?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Access to early-stage equity financing is vital to the growth of high-potential new ventures. To understand how entrepreneurs obtain external financing, researchers have studied the effectiveness of different signals that entrepreneurs send to investors. In this paper, we provide an overview of current research that uses signaling theory to study the likelihood and success of obtaining funding from angel investors and venture capitalists. The content analysis reveals that empirical research has well explored the signaling value of grants, prior investments, and the human and social capital of the firm to early-stage equity investors. However, we find that the literature on signaling effects on early-stage equity investors is fragmented and undertheorized. We note that while there has been an increase in the number of studies using signaling theory to explain success in obtaining early-stage equity financing, the theory remains underutilized, despite its suitability for this particular area of research. We describe the core ideas of signaling theory and how researchers have applied them in the context of venture capital and angel investing. We discuss how this stream of research can build on and extend signaling theory and highlight promising avenues for future research.

1. Introduction

When pursuing ventures with high growth potential, entrepreneurs search for early equity financing to help fuel their endeavors. Angel investors (AIs) and venture capitalists (VCs) are considered to be the most important sources of external equity financing, representing over 90% of the total early-stage investment market (EBAN Citation2021). These two groups offer financial and non-financial resources, such as advice (Amornsiripanitch, Gompers, and Xuan Citation2019), in an effort to maximize the performance of new ventures. As such, they are pivotal to the early-stage financing of growing ventures (Bellavitis et al. Citation2016; Harrison, Botelho, and Mason Citation2016). Numerous researchers have tried to unpack how entrepreneurs successfully obtain early-stage equity investment, recognizing that the inability to secure external investment is one of the biggest obstacles to the growth of high-potential new ventures (Lee Citation2014).

Signaling theory has shown great potential in explicating early-stage equity investor investment decisions (Bernstein, Korteweg, and Laws Citation2017; Payne et al. Citation2009). Signaling theory (Spence Citation1973) aims to explain how the signal senders’ attributes and actions influence the signal receivers’ decisions under conditions of information asymmetry (Connelly et al. Citation2011; Spence Citation2002). Therefore, this theory is very well suited to explain early-stage investor decisions, which are typically made under conditions of scarcity of reliable information about a venture (Plummer, Allison, and Connelly Citation2016) and high market uncertainty (Kollmann and Kuckertz Citation2010).

There has been an increase in the number of studies using signaling theory to explain success in obtaining early-stage equity financing. The majority of these studies focused on estimating the empirical impact of signals believed to be linked to the firm’s future prospects in fundraising success. Unfortunately, in much of the research on signaling to early-stage equity investors the theory has been applied rather loosely. Bergh et al. (Citation2014) argued that increasing theoretical rigor in research that draws from signaling theory would require, at a minimum, unambiguous identification of the key elements of signaling theory – signalers, receivers, signal with corresponding unobserved quality, and specifics of the signaling context. In addition, researchers should define the relevant characteristics of the signals and explicate how the signals studied distinguish between low and high-quality prospects. A lack of an all-encompassing, coherent conceptual framework of signaling to early-stage equity investors has resulted in little theoretical development and increased fragmentation of the signaling literature in entrepreneurship. As a result, signaling theory remains underutilized, even though it is an appropriate theoretical framework for explaining investor decisions and the success of entrepreneurs in raising early external financing (Drover, Wood, and Corbett Citation2018). Greater clarity on how signaling theory can be employed in research on early-stage equity investing can aid further discovery and possibly prevent stagnation in the entrepreneurship literature using signaling theory.

In this review, we focus on signaling to the two most important sources of external early-stage financing for high growth potential ventures: AIs and VCs (De Clercq et al. Citation2006). Although these two types of investors differ in terms of the source of investment funds, both provide financial and non-financial investments and work closely with entrepreneurs to maximize the venture’s growth prospects (Bessière, Stéphany, and Wirtz (Citation2020), Drover et al. (Citation2017), Cohen (Citation2013)). With the advent of angel groups, the decision-making process, investment size, and stage of the ventures in which AIs invest have become increasingly similar to those of VCs (Mason, Botelho, and Harrison Citation2019). Although it is not uncommon for AIs and VCs to cooperate via referrals or co-investment throughout different financing stages (Harrison and Mason Citation2000; Drover, Wood, and Zacharakis Citation2017), AIs increasingly represent an alternative source of financing to VCs (Hellmann, Schure, and Vo Citation2021) as a result of the greater financial capacity of angel groups (Mason, Botelho, and Harrison Citation2019). Because of the many similarities and interrelatedness between these two groups of investors, they have often been analyzed as a homogeneous group of outside equity investors in empirical research (e.g., Epure and Guasch Citation2020; Meuleman and De Maeseneire Citation2012; Söderblom et al. Citation2015), despite the reported differences in the average size of investment, stage of investment, style of governance and range of investment motives and goals (e.g., Bellavitis et al. Citation2016; Baty and Sommer Citation2002; De Clercq and Sapienza Citation2006; Johnson and Sohl Citation2012). This mix of similarities and differences suggests that it is reasonable for studies on early-stage equity investing to examine these two types of investors together, while remaining observant of the differences between the two groups (Wiltbank Citation2005; Hsu et al. Citation2014).

In light of the above, the purpose of this study is to systematically review and synthesize the research on signaling to AIs and VCs. Our goal is to describe the core ideas of signaling theory and how they have been applied in the context of early-stage equity financing. We provide a holistic overview of the current state of knowledge and identify arising and unexplored questions in the literature. A unique viewpoint of this review is that we build it around the key elements of signaling theory, rather than around investor groups as previous review has done (Colombo Citation2021). Theory is an especially useful foundation for organizing and consolidating empirical research that is fragmented, dispersed or diverse (Colquitt and Zapata-Phelan Citation2007), such as the research on signaling in the context of entrepreneurial financing. This perspective is valuable, as a solid theoretical foundation and guidance facilitate research that not only builds on theory, but also expands on it to effectively inform practice (Wang, Gibson, and Zander Citation2020). While a recent review on the topic (Colombo Citation2021) has expanded our understanding of how signaling depends on the specific equity investment context (ranging from a noisy crowdfunding environment to a less noisy IPO environment), our review brings signaling theory to the fore. We bring attention to some elements of the initial version of signaling theory (Spence Citation1973) and its further developments (Spence Citation2007, Citation2002) that have not received sufficient attention in entrepreneurship research to date, but could enrich future investigations of early-stage equity financing. We also discuss current applications of the theory in the context of venture capital and angel investing. Finally, we base our suggestions for future research on untapped opportunities in the application of signaling theory, emerging trends in entrepreneurial financing literature, and current developments in related management research.

This study contributes to the advancement of the early-stage external financing literature in several ways. First, it clarifies key elements of signaling theory in a way that facilitates application of the theory to the context of early-stage equity investing. Second, it highlights the current state of research and identifies emerging research directions. Third, it identifies potential lines of inquiry for future entrepreneurship studies drawing on signaling theory.

1.1. Signaling theory and entrepreneurial finance

Signaling theory (Spence Citation1973, Citation2002) aims to explain signal senders’ behaviors and signal receivers’ decisions under conditions of information asymmetry. Although the theory was originally developed in the context of the labor market (Spence Citation1973), it has proven applicable to a wide range of organizational contexts characterized by information asymmetries (Connelly et al. Citation2011). While the party with an information advantage (signaler) engages in signaling, the party with an information disadvantage (receiver) engages in screening (Stiglitz Citation1975). The function of signaling and screening is to reduce the information asymmetry around the signaler’s unobservable but relevant characteristics and thereby to improve the signal receiver’s decision-making.

