ABSTRACT

Quality of public services including social services is an issue frequently discussed by policy makers, service providers, and by those who represent service users. The aim of this study was to explore how stakeholders perceive quality of social services, with a particular focus on (1) what did participants rate as important; (2) what is the relative importance of each domain and how does that differ across stakeholder groups and (3) does importance vary by participant characteristics. A specially designed questionnaire was completed by 217 service providers, by 249 public administration representatives and 205 service users of residential care and in-home support. The subjective quality of life of service users was rated as the most important indicator of service quality by all three stakeholder groups. Particularly important were items that related to the nature of the relationships and interactions between staff and service users. There were some differences between stakeholder groups and also by respondent characteristics – public administration respondents, older service users and providers of residential care were more likely to rate health care as more important than other respondents. Implications for how quality is measured are discussed.

ABSTRAKT

Kvalita veřejných služeb, včetně sociálních služeb je tématem často diskutovaným mezi tvůrci sociálních politik, poskytovateli sociálních služeb a těmi, kteří zastupují uživatele služeb. Cílem této studie bylo zjistit, jak respondenti – zástupci veřejné správy, poskytovatelé sociálních služeb a uživatelé vnímají kvalitu sociálních služeb, se zvláštním zaměřením na to: (1) co hodnotí respondenti jako důležité; (2) jaká je relativní vnímaná důležitost každé domény a jak se tato vnímaná důležitost liší mezi kategoriemi respondentů a (3) jak se tato důležitost liší v závislosti na charakteristikách respondentů. Speciálně navržený dotazník vyplnilo 217 poskytovatelů služeb, 249 zástupců veřejné správy a 205 uživatelů sociálních služeb. Subjektivní kvalita života uživatelů služeb byla všemi třemi kategoriemi respondentů hodnocena jako nejdůležitější ukazatel kvality služeb. Obzvláště důležité pak byly položky, které se týkaly povahy vztahů a interakcí mezi zaměstnanci a uživateli služeb. Existovaly určité rozdíly mezi kategoriemi respondentů a také podle jejich charakteristik. Respondenti veřejné správy, starší uživatelé služeb a poskytovatelé rezidenční péče hodnotili zdravotní péči mnohem důležitěji než ostatní respondenti. V článku jsou diskutovány také některé přístupy k hodnocení kvality.

Introduction

Social care services endeavour to maximise the quality life of those who are more or less dependent on support provided by another person. The aim of social services is not to cure the impairment but to compensate the person for the impact of their impairments. How to assess ‘the impact’, processes and outcomes of social care services has been discussed by researchers and policy makers for more than twenty years, often linked to reforms in social policies, strategic planning programmes or their implementation.

Although the aims and nature of Government social care reforms in different countries have differed, there have been some common patterns, such as a trend towards a purchaser/provider split and diversification of the provider market to give service users more choice and control over their support (Šiška & Beadle Brown, Citation2020).

Secondly, the economic crisis followed by retrenchments in public funding has raised questions for policy makers on how to assess outcomes of interventions aiming to generate what Qureshi and Nicholas (Citation2001) call ‘change outcomes’ and often more challenging ‘maintenance outcomes’. Difficulty in measuring social care outcomes is also inevitably related to different perspectives and judgments of stakeholders on quality and how it is defined as well as to external factors such as cultural, social and political forces and how services have historically been organised. In countries from the so-called former Eastern bloc such external structures changed as part of fundamental political and economic transformation which happened in the nineties. However, the agenda of community-based services as opposed to institutional care emerged only relatively recently in Czechia. Similarly, the issue of assessing quality of social care services has been challenged by stakeholders a decade after it came into force. The newly adopted Act on Social Services 2006 (2006 Act) came into force with high and relatively unified expectations shared by stakeholders such as service providers, policy makers, public administration same as those represented service users such as disabled peoples’ organisations. The new legal provision was seen as a driver for change towards empowering service users and improving quality of social services in general (MoLSA, Citation2005). In the rest of this introduction, we will briefly outline developments in social services in Czechia considering political transformation in the nineties and during the first decade of the new millennium. We will then present what is already known about research on defining and measuring service quality before going on to present the findings from the current study.

The 2006 Act was drawn up in an attempt to compensate for the limited legislative basis for social services, which had been set up in the 1980s and did not reflect the human rights agenda such as the right to self-determination and the right to community participation. The 2006 Act states that the general aim of services is to maintain the highest possible quality and dignity in the lives of service users. Social services which fall into the social care category comprise counselling, personal assistance, sheltered living support, and larger institutional settings for the elderly, and for persons with disabilities. The largest group of beneficiaries are older people, then people with disabilities, followed by families with children and those living on the fringes of society for various reasons. The providers include municipalities and regions, non-governmental organisations, churches and private organisations. The MoLSA holds responsibility for quality assurance.

