations

Despite following a systematic searching procedure, it is possible that not all relevant studies were identified, especially since only peer-reviewed articles published in English were included. Given the characteristics of the included studies, our findings primarily reflect the situated contexts of cisgender gay men in Western societies where PrEP was comparatively accessible. The implementation experiences came largely from innovators and early adopters during the early PrEP medication rollout, many of whom participated in PrEP trials and demonstration projects. These participants typically underwent regular HIV/STI testing and health checks, which may have prompted their discussion of increased sexual health awareness and engagement after taking PrEP. Further primary research is needed to compare PrEP implementation and outcomes among a more diverse sample of users, including more recent waves of users who now constitute the early majority.

Conclusion

Moving beyond barriers and facilitators, this synthesis conceptualises PrEP implementation among gay and bisexual men as the work of reconciling their antagonistic desires for intimacy and safety. These men incorporated PrEP into their daily lives as a safety net against HIV, making them feel safer about the risks they took in sexual relationships, which facilitated a shift in their sexual health self-care and related practices. Through recalibrating risk and asserting self-protection as they brought PrEP into operation, these men became empowered to embrace their sexuality and focus on pleasure and intimacy with greater serenity and confidence.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to Tsz Hang Chu for assisting with the selection and synthesis of studies, and Yue Huang for helping with database searches.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Birnholtz, J., A. Kraus, S. Schnuer, L. Tran, K. Macapagal, and D. A. Moskowitz. 2022. “Oh, I Don’t Really Want to Bother with That:” Gay and Bisexual Young Men’s Perceptions of Barriers to PrEP Information and Uptake.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 24 (11): 1548–1562. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2021.1975825

- Brooks, R. A., O. Nieto, A. Landrian, and T. J. Donohoe. 2019. “Persistent Stigmatizing and Negative Perceptions of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Users: Implications for PrEP Adoption among Latino Men Who Have Sex with Men.” AIDS Care 31 (4): 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1499864

- Brooks, R. A., O. Nieto, A. Landrian, A. Fehrenbacher, and A. Cabral. 2020. “Experiences of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)–Related Stigma among Black MSM PrEP Users in Los Angeles.” Journal of Urban Health 97 (5): 679–691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00371-3

- Ching, S. Z., L. P. Wong, M. A. B. Said, and S. H. Lim. 2020. “Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Adherence Among Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM).” AIDS Education and Prevention 32 (5): 416–431. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2020.32.5.416

- Collins, S. P., V. M. McMahan, and J. D. Stekler. 2017. “The Impact of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Use on the Sexual Health of Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Qualitative Study in Seattle, WA.” International Journal of Sexual Health 29 (1): 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2016.1206051

- Curley, C. M., A. O. Rosen, C. B. Mistler, and L. A. Eaton. 2022. “Pleasure and PrEP: A Systematic Review of Studies Examining Pleasure, Sexual Satisfaction, and PrEP.” Journal of Sex Research 59 (7): 848–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.2012638

- Devarajan, S., J. M. Sales, M. Hunt, and D. L. Comeau. 2020. “PrEP and Sexual Well-Being: A Qualitative Study on PrEP, Sexuality of MSM, and Patient-Provider Relationships.” AIDS Care 32 (3): 386–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1695734

- Dubov, A., P. Galbo, F. L. Altice, and L. Fraenkel. 2018. “Stigma and Shame Experiences by MSM Who Take PrEP for HIV Prevention: A Qualitative Study.” American Journal of Men’s Health 12 (6): 1843–1854. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318797437

- Edeza, A., E. Karina Santamaria, P. K. Valente, A. Gomez, A. Ogunbajo, and K. Biello. 2021. “Experienced Barriers to Adherence to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention among MSM: A Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography of Qualitative Studies.” AIDS Care 33 (6): 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1778628

- Gafos, M., R. Horne, W. Nutland, G. Bell, C. Rae, S. Wayal, M. Rayment, A. Clarke, G. Schembri, R. Gilson, et al. 2019. “The Context of Sexual Risk Behaviour Among Men Who Have Sex with Men Seeking PrEP, and the Impact of PrEP on Sexual Behaviour.” AIDS and Behavior 23 (7): 1708–1720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2300-5

- Grace, D., J. Jollimore, P. MacPherson, M. J. Strang, and D. H. Tan. 2018. “The Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis-Stigma Paradox: Learning from Canada’s First Wave of PrEP Users.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 32 (1): 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2017.0153

- Grov, C., D. A. Westmoreland, A. B. D’Angelo, and D. W. Pantalone. 2021. “How Has HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Changed Sex? A Review of Research in a New Era of Bio-Behavioral HIV Prevention.” Journal of Sex Research 58 (7): 891–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1936440

- Hojilla, J. C., K. A. Koester, S. E. Cohen, S. Buchbinder, D. Ladzekpo, T. Matheson, and A. Y. Liu. 2016. “Sexual Behavior, Risk Compensation, and HIV Prevention Strategies Among Participants in the San Francisco PrEP Demonstration Project: A Qualitative Analysis of Counseling Notes.” AIDS and Behavior 20 (7): 1461–1469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1055-5

- Huang, P., H.-J. Wu, C. Strong, F.-M. Jan, L.-W. Mao, N.-Y. Ko, C.-W. Li, C.-Y. Cheng, and S. W.-W. Ku. 2019. “Unspeakable PrEP: A Qualitative Study of Sexual Communication, Problematic Integration, and Uncertainty Management among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Taiwan.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 47 (6): 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2019.1693608

- Hughes, S. D., N. Sheon, E. V. W. Andrew, S. E. Cohen, S. Doblecki-Lewis, and A. Y. Liu. 2018. “Body/Selves and Beyond: Men’s Narratives of Sexual Behavior on PrEP.” Medical Anthropology 37 (5): 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2017.1416608

