ABSTRACT

Through a mixed-methods approach consisting of a directed content analysis of five established LGBT+ organizations’ use of Twitter and Facebook during a month in 2022, and semi-structured qualitative interviews with social media content producers, the study attempts to understand the role of self-controlled social media spaces in challenging the Uganda society’s logics of oppression. The results indicate that self-controlled spaces are not used for disrupting the basis for repression – the local logic of oppression – or its cocoon of collective post-colonial amnesia. Nor were spaces used for re-constructive engaging with transnational and development partners’ unwitting impact on global south actors’ agency and legitimacy. Instead, with a few exceptions, spaces displayed a conspicuous uniform human rights advocacy rhetoric, and Western identity labels summarized in the LGBT+ acronym. The interviews with social media content producers suggest that the LGBT+ community’s dependency on international support may sway actors into what we call performative visibility, in self-controlled spaces. The study concludes that future analysis of Global South based activist’s use of social media spaces’ affordances including its potential for supporting de-colonialization efforts, must approach use as relational to actors’ dependency on key resources such as funding and protection through affiliation.

Introduction

Early optimistic interpretations argued that social media would offer organizations many key affordances, such as managing visibility, ensuring the permanence of digital artefacts, allowing for continuous editing and endless opportunities to engage in association and networking (Treem & Leonardi, Citation2013). For cash-strapped activist and their organizations social media affordances thus offer affordable solutions to several key activism functions, such as wide dissemination of the social actors’ discourses, mobilization and coordination of direct actions, organization of internal work, (self-) recording of protest and acts of resistance, as well as archiving of records (Cammaerts, Citation2015). For marginalized communities, with limited access to traditional public spaces such as mainstream media, political forums, and/or town halls. Social media gave them possession of a self-controlled public space where they were in a significantly better position to control portrayal and discursively oppose and reject their marginalization. For activists across the Global South, social media offered activists new and welcomed opportunities to fundraise and access resources the local scene would not provide (Amtzis, Citation2014; Saxton & Wang, Citation2014).

The optimistic take on social media has, however, been challenged because emancipatory promises often remain unfulfilled and unrealized (Fuchs, Citation2021; Gerbaudo, Citation2012; Hutchinson, Citation2021). Several aspects limit the returns of the social media presence, the proprietary nature of social media platforms and the commercial logics which are embedded in its algorithms, place marginalized positions at a great disadvantage in the attention-game unless they can afford to pay for visibility. Minority opinions and causes that fail to drum up enough attention coupled with limited resources to pay for visibility, thus continue to struggle to be seen/heard in neo-liberal media-saturated noisy social media environments (Hutchinson, Citation2021; Trillò, Citation2018). It could thus be argued that having access to self-controlled digital media spaces, such as social media, only refers to the users’ control over content production within the confines of the platforms’ content moderation standards. Some content moderation practices, including the removal of content deemed to be sensitiv, have, for example, impacted LGBT+Footnote1 activism negatively (Roberts, Citation2019). Self-control thus simply refers to control over self-expression but not to what degree the same content is actually noticed by a larger audience. Marginalized voices thus often remain invisible outside their already established networks. Despite these caveats, marginalized voices and activists representing oppressed communities have adopted digital tools and digital media, including social media en masse.

LGBT+ communities are often among the most marginalized (Reid, Citation2020; Weiss & Bosia, Citation2013). Social media has allowed LGBT + activists across the world, despite a shoestring budget, to pursue sustained advocacy for de-criminalization, anti-discrimination policies and greater societal acceptance (Currier & Moreau, Citation2016; Edenborg, Citation2020; Oluoch & Tabengwa, Citation2017). Digital tools and social media afford LGBT+ activists better opportunities to document abuse and enable remote publics to become ‘distant witnesses’, which can raise awareness and assist in generating solidarity (Ng, Citation2017). Cases detailing how LGBT+ activism have benefited from the strategic use of social media span individual countries and regional contexts (Currier & Moreau, Citation2016; Mutsvairo, Citation2016), to trans-Atlantic activism (Ciszek, Citation2017, Citation2020; Schmitz et al., Citation2022; Thoreson, Citation2014).

Against this backdrop of opportunities and significant limitations to activism using social media, it could still be argued that the affordance of self-controlled voice and expression, may still be of great value to communities who are constantly defined by others. In context, where oppressed communities are effectively denied access to traditional public spaces, such as mainstream media, town halls, squares etc. and appearing in public spaces is simply too dangerous; self-controlled social media offers, despite all its limitations, a space to resist symbolic annihilation. In short, when the manifestations of a persecuted community are suppressed in all, or most public spaces, self-controlled social media channels still provide a space to stay symbolically alive and continue to challenge oppression.

Few places offer a more pressing case context than the Ugandan LGBT+ community. As will be described in greater detail, state-sponsored persecution is a colonial legacy introduced by the British colonial power and subsequently expanded by Christian missionaries. Although these past and present norm-entrepreneurial interferences successfully managed to integrate heteronormativity and anti-homosexual sentiments into the social fabric and public opinion, violent hate crime against LGBT+ is of a later date. Hate crimes, such as physical attacks, arrest, blackmail, and hate speech in mainstream media, as well as a range of non-violent crimes appear to have escalated in the wake of the now infamous 2009 Anti-homosexuality Bill (AHB) (Neiman, Citation2019; Sexual Minority Uganda, Citation2016). The next to universally unfavourable public opinion on LGBT+ that emerged in the early 2000s (Dionne & Dulani, Citation2020), provided strong support to the lawmakers to move from low-intensity persecution to high-intensity persecution, by expanding criminalization and turning a blind eye toward extra-judicial enforcement of the laws.

