ABSTRACT

The past decades have seen efforts to increase digital inclusion for women worldwide, with the ultimate aim to advance gender equality. However, progress is slow, despite important advances in moving beyond a focus on ‘digital access’ (as measured by network coverage and hardware) towards a more holistic understanding of inclusion that considers abilities, awareness and agency. Here, we propose a further theoretical shift that draws on social system theories (e.g., Luhmann, Citation1984) and on the theory of ‘intersecting inequalities’ (Kabeer, Citation2010). We propose to understand the gender digital gap, particularly in mobile and internet usage, not merely descriptively but dynamically – since even factors like agency and awareness change over time – by applying concepts of feedback loops, low-equilibrium traps, multi-dimensional exclusion and systems analysis. This paper highlights how women may become locked in a state of low-inclusion unless the feedback loops between digital, social, economic and political exclusion are addressed through policies that tackle multiple dimensions. The paper reviews research on gender digital gaps with particular focus on developing countries, and with direct implications for policy-making.

1. Introduction: why a shift in perspective is needed

Organisations and governments worldwide have made the digital inclusion of women a priority within the broader goal of advancing gender equality. This is especially true in developing countries, whether of low- or middle-income, where mobile phones and the internet are seen as promising means to address outstanding challenges such as equal access to work, education or political participation. To pursue this, for instance, the UK’s former Department for International Development (DFID) strategies, and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals include objectives dedicated to increasing the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) for women’s empowerment (DFID, Citation2018; United Nations, Citation2015). Yet, so far, digital technologies have often fallen short of meeting such expectations. Instead, we are more likely to see existing gender inequality replicated in the digital realm, even leading some to say that gender inequality is ‘one of the most significant inequalities amplified by the digital revolution’ (Moolman et al., Citation2007).

Indeed, if the benefits of digital technology accrue mostly to people who are well off in society, this is likely to exacerbate existing inequality. This is especially concerning at times of crisis, when the digital divide may contribute to the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women (Soon-Shiong et al., Citation2020). This paper argues that a theoretical shift is needed to understand the apparently slow progress in light of significant attention and investment.

We propose a shift from the current focus on internet and mobile access and proximate factors that limit it – availability, accessibility, abilities and awareness – to a much broader consideration of the feedback loops that operate between digital exclusion and other forms of social, economic and political exclusion. These feedback loops are responsible for locking women into a low-inclusion equilibrium, a stable state of low-inclusion which is difficult to break out of. Making an analogy to economic theory, these low-inclusion equilibrium states operate similarly to poverty traps, in that a small incremental investment in digital inclusion is unlikely to have any sustainable and scalable effect beyond the immediate term, and because of strong social norms, women are likely to fall back into the low-inclusion equilibrium.

This paper draws on prominent theories of complex systems (e.g., Luhmann, Citation1984) and ‘intersecting inequalities’ (Kabeer, Citation2010) to describe the need for system-level analyses to understand digital and social exclusion. In doing so, we necessarily take a broad approach, generalising from empirical studies and existing frameworks on digital exclusion, and illustrating through the use of a diverse range of examples throughout the paper. This leads to a general analytical framework that can be used by researchers and policymakers to articulate the dynamic interactions between gender inequality on the internet and mobile technology, and other forms of exclusion.

In terms of policy implications, the paper shows how this analytical perspective can move policy discussions beyond the proximate factors of women’s digital inclusion and towards multi-dimensional interventions that address several of the key aspects of exclusion. In applying this theoretical approach, not every dimension of inclusion will be relevant in every context, but the crucial insight – that of dynamic feedback loops between different dimensions of inequality, leading to a persistent low-inclusion equilibrium – has wide-ranging applications.

2. Background: why digital inclusion matters for gender equality

Over the last decades, there has been an impressive growth in internet and mobile technology availability: 97% of people worldwide live within reach of a mobile network (ITU, Citation2019), and 88% of people are covered by 3G internet networks (GSMA, Citation2019). This digital transformation is expected to create unique opportunities for socio-economic inclusion because its impact extends to all aspects of life.

Mobile phones and the internet – the key digital technologies that this paper focuses on, in line with major reports highlighting what technologies are relevant to the least included members of society (e.g., GSMA, Citation2019; ITU, Citation2019) – bring opportunities for advancing gender equality by lowering barriers to information and communication. Here, we focus primarily on developing countries, where gender equality indices show the most pressing problem (World Economic Forum, Citation2020), particularly due to intersecting inequalities on multiple dimensions, from poverty to gender-specific political and social inclusion (Kabeer, Citation2010). For instance, the World Wide Web Foundation (Citation2015) reported that in a set of seven countries (Cameroon, Colombia, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Philippines, Uganda and Egypt), women were 30–50% less likely than men to use the internet to participate in public life.

Vulnerable groups, such as people living in poverty, benefit socially and economically from digital inclusion. As the Pathways for Prosperity Commission (Citation2019a) highlighted, 690 million people have mobile money accounts that they use for paying bills, receiving cash transfers, sending remittances, savings or business, and there is evidence that mobile money has lifted people in Kenya from poverty (Suri & Jack, Citation2016). For those who are connected, the internet is increasingly the place where people find jobs (Dammert et al., Citation2015; Terry & Gomez, Citation2010), where farmers connect to markets, where drivers find ride-hailing opportunities, citizens participate in public life, and people improve their health and education (Aker & Fafchamps, Citation2015; Jensen & Miller, Citation2018).

There are some leading examples of how mobile phone and internet usage can specifically benefit women too. Women can independently find jobs through the internet or through mobile phones. Case studies in Kenya, India and even South Africa, a country with high levels of inequality, show that women who take up ‘gig’ domestic work through online platforms often use this opportunity to move from rural to urban areas, to be employed for the first time or to find work outside of their slums (Hunt et al., Citation2019). Female informal sellers use mobile phones to advertise their products in India, Peru and South Africa (Alfers et al., Citation2016). Digital technologies are documented to improve women’s access to finance; the Kenyan mobile money study mentioned above had the most pronounced poverty reduction effect amongst women (Suri & Jack, Citation2016).

