ABSTRACT

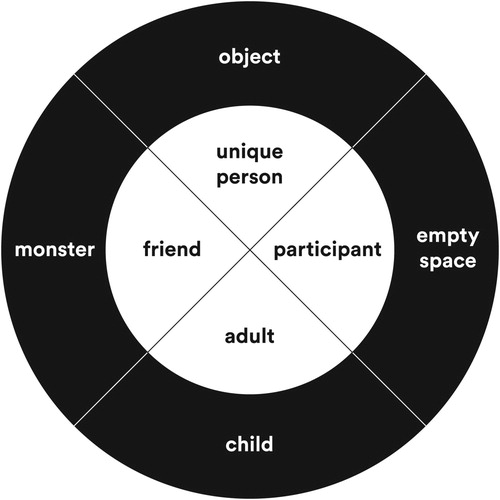

According to the International Federation of Social Workers, social work has always been a human rights profession. However, the legalistic language of human rights is often found to be of limited use in the everyday practice of social workers. This article offers a practical and relatable translation of human rights language by operationalising the central human rights value ‘human dignity’. In the city of Utrecht, The Netherlands, empirical qualitative research was conducted in order to investigate what dignity might entail for social workers and service-users. The study reveals four different ways in which service-users experience their dignity to be violated: being seen or treated as an object, an empty space, a child or a monster. Conversely, social workers and service-users also try to maintain dignity in four ways: by treating people as a unique person, a participant, an adult or a (professional) friend. Together, these modes of dignity violation and dignity promotion form a typology termed ‘the dignity circle’. The dignity circle enables practitioners and policymakers to promote dignity in social work whilst helping them to consider the dilemmas and complexities involved. In this way, the dignity circle provides a practical tool for social work as a human rights profession.

SAMENVATTING

Volgens de Internationale Federatie van Sociaal Werkers is sociaal werk altijd een mensenrechtenprofessie geweest. Het juridisch jargon van de mensenrechten blijkt echter slechts beperkt bruikbaar in de dagelijkse praktijk van sociaal werkers. Dit artikel biedt een praktische en herkenbare vertaling van het mensenrechtenjargon door de centrale waarde die aan de mensenrechten ten grondslag ligt: menselijke waardigheid, te operationaliseren. In de stad Utrecht is er een kwalitatief empirisch onderzoek uitgevoerd met als doel te achterhalen wat waardigheid behelst voor sociaal werkers en cliënten. Het onderzoek onderscheidt vier verschillende manieren waarop cliënten ervaren dat hun waardigheid geschonden wordt, gezien of behandeld worden als: een object, een leegte, een kind of een monster. Sociaal werkers en cliënten, doen er ook van alles aan om waardigheid te behouden, namelijk door mensen te behandelen als: een uniek persoon, een deelnemer, een volwassene of een (professionele) vriend. Gezamenlijk vormen deze vormen van waardigheidsschending en -bevordering een typologie getiteld ‘de waardigheidscirkel’. De waardigheidscirkel stelt professionals en beleidsmakers in staat waardigheid in sociaal werk te bevorderen doordat het hen helpt bij het reflecteren op de complexiteit hiervan en de dilemma’s die optreden. Zo vormt de waardigheidscirkel een praktische tool voor sociaal werk als mensenrechtenprofessie.

Introduction

Public indignation about human rights violations usually arises in relatively extreme cases, such as large-scale oppression or human torture. As a result, human rights are too readily conceived of as civil and political rights, thus being the business of legal and political experts. Less attention is paid to those articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) that concern ‘the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for [one’s] dignity’.Footnote1 These reveal human rights to be at the heart of social work (Healy, Citation2008; Reichert, Citation2007). Human rights, being a central principle of the profession stated in the Global Definition of Social Work (International Federation of Social Workers [IFSW], Citation2014), can be a source of inspiration and commitment for social workers. Yet, as Ife (Citation2007) argues, the language of human rights remains that of experts. The intended recipients of these rights feel no sense of ownership or understanding, nor do social workers who are actually meant to uphold human rights. Moreover, social workers who have to put human rights into practice frequently experience them to be of limited use or guidance in their work (Social Care Institute for Excellence, Citation2013).

Similarly, Utrecht, the first self-proclaimed Human Rights City in the Netherlands,Footnote2 found that the legalistic language of human rights provided little direction for local policy and practice, especially concerning the often highly complex situation of vulnerable groups. Hence, the city approached us to conduct a bottom-up research project, in order to find out what respecting human rights actually means in practice, in particular to members of vulnerable groups and for the social workers that help them. In a collaborative elaboration of this issue, we decided to focus on dignity, and more specifically on experiences of dignity in interactions between service-users and social workers as an important aspect of human rights. This interactional aspect of human rights should be understood as part of its ‘thick needs’ dimension (Dean, Citation2015). Next to crucial ‘thin needs’ that are required for survival and to be guaranteed via material, tangible social rights such as food and shelter, Dean (Citation2015) distinguishes ‘thick needs’ that form a dimension of human rights required for true fulfilment, such as the need to be treated with dignity and respect. Social work as a human rights profession pertains to both securing material rights and the promotion of ‘thick needs’ in everyday life (Vandekinderen et al., Citation2018). It is on the latter that our research is primarily focused.