The 2006 Act enables service users to be directly involved in purchasing their service from a variety of providers including independent for profit and not-for-profit providers. In addition, service users should be involved in the evaluation of the service delivery and protected from violation of their rights. These assumptions had been seen as drivers of change for cultivating quality of care and for deinstitutionalisation. However, there remains a gap between the rhetoric of the 2006 Act and the reality of the lives of people with disabilities. Real choice about how and where people receive their service remains limited. People with disabilities and their families are often forced to opt for large residential provision, not because they see particular merits in this option but because alternatives are not available (Šiška & Beadle-Brown, Citation2011). Despite significant improvement, for example, in living conditions of residential services, the real impact of the quality of care inspection system as the key catalyst for change has been questioned (CitationŠiška & Čáslava; in press; Kocman & Paleček, Citation2013).

One issue is in the conceptualisation of quality of care. This concept is seen as complex and made up of different elements. Donabedian (Citation1966, Citation1980) suggested that the key indicator of service quality should be the outcomes experienced by those supported. Although the conceptualisation of outcomes and quality of life is a key area of research especially in the field of disability (e.g. Schalock et al., Citation2002), in policy and practice, conceptualisation and agreement on what constitutes good outcomes and quality of life is still a subject of debate or lack of clarity. The concept of Quality of life (QoL) also appears in other areas such as in economics, medicine and the social sciences and is measured in a variety of ways, including both subjective (e.f. happiness, satisfaction, feeling well and safe) and objective measures (such as employment status, accessibility, income, meaningful occupation etc). However, in order to deliver and understand outcomes such as quality of life Donabedian suggested that it is essential to also think about processes (i.e. the practices used by those providing support) and the structures (e.g. policies and procedures, physical environment, number of staff, resources, skills and attitudes of workers, training etc.) present in the system. Although there is very little research on how care quality standards and quality assurance processes in social services have been developed, most of those for which there is information available have worked on the basis of examining structures, processes and outcomes, although with varying emphasis on each element (Malley & Fernández, Citation2010).

Such an approach was also applied to the care quality standards in Czechia, introduced in the 2006 Act, which drew on the underlying principle of quality of life as a human right. However, within three years, criticisms were already being raised about the inspection process and in particular that they were not serving as a protection for service users, especially the most vulnerable. Service providers and the Ombudsman (Citation2019) have argued that assessing the quality of social care demonstrates conceptual and analytical challenges and the system is regarded as falling short with regards to improving the quality of social services. Rather, the inspection systems have been found to strengthen poor practices (Kocman & Paleček, Citation2013). After more than a decade, service providers, in particular, remain dissatisfied with the quality assurance system accompanied by a heavy administrative burden and a lack of coherence in the way regulators interpret the standards.

This has raised a core question in Czechia – who is eligible to frame quality of care and to decide on the respective domains to be assessed. Some inspiring ideas can be found in health care, for example, Brown (Citation2007) highlights the general need to first reach a consensus across the health sector on what quality means to the key stakeholders. The key stakeholders include service providers, the regulators who define service quality, and patients who use the services. According to McGlynn (Citation1997), patients, care providers and investors define quality differently and may differ in their views of how it should be assessed: ‘To some degree, quality is in the eye of the beholder’ (p. 1). Stichler and Weiss (Citation2001) noted the different meanings that quality has for patients and professionals. Professionals tend to define quality within professional standards of care, patients describe the interpersonal aspects of care and the ability of staff to respond to their needs.

Donabedian (Citation1980, Citation1988) argued that the concept of quality must contain criteria that are acceptable and complete. Pittam et al. (Citation2015) identified what was considered by service providers, government officials, service users and their families as important in assessing the quality of service. In this study, stakeholders rated safety and person-centred care as the most important domains of quality. In addition, the authors underlined the importance of knowing the opinions of all stakeholders for a deeper understanding of quality, although this creates some difficulties related to whose views carry more weight in the case of disagreement.

In conclusion, the domains which are used to conceptualise the quality of care should be seen as important and accepted by all stakeholders. In addition, we argue that the development of new systems of care quality assessment should commence with a systematic identification of similarities and differences in the perception of quality of care by the stakeholders.

The aim of this study was to understand how core stakeholders in Czechia perceive quality and which domains the stakeholders consider as most important for assessing the quality of social services.

The three research questions which guided the measure development and the analysis were:

What items did each stakeholder group perceive as most important?

What was the relative importance of the domains by stakeholder group?

Did perceptions of importance vary by personal characteristics such as age and gender or by service type?

Methods

This study was a cross-sectional questionnaire study exploring the views of three categories of stakeholders – service users, service providers and public administrators working in the area of social care. In this study, service users were (1) those with disabilities and the elderly using residential care settings (housing, healthcare and support combined), and (2) those service users who lived in their own homes and receive in-home support.

Participants

Service providers. From the total number of registered services in April 2019 (N = 2610) providing long-term care, 1000 providers were randomly selected and contacted with a request to complete a survey.

Public administration. The social services departments of all 14 regional authorities in the country and all municipalities with responsibility for social affairs (N = 204) were contacted with the survey.

