ABSTRACT

This article discusses activists’ need to reflect on how achieving social media visibility might translate into vulnerability. In order to provide activists with a tool for this reflection, the Stepping into Visibility Model has been developed and applied to two case studies: (a) an activist group in a Brazilian favela using social media for protection against police brutality and (b) a Kenyan photographer, affiliated to an art-ivist (artistic and activist) collective, producing images of Nairobi at night to tackle social anxiety issues. The research draws from sociological insights on the concept of ‘visibility’ and adopts a case study methodology combined with ethnographic approaches. By adopting a Global South perspective, it discusses counter surveillance efforts in ways that go beyond techno-legal solutionism (Dencik et al, Citation2016) and in periods outside that of big-scale protests (McCosker, Citation2015). By devising this model, we hope to offer a contribution on how marginalised communities can be better informed when they encounter unintended negative visibility.

1. Introduction

This article focuses on the ambiguous nature of visibility, a concept that is central to social sciences and to studies of social media activism. Authors (Brighenti, Citation2007; Uldam, Citation2018) often refer to the dual outcomes of visibility, consisting of (1) empowerment and recognition and (2) surveillance and control. However, these outcomes are deeply intertwined as recognition can easily turn into surveillance and vice-versa (De Backer, Citation2019). This article analyses such merging ambiguities by presenting a study based on how media activists and art-ivists, artists with an activist vocation, use social media to fight marginalisation in Brazil and Kenya.

It seeks to offer a context-specific Global South perspective, going beyond the social media visibility achieved during large-scale protests (McCosker, Citation2015) and the translation of activists’ counter surveillance efforts into techno-legal solutions (Dencik et al., Citation2016). The term ‘Global South’ adopts a flexible and broad definition; this is not tied to a literal Southern geographic location but rather to a geography of injustice and oppression (de Sousa Santos, Citation2015, p. 4).

We have devised a model, the Stepping into Visibility Model, which sheds light on what we describe as the Brazilian and Kenyan activists’ ‘visibility journeys’. We apply this model to two case studies: (a) Maré Vive – a collective of media activists based in one of Rio de Janero's largest favelas that created social media profiles to discuss issues of social inequality and to fight racist police brutality and (b) PAWA 254 – an organisation set up by the award-winning photographer Boniface Mwangi to provide training, support and protection to young Kenyan arti-vists. Here, we focus on the work of one photographer – Msingi Sasis – who created the platform ‘Nairobi Noir’, employing a ‘film noir’ aesthetic to produce images of Nairobi at night and discuss social issues such as homelessness, prostitution, and the gap between the rich and the poor.

In both countries, social media usage is one of the most popular online activities. In Brazil, approximately 66.5% of the population (141.5 million users) are on social media and users spend on average almost four hours per day on social networking platforms. The most popular platforms include Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube (Navarro, Citation2020). In Kenya, 32.23% of the population (17.58 million) uses social media (Degenhard, Citation2021), and a Satista survey conducted in May 2020 revealed that 79% of respondents between the ages of 18 and 64 reported that they used social media networks such as Facebook regularly (Kunst, Citation2020)

Our research suggests that in both contexts a higher social media visibility leads to critical moments that need to be overcome so that activists can continue using social media for socially progressive causes. These include being victims of online attacks, such as hate speech and reputation destruction, which can turn into physical attacks. By presenting the model, it is hoped to offer activists a contribution on how to plan their visibility journeys better, particularly when they literally step into unintended negative outcomes. By sharing these experiences from and between Brazil and Kenya, we hope to contribute to boosting South-to-South dialogue, opening further avenues for activist research and research-informed activism. A caveat is that the model might apply to Global North contexts as well. Here, we do not wish to claim that the critical consequences of visibility are exclusive to activist communities in the Global South. Our purpose was to develop a visibility model that stemmed from Global South activist activities as a way to offer an alternative to models that are often based on Global North experiences.

2. Visibility from a Global South perspective

The concept of ‘visibility’ has been widely used in gender and minority studies, being associated with people who have been neglected, ignored or rendered invisible in society. This has been the case with the residents of favelas and slums in Brazil, Kenya and cities all over the world. Issues such as identity politics, class and poverty rely on visibility being addressed whilst social movements rely on having injustices made visible in their struggles against such injustices. Invisibility, on the other hand, creates exclusion and marginalisation (Brighenti, Citation2010; Uldam, Citation2018; p. 44). New technologies, particularly social media, have emerged as important tools to promote visibility in an empowering sense. Some of their advantages include widespread use, ease of access and the ability to bypass mass media, exposing government wrongdoings or helping marginalised groups to manage their own social image or simply tell their own stories in their own terms.

However, visibility is a double-edged sword because it can also work as a means of control. The visibility that the internet technologies confer to alternative civil society actors can easily result in surveillance. Private companies and governments might use such technologies to monitor them, censor them and contain their dissenting voices. For many authors (Bucher, Citation2012; De Backer, Citation2019; Uldam, Citation2017), Foucault’s (Citation1977) metaphor of the ‘panopticon’ prison model provides a starting point for discussing surveillance and control. Brighenti calls attention to visibility's asymmetric character: in an ideal natural setting, ‘the rule is that if I can see you, you can see me’. However, the relation of visibility is often asymmetric; the concept of intervisibility, of reciprocity of vision, is always imperfect and limited (Citation2007, p. 326). The panopticon's efficiency depends upon the invisibility of the watcher. At the same time, the role of invisibility is not simply to highlight the power of the authorities who watch but to render the panopticon efficient via uncertainty. Moreover, it is worth noting that surveillance, in itself, does not instil discipline as there also has to be the threat (and presumably at some point, the actuality) of punishment. This means that surveillance has to be backed up by power. It can amplify power but cannot serve as the basis of power itself. According to Brighenti, we are faced with ‘regimes of visibility’, which are highly dependent upon contexts and complex social, technical and political arrangements, making visibility a deeply ambiguous phenomenon (Citation2010, p. 3).