‘Human dignity’ forms the basis of the UDHR with its first article famously stating that: ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’. However, limiting the issue of human rights to questions of dignity can be risky. Focusing on micro-level interactions may deflect from larger and arguably more important issues. Investigating the meaning of dignity in daily encounters should not replace larger policies aimed at realising the material social rights needed for survival. Social workers need to observe deficiencies in social rights for their clientele and bring them to the attention of politicians and (local) policymakers. This is the kind of work that would suit Jane Addams, Bertha Reynolds and the social workers activists of the 1960s (Healy, Citation2008; Mapp et al., Citation2019). Such social rights are more tangible than more ‘fuzzy’ background values like human dignity.

Still, as Margalit (Citation1996) poignantly shows in his book The Decent Society, getting one’s due is not all that matters. Even when people do receive food and shelter, dignity may be violated in the way food or shelter are granted. Social workers know that living in poverty and hunger may affect people’s dignity, but so can receiving poor relief and food stamps. Hence, we went set out to investigate the meaning of dignity for service-users and social workers on the ground, elaborating the interactional aspect of human rights for social work. In this article, we aim to answer the following research question: how do social workers understand and try to establish dignity for people with multiple-problems in the city of Utrecht, and how do these people experience (violations of) dignity in interaction with social workers?

Method

Research design

This study departs from a constructivist grounded theory approach: sharing with classical grounded theory its inductive, comparative, iterative and emergent nature but prioritising the studied phenomenon and seeing both data and analysis as created from shared experiences and relationships with participants (Charmaz & Belgrave, Citation2012). This approach aims to get as close to empirical reality as possible, acknowledge multiple perspectives and take a reflexive stance towards ourselves as researchers, our informants and our analytical constructions of them (Charmaz, Citation2009). We, therefore, adopted an ethnographic design; observing social workers and service-users, conducting formal and informal interviews and focus groups. Data collection was guided by the following empirical questions: what are experiences of dignity and indignity for people with multiple-problems in the context of care and support? And in what ways do social workers try to establish dignity for people with multiple-problems? While gathering empirical data, we conducted a literature reviewFootnote3 on previous qualitative research on these same questions, regarding vulnerable groups and various practitioners involved in their care, and compared these outcomes to our own findings.

For the empirical research, we worked together with a research partner who had been a service-user herself. Next to playing an important role in the data-collection process the research partner reflected on the data together with the researchers which led to new insights (see also below). User involvement was also sought in the selection of research sites and respondents. Many social work organisations in the Netherlands employ user involvement, for example, regarding psychiatric problems, addiction or poverty (Movisie, Citation2018). Increasingly service-user participants are formally trained as ‘experiential experts’; reflecting on the limitations of their own expertise is included in this training (van der Kooij & Keuzenkamp, Citation2018). Experiential expertise contributes to the diversity of knowledge integrated in the project which has a positive effect on the validity and trustworthiness of the research (Abma et al., Citation2009; Hewlett et al., Citation2006). However, user involvement carries risks as well. Paid service-users might be used to legitimise policies, including policies that would not benefit other (non-professionalised) service-users (Beresford & Carr, Citation2012). Experiences of experiential experts may also become dominant frames of understanding, at the expense of experiences of others. We acknowledge these risks, and so did our experiential expert researcher, with whom we discussed them. We felt that this self-reflective attitude was helpful in avoiding these risks, and also felt that the benefits of additional knowledge outweighed them.

Setting

The research was conducted in the city of Utrecht in the Netherlands, focusing on deprived neighbourhoods. We chose to study dignity for service-users with multiple-problems as they might be most vulnerable to violations of dignity. Their problems include: (chronic) physical or mental disorders, substance abuse, poverty, debt, difficulties with finding or sustaining housing or work and burdensome informal care tasks. For the largest part, the social workers included in this research work with this group at local social care organisations. Others work in generalist neighbourhood teams that have become the dominant way of organising social work in the Netherlands after decentralisation of care to local governments. For the focus group, we approached the adult social care team from the municipal department of public health.

Data collection

Data were collected by the first author from spring 2016 until the end of 2017 in three phases: (1) participant-observation, (2) interviews and (3) focus groups. It was an iterative process whereby each phase informed the next. Before and during this period, the researcher had informal conversations with numerous key informants, including municipal public health workers with extensive knowledge of the local setting. Participant-observation was mainly aimed at meeting service-users and therefore community centre activities such as lunches and discussion nights, locally organised workshops or events aimed at service-users and locations for volunteer work were visited on 29 occasions. On six occasions, a social worker was observed on the job. Observations had a duration of 45 min to 5.5 h with an average of about 2.5 h. The informal conversations were intended both to afford a better understanding of experiences with (in)dignity and to clarify what had just been observed. The researcher took field notes, which included not only the researcher’s observations but also her reflective comments.