Examples exist for how digital inclusion can benefit women’s education, health and public participation too. In Nairobi, girls attempted to bridge interrupted school attendance by using their mobile phones to call classmates or teachers and ask for details of missed lessons or used the internet to search for information on class topics (Zelezny-Green, Citation2014). Surveys of women from sub-Saharan Africa reveal that mobile phone ownership tends to be associated with being better informed about sexual and reproductive health (Rotondi et al., Citation2020). In India, where it is commonly expected that women should not use Facebook due to norms of purity (Barboni et al., Citation2018), there are nevertheless emerging examples of women using social media to participate in public campaigns, for instance, the #IWillGoOut campaign against sexual violence (Titus, Citation2018). Besides such one-off examples, there are promising statistics across over 200 countries that report positive correlations between mobile phone access and gender equality measurements, especially in terms of higher uptake of contraceptives and lower maternal and child mortality (Rotondi et al., Citation2020).

So why the concern, then? Many of the examples above are relatively isolated. Moreover, there is extreme variation at the individual level: ownership or access frequently fail to translate to inclusion and empowerment, especially for those women who are most vulnerable (Bailur et al., Citation2018, Citation2017).

3. Existing approaches to understanding the digital gender gap

3.1. Moving beyond access

The key problem is that there has been a longstanding focus on ‘access’, striving to ‘connect the unconnected’ and close the ‘digital divide’ in owning or accessing devices. This focus has persisted for the last two decades (e.g., Broadband Commission, Citation2019; OECD, Citation2001). To measure progress, binary measures of access were established (e.g., as part of the Sustainable Development Goals). However, as we explore below, it is clear that even if it was possible to achieve equal levels of physical access to mobile technology and the internet, this is likely insufficient to translate into gender equality. As noted by Donner (Citation2015) it is crucial to look ‘after access’: efforts need to focus on broader digital inclusion and what hinders it.

The problem with the longstanding focus on ‘access’ is best illustrated in the fact that, despite efforts to improve access to devices such as mobile phones, the gender gap in overall digital inclusion, such as usage of the internet remains wide. Across seven low- and middle-income countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Pakistan and India; Pathways for Prosperity Commission, Citation2018), women were 12–14% less likely than men to have used a phone for accessing the internet, social media, finance or entertainment, even after controlling for factors like income, education and geography. When observed over time, statistics are striking: although in developed countries, the gender gap in internet usage (measured as the difference between male and female internet penetration rates, relative to male penetration rates) fell from 5.8% in 2013 to 2.3% in 2019; on the other hand in developing countries, it grew from 15.8% to 22.8% (and 29.9% to 42.8% in the least developed countries, ITU, Citation2019). Against a backdrop of rising digital usage for both genders, men’s meaningful usage is increasing faster, widening the gender gap.

Translating digital access to socio-economic benefits has proved equally difficult. According to the World Wide Web Foundation, for instance, although 38.2% of women in Egypt used the internet, only 21% of female internet users in Cairo reported economic gain from these activities and only 7% voiced opinions online (and similar statistics were reported for Colombia, India, Indonesia, Kenya and Uganda; Sambuli et al., Citation2018). Moreover, their survey had little coverage outside of large cities, leaving open the possibility that smaller towns or rural areas have even wider gaps.

3.2. Existing frameworks point to proximate factors that limit access and usage

In recent years, analytical frameworks have moved beyond mere access to highlighting barriers that limit access and usage. This was triggered by findings that many people in developing countries who are counted as ‘connected’ in fact have unreliable or unaffordable connections or lack other affordances required for socio-economic gains (Roberts & Hernandez, Citation2019). Rather than speaking in binary terms about ‘digital access’ (something you either have or do not have), the barriers to digital inclusion extend beyond the presence of hardware and infrastructure to explain why a person who owns a phone does not use it to its full potential.

Donner (Citation2015), for instance, highlights barriers such as lack of stable wireless connection, usage-based pricing or task supportiveness of devices. Tongia et al. (Citation2005) stress four proximate factors: the ‘4As’. These are awareness (of what can be done with ICTs), availability (within proximity and with appropriate hardware and software), accessibility (literacy, language, interfaces, etc.) and affordability (under 10 percent of one’s income, at maximum). Similar frameworks are now widely adopted throughout the literature. Roberts and Hernandez (Citation2019) talk about the 5As that are similar to the 4As, but substitute ‘abilities’ and ‘agency’ in place of accessibility. The GSMA (Citation2019) categorises women’s barriers into the proximate factors of literacy and skills, affordability, safety and security and relevance. Frameworks such as these are constructive, and indeed necessary. However, as we will discuss in part 4 below, a static focus on these proximate factors is not sufficient, because these proximate factors are in turn affected by broader dimensions of inclusion in dynamic feedback loops.

For several years we have understood the proximate factors driving digital inequality (e.g., the 5As), and significant investment has been dedicated towards improving awareness, availability, affordability, etc. Yet as we have seen, gender gaps are widening (Financial Inclusion Insights FII, Citation2019; GSMA, Citation2019; ITU, Citation2019). There is not a linear relationship between the 5As and digital inclusion; other factors are involved, and simply increasing the quantity of investment in these proximate factors may not resolve the digital gender gap.

4. Broadening the perspective – feedback loops between inequalities

In the sections that follow, we propose a theoretical shift in understanding women’s digital inclusion as a series of complex feedback loops between digital and broader socio-economic inclusion. The key theory that guides our analysis is the theory of complex and dynamic social systems (Luhmann, Citation1984).

