Abstract

This paper explores how social media spaces are occupied, utilized and negotiated by the British Military in relation to the Ministry of Defence's concerns and conceptualizations of risk. It draws on data from the DUN Project to investigate the content and form of social media about defence through the lens of ‘capability’, a term that captures and describes the meaning behind multiple representations of the military institution. But ‘capability’ is also a term that we hijack and extend here, not only in relation to the dominant presence of ‘capability’ as a representational trope and the extent to which it is revealing of a particular management of social media spaces, but also in relation to what our research reveals for the wider digital media landscape and ‘capable’ digital methods. What emerges from our analysis is the existence of powerful, successful and critically long-standing media and reputation management strategies occurring within the techno-economic online structures where the exercising of ‘control’ over the individual – as opposed to the technology – is highly effective. These findings raise critical questions regarding the extent to which ‘control’ and management of social media – both within and beyond the defence sector – may be determined as much by cultural, social, institutional and political influence and infrastructure as the technological economies. At a key moment in social media analysis, then, when attention is turning to the affordances, criticisms and possibilities of data, our research is a pertinent reminder that we should not forget the active management of content that is being similarly, if not equally, effective.

Social media and its related technologies have afforded new opportunities for military personnel to engage in and contribute to representations of defence practice. While others have considered these issues in relation to the US military (Lawson, Citation2014; Robbins, Citation2007; Silvestri, Citation2013; Wall, Citation2006), the Israel Defence Forces (Caldwell, Murphy, & Menning, Citation2009) and Belgian soldiers (Resteigne, Citation2010), few have empirically analysed how social media spaces are occupied, utilized and negotiated by the British Military and how this might feed into wider strategic communicative practices. We consider these issues here by drawing on data from the DUN Project, an ESRC/DSTL-funded project investigating the conceptualization, operationalization and measurement of risk within strategic communication initiatives in the defence sector.Footnote1 Social media is increasingly at the forefront of strategic communication precisely because it is conceived of as offering distinct opportunities to engage and influence others by virtue of its immediacy, mobility and networked capabilities (DCDC, Citation2012). This is reflected in the Ministry of Defence's (MoD) Online Engagement Guidelines, where the affordances of social media as a tool for communicating defence issues are emphasized:

… harness new and emerging technologies, new unofficial online channels, and new unofficial online content in order to communicate and disseminate defence and Service messages and build defence and Service reputation. (Defence Online Engagement Strategy, Two-Star Approved Draft, Paragraph 19: ‘Strategic Intent’ cited MoD, Citation2009, p. 2)

At the same time, the MoD also position social media as a homogenous and unknown entity, unpredictable, uncontrollable and especially volatile because it cannot be understood, and thus managed, in the same way as traditional media (DCDC, Citation2012). This is articulated through the language of unpredictability and speed where emerging information can reconfigure (continuously) political and public perceptions of defence activities in a manner that is detrimental to strategic and institutional (military) objectives (Jones & Baines, Citation2013; Mackay, Tatham, & Rowland, Citation2011). Risk becomes positioned, therefore, as both risk to security and risk to reputation; that which either ‘reflects on wider Defence and Armed Forces activity’ or ‘relates to classified, operational, controversial or political matters’ (MoD, Citation2009, p. 10).

This paper explores the wider landscape of social media in relation to these concerns and conceptualizations of risk, but particularly in relation to the social media communications authored by military personnel who may present the greatest contingency. We explore the content and form of, and user engagement with, social media communications about defence practice through the lens of ‘capability’, a term that captures and describes the meaning behind multiple representations of the military institution. But ‘capability’ is also a term that we hijack and extend here, not only in relation to the dominant presence of ‘capability’ as a representational trope and the extent to which it is revealing of a particular management of social media spaces, but also in relation to what our research reveals for the wider digital media landscape and ‘capable’ digital methods. Here we consider the capabilities of enacting a media strategy within preconstituted techno-economic and algorithmic frameworks (such as Facebook or Twitter, for example). What emerges from our analysis is that while interventions in social media may be positioned as relatively ‘new’ in defence practice, the social media texts reveal familiar, traditional management techniques that generate the predictable, un-networked, monologic communications necessary for particular types of promotional and public relations activity. This raises critical questions regarding the extent to which ‘control’ and management of social media – both within and beyond the defence sector – may be determined as much by cultural, social, institutional and political influence and infrastructure as the technological economies. At a key moment in social media analysis, then, when attention is turning to the affordances, criticisms and possibilities of data,Footnote2 our research is a pertinent reminder that we should not forget the active management of content that is being similarly, if not equally, effective.

Method

The data presented here were collected over a three-month period from January to March 2014. In keeping with Altheide's notion of ‘progressive theoretical sampling’ (Citation1996, pp. 33–35) we cast a wide net across social media sites and scraped content that overtly engaged in defence issues using various online tools including RSS feeds, Feedly, Yahoo Pipes, Hootsuite and searching for an array of keywords through umbrella categories including, for example, services (Army, Navy, Airforce, etc.), Regiments (Parachute, Marines, etc.), military practices (strategic communications, combat, training, Herrick and operations), issues associated with the military or MoD (PTSD, wounded, defence cuts, pensions, strategic defence review, covenant, law, human rights, etc.), events (Armed Forces Day, etc.), geographic area (Helmand, Afghanistan, Iraq, etc.). Our aims were twofold: to develop a deeper understanding of the area of research in order to contexualize the second stage of social media analysis (track two of our social media analysis); and to take a ‘snapshot’ of online engagement in order to mine this more deeply through the subsequent techniques. We coded initially by: topic (e.g. ‘Recruitment’ (21% of data set), ‘Afghanistan' (15%), ‘mental health’ (5%), ‘equipment’ (4%)); narrative theme (e.g. ‘capability’ (38%), ‘comparison’ (26%), ‘progression’ (18%)); and by voice/authorship (e.g. ‘political’ (8%), ‘institutional’ (13%), ‘individual’ (4%), ‘community’ (2%), ‘external’ (38%)).