For activists at the margins of society, visibility on social media is mostly achieved in periods of large-scale protests. As McCosker notes, extensive literature has examined social media's role in amplifying and proliferating the voices of marginalised people, generating possibilities for civic participation in varied contexts, such as in Egypt, Hong Kong and Spain (Citation2015, p. 1). Whilst there is a greater focus on the intertwining of visibility and social media in light of specific large-scale events, we have opted to highlight the steps that activists encounter in what we refer to as their ‘visibility journeys’. By visibility journeys, we refer to the context-specific variations of visibility levels across time, which are dependent upon the different histories and unique characteristics of the activist groups. We suggest that visibility can be analysed as a path where different milestones are reached as different groups move forward (or backwards) with their activist work. Authors such as De Backer (Citation2019) have made the important acknowledgment that visibility can be cyclical. Our research confirms the cyclical nature of visibility but what we wish to add is a search for visibility journey patterns amongst groups in different (particularly Global South) contexts. We do not wish to do this in a deterministic way though, as if a simple visibility formula could predict the future of different activist groups. Our aim is to raise reflection on visibility-related elements that activist groups might have in common, sharing experiences and lessons on how to deal with the vulnerability associated with visibility.

Even when activists are aware of the problematic dynamics and consequences of surveillance, many of them are forced to take the risks in exchange for the reach and mobilising capacities afforded by social media visibility. For instance, Dencik et al. found that ‘the dependence on mainstream social media for pursuing activist agendas undermined efforts to actively circumvent or resist surveillance practices’ (Citation2016, p. 6).

An important gap in the literature on visibility and activism emerges from the fact that the majority of studies are written from a Global North perspective, addressing experiences in European countries, such as Denmark (Askanius & Uldam, Citation2011), Germany (Neumayer et al., Citation2016) and the UK (Dencik et al., Citation2016), amongst others. Therefore, this research offers a contribution to the growing literature on digital activism from the Global South (Milan & Treré, Citation2019).

Despite major differences in terms of policing and public safety policies in Brazil and Kenya, the oppressive character of these policies have similar consequences on people's daily lives. Having researched both contexts, Chloe Villalobos demonstrates that they ‘are rooted in a sense of inevitability, framing heavy-handed policing of poor, working-class, informalised areas as the sole solution to their respective security issues’ (Citation2019, p. 41). Additionally, media portrayals characterised by binary oppositions of the ‘formal’ versus the ‘informal’ city, the ‘good citizen’ versus the ‘criminal person’ and the ‘State’ versus the ‘enemy’ marginalise poverty and normalise daily killings. In line with this discourse, ‘those who are named as “bandidos” in Brazil or ‘thugs’ in Kenya, can and should die’. (Villalobos, Citation2019).

These issues matter because they bring additional challenges to ways in which activists work with social media visibility to combat marginalisation. One example is provided by looking at activist participation from a Global South angle. Drawing from the perspective of radical democracy (Mouffe, Citation2005), Neumayer and Svensson offer contours of activist types along two axes. The first axis revolves around how participants identify in relation to other social actors and institutions, such as media organisations, government authorities and the police, and whether this other is conceived as an enemy (antagonism) or as an adversary (agonism) (Citation2016, p. 138). The second axis revolves around activists’ readiness to act in civil disobedience, in general, and in violent action and property damage, in particular (Citation2016, p. 132). In our cases (Brazil and Kenya), we suggest that slum communities’ activism is not so much driven by how these communities look at other social actors. Rather, this needs to be about how societal forces look at and otherise slum communities as cities’ enemies that need to be excluded and even eliminated. This represents a subtle changed order of words – focusing on how they are looked at rather than looking at other social actors. However, this does matter because it implies that slum activism is shaped precisely as a response to slum communities being treated as enemies, having their citizenship denied and their voices suppressed.

Tatiana Lokot, whose work was conducted in Russia, discusses how activists have adopted strategies for being seen without being in danger. These include engaging in reverse surveillance of law enforcement during protest rallies by posting regular updates to social media and providing photographic and video evidence of police surveillance or arrests (Citation2018). There have also been attempts to name these efforts ‘sousveillance’, from the French ‘sous’, or ‘the surveillance from below’ (Mann, Citation2004, p. 620).

In addition to ‘sousveillance’, work on lateral or horizontal surveillance is relevant for our research. Here, Pearce, Vitak and Barta’s (Citation2018) study is illuminating because it analyses the context of Azerbaijan, a non-Western authoritarian post-Soviet State. Formal mechanisms are frequently put in place to discourage and punish political dissidents by humiliating, imprisoning or even physically attacking them. Drawing from a qualitative study of young dissident Azerbaijanis, their study's purpose aligns with our own research is a sense that considers the management strategies that entail risks and benefits ‘associated with increased visibility when sharing marginalised political views through social media’ (p. 1311). However, their focus lies on a less obvious relational outcome of achieving visibility on social media: the risk of dissolution of peer relationships when friends and family members watch and disagree with the content posted by political dissidents. Yet, ‘for many participants, the benefits of finding likeminded others and support as well as the ability to widely disseminate information were deemed worth the risks’ (p. 1323).