It has long been acknowledged by system theorists that society itself functions as a complex system: a mass network of communication and interaction between actors in society (Luhmann, Citation1984). Acknowledging social systems as such brings a crucial insight that such systems are not static: they are self-referential, and they involve feedback loops (Luhmann, Citation1984). As early as 1958, Forrester looked at the dynamics of complex systems, and drew attention to their non-linear development over time (Forrester, Citation1958; Citation1993). Forrester applied his analyses to technological and organisational settings, and importantly stated that the non-linearity of system dynamics needs to be taken into account by policy-makers (Forrester, Citation1958), because it shapes how policy implementation will unfold over time. Soon it was acknowledged that systems approaches are particularly powerful when it comes to ‘wicked’ or difficult, seemingly-intractable problems (Churchman, Citation1967). Nevertheless, it was not until recent years that systems thinking became a widely-used tool in academic organisational and policy analysis – this surge in new interest was motivated by the emergence of new and complex social and policy problems such as those related to technology’s role in the economy and in society (Sternman, Citation2002). Most recently, the importance of systems thinking has been at the forefront of the academic and applied policy analysis fields, covering topics such as digitalisation in the labour market (Hynes et al., Citation2020; Immervol et al., Citation2020).

But systems theory is often abstract – and in order to apply it, scholars construct or use frameworks or sector-specific system maps (e.g., Immervol et al., Citation2020). The aim of the current paper isn’t to construct a system map for the gender digital gap – but rather, it is to outline how system analysis helps provide new theoretical insights into this difficult problem. This is done in two sections, each drawing upon one additional theory and each delving into one key element of Luhmann’s (Citation1984) social systems theory. This current section uses Kabeer’s (Citation2010) theory of ‘intersecting inequalities’ in order to illustrate the complex self-referential nature of the system driving the gender digital divide and its feedback loops. Section 5 brings insights from the ‘poverty trap’ economics concept (Banerjee & Duflo, Citation2011) in order to illustrate one key consequence of negative feedback loops: the danger of low-equilibrium exclusion traps.

4.1. Interactions between different dimensions of inequality

First let us start by bringing Kabeer’s (Citation2010) ‘intersecting inequalities’ theory to bear on the gender digital gap, by making an analogy. When analysing why progress on the Millennium Development Goals was slow, social economist Kabeer (Citation2010) argued that this was because disadvantaged people were subject to a set of ‘intersecting inequalities’. Importantly, these inequalities are mutually reinforcing in dynamic feedback loops, which makes them more persistent over time. Women, too, are subject to such intersecting inequalities: women have less access to society’s resources and opportunities, resulting in less economic participation, less education and less influence in decisions that are relevant to their lives and their communities (Kabeer, Citation2010; Paz Arauco et al., Citation2014). To exemplify Kabeer’s notion of reinforcing inequalities, let us consider what factors lead to poorer health of rural women (as described by World Bank, Citation2013): it is expensive to provide quality health services in remote areas where indigenous women live, but indigenous women are also discriminated against by staff, and furthermore have less voice, limiting their ability to ask for better services. In the rest of the paper, we argue that such negative feedback loops exist in digital exclusion too, and may help explain why gaps remain wide. When Tongia et al. (Citation2005) proposed the 4As, they noted that ‘the digital divide is actually a manifestation of other underlying divides’. Digital inequality is caused by exclusion along other dimensions, but digital inequality also exacerbates other forms of exclusion. This is a dynamic system where the casual relationship operates in both directions; it is a feedback loop where digital inequality is both symptom and cause.

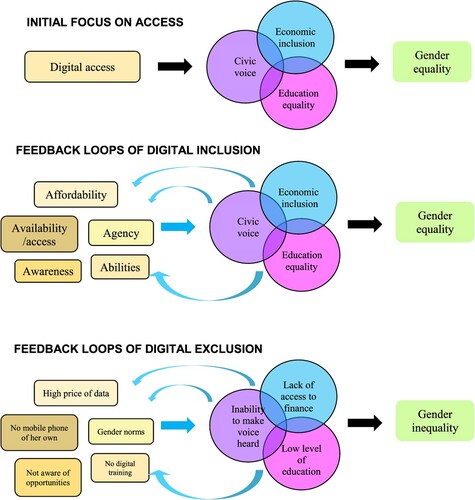

shows how this compares to the common ‘digital access’ narrative. The top panel shows this commonly described linear process where ‘digital access’ will improve broader outcomes for women. Instead, in the middle and bottom panels, we propose a shift in theoretical perspective where ‘digital access’ is instead replaced with the proximate factors required to achieve digital inclusion (in the figure, the 5As). Digital inclusion can then improve broader outcomes or digital exclusion can feed into broader exclusion (represented in the figure as three other dimensions of inequality: economic, educational and civic voice, as illustrated with examples based on dimensions described by Kabeer, Citation2010).

Figure 1. A common simplified view (top) of how digital access leads to gender equality; in reality there are complex feedback loops that can lead to inclusion (middle) or to exclusion (bottom).

Importantly, the relationship flows in two directions; these dimensions of socio-economic inclusion (or exclusion) also cause greater digital inclusion (or exclusion). These can be mutually reinforcing – say if the availability of digital tools leads to increased learning, which boosts digital agency, which increases economic participation and finally comes back around to an ability to afford more complex digital activities. But these feedback loops also make it hard for individual interventions to succeed. For instance, if women have low levels of education relative to men, then they are less likely to have the baseline literacy required to use digital technology and, therefore, less likely to access digital services that might help increase their economic participation or voice in the community. Next, we will explore in more detail how three dimensions of inequality – economic inclusion, education outcomes and civic participation – interact with digital inclusion.

4.2. Beyond affordability: the effects of broader economic exclusion

Affordability is a recognised barrier to digital participation, and it disproportionately affects women: as reported by FII (Citation2017), when a family has limited economic resources, women will be the first to sacrifice their ownership of mobile phones. But beyond cost, there are further economic barriers that affect women in particular.

Unfortunately, women’s access to finance is limited across many developing countries. They have less independent access to, and agency in using economic resources, both in terms of spending in the family, as well as access to cash transfers from the government, even when these are specifically aimed towards them (e.g., in Pakistan, 47% of government transfers directed at women were cashed by male relatives; Alliance for Financial Inclusion, Citation2018).

