ABSTRACT

Many liberal democracies have witnessed the rise of radical right parties and movements that threaten liberal values of tolerance and inclusion. Extremist movement factions may promote inflammatory ideas that engage broader publics, but party leaders face dilemmas of endorsing content from extremist origins. However, when that content is shared over larger intermediary networks of aligned supporters and media sites, it may become laundered or disconnected from its original sources so that parties can play it back as official communication. With a dynamic network analysis and various-time series analysis we tracked content flows from the German version of a global far-right anti-immigration campaign across different media platforms, including YouTube, Twitter, and collections of far-right and mainstream media sites. The analysis shows how content from the small extremist Identitarian Movement spread over expanding networks of low-level activists of the Alternative for Germany party and far-right alternative media sites. That network bridging enabled party leadership to launder the source of the content and roll out its own version of the campaign. As a result, national attention became directed to extremist ideas.

Far-right extremism has become disruptive in democratic nations as different as Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Australia and the United States. Different countries have experienced protests on similar issues, from climate change, abortion, and immigration, to wearing facemasks during the Covid-19 pandemic. Growing radical and extreme right communities use platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Telegram to spread disinformation, develop conspiracies, and organize protests (Guhl & Davey, Citation2020; Guhl et al., Citation2020). Many of these movements have affiliated with political parties, resulting in increased radical right participation in elections (Bennett, Segerberg, and Knüpfer, Citation2018; Caiani & Císař, Citation2018; Mudde, Citation2019). As a result, far-right representation has grown in legislatures and governments in many Western democracies, e.g., Italy, Austria, Germany, Sweden, and Brazil. In the United States, Donald Trump broadened the radical Tea Party faction of the Republicans by inviting white nationalists, QAnon conspiracy networks and armed militia groups into his Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement. Those factions and many of their elected representatives refused to accept Trump’s defeat in the 2020 election, culminating in an angry MAGA mob storming the US Capitol on January 6, 2021 while the election of Joe Biden was being certified inside. Close connections between movements and parties, and the emergence of protest parties or movement parties can be observed in many countries (Borbáth & Hutter, Citation2021; Pirro, Citation2019).

The potential of far-right extremism to undermine liberal values and threaten the legal foundations of democracies has resulted in vigorous national discussions of how to protect democratic culture and institutions, when they hollow out public institutions, demonize opponents, attacke the traditional news media, and display other indicators of ‘how democracies die’ according to Levitsky and Ziblatt (Citation2018).

Even with developed standards and surveillance, it is often difficult to distinguish dangerous communication from free speech, particularly when those promoting it are elected by citizens who support their ideas. Moreover, unlike conventional coordination of party and movement activities via meetings, conferences or conventions, the dispersed organizational properties of networks can make it difficult to apply traditional definitions of coordinated action. In particular, when ideas from even small extremist sources travel over larger and less extreme intermediary networks, it is difficult to show that formal coordination of harmful activities actually occurred. Such concerns suggest the need for a research agenda that is applicable to many democracies these days: How do parties on the far-right take up ideas from extremist factions online? In particular, do such ideas travel over (and become ‘laundered’ by) larger networks of aligned media sites and activist supporters that serve as intermediaries between extremists and elected parties?

In order to address these and other questions, we set up a monitoring system of the German far-right media ecology to track content flows from multiple platforms to see if and how ideas traveled into party networks and on into mainstream society. In addition to monitoring German mainstream media (MSM), we tracked and collected communication flows among a variety of far-right groups, including various factions, media sites, and movement networks associated with the populist radical right (Mudde, Citation2007) party, Alternative for Germany (hereafter, Alternative für Deutschland, or AfD). The AfD was founded in 2013 as a Eurosceptic and more neoliberal economic alternative to the Christian Democrats (CDU), but it soon became a political home for white nationalist groups such as the anti-immigrant protest network Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West (PEGIDA). Also drawn to the party were even more extreme groups such as the Identitarians, who figure prominently in our case below (Arzheimer & Berning, Citation2019; Heinze & Weisskircher, Citation2021). These and other radical AfD supporter factions practiced sophisticated networking on digital media platforms (Fuchs & Holnburger, Citation2019; Stier et al., Citation2017). At the same time, influential members of the party were concerned about alienating less-radical voters at a time when the party was making impressive electoral gains. However, as the examples of MAGA in the US and our case below show, it is difficult for parties to sever ties with extremist groups and ideas when they have become embedded in broad supporter networks. As a result, those parties, and the public positions and debates they generate, may become pulled farther to the right and risk becoming captive to their extremist fringe.

When extremists become popular: what are parties to do?

Our study focuses on an anti-immigration campaign launched by the small but disruptive Identitarian Movement. Identitarianism is an ideological pastiche drawing on French (Alain de Benoist), German (Carl Schmitt) and Italian (Julius Evola) fascist and ethnic nationalist thinkers. Kindred groups now exist in many democracies, e.g., Sweden, Austria, Italy, the US, Australia and New Zealand, where links were established between the shooter in the 2019 Christchurch mosque massacre and Identitarian leader Martin Sellner.Footnote1 In 2018 Austrian state prosecutors accused Sellner’s Generation Identity movement a criminal organization but were unable to obtain convictions on a range of charges. In 2021, the French government banned Generation Identity. Here we label the Identitarians as a far-right extremist movement not only based on the assessment of state authorities, but also following Mudde’s (Citation2007) distinction between the radical right and the extreme right – that is not only nationalist, xenophobe, and authoritarian, but also anti-democratic (p. 24).

Party uptake of such ideas is challenging. Not only did the AfD pledge in 2016 not to cooperate with the Identitarians and other white nationalist groups, but in 2017, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV) placed the Identitarians ‘under suspicion’ of being extremist, and by 2019 they were upgraded to the category of a ‘verified extreme right’ movement with an ideology against the liberal democratic constitution (BfV, Citation2020). The BfV concluded that the group ‘ultimately aims to exclude people of non-European origin from democratic participation and to discriminate against them in a way that violates their human dignity,’ (BfV, Citation2020, p. 108)Footnote2, and the chief of the BfV accused them of ‘intellectual arson.’