The researcher also conducted formal interviews with service-users (n = 9) and social workers (n = 13). Respondents were approached at the research sites where participant-observations were conducted or contacted through snow-balling (Atkinson & Flint, Citation2001). The categories of service-user and social professional somewhat overlap. Two of the service-users interviewed were studying to become an experiential expert and two of the social workers had experience as a service-user and now applied this experience explicitly in their work. Their experiences as service-users were the main topic of the interview and their double perspective offered in-depth reflections. The formal interviews each lasted from 45 min to 2 h and were transcribed verbatim. The interview guide was based on the researcher’s field notes. It was designed to allow key informants to add meaning to the researcher’s observations; to elicit their perceptions on dignity and to offer them opportunity to elaborate on the meanings they gave to their own actions in certain situations as well as the meanings they thought that others gave.

Finally, three focus groups were organised: one with service-users (n = 7), one with social workers (n = 23) and one mixed group consisting of service-users (n = 4), social workers (n = 3) and policymakers (n = 2). During these focus groups, a preliminary version of the typology of (in)dignity formed the basis of the discussion and informants were asked to react and share their thoughts on the model concerning both its substance and form.

Ethical issues

The current study was evaluated by Medical Ethical Review Committee Utrecht, who confirmed that the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act (WMO) did not apply, as participants were not patients but mentally competent citizens, and participants were not subjected to treatment or required to follow a certain behavioural strategy as referred to in the WMO (art.1b). Subsequently, official approval of this study by the Medical Ethical Review Committee was not required (protocol: 13-176/C).

The aims and procedure of the research were discussed with informants on site, informed consent was acquired verbally. No written consent forms were required according to Dutch regulation at the start of the project in 2016 (The Netherlands Code of Conduct for Academic Practice, Citation2014). In the case of formal interviews, the informants were given the opportunity of a ‘member check’, i.e. they received their interview transcript via email and could comment or make changes if desired. All data were anonymised in order to ensure confidentiality of the informants. In this article, pseudonyms are used to refer to informants.

Data analysis

Data analysis took place during the same time periods as data collection, employing broad sensitising concepts (Blumer, Citation1954). These sensitising concepts were used primarily to lay the foundation for the ongoing analysis of research data, rather than specifically seeking to test, improve or refine them (Bowen, Citation2006). The data were first read in order to guide further data collection; then re-read for the purposes of searching for and identifying patterns and overarching themes together with all authors. The coding processes consisted of open and focused coding and were performed by the first author using Atlas.ti (Charmaz & Belgrave, Citation2012). With the aim of our study in mind, a pattern of themes emerged, which were again discussed together with all authors. Feedback was also given through discussion (‘peer debriefing’) with the research partner. The different methods that were employed have been primarily used to triangulate the data. In the presentation of our findings, we aimed for ‘thick description’ (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985) by describing the phenomenon observed in sufficient detail.

Results

In line with the findings of other empirical researchers on dignity in health- and social care, we initially found that our informants found it easier to talk about situations of indignity than moments where dignity occurred or was upheld (Bramesfeld et al., Citation2007; Caspari et al., Citation2013; Kinnear et al., Citation2015). For example, during one of the community centre lunches, the dignity research became an explicit topic of conversation. Tom, an elderly man, exclaimed that he at least knows what dignity is not: the way people are treated in nursing homes. In reaction to this, Ida, a woman in her early 60s, said to the researcher: ‘I’ve got a dignity story for you later’, leading to two vivid accounts of ways in which dignity was severely violated in the context of care and support. When informants did try to describe dignity in positive terms, they often seemed to have to resort to more abstract language, which basically amounted to being seen or treated as a human being.

Therefore, we first adopted a negative approach to dignity; understanding dignity by studying instances of its violation (Stoecker, Citation2011). According to Margalit (Citation1996), dignity is not only better understood in terms of its violation, but avoiding dignity violation can also be achieved more directly than dignity itself. However, it became increasingly apparent that service-users and social workers also put much effort in protecting or promoting dignity, which ultimately resulted in both a positive and negative account of human dignity. Below we first describe the four main ways in which service-users experience their dignity to be violated, as depicted in the outer circle of . Then we describe four forms of dignity promotion, depicted in the inner circle of the model. These forms together make up the dignity circle, as presented in .

Four forms of dignity violation

Object

Service-users find that they are sometimes seen or treated as a file, number or case rather than a unique person. People with multiple-problems especially run this risk as a result of their predicament, encountering the inherent multiple and various rules, regulations and organisations that are often involved in their case. Service-users (and social workers) struggle to find their way in this system. Often, it is a prerequisite for service-users to be categorised, before they can begin to get any help. When this categorisation starts to dominate, it becomes problematic. This is what Joanne experienced when she became homeless and was looking for help.