Digital technologies are often touted as a means to increase women’s economic participation (see Section 2), but the economic benefits of digital access accrue more slowly to women than to men. For instance, using mobile phones to sell produce may be an opportunity for women, but not without finance to start trading. Women may take up domestic work on ‘gig’ platforms, but only if they have the money to pay for transport to reach the location of the work (Hunt et al., Citation2019). Without broader economic inclusion such as access to finance, women remain less able to participate in digital life, and making digital products more affordable alone will not solve this.

During a time of crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the feedback loops between digital, financial and societal exclusion of women become more apparent. Many of the jobs that women usually do, such as domestic cleaning or care work, are the first to become unavailable during a pandemic (International Labour Organisation, Citation2021), and in addition, when schools and childcare facilities close, the social expectation is for women to take primary responsibility for new childcare duties. While digital transfers from governments may help some of those affected by a pandemic, as described above, women often lack access to such digital transfers, which further exacerbates inequality (Soon-Shiong et al., Citation2020). Feedback loops between digital and socio-economic exclusion disproportionately affect women: what looks like a temporary loss of jobs may translate into longer-term gender gaps.

4.3. Beyond digital abilities: the importance of education

A survey by GSMA (Citation2019) revealed that in developing countries, women rated literacy and skills as the second most important barrier to mobile phone ownership, and the top barrier to internet usage. Again, this seems to affect women more than men, as literacy is lower amongst women (Rashid, Citation2016). Studies see an under-investment in digital skills for women because these are not considered necessary for their roles as household caretakers (Bornman, Citation2016; Muralidharan & Prakash, Citation2017). But the relationship between education and digital participation extends beyond digital skills.

General education is the primary predictor of mobile phone ownership and internet usage in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Pakistan and India, above socio-economic status or urban/rural living (Barboni et al., Citation2018; Pathways for Prosperity, Citation2018). Indeed, for educated women, the gender gap in mobile ownership reduces to only 10 percentage points lower than men from an average of 33 percentage points (Barboni et al., Citation2018; Muralidharan & Prakash, Citation2017).

Education relates to digital participation in complex ways: families that are keen to educate their daughters may allow digital use more, and develop their digital skills more; and educated women may be more likely to stand up to restrictive social norms. Indeed, evidence shows that education can change power relationships, giving confidence, ‘an ability to speak’ and helping women have a greater decision capacity within their homes (as reported in Bangladesh; World Bank, Citation2013). A focus on digital access and digital abilities will struggle to succeed in a context where girls are systematically excluded from general education.

4.4. Beyond awareness and agency: where civic voice plays a role

The 4A/5A framework tells us that women benefit less from digital technologies because of a lack of awareness and agency. For example, they are less aware of the existence and benefits of the mobile internet (GSMA, Citation2019), and of the benefits of storing value using mobile money (in Bangladesh, it was found that women preferred to store value in products or livestock, partly because it is less confusing than new mobile money products, Bailey, Citation2017). And in the same Bangladesh study, women could not use mobile money independently because they needed to be accompanied by male relatives to the market to conduct every transaction.

The difficulty is that gaining digital awareness and agency is dependent upon having a voice in society. As O’Donnell and Sweetman (Citation2018) observe, if women generally have less voice in society, this is often reflected in low levels of online content that could help women understand and protect their rights. Similarly, without empowered role models, even when women do have the agency to use social media, they find it more difficult to know how to organise on social media to defend their rights (Titus, Citation2018).

As Valenzuela and Rojas (Citation2019) suggest, even at the same level of access and agency to use the internet, women’s inclusion will remain limited by smaller social networks than men, less social capital and degree to which their voices are heard. Indeed, this is perhaps the area where it is most clear that digital inclusion is deeply tied to broader dimensions of inequality: ‘digital agency’ does not really exist as a separate concept from broad individual, social and political agency.

Such strong feedback loops are characteristic of any dynamic system (Forrester, Citation1958). But they are often disregarded by policy-makers who focus on addressing factors separately rather than the whole of a system, particularly when it comes to novel problems such as technology use (Hynes et al., Citation2020). As Bailur et al. (Citation2018) and the Pathways for Prosperity Commission (Citation2019b) discuss, progress towards empowerment in the digital age requires action across the board. Improving isolated facets of the problem will not be sufficient: concerted efforts across the system are needed.

5. Feedback loops and the low-inclusion equilibrium

Feedback loops between digital exclusion and broader exclusion may lock some women in a low-inclusion equilibrium: a state of stable low-inclusion or outright exclusion that is nearly impossible to break out of.

As described above, the proximate factors of access, affordability, abilities and agency are not sufficient to explain the barriers that women face in the digital world. Rather, digital exclusion is also a product of broader exclusion and ‘intersecting inequalities’ (Kabeer, Citation2010). Furthermore, mutually-reinforcing feedback loops are part of any dynamic social system (Forrester, Citation1958; Luhmann, Citation1984).

Such feedback loops between digital and broader exclusion can result in a more worrisome mechanism, which is that modest improvements may not persist over time. Here, we draw on both systems theory (Luhmann, Citation1984) and poverty trap theories (Banerjee & Duflo, Citation2011) to explain how we understand this mechanism to work and illustrate with examples of digital gender norms.

5.1. Low-inclusion equilibrium mechanisms

A low-inclusion state may be maintained through an equilibrium acting like a ‘trap’. Banerjee and Duflo (Citation2011) describe how the poor in developing countries become locked in ‘poverty traps’, ‘health traps’, ‘educational traps’ and so on. Here we draw an analogy to the classic ‘poverty trap’, which occurs because a person needs to consume a given constant of their income today just to keep themselves alive and healthy, and only the income in surplus of this initial quantity can be invested to increase work capacity and (potentially) lead to higher income tomorrow. This creates an S-shaped capacity curve characterised by two states of equilibrium: a low and a high state.