These prohibitions notwithstanding, we were able to track a campaign that embodied the above basis for classification as a democratic threat as it traveled from its extremist origins to reappear within a few weeks as a self-proclaimed independent AfD campaign using the same frames.

How did this happen, particularly at a time when both the Identitarians and several AfD factions were under surveillance for unconstitutional activities? Following the introduction of our case in the next section, we review key theoretical understandings about networked organization and the spread of ideas, from which we develop two broad hypotheses about the spread of dangerous ideas, along with four specific research questions that guide the empirical analysis.

The case of the ‘Migrationspakt Stoppen’ campaign

The United Nations Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM)Footnote3 was little more than an effort to secure agreement that the world assembly should pay more attention to the problems of massive migration due to war, economic collapse and climate change. In other times, the agreement might have faced the common criticism that UN global compacts are often weak and ineffective due to political compromise, voluntary compliance and lack of sanctions. However, when the GCM moved onto the UN agenda for debate in 2018, international far-right media and political actors began to brand it as an assault on national sovereignty (Montgomery, Citation2018a) and a ‘plan to promote global mass migration’ (Montgomery, Citation2018b). Debates about ratifying the GCM quickly spread through governments in various countries, fueled by YouTube videos and related disinformation on other platforms. National debates were ‘trolled’ by ‘a coordinated online campaign by far-right activists’ who spread ‘large-scale distorted interpretations and misinformation’ (Cerulus & Schaart, Citation2019). This connects to a study by Julia Rone (Citation2020) showing how far-right alternative media acted as ‘indignation mobilization mechanism’ in the protest against the GCM, arguing that ‘these media have gone beyond (dis)informing and have actively mobilized and channeled indignation through petitioning and protest organization’ (p.1).

The time frame for our study is roughly bounded by the release of a draft UN document on 13 July 2018 and a final version that was approved by 164 nations on December 10, 2018 in Morocco. In order to capture the full range of media attention to the issue, we gathered data from 11 July – 15 December. The countries that eventually voted against the GCM included the US, Hungary, Israel, the Czech Republic, and Poland. An additional 12 abstained, including Australia, Austria, Chile, Italy, Romania and Switzerland. In Belgium, the government coalition collapsed over the issue, and conflicts in a number of other countries led them to simply not attend the meeting. Germany eventually signed the agreement.

Both policymakers and mainstream journalists seemed to be caught off guard by the sudden organized opposition from AfD national leadership. A report by the main German public broadcaster ARD reported that AfD leadership was initially hesitant to adopt the issue, deeming it too complex and unimportant. The report cited an incident in May, 2018, following a UN invitation to German MPs to come to New York for more information about the GCM. A high-ranking AfD parliamentarian declined a travel request submitted by a fellow MP of a different party, claiming he saw ‘no use’ for the trip (Stein, Citation2018). And so, aside from a minor parliamentary interpellation (a question to the government for the record) in April 2018, the AfD did not mobilize any serious opposition to the GCM before October. The conventional wisdom in the press was that it was only after right-wing governments in Hungary and Austria voiced their opposition that the campaign against the GCM turned out to be a viral hit. Our methods enabled us to take a deeper look and follow the Identitarian campaign as it passed seamlessly from a small extremist fringe and flowed through several much larger intermediary networks of party supporters until it was taken up as an official AfD campaign – all within a matter of weeks. With this we do not argue that all protest against migration were per se extremist, but the debate about the GCM enables us to trace how content from extremist actors (here the Identitarian Movement and parts of AfD) becomes laundered and enters mainstream public discourse and institutions.

Intermediary networks and issue uptake: a theoretical framework

Intermediary networks may enable actors (in this case, party leaders) to selectively take up sensitive issues while distancing themselves from possibly unsavory sources of content. This entails several processes that have been established in prior research and provide theoretical foundations for our general hypotheses and related research questions: 1) network monitoring by political organizations; 2) degree of alignment among intermediary networks; 3) the presence of hyperactive or ‘superspreader’ accounts instrumental in amplifying aligned content; which, if these conditions are present, can result in 4) networked framing and agenda setting.

Network monitoring. It is by now routine for organizations, from businesses to political parties, to monitor their media ecologies to assess how their communications are being received, what threats may be developing, and what opportunities exist for activating followers. Such monitoring and engagement with information flows over intermediary networks is similar to what Bruns (Citation2005) has termed ‘gatewatching’ in the production of open-source news, and Karpf (Citation2016) has called ‘analytic activism’ based on ‘digital listening.’

Network alignment. Since network dynamics are often not fully controllable by those who seek the attention of larger audiences, a set of enabling conditions can make or break the spread of content. Of particular importance is the size and alignment of peripheral and intermediary networks. Provisionally we define peripheral networks as distributing content in snowball patterns out from a core set of actors, while intermediary networks operate as strategic connectors between otherwise separated networks.

Much large-scale networked communication results in dissonant public spheres (Pfetsch, Citation2018; Bennett & Pfetsch, Citation2018) which are unedited environments in which ‘social media appear connected to epistemic failures’ (Bimber & Gil de Zúñiga, Citation2020, p. 711). Some of this dissonance can be seen when hostile agents enter a networked protest ecology with the intent to disrupt, as when the German #MeToo movement was attacked by Twitter accounts spreading anti-feminist, sexist and racist content (Martini, Citation2020). However, more coherent patterns of networked content spread also occur. For example, a study of movement-to-society issue flows in the Occupy Wall Street protests showed that peripheral networks of celebrities, politicians and sympathetic journalists were supportive of the protests. It turned out that the peripheral networks with the largest followings selectively spread ideas from (and into) the crowd that were already in broader public discussion, such as reducing economic inequality. By contrast, core protest leaders focused on communicating more radical ideas about reforming corrupt democratic institutions and financial systems. As a result, most mainstream media accounts and various measures of public attention to Occupy pointed to inequality as the main theme of the protests (Bennett, Segerberg, and Yang, Citation2018). In contrast to the selective snowball spread of content by peripheral networks, our case illustrates how more politically aligned intermediary movement networks pass similar content between movement and party actors that could not endorse each other or communicate directly.