They tried to label you: we need to understand you, there must be something wrong. Tell us: are you addicted? Are you psychotic? […] Instead of sitting next to you and being like: ‘what do you need?’ ‘will you come talk to us sometime?’ […] First they made sure that there would be problems on the table. A diagnosis, then they would help you. […] You are a prisoner of that situation really.

Service-users can also feel treated as an object that must fit standardised procedures. This is illustrated by Sam when he mimics an encounter he had at the desk of a help organisation where the person who helped him never looked him in the face:

‘I see that you are still drinking, is that right?’. I’m sitting here. ‘Yes, that is true’. I’m sitting here [waves and point at himself]! Also, when you do have a conversation, everything is immediately checked on the screen.

Empty space

Service-users describe situations where they are not seen or heard by anyone. As resources are limited, social workers and their organisations are often faced with the task of setting priorities. However, this can leave some service-users feeling that their situation needs to get much worse before they can get help. The story of Nel is striking:

I was not heard. I wanted help. I kept saying: please, keep me here longer, help me please! Then they would say: ‘no, you only drink when you are having problems’. But I always have problems! I can’t do it alone! […] I begged my children: have them admit me, tell them you can’t live with me like this.

I didn’t like not working at all, my body seriously hurt from hanging about on the couch. […] I didn’t feel like seeing people. You feel useless, you don’t participate in anything. Everybody talks about work, I see children going to school. Society lives on and you are sitting at home, dead.

Child

Service-users frequently talk about instances where their experiences, knowledge or abilities are not taken seriously. This often leads to the feeling of being viewed as an ignorant child. For example, in the case of John, where a social worker assumed he could not read: ‘They started reading to me in a childish way. People- I can read! That feels very shitty’. Related to this is the experience of service-users that they are not being listened to. Sometimes service-users feel that professionals want to emphasise that they know better. Amy explains:

Indeed, as if you are less. Because they act [as if] higher than you: ‘I am stable, you are not, so I know how it’s done’. That is not always nice. It easily demotivates. I had a psychologist who didn’t believe I had sleeping problems. He printed a booklet for me with tips to help me sleep; it didn’t work. ‘Then it’s all in your head’. […] Instead of asking me questions like: ‘do you worry a lot?’.

I think, sometimes I need a little push. No kick in the butt, but a little push to go over that threshold. But other than that, I’m not stupid, I can take care of things myself. But she would for example, in my presence, call an organization where I wanted to do volunteer work, and then talk about me […] I felt myself getting this small.

Monster

Service-users can experience moments where they are seen as crazy, dirty or criminal. People with multiple-problems are easily at risk of stigmatisation because they often do not live up to societal norms. This can lead to service-users being met with hostility by other citizens. Tamara gives an example:

Back in the day I got called names when cycling through the neighbourhood. I looked really bad then, I wasn’t doing well. It felt like that, like a dagger stabbing me here [pointing towards solar plexus].

At times service-users even feel that others are afraid of them. This is what Jean experienced when her newly acquainted general practitioner came to her house, a short time before she was admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

She didn’t talk to me. She was inside the house for just a moment and then she left, almost afraid. Like I would hurt her or something. […] I didn’t feel like ‘oh, here is somebody to help me’, I felt on display. Like I was indeed crazy or something. Well, I wasn’t that crazy then.

Four forms of dignity promotion

Now that the outer circle of the model has been established, the ways in which service-users and social workers try to work from dignity violation towards dignity promotion completes the typology. However, these forms of dignity promotion are not without tensions as opportunities for dignity promotion can also come with new risks of its violation. This often requires a balancing act on the part of the social worker.

Unique person

When service-users experience that they are being recognised for who they are and the situation they are in, this contributes to dignity. For Joanne, who had the experience of being treated as an object, her situation changed when she met social worker Liza: ‘She was really acting towards me as Joanne, that was the first time. […] I don’t think she even knows that I am homeless, she is not concerned with that’. Joanne felt seen as her own person, not as ‘a homeless person’.

Paradoxically, while we have described how categorisation can result in service-users feeling treated as an object, it can also be a source of validation in terms of being recognised as a unique person. When a category fits or is helpful, service-users feel recognised in their problems. For example, Jean says the following about her bipolar disorder diagnosis:

It makes it easier to talk […] to everyone. You at least have a name [for it]. From that name, you can explain what you are like a little. That I am indeed … I know these two sides of myself.

Participant

Participating in society and fulfilling a meaningful role is an important source of dignity for service-users. Taking up activities in the community or working as a volunteer turned out to be a solution for many. Jason, who used to feel like he was treated as an empty space, feels relevant again through his volunteer work: ‘They say, “that is somebody who shows up and does his job well”’. Being expected by someone, somewhere and being appreciated leads to feelings of being seen.