Service users. The aim was to recruit approximately 300 service users across all 14 regions of Czechia and from the main types of social services (i.e. residential social care settings for the elderly and for persons with disabilities) in approximately the same proportion as found in the total sample of registered services. For example, 20% of people using social care services are living in residential services for the elderly and so the aim was to have approximately 20% of our sample living in residential services for the elderly. Across the whole sample, the aim was to have approximately equal numbers of older adults and people with disabilities. No other criteria were applied.

Services users were recruited through service providers who were contacted initially through research team networks and then snowball sampling. Service providers then approached a sample of service users who they thought might be able to complete the questionnaire with support from trained assistants from the research team and asked them whether they would be willing to participate.

Measures

The questionnaire consisted of 7 domains related to service quality. Each domain contained several items, which were formulated as statements describing different aspects of quality. Respondents were asked to assess the significance of each item for the quality of a service on a five-point scale: with 1 = not at all important, 2 = of little importance, 3 = I’m not sure, 4 = important and 5 = very important.

There were four versions of the questionnaire: – one for service providers, one for public administration representatives and two for service users. The questionnaires for service providers and public administration respondents differed only on a small number of items. The questionnaires for service users included an easy to read version to support the inclusion of those with intellectual disabilities or older people with cognitive disabilities or communication difficulties. The latter consisted of just five domains – the Context and Management domains were not relevant to service users.

The different versions of the questionnaire were piloted with a sample of 10 respondents. Six were service providers or Public administration representatives and 4 were service users.

Validity and reliability

Content validity

Domains and items were identified drawing on the outputs of a thematic analysis of the content of indicators or quality criteria from relevant domestic and international models of quality assessment. It was assumed that the content of these models had been validated during preparation phase and therefore represented external criteria with an appropriate content validity.

The first source reviewed was The Czech national Quality Standards of Social Services. The quality standards cover 15 areas and serve as the legal framework for regulating social services in Czechia. Other sources were two models developed by the National Association of Social Service Providers – Quality Standards for Residential Facilities and the Quality Mark. The European model (SPC, Citation2010) has highlighted the impact of the wider context in which services are provided. The UK-based study for Quality Watch (Pittam et al., Citation2015) was also considered in the development of the questionnaire.

Seven core domains were identified for the questionnaire as a result of this review. These were the core domains which were present in the most analysed models. Four of these areas are also present in the national quality standards. However, three of these areas were absent from the national quality standards – health care, subjective quality of life of service users, and the broader context of the environment in which service is provided. These three areas were included in the questionnaire based on the recommendations of a number of critical reviews by relevant representatives of regional governments and services providers in Czechia.

Subsequently, individual items from the above quality assessment models and tools used in different countries were used to identify a list of items for each of the seven domains. This process was conducted by the project team and potential domains and items were discussed until consensus was reached. Statements for the questionnaire were then formulated for each item. presents the final domains and list of items.

Table 1. Domains and items with Cronbach Alpha.

Reliability

Internal consistency of the questionnaire was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, which is a measure of internal consistency of research instruments. Cronbach’s alpha was determined for the instrument as a whole and its domains on the basis of the polychoric correlations of the individual items. The higher the correlation between items on the scale, the higher the Cronbach’s alpha statistic. As can be seen from , internal consistency was good with overall scale statistics over 0.9 for all three stakeholder groups. Only one individual domain had a lower Cronbach alpha (0.42) and that was domain D5 Quality of the environment for service users.

Construct validity

The reported high consistency of the instrument and its domains made it possible to evaluate the construct validity. We carried out exploratory factor analysis based on polychoric correlations. The analysis was performed using the principal axis factoring method with the varimax rotation. The number of factors was not restricted for the initial analysis and the Kaiser rule recommending retention of factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 was implemented. We found that seven factors, explaining in total between 58 and 64% of the variance for the individual groups of stakeholders, fulfilled this condition. Thus, the rotation of these factors was carried out. We computed the factor loadings of the individual items and found the data strongly supported the 7-domain model based on the aforementioned content analysis with the highest factor loading corresponding in almost all cases to the factor predicted by the model. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis was used to verify the 7-factor structure. It was found that this solution fitted well to the data and was superior to the competing models for the all groups of stakeholders studied. The construct validity of the questionnaire was thus confirmed, and the evaluation of the results obtained by 7 domains was justified. The further analysis of the psychometric properties of the instrument and its development will be given in a separate paper.

The study procedure

Service providers and public administration representatives were contacted by MoLSA with the information about the project and an invitation to participate. The link to the relevant survey was contained in the invitation. The questionnaire was made available online through Google Forms for an eight-week period during 2019.

Due to the nature of the needs of the service users recruited through providers – most had mild intellectual disabilities or were older adults with some cognitive or communication difficulties – the service users’ questionnaire was administered face-to-face by six trained research assistants. Research assistants visited the service users where they lived and supported them to complete the questionnaire, providing, for example, help reading the questions or recording the responses as needed by each individual.

The research assistants were trained to facilitate the questionnaire completion prior to the start of the study – how to address service providers and service users, how to facilitate the questions, and how to record and process the answers. They were made aware of the ethical procedures related to the study.