Moving to social media visibility risk in the Brazilian context, we can find similarities. Refering generally to activists who become visible on social media, Marques and Nogueira (Citation2012) note that for activists, engaging in debates is always risky because they perceive debates as exclusionary processes led by elite circles. In this way, when they chose to take these risks, they are very aware of their social locations from the margins of such privileged circles. In addition to creating communities of ‘likeminded dissidents’ (Pearce et al., Citation2018), the disruptive communicative affordances of social-media-visible activism make the risks worthwhile. Whether activists are subjected to top-down or lateral surveillance, social media visibility is still valuable because it ‘defies hegemonic discourses and modes of thought’ (Marques and Nogueira, Citation2012, p. 146).

Thus, it appears as if surveillance – whether it is top-down or lateral – in inevitable. Except from engaging in watching from below (Mann, Citation2004) would it be possible to block or sabotage surveillance? Dencik et al. (Citation2016) refer to such possibilities as univeillance efforts. The authors note that much resistance to surveillance has centred on providing secure digital infrastructures to activists, which include communication methods that are strengthened through encryption (Citation2016, p. 4). However, the problem is that these efforts tend to focus on techno-legal solutionism, which means they ‘have largely remained within a specialised discourse and a constituency of experts’ (Dencik et al., Citation2016, p. 5).

In this article, we follow this train of thought by analysing how activists in Brazil and Kenya have experienced surveillance and how they have managed their different regimes of visibility. However, we wish to place visibility here in the context of a visibility journey, offering a tool that activists can use for reflecting upon the consequences that different degrees of visibility might have in their lives and, potentially, plan their visibility journeys better. It is worth noting here that quickly achieving significant levels of visibility for many marginalised groups or individuals can happen almost accidentally. This points to the importance of what happens when these social actors ‘step into visibility’ and the strategies they adopt to deal with both positive (recognition, empowerment, reach) and negative consequences (surveillance, control, risks).

3. Methodological approach: developing the Stepping into Visibility Model

The two case studies presented in this article are interpretative case studies (Merriam, Citation1998), as they are used to develop the Stepping into Visibility Model inductively, mapping out how visibility affects activist groups in a digitally-pervaded context.

This article focuses on Brazil and Kenya, two countries located in the Global South that share important similarities. Nairobi and Rio are global cities marked by stark social inequalities and social conflict. Their urban environments reveal State policies that tend to discriminate against the economically vulnerable populations with precarious transportation systems, poor access to health and education, and public safety policies that often disrespect their rights. Extra-judicial killings are common in informal settlements in Nairobi and in Rio's favelas as the ‘war on drugs’, amongst other issues, serves to justify the adoption of a ‘shoot first and ask questions later’ logic (Villalobos, Citation2019).

The Stepping into Visibility model stems from an ethnographic research that included the following steps of data collection:

Digital ethnographic observations of favela mediactivist initiatives in Brazil, particularly Maré Vive's (@marevive) Facebook page between the months of January and December 2017. Conducted by the second author in Brazil, the data had been collected in the year prior to the start of the eVoices: Redressing Marginality Project, in 2018, and one year after the Rio Olympics, when issues concerning the heavy handed policing of favelas were a hot topic in the Brazilian public sphere. This provided the empirical basis for the subsequent research with Kenyan art-ivists as part of the eVoices: Redressing Marginality project in 2018. The digital ethnographic research in Brazil helped us draw out themes and draft the research questions that were employed in the interviews in Brazil and Kenya.

9 in-depth interviews with Kenyan ‘art-ivists’, during the event ‘In/visible Margins’ promoted by the eVoices Network in the city between 20 and 25 August 2018; and 8 in-depth interviews with Brazilian favela activists conducted throughout 2018 (see below).

Ethnographic field notes produced by the authors during four events promoted by the eVoices Network in Niteroi, Brazil (May 2018) and in Nairobi, Kenya (August 2018) as overt outsider participants (McCurdy and Uldam’s, Citation2014).

Table 1. Sample of Interviews (Source: the authors).

Ethical approval for conducting this research was given by the Ethics Committee at Bournemouth University and at Universidade Federal Fluminense. For safety reasons, the real names for the activists involved in the Maré Vive initiative are not revealed. Msingi Sasis has given us permission to use his real name as his story has been made public in many media outlets in Kenya and abroad. Whenever images captured from social media are used, the names of people making comments or reacting to the content of the posts are omitted.

The two initiatives that we chose for the application of the Stepping Into Visibility Model – Maré Vive (MV) and PAWA 254 / Nairobi Noir – represent collectives of activists/art-ivists. On social media, Maré Vive is one of the favela activism profiles with the highest number of likes – almost 165,000 on Facebook. In Kenya, PAWA 254, whose Facebook page had 35,000 likes, represented a collective of artists. Rather than choosing the anonymity route, the organisation aimed to gather a group of art-ivists under one umbrella organisation whose founder, Boniface Mwangi, is a highly visible personality on the Kenyan social media landscape, with 408,000, 122,000, and 1.6 million followers on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, respectively. Within PAWA 254, the art-ivists we interviewed had mostly just started their activist work. In this context, Msingi Sasis stood out as he was a well-established photographer. His story presented a fascinating case to analyse issues of visibility to the significant ups and downs that he reported on his visibility journey.