If a person’s income is below the inflection point between the two equilibria, it is incredibly hard to create a persistent increase in income. Small increments in income are no longer helpful: the person will fall back into the low-equilibrium state. The crucial stipulation of the low-equilibrium trap models is that small investments (of income, money, health and education) do not pay off very much, and may have zero impact on overall outcomes over the long term.

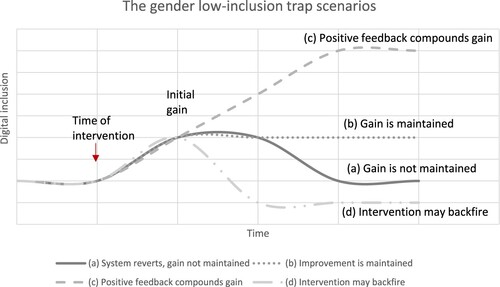

It takes a large initial investment to break out of the low-equilibrium, push an individual towards the ‘high’ equilibrium point, and avoid falling back into the trap. As Banerjee and Duflo explain, the model is applicable to a range of ‘traps’ other than income. There can be, for instance, a health trap, where buying a bed net to protect against malaria is a fixed investment of a relatively low value, so any money that is less than that is too little to make a difference: if you don’t have enough money for this initial investment, you will get sick more often and as a result be less productive and able to earn less, having less money to spend on food or healthcare, becoming trapped in a low health equilibrium. Gender inequality – we argue here – is a similar, yet not identical, ‘trap’ mechanism where individuals, and indeed whole sections of society, can become locked into a low-level equilibrium. The question of equality also involves at least two equilibrium states: a stable state of low-inclusion or a stable state(s) of higher inclusion. In this framework, a modest intervention for inclusion (e.g., investing in digital abilities to increase women’s capacity to use digital tools) may not be enough to counter other dimensions of exclusion that exist in the feedback loops described above. In the face of strong restrictive gender norms or hierarchical structures, any initial gains may be lost over time ().

Figure 2. The gender low-inclusion trap means that efforts to improve digital inclusion often lead to only a temporary gain, which is not maintained in the longer term, as in (a). Interventions need to address multiple system components to lead to maintained gains (b), or to positive feedback loops that compound gains over time and lead to a higher inclusion equilibrium (c), particularly in the face of danger that sometimes interventions may backfire due to social sanctions, and worsen the initial inequality (d). Note that this diagram should not be confused for the poverty trap S-curve we discussed above, on which the x-axis would be income today (or in our case, inclusion), and the y-axis is income (or inclusion) at period t+1.

One point where gender inequality differs from the classic poverty trap is that interventions may even backfire: progressive interventions may prompt a backlash that could include social sanctions against women (this is discussed further, with examples, in the next section). This is why a system-wide approach is needed for initial gains to be maintained or to trigger positive feedback loops that compound gains over time.

5.2. Low-inclusion equilibrium and gender norms

Restrictive gender norms cut across all sources of gender inequality, and this is a problem worth considering here. In sociological terms (Horne & Mollborn, Citation2020), norms are crucial in maintaining social order (itself a type of equilibrium) within a social system, even when this involves maintaining inequalities (a low-inclusion equilibrium) or even worsening them through norm-triggered sanctions.

Gender norms manifest in many ways around the world. Gender norms restrict public participation: in rural Cambodia, Evans (Citation2019) reported that while men gathered in cafes to discuss business and politics, women were not welcome in these spaces, and it was believed that women should not take part in such discussions. Educational access is restricted, too: in countries such as Bangladesh, girls are expected to marry by age 18, and education is not seen as necessary (Buchmann et al., Citation2018).

Norms also affect economic participation, with expectations in many countries that women should not have rights to land property or work outside the home (Duflo, Citation2012). In Saudi Arabia, a high-income country with high gender inequality relative to its GDP, women are expected to stay out of the workforce. This last example is a particularly interesting case of a feedback loop creating a low-equilibrium state. A recent study found that most men would personally be happy for their wife to work, but they (mistakenly) believe that their neighbours and peers hold more conservative views (Bursztyn et al., Citation2018). A small change – say a one or two percentage point change in female workforce participation – is unlikely to break this equilibrium; instead, it requires a more significant shift to show that there is broad acceptance for women to be in work.

An example that illustrates the danger of backfiring () is an intervention to reduce intimate-partner violence in Rwanda, which resulted in increased violence rates (Cullen et al., Citation2020). According to researchers, this was due to male identities dictating that the role of men was to hold power in their households. The intervention aimed to change gendered roles in the home, beyond reducing violence, but these aims were too ambitious compared to what normative change a short programme could deliver, and thus backfired.

Gender norms apply to the digital realm too. Data from Bangladesh reports social norms as the third most common reason for not owning a mobile phone (23% of non-owners reported this reason, FII, Citation2019). In India, usage of mobile phones showed a gender gap of 15–20% for calls, over 50% for using applications on smartphones and over 60% for social media, and this is strongly related to gender norms. Unmarried girls are often not allowed to use mobile phones because it is considered that their purity will be damaged by being exposed to online content. Even after marriage, many women in India are still not allowed to use mobile phones because it signals lack of dedication to care for their family (Barboni et al., Citation2018). The use of public WiFi hotspots in India (Mudliar, Citation2018), and internet cafes in Bangladesh, Algeria, Turkey and Pakistan (Long, Citation2005) is restricted due to their perceived threat to purity (Terry & Gomez, Citation2010).

Gender norms also affect how digital technologies can be used for socio-economic purposes: for instance, husbands believed that their wives should not take up work on ‘gig’ platforms because this would make them unaware of their wives’ locations (Hunt et al., Citation2019). In Ghana, Uganda and Kenya, women’s use of the internet for economic purposes was limited by cultural constraints (Bailur & Masiero, Citation2017).