It is noteworthy that the authorship typologies we employed overlap with some of those used by the MOD in their Online Engagement Guidelines for service personnel (MoD, Citation2009). For example, they use the term ‘Personal’ to describe what we term Individual, that is, personal online presences by Service personnel outside their official duties. But, while the MOD use the term ‘Corporate’ to describe communications published in official MoD accounts and Service accounts (Army, RAF and Navy) we have distinguished these as ‘Political’ and ‘Institutional', respectively. This is because in contrast to the MoD we recognize the British Military is a complex institution engaged in a range of activities (diplomatic, political and institutional), with its own goals, culture and working practices and, consequently, its own distinct identity. By making a distinction between ‘Institutional’ (military) and ‘Political’ (government) then we are doing three things: paying due heed to the complexities of ‘Institutional’ communication strategies that are designed to appeal to multiple publics – one of which is the political; attempting to avoid a simplification of the media–polity–military relationship where ‘Institutional’ communications are understood as simply a continuation of state politics (see Maltby, Citation2012a); and attempting to consciously reflect on the way that the social shaping of digital data methods corresponds to digital findings (see Kennedy, Moss, Birchall, & Moshonas, Citation2015).

From our initial analysis key sites emerged as influential within this network: official blogs (Ministry of Defence, British Army, Royal Navy, Royal Air Force in particular), Facebook, YouTube and Twitter. Given that we were using key terms within the overt hashtag or title as the starting point, it is perhaps unsurprising that our initial findings indicate less heterogeneity than we imagined in terms of breadth or scope of location (see Anstead & O'Loughlin, Citation2011). While the second social media track analysis will speak to this issue (currently being undertaken), there are two significant issues to note here. The first is that the methods we employed are those frequently used in basic data mining techniques and therefore their limitations signify something much greater than the specific issues we detail below – they speak to the limitations of data ‘itself’, the importance of reflecting and acknowledging search terms, the assumptions about hashtags or titles transparently reflecting content, and the discursive (rather than visual) way algorithms work (see, e.g. Ampofo, Collister, O'Loughlin, & Chadwick, Citation2015; Anstead & O'Loughlin, Citation2011; Kennedy et al., Citation2015). We will return briefly to these issues in the conclusion. The second issue to note here is that we suspect this lack of heterogeneity is actually highly reflective of the successful (in MoD's terms) management of social media – and that this (despite the issues noted above) is deeply significant. Again, we will return to this below.

Once we had allocated typologies and themes, we then engaged more qualitatively with the texts, analysing discourse, aesthetics, representational tropes and narratives. In the following we use the dominant theme that emerged from our analysis: ‘capability’. While this term was not always overtly embedded into titles and texts (and therefore serves as a reminder for us of the need to qualitatively analyse), representations of ‘capability’ formed one of the strongest themes to emerge in the secondary coding of the material, accounting for 38% of the data set, the highest percentage within the theme category. As stated previously, we use the term ‘capability’ to capture the meaning behind multiple representations of the military institution and military personnel as ‘capable’, that is: ‘having the needful capacity, power, or fitness for (some specified purpose or activity), having general capacity, intelligence, or ability; qualified, able, competent’. Capability was referred to in a number of ways in the data and was subsequently coded for corporeal, institutional/cultural, technological and political capability. Representations of corporeal and institutional/cultural capability were the most prevalent within the data set accounting for 35% and 37% of the coding for the theme of capability, respectively. Technological and political accounted for 18% and 16%, respectively. For the purposes of this discussion we draw upon the two most dominant forms of capability references: corporeal, where representations of mental and physical capability emphasized corporeal strength, endurance and mental resilience; and institutional and cultural capability where representations emphasized a particular ‘culture’; of teamwork, co-dependence, professionalism, discipline and skill.

Capability

In what follows, we analyse a number of social media representations of ‘capability’ in order to highlight (overt and covert) representational tropes that speak to this concept.Footnote3 We suggest not only that these (supposedly individual) authored images and posts imitate classic public relations work of Media Operations (see Maltby, Citation2012b), but that they also actively engage with and promote ‘Service messages’ and help to build the reputation of the defence forces through the dominant narrative of capability. This, as we discuss, has a number of implications for the notion of ‘risk’ – and indeed, ‘capability’ – online.

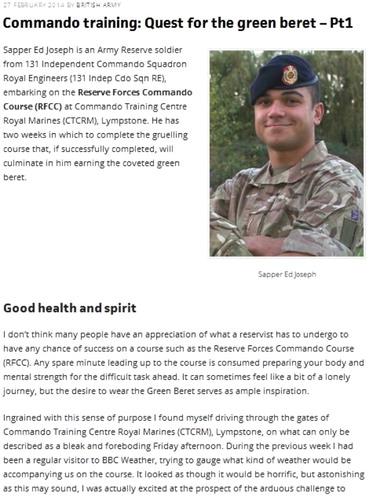

In the following example for instance, taken from Sapper Ed Joseph's blog post on the ‘Official British Army Blog’ about his experience of the Royal Marine Commando Training Course (), capability is explicitly constructed through Joseph's emphasis on physical and mental endurance and preparedness in the training process: ‘Any spare minute leading up to the course is consumed preparing your body and mental strength for the difficult task ahead … maintaining self-belief, remaining steadfast, and being prepared to go beyond the limit that ordinary people set themselves’. There is familiarity in this discourse, particularly around issues of professionalism, skill and endurance and how these relate to the capabilities of the military body per se. It is noteworthy for example that those who did not complete the course – while alluded to – remain obscured from view (see Taleb, Citation2008, pp. 100–102). Instead, what we see is a physically able, mentally strong and culturally capable recruit. This is in keeping with the underlying principles of the military institution as comprising a capable fighting force and long-standing representational strategies of soldiers who are battle ready or in various stages of preparation (Woodward, Winter, & Jenkings, Citation2009).

Whilst Joseph's post was authored through an ‘Institutional’ account rather than an individual one – a point that we return to later – similar narratives of capability were evident in the personal Facebook accounts of serving military members. In , for example, we see a direct association made between the ability to be brave in the face of injury with the resilience required for military life; in this case the Parachute Regiment. In , this idea of resilience and capability is linked directly with masculinities (‘if you're man enough’) reasserting a long-standing association between militaries and masculinity, particularly through the invocation of specific behaviours such as aggression, courage and cool (Barrett, Citation1996; Goldstein, Citation2001, p. 391; Highgate, Citation2003). Indeed in comment section of , we see these collapsed into the notion that fatal injury is an acceptable aspect of military work, emphasizing further the resilience needed to be a military ‘man’.