Data analysis

The returned data were analysed using MS Excel with inbuilt accessory XLSTAT 2019. Both descriptive and inferential analysis was conducted. In each category of stakeholders, the significance of the deviations of individual items from the average was tested using a single-sample t-test. The significance of differences between quality domains was tested for each stakeholder group using Friedman related measures analysis of variance with Nemenyi post hoc tests. The statistical significance of differences between stakeholder groups was also tested using Kruskall–Wallis non-parametric ANOVA and Mann–Whitney U tests.

Ethical approval

Principles of good ethical practice spelled out in the National Ethical Framework for Research 2005 were adhered to during the research study. All participants were informed in an easy-to-understand way that data gathered would be used in reports and papers in anonymous form so that they would not be identified. They were also informed that their participation was voluntary – they did not have to participate. No identifying information was recorded on either the on-line or the hard copy questionnaires.

Results

Response rates and respondent characteristics

shows the composition of the final sample. As can be seen there were 249 responses from public administration representatives. Responses were received from all 14 regional authorities and from all 204 municipalities invited but, for some municipalities, more than one survey was returned. A quarter of the public administration surveys were completed by the heads of departments for social affairs, who were responsible for the implementation of social policy in their territory. The majority were women and mostly between 40 and 59 years of age.

Table 2. Response rates and respondent characteristics.

For service providers, the return rate was 22%, which is similar to that often achieved in online surveys. The 217 service providers completing the survey represented 9% of all residential and supported living/in home support services for older adults and for people with disabilities in Czechia. Most of the respondents were quality managers, directors and social workers. As for public administration, the majority were female and between 40 and 59 years of age.

also shows some of the basic characteristics of the service user respondents. Sixty percent were female, and the largest proportion was over 70. In addition, most service users were living in residential homes (89%), with only 11% living in their own home with support.

Distribution of scores

It is important to note that overall scores were generally very positive, with a high ratio of ratings of 4 (significant) and 5 (very significant) across all groups, meaning that even values below the average for the group represented a predominantly positive preference. Although the trend towards high ratings was common to all groups, there were significant differences in the distribution of data. Both Service providers and Public Administration responses were characterised by little variation around a relatively high mean. In contrast, for the Service user ratings, there was more variability around a slightly lower mean, with more lower scores and fewer high scores. illustrates this pattern.

Table 3. Domain scores and comparisons along with the items on each domain which were rated as ‘most important’ – i.e. significantly higher (at p < 0.01) than the participant group average for that domain.

Which individual items did participants rate as more important?

Given the overall high scores and the fact that even those scores that were below the mean for each stakeholder group still represented relatively high importance scores, the analysis reported below focuses on those items that appeared to be rated as more important. This was defined as an item having a higher importance rating than the domain average for that stakeholder group with statistical significance at p < 0.01. This level of significance was used in order to reduce the likelihood of type 2 errors due to the number of comparisons conducted. illustrates the items within each domain which were rated as more important by each stakeholder group. The section below first presents the domains completed by everyone, followed by the two domains only completed by public administration and service providers.

Domain 1: social care

Within the domain of social care, four items were significantly more important for public administration respondents and service providers: Assessing individual needs; supporting social relationships of people; providing a prompt response to deal with whatever situation the service user was currently experiencing; and providing an effective and ethical response to dementia. The latter two were also rating as more important by service users.

Domain 2: subjective quality of life of service users

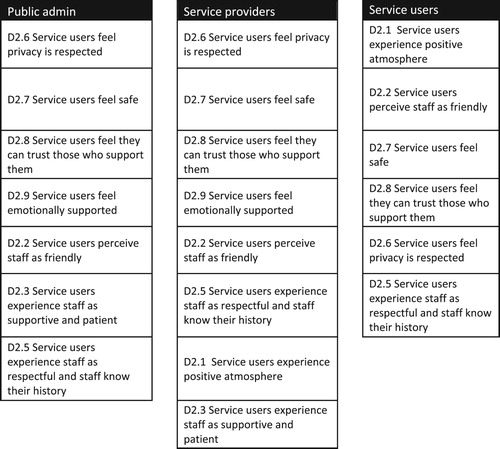

As illustrated in , all but one individual item (2.4 The service user experiences a sense of self-control over daily activities) were rated as more important for at least two out of the three stakeholder groups. On two items, 2.7 Service users feel safe and 2.8 Service users feel they can trust those who support them, all three groups rated these as statistically more important with mean scores above 4.5 and median scores of 5. illustrates the hierarchy of items rated as important for each stakeholder group for Domain 2. As can be seen there are similarities between public administration and service provider ratings and a somewhat different pattern for service users. Item 2.1 (service users experience positive atmosphere) was the highest rated item of all the questions on the service user questionnaires.

Domain 3: health care

None of the individual items on this domain was rated as more important for service providers. However, as can be seen in , item 3.2 (Service can provide palliative care) was rated as significantly important by both public administrator respondents and service users.

Domain 5: quality of the environment

Again, only one item, this time by public administration respondents, was rated as significantly more important – 5.3 Comfortable accommodation offers privacy.