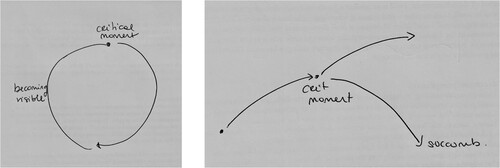

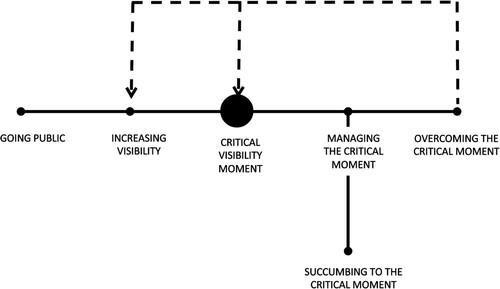

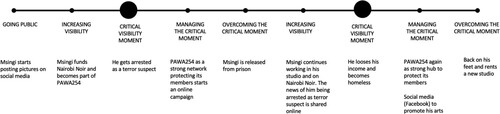

After conducting interviews in both countries, we analysed the transcripts in a manner that was informed by grounded theory. This allowed us to discover and propose a theoretical model that was guided by the data that was systematically obtained (Glaser and Strauss, Citation1967). First, each of the two authors coded the same four transcripts (two from Brazil and two from Kenya). Then, they discussed and refined the coding and the first author applied such codebook to all the remaining transcripts. The second author reviewed them, made suggestions and produced a final version of the coded transcripts. The theme of visibility as a double-edged sword for activists emerged from the early stages of the project and was confirmed during the coding process. As a result of their exchange of ideas, the first author started to manually draw a mind map of research themes to understand if chronological patterns could be established. The first sketches of the model included the drawing of circles, curves and spirals (see ). As the model evolved, the author chose steps to represent patterns in terms of visibility stages. These also provided a visual metaphor for when activist groups ‘stepped into’ unintended visibility, which could have negative and positive implications. In what follows, we present our graphic representation of the model and apply it to the case studies ().

4. Applying the stepping into visibility model to the case studies

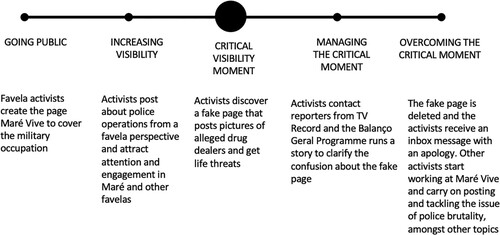

4.1. Maré Vive: social media for human rights protection

On Sunday, 30 March 2014, the Government deployed Federal troops to Complexo da Maré, a network of sixteen favelas, located in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro. Consisting of 2700 military officers, armoured tanks and machine-gun jeeps, the occupation was planned to last until July 31, 2014, shortly after the FIFA World Cup finished (Lisboa, Citation2014). It was in this tense context that a group of young mediactivists from Maré decided to start a Facebook page called Maré Vive (https://www.facebook.com/Marevive/; @Marevive). The idea was to cover and monitor the military occupation, adopting the perspective of favela residents.

(a). Going Public

This step occurs when activists’ initiatives are at emergent stages. They then adopt strategies to spread their messages and call for attention to their causes and struggles. In Maré Vive's case, this was associated with the idea of establishing a ‘sousveillance’ (Mann, Citation2004) tool to protect the community. Residents and activists could film, photograph or receive videos and photos to document any abuses from authorities. However, activists preferred to describe the initiative not as a response to surveillance against them, but rather as an ‘us by us’ philosophy, which manifested when favela residents could become narrators of their own stories. According to Pedro (fictitious name), ‘Maré Vive is made possible by all residents Maré’ (Interview with Maré Vive activist, December 1, 2017).

(b). Increasing Visibility

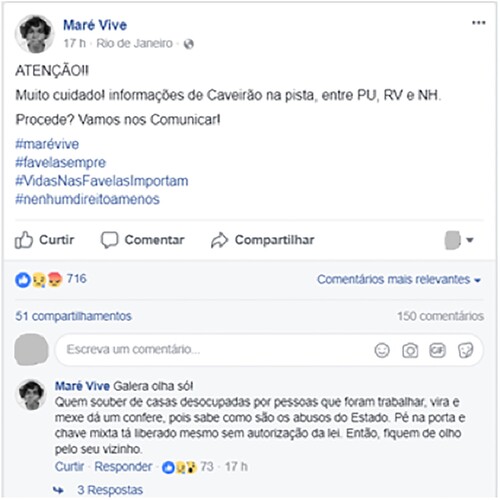

This means that activists are being successful in spreading their message to their constituencies as well as wider publics. With groups that present significant online activity, this might correspond to the moment when achieving high engagement metrics on social media, for example. In Maré Vive's case, following the creation of the page, a storm of comments, observations and complaints against abuses from the authorities were shared on social media using the hashtags #OqueaMarétem (what Maré has), #dedentrodaMaré (inside Maré) and #MaréVive (Maré Lives). The page then amassed fifty thousand ‘followers’ and ‘likes’ in three months. Run by three activists, who were constantly online answering questions and checking for updates, it started to publish posts regularly about different topics, such as local events, job and education opportunities, motivational messages and images referring to a collective favela memory. Yet, regardless of its publishing of a wide variety of content, the page started to attract attention in Favela da Maré, other favelas and non-favela neighbourhoods for publishing regular real-time updates when the police carried out operations in the favela ().

Figure 3. Post published at 05:17 am on November 27, 2017 (translation below) ‘Attention! Be very careful! We received information about a police vehicle between Parque União, Rubens Vaz and Nova Holanda. Is this true? Let's communicate. #marevive #Livesinthefavelasmatter #notonesinglerightless’.