The second form of capability, and directly related to the first, was that of ‘cultural and institutional capability’. Here representations emphasized teamwork, co-dependence, professionalism and discipline. For example, the following appeared on an individual serving military member's Facebook page alongside an insignia for the Parachute Regiment: ‘It's these men that at true heroes every one off them utrique paratus why the airbourne brotherhood second to none never give up never leave anyone behind always outnumbered’. Here, members of the Parachute Regiment (again) are positioned as those who ‘never give up’ and ‘never leave anyone behind’ generating an explicit association between determination and discipline and co-dependency between military members in the execution of their work.

This positioning (and representation) of military work as a collective, group endeavour is not unusual. As Woodward and Jenkings (Citation2011) note, it is often only in the context of group ‘work’ that individual activities make sense to military members, reflected in their sharing and showing of images of the ‘group’ with others. It is unsurprising therefore that visual representations of co-dependency and collegiacy (as an expression of cultural and institutional capability) were dominant within our own data, particularly group photos on Facebook, and often as the banner header (– which have been deliberately blurred to protect the identities of those contained within the image).

The (relatively) formalized manner of these photographs – that are both composed and posed – not only reflects a specific institutional ethic of teamwork, uniformity and discipline but also a pride of membership with a particular ‘group’ (unit, regiment, platoon, etc.). They are an otherwise deliberate display of allegiance to the collective and the institution – explicitly expressed through the uniform – and the professionalism and skill that becomes associated with the collective endeavour (see Woodward & Jenkings, Citation2011). But there were also photographs of individual, uniformed men in the data corpus (and they were almost exclusively men), usually posted alongside accompanying text that overtly expresses ‘pride’ in the uniform and what it symbolizes ( and ).

We would suggest that the public posting of these images (of which the uniform is part) is an act of self-recognition and sharing of achievement, notable for the visual capturing of significant key moments – such as ‘passing out parades’ () – that signify official, acknowledged ‘entry’ into the military (see Jenkings, Winter, & Woodward, Citation2008). The uniform is not only an explicit expression of a military identity in this sense, but it is one that visibly distinguishes each serving member from the civilian community. And it is here in particular that we see the overarching theme of ‘difference’ in the ways the military represent themselves and their work through ‘capability’ narratives. If we return to Sapper Ed Joseph's blog post, for example, he makes a clear distinction between the capabilities of ‘ordinary’ people and those who meet the challenges of military work and training. We see something similar in the construction of what is required to be a member of the Parachute regiment (–). Combined, these representations generate a particular narrative of British military personnel as not only ‘capable’ in the literal sense (physically, mentally, culturally and institutionally) but also having a distinct, limitless, extraordinary capability that differentiates them and their activities from others (non-military). These postings, in effect, become an implicit ‘team’ performance that projects and sustains a particular image of the British military; and crucially one that coheres with institutional objectives. What is especially noteworthy, however, is that they do this in powerful and visual ways. The corpus of data that we have explicitly drawn on in this section relates to visual images and their accompanying text. On the one hand, these are additional compliments to the central message of capability, but they are also standalone, recognizable signifiers for the military. These are important points to note when thinking about social media analysis and its capability – and ones that we return to later – not least because visual data are remarkably absent from current data mining tools in ways that are clearly problematic when considering the above.

For now, we can see that taken together, these visual, textual, linguistic communications offer insight into an institutional identity that is purposefully constructed in accordance with the military's own need to build, retain and protect their own reputation – or public identity – as a credible, competent and enduring fighting force. This identity is distinctive, often constructed as apolitical and embodying – experientially as well as symbolically – the values associated with professionalism, cohesiveness, participation, duty and honour that are ‘extra’-ordinary’ (see Maltby, Citationin press; Woodward & Jenkings, Citation2011). Capability then encapsulates the familiar ‘face’ of the British military that is expressed internally (within the institution) and externally (through public communications and media). But this is not simply a promotional ‘face'; it is also a necessary ‘face’ for military work. Maintaining credibility as a committed, capable, fighting force is framed within a political remit that requires the joint action of all its members – from senior to junior service personnel – to collaborate in a unified performance of competency, determination and endurance. We have seen this throughout military interactions with traditional media and it is therefore of little surprise that it also emerges in social media spaces. Yet although familiar and predictable, these representations of ‘capability’, the subjects through which they are expressed and the techniques used to communicate them (visual, narrative, storytelling, testimony, etc.) are also revealing of how the individual serving military member situates and negotiates their own individual and institutional (social media) identity within these frameworks. On the one hand, their communications speak directly to (other) serving military personnel and the collective (especially through Facebook), but they also speak directly to a public audience in their explanation and celebration of military work (especially through blog posts, Twitter updates, etc.). In so doing, and as suggested above, they imitate the classic public relations work of Media Operations (see Maltby, Citation2012b). What is most notable then is that these communications rarely present risk to either operational security (OPSEC) or wider strategic ‘intent’ as articulated by the MoD, despite the MoD's positioning of social media as unpredictable, volatile and risky. Rather, based on the analysis above, we can see that communications appear to actively engage with and promote ‘Service messages’ and help to build the reputation of the defence forces through the dominant narrative of capability. Key to this, as implied above, is who authors the communication and how. It is to this issue of authorship that we will now turn to draw attention to the explicit and implicit management of social media that leads to the dissemination of the types of communications noted above.

Indi-tutional authorship: managed spaces?

As part of the MoD's Defence Online Engagement Strategy (2007) and outlined in the MoD Online Engagement Guidelines, service personnel are actively encouraged to engage in social media to discuss ‘what they do’ within the bounds of OPSEC (see MoD, Citation2009, p. 1). Within the broader framework of ‘risk’, we see this as an implicit but active attempt to manage and even intervene in perceived risk online, especially through the recruitment of ‘Sponsored’ online presences. As the term suggests, these ‘Sponsored’ presences are where military members discuss their work through their own or official social media accounts but with the sanctioning and authorization of their service (Army, Navy and RAF) and the MoD (Citation2009, p. 3). This strategy of the Sponsored presence can be seen as the culmination of a long-standing technique of using the ‘personal voice’ as both an effective story-telling device (Langellier, Citation1989) and an effective promotional tool in public relations work and online marketing (Arora et al., Citation2008; Christodoulides, Citation2009; Goldsmith, Citation1999; Kwon & Sung, Citation2011). Hence, it is through Sponsored presences that we see serving military personnel functioning as ‘ambassadors'Footnote4 for the defence community's wider public relations strategy (MoD, Citation2009, p. 4). With this in mind, we use the term ‘Indi-tutional’ to describe the characteristics of a Sponsored voice here where the ‘stories’ and ‘voices’ of Individual serving military personnel converge with the Institutional perspective to produce a key representational tool for wider defence efforts.