The role of superspreaders. In networked online organization, much depends on the few who do most of the work. This has been shown in studies of Wikipedia and many other peer production communities (Shaw & Hill, Citation2014). This generalization also applies to many online campaigns, particularly among the radical right and conspiracy legends such as QAnon (Townsend, Citation2020; Zadrozny & Collins, Citation2018). Similar patterns also hold for protest networks, whether left or right, in which ‘only a minority of users bring online networks together and facilitate global dissemination in protest communication’ (González-Bailón & Wang, Citation2016, p. 96). A study of online organization in the Occupy protests found that a tiny minority of hyperactive accounts spread the content that was most highly shared by others in the crowd (Bennett et al., Citation2014). These generalizations are also supported by research on how parties and followers communicate on Facebook. Since the vast majority of visitors to party sites seldom interact with postings, statistical outlier detection identified users leaving more than three comments or likes as hyperactive. This small number of accounts (5.3%) were observed to: ‘participate in discussions differently from the rest, and they like different content. Moreover, they become opinion leaders, as their comments become more popular than these of the normal users’ (Papakyriakopoulos et al., Citation2019, p. 6; see also Ross et al., Citation2019).

Networked framing and agenda setting. We understand the above processes to be interrelated, and predictive of the degree of coherence or noise in content traveling over multiple networks. We propose that when intermediary networks are aligned, or coordinated in the spread of particular content, and when such alignment is monitored by an organization seeking ways to build commitment among its followers, there is a high likelihood that networked framing (Meraz & Papacharissi, Citation2013) and networked agenda-setting (Guo & McCombs, Citation2016) may occur. Framing here refers to adopting widely shared representations of an issue, and agenda setting implies party position-taking based on that framing.

We derived two broad assumptions linking these general theoretical propositions to our specific case. We expected that the original Identitarian campaign was spread by well-aligned and increasingly large intermediary networks of party supporters that drew the attention of leading AfD politicians to an issue and a framing that activated its voter base. Moreover, we expected that those networked content flows distanced the campaign from its extremist origins, enabling the party to claim ownership of the issue and use essentially the same framing as the extremists.

Research questions

Following from the above theoretical foundations and related assumptions, we developed four specific research questions:

RQ1: What intermediary network activity occurred following the launch of the Identitarian campaign?

RQ2: When did the AfD party campaign emerge in relation the Identitarian campaign, and how closely did it mirror the Identitarian version?

RQ3: What changes (if any) occurred in intermediary network activity following AfD uptake of the campaign?

RQ4: How and when did mass media cover the issue in relation to the above stages of attention sequencing?

Methods and data

Since networked organization typically entails multiple platforms and the connections and content flows across them, we collected data from YouTube channels, far-right news and information sites (RNIS), the AfD party site and affiliated party news sites, and Twitter accounts categorized by different actor types over the period of study. We searched all platforms during the period of July-December 2018 for the key terms ‘Migrationspakt’ and ‘Migrationspakt Stoppen,’ which was the high-level frame for both Identitarian and AfD campaigns. The term ‘Migrationspakt’ is not a common phrase in the German language and was explicitly connected to this political campaign.

As part of our far-right monitoring project, we created and then gathered data from the Media Cloud collections ‘RNIS-DEU’ and ‘RNIS-AUT’, which features a total of 21 German language far-right news and information sites.Footnote4 These sites were selected based on multiple criteria, including their political promotion of various far-right causes, claims of being alternatives to mass media, and their frequent mimicking of ‘news’ formats through regular and timely content (Heft et al., Citation2020). When applied to mentions of the GCM, the most prolific of these sites included Journalistenwatch, PI-News, and Politikstube. We also queried a collection of German mass media which included the leading German print publications: Spiegel, Bild, FAZ, Tagesspiegel, Welt, and Zeit. We gathered URLs to both far-right and mainstream stories which featured the key terms and then scraped text content as well as featured hyperlinks via the Python library ‘Newspaper3k’. We also collected all the posts mentioning the key terms from the AfD party website as well as the party’s own media outlet ‘AfD Kompakt’. The ‘Migrationspakt’ was also actively discussed on German language YouTube. We employed the R package ‘tuber,’ which enabled us to query the YouTube API (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tuber/index.html). We retrieved all the videos, mentioning the term ‘Migrationspakt’ in the titles or descriptions, for the same time period. In total, we gathered information on 1,606 videos from a total of 681 channels.

Many of the results reported here came from Twitter. Although Twitter is not used by a large part of the German population (13%, Reuters Digital News Report, Citation2020), it plays an important role in spreading information among elites, journalists, bloggers, news junkies, and activists, and offers a window on how networks from those communities may interact and change. We collected all tweets, retweets and replies containing the term ‘Migrationspakt’ using Crimson Hexagon (now owned by Brandwatch). Download limitations imposed by Crimson Hexagon resulted in random samples of 10,000 tweets per day for the period of 31 October – 15 December 2018 when volumes of mass media and public engagement on Twitter were greater. In total, for the period of 11 July – 15 December 2018 we collected 506,079 tweets, including 69,361 original tweets, 410,276 retweets and 26,442 replies from 43,579 unique Twitter accounts (replies were not included in the analysis). This represents approximately 60% of all Twitter traffic involving the search terms during the period investigated.

In the next step, we classified the YouTube channels and Twitter accounts to distinguish between different actor types. For YouTube, these channels were manually classified based on their names and descriptions by a team of human coders. Some of the channels were easily identifiable as official media or political accounts. Others featured hyperlinks to websites which the human coders followed and evaluated. The coding of YouTube and Media Cloud data corresponded to the following categories: national and regional newspapers; public and private broadcasting; far-right news sites and channels; Identitarian Movement actors; and low and high level AfD actors, including the federal and parliamentary party’s accounts as well as their official party newspaper. In total, 20 YouTube channels were coded as far-right news sites or channels. A total of 52 channels were classified as accounts clearly affiliated with the AfD.