The case of women’s lack of voice in digital spaces (described in 4.4) is one potent illustration a ‘trap’ in a stable equilibrium of exclusion. Hussain and Amin (Citation2018) studied women in Afghanistan and found that they used mobile phones to fulfil their daily duties in the family (looking up cooking lessons or how to raise children), but accessing the internet for empowerment (for example, to look up citizen rights) was regulated by their male relatives. In some instances, the exclusion was outright: for instance, a brother wanted to stop his sisters from using Facebook to prevent them from seeing images of empowered new Afghan women, and such policing led to a new inequality in access to news and information (Hussain & Amin, Citation2018). In turn, low levels of information, as Valenzuela and Rojas (Citation2019) observe, lead to the most disadvantaged being more likely to be misinformed, less likely to create content, and as a result, become excluded in online bubbles. A low-empowerment equilibrium results, where small increments of access or agency may not be sufficient unless improvements across the board are made in digital content as well as education and voice.

Crucially, social sanctions related to gender norms (Horne & Mollborn, Citation2020) maintain the low-equilibrium trap or even worsen inequality. In India, one community organisation instituted fines for families who allowed unmarried girls to own a phone, and sometimes actions taken against the family could even include outcasting (Barboni et al., Citation2018). When social barriers run this deep, small steps of resistance from one or a few families can lead to serious repercussions that further reinforce the norm, and as such, it would take widespread resistance to break out of the norm’s equilibrium.

A modest improvement in digital inclusion is difficult to maintain, and low-exclusion equilibrium states are difficult to break out of, because feedback loops of exclusion will continue to exert downward pressure. Any digital intervention has to push against not only the immediate proximate factor it is trying to address, but also the weight of an interlinked system of exclusion.

5.3. Future research and policy directions

Analysing gender digital gaps through the perspective of inter-linked dynamic systems of intersecting inequalities opens up new directions for research and policy formulation.

The first prediction generated by our theoretical approach is that interventions that target a single dimension of exclusion will be less effective, over time, than interventions that target multiple dimensions of systemic exclusion. To exemplify, we predict that investing in a programme that gives women mobiles phones will be less effective, due to negative feedback loops operating over time, than investing in an intervention that gives women easier access to technology (e.g., through an IT community centre) while also sustaining this through other supporting interventions that can generate positive feedback loops over time. For instance, such an intervention may build a social support group around women’s use of technology, give women funds to participate and promote role models who can inspire a change in cultural consciousness.

Ultimately, our argument is that although multi-dimensional interventions may be more expensive upfront, the gains multiply dynamically, especially in circumstances when due to low-inclusion traps (see ), a one-dimensional intervention would otherwise see any initial gains lost in the mid- to long-term. Establishing an empirical base for this argument still needs substantial work. Future research could investigate whether modest interventions to break negative feedback loops (e.g., by raising women’s ambitions in the community) can increase the effectiveness of direct interventions (e.g., providing digital hardware). It would also be valuable to analyse the cost-efficiency relative to simply investing extra money in a direct intervention.

There is a further, more specific prediction that our theoretical perspective generates about social norms. This is that interventions need to be balanced across multiple dimensions, and include a realistic view of what normative change can be achieved during the timespan of the intervention, in order to avoid backlash due to change-resistant social norms, as discussed in Section 5.2 of this paper. This, again, is a testable prediction, and it is crucial to conduct further research into the features that distinguish successful long-term interventions from those that backfire against existing norms.

Finally, apart from a focus on the multi-dimensional nature of interventions, our contribution also makes a prediction about the magnitude of an intervention: unless enough resources and effort are expended to cross the inflection point of low-inclusion traps, the benefits may not persist. For policymakers with constrained resources, this would likely suggest investing in fewer priorities at a time, but fully resourcing a suite of multi-dimensional interventions that complement each other before moving on to the next priority.

6. Conclusion: making sure policies are multi-dimensional

The theoretical shift we have proposed can help move the conversation beyond digital ‘access’ but also beyond its proximate 4A/5A barriers, and towards a system-analysis approach that acknowledges feedback loops and the low-inclusion equilibrium states that can emerge due to such loops.

This exposes a rich agenda for future research drawing on social system theory (Luhmann, Citation1984) and on the dynamic feedback loops unveiled here to understand the barriers to digital inclusion. In presenting our new theoretical perspective, we have taken a broad approach: drawing from many global examples to demonstrate how these concepts have common relevance in many different contexts. Here we have illustrated mainly with examples related to mobile phones and internet usage. As the next step for future research, it will be important to apply this approach to analyse a single case in depth (looking at a specific country, community or intervention, as exemplified in 5.3.) and to reveal new and useful insights.

A key message of our paper is that, in order for women in developing countries to benefit as much from digital technologies as men – in order to close the digital gender gap, and to bring broader benefits to gender equality – successful policies are likely to involve concerted efforts across the multiple dimensions of exclusion. Digital technologies can have immense positive impacts: connecting people to new economic opportunities; helping them exercise their voice; and showing them role models that raise their ambitions. But these benefits do not accrue evenly across society: the digital gender gap persists and is getting wider in developing countries.

To tackle the growing gender divide, and to ensure that gains are maintained or even compounded over time, policy-makers should look beyond singular interventions for digital access, digital skills or campaigns for digital awareness. They should, instead, make changes to the enabling environment and tackle systemic inequality. Only carefully tailored multi-dimensional interventions can ensure that digital technologies fulfil the promise of helping women gain a head start in a changing world.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Elizabeth Stuart and Stefan Dercon for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Raluca David

Raluca David worked as a Research Associate at Digital Pathways, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford, looking at gender norms and digital technologies. Raluca is currently a Teaching Fellow in Psychology at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Open Learning.

Toby Phillips

Toby Phillips is a researcher at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. Having previously been the Head of Research and Policy for Digital Pathways for three years, Toby studies broad issues of digital economic development and digital transformation.