In light of the number of social media communications that were attributable to Individual military personnel in our data corpus, there is likelihood that some of these communications were authored by Sponsored presences. Certainly, some of the communications we analysed from Twitter and Institutional blogs had particular characteristics that would resonate with Sponsored presences. If we return to the blog posts discussed above, for example, the Individual voice of Joseph can be seen to merge and converge with the Institutional aims of the British military particularly in relation to recruitment and retention and within the context of the British Army recruitment campaign launched in January 2014. Given that Joseph's post appeared on the ‘Official British Army Blog’ which claims to host ‘soldiers and officers of the British Army in their own words’ the convergence of the Individual voice with the Institutional is especially clear. The key point here is that aside from the obvious utility of Joseph and blog posts in terms of reinforcing key ‘messages’, it is the framing of these messages in relation to the individual that becomes critical to the credibility and persuasiveness of the message. We see similar strategies employed across all Individual blog posts hosted on Institutional accounts, some of which are directly related to wider strategic aims and existing politically strategic narratives. Here the personal experiences and vignettes of serving personnel serve as a means through which the complexities of strategic and tactical aims become tangible and accessible. For example, Lisa Irwin's blog post – again on the Official British Army Blog – tells the story of her deployment with a medical team in Afghanistan. Here she emphasizes – among assertions of cultural and institutional capability – the transformative role of the British military in Afghanistan and, in doing so, implicitly legitimates British intervention while simultaneously reinforcing the wider institutional and political strategic narrative regarding progress and transformation, improved governance and the effective handing over responsibility to Afghans:

Not all casualties that have been sent to Shorabak [Emergency Department] have required [British] mentor input as some had injuries that the Afghan doctors are more than capable of dealing with on their own [my italics]; whilst others required a little guidance from us initially and we were then able to let the Afghans deal with the situation themselves.

Critically then, social media communications that are authored by Indi-tutional voices can not only be explicitly directed towards reinforcing political and institutional narratives of military capability – whether in the context of training, recruitment or military operations – they are also a means through which the story can be conveyed in a considered, controlled manner.

In our analysis of Twitter, we found similar strategies where conversational interactions (tweets, re-tweets and mentions) were used to assert, promote, uphold and defend particular definitions (and impressions) of military activity through Indi-tutional voices, and in a manner which reflects traditional media management techniques. This was especially apparent in situations where real or anticipated critiques of military activity or personnel, predominantly emanating from mainstream media articles, were re-tweeted and commented upon. In January 2014, for example, the Sheffield Star published a story about a British Army soldier convicted for assault despite his defence team claiming he suffered from mental health issues after tours in Afghanistan and Iraq. A serving member of the Armed Forces re-tweeted the article with his own comment on the accompanying link which subsequently generated a Twitter ‘conversation’ among other military members (). This ‘conversation’ reflected characteristics of the Indi-tutional voice in terms of both its form and content. All of the users asserted the ‘rogue’ behaviour of the soldier in question (‘[he] doesn't deserve to be in the army after behaviour like that, we've all seen bad things happen but doesn't make us act like that'; ‘no defence – no excuse’.), and questioned the credibility of his mental health diagnosis (‘it's an old excuse. Looking at the time line I would love to know his role & what he did in Iraq?’; ‘As you said it's an easy excuse. Stories like that make all soldiers seem like violent psychopaths’). But critically they also defended the institutional position by declaring that sufficient resources and help were available for those with mental health issues (‘ … plenty of help & support for people if they want it getting tired of people using service as an excuse’.

In their deliberate distancing of the soldier's behaviour from his service career, and by positioning him as an errant individual these tweets both defended the military institution – particularly in relation to notions of capability – but also closed down wider discussions (or concerns) about the culture of the military body per se (Woodward et al., Citation2009), particularly in relation to issues of mental health. This closing down is, of course, in keeping with the specificities of the Twitter platform which, like other forms of web interactivity, as many theorists have noted, is more conducive to statements and monologic communication unless users are called upon to protect their own relative (or organizational, institutional) position (Van Dijck, Citation2013; Coombs, Citation2007). At the same time, Twitter has also been noted for its ability to generate and articulate collective identity particularly through the act of re-tweeting (see Anstead & O'Loughlin, Citation2011; Baym, Citation2010). The re-tweeting in this example therefore suggests an amplification of the original ‘incapability’ issue among a particular collective in order that it can be publicly repaired. The point here is that the restoration of the capability narrative is not only evident in the content of the tweet but also in the act of re-tweeting with a comment. This is significant not just in terms of what it reveals about the coherence of collective Indi-tutional voices that collaborate to project and sustain a particular identity through content, but also because the manner in which this is enacted resonates with standard Media Operations techniques. We see here particularly the use of tacit definitions where definitions of a situation or issue are constructed in anticipation of critique – especially around certain topics and controversies that are familiar to the military institution – before the critique has been made, and in a manner that means it never has to be made (see Maltby, Citation2012b; see also Goffman, Citation1969). Given the current sensitivities that surround the mental health of service personnel returning from deployments, and the suggested correlation between mental health and anti-social behaviours, tacit definitions become a means through which to counter these sensitivities before they become asserted by others in the social media space.

Taken together, we can make a number of observations about these findings in relation to the Indi-tutional voice. The first is that there appears to be a discernible relationship between the social media platform and the mode of representation. Taking into account our previous visual analysis, it is clear that the affordances of Facebook with its focus on visuality and the individual voice can be differentiated from the story-telling affordances of blogs and the ‘conversational’ interaction of Twitter that are better aligned for Indi-tutional authoring. In other words, what we see is a convergence of ‘space’ and ‘voice’ into the management of Indi-tutional communications. The second and related issue is that in this convergence we see resonances with traditional ‘old media’ management techniques in relation to the content (capability narratives), the form (re-tweeting and tacit definitions) and the voice (collaborative performance, personification). In this sense, there is little new about the management of ‘new media’ spaces. Rather there is an augmenting, renewing and reconfiguration of traditional management techniques that have been transposed onto new technologies. The third, and again related, point is that by virtue of the internal military community comprising one of the key audiences at whom many of the Indi-tutional communications are directed, and given the emphasis on community building and military identity, all military personnel become indirectly included in the construction of ‘capability’ inherent in Indi-tutional communications because they reflect the very ethos and goals of the institution. As we have already noted, Individual military members rarely represent themselves in ways that undermine or contradict narratives of capability despite the potential to do so in these less managed spaces. Thus, while the Indi-tutional voice may be deliberately designed to construct and project a particular identity, and in a manner that generates impressions of accessibility and transparency, we see a similar identity being expressed by voices that are not Indi-tutional, sponsored or ‘managed’. This suggests to us that there is something else occurring in the management of social media in the defence sector that is beyond the immediate screen interface. Consequently, we argue that we must look critically beyond the social media communication to assess the social, cultural and political context in which social media is enacted and engaged. This can be done in two ways: first by looking ‘beyond’ in terms of users and people and second by looking ‘beyond’ in terms of flow, data and algorithm. The latter of these options we are currently undertaking in our Track two stage of analysis. The former is the focus of the following discussion. It is here that the more significant findings of our project can be located, not just in terms of what they might reveal about the management of people (rather than technology), but the extent to which this raises critical questions about the ways in which we, as scholars, approach the analysis of social media more broadly.