Domain 7: ethics

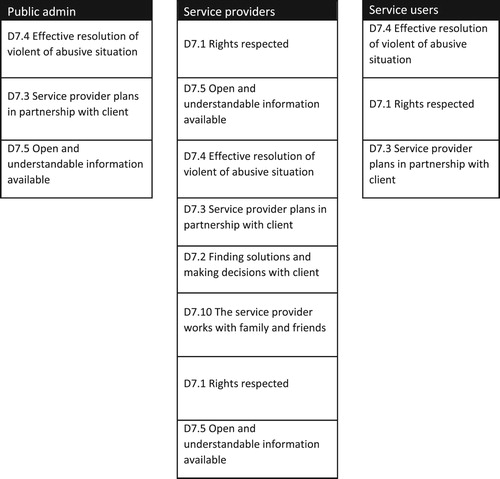

On Domain 7, six individual items were rated as significantly more important for at least one stakeholder group. As illustrated in , two items were significantly more important for all three stakeholder groups – these were item 7.3 (Service provider plans in cooperation with services user) and item 7.4 (Effective resolution of violence or an abusive situation). Service providers and public administration representatives agreed on the importance of having open and understandable information (Item 7.5), while service providers and service users agreed on the greater importance of respect for service user rights (Item 7.1).

Domain 4: management (service provider and public administration only)

Only one item on this domain was rated as significantly more important and only by service providers and that was item 4.1 (There are clear working procedures and staff competencies).

Domain 6: context (service provider and public administration only)

Item 6.1 (Service is reasonably resourced) was the only item in this domain rated as significantly important by both public administration and service providers (see ).

illustrates the order of the items rated as more important by each stakeholder group.

Relative importance of domains by stakeholder groups

How did stakeholder groups differ in their ratings of each domain?

presents the mean and median scores for each domain and for each stakeholder groups along with the results of the Kruskall-wallis or Mann–Whitney U analysis for each domain across stakeholder groups. Dunn post-host hoc tests (significant at p < 0.01) indicated that on all domains service provider and public administration ratings were significantly higher than service user ratings. On all domains apart from D3 Health Care, service provider ratings were also significantly higher than public administration ratings.

Which domains, if any were rated as more important for each stakeholder group?

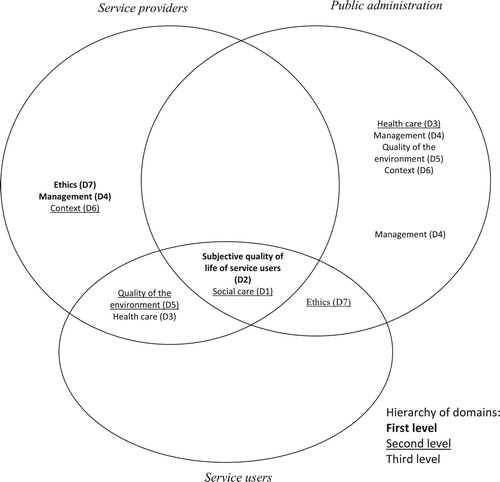

As can be seen from , the Friedman analysis found a significant difference between domains for each stakeholder group. Nemenyi post hoc tests were used to develop a hierarchy for each stakeholder group as summarised in .

Figure 3. Hierarchy of the perceived importance of the domains for the individual groups of stakeholders. Domains were the different stakeholders agreed on the relative importance are placed in the intersection of the corresponding sets.

Service providers

D2 Subjective Quality of Life of Service users was rated significantly higher than domains D1, D3, D5 and D6 (all at p < 0.001). On the other hand, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between D2 and domains D4 and D7. D1, D5 and D6 were significantly higher than D3 Health Care (p < 0.001). This suggests the following hierarchy in terms of relative importance to service providers:

D2, D4, D7

D1, D5, D6

D3

Public administration

D2 Service user subjective Quality of life was rated significantly higher by public administration respondents (p < 0.001) than all other domains. Although only significant at p < 0.05, D3 Health Care was rated significantly higher (at p < 0.05) than D5 Quality of the Environment, D4, management and D6 Context but not D1 Social Care, and D7 Ethics. This suggests the following hierarchy:

D2

D3, D1, D7,

D5, D6, D4

Service users

As for service providers and public administration, D2 (service user subjective quality of life), was by far the highest rated domain for service users and was significantly higher than all other domains (p < 0.001). D3 (Health care) was significantly lower than all other domains (p < 0.003). There were no significant differences between D1, D5 and D7 giving a resulting hierarchy of:

D2

D1, D5, D7

D3

Do ratings of importance vary by participant characteristics or service type?

presents the Spearman’s Rank Order correlation coefficients and biserial correlation coefficients for age and gender.

Table 4. Relationships between age, gender, type of service provided and perceived importance of individual domains.

As can be seen from the , coefficients were generally low and very few were significant at p < 0.01. The only significant associations were for gender and importance ratings by service providers – where female respondents tended to rate D1 Social care, D2 Service user subjective quality of life and D6 Context significantly higher than male respondents.