To promote dignity, social workers sometimes need to reach service-users even when they are not explicitly asking for help. These interventions carry a risk of belittlement of the service-user. After all, the social worker has to tell the service-user that they have a problem and should act differently. Social workers struggle with this tension between on the one hand trying to remedy feelings of empty space but potentially ending up treating the person as a child. Social worker Tonnie reflects on this during a focus group:

People who live in a polluted house […]. No relationships, being invisible, that is literally and figuratively speaking ignored. […] That cocoon is really important to them, so can I call that empty space? You actually take their dignity away then.

Adult

Opposing previous experiences of feeling treated like a child, service-user Eva says about her current relationship with her social worker: ‘The most important thing is: I am an equal adult’. This means that within situations where people are dependent on support they are provided with as much control over their lives as possible. In moments of crisis, being able to let go of some responsibilities can, however, be very welcome. For example, some service-users appreciated that their finances were taken over by a professional when they could not manage themselves. However, it remains important for service-users to set their own priorities, as Eva notes: ‘I am the boss […] I give suggestions, and if they don’t agree, they’ll give counterarguments’.

Evidently, an increase in equality in the relationship between social worker and service-user also promotes dignity, for instance, through interactions whereby the social worker shows involvement and is honest. As Eva says: ‘My social worker and I don’t always see eye to eye. She has opposed me fiercely at times. But that is what I appreciate about her’. Using humour and showing vulnerability on the part of the social worker can have the same effect.

Friend

In some cases, distrust in the care relationship is countered by treating a service-user like a friend, in order to avoid the experience of feeling like a monster and to create room for dignity. This means displaying an open attitude to negate stigmatisation while keeping professional distance. Social worker Victor suggested the term ‘professional friendship’ in this regard, and gives the example of not ignoring personal questions he gets from service-users but making sure to answer them in a way that is appropriate.

Professional friendship refers to the long-term supportive relationships between social worker and service-user that are sometimes deemed required to build trust when distrust is strong. For example, when a client is struggling a lot, social workers choose to offer practical help first, so the situation can calm down. Later, when some trust has been established, it becomes possible for social workers to discuss more personal matters concerning the client and ask them to reflect on their actions. As relationships between social workers and clients are inevitably unequal power relations to some extent, a professional friendship is not to be confused with a regular friendship, which is usually more equal and reciprocal. For the social worker, professional friendship is a balancing act between friendship-like proximity and professional distance, as social worker Zeynep illustrates:

I had a 23-year old girl […] living with her parents and [who] has an anxiety disorder. Very heavy lady, in terms of weight. I have a professional relationship with her, but […] she calls me ‘sister’. […] But these are important things really. […] What does this mean for the relationship you have built? She wants to see me every week, and I have to say: ‘no, first you are going to work on what we have talked about’.

Discussion

In this concluding section, we will first briefly reiterate our dignity circle, delineate the limitations of our research design and then show how our findings relate to previous studies on dignity. Subsequently, we will reflect on the nature of our model, evaluating its use and limitations.

The dignity circle is based on the experiences of, and developed together with, service-users and social workers themselves. The model includes an outer and inner circle. The outer circle consists of four main ways in which service-users experience their dignity to be violated, respectively, when they feel seen or treated as: an object, an empty space, a child or a monster. Reversely, the inner circle entails four ways in which service-users and social workers promote dignity, respectively, being seen or treated as: a unique person, a participant, an adult or a (professional) friend.

With the dignity circle, we do not intend to present a method. The purpose of establishing the dignity circle is more modest: it is meant to be a ‘heuristic tool’ (cf. Vosman & Niemeijer, Citation2017) to stimulate and support social workers and their clients to discuss experiences of dignity promotion and dignity violation, by presenting words and images that are closer to everyday experiences than the abstract concept of dignity itself.

Human dignity is often understood as two-sided (see, for instance, Edlund et al., Citation2013; Killmister, Citation2010; Pols, Citation2013), either referring to the intrinsic value people possess by virtue of being human (Rosen, Citation2012) or to a feature of relations (Leget, Citation2012). The latter is known as social dignity that emerges in practices and is, therefore, a quality that can be lost or gained in interactions (Jacobson, Citation2007; Kirchhoffer, Citation2013; Leget, Citation2012). The dignity circle is an elaboration of social dignity regarding care and support for people with multiple-problems.

The focus of this research was on the extent of variation in which the observed situations occurred, and how exemplary these situations were, rather than statistical frequency (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). Thus, we cannot assess how often certain experiences of dignity or indignity take place. However, we can assess that our circle is not just a collection of incidents and personal experiences of a limited number of respondents by relating our findings to previous studies on dignity.