Next, all Twitter accounts were coded using the same categories of actor types. The accounts were coded in a semi-automated process based on dictionaries with human coders filtering for key terms in account names and manually checking the results. In total, 112 accounts (1,236 tweets) were coded as mass media and 23 accounts (841 tweets) were coded as far-right news and information (RNS) sites. A total of 224 accounts with 3,350 tweets were coded as ‘low level AfD’ based on using the term AfD either in their Twitter name or in their profile. These were primarily local party activists or state and local elected representatives. Four accounts were categorized as ‘high level AfD’ @AfD, @AfDimBundestag, @AfDKompakt, @Alice_Weidel, one of the leaders of the parliamentary group in the Bundestag, with a combined total of 263 tweets. All accounts claiming affiliation with the Identitarian Movement were grouped together (N = 29, 837 tweets). The category of superspreaders was created from the top 100 most active accounts in the overall network (73,663 tweets). In Appendix A we provide a list of all Twitter handles and the top retweets for all actor types. All remaining nodes (N = 42,258) can be considered as the actively involved audience of the campaign against the GCM.

We tested all accounts for automation using Botometer – a widely used bot detection tool based on machine learning – via its API (Davis et al., Citation2016). The threshold for discriminating between automated and non-automated accounts was set at 0.75 (Keller & Klinger, Citation2020), resulting in 5.9% of the accounts showing automated behavior, sending only 3.4% of all tweets in the data. The number was similarly small among the superspreaders (5.1% automated, 4.9% of tweets).

To trace and visualize the network dynamics of the online discourse on the migration pact, we used Python to further process the data and applied the open-source software Gephi to model the dynamic network. In contrast to static network analysis that freezes networking activities at one point in time in one graph, dynamic network analysis enables researchers to catch the changing moments of the network development. To reveal who and whose messages received most of the attention in shaping discourse on the migration pact, we used the retweets to build our dynamic network. We colored nodes based on their actor type categories and the edges according to their information source (i.e., the edge inherited the color of the actor whose tweet was retweeted). Then we sized the node according to their indegree centrality, which highlights the nodes of the most retweeted actors and represents node size increases as the network evolves. To spatialize the daily development of the network, we used ForceAtlas2 (Jacomy et al., Citation2014).Footnote5 A screencast of the full dynamic network as it evolved over time has been posted here: https://youtu.be/mN74-qF5aaQ. This visualization shows the general pattern of network handoffs suggested in our hypotheses, but it is not sensitive enough for answering the research questions. The following section presents the fine-grained findings tied to those questions.

Results

Prior to the launch of the Identitarian campaign on 16 September 2018 there was only sporadic social media activity trying to promote attention to the GCM. Although AfD had registered a parliamentary question about the issue in April 2018, there was little follow-up activity. A few local and regional AfD accounts tweeted about it, as well a few mentions in radical right news and information sites, most notably Epoch Times and Russia Today for Germany. A one-time tweet by the co-leader of the AfD parliamentary faction, Alice Weidel, on 14 September 2018 indicated opposition to the GCM, but the other party leadership still found the topic too complex and distant for a party campaign (Sternberg, Citation2019).

Our analyses found that the issue became a hit with AfD leadership only after the grassroots Identitarian campaign spread rapidly through networks of low level AfD supporters, superspreaders, and far-right media sites until the magnitude and composition of those network ‘handoffs’ laundered the issue of its extremist origins and enabled the national party to claim the campaign as its own. We review how this process unfolded by presenting findings from our four research questions.

RQ1: What intermediary network activity occurred following the launch of the Identitarian campaign?

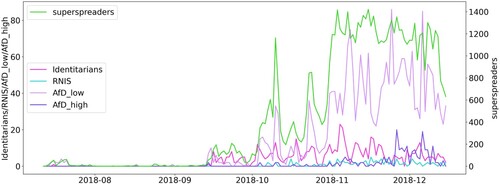

Identitarian leader Martin Sellner entered the stage on 16 September when he posted a YouTube video urging Germany, Austria and Switzerland to stop the ‘Migrationspakt.’Footnote6 The opening campaign video called for an ‘information war’ to start ‘spreading fire’ to stop ‘the demise of the European people’ and calling the GCM a ‘death sentence for the nation state’ (Cerulus & Schaart, Citation2019). This video also launched a petition campaign with a slogan ‘Migrationspakt Stoppen’, along with a website of the same name, a Twitter account (@migrationspakt), Telegram channels, and buttons, stickers, posters, flyers and postcards ready for download. The campaign was an instant success. Within one day, @migrationspakt became the most-retweeted account in the network. As shown in , the retweet network of intermediaries spiked immediately after the launch of the campaign in mid-September. Both the superspreaders and low-level party accounts amplified the campaign, quickly surpassing the volume of Identitarian activity.

Figure 1. Retweet activity of far-right networks following different phases of the Migrationspakt Stoppen campaign. Scales indicate number of retweets per day. N = 410,276 retweets for entire time period.

Note: due to the much higher retweet volumes of the 100 superspreader accounts, they are shown on a different scale on the right to provide perspective.

The superspreaders were active immediately at the launch of the Identitarian campaign and even more active after the AfD picked up the issue in October. Although they represented a mere 0.27% of nodes in the overall network, superspreaders account for 21% of all interactions. Superspreaders not only amplified messages from other actors through massive retweeting, but they also bridged the other networks by retweeting their most prominent nodes. In addition, 60 of the superspreaders get retweeted themselves (accounting to 1.10% of RT network).

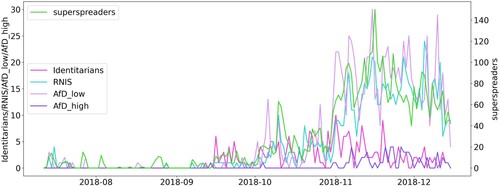

The role of far-right media (RNIS) is better shown in original tweets than retweets, suggesting a different balance between ‘reporting’ and campaigning’ that reflects the nature of those sites as information services. shows that RNIS began covering the Identitarian campaign from the beginning, already in July. The volume of RNIS tweets with the term ‘Migrationspakt’ clearly picks up after the AfD campaign begins in October and becomes even higher during the increased parliamentary activity in December. As shows, the RNIS rivals the original tweet activity of the low-level party activists and the superspreaders, suggesting that the far-right media played a dual role, initially as intermediaries bridging the extremist faction and the party, and later as amplifiers of the party.