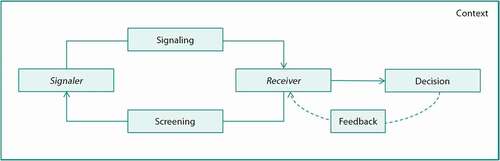

An important characteristic of signaling theory is the recognition of the function of the signal receiver’s beliefs about the relationship between signals and performance. These beliefs not only influence the signalers’ signaling decisions, but also drive their self-selection into or out of a particular market (Spence Citation1973). Signalers can only benefit from signaling if they produce signals to which signal receivers pay attention based on perceived relevance (Gulati and Higgins Citation2003; Drover, Wood, and Corbett Citation2018). As most signals can be altered and used selectively to influence the receiver’s decisions, signal receivers place more value on signals that are not only informative but also costly (in terms of money, time, and/or effort), as this means that they are less likely to be subject to manipulation by the signal sender (Spence Citation1973). However, if signalers do send misleading signals, signal receivers learn over time to ignore them. This is because signal receivers’ beliefs are updated via market information feedback mechanisms. In this context, some previously informative signals may be deemed uninformative due to their lack of relationship to performance or their inability to discriminate between high-quality and low-quality signalers (Spence Citation1973). The relationships between the main elements of signaling theory are shown in .

Signaling theory has proven to be widely applicable in the field of entrepreneurial financing. It has been used to study various forms of equity and debt financing of ventures ranging widely in their life-cycle (Connelly et al. Citation2011). In particular, in early-stage equity investing, entrepreneurs or firms (signalers) convey information about underlying, unobservable qualities and intentions through signals sent to investors (receivers), who in turn interpret and use the information in their decision-making process. In new venture investing, signals provide information about the potential (non-)performance of the new venture (quality signals) and potential hazards resulting from the entrepreneur’s behavior (intent signals).

The biggest risk faced by both investors and high-quality prospects is the risk of signal manipulation by low-quality prospects (Akerlof Citation1970). This risk is exacerbated in early-stage financing because many of the signals on which investors must rely are ambiguous, relatively inexpensive, and easy to imitate (Momtaz Citation2021). To minimize this risk, investors in the preinvestment phase exercise screening efforts and may even pool the resources relevant for evaluating investment opportunities (Bellavitis, Kamuriwo, and Hommel Citation2019; Zacharakis and Shepherd Citation2007). Investors’ screening efforts encourage signaling, which can separate high‐quality prospects from their poor‐quality counterparts (Bellavitis, Kamuriwo, and Hommel Citation2019). This is because higher quality ventures can afford to send more informative and reliable signals to investors that are difficult to mimic by lower quality ventures (Valliere Citation2011).

Investors’ screening criteria change as entrepreneurs move through the investment process, which may involve business plans, pitches, meetings, and negotiations (Fried and Hisrich Citation1994; Paul, Whittam, and Wyper Citation2007). Moreover, they are influenced by contextual factors such as investor networks, syndicates, and platforms (Bernstein, Korteweg, and Laws Citation2017; Carpentier and Suret Citation2015; Gregson, Mann, and Harrison Citation2013), as well as the institutional environment and market characteristics (Bellavitis, Kamuriwo, and Hommel Citation2019; Bertoni, D’Adda, and Grilli Citation2016).

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The Methodology section describes the process of generating and selecting articles for in-depth review and presents a brief descriptive analysis of the evolution of the literature on signaling to AIs and VCs. The Results section provides a definition and identification of the three key elements of signaling theory (signal senders, signals, and signal receivers) and how they have been applied in the selected literature. The section on Future Research Directions highlights gaps and emerging trends in the literature and points to insights from related signaling literature that could benefit the further development of this research stream. The final section concludes with a discussion of the limitations and contributions of this paper.

2. Methodology

2.1. Systematic literature review procedure

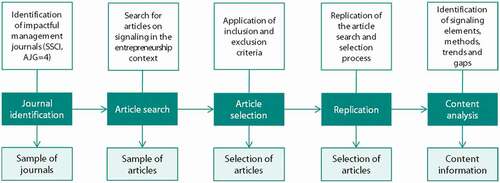

To generate the initial pool of research to be analyzed, we followed the recommendations of Kunisch et al. (Citation2018) for conducting rigorous literature reviews. To identify impactful entrepreneurship literature drawing on signaling theory, we searched Web of Science, which allows access to leading journals in the field of social sciences. To ensure that our search covered a broad range of literature using signaling theory, we searched for the term “signal*” in the article’s title, abstract, author keywords, or keywords plus of the leading entrepreneurship journals (Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Journal of Business Venturing, Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, Venture Capital), and the term “signal*” or “screening” together with the term “entrepreneur*” or “founder” or “start$up” in the leading management and finance journals (Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review, Administrative Science Quarterly, Journal of International Business Studies, Journal of Management, Management Science, Organization Science, Strategic Management Journal, Journal of Finance, Journal of Financial Economics, Review of Financial Studies, Research Policy, Academy of Management Annals, British Journal of Management, Business Ethics Quarterly, Journal of Management Studies, Journal of Product Innovation Management). In selecting journals, we were guided by the Academic Journal Guide (AJG), which ranks a broad range of peer-reviewed journals on impact based on expert judgment and informed by journal metrics. The journals included in our list were all considered leading journals (AJG = 4), with the exception of Venture Capital, which was included because of its importance in the (sub)field of entrepreneurial finance. We searched articles published between 2001 and 2020 (see ). The search returned 176 results, of which 93 represented articles published in the four entrepreneurship journals and 83 represented articles published in the 15 finance and management journals over the span of 20 years.

Table 1. Article search strategy

Next, we defined our article exclusion criteria. We excluded articles that did not pertain to the field of entrepreneurship (e.g., trading), did not focus on equity investing (e.g., loan financing), or focused on later stage equity investing (IPO investing, mergers and acquisitions) or crowdfunding. Articles that did not include the term term “signal*” but did include the term “screening” in the article’s title, abstract, author keywords, or keywords plus were included if authors made reference to signaling in the body of the research. In case of doubt, we read the methodology section of the article to determine whether the article fit our inclusion criteria. The process was repeated twice in the span of six months; indicates high replicability of the article search and selection process. This process yielded a total of 41 articles, which were read in detail to conduct a content analysis. The entire literature review procedure is depicted in .

2.2. Sample characteristics

As can be seen in , our final dataset included 41 articles covering the period from 2001 to 2020. We noted an increase in the number of published research over the last 20 years. In fact, more than half (66% or 27 articles) of all the reviewed research papers were published in the last five years. In the last 20 years, the most articles on this topic were published in Research Policy (10), followed by the Journal of Business Venturing (7) and Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice (5). Nearly half (42% or 17 articles) of the studies were published in four entrepreneurship journals (ETP, JBV, SEJ, VC), while the rest were published in six management (AMJ, RP, JMS, MS, OS, SMJ) and three finance journals (JF, JFE, RFS). The most influential study was published in Research Policy in 2007 (Hsu Citation2007) and was cited 266 times (WoS Core count), followed by Hallen and Eisenhardt (Citation2012), Busenitz, Fiet, and Moesel (Citation2005), Elitzur and Gavious (Citation2003), Fischer and Reuber (Citation2007), and Meuleman and De Maeseneire (Citation2012), all of which were cited more than 100 times (WoS Core count). In terms of methodology, 29 of the articles were quantitative studies, 4 were qualitative, 4 were mixed methods studies, and 4 were conceptual papers. The details of the 37 empirical articles are presented in . provides brief content analysis of the 41 articles that were selected for the review.

Table 2. Journals by year and number of articles on signaling to early-stage equity investors

Table 3. Overview of research by the main elements of signaling theory

Table 4. Article by article content analysis

3. Results

3.1. Signal senders

Signal senders are insiders with access to information that is unavailable to outsiders (Taj Citation2016; Connelly et al. Citation2011). In the entrepreneurship financing literature, signal senders are considered to be the new venture, the (lead) entrepreneur, or the entrepreneurial team. These insiders possess superior knowledge about their intentions, their abilities and the quality of the venture that is of interest to outsiders, usually investors or other external stakeholders.