Individual authorship: managed users?

There are a number of ways in which we can interrogate the management of social media users – as people, authors and engagers – within the defence sector. The first is through the explicit construction of risk to both individual serving personnel and the military institution by virtue of the work they engage in; namely defence. Here the notion of risk becomes directly associated with the threat of an adversary who would wish harm to individual serving personnel, operational activity and the wider defence sector. This is formally articulated in communications doctrine and guidelines through the concepts of OPSEC and personal security (PERSEC). While OPSEC is the protection of information that may compromise the security of an operation or wider defence work, particularly that which could be used to an adversary's advantage, PERSEC is the protection of information that may compromise the personal security of individual service personnel. The MoD highlights categories of information that, if distributed through social media, may compromise PERSEC and OPSEC. These include personal information (name, address, date of birth, etc.), information about work (rank, position, unit, etc.), operational information (including mission-specific information, deployment details, casualties and morale). While some of these categories are relevant to the PERSEC of all online users, particularly evident in the debates around privacy or security online (see, e.g. Boyd, Citation2008, Citation2010; Coll, Citation2014; Nissenbaum & Howe, Citation2009) the risks for military personnel are constructed as especially serious and potentially fatal. The MoD claims that it is through access to these types of information that hostile intelligence agencies or terrorists may target individual personnel, their families, their colleagues, their units of work, and the operations and assets they are engaged with (MoD, Citation2009).

This construction of social media ‘risk’ – particularly in relation to privacy and security settings, location services and geo-tagging, status updates and comment – is perhaps best evidenced in the ‘Think Before You Share’ online campaign produced by the UK Government. The campaign includes a series of ‘Think Before You Share’ videos which are especially interesting in the ways that the threat and consequence of ‘unsafe’ online are signified (see –). As we can see in , ‘threat’ is denoted by a man in a balaclava, who is faceless, identity-less, wearing or holding weaponry and – most importantly – one whose threatening presence is often unknown to the others in the scene (i.e. relative, military member).

Figure 10. ‘Think Before You Share’ video image; ‘It may not just be your family and friends reading your status updates’.

Figure 12. ‘Think Before You Share’ video image: ‘Is it just your mates who know where you have checked in’.

These videos draw upon specific signifiers – visual and semantic – that have a long-standing history within military culture specifically in relation to the ‘unknown enemy’ and the need to protect one's own informational position through (and with) technology. In this sense, the taglines that accompany each video, ‘What kind of YouTube hit do you want to be’, ‘It may not just be your family and friends reading your status updates', etc., echo familiar tropes. For example, World War II posters designed to speak to emergent technologies of the time (telephony, telecommunications and radio) asserted that ‘Careless talk costs lives' and ‘Loose Lips Sink Ships’. The point here then is that the ‘informational’ risks associated with social media are neither new nor constructed in new ways, but instead can be located within a broader, historical context that appeals to a particular cultural identity within the military.

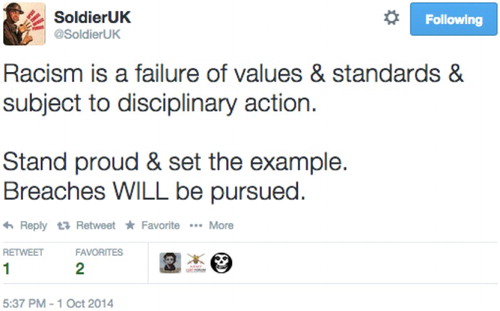

Although predominantly distributed through government online platforms (Twitter, Gov.uk website and YouTube) the wider principles of OPSEC and PERSEC behind the ‘Think Before You Share’ online campaign are also promoted through the SoldierUK Twitter account, authored and managed by the MoD Online Engagement Unit. SoldierUK is especially notable not just because of its active, purposeful yet monologic assertion of the ‘threat’ of unsafe online engagement as seen in and , but because it also has a dual purpose. On the one hand, it is the ‘MoD champion of social media safe practice’. At the same time it is also the ‘Advocate of UK military online standards and values’. SoldierUK therefore not only promotes the protection of security but, simultaneously, promotes the upholding of reputation. Consequently, in addition to distributing tweets that emphasize the risks of online behaviour typified by those in and – which again use characteristically threatening signifiers – SoldierUK also tweets about the need to uphold specific values associated with the military institution, alongside further threats of disciplinary action should ‘breaches’ be discovered ( and ).

Here then the communications that emanate from the SoldierUK account blur the distinction between what is of risk to security and what is of risk to the Institutional reputation. This is important because the act of citing OPSEC as a means through which to embargo the publication and dissemination of information that might otherwise be discrediting has been noted as a standard military media management technique (Maltby, Citation2012b; see also Bracken, Citation2009). Of course, the military would argue that a public, collaborative maintenance of standards is (once again) necessary for the effectiveness of the military's fighting power because values and standards have ‘functional utility’ and can threaten a mission if not upheld (see for example ‘Values and Standards of the British Army’, 2008, p. 3). With this in mind, the convergence of upholding and protecting security with upholding and protecting reputation is almost certainly part of the inculcation of serving military personnel with regards to their online behaviour, and is further evidenced by the foregrounding of disciplinary procedures on SoldierUK. While it could be similarly argued that the maintenance of reputation is critical to any organization's public credibility and effectiveness, the key difference with the military is that implicit within the construction of reputational risk is – once again – the fatal threat to serving personnel. And it is here, in the seriousness of the implications of the reputational risk, that the rationale for conflating security with reputation becomes hermetic.