Risks connected with conducting LGBT+ rights advocacy increased significantly during 2022, when the Ugandan Government shut down the country’s largest LGBT+ organization Sexual Minority (SMUG), raided LGBT+ organizations offices, and closed down several other LGBT+ organizations (NGO Bureau Citation2020). In 2023, the situation deteriorated further with the passing of the 2023 Anti-homosexuality Act. The passing of the 2023 Anti-homosexuality Act, was motivated using similar arguments as with the Anti-homosexuality Act of 2009. It is an essential tool for protecting Ugandan culture and traditional family norms against international sexual rights activists seeking to impose their values of sexual promiscuity on the people of Uganda and ensure Ugandan sovereignty against Western neo-imperialism (Nyanzi & Karamagi, Citation2015). The Act introduced the new offence of ‘promotion of homosexuality’, which criminalizes all advertisement, publishing, printing, broadcasting, or distribution of material that is ‘promoting or encouraging homosexuality’ (Human Rights Watch, Citation2023). The law thus codifies an earlier trend of silencing and erasing LGBT+ voices in public spaces and media spaces in particular (Strand, Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2018). In short, Ugandan LGBT+ individuals and activist organizations face violent state-sponsored repression, extra-judicial violence and symbolic annihilation, that is, mediated omission, trivialization and condemnation (Tuchman, Citation2000), which leads to invisibility and/or systematic misrepresentation of marginalized voices.

This study was conducted at the cusp of the latest round of intensified repression in 2022 and 2023, where the Ugandan LGBT+ activists still had the legal rights to conduct human rights advocacy in self-controlled social media channels. This study sought to better understand activism in repressive contexts where traditional activism, that is, engaging in raising public awareness, persuading and administering pressure for social change through lobbying, public protests, petitions, and boycotts are futile or even likely to intensify hostilities. As the fast shrinking of space and intensified repression in Uganda is the result of a set of intersecting logics, which here is referred to as the logics of oppression, this study sought to explore if self-controlled social media could be used for what could be called foundational work, that is challenging the grounds upon which violent persecution is rationalized? Furthermore, the logic, which will be described in greater detail in the subsequent text, briefly consists of heteronormativity, same-sex desires as incompatible with Christian morality, and LGBT+ rights constitute a form of Western imperialism, are intertwined and indeed dependent on selective remembrance of the past century’s targeted erasure of sexual and gender expressions outside the heteronormative paradigm. Post-colonial amnesia pertaining to the etiologies of the structures that today normalize and perhaps even prescribe oppression of LGBT+ is a key facilitator of the logic. The purpose of this paper is to understand to what degree is self-controlled social media spaces used for exposing and challenging the local logic of oppression, as well as the post-colonial amnesia that enables the logic.

Understanding the logic of oppression in Uganda

The logic of oppression is the result of a century of foreign norm-entrepreneurial influences targeting Ugandan social mores on sexuality. A norm-entrepreneur is an entity, such as an individual, non-governmental organization, state, and/or trans-national organization, that by targeted interventions attempt to alter social norms (Sunstein, Citation1996), and seek to move the norm from initial introduction to norm internalization (Finnemore & Sikkink, Citation1998). The logic rationalizes contemporary oppression of non-conforming sexual desires and gender expressions and provides legitimacy for contemporary actors’ homo-hostilities and widespread indifference to the community’s experiences and suffering. Due to space constraints and the time frame of a plus hundred years, the following sections can only cover them in large brush strokes.

First wave of intimate colonization – 1890s–1962

Before the British invasion, there appeared to have existed a degree of acceptance of non-conforming sexualities and non-conforming gender expressions (Hoad, Citation2007; Tamale, Citation2007).

Several pre-colonial communities showed varying degrees of acceptance of sexual pluralism, age-differentiated homosexuality and gender fluidity, even if these were never labelled homosexual, or even noted at all (Hoad, Citation2007). Although same-sex practice and gender-fluidity may have not been ‘neither fully condoned nor totally suppressed’ (Tamale, Citation2007, p. 18); it appears that pre-colonial Uganda accepted certain expressions outside the heteronormative paradigm.

With the arrival of Muslim traders and European Missionaries, as well as a growing British colonial administration, pre-colonial sexual practices came under attack. The colonial administration began cooperating with the missionaries that had proliferated quickly throughout the colony (Summers, Citation1991). The colonial administration embraced the missionaries’ social purity campaigns which rejected same-sex desires and non-procreational sexuality, and supported efforts to re-design and align sexual norms with the missionaries’ patriarchal heterosexist world order, hoping it would secure higher fertility rates and thus ensure a steady flow of able bodies for the colonial economy. Early missionaries’ social engineering efforts focused on promoting the Victorian ideals of civilized sexuality, which prescribed childbearing inside a nuclear family setting. The marriage of convenience of the secular needs of colonial rulers and Christian missionaries successfully managed to establish a heteronormative hegemony, i.e., constructing ‘heterosexuality as natural and superior to all other expressions of sexuality’ (Robinson, Citation2016, p. 1). and convince the colonial subject that it was ‘uniquely African’ (Thoreson, Citation2014, p. 16). The first round of norm-entrepreneurs’ successful introduction of heteronormativity should, however, not be understood in isolation. Children are seen as key to the survival of the majority of Bugandans’ community/clan/nation (Boyd, Citation2013). The Ugandan norms of ekitiibwa, outlining the individual’s interdependence and obligation to others within the clan/community and empiisa, defined as good manners with to respect for parents, elders, and the clan/community are helpful to understand the internalization of heteronormativity (Karlström, Citation1996). Historically, ekitiibwa and empiisa have provided some level of freedom for individuals with same-sex desires. Same-sex adventures could be overlooked and not even considered as acts defining you as a homosexual, as long as they did not interfere with social obligations of reproduction and remained hidden from public view.

In the last years of the nineteenth century, the colonial administration codified the heteronormative script and introduced section 145 into the criminal code. Through section 145, state-anctioned repression of ‘unnatural offences’ or sodomy in the British colonies became part of the imperial project of civilizing the ‘natives’, as ‘native’ cultures did not punish ‘perverse’ sex enough (Human Rights Watch, Citation2008, p. 5). At the time of independence in 1962, the first logic of oppression – heteronormativity – appears to have been firmly internalized, and Section 145 is kept in the otherwise revised criminal code.