RQ2: When did the AfD party campaign emerge in relation the Identitarian campaign, and how closely did it mirror the extremist version?

By early October, the AfD party website launched a mirror image ‘Migrationspakt Stoppen’ campaign, with a page of stickers and banners that followers could download.Footnote7 There was no reference to the Identitarian campaign either on the AfD site or in other party communication. On 1 November the AfD continued its mirror image campaign by registering a formal parliamentary petition calling for an official government inquiry.Footnote8 When the petition was submitted, the co-leader of the AfD parliamentary faction, Alexander Gauland claimed: ‘They want to transform our nation state into settlement territory!’ (AfD-Fraktion im Deutschen Bundestag, Citation2018). Within a few weeks, the petition gained over 100,000 citizen signatures, quickly reaching the level that required a government response.

Figure 2. Total original tweets per day of the five actor networks, showing higher tweet than retweet levels by far-right media (RNIS). N = 69,361.

Note: due to the much higher tweet volumes of the 69 superspreader accounts, they are shown on a different scale on the right to provide perspective.

In answering the second part of the question, we found that the AfD campaign was a very close copy of the Identitarian version, only with more professional packaging. For example, the URL for the Identitarian campaign website was migrationspakt-stoppen.info, which the AfD modified only slightly by changing the ‘.info’ to ‘.de’. The text on the Identitarian campaign site began and ended with an ominous warning that ‘the clock is ticking,’ pointing to the UN ratification deadline in December. The AfD site also used the image of a ticking clock, with the hands pointing to ‘five minutes to twelve.’ The issue framing on both sites was strikingly similar, casting the GCM as a deliberate attack on national sovereignty by unelected, illegitimate foreign officials. Both texts reference ‘our’ or ‘Germany’s’ welfare state systems as the target for an unmitigated influx of mass migration. The Identitarian homepage made explicit mention of ‘replacement migration,’ drawing on the radical right’s trope of planned replacement of white European populations. The AfD site even expanded on that core dogma by demanding that ‘true Europeans must prevent the replacement of their populations by members of completely foreign cultures.’ The party campaign added a few more bits of disinformation by claiming the GCM would entitle immigrants to the same access to welfare programs as domestic populations and allow them to maintain their own legal and cultural customs such as Sharia law (a popular Islamophobic trope on the global right). Paraphrasing the Identitarian campaign, the AfD called on activists to ‘voice their opinion’ as a ‘sign of protest (…) against further unbridled immigration and for the preservation of our homeland.’ With the launch of its own parliamentary petition in November, the AfD claimed exclusive issue ownership when party leader Joerg Meuthen and others falsely claimed that it was the AfD, and only the AfD who started a debate about, and opposition to the GCM (Süddeutsche Zeitung, Citation2018).

RQ3: What changes (if any) occurred in intermediate network activity following official AfD uptake of campaign?

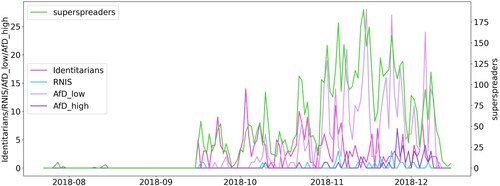

Activity levels of all three intermediary networks (RNIS, superspreaders and low level AfD activists) grew even more rapidly following the launch of the AfD campaign. shows the sums of tweets and retweets using the term ‘stoppen’ (as a unique tracking term for the campaign) for all of the actor groups. Twitter activity levels of two of the three intermediary networks escalated to even higher levels following the introduction of the AfD parliamentary petition. We note that the RNIS engaged in far lower activity levels promoting the ‘stoppen’ campaign than the other two intermediaries, perhaps reflecting their role as political information rather than campaign platforms.

Figure 3. Volume of combined ‘migrationspakt’ tweets and retweets containing the term ‘stoppen’ in different intermediary networks N = 34,769.

The resulting amplification of party issue ownership and promotion of the mirroring ‘Stoppen’ campaign was impressive. The overall network grew quickly to 23% of its final size during the launch of the AfD campaign in early October and nearly doubled again following the launch of the parliamentary petition on 1 November. By the time the official petition crossed the signature threshold of 100,000 in late November, the network was in the process of doubling again as mainstream media coverage helped spread the issue to even broader publics.

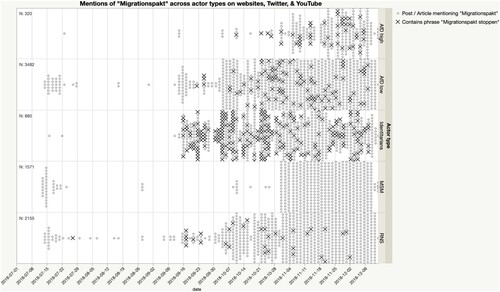

RQ4: How and when did mass media cover the issue in relation to the above stages of attention sequencing?

We expected the mass media to pick up the story after the AfD introduced the petition campaign in parliament, and it did. However, we did not expect either the volume of stories or such rapid growth in the attention network through retweeting stories in mainstream media feeds (see our dynamic network video: https://youtu.be/mN74-qF5aaQ). The news story became so prominent because the popularity of the AfD campaign triggered the public flareup of longstanding tension between the Christian Democrats and their Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union (CSU). Much of the resulting news coverage featured the AfD as a source of the conflict due to winning increasing vote share in CSU territory over the immigration issue. The most-retweeted post in the entire dataset originated from conservative national newspaper Die Welt (Citation2018) pointing to the puzzling and sudden turnaround after the party`s parliamentary faction did not care about the issue for most of the year. We show as a summary of the networked handoffs over multiple platforms, as the Migrationspakt (and the Stoppen campaign) moved from relatively obscure movement origins through larger, well-aligned networks, and finally spilled into the mass media – but clearly without the ‘Stoppen’ frame. Looking at multiple platforms makes it even clearer that the cascading engagement of intermediary networks prompted high level party uptake, as AfD low level accounts, Identitarians and RNIS all preceded and potentially triggered the AfD high level activity. In addition, the absence of the key campaign term ‘stoppen’ in the mass media suggests that the press coverage was less focused on the AfD campaign itself than on the broader conflict that the campaign rekindled over immigration.