Cumulatively then, what emerges from these ‘official’ communications (campaigns, SoldierUK, etc.) is the construction of social media spaces as intimidating, unsafe and ‘risky’ to individual service personnel and the wider military community. But more importantly, risk is constructed as emerging from within the military community, which, in turn, can (or will) be used against them. This is significant because data emerging from our own analysis suggest that there are occasions when identifiable military personnel do compromise their own PERSEC, and potentially OPSEC, by revealing precisely the kind of information they are advised not to under PERSEC and OPSEC. This information includes personal details, details of their families, their unit of work and even their rank. There appears to be no manifest intervention with regard to the dissemination of this information (for instance by SoldierUK or the MoD) despite MoD claims that they will intervene in OPSEC breaches. Yet, there is evidence of intervention into communications that might bring the military establishment into disrepute, for example, serving military members communicating racist or controversial political comments. In and , for example, we see the British Army's response to the emergence of a Facebook post by a Grenadier Guard who, on the discovery of the body of three-year-old Mikaeel Kular'sFootnote5 stated: ‘Fucking LOL to that paki who was found dead! 1 down many more to go!!’ The Facebook account on which the comment was originally posted was closed down later that day.

Figure 17. Screenshot from @BritishArmy Twitter account in response to emergence of racist Facebook post by a Grenadier Guard.

Figure 18. Screenshot from @BritishArmy Twitter account in response to emergence of racist Facebook post by a Grenadier Guard.

This example is interesting for a number of reasons. First, it is indicative of a military intervention in reputational matters. Racism in this sense becomes intolerable because of the disrepute it may bring upon the British military. Misogyny on the other hand, of which there was plenty of evidence within our data corpus of individual military accounts, did not incur intervention or indeed comment from other users despite it also undermining the values of the military institution in terms of gender equalities. Consequently, while the military institution is promoted as women friendly – particularly within recruitment campaigns – this is not reflected within the internal culture of the military itself if the social media accounts of individual personnel, and the lack of intervention in them, is representational. Second, and perhaps related, it was clear from the data that the British Army and SoldierUK acted only after other Twitter users brought the post to their attention. This suggests that they either have a limited capacity to systematically survey and intervene in individual members accounts, or that intervention only becomes necessary once information has been noted in the wider public domain. The latter is perhaps more in keeping with our findings above, where prompting from an outside source is interpreted as an indication for potential reputational damage, compelling the British Army and SoldierUK to act on reputational matters.

These latter points reveal the extent to which control cannot be effectively established through the technological infrastructures that may otherwise permit the surveillance and closure of particular communications and accounts. And this, in part, explains why the MoD do not request Individual users to seek clearance or authorization to make personal use of social media; because clearance is in effect redundant if users cannot be tracked, monitored and controlled effectively through the technology. Rather, it suggests that control exists within the management of the individual military social media users, as people. In other words, the risks associated with the unpredictable emergence of information can largely be contained through the inculcation of military personnel into the distinct culture and identity of the military that effectively demands – and generates – acquiescence with the safeguarding of their own institution, its working practices and goals. This resonates with traditional military techniques of control, enacted through embodied regimes (training, drilling, ordering, and hierarchies) where fear, discipline and allegiance to the collective identity (and body) become inculcated in the everyday practices of military personnel both within and beyond the work setting (see King, Citation2006, Citation2007; Newlands, Citation2013; Thornborrow & Brown, Citation2009). Indeed, inculcation into the culture and identity of the military institution is suggested through the social media communications themselves with their notable focus on themes that resonate with the military community, its culture and its ‘capabilities’. In this sense, the distinction between military personnel and civilians – so apparent in narratives of capability – is instrumental to the ways in which military social media users understand themselves through their military identity, which in turn becomes articulated in and through their social media usage. Moreover, it is this notion of ‘difference’ that is drawn upon in the MoD's explicit construction of social media spaces as threatening and ‘risky’ to encourage them to either adhere to particular forms of authorship or not to author at all. And it is here that we locate the MoD's supposed move from ‘risk aversion’ to ‘risk awareness’, where awareness becomes a means through which the management of users is better established. Inculcation therefore becomes the context for, and critical to, engendering ‘safe’ (in the MoD's terms) online practice not least because it appears obvious and naturally occurring as a manifestation of protecting the community and its reputation. Moreover it generates impressions of accessibility and transparency (rather than denied access, control and spin), which in turn helps bolster the credibility of both the communication and the institution. It is the management of people then within a particular social, cultural and political context that is at the core of what we are contending here, perhaps best summed up by Pippa Norris, the Head of the MoD Online Engagement Unit who claimed in 2011 that without risk awareness and openness about OPSEC people might just start their own online social media activities without the knowledge of the institutional chain of command.Footnote6 Here, Pippa is not only exposing a continued fear within the defence sector around the potential to lose control over the ‘message’, she is also revealing how ‘control’ is conceived of in relation to the user (people) precisely because the technology is uncontrollable, unknowable or unpredictable.

Conclusion

All of these observations then bring us full circle to the function and role of social media spaces within specific areas of the Defence sector, which is that they are entirely spaces for the practice of public relations, where the exercising of ‘control’ over the individual – as opposed to the technology – is highly effective. On the one hand, of course, this finding may be entirely obvious given the limited capacity of the MoD or SoldierUK to directly intervene in the techno-economic structures of social media. But our argument is that, despite this (or, indeed, because of this) the interventions and management that we have seen are incredibly effective. This suggests to us that powerful, successful and critically long-standing media and reputation management strategies are occurring within the techno-economic online structures. These are interventions made through and primarily around content rather than infrastructure, and they occur within the platform specificities and existing codes of practice. These are not the content management bots or bespoke code of Wikipedia (see Geiger, Citation2014; Niederer & van Dijck, Citation2010); they are overt interventions and practices that through their hypervisibility have become increasingly invisible. In the emergent world of data mining and digital methods, where concern is being raised around obfuscated structures of data mining and sharing, our findings suggest a continuation of traditional, visible methods of mass communication and management. They are a stark reminder to scholars researching the digital environment that content (rather than flow for example) matters. Our findings are therefore also a pertinent reminder about the limitations of data mining and indeed big data, and the continuing need to employ qualitative methods of analysis. The control and media management that is being exercised in these spaces is done through complex networks of wider military practice, cultures and representational strategies, which in turn only become overt when situated in these contexts. Indeed, the individualized voice of the serving personnel could be read as a wider shift towards individualism exacerbated by social media, but when such strategies are looked at complexly and wider as socio-cultural and political phenomena, they can also be understood as part of a wider military strategy. Our point is that such strategies in online spaces are becoming increasingly invisible – detrimentally so – because of a wider orientation towards and acceptance of the politics of social media that recognizes and accepts it as a space for individual self-promotion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Sarah Maltby is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Sussex. Her core academic interests centre upon the intersection between contemporary military practice and media practice. She is currently Principal Investigator for the ESRC/Dstl-funded DUN Project (Defence, Uncertainty and ‘Now’ Media: Mapping Social Media in Strategic Communications). She is author of Military Media Management: Negotiating the ‘Front’ Line (2012) and co-editor of Communicating War: Memory, Military and Media (2007) with Richard Keeble. [email: [email protected]]