3.1.1. Signal sender type

The majority of the empirical research examining signaling to early-stage equity investors has treated the firm as a signal sender. Many prospective early-stage equity investors require some form of business summary as a first step in deciding whether or not an opportunity should advance to the next investment phase (Mason and Stark Citation2004). This information about a new venture is used to assess the venture’s overall growth potential and potential for high returns through exit (Wallmeroth, Wirtz, and Groh Citation2018; Carpentier and Suret Citation2015) and its legitimacy (Plummer, Allison, and Connelly Citation2016; Becker-Blease and Sohl Citation2015) prior to conducting more thorough due diligence (Brush, Edelman, and Manolova Citation2012; Doblinger, Surana, and Anadon Citation2019; Hoenig and Henkel Citation2015). It is common for studies that treat venture as a signal sender to study objective signals such as affiliations, patents and prior equity and debt financing (Maxwell, Jeffrey, and Lévesque Citation2011). Approximately one third of the studies on signaling to early-stage equity investors have treated founders as signal senders. It is worth noting that despite the recognition that most new ventures with high growth potential are the result of teamwork (Harper Citation2008; Cooney Citation2005), research has almost exclusively studied signaling effects of a lead entrepreneur or treated management team characteristics as a firm’s stock of human capital (Hsu and Ziedonis Citation2013; Hoenig and Henkel Citation2015). In the early stages founder characteristics are often considered to be a proxy of venture quality (Kaplan, Sensoy, and Strömberg Citation2009). In particular, the founder’s human capital, social capital and track record are considered to speak of the founder’s capabilities to pursue the opportunity. Studies that treated founders as signal senders are also more likely to study signals that are more subjective in nature such as the founder’s perceived entrepreneurial passion, coachability or trustworthiness (Maxwell and Lévesque Citation2014; Ciuchta et al. Citation2018; Warnick et al. Citation2018). Research that studies new venture signaling differs from research that studies the founder’s signaling in two important aspects. First, in the early phases of the investment decision-making process, investors rely more heavily on objective, easily observable and comparable signals, giving more weight to new venture characteristics and founding team education and experience compared to the later stages, where subjective signals such as entrepreneurial passion and trustworthiness become more salient (Brush, Edelman, and Manolova Citation2012; Mitteness, Baucus, and Sudek Citation2012). Second, the financing stage is likely to coincide with available information about a venture (Plummer, Allison, and Connelly Citation2016; Huang and Pearce Citation2015). Hence, research that focuses on seed stage investing is more likely to study entrepreneurs as signals senders compared to the research interested in financing of expansion-ready startups.

3.1.2. Signal sender characteristics

Signaler characteristics are relevant to the signaling process, because they influence signaling outcomes (Vasudeva, Nachum, and Say Citation2018). While signal senders can select and modify the signals they send, this does not apply to indices. These unalterable characteristics of a signaler may influence the signal receiver’s expectations and result in different outcomes for signalers that send the same signals (Spence Citation1973) as a result of differences in the signaler’s perceived credibility (Vasudeva, Nachum, and Say Citation2018; Gomulya and Mishina Citation2017). Recently, researchers have begun exploring how the gender of a founder influences signaling outcomes. Guzman and Kacperczyk (Citation2019) explained that female founders are 63% less likely to obtain VC funding, of which 65% can be attributed to the observation that female entrepreneurs are less likely to signal growth potential to external investors and 35% can be attributed to investors’ preference for male-founded ventures. Research considering how signal strength depends on the signaler’s gender has shown that investors assign different values to the founder’s human capital based on the gender of the founder (Alsos and Ljunggren Citation2017). More specifically, signals that are congruent with the signaler’s gender are more effective. Signaling prior equity investment is more effective for male founders, whereas signaling prior philanthropic investment is more effective for female founders when trying to acquire additional funding (Yang, Kher, and Newbert Citation2020). A slim but potentially fruitful stream of research has also considered the role of the founder’s social status (Claes and Vissa Citation2020). Exploration of indices are in no way exclusive to founders as signalers. New venture characteristics such as size, age and industry may alter how signals are received (Edelman et al. Citation2021).

3.2. Signals

Signals are bits of private information sent to outsiders (Taj Citation2016; Connelly et al. Citation2011). Usually (but not exclusively), signalers communicate the information intentionally in an effort to influence receivers’ decisions in their favor (Connelly et al. Citation2011). Signals differ in many characteristics, as summarized in .

Table 5. Signal characteristics

Research on signaling in the context of early-stage financing has studied a much broader range of signals compared to the economics and finance literature. While traditional signaling theory assumes that signals are credible because they are costly and therefore difficult to imitate by inferior prospects (Spence Citation1973), entrepreneurship researchers understand signals to be any information that reflects the signaler’s underlying characteristics (Clough et al. Citation2019). In the entrepreneurship financing literature, entrepreneurs can signal their quality and intentions using two main types of signals (Huang and Knight Citation2017):

Informational signals that provide insight into the quality of the entrepreneur or venture, and

Interpersonal signals that provide insight into how the entrepreneur or venture might interact with others and available non-financial resources.

While traditional signals such as credentials, affiliations, prior investments, and different certifications have been studied in this context, research has also investigated how entrepreneurs signal their underlying qualities through self-presentation. It has been argued that such rhetorical signals are effective because the environment in which early-stage entrepreneurs signal is noisy and such signals help to reinforce traditional signals (Steigenberger and Wilhelm Citation2018; Plummer, Allison, and Connelly Citation2016). provides example of pairs of objective and subjective informational and interpersonal signals.

Table 6. Typology of signals about an entrepreneur with examples

However, signals are rarely perfectly aligned with particular unobservable qualities (Connelly et al. Citation2011), and many signals can have both informational and interpersonal implications. For example, entrepreneurs who display high levels of entrepreneurial passion may be perceived as both persistent (informational signal) and uncooperative (interpersonal signal) (Warnick et al. Citation2018). Entrepreneurship researchers have increasingly recognized that many signals are ambiguous (Ciuchta et al. Citation2018). Because signals lend themselves to multiple interpretations, combinations of signals and context cues shape the signal receivers’ interpretation (Schepker, Oh, and Patel Citation2018).

3.2.1. Venture-level signals

3.2.1.1. Public funding

Several studies (Stevenson, Kier, and Taylor Citation2020; Islam, Fremeth, and Marcus Citation2018; Hulsink and Scholten Citation2017; Söderblom et al. Citation2015) have shown that new ventures that obtain government subsidies have better chances of raising future equity investments, possibly due to the decreased liability of newness (Söderblom et al. Citation2015) and increased perception of venture quality (Meuleman and De Maeseneire Citation2012; Feldman and Kelley Citation2006). Accordingly, prestigious grants may be especially beneficial to new ventures that have no or few patents (Islam, Fremeth, and Marcus Citation2018). Islam, Fremeth, and Marcus (Citation2018) found that signal timing is important because the signal is effective only in the first six months post grant reception. Even though companies that have recently received government subsidies have better chances of obtaining additional external equity funding, research (Stevenson, Kier, and Taylor Citation2020) has shown that those firms grow less than similar firms that do not obtain such grants.

3.2.1.2. Private funding

An entrepreneur’s personal investment in the new venture is considered to be a signal of the venture’s value and the entrepreneur’s commitment to the venture (Prasad, Bruton, and Vozikis Citation2000; Busenitz, Fiet, and Moesel Citation2005). Although entrepreneurs can rely on bootstrapping to finance their ventures (Grichnik et al. Citation2014), those who incur personal and/or business debt signal commitment and lower downside risk. This results in better chances of obtaining external equity funding (Epure and Guasch Citation2020). That being said, Busenitz, Fiet, and Moesel (Citation2005) failed to find evidence that new venture team investment and retained equity predict venture outcomes. In addition to the funder’s own investment in the new venture, research has looked into the signaling effect of prior investor backing. Follow-on investors are susceptible to information about earlier investors, especially if these were high-profile investors (Bernstein, Korteweg, and Laws Citation2017; Ko and McKelvie Citation2018; Drover, Wood, and Zacharakis Citation2017; Capizzi, Croce, and Tenca Citation2022) or investors with a central position within an investment group (Butticè, Croce, and Ughetto Citation2021). Relatively inexperienced investors rely more on information about prior funding of the venture (Bernstein, Korteweg, and Laws Citation2017). It has been argued that prior investments certify venture quality in the minds of investors (Drover, Wood, and Zacharakis Citation2017; Croce, Tenca, and Ughetto Citation2017). While prior equity investments by AIs or VCs signal a venture’s financial viability, successful crowdfunding campaigns signal market viability (Drover, Wood, and Zacharakis Citation2017; Roma, Petruzzelli, and Perrone Citation2017), providing complementary signals of a venture’s quality (Roma, Vasi, and Kolympiris Citation2021). Moreover, signaling a new venture’s attractiveness to multiple equity investors can facilitate investors’ commitment (Hallen and Eisenhardt Citation2012). On the other hand, withdrawal of early investors can hurt a new venture through the decreased likelihood of obtaining follow-on equity funding and the negative impact on its valuation (Shafi, Mohammadi, and Johan Citation2020).