The second and still ongoing wave-missionaries of hate

Despite the first wave actors’ concerted norm-entrepreneurial efforts, most Ugandans had a relatively relaxed attitude to same-sex activity as long as it didn’t interfere with responsibilities to ensure the family linage, as well as remained hidden from public view, until the first years of the new Millennium (Lusimbo & Bryan, Citation2018; Tamale, Citation2009). Contemporary homo-hostilities cannot be understood without acknowledging the influence of American conservative churches’ active norm-entrepreneurial efforts in Uganda, and indeed Africa (Kaoma, Citation2013). Ultra-conservatives Americans, successfully convinced receptive Ugandan Pentecostal pastors, that Ugandan traditional sexual morality, as taught by the first Christian missionaries and Christian family values was under attack by a rich and amoral Western ‘gay lobby’ (Ward, Citation2015). Against the backdrop of an emerging moral panic around sexual morality, second-wave actors in collaboration with domestic stakeholders, successfully secured wide public support for the notion that same-sex desires were entirely ‘incompatible with being a good Ugandan and a good Christian’ (Ward, Citation2015, p. 137). Contemporary evangelist emphasises that same-sex desire and non-conforming gender expressions were an abomination to God, and constituted Un-godly acts, but with the addition that these social ills were the result of Western neo-imperialism, poorly veiled as ‘development’. By framing same-sex desires as un-Godly and un-African, missionaries of hate were able to tap into post-colonial anxieties and drum up strong public support (Kaoma, Citation2013; Ssebaggala, Citation2011), for the second logic of oppression – same-sex desires are un-godly and thus incompatible with Christian morality.

The first and second waves of norm-entrepreneurs had by the first decade of Millennium both successfully replaced pre-colonial queerer sexual mores with heteronormativity, and created acceptance for the notion that same – desires were incompatible with Christian teachings on morality, as well as convinced enough citizens to accept the logics of oppression as genuine expressions of Ugandan culture, rather than a legacy of multiple foreign norm-entrepreneurs social engineering efforts. Ugandan scholar Tamale (Citation2013, p. 36) concludes that ‘ … it is not homosexuality that was exported to Africa from Europe, but rather legalized homophobia that was exported in the form of Western codified and religious laws’. The erasure of the etiology of institutionalized homophobia from the collective consciousness warrants the diagnosis of post-colonial amnesia. The post-colonial amnesia constitutes a key enabling condition for the logic of oppression.

The third logic of oppression – rejection of Western imperialism, cannot be understood fully without analyzing a third and still ongoing wave of normative influence coming from trans-national LGBT+ rights advocacy networks and development partners. The development industry’s shift in policy and practices is likely to have unwittingly contributed to the framing of Ugandan LGBT+ as a form of Western imperialism.

The third wave – universal sexual rights, homo-developmentalism and homo-colonialism

In the first decade of the 2000s, sexual rights outside the heteronormative paradigm started to become integrated into the international human rights paradigm. The shift, brought on by the HIV pandemic (Corrêa et al., Citation2008; Stein, Citation2012) and national and transnational LGBT+ activism (Aylward, Citation2020; Langlois, Citation2020) had a significant impact on development policy and programmatic responses. Klapeer (Citation2018, p. 102) argues that development actors went through ‘major organizational, legal and discursive shifts in the visibility and acknowledgement’ of LGBT+ rights in development policies and practices in the past decade. Today, sexual rights have become a prominent feature of a Western human rights-based development agenda (Mason, Citation2018), where LGBT+ rights are formally and rhetorically linked to modernization and civilization (Ayoub & Paternotte, Citation2020; Slootmaeckers, Citation2020). The concept of ‘homo-developmentalism’ attempts to capture the aforementioned shift where LGBT+ rights are seen as both an indicator of progress and a goal of development, in development policy and practices (Yang, Citation2020), as well as constitutes a responsibility for development partners (Klapeer, Citation2018). The shift in global development policy and practice has resulted in not only discursive recognition of LGBT+ rights but a significant increase in financial support for LGBT+ activism around the world (Global Philanthropy Project, Citation2021). The Ugandan LGBT+ community has, for example, been a prioritized recipient of earmarked LGBT+ rights funding over the past ten years (Global Philanthropy Project 2013–2021). The Community has mushroomed from 24 LGBT+ organizations in 2012 (Nyanzi, Citation2013), to over a hundred ten years later (SMUG membership list 2021).

Albeit the queering of development policy and practices is motivated by a desire to expand human rights to sexual minorities across the world, development partners’ efforts could be argued to constitute neo-colonialism through a diffusion of norms and concepts (Rahman, Citation2014).

Western development partners and transnational LGBT+ rights advocacy networks often lack knowledge of local conceptualizations of non-conforming sexuality and gender identity and/or gender expression (Aylward, Citation2020). Rahman (Citation2014, p. 275) argues that when LGBT+ rights are used in a neo-colonialist fashion to label certain countries and cultures, not only as lagging behind but also inferior, barbaric and under-developed, as well as in need of corrective support, it should be considered ‘homo-colonialism’.

Western understanding of LGBT+ rights historically emanates from Western identity constructs (Msibi, Citation2011), which departs from an essentialist understanding of sexual orientation, i.e., a notion that individuals occupy an innate biologically determined and stable subject position (DeLamater & Hyde, Citation1998). Msibi (Citation2011) argues that because Western labels, such as ‘gay’ and ‘homosexual’, are products of a specific context, and thus have their own separate historical Raison d'être; they have no innate meaning in Africa. The etiology of the term ‘sexual minority’ can be traced back to Western LGBT+ rights campaigners’ strategic decision to link and take advantage of existing anti-discrimination laws to ensure minority rights-based protections within national legal frameworks (De Vos, Citation2015). Western human rights discourses can result in universalizing Western epistemologies on sexualities while silencing others or labelling them as barbaric/un-liberated, especially sexually fluid individuals who do not fall neatly under the mono-sexuality paradigm, and the binary confines of lesbian vs. gay, straight vs. gay identity categories (Ali, Citation2017).