Indeed, there are two substantial challenges here for favela activists and residents. The first one is social in character as it relates to the issue of police brutality, whilst the second one is spatial in character, deriving from the vast dimensions of the Maré Complex, with all its 17 areas. In order to tackle such challenges, Maré Vive demonstrates competence when employing two key phrases in its posts, which are ‘is this true’? – to attest the truth of the information published and ‘let's communicate’. All these represent tactics that activists and residents collectively employ so that the issue of police brutality can be widely seen whilst minimising the dangers implied in denouncing it (Lokot, Citation2018).

(c). Critical Visibility Moment

Our research indicates that a high level of visibility is likely to lead to a critical moment. This is often unpredicted and influenced by activists’ marginalised and ‘otherised’ standings in society. In this way, activist groups achieving peak visibility inevitably place themselves in a vulnerable position, as they became victims of attacks and repression by authorities. With Maré Vive, the Facebook page quickly became a visible resource for everyday life survival. However, this came at a high cost, creating problems for the activists. In 2015, one year after it was created, the activists were shocked to spot a fake version of the Facebook page. This fake page had started publishing photos of alleged drug dealers, which put the real page administrators’ lives in danger as they received death threats both from the police and the drug gangs. Such hostility, the activists suggested, might have resulted from the rapid visibility that Maré Vive attained whilst denouncing police brutality during the military occupation in the favela.

(d). Managing the Critical Visibility Moment

The ways in which activists deal with this critical moment are essential for determining the lifecycle and, ultimately, the fate of their initiatives, as well as the reach of the fourth visibility stage. To protect themselves, the Maré Vive activists decided to look for their contacts and to get in touch with reporters from TV Record, a free-to-air commercial television network. In this way, they were able to challenge the mainstream media's frames of silence (Lokot, Citation2018, p. 342) in relation to favela residents and favela life. The strategy was successful because TV Record ran a story about the fake page on its lunchtime programme called Balanço Geral. This story helped clarify the confusion, showing that the real page Maré Vive aimed to publish local news from a favela perspective rather than disclosing the identity of criminals.

(e). Overcoming the Critical Visibility Moment

If the strategies set in place are successful, the group is able to overcome the crisis and to work on its long-term goals, such as whether the group aims to grow and achieve larger constituencies or, on the contrary, decide to become more hidden from the public eye. In cases where the group wants to grow and achieve greater visibility and is successful in doing so, the cycle would repeat with a new critical visibility moment hitting the group and calling for a new set of strategies being put in place to overcome or succumb to it. After the Maré Vive TV story was broadcast, the fake page disappeared from Facebook. A person with a fake profile added one of Maré Vive's administrators on Facebook, sending an apology via an inbox message ( and ).

Figure 4. On the right, the fake Maré Vive page, with references to Batman and, on the left, the real Maré Vive page with an illustration of Dona Orosina, one of Maré first residents, as its profile picture.

The Maré Vive page has now been active for six years, having attracted over 164 thousand followers. After achieving more maturity and internal organisations, the activists have now decided to have a rotating team of people publishing their posts and managing the interactions with favela residents who comment on the page. This is a way to ensure the people behind the page remain anonymous and that younger teams of activists are trained and prepared to take on the responsibilities, ensuring that the initiative does not die out if the more experienced activists are no longer able to remain involved (field notes, 15 May 2018).

Several elements are revealing about the fake page incident. Firstly, we could observe that mediactivists from marginalised communities must achieve visibility as the first step for any successful campaign or collective action because this is key for recognition (Brighenti, Citation2007). However, at the same time, we can argue that, for activists who are branded as enemies of society (Neumayer & Svensson, Citation2016), reaching such visibility will inevitably lead to a crisis. With Maré Vive, this crisis point occurred after the page had drawn attention to the arbitrary and violent character of many police operations regularly taking place in the favela. This then led to a virtual attack on the page. In order to defend themselves, the activists devised a strategy to reach even higher visibility by contacting a mainstream commercial TV network. This results in tension between the need to become visible and the risk of becoming vulnerable (Lokot, Citation2018) in times of polarisation on social media, which is summarised in this quote by another activist, who works as the Director of Museu da Maré, the first museum to be located within the borders of a favela in Brazil:

Visibility is key to clarifying what our true agendas are in contrast to the dominant views. However, at the same time, to become visible is to become vulnerable. As activists, we keep questioning ourselves. Do we need to grow this much? Do we need that much visibility? We really don't know what the balance is.

(Interview with Claudia Rose Ribeiro, 13/06/2018)

In our PAWA 254 case study, we discuss how researching visibility generated a crisis for another media activist Msingi Sasis, who works as a photographer creating images of Nairobi at night, and allows us to show the recurrent and cyclical path of visibility journeys.

4.2. PAWA 254 and Nairobi Noir: art-ivism to fight social inequalities

At the end of 2007, Kenya held its general elections with a contest for the top position between the incumbent, Mwai Kibaki, and the leader of the Orange Party, Raila Odinga. Claims that the vote was rigged stoked partisan tensions, leading to violence erupting across Kenya with more than 1100 people killed and over 500,000 people forced to flee their own homes. The violence pitted ethnic groups aligned with Kibaki and Odinga against each other, the Kikuyu and Kalenjin and Luo. During this time, the media played a significant part in fuelling these ethnic divisions through the construction and dissemination of narratives that set out inter-ethnic hostility (Wachanga, Citation2011). As Cheeseman (Citation2008) states,

the importance of the Kenya crisis for the African continent is not that Kenya may become “another Rwanda”, but that it reveals how fragile Africa's new multi-party systems may be when weak institutions, historical grievances, the normalisation of violence and a lack of elite consensus on the “rules of the game”, collide.