3.2.1.3. Affiliations and alliances

Much research has focused on the role of public financing of new ventures, but few studies have examined how interactions between ventures and governments, research organizations, non-profit organizations, and venture development organizations help new ventures to raise future equity financing. These organizations provide a variety of non-financial resources to support innovation and commercialization (Doblinger, Surana, and Anadon Citation2019). Researchers have argued that such alliances serve as signals of quality and connectedness to early-stage equity investors (Stuart Citation2000; Doblinger, Surana, and Anadon Citation2019). Hoenig and Henkel (Citation2015) reported that VCs place a higher value on research alliances than on patents, even though patents are costly objective informational signals. This suggests that the value of alliances is greater than just indicating technological quality. For example, Plummer, Allison, and Connelly (Citation2016) demonstrated that affiliations with venture development organizations increase the effectiveness of other signals, such as product development stage and patents. Affiliations increase the perceived legitimacy of new ventures (Plummer, Allison, and Connelly Citation2016), especially when the new venture does not have a strong reputation, but is affiliated with an organization that does (Colombo, Meoli, and Vismara Citation2019). This is because new ventures must pass these organizations’ screening processes to gain access to their partners. Moreover, new ventures gain continued access to the resources needed to survive and compete in the business environment.

3.2.1.4. Patents and prototypes

Several studies have examined the relevance of patents and prototypes for accessing external equity financing. Audretsch, Bönte, and Mahagaonkar (Citation2012) claimed that patents signal the ability to appropriate the returns of the innovation and prototypes signal the feasibility of the project. Hsu and Ziedonis (Citation2013) suggested that patents could signal both technological quality and commercial orientation. The findings of research investigating the value of patents to early-stage equity investors have been inconclusive. Engel and Keilbach (Citation2007) found that patent applications increase the likelihood of VC funding. Furthermore, patents are more important for the less experienced founders in the early round of financing (Hsu and Ziedonis Citation2013). By contrast, Audretsch, Bönte, and Mahagaonkar (Citation2012) found that patents are only effective when combined with prototypes. Early-stage new ventures that signal their quality through prototypes and patents simultaneously have a higher probability of obtaining AI or VC funding (Audretsch, Bönte, and Mahagaonkar Citation2012). Since the track record of new ventures is very limited, their progress can serve as a proxy for the quality of the new venture (Hallen and Eisenhardt Citation2012). Plummer, Allison, and Connelly (Citation2016) found that ventures with a market-ready product are more likely to receive equity financing than ventures without market-ready products – an effect that is more pronounced if the venture is affiliated with a venture development organization.

3.2.2 Founder-level and team-level signals

3.2.2.1. Education and experience

A founder’s human capital in the form of education and experience has been by far the most well-studied founder-level and team-level signal in the early-stage equity financing literature. These signals usually fall into the category of costly objective informational signals; however, investors’ perceptions of the founder’s market knowledge and entrepreneurial ability could serve as similar costless and subjective signals. It has been argued that when venture performance data are not yet available, the founder’s human capital is a signal of venture viability (Ko and McKelvie Citation2018). While a venture’s track record is often unavailable in the early stage of new ventures, the founder’s track record may be. Entrepreneurs with a track record of success and background of accomplishments are more likely to receive early-stage investment (Ebbers and Wijnberg Citation2012; Hallen and Eisenhardt Citation2012). In their field experiment, Bernstein, Korteweg, and Laws (Citation2017) observed that experienced AIs make investment decisions solely based on the founding team’s education and experience, whereas inexperienced investors rely more on the new venture’s traction data. The founding team’s human capital is related to the ability to raise early-stage funding (Huynh Citation2016), but this effect is more pronounced in the first round of financing. Ko and McKelvie (Citation2018) found that the founder’s education, industry, and entrepreneurial experience have significant effects on first-round financing. The effect of experience diminishes in subsequent rounds of financing, while the effect of education persists. The importance of a founder’s education on fundraising has also been shown, even though the founder’s experience has an impact on the firm’s survival whereas academic status does not (Gimmon and Levie Citation2010). Analyzing venture outcome data over the span of 10 years led Busenitz, Fiet, and Moesel (Citation2005) to conclude that signals sent to investors in the early-stage venture financing process have no relationship with actual venture outcomes.

3.2.2.2. Personal relationships and networks

A firm’s social capital in the form of the venture’s affiliations with different organizations has been well studied, but so has the founder’s relational social capital, which is generated through interpersonal relationships (Still, Huhtamäki, and Russell Citation2013). Relational social capital provides access to necessary resources, including human capital (Hsu Citation2007), thereby increasing the venture’s viability (Newbert and Tornikoski Citation2013). In his study, Huynh (Citation2016) found that the founding team’s social capital (measured as relationships between the team and its advisors) only indirectly influences the probability of obtaining early-stage equity financing through its impact on the founding team’s capabilities. This supports the assumed relationship between social and human capital, but undermines the signaling value of social capital to early-stage equity investors. That being said, a founder’s direct ties with investors increase the likelihood of venture funding and positively impact venture valuation (Hsu Citation2007; Zhang Citation2011), as does previously receiving investment from a prominent investor (Ko and McKelvie Citation2018; Butticè, Croce, and Ughetto Citation2021), especially in the case of inexperienced follow-on investors (Bernstein, Korteweg, and Laws Citation2017). Endorsements signal new venture legitimacy (Plummer, Allison, and Connelly Citation2016; Fisher et al. Citation2017), thereby increasing the odds of receiving further funding.

3.2.2.3. Displayed personal traits

Personality traits such as perseverance, commitment, entrepreneurial passion, trustworthiness, likability, and coachability appear repeatedly on the investment criteria lists of AIs and VCs (Van Osnabrugge Citation1998; Sudek Citation2006; MacMillan, Siegel, and Narasimha Citation1985). Personality traits can be signaled through accomplishments, verbal or non-verbal language, and affiliations. Researchers have suggested that displayed entrepreneurial passion signals that the entrepreneur will persevere in the face of challenges (Warnick et al. Citation2018). Perceived entrepreneurial passion increases the entrepreneur’s likelihood of obtaining early-stage equity funding (Mitteness, Sudek, and Cardon Citation2012), especially when combined with coachability (Warnick et al. Citation2018). Coachability signals the potential for collaborative relationships with the investor (Ciuchta et al. Citation2018). In research conducted by Ciuchta et al. (Citation2018), coachability emerged as one of the predictors of investors’ willingness to invest, along with perceived entrepreneur competence and preparedness. The effect was more pronounced in those investors who had experience with active mentoring. One study (Maxwell and Lévesque Citation2014) also considered the signaling value of trust-building behaviors to AIs. Trust-violating behaviors, especially those related to incompetence, rigidity, and inaccuracies in pitches were found to be more predictive of investment decisions than trust-building behaviors.