Figure 4. Multi-platform representation of the ‘Migrationspakt’ issue and the ‘Stoppen’ campaign. Ns refer to number of posts across multiple platforms, including: YouTube, Twitter, and collections of far-right and mainstream media sites.

Note: superspreader activity not included here due to the enormous scale differences as represented in .

Discussion

Campaigns such as the GCM protest do not emerge linearly as continuously growing networks. Our analysis shows that different platforms and intersecting networks connected larger and more credible segments of the populist radical right party with the extremist movement. Those network bridges became source-laundering mechanisms that obscured demonstrable collaboration or formal cooperation between different actor networks. Similar to Klein’s (Citation2012) definition of information laundering that illustrated ‘how the Internet’s unique properties allow subversive social movements to (…) quietly legitimize their causes through a borrowed network of associations’ (p. 419), it was far-right news sites and the resources of a radical right party that concealed and disguised the extremist origins of the campaign and charged it with political legitimacy. As a result, the party uptake of the Stop the Migration Pact campaign was accomplished without direct public engagement with the Identitarian campaign itself. Thus, AfD managed to move radical ideas from the political fringes into the general debate, parliamentary debates and public discourse, as the general public was not aware of the Identitarian origins of the campaign.

We also show that when networks are well aligned and produce clear frames that focus attention, strategic networking can push content through one media ecology (e.g., a platform ecosystem) and into another (e.g., the mainstream media). Once the party officially appropriated the campaign, the leadership went on the offensive and drove a wedge between the Christian Democrats and their Bavarian sister party which had been losing ground with voters to the AfD. When their intraparty conflict went public, it spilled into the MSM, bringing the AfD into many stories as the cause of the rift.

There are, of course, limits to this study. For the most active period on Twitter (31 October -10 December 2018) we had to rely on random samples of 10,000 tweets per day due to data access limitations. However, if this introduced any biases, we suspect that it most likely led to underestimation of the impact of hyperactive accounts on the emergent network dynamics. We also have surely missed some deeper links between Identitarian and low-level party activist accounts that might sharpen the picture of content flows. Such links have been detected by fine grained tracing of account interactions (Correctiv, Citation2020). Our study focused on a national version of a transnational campaign, but the complexity of multi-platform flows in different nations with different languages makes it difficult to map the spread of the entire global campaign (for a comparison of politicization of GCM in Germany, Austria and Sweden see Conrad, Citation2021). We hope that the analytical framework offered here will enable more comparative work along these lines. It is also important to note that this German-language campaign had repercussions beyond Germany, as Austria and parts of Switzerland belong to the German-speaking region. Indeed, Austrian actors play an important role here – Identitarian leader Martin Sellner is Austrian, and the role of Austrian rightwing party FPÖ and its interactions with AfD would be worth deeper exploration. Finally, movement-party interactions do not only occur online, but also at protest events, music concerts and other sub-culture occasions. Issues and frames also spread beyond online dynamics from party to party, e.g., the Austrian government’s decision to withdraw their support for the GCM may have travelled internally between the conservative parties in both countries, and between FPÖ and AfD.

Conclusion

German sociologist Dirk Baecker theorized that ‘digital platforms connect actors who previously hardly knew that they had anything to offer to each other’ and that social media can ‘enable a mass communication of excitement that until recently could hardly get beyond the beer table.’ (Baecker, Citation2018, p. 14 translation by authors). In our case, the communities likely knew that they had something to offer each other, but the populist radical right party AfD had pledged not to cooperate with the far-right extremist Identitarians. Moreover, direct endorsement of the Identitarian campaign may have alienated more moderate supporter groups. Finally, since both Identitarians and several AfD factions were under state surveillance for unconstitutional activities, any formal partnership in the campaign could bring harsh sanctions to the party.

In light of these conditions, it is not surprising that there was no direct public interaction between the Identitarian Movement and the national AfD leadership. However, direct communication proved unnecessary since the two end points of the network were linked by aligned intermediary networks that served as brokers and bridges between party and movement. This means that the party and the extremist group profited from one another not because they formed an alliance, but because of a network structure that proved mutually beneficial for promoting their respective political goals. Knüpfer et al. (Citation2020) have shown how the Identitarians had previously hijacked the #MeToo campaign. Their outsized visibility and online activism created the potential for AfD activists and leadership to monitor the appeal of their initiatives to other party supporters and, when popular, to incorporate them in the party agenda.

While our study focused on the German case of GCM protests, it was not the first case of movement-party interaction for AfD, who had previously reaped benefits from the far-right extremist PEGIDA movement (Berntzen & Weisskircher, Citation2018; Stier et al., Citation2017) or aligned with the partially far-right extremist protests against COVID-19 regulations. The interaction dynamics we have observed can be generalized to other cases as well, help understand the dynamics of the MAGA movement and the Republican party in the US or why France’s Marine Le Pen tried to establish herself as mouthpiece for the Gilet Jaune movement. In the span of a few months in 2020, for instance, Trump retweeted at least 90 posts from 49 different QAnon conspiracy accounts, despite warnings from the Federal Bureau of Investigation that the network was ‘a potential source of domestic terrorism after several people radicalized by QAnon had been charged with crimes, ranging from attempted kidnapping to murder, inspired by the conspiracy theory.’ (Nguyen, Citation2020)

This study also offers several general theoretical contributions. It is clear, as noted above, that the Migrationspakt campaign entailed a temporal dimension that was non-linear in terms of network growth. Network interactions did not grow steadily or in concentric circles but emerged in several stages as networks with larger followings took over the amplification and spread of ideas. All of this means that, unlike political campaigns in earlier party and media systems, no one specific actor, movement, group, party or organization was the core mobilizer of the campaign. Indirect interactions between parties and supporters in hybrid media systems are enabled by intersecting networks that require little or no formal organization (Chadwick, Citation2017; Klinger & Svensson, Citation2015, Citation2018). Those constituent networks were able to hand off the content despite sometimes different content production and distribution conventions. Such networked flows make conventional standards for regulating free speech and harmful content difficult, whether the responsibility falls on the state or on media companies. This new era of networked threats to democracy and liberal values requires rethinking both the organization of, and responses to political extremism.