Noir originated as a part of social criticism in a very disguised manner, addressing issues which have been driven sometimes underground […] when you look at the dark side of a city, you are able to address a lot of social problems, in a way that people do not find offending, or overbearing, or very obvious. It does not come out as the traditional type of protest. […] you are able to address all these issues in an indirect way.

(Interview with Msingi Sasis, 26/08/2018)

Msingi's story shows the power of social media and the internet in protecting and supporting art-ivists and their cause but it also highlights the other side of the coin, the risks connected to visibility and the importance to one's online reputation.

(a). Going Public

Msingi's passion for Nairobi at night started when he was in high school (1999–2000) but it was only after attending a film school and going back to Nairobi in 2012 that he started photographing, for his own pleasure, the streets of Nairobi after sunset. One day in 2014, he edited one of these pictures and posted it on Facebook, achieving 500 ‘likes’ overnight. Msingi started editing and posting a picture every day, choosing from the hundreds of pictures he had taken, almost unconsciously, for two years. Those pictures resonated with the people and his popularity started to grow.

(b). Increasing Visibility

After a month of posting, he got a Facebook message from PAWA 254 inviting him to present his work at an exhibition held within the framework of the international event ‘African Metropolis’. Msingi created his website and the brand Nairobi Noir for the occasion. His pictures and his website became very popular and, four months later, he was interviewed by the international broadcaster, BBC world service[i] ().

(c). Critical Visibility Moment

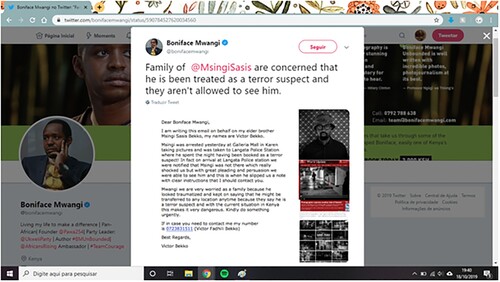

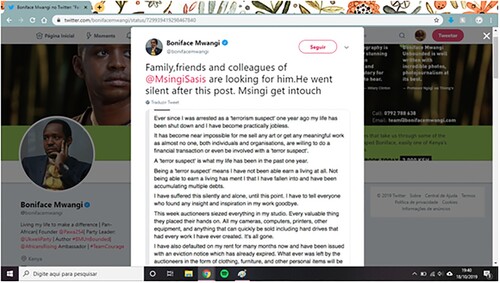

One night in April 2015, he went out at sunset, as usual, to start portraying the city and to take pictures of the Galleria Mall and some people noticed what he was doing. Kenya, especially Nairobi, was still shaken by the tragic terrorist attack at the Westgate shopping mall in 2013, in which 71 people died and more than 200 were wounded. People started to get suspicious and the rumour that he was attempting to plan acts of terrorism spread among them. The situation got serious and the crowd became violent and Msingi was at risk of being lynched by the mob. Eventually, the police were called and arrested him. From this description, it might appear less obvious that this critical visibility incident was caused by Msingi's mediated visibility. As it was acknowledged, people's and the police's initial suspicions were aroused by the context of the terrorist attacks. However, members of the organisation PAWA 254 have a history of persecution by the police and the Government. Boniface Mwangi, the organisation's founder, has been arrested several times. In 2016, after death threats were directed to his wife and children, Mwangi and his family were forced into a brief exile in the U.S (Interview with Boniface Mwangi, 27/08/2018). Therefore, it is not unreasonable to imply that activists associated with Mwangi and PAWA 254 have their social media accounts surveilled ().

(d). Managing the Critical Visibility Moment

After the Westgate shopping mall massacre and other terrorist attacks in the country, the Kenyan Government passed the Security Laws Amendment Act (December 2014) that gave the police the right to hold any terror suspect for 360 days without disclosing it to the public. Therefore, when Msingi's family went to look for him and the police did not confirm his arrest, they reached out to Boniface Mwangi, the founder of PAWA 254, for help.

(e). Overcoming the Critical Visibility Moment

PAWA 254 then started an online campaign on social media to denounce Msingi's arrest and to push for his release, which was achieved within 24 h.

After I was arrested, the support and encouragement I had was also very overwhelming, and I felt like, I cannot just stop because of a single arrest, because all these people, this work was resonating with a lot of people, and there were people telling me how this work had opened their eyes […].

(Interview with Msingi Sasis, 26/08/2018)

(f). (Re-) Increasing Visibility

After the arrest, he went back to photography, both for Nairobi Noir and in his portrait studio but clients started to turn him down, as the news of him being arrested as a terror suspect spread online and on social media. This generated another type of involuntary negative visibility (Meikle, Citation2016) for him, which then brought unintended consequences.

(g). Critical Visibility Moment

The artist did not get as much business as he used to and got into debt. He could not pay his rent and was kicked out of his flat, becoming homeless and jobless [1]. This was a very difficult moment in Msingi's life. Yet, again, the network of art-ivists gathering around PAWA 254 did not desert him and an online campaign was set up to find him and make visible the fact that he had been unfairly targeted ().

(h). Managing the Critical Visibility Moment

A few weeks later, still on the streets, Msingi met someone he knew and he learnt that people were looking for him online and on social media. He posted a request for help on Facebook, asking his audience to buy his prints to help him get back on his feet.