3.3. Signal receivers

Signal receivers are the outsiders who require insider information to guide their decisions. Signals are only effective when receivers look for them (Connelly et al. Citation2011). Signal receivers benefit from signals that accurately reflect the signaler’s underlying characteristics. However, because the interests of signalers and receivers often diverge, signalers have an incentive to misrepresent themselves to their advantage (Crawford and Sobel Citation1982). Therefore, signal receivers need to judge “signal honesty” (Durcikova and Gray Citation2009). In entrepreneurship financing, the signal receivers are usually existing or potential investors. In the early-stage signaling literature, these were usually considered to be VCs, but, from 2012, research on signaling to AIs specifically began to appear as well. Several studies we analyzed did not specifically define the investor type, but rather treated various investors as a homogeneous group of external equity investors (e.g., Gimmon and Levie Citation2010; Söderblom et al. Citation2015).

3.3.1. Differences between investors

Only one study in our sample directly compared the effectiveness of signals based on the target investor type (Hsu et al. Citation2014) and one study controlled for the investor type (Warnick et al. Citation2018). Hsu et al. (Citation2014) provided preliminary evidence that AIs and VCs have slightly different investment policies. While these investor groups do not differ in terms of the value they assign to the founder’s entrepreneurial experience, VCs assign more value to the economic potential of the firm, whereas AIs assign more value to entrepreneur’s commitment and social network (Hsu et al. Citation2014). These findings are in line with Fiet (Citation1995) argument that VCs view market risk as more important than agency risk, while the opposite holds true for AIs. Other studies that included mixed samples of AIs and VCs (Stevenson, Kier, and Taylor Citation2020; Ko and McKelvie Citation2018; Plummer, Allison, and Connelly Citation2016; Audretsch, Bönte, and Mahagaonkar Citation2012) did not differentiate between the capital obtained from the two groups.

3.3.2. Differences within investors

Prominent AIs and VCs who are more embedded in investment networks are more sensitive to signals of a founder’s human capital (education and experience) than less prominent investors (Ko and McKelvie Citation2018). Similarly, Bernstein, Korteweg, and Laws (Citation2017) reported that experienced AIs make investment decisions based only on information about the founding team’s education and experience, while inexperienced investors follow traction and investment data to help guide their investment decisions. More experienced AIs also place greater emphasis on an entrepreneur’s personal traits, such as passion and coachability, than less experienced investors (Warnick et al. Citation2018). However, not all research has identified differences within investor groups. For example, Hoenig and Henkel (Citation2015) found no differences in the use of quality signals in the form of patents, research alliances, and founding team experience based on VCs’ experience or educational background. These results, though limited, suggest that investors of the same type differ more in terms of their preference regarding founder than venture characteristics. That being said, more experienced and specialized early-stage investors have been found to make better investment decisions due to better screening (Gompers, Kovner, and Lerner Citation2009; Wiltbank et al. Citation2009), a finding consistent with the predictions of signaling theory (Spence Citation1973). More recently, researchers have also turned to examining interpersonal differences within groups of investors. Several studies (Mitteness, Sudek, and Cardon Citation2012; Ciuchta et al. Citation2018) have found that AIs place different value on entrepreneur-level signals depending on their willingness to mentor and interpersonal differences. Investors with coaching experience place greater emphasis on an entrepreneur’s coachability (Ciuchta et al. Citation2018), while more open AIs who are willing to mentor put more weight on entrepreneurial passion (Mitteness, Sudek, and Cardon Citation2012).

4. Future research directions

Our review of the 20 years of research using signaling theory to understand the investment decisions of angel investors and venture capitalists shows where the knowledge is abundant and sparse, and points to avenues for impactful research in the future. In particular, in our suggestions, organized around key elements of signaling theory, we consider emerging themes in the literature on signaling to early-stage equity investors, missed opportunities in the application of signaling theory to this particular research area, and trends in the related management literature that could inspire novel investigations in this particular research area.

4.1. Signal senders

4.1.1. Indices

Research on early-stage equity investing has examined only the moderating role of gender in access to early-stage equity funding (Guzman and Kacperczyk Citation2019; Alsos and Ljunggren Citation2017). The role of other founder-level indices (observable unalterable characteristics) such as age and race has remained unexplored. Exploring the effects of these indices is necessary to uncover investor biases and inequalities in access to external equity investment. Understanding how signals and indices interact is important for developing effective signaling strategies to overcome such biases. In addition to studying the moderating effects of founder-level indices, research could also explore investor-level indices (Ewens and Townsend Citation2020) and firm-level indices such as a firm’s industry group, age, and size (Downes and Heinkel Citation1982).

4.1.2. Investor signaling

Shifting the research lens toward signal receivers (investors) and away from signal senders (entrepreneurs) may make important contributions to signaling theory in entrepreneurship financing. Researchers could even consider how investors signal their quality and intent to the entrepreneurs presenting investment opportunities. Early-stage financing markets are not perfect (Wright and Mike Citation1998). Most early-stage financing markets are thin, and most high growth potential new ventures do not seek VC funding, which significantly impacts the quality of the venture pool VCs can choose from (Bertoni, D’Adda, and Grilli Citation2016). Moreover, the concerns have been raised that public sources of venture capital may crowd out private VCs (Cumming and MacIntosh Citation2006; Leleux and Surlemont Citation2003). Investors differ in the financial and non-financial capital they can provide to the investee, including reputational benefits, which can significantly influence a new venture’s prospects (Ko and McKelvie Citation2018; Pollock et al. Citation2010). Although research has considered how private equity firms, including VC funds, signal to their prospective investors (Vanacker et al. Citation2020; Balboa and Martí Citation2007), research has not yet explored how investors can signal to attract high-quality new ventures.

4.2. Signals

4.2.1. Signal interactions

Although researchers have begun to examine interaction effects between different signals, this research primarily seeks to uncover complementary signals (Plummer, Allison, and Connelly Citation2016; Warnick et al. Citation2018; Cardon, Mitteness, and Sudek Citation2017). Plummer, Allison, and Connelly (Citation2016), for example, proposed that objective signals of new venture legitimacy increase the signaling impact of other signals that may otherwise go unnoticed. Related research (Ozmel, Reuer, and Gulati Citation2013) suggests that similar signals of venture quality (e.g., affiliation with prominent VCs and the venture’s prominent position in alliance networks), when combined, attenuate each other’s effectiveness and thus may not represent an efficient signaling strategy (considering their cost). Steigenberger and Wilhelm (Citation2018) theorized that in a high-noise signaling environment, subjective, costless signals complement objective, costly signals. Only one study in our sample (Nagy et al. Citation2012) tested the interaction effect of costly objective and costless subjective signals of founder quality, but found no support for the proposition. On the contrary, it found that entrepreneurs who lacked credentials but engaged in impression management (exemplification, ingratiation, and self-promotion) had the same likelihood of receiving venture capital as entrepreneurs with credentials who did not engage in such activities, suggesting a compensatory effect. In addition, the latest research (Edelman et al. Citation2021) suggests that different signal configurations can lead to the same outcome. The premise of this research is that early-stage equity investors consider signals in tandem rather than in isolation. To understand how different signals work together, we suggest that researchers examine the complementary, compensatory and substitutive effects of signals that differ in type (e.g., objective and subjective) and content (e.g., interpersonal and informational), as the interaction effects of signals appear to depend on their particularities (Steigenberger and Wilhelm Citation2018).

4.2.2. Interpersonal signals

Entrepreneurs use information and interpersonal signals to convey information about quality and intent to investors (Huang and Knight Citation2017). Informational signals provide information about the return investors can expect on financial resources, while interpersonal signals communicate information about the potential return on non-financial resources as well (Ciuchta et al. Citation2018). VCs and AIs seek to add value through their active involvement in addition to injecting financial capital (Van Osnabrugge and Robinson Citation2000; Sudek Citation2006). Baron and Markman (Citation2000) explained that interpersonal skills are important for building social capital and therefore gaining access to needed resources. Since early-stage equity investors form long-term relationships with entrepreneurs once they have invested, investors pay attention to the entrepreneur’s ability to work with others. They are prepared to reject competent entrepreneurs if they are unable to build rapport (Huang and Pearce Citation2015; Huang Citation2018; Mason, Botelho, and Zygmunt Citation2017). So far, researchers have explored mainly how entrepreneurs signal quality using informational signals, but, with a few exceptions (Ciuchta et al. Citation2018; Warnick et al. Citation2018), they have overlooked the value of interpersonal signals in investor decision-making.