Not enough service users lived at home with service support coming into them to look at relationships between current service type and importance ratings for service users. However, biserial correlations between type of provided service (dichotomic variable: residential vs. in-home support) and importance rated by service provider highlighted that those that provided residential services (n = 120) rated D3 health care and D5 Quality of the environment higher (p < 0.001) than providers of in-home support (n = 97).

Discussion and summary of findings

The findings suggest that the constructed set of quality indicators was valid, reliable and representative and the mutual correlations between them were factors that justify their division into seven thematic domains. There was some variation in perceived importance between the three groups of stakeholders. However, the highest rated domain by all stakeholders was the subjective quality of life of service users, which included indicators such as expressing feelings of trust and security, perceptions of a positive atmosphere in the service and experiencing staff as friendly. Service providers also prioritised Rights (D7) and Effective management (D4). Service users rated elements related more to their direct experiences higher – so Rights and Quality of the Environment were next most important after subjective quality of life.

Health care (D3) differentiated stakeholders to some extent – with Health care being rated as more important by representatives from public administration than by service providers and service users. However, older service users rated health care as more important than younger service users and those providing residential care rated health care and quality of the environment as more important than those supporting people in their own homes – this is likely to be a result of those in residential services being more severely disabled, older or more frail than those living in their own homes.

There are some limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, as noted earlier, ratings by service providers and public administration representatives were higher on all domains than ratings by service users. As such this makes it hard to compare the absolute importance between these two groups and those by service users. Secondly, the very high ratings by both service providers and public administration respondents may also, at least in part, be accounted for by social desirability – they may be responding as they think they should respond. However, the likelihood of social desirability was reduced by the survey being anonymous. Services users were supported to complete the questionnaire which may have introduced some influence on their responses. However, support was provided by trained fieldworkers rather than by their own staff, which would have helped ensure they felt they could respond openly.

Finally, the sample was skewed towards those providing or living in residential care – only a very small number of people living in their own home with support and providers of such support were included. There was some indication that there were differences between the views of those who provided residential care and those who were supporting people in their own home, although this was confounded by the fact that those who lived in residential care were generally older and had greater support needs – so concluding whether the difference was due to the type of setting or the nature of the people supported was not possible. However, the differences were only in two domains and did not impact on the domains rated as most important, i.e. the subjective quality of life of service users and human rights.

Implications for quality monitoring and future research

Despite the limitations, the study has highlighted the variability but also the points of consistency in how different stakeholders perceived service quality. The findings are likely to initiate discussion and potentially consensus on how service quality can be conceptualised and how it should be measured – a consensus that would bypass the current bias ruled by the legal system which prioritises the view of the state regulator.

The importance of the subjective quality of life of services users was a key point of agreement. As noted in the introduction, the quality standards introduced in the 2006 Act had come under substantial criticism in particular from service providers. Although quality of life of service users is reflected to some extent in the quality standards, overall, the standards and the inspection methods focus on assessing processes rather than outcomes. The processes themselves are assessed in terms of the presence of documentation as an evidence of meeting requirements defined in the quality standards such as documentation on person-centred plans, contracts between service providers and service users on service provision etc. rather than the quality of support or the nature of the relationships between staff and those in receipt of services (Kocman & Paleček, Citation2012).

Although still highly rated overall, the relative importance of the quality of healthcare varied between stakeholders and, also by age of service user and by type of service provided. Services users who were older rated healthcare as more important than service users who were younger. Service providers who provided residential care homes rated health care as more important than those providing support into people’s homes. However, these may be related as most of the service providers of residential care homes were providing for older adults, rather than younger adults with disabilities. For these service providers, healthcare is a significant part of what they do and therefore it is perhaps not surprising that they rate healthcare as more important than other domains. Finally, municipality representatives also rated health care as more important than other stakeholders.

This may partly reflect the current dissatisfaction in the Czechia over the fragmentation of the system and the fact that health and social care are seen as very separate and not always working together (MoLSA, Citation2020). In the context of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD), people should be accessing housing, health care, social care, transport, education etc. from their community rather than as part of a ‘total institution’ (Goffman, Citation1962). However, meeting people’s needs require attention to be paid to all aspects of their lives and co-ordination between sectors such as health, social care, housing, education, so that a holistic support package can be established. This is, however, not easy to establish in practice and is an international issue. For example, in England the concept of joint working between health and social care in particular and ‘Pooled budgets’ were seen as key for the modernising of social services (Great Britain, Citation1998). However, in 2014, the Commission on the Future of Health and Social Care in England called again for an end to the fragmentation between health and social care and recommended ‘a single, ring-fenced budget for health and social care, with a single commissioner’. The Kings Fund (Humphries & Wenzel, Citation2015) put forward recommendations for integrated commissioning which they had hoped would to ensure that there was integrated commissioning in all parts England by 2020. More broadly, Šiška et al. (Citation2015) found that lack of co-ordination and organisation across levels of government and between agencies was a key barrier in the implementation of community living and the UN CRPD Article 19 specifically.