Overcoming the Critical Visibility Moment

Visibility would again help him regain recognition (Brighenti, Citation2007) for his artistic work whilst his community of followers, once again, supported him by buying his photos so that he could get back on track and set up a new photographic studio ().

In the two cases, activists embraced different strategies to overcome critical moments and manage their unintended visibility (Meikle, Citation2016). A key element in Nairobi Noir's visibility journey was its relationship with a strong hub of art-ivists in Kenya and with its well-known and respected founder, Boniface Mwangi. Boniface and his organisation, PAWA 254, were able to push the system when Msingi was arrested and use visibility to create enough pressure for him to be released. In Rio, Maré Vive's tactics (Lokot, Citation2018) entailed reaching out to mainstream media. They were able to neutralise the effect of the fake page that was ruining their reputation within the community and putting their lives in danger. Again, as DeBacker (Citation2019) suggested, we could see here how the control and recognition outcomes of visibility combined. Recognition turned into surveillance and control; because the page became widely recognised it was attacked before turning into recognition again. When the wide reach of mainstream media made visible the social relevance of the initiative, it prevented the attackers from causing further damage. Additionally, the activists realised that the critical moment generated by the page's fast achievement of visibility meant that the people behind this mediactivist initiative needed to remain invisible and protected. These decisions, which consisted of rotating the teams of activists and not associating their accounts with the management of the Facebook page (Interview, June 18th, 2019), fit into counter surveillance efforts. As Dencik et al. (Citation2016) suggested, these went beyond techno-legal solutions, such as using privacy enhancing tools, since these groups of activists are not part of a specialised constituency.

5. Concluding thoughts

These two case studies support the academic literature (Brighenti, Citation2007; De Backer, Citation2019; Dencik et al., Citation2016; Meikle, Citation2016; Uldam, Citation2017) in highlighting the ways in which visibility represents an ambiguous concept. De Backer (Citation2019) provides useful insights when he notes that the two outcomes of visibility – recognition and control – are heavily intertwined. They can happen simultaneously and one can transform into the other. In our study, whilst visibility was key for communicating activist causes, it also simultaneously translated into significant challenges. In this article, our aim was not to stress activists’ counter surveillance efforts as ways to mitigate the control outcome and to boost the recognition outcome of visibility.

Activists from marginalised communities or those who deal with issues of marginalisation often have to carry out their work with limited resources, living on a day-by-day basis and having little time to prepare for the future. This article aimed to offer them a tool, the Stepping into Visibility Model, for mapping out their visibility journeys, from increasing visibility to overcoming or succumbing to the critical moments. Adopting perspectives that highlight the experiences of two Global South countries, we can argue that these critical moments will inevitably happen. This stems from the ways in which marginalised activists’ experiences are shaped by their constant treatment as enemies of society. In these contexts, what is considered civil disobedience acquires different meanings. Legitimate causes, such as fighting against police brutality or using photography to portray social issues, are likely to be met with harsh punishments, including imprisonment or even execution. This confirms that when we move beyond Global North contexts, activists’ achieving visibility can have a much greater magnitude with equally significant consequences. By devising the Stepping into Visibility Model, we hope to have discussed counter surveillance efforts in ways that go beyond techno-legal solutionism (Dencik et al., Citation2016) and in periods outside that of large-scale protests (McCosker, Citation2015).

By delving into the Maré Vive and Nairobi Noir case studies, we learned lessons about how these two initiatives managed to overcome their unintended visibility critical moments. In the first case, this entailed a pragmatic engagement with commercial mainstream media, challenging their frames of silence (Lokot, Citation2018) in relation to the favelas. By resorting to mainstream media assistance, the Brazilan group recognises the affordances of hybrid media ecologies (Treré, Citation2018) and how ‘old’/’new’ media logics are in play for media activist tactics. In the second case, social media visibility, in its recognition generating capacity, was used to mobilise a network of support for Msingi Sasis. It is hoped that these experiences can be shared with other activists in similar contexts. Here, it is worth noting that the visibility journeys of the activists are not always linear as one might infer from the graphic representations included in this article. In fact, this depends on the visibility strategies employed by the groups as they might, for instance, choose to go ‘invisible’ to mitigate a crisis for a period of time, deleting a page or stopping its online activities.

However, it is acknowledged that this model presents limitations. We do not claim to predict the future of activist initiatives based on a small number of cases. Therefore, the next step is to conduct further research on the application of this model to a larger number of cases in Global South (and perhaps Global North) countries. With consolidation of digital technologies, we hope to have demonstrated that visibility has acquired context-specific meanings. Whilst the phenomenon of an activist group reaching high visibility levels is certainly not new, the dynamics of how gains for social causes are quickly met with regressive responses and political backlash need to be examined more carefully. In times of algorithmic oppression and surveillance, we hope to have offered a contribution to how marginalised communities can be better informed when they attain visibility, ensuring that they carry on doing important work for social change and justice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Isabella Rega

Isabella Rega is Associate Professor in Digital Media for Social Change in the Faculty of Media and Communication, Bournemouth University, and Global Research Director the Jesuit Worldwide Learning: Higher Education at the Margins (JWL) initiative. At BU she also acts as Deputy Head of CEMP – Centre of Excellence in Media Practice, Head of its Media and Digital Literacies Research Cluster and member of the Civic Media Hub. As Global Research Director at JWL she leads the research efforts of the organisation on the impact of Higher Education on marginalised communities around the globe and on the effectiveness of digital technologies to deliver high-quality educational experiences. Isabella has extensive experience working in ICT for development projects focusing on eLearning and access issues in South Africa, Brazil and Mozambique. She has also worked in telecentres, as researcher and instructor, in Jamaica, Burkina Faso, Benin, Guinea and South Africa, and collaborated as an online teacher for a distance learning university in Colombia.