Several studies on the perspectives of service-users related to dignity have described similar experiences to what we have termed object, empty space, child and monster (e.g. Bossy et al., Citation2017; Collins et al., Citation2008; Hughes et al., Citation2008; Lindgren et al., Citation2015; Whitaker et al., Citation2011). For example, Holm et al. (Citation2014) found that elderly persons who are diagnosed with a depressive or mood disorder experience stigmatisation caused by being viewed or treated exclusively in terms of their diagnosis. When they try to address their physical health problems, they often meet scepticism, as it is assumed that any concomitant physical health issues are imaginary and thus related to their depression. These findings correspond most strongly with dignity violations by being treated as an object and a monster. The elderly in this study feel seen as a case of depression; an object instead of a unique person. They experience to be deemed a bit ‘crazy’ (monster) in relation to this diagnosis as they are told to be imagining physical health problems.

Social work has been described as a human rights profession (IFSW, Citation1996, Citation2014). As stated in the introduction, this may inspire social workers to campaign in favour of structural changes in society that would benefit oppressed groups. It obliges them to raise awareness among policymakers and politicians about infringements of human rights that they encounter in the course of their work; social workers need to draw attention to, for example, housing problems, poverty, or hidden oppression of vulnerable groups such as women and children. Social workers are increasingly expected to engage with structural sources of oppression and play an advocacy role (Ornellas et al., Citation2018). To this end, social workers have to show that many of the private troubles they encounter are actually public issues that are in need of macro-level solutions (Dominelli, Citation2007; Vandekinderen et al., Citation2018).

Our dignity circle shows an additional aspect of social work being a human rights profession: social workers could use the circle to avoid and discuss dignity violations and to try to counter them by displaying the opposite, inner circle behaviour. The dignity circle can play a role in promoting dignity on the level of interactions between social workers and service-users. With the dignity circle social workers are enabled to reflect on work practices of themselves and their organisations; amongst themselves and together with service-users. It is important for social workers to be able to establish when dignity violation could be occurring and of which type(s). Social workers might infer this from the behaviour of service-users. When service-users are treated as an object, they often feel powerless and display frustration and anxiety. In situations where service-users feel treated as an empty space, they are inclined to close themselves off. This also happens when service-users feel treated as a child; because they feel that they are not on equal footing with the social worker, they might be reluctant to share information or show anger. Finally, when treated like a monster, service-users might display low self-esteem, mistrust towards others and even destructive behaviour. When the social worker suspects that dignity violation is impacting the service-user, whatever the source, they can try to start working towards dignity again. The four concepts of the inner part of the circle are meant to support this process. The concept of friend in the inner part of the circle refers to a specific type of friendship, namely professional friendship.

There are no miracle methods for social workers, especially when they are dealing with service-users who are plagued by various afflictions and conditions simultaneously. In these cases, social workers perform balancing acts. Avoiding one type of dignity violation (i.e. overlooking the client’s needs, ignoring their cry for help) may result in doing too much and interfering too soon, thereby treating the client as a child. Balancing autonomy, care and dignity is a perpetual challenge for social workers (Holm & Severinsson, Citation2014; Skorpen et al., Citation2016). Bringing into focus these possible trade-offs between dignity promotion and dignity violation is a strength of the dignity circle model as it enables reflection on the dilemmas and complexities that arise when attempting to provide dignified care and support.

Two important caveats regarding the dignity circle model need to be addressed. The first is that the well-being of the social worker also needs be taken into account at all times. For example, when approaching a service-user as a (professional) friend, this does not mean that social workers should have an open attitude towards all types of behaviour. The dignity of the social worker should not be compromised in trying to promote the dignity of the service-user. Second, the fact that the dignity circle intends to promote human rights-inspired behaviour at the micro-level does not imply that dignity violations are necessarily caused by or can be solved at this level. However, social workers can use the model to point out which resources they need, to be able to uphold human rights of service-users while treating them in a dignified way. The circle may induce advocacy behaviour, just like the human rights violations described above.

Finally, it is important to take into account that social work is not only a profession but also an academic discipline (IFSW, Citation2014). Social work researchers might use the dignity circle as a starting point to investigate under which circumstances dignified social work becomes possible for both service-users and social workers.

Despite its limitations, we hope that the dignity circle provides social workers with a practical and reflexive tool that helps them shape their human rights profession in their daily work.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost we want to thank all the service-users and social workers who were part of this study. We would also like to give special thanks to our research partner Annette Schlingmann for our fruitful collaboration on this project. Finally, we want to express our gratitude for the support, enthusiasm and insights of several members of the Department of Public Health of the Municipality of Utrecht and the late Hanneke Schreurs in particular.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Jante Schmidt is a PhD candidate at the University of Humanistic studies. Her research project concerns experiences of dignity of people with multiple problems in the context of care and support. With her background in sociology, she is interested in how micro-level interactions and macro-level structures together inform these experiences. She has dedicated time to translating the findings of this research project to a wider audience through the means of a research report (in Dutch), an animated video and presentations for people from the social work field. See also: https://www.linkedin.com/in/janteschmidt/.