The finding that stakeholders’ views focus primarily on quality of life and the quality of interactions between those providing support and those who are receiving services is not unique to Czechia. For example, in Ireland consultation of service users and families around quality in mental health services found that ‘respectful, empathetic relationships’, ‘an empowering approach to service delivery’ and a ‘quality environment respecting the dignity of the individual and the family’ are key (Mental Health Commission, Citation2005).

Similarly, Czechia is not unique in the fact that quality assessment focuses primarily on processes and procedures, which only sometimes been found to correspond with other assessments of outcomes for service users (Beadle-Brown et al., Citation2008; Netten et al., Citation2012). However, in some countries, quality assessment processes have changed recently, and better agreement has been found between inspectors’ ratings and other measures of outcomes and service quality (Towers et al., Citation2019). In Ireland, as in the UK, inspection processes now include the use of observations of practice, conversations with individuals, and the involvement of experts by experience.

The importance of the subjective quality of life of services users was a key point of agreement. This finding however, poses important questions for how this would/should be assessed/measured. To help people complete this questionnaire for the study it was necessary to provide support to almost all service users. While some people with intellectual disabilities and older people who have dementia or other cognitive difficulties might be able to complete surveys or be interviewed about their quality of life, many cannot. There are also well documented limitations of relying solely on self-report of QoL even for people with milder intellectual disability – for example, the fact that limited experience often brings difficulties with making comparisons or judging how good their current situation is. Alternatively, people can be less likely to say what they really think about a service for fear of losing their place, upsetting staff or getting into trouble (Inclusion Europe, Citation2019). There are also well-documented issues related to asking others to rate or comment on the quality of life of other people, for example, as a proxy or informant (Bertelli et al., Citation2017; Lefort & Fraser, Citation2002).

This has led researchers to argue for the importance of observation Mansell (Citation2011) and the need for inspectors or others looking at quality to visit services and not just to visit to look at the paperwork or the quality of the environment but to look at the quality of the support and interactions between those providing support and those receiving support (Beadle Brown et al., Citation2020). Items such as those in this survey – i.e. whether staff are friendly, respectful, supportive, positive, patient etc. cannot be ascertained from paperwork – it has to be either reported directly by people themselves or observed. This has substantial implications for measuring quality – any measure that requires someone to rate or make a judgement about quality, requires those who are observing to understand what good (and bad) looks like and what is possible to achieve even for those with the most complex and profound needs and not bound by restrictions of unsuitable environments. Such methods also need observers to have training, not just in the tool to be used but in observer discipline. Finally, consideration to inter-observer reliability needs to be given. Although getting reliability on such ratings can be difficult, it is possible to do so (See Beadle-Brown et al., Citation2012 as an example).

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dorota Šišková, Lenka Dlouhá, Marie Maňáková, Michaela Komrsková, Nikol Gruberová, Petr Bláha, Vendula Lipková, Camille Latimier, and Šárka Káňová for their great contribution to the study, namely for assistance with preparation of the research tools and data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jan Šiška

Jan Šiška is an associate professor. His research interests include comparative policy and practice in social services, deinstitutionalisation and community-based services particularly for persons with disabilities and mental health problems.

Pavel Čáslava

Pavel Čáslava is a consultant for the Association of Social Service Providers, Czech Republic and chairman of the Ethics Committee. He is interested in systemic issues of social services, regulation and evaluation of quality and ethical issues of social welfare policies and systems.

Jiří Kohout

Jiří Kohout is an associate professor with interests in quantitative research methods in social sciences.

Julie Beadle-Brown

Julie Beadle-Brown is a professor in intellectual disabilities. Her research is focused on active support for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities, empowerment and community-based services.

Zuzana Truhlářová

Zuzana Truhlářová is an assistant professor. Her research interests consist of social work, and social services with particular focus on long-term social care.

Markéta Kateřina Holečková

Markéta Kateřina Holečková is as assistant professor and expert for the Government administration in social welfare.

References

- Beadle Brown, J., Beecham, J., Leigh, J., Whelton, R., & Richardson, L. (2020). Outcomes and costs of skilled support for people with severe or profound intellectual disability and complex needs. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 00, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12782

- Beadle-Brown, J., Hutchinson, A., & Mansell, J. (2008). Care standards in homes for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 21(3), 210–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2007.00400.x

- Beadle-Brown, J., Hutchinson, A., & Whelton, B. (2012). Person-centred active support – Increasing choice, promoting independence and reducing challenging behaviour. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 25(4), 291–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2011.00666.x

- Bertelli, M., Bianco, A., Rossi, A., Mancini, M., Malfa, G., & Brown, I. (2017). Impact of severe intellectual disability on proxy instrumental assessment of quality of life. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 44(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2017.1350835

- Brown, C. R. (2007). Where are the patients in the quality of health care? International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(3), 125–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm009

- Czechia, Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (MoLSA). (2005). Návrh zákona o sociálních službách je hotov. Tisková zpráva. [Proposal for the Act on Social Services. Press release]. (Original work published in Czech).