4.2.3. Negative signals

The literature on investor decision-making suggests that investors rely on an elimination-by-aspects heuristic in the screening phase rather than engaging in fully compensatory decision-making, which would involve weighing all relevant investment criteria (Maxwell, Jeffrey, and Lévesque Citation2011). Maxwell and Lévesque (Citation2014) showed that negative (trust-damaging behaviors) signals predict investment decisions better than positive (trust-building behaviors) signals. Moreover, as many signals are ambiguous, contextual cues determine whether a certain signal is interpreted negatively or positively (Schepker, Oh, and Patel Citation2018). This suggests that signalers should attempt to control the receivers’ interpretation by purposefully combining signals that reinforce positive interpretations. Research in the field of early-stage equity financing has only scratched the surface when it comes to understanding negative signals. Questions related to the variety and ambiguity of negative signals, their effects, and approaches to mitigate negative impact on the ability to secure equity financing appear to be fruitful research directions.

4.2.4. Signal inconsistency

It has been argued that in complex environments, some degree of signal incongruence in terms of valence (positive and negative) is to be expected (Drover, Wood, and Corbett Citation2018). None of the studies in our sample tested the effects of signal incongruence on financing outcomes. However, related research in this area (Vergne, Wernicke, and Brenner Citation2018; Zhang, Zhang, and Yang Citation2022) has found that signal incongruence leads to more negative attitudes toward signal senders. These negative reactions occur not only when the signals are related to the same content dimension (e.g., a venture’s integrity), but also when incongruent signals are related to different content dimensions (e.g., a venture’s integrity and capability) (Paruchuri, Han, and Prakash Citation2021), which can be perceived as potentially reinforcing each other’s negative effects. Conflicting signals about the venture or its founder may sabotage early-stage equity financing efforts, as inconsistency can undermine investors’ trust (Fischer and Reuber Citation2007; Shepherd and Zacharakis Citation2001). However, the implications in the context of early-stage equity financing remain unexplored.

4.2.5. Signal honesty

In contexts where signals are inexpensive to manipulate and difficult to verify, it is particularly important for signal receivers to be able to distinguish dishonest (inaccurate) signals from honest (accurate) ones (Momtaz Citation2021). A staggering number of entrepreneurs send dishonest signals in the preinvestment phase to attract investors (Cottle and Anderson Citation2020). This raises the risk of adverse selection for early-stage equity investors, who have been shown to rely on information provided by entrepreneurs in making investment decisions (Clark Citation2008; Adomdza, Åstebro, and Yong Citation2016). That being said, according to signaling theory (Spence Citation1973, Citation2002), as signal receivers accumulate more information over time, they are able to recognize dishonest signals. Although dishonest signaling may increase a new venture’s ability to obtain early-stage funding (Rutherford, Buller, and Stebbins Citation2009; Cottle and Anderson Citation2020), the costs of such behavior for entrepreneurs (when detected) have yet to be adequately explored. Related research (Gomulya et al. Citation2019) suggests that such behavior can harm the signaler’s reputation and future prospects if signal receivers learn that the signals were inaccurate. Therefore, we encourage future early-stage financing research to examine the consequences of dishonest signaling and explore factors that enhance or mitigate damage to the signaler.

4.3. Signal receivers

4.3.1. Investor type

Surprisingly few studies have directly compared the effectiveness of signals based on the type of target investor, although there is preliminary evidence that AIs and VCs have different investment policies (Hsu et al. Citation2014). There are many reasons to suspect that different groups of early-stage equity investors pay attention to different signals. First and foremost, the two types of investors differ in the sources of funding provided. AIs are private persons (usually experienced entrepreneurs) who invest their own money in new ventures to which they have no family connection. By contrast, VCs are professional investors who invest in new ventures on behalf of the limited partners. While both types of investors invest primarily for financial reasons (Croce, Ughetto, and Cowling Citation2020), many AIs invest for reasons beyond financial returns (Harrison, Botelho, and Mason Citation2016; Morrissette Citation2007). Due to higher resource constraints (Ibrahim Citation2008), AIs are more likely to invest in the earlier stages compared to VCs. VCs as well as angel groups have more sophisticated and formalized investment decision-making processes compared to individual AIs (Mason, Botelho, and Harrison Citation2019; Cumming and Zhang Citation2019). The two types of investors also differ in their style of governance, with AIs placing greater emphasis on the entrepreneur–investor relationship as a form of oversight and VCs relying more on contractual governance (Bessière, Stéphany, and Wirtz Citation2020). These differences between investors may result in different investment policies. Future research could investigate the systematic differences between various types of early-stage equity investors in terms of their susceptibility and attention to different signals of quality and intent.

4.3.2. Matching

Hallen and Eisenhardt (Citation2012) observed that even when ventures successfully signal their quality, they have troubles getting investors to commit to the venture. Many early-stage investors play an active role in the new ventures (Politis Citation2008; Large and Muegge Citation2008) in order to maximize their financial and non-financial returns. Conflicts that may arise between entrepreneurs and early-stage investors can be detrimental for the venture (Collewaert Citation2012). Therefore, it makes sense for early-stage equity investors to consider compatibility with the entrepreneur who is presenting the investment opportunity. Research considering how entrepreneurs and investors match has shown that VCs prefer entrepreneurs with similar decision-making styles (Murnieks et al. Citation2011). Furthermore, VCs prefer entrepreneurs with similar educational and professional backgrounds (Franke et al. Citation2006; Ebbers and Wijnberg Citation2012). AIs with entrepreneurial experience place greater emphasis on entrepreneurial passion than other investors (Warnick et al. Citation2018). These findings suggest a similarity bias in equity investing. On the other hand, AIs and VCs seek to contribute the non-financial resources at their disposal, such as mentoring and advising (Huang and Knight Citation2017), suggesting that many investors seek to complement the entrepreneurs’ skillset in addition to creating a good rapport. The entrepreneurial financing literature could lean on signaling theory to identify signals that facilitate match-making between entrepreneurs and investors.

4.4 Signaling context

4.4.1. Signaling context

Different investment stages are characterized by different goals (De Clercq et al. Citation2006), which makes it very likely that investors pay attention to different signals at different points in the investment cycle. Research has found referrals by VCs or AIs to be especially effective in the pre-screening phase (Croce, Tenca, and Ughetto Citation2017; Drover, Wood, and Zacharakis Citation2017), while founder and venture characteristics play a greater role in the screening and evaluation phase of investment decision-making (Mitteness, Baucus, and Sudek Citation2012; Croce, Tenca, and Ughetto Citation2017). Hallen and Eisenhardt (Citation2012) suggested that the sequencing of different signals is important to increase the chance of obtaining equity funding. While corroborating previous findings that signal effectiveness changes throughout the investment process, Edelman et al. (Citation2021) found that the most effective sequences of signal configurations differ by sector. Investors are more willing to invest in more stable and less concentrated industries (Lester et al. Citation2006), suggesting that ventures in different industries are judged against different standards. Similarly, market conditions, such as high versus low market growth, influence which signals carry more weight in investor decisions and which carry less (Gulati and Higgins Citation2003). Therefore, the question should be not only what to signal, but also where and when to send specific signals to increase the chances of obtaining early-stage financing.

5. Conclusion

Signaling theory provides a useful framework for understanding why certain entrepreneurs are successful in obtaining early-stage equity investments, whereas others are not. While the number of studies using signaling theory to explain success in obtaining early-stage equity financing is increasing, signaling theory remains underutilized despite its suitability for this particular research question. This is evidenced by the relatively small number of studies making explicit reference to signaling theory. We summarize the main strengths and weaknesses of the current state of the literature below.