- Kecojevic, A., Z. C. Meleo-Erwin, C. H. Basch, and M. Hammouda. 2021. “A Thematic Analysis of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) YouTube Videos.” Journal of Homosexuality 68 (11): 1877–1898. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2020.1712142

- Koester, K., R. K. Amico, H. Gilmore, A. Liu, V. McMahan, K. Mayer, S. Hosek, and R. Grant. 2017. “Risk, Safety and Sex among Male PrEP Users: Time for a New Understanding.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 19 (12): 1301–1313. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1310927

- Mabire, X., C. Puppo, S. Morel, M. Mora, D. Rojas Castro, J. Chas, E. Cua, C. Pintado, M. Suzan-Monti, B. Spire, et al. 2019. “Pleasure and PrEP: Pleasure-Seeking Plays a Role in Prevention Choices and Could Lead to PrEP Initiation.” American Journal of Men’s Health 13 (1): 1557988319827396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988319827396

- Malone, J., J. L. Syvertsen, B. E. Johnson, M. J. Mimiaga, K. H. Mayer, and A. R. Bazzi. 2018. “Negotiating Sexual Safety in the Era of Biomedical HIV Prevention: Relationship Dynamics among Male Couples Using Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 20 (6): 658–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1368711

- Martinez-Lacabe, A. 2019. “The Non-Positive Antiretroviral Gay Body: The Biomedicalisation of Gay Sex in England.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 21 (10): 1117–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2018.1539772

- Orne, J., and J. Gall. 2019. “Converting, Monitoring, and Policing PrEP Citizenship: Biosexual Citizenship and the PrEP Surveillance Regime.” Surveillance & Society 17 (5): 641–661. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i5.12945

- Owens, C., R. D. Hubach, D. Williams, E. Voorheis, J. Lester, M. Reece, and B. Dodge. 2020. “Facilitators and Barriers of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Uptake Among Rural Men Who Have Sex with Men Living in the Midwestern U.S.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 49 (6): 2179–2191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01654-6

- Parker, S., P. A. Chan, C. E. Oldenburg, M. Hoffmann, J. Poceta, J. Harvey, E. K. Santamaria, R. Patel, K. I. Sabatino, and A. Nunn. 2015. “Patient Experiences of Men Who Have Sex with Men Using Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Infection.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 29 (12): 639–642. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2015.0186

- Puppo, C., B. Spire, S. Morel, M. Génin, L. Béniguel, D. Costagliola, J. Ghosn, X. Mabire, J. M. Molina, D. Rojas Castro, et al. 2020. “How PrEP Users Constitute a Community in the MSM Population through Their Specific Experience and Management of Stigmatization. The Example of the French ANRS-PREVENIR Study.” AIDS Care 32 (sup2): 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1742863

- Quinn, K. G., E. Christenson, M. T. Sawkin, E. Hacker, and J. L. Walsh. 2020. “The Unanticipated Benefits of PrEP for Young Black Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men.” AIDS and Behavior 24 (5): 1376–1388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02747-7

- Rivierez, I., G. Quatremere, B. Spire, J. Ghosn, and D. Rojas Castro. 2018. “Lessons Learned from the Experiences of Informal PrEP Users in France: Results from the ANRS-PrEPage Study.” AIDS Care 30 (sup2): 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1468014

- Schwartz, J., and J. Grimm. 2019. “Stigma Communication Surrounding PrEP: The Experiences of A Sample of Men Who Have Sex With Men.” Health Communication 34 (1): 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1384430

- Storholm, E. D., J. E. Volk, J. L. Marcus, M. J. Silverberg, and D. D. Satre. 2017. “Risk Perception, Sexual Behaviors, and PrEP Adherence Among Substance-Using Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Qualitative Study.” Prevention Science 18 (6): 737–747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0799-8

- Sullivan, P. S., A. J. Siegler, P. S. Sullivan, and A. J. Siegler. 2018. “Getting Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to the People: Opportunities, Challenges and Emerging Models of PrEP Implementation.” Sexual Health 15 (6): 522–527. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH18103

- Sun, C. J., K. M. Anderson, K. Toevs, D. Morrison, C. Wells, and C. Nicolaidis. 2019. “Little Tablets of Gold”: An Examination of the Psychological and Social Dimensions of PrEP Among LGBTQ Communities.” AIDS Education and Prevention 31 (1): 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2019.31.1.51

- Sun, Z., Q. Gu, Y. Dai, H. Zou, B. Agins, Q. Chen, P. Li, J. Shen, Y. Yang, and H. Jiang. 2022. “Increasing Awareness of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Willingness to Use HIV PrEP among Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Global Data.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 25 (3): e25883. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25883

- Thomas, J., and A. Harden. 2008. “Methods for the Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 8 (1): 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- van Dijk, M., J. B. F. de Wit, T. E. Guadamuz, J. E. Martinez, and K. J. Jonas. 2021. “Slow Uptake of PrEP: Behavioral Predictors and the Influence of Price on PrEP Uptake Among MSM with a High Interest in PrEP.” AIDS and Behavior 25 (8): 2382–2390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03200-4

- Yang, C., N. Krishnan, E. Kelley, J. Dawkins, O. Akolo, R. Redd, A. Olawale, C. Max-Browne, L. Johnsen, C. Latkin, et al. 2020. “Beyond HIV Prevention: A Qualitative Study of Patient-Reported Outcomes of PrEP among MSM Patients in Two Public STD Clinics in Baltimore.” AIDS Care 32 (2): 238–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1622639

- Yeo, T. E. D. 2021. “Safer Sex.” In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, edited by George Ritzer. Malden: Blackwell Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeoss007.pub2