Supplemental Material

Download QuickTime Video (196.1 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ulrike Klinger

Ulrike Klinger is Professor for Digital Democracy at European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder) and Associated Researcher at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society in Berlin, Germany [email: [email protected]].

W. Lance Bennett

W. Lance Bennett is Emeritus Professor of Political Science and Communication and Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Journalism, Media & Democracy, University of Washington, Seattle, USA [email: [email protected]].

Curd Benjamin Knüpfer

Curd Benjamin Knüpfer is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Freie Universität Berlin and Associated Researcher at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society in Berlin [email: [email protected]].

Franziska Martini

Franziska Martini is research assistant at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society in Berlin and a doctoral candidate at Freie Universität Berlin [email: [email protected]].

Xixuan Zhang

Xixuan Zhang is research assistant at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society in Berlin and a doctoral candidate at Freie Universität Berlin [email: [email protected]].

Notes

1 The assassin had donated money to the Austrian Identitarians. https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000122404267/christchurch-attentaeter-spendete-mehr-an-identitaere-als-bislang-zugegeben

2 In 2021, the Higher Administrative Court for Berlin and Brandenburg confirmed this assessment in a final decision, after the Identitarian Movement had filed a lawsuit against it. https://www.berlin.de/gerichte/oberverwaltungsgericht/presse/pressemitteilungen/2021/pressemitteilung.1100819.php

3 The text can be found on the United Nations website: https://undocs.org/en/A/CONF.231/3

4 Media Cloud is an open-source platform for studying media ecosystems. Other researchers can access this collection of sites via the website https://mediacloud.org.

5 A force-directed graph layout algorithm in Gephi models the live spatiality between nodes and edges by simulating a physical system between charged particles and springs. Due to continuous forces that converge the movement between nodes and edges to a balanced state, this algorithm is particularly suitable for the dynamic network modeling.

6 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VK6h14l3A60 - Video is not available anymore, because YouTube deleted Sellner’s account.

References

- AfD-Fraktion im Deutschen Bundestag. [@AfDimBundestag]. (2018, November 8). https://twitter.com/AfDimBundestag/status/1060474317757145088

- Arzheimer, K., & Berning, C. C. (2019). How the alternative for Germany (AfD) and their voters veered to the radical right, 2013–2017. Electoral Studies, 60, 102040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

- Baecker, D. (2018). 4.0 oder Die Lücke die der Rechner lässt. Merve Verlag.

- Bennett, W. L., & Pfetsch, B. (2018). Rethinking political communication in a time of disrupted public spheres. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqx017

- Bennett, W. L., Segerberg, A., & Knüpfer, C. B. (2018). The democratic interface: Technology, political organization, and diverging patterns of electoral representation. Information, Communication & Society, 21(11), 1655–1680. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1348533

- Bennett, W. L., Segerberg, A., & Walker, S. (2014). Organization in the crowd: Peer production in large-scale networked protests. Information, Communication & Society, 17(2), 232–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.870379

- Bennett, W. L., Segerberg, A., & Yang, Y. (2018). The strength of peripheral networks: Negotiating attention and meaning in complex media ecologies. Journal of Communication, 68(4), 659–684. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy032

- Berntzen, L.E., & Weisskircher, M. (2018). Remaining on the streets: Anti-islamic PEGIDA mobilization and its relationship to far-right party politics. In M. Caiani & O. Císař (Eds.), Radical right movement parties in Europe (pp. 114–130). Routledge.

- BfV Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz. (2020). Verfassungsschutzbericht 2020. https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/publikationen/themen/sicherheit/vsb-2020-gesamt.pdf?__blob = publicationFile&v = 6

- Bimber, B., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2020). The unedited public sphere. New Media & Society, 22(4), 700–715. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819893980

- Borbáth, E., & Hutter, S. (2021). Protesting parties in Europe: A comparative analysis. Party Politics, 27(5), 896–908. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820908023

- Bruns, A. (2005). Gatewatching: Collaborative online news production (Vol. 26). Peter Lang.

- Caiani, M., & Císař, O. (eds.). (2018). Radical right movement parties in Europe. Routledge.

- Cerulus, L., & Schaart, E. (2019, January, 3). How the UN migration pact got trolled. Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/united-nations-migration-pact-how-got-trolled/

- Chadwick, A. (2017). The hybrid media system: Politics and power (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Conrad, M. (2021). Post-truth politics, digital media, and the politicization of the global compact for migration. Politics and Governance, 9(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i3.3985

- Correctiv. (2020). Kein Filter für Rechts. Wie die rechte Szene Instagram benutzt, um junge Menschen zu rekrutieren. https://correctiv.org/top-stories/2020/10/14/kein-filter-fuer-rechts-instagram-rechtsextremismus-afd-ib-verbindungen/

- Davis, C. A., Varol, O., Ferrara, E., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2016, April). Botornot: A system to evaluate social bots. Proceedings of the 25th international conference companion on world wide web (pp. 273–274). https://doi.org/10.1145/2872518.2889302

- Fuchs, M., & Holnburger, J. (2019). #ep2019 - Die digitalen Parteistrategien zur Europawahl 2019. Hamburg. https://www.fes.de/index.php?eID=dumpFile&t=f&f=41827&token=6e1bf3bcf42bf4162ba5cc452ba460d703945e30

- González-Bailón, S., & Wang, N. (2016). Networked discontent: The anatomy of protest campaigns in social media. Social Networks, 44, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2015.07.003

- Guhl, J., & Davey, J. (2020). A safe space to hate: White supremacists mobilisation on Telegram. Institute for Strategic Dialogue. https://www.isdglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/A-Safe-Space-to-Hate2.pdf

- Guhl, J., Ebner, J., & Rau, J. (2020). The online ecosystem of the German far-right. Institute for Strategic Dialogue. https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-publications/the-online-ecosystem-of-the-german-far-right/

- Guo, L., & McCombs, M. (Eds.). (2016). The power of information networks: New directions for agenda setting. Routledge.