References

- Aker, J. C., & Fafchamps, M. (2015). Mobile phone coverage and producer markets: Evidence from West Africa. The World Bank Economic Review, 29(2), 262–292. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhu006

- Alfers, L., Bali, N., Bird, M., Castellanos, T., Chen, M., Dobson, R., Hughes, K., Roever, S., & Rogan, M. (2016). Technology at the bottom of the pyramid: Insights from Ahmedabad (India), Durban (South Africa) and Lima (Peru). Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO). https://www.wiego.org/publications/technology-base-pyramid-insights-ahmedabad-india-durban-south-africa-and-lima-peru.

- Alliance for Financial Inclusion. (2018). Fintech for Financial Inclusion: A framework for digital financial transformation. https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/publications/2018-09/AFI_FinTech_Special%20Report_AW_digital.pdf

- Bailey, S. (2017). Electronic transfers in humanitarian assistance and uptake of financial services: A synthesis of ELAN case studies. Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/11424.pdf

- Bailur, S., & Masiero, S. (2017). Women’s income generation through mobile internet: A study of focus group data from Ghana, Kenya, and Uganda. Gender, Technology and Development, 21(1-2), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2017.1385312

- Bailur, S., Masiero, S., & Tacchi, J. (2018). Gender, mobile, and development: The theory and practice of empowerment. Information Technologies & International Development (Special Section), 14, 96–104. https://itidjournal.org/index.php/itid/article/view/1555/589.html

- Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2011). Poor economics: A radical rethinking of the way to fight Global poverty. Public Affairs. https://economics.mit.edu/faculty/eduflo/pooreconomics

- Barboni, G., Field, E., Pande, R., Rigol, N., Schaner, S., & Troyer Moore, C. (2018). A tough call: Understanding barriers to and impacts of women’s mobile phone adoption in India. Evidence for Policy Design, Harvard Kennedy School. https://wappp.hks.harvard.edu/files/wappp/files/a_tough_call_epod.pdf

- Bornman, E. (2016). Information society and digital divide in South Africa: Results of longitudinal surveys. Information, Communication & Society, 19(2), 264–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1065285

- Broadband Commission. (2019). The state of Broadband 2019. Broadband as a foundation for sustainable development. International Telecommunication Union. https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-s/opb/pol/S-POL-BROADBAND.20-2019-PDF-E.pdf

- Buchmann, N., Field, E., Glennerster, R., Nazneen, S., Pimkina, S., & Sen, I. (2018). Power vs money: Alternative approaches to reducing child marriage in Bangladesh, a randomized control trial (Poverty Action Lab Working Paper). https://www.povertyactionlab.org/sites/default/files/research-paper/Power-vs-Money-Working-Paper.pdf

- Bursztyn, L., González, A. L., & Yanagizawa-Drott, D. (2018). Misperceived Social Norms: Female Labor Force Participation in Saudi Arabia. (NBER Working Paper No. 24736). https://www.nber.org/papers/w24736

- Churchman, C. (1967). Wicked problems. Management Science, 14(4), B-141–B-146. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.14.4.B141

- Cullen, C., Alik-Lagrange, A., Ngatia, M., & Vaillant, J. (2020, November). The Impacts of an Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Program: Experimental Evidence from a Couples Training program in Rwanda [Paper presentation]. NEUDC Virtual Conference 2020. https://sites.google.com/dartmouth.edu/neudc2020/schedule-papers/schedule-day-2?authuser=0#h.2hebu2vkzaza

- Dammert, A. C., Galdo, J., & Galdo, V. (2015). Integrating Mobile Phone Technologies into Labor-market Intermediation: A Multi-treatment Experimental Design. (IZA Discussion Paper No. 9012). https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/9012/integrating-mobile-phone-technologies-into-labor-market-intermediation-a-multi-treatment-experimental-design

- Department for International Development. (2018). DFID Strategic Vision for Gender Equality. A Call to Action for Her Potential, Our Future. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/708116/Strategic-vision-gender-equality1.pdf

- Donner, J. (2015). After access: Inclusion, development, and a more mobile internet. MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/after-access

- Duflo, E. (2012). Women empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4), 1051–1079. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051

- Evans, A. (2019). How cities erode gender inequality: A New theory and evidence from Cambodia. Gender & Society, 33(6), 961–984. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243219865510

- Financial Inclusion Insights. (2017). Financial Inclusion Insights 2017 survey data. http://finclusion.org/reports/

- Financial Inclusion Insights. (2019). Financial Inclusion Insights Bangladesh Wave 6 Report. http://finclusion.org/uploads/file/reports/fii-bangladesh-wave-6-2018-report(2).pdf

- Forrester, J. W. (1958). Industrial dynamics-A major breakthrough for decision makers. Harvard Business Review, 36(4), 37–66. https://kupdf.net/download/industrial-dynamics-a-major-breakthrough-for-decision-makers_5902479bdc0d603940959ed5_pdf

- Forrester, J. W. (1993). System dynamics and the lessons of 35 years. In K. B. De Greene (Ed.), A systems-based approach to policymaking (pp. 199–240). Springer.

- GSMA. (2019). The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2019. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/GSMA-The-Mobile-Gender-Gap-Report-2019.pdf

- Horne, C., & Mollborn, S. (2020). Norms: An integrated framework. Annual Review of Sociology, 46(1), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054658

- Hunt, A., Samman, E., Tapfuma, S., Mwaura, G., Omenya, R., Kim, K., Stevano, S., & Roumer, A. (2019). Women in the gig economy paid work, care and flexibility in Kenya and South Africa. Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/publications/11497-women-gig-economy-paid-work-care-and-flexibility-kenya-and-south-africa

- Hussain, F., & Amin, S. N. (2018). ‘I don’t care about their reactions’: Agency and ICTs in women’s empowerment in Afghanistan. Gender & Development, 26(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2018.1475924

- Hynes, W., Lees, M., & Müller, J. M. (2020). Systemic thinking for policy making: The potential of systems analysis for addressing global policy challenges in the 21st century, new approaches to economic challenges. OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd.org/publications/systemic-thinking-for-policy-making-879c4f7a-en.htm

- Immervol, H., MacDonald, D., Rovenskaya, E., & Ilmola, L. (2020). Social protection in the face of digitalisation and labour market transformations. In W. Hynes, M. Lees, & J. Müller (Eds.), Systemic thinking for policy making: the potential of systems analysis for addressing global policy challenges in the 21st century (pp. 99–111). OECD Publishing.