In this literature review, we have shown that researchers employing signaling theory in the context of early-stage equity investing have focused mostly on identifying the empirical magnitude of signaling effects. They have explored the effects of various venture and founder-level signals, particularly the signaling role of endorsement relationships and affiliations, prior equity and debt financing, founder’s human capital, and patents. Research remains inconclusive regarding the signaling effectiveness of patents, suggesting a possible moderating effect of the signaling environment and/or the characteristics of signalers and signal receivers. Signaling theory has been applied to explain the investment decisions of both AIs and VCs, and research has uncovered the role of investors’ professional background in investment decisions. New research has also started to deal with the moderating role of indices (Alsos and Ljunggren Citation2017; Yang, Kher, and Newbert Citation2020), providing some insight into discrimination in early-stage equity investing. Moreover, over the years, the scope of signaling research has broadened from objective signals (e.g., credentials and technology) to include signals that are subjective in nature and can be conveyed through verbal and non-verbal strategies (Anglin et al. Citation2018). This expansion of scope has provided valuable insights and challenged the assumption that the effectiveness of signals depends on their cost (Nagy et al. Citation2012).

Importantly, new developments in the literature recognize that signals sent to early-stage equity investors are often ambiguous and unreliable (Plummer, Allison, and Connelly Citation2016), making it difficult to discern between high-quality and low-quality new ventures. Moreover, the stream of literature on investor decision-making recognizes that investors are not rational agents, relying on fully compensatory decision models (Maxwell and Lévesque Citation2014). Moreover, investors are always exposed to bundles of signals about new ventures, and tend to make holistic estimations of new venture funding potential rather than considering signals one by one (Huang Citation2018). Cognitive theories can help researchers circumvent the key limitations of signaling theory, which sees signal receivers and signal senders as rational agents (Bergh et al. Citation2014) and signals as information that is transmitted and received in an uniform manner (Vanacker and Forbes Citation2016). Insight into cognitive mechanisms such as how and why signal receivers pay attention to some signals and not others, how they interpret signals and use them in their decision-making is particularly important in research dealing with subjective signals, where signaling behaviors (e.g., the entrepreneur agreeing with the investor) and signal interpretation (e.g., the investor’s perception of the entrepreneur’s coachability) need to be identified to make a meaningful contribution to signaling theory. Cognitive theories may also help detangle how investors deal with sets of signals, that may include different signal combinations or incongruent signals (Drover, Wood, and Corbett Citation2018) and how investors assess the trustworthiness and suspiciousness of different signals given that the interests of entrepreneurs and early-stage equity investors do not always align (Harrison and Mason Citation2017). Cognitive perspectives can also be used to investigate between-investor differences, which result from differences in recognition and interpretation of signals.

Much of the existing literature on signaling to early-stage equity investors does not bring to the fore the environment (context) in which signaling occurs. Environmental factors may include industry, investment phase, investor syndication, investment platforms, investor density (i.e., availability of investors in the market), and geographic region. The second major shortcoming of the literature reviewed is that research has not yet examined founding team signaling by taking into consideration team composition, although entrepreneurial teams have been acknowledged as one of the most important considerations for venture investors (Higashide and Birley Citation2002).

This brings us to the limitations of this study. First, our literature review included only studies published in the leading entrepreneurship, management, and finance journals, which may have biased our research findings (Kunisch et al. Citation2018). However, this approach enabled us to conduct a more thorough review with a potentially greater contribution to the advancement of the field (Post et al. Citation2020). Although we paid particular attention to the replicability of our search and selection process (Aguinis and Solarino Citation2019), subjectivity cannot be completely eliminated. We acknowledge that the categories we identified for each element of signaling theory may change in future investigations of the state of knowledge. Importantly, our findings are not generalizable to other forms of equity financing such as crowdfunding, government subsidies, or later stage private equity investments, as signaling is strongly influenced by the type of investor and the stage of the venture (Colombo Citation2021; Ko and McKelvie Citation2018).

With this review paper, we have sought to integrate the existing research and motivate future research to fill the gaps and expand the knowledge of early-stage venture financing. The literature on investor decision-making would benefit from leaning on signaling theory to advance the understanding of entrepreneurial financing. We are confident that our review can help to guide further research explorations in the field of early-stage equity investing by bringing greater clarity to the field.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Adomdza, G. K., T. Åstebro, and K. Yong. 2016. “Decision Biases and Entrepreneurial Finance.” Small Business Economics 47 (4): 819–834. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9739-4.

- Aguinis, H., and A. M. Solarino. 2019. “Transparency and Replicability in Qualitative Research: The Case of Interviews with Elite Informants.” Strategic Management Journal 40 (8): 1291–1315.

- Akerlof, G. A. 1970. “The Market for “Lemons”: Quality, Uncertainty, and the Market Mechanism.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84 (3): 488–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1879431.

- Alsos, G. A., and E. Ljunggren. 2017. “The Role of Gender in Entrepreneur–investor Relationships: A Signaling Theory Approach.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41 (4): 567–590.

- Amornsiripanitch, N., P. A. Gompers, and Y. Xuan. 2019. “More than Money: Venture Capitalists on Boards.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 35 (3): 513–543. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewz010.

- Anglin, A. H., J. C. Short, W. Drover, R. M. Stevenson, A. F. McKenny, and T. H. Allison. 2018. “The Power of Positivity? the Influence of Positive Psychological Capital Language on Crowdfunding Performance.” Journal of Business Venturing 33 (4): 470–492. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.03.003.

- Audretsch, D. B., W. Bönte, and P. Mahagaonkar. 2012. “Financial Signaling by Innovative Nascent Ventures: The Relevance of Patents and Prototypes.” Research Policy 41 (8): 1407–1421. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.003.

- Balboa, M., and J. Martí. 2007. “Factors that Determine the Reputation of Private Equity Managers in Developing Markets.” Journal of Business Venturing 22 (4): 453–480. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.05.004.

- Baron, R. A., and G. D. Markman. 2000. “Beyond Social Capital: How Social Skills Can Enhance Entrepreneurs’ Success.” Academy of Management Perspectives 14 (1): 106–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2000.2909843.

- Baty, G., and B. Sommer. 2002. “True Then, True Now: A 40-year Perspective on the Early Stage Investment Market.” Venture Capital 4 (4): 289–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369106022000024914.

- Becker-Blease, J. R., and J. E. Sohl. 2015. “New Venture Legitimacy: The Conditions for Angel Investors.” Small Business Economics 45 (4): 735–749. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9668-7.

- Belenzon, S., A. K. Chatterji, and B. Daley. 2020. “Choosing between Growth and Glory.” Management Science 66 (5): 2050–2074. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2019.3296.

- Bellavitis, C., I. Filatotchev, D. S. Kamuriwo, and T. Vanacker. 2016. “Entrepreneurial Finance: New Frontiers of Research and Practice.” Venture Capital 19 (1–2): 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2016.1259733.

- Bellavitis, C., D. S. Kamuriwo, and U. Hommel. 2019. “Mitigation of Moral Hazard and Adverse Selection in Venture Capital Financing: The Influence of the Country’s Institutional Setting.” Journal of Small Business Management 57 (4): 1328–1349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12391.

- Bergh, D. D., B. L. Connelly, D. J. Ketchen Jr, and L. M. Shannon. 2014. “Signalling Theory and Equilibrium in Strategic Management Research: An Assessment and a Research Agenda.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (8): 1334–1360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12097.

- Bernstein, S., A. Korteweg, and K. Laws. 2017. “Attracting Early-stage Investors: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment.” The Journal of Finance 72 (2): 509–538. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12470.

- Bertoni, F., D. D’Adda, and L. Grilli. 2016. “Cherry-picking or Frog-kissing? A Theoretical Analysis of How Investors Select Entrepreneurial Ventures in Thin Venture Capital Markets.” Small Business Economics 46 (3): 391–405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9690-9.

- Bessière, V., E. Stéphany, and P. Wirtz. 2020. “Crowdfunding, Business Angels, and Venture Capital: An Exploratory Study of the Concept of the Funding Trajectory.” Venture Capital 22 (2): 135–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2019.1599188.