Alistair Niemeijer is an assistant professor in Care Ethics at the University of Humanistic Studies. His line of research focuses on precarious practices of care and well-being of and for the (chronically) vulnerable. In the research projects he is involved, he tries to emphasise the dialectical relation between empirical research and theoretical reflection in order to answer the question how to best understand lived experiences of people living with illness or disability, whose voices have formerly been missing. See also: https://www.linkedin.com/in/alistair-niemeijer-9142772a/.

Carlo Leget is the full professor in Care Ethics at the University of Humanistic Studies. At the same university, he holds an endowed chair in Ethical and spiritual questions in palliative care, established by the Association Hospice Care Netherlands. His research is situated at the intersection between care ethics and spirituality or meaning, with main expertise in palliative care and end-of-life issues. See also: https://www.linkedin.com/in/carlo-leget-12b62a12/.

Margo Trappenburg holds an endowed chair at the University of Humanistic Studies. She is an Associate Professor at the Utrecht School of Governance, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. Her research interests include professionalism (mostly of healthcare professionals and social workers) and changing welfare states. She recently published in this journal on the deprofessionalisation of social work, due to changes in the welfare state (together with Gercoline van Beek, in 2017). Her analysis of the changing welfare state, entitled ‘Active Solidarity and Its Discontents’ was published in Health Care Analysis. See also: https://www.linkedin.com/in/margotrappenburg/

Evelien Tonkens is the Professor of Citizenship and Humanization of the Public Sector at the University of Humanistic Studies. Her research concerns sociological analysis of changing ideals and practices of citizenship and professionalism. She published in Social Politics, Citizenship Studies, Sociology, Health Promotion International, Social Policy and Society, Culture, Renewal, Medicine and Psychiatry, Social History of Medicine and Community Development Studies. With J. Newman, she edited the book Participation, responsibility and choice: Summoning the active citizen (Amsterdam University Press 2011) and with M. Hurenkamp and J.W. Duyvendak, she wrote Crafting citizenship. Understanding tensions in modern societies (Palgrave 2012). See also: https://www.linkedin.com/in/evelientonkens/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Article 22 of UDHR (UN, 1948).

2 This title was first awarded to the city in 2012 in a speech by Navanethem Pillay, then United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. See also: https://humanrightscities.net/humanrightscity/utrecht/ and http://humanrightsutrecht.nl/.

3 This literature review, entitled ‘Social dignity for marginalized people in public healthcare: An interpretive review and building blocks for a non-ideal theory’ by J. Schmidt, M. Trappenburg & E. Tonkens is currently under review.

References

- Abma, T. A., Nierse, C. J., & Widdershoven, G. A. M. (2009). Patients as partners in responsive research: Methodological notions for collaborations in mixed research teams. Qualitative Health Research, 19(3), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309331869

- Atkinson, R., & Flint, J. (2001). Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Social Research Update, 33, 1–4.

- Beresford, P., & Carr, S. (2012). Social care, service users and user involvement. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Blumer, H. (1954). What is wrong with social theory? American Sociological Review, 18(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/2088165

- Bossy, D., Knutsen, I. R., Rogers, A., & Foss, C. (2017). Group affiliation in self-management: Support or threat to identity? Health Expectations, 20(1), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12448

- Bowen, G. A. (2006). Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500304

- Bramesfeld, A., Klippel, U., Seidel, G., Schwartz, F. W., & Dierks, M. (2007). How do patients expect the mental health service system to act Testing the WHO responsiveness concept for its appropriateness in mental health care. Social Science and Medicine, 65(5), 880–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.056

- Caspari, S., Aasgaard, T., Lohne, V., Slettebø, A., & Naden, D. (2013). Perspectives of health personnel on how top reserve and promote the patients’ dignity in a rehabiliation context. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(15–16), 2318–2326. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12181

- Charmaz, K. (2009). Shifting the grounds: Constructivist grounded theory methods for the twenty-first century. In J. Morse, P. Stern, J. Corbin, B. Bowers, K. Charmaz, & A. Clarke (Eds), Developing grounded theory: The second generation (pp. 127–154). Left Coast Press.

- Charmaz, K., & Belgrave, L. L. (2012). Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. In J. F. Gubrium, J. A. Holstein, A. B. Marvasti, & K. M. Marvasti (Eds), The SAGE Handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft (pp. 347–365). SAGE Publications Inc.

- Collins, P. Y., Unger, H. v., & Armbrister, A. (2008). Church ladies, good girls, and locas: Stigma and the intersection of gender ethnicity, mental illness, and sexuality in relation to HIV risk. Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.013

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd Ed.). Sage Publications.

- Dean, H. (2015). Social rights and human welfare. Routledge.

- Dominelli, L. (2007). Human rights in social work practice: An invisible part of the social work curriculum? In E. Reichert (Ed.), Challenges in human rights. A social work perspective (pp. 16–43). Colombia University Press.