Andrea Medrado

Andrea Medrado is a Lecturer at the School of Media and Communication, University of Westminster, teaching media theory and practice modules for undergraduate and postgraduate students. Prior to joining Westminster in September 2020, she worked as a Tenured Assistant Professor in the Department of Social Communication and at the Postgraduate Programme in Media and Everyday Life of Federal Fluminense University (UFF) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In July 2020, Andrea was elected Vice President of the International Association for Media and Communication Research (IAMCR) and, prior to that, she was the Co-Chair for the association’s Community Communication and Alternative Media Section for four years (2016–2020). Her research analyses the ways in which digital activists and art-ivists from marginalised communities in Global South countries (particularly Brazil and Kenya) can exchange experiences and lessons, promoting an exploration of mutuality between them. She is particularly interested in how communication and activist media practices deepen people’s consciousness and become a tool for movement building. Additionally, she investigates how activists and art-ivists balance their need for visibility with an increasing vulnerability in a scenario dominated by private internet companies.

References

- Askanius, T., & Uldam, J. (2011). Online social media for radical politics: Climate change activism on YouTube. International Journal of Electronic Governance, 4(1–2), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEG.2011.041708

- Brighenti, A. (2007). Visibility: A category for the social sciences. Current Sociology, 55(3), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392107076079

- Brighenti, A. M. (2010). Visibility in social theory and social research. Springer.

- Bucher, T. (2012). Want to be on the top? Algorithmic power and the threat of invisibility on facebook. New Media & Society, 14(7), 1164–1180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812440159

- Callus, P. (2018). The rise of Kenyan political animation: Tactics of subversion. In P. Limb & O. Tejumola (Eds.), Taking African cartoons seriously: Politics, satire, and culture (pp. 71–98). Michigan State University Press.

- Cheeseman, N. (2008). The Kenyan elections of 2007: An introduction. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 2(2), 166–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531050802058286

- De Backer, M. (2019). Regimes of visibility: Hanging out in Brussels’ public spaces. Space and Culture, 22(3), 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218773292

- Degenhard, J. (2021). Social media users in Africa 2020, by country. Statista. https://www-statista-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/forecasts/1169089/social-media-users-in-africa-by-country

- Dencik, L., Hintz, A., & Cable, J. (2016). Towards data justice? The ambiguity of anti-surveillance resistance in political activism. Big Data & Society, 3(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716679678.

- de Sousa Santos, B. (2015). Epistemologies of the south: Justice against Epistemicide. Routledge.

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Penguin.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Adline de Gruyter.

- Kunst, A. (2020). Social media usage by platform type in Kenya 2020. https://www-statista-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/forecasts/1191025/social-media-usage-by-platform-type-in-kenya

- Lisboa, V. (2014). Federal Troops Occupy Slum Communities in Complexo da Maré. Agência Brasil April 7th.

- Lokot, T. (2018). Be safe or be seen? How Russian activists negotiate visibility and security in online resistance practices. Surveillance & Society, 16(3), 332–346. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v16i3.6967

- Mann, S. (2004). “Sousveillance” inverse surveillance in multimedia imaging. In proceedings of the 12th annual ACM international conference on multimedia (pp. 620-627). October 10-16, 2004.

- Marques, ÂCS, & Nogueira, E. C. D. (2012). Estratégias de visibilidade utilizadas por movimentos sociais na internet. Comunicação Midiática, 7(2), 138–161.

- McCosker, A. (2015). Social media activism at the margins: Managing visibility, voice and vitality affects. Social Media+ Society, 1(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115605860

- McCurdy, P., & Uldam, J. (2014). Connecting participant observation positions: Toward a reflexive framework for studying social movements. Field Methods, 26(1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X13500448

- Meikle, G. (2016). Social media: Communication, sharing and visibility. Routledge.

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Revised and Expanded from” Case Study Research in Education..” Jossey-Bass Publishers, 350 Sansome St, San Francisco, CA 94104.

- Milan, S., & Treré, E. (2019). Big data from the South (s): beyond data universalism. Television & New Media, 20(4), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419837739

- Mouffe, C. (2005). The return of the political (Vol. 8). Verso.

- Navarro, J. G. (2020). Social media usage in Brazil – Statistics & facts. https://www-statista-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/topics/6949/social-media-usage-in-brazil/

- Neumayer, C., & Svensson, J. (2016). Activism and radical politics in the digital age: Towards a typology. Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies, 22(2), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856514553395

- Pearce, K. E., Vitak, J., & Barta, K. (2018). Socially mediated visibility: Friendship and dissent in authoritarian Azerbaijan. International Journal of Communication, 12, 1310–1331. 1932–8036/20180005

- Treré, E. (2018). Hybrid media activism: Ecologies, imaginaries, algorithms. Routledge.

- Uldam, J. (2018). Social media visibility: Challenges to activism. Media, Culture & Society, 40(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717704997

- Villalobos, C. (2019). Decolonizing Security and (Re) Imagining Safety in Rio de Janeiro and Nairobi [Master’s Thesis]. Paris School of International Affairs (PSIA).

- Wachanga, D. N. (2011). Kenya’s indigenous radio stations and their use of metaphors in the 2007 election violence. Journal of African Media Studies, 3(1), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1386/jams.3.1.109_1