- Czechia, Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (MoLSA). (2020). Social inclusion strategy 2021–2030.

- Czechia Ombudsman. (2019). Je alarmující, že stát odsouvá ochranu senior. Tisková zpráva. [It is alarming that the state postpones protection of the elderly. Press release]. https://www.ochrance.cz/aktualne/tiskove-zpravy-2019/je-alarmujici-ze-stat-odsouva-ochranu-senioru/ (Original work published in Czech).

- Donabedian, A. (1966). Evaluating the quality of medical care. USPHS. Health Services Research Study Project.

- Donabedian, A. (1980). Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring. Health Administration Press.

- Donabedian, A. (1988). The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 260(12), 1743–1748. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.260.12.1743

- Goffman, E. (1962). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Aldine.

- Great Britain. (1998). Modernising social services: Promoting independence, Improving protection, raising standards. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20131205101158/http://www.archive.official-documents.co.uk/document/cm41/4169/4169.htm.

- Humphries, R., & Wenzel, L. (2015). Options for integrated commissioning. The King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/Options-integrated-commissioning-Kings-Fund-June-2015_0.pdf.

- Inclusion Europe. (2003). Achieving quality. Consumer involvement in quality evaluation of services. https://www.inclusion-europe.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Achieving_Quality.pdf.

- Kocman, D., & Paleček, J. (2012). Podněty k revizi standardů kvality sociálních služeb. Prague. [Suggestions for Amending the Quality Standards in Social Services]. (Original work published in Czech).

- Kocman, D., & Paleček, J. (2013). Formalismus a inspekce kvality sociálních služeb. Zpráva z kvalitativního šetření. [Formalism and quality control of social services. Qualitative survey report]. Centrum pro výzkum a inovaci v sociálních službách. (Original work published in Czech).

- Lefort, S., & Fraser, M. (2002). Quality of life measurement and its use in the field of learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 6(3), 223–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1469004702006003033

- Malley, J., & Fernández, J. L. (2010). Measuring quality in social care services: Theory and practice. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 81(4), 559–582. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8292.2010.00422.x

- Mansell, J. (2011). Structured observational research in services for people with learning disabilities. SSCR methods review. 10. NIHR School for Social Care Research.

- McGlynn, E. A. (1997). Six challenges in measuring the quality of health care by Elizabeth A. McGlynn. Health Affairs, 16(3), 3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.16.3.7

- Mental Health Commission. (2005). Quality in mental health – Your views: Report on stakeholder consultation on quality in mental health services. https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/42818.

- Netten, A., Trukeschitz, B., Beadle-Brown, J., Forder, J., Towers, A., & Welch, E. (2012, April 27). Quality of life outcomes for residents and quality ratings of care homes: Is there a relationship? Retrieved October 3, 2020, from https://academic.oup.com/ageing/article/41/4/512/47274.

- Pittam, G., Dent, M., Hussain, N., Griffin, M., Hovard, L., & Blackwood, R. (2015). A multi method study to inform the development of quality watch: Consensus on quality. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

- Qureshi, H., & Nicholas, E. (2001). A new conception of social care outcomes and its practical use in assessment with older people. Research Policy and Planning, 19(2), 11–26. http://ssrg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/rpp192/article2.pdf.

- Schalock, R. L., Brown, I., Brown, R., Cummins, R. A., Felce, D., Matikka, L., Keith, K. D., & Parmenter, T. (2002). Conceptualization, measurement, and application of quality of life for persons with intellectual disabilities: Report of an international panel of experts. Mental Retardation, 40(6), 457–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2002)040<0457:CMAAOQ>2.0.CO;2

- Šiška, J., & Beadle Brown, J. (2020). Transition from institutional care to community-based services in 27 EU member states: Final report. Research report for the European Expert Group on Transition from Institutional to Community-based Care.

- Šiška, J., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2011). Developments in deinstitutionalization and community living in the Czech Republic. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 8(2), 125–133. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2011.00298.x

- Šiška, J., Beadle Brown, J., & Káňová, Š. (2015). DISCIT making persons with disabilities full citizens – New knowledge for an inclusive and sustainable European social model deliverable 6.3 (D6.3). Transitions from institutions to community living in Europe. https://blogg.hioa.no/discit/files/2016/02/DISCIT-D6_3-Final-July-2015.pdf.

- Šiška, J., & Čáslava, P. (2021). Four decades towards community-based disability support services in Czechia. In J. Šiška, & J. Beadle (Eds.), The development, conceptualisation and implementation of quality in disability support services. Karolinum. (in press).

- SPC. (2010). A voluntary European quality framework for social services. The SocialProtection Committee – SPC.

- Stichler, J. F., & Weiss, M. E. (2001). Through the eye of the beholder: Multiple perspectives on quality in women’s health care. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 15(3), 59–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00001786-200104000-00009

- Towers, A., Palmer, S., Smith, N., Collins, G., & Allan, S. (2019). A cross-sectional study exploring the relationship between regulator quality ratings and care home residents’ quality of life in England. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 17(1), 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1093-1