Uganda has directly experienced the development partners and trans-national actors resolve to try to influence the legislative process around the 2009 Anti-homosexuality Bill. Bilateral and multi-lateral development partners, international human rights organizations, and trans-national LGBT+ rights advocacy networks (Nyanzi & Karamagi, Citation2015; Saltnes & Thiel, Citation2021) unleashed an avalanche of criticism and threatened to cancel existing development programmes (Saltnes & Thiel, Citation2021). Uganda was told that enactment of the proposed Bill would have a serious negative impact on inter-state relations. International actors’ heavy-handed interferences in domestic politics were met by defiance by Ugandan political and religious elites (Nyanzi & Karamagi, Citation2015), and trans-national LGBT+ activists and international development partners’ moral and financial support to the embattled Ugandan LGBT+ community, is likely to have contributed to the third logics of oppression – LGBT+ rights constitutes a form of Western imperialism, and local LGBT+ organizations are Western imperialist puppets.

Summing up the local logic of oppression

The elements of the logic of oppression – heteronormativity, same-sex desires as incompatible with Christian morality, and LGBT+ rights constituting a form of Western imperialism, are all dependent on a society-wide post-colonial amnesia. Post-colonial amnesia enables, protects and sustains the logic of oppression from serious challenge.

Against this backdrop, where the logic of oppression makes the Ugandan public largely unreceptive to LGBT+ rights advocacy and supporters unable to materialize physically or virtually to show support and/or engage in collective action; this study seeks to explore, if and how Ugandan LGBT+ organizations take advantage of their social media’s affordances of unrestricted voice to expose and challenge the past and present international norm entrepreneurs’ (across the spectrum) influence on Ugandan sexual mores. Does Ugandan LGBT+ activists use their self-controlled spaces to challenge the colonial legacy and the relics they left behind, which in extension renders their own existence, experiences and suffering, inconsequential in the eyes of most Ugandans? That is, in a context where the space for traditional activism is limited and fast shrinking, are self-controlled social media spaces put to use to support what can be called insurgent foundational work, such as challenging the very premises and structures that rationalize and enable oppression.

Methods and material

A mixed-methods approach, consisting of a directed content analysis of Twitter and Facebook, and semi-structured interviews with four content producers, servicing five Ugandan LGBT+ organizations, was used.

Sampling and material

Due to the mushrooming of LGBT+ organizations and that an unknown number is suspected to be so-called brief-case organizations (Interview, SMUG Director, Kampala, January 2022); a selection of organizations was necessary. Three criteria were constructed to identify the organizations that could be expected to have acumen the maturity and capacity to challenge the logic of oppression and post-colonial amnesia, as well as do so from different vantage points. Five organizations fulfilled the following criteria for inclusion ().

An understanding of the logic of oppression and post-colonial amnesia, is likely to be of such a complex nature it requires years of experience within the space LGBT+ activism to grasp, only organizations having existed for more than ten years were eligible.

Active use of social media is a precondition to developing the skills to take full advantage of their affordances. Only organizations that posted at least once a week on both Facebook and Twitter were eligible

Organizations conduct advocacy from different vantage points, such as feminism, queer, public health etc. which is likely to have implications for the issues they pursued in their self-controlled spaces. Efforts were thus made to have the sample reflect some of the heterogeneity that exists in the community such as primary target groups, size in terms of staff and funding.

Semi-structured interview with social media content producers

Four semi-structured interviews with content producers were carried out in Kampala in April 2023. The interviews were held two weeks after the passing of the 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Bill that threatened to criminalize all LGBT+ rights advocacy. It should be noted that the closing of the largest LGBT+ organizations SMUG in August 2022, and the first passing of the Anti-homosexuality Bill in March 2023, impacted the interviews. The uncertainty in terms of how to interpret the proposed clause on promoting homosexuality had a noticeable chilling effect on the community and interviewees. Interviews lasted for approximately 60 min and were not recorded as it would have resulted in significant difficulties in recruiting participants. Copious notes were, however, taken during the interview. The interviews probed broadly into the role of social media in organizational efforts, as opposed to suggesting that they should be used in a particular manner. Furthermore, to protect the anonymity of the participants, individual statements will not be tied to a particular organization.

Table 1. Selected Ugandan LGBT+ organizations.

Social media sample

Even if less than 10 per cent of the Ugandan population uses the internet, Facebook and Twitter regularly (Datareportal Citation2023), the content producers all attest to the importance of Twitter and Facebook, albeit the latter’s influence has lessened. Facebook was blocked by the Ugandan Government as of the 2021 elections, because of its move to de-de-platform hundreds of accounts that could be linked to the ruling party National Resistance Movement’s disturbance to the elections. Although Facebook can be and is accessed through a VPN service, the ban lessens the platform’s relevance. The selected LGBT+ organizations all have an active presence on Facebook but are significantly more active on Twitter. The content producers all attested that Twitter is the primary social media in Uganda.

A low-intensity advocacy period was chosen to avoid analyzing a month with a pre-set and highly skewed advocacy agenda, such as, for example, IDAHOBIT in May, Pride, in June. January was selected, as it is the month for relaunching the organizations’ charted direction and commitments to stakeholders and supporters. The selected organizations generated 55 Facebook and 135 Twitter entries in total.

Analysis

As the purpose of this study is to explore the engagement with a particular topic, as opposed to exploring content more broadly; a directed content analysis was chosen. A directed approach to content entails engaging with material drawing conceptually on specific prior research and/or theories, including the theories’ variables of interest and/or key conditions (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Directed content analysis has also been referred to as deductive category development and application (Mayring, Citation2000), where theory and/or prior research predetermine the codes.

The analysis followed a multi-step process. The first step consisted of a reiterative reading of the entire dataset to identify entries that include a reference to the following material: past or current foreign norm entrepreneurs, central normative discursive material, such as heteronormativity, prescriptive religious doctrines related to sexuality, universal sexual rights, and LGBT+ rights, and finally, processes de-establishing or sustaining the logics of oppression, such as evangelization of conservative interpretations of Christianity, de-colonialization, post-colonialism. In the second step, the social media entries with explicit reference to the aforementioned concepts, and with manifest or latent references to the logic of oppression, and/or their mechanism, and/or post-colonial processes, were analyzed guided by the earlier described logic of oppression framework and post-colonial amnesia. Text and any accompanying image were combined and treated as a communicative unit.