- Heft, A., Mayerhöffer, E., Reinhardt, S., & Knüpfer, C. (2020). Beyond Breitbart: Comparing right-wing digital news infrastructures in six Western democracies. Policy & Internet, 12(1), 20–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.219

- Heinze, A. S., & Weisskircher, M. (2021). No strong leaders needed? AfD party organisation between collective leadership, internal democracy, and “movement-party” strategy. Politics and Governance, 9(4), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i4.4530

- Jacomy, M., Venturini, T., Heymann, S., & Bastian, M. (2014). Forceatlas2, a continuous graph layout algorithm for handy network visualization designed for the Gephi software. PLoS ONE, 9(6), e98679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098679

- Karpf, D. (2016). Analytic activism: Digital listening and the new political strategy. Oxford University Press.

- Keller, T., & Klinger, U. (2020). The needle in the haystack: Finding social bots on twitter. In E. Hargittai (Ed.), Research exposed. How empirical social Science gets done in the Digital Age (pp. 30–49). Columbia University Press.

- Klein, A. (2012). Slipping racism into the mainstream: A theory of information laundering. Communication Theory, 22(4), 427–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01415.x

- Klinger, U., & Svensson, J. (2015). The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach. New Media & Society, 17(8), 1241–1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814522952

- Klinger, U., & Svensson, J. (2018). The end of media logics? On algorithms and agency. New Media & Society, 20(12), 4653–4670. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818779750

- Knüpfer, C. B., Hoffmann, M., & Voskresenskii, V. (2020). Hijacking MeToo: Transnational dynamics and networked frame contestation on the far right in the case of the ‘120 decibels’ campaign. Information, Communication & Society, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1822904

- Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How democracies die. Broadway Books.

- Martini, F. (2020). Wer ist #MeToo? Eine netzwerkanalytische Untersuchung (anti-)feministischen Protests auf Twitter. M&K Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft, 68(3), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.5771/1615-634X-2020-3-255

- Meraz, S., & Papacharissi, Z. (2013). Networked gatekeeping and networked framing on #Egypt. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18(2), 138–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161212474472

- Montgomery, J. (2018a). Hungarian Prime Minister: UN Migration Compact ‘Looks Like It Was Copied from the Soros Plan’ for Mass Migration. Breitbart. https://www.breitbart.com/europe/2018/02/06/orban-un-migration-compact-copied-soros-plan-mass-migration/

- Montgomery, J. (2018b). New United Nations boss unveils plan to promote global mass migration. Breitbart. https://www.breitbart.com/europe/2018/01/12/new-united-nations-boss-plan-promote-global-mass-migration/

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C. (2019). The far right today. Polity.

- Nguyen, T. (2020, July 12). Trump isn’t secretly winking at QAnon. He’s retweeting its followers. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/07/12/trump-tweeting-qanon-followers-357238

- Papakyriakopoulos, O., Shahrezaye, M., Serrano, J. C. M., & Hegelich, S. (2019, April). Distorting political communication: The effect of hyperactive users in online social networks. IEEE INFOCOM 2019-IEEE conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS) (pp. 157–164). IEEE. https://www.hfp.tum.de/fileadmin/w00bwi/politicaldatascience/Infocom_Hyperactive_users_personal_copy.pdf

- Pfetsch, B. (2018). Dissonant and disconnected public spheres as challenge for political communication research. Javnost-The Public, 25(1-2), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2018.1423942

- Pirro, A. L. (2019). Ballots and barricades enhanced: Far-right ‘movement parties’ and movement electoral interactions. Nations and Nationalism, 25(3), 782–802. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12483

- Reuters Digital News Report. (2020). Germany. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2020/germany-2020

- Rone, J. (2020). Far right alternative news media as ‘indignation mobilization mechanisms’: How the far right opposed the global compact for migration. Information, Communication & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1864001

- Ross, B., Pilz, L., Cabrera, B., Brachten, F., Neubaum, G., & Stieglitz, S. (2019). Are social bots a real threat? An agent-based model of the spiral of silence to analyse the impact of manipulative actors in social networks. European Journal of Information Systems, 28(4), 394–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2018.1560920

- Shaw, A., & Hill, B. M. (2014). Laboratories of oligarchy? How the iron law extends to peer production. Journal of Communication, 64(2), 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12082

- Stein, T. (2018, December 3). Wie ein AfD-Abgeordneter versuchte, die Dienstreise einer Linken zu verhindern. Watson. https://www.watson.de/deutschland/best%20of%20watson%202018/914068538-wie-ein-afd-abgeordneter-versuchte-die-dienstreise-einer-linken-zu-verhindern

- Sternberg, J. (2019, January 4). Eine gezielte Kampagne der AfD. Frankfurter Rundschau. https://www.fr.de/politik/eine-gezielte-kampagne-10966012.html

- Stier, S., Posch, L., Bleier, A., & Strohmaier, M. (2017). When populists become popular: Comparing Facebook use by the right-wing movement pegida and German political parties. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1365–1388. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328519

- Süddeutsche Zeitung. (2018, November 19). Meuthen begrüßt CDU-Debatte über UN-Migrationspakt. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/migration-magdeburg-meuthen-begruesst-cdu-debatte-ueber-un-migrationspakt-dpa.urn-newsml-dpa-com-20090101-181118-99-863736

- Townsend, M. (2020, June 21). The Iconoclast unmasked: The man behind far-right YouTube channel. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/21/the-iconoclast-unmasked-the-man-behind-far-right-youtube-channel

- Welt. [@welt]. (2018, November 30). https://twitter.com/welt/status/1068478733214986240?s = 20

- Zadrozny, B., & Collins, B. (2018, August 14). How three conspiracy theorists took ‘Q’ and sparked Qanon. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/how-three-conspiracy-theorists-took-q-sparked-qanon-n900531