Helen Thornham is a Research Fellow at the University of Leeds. Her research interests centre on gender and (new) media; narrative theories and mediation of technology; transformative use and appropriation of (new) media; feminist film theory and feminist new media theory. She is currently Co-Investigator for the ESRC/Dstl-funded DUN Project (Defence, Uncertainty and ‘Now’ Media: Mapping Social Media in Strategic Communications). Helen is author of Ethnographies of the Videogame (2011), Content Cultures (2012) with Simon Popple and Renewing Feminisms (2012) with Elke Weissmann. [email: [email protected]]

Daniel Bennett is a Research Fellow at the University of Sussex. His research interests lie in the representation of conflict through digital media including new forms of media coverage of warfare and the use of social media by military organizations. He is the author of Digital Media and Reporting Conflict (2013), a detailed study of the BBC's evolving coverage of war and terrorism. His research in this area has also been documented on his blogs, Mediating Conflict and Reporting War for the Frontline Club. He completed his PhD at the War Studies Department, King's College London in 2012. [email: [email protected]]

Notes

1. The project as a whole comprises a comparative analysis of the three data strands: Strategic (the conceptualization and operation of strategic communications and social media work within the Ministry of Defence); Users (the understandings and usage of social media among service personnel and their families and how this maps onto strategic objectives) and Social Media (the flows and representations of defence issues within the social media sphere and how this maps onto both the Strategic and User data strands). For the purposes of this paper, we focus on the Social Media strand.

2. For discussions on the obfuscated power relation of algorithms, see, for example, Andrejevic (Citation2011); Gerlitz and Helmond (Citation2013) in relation to sentiment analysis, Boyd and Crawford (Citation2012); Crawford and Boyd (Citation2012) in relation to big data. For discussions on non-human processes and decisions see Niederer and van Dijck (Citation2010) for discussions on bots or Geiger (Citation2014) for bespoke code. For wider discussions on dark nets see Bartlett (Citation2014). For critical discussion on social data see Cote (Citation2014); Manovich (Citation2011). For a discussion on digital methods see Kennedy et al. (Citation2015).

3. There are a few issues to note here with regard to the complex issues surrounding the ethics of reproducing user-generated social media content (UGC). First, the reproduction of UGC here was considered necessary to retain the nuance of the original communication, the visual and linguistic etiquette associated with it, and its original intended meaning; to provide an example of UGC that the reader can interrogate rather than an interpretation of UGC where the original meaning may have been significantly altered. Second, because we did not focus our analysis on individuals but only on content that emerged about defence within the public social media spaces all the UGC reproduced here is considered to be ‘in the public domain’ by virtue of being intentionally public and because the original author had already revealed their identity in the original publication. Despite this, unless communications derived from recognized public organisations and figureheads (i.e. British Army Blog, @UKSoldier) the anonymity of the author(s) has been respected and identifying material redacted in the reproduction of the UGC so as to not actively reveal the identity of the original author. Third, we have taken into consideration the possibility that the original author(s) can be potentially identified despite the redaction of identifying information. In particular, we are aware that original Twitter authors can be subsequently identified through a process of searching Twitter for the original tweet (by reproducing the content that has already been reproduced here) but we consider their original tweet to be intentionally public and thus ethical to reproduce here. In contrast, we are conscious that Facebook authors may have expectations of privacy particularly with regards to visual data despite the fact that researchers only accessed profiles that are publicly available. However, textual and image searches that might reveal the original author are not currently (technologically) possible within Facebook. Whilst images may be searched using different technologies and software, the searcher must have the original (un-embedded) image to conduct an effective search. This process would be impossible with the images reproduced here, first because they have been embedded within the article itself, and second because they have been deliberately obfuscated and blurred. All of these ethical implications were considered at the outset of the project design and subject to an extensive ethics process through the Universities of Sussex and Leeds and through the Ministry of Defence's own ethics process, MODREC (via Dstl).

4. Term used by Pippa Norris, Head of Online Engagement Unit, and MOD in interview 28 October 2011.

5. Mikaeel Kular was a young boy who went missing in Scotland in 2014. He was later discovered to have been murdered by his mother.

6. Interview with Pippa Norris, Head of Online Engagement, MoD. 28 October 2011.

References

- Altheide, D. L. (1996). Qualitative media analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Ampofo, L., Collister, S., O'Loughlin, B., & Chadwick, A. (2015). Innovations in digital research methods. In P. Halfpenny & R. Procter (Eds.), Text mining and social media: When quantitative meets qualitative, and software meets humans (pp. 161–192). London: Sage.

- Andrejevic, M. (2011). The work that affective economics does. Cultural Studies, 25(4–5), 604–620. doi: 10.1080/09502386.2011.600551

- Anstead, N., & Oloughlin, B. (2011). The emerging viewertariat and BBC question time: Television debate and real-time commenting online. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 16(4), 440–462. doi: 10.1177/1940161211415519

- Arora, N., Dreze, X., Ghose, A., Hess, J. D., Iyengar, R., Jing, B., … Zhang, Z. J. (2008). Putting one-to-one marketing to work: Personalization, customization and choice. Marketing Letters, 19, 305–321. doi: 10.1007/s11002-008-9056-z

- Barrett, F. J. (1996) The organizational construction of hegemonic masculinity: The case of the U.S. Navy. Gender, Work and Organization, 3(3), 129–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.1996.tb00054.x

- Bartlett, J. (2014). The dark Net: Inside the digital underworld. London: William Heinemann.

- Baym, N. (2010). Personal connections in a digital Age. London: Polity.