As the sample turned out to be surprisingly small, and the majority of the initial sample was related to third-wave actors and their discursive material; a third step was added. All entries that contained a reference to third-wave actors, and/or their discursive material, used in the third-wave actors’ rhetorical repertoire and in particular the use of a universal sexual rights language rooted in Western essentialist LGBT+ labels, were analyzed using an open interpretative content analysis, exploring a simply question – how are the Ugandan organizations relating to the third wave actors and their discursive material?

Finally, the analysis was supplemented by material drawn from the four semi-structured interviews, where the interview material was used for interpreting and understanding the intentions behind the patterns that had emerged in the various types of content analysis.

Results

With only a handful of examples, it cannot be said the social media platforms’ affordance of voice, was used for challenging the logic of oppression, or the Ugandan public’s convenient post-colonial amnesia. Self-controlled expression was not used for calling attention to a century of foreign norm entrepreneurs’ contribution to the logic of oppression, and impact the wider sphere of public discourse. Nor were spaces used for negotiating their relation to the transnational normative flows introduced by transnational and international development partners, and thereby address their vulnerability by affiliation and close cooperation with Western partners. The analysis did thus not find support for processes of ‘adaptation, hybridizing, or creolizing Western concepts of queerness’, as suggested by Szulc (Citation2020, p. 5) as being a potential outcome of trans-national exchange between nodes in a global network of queer actors. In short, the potential to use spaces for insurgent foundational work, that is, directly challenging the premises for oppression, remained under-utilized.

Even if spaces were not used to challenge the local logic of oppression there were still a handful of noteworthy exceptions, which signalled awareness of the mechanism behind oppression.

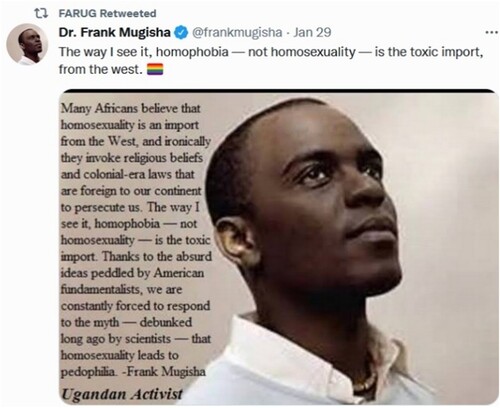

A FARUG re-tweet originating from SMUG director and leading activist, Frank Mugisha () is the most obvious reference to the long history of contemporary state-sanctioned homophobia and society-wide discrimination. This single entry highlights the roots of contemporary homophobia, that is, colonialism and religious fundamentalism, but does not call attention to that these processes also erased a pre-colonial queer Uganda.

Another re-tweet, on the 27th of January, displays a political cartoon-like-image of three angry white men, which bear a striking resemblance with the American pastors who contributed significantly to the wording and launch of the 2009 AHB (Oliver, Citation2013). The three pastors are beating a rainbow flag-clad body bloody. The caption reads: If YOUR RELIGION MAKES YOU HATE SOMEONE YOU NEED A NEW RELIGION. The image thus contains explicit references to contemporary foreign religious actors as instigators of violent homophobia. The tweet does not call attention to past Christian missionaries’ role in introducing Christian morality and laying the foundation for two of the logics of oppression, but the violence their interpretation of the Bible instigates is clearly conveyed.

Another entry, and the only example in the Facebook set, contains the text; ‘I do not see how two people who are in a loving relationship and harming no one, pose a threat to family simply because they happen to be of the same sex. The argument that homosexuality is a threat to the continuity of humankind and that it will lead to the extinction of human beings in the world simply does not hold water because there are too many heterosexuals in the world for that to become a reality’. (SMUG, 11th January 2022). The post is accompanied by an illustration of a Jesus-looking man holding a rainbow flag, and a sign with the text ‘BORN THIS WAY’. The post challenges the notion that oppression is warranted as a mode to secure reproduction and clan survival, which are key aspects of the Ugandan social contract between the individual and the community, as well as the religious duty to populate the earth. Furthermore, the illustration challenges that the oppression of LGBT+ is sanctioned by God and rather evokes the Story of Creation.

A more subtle contestation is a second re-tweet originating from Ugandan LGBT+ activist, Frank Mugisha, which appears in both FARUG and SMUG’s Twitter feeds. The tweet contains a picture of Frank Mugisha sitting in what appears to be an interview setting, with a camera directed at him; quoting him saying ‘Homosexuality is African ’ (SMUG 25th Jan, 2022; FARUG 25th Jan., 2022). Being Ugandan, the imagery challenges that oppression of Ugandan LGBT+ can be rationalized because they are exogenous to Africa and Uganda.

The analysis also explored how the Ugandan LGBT+ organizations engaged with and related to transnational LGBT+ rights advocacy networks and international development partners as well as their normative influence. This sample contained two broad categories: spotlights relationships and show discursive affinity. A considerable number of entries displayed or even flaunted cooperation with trans-national LGBT+ rights advocacy networks, and multi-lateral and bilateral development partners. Post/tweet would name and tag international partners and publish a statement of gratitude for their financial support. A second type of entry consisted of showcasing affinity to third-wave actors’ discourses, by promoting the universal sexual rights paradigm, supporting international sexual rights campaigns, endorsement of international processes, and participatng in international activism calendar event. In bothcategories, Ugandan actors used Western self-referencing labels as LGBT+ to refer to Ugandans with same-sex desires and non-conforming gender identities.

Despite that affiliation with the third-wave actors, in particular, after the international community’s clamp-down in connection with the 2009 AHB, makes Ugandan actors more vulnerable to repression; none of the entries problematized cooperation or the uncritical adoption of discursive material.