- Brush, C. G., L. F. Edelman, and T. S. Manolova. 2012. “Ready for Funding? Entrepreneurial Ventures and the Pursuit of Angel Financing.” Venture Capital 14 (2–3): 111–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2012.654604.

- Busenitz, L. W., J. O. Fiet, and D. D. Moesel. 2005. “Signaling in Venture capitalist—New Venture Team Funding Decisions: Does It Indicate Long–term Venture Outcomes?” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 29 (1): 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00066.x.

- Butticè, V., A. Croce, and E. Ughetto. 2021. “Network Dynamics in Business Angel Group Investment Decisions.” Journal of Corporate Finance 66: 101812. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101812.

- Capizzi, V., A. Croce, and F. Tenca. 2022. “Do Business Angels’ Investments Make It Easier to Raise Follow‐on Venture Capital Financing? an Analysis of the Relevance of Business Angels’ Investment Practices.” British Journal of Management 33: 306–326.

- Cardon, M. S., C. Mitteness, and R. Sudek. 2017. “Motivational Cues and Angel Investing: Interactions among Enthusiasm, Preparedness, and Commitment.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41 (6): 1057–1085. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12255.

- Carpentier, C., and J.-M. Suret. 2015. “Angel Group Members’ Decision Process and Rejection Criteria: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Journal of Business Venturing 30 (6): 808–821. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.04.002.

- Chakraborty, I., and M. Ewens. 2018. “Managing Performance Signals through Delay: Evidence from Venture Capital.” Management Science 64 (6): 2875–2900. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2662.

- Ciuchta, M. P., C. Letwin, R. Stevenson, S. McMahon, and M. N. Huvaj. 2018. “Betting on the Coachable Entrepreneur: Signaling and Social Exchange in Entrepreneurial Pitches.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 42 (6): 860–885. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258717725520.

- Claes, K., and B. Vissa. 2020. “Does Social Similarity Pay Off? Homophily and Venture Capitalists’ Deal Valuation, Downside Risk Protection, and Financial Returns in India.” Organization Science 31 (3): 576–603. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2019.1322.

- Clark, C. 2008. “The Impact of Entrepreneurs’ Oral ‘Pitch’ Presentation Skills on Business Angels’ Initial Screening Investment Decisions.” Venture Capital 10 (3): 257–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691060802151945.

- Clarke, J. 2011. “Revitalizing Entrepreneurship: How Visual Symbols are Used in Entrepreneurial Performances.” Journal of Management Studies 48 (6): 1365–1391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.01002.x.

- Clough, D. R., T. P. Fang, B. Vissa, and A. Wu. 2019. “Turning Lead into Gold: How Do Entrepreneurs Mobilize Resources to Exploit Opportunities?” Academy of Management Annals 13 (1): 240–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0132.

- Cohen, S. 2013. “What Do Accelerators Do? Insights from Incubators and Angels.” Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 8 (3–4): 19–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/INOV_a_00184.

- Collewaert, V. 2012. “Angel Investors’ and Entrepreneurs’ Intentions to Exit Their Ventures: A Conflict Perspective.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (4): 753–779. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00456.x.

- Colombo, O. 2021. “The Use of Signals in New-venture Financing: A Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Management 47 (1): 237–259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320911090.

- Colombo, M. G., M. Meoli, and S. Vismara. 2019. “Signaling in Science-based IPOs: The Combined Effect of Affiliation with Prestigious Universities, Underwriters, and Venture Capitalists.” Journal of Business Venturing 34 (1): 141–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.04.009.

- Colquitt, J. A., and C. P. Zapata-Phelan. 2007. “Trends in Theory Building and Theory Testing: A Five-decade Study of the Academy of Management Journal.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (6): 1281–1303. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.28165855.

- Connelly, B. L., S. T. Certo, R. D. Ireland, and C. R. Reutzel. 2011. “Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment.” Journal of Management 37 (1): 39–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310388419.

- Cooney, T. M. 2005. “What Is an Entrepreneurial Team?” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 23 (3): 226–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242605052131.

- Cottle, G. W., and B. S. Anderson. 2020. “The Temptation of Exaggeration: Exploring the Line between Preparedness and Misrepresentation in Entrepreneurial Pitches.” Journal of Business Venturing Insights 14: e00190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2020.e00190.

- Crawford, V. P., and J. Sobel. 1982. “Strategic Information Transmission.” Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 50 (6): 1431–1451. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1913390.

- Croce, A., F. Tenca, and E. Ughetto. 2017. “How Business Angel Groups Work: Rejection Criteria in Investment Evaluation.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 35 (4): 405–426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615622675.

- Croce, A., E. Ughetto, and M. Cowling. 2020. “Investment Motivations and UK Business Angels’ Appetite for Risk Taking: The Moderating Role of Experience.” British Journal of Management 31 (4): 728–751. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12380.

- Cumming, D. J., and J. G. MacIntosh. 2006. “Crowding Out Private Equity: Canadian Evidence.” Journal of Business Venturing 21 (5): 569–609. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.06.002.

- Cumming, D., and M. Zhang. 2019. “Angel Investors around the World.” Journal of International Business Studies 50 (5): 692–719. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-018-0178-0.

- De Clercq, D., V. H. Fried, O. Lehtonen, and H. J. Sapienza. 2006. “An Entrepreneur’s Guide to the Venture Capital Galaxy.” Academy of Management Perspectives 20 (3): 90–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2006.21903483.

- De Clercq, D., and H. J. Sapienza. 2006. “Effects of Relational Capital and Commitment on Venture Capitalists’ Perception of Portfolio Company Performance.” Journal of Business Venturing 21 (3): 326–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.04.007.

- Doblinger, C., K. Surana, and L. D. Anadon. 2019. “Governments as Partners: The Role of Alliances in US Cleantech Startup Innovation.” Research Policy 48 (6): 1458–1475. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.02.006.

- Downes, D. H., and R. Heinkel. 1982. “Signaling and the Valuation of Unseasoned New Issues.” The Journal of Finance 37 (1): 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1982.tb01091.x.

- Drover, W., L. Busenitz, S. Matusik, D. Townsend, A. Anglin, and G. Dushnitsky. 2017. “A Review and Road Map of Entrepreneurial Equity Financing Research: Venture Capital, Corporate Venture Capital, Angel Investment, Crowdfunding, and Accelerators.” Journal of Management 43 (6): 1820–1853. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317690584.

- Drover, W., M. S. Wood, and A. C. Corbett. 2018. “Toward a Cognitive View of Signalling Theory: Individual Attention and Signal Set Interpretation.” Journal of Management Studies 55 (2): 209–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12282.

- Drover, W., M. S. Wood, and A. Zacharakis. 2017. “Attributes of Angel and Crowdfunded Investments as Determinants of VC Screening Decisions.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41 (3): 323–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12207.

- Durcikova, A., and P. Gray. 2009. “How Knowledge Validation Processes Affect Knowledge Contribution.” Journal of Management Information Systems 25 (4): 81–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222250403.

- EBAN. 2021. European Early Stage Market Statistics: 2020. Brussels: EBAN.

- Ebbers, J. J., and N. M. Wijnberg. 2012. “Nascent Ventures Competing for Start-up Capital: Matching Reputations and Investors.” Journal of Business Venturing 27 (3): 372–384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.02.001.

- Edelman, L. F., T. S. Manolova, C. G. Brush, and C. M. Chow. 2021. “Signal Configurations: Exploring Set-theoretic Relationships in Angel Investing.” Journal of Business Venturing 36 (2): na. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106086.

- Elitzur, R., and A. Gavious. 2003. “Contracting, Signaling, and Moral Hazard: A Model of Entrepreneurs, ‘Angels,’ and Venture Capitalists.” Journal of Business Venturing 18 (6): 709–725. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0883-9026(03)00027-2.

- Engel, D., and M. Keilbach. 2007. “Firm-level Implications of Early Stage Venture Capital investment—An Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Empirical Finance 14 (2): 150–167. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2006.03.004.