- Boyd, D. (2008). ‘Facebook's privacy trainwreck: Exposure, invasion, and social convergence’ in convergence. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 14(1), 13–20.

- Boyd, D. (2010). Making sense of privacy and publicity. Keynote address SWSX. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kl0VANhnvxk

- Boyd, D., & Crawford, K. (2012). Critical questions for big data: Provocations for a cultural, technological and scholarly phenomenon. Information, Communication and Society, 15(5), 662–679. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878

- Bracken, M. (2009). Military media interaction (Unpublished masters dissertation). Submitted to City University, Summer 2009.

- Caldwell IV, W., Murphy, D., & Menning, A. 2009. Learning to leverage new media. Australian Army Journal, 6(3), 133–146.

- Christodoulides, G. (2009). Branding in the post-internet era. Marketing Theory, 9(1), 141–144. doi: 10.1177/1470593108100071

- Coll, S. (2014). Power, knowledge, and the subjects of privacy: Understanding privacy as the ally of surveillance. Information, Communication and Society, 17(10), 1250–1263. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2014.918636

- Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163–176. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550049

- Cote, M. (2014). Data motility: The materiality of big social data. Cultural Studies Review, 20(1). Retrieved from http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/article/view/3832/3962

- Crawford, K., & Boyd, D. (2012). Critical questions for big data: Provocations for a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 662–679. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878

- Director of Doctrine and Concepts (DCDC). (2012) Joint Doctrine Note 1/12: Strategic Communication: The Defence Contribution. Ministry of Defence.

- Geiger, R. S. (2014). Bots, bespoke, code and the materiality of software platforms. Information, Communication & Society, 17(3), 342–356. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.873069

- Gerlitz, C., & Helmond, A. (2013). The Like economy: Social buttons and the data-intensive web. New Media and Society ifirst, 1–18.

- Goffman, E. (1969). Strategic Interaction. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Goldsmith, R. (1999). The personalised marketplace: Beyond the 4Ps. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 17(4), 178–185. doi: 10.1108/02634509910275917

- Goldstein, J. (2001). War and gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Highgate, P. (2003). Military masculinities: Identity and the state. Praeger: University of Michigan.

- Jenkings, K. N., Winter, T., & Woodward, R. (2008). Representations of soldier identity in print media and soldiers’ own photographic accounts. In J. Boll (Ed.), War: Interdisciplinary investigations volume 49, electronic publication (pp. 95–106). Oxford: Inter-disciplinary Press.

- Jones, N., & Baines, P. (2013). Losing control? The RUSI Journal, 158(1), 72–78. doi: 10.1080/03071847.2013.774643

- Kennedy, H., Moss, G., Birchall, C., & Moshonas, S. (2015). Balancing the potential and problems of digital methods through action research: methodological reflections. Information, Communication & Society, 18(2), 172–186. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2014.946434

- King, A. (2006). The word of command: Communication and cohesion in the military. Armed Forces & Society, 32, 493–512. doi: 10.1177/0095327X05283041

- King, A. (2007). The existence of group cohesion in the armed forces: A response to Guy siebold. Armed Forces & Society, 33, 638–645. doi: 10.1177/0095327X07301445

- Kwon, E. S., & Sung, Y. (2011). Follow me! Global marketers’ Twitter Use. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 12(1), 4–16. doi: 10.1080/15252019.2011.10722187

- Langellier, K. (1989). Personal narratives: Perspectives on theory and research. Text and Performance Quarterly, 9, 243–276. doi: 10.1080/10462938909365938

- Lawson, S. (2014). The US military's social media civil war: Technology as antagonism in discourses of information-age conflict. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 27(2), 226–245. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2012.734787

- Mackay, A. M. G., Tatham, S., & Rowland, L. (2011). Behavioural conflict: Why understanding people and their motivations will prove decisive future conflict. Saffron Walden: Military Studies Press.

- Maltby, S. (2012a). The mediatization of the military. War, Media and Conflict, 5(3), 255–268. doi: 10.1177/1750635212447908

- Maltby, S. (2012b). Military media management: Negotiating the ‘Front’ line in mediatized war. London: Routledge.

- Maltby, S. (in press). Remembering the Falklands war: Media, memory and identity. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Manovich, Lev. (2011). Trending: The promises and the challenges of big social data. In M. K. Gold (Ed.), Debates in the digital humanities (pp. 460–475). Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

- MoD. (2009). Online engagement rules. London: Ministry of Defence Publication.

- Newlands, E. (2013). Preparing and resisting the war body: Training in the British army. In K. McSorley (Ed.), War and the body: Militarisation, practice and experience (pp. 35–50). London: Routledge.

- Niederer, S., & van Dijck, J. (2010). Wisdom of the crowd or technicity of content? Wikipedia as a sociotechnical system. New Media and Society, 12(8), 1368–1387. doi: 10.1177/1461444810365297

- Nissenbaum, H., & Howe, D. (2009). TrackMeNot: Resisting surveillance in web search. Retrieved from http://www.nyu.edu/projects/nissenbaum/papers/HoweNissenbaum.pdf

- Resteigne, D. (2010). Still connected in operations? The milblog culture. International Peacekeeping, 17(4), 515–525. doi: 10.1080/13533312.2010.516661

- Robbins, E. L. (2007). Muddy boots IO: The rise of soldier blogs. Military Review, 87(5), 109–118.

- Silvestri, L. (2013). Surprise homecomings and vicarious sacrifices. Media, War & Conflict, 6(2), 101–115. doi: 10.1177/1750635213476407

- Taleb, N. N. (2008). The black swan: The impact of the highly improbable. Penguin: New York.

- Thornborrow, T., & Brown, A. D. (2009). ‘Being regimented’: Aspiration, discipline and identity work in the British Parachute Regiment. Organization Studies, 30(4), 355–376. doi: 10.1177/0170840608101140

- Van Dijck. (2013). The culture of connectivity. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

- Wall, M. (2006). Blogging gulf war II. Journalism Studies, 7(1), 111–126. doi: 10.1080/14616700500450392

- Woodward, R., & Jenkings, N. K. (2011). Military identities in the situated accounts of British military personnel. Sociology, 45(2), 252–268. doi: 10.1177/0038038510394016

- Woodward, R., Winter, T., & Jenkings, K. N. (2009). Heroic anxieties: The figure of the British soldier in contemporary print media. Journal of War & Culture Studies, 2(2), 211–223. doi: 10.1386/jwcs.2.2.211_1