- International Labour Organisation. (2021). ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. 7th edition. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/ilo-monitor-covid-19-and-world-work-seventh-edition-enardeiditjpnlptrutrvizh

- International Telecommunications Union. (2019). Measuring digital development. Facts and figures. https://itu.foleon.com/itu/measuring-digital-development/home/

- Jensen, R., & Miller, N. H. (2018). Market integration, demand, and the growth of firms: Evidence from a natural experiment in India. American Economic Review, 108(12), 3583–3625. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161965

- Kabeer, N. (2010). Can the MDGs provide a pathway to social justice? The challenge of intersecting inequalities. Institute for Development Studies and UN MDG Achievement Fund. http://www.mdgfund.org/sites/default/files/MDGs_and_Inequalities_Final_Report.pdf

- Long, J. (2005). ‘There’s no place like home’? domestic life, gendered space and online access. Proceedings of the international symposium on women and ICT, 12 June 2005, 12-es.

- Luhmann, N. (1984). Soziale Systeme. Grundriß einer allgemeinen Theorie. Frankfurt.

- Moolman, J., Primo, N., & Shackleton, S. J. (2007). Taking A byte of technology: Women and ICTs. Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, 21(71), 4–14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27739232?seq=1

- Mudliar, P. (2018). Public WiFi is for Men and Mobile Internet is for Women: Interrogating Politics of Space and Gender around WiFi Hotspots. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 01 November 2018, 2(CSCW), 1–24.

- Muralidharan, K., & Prakash, N. (2017). Cycling to School: Increasing secondary school enrollment for girls in India. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(3), 321–350. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20160004

- O’Donnell, A., & Sweetman, C. (2018). Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs. Gender & Development, 26(2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2018.1489952

- OECD. (2001). Understanding the digital divide. https://www.oecd.org/sti/1888451.pdf

- Pathways for Prosperity Commission. (2018). Digital Lives: Meaningful Connection for the Next Three Billion. https://pathwayscommission.bsg.ox.ac.uk/digital-lives-report

- Pathways for Prosperity Commission. (2019a). The Digital Roadmap: How developing countries can get ahead. https://pathwayscommission.bsg.ox.ac.uk/digital-roadmap

- Pathways for Prosperity Commission. (2019b). Positive Disruption: Health and education in the digital age. https://pathwayscommission.bsg.ox.ac.uk/positive-disruption

- Paz Arauco, V., Gazdar, H., Hevia-Pacheco, P., Kabeer, N., Lenhardt, A., Masood, S. Q., … Mariotti, C. (2014). Strengthening social justice to address intersecting inequalities post-2015. Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/publications/8909-strengthening-social-justice-address-intersecting-inequalities

- Rashid, A. T. (2016). Digital inclusion and social inequality: Gender differences in ICT access and use in five developing countries. Gender, Technology and Development, 20(3), 306–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971852416660651

- Roberts, T., & Hernandez, K. (2019). Digital access Is Not binary: The 5 ‘A’s of technology access in the Philippines. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 85(4), 12084. https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12084

- Rotondi, V., Kashyap, R., Pesando, L. M., Spinelli, S., & Billari, F. C. (2020). Leveraging mobile phones to attain sustainable development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(24), 13413–13420. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1909326117

- Sambuli, N., Brandusescu, A., & Brudvig, I. (2018). Advancing women's rights online. World Wide Web Foundation. http://webfoundation.org/docs/2018/08/Advancing-Womens-Rights-Online_Gaps-and-Opportunities-in-Policy-and-Research.pdf

- Soon-Shiong, N., Qhotsokoane, T., & Phillips, T. (2020). Using digital technologies to re-imagine cash transfers during the Covid-19 crisis. (Digital Pathways at Oxford Paper Series no. 2) https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/publications/using-digital-technologies-re-imagine-cash-transfers-during-covid-19-crisis

- Sternman, J. D. (2002). System dynamics: Systems thinking and modeling for a complex world. (MIT Engineering Systems Division Working Paper Series ESD-EP-2003-01.13-ESD Internal Symposium). http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/102741

- Suri, T., & Jack, W. (2016). The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money. Science, 354(6317), 1288–1292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah5309

- Terry, A., & Gomez, R. (2010). Gender and public access computing: An international perspective. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 43(5), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2010.tb00309.x

- Titus, D. (2018). Social media as a gateway for young feminists: Lessons from the #IWillGoOut campaign in India. Gender & Development, 26(2), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2018.1473224

- Tongia, R., Subrahmanian, E., & Arunachalam, V. S. (2005). Information and communications technology For sustainable development: Defining a global research agenda. Allied Publishers. http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~rtongia/ict4sd_book.htm

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations Population Fund. https://www.unfpa.org/resources/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development

- Valenzuela, S., & Rojas, H. (2019). Taming the digital information tide to promote equality. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(11), 1134–1136. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0700-9

- World Bank. (2013). Inclusion Matters. The foundation for shared prosperity. Advance Edition. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/114561468154469371/Inclusion-matters-the-foundation-for-shared-prosperity

- World Economic Forum. (2020). Global Gender Gap Report 2020. https://www.weforum.org/reports/gender-gap-2020-report-100-years-pay-equality

- World Wide Web Foundation. (2015). Women’s Rights Online: Translating Access into Empowerment. https://webfoundation.org/research/womens-rights-online-2015/

- Zelezny-Green, R. (2014). She called, she googled, she knew: Girls’ secondary education, interrupted school attendance, and educational use of mobile phones in Nairobi. Gender & Development, 22(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2014.889338