The semi-structured interviews provided some insights into the silence on the relationship between the third-wave actors and the logic of oppression although interviewees were never explicitly asked about the logic of oppression or even post-colonial amnesia. The content producers appeared to argue that although the social media platforms were greatly valued for their affordance of self-controlled voice, in particular, pertaining to information and news Ugandan media would never publish; spaces were even more valued for their support to fundraising efforts. The content producers all explained that given the economic realities of local activism and indeed activists, fundraising constitute a core activity for the organizations and all the activist. Once you have become an activist, your chance of securing a job with a local employer is limited. Fundraising is a strategic priority and social media platforms are used for the continuous management of important donor relations and the cultivation of new ones. One interviewee states that social media is used for showing funders that grants are used ‘correctly’. One content producer explains that self-controlled spaces are a key space for curating the organizations’ image towards international audiences, and provide international allies with a sense of a constant flow of activity. Showing activity and results strengthens the organization’s legitimacy. One interview appears to regard the organization’s Twitter as an activity log, that provides funders with real-time reporting.

Given the dependency on international funding from development partners and transnational LGBT+ actors, it may be unrealistic to problematize the third-way actors’ influence in Uganda. Cognizant of this aspect of the political economy of local LGBT+ rights activism, the content analysis also explored to what degree Ugandan LGBT+ actors engaged in more subtle forms of detangling themselves from the logic of oppression on grounds of being Western imperialist. One mode of detangling and decoupling could take the shape of reviving and using local terms for self-referencing, such as kuchu, which can roughly be translated into “queer”, albeit embedded in local codes of conduct when it comes to sexuality, reproductoin and community (Peters, Citation2014).

Despite the existence of a local term kuchu, the Western lexicon for self-refencing such as homosexual, LGBT+, or variations of the acronym, sexual minority/ies, gay or queer is the lingua franca and dominate the five organizations’ social media content. Kuchu/s is only used in connection with a single event, The Annual Kuchu Remembrance Day. In 2020, the Ugandan LGBT+ community launched the 26th of January as the annual Kuchu Memorial Day, to honour the legacy of murdered activist David Kato Kisule. Four organizations spotlight the Kuchu Memorial Day either by creating their own content and/or by re-posting and/or re-tweeting SMUG’s initial invitation on both Twitter and Facebook. This event constitutes the only example where the Ugandan LGBT+ community engage in circulating local discursive material, which might influence the centre nodes, as envisioned by some scholar (Szulc, Citation2020). The material contained no manifest or latent references to post-colonial amnesia and its role in sustaining the logic of oppression.

Although the non-confrontational strategy towards the third-wave actor influences and dominance of activity reporting appears to be primarily justified by financial necessities, it does not fully explain the minimal engagement with the logic of oppression emanating from the first two waves. The content producers’ understanding of who their audiences are, does, however, provide additional pieces to the puzzle. When asked who they think they actually reach through their public social media channels, the content producers list donors, international and local allies, local NGOs/CBOs outside the LGBT+ sphere, and local members. The content producers, although managing public accounts, appear to regard them as a space for a like-minded community. In this networked international community of like-minded, there is limited value in rehashing the logic of oppression and the post-colonial amnesia that enables it.

Discussion

Uganda has been exposed to foreign norm-entrepreneurs’ intimate colonialization in the past century, resulting in the successful erasure of queerer pre-colonial sexual mores and the entablement of a set of logics that rationalizes the oppression of LGBT+ individuals – the logic of oppression. Contemporary political and religious elites have subsequently taken advantage of their monopoly of key discourse-producing institutions, such as the legislative arena, traditional media and faith-based organizations, to circulate, promote and implement their doctrine of hate. In the pre-digital landscape, Ugandan LGBT+ activists had limited opportunities to expose and challenge the logic of oppression or the post-colonial slumber that sustains it. This study explored to what degree self-controlled social media spaces were used for exposing and challenging the logic of oppression and post-colonial amnesia.

This study was carried out before the 2023 Anti-homosexuality Act, when radical LGBT+ rights activism was still legal. But despite the opportunities to engage in insurgent foundational work, that is expose and challenge the core premises for oppression, this study found that Ugandan actors remained largely silent on this particular topic. Although the material contained a few instances where actors engaged with the logic of oppression the number of entries is too low to arguably make an imprint in an increasingly ‘noisy information environment’, (Guo & Saxton, Citation2018).

Instead, social spaces appeared to primarily be used as an arena to fundraise and maintain donor relations, which includes strategically broadcast affiliation and affinity with the global LGBT+ community and its universal sexual rights paradigm. The studied organizations used a conspicuously uniform Western human rights language on both Facebook and Twitter to refer to themselves, promote activities and services, spotlight upcoming local and/or international events, as well as report on funded activities. Social media affordances of unrestricted voice are thus used to facilitate the circulation of transnational international allies and development partners’ universal sexual rights rhetoric, despite the risks of increasing the local community’s vulnerability to accusations of being neo-colonial stooges. The results thus appear to echo previous findings where activists from the Global South and East tend to strategically adopt the languages of development institutions to access support (Lind, Citation2010).

Although the Ugandan LGBT+ organizations’ lack of engagement with the logic of oppression, including the role of international development partners’ influences, could be interpreted as a lack of ambition to engage in de-colonialization efforts, we would argue against that interpretation of the result. Rather the results highlight the importance of recognizing the political economy of activism when analyzing social media spaces’ potential to contribute to activism. Based on the findings from this study, it would be possible to, provocatively argue that the social media affordance of Voice, is conditioned upon the marginalized group having enough resources to engage in the pedagogy of the oppressed, which is seldom the case for LGBT+ activists in the Global South, and Uganda is no exception.