- Edlund, M., Lindwall, L., Von Post, I., & Lindström, U. A. (2013). Concept determination of human dignity. Nursing Ethics, 20(8), 851. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013487193

- Healy, L. M. (2008). Exploring the history of social work as a human rights profession. International Social Work, 51(6), 735–748. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872808095247

- Hewlett, S., De Wit, M., Richards, P., Quest, E., Hughes, R., Heiberg, T., & Kirwan, J. (2006). Patients and professionals as research partners: Challenges, practicalities, and benefits. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 55(4), 676–680. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22091

- Holm, A. L., Lyberg, A., & Severinsson, E. (2014). Living with stigma: Depressed elderly persons’ experiences of physical health problems. Nursing Research and Practice, 2014, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/527920

- Holm, A. L., & Severinsson, E. (2014). Reflections on the ethical dilemmas involved in promoting self-management. Nursing Ethics, 21(4), 402–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013500806

- Hughes, A., Davies, B., & Gudmundsdottir, M. (2008). “Can you give me respect?” Experiences of the urban poor on a dedicated aids nursing home unit. Journal of the Association of Nurses in Aids Care, 19(5), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.008

- Ife, J. (2007). Cultural relativism and community activism. In E. Reichert (Ed.), Challenges in human rights. A social work perspective (pp. 76–96). Colombia University Press.

- International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW). (1996). International policy on human rights. https://www.ifsw.org/human-rights-policy/

- International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW). (2014). Global definition of social work. http://ifsw.org/policies/definition-of-social-work/.

- Jacobson, N. (2007). Dignity and health: A review. Social Science & Medicine, 64(2), 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.039

- Killmister, S. (2010). Dignity: Not such a useless concept. Journal of Medical Ethics, 36(3), 160–164. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2009.031393

- Kinnear, D., Victor, C., & Williams, V. (2015). What facilitates the delivery of dignified care to older people? A survey of health care professionals. BMC Research Notes, 8(1), 826 (1–10). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1801-9

- Kirchhoffer, K. G. (2013). Human dignity in contemporary ethics. Teneo Press.

- Leget, C. (2012). Analyzing dignity: A perspective from the ethics of care. Medicine, Health Care & Philosophy, 16(4), 945–952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-012-9427-3

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Lindgren, B. M., Eklund, M., Melin, Y., & Graneheim, U. H. (2015). From resistance to experience - experiences of medication-assisted treatment as described by people with opioid dependence. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(12), 963–970. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1074769

- Mapp, S., McPherson, J., Androff, D., & Gatenio Gabel, S. (2019). Social work is a human rights profession. Social Work, 64(3), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swz023

- Margalit, A. (1996). The decent society. Harvard University Press.

- Movisie. (2018). Peiling: ervaringsdeskundigen maken opmars in het sociaal domein. https://www.movisie.nl/artikel/peiling-ervaringsdeskundigen-maken-opmars-sociaal-domein.

- The Netherlands Code of Conduct for Academic Practice. (2014). https://www.vsnu.nl/wetenschappelijke_integriteit.html.

- Ornellas, A., Spolander, G., & Engelbrecht, L. K. (2018). The global social work definition: Ontology, implications and challenges. Journal of Social Work, 18(2), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316654606

- Pols, J. (2013). Washing the patient: Dignity and aesthetic values in nursing care. Nursing Philosophy, 14(3), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/nup.12014

- Reichert, E. (2007). Human rights in the twenty-first century. Creating a new paradigm for social work. In E. Reichert (Ed.), Challenges in human rights. A social work perspective (pp. 1–15). Colombia University Press.

- Rosen, M. (2012). Dignity: Its history and meaning. Harvard University Press.

- Skorpen, F., Thorsen, A. A., Forsberg, C., & Rehnsfeldt, A. (2016). Views concerning patient dignity among relatives to patients experiencing psychosis. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30(1), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12229

- Social Care Institute for Excellence. (2013). Dignity in care practice guide. SCIE.

- Stoecker, R. (2011). Three crucial turns on the road to an adequate understanding of human dignity. In P. Kaufmann, H. Kuch, C. Neuhäuser, & E. Webster (Eds.), Humiliation, degradation, dehumanization. Human dignity violated (pp. 7–20). Springer.

- van der Kooij, A., & Keuzenkamp, S. (2018). Ervaringsdeskundigen in het sociaal domein: wie zijn dat en wat doen ze? [Experiential experts in the social domain: Who are they and what do they do?]. Movisie.

- Vandekinderen, C., Roose, R., Raeymaeckers, P., & Hermans, K. (2018). Sociaalwerkconferentie 2018, Sterk Sociaal Werk. Eindrapport [Social work conference 2018, Strong Social Work. Final report]. Leuven: Steunpunt Welzijn, Volksgezondheid en Gezin.

- Vosman, F., & Niemeijer, A. (2017). Rethinking critical reflection on care: Late modern uncertainty and the implications for care ethics. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 20(4), 465–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-017-9766-1

- Whitaker, T., Ryan, P., & Cox, G. (2011). Stigmatization among drug-using sex workers accessing support services in Dublin. Qualitative Health Research, 21(8), 1086–1100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311404031