Finally, it could be argued that transnational LGBT+ rights advocates and development partners also have a responsibility to challenge and support donor-dependent actors to use their voice creatively and take full advantage of the social media affordance of voice. Although such efforts may get messy and lead to the occasional discomfort for international partners when such endeavours impact and challenge the organizations’ priorities, practices, rhetorical toolbox and self-image it is in both parties’ long-term interests. Hopefully, this research can contribute to transnational LGBT+ rights actors’ and development partners’ self-reflexive assessment of how funding priorities, appraisal frameworks, and decision-making processes, as well as monitoring and evaluation systems, may impact recipients’ freedom to explore alternatives to the Western discursive influences.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the interviewees in Uganda that generously shared their perspectives and experiences, at a time when the now-passed Anti-homosexuality Act of 2023, was casting a menacing shadow.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cecilia Strand

Cecilia Strand (Ph.D.) is a media and communication researcher based at Uppsala University, Sweden. Her research interests span LGBT+ activism and their digital media practices in repressive contexts, international sexuality politics, well as anti-gender movement actors norm-entrepreneurial activities across contexts. Her multi-disciplinary work draws broadly on the fields of digital media studies, activism, development studies, and gender studies. Prior to academia, she worked as a development practitioner spending eight years in three different Sub-Saharan African countries.

Jakob Svensson

Jakob Svensson (Ph.D.) is a full professor in media and communication studies at Malmö University, Sweden. He obtained his PhD from Lund University, Sweden on a dissertation on civic communication. For his associate professorship, he worked in the area of political communication online and developed a theory of Network Media Logic with Ulrike Klinger. Today his research interests include (digital) media and empowerment, as well as programmers and tech cultures. He has also worked extensively in Uganda, conducting research together with the LGBT+ community.

Notes

1 Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, where the plus represents all non-conforming sexualities and gender identities and expressions, as well as heterosexual allies to the struggle for equality

References

- Ali, M.-U. A. (2017). Un-mapping gay imperialism: A postcolonial approach to sexual orientation-based development. Reconsidering Development, 5(1).

- Amtzis, R. (2014). Crowdsourcing from the ground up: How a new generation of Nepali nonprofits uses social media to successfully promote its initiatives. Journal of Creative Communications, 9(2), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973258614528609

- Aylward, E. (2020). The development of NGOs focused on LGBT issues. In The Oxford handbook of global LGBT and sexual diversity politics (pp. 103.

- Ayoub, P., & Paternotte, D. (2020). Europe and LGBT rights: A conflicted relationship. In M. Bosia, Sandra M. McEvoy, & M. Rahman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of global LGBT and sexual diversity politics (pp. 153- 168). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Boyd, L. (2013). The problem with freedom: Homosexuality and human rights in Uganda. Anthropological Quarterly, 86(3), 697–724. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2013.0034

- Cammaerts, B. (2015). Social media and activism. Journalism, 1027–1034.

- Ciszek, E. (2017). Activist strategic communication for social change: A transnational case study of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender activism. Journal of Communication, 67(5), 702–718. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12319

- Ciszek, E. (2020). Diffusing a movement: An analysis of strategic communication in a transnational movement. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 14(5), 368–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2020.1835919

- Corrêa, S., Petchesky, R., & Parker, R. (2008). Sexuality, health and human rights. Routledge.

- Currier, A., & Moreau, J. (2016). Digital strategies and African LGBTI organizing. In Digital activism in the social media era (pp. 231–247). Springer.

- Datareportal. (2023). Digital 2023: Uganda. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-uganda?rq=uganda (Accessed 31 Aug. 2023).

- DeLamater, J. D., & Hyde, J. S. (1998). Essentialism vs. social constructionism in the study of human sexuality. Journal of sex Research, 35(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499809551913

- De Vos, P. (2015). Mind the gap: Imagining new ways of struggling towards the emancipation of sexual minorities in Africa. Agenda (durban, South Africa), 29(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2015.1015240

- Dionne, K. Y., & Dulani, B. (2020). African attitudes toward same-sex relationships, 1982–2018. In Oxford research encyclopedia of politics.

- Edenborg, E. (2020). Visibility in global queer politics. In The Oxford handbook of global LGBT and sexual diversity politics (pp. 349.

- Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). International norm dynamics and political change. International Organization, 52(4), 887–917. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081898550789

- Fuchs, C. (2021). Social media: A critical introduction. Social Media, 1–440.

- Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Tweets and the streets: Social media and contemporary activism. Pluto Press.

- Global Philanthropy Project. (2021). Global Resources Report 2019/2020- Government and Philanthropic Support for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex Communities. https://globalphilanthropyproject.org/.

- Guo, C., & Saxton, G. D. (2018). Speaking and being heard: How nonprofit advocacy organizations gain attention on social media. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764017713724

- Hoad, N. W. (2007). African intimacies: Race, homosexuality, and globalization. U of Minnesota Press.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Human Rights Watch. (2008). This alien legacy the origins of “Sodomy” laws in British colonialism. Printed in the United States of America.

- Human Rights Watch. (2023). Ugandan parliament passes extreme anti-LGBT bill- President should reject bill, stop systemic oppression [Press release]. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/03/22/ugandan-parliament-passes-extreme-anti-lgbt-bill.

- Hutchinson, J. (2021). Micro-platformization for digital activism on social media. Information, Communication & Society, 24(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1629612

- Kaoma, K. (2013). The marriage of convenience: The US Christian Right, African Christianity, and postcolonial politics of sexual identity. Global Homophobia: States, Movements, and the Politics of Oppression, 75–102.

- Karlström, M. (1996). Imagining democracy: Political culture and democratisation in Buganda. Africa, 66(4), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.2307/1160933

- Klapeer, C. M. (2018). Dangerous liaisons?: (Homo) developmentalism, sexual modernization and LGBTIQ rights in Europe. In Routledge handbook of queer development studies (pp. 102–118). Routledge.

- Langlois, A. J. (2020). Making LGBT rights into human rights. In M. J. Bosia, S. M. McEvoy, & M. Rahman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of global LGBT and sexual diversity politic. Oxford University Press Oxford.

- Lind, A. (2010). Development, sexual rights and global governance. Taylor & Francis.

- Lusimbo, R., & Bryan, A. (2018). Kuchu resilience and resistance in Uganda: A history. Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library, 323.

- Mason, C. L. (2018). Introduction to Routledge handbook of queer development studies. In Routledge handbook of queer development studies (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Paper presented at the Forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum: qualitative social research.

- Msibi, T. (2011). The lies we have been told: On (homo) sexuality in Africa. Africa Today, 58(1), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.58.1.55

- Mutsvairo, B. (2016). Digital activism in the social media era: Critical reflections on emerging trends in sub-saharan Africa. Springer.

- Neiman, S. (2019, 21 Nov. 2019). Uganda’s escalating LGBT crackdown feels eerily familiar. World Politics Review. https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/28364/uganda-s-escalating-lgbt-crackdown-feels-eerily-familiar.

- Ng, E. (2017). Media and LGBT advocacy: Visibility and transnationalism in a digital age. In The Routledge companion to media and human rights (pp. 309–317). Routledge.

- NGO Bureau. (2022). Statement on halting the operations of Sexual Minorities Uganda. The National Bureau for Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO Bureau). https://ngobureau.go.ug/en/news-and-notices/statement-on-halting-the-operations-of-sexual-minorities-uganda (Accessed 31 Aug. 2023).

- Nyanzi, S. (2013). Dismantling reified African culture through localised homosexualities in Uganda. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 15, 952–967.

- Nyanzi, S., & Karamagi, A. (2015). The social-political dynamics of the anti-homosexuality legislation in Uganda. Agenda (durban, South Africa), 29(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2015.1024917

- Oliver, M. (2013). Transnational sex politics, conservative Christianity, and antigay activism in Uganda. Studies in Social Justice, 7(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v7i1.1056

- Oluoch, A., & Tabengwa, M. (2017). LGBT visibility: A double-edged sword. State Sponsored Homophobia. Retrieved from Geneva.

- Peters, M. M. (2014). Kuchus in the balance: Queer lives under Uganda's anti-homosexuality bill. Northwestern University.

- Rahman, M. (2014). Queer rights and the triangulation of Western exceptionalism. Journal of Human Rights, 13(3), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2014.919214

- Reid, G. (2020, 17th May 2020). A global report card on LGBTQ+ rights for IDAHOBIT. The Advoacte.

- Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the screen. Yale University Press.

- Robinson, B. A. (2016). Heteronormativity and homonormativity. In The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of gender and sexuality studies (pp. 1–3).

- Saltnes, J. D., & Thiel, M. (2021). The politicization of LGBTI human rights norms in the EU-Uganda development partnership. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59(1), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13141

- Saxton, G. D., & Wang, L. (2014). The social network effect: The determinants of giving through social media. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(5), 850–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764013485159

- Schmitz, R. M., Coley, J. S., Thomas, C., & Ramirez, A. (2022). The cyber power of marginalized identities: Intersectional strategies of online LGBTQ+ Latinx activism. Feminist Media Studies, 22(2), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1786430

- Sexual Minority Uganda. (2016). “And that’s how i survived being killed” Testimonies of human rights abuses from Uganda’s sexual and gender minorities. Retrieved from Kampala, Uganda.

- Slootmaeckers, K. (2020). Constructing European Union identity through LGBT equality promotion: Crises and shifting othering processes in the European Union enlargement. Political Studies Review, 18(3), 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929919877624

- Ssebaggala, R. (2011). Straight talk on the gay question in Uganda. Transition, 106(1), B-44–B-57.

- Stein, M. (2012). Rethinking the gay and lesbian movement. Routledge.

- Strand, C. (2011). Kill bill! Ugandan human rights organizations’ attempts to influence the media's coverage of the anti-homosexuality bill. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 13(8), 917–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.589080

- Strand, C. (2012). Homophobia as a barrier to comprehensive media coverage of the Ugandan anti-homosexual bill. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(4), 564–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.665679

- Strand, C. (2018). Cross-media studies as a method to uncover patterns of silence and linguistic discrimination of sexual minorities in Ugandan print media. In Exploring silence and absence in discourse (pp. 125–157). Springer.

- Summers, C. (1991). Intimate colonialism: The imperial production of reproduction in Uganda, 1907-1925. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 16(4), 787–807. https://doi.org/10.1086/494703

- Sunstein, C. R. (1996). Social norms and social roles. Columbia Law Review, 96(4), 903. https://doi.org/10.2307/1123430

- Szulc, L. (2020). Queer globalization and the media. In The international encyclopedia of gender, media, and communication (pp. 1–9.

- Tamale, S. (2007). Out of the closet: Unveiling sexuality discourses in Uganda. In Africa after gender (pp. 17–29.

- Tamale, S. (2009). A human rights impact assessment of the anti-homosexualy Bill. Public Dialogue 18 November 2009, at Makarere University in Uganda’s Anti-homosexuality Bill-the Great Divide. Retrieved from http://pambazuka.org/en/category/features/61423.

- Tamale, S. (2013). Confronting the politics of nonconforming sexualities in Africa. African Studies Review, 56(2), 31–45.

- Thoreson, R. R. (2014). Transnational LGBT activism: Working for sexual rights worldwide. U of Minnesota Press.

- Treem, J. W., & Leonardi, P. M. (2013). Social media use in organizations: Exploring the affordances of visibility, editability, persistence, and association. Annals of the International Communication Association, 36(1), 143–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2013.11679130

- Trillò, T. (2018). Can the subaltern tweet? Reflections on Twitter as a space of appearance and inequality in accessing visibility. Studies on Home and Community Science, 11(2), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/09737189.2017.1420404

- Tuchman, G. (2000). The symbolic annihilation of women by the mass media: Originally published as the introduction to hearth and home: Images of women in the mass media, 1978. Springer.

- Ward, K. (2015). The role of the Anglican and Catholic Churches in Uganda in public discourse on homosexuality and ethics. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 9(1), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2014.987509

- Weiss, M. L., & Bosia, M. J. (2013). Global homophobia: States, movements, and the politics of oppression. University of Illinois Press.

- Yang, D. W. (2020). From conditionality to convergence: Tracing the discursive shift in homo-developmentalism. Australian Feminist Law Journal, 46(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13200